Abstract

Under the global carbon neutrality strategy, green transformation poses significant financial challenges for manufacturers, particularly due to delayed government subsidy disbursements. This study examines a two-echelon green supply chain where a capital-constrained manufacturer utilizes the Uncollected Financial Subsidy Receivable (UFSR) as collateral for financing. Assuming risk-neutral supply chain members, we develop a Stackelberg game-theoretic model to analyze four financing scenarios: no financing, pure subsidy pledge financing, and two hybrid strategies combining subsidy pledges with bank loans or trade credit. Our analysis reveals that the manufacturer’s optimal financing strategy depends critically on its initial capital level and financing costs, with pure subsidy financing being preferable under moderate funding gaps and lower pledge interest rates. The results demonstrate threshold effects where strategy dominance shifts. Furthermore, increasing the subsidy rate consistently enhances product greenness and consumer surplus, whereas its impact on government utility follows an inverted U-shape under certain conditions. These findings provide a theoretical basis for enterprises to optimize financing decisions and for policymakers to design efficient subsidy mechanisms.

1. Introduction

Under the global carbon neutrality strategy, green production has emerged as a critical pathway for driving the transformation and upgrading of the manufacturing sector and achieving high-quality development across nations (Ru et al. [1]). According to Accenture’s 2022 China Consumer Insights Report, nearly all respondents acknowledged the value of environmental protection and sustainable development, with 43% expressing willingness to pay a premium for eco-friendly products (YiMagazine [2]). Higher-income groups demonstrated stronger payment intention for products and services with sustainable attributes. Consequently, the green transformation of enterprises is not only a response to policy incentives and a means to gain competitive advantages but also a strategic move to align with consumers’ growing preference for sustainability. Leading enterprises across various industries are adopting diverse strategies to achieve green transformation. In the energy sector, Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Limited (Ningde, China), the battery supplier for Volvo, operates production lines entirely powered by clean energy (Guo et al. [3]). In the steel industry, Baowu Steel Group (Shanghai, China) pioneered the world’s first hydrogen-based metallurgy project, reducing emissions by over 90% through replacing coke with hydrogen (Pang et al. [4]). And Toyota (Toyota, Japan)’s development of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles and Haier (Qingdao, China) Group’s adoption of recycled materials and smart manufacturing further demonstrate the compatibility of high efficiency with low-carbon production (Kenny et al. [5]). However, these exemplary cases often obscure a fundamental challenge faced by most manufacturing enterprises, particularly small- and medium-sized ones: the substantial investments required for green transition frequently impose significant financial constraints on manufacturers (Taghizadeh et al. [6]). For capital-constrained manufacturers lacking immediate funds to invest in green technologies and production upgrades, this market potential remains largely untapped.

Securing loans from financial institutions such as banks is a conventional approach for businesses to obtain operational funding (Zhang et al. [7]). However, many manufacturers face challenges in accessing credit due to insufficient assets, weak creditworthiness, or unstable financial conditions (Huang et al. [8]). To guide and encourage enterprises in pursuing green transformation, governments worldwide have implemented various subsidy policies, including research and development (R&D) funding, equipment purchase subsidies, and discounted loans (Chen et al. [9]). For instance, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry provided Toyota with approximately 11.2 billion yen in subsidies for low-carbon technology R&D, along with preferential loan interest rates (Li [10]). While such subsidies play a crucial role in promoting industrial green transformation, their disbursement typically follows protracted approval procedures. Such delays can impair manufacturers’ ability to meet production demands and market responsiveness during critical early stages (Tian et al. [11]). For manufacturers attempting green transition, the temporal mismatch between expenditure needs and subsidy disbursement remains unresolved, thereby failing to alleviate the financial constraints faced by enterprises and consequently undermining the intended effects of the policies.

Therefore, in scenarios of subsidy disbursement delays, qualified enterprises may leverage their Uncollected Financial Subsidy Receivable (UFSR) as collateral to secure subsidy-based loans from financial institutions (China Energy Portal [12]). During the loan application process, enterprises are required to submit documentation such as entitlement verification certificates as proof and collateral basis. Financial institutions, adhering to market-oriented principles, utilize reviewed official subsidy lists and enterprise documentation of uncollected subsidies as credit enhancement measures. The loan amount is determined up to the ceiling of the enterprise’s verified but unpaid subsidy funds. For instance, Guangxi Qiquan (Nanning, China) obtained a credit line of 50 million RMB from a bank using its receivable subsidies as collateral (The People’s Bank of China [13]). This collateralized financing approach innovatively transforms future subsidy claims into immediate working capital. From a theoretical perspective, green management theory highlights that policy guidance and financial support provide key resources for firms while also fostering knowledge accumulation and technological innovation, thereby laying the foundation for sustainable development. Economic development theory further stresses that the efficient allocation of financial resources facilitates technological progress and industrial upgrading, thus providing a theoretical basis for green financial instruments to enable green innovation (Wu [14]).

While existing research on government subsidies and supply chain financing is extensive, few studies address the prevalent issue of subsidy disbursement delays and the resulting financing model that uses future subsidy claims as collateral. Recent literature has begun to explore innovative financing forms like carbon asset pledging (Oyewo et al. [15]) and intellectual property financing (Fan et al. [16]). However, these methods are primarily suitable for firms possessing such specific assets. In contrast, government subsidies represent a future, predictable cash flow that can be discounted and activated upfront to improve corporate liquidity. A critical distinction from conventional accounts receivable financing lies in the high certainty of government subsidies. This certainty provides an implicit credit enhancement backed by government credibility, significantly reducing risks for lenders. Therefore, given the potential of this emerging financing mechanism, it is necessary to investigate how it can alleviate financial constraints in the green transition and influence the green production decisions of capital-constrained manufacturers.

To address these gaps, our study examines how capital-constrained manufacturers can utilize delayed subsidies as financing instruments through pledge mechanisms. Specifically, we aim to address three research questions:

- How does subsidy-based pledge financing, by alleviating manufacturers’ capital constraints, influence their optimal green R&D investment and product pricing decisions?

- What financing strategies should capital-constrained green manufacturers adopt under varying conditions?

- How does subsidy-based pledge financing affect consumer surplus and government benefits?

To address these research questions, this study employs a two-echelon green supply chain framework comprising a manufacturer and a retailer. Under the condition of delayed subsidy disbursements, we consider how a capital-constrained manufacturer utilizes subsidies for pledge financing. Based on whether pure subsidy pledge financing can fully cover the manufacturer’s funding gap, we develop three analytical models: pure subsidy pledge financing, hybrid pledge financing, and a non-financing benchmark scenario. This framework allows us to analyze the manufacturer’s optimal financing strategy choices and their corresponding operational decisions under different financing approaches. Furthermore, we compare the impacts of different financing modes on consumer surplus and government benefits.

The contributions of this paper are primarily reflected in three aspects. First, by studying the impact of subsidy pledge financing models on green supply chain production decisions, this paper expands the financing options available to green manufacturers and provides a new perspective for green supply chain financing theory research. Second, considering whether the financing amount obtained through subsidy pledges is sufficient, this paper examines hybrid financing strategies that combine subsidy pledges with other financing methods, thereby broadening the applicability of subsidy pledge financing. Third, by analyzing the promotional effects of various financing strategies on the benefits of supply chain members and social welfare, this study provides theoretical basis for enterprise financing strategy selection and government subsidy policy optimization.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature related to our research. Section 3 presents the model assumptions and establishes the benchmark model. Section 4 derives the equilibrium outcomes for supply chain members under different financing strategies. Section 5 conducts a comparative analysis of results across various financing approaches. Section 6 employs numerical analysis to extract additional managerial insights. Section 7 concludes the study by summarizing key findings, presenting managerial implications, and suggesting directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

This study builds upon two key strands of literature: supply chain financing strategies and government subsidy policies related to green and sustainable supply chains. This section reviews existing research in both areas and highlights the distinctive contributions of our work relative to prior studies.

2.1. Government Subsidy Policies

Government subsidies serve as a crucial policy instrument for enhancing the environmental performance of manufacturing enterprises. Existing research on government subsidies primarily focuses on the recipients, types, and amounts of subsidies. In green supply chains, common subsidy forms include R&D cost subsidies, unit production subsidies, and green level subsidies [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. The recipients of these subsidies can encompass suppliers, manufacturers, retailers, and consumers [25,26,27,28,29,30].

This paper focuses specifically on government subsidies directed at manufacturers within the supply chain. Numerous studies have examined how subsidies for manufacturers affect overall supply chain sustainability. For instance, Barman and Sana [17] explored government subsidy policies in green manufacturing processes to analyze their impact on green manufacturing activities. Babaei et al. [18], by evaluating government non-supervision and supervision policies in enterprise production, found that government policies significantly impact producers’ profits and that subsidies promote the application of green production technologies. Pal and Sarkar [19] discovered that within a closed-loop green supply chain structure, government subsidies positively promote both the manufacturer’s green innovation level and profit. Chen et al. [9] compared production subsidies versus R&D subsidies for joint ventures, finding that combining both subsidy types yields the least favorable outcomes, while R&D subsidies prove more beneficial for manufacturers in joint venture settings. Vaseem and Venkataraman [20] found that government policies involving taxing gasoline vehicle manufacturers and providing subsidies to electric vehicle manufacturers can significantly increase the deployment speed of electric vehicles in developing countries. Qiu et al. [21] analyzed two subsidy policies: green R&D subsidies and production cost subsidies. They found that wholesale and retail prices decrease with production cost subsidies but increase with green R&D subsidies. Khorshidvand et al. [22], by comparing operational models with and without subsidies, identified an optimal subsidy level that maximizes supply chain benefits in both decentralized and collaborative models. Zolfagharinia et al. [23] examined government funding for green product R&D and found that subsidy levels do not affect the relationship between environmental quality and marketing strategies in underdeveloped green markets. Conversely, Ghosh et al. [24] argue that higher subsidies particularly benefit enterprises with lower green transformation costs.

Beyond the direct subsidies to manufacturers mentioned above to promote green production, there are also subsidy initiatives targeting other supply chain members, which help comprehensively promote the construction and improvement of the green supply chain. Yuan et al. [25], based on dynamic game theory and principal-agent theory, analyzed the impact of government subsidy strategies targeting retailers on optimal supply chain decisions. The results indicate that an increase in the subsidy coefficient promotes the retailer’s sales effort level. Long et al. [26] observed that increasing price subsidies for consumers benefits both market demand and social welfare. Zaman and Zaccour [27] focusing on car purchase policies where consumers are the subsidy recipients, found that the government increasing the subsidy amount encourages consumers to replace old vehicles, thereby expanding market demand.

Some scholars have compared different subsidy recipients to identify which member should receive subsidies for optimal outcomes. Saha et al. [28], by comparing consumer subsidies and manufacturer subsidies, concluded that when supply chain members cooperate, subsidizing the manufacturer leads to higher profits. Meng et al. [29] suggested that compared to subsidizing suppliers, the government tends to prefer subsidizing core manufacturers, as this can stimulate the entire supply chain to implement green innovation, benefiting environmental and economic performance as well as social welfare. Xue et al. [30] studied the impact of government subsidy strategies under different supply chain structures. When the government provides a unified subsidy strategy, retailer-led supply chains can bring about more environmentally friendly products and greater social welfare.

Although extensive literature confirms the significant importance of government subsidy policies for industrial green transformation and upgrading, it often overlooks the fact that subsidy disbursement requires established procedures and cycles, frequently leading to delays. Such delays constrain the manufacturer’s production activities and responsiveness to market demand in the initial stages, thereby diminishing the promotional effect of the subsidy policy. Consequently, this paper uses subsidy delay as the research background to explore the operational and financing strategies of green manufacturers.

2.2. Green Supply Chain Finance

Currently, against the backdrop of government policy guidance and increasing public environmental awareness, green transformation has become an inevitable trend. However, emerging green markets require high investment costs and still face a significant green financing gap (Wasan et al. [31]). Beyond direct government financial support, green finance also includes market-based financing.

Existing literature has explored financing instruments for corporate green innovation, primarily including green bonds, green credit, green equity financing, green insurance, among others [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Green bonds are bond instruments issued to fund or refinance green projects that meet specified conditions. Liu et al. [32] suggest that green bonds, as specialized financing tools, can provide stable long-term funding and promote corporate green R&D. Harichandan et al. [33] found that green bonds are an important tool for addressing the complex financial relationships and demand drivers present in the hydrogen supply chain for green clean energy. Gan et al. [34] found that green bonds can also play a role in reducing information asymmetry between enterprises and enhancing mutual trust within the supply chain. Green credit refers to preferential loans provided by financial institutions like banks to green projects or enterprises and is a common means for companies to obtain green financing. Lin and Pan [35] argue that green credit policies are significant for corporate low-carbon development and green transformation, and can also positively influence upstream and downstream enterprises in the supply chain. Green equity financing involves raising capital by issuing stocks for specific green projects or an overall green transformation. Liang and Zhang [36] developed an equity financing model based on a supply chain requiring green transformation. Comparing it with green credit financing, they found that equity financing is a strategy that creates win-win outcomes for the supply chain, consumers, and social welfare. Ma et al. [37], studying a retailer-driven carbon emission reduction equity financing strategy, found that under various circumstances, the retailer can still benefit even when facing supplier encroachment on its profits. Green insurance is an emerging research focus in recent years, involving insurance products that provide coverage for environment-related risks, such as covering economic compensation and remediation costs for environmental pollution damage caused by sudden accidents. Liu et al. [38] argue that green insurance plays a crucial bridging role in the green transformation of the construction industry. Chen et al. [39] found that under sustainable insurance, the application of corporate carbon capture and storage technology can reduce the default risk for insurance companies. Evidently, green finance, as a financial innovation tool integrating finance and environmental protection, optimizes resource allocation and promotes the green transformation of supply chains.

Furthermore, financing strategies can be categorized based on the source of funds into external financing and internal financing. Supply chain external financing refers to enterprises obtaining funds through financial institutions like banks or capital markets, including bank financing (Kouvelis and Zhao [40]) and platform financing (Mandal et al. [41]). Supply chain internal financing refers to funds circulated between upstream and downstream enterprises within the supply chain, utilizing methods like trade credit for advance payments or delayed payments (Yu et al. [42]). It is an important source of short-term financing within the supply chain. To address capital constraints in the supply chain, scholars often compare internal and external financing strategies to analyze which is most beneficial for supply chain members. For example, Chen et al. [43] found that when a capital-constrained manufacturer can choose between retailer financing or bank financing, retailer financing is superior if its production cost is low. Hu [44] compared bank financing, equity financing, and trade credit financing models, finding that the financing model choice for capital-constrained enterprises is related to the power structure and capacity building within the supply chain. Chen and Chen [45] analyzed the optimized operational strategies for trade finance and external finance, when platform fees are reasonable, the use of blockchain platforms can create a favorable win-win situation. Beck [46], through empirical research, found that smaller and micro-enterprises use external financing less frequently and prefer internal supply chain financing instead.

And supply chain financing often requires high creditworthiness and collateral conditions. When enterprises are small or have lower credit levels, they can achieve credit enhancement through third-party credit guarantees (Lai et al. [47]). Furthermore, a common form of collateral is movable asset pledge, involving tangible, movable assets. For instance, a capital-constrained manufacturer can pledge its inventory to obtain a loan (Matta and Hsu [48]). However, with the development of the knowledge economy and digital economy, corporate asset structures have changed significantly, with intangible assets and various rights/assets increasingly constituting a larger share. Scholars have explored accounts receivable pledge financing (Li et al. [49]), equity pledge (Pan and Qian [50]), carbon asset pledge (Fu et al. [51]), and intellectual property pledge financing (Wang and Sun [52]), among others. This type of rights-based pledge, especially accounts receivable pledge, shares structural similarities with the subsidy pledge financing discussed in this paper. The key difference lies in the higher credit quality of subsidy pledge financing due to government backing, which means existing accounts receivable financing theories based on commercial credit risk cannot be directly applied to the subsidy pledge context (Wang et al. [53]). Subsidy pledge financing is a more reliable and accessible financing tool.

These literature studies various financing strategies for capital-constrained supply chains. However, few studies consider delayed subsidies as a significant resource for enterprises. The subsidy pledge financing model can not only activate a company’s future assets but also provide a high-credit, easily operable channel to address initial capital constraints in the supply chain. Furthermore, some scholars have studied subsidy pledge financing strategies in the context of closed-loop supply chains (Liu et al. [54]). The difference in this paper is that their focus was primarily on the remanufacturing supply chain area. They did not consider the adequacy of the pledge financing, whether it needs to be combined with other financing methods, or the promoting effect of this model on supply chain member benefits and social welfare. Consequently, their work cannot provide universal and targeted suggestions for green-transforming manufacturers. Therefore, this paper will focus on analyzing the subsidy pledge financing model and provide operational decisions and guidance for stakeholders under this financing strategy.

2.3. Summary

The reviewed literature on government subsidy policies promoting green development, financial tools for green supply chains, and different financing methods has conducted substantial research on the financing strategies and operational decisions of capital-constrained enterprises, laying a foundation for understanding the policy-finance interplay in green supply chain management. Existing research generally confirms that government subsidies can effectively incentivize enterprises to increase green R&D investment and adopt environmentally friendly technologies, enhancing overall supply chain sustainability through various subsidy recipients and forms. Regarding financing, scholars have explored various internal and external financing tools, including green bonds, green credit, equity financing, and trade credit, analyzing their relative advantages and disadvantages in alleviating corporate capital constraints and promoting green innovation. Some studies have further investigated pledge financing models based on various rights, providing important insights into innovative structures of supply chain financing.

Based on this, this paper focuses on capital-constrained green-transforming manufacturers under the background of delayed government subsidy disbursement. It delves into the impact of subsidy pledge financing on manufacturers’ decisions regarding green R&D investment, pricing, etc. Simultaneously, it analyzes the optimal financing strategies for capital-constrained manufacturers under different conditions and the promoting role of subsidy pledge financing on supply chain member benefits, consumer surplus, social welfare, and other aspects.

3. Model Assumptions and Description

3.1. Model Assumptions

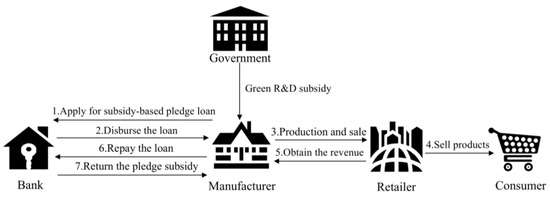

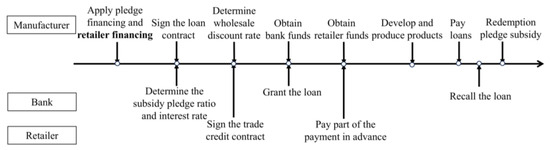

This study focuses on a supply chain consisting of a capital-constrained manufacturer (M) and a capital-abundant retailer (R). The manufacturer wholesales products to the retailer, who then sells them to end consumers. As government policies and social initiatives increasingly support green products, the manufacturer seeks to upgrade production equipment via green investments for manufacturing environmentally friendly goods. Here, the government (G) provides subsidy based on the manufacturer’s R&D expenditure. However, if subsidy disbursement is delayed, the manufacturer must still bear the financial pressure of insufficient green innovation funding. To address this, the capital-constrained manufacturer may apply for subsidy-based pledge loan from a bank by pledging its UFSR. The bank evaluates the subsidy amount and determines a pledge rate. Upon approval, it grants the loan to the manufacturer. During the pledge period, the manufacturer conducts production activities and repays the principal plus interest at maturity to redeem the pledged subsidy. The manufacturer’s subsidy-based financing workflow is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The manufacturer’s subsidy-based financing workflow.

For modeling clarity, all notations and their definitions are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Notation and definition.

To balance realism and simplicity in modeling, we make the following assumptions.

Assumption 1.

The market demand for green products exhibits a negative correlation with the retail price (p) and a positive correlation with the green level (e), expressed as D = a − p + δe, where a represents the baseline market demand, 0 < δ < 1 denotes the consumers’ green preference coefficient (Zhang et al. [7], Chen et al. [9]).

Assumption 2.

The manufacturer has initial capital I. Due to the disproportional relationship between R&D investment and output, the green investment cost is modeled by a quadratic function of the form ke2/2, where 0 < k < 1 is the green R&D cost coefficient. This function has a wide range of applications (Chen et al. [45], Wang and Sun [52], Liu et al. [54]).

Assumption 3.

Referring to Chen et al. [9] and Tian et al. [11], The government subsidizes the manufacturer’s R&D costs at a rate s, resulting in a total green product subsidy of S = s(ke2/2).

Assumption 4.

This study focuses on a manufacturer utilizing government subsidies as a financing channel. Under delayed subsidy disbursement scenarios, banks evaluate the manufacturer’s subsidy amount and set a pledge rate σ. The subsidy-based loan interest rate is r, while the ordinary loan interest rate is rb, with the condition that r < rb (Liu et al. [54]), with both rates remaining fixed during the loan term, similar to Beibu Gulf Bank’s practice of offering 1–2 percentage point discounts on subsidized loans for renewable energy projects.

Assumption 5.

Both supply chain members are rational and risk-neutral entities that pursue profit maximization as their sole objective.

3.2. Benchmark Model Description

Based on the above assumptions, the benchmark model examines the scenario where the manufacturer’s initial capital I is insufficient to fund green product R&D and production activities, and the manufacturer does not pursue external financing (Strategy N). The profit functions of the manufacturer and retailer are derived as shown in Equation (1).

To solve for the optimal solution, we construct the Lagrangian function for the manufacturer’s profit as follows:

By applying the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) optimality conditions, we derive the solution. When λ = 0, it follows that , indicating the manufacturer faces no capital constraints. When λ > 0, this implies , meaning production and R&D activities must rely solely on the initial capital I, reflecting binding financial constraints. Here, the positive value of λ represents the shadow price of I. When is satisfied, the optimal decisions and corresponding profits for both the manufacturer and retailer are given by:

where the expression for λ is provided in Appendix A. The proofs of all Lemmas, Propositions and Corollaries are in Appendix B.

4. Subsidy-Based Pledge Financing

Government subsidies play a pivotal role in advancing green transformation, yet their delayed disbursement significantly undermines manufacturers’ ability to respond to market demands. To address this temporal mismatch issue, a UFSR-based pledge financing model has emerged in practice. Notably in China’s Xinjiang Green Finance Pilot Zone where enterprises can secure working capital loans covering up to 90% (pledge ratio σ = 0.9) of their outstanding government subsidies under the Green Energy Subsidy Loan Program. This model enables qualified enterprises to use UFSR as collateral, with its high certainty and government credit backing constituting the credit enhancement foundation that distinguishes it from ordinary accounts receivable, thereby establishing both the practical and theoretical necessity for this study’s focus on subsidy pledge financing rather than other asset-based financing mechanisms.

Within this institutional framework, financial institutions follow market-oriented principles, using enterprises’ entitlement verification certificates and officially published subsidy lists as the basis for credit enhancement, with the final loan amount capped at the verified value of uncollected subsidy funds. To tackle the manufacturer’s financing constraints, this section examines an innovative subsidy-based pledge financing model.

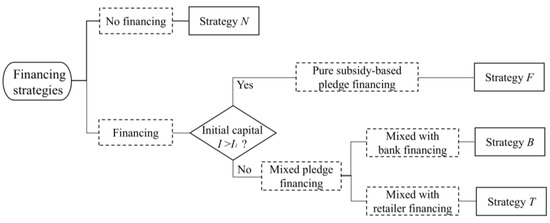

The manufacturer faces two distinct scenarios when utilizing UFSR financing: when the funds obtained through UFSR can fully cover the R&D and production funding shortfall (, is the threshold at which UFSR financing exactly covers the funding shortfall for production and R&D), it may adopt a pure subsidy-based pledge financing strategy (Strategy F). When UFSR financing alone proves insufficient to meet production and R&D costs (), the manufacturer must supplement it with either bank financing (which we term B-UFSR financing; Strategy B) or retailer financing (T-UFSR financing; Strategy T) to fulfill its operational needs, with the specific financing strategies illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Manufacturer Financing Strategies.

4.1. Pure Subsidy-Based Pledge Financing Strategy (Strategy F)

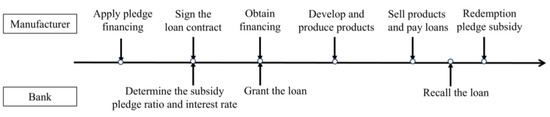

Under Strategy F, where the manufacturer’s funding gap remains relatively small, using the UFSR to finance can effectively resolve capital constraint. Firstly, the manufacturer applies to the bank for a subsidy-based pledge loan. Secondly, the bank reviews the manufacturer’s eligibility for government subsidies, and both parties sign a subsidy-based pledge loan agreement. Thirdly, the manufacturer obtains the pledge loan and determines its production decisions. Finally, at the end of the sales period, the manufacturer repays the principal and interest to the bank to redeem the pledged deferred government subsidy funds. The complete event sequence is detailed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Sequence of Events under Strategy F.

And the manufacturer’s profit function is modified as shown in Equation (2):

Proposition 1.

Under Strategy F, when is satisfied, the optimal decisions and profits for both the manufacturer and the retailer are as follows:

Among these, is crucial for ensuring the existence of a unique optimal solution for the manufacturer’s profit function. In practical terms, this condition implies that green technology R&D inherently involves certain thresholds and costs, which aligns with the realities of industrial upgrading in most sectors.

According to Proposition 1, the product greenness is positively correlated with the potential market size, indicating that greater market potential can incentivize manufacturers to invest more in green R&D. Secondly, the green R&D cost coefficient has a significant negative impact on greenness, suggesting that technological difficulty is a major barrier to green transformation. In addition, the decision variables and profits of supply chain members are all influenced by the subsidized pledge financing interest rate, while the level of the manufacturer’s initial capital I only affects its own profit.

Corollary 1.

(i) When , we have , , ; and when , we have , , . (ii) , .

Corollary 1 demonstrates that the relationship between government subsidy rates and decision variables reverses depending on subsidy-based loan interest rate: a positive correlation emerges under low interest rate, whereas a negative correlation prevails under high rate. This reversal occurs because lower financing costs reduce manufacturer’s capital constraints, allowing it to leverage increased subsidies to enhance green R&D efforts and improve product sustainability, ultimately passing the costs through higher wholesale and retail prices. Conversely, higher financing costs force the manufacturer to prioritize immediate liquidity over long-term investments, leading to cost-cutting measures and price reductions to maintain demand. Crucially, regardless of the interest rate regime, higher interest rate consistently benefits both the manufacturer and the retailer, though through fundamentally different operational mechanisms.

The reversal relationship in Corollary 1 stems from the interplay between the income and substitution effects. Under low interest rates, the income effect dominates, leading firms to invest subsidy increases into R&D and recoup costs via price premiums. Under high rates, the substitution effect dominates, forcing firms to divert subsidies to cover operational costs, potentially even reducing prices. This implies that manufacturers should strategically align their financing choices with market conditions: aggressively pursue R&D with low-cost subsidized loans but prioritize cash flow and seek alternative financing when rates are high.

Corollary 2.

- (i)

- When either (a) or (b) and , ; when and , .

- (ii)

- When , ; otherwise, . When , ; otherwise, .

- (iii)

- When , ; otherwise, .

- (iv)

- When , ; otherwise, .

The expressions for and are shown in Appendix A.

Corollary 2 shows that under Financing Strategy F, the manufacturer’s product greenness level is jointly constrained by the subsidy-based loan interest rate and the green R&D cost coefficient, subsequently influencing pricing decisions for both supply chain members. When the green R&D cost coefficient is low, product greenness exhibits a U-shaped relationship with the interest rate, initially declining then recovering as r increases, whereas under higher cost coefficients, greenness monotonically decreases with rising r. This indicates that while increased financing costs generally suppress green innovation, the manufacturer with higher R&D efficiency can offset financial pressure through green premium pricing, ultimately achieving improved sustainability performance. Consequently, the R&D efficiency plays a pivotal role in determining both environmental outcomes and profitability, underscoring the necessity for the manufacturer to prioritize R&D capability enhancement during green transitions.

Furthermore, the pledge interest rate exhibits an inverted U-shaped relationship with the retailer’s profit, indicating that a moderate rate increase benefits the retailer. An optimal interest rate range exists where the retailer can capitalize on green premium gains while mitigating the risk of cost pass-through from the manufacturer, thereby maximizing profits. As established in Proposition 1, the manufacturer’s initial capital only affects its own profitability. When the initial capital exceeds a certain threshold, rising interest rate enhances the manufacturer’s earnings; conversely, below this threshold, a higher rate exacerbates cost pressures, reducing R&D investment and overall profitability.

The aforementioned boundary conditions carry significant economic implications, as they delineate the strategic decision intervals for manufacturers under different financing costs. When the interest rate falls below the critical threshold, enterprises should prioritize allocating funds to green R&D, seeking market premiums by enhancing product sustainability. Conversely, when the interest rate exceeds the critical value and R&D costs remain high, manufacturers should shift their focus toward optimizing production processes, controlling costs, and adopting conservative pricing strategies to maintain market share. When utilizing subsidy pledge financing, enterprises must comprehensively evaluate their capital status, R&D efficiency, financing costs, and market green preferences to inform their decision-making.

4.2. Hybrid Financing Strategies

When the manufacturer’s financing needs cannot be fully met through UFSR loan alone, additional financing methods must be incorporated. In the hybrid financing, we consider two alternative approaches: the manufacturer may opt for ordinary bank loans (B-UFSR financing) or trade credit financing from the retailer (T-UFSR financing). This represents a fundamental trade-off between external market-based financing and internal relationship-based financing.

Under B-UFSR financing, the manufacturer first utilizes lower-cost UFSR loans backed by government subsidies, then applies for higher-interest ordinary bank loans only to cover the remaining funding gap. This financing sequence aligns with the corporate principle of minimizing financing costs.

Under T-UFSR financing, the retailer, as the core downstream enterprise in the supply chain, possesses inherent advantages in accessing information about the manufacturer’s operational status, product quality, and end-market demand. This informational advantage reduces both monitoring costs and default risk when providing financing to the manufacturer. Consequently, retailers are generally willing to offer advance payments in exchange for wholesale price discounts. This supply chain collaboration-based financing model not only helps alleviate the manufacturer’s financing constraints but can also achieve Pareto improvement for the overall supply chain.

In summary, the emergence of hybrid financing strategies represents a rational corporate decision within complex financing environments. The following section will formally analyze supply chain equilibrium decisions under these two hybrid financing strategies through mathematical modeling and conduct an in-depth comparison of their differences.

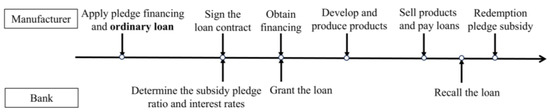

4.2.1. B-UFSR Financing (Strategy B)

Under Strategy B, the manufacturer first applies to the bank for the UFSR pledge loan. Any remaining funding gap beyond this will be covered through an ordinary bank loan. Secondly, upon receiving the manufacturer’s applications for both the UFSR pledge loan and the ordinary bank loan, the bank reviews the manufacturer’s qualifications, including government subsidy eligibility and corporate creditworthiness. After approval, the two parties sign separate loan agreements for the subsidy-based pledge loan and the ordinary bank loan, specifying the pledge ratio, the interest rate for the first-stage subsidy-based pledge financing, the interest rate for the second-stage ordinary bank loan, and their respective credit limits. Thirdly, the manufacturer receives both loans and finalizes its production decisions. Finally, at the end of the sales period, the manufacturer repays the principal and interest of both loans to the bank. The sequence of events is detailed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Sequence of Events under Strategy B.

The profit functions for the manufacturer and retailer are as follows:

Proposition 2.

Under Strategy B, where the manufacturer adopts hybrid financing combining subsidy-based pledge with ordinary bank loan, the optimal decisions and profits for both manufacturer and retailer are given by the following when is satisfied:

According to Proposition 2, the following corollaries can be obtained.

Corollary 3.

- (i)

- When , we have , , , , , ; and when , , , , , , .

- (ii)

- , , , .

Corollary 3 shows the evolving patterns of supply chain decisions under varying degrees of financing pressure faced by the manufacturer. Under low-intensity financing pressure (characterized by a lower second-stage loan interest rate rb and an increased subsidy pledge ratio σ) or high-intensity pressure (with a higher rb in the second stage and an increased pledge interest rate r in the first stage), the supply chain tends to enhance product greenness and raise pricing. Conversely, under moderate financing pressure (featuring a lower rb in the second stage coupled with an increased r in the first stage, or a higher rb in the second stage alongside an increased σ), the supply chain tends to reduce product greenness and lower prices. This behavior stems from manufacturer’s strategic responses: under low financing pressure, it prioritizes green R&D to elevate product sustainability; under moderate pressure, they adopt a conservative approach by minimizing R&D expenditures, maintaining lower greenness, and relying on price reductions to sustain sales volume for higher revenue; whereas under high financing pressure, mere price cuts prove insufficient to cover financing costs, prompting increased R&D investments to leverage green product premiums for greater profitability.

Therefore, when manufacturer experiences either relatively low or high financing pressure, it is more advantageous to improve product greenness while raising wholesale and retail price. In contrast, under moderate financing pressure, appropriately scaling back R&D investment to reduce product greenness and implementing price reductions can optimize supply chain efficiency. Moreover, from a profitability standpoint, while an increase in the first-stage pledge interest rate erodes profits for both the manufacturer and retailer, a higher subsidy pledge ratio enhances earnings for supply chain members. This highlights the significant impact of bank financing policy adjustments on overall supply chain performance.

Corollary 4.

- (i)

- When , ; otherwise, .

- (ii)

- When , ; otherwise, . When , ; otherwise, .

- (iii)

- When , ; otherwise, . where is the critical threshold of initial capital at which the manufacturer’s profit and the bank’s ordinary loan rate exhibit a joint effect.

The expressions for , and are shown in Appendix A.

Corollary 4 reveals the dual impact of first-stage pledge interest rate and second-stage ordinary loan interest rate on supply chain decision-making under Strategy B. A critical threshold exists for the initial financing rate-below this benchmark, elevating the second-stage rate produces a modest yet discernible improvement in product sustainability. Conversely, when first-stage financing costs surpass this pivotal value, a heightened second-stage rate creates substantial financial strain, compelling the manufacturer to curtail R&D expenditures and compromise environmental performance. In response, supply chain participants strategically recalibrate pricing mechanisms to preserve financial equilibrium.

In essence, whether a company can transform high financing costs into high-quality output ultimately depends on its capital buffer capacity. With a strong buffer, it can convert pressure into motivation; without it, the company has no choice but to cut future investments to survive the immediate crisis. Notably, the manufacturer’s profit sensitivity to ordinary loan interest rate variations mirrors the pattern established in Corollary 2 for pledge interest rate, while the retailer’s profit trajectory in relation to second-stage rate adjustments presents a more nuanced relationship that warrants detailed examination in subsequent numerical simulations.

4.2.2. T-UFSR Financing (Strategy T)

When subsidy pledge financing cannot fully cover the funding gap, manufacturers may also consider seeking trade credit from retailers as supplementary financing. This strategy is built upon collaborative relationships within the supply chain. Retailers provide financing through advance payments in exchange for wholesale price discounts. This approach not only alleviates the manufacturer’s liquidity constraints and ensures stable supply of green products but may also generate long-term benefits for retailers through sales promotion.

The sequence of events under Financing Strategy T unfolds as follows: First, the manufacturer applies for UFSR pledge loan from the bank, then seeks trade credit financing from the retailer to cover any remaining funding shortfall. Second, the bank evaluates the manufacturer’s subsidy eligibility and, upon approval, establishes a UFSR pledge loan agreement specifying both the pledge ratio and subsidy-based loan interest rate. Third, the manufacturer negotiates trade credit terms with the retailer, offering wholesale price discounts in exchange for advance payments, with the retailer providing the outstanding amount L () after collateralization prior to production commencement. Finally, upon concluding the sales period, the manufacturer repays the loan to the bank. This operational sequence is visually detailed in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Sequence of Events under Strategy T.

Under this financing strategy, the profit functions of the manufacturer and retailer are as follows:

The fourth term in Equation (5) quantifies the difference in total wholesale costs for the units purchased by the retailer through advance payment L before and after price discounts, representing the manufacturer’s trade credit financing cost.

Proposition 3.

Under Strategy B, the manufacturer utilizes a hybrid financing approach combining subsidized collateralization with retailer credit financing. When holds, the optimal decisions and corresponding profits for both manufacturer and retailer are as follows:

Proposition 3 demonstrates that Financing Strategy T differs fundamentally from Strategies F and B in terms of capital dependency. While under Strategies F and B the manufacturer’s initial capital only influences its own profits, Strategy T’s internal financing mechanism creates mutual dependence where both supply chain members’ optimal profits are affected by the manufacturer’s initial funding position.

Corollary 5.

- (i)

- , , , , .

- (ii)

- , , , . When , ; otherwise, .

Corollary 5 shows that under Strategy T, the first-stage pledge loan interest rate exhibits negative correlations with product greenness level, supply chain pricing, and profitability, whereas the subsidy pledge ratio shows positive relationships with these factors, demonstrating that an increased pledge interest rate adversely affects the entire supply chain. Furthermore, the wholesale price discount rate significantly moderates the relationship between the pledge ratio and retailer profits: lower discount rate makes higher pledge ratio beneficial for the retailer, while higher discount rate forces the manufacturer to transfer financing costs through increased pre-discount wholesale prices, ultimately disadvantaging the retailer. The finding suggests that while elevated pledge interest rates are detrimental to all members, an appropriately set wholesale discount can align incentives and create mutual benefits for both the retailer and the manufacturer.

Corollary 6.

- (i)

- , , , .

- (ii)

- When , ; otherwise, .

Corollary 6 shows that an increase in the second-stage wholesale price discount rate negatively impacts product greenness, retail price, and retailer profitability, while positively influencing the manufacturer’s wholesale price. This occurs because higher discount rates reduce the retailer’s effective procurement costs, thereby squeezing the manufacturer’s profit margin and leading to cuts in green R&D investment and subsequent deterioration in product sustainability. To offset financing costs, the manufacturer raises nominal wholesale prices, while the retailer lower retail prices to maintain sales volume—ultimately reducing its own profits. A real-world parallel can be observed in Tesla (Austin, TX, USA)’s 2022 pricing strategy: facing rising battery material costs, the automaker repeatedly increased wholesale prices for certain models, but due to intense market competition and consumer price sensitivity in the EV sector, dealer price hikes resulted in demand contraction. Notably, the discount rate’s effect on manufacturer profits follows the same pattern established in Corollary 2.

5. Comparison and Analysis

To examine the differential effects of subsidy strategies, this section conducts a comparative analysis of equilibrium outcomes across the three financing strategies.

5.1. Optimal Manufacturer Financing Strategy

Proposition 4.

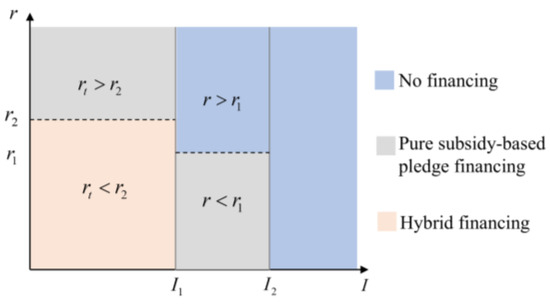

The manufacturer’s choice of optimal financing strategy depends on its initial capital level and different financing interest rates, with distinct profit outcomes observed across different strategies. The selection criteria are as follows:

- (i)

- When , no financing is employed.

- (ii)

- When and , no financing is employed; When and , pure subsidy-based pledge financing is implemented.

- (iii)

- When and (taking rt under hybrid financing as an example), pure subsidy-based pledge financing is selected; when and , hybrid financing is adopted.

- (iv)

- Under hybrid financing, Strategy B is selected when holds, while Strategy T is adopted when holds.

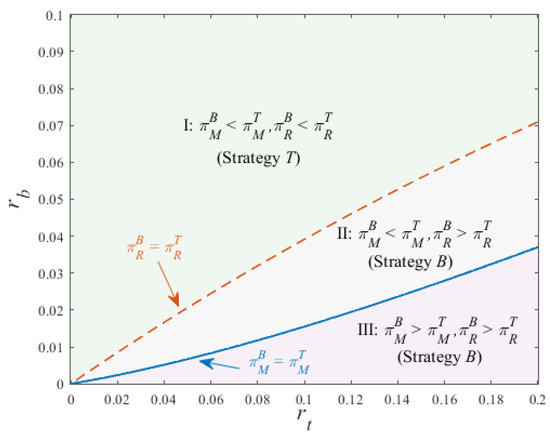

Here, represents the critical threshold at which pure subsidized collateral financing exactly covers the funding gap, while denotes the threshold for sufficient capital availability. , and represent the critical loan interest rates for determining the optimal financing strategy across different intervals of initial capital.

The expressions for , and are shown in Appendix A. And the complete strategy selection mechanism is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Optimal Manufacturer Financing Strategy.

The manufacturer’s initial capital level I falls into three distinct intervals governing financing decisions. (i) For , the capital suffices to fully cover production and green R&D expenditures without financial constraints; (ii) When , the relatively adequate capital allows the manufacturer to bridge the funding gap exclusively through Strategy F, making this the preferred choice; (iii) In cases where , the capital shortage necessitates hybrid financing as subsidy-based pledge financing alone becomes insufficient. Crucially, financing rates further modulate strategy selection: within the range, despite a funding gap, a high collateral interest rate can mean that using its own capital for production and R&D is more profitable for a manufacturer than subsidy-based pledge financing. This can lead the manufacturer to avoid external funding altogether. Conversely, for , excessively high second-stage loan interest rates can reduce the profitability of hybrid financing below that of subsidy-based pledge financing, compelling the manufacturer to persist with pure subsidy-based pledge financing even when it does not fully cover the shortfall. It is clear that prohibitively high interest rates discourage the manufacturer from seeking financing. The manufacturer’s financing decision essentially involves striking a balance between the funding gap and the financing cost.

5.2. Analysis of Environmental and Economic Impacts Across Financing Strategies

In this section, we compare the pure subsidy-based pledge financing approach with two hybrid financing strategies, analyzing their respective impacts on product greenness levels, wholesale pricing and retail pricing, which leads to the following propositions.

Proposition 5.

- (i)

- When , ; otherwise, .

- (ii)

- When , ; otherwise, .

- (iii)

- , .

Compared to hybrid financing strategies, Strategy F offers distinct advantages in terms of smaller funding gaps and lower financing costs, making it more effective in driving product green transformation and upgrading, thereby enhancing market share and promoting sustainable green development. However, under Strategy T, if the manufacturer can secure financing from the retailer at a lower wholesale price discount rate, the synergistic effects of internal supply chain financing can elevate both the greenness level and market demand, potentially surpassing Strategy F. This dynamic serves as a powerful mechanism for market expansion, simultaneously solidifying the supply chain’s competitive edge and elevating its brand positioning among environmentally conscious consumers.

Proposition 6.

- (i)

- When , ; otherwise . And when , ; otherwise, .

- (ii)

- When , ; otherwise, . And when , ; otherwise, .

The expressions for , , , and are shown in Appendix A.

As established in Proposition 6, supply chain members optimize pricing strategies to maximize economic benefits under varying conditions. Under Strategy F, the relatively lower financing pressure enables more flexible and favorable pricing decisions. In contrast, hybrid financing strategies exhibit distinct trade-offs: when financing costs are high, constrained R&D budgets compel the supply chain to implement price reductions to stabilize market share; conversely, when financing costs are relatively low, while cost transfer through wholesale price increases becomes feasible, such pricing adjustments risk demand suppression and consequent profit erosion. Therefore, Manufacturers should coordinate pricing with retailers to maintain stable demand rather than unilaterally raising wholesale prices under financing pressure. Retailers, in turn, should strategically employ marketing efforts to cushion demand-side impacts when accepting necessary price increases to ensure supply continuity.

Furthermore, given the complexity of optimal decision-making under the two hybrid financing strategies, we standardize the ordinary bank loan interest rate and wholesale price discount to be equivalent (), enabling a direct comparative analysis between Strategy B and Strategy T under identical financing cost conditions.

Proposition 7.

- (i)

- , , , .

- (ii)

- When , ; otherwise, .

- (iii)

- When , ; otherwise, , where is the threshold of the manufacturer’s initial capital that affects the retailer’s profit under hybrid financing.

The expression for is shown in Appendix A.

Proposition 7 demonstrates that when the bank loan interest rate equals the wholesale price discount rate, Strategy T yields superior outcomes for the manufacturer, including a higher product greenness level, greater market demand, increased wholesale pricing, and enhanced profitability compared to Strategy B. From the retailer’s perspective, financing provision is more favorable when dealing with the manufacturer possessing lower initial capital. Although the manufacturer with initial capital above a certain threshold could achieve higher returns through retailer financing, a rational retailer would withhold financing offers in such cases, as the consequent elevated wholesale price would adversely impact its own profit margin.

6. Numerical Analysis

In this section, the impacts of key parameters and changes in financing interest rates on different subsidy-based pledge financing strategies are explored through a numerical example, with further analysis of the economic and environmental performance of these financing strategies. First, conduct an investigation into the manufacturing practices of the new energy vehicle industry, collect data on its green R&D costs, production costs, and relevant subsidies, and perform normalization based on the characteristics of this data.

Then, with reference to the study by Zhang et al. [7] and Liu et al. [54], the parameters are set as follows: baseline market demand a = 50, unit production cost c = 1, Subsidy-based loan interest rate r = 0.04, ordinary bank loan interest rate rb = 0.08, wholesale price discount rate rt = 0.08, Green R&D cost coefficient k = 0.8, which satisfies the condition that . Moreover, based on various current R&D subsidy policies in China, the green R&D subsidy rate is set as s = 0.3, the subsidy pledge ratio σ = 0.6, and consumer green preference is considered neutral with δ = 0.5.

6.1. Sensitivity Analysis

Variations in key parameters significantly influence decision-making optimization and profit enhancement for supply chain members in green supply chains. This section analyzes the impacts of initial capital I, consumers’ green preference δ, and government subsidy parameters (s, σ) on supply chain decisions and profits.

6.1.1. The Impact of I on Decisions and Profits

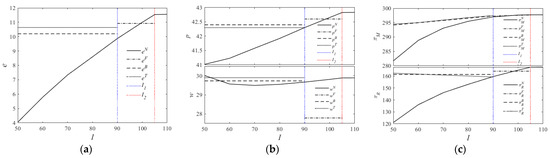

Figure 7 shows how decision variables and supply chain profits change with the manufacturer’s initial capital under different financing strategies.

Figure 7.

The impact of I on decisions and profits. (a) The impact of I on green degree; (b) The impact of I on prices; (c) The impact of I on profits.

The results demonstrate that the manufacturer’s capital level plays a crucial role in determining Strategy N’s decision variables, affects manufacturer profits across all strategies, and influences retailer profits specifically under Strategy T.

Under the no-financing scenario, the wholesale price demonstrates a distinct U-shaped relationship with the manufacturer’s initial capital, while all other decision variables and profits maintain positive correlations. An increase in initial capital leads to coordinated pricing adjustments between supply chain members, along with corresponding improvements in product greenness and profit levels. The profit growth trajectory exhibits characteristic diminishing marginal revenue. It begins with an initial phase of rapid acceleration when capital scarcity is acute. In this phase, each additional unit of funding significantly relieves production and R&D constraints. It is followed by progressively decelerating gains as capital adequacy improves and marginal utility decreases.

When the manufacturer opts for financing, the product’s greenness and pricing remain unaffected by initial capital variations under a given financing strategy, though its profitability still fluctuates. As evidenced in Figure 7c, for , Strategy N yields higher profits than Strategy F. This aligns with Proposition 4’s finding that no-financing becomes advantageous when the manufacturer’s funding gap is relatively small or financing rates are sufficiently high, since the marginal benefit of additional capital fails to offset the marginal cost of financing. Consequently, financing during capital shortages does not always guarantee improved profitability. When facing either low funding gaps or high interest rates, the manufacturer may achieve better returns by using existing capital directly to production and R&D activities, which is consistent with the conclusion drawn by Liu et al. [54].

6.1.2. The Impact of δ on Decisions and Profits

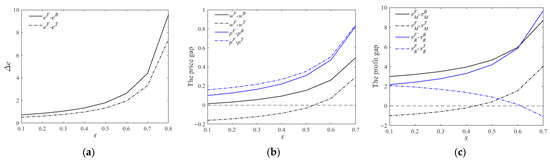

Building on the above analysis of initial capital, we assume for pure subsidy-based pledge financing and for hybrid financing. Numerical analysis of how consumer green preference δ affects decisions and profits under Strategies F, B and T yields the results shown in Figure 8. Regarding product greenness, Strategy F consistently maintains the highest level regardless of δ variations, followed by Strategy T, with Strategy B ranking lowest. Notably, as δ increases, Strategy T demonstrates a greater enhancement in product greenness compared to Strategy B, enabling the manufacturer to better capitalize on growing market demand for sustainable products.

Figure 8.

The impact of δ on decisions and profits. (a) The impact of δ on green degree; (b) The impact of δ on prices; (c) The impact of δ on profits.

Moreover, under Strategy T the manufacturer sets a higher wholesale price than under other strategies to compensate for wholesale discounts, while the retailer uses these discounts to lower retail prices and expand market share. This approach reduces the retailer’s profits when green preference is low, but when green preference is strong, the low-price strategy helps capture market demand and ultimately increases the retailer’s profits.

6.1.3. The Impact of Government Subsidies on Decisions and Profits

Due to the delayed disbursement characteristic of government subsidies, their impact on manufacturer’s decision-making under subsidy-based pledge financing is determined by the government subsidy rate s and the subsidy pledge ratio σ. The influence of these two parameters on different financing strategies is examined through numerical analysis.

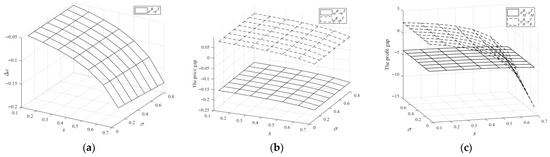

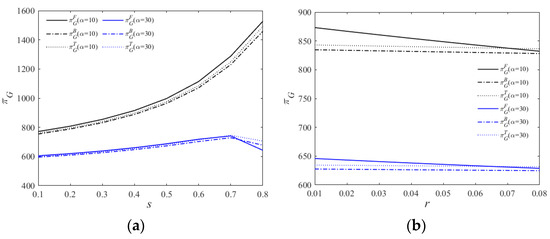

Obviously, an increase in the government subsidy rates means that the manufacturer can obtain a higher subsidy amount for the same green R&D investment. Even if the subsidy is delayed, the collateral funds available to manufacturers during the initial production phase will rise, helping to alleviate financial pressure. Figure 9 shows that the government subsidy rate influences the supply chain’s optimal decisions and profits in a manner analogous to consumers’ green preference, with increases in either factor stimulating green supply chain development.

Figure 9.

The impact of s on decisions and profits. (a) The impact of s on green degree; (b) The impact of s on prices; (c) The impact of s on profits.

Figure 10 shows that under the hybrid financing strategies, the optimal decisions and profits of supply chain members are jointly determined by the government subsidy rate and bank pledge rate, as these two factors directly influence the available subsidy financing amount. When the subsidy financing amount increases, Strategy T proves more effective than Strategy B in enhancing product greenness, while also leading to greater price increases for both manufacturer and retailer. Furthermore, under fixed interest rate conditions, the manufacturer consistently achieves higher profit with Strategy T regardless of subsidy financing fluctuations. The retailer also gains higher profits under Strategy T when subsidy financing reaches sufficient levels, making it more willing to provide financing to the manufacturer. Conversely, when subsidy financing remains limited, retailer experiences lower profits under Strategy T and consequently refuse to extend financing to the manufacturer.

Figure 10.

The combined impacts of s, σ on decisions and profits. (a) The combined impacts of s, σ on green degree; (b) The combined impacts of s, σ on prices; (c) The combined impacts of s, σ on profits.

The numerical results demonstrate that the manufacturer’s initial capital, consumers’ green preferences, and government subsidy rates collectively form key dimensions influencing supply chain financing and pricing strategies. For manufacturers with limited initial capital operating in markets with strong green preferences, government agencies may consider appropriately raising subsidy rates. As societal environmental awareness increases, the policy focus should shift from universal subsidies to establishing a market-driven green consumption mechanism, thereby maximizing the efficiency of policy resources.

6.2. The Financing Rate Analysis

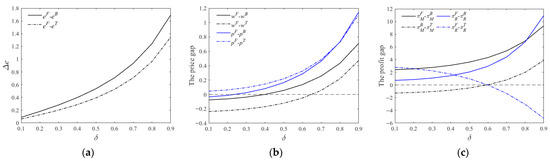

In supply chain financing decisions, interest rates serve as a critical determinant of financing costs, directly influencing operational choices and profits across supply chain entities. This section specifically examines how financing interest rates mechanistically affect different financing strategies.

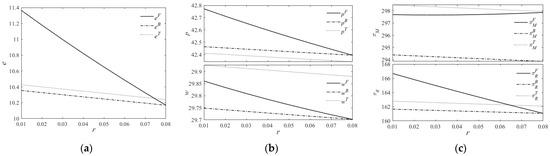

6.2.1. The Impact of r on Decisions and Profits

Figure 11 shows that changes in the pledge interest rate significantly affect product greenness and pricing under Strategy F while showing limited impact on hybrid financing, as risk diversification in hybrid financing means only first-stage costs vary with pledge interest rate. Rising pledge rate consistently reduces the product greenness level, prompting the retailer to implement price reductions to maintain market share, which consequently diminishes profits. The manufacturer mitigates cost pressures by implementing comparatively smaller wholesale price cuts than the retailer, creating profit imbalance that hinders financing agreement negotiations between supply chain partners.

Figure 11.

The impact of r on decisions and profits. (a) The impact of r on green degree; (b) The impact of r on prices; (c) The impact of r on profits.

6.2.2. The Impact of rb and rt on Financing Strategy Selection

Figure 12 demonstrates that when the bank loan interest rate and the wholesale price discount rate are unequal, the manufacturer and the retailer make different optimal choices under hybrid financing strategies. In Interval I, both parties achieve higher profits under Strategy T, creating a win-win situation that facilitates financing cooperation. Interval II shows a profit divergence where the manufacturer prefers Strategy T while the retailer favors Strategy B, leading to failed cooperation as the retailer refuses to provide financing, forcing the manufacturer to adopt Strategy B. In Interval III, both parties obtain maximum profits under Strategy B, making it the natural choice. These results indicate that the manufacturer selects Strategy T only in Interval I but defaults to Strategy B in Intervals II and III for hybrid financing.

Figure 12.

Optimal financing modes under different interest rates.

6.3. Consumer Surplus and Government Benefits Analysis

Consumer surplus is defined as the difference between consumers’ maximum willingness to pay for a given quantity of goods and the actual market price, expressed mathematically as (Chen et al. [9]). Furthermore, to achieve the central objective of sustainable development, the government must comprehensively evaluate multiple factors including social, economic and environmental dimensions. The government utility function in our study is formulated as , where α represents the marginal return rate of environmental improvement and S denotes the total subsidy value.

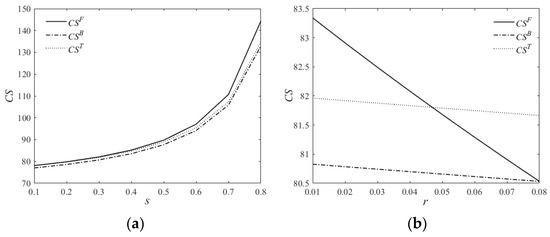

Figure 13 reveals that the government subsidy rate and the bank pledge interest rate exert opposing effects on consumer surplus. A higher green R&D subsidy rate expands consumer surplus, while an increased pledge interest rate negatively impacts it. This divergence occurs because a rising pledge rate elevates the manufacturer’s financing costs, prompting it to either raise prices or reduce product greenness to maintain profitability—both actions ultimately diminish consumer welfare by reducing the gap between willingness-to-pay and actual prices.

Figure 13.

The impacts of s and r on CS. (a) The impact of s on CS. (b) The impact of r on CS.

Figure 14 illustrates how the government subsidy rate and the subsidized pledge interest rate affect government benefits. When the marginal environmental improvement return α is high, increasing the subsidy rate consistently enhances government revenue. However, when α is low, the relationship follows an inverted U-shape—initial subsidy increases boost overall benefits until reaching a critical threshold, beyond which additional subsidies reduce returns. This occurs because excessive subsidies push product greenness near its technical ceiling, making marginal environmental gains insufficient to offset government expenditures. These findings suggest governments should carefully calibrate R&D subsidy rates to maximize value creation.

Figure 14.

The impacts of s and r on πG. (a) The impact of s on πG. (b) The impact of r on πG.

The analysis of consumer surplus and government benefits reveals that while pursuing environmental objectives through subsidy policies, the government also faces fiscal efficiency constraints. The inverted U-shaped relationship between the subsidy rate and government benefits provides a quantitative answer to a critical policy question: more subsidies are not always better. Based on this, policymakers can establish a dynamic adjustment mechanism for subsidy rates, linking them to indicators such as the maturity of green technologies and the market penetration rate of products. This ensures a balance between incentivizing innovation and avoiding the waste of fiscal resources, thereby achieving the multiple objectives of sustainable development.

7. Conclusions and Implications

This study investigates the operational decisions and financing strategy selection for a capital-constrained green manufacturer under a government subsidy pledge financing model. By establishing and comparing four financing scenarios (no financing, pure subsidy pledge financing, bank-hybrid financing, and retailer-hybrid financing), we systematically address the three research questions posed in the introduction. The main findings, corresponding managerial implications, and future research directions are summarized as follows.

7.1. Conclusions

The main conclusions of the study can be summarized as follows:

Regarding how subsidy-based pledge financing influences production decisions, we find that the manufacturer’s financing pressure significantly shapes optimal product greenness and pricing strategies. Under relatively low or high financing pressure, the supply chain tends to increase product greenness and raise wholesale/retail prices to capture green premiums, thereby enhancing profitability. In contrast, under moderate financing pressure, reducing both greenness and prices proves more effective for maintaining sales volume and profit margins.

Concerning the choice of financing strategies under varying conditions, the manufacturer’s optimal financing strategy is determined by its initial capital level and the comparative costs of different financing channels. When the funding gap is small, but the subsidy pledge interest rate is high, relying solely on internal capital (no financing) may yield higher profits than seeking external funding. Pure subsidy pledge financing (Strategy F) is preferred when the funding gap is small with a low pledge rate or when the gap is large, but the cost of alternative financing is prohibitively high. Hybrid financing becomes optimal only when the funding gap is substantial and the second-stage financing cost is sufficiently low. Within hybrid financing, the choice between bank (Strategy B) and retailer financing (Strategy T) depends on specific interest rate intervals, underscoring that excessively high financing costs can deter manufacturers from effectively utilizing external funds.

With respect to the impact of subsidy pledge financing on consumer surplus and government benefits, our results reveal a dual effect. While an increase in the R&D subsidy rate consistently improves supply chain profits and consumer surplus, its effect on overall government benefits is not monotonic. When the marginal return on environmental improvement is below a certain threshold, government benefits exhibit an inverted U-shaped relationship with the subsidy rate, indicating an optimal level beyond which additional subsidies reduce net social welfare due to diminishing marginal gains relative to fiscal expenditures.

7.2. Managerial Implications

The findings offer actionable insights for supply chain members and policymakers.

The results provide a clear decision-making framework. Manufacturers should first conduct a precise assessment of their capital gap. If external financing is necessary, priority should be given to the low-cost subsidy pledge financing channel. When this is insufficient, a meticulous comparison of the effective costs of bank loans versus retailer advance payments is crucial. Furthermore, manufacturers should recognize that improving R&D efficiency (lower k) is vital, as it not only reduces the financial burden of green transformation but also provides greater flexibility in pricing and bargaining within the supply chain, ultimately enhancing profitability under different financing modes.

To maximize the effectiveness of subsidy pledge financing, policymakers should focus on several key areas. First, establishing a standardized, transparent, and efficient certification process for Uncollected Financial Subsidy Receivables (UFSRs) is essential to reduce transaction costs and risks for banks, encouraging them to offer more favorable pledge rates (r). Second, rather than universally increasing subsidy amounts, calibrating subsidy rates to align with the marginal environmental benefits is critical for avoiding diminishing returns on public investment. This model should be positioned as a complementary tool to address cash-flow issues caused by subsidy delays, particularly in sectors with large, verifiable subsidies like renewable energy. Finally, policymakers must account for the administrative costs of implementing such programs, ensuring they are cost-effective.

7.3. Future Work

This study has several limitations that delineate the boundaries of its applicability while simultaneously pointing toward promising directions for future research.

First, this study employs a single-period static model, which could be extended to a multi-period dynamic framework to trace the evolution of financing strategies over time. Second, the model assumes perfect information and risk neutrality, whereas future work could incorporate information asymmetry and risk aversion to better reflect real-world conditions. Third, while the model is contextualized in green manufacturing, its core logic—financing against delayed and uncertain future income—applies to other sectors like green agriculture and new energy vehicles, offering broad generalizability. Finally, incorporating demand uncertainty into the financing decision process presents another valuable direction for further research.

By addressing these limitations, future research can deepen the understanding of financing strategies for green supply chains and provide more precise guidance for practitioners and policymakers.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, R.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71871017) and the Social Science Planning Fund of Liaoning Province, China (No. L24CGL026).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article. (All data used in our study are presented within the manuscript itself, specifically in Section 6. Numerical Analysis. Furthermore, all necessary reference sources for the data have been provided there).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

The expressions of the threshold value can be found in Table A1.

Table A1.

Threshold Expression.

Table A1.

Threshold Expression.

| Situation | Expression |

|---|---|

| Benchmark Model | , , . |

| Corollary 2 | , . |

| Corollary 4 | , , . |

| Proposition 4 | , , , . , , , . |

| Proposition 6 | , , , , , , , . |

| Proposition 7 | . |

Appendix B

Proof of the Benchmark Model.

The solution is derived by applying the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker (KKT) optimality conditions. The first-order partial derivatives of with respect to w and e are and , respectively. The complementary slackness condition is .

The backward induction method is employed: first, the retailer makes the pricing decision. Following a similar process, we obtain . Substituting this into the Lagrangian function, the second-order partial derivatives of with respect to w and e are derived, yielding the Hessian matrix . When , the Hessian is negative definite, indicating the existence of a unique optimal solution.

By solving the system of equations formed by , , and , we obtain the optimal values wS and eS. Substituting these into gives pS, from which we further derive DS, and . □

Proofs of Propositions 1–3 are similar to the proof of the Benchmark Model.

Proof of Corollary 1.

- (i)

- When , we have , , . And when , the proof follows a similar procedure.

- (ii)

- Since , we have , .□

Proof of Corollary 2.

- (i)

- , when , , so , ; when , , so . And when , .

- (ii)

- , let the numerator be greater than 0, we have . is similar to the proof of .

- (iii)

- , when , ; otherwise, .

- (iv)

- When , we have , so , ; otherwise, the proof follows a similar procedure.□

Proof of Corollary 3.

It is similar to the Proof of Corollary 1. □

Proof of Corollary 4.

It follows a similar procedure to Corollary 2. □

Proof of Corollary 5.

- (i)

- , , , , .

- (ii)

- Since , , ,,. Let , we have , otherwise, the proof follows a similar procedure.□

Proof of Corollary 6.

It follows a similar procedure to Corollary 5. □

Proof of Corollary 4.

Let , we have , similarly for the others. □

Proofs of Propositions 5–7 are similar to the proof of the Proposition 4.

References

- Ru, X.; Si, F.; Lei, P. Research on the impact of environmental regulation on enterprise high-quality development. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 96, 103537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YiMagazine. China Consumer Insights: Uncovering 5 Major Buying Trends. Available online: http://www.sydcch.com/shangyedichan/lingshoudichan/2022/0921/8265.html (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, J.; Hu, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, S.; Pang, C. Advances and Industrialization of LiFePO4 Cathodes in Electric Vehicles: Challenges, Innovations, and Future Directions. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 17271–17283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Bu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, J.; Xue, Q.; Wang, J.; Zuo, H. The Low-Carbon Production of Iron and Steel Industry Transition Process in China. Steel Res. Int. 2024, 95, 2300500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, J.K.; Breske, S.; Singstock, N.R. Hydrogen-Powered Vehicles for Autonomous Ride-Hailing Fleets. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 9422–9427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]