1. Introduction

Aging is a biological and social phenomenon inherent to humanity and, in this century, it is facing new realities [

1,

2]. With the notable increase in the population over 65 years old, which could reach 30% of the global population by 2050 [

3], challenges and opportunities emerge that require a holistic approach. For the purposes of this study, and in line with the categorization used by the Portuguese National Institute of Statistics (INE)—our primary data source—the term “senior” refers to individuals aged 65 and over. This growth is the result of advances in medicine and social policies in the 20th century, such as improved healthcare and more robust pension policies, which significantly extended life expectancy [

1,

2].

This demographic change drives the need to rethink sectoral policies to address the biopsychosocial and even ecological requirements of this population segment. The concept of “active aging”, defined at the United Nations Second World Assembly (2002) [

1], in Madrid, serves as a central paradigm for optimizing the health, participation, and safety of older people, ultimately improving their quality of life.

Accumulated wealth and technological developments have also led to an increase in free time among older people, allowing them greater access to leisure activities and creativity. Senior tourism emerges, in this context, as a factor that not only promotes active aging [

1,

4] but also as an indicator of quality of life [

5,

6] and social distinction (Cf. [

7]). This sector has the potential to positively impact the physical and mental health of the elderly [

4,

8,

9] and to combat social isolation through the creation of relationship networks [

10,

11].

Tourism, as a strategic sector with high growth margins [

12], faces the opportunity and challenge of adapting to the specific needs of the elderly [

13,

14]. The demand for diversified leisure activities is driven by the growing economic, political, and social visibility of older people [

7,

15], which implies the need for varied tourism products, ranging from health and wellness trips to cultural and recreational tourism [

4,

13,

16].

Despite a growing body of literature on the benefits of senior tourism, a significant research gap persists: there is a lack of quantitative, forward-looking studies that model future trends and provide concrete projections, particularly within specific national contexts like Portugal. Much of the existing research is either qualitative or descriptive, without offering the predictive insights needed for long-term policy and business planning. To address this gap, this study has a dual objective. First, it quantitatively analyzes the correlation between tourism and key demographic and travel-related indicators for seniors. Second, it develops predictive models to forecast the future of this sector, with a specific focus on its gendered dynamics. While the empirical analysis is centered on Portugal, its demographic profile as a rapidly aging society makes it an ideal case study for providing a methodological blueprint and actionable insights relevant to other nations facing similar demographic shifts.

To guide our empirical analysis, we formulated the following research hypotheses based on the theoretical framework and existing literature:H1: There is a significant positive correlation between the volume of senior tourism and key national economic indicators, such as GDP and overall resident travel.H2: Women aged 65 and over exhibit a significantly higher frequency of participation in tourism activities compared to their male counterparts.H3: The time series for senior tourism demonstrates a significant positive long-term trend, although this trend is susceptible to temporary disruptions from major external shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.1. Aging in the 21st Century: Challenges and New Paradigms

Aging is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, both individual and collective, that represents one of the greatest challenges of the 21st century. This challenge is amplified by the ongoing demographic transformation, which is a direct consequence of the reduction in birth and death rates, the increase in average life expectancy, and advances in medicine and living conditions. In 2012, around 11% of the world’s population was over 60; it is estimated that, within three decades, this percentage will rise to approximately 30%, a fact corroborated by the inversion of the European age pyramid [

3].

The changing demographics of society have significant consequences on how society is organized [

3] and interacts closely with individual forms of aging, which are inherently dynamic and influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors [

2]. In other words, individual and demographic aging are interconnected and shape each other. The social structure of each society has an impact on aging at an individual level, while the aging of the population exerts pressure to transform social statuses and participation opportunities for the elderly.

In this scenario, the concept of Active Aging gains relevance. Proposed by the WHO [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], this paradigm goes beyond healthy aging, integrating not only health aspects but also socioeconomic, psychological, and environmental considerations. It is based on pillars such as autonomy, independence, healthy life expectancy, and quality of life. These pillars promote individual proactivity, encouraging people to make decisions about their own lives in accordance with their personal rules and preferences, to live autonomously in the community, and to enhance their physical, social, and mental quality of life [

17,

19,

20].

Highlighting the importance of dignity, participation, and self-realization, Active Aging aims to maximize quality of life and responsible citizenship for the elderly. This vision recognizes and respects the human rights of seniors, following the principles established by the UN [

1], and promotes positive and adaptive aging, in which seniors can remain involved in social, economic, cultural, and civil life as per their interests, needs, and capabilities. Therefore, the approach to aging in the 21st century requires an integrated understanding and coordinated action to respond to the challenges and opportunities that this inevitable demographic transformation brings [

21,

22].

1.2. Aging and Quality of Life

The Active Aging paradigm, discussed previously, finds its ultimate purpose and measure of success in enhancing quality of life. This connection is fundamental, as the concept of successful aging, which strengthened throughout the 20th century, is inextricably linked to quality of life in multiple domains [

1]. This notion was reinforced by several theoretical models, although Havighurst’s pioneering definition [

23] already emphasized the importance of physical and social activity for seniors. In fact, maintaining a healthy and proactive lifestyle, with robust physical and mental activity, has become a recurring emphasis in scientific and social approaches to aging [

24,

25].

These principles are in line with the life cycle approach, which proposes flexibility in the traditional phases of life—education, work, and retirement—especially for the senior population. This approach is even more relevant considering global demographic change; The United Nations predicts that by 2050, seniors will represent around 21% of the world’s population. This phenomenon is driven by factors such as the increase in average life expectancy and the decrease in mortality and birth rates [

3].

At the same time, there is a growing trend in tourism among seniors, confirmed by studies that indicate a significant increase in their participation in this activity. Tourism offers diverse opportunities for personal enrichment and socialization, factors that are highly beneficial for the quality of life of older people.

Quality of life, as a concept, is multidimensional and subjective, covering everything from physical health to emotional quality of life and social relationships [

26,

27]. It is influenced by multiple factors, ranging from genetic to environmental, cultural, and social aspects, as Duque points out [

28,

29]. The concept is also a social construction, shaped by cultural values and personal expectations, which interact with the context in which the individual lives [

30].

Successful aging is, therefore, a complex and multifaceted process, influenced by both internal and external factors [

31,

32]. It requires a proactive approach to maintaining a healthy lifestyle and is profoundly impacted by social and historical context. In this scenario, tourism emerges as a powerful mechanism to reinforce quality of life in old age, which, in turn, contributes to healthier and more rewarding aging [

33,

34]. Indeed, the recent literature has increasingly explored this interdisciplinary connection. Systematic reviews, such as that by Chang et al. [

35], document the progress in research on seniors’ quality of life in tourism contexts, while authors like Hu et al. [

4] have developed conceptual models explaining the role of tourism in healthy aging. Furthermore, research highlights tourism’s importance for mental health and psychological quality of life in this life stage, as noted by Buckley [

34].

Therefore, the link between active aging and quality of life is not merely a theoretical construct; it requires practical pathways for implementation. It is within this context that senior tourism emerges as the central focus of this study. Unlike other interventions, tourism provides a unique, multidimensional platform that simultaneously addresses physical activity, mental stimulation, and social engagement—core components of the WHO’s framework [

1]. Recent integrative models, such as the

Active Ageing Index championed by Zaidi [

18] and the conceptual frameworks proposed by Hu et al. [

4], provide the necessary conceptual glue, positioning leisure and travel not as peripheral activities but as central strategies for achieving a high-quality later life. The following section will thus analyze tourism and leisure specifically as the catalysts that bridge the gap between policy ideals and tangible quality of life.

1.3. Tourism and Leisure in the Third Age: A Catalyst for Active Aging and Economic Sustainability

The European Union recognizes the significant impact of population aging on various sectors, including economic, political, and social. This concern is not only demographic, but is also intrinsically linked to quality of life, especially with regard to the use of free time. Studies have indicated that leisure activities play a vital role in the psychological and social quality of life of the elderly [

10,

36], with equally notable positive effects on cognitive health, especially when performed in groups.

In this context, tourism and leisure emerge as booming industries with increasingly significant economic contributions at a global level. The senior population segment becomes particularly relevant here, as it represents a growing share of the clientele that seek tourism products as a preferred way of occupying their free time. This culminated in the emergence of the concept of “senior tourism”, which, drawing on authors like Cavaco [

7] and Tsartsara [

16], is defined as tourism activities specifically planned for older adults (aged 65+), often characterized by adjusted services, health considerations, and lower seasonality [

37,

38].

The heterogeneity of the senior group, both in terms of age and lifestyle, makes the market even more complex and promising. This diversity manifests itself not only in levels of activity, disposable income, and free time but also in continuous participation in the labour market, whether formal or informal [

15,

39]. This complexity provides new opportunities, challenges, and responsibilities, both for the tourism sector and for active aging policies, opening space for the social integration of older people and overcoming difficulties associated with aging [

40,

41,

42].

The World Tourism Organization estimates that, by 2050, the number of senior travelers will exceed 2 billion, which implies a growing need to adapt the tourist offer to satisfy a demand that is not only voluminous but also diverse in income, interests, and motivations [

43,

44].

Therefore, senior tourism is not only a response to the needs of an aging society but also a strategy for sustainable economic development. The sector’s adaptability and inclusivity become crucial, ranging from accessible facilities to specific healthcare [

12,

13], because, as Martins, Guerra & Azeredo [

6] conclude, increasing average life expectancy only becomes a significant objective if quality of life is maintained. Therefore, senior tourism not only promotes active aging but also contributes significantly to the economy and society as a whole.

2. Materials and Methods

Our analysis is methodologically grounded in secondary data from the Portuguese National Institute of Statistics (INE). The selection of variables—such as GDP, trip duration, and household composition—was guided by two primary criteria: their established relevance in the literature on tourism demand determinants and their consistent availability within the INE datasets. The study was structured into two analytical phases, each with a specific time frame chosen for its analytical suitability. For the correlational analysis (Phase 1), we used annual data from 2001 to 2020. This 20-year period was chosen to provide a long-term perspective on the structural relationships between senior travel and key socioeconomic indicators. For time-series modeling and forecasting (Phase 2), we utilized more granular monthly data from 2009 to 2020. This latter period was selected for its data completeness, making it ideal for building robust predictive models and establishing a clear pre-pandemic baseline for trend analysis.

Statistical data were coded and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 29.0 software.

In the first phase, we focused on analyzing the correlation between the number of people in this age group who travelled and a series of economic and social variables. We used Pearson’s correlation coefficient to evaluate the linear relationship between the variables in question, which included the GDP of Portugal and the European Union and total tourist trips, among others. This analysis allowed us to understand the weight of each variable in the decision to travel of people aged 65 and over.

In the second stage, our focus changed to a more detailed analysis of time series, with monthly data collected between 2009 and 2020, equivalent to 144 observations. Initially, we carried out a graphical analysis to identify the three basic components of each series: trend, seasonality, and random behaviour. Furthermore, we applied the Student’s t-test to compare travel patterns between men and women.

Based on the information collected, we moved on to statistical modeling of the data using ARIMA models, which were adjusted using the maximum likelihood estimation method. These models allowed us not only to understand the variability of the data but also to make reliable predictions for the future behaviour of the series until 2025 and 2030.

Finally, after validating the statistical quality and adjustment of the chosen model, we concluded the study with travel projections for the years 2025 and 2030, providing a solid basis for future decisions within the scope of senior tourism in Portugal.

3. Results

The first phase of our analysis focused on exploring correlations using 20 years of annual records, spanning from 2001 to 2020. The descriptive statistics (mean values and standard deviations) and Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) for the variables under study are presented in

Table 1 (

n = 20). One of the central points of this correlational analysis is the number of people aged 65 or over who travelled and its relationship with other relevant variables [see

Table 1].

By using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) statistics, we found that this age group has a significant positive correlation with the total number of tourist trips undertaken by residents in Portugal. Specifically, the correlation coefficient is r = 0.637 with a

p-value of less than 0.01, and r = 0.608 with a

p-value of less than 0.001, in relation to the total number of tourist trips by residents in Portugal. In other words, when the number of residents traveling increases, there is also an increase in the number of people aged 65 and over traveling and vice versa [see

Table 1].

Furthermore, there is a strong association between the number of people aged 65 and over who travel and the length of stay in Portugal. The data show robust correlations for stays of 1 to 3 nights (r = 0.608,

p-value < 0.01), 4 to 5 nights (r = 0.667,

p-value < 0.01), and 8 to 14 nights (r = 0.508,

p-value < 0.01) [see

Table 1].

When it comes to traveling abroad, the correlation is also notable. The correlation coefficient is r = 0.573 with a p-value less than 0.05 for the total number of tourist trips abroad by residents. Stays of 1 to 3 nights (r = 0.660, p-value < 0.01), 4 to 5 nights (r = 0.510, p-value < 0.05), and 8 to 14 nights (r = 0.574, p-value < 0.05) also show strong associations.

Finally, the analysis shows that there is a positive correlation (r = 0.487,

p-value < 0.05) between the number of single-person households aged 65 or over and the number of people in this age group who travel. The greater the percentage of single-person households aged 65 or over, the greater the likelihood of people in this age group traveling (See

Table 1).

This set of statistically significant correlations provides a comprehensive look at the travel patterns of people aged 65 and over, highlighting the impact of several related variables.

3.1. Descriptive and Exploratory Analysis of Time Series

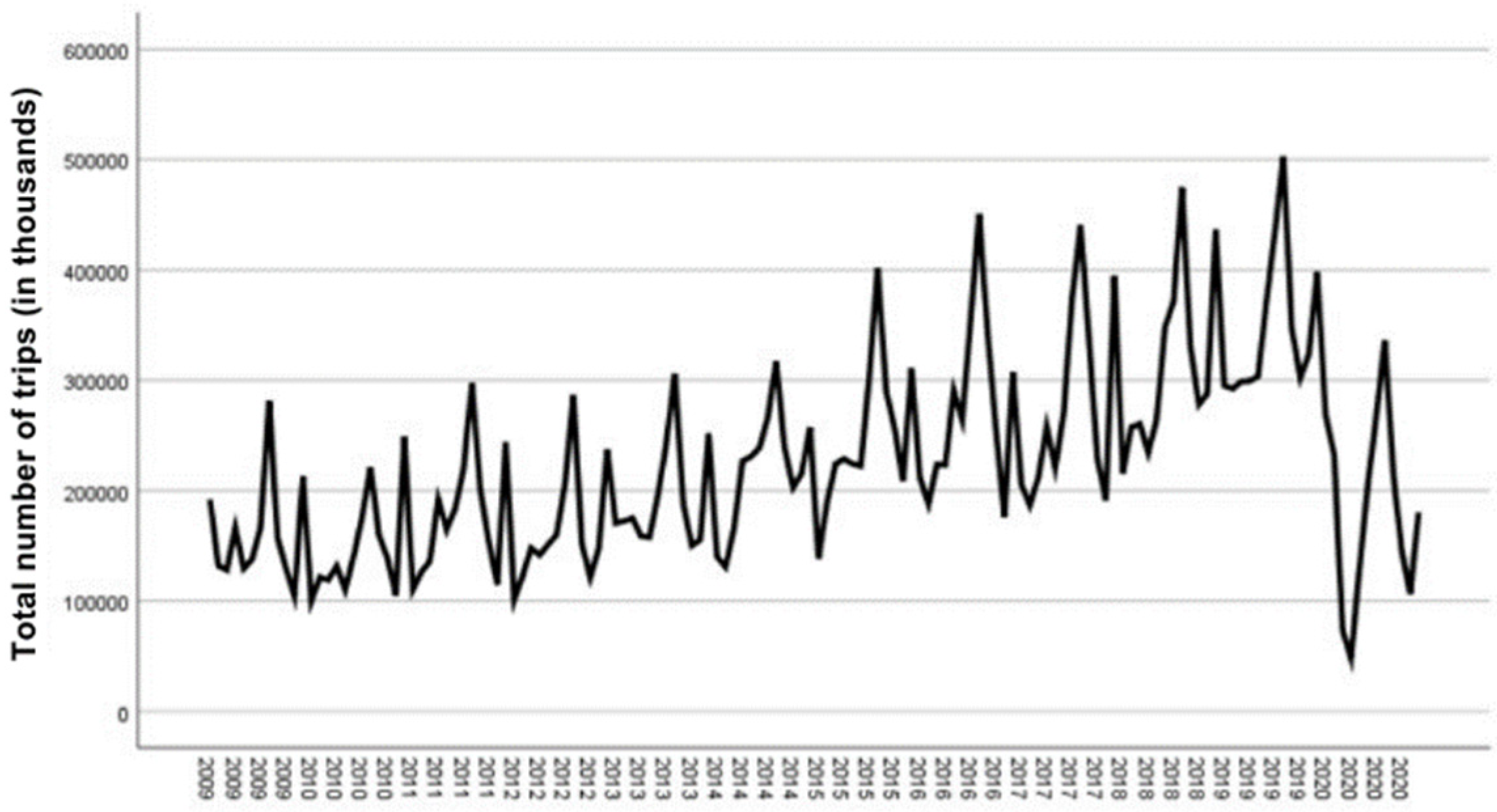

The analysis of the three-time series—total, men, and women—reveals an increasing trajectory over time, with one notable exception: an abrupt drop at the beginning of 2020. This decline synchronizes with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to the global growth trend, the series exhibit seasonal behaviour that repeats annually, with variations in the magnitude of travel numbers between gender groups. It is important to note that the total series is derived from the aggregation of the series for men and women [see

Figure 1].

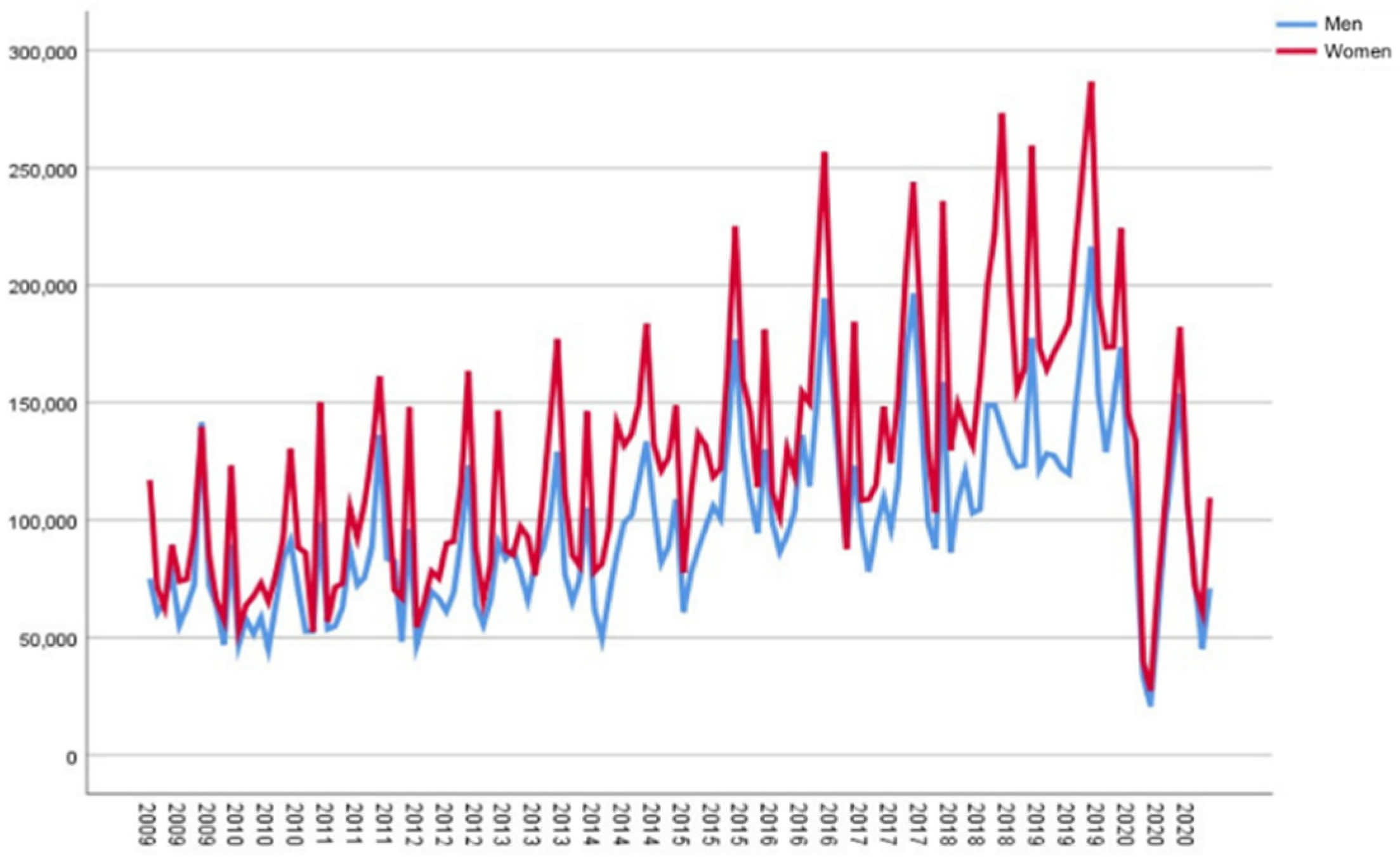

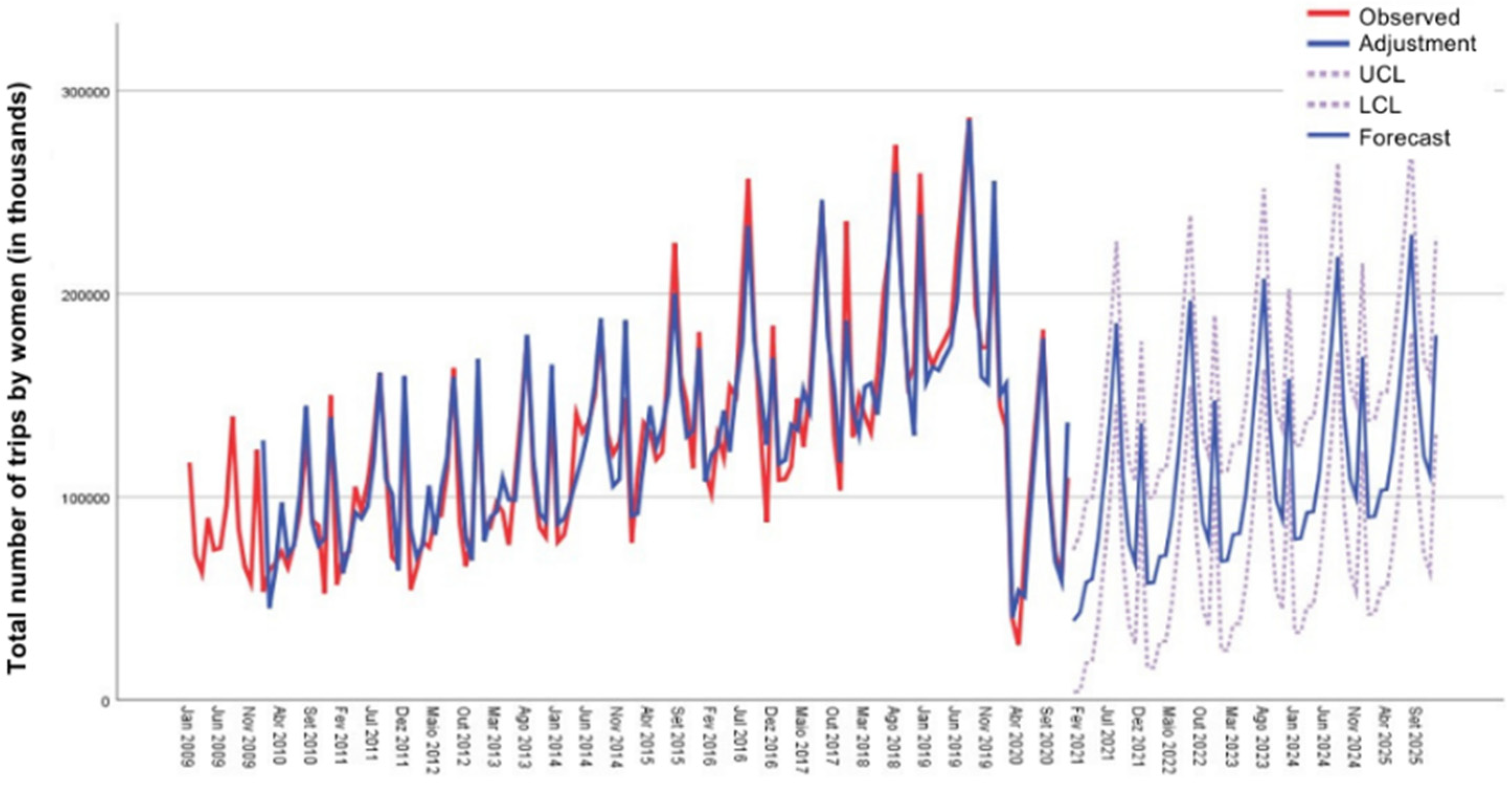

Moving on to a specific comparison between the series of men and women, it appears that women tend to travel more frequently (see

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). This observation is statistically supported by a

t-test at a 5% significance level, resulting in t(143) = −16.589, with a

p-value < 0.05. In practical terms, women make, on average, 29,278 more trips than men over the 12-year period analyzed.

Consequently, to model these series appropriately, parameters will be needed that capture the underlying trend, account for seasonal effects, and filter out the noise inherent in the data. The implementation of these elements is crucial to ensure the stationarity of the series, a prerequisite for making robust temporal forecasts.

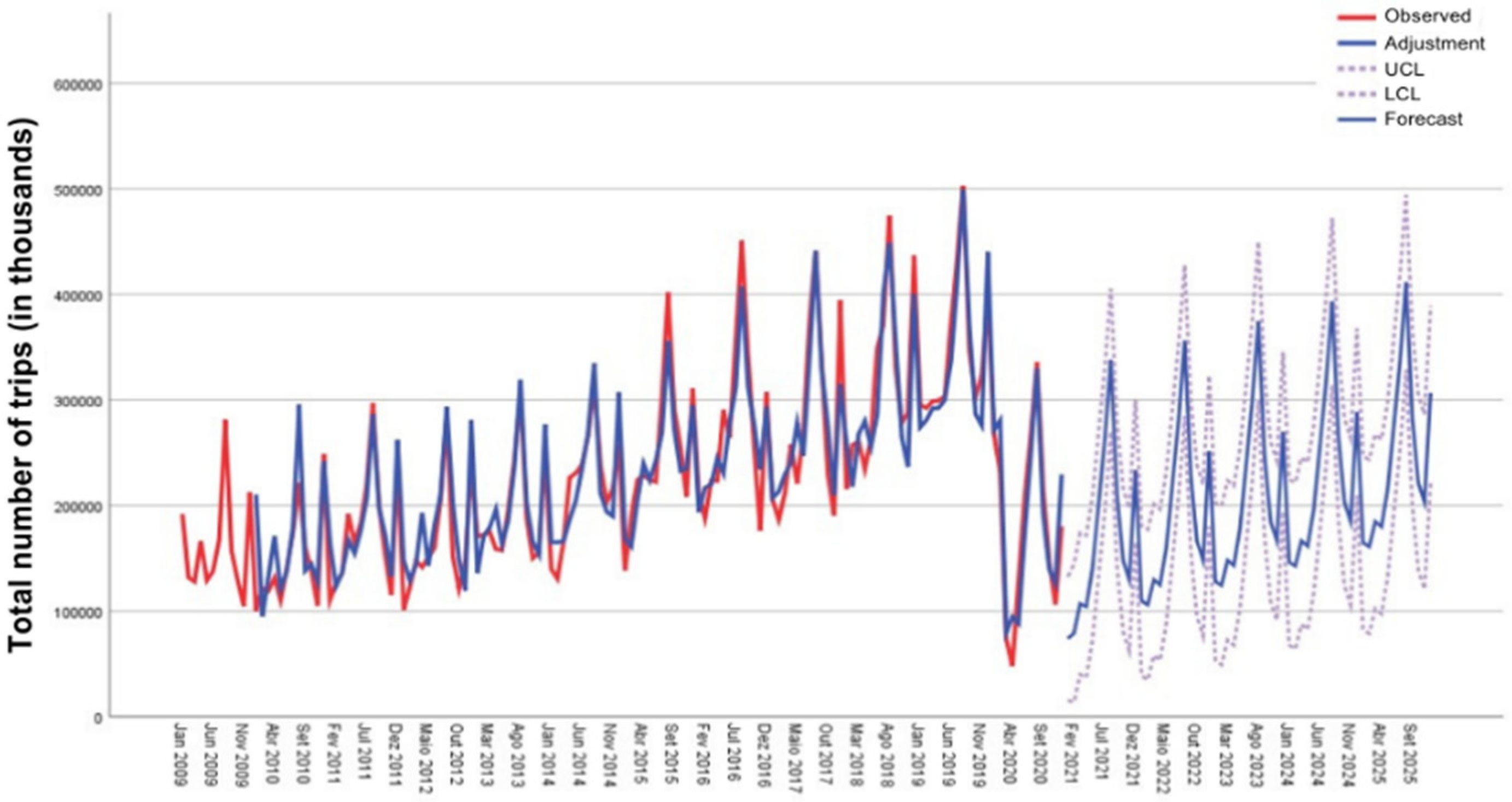

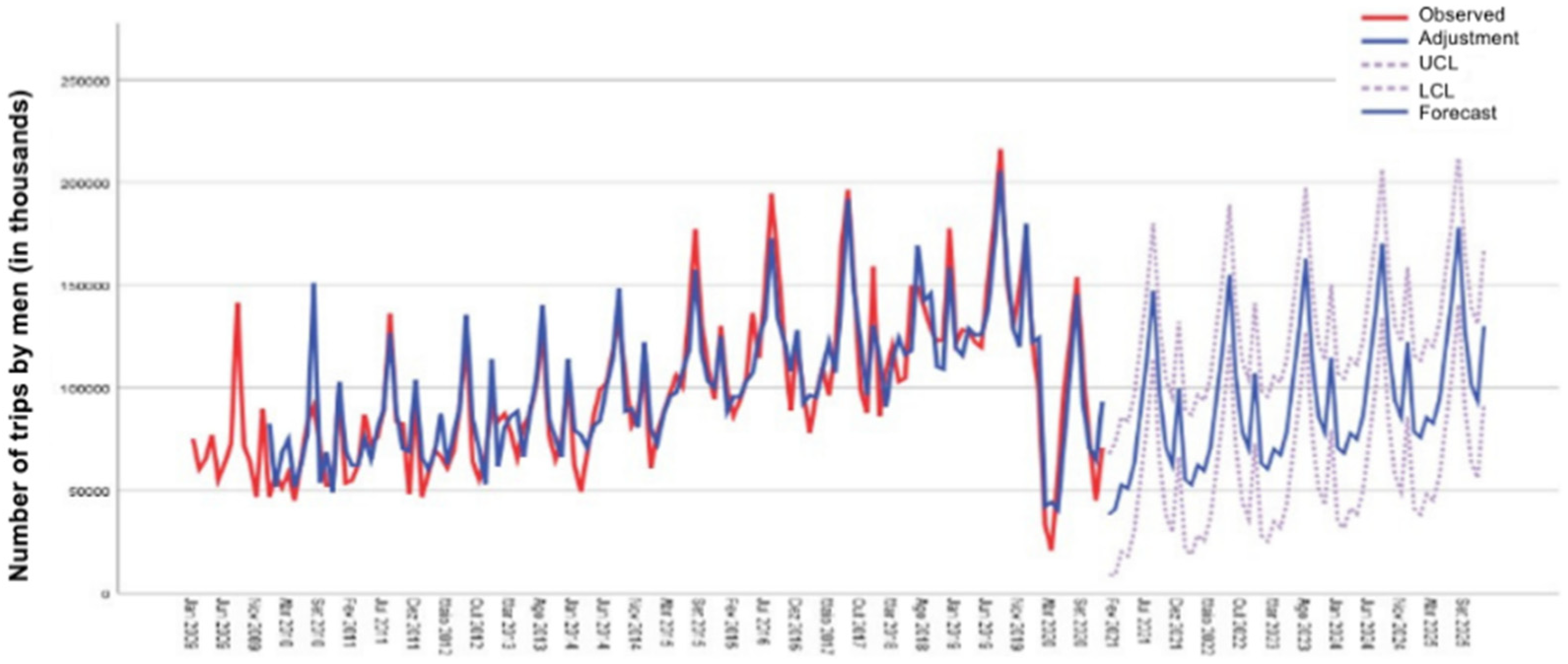

3.2. Model Estimation for 5 Years (2025)

For the projection until 2025, the three observed time series were subjected to an ARIMA analysis to decipher their random and seasonal components. Specifically, the data were fit to an ARIMA model (1,0,0) (0,1,1)

m with statistically significant parameters, evidenced by a

p-value lower than 0.01 [see

Figure 4 and

Figure 5].

The graphical forecasts up to 2025 for the men’s and women’s series are presented in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, respectively.

Regarding the trend component, the adjustment followed an AR(1) model with t = 6.173 and a

p-value < 0.01. Seasonality, in turn, was modelled through a degree of differentiation and a moving average, both unitary (MA(1)). This model proved to be significant both for the total series of trips and for the series separated by gender, with a

p-value below 0.01 in all cases [see

Table 2].

It is worth noting that anomalies in the data, particularly in March 2020 for the total series and for women, and additionally in August 2018 for men, were incorporated into the model through an additive method.

The effectiveness of the models was substantial, with an R

2 stationary at around 73% for the men’s series and 80% for the total and women’s series. According to the Ljung–Box test, the temporal independence of the residues was confirmed, as the analysis failed to reject the null hypothesis of randomness (

p-value lower than 0.05 for all series) [see

Table 3].

In terms of quality of fit, measures such as Mean Squared Error (REMQ), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) indicated better fits for the series of men and women compared to the total series.

Finally, a graphical inspection of the standardized residuals revealed no discernible pattern, corroborated by the Autocorrelation Function (ACF) graph of the residuals, which fell within the limits of a 95% Confidence Interval. This result suggests that the residuals can be treated as white noise.

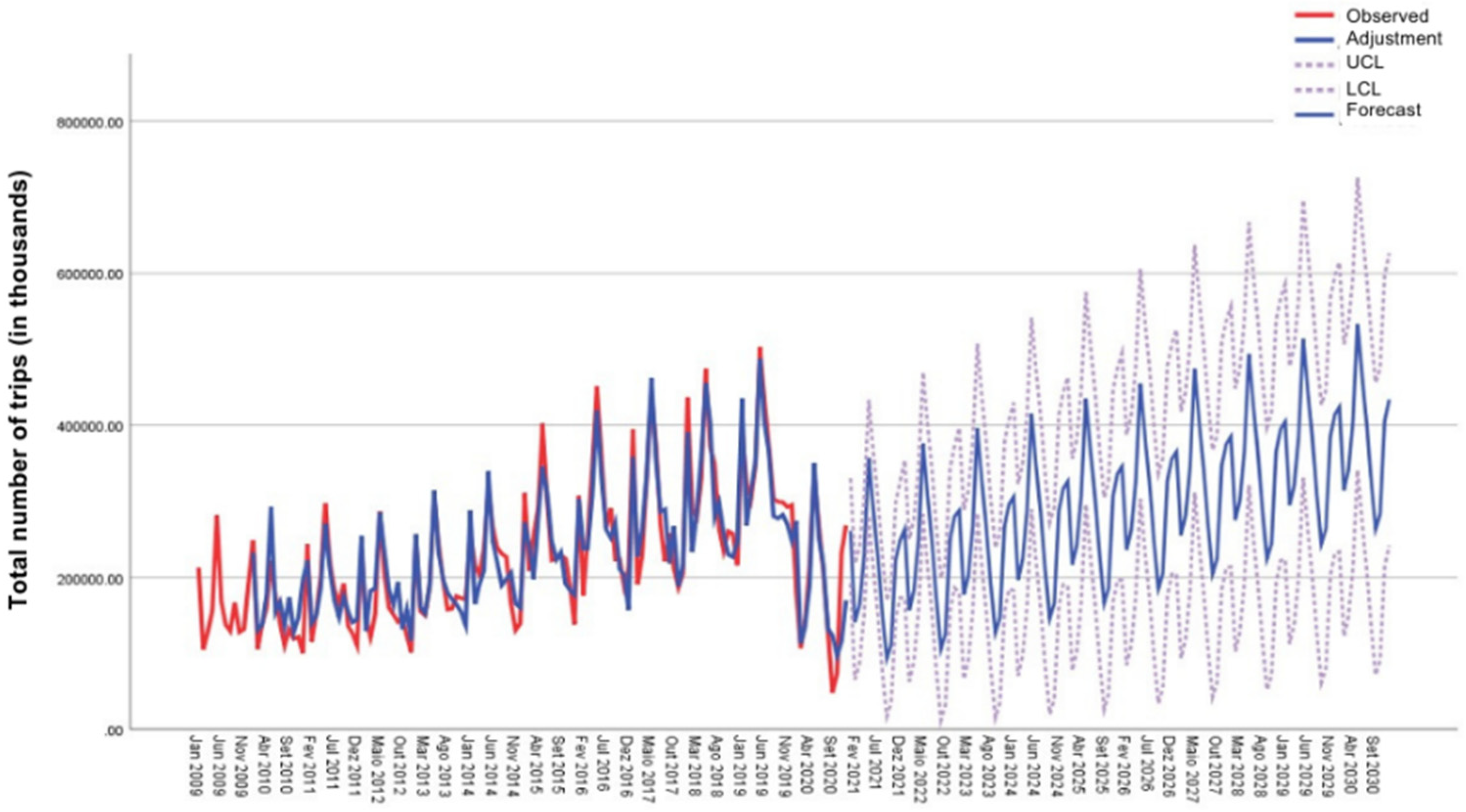

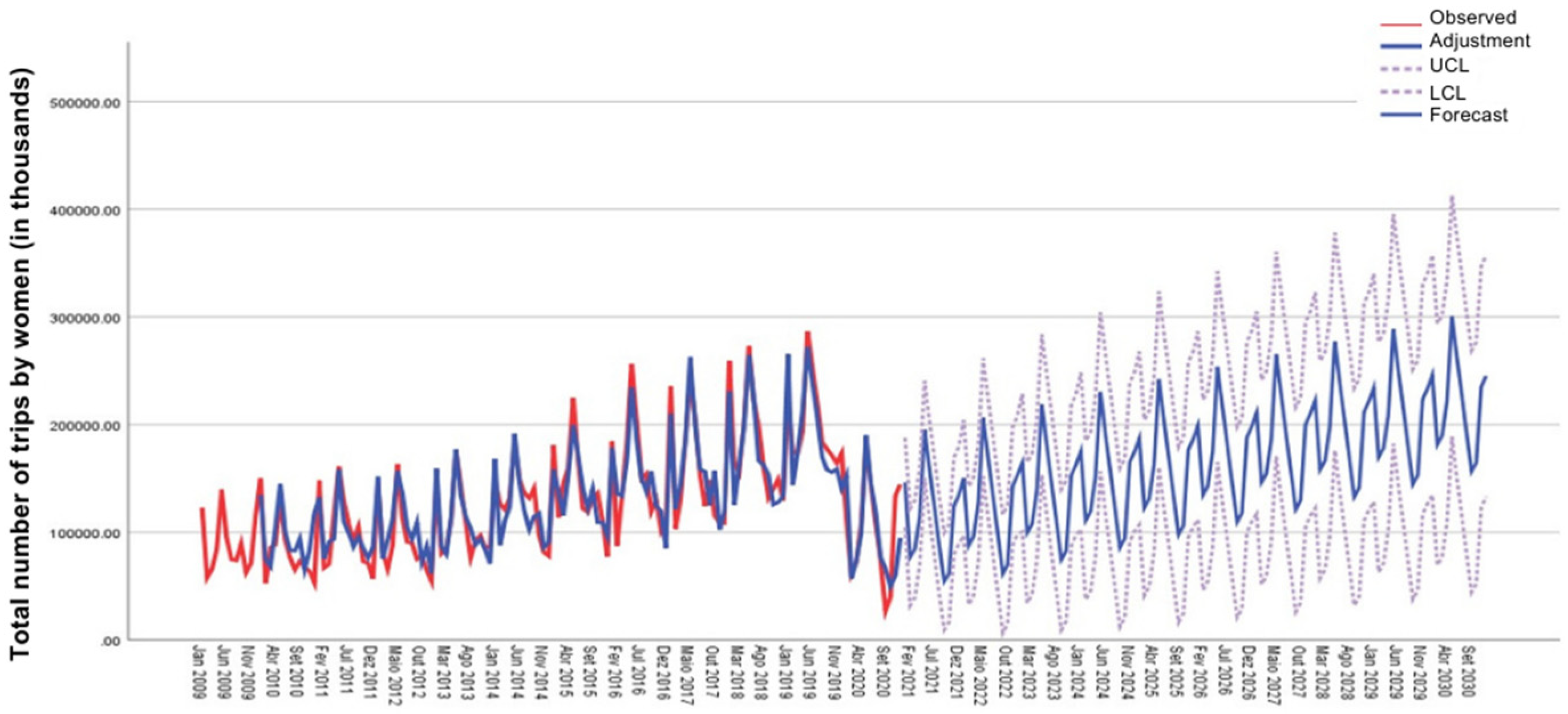

3.3. Estimation of Models for 10 Years (2030)

In the projection analysis until 2030, the ARIMA model was adopted to adjust different components of the three series under study: total, men, and women. For the random component, the ARIMA (0,1,1) model was applied to the three series, while seasonal particularities were adjusted according to different models for each series—ARIMA (1,1,0) for the total and women, and ARIMA (0,1,1) for men. The resulting parameters were statistically significant, with

p-values lower than 0.01 and 0.05 [see

Table 4 and

Table 5].

As for the trend component, it was uniformly adjusted using an MA(1) model in all series. Specifically, the parameters obtained indicated significance at the 1% level, corroborating the robustness of the adjustment. The seasonal component was also consistent in the three series, with first-degree differentiation, and additional adjustments of AR(1) for the total and women and AM(1) for men.

During this ten-year projection, an anomaly shared by the three series was identified in January 2020, which was incorporated into the models using an additive method. Evaluating the explanatory power of the models, the R

2 values were around 66% for men and 72% for the total and women. The Ljung–Box test validated the non-randomness of the series over time, with

p-values greater than 0.05 [see

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10].

Additionally, the effectiveness of the adjustment was evaluated using indicators such as mean squared error and mean absolute error. In these terms, the series for men and women presented better adjustments compared to the total series. Finally, graphical inspection of the standardized residuals and Autocorrelation Function Analysis (ACF) confirmed the absence of systematic patterns, suggesting that the residuals behave like white noise.

The compilation of these analyses, detailed in the attached table, solidifies the robustness of the estimated models and their usefulness for future projections.

4. Discussion

The previous absence of a discussion section represented a notable gap, which this new section aims to address by interpreting the results in light of the existing literature and exploring their implications. Our study demonstrates a robust growth trend in senior tourism in Portugal and identifies significant correlations between travel frequency and certain demographic and travel behaviour variables. Although our data do not directly measure quality of life outcomes, these results align with prior research indicating tourism’s potential role in promoting active aging and quality of life. The strong positive association between senior travel and short-to-medium-duration stays (1 to 7 nights) suggests a preference for accessible and frequent tourism experiences, which can be crucial for breaking routines and combating loneliness.

One of the most relevant findings is the positive correlation between travel and single-person senior households. This suggests that tourism may serve as a vital mechanism for socialization and building support networks for a demographic group particularly vulnerable to social isolation. This social function of tourism aligns with the principles of Active Ageing promoted by the WHO [

1,

18], which emphasize participation and security as pillars of quality of life.

Perhaps the most prominent finding, confirming H2, is that women aged 65 and over travel significantly more than men. While this gender gap is a known phenomenon in tourism literature (e.g., [

40,

45]), its magnitude warrants a deeper reflection that intersects with gerontological research. The literature offers several explanations for this disparity. First, sociocultural roles and caregiving patterns often position women as the “kin-keepers” who maintain family ties, a role that extends to organizing intergenerational travel, as noted by Yi et al. [

38]. Second, women frequently cultivate stronger and wider social networks in later life, which not only facilitates group travel but also acts as a crucial buffer against the social isolation this study links to travel motivation [

10,

41]. Finally, while women on average may have lower pensions, their greater longevity and different patterns of discretionary spending on social and experiential activities could also contribute to this trend. This finding underscores the need for tourism products that are specifically tailored to the motivations and social contexts of older women.

Finally, our ARIMA projections, which forecast exponential growth in senior tourism up to 2030 (confirming H3), must be interpreted through the lens of active aging policies. The temporary but severe disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the vulnerability of this demographic to social isolation. The projected strong recovery can thus be seen not just as an economic rebound but also as a resurgence of a critical tool for promoting quality of life. This upward trend aligns with the policy goals embedded in frameworks like the Active Ageing Index [

18,

46,

47], which emphasize participation in society as a key determinant of quality of life. The growth in tourism, therefore, represents a tangible and measurable increase in this participation. This makes the sector’s sustainable and accessible development a strategic priority, not merely for economic reasons, but as a central component of national health and social policy within the framework of the UN’s Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030).

It is important to clarify that although our empirical analysis demonstrates a robust increase in travel frequency among seniors, this study does not measure quality of life directly. The connection between increased tourism and improved quality of life is therefore inferred from the literature, which consistently identifies tourism participation as a driver of physical health, mental stimulation, and social engagement—all crucial components of active aging and quality of life. Nevertheless, the significant correlations we identified—particularly between travel frequency and single-person households, as well as the higher participation of women—suggest behavioural patterns associated with active and socially connected lifestyles, which are recognized indicators of enhanced quality of life in the literature (e.g., [

4,

5,

34]). Moreover, although our Introduction discusses the social, economic, and health-related factors linked to active aging, these variables were not directly measured or statistically tested in our empirical analysis and thus remain contextual background rather than analytical results.

We confirm that our empirical results do not test or quantify any statistical relationship between travel frequency and quality of life indicators, as such variables are absent from the INE dataset we used. Therefore, any statements linking tourism and quality of life in this paper should be understood as theoretical and associative rather than as causal conclusions derived from our data.

It is important, however, to acknowledge the limitations of this study, which in turn open avenues for future research. First, our reliance on secondary data from INE, while providing robust quantitative trends, prevented us from exploring the subjective motivations, perceptions, and barriers that shape senior travel decisions. Second, the absence of a qualitative dimension means the “why” behind the numbers remains largely inferential. Future studies should therefore employ mixed-methods approaches to complement large-scale data with rich qualitative insights. Furthermore, longitudinal panel studies that track the same cohort of seniors over time would be invaluable for understanding how travel behaviour evolves with health changes and life events. Finally, we recommend cross-national comparative research to test whether the patterns observed in Portugal hold true in countries with different welfare models and cultural contexts, thus distinguishing universal trends from context-specific ones.

5. Conclusions

This study embarked on a dual mission: to clarify the transformative role of senior tourism in promoting active and healthy aging, and to forecast the evolution of this sector in Portugal. Our quantitative analysis, based on longitudinal data, highlights a significant increase in senior tourism, a phenomenon widely recognized in the literature as potentially contributing, but not empirically confirmed in this study, to the quality of life and active aging of older people through enhanced physical, psychological, and social engagement. Projections for 2025 and 2030 indicate exponential growth, highlighting remarkable and increasing female participation, a phenomenon that demands continued attention from policymakers and tourism operators.

The significance of this study lies in its ability to move the research field beyond theoretical discussion by offering quantifiable and forward-looking evidence. By employing time-series analysis to project trends, the work makes a dual academic contribution: for gerontological research, it quantifies tourism as a measurable intervention for active aging; for tourism and economic studies, it provides robust predictive models for a high-growth market segment. In this context, the analysis of the Portuguese case provides a replicable methodological framework and reveals socioeconomic patterns—such as the link between travel and single-person households—that are highly relevant for other rapidly aging societies, particularly in Southern Europe (e.g., Spain and Italy) and East Asia (e.g., Japan), thereby distinguishing context-specific findings from potentially universal mechanisms.

However, translating this potential into reality requires concerted action from tourism stakeholders. For public entities and destination management organizations (DMOs), our findings highlight the need to integrate senior tourism into public health and social inclusion policies. This could involve creating subsidized off-season travel programs specifically targeting vulnerable groups, such as the single-person households that our study identified as having a high propensity to travel. For tourism operators, the practical implications are twofold. First, there is a clear market opportunity in developing travel packages that address the motivations of the dominant female segment, focusing on social connection, safety, and culturally rich experiences. Second, ensuring functional accessibility—from clear signage and transport to barrier-free accommodations—is no longer a niche consideration but a core business strategy for capturing this growing market. Future research should further explore these operational aspects, possibly through qualitative studies on the specific needs of diverse senior sub-segments. In summary, this study not only validates senior tourism as a pillar for a better-aging society but also provides a data-driven roadmap for policymakers and industry professionals to foster its inclusive and sustainable growth.