2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Assumptions

The research was based on the concept of the urban riverscape, which is defined as an urban landscape shaped by the relationship between humans and rivers. This concept encompasses both material and cultural dimensions. The river was considered not only as an environmental feature but also as a factor contributing to the construction of images and perceptions of the city in terms of both identity and symbolism. Taking into account the review of previous research, the following assumptions were made:

The river, as a physical and landscape feature, shapes the spatial structure of the city and the conditions for its development.

The river is a symbol and an element of perception that is present in iconography and cultural narratives, reflecting social values and ideas.

The river is a component of the city’s image and builds its recognizability, identity and attractiveness in visual and marketing communications.

The river is also incorporated into urban policy and revitalization projects as a component of sustainable development strategies, becoming a vehicle for the ideas of ecology, balance, and harmony with nature.

Based on these assumptions, a theoretical research model was constructed (

Figure 1).

In this model, the river serves as the starting point for the interpretation and construction of images. The way society perceives the river reflects its interpretation of its significance. These interpretations shape the city’s image, which becomes a tool for communicating its identity. Sustainable development strategies then transform these meanings into practical actions, such as revitalization, spatial planning and city branding. The model is cyclical: the strategy influences perception and image, which then redefine the river’s symbolic and functional meaning. This creates a feedback loop: the strategies implemented influence the further shaping of the image, perception and relationship between the city and the river.

Adopting this research perspective enables us to analyze the river as both a component of urban space and a tool for symbolic communication as well as an element of the city’s identity construction.

2.2. Research Objectives

This article presents research on the changing significance of the river and its impact on the city’s image, using the relationship between the Oder River and Szczecin as an example. It is based on an iconographic analysis of postcards depicting the riverside area of the city, covering a period of approximately 170 years—from 1850 to 2024. The research focused on understanding how the river reflected and co-created the city’s identity at various stages of development as an element of the landscape and structure of the city.

The main objective was to examine the impact of the Oder River on the image of Szczecin in the context of sustainable development. This objective was developed through the following specific objectives:

to indicate the importance of the river in particular historical stages of the city’s development and changes taking place in this respect in the analyzed historical periods,

to identify objects and their functions that are important for highlighting the specific significance of the river in a given historical period,

to indicate the relationship between the image of the city being built and the significance of the river in the city’s landscape (the evolution of the river’s significance and changes in the image of the city),

verifying whether the river has a significant meaning in the current image of the city, which aspects of meaning are most promoted, and whether they fit in with the ideas of sustainable development and the brand of the city of Szczecin—Floating Garden, promoted since 2008.

2.3. Methods and Tools

The research methodology combines the historical and interpretative approach typical of architecture and urban planning research with semantic analysis tools and network theory. This allowed for a detailed interpretation of the relationship between the river and the city.

The research conducted using desk research included a query of source materials—iconography, consisting of the interpretation of historical and contemporary graphic representations of the riverside part of Szczecin, together with characteristic architectural objects located in this area of the city. The use of iconography as a research tool has a long tradition. The analysis of the images allows us to trace the evolution of the cultural features of the landscape [

64], its variability over time, and to identify those compositional elements that were deliberately or intuitively exposed.

The analysis covered several digital databases containing archival and contemporary postcards showing riverside parts of the city, such as Fotopolska (a documentary and historical portal with 1353 archival and contemporary postcards in its collection), the National Museum in Szczecin (a virtual museum containing high-quality archival materials with a collection of 36 postcards), Facebook, i.e., the “Szczecin na zdjęciach” (Szczecin in photographs) page (a social networking portal bringing together photography enthusiasts and residents who share both contemporary shots of the city and scans of private archives, in which 1458 postcards were found), Instagram (a social networking site with 187 postcards found on pages such as Pomorze Zachodnie and Visit Szczecin, which are promotional and tourist-oriented, showing the city from the last few years).

A total of 3034 postcards were reviewed, of which 3016 were selected for further analysis, as they met the criteria: temporal (postcards from the period 1850 to 2024 were analyzed) and substantive (only postcards presenting the riverside part of Szczecin with specific objects performing specific functions in the city were taken into account). The objects shown on the postcards were assigned to one of five groups based on the time of the postcard’s creation, usually covering a period of about 25 years:

1850–1919 (Szczecin as a fortress and post-fortress),

1920–1945 (prewar and wartime Szczecin),

1946–1975 (postwar Szczecin—socialist),

1976–2000 (Szczecin in transition—political changes),

2001–2024 (contemporary Szczecin).

The earliest period is an exception, covering a longer period of about 70 years due to the smaller dataset (there are significantly fewer postcards from the 19th century).

2.4. Research Process

The research process comprised several stages that were logically connected, combining historical and interpretative analysis with quantitative and visual methods.

Stage I: Searching for and selecting source material—Postcards depicting the city’s riverside areas were collected and preliminarily selected in accordance with the adopted temporal, spatial and substantive criteria.

Stage II: Classification and coding of iconographic material—Postcards were coded according to three analytical dimensions:

Objects: the main physical or architectural elements visible on the postcards, such as bridges, waterfronts, castles and port areas.

Meaning of the river: the functional or interpretative roles attributed to the river (e.g., industrial, esthetic, architectural, urban and recreational).

Semantic aspects: broader cultural and symbolic contexts.

Stage III: creating a database and developing a category structure—The coded material was entered into an analytical spreadsheet in Excel, with each postcard constituting a single record. A standardized naming scheme was employed, and identification codes were assigned to facilitate further data processing.

Stage IV: quantitative analysis of the postcard collection—A statistical analysis was conducted to ascertain the number of postcards assigned to specific meanings of the river and semantic aspects within distinct historical periods. This revealed the dominant functions and meanings of the river at different stages of the city’s development, showing how they evolved from industrial and transport-related meanings to esthetic, recreational and symbolic ones.

Stage V: Construction and analysis of semantic co-occurrence networks—Based on the co-occurrence of categories, a semantic co-occurrence network was created that connected three types of nodes: Objects; Meanings of the river; and Semantic aspects. This enabled relationships to be identified between the material, functional, and symbolic dimensions of representations.

This methodological model, which has been developed, can be used in the study of other riverside cities that are facing challenges related to sustainable development.

2.5. Territorial Scope

The territorial scope of the research was limited to Szczecin (Stettin in German and Sedinum or Stetinum in Latin) and its riverside area. Szczecin is located in northwestern Poland, in the western part of the West Pomeranian Province, on the Polish-German border (

Figure 2). The city lies on the Oder River and Lake Dąbie; it is about 100 km from the sea. Within the city limits, the Oder is divided into two branches: the Western Oder, which reaches a width of 140–200 m at its widest point, and the Eastern Oder from Widuchowa (Regalica), which is approximately 160 m wide. The area of wetlands, canals, and islands between the two branches of the Oder is called Międzyodrze. At the end of its course, the Oder flows into a coastal basin formed by a large water complex: Roztoka Odrzańska and Zalew Szczeciński [

65].

2.6. Subject of the Study

The subject of the study is the relationship between Szczecin and the Oder River and the importance of the river in shaping the image of the city. Historically, Szczecin was the capital of the Duchy of Pomerania, but at various times it was also within the borders of Sweden, Brandenburg, Prussia, and Germany. The city was founded in the early Middle Ages as a riverside settlement with a stronghold and a suburb at the intersection of the east–west land route and the north–south water route [

66]. At that time, the Oder River flowing at its foot was what nourished and gave a sense of security [

67]. The river was a communication and trade axis but also a factor determining the direction of the city’s urban, economic, and cultural development. This can be seen in many iconographic representations from different periods of the city’s historical development [

68,

69]. The granting of Magdeburg rights in 1243 and early accession to the Hanseatic League determined the rapid development of the city. Szczecin became an important center of maritime trade and the Oder was the main transport route for goods flowing from the interior of the continent to the Baltic Sea [

65,

69]. The numerous ships at the quay and the intense traffic on the river, visible in iconographic representations from that period, testify to the great importance of the port (

Figure 3).

During the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), Szczecin was occupied by imperial troops in 1627 and, in 1630, the city was taken over by the Swedes. Their rule, combined with the construction of the Szczecin fortress, closed off the possibility of the city’s spatial development and significantly limited its area. In 1713, the city was taken over by Prussia. New fortifications were built, transforming Szczecin into a Prussian fortress with three forts [

64]. At that time, the river was a defensive barrier and a natural boundary for settlement. The development of the port was limited to the banks of the Oder between the Długi and Kłodny bridges, which marked the basic boundaries of the city port. The banks of the Parnica were connected by one bridge and three piers (

Figure 4).

The mid-19th century marked the beginning of a particularly important period in the city’s development, associated with intensive industrial growth and the expansion of the city and the port. This was stimulated by the launch of a railway connection to Berlin in 1843 and the demolition of the fortifications and the liquidation of the fortress in 1873. This triggered the urbanization of the post-fortress areas around the Old Town and a series of investments aimed at raising the status of the city and the port [

66]. Szczecin acquired basic technical infrastructure: a gas network (1848), water supply and sewage systems (1864), and an electricity network (1886). The first tram lines were established in 1879 and electrified in 1897. In 1898, a power plant was built [

65,

69]. Industrial development stimulated the activity of the port of Szczecin. The liquidation of the fortress enabled access to areas that could be used as port areas in Międzyodrze and the construction of new canals, cuts, and basins, as well as the construction of a port railway station (Wrocław Station). During the reign of mayors Haken and Ackerman, the port underwent dynamic development. In 1880, the Piastowski Canal was put into use, shortening the waterway from Szczecin to Świnoujście.

In 1898, a free port was opened—the so-called eastern basin—and, in 1910, the western basin. The new port basins on the Parnica (Parnitz) and Regalica (Regalitz) rivers and the islands of Górno and Dolnokrętowa, where shipyards were located, led to the development of transshipment infrastructure, which transformed Szczecin into a modern industrial center. In 1913, the amount of transshipped goods exceeded the combined turnover of the ports in Königsberg, Gdańsk, and Lübeck. Thanks to the development of Szczecin’s shipbuilding industry, the “Vulkan” and “Oderwerke” shipyards became competitive with Hamburg and Gdańsk (BPPM). Thus, Szczecin became one of the leading Baltic ports [

69]. In turn, the construction of bridges, bathing areas (Baden-Antst.), yacht marinas, including those on the islands of Tripitz Intel and Bradower Werde or Wassersport Vereine on Schlachter Wiese, and the development of shipping as a form of public transport increased the accessibility of the river for residents and opened the city toward the water, which was an integral part of it at that time [

70,

71] (

Figure 5).

The new urban layout associated with the administrative expansion of the city, the downtown complex, quarters of eclectic tenement houses, and a number of investments on the waterfront gave the city a metropolitan character. Among them, the complex built between 1902 and 1921 deserves special mention—Haken’s Terraces (now Wały Chrobrego), a representative boulevard on the Oder River with monumental buildings (today, these are, starting from the south, the Maritime University, the National Museum building with the Contemporary Theater, and the Provincial Office), pavilions, and a large basin with a fountain at the foot.

During World War II, Szczecin served as a military base and was bombed by the Allies. The greatest damage was caused by carpet bombing in 1943–1944, which destroyed and damaged 45% of the city. The greatest damage was in the industrial districts along the Oder River and in the Old Town. The entire port and shipyard infrastructure, as well as important industrial plants, were destroyed. The air raids damaged monumental buildings such as the castle, the town hall, and the churches of St. James and St. John, which were rebuilt, as well as those that were not rebuilt, such as the granaries in Łasztownia and the Kłodny and Dworcowy bridges [

65].

After World War II, when Szczecin was incorporated into Poland, the city’s development continued, often in a way that violated the old spatial relationships and historical urban layout. The first postwar urban plan for the city was drawn up in 1947 and envisaged the creation of a north–south transport route along the Oder River and the removal of dense urban development from the city’s historic port waterfront. The second “general and detailed” plan, covering the entire area of “Greater Szczecin,” was drawn up in 1948. The main idea behind the city’s development was to create a new transport axis for the river-city complex—the Nadodrzańska Artery—and to connect both banks of the Oder and the Międzyodrze [

69]. Unfortunately, the development of the expressway contributed to the city turning away from the river and limiting the accessibility of its riverside area (

Figure 6).

In the postwar period, Szczecin became famous primarily as a shipbuilding city and a leader of the workers’ movements that accelerated the radical political breakthrough in 1989 and the change in the state system from socialist to democratic.

Contemporary Szczecin not only lies on the Oder River—the river is its functional backbone and an important element visible in the city’s development strategy [

65]. The seaport of Szczecin, connected to the port complex in Świnoujście, is one of the largest in Poland and an important element of the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) [

72]. The Oder is an important artery for inland shipping, both for cargo and recreation. Bearing in mind the potential of this resource, a process of reurbanization of riverside areas such as Międzyodrze has been initiated through various investments, including the revitalization of Stara Rzeźnia, the construction of the Lastadia office building, a marina, and the construction of the Maritime Science Center. The process of transforming the islands of Łasztownia and Kępa Parnicka into new downtown structures and adapting areas vacated from port functions is underway. The Odra boulevards, which have undergone modernization in recent years, have become a high-quality public space, serving recreational, tourist, and cultural functions. Thanks to them, residents have regained access to the water and the city has regained part of its identity as a “city on the river.”

3. Results

3.1. Significance of the River Based on the Analysis of Postcards (1850–2024)

An analysis of over three thousand postcards from 1850 to 2024 depicting the riverside part of Szczecin made it possible to identify the most important aspects of the river’s significance for Szczecin and the most popular architectural objects representing the specific significance of the river.

The river influenced the urban development of Szczecin, and an analysis of historical postcards shows the transformation of the river’s significance as the city evolved. Over the years, the Oder has served various functions, from city-forming to industrial to representative, focusing on the surrounding architecture. The river’s various functions were associated with the establishment of a specific meaning of the river and aspects of meaning that were represented by specific objects and the river’s relationship with the city landscape. Ten meanings of the Oder have been identified: historical and city-forming, esthetic, symbolic, architectural and urban, ecological, socio-cultural, recreational and leisure, industrial, transport, and revitalization. The perception of each of the identified meanings is based on the objects displayed on postcards and the visible relationship between the river and the city, which plays a specific role in the landscape of Szczecin (

Table 1).

An analysis of the collected materials, which initially did not divide them into specific periods, indicates that three aspects dominate the iconographic collection. These are architecture, the location of industrial facilities, and landscape features and landmarks (

Figure 7).

The architectural and urban significance appears a total of 671 times in all the material studied, making it one of the most important ways of perceiving the river in an urban context and accounting for 22% of all the iconography analyzed. Within this meaning of the river, three aspects were distinguished, which were used to evaluate the postcards: architecture, urban layout, and bridges as symbols. The most representative aspect in this category is architecture, which was assigned to 488 illustrations, most often featuring the Provincial Office (215) and the National Museum in Szczecin (200), suggesting their special role in the urban space. The buildings serve administrative and cultural functions, dominating the waterfront panorama. Their frequent presence on postcards indicates that they are among the most recognizable and characteristic elements of the city’s panorama, which emphasizes the role of the river as a representative space.

The second most frequently assigned meaning in the analyzed material is industrial significance, which occurred a total of 516 times, accounting for 17% of the entire collection. This testifies to the strong connection between the Oder River and industrial activity. In terms of this meaning, the most frequently identified aspect was the location of industrial facilities. More than half of all postcards analyzed in this semantic group featured the Szczecin Shipyard, which appeared 272 times. Another dominant object was the “Ewa” Elevator, present on 110 postcards. The industrial space visible in the iconography is often disharmonious, contrasting with the landscape composition and urban development. Industrial facilities stand out with their austere form and large scale, thus disrupting spatial coherence and preventing visual connections. These objects dominate the other elements of the landscape and limit the accessibility of riverside spaces, while at the same time constituting a strong distinguishing feature of the landscape.

The third most common category of river meaning is esthetic significance, which was assigned to 504 postcards, accounting for 17% of all the photographs analyzed. A key aspect of the analysis was the motif of the dominant feature and landmark, assigned to 500 postcards. The most frequently depicted space in this category was the Old Town, visible on 80 postcards. The photographs featured characteristic buildings, such as the Provincial Office and the National Museum, which are important elements of the urban composition. Thanks to their scale, architectural detail, and location in relation to the river, these objects serve as spatial landmarks. The frames present the river as a visual and spatial axis around which architectural objects have been deliberately located. The river actively participates in the composition, not only serving as a backdrop but also emphasizing the esthetic qualities of the buildings and spatial arrangements.

The significance of the river has evolved over time, influenced by changing socio-economic and political conditions. The periods analyzed were associated with different functions assigned to the riverside space and different perceptions of the river as an element of the urban structure. At different stages of the city’s development, the river took on different roles, adapting to the needs of the community, going from a period of industrial significance to that of a public space with esthetic and recreational values. The changeability of its functions is visible in the iconography analyzed, where the river takes on the role of a carrier of specific meanings. The importance of rivers in relation to sustainable development is not significant in the entire collection of postcards, despite activities such as the integration of water and greenery in urban planning, the revitalization of riverbanks, the accessibility of public spaces and the promotion of ecological ideas reflecting this importance. However, analyzing individual time periods reveals the growing importance of these categories and the development of functions related to sustainable development.

3.2. Importance of the River in the Analyzed Time Periods

3.2.1. Szczecin as a Fortress and a Post-Fortress City (1850–1919)

In the first of the analyzed periods (1850–1919), Szczecin belonged to Prussia and functioned as a fortress until 1873. A total of 345 postcards depicting the riverside area of the city were assigned to the period of Szczecin as a fortress and post-fortress city. The most frequently assigned meaning was historical and city-forming, which was assigned to 127 postcards, constituting 37% of the collection from this period. A distinctive aspect of meaning in this category was transport and trade. The second most common meaning of the river was transport, which was assigned to 67 photographs, constituting 19% of the collection. Two aspects stood out in this category of meanings: the natural transport route present on 52 postcards and industrial ports appearing in 15 shots. The river plays a key role in the development of trade and communication, influencing the shape of the city and its urban structure. In the analyzed collection of postcards, there were no illustrations with ecological or socio-cultural significance, or related to the revitalization or modernization of riverside areas. The smallest number of postcards were assigned industrial significance, with only six images depicting the river in the context of the location of industrial facilities and the creation of infrastructure. During this period, it is hard to establish a clear link between the importance of the river and the implementation of sustainable development ideas (

Figure 8).

3.2.2. Szczecin Before and During the War (1920–1945)

In the second period analyzed (1920–1945), Szczecin was still within the borders of Germany. For the prewar and wartime Szczecin period, 338 postcards were analyzed, accounting for 11% of all images. Among them, the most frequently represented meaning was historical and city-forming, with an aspect of transport and trade, attributed to 85 photographs, which corresponds to 25% of the collected material from this period. The second most dominant theme was architecture and urban planning, which was noted in 82 images or 24% of the total for this period. The most frequently visible aspect was architecture (40 photographs), followed by bridges as symbols (24 photographs) and urban layout (18 photographs). The river was also perceived in the context of its recreational, esthetic, transport, and industrial significance. Social and cultural significance appeared in four illustrations, depicting the river as a place of meeting and integration, as well as cultural heritage. The representations of the river were more focused on highlighting its functional and representative roles. However, postcards from this period were not assigned any ecological or revitalization significance. This shows that the river was not yet perceived in these categories (

Figure 9).

3.2.3. Szczecin Under Socialism (1946–1975)

In the third period analyzed (1946–1975), Szczecin found itself within the borders of Poland under a socialist system and faced the need to rebuild the city and the country from the destruction of war. The socialist Szczecin period included 220 photographs, accounting for 7% of all the illustrations analyzed. The most frequently attributed meaning was industrial, present in 48 postcards, or 22% of the collection from this period. In most cases, as in 46 shots, the river was shown as a backdrop for industrial facilities and, in two cases, in the context of infrastructure development. The next two important meanings in this period were esthetic and architectural and urbanistic. The dominant feature of the landscape and the landmark were clearly visible aspects—the way the river was shown allowed for the presence of key objects to be highlighted in 35 photographs. Architectural and urban significance was noted in 34 postcards. The predominant aspect in this category was architecture. Twenty-one photographs showed important public and administrative buildings. Less frequently presented were the urban layout of the city, which appeared in eight shots, and bridges as symbols, which appeared in five photographs. No postcards with ecological significance were found in the entire analyzed collection from this period. The least frequently attributed significance was revitalization, which was assigned to three photographs. There is a noticeable trend towards increasing the accessibility of rivers by reviving their recreational and transport functions. While this is a step in the right direction, the direct link to sustainable development remains unclear (

Figure 10).

3.2.4. Szczecin During the Political Transformation (1976–2000)

The fourth period analyzed (1976–2000) is associated with dynamic socio-economic changes and political transformation. For the period of political change in Szczecin, 72 postcards were analyzed, which constitutes 2% of the entire collection of iconographic material. Most of the images from this time period were related to transport, appearing in a total of 18 photographs, which constitutes 25% of the collection from this period. Two aspects of significance were distinguished in this category: the natural transport route visible in 10 images and the industrial port in 8. Other important aspects of the river’s significance for this period were its industrial and esthetic importance—17 photographs were assigned to both, which accounts for 24% of the analyzed collection. In the case of industrial significance, the most common aspect was the location of industrial facilities. The images emphasize the importance and role of the Oder as a communication and industrial channel. In terms of esthetic significance, the river appeared in the context of a dominant feature and landmark, influencing the way characteristic architectural objects and the entire riverside space were perceived and shaping their reception. The symbolic and recreational significance appeared least frequently in the analyzed material. On the other hand, the historical-city-forming, ecological, and revitalization significance was not attributed to any postcard from this period. This period could be an opportunity to consciously incorporate the idea of sustainable development into the management of riverine areas. In reality, however, this remains largely invisible. Due to dynamic political changes and challenging socio-economic conditions, the river’s role at this time is primarily economic, serving the reconstruction and development of industry (

Figure 11).

3.2.5. Modern Szczecin (2001–2024)

In the period 2001–2024, Szczecin is developing intensively, drawing on its waterfront and cross-border location. The period of contemporary Szczecin, adopted for the years 2001–2024, covers the largest part of the studied collection, with as many as 2004 photographs, which accounts for 66% of the entire collection. The most frequently attributed meaning in this group is architectural and urban, which appears in a total of 509 photographs, accounting for 25% of the period in question. The architectural aspect appears in 401 shots, the urban layout in 55 photographs, and bridges as symbols in 53. The river provides the backdrop for characteristic objects and elements that organize space and composition. The second most common meaning is industrial, usually shown in the context of the location of industrial facilities, visible in 411 photographs or 21% of the group. The third most common meaning is esthetic, visible in 383 photographs. The river is most often depicted in the context of a dominant part of the landscape and a landmark. This indicates a strong connection between the river and the perception of riverside areas. The least frequent were shots with ecological and transport significance, which appeared in only five photographs in both groups. In this time category, no historical and city-forming significance was noted, which indicates a change in the narrative and perception of the river’s function in the city. During this period, there was a significant change in terms of conscious reference to the idea of sustainable development, as evidenced by the increased importance placed on river revitalization, ecology and recreation. This demonstrates the process of making the river and waterfront accessible, as well as showing respect for the natural environment and cultural heritage (

Figure 12).

3.3. The Leading and Accompanying Significance of the Oder River

An analysis of the river’s significance indicates that, in each of the studied periods, the river’s primary significance can be identified, alongside two or three secondary significances. In the case of the Oder, its primary significance has changed over the years. At the same time, some of the river’s significance remained important throughout the entire study period, while the impact of others was significant only during a specific period. The river’s architectural and urban significance remains strong throughout all periods, with the river gaining leading status in recent years. Meanwhile, its city-forming significance was only important during the first two periods. The Oder River’s industrial and transport significance should be recognized as it played a leading role during the post-war period and political transformation, and was one of the most important factors in other periods. The prewar and wartime periods deserve special attention as the river’s function was greatly diversified during this time. Its industrial and transport significance was accompanied by social functions, and it experienced a marked revival. The ecological and revitalization significance of the river only emerges in the final analyzed period, but it is not particularly significant. Although a leading role is not played by them, the process of implementing the idea of sustainable development through respect for cultural and natural heritage is demonstrated by them (

Figure 13).

3.4. Semantic Network Analysis

Semantic network analysis revealed that the most central categories are those associated with the river’s functional and representational meanings—particularly Industrial, Architectural and Urban, and Transport. These categories confirm the Odra River’s strong historical and infrastructural role in shaping the city’s spatial and economic structure. High betweenness centrality values indicate that these categories connect physical elements, such as quays, bridges and ports, with broader symbolic and esthetic interpretations. Meanwhile, categories such as Recreation and Leisure and Esthetics are occupying an increasingly important position within the network. Although they are slightly less central, their growing relational density suggests a semantic shift—a transition from utilitarian and industrial interpretations towards meanings associated with public use, landscape experience and visual attractiveness.

The analysis identified Promenades, Boulevards, Water sports and Tourism as the most significant semantic aspects. These nodes demonstrate a high level of betweenness centrality, indicating that they serve as connectors between various categories of meaning. They play a crucial role in integrating the social, esthetic and recreational functions of the river into the urban landscape. The semantic aspect ‘Bridge as a Symbol’ demonstrates high closeness centrality, indicating that it is closely linked to multiple other elements. As well as serving a transport function, bridges also act as iconic landmarks, contributing to the city’s identity and collective image.

Of the physical objects, the Chrobry Embankment, the Piast Boulevard and the Long Bridge exhibit the highest degree of centrality. This indicates that these locations act as integrative nodes, combining the various meanings of the Odra River—from transport and recreation to symbolic and representational dimensions (see

Figure 14).

3.5. Evolution of the City’s Image

The analysis of the significance of the Oder River in the city landscape over the years has allowed us to identify the leading periods of the river’s significance in individual studies, to indicate characteristic views and prominent objects, and to determine the perception of the river and the image of the city shaped on this basis (

Table 2).

During the period when Szczecin was a fortified city and after the fortifications were dismantled (1850–1945), significant changes took place in the functioning of the city and the river. The city, which had long remained a Prussian stronghold, decided in 1873 to demolish its defensive walls, thereby gaining space and new opportunities for development. Postcards characteristic of this period show the Oder and the riverside areas primarily through the prism of the connection with the world, which is essential for the functioning of the city, symbolically represented by bridges. The river is perceived on the one hand as a border and additional protection and, on the other hand, as a road to the city and a communication route. The river brings movement and life to the city. A city located on a river appears to be safer and more resilient—it is a refuge and a safe haven that can be reached in a controlled and orderly manner thanks to the river. The image of the city portrays Szczecin as strong, compact and safe. (

Figure 15a,b).

During the prewar and war periods (1920–1945), Szczecin underwent intensive spatial and economic development. Postcards characteristic of this period show the Oder and the riverside areas primarily in the context of the city, which underwent a significant change in image, becoming a metropolis and a city aspiring to be a sister city to Berlin, which modeled itself on its architectural achievements. The river’s significance grew and diversified during this period. The Oder became multifunctional and diverse. It seems that functional diversification, including lively social, leisure, and recreational functions, caused the river to be perceived subjectively as an important element of urban space and social life. On the other hand, the river provides an excellent backdrop for important buildings, offering panoramic views that showcase the prestige and power of the developing city of Szczecin. The Oder, thus, builds and highlights the image of the city as a modern, rapidly developing German metropolis (

Figure 16a–c).

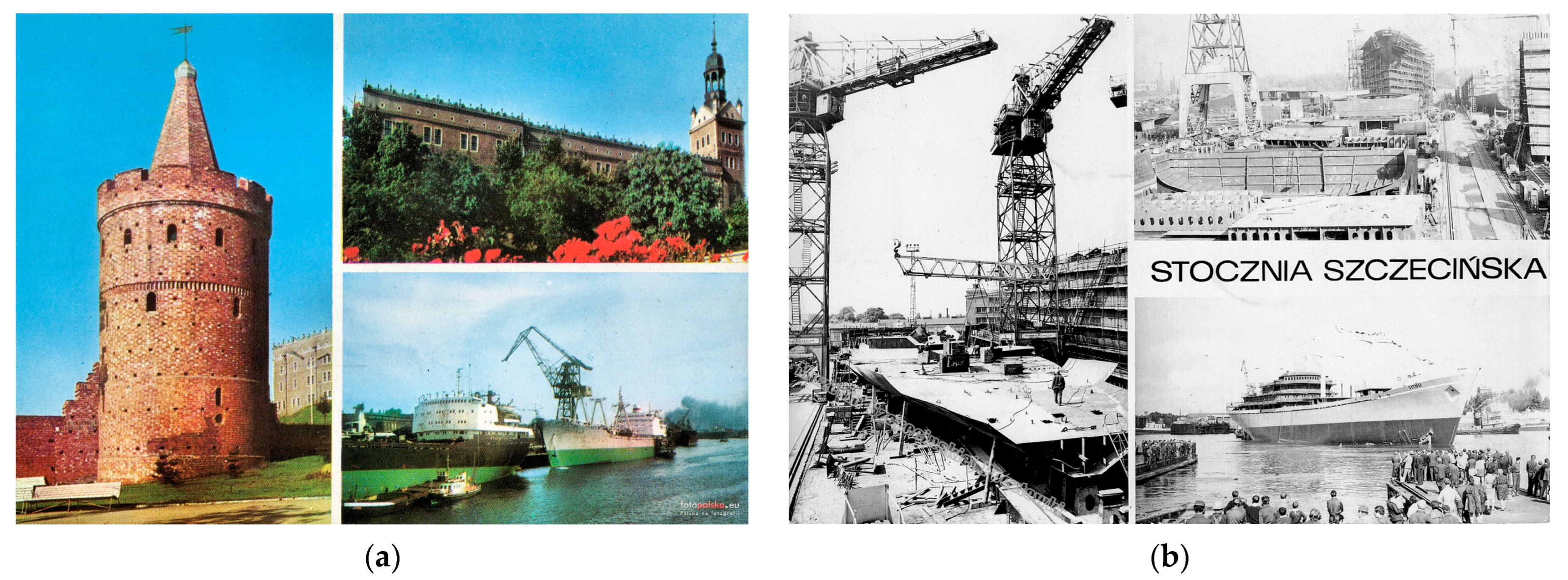

In the postwar socialist period (1946–1975), Szczecin was incorporated into Polish territory and struggled to rebuild from the postwar ruins in the new socialist political and economic reality. Postcards from this period highlight objects representing the Piast roots of the city and its intensive development, which is supposed to be proof of the superiority of the socialist system over capitalism. Szczecin is presented as a city that is once again Polish, whose present and future are to be based on the shipbuilding industry. The river, which at that time served primarily utilitarian functions, was seen as a lever for economic development, especially for the shipbuilding industry, and as a strong border of the Polish state, thus serving as an indirect tool of political propaganda. The Oder becomes an effective channel for shaping the image of Szczecin—a city that is once again Polish and a rapidly developing shipbuilding center (

Figure 17a,b).

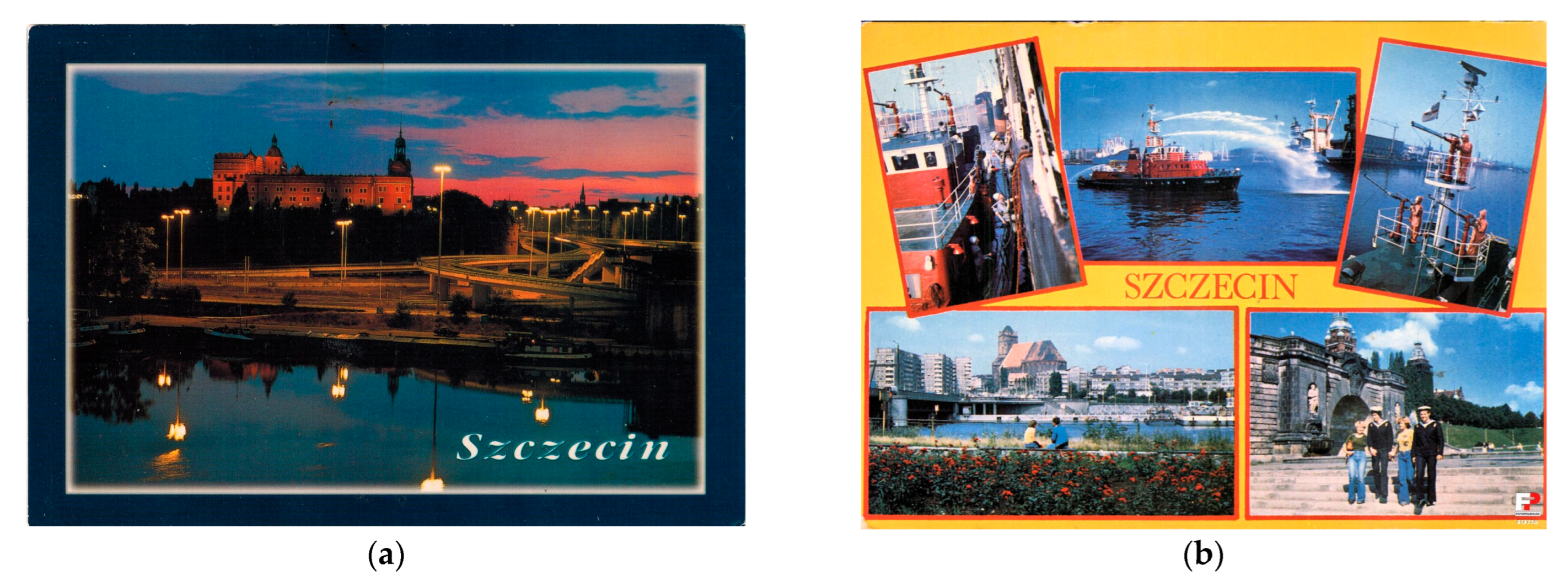

During the period of political change in Szczecin (1976–2000), the city struggled with dynamic socio-economic changes and political transformation. Postcards from this period show the pursuit of modernity and freedom, symbolized by newly built architectural and engineering structures, but also by the white fleet. The river is perceived as a symbol of the maritime and port character of the city, serving in this context as a means of highlighting the direction of the city’s development. The Oder River builds the image of Szczecin as a modern, developing port city (

Figure 18a,b).

In the period of contemporary Szczecin (2001–2024), significant changes took place in the approach to managing and shaping the city’s space. The city entered a period of conscious implementation of the idea of sustainable development and promotion of the idea of a green Szczecin. The river is beginning to be seen as an essential element of the city’s identity, which translates into further investments in the revitalization and improvement of the waterfront’s accessibility. Postcards characteristic of this period show the Oder River in combination with greenery, functioning as a place for recreation and sports. The river is perceived as a recreational space, friendly to people, allowing them to spend their free time close to nature. This has helped to build the image of Szczecin as a green and waterfront city, friendly to residents and tourists, and an important center for water sports. This image of the city aligns with the concept of a sustainable city, combining historical identity with respect for the natural environment. Water, nature and culture are key elements of this identity (

Figure 19a,b).

The evolution of the city’s image in the context of the perception of the river indicates that the city-river relationship remained a two-way relationship throughout the entire period analyzed. The river had a significant impact on shaping the image of the city, and the city determined the functional importance of the river and the way it was perceived.

3.6. Typology of City-River Relations

An analysis of the relationship between Szczecin and the Oder also allows us to see certain differences in the nature of the city-river relationship, which changed over time. Five basic types of city-river relationships of spatial and economic significance and four types of relationships of socio-cultural significance have been identified, which may be universally applicable and find reference in other riverside cities.

Types of city-river relationships of spatial significance.

A city in the vicinity of a river—a relationship based on the assumption of the city’s development in the vicinity of a river, which acts as a kind of border and defensive barrier. The river serves a protective function, and contact with it is limited. This applies to the early stages of the city’s development, when it was a fortress surrounded by defensive walls.

A city on a river—a relationship based on the development of a city opening up to the possibilities of using the river for transport and trade. In this context, the river becomes a kind of link to the world.

A city with a river—a relationship based on the active use of the river and its banks. In functional terms, the river becomes the center of the city, an important part of the urban space, and a key element of the city’s economy.

A city turned away from the river—a relationship based on the selective use of the river and a focus on its industrial function at the expense of limiting its accessibility to the public. An exploitative and utilitarian approach.

A city turned back towards the river—a relationship based on a change in approach and the reintegration of the river into the city space. The revitalization of the riverside areas becomes an integral part of the city’s strategy.

In the cultural context, four types of city-river relationships have been identified.

A city dependent on the river—a relationship based on the subordination of the city’s existence and functioning to the river, which is the life-giving force that determines the survival of the city and life in it.

A city coexisting with the river—a relationship based on the symbiosis of the city and the river, which performs various and numerous functions, including social ones, becoming an integral part of the space for residents and even a kind of center of life in the city.

A city exploiting the river—a relationship based on the subordination of the river to the city. The use of the river is exploitative and devoid of social character, which results in the river being excluded from the city’s public space.

A city in harmony with the river—a relationship based on the conscious introduction of balance in the city-river relationship. The use of the river becomes sustainable and functionally diverse, taking into account both economic and social needs as well as natural and ecological ones. This is a kind of ideal relationship associated with the revitalization of riverside areas carried out with respect for cultural and natural heritage.

The current direction of the development and promotion of Szczecin as a city friendly to residents and tourists, based on green and water resources and developing in a sustainable manner, is becoming increasingly visible in the promoted image of the city. In spatial terms, the green and waterfront city of Szczecin strives to adopt the model of a ‘City Reoriented Towards the River’, while in cultural terms, it aims to promote the concept of a ‘City in Harmony with the River’.

4. Discussion

The image of a place is the sum of beliefs, ideas, and impressions that people have about a given place, the result of direct experiences and memories of past experiences of its inhabitants [

19,

73]. We can find a reflection of a specific image of a city in representations made using various techniques and methods of space projection. Views of characteristic places, presented by artists in panoramas, postcards, and graphics, have preserved architecture and landscape for centuries, presenting and shaping a specific cultural image of space and the image of the city as a carrier of meaning. The objects and landscape elements exposed in these representations are not only a record of the history of the place but also the creation of a specific narrative [

4].

Art, iconography, and photography are of significant importance in assessing landscape changes on a historical time scale [

74]. Postcards seem to be particularly valuable for visualizing landscape changes in cities. Their systematic analysis allows researchers to visualize the evolution of the view, increasing their understanding of the changes taking place in the landscape [

75]. They can be important evidence showing the relationship between people and the city with the river at a given time through the shown ways of spatial development of urban riverside areas [

53].

Unfortunately, original photographs are often modified by publishers, which means that they may not represent the true view of the landscape [

76] and may even serve as a tool for political propaganda [

77]. However, if postcards are used in the context of research on the image of a city, the information encoded in them takes on special significance. It becomes possible to identify objects that are key to creating the image and brand of a city, as well as the city’s development strategy [

4].

The adopted historical-interpretative method based on the analysis of postcards showing the Oder River and the riverside part of Szczecin in the years 1850–2024 proved to be a sensitive tool for diagnosing the image of the city, the significance of the river, and its perception.

The research showed that the Oder, flowing through Szczecin, is not only the physical topographical axis of the city but also a deeply rooted element of its identity and an integral part of the promoted image of the city. From the city’s founding to the present day, the presence of the river has determined its spatial, economic, and cultural development. However, each of the historical periods analyzed was associated with a slightly different significance of the river for the city.

The results of both the quantitative and semantic network analyses are mutually consistent, indicating an evolution in the meanings attributed to the river—from strictly utilitarian, economic, and transport functions in the 19th and early 20th centuries toward contemporary symbolic, social, and ecological interpretations. During the early stages of the city’s development, meanings relating to industry, transport and urban architecture predominated, as evidenced by the high centrality of these categories within the network structure. At that time, the river served as a fundamental factor shaping the spatial and economic development of the city, while its presence in the landscape symbolized Szczecin’s economic and technological power. Over time, as the functions of the waterfront have transformed, the significance of the Recreation and Leisure and Esthetic categories has gradually increased. Their growing relational density within the semantic network indicates a paradigm shift in the perception of the river—from an infrastructural element to a social, open, human-oriented space. The Oder was perceived as a barrier and a border, a communication route and a kind of “window to the world,” a public space, a tool for rebuilding Polishness, a maritime symbol and, increasingly today, as an element of urban revitalization. Contemporary representations of Szczecin increasingly depict the Odra River as an integral part of public life, embodying natural, cultural and esthetic values. The river not only serves as a compositional axis but also as a unifying element connecting the city socially and ecologically. This reflects a broader trend observed in European post-industrial cities, where rivers are increasingly being reinterpreted as public, ecological and cultural assets rather than merely infrastructural corridors.

The leading significance of the Oder identified in particular periods corresponds to civilizational and cultural changes in the use of rivers throughout Europe [

3,

6,

10,

11]. However, research conducted for Szczecin shows that, apart from global cultural changes, the history and tradition of a given place strongly determine the relationship between the city and the river, making it a kind of code of the city’s identity. The history of Szczecin and its geopolitical conditions relating to its cross-border location and changing national affiliation have left a significant mark on the use and perception of the Oder and the image of the city. The Oder has transformed from a river on the edge of the maps of Poland and Germany into a space of dialog and culture, becoming a European river [

53]. The topography of Szczecin, based on a unique river system in which the Oder branches into the Eastern and Western Oder, creating numerous islands, has also influenced the spatial character of the city, as well as the way its inhabitants function, their attitudes, and their behaviors [

78].

The importance of the river is, therefore, a result not only of civilizational and cultural changes but also of unique historical and locational conditions. As a border and navigable river, the Oder functioned in the city not only as an environmental element but also as a cultural code that co-creates local identity. Today, the Oder activates and integrates, as well as secures the livelihood and ensures the economic development of the local population. The multifunctionality and ambiguity of the Oder, visible in the analyzed postcards, correspond with the results of studies indicating that the river is an important element of the city’s landscape and history [

63], which makes it a timeless resource that requires protection [

79].

The changing image of the river has influenced the shaping of the city’s image. The image of Szczecin has evolved but has always been based on its relationship with the Oder River and dependent on its perception and significance. This indicates that the river has always been an important element of the city’s identity, although it has not always been consciously perceived as an autotelic resource that also requires protection.

Today, the Oder, perceived primarily as a space for recreation and leisure, is an important component of the image of Szczecin as a green and waterfront city, friendly to residents and tourists. This contemporary image of Szczecin, as reflected in iconography, aligns with the concept of a sustainable city, combining historical identity with modern spatial development strategies. In this context, the Odra River is a vital part of the city’s green infrastructure, improving quality of life, encouraging social integration, and promoting tourism and recreation. This perception of Szczecin as a waterfront city that is both environmentally and socially friendly embodies a contemporary urban vision grounded in balance between heritage and progress. Once a borderland and industrial space, the river has now become a symbol of openness, continuity, and ecological identity, giving the city the character of a modern, sustainable metropolis where water, nature, and culture form an integrated system of spatial values.

The adopted direction of development of a city that cares for its natural resources and respects the tradition of the place is being implemented through the revitalization of the riverside part of Szczecin, which corresponds to the vision of Szczecin encoded in the city’s brand, Szczecin Floating Garden 2050, according to which the city is to become a water metropolis [

5]. This is the correct direction for development because, in cities where history has played an important role in rebuilding the water identity and many urban planning decisions, revitalization processes are effective, leading to the creation of attractive waterfront public spaces [

35]. Marinas, harbors, tourist cruises, and passenger shipping are slowly becoming elements of Szczecin’s modern, water-based image. These processes fit perfectly into the ideas of sustainable development, becoming a symbol of a return to a more sustainable and resident-friendly model of the city [

61].

The process of redefining the relationship between the city and the river, observed in Szczecin, reflects a broader European trend of waterfront revitalization. Similar transformations can be observed in cities such as Hamburg, Rotterdam, Copenhagen, and Vienna, which in recent decades have successfully transformed their riverfront areas from industrial zones into attractive, multifunctional public spaces. In each of these cases, the river has become a structural axis integrating the city’s economic, recreational, and ecological functions, thereby enhancing the quality of life for residents and increasing the urban competitiveness and image appeal of these cities. Szczecin, much like these centers, is developing a model of a city oriented toward the water. However, unlike many port cities with heavily urbanized waterfronts, Szczecin retains a unique balance between natural and urban landscapes, which distinguishes it from other European waterfronts.

The river and the areas adjacent to it create a public space which, equipped with the ecological and water-related attributes of Szczecin’s identity, becomes a place of events and integration, a kind of cultural center that shapes a sense of belonging. In this context, the Oder is no longer just part of the landscape or urban space but a space of meanings [

80]. The city’s intensive revitalization efforts concerning riverside spaces, such as the redevelopment of Łasztownia, the construction of boulevards, and the restoration of the river for its residents, have both an urban and symbolic function. This is due to the fact that spaces with natural values play a special role in cities as carriers of symbolic meanings [

81,

82].

The evolution of the city’s image and the perception of the river has also made it possible to identify different types of city-river relationships, taking into account spatial and socio-cultural aspects. This approach to the relationship between the city and the river differs from typical typologies, which generally discuss the issue in the context of the city’s location in relation to the river [

55] or the character of their edge, the location of the riverfront in relation to the urbanized area [

83] and waterfront use [

84]. The most desirable types of city-river relationships currently, defined as a city in harmony with the river and a city turned back to the river, are based on the ecological awareness of the community and its cultural identity, which is expressed in investment activities, ways of developing riverside areas, and uses of the river, as well as its protection.

The image of Szczecin currently being promoted shows that the city is actively striving to achieve such a relationship with the river. However, it should be noted that in the era of climate change and the growing importance of sustainable development, Szczecin will face challenges such as the renaturation of riverbanks, floodplain protection, and effective water management, while at the same time preserving its cultural identity. The challenges remain: further development of port infrastructure and restoration of post-industrial areas to urban life, development of waterfront tourism, and increasing the accessibility of riverside areas while implementing the idea of sustainable development and the image of a green city that is responsible and stable. It is also becoming necessary to create so-called “smart waterfronts”, i.e., modern, multifunctional riverside spaces that can fully exploit the potential of the river to improve the quality of life of residents. The enormity of the challenges means that both the image of Szczecin as a green and waterfront city and its relationship with the river require further continuous efforts to implement such ideas. Especially since planning the development of a riverside city requires harmony between economic, ecological, and social functions, while consciously building the city’s image based on an integral element of its landscape—the river.

Despite these challenges, the contemporary image of Szczecin is increasingly aligned with the concept of a sustainable city, based on the integration of environmental, cultural and social elements. The Odra River, which was previously viewed primarily in terms of the economy and transport, has become a symbol of the city’s ecological identity, serving as a natural corridor, a recreational space and a social meeting place. These initiatives strengthen Szczecin’s image as a “Floating Garden”—a metropolis that consciously and responsibly utilizes its unique water potential, harmoniously blending heritage, nature, and modernity into a coherent vision of the city of the future: open, resilient, and people-oriented.