Innovation in Disaster Education for Kindergarten: The Bousai Terakoya Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What influences the innovation of disaster education programs for the kindergarten level in Japan?

- What are the challenges in innovating disaster education programs for kindergarten students?

- How do these influences contribute to developing disaster education programs for kindergarten students?

- To determine the key drivers in innovating disaster education programs in the kindergarten.

- To identify challenges and gaps in implementing innovation in disaster education programs for kindergarten.

- To evaluate the effectiveness of disaster education programs in fostering disaster awareness among kindergarten students.

- To formulate strategies for enhancing disaster education programs, with a focus on the kindergarten level.

Innovation in Disaster Education for Early Childhood

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Field Observation

2.2.2. Assessment Tool

2.2.3. Survey Questionnaire

2.2.4. Key Informant Interview

2.3. Data Analysis

- Analyze the innovation strategies to conceptualize the innovation concepts found in the research papers related to disaster education, particularly in early childhood education.

- The concepts that emerged were used to determine the central themes to be included in the construction of the survey questionnaire and interview.

- Analyze students’ drawings to understand their insight into the topics learned in the picture books.

- The research employs semiotic methods to examine how kindergarten students use symbol repetition in their drawings and paintings [43]. Such repetitions can suggest scale and importance, contributing to a layered, metaphorical, and symbolic dimension. This approach reveals the students’ comprehension of disaster-related ideas.

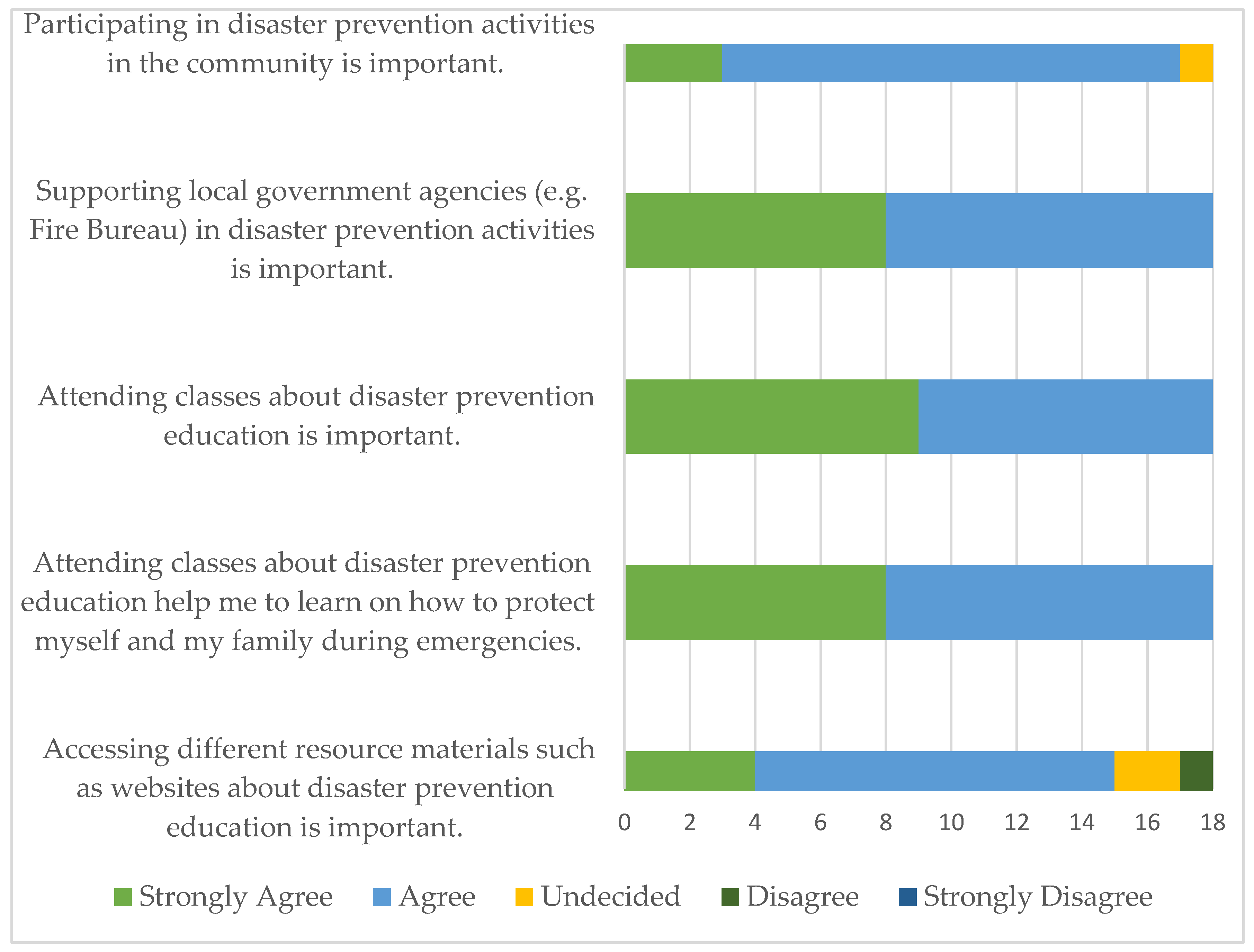

- Interpret the survey questionnaire (Appendix A) results to gain insights into parents’ perspectives on disaster education and Bousai Terakoya.

- The quantitative data, collected through a structured questionnaire with Likert-scale items, were analyzed using Microsoft Excel. Responses were manually entered into Google Forms for easy access and then transferred to an Excel spreadsheet. The data were first organized and cleaned to ensure accuracy and completeness. Descriptive statistics, especially frequencies and percentages, were calculated to summarize overall response trends. Next, the variables were examined and linked to the emerging themes identified in the literature review to reveal their relationships. Microsoft Excel was chosen for its accessibility, functionality, and ability to effectively handle the scope and scale of the dataset. It also allowed for the creation of visual representations, supporting the interpretation of key findings. Although Excel has limitations in advanced statistical modeling, it was sufficient for the descriptive analyses required in this study, given the small number of respondents.

- Organize and analyze the key informant interviews from the 6 participants who are the main organizers of Bousai Terakoya.

- The interview was conducted in Japanese and then translated into English. Transcripts were manually coded to identify themes using the six-phase thematic analysis [44]. After transcription, the data were read multiple times to ensure a thorough understanding. Initial codes were created by highlighting important words, phrases, and patterns. These codes were then grouped into broader themes that reflected recurring ideas related to the research questions. Themes were reviewed, refined, and clearly defined to ensure clarity and distinctness. The analysis aimed to capture both explicit content and underlying meanings. Microsoft Word and Excel were used for coding and organizing data, chosen for their flexibility and ability to support participants’ experiences.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Case Study: Bousai Terakoya

2.6. The Birth of Bousai Terakoya

3. Results

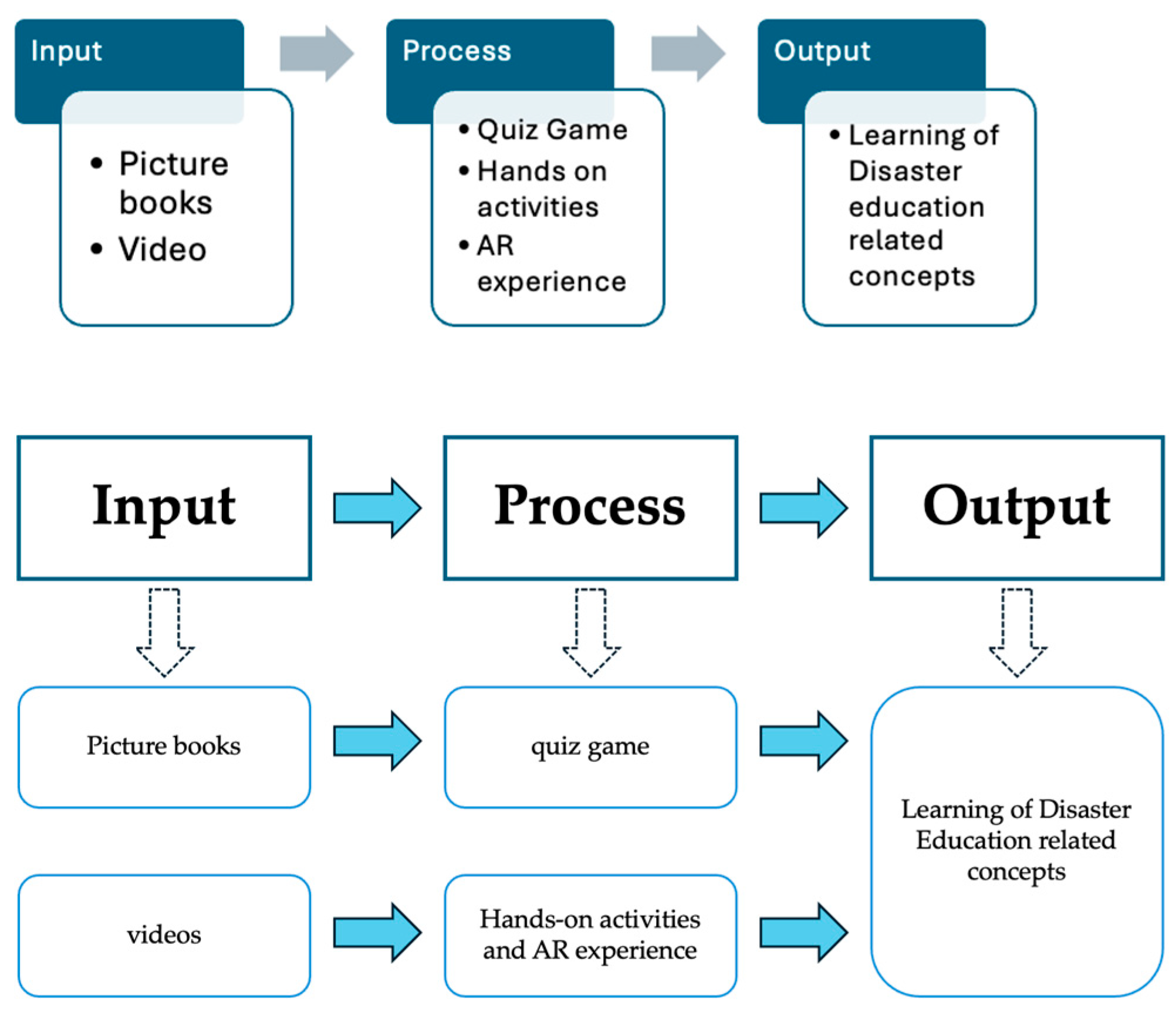

3.1. Overview of Bousai Terakoya

3.2. Child’s Experience in Assessment Tool

3.3. The Management of Bousai Terakoya

3.4. Key Lessons of Bousai Terakoya

3.5. Key Challenges of Bousai Terakoya

3.6. The Future Directions of Bousai Terakoya

3.7. The Learning Outcomes of Bousai Terakoya

3.8. Improvements to Bousai Terakoya

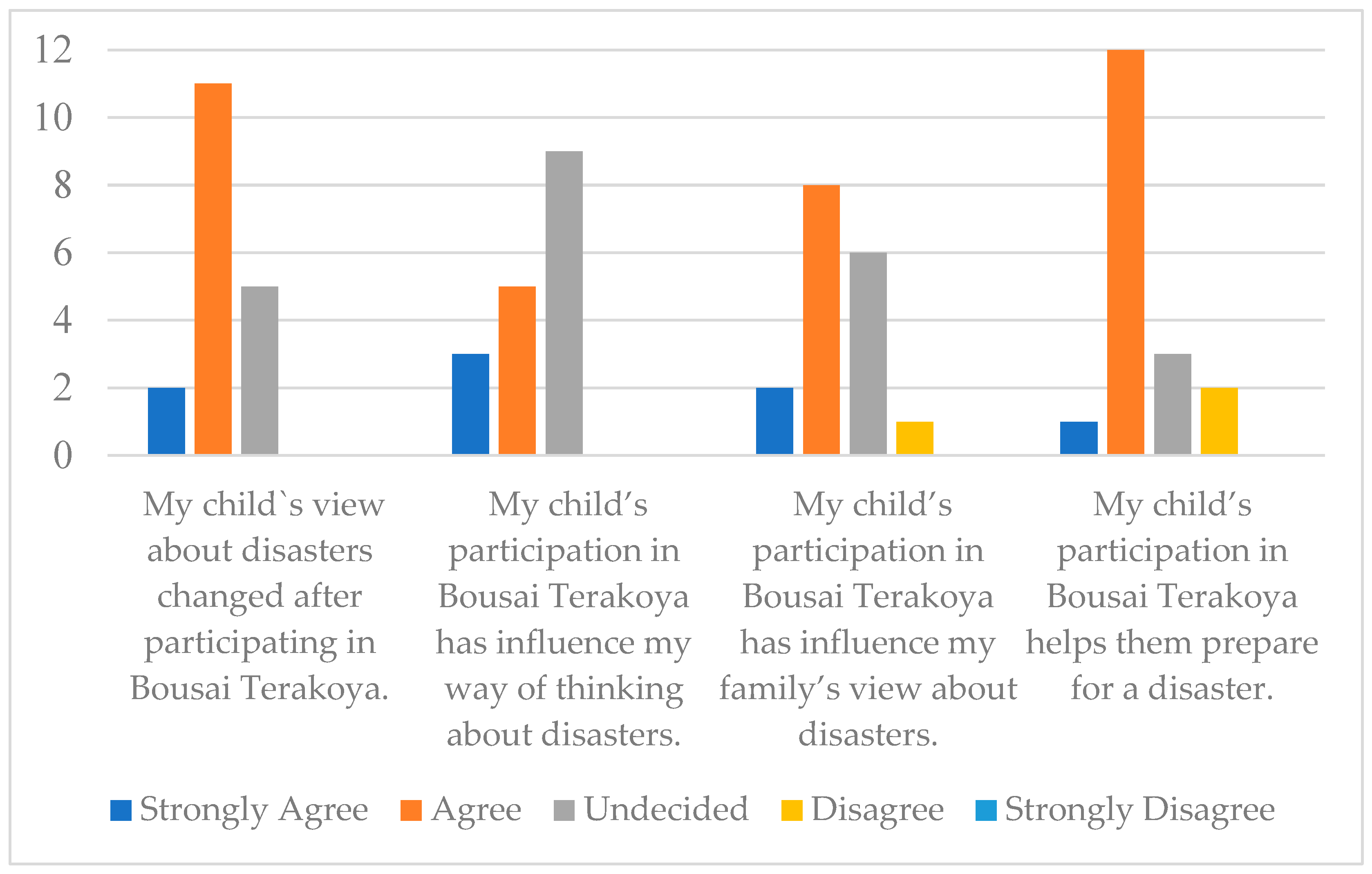

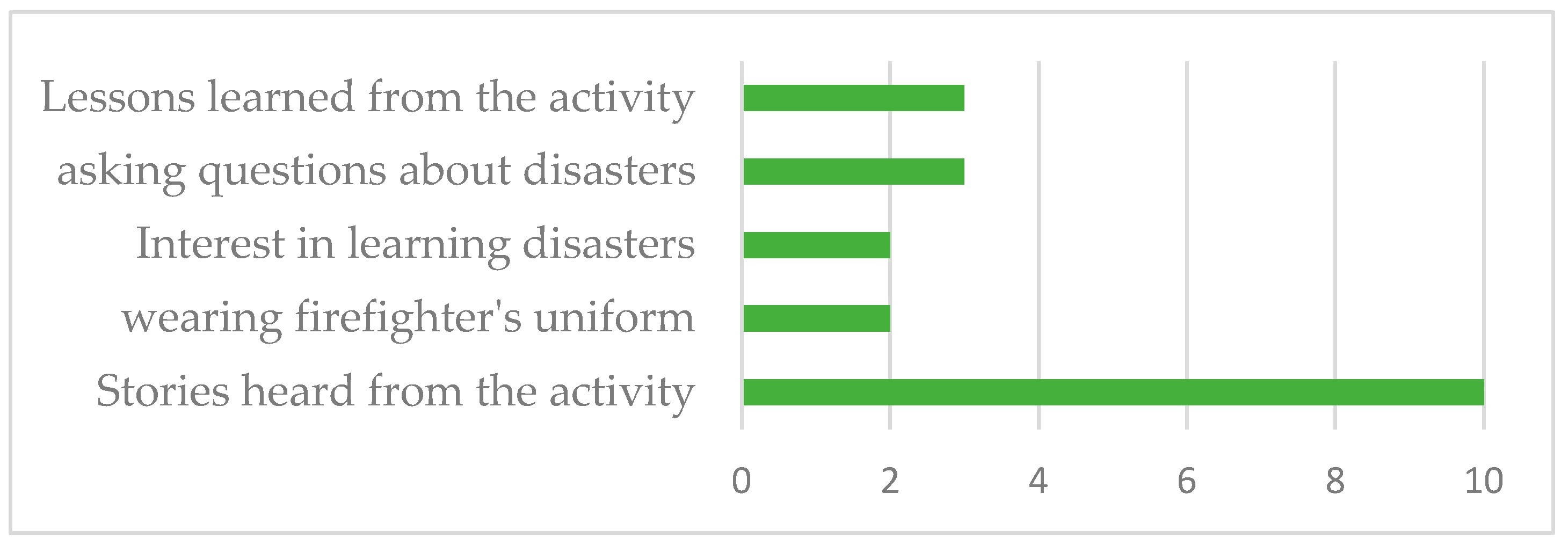

3.9. Parents’ and Caretakers’ Insights About Bousai Terakoya

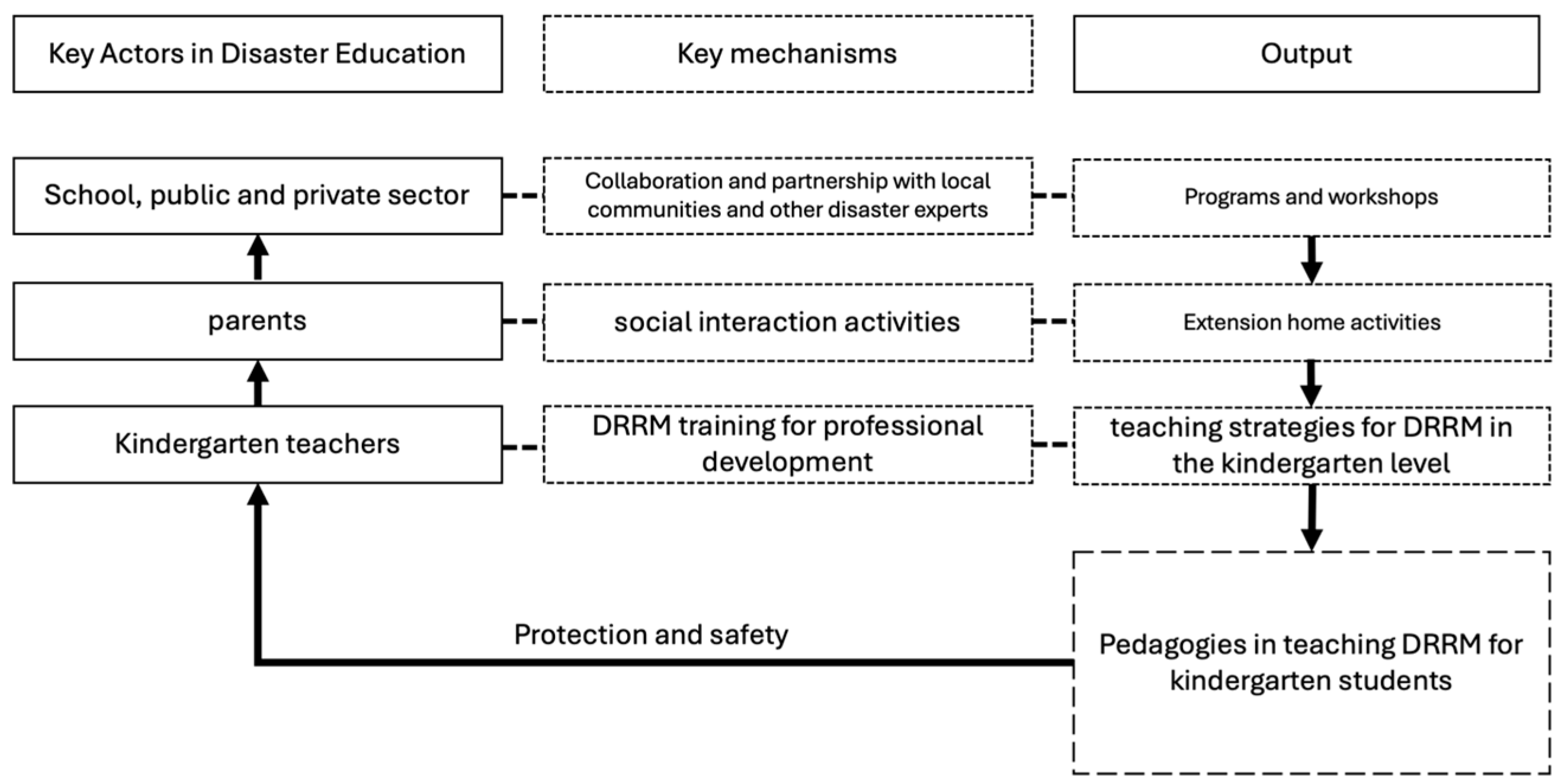

4. Discussions

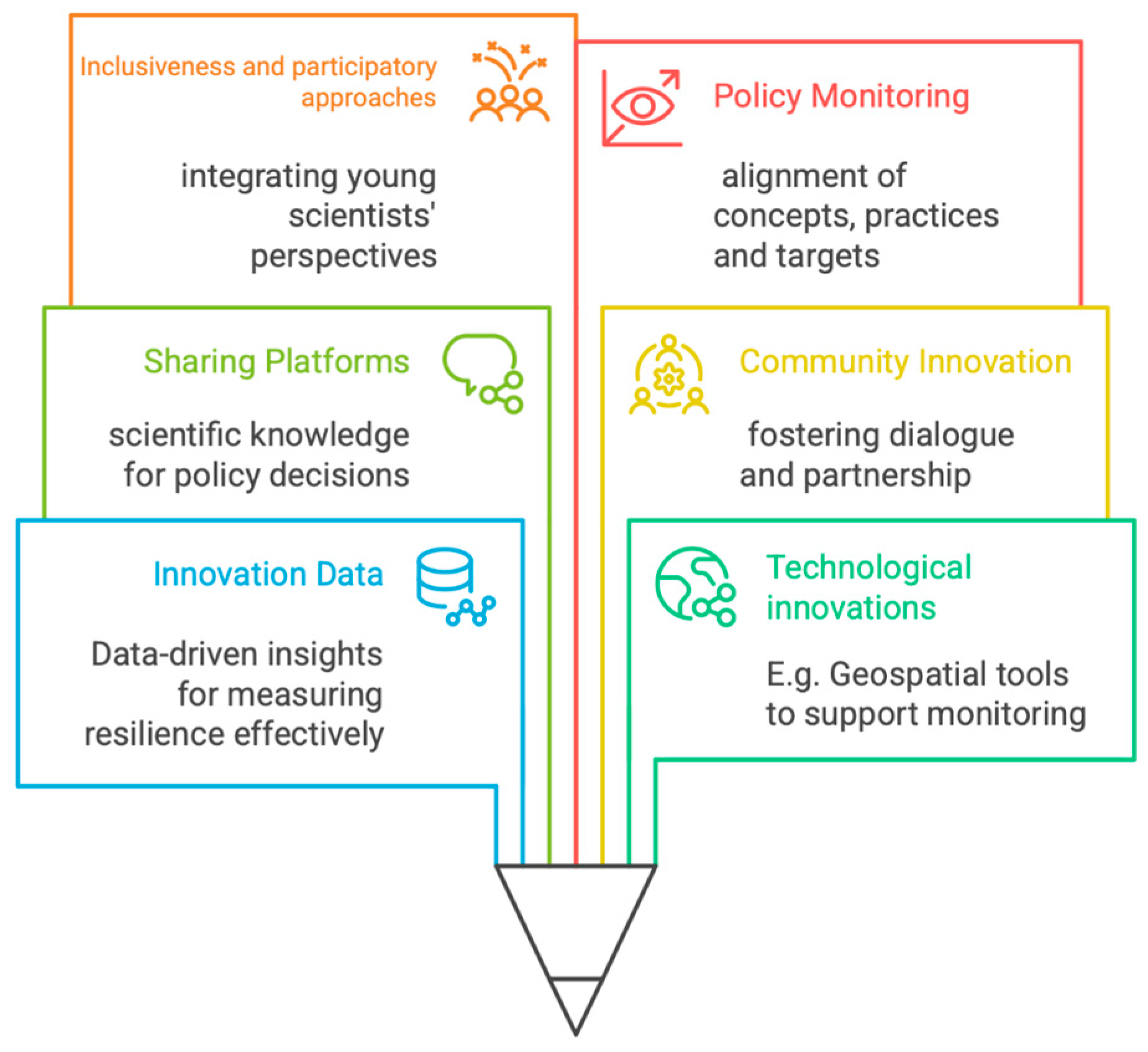

4.1. Key Drivers Driving Innovation in Disaster Education Programs

4.1.1. External Circumstances

4.1.2. Logistical and Human Resources

4.1.3. Community Engagement

4.2. Barriers to Innovating Disaster Education Programs

4.3. Contributing Drivers to the Development of Disaster Education

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Survey Questionnaire (English)

- I.

- Please shade the (

) for your answer.

| Which of the following best describes your gender? |

|

| What is your age? |

|

| Work status |

|

- II.

- Indicate how strongly you agree or disagree with each statement by placing a circle (

) in the space provided. Please complete every item.

| Statements | Strongly Agree | Agree | Undecided | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

| 1. Participating in disaster prevention activities in the community is important. | |||||

| 2. Supporting local government agencies (e.g., Fire Bureau) in disaster prevention activities is important. | |||||

| 3. Attending classes about disaster prevention education is important. | |||||

| 4. Attending classes about disaster prevention education help me to learn how to protect myself and my family during emergencies. | |||||

| 5. Accessing different resource materials about disaster prevention education is important. | |||||

| 6. My child’s view about disasters changed after he participated in Bousai Terakoya. | |||||

| 7. My child’s participation in Bousai Terakoya affects my views about disasters. | |||||

| 8. My child’s participation in Bousai Terakoya affects our family’s view about disasters. | |||||

| 9. My child’s participation in Bousai Terakoya improves my understanding about disasters. | |||||

| 10. My child’s participation in Bousai Terakoya improves our family’s understanding about disasters. | |||||

| 11. My child’s participation in Bousai Terakoya helps me to prepare for disasters. |

- III.

- Please shade the (

) for your answer.

| 1. How many times has your child attended the Bousai Terakoya activity? |

|

| 2. Does your child talks about his experience in the Bousai Terakoya at home? |

|

| 3. If your answer is Yes in number 2, which of the following best describes your child’s experience participating in Bousai Terakoya? |

|

| 4. Does your child talks about the lessons he learned in the Bousai Terakoya at home? |

|

| 5. If you answer yes to number 4, which of the following best describe the lesson your child learned in Bousai Terakoya? |

|

| 6. Has your family’s view towards disasters changed after your child participated in Bousai Terakoya? |

|

| 7. If you answer yes to number 6, which of the following best describe your family’s view towards disaster? |

|

| 8. Has your family’s action towards disasters changed after your child participated in Bousai Terakoya? |

|

| 9. If you answer yes to number 8, which of the following action best applies to your family? |

|

- IV.

- Please write your thoughts on the following questions.

- 1.

- Are there any topics about disaster prevention education that you wish your child could learn while attending Bousai Terakoya?________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- 2.

- Please write down your suggestions to improve the implementation of Bousai Terakoya.________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

References

- UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2024: The Future of Childhood in a Changing World; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/165156/file/SOWC-2024-full-report-EN.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- UNDRR. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Seddighi, H.; Yousefzadeh, S.; López López, M.; Sajjadi, H. Preparing Children for Climate-Related Disasters. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2020, 4, e000833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, A. Raising Awareness of Disaster and Giving Disaster Education to Children in Preschool Education Period. Acta Educ. Gen. 2020, 10, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Nurturing Care for Early Childhood Development in Support of Children’s Health and Well-Being; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/272603/9789241514064-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- UNESCO. Regional Report for Asia-Pacific, Education Starts Early, Progress, Challenges and Opportunities; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabinet Office. White Paper on Disaster Management 2023; Cabinet Office: Tokyo, Japan, 2023. Available online: https://www.bousai.go.jp/en/documentation/white_paper/2023.html (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Chinoi, T. Disaster Education in Japan. In Disaster Education; BRI & GRIPS: Tokyo, Japan, 2007; pp. 50–66. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/3442_DisasterEducation.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Sakurai, A.; Sato, T. Promoting Education for Disaster Resilience and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. J. Disaster Res. 2016, 11, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, M.; Shaw, R. The Potential of Digitally Enabled Disaster Education for Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Early Childhood Development and Climate Change: Advocacy Brief; UNICEF East Asia and Pacific: Bangkok, Thailand, 2022; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eap/media/12801/file (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). The National Curriculum Standard for Kindergartens: Contents; MEXT: Tokyo, Japan, 2017. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/component/a_menu/education/detail/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2019/10/11/1401777_002.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- UNDRR. Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters; United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Available online: https://www.unisdr.org/files/1037_hyogoframeworkforactionenglish.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Scolobig, A.; Balsiger, J. Emerging Trends in Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation Higher Education. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 105, 104383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, T.; Shaw, R.; Djalante, R.; Ishiwatari, M.; Komino, T. Disaster Risk Reduction and Innovations. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2019, 2, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaad, D.; Franzoni, L.; Paul, C.; Bauer, A.; Morgan, K. A Perfect Storm: Examining Natural Disasters by Combining Traditional Teaching Methods with Service Learning and Innovative Technology. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2008, 24, 450–465. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, S.K.; Seavey, J.R.; Mueller, R.C. Integrated Science and Art Education for Creative Climate Change Communication. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabilao-Valencia, M.I.; Ali, M.; Maryani, E.; Supriatna, N. Integration of Disaster Risk Reduction in the Curriculum of Philippine Educational Institution. In Proceedings of the 3rd Asian Education Symposium (AES 2018), 2019; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2019; pp. 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarmi; Bachri, S.; Irawan, L.Y.; Aliman, M. E-Module in Blended Learning: Its Impact on Students’ Disaster Preparedness and Innovation in Developing Learning Media. Int. J. Instr. 2021, 14, 187–208. Available online: https://scispace.com/pdf/e-module-in-blended-learning-its-impact-on-students-disaster-52mw5g4b30.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kagawa, F.; Selby, D.; UNICEF. Disaster Risk Reduction in School Curricula: Case Studies from Thirty Countries; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2012; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000217036 (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Toyoda, Y. A Framework of Simulation and Gaming for Enhancing Community Resilience against Large Scale Earthquakes: Application for Achievements in Japan. Simul. Gaming 2020, 51, 180–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Yamauchi, H.; Oguchi, T.; Ogura, T. Application of Web Hazard Maps to High School Education for Disaster Risk Reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 72, 102866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, T.; Yi, T.Y.; Kimura, R.; Ikeda, M. Development of the Volcanic Disaster Risk Reduction Education Program Using the ICT Tool “YOU@RISK Volcanic Disaster Edition”—Practical Verification at a Junior High School in the Mt. Nasu Area—J. Disaster Res. 2024, 19, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, M.; Nagata, T.; Kimura, R.; Yi, T.Y.; Suzuki, S.; Nagamatsu, S.; Oda, T.; Endo, S.; Hatakeyama, M.; Yoshikawa, S.; et al. Development of Disaster Management Education Program to Enhance Disaster Response Capabilities of Schoolchildren during Heavy Rainfall—Implementation at Elementary School in Nagaoka City, Niigata Prefecture, a Disaster-Stricken Area. J. Disaster Res. 2021, 16, 1121–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, T.; Kimura, R. Developing a Disaster Management Education and Training Program for Children with Intellectual Disabilities to Improve “Zest for Life” in the Event of a Disaster: A Case Study on Tochigi Prefectural Imaichi Special School for the Intellectually Disabled. J. Disaster Res. 2020, 15, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouchi, R.; Sato, S.; Imamura, F. Disaster Education for Elementary School Students Using Disaster Prevention Pocket Notebooks and Quizzes. J. Disaster Res. 2015, 10, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kido, K.; Nakaya, F.; Katagiri, M. A Play-Based Disaster Preparation Program: Exploring the Sustenance of the Learning Effect. Inf. Technol. Educ. Learn. 2022, 2, Trans-p007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chubachi, N.; Konno, K.; Fukushima, Y.; Sato, T. “What If the Nankai Trough Earthquake Occurred?”: A Collaboration Between Academia with the Media Using a Newspaper-Making Workshop as a Starting Point to Engage Elementary School Students and Their Parents in Disaster Risk Reduction. J. Disaster Res. 2023, 18, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghri, Z. Climate Change, An Unwelcome Legacy: The Need to Support Children’s Rights to Participate in Global Conversations. Child. Youth Environ. 2018, 28, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppel, O.C.; Roschmann, C.; Ruppel-Schlichting, K. (Eds.) Climate Change: International Law and Global Governance, Volume I: Legal Responses and Global Responsibility, 1st ed.; Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2013; Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv941w8s (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Hanna, R.; Oliva, P. Implications of Climate Change for Children in Developing Countries. Future Child. 2016, 26, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparri, G.; El Omrani, O.; Hinton, R.; Imbago, D.; Lakhani, H.; Mohan, A.; Yeung, W.; Bustreo, F. Children, Adolescents, and Youth Pioneering a Human Rights-Based Approach to Climate Change. Health Hum. Rights 2021, 23, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Lu, W. Research on Kindergarten Children Evacuation: Analysis of Characteristics of the Movement Behaviours on Stairway. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N.; Imai-Matsumura, K. Executive Function Training for Kindergarteners after the Great East Japan Earthquake: Intervention Effects. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2023, 38, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maphosa, V.; Dube, B. Local Language Numeracy Kindergarten Prototype Design to Support Home-Based Learning during and Post Covid-19 Pandemic. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2021, 13, ep301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.E.; Valenzuela, I.C.; Abulon, E.R.; Arago, N.M.; Mancao, M.T. Coupling School Risk Reduction Strategies with LAMESA (Life-Saving Automated “Mesa” to Endure Seismic Activity) for Kindergarten. Philipp. J. Sci. 2019, 148, 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Tolentino, M.A.; Vergara, H.P.; Albor, R.G.Z.; Dy, M.F.R.; Sanchez, R.D.; Bulasag, A.S.; Pelegrina, D.V. Storytelling: A Disaster Awareness Tool among Kindergarten Pupils. J. Hum. Ecol. 2017, 6, 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Maulida, A.; Hanif, H.; Kamal, M.; Oktari, R.S. Roblox-Based Tsunami Survival Game: A Tool to Stimulate Early Childhood Disaster Preparedness Skills. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2023; Volume 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahiem, M.D.H.; Rahim, H. The Dragon, the Knight and the Princess: Folklore in Early Childhood Disaster Education. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2020, 19, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, D.J.K. Storytelling to Develop Resilience in Early Childhood in Facing Earthquake Disasters. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Current Issues in Education (ICCIE 2023), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 10–11 November 2023; pp. 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Leavy, P. Research Design: Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, Arts-Based, and Community-Based Participatory Research Approaches; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Deguara, J. Young Children’s Drawings: A Methodological Tool for Data Analysis. J. Early Child. Res. 2019, 17, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokohama City Visitors Bureau. Yokohamabashi Shopping District. Available online: https://www.yokohamajapan.com/things-to-do/detail.php?id=177 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- City of Yokohama. Public Relations Yokohama Minami Ward Edition: Disaster Prevention Special Collection, 11 March 2025. Available online: https://www.city.yokohama.lg.jp.e.sj.hp.transer.com/minami/bosai_bohan/saigai/minami-bousai.html (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- City of Yokohama. Disaster Prevention and Emergency Information, 25 September 2024. Available online: https://www.city.yokohama.lg.jp/naka/naka-lang/en/emergency/bousai.html (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Proulx, K.; Aboud, F. Disaster Risk Reduction in Early Childhood Education: Effects on Preschool Quality and Child Outcomes. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2019, 66, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamaong, M.T.P.; Yildiz, A.; Shaw, R. Evolution of Disaster Education in the Schools: The Experience of Asia and the Pacific Region. In Two Decades from the Indian Ocean Tsunami; Shaw, R., Izumi, T., Djalante, R., Imamura, F., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenouchi, K.; Kawata, Y.; Tanimoto, R. Long-Term Evaluation of Disaster Education: From a Survey Across Age Groups. J. Integr. Disaster Risk Manag. 2023, 12, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggs, G.L.; Wilson, N.S.; Ackland, R.T.; Danna, S.; Grant, K.B. Beyond the Lorax: Examining Children’s Books on Climate Change. Read. Teach. 2016, 69, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itamiya, T. Visualization of Simulation Results Using VR/AR and Learning through Its Experience: Applications to Disaster Risk Reduction Education. J. Jpn. Soc. Clin. Anesth. 2021, 41, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, W.; Utama, I.; Wardani, R.; Hapidin. Study Mitigation Disaster for Early Childhood in Indonesia: A Systematic Literature Review. Evol. Stud. Imagin. Cult. 2024, 8, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, K. Conceptualising ‘Disaster Education’. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, G.; Thompson, J. Children and Young People’s Perspectives on Disasters—Mental Health, Agency and Vulnerability: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 108, 104495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author and Date | Country | Output | Type of Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yao & Lu, 2020 [33] | China | Evacuation Drills (Movement behavior) | Community innovation (approach)and innovation of data (method) |

| Yamamoto & Imai-Matsumura, 2023 [34] | Japan | Executive Function intervention program | Approach |

| Maphosa & Dube, 2021 [35] | Zimbabwe | Numeracy-based App (prototype) | Technological innovation (product) |

| Morales et al., 2019 [36] | Philippines | LAMESA (Life Saving Automated “MESA” to Endure Seismic Activity) (prototype) | Technological innovation (product and approach) |

| Tolentino et. al., 2020 [37] | Philippines | Storytelling (Narrative Story Stem Technique) | Approach |

| Maulida et al., 2023 [38] | Indonesia | Roblox (Tsunami Survival Game) | Technological innovation (product) |

| Rahiem & Rahim, 2024 [39] | Indonesia | folklore | Community innovation (approach) and technological innovation (product) |

| Dewi, 2024 [40] | Indonesia | storybook | product |

| Date | Venue | Topic | Attendees |

|---|---|---|---|

| 02/21/2024 | Yokohamabashi Shopping District | Earthquake | 18 |

| 07/09/2024 | Shirobara Nursery School | Typhoon | 19 |

| 11/28/2024 | Yokohamabashi Shopping District | Emergency care | 18 |

| 02/13/2025 | Yokohama City Minami Library | Fire | 12 |

| No of participants | 67 | ||

| Book Title in Japanese | Book Title in English | Synopsis |

|---|---|---|

| みんな森の仲間とオオカミのサイレン~君には優しさという強さがある~ | Everyone’s Friends in the Forest and the Wolf’s Siren | A wolf’s reckless fire causes destruction, but teamwork and courage help extinguish the flames. Captain Panda of the Fire Brigade teaches the wolf that true strength lies in kindness and valuing friends. |

| みんな森の子どもたちとヤギおじさん~君のやさしさが、明日を生きる希望になる | All the Children of the Forest and Uncle Goat | After losing his family, Uncle Goat isolates himself. An earthquake and a tsunami prompted the forest’s children to rescue him with the help of the fire brigade. Their kindness encourages him to read stories and reconnect with others. |

| みんな森の子供たちとアウル爺さん~みんなの命を救ったのは、小さな勇気でた | All the Children of the Forest and Grandpa Owl | Riccio, a fearful and weak young hedgehog, takes a brave action on the night of a big storm. He recalls a critical teaching he heard from Grandpa Owl. Grandpa Owl’s teaching and Riccio’s bravery were able to save everyone in the forest, highlighting the importance of learning from past disasters. |

| Item | No of Students |

|---|---|

| PET bottle | 4 |

| band aid | 4 |

| flashlight | 3 |

| chips | 1 |

| first aid kit | 1 |

| teddy bear | 1 |

| Institution | Management of Bousai Terakoya | Key Lessons from Bousai Terakoya | Challenges | Future Directions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yokohama Fire Bureau | Performs Administrative function and session logistics | Resource utilization and community engagement | Manpower limitation (expert pool) and limited space | Improve teaching method and coordination |

| NOGE Printing Inc. | Oversees creative aspects and produces session material | Societal contribution and local engagement | Manpower limitation; reputation concerns | Digitize content and explore more stories about disaster scenarios |

| Kindergarten school | Reviews session content and escorts students to location site | Diverse learning sources and local community exploration | Child safety, and teaching approach (adult-like) | Suggest more meeting for feedback and improvement |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pamaong, M.T.P.; Shaw, R. Innovation in Disaster Education for Kindergarten: The Bousai Terakoya Experience. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9527. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219527

Pamaong MTP, Shaw R. Innovation in Disaster Education for Kindergarten: The Bousai Terakoya Experience. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9527. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219527

Chicago/Turabian StylePamaong, Ma. Theresa P., and Rajib Shaw. 2025. "Innovation in Disaster Education for Kindergarten: The Bousai Terakoya Experience" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9527. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219527

APA StylePamaong, M. T. P., & Shaw, R. (2025). Innovation in Disaster Education for Kindergarten: The Bousai Terakoya Experience. Sustainability, 17(21), 9527. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219527