Abstract

To evaluate the effectiveness of green finance, this study treats China’s green finance reform and innovation pilot zones as a quasi-natural experiment to assess their impact on urban energy efficiency. This research utilizes a panel dataset of 282 Chinese prefecture-level cities from 2010 to 2023 and employs a multi-period difference-in-differences (DID) model. The core dependent variable, urban green total factor energy efficiency (UGTFEE), is quantified using a non-radial Slack-Based Measure (SBM) efficiency model combined with the Malmquist-Luenberger index. The empirical findings reveal four key points. First, the green finance pilot zones significantly enhance UGTFEE, with policy-affected cities demonstrating an average improvement of approximately 2.0% relative to non-pilot cities. Second, this positive impact is transmitted through two primary mechanisms: the advancement of green technology research and development and the deepening of financial market development. Third, the policy’s effectiveness is heterogeneous, varying according to regional characteristics such as geographical location, environmental regulation stringency, and resource endowments. Finally, a negative spatial spillover is identified, wherein the policy creates a siphoning effect that competitively suppresses the UGTFEE of neighboring cities. These findings provide critical theoretical insights and empirical evidence for optimizing green finance initiatives, thereby facilitating urban industrial transformation toward greater green energy efficiency.

1. Introduction

The global transition to net-zero emissions demands innovative financial mechanisms to channel capital toward energy-efficient and low-carbon systems, a critical imperative for sustainable urban development. Green finance has emerged as a cornerstone for mobilizing resources to support renewable energy, energy-efficient technologies, and climate-resilient infrastructure. As cities worldwide grapple with rising energy demands and environmental pressures, policies that enhance urban green total-factor energy efficiency (UGTFEE)—a metric integrating energy use, economic output, and environmental performance—are vital for achieving sustainable development goals. This study investigates how green finance reform can drive UGTFEE, offering scalable insights for global policymakers navigating the complex interplay of energy systems, economic growth, and climate mitigation.

To clarify the connection, green finance reform directly impacts regional energy efficiency by fundamentally altering capital allocation and imposing environmental accountability. Specific measures, such as tightening green credit standards and issuing specialized green bonds, create a dual incentive-and-constraint mechanism. On one hand, these reforms raise the financing threshold and costs for high-pollution, high-energy-consumption enterprises, compelling them to either innovate or exit the market. On the other hand, they provide low-cost, accessible capital for firms engaged in clean technology R&D and the adoption of energy-saving equipment. This targeted reallocation of financial resources catalyzes a dual response: fostering technological innovation in energy efficiency and accelerating the upgrading of the regional industrial structure towards low-carbon, high-value-added sectors, thereby systemically improving overall energy efficiency.

In China, a global leader in climate policy experimentation, the Green Finance Reform and Innovation Pilot Zones (GFRP_Policy), launched since 2017 across key provinces and cities, exemplify a strategic approach to align financial systems with sustainable energy goals (Table 1). These zones deploy market-based instruments to optimize energy structures, support eco-friendly technologies, and foster urban sustainability. By leveraging these pilot zones as a quasi-natural experiment, this study examines their impact on UGTFEE, elucidating how green finance can catalyze energy efficiency and contribute to China’s carbon neutrality ambitions, while offering lessons for global energy policy frameworks.

Table 1.

List of Green Finance Reform and Innovation Pilot Zones.

By leveraging China’s pilot zones as a quasi-natural experiment, we provide one of the first systematic evaluations of this specific policy’s direct impact. While we employ established and robust methods like the non-radial SBM and Malmquist-Luenberger models to construct our UGTFEE indicator, our primary contribution is the empirical application itself: rigorously quantifying the policy’s causal effect on this comprehensive efficiency measure. Second, the specific pathways through which green finance enhances UGTFEE are not yet fully understood. Our multi-period DID framework dissects these mechanisms, including fostering green innovation and deepening financial markets, to provide a granular understanding of the policy’s causal chain. Third, existing studies often overlook the crucial dimensions of heterogeneity and spatial spillovers in policy outcomes. By examining the differential impacts across various city types and identifying spatial effects, we enrich the theoretical and empirical foundations for designing effective green finance policies.

2. Literature Review

The literature on green finance highlights its transformative potential across multiple domains. At a macro level, it is positioned as a key driver for achieving sustainable development goals, with studies demonstrating its capacity to significantly enhance green total factor productivity (GTFP) (Feng et al., 2024) [1], facilitate low-carbon economic transition (Li et al., 2023) [2], and optimize industrial structures (Zhou et al., 2023) [3]. The underlying logic is that by redirecting capital, green finance fosters technological innovation and supports the upgrading of energy-intensive industries. At the micro level, policies like green credit have been shown to impact firms by alleviating financing constraints and promoting R&D investment (Li et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2025) [2,4], thereby boosting their productivity. However, the existing body of research, while extensive, predominantly focuses on broader indicators like GTFP or carbon productivity. There is a conspicuous lack of inquiry into the specific, causally identified impact of green finance reforms on urban green total factor energy efficiency (UGTFEE), a more direct and critical measure of sustainable energy transition (Ren et al., 2025; Huang et al., 2023) [5,6].

Concurrently, research on energy efficiency has evolved significantly, shifting from rudimentary single-factor metrics to more sophisticated total-factor frameworks that account for undesirable outputs such as pollution. Methodologically, Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), particularly the Slacks-Based Measure (SBM) model, has become the standard for calculating Green Total Factor Energy Efficiency (GTFEE) (Guo et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2023) [7,8]. This approach has enabled researchers to identify a multitude of influencing factors, including environmental regulation (Li et al., 2023) [2], digital transformation (Liu et al., 2024; Wan, S.W. et al., 2025) [9,10], and innovation-driven policies (Kong et al., 2023) [11]. However, a fundamental limitation pervades much of this research: an over-reliance on correlational analysis that struggles to disentangle the causal effect of a specific policy from confounding macroeconomic variables. While spatial econometric models are increasingly employed to confirm the existence of spatial spillovers (Guo et al., 2023; Lin et al., 2024) [12,13], the precise transmission mechanisms often remain a “black box,” and the direction and magnitude of these spillovers can vary significantly across regions, indicating substantial heterogeneity (Yu et al., 2024) [14].

A critical assessment of these two research streams reveals three distinct gaps in the literature, which this study is designed to address. First, despite a general consensus on the positive relationship between green finance and environmental quality, rigorous causal evidence on the impact of green finance reforms specifically on urban-level GTFEE is scarce. Existing analyses are often conducted at the provincial level or focus on firms, overlooking the unique dynamics within cities, which are the primary centers of energy consumption (Ren et al., 2025; Zhou et al., 2023) [3,5]. By leveraging China’s green finance reform pilot zones as a quasi-natural experiment, this study can robustly isolate the policy’s net effect on UGTFEE, thereby providing a more granular and energy-centric evaluation. Second, the pathways through which green finance influences UGTFEE remain theoretically plausible but empirically underdeveloped. While mechanisms such as promoting green technology innovation and optimizing industrial structure are frequently cited as crucial mediators (Wang et al., 2025) [4], their relative contributions and interplay under the specific pressure of green finance reform are not well understood. This study will employ a multi-period difference-in-differences framework to formally dissect these transmission channels, offering a clearer mechanistic explanation of policy efficacy. Third, existing studies often highlight significant regional heterogeneity and the presence of spatial spillovers (Guo et al., 2023; Lin et al., 2024) [12,13] but rarely integrate both into a unified analytical framework. This oversight can lead to an incomplete understanding of policy outcomes. By systematically examining differential impacts across various city characteristics and modeling spatial dynamics, this research will provide a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding, enriching the theoretical and empirical foundations for designing effective green finance policies that can accelerate the global sustainable energy transition.

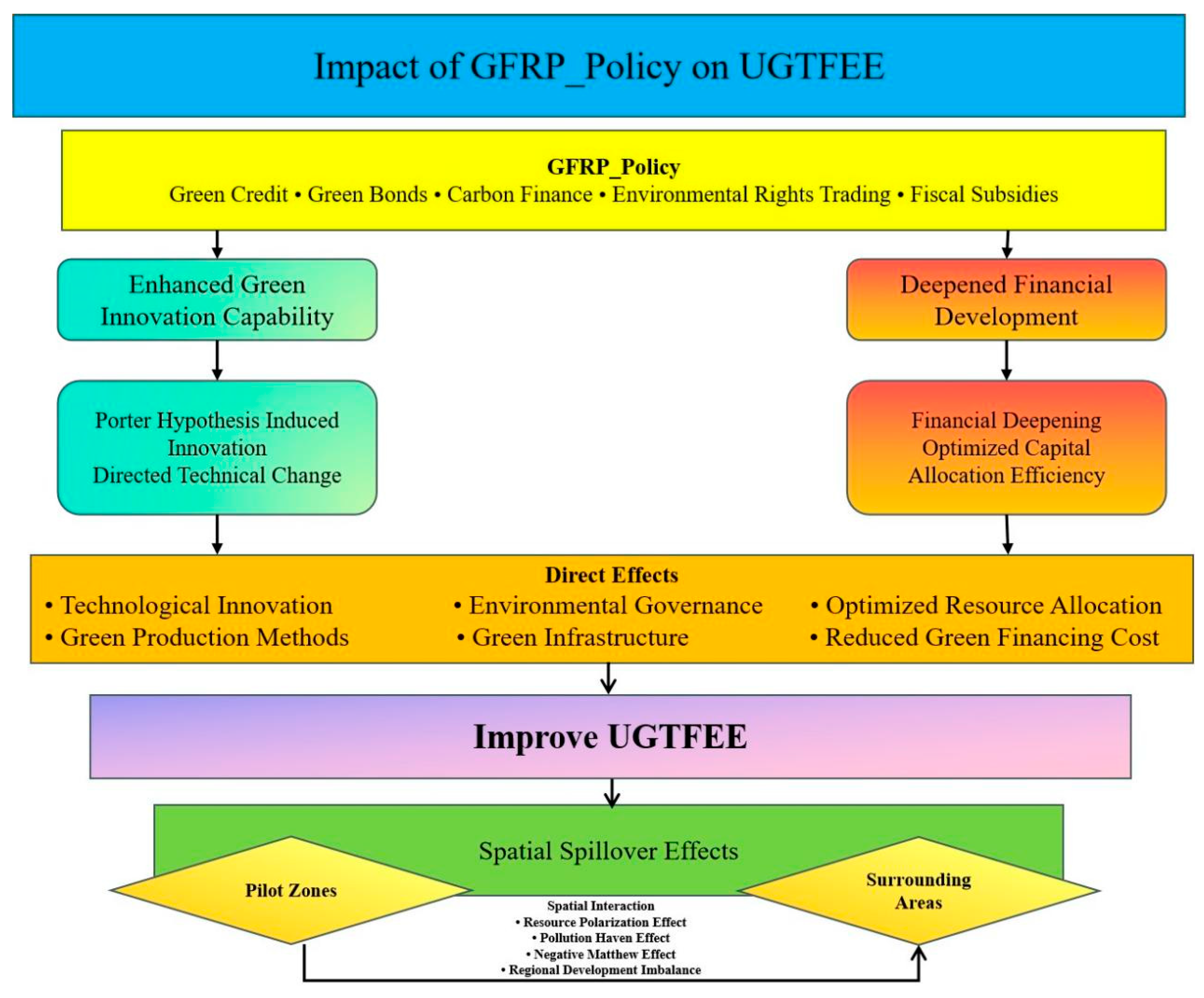

3. Theoretical Analysis and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Direct Effect: A Resource Allocation Perspective

From the standpoint of microeconomic theory, environmental pollution represents a classic case of market failure, where negative externalities lead to the overconsumption of energy and a suboptimal allocation of societal resources. Green Finance Reform Policies (GFRP) are designed as a targeted institutional intervention to internalize these externalities. By creating a suite of financial instruments such as green credit, bonds, and insurance (Sun & Li, 2025) [15], these reforms fundamentally alter the relative cost of capital, imposing higher financing costs on polluting industries while providing preferential access to capital for firms engaged in energy conservation and clean technology development. This policy-driven shift in financial incentives is expected to catalyze a reallocation of production factors—capital, labor, and energy—from low-efficiency, high-emission sectors toward high-efficiency, low-carbon sectors (Feng et al., 2024) [1]. This process enhances allocative efficiency across the urban economy, leading to an overall improvement in productivity that accounts for environmental outputs. Several empirical studies have confirmed that green finance pilot zones and related policies can indeed significantly improve urban green total factor energy efficiency (Ren et al., 2025; Zhou et al., 2023) [3,5]. Based on this theoretical reasoning, we propose our first hypothesis:

H1.

GFRP_Policy significantly enhances UGTFEE.

3.2. Transmission Mechanisms: Integrating Innovation Economics and Financial Development Theory

First, from the perspective of innovation economics, the “directed technical change” theory posits that the direction of innovation is endogenous to market signals and policy incentives. GFRP acts as a powerful market signal, increasing the expected returns on green R&D and investment. By making capital more accessible for sustainable technologies, the policy explicitly directs firms’ innovation efforts toward developing and adopting energy-saving processes and cleaner production methods. This “induced innovation” effect is consistently identified in the literature as a fundamental pathway through which green finance promotes energy efficiency and green productivity (Li et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2024; Zhou et al., 2023) [2,3,14].

Second, according to financial development theory, a sophisticated financial system is crucial for economic growth as it efficiently mobilizes savings and allocates capital to the most productive investments. GFRP can be conceptualized as a specialized form of targeted financial deepening. By introducing novel financial products and services tailored for the green economy, it enhances the financial system’s capacity to support sustainable projects, which often face distinct challenges like higher initial costs. This targeted financial support alleviates the financing constraints that impede green investments (Chi et al., 2025; Guo et al., 2023) [12,16], thereby accelerating the structural transformation of the urban economy. As capital flows more readily toward green and technologically advanced sectors, the policy actively promotes industrial upgrading and the optimization of the energy consumption structure (Feng et al., 2024; Li et al., 2023) [1,2], resulting in a greater share of economic output from industries that are inherently less energy-intensive. Integrating these two theoretical strands, we propose our second hypothesis:

H2.

The GFRP_Policy enhances UGTFEE through the dual pathways of stimulating green technology innovation and optimizing industrial structure.

3.3. Spatial Spillover Effects: A Regional Economics Perspective

Drawing upon theories from regional economics and economic geography, geographically targeted policies can create complex inter-regional spillovers. While designed as growth poles, pilot zones can trigger “polarization effects.” The concentration of preferential policies and financial resources may attract a disproportionate share of mobile factors of production—such as green capital, specialized talent, and innovative enterprises—from surrounding areas. This agglomeration can bolster UGTFEE within the pilot cities but may simultaneously create a “siphoning effect” that deprives neighboring non-pilot regions of the critical resources needed for their own green transition.

Concurrently, the “pollution haven” hypothesis provides a compelling framework for understanding potential negative spillovers. As environmental regulations and financial scrutiny intensify within the pilot zones, firms in highly polluting and energy-intensive sectors may face increased compliance costs and be forced to relocate. Non-pilot regions, potentially prioritizing short-term economic growth over environmental quality, may become attractive destinations for this displaced industrial activity. The consequent influx of low-efficiency, high-emission industries would exert downward pressure on the average UGTFEE in these surrounding areas. While some studies find positive spatial spillovers from green finance (Guo et al., 2023; Xu & Zhao, 2023) [12,17], the effect is often highly heterogeneous, with evidence of negative spillovers in certain regions, such as China’s central and western areas (Guo et al., 2023; Lin et al., 2024) [12,13]. This suggests that the net spatial effect is not predetermined and that negative outcomes are a distinct possibility. This leads to our final hypothesis:

H3.

GFRP_Policy exerts negative spatial spillover effects, suppressing UGTFEE in surrounding non-pilot regions.

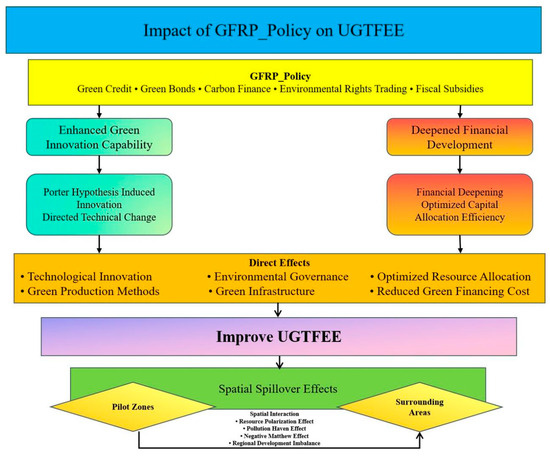

The specific mechanism of action is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework for GFRP_Policy.

4. Sample Selection and Research Design

4.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

The sample comprises 282 Chinese prefecture-level cities from 2010 to 2023, with the treatment group consisting of nine cities designated as green finance reform and innovation pilot zones in 2017 (Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Guangdong, Guizhou, Xinjiang) and 2019 (Lanzhou New Area). Hami and Changji in Xinjiang are excluded due to significant data gaps. The data used to construct UGTFEE are primarily sourced from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the China City Statistical Yearbook, and the China Energy Statistical Yearbook. The mechanism variables FinA and the control variables are mainly sourced from the National Bureau of Statistics of China and the China City Statistical Yearbook, while the number of green patents, another mechanism variable, is sourced from the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA). Missing data are addressed using linear interpolation and regression imputation to ensure completeness.

4.2. Variable Description

4.2.1. Dependent Variable: UGTFEE

Following Wang [18], we measure UGTFEE using a super-efficiency Slack-Based Measure (SBM) model and the Malmquist-Luenberger index, incorporating labor (L), capital (K), and energy (E) as inputs, regional GDP as the desirable output, and industrial sulfur dioxide (SO2), smoke and dust, and wastewater emissions as undesirable outputs. This approach accounts for environmental constraints, providing a comprehensive assessment of urban energy efficiency under sustainability objectives. The model assumes that each DMU to be valued has m inputs, q expected outputs and w unexpected outputs. The model formula is as follows. ρ is the efficiency value of the DMU, which reflects the level of green total factor energy efficiency. x, ji,j, yg, jr,j, ybu,j represent the i-th input, r-th expected output and u-th unexpected output, respectively, and λ is the weight vector of the DMU.

4.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable

GFRP_Policy. Defined as the interaction of city and year dummy variables (city_code *times year), where (city_code = 1) for pilot cities and 0 otherwise, and (year = 1) for years post-policy implementation and 0 pre-implementation.

4.2.3. Moderating Variables

To elucidate the pathways through which GFRP_Policy enhance UGTFEE, we include two mechanism variables. Green innovation capacity (lnGTI), measured as the natural logarithm of the total number of green patent authorizations (including both invention and utility model patents) following Yuan et al. [19], quantifies technological innovation in sustainability, a critical driver of energy-efficient practices.

Referring to the research of Arcand et al. (2015) and Kong, L. et al. (2023) [11,20], financial deepening (FinA) refers to the process whereby a region’s financial system expands in scale relative to its economic output and improves its operational efficiency. It reflects the availability and sophistication of financial services, the depth of financial markets, and the capacity to mobilize and allocate capital effectively within the regional economy. Following the established literature, we use the ratio of year-end financial institution loan balances to regional GDP as a proxy for this concept. This metric is commonly used as it reflects the capacity and scale of financial intermediation relative to the size of the economy. However, it is important to clarify that this measure inherently captures the scale of financial activity rather than directly revealing the quality or “greenness” of capital allocation. We posit that financial deepening functions as a foundational capability and a crucial conduit for policy implementation. The logic is twofold: First, a higher degree of financial deepening signifies a more developed and efficient system for mobilizing and reallocating capital in general. Second, the GFRP_Policy introduces specific “green” criteria and incentives that act as a powerful directing signal, altering the flow of capital within this developed system. Therefore, financial deepening functions as an amplifier; it enhances the capacity and responsiveness of the financial system to the policy’s directives, thereby enabling a more effective reallocation of capital towards low-carbon projects and ultimately improving UGTFEE.

4.2.4. Control Variables

To isolate the effect of GFRP_Policy on UGTFEE, we incorporate a comprehensive set of control variables grounded in established literature [21,22]. Economic development, measured as the natural logarithm of per capita GDP (lnpgdp), captures economic scale effects that may influence energy efficiency. The urbanization rate (urb), defined as the ratio of urban to total population, reflects structural urban dynamics affecting resource allocation and energy use. Government science investment (st), calculated as the share of science expenditure in local fiscal budgets, proxies innovation support critical for technological advancements in energy efficiency. Government education support (edu), measured as the share of education expenditure in local fiscal budgets, serves as an indicator of human capital investment. Fiscal capacity (fin), represented by local government general budget expenditure, captures fiscal strength influencing policy implementation. Lastly, human capital (hc), measured as the number of university students per 10,000 population, reflects workforce quality, the key driver of sustainable urban transitions.

Descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics.

4.3. Model Specification

To evaluate the impact of GFRP_Policy on urban green total-factor energy efficiency (UGTFEE), we employ a multi-period difference-in-differences (DID) framework, leveraging the staggered implementation of pilot zones across different years. This quasi-experimental approach accounts for heterogeneity in policy timing and isolates causal effects by comparing treated and control cities over time. The baseline model is specified as follows:

where i and t denote city and year, respectively. The dependent variable, represents urban green total-factor energy efficiency. The core explanatory variable, , is a binary indicator defined as the interaction of city and year dummies, taking a value of 1 for cities designated as pilot zones in or after year, and 0 otherwise. is a vector of control variables, is the intercept, captures city fixed effects, accounts for year fixed effects, and is the error term. This specification controls for unobserved time-invariant city characteristics and common temporal shocks, ensuring robust identification of policy effects.

5. Empirical Results Analysis

5.1. Baseline Regression

To test the hypotheses, we employ the baseline regression model (Equation (1)) to examine the impact of GFRP_Policy on UGTFEE. The regression results are presented in Table 3. Model 1 and Model 2 report the outcomes with city and year fixed effects, without and with control variables, respectively. The coefficient of the GFRP_Policy is 0.051 in Model 1 and 0.020 in Model 2, significant at the 1% and 5% levels, respectively. These findings indicate that the establishment of green finance reform and innovation pilot zones significantly enhances UGTFEE, thereby validating Hypothesis 1. On average, UGTFEE in pilot cities increases by approximately 5.900% compared to non-pilot cities. The implementation of GFRP_Policy fosters the development of green financial systems, enabling pilot cities to optimize capital allocation through differentiated financing mechanisms.

Table 3.

Benchmark regression results.

5.2. Robustness Checks

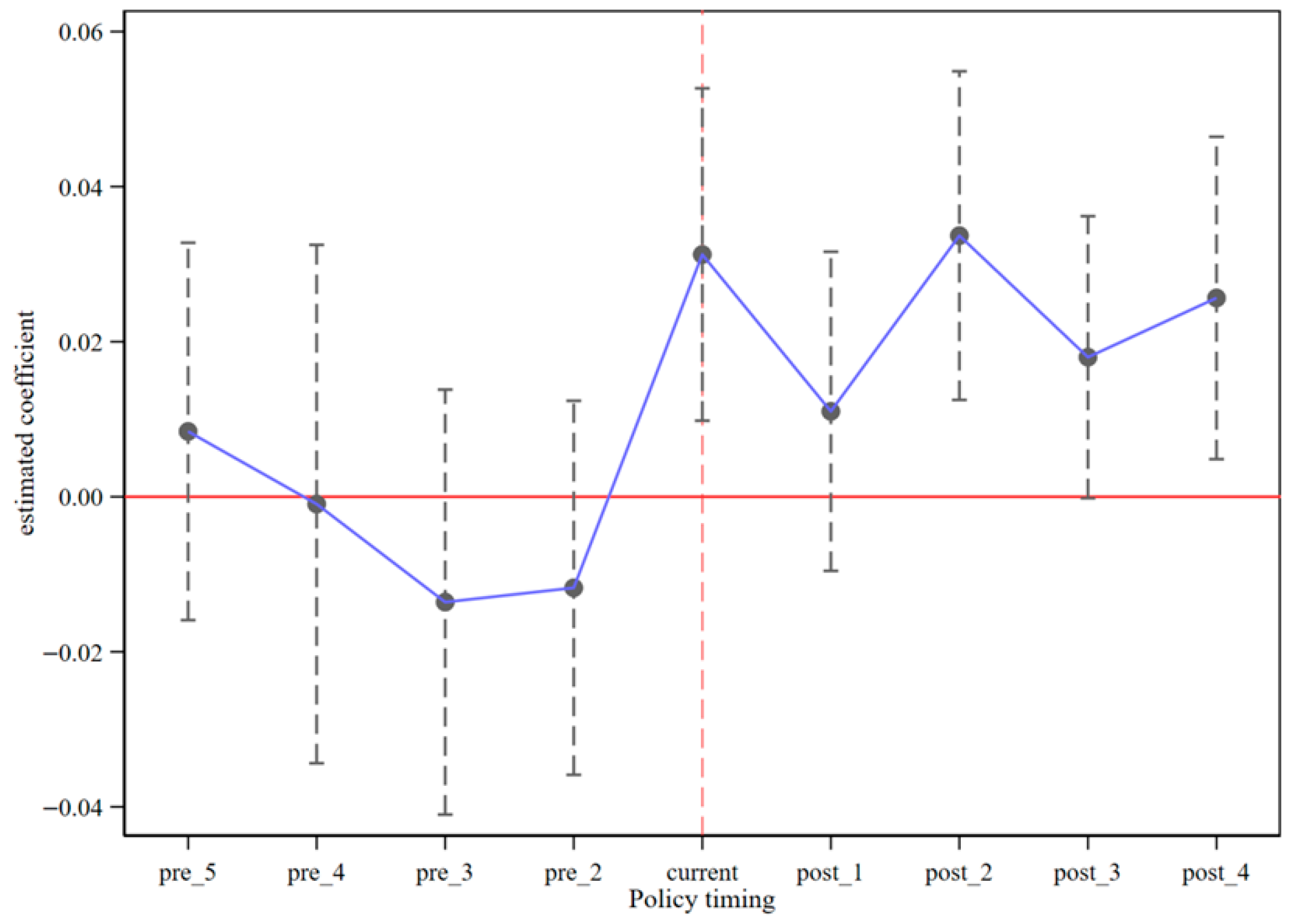

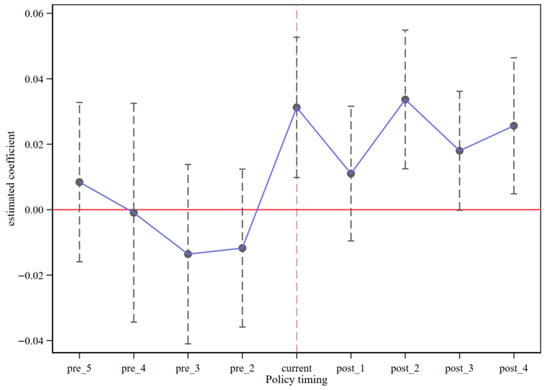

5.2.1. Parallel Trends Assumption

The multi-period difference-in-differences (DID) estimation hinges on the parallel trends assumption, which requires that urban green total-factor energy efficiency (UGTFEE) in pilot and non-pilot cities exhibit similar trends prior to the implementation of GFRP_Policy, with no systematic differences. To test this assumption, we employ an event study approach, with results presented in Figure 2. The estimated coefficients for the five periods before policy implementation are statistically insignificant and exhibit stable, flat trends, indicating no significant pre-policy differences in UGTFEE between pilot and non-pilot cities. After the implementation of the policy, except for the first year when the coefficient might not be significant due to the lag effect of the policy, all the coefficients have statistical significance and tend to stabilize and strengthen over time. These findings confirm that the multi-period DID model satisfies the parallel trends assumption, demonstrating that the establishment of green finance reform and innovation pilot zones positively impacts UGTFEE, albeit with a delayed onset, underscoring the policy’s gradual but sustained effect on energy efficiency. The event study approach validates the parallel trends assumption using the model:

where denotes policy timing dummies relative to the year of implementation. As illustrated in Figure 2, coefficients for pre-policy periods are statistically non-significant and close to zero, fulfilling the parallel trends assumption. Post-policy coefficients exhibit significant values, with confidence intervals consistently excluding zero, thereby validating the robustness of the difference-in-differences framework.

Figure 2.

Results of Balance Trend Test.

5.2.2. Endogeneity Test

While our primary DID model controls for an extensive set of variables, the potential for unobserved confounding factors necessitates further robustness checks. To address such endogeneity concerns, we employ an instrumental variable approach. Following the methodology of Li et al. [23], we select the terrain ruggedness degree (RDLS) of each prefecture-level city, interacted with the post-policy time dummy, as an instrumental variable for the policy itself. The validity of this instrument hinges on two core assumptions. First, the relevance condition is met, as geographical and ecological factors are integral to the central government’s strategic selection of pilot zones. Areas with more rugged terrain often face greater constraints on traditional development paths and possess more fragile ecosystems, making them prime candidates for green finance reforms aimed at fostering sustainable transformation. Second, and more critically, the exogeneity assumption requires careful justification, as we acknowledge that terrain ruggedness is not entirely disconnected from historical economic development and energy use patterns. For instance, rugged terrain might have historically hindered industrialization, leading to different economic structures and energy consumption profiles. However, these effects are largely time-invariant or slow-moving. In our DID framework, any such time-invariant effects of terrain on a city’s UGTFEE are already captured by the inclusion of city-fixed effects. For the exogeneity assumption to be violated, one must argue that cities with different levels of terrain ruggedness would have experienced systematically different trends in UGTFEE even in the absence of the policy. We contend there is no strong theoretical or empirical basis for such a claim. Therefore, as a predetermined geographical characteristic, terrain ruggedness is unlikely to be correlated with the error term in our model, satisfying the exclusion restriction. The first-stage results in Table 4 confirm the instrument’s relevance, showing a significantly positive coefficient for the RDLS*post interaction term. The second-stage results further validate our main findings, demonstrating that the implementation of GFRP_Policy significantly improves UGTFEE. This confirms that our core conclusions are robust to potential endogeneity.

Table 4.

Endogeneity test results.

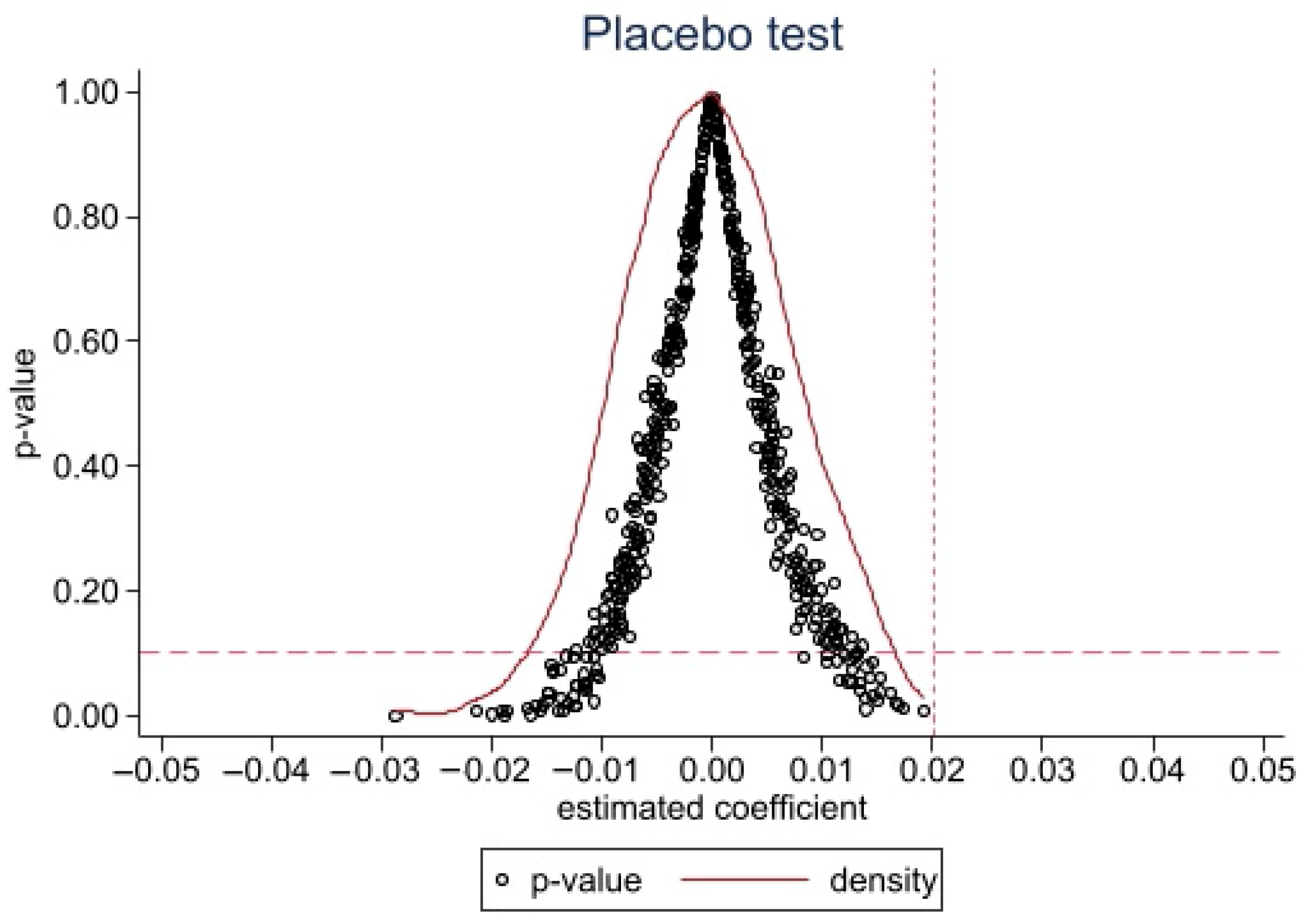

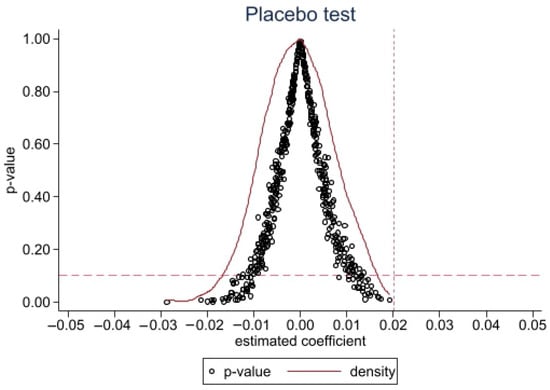

5.2.3. Placebo Test

To address potential biases from unobserved omitted variables in the baseline regression results, we conducted a placebo test to assess the robustness of our findings. We generate a fictitious policy interaction term by randomly assigning pilot and non-pilot city statuses and perform 500 iterations of randomized shocks across the sample cities. As shown in Figure 3, the coefficients of the randomly generated policy interaction terms are predominantly clustered around zero, with most p-values exceeding 0.1, indicating statistical insignificance at the 10% level. These coefficients significantly deviate from the baseline regression estimate of 0.02, confirming that the baseline results are not driven by unobserved confounding factors. This placebo test thus validates the robustness of our findings, reinforcing the causal impact of GFRP_Policy on urban green total-factor energy efficiency.

Figure 3.

Results of placebo test.

5.2.4. Eliminate the Impact of the COVID-19

Drawing on Tu et al. [24], we account for the exogenous shock of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated containment measures, which tightened financial market liquidity and reduced risk appetite, constraining capital allocation. These conditions prompted firms to prioritize short-term survival, curtailing investments in green technological innovation. Concurrently, local governments, focused on stabilizing economic growth, reduced environmental protection expenditures, delaying the implementation of clean energy projects and green infrastructure in pilot cities. This impeded industrial upgrading and limited the short-term efficacy of GFRP_Policy, hindering improvements in UGTFEE. To isolate these disruptions, we exclude the 2021–2022 pandemic period from the sample and re-estimate the regression model. The results are presented in Table 5. Model 5 and Model 6 report the outcomes with city and year fixed effects, without and with control variables, respectively. The coefficients for the GFRP_Policy are 0.045 and 0.019 in Model 5 and Model 6, respectively, significant at the 1% and 5% levels. These estimates are consistent with the baseline regression coefficients, showing no substantial deviation in magnitude or direction of the policy’s effect. This robustness check further validates the stability of the baseline findings, confirming that GFRP_Policy consistently enhance UGTFEE, even when accounting for pandemic-related distortions.

Table 5.

Results of excluding the impact of COVID-19.

5.2.5. Robustness Check: Accounting for Confounding Policy Effects

To ensure the identified effect of GFRP_Policy on UGTFEE is not confounded by concurrent policies, we account for the potential influence of the Total Nitrogen Control Policy (TNCP), which may also enhance UGTFEE. Following Zou et al. and Wan et al. [25,26], we incorporate a dummy variable for the TNCP into the baseline regression model. The results are presented in Table 6. Model 7 and Model 8 report estimates with city and year fixed effects, without and with the exclusion of seven cities subject to overlapping policies, respectively. The regression results show that the coefficient and significance of the GFRP_Policy remain stable, with values of 0.021 (Model 7) and 0.022 (Model 8), both significant at the 5% level (standard errors: 0.010 and 0.011, respectively). While the TNCP is significant at the 5% level (coefficient: 0.022, standard errors: 0.010 and 0.011), its broader coverage and longer implementation timeline do not diminish the positive effect of the GFRP_Policy on UGTFEE. After controlling for the TNCP and excluding overlapping samples, the GFRP_Policy’s effect remains robust, with consistent coefficients and significance. These findings confirm the reliability of the baseline regression results, demonstrating that the GFRP_Policy’s impact on UGTFEE is not driven by confounding policy interventions.

Table 6.

Results of eliminating significant policy interference.

5.2.6. Robustness Check: Incorporating Province-Year Fixed Effects

To address potential biases from unobserved province-level time-varying factors, which may not be fully captured by city and year fixed effects in the baseline regression, we follow Kim and Kang [27] by incorporating province-year interaction fixed effects. This approach accounts for province-specific temporal trends that could influence UGTFEE. The regression results are presented in Table 7. Model 9 and Model 10 report estimates with city, year, and province-year interaction fixed effects, without and with control variables, respectively. The coefficients for the GFRP_Policy are 0.038 and 0.035, respectively, both positive and significant at the 1% and 5% levels (standard errors: 0.012 and 0.015). These results demonstrate that, even after controlling for province-level time trends, the GFRP_Policy continues to exert a significant positive effect on UGTFEE. The consistency of these estimates with the baseline results further validates the robustness of our findings, confirming the policy’s efficacy in enhancing energy efficiency across diverse regional contexts.

Table 7.

Regression results with province-year fixed effects.

5.2.7. Robustness Check: Propensity Score Matching with Difference-in-Differences

To address potential selection bias in the GFRP_Policy, which may deviate from an ideal quasi-natural experiment due to non-random assignment of pilot cities, we employ a propensity score matching difference-in-differences (PSM-DID) approach for robustness testing. This method mitigates selection bias by matching pilot and non-pilot cities based on observable characteristics, ensuring comparability before applying the DID framework. To enhance the reliability of the matching process, we utilize both kernel matching and radius matching techniques. The results are presented in Table 8. Across both matching methods, the coefficient for the GFRP_Policy is positive (0.018) and statistically significant at the 10% level. These estimates align closely with the baseline regression results, reinforcing the positive effect of the GFRP_Policy on UGTFEE. This consistency across methodologies further validates the robustness of our baseline findings, confirming that the policy’s impact on UGTFEE is not driven by sample selection bias.

Table 8.

Results of propensity score matching.

6. Discussion

6.1. Mechanism Analysis

Our empirical results confirm that GFRP_Policy significantly enhance UGTFEE. Building on the theoretical framework outlined earlier, this section investigates the pathways through which these policies drive UGTFEE improvements, focusing on three mechanisms: green technological innovation, government environmental support, and financial deepening. Following Albert [28], we employ a two-stage mediation analysis to examine the policy’s impact on these mechanism variables. The model is specified as follows:

where i and t denote city and year, respectively, and represents the mechanism variables: green innovation capacity (lnGTI) and financial deepening (FinA). The regression results are presented in Table 9. Model 13 shows that the coefficient for GFRP_Policy on green innovation capacity is positive and significant at the 10% level, indicating that the policy fosters urban green technological innovation. In Model 14, the coefficient for financial deepening is positive and significant at the 1% level, demonstrating that the policy substantially enhances the financial system’s capacity to support low-carbon economic activities.

Table 9.

Mechanism analysis regression results.

Collectively, the results in Table 9, combined with the theoretical framework, confirm that green innovation capacity and financial deepening serve as key mediators through which GFRP_Policy enhance UGTFEE. Specifically, these policies promote UGTFEE by strengthening urban green innovation and bolstering financial institutions’ credit support for sustainable projects. These findings validate H2, underscoring the critical pathways through which green finance drives energy efficiency improvements.

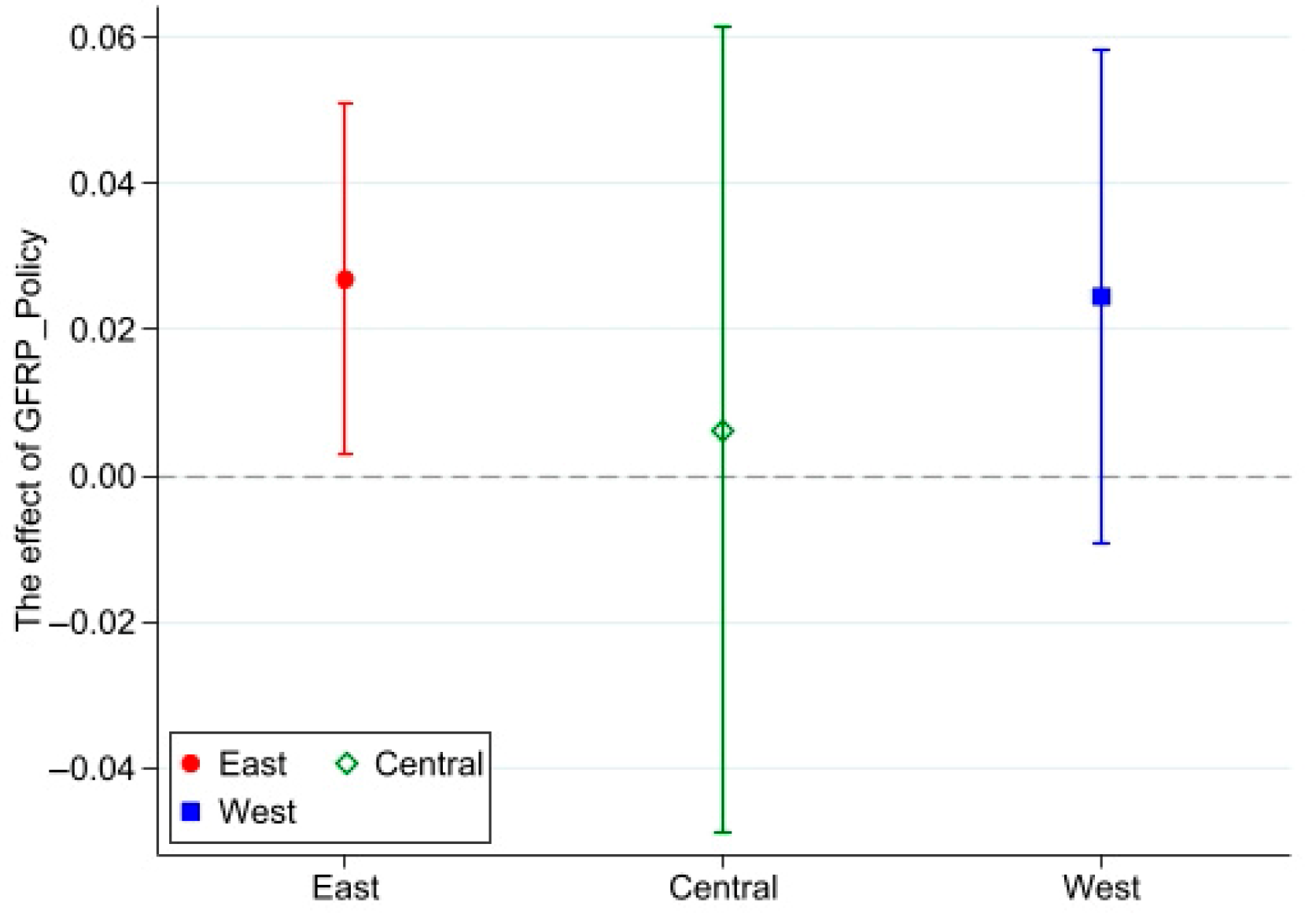

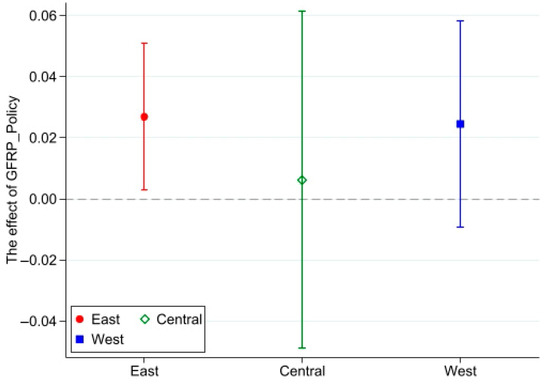

6.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

Regional disparities in financial development and green industrial bases may modulate the effectiveness of GFRP_Policy in enhancing UGTFEE [29]. Eastern regions of China, with advanced financial systems and robust environmental regulations, are better positioned to implement these policies compared to the less-developed central and western regions. To examine this, we partition the sample into eastern, central, and western regions and perform subgroup regressions. The results are reported in Model 15 to Model 17 of Table 10. The coefficient for GFRP_Policy is positive across all regions but only statistically significant in the eastern region at the 5% level, while estimates for central and western regions are insignificant. This suggests that GFRP_Policy have a more pronounced effect on UGTFEE in eastern cities, likely due to their superior financial infrastructure, stronger green industrial foundations, and more effective regulatory frameworks, which facilitate efficient capital allocation, technological diffusion, and policy implementation. In contrast, central and western regions, constrained by reliance on traditional industries, limited human capital, and less developed institutional environments, face challenges such as project misalignment and lower implementation efficiency, which hinder the full realization of policy benefits.

Table 10.

Heterogeneity test results.

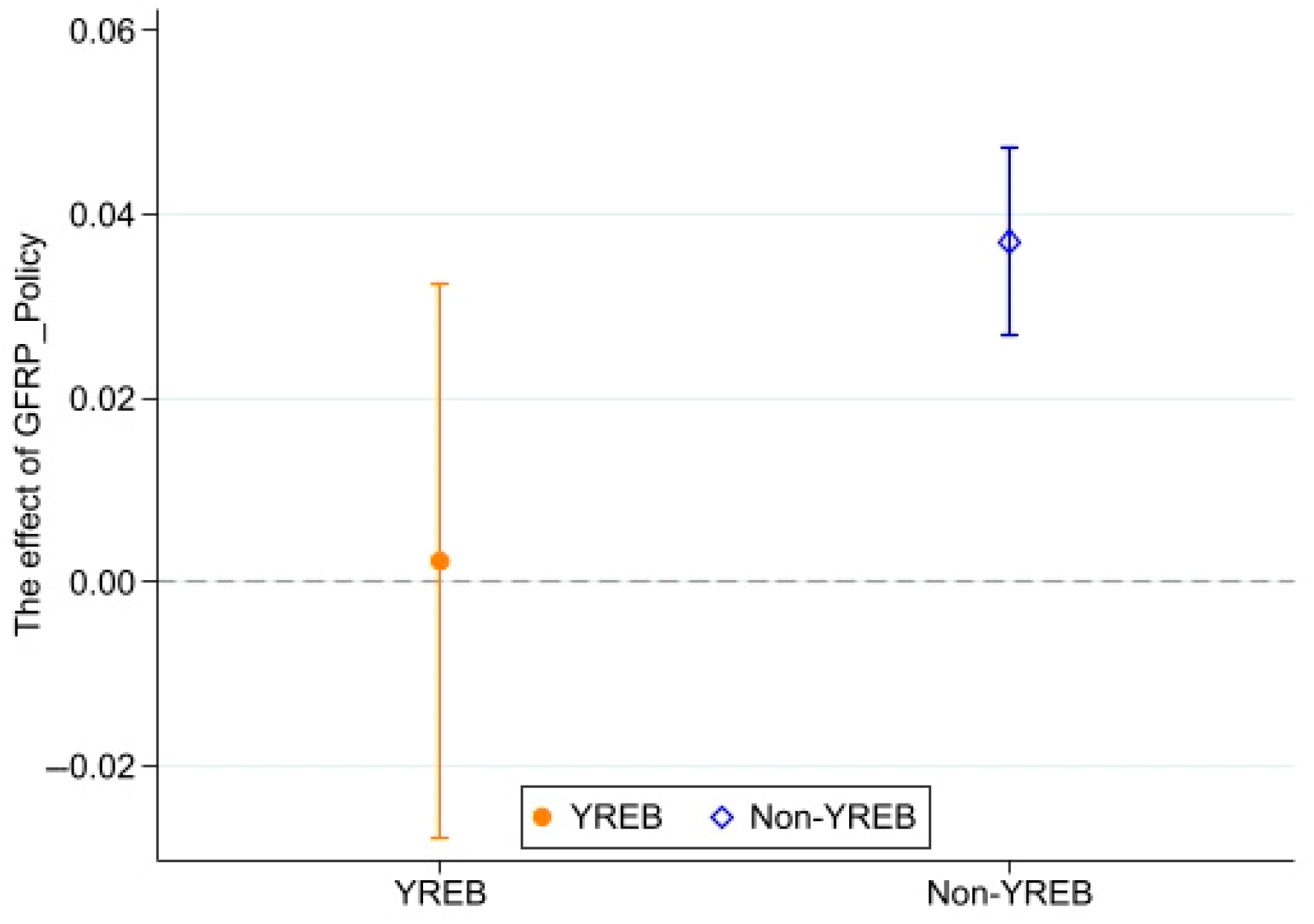

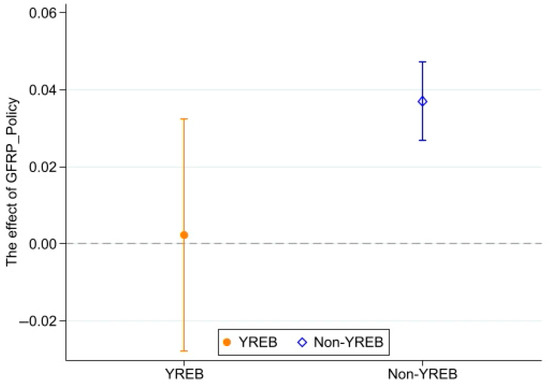

Differences in regional development strategies and institutional environments may further influence the marginal effects of GFRP_Policy. The Yangtze River Economic Belt (YREB), a national priority for ecological protection and green transition, benefits from extensive pre-existing environmental policies, potentially leading to diminishing marginal returns or policy crowding-out effects. To investigate this, we divide the sample into YREB and non-YREB cities and conduct subgroup regressions. The results are shown in Model 18 and Model 19 of Table 10. The GFRP_Policy coefficient is positive in both groups but only significant for non-YREB cities at the 1% level (0.037, standard error: 0.005), while insignificant for YREB cities (0.002, standard error: 0.015). This indicates that GFRP_Policy significantly enhances UGTFEE in non-YREB cities but have limited incremental impact in YREB cities. The muted effect in YREB cities likely stems from overlapping environmental policies, which reduce the marginal contribution of green finance initiatives, coupled with potential bottlenecks in the green transition process. Conversely, non-YREB cities, characterized by greater resource scarcity and fewer competing policy tools, exhibit stronger policy responsiveness, as green finance effectively drives technological upgrades and resource optimization in these less-developed contexts. Institutional heterogeneity analysis highlights how pre-existing policy frameworks and development stages affect policy efficacy. The YREB’s advanced green policy landscape may saturate the impact of new interventions, while non-YREB regions benefit from the targeted application of green finance, offering insights for prioritizing policy deployment in resource-constrained settings.

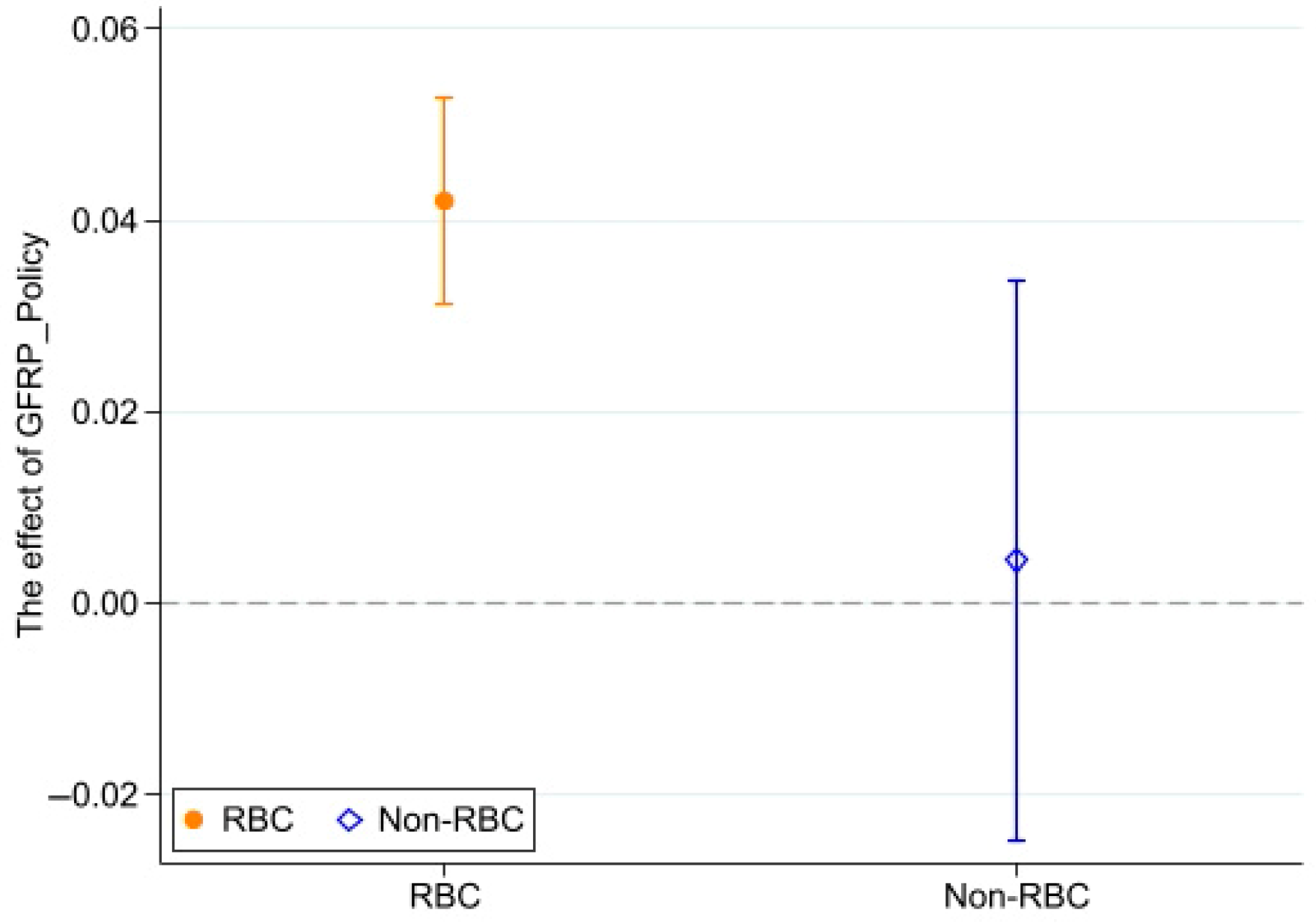

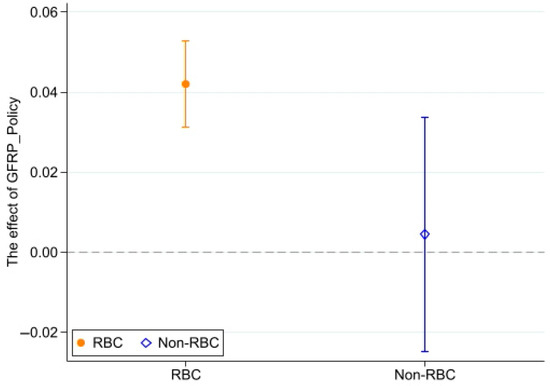

The pronounced heterogeneity in policy impact, particularly the heightened effectiveness within resource-based cities, can be profoundly understood through the lens of China’s unique institutional context. As regression results in Table 10 (Model 20 and 21) indicate, the Green Finance Reform and Innovation Pilot Zones (GFRP_Policy) significantly promotes Urban Green Total-Factor Energy Efficiency (UGTFEE) in resource-based cities (significant at the 1% level), while its effect on non-resource-based cities is limited. This disparity stems from a dual dynamic of intense institutional pressure and existential transformation demand unique to these cities.

Following the State Council’s 2013 plan for resource-based cities, these municipalities were placed under immense top-down pressure from the central government to break their path dependency on energy-intensive industries. This institutional pressure has only intensified with the rollout of China’s stringent environmental accountability systems and the ambitious “dual carbon” (carbon peaking and neutrality) targets. Consequently, these cities face not just economic but also political imperatives to transform. The GFRP_Policy, therefore, does not act in a vacuum; it serves as a crucial institutional tailwind, providing the targeted capital (via green credit and carbon finance) precisely when these cities are most compelled to seek out green technology and industrial upgrading. In contrast, non-resource-based cities, with more diversified economies and less acute environmental debt, face lower marginal urgency for such reforms. While they also operate under national environmental goals, the institutional pressure for a fundamental economic overhaul is less immediate, thus limiting the policy’s marginal impact. This analysis is further illustrated in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 4.

Heterogeneity analysis results (1).

Figure 5.

Heterogeneity analysis results (2).

Figure 6.

Heterogeneity analysis results (3).

6.3. Spatial Effects Analysis

6.3.1. Spatial Autocorrelation Test

To investigate the spatial autocorrelation of UGTFEE, this study employs the global Moran’s I index based on an inverse distance matrix, following established methodologies. As shown in Table 11, the Moran’s I values are consistently positive and significant at the 1% level across the study period (2010–2023). Notably, post-2017, following the implementation of the GFRP_Policy, the Moran’s I index exhibits an upward trend. This indicates significant spatial autocorrelation and a pronounced clustering effect in UGTFEE, where cities with higher UGTFEE tend to be geographically proximate.

Table 11.

Results of Moran’s test.

6.3.2. Selection and Validation of the Spatial Econometric Model

To select an appropriate spatial econometric model, this study conducts LM, Hausman, and LR tests, with results presented in Table 12. The LM test reveals that the LM_error statistic is significant at the 1% level, while the LM_lag statistic is insignificant. However, both robust LM_error and LM_lag tests are significant at the 1% level, indicating the presence of mixed spatial effects. Consequently, the spatial Durbin model (SDM) is selected. The Hausman and LR tests, also significant at the 1% level, confirm the suitability of a double-fixed-effects model and indicate that the SDM cannot be reduced to simpler SEM or SLM models. Thus, the double-fixed-effects SDM is adopted as the optimal spatial econometric model.

Table 12.

Spatial econometric model selection test.

6.3.3. Spatial Econometric Model Results

Table 13 reports the spatial effects of the GFRP_Policy on UGTFEE. Model 22 shows that the coefficient for GFRP_Policy is positive and significant at the 5% level, confirming a direct positive impact of the policy on UGTFEE in pilot cities. The spatial autoregressive coefficient (rho) is positive and significant at the 1% level, indicating a strong positive spatial correlation in UGTFEE—improvements in neighboring regions’ green energy efficiency tend to enhance local UGTFEE. However, the interaction term between the policy and spatial weights (WxGFRP_Policy) is significantly negative at the 1% level, suggesting a siphoning effect. This implies that the policy induces the concentration of green resources in pilot cities, thereby constraining UGTFEE improvements in surrounding non-pilot regions.

Table 13.

Regression results of spatial effects.

To avoid bias from solely examining regression coefficients, this study decomposes the policy’s impact into direct, indirect, and total effects, as shown in Model 23–Model 25 of Table 13. The direct effect, though positive, is statistically insignificant, likely due to time lags in policy implementation, which may delay the full manifestation of benefits. The indirect effect is significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating a competitive suppression effect on non-pilot cities’ UGTFEE, driven by the siphoning of resources to pilot regions. Overall, the total effect is negative and significant, as the adverse indirect effect outweighs the positive direct effect. Pilot cities, leveraging policy advantages, attract green capital, technology, and skilled labor from neighboring areas, creating a feedback loop that hinders regional UGTFEE improvement. These findings validate H3, underscoring the policy’s unintended regional disparities.

7. Conclusions

This study examines the effects of China’s green finance reform and innovation pilot zones, utilizing a quasi-natural experimental framework with panel data from 282 prefecture-level cities over the period 2010–2023. A multi-period difference-in-differences model would be employed to assess the policy’s impact on UGTFEE. The mechanisms driving UGTFEE improvements would be theoretically analyzed, with empirical validation conducted through baseline regressions. Robustness would be ensured via parallel trend tests, placebo tests, exclusion of COVID-19 effects, controls for confounding policies, and propensity score matching (PSM-DID). Mediation effect models and two-stage tests would explore the roles of green innovation, government environmental expenditure, and financial market deepening. Spatial spillover effects would be evaluated using an inverse distance matrix based on geographic weights. The principal findings are as follows:

First, the GFRP_Policy would significantly enhance UGTFEE in pilot cities. Rigorous robustness checks, including parallel trend validation and PSM-DID, would confirm the consistency of this positive effect.

Second, the GFRP_Policy would operate through three primary channels: it would strengthen urban green innovation capabilities, increase government environmental expenditure, and deepen financial markets, thereby promoting UGTFEE improvements.

Third, the policy’s effectiveness would vary due to differences in geographical locations, environmental regulations and resource endowments across different regions. Greater impacts would be observed in eastern China, where advanced financial and industrial ecosystems exist. In regions with stringent environmental regulations, such as the Yangtze Economic Belt, crowding-out effects might occur, making the policy more effective in areas with weaker regulatory frameworks. Resource-based cities, due to their long-term reliance on energy-intensive industries, are facing more severe pressure for industrial transformation, which enables the policy effects to be more effectively unleashed.

Fourth, negative spatial spillover effects would arise from the policy’s implementation. While UGTFEE in pilot cities would improve, a siphoning effect might concentrate green resources or displace low-end polluting industries to non-pilot regions, thereby suppressing UGTFEE in surrounding areas.

8. Policy Recommendations

Based on these findings, the following strategies would be proposed to enhance the efficacy of green finance reforms and mitigate unintended consequences:

First, a comprehensive evaluation of the green finance pilot zones’ outcomes and experiences would be conducted to develop a replicable policy framework. This framework could guide the phased, context-specific expansion of the policy to new regions, ensuring sustained UGTFEE improvements tailored to local conditions.

Second, differentiated policy designs would be implemented to address regional and institutional variations. In eastern regions, green financial markets could be strengthened through instruments like carbon futures and cross-border green technology financing, particularly in urban clusters such as the Yangtze River Delta and Greater Bay Area. In areas with robust environmental regulations, such as the Yangtze Economic Belt, policy exit mechanisms might be introduced, shifting from universal subsidies to incentives for green technology R&D. In less-regulated central and western regions, targeted bonds or loans could support energy transitions and ecological restoration, while resource-intensive enterprises might be integrated into provincial environmental credit systems, linking carbon reduction performance to financing costs.

Third, government intervention would be strengthened to foster innovation and investment. Increased environmental expenditure, dedicated funds, and incentives for enterprises to pursue green technology upgrades could be prioritized. Collaboration with financial institutions to expand green credit and bond issuance might provide capital for industrial transformation, guiding low-end firms toward high-value, green operations to enhance UGTFEE.

Fourth, regional cooperation mechanisms would be innovated to counteract negative spatial spillovers. A “green finance collaboration zone” framework could be established within national urban clusters, such as the Yangtze River Delta and Greater Bay Area, to clarify joint pollution control responsibilities. Policies might prohibit pilot cities from using tax incentives to relocate low-end industries and reduce subsidies for both transferring and receiving regions. Cross-regional financial tools, such as targeted green bonds or specialized loans, could support environmental restoration and industrial upgrades in non-pilot areas, fostering a cooperative model of shared responsibility and mutual benefits to replace zero-sum competition.

This Nature-style presentation clarifies the thematic focus, maintains complete sentences in the subjunctive mood, and ensures logical coherence, aligning recommendations with empirical findings to address both local and regional impacts effectively.

9. Limitations

This study acknowledges several limitations that also point to directions for future research. The primary and most critical limitation lies in the construction of our core dependent variable, UGTFEE: we failed to include carbon dioxide emissions as an undesirable output, which, in the current context of the “dual carbo” strategy, diminishes the comprehensiveness and policy relevance of the indicator. Future research must rectify and enhance this aspect. Second, the analysis is constrained by its reliance on prefecture-level city macro-data, which may mask significant intra-city heterogeneity; employing more micro-level data from firms or counties will be a crucial direction for future in-depth research. Finally, although we employed a Difference-in-Differences model and an instrumental variable approach to mitigate endogeneity, the exogeneity of any instrumental variable is a strong assumption, and unobserved time-varying factors (such as local political priorities) may still influence the results. Therefore, supplementing and validating the quantitative findings with qualitative case studies represents a valuable path for future exploration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.S. (Weijia Shao); methodology, W.S. (Weiming Sun); software, W.S. (Weijia Shao); formal analysis, W.S. (Weijia Shao); writing—original draft preparation, W.S. (Weijia Shao); writing—review and editing, W.S. (Weijia Shao), W.S. (Weiming Sun). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Feng, C.; Zhong, S.; Wang, M. How can green finance promote the transformation of China’s economic growth momentum? A perspective from internal structures of green total-factor productivity. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 70, 102356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Shen, Y.; Du, Q. Can green credit policy promote green total factor productivity? Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 6891–6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Qi, S.; Li, Y. China’s green finance and total factor energy efficiency. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 10, 1076050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, M.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S. How does green finance improve the total factor energy efficiency? Capturing the mediating role of green management innovation and embodied technological progress. Energy Econ. 2025, 142, 108157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Bo, Y.; Lei, Y. Green financial policy, environmental regulation, and energy use efficiency. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 74, 106711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Feng, S.; Yang, Y.; He, Y. Total Factor Energy Efficiency and Its Measurement, Comparison, and Validation. Resour. Sci. 2023, 45, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Sun, T.; Zhou, P. Evaluation of China Regional Total Factor Energy Efficiency and Its Spatial Convergence Based on the Improved Undesirable SBM Model. Syst. Eng. 2015, 33, 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Yu, L.; Sun, C. How do the National Eco-Industrial Demonstration Parks affect urban total factor energy efficiency? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. Energy Econ. 2023, 126, 107018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Assoc Computing, M. Digital Transformation, Green Innovation, and Green Total Factor Energy Efficiency: Based on Empirical Evidence from Listed Companies in China A-Share Market. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on E-Business Management and Economics (ICEME 2024), Beijing, China, 19–21 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, S.W.; Zhang, P.F.; Chen, S.; Yang, Y. Digital village construction and depressive symptoms in rural middle-aged and older adults: Evidence from China. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 372, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Wang, M.; Yu, S. Impact of Innovation-Driven Policies on Total Factor Energy Efficiency: Based on the National Innovation City Pilot Policy. Resour. Sci. 2023, 45, 1884–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.-t.; Dong, Y.; Feng, B.; Zhang, H. Can green finance development promote total-factor energy efficiency? Empirical evidence from China based on a spatial Durbin model. Energy Policy 2023, 177, 113523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhang, L.; Dong, Z. Exploring the effect of green finance on green development of China’s energy-intensive industry—A spatial econometric analysis. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2024, 16, 100159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Wang, S.; Cheng, X.; Li, L. Green finance and total factor energy efficiency: Theoretical mechanisms and empirical tests. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1399056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Li, Y. The role of combinatorial green finance policies in improving total factor energy efficiency: Evidence from Chinese cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 526, 146681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, G.D.; Liu, Y.Y.; Fang, H.; Xiu, Y.Y. Tapping the potential of green finance: Can energy efficiency credit drive traditional industries to green? Evid. China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 87, 1834–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Zhao, P. Does Green Finance Promote Green Total Factor Productivity? Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Wu, D.; Qian, W. Eco-Efficiency Evaluation and Productivity Change of Yangtze River Economic Belt in China: A Meta-Frontier Malmquist-Luenberger Index Perspective. Energy Effic. 2023, 16, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Xiang, Y.; Xiong, L. Driving Forces and Obstacles Analysis of Urban High-Quality Development in Chengdu. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcand, J.L.; Berkes, E.; Panizza, U. Too much finance? J. Econ. Growth 2015, 20, 105–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Toh, M.Y.; Zhao, J.Z. Green Growth in Pilot Zones for Green Finance and Innovation. Energy Policy 2025, 202, 114611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.W.; Zhou, Y.B.; Zhou, L.; Chen, S.; Qi, F.X. The impact of new energy demonstration city policy on the mental health of middle-aged and older adults. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2025, 58, 101518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Du, J.; Ran, D.; Yi, C. Spatio-Temporal Distribution and Evolution of the Tujia Traditional Settlements in China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Q.; Mo, J.; Liu, Z.; Gong, C.; Fan, Y. Using Green Finance to Counteract the Adverse Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Renewable Energy Investment—The Case of Offshore Wind Power in China. Energy Policy 2021, 158, 112542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y.; Sun, S.; Wei, N.; Sun, B.; Ni, J.; He, J.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, J.; et al. Evaluating Traffic Emission Control Policies Based on Large-Scale and Real-Time Data: A Case Study in Central China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 860, 160435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.W.; Ke, S.F.; Liang, C. How the talent ecosystem of key state-owned forest areas in China empowers forestry scientific and technological talents aggregation. For. Policy Econ. 2025, 170, 103400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kang, K.H. The Interaction Effect of Tourism and Foreign Direct Investment on Urban–Rural Income Disparity in China: A Comparison between Autonomous Regions and Other Provinces. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, J.M. Mediation Analysis via Potential Outcomes Models. Stat. Med. 2008, 27, 1282–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Ye, T.; Tian, S.; Wang, X. Reexamining Spatiotemporal Disparities of Financial Development in China Based on Functional Data Analysis. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).