Abstract

The global transition to renewable energy requires hybrid solutions that address variability while delivering tangible co-benefits and verifiable mitigation outcomes. This study evaluates a novel small hydropower–photovoltaic (SHP–PV) hybrid system in the Kyrgyz Republic that integrates flexible Bitcoin mining loads and waste-heat recovery for greenhouse heating. A techno-economic model was developed for a 10 MW configuration, allocating annual net generation of 57.34 GWh between grid export and on-site mining through a single decision parameter. Mitigation accounting applies a combined margin grid factor of 0.4–0.7 tCO2/MWh for exported electricity and a diesel factor of 0.26–0.27 tCO2/MWh_fuel for heat displacement, yielding Article 6–eligible reductions from both electricity and recovered heat. Waste-heat recovery from mining supplies ≈15 MWh_th/year to a 50 m2 greenhouse, displacing diesel use and demonstrating visible sustainable development co-benefits. Economic analysis reproduces annual revenues of ≈$1.9 million, with a levelized cost of electricity of $48/MWh and an indicative IRR of ~6%, consistent with positive but modest returns under merchant operation and uplift potential under mixed allocations. This study concludes that componentized accounting—exported electricity credited under grid displacement and diesel displacement credited from recovered heat—ensures Article 6 integrity and positions SHP–PV hybrids as replicable, multi-service renewable models for Central Asia. Unlike prior hybrid studies that treat generation, economics, and mitigation separately, our framework integrates allocation (α), financial outcomes, and Article 6 carbon accounting within a unified structure, while explicitly modeling Bitcoin mining as an endogenous flexible load with thermal recovery—advancing methodological approaches for multi-service renewable systems in climate policy contexts.

1. Introduction

Hybrid small hydropower (SHP)–photovoltaic (PV) systems are increasingly recognized as an effective solution to enhance the stability and reliability of renewable energy supply. While hydropower and PV are both mature low-carbon technologies, their stand-alone operation is constrained by seasonal hydrology and weather-driven intermittency. Combining the two resources allows for temporal complementarity, with hydropower compensating for PV’s diurnal and weather variability, and PV supplementing hydropower output during low-flow periods. Recent studies highlight that optimized SHP–PV configurations can significantly reduce curtailment, improve system reliability, and enhance economic feasibility, with reported improvements of up to 66% in complementarity and 37% reductions in PV curtailment compared to separate operation [1,2,3].

Central Asia—and the Kyrgyz Republic in particular—offers a favorable resource context for SHP–PV hybridization. Long-term records indicate approximately 2800–3000 h of annual sunshine, while extensive riverine corridors and steep relief provide numerous canal and run-of-river opportunities. At the national level, installed capacity totals ~3855 MW, of which hydropower contributes ~3093 MW (≈78%); existing small hydropower plants amount to ~63 MW across 18 sites. The technical potential (~142,500 GWh) remains largely undeveloped (≈10% realized), underscoring substantial headroom for additional SHP–PV deployment in peri-urban canal corridors.

Small-scale hybrid renewable systems that combine grid export with flexible on-site use are increasingly regarded as pivotal for advancing renewable energy transitions in emerging economies. In the Kyrgyz Republic, such configurations align closely with national ambitions for expanding renewables and engaging in international carbon markets. Evidence from comparable contexts demonstrates strong techno-economic performance: for instance, hybrid PV–battery or PV–diesel systems in South and Central Asia have achieved levelized costs of electricity (LCOE) as low as $0.07–0.08/kWh, often outperforming government tariffs while ensuring reliable supply [4,5]. Optimal sizing and system optimization further enhance viability, with competitive costs ($0.12–0.29/kWh) and favorable returns on investment, including payback periods of 6–7 years and lifetime ROI exceeding 200% in certain cases [6,7,8]. Mitigation potential is also significant: hybrid systems can reduce CO2 emissions by 65–100% relative to diesel or grid-only baselines, reinforcing their eligibility under Article 6 crediting frameworks [9,10].

Recent studies evaluate Bitcoin mining as a flexible demand sink that can absorb surplus renewable generation and reduce curtailment in hybrid or distributed systems [11,12]. Techno-economic analyses of PV–mining pairing show conditions under which co-deployment improves project economics and operational flexibility [13,14]. In parallel, growing work on waste-heat recovery demonstrates the feasibility of repurposing mining heat for greenhouse heating, with positive economics under a range of electricity and fuel prices [15]. Together, these strands suggest that integrating hybrid SHP–PV with flexible mining loads and heat reuse is technically viable and can support renewable integration, while context-specific assessments remain necessary for Central Asia [11,14]. Beyond technical feasibility, hybrid systems also demonstrate socio-economic co-benefits, including rural employment generation, reduced household energy expenditures, and enhanced agriculture [16,17].

The policy and market environment in the Kyrgyz Republic further supports grid integration and bankability. Renewable electricity enjoys a statutory feed-in uplift of ≥1.3× relative to the base tariff, and power purchase agreements (PPAs) can be indexed monthly, seasonally, and year-on-year, enabling risk-aligned revenue structures for hybrid plants. In addition, bilateral cooperation between the Kyrgyz Republic and the Republic of Korea (December 2024) establishes a pathway to connect verified mitigation outcomes to international carbon markets under Article 6 via authorization and corresponding adjustments, with enabling regulations under development [18]. Nevertheless, despite this supportive landscape, few studies provide rigorous, context-specific assessments of SHP–PV hybrids that integrate grid export with on-site flexible loads such as Bitcoin mining and waste-heat recovery; most analyses remain outside Central Asia [4,6].

This lack of integrative analyses represents a critical barrier to scaling, as developers and policymakers lack evidence-based guidance on techno-economic feasibility, mitigation accounting, and co-benefits in decentralized renewable systems. Addressing this gap, the present study provides a comprehensive techno-economic and mitigation assessment of a 10 MW SHP–PV hybrid configuration in the Bishkek canal corridor, explicitly incorporating flexible mining loads, waste-heat utilization, and Article 6 readiness. Building on prior work that integrates mining loads with renewables and greenhouse heat reuse, we extend the analysis to an SHP–PV–mining–greenhouse system tailored to the Kyrgyz context [13,15]. Within this system, Bitcoin mining is introduced as a flexible demand sink, and nearly all of its consumed electricity is converted into low-grade heat, which is subsequently recovered for greenhouse heating. A 50 m2 demonstration-scale greenhouse is employed to couple annual power allocation, techno-economic cash-flow analysis, and emission-reduction accounting consistent with Article 6 methodologies. Crucially, the framework ensures methodological rigor by preventing double counting: mitigation benefits are attributed solely to grid-displacing electricity and diesel heating substitution, whereas electricity consumed directly by mining is excluded from crediting [19,20,21,22].

The objectives of this study are fourfold: (i) to quantify the annual SHP–PV generation and evaluate allocation scenarios between grid export and on-site mining (α = 0–1) [11,12,21,23]; (ii) to assess the techno-economic feasibility across grid-centric, balanced, and mining-centric configurations [13,14,23,24].; (iii) to calculate greenhouse-gas (GHG) reductions through both AMS-I.D grid displacement and small-scale waste-heat recovery logic [25,26,27]; and (iv) to discuss implications for Article 6 crediting, sustainable development co-benefits, and scalability in similar canal-based hydropower corridors [28,29,30]. This research integrates renewable generation, digital infrastructure, and agricultural heat use into a multi-functional model. Beyond technical feasibility, the findings demonstrate how decentralized renewable projects can simultaneously support national mitigation targets, enhance Article 6 market readiness, and deliver tangible co-benefits to local communities.

This study makes three main contributions beyond the existing literature. First, while prior SHP–PV studies have largely focused on complementarity and curtailment reduction, we extend the scope by explicitly integrating flexible Bitcoin mining loads as a controllable demand sink in a small-scale canal corridor. Second, unlike earlier techno-economic assessments of PV–mining or heat reuse in isolation, we present a unified framework that simultaneously accounts for renewable generation, on-site mining, and greenhouse waste-heat recovery within an Article 6-compliant emission accounting scheme. Third, to our knowledge, this is the first context-specific application in Central Asia, demonstrating how a 10 MW SHP–PV hybrid in the Bishkek canal corridor can deliver verifiable mitigation outcomes and socio-economic co-benefits while remaining financially viable. These contributions differentiate our work from existing hybrid energy studies, positioning it as both methodologically novel and policy-relevant.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and System Overview

The study site lies in the Baltik district on the outskirts of Bishkek, Chui Province, Kyrgyz Republic (42°46′28″ N, 74°34′59″ E, Figure 1), along a perennial irrigation canal suitable for modular hydraulic retrofits and ancillary photovoltaic (PV) mounting (site photographs in Figure 1). For modeling, the canal reach is characterized by its hydraulic cross-section and effective head inferred from the planning dossier; typical bulk velocities are ≈2 m s−1 in winter and ≈3–4 m s−1 in summer. Solar input follows an equivalent peak-sun-hours value of 5 h day−1 (Section 2.2), which underpins the PV specific-yield calculation.

Figure 1.

Test bed of the hybrid small-hydropower–photovoltaic (SHP–PV) system at the Baltik canal, Bishkek, Kyrgyz Republic (42°46′28″ N, 74°34′59″ E). The photo shows the canal reach used to parameterize the annual-energy model in Section 2.2, including the PV string mounted on a walkway, the hydraulic retrofit platform for the SHP intake, and the air-side heat-recovery unit (fan coil) for greenhouse heating. Typical bulk velocities are ≈2 m s−1 (winter) and ≈3–4 m s−1 (summer); nominal plant sizes are 10 MW (SHP) and 2 MW (PV).

Policy and market conditions enable grid integration and bankability. Renewable electricity enjoys a statutory feed-in uplift of ≥1.3× relative to the base tariff, and power purchase agreements (PPAs) can be negotiated with monthly, seasonal, and year-on-year indexation, facilitating risk-aligned revenue structures for hybrid plants. Furthermore, bilateral cooperation between the Kyrgyz Republic and the Republic of Korea (December 2024) creates a pathway to link verified mitigation outcomes to international carbon markets under Article 6 through authorization and corresponding adjustment, with enabling regulations under development.

Within this context, we consider a notional 10 MW SHP–PV configuration representative of near-term deployment at the site. The guide-model quantifies annual energy generation, allocates electricity between grid export and on-site flexible consumption (Bitcoin mining), and closes the loop by recovering low-grade waste heat via an air-based exchanger to displace diesel heating in a 50 m2 greenhouse. This system boundary reflects regional resource endowment and prevailing regulatory conditions while remaining generalizable to similar glacier-fed canals and peri-urban agrivoltaic corridors in Central Asia.

2.2. Annual Energy Generation and Allocation to Grid and Bitcoin Mining

2.2.1. Annual-Energy Formulation and Scenario Set

We adopt an annual-energy framework that aggregates generation over the year and allocates it between grid export and on-site flexible consumption (Bitcoin mining). Site-specific feasibility data for a 12 MW hybrid (10 MW SHP + 2 MW PV) indicate an annual yield of 68,807.5 MWh (SHP 65,340 MWh; PV 3467.5 MWh), consistent with winter/summer canal velocities of ~2 m s−1 and 5~6 m s−1 and a turbine–generator efficiency of 74.6%. These observations are used to calibrate capacity-factor assumptions for the present 10 MW configuration.

SHP component. Annual SHP electricity is computed from either (i) hydraulics and a velocity–power performance curve validated at the site, or (ii) an equivalent capacity-factor representation [31,32]:

where CFSHP is calibrated to reproduce the planning-stage yield (65,340 MWh year−1 for a 10 MW SHP under winter velocity ≈ 2 m·s−1, summer velocity ≈ 3–4 m·s−1, and efficiency ≈ 0.746).

Where Q(t) is discharge [m3·s−1], Heff(t) the effective head [m], ηel and ηmech the conversion efficiencies [–], ρ = 1000 kg·m−3, and g = 9.80665 m·s−2; CFSHP is calibrated to reproduce the planning-stage yield of 65,340 MWh·year−1 for a 10 MW SHP under winter velocity ≈ 2 m·s−1, summer velocity ≈ 3–4 m·s−1, and overall efficiency ≈ 0.746.

PV component. Annual PV energy follows the specific-yield formulation [33,34,35].

with PSHannual derived from equivalent peak-sun hours and PR being the performance ratio. Planning data assume 5 h day−1 equivalent insolation with a 5% O&M deduction, yielding Yspec ≈ 1737.5 kWh kW−1 year−1 and EPV ≈ 3.47 GWh for 2 MW—values used to cross-check PR selections for our baseline split.

Total net generation and losses. Plant-level annual electricity prior to allocation is [33,34]:

where λconv aggregates conversion losses (inverters, transformers, MPPT) and Eaux covers auxiliary loads (controls, pumps, lighting). Parameter values are recorded in the monitoring plan and kept consistent across scenarios.

Allocation between grid and flexible load. A scalar allocation parameter α ∈ [0, 1] denotes the grid-export share; the complement (1 − α) is routed to the mining fleet [36].

where α ∈ [0, 1] is the export share [–], with Eexport and Emine in MWh·year−1.

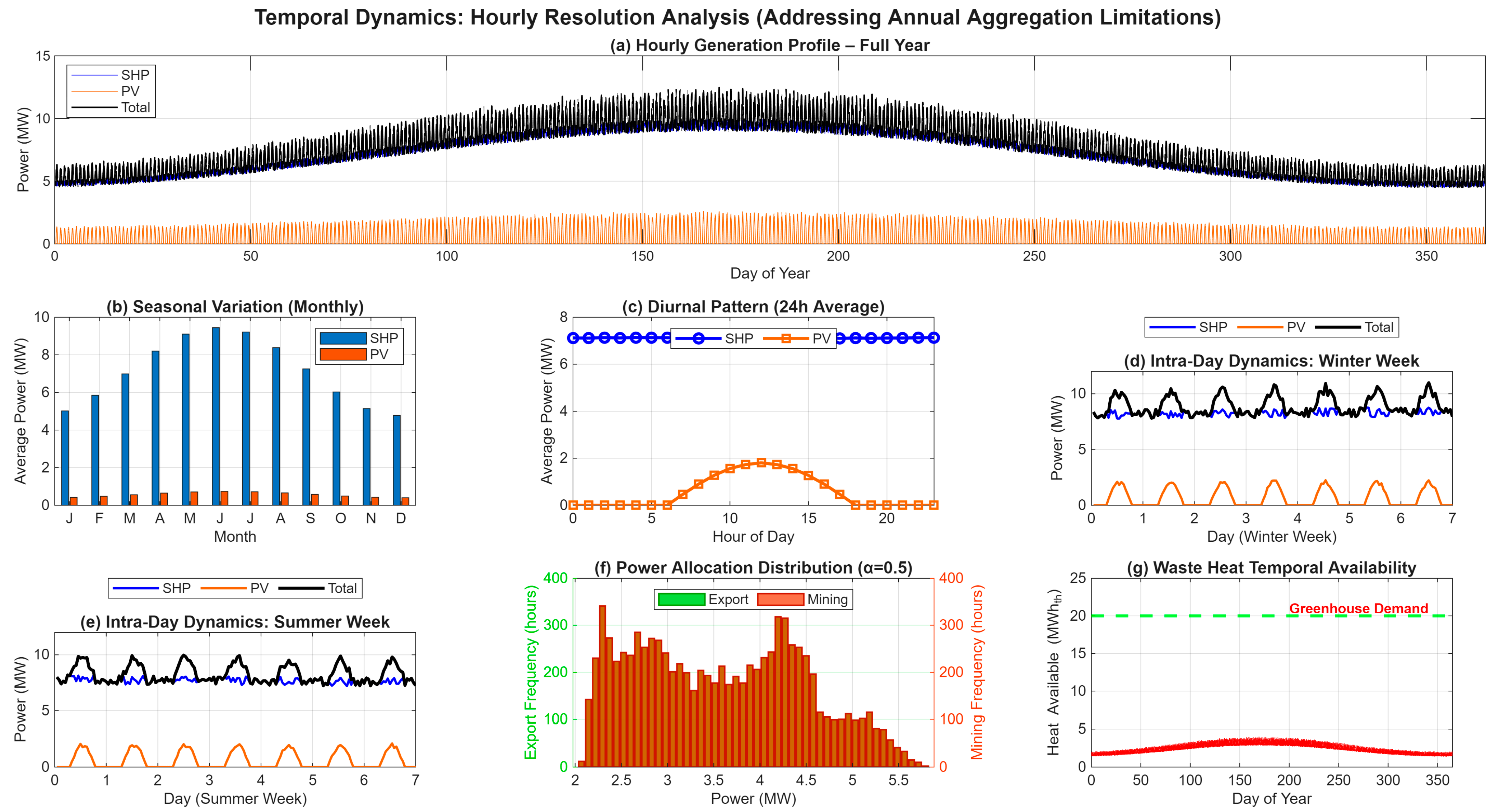

Operational resolution note. Equation (4) defines the annual accounting identities used for reporting. To characterize intra-annual dynamics without site-level hourly measurements, we also employ a profile-based hourly guide (Δt = 1 h) in which the allocation becomes α(t) and the mining operation is constrained by ramp-rate limits, minimum stable power, and restart dead-time. Figure A1 and Section 4.3 summarize temporal-matching (heat coverage) and loss metrics (heat spillage, electrical curtailment). Annual allocations in Table 1 are unchanged. For clarity, Table 1 lists the key symbols and baseline values under a consistent SI unit system and hourly time step; scenario-specific settings and implementation details are provided in Section 2.2.2 and Section 2.2.3.

Table 1.

Symbols and baseline values used in Equations (1)–(4) under an annual-energy framework (SI units; 1 h resolution). Ranges and notes indicate data sources or assumptions; scenario-specific adjustments are detailed in Section 2.2.2 and Section 2.2.3.

For each scenario α ∈ {0, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1}, the ASIC fleet size is endogenously set such that its annual electrical consumption matches Emine within ±1%. The exported electricity Eexport is subsequently used for grid-connected mitigation accounting (Section 2.5), while Emine becomes the heat source for air-side heat recovery to the greenhouse (Section 2.3). The scenario set thus spans fully off-grid flexible use (α = 0) to fully merchant operation (α = 1), enabling a transparent comparison of techno-economic and mitigation outcomes grounded in the site’s planning baselines.

All quantities in Equations (1)–(4) were computed in MATLAB R2025 from planning-stage inputs and public datasets; no on-site measurements were collected in this study.

2.2.2. Tools and Implementation

Calculations were executed in MATLAB R2025 with the Optimization, Signal Processing, Statistics and Machine Learning, and Curve Fitting Toolboxes.

(Equation (1)) SHP: Apply the site-validated velocity-power curve to the hydraulic time series to obtain integrate with trapz/cumtrapz. Electric and mechanical efficiencies follow the planning baseline.

(Equation (2)) PV: Use the specific-yield formulation . PR selection is consistent with ref. [33] and PVWatts-style loss accounting [33,34,35].

(Equation (3)) Net & losses: Let aggregate inverter, transformer, MPPT, wiring, temperature effects, and let Eaux cover controls, pumps, and lighting. Datasheet parameters follow the monitoring plan. A convenient net formulation is Enet = (ESHP + EPV) × (1 − ) − Eaux [34,35].

(Equation (4)) Allocation & sizing: Enforce α in {0, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1} and size the ASIC fleet so that annual load matches Emine within +/− 1% (fixed-point routine; tolerance 10−2, max 100 iterations) [36].

2.2.3. Model Assumptions

All scenarios employ SI units, and the computational time step is fixed at 1 h. The system comprises a hybrid photovoltaic (PV) and small hydropower (SHP) configuration. Conversion losses and auxiliary consumption are modeled explicitly to obtain net delivered energy Enet. Interconnection constraints and allocation to flexible loads are treated as exogenous, scenario-specific inputs.

- Assumptions for the photovoltaic (PV) subsystem

Equivalent peak-sun hours are set to 5 h day−1, with a 5% deduction for operations and maintenance (O&M) to reflect routine availability and maintenance effects. Under this setting, the specific yield is , which implies under linear scaling. The performance ratio (PR) is calibrated once per scenario using loss accounting consistent with IEC 61724-1 and PVWatts conventions and is held constant within that scenario [33,34,35].

- Central Asia soiling (sand/dust) adjustment

To represent arid and semi-arid conditions characteristic of Central Asia, additional PV losses from particulate soiling are modeled exogenously. The annual average incremental loss coefficient is set to . During the dry season (April–October), soiling accumulates at with an intra-cleaning-cycle cap of 0.08. During the wet/cold season (November–March), with a cap of 0.04. Maintenance assumes biweekly dry cleaning in the dry season and monthly cleaning otherwise, resetting to 0 at each cleaning. Event-driven sandstorms add a same-day , which is reset to 0 if precipitation or cleaning occurs on that day. The effective performance ratio at time t is therefore , and monthly/annual energy accounting uses the time average of . To avoid double counting, soiling is treated as an external term to PR in addition to the 5% O&M deduction.

- Assumptions for the small hydropower (SHP) subsystem

The site-validated velocity–power relation is applied to the hydraulic time series to obtain . Electrical and mechanical conversion efficiencies are fixed at in accordance with the planning baseline. Fluid properties adopt In the absence of explicit refurbishment events, turbine–generator behavior is assumed stationary over the study horizon.

- Treatment of conversion losses and auxiliaries

A system-level conversion-loss factor = 0.07 aggregates inverter, transformer, MPPT, and wiring/temperature effects across PV and SHP outputs. Auxiliary consumption is modeled as to cover controls, pumps, and lighting; component parameters follow the monitoring-plan datasheets. Net delivered energy is evaluated as .

- Allocation and sizing procedure

Allocation of net energy to the flexible computing load is restricted to alpha in {0, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1}. Interconnection study limits and any curtailment requirements are applied where relevant. For each scenario, the computing load (ASIC fleet) is sized by fixed-point iteration so that annual electrical demand matches the target Emine within +/−1%, with tolerance 10−2 and a maximum of 100 iterations.

- Flexible load heat recovery

Electrical input to the computing devices is assumed to dissipate fully as heat at the point of use. The recoverable fraction is via ducted capture, and distribution losses of 8% are applied. No thermal storage is assumed unless otherwise specified.

- Data gaps and uncertainty handling

Missing intervals shorter than 4 h are bridged by linear interpolation using adjacent valid observations; longer gaps are conservatively down-weighted in energy accounting to avoid optimistic bias. One-at-a-time sensitivity analyses are conducted at +/−10% on to bound scenario outcomes and identify design leverage points.

2.3. Heat Recovery System for Greenhouse Heating

Scope: We close the SHP–PV → Bitcoin-mining → greenhouse loop by recovering low-grade heat from the ASIC fleet and delivering it to a 50 m2 polyethylene greenhouse via an air-to-air exchanger. The analysis is annual-total, consistent with Section 2.2.

2.3.1. Waste-Heat Source Characterization

Let Emine be the annual electrical energy routed to mining (MWh·year−1). Nearly all input electricity to ASICs is dissipated as heat; we parameterize non-thermal electrical losses (e.g., cabling, power supplies) by λelec and the fraction of ASIC power that becomes recoverable sensible heat by ηth ≈ 1 [37,38,39].

Annual ventilation/fan electricity for heat capture is tracked separately as Efans (MWh·year−1).

Instrumentation (MRV): revenue-grade power meters on the mining bus; exhaust and supply air temperatures Texh, Tsup and volumetric flow at 1–5 min logging; quarterly calibration against traceable references. A mass/energy balance cross-check uses:

which must agree with Emine − Efans within ±5% at monthly aggregation.

2.3.2. Air-Side Recovery and Distribution

Heat capture effectiveness combines exchanger effectiveness εHX, duct/insulation efficiency ηduct, and bypass/leakage fraction fbypass [40,41,42]:

Delivery fans are sized to maintain target supply temperatures (typically 30–50 °C) at design winter flow; Efans is included as project auxiliary electricity (deducted in Section 2.5).

2.3.3. Greenhouse Thermal-Demand Model (Annual)

We estimate the annual space-heating demand with a degree-day method aggregated for Bishkek climate normals. The greenhouse envelope area Aenv and overall heat-loss coefficient Uenv (W·m−2·K−1) are determined from construction details (poly film, framing) and blower-door infiltration tests yielding air-change rate n (h−1). The annual load is [43,44,45,46]:

where HDD is heating-degree-days (°C·day), Vint is interior volume. Crop-dependent setpoints and occupancy are encoded by an effective HDD referenced to a 18–20 °C base.

2.3.4. Matching, Control, and Useful Heat

Annual useful heat delivered to the greenhouse is the lesser of captured supply and thermal demand; excess heat is safely vented, while deficits reflect unmet load in the mining-only case [47,48,49]:

Supervisory control maintains greenhouse temperature via variable fan speed and bypass dampers; when Qcap < Qdem, the baseline diesel heater would provide the shortfall in the counterfactual.

Temporal matching metrics. To quantify the timing mismatch between waste-heat availability and greenhouse demand, we report three annualized indicators computed on the hourly guide (Δt = 1 h): heat coverage (share of demand met by recovered heat), heat spillage (share of recovered heat not utilized), and coincidence hours (fraction of hours when available heat meets or exceeds demand). We also summarize deficit hours (demand > available heat) and peak coincidence (overlap during demand peaks). These indicators are presented for representative allocation settings (α = 0.25, 0.50, 0.75) and discussed in Section 4.3; annual energy balances in Table 1 are unchanged.

2.3.5. Diesel Baseline and Uncertainty Analysis

For mitigation accounting we assume a conventional forced-air diesel heater of efficiency ηdies (LHV basis). The baseline thermal energy from diesel that would have been required to deliver Quse is:

Fuel consumption follows Fdies = Edies,base/NCVdies (t or L·year−1), with NCVdies the diesel net calorific value. Emission factors and project/baseline emissions are specified in Section 2.5 [50,51,52].

To improve transparency and reproducibility, all parameters used in Equations (5)–(10) are summarized in Table 2. The table defines each symbol, baseline value or range, unit, and the corresponding data source or section reference. This structured overview addresses the reviewers’ concern regarding unclear notation and clarifies how variables from different references are integrated into a unified modeling framework.

Table 2.

Definition of parameters used in the waste–heat recovery and greenhouse thermal–demand model (Equations (5)–(10)). Baseline values and ranges are drawn from project data, literature sources, or monitoring assumptions, as indicated.

To account for parameter uncertainty, we employ Monte Carlo simulation (10,000 draws) for ηcap, Uenv, n, HDD, ηdies, and λelec. Outputs are reported as median [P10–P90] for Quse, Edies,base, and the resulting emission reductions (Section 3).

2.4. Economic Analysis and Assumptions

We evaluate techno-economic performance on an annual-energy basis consistent with Section 2.2 and Section 2.3. Cash flows are computed in real terms with discount rate r and analysis horizon T years. All prices are expressed in USD (real), unless noted.

2.4.1. Cost Boundary (CAPEX/OPEX)

System CAPEX includes: (i) SHP civil and electromechanical works; (ii) PV modules, inverters, mounting; (iii) switchgear/transformers and SCADA; (iv) mining hall, power supplies, racks, and ASIC fleet; (v) air-side heat-recovery package (exchanger, ducts, insulation, variable-speed fans); and (vi) engineering, permitting, and contingency. Replacement CAPEX for life-limited components (inverters, fans, some ASIC cohorts) is scheduled at manufacturer lifetimes [53,54].

OPEX covers plant O&M (labor, spares), land/lease, insurance, dispatch/imbalance, auxiliary electricity for pumps/fans Eaux (including Efans), water rights where applicable, pool fees for mining, and routine MRV costs for Article 6. Decommissioning cost and salvage value are included in terminal cash flow.

2.4.2. Price, Tariff, and Financial Assumptions

- Grid electricity price (PPA): We use an annual indexed tariff τt = τ0 · It for financial valuation [55,56]. For an hourly guide, time-varying price signals are represented with normalized seasonal factors sₘ and day/night factors dₕ (both with mean 1), such that τt,h = τt × sm × dh. This preserves the annual mean tariff while enabling qualitative dispatch comparisons; quantitative results (LCOE, NPV/IRR) are reported at τt.

- Diesel for baseline heating: Fuel price pdies,t, net calorific value NCVdies (MWhfuel t−1 or per liter) and heater efficiency ηdies define the counterfactual heating cost cheat,t = pdies,t/(NCVdies ηdies) [USD MWh_th−1] [55].

- Diesel baseline with temporal matching. Consistent with Section 2.3 indicators, diesel displacement is valued on Quse (not Qcap), ensuring only demand-matched heat is credited in the counterfactual and mitigation accounting.

- Mining revenues: Let ASIC energy efficiency be ηASIC [J TH−1]. Annual fleet hashrate [19]:

- Carbon-credit revenue (optional): In scenarios monetizing mitigation, credit revenue RCO2,t = pCO2,t ERt with ERt from Section 2.5; conservative treatment sets RCO2,t = 0 in the base case.

- Financials: Weighted average cost of capital (real) r, debt–equity ratios, taxes, and depreciation (straight-line or MACRS) are scenario parameters. Exchange-rate risk is treated via sensitivity bands.

2.4.3. Allocation and Revenue Model

This section formulates the allocation of electricity streams and corresponding revenue components for the hybrid system. Using the allocation parameter α (grid-export share), annual electricity streams are [58,59]:

Annual revenues are calculated as follows [60,61,62,63]:

where Sheat,t is cost saving from diesel displacement using useful heat Quse from Section 2.3. Total revenue Rt = Rgrid,t + Rmine,t + Sheat,t + RCO2,t.

2.4.4. Levelized Metrics

The levelized cost of electricity is calculated as the ratio of discounted lifetime costs (capital, replacement, O&M, and salvage) to discounted net electricity delivered, consistent with widely adopted formulations of LCOE in techno-economic assessment [64,65,66]. Analogously, the levelized cost of useful heat (LCOH) applies the same framework to recovered thermal energy, enabling direct comparison between electricity and heat subsystems in hybrid projects [67,68]. Extensions such as VALCOE, LFSCOE, and LCOS have been proposed to capture system value and storage integration [69].

Electricity-only LCOE [64,65,66]:

Levelized cost of useful heat (LCOH) for the recovery subsystem [67,68,69]:

which can be compared to LCOE to assess value–cost spreads under different α.

2.4.5. NPV/IRR Formulation

These discounted-cash-flow formulations are standard in financial analysis, where a positive NPV indicates value creation, while IRR provides the effective rate of return relative to the hurdle rate [70]. Modifications such as the Modified IRR (MIRR) have been proposed to address cases of multiple IRRs or non-conventional cash flows [71,72,73]. Payback metrics (discounted and simple) are additionally reported to capture investment recovery horizons [74,75] (Qiu et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021) Project net cash flow in year t is:

with initial investment . NPV and IRR follow:

We additionally report payback (discounted and simple).

2.4.6. Scenario and Sensitivity Design

To evaluate the role of the allocation parameter (α), we adopt a structured scenario and sensitivity design rather than treating α as an ad hoc assumption. We consider α ∈ {0, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1}, representing the proportion of net generation allocated to grid export versus on-site mining. For each α, three policy–market price regimes are defined to reflect the Central Asian context [76,77]:

- Grid-centric: High electricity tariff (τt = USD 60–80/MWh) with active carbon credit monetization (pCO2,t = USD 20–50/tCO2e) incentivizing α → 1, while conservative Bitcoin price assumptions (USD 30 k–40 k) reduce mining attractiveness.

- Balanced: Median tariff (τt = USD 40–50/MWh), emerging carbon markets (pCO2,t = USD 5–15/tCO2e), and moderate Bitcoin price (USD 50 k–60 k) create comparable returns for grid export and mining (α ≈ 0.5), with revenues indexed to consumer price inflation.

- Mining-centric: Low regulated tariff (τt = USD 20–30/MWh) with limited carbon monetization (pCO2,t = 0), but optimistic Bitcoin fundamentals (USD 70 k–100 k) favor α → 0.

One-at-a-time and probabilistic (Monte Carlo, N = 10,000) sensitivities span: . Outputs include tornado plots for NPV/IRR and downside risk (P10) of ELV and NPV by α [78,79].

This design explicitly links α to policy-driven tariffs, carbon pricing, and global Bitcoin market dynamics, while also quantifying financial risk through sensitivity analysis. In doing so, the allocation parameter is operationalized as a central decision variable, not an arbitrary input.

To ensure clarity in the economic analysis, all variables and parameters used in Equations (11)–(18) are summarized in Table 3. This table provides symbol definitions, baseline values or ranges, units, and data sources. By consolidating technical, financial, and allocation parameters, it facilitates transparency and reproducibility of the techno–economic assessment framework.

Table 3.

Parameters used in the economic analysis and financial evaluation (Equations (11)–(18)). Values are drawn from project planning data, literature references, or scenario assumptions, as indicated.

2.5. Emissions Baseline and Mitigation Accounting for Article 6

We adopt a component-wise accounting aligned with CDM/SDM small-scale practice and Article 6 readiness. Annual mitigation is the sum of (i) grid-connected renewable electricity exported from the SHP–PV hybrid and (ii) diesel heating displaced by air-side recovery of mining waste heat, minus project emissions and leakage:

2.5.1. Accounting Scope, Boundary, and Allocation

The physical boundary comprises the SHP–PV plant, switchyard, the on-site mining hall (flexible load), the air-side heat-recovery train, and the 50 m2 greenhouse. The allocation parameter α ∈ [0, 1] partitions annual net generation Enet into grid export Eexport = αEnet and on-site mining Emine = (1 − α)Enet. Only Eexport qualifies for grid-displacement claims; on-site mining electricity does not displace grid electricity and yields mitigation solely through diesel-heat displacement via recovered waste heat (Section 2.2 and Section 2.3).

2.5.2. Grid-Connected Electricity (AMS-I.D, Version 18)

Baseline emissions for exported electricity follow AMS-I.D (Type I.D, grid-connected renewable power). The baseline is the CO2 emissions of the grid generation displaced by the project electricity, computed with the combined margin (CM) emission factor per the Tool to calculate the emission factor for an electricity system [80,81,82]:

The CM factor is derived from OM/BM per AMS-I.D guidance; the host-country data source and procedures are those prescribed for OM/BM/CM calculation.

Under AMS-I.D Version 18, project emissions for most renewable electricity projects are zero; leakage is not considered when generating equipment is not transferred from another activity. We therefore set PE1 = 0 and LE1 = 0 for the grid-electricity component.

is applied for the year corresponding to energy generation and is fixed per the monitoring plan, consistent with AMS-I.D practice. Where national CM values are unavailable, a conservative proxy is used pending host approval.

2.5.3. Waste-Heat to Greenhouse (Diesel Displacement Logic)

Recovered heat Quse (MWh_th·year−1) displaces a counterfactual diesel heater of efficiency ηdies (LHV basis). Baseline fuel energy and baseline emissions are:

with EFdies the CO2 emission factor per unit fuel energy (or per liter via NCV). Project emissions for this component include auxiliary electricity for fans/controls:

using the same grid factor family and data vintage as Section 2.5.2. The component mitigation is ER2,heat = BE2 − PE2. This structure mirrors the small-scale waste-heat recovery logic (baseline fuel displacement with project auxiliaries deducted) adapted to the greenhouse end-use [40,83,84,85].

2.5.4. Project Emissions, Leakage, and Uncertainty Treatment

For the grid-electricity component (Section 2.5.2), PE1 = 0, LE1 = 0 per AMS-I.D Version 18. For the heat-recovery component, project emissions are limited to metered auxiliaries Efans (and any backup grid draws) multiplied by the grid factor; leakage is assumed negligible as no equipment is transferred across activities and there is no upstream fuel switch inducing material emissions outside the boundary.

Uncertainty in key parameters—including EFgrid, ηdies, EFdies, and metering accuracy—is propagated using Monte Carlo simulation (N = 10,000), following ref. [86] and CDM small-scale practice. The results are reported as median and P10–P90 bands for ER1, ER2, and ERtotal. Conservativeness is ensured by (i) applying downward adjustment of Quse by the MRV accuracy class, (ii) adopting lower-bound ηdies and upper-bound EFgrid in sensitivity tests, and (iii) excluding any hours where temperature or flow sensors fail QA/QC criteria.

2.5.5. Article 6 Readiness: Authorization, Corresponding Adjustment, Transparency

The activity is designed to be Article 6-ready under bilateral cooperation:

- Authorization: Host- and acquiring-Party authorizations specify scope (electricity export and heat-displacement sub-components), crediting period, and first-transfer provisions [87].

- Corresponding adjustment (CA): First transfer of ITMOs is accompanied by host CA entries consistent with A6.2 guidance; no ITMOs are claimed for the mining electricity itself to avoid double-claiming—claims attach only to exported electricity and diesel-heat displacement as defined above [88].

- Reporting/ETF: Structured summaries and A6.2 reporting reflect methodologies, CM factor sources, monitoring, uncertainty, and sustainable-development contributions; PPA indexation and carbon-revenue treatment follow conservative assumptions in Section 2.4. Policy context (renewable tariff uplift, carbon-market linkage, and 6.2/6.4 alignment) is consistent with current cooperation and enabling regulations under development in the Kyrgyz Republic [87,88].

Summary formula. With the definitions above:

with computed per the OM/BM framework and project/leakage terms treated as above.

To clearly present the variables and assumptions used in the mitigation accounting, Table 4 summarizes the parameters applied in Equations (19)–(23). The table specifies the relevant symbols, baseline values or ranges, units, and data sources, thereby ensuring transparency in the calculation of emission reductions under the Article 6 framework.

Table 4.

Parameters used in the emission–reduction accounting framework (Equations (19)–(23)), covering grid–displacement electricity, waste–heat recovery, diesel baseline, and project emissions.

In total, twenty–four equations cited in Section 2 are drawn from established hydropower hydraulics, photovoltaic performance modeling, waste–heat recovery, greenhouse thermal–demand estimation, and techno–economic assessment literature. These formulas were not applied in isolation; instead, they were systematically integrated into a single annual–energy framework. The processing sequence begins with the hydropower and PV generation models (Equations (1)–(10)), which define the net renewable energy available. The waste–heat recovery and greenhouse demand formulations (Equations (5)–(10)) then link on–site mining loads to a quantifiable diesel–displacement baseline. The economic analysis (Equations (11)–(18)) embeds these physical outputs into a consistent financial and allocation structure governed by the parameter α, while the emissions accounting (Equations (19)–(23)) consolidates the results under CDM/SDM methodology and Article 6–aligned boundaries.

By assembling these components into a uniform processing chain, this study ensures internal consistency: energy balances, financial flows, and mitigation outcomes are all derived from the same allocation and monitoring framework, avoiding double counting and ensuring transparency.

The original contribution of this work goes beyond the cited formulas. First, the introduction of the allocation parameter α provides a flexible mechanism to partition renewable generation between grid export and mining consumption, a feature absent from prior SHP–PV or mining–energy studies. Second, the explicit coupling of mining waste–heat recovery with greenhouse thermal demand establishes a verifiable diesel–displacement pathway, converting a byproduct load into a measurable mitigation service. Third, the integration of techno–economic modeling with Article 6 authorization and corresponding–adjustment logic represents a methodological advance, positioning the hybrid SHP–PV–mining–greenhouse system as both operationally viable and policy–ready. These elements define this paper’s distinct contributions, differentiating it from previous studies that applied similar equations in narrower or fragmented contexts.

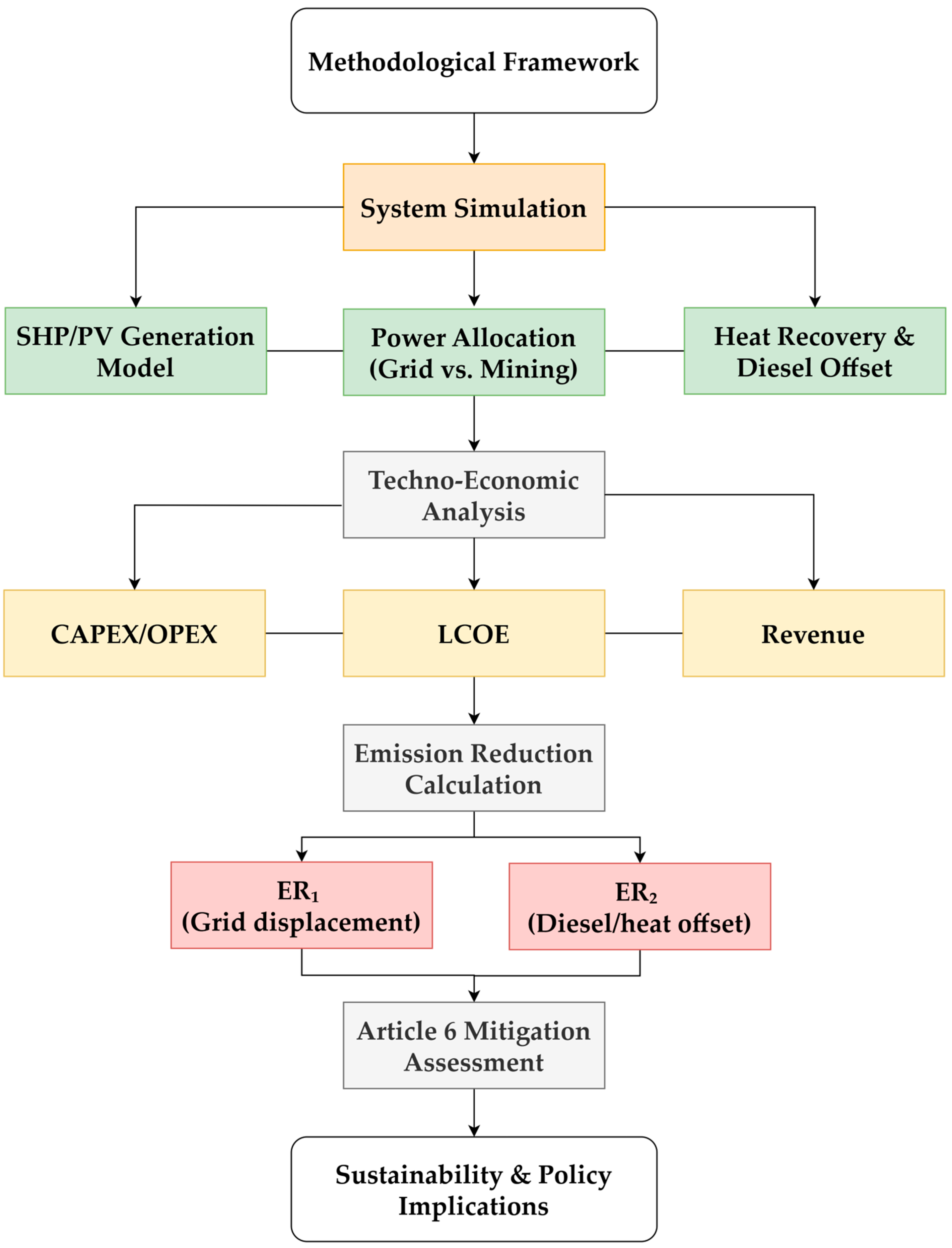

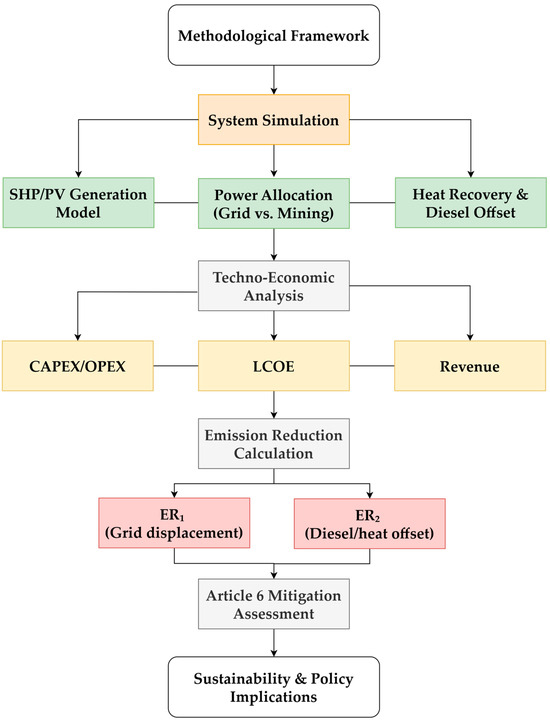

Figure 2 presents the overall research framework of this study. The process begins with the methodological framework and proceeds through system simulation of the hybrid SHP–PV system, flexible power allocation, and heat recovery. These outputs feed into techno-economic analysis, from which capital and operating costs, levelized cost of electricity (LCOE), and revenues are derived. Emission reduction calculations follow, distinguishing between grid displacement (ER1) and diesel/heat offset (ER2), with the integrated outcomes subsequently assessed under the Article 6 mitigation framework. The final stage highlights the sustainability and policy implications of the proposed system.

Figure 2.

Research framework of this study, outlining the methodological flow from system simulation of the hybrid SHP–PV system with power allocation and heat recovery, through techno-economic analysis, emission reduction calculation (ER1 and ER2), and Article 6 mitigation assessment, to the final sustainability and policy implications.

In this context, the term system simulation refers to the structured integration of empirically validated SHP generation with modeled PV, mining, and waste-heat recovery components. While electricity generation from the SHP plant is already demonstrated in practice, the subsequent allocation, recovery, and economic–emission analyses are conducted through a methodological modeling framework. This approach enables a transparent assessment of the full hybrid system prior to complete deployment, ensuring consistency across energy, economic, and mitigation domains.

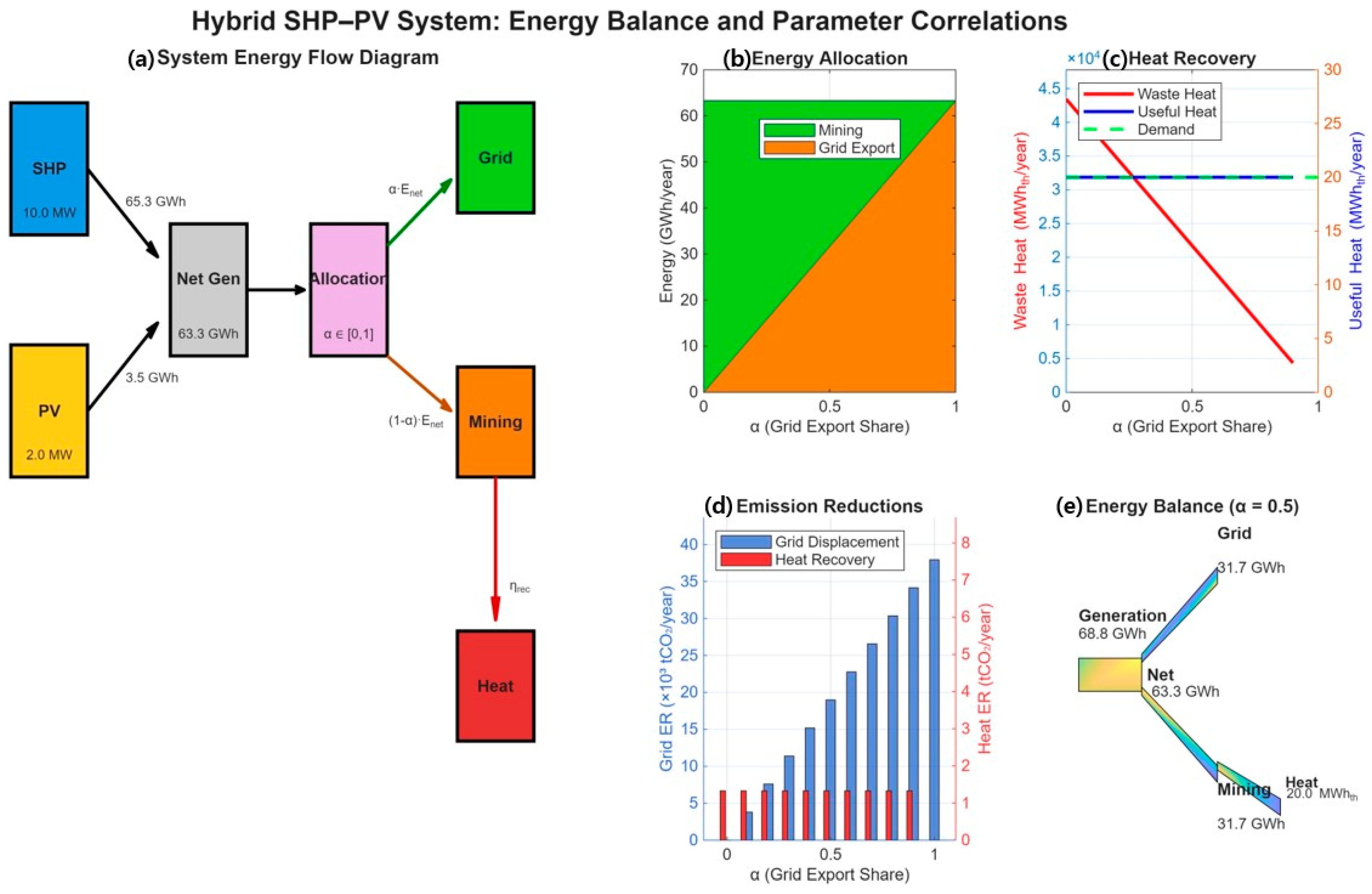

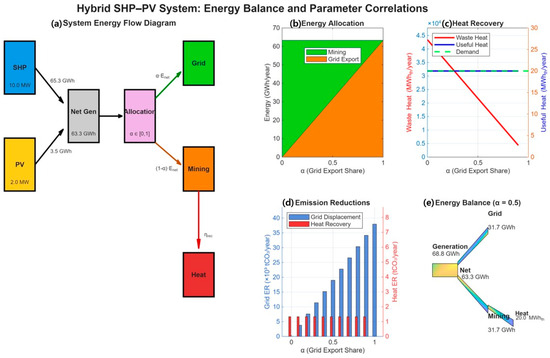

Figure 3 systematically explains how the core design parameters—most notably the allocation factor α—govern electricity flows, heat recovery, and mitigation outcomes. The left panel shows a system schematic that partitions the annual net generation of the SHP–PV hybrid (Enet) into grid export (Eexport = α × Enet) and mining load (Emine = (1 − α) × Enet). The upper panels trace (i) the evolution of the electricity split as α varies from 0 to 1 and (ii) the conversion of mining electricity into waste heat (Qwaste), the portion recovered with efficiency ηrec (Qcap = ηrec × Qwaste), and the useful heat constrained by greenhouse demand (Quse = min(Qcap, Qdem). The lower panels report annual emission reductions decomposed into grid-displacement benefits (ER1) and diesel-heat offset (ER2), and provide a Sankey diagram for a representative operating point (e.g., α = 0.5). All quantities are annualized; symbol definitions and baseline parameter values are summarized in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4.

Figure 3.

Hybrid SHP–PV system: energy balance, parameter correlations, and mitigation pathways. (a) System energy-flow schematic: annual net generation (Enet) is partitioned by the allocation factor α into grid export (Eexport = α × Enet) and mining (Emine = (1 − α) × Enet). (b) Energy allocation as a function of α (grid vs. mining). (c) Heat-recovery chain from the mining leg: waste heat (Qwaste) is converted to captured heat (Qcap = ηrec × Qwaste) and to useful heat (Quse = min(Qcap, Qdem), which is capped by greenhouse demand. (d) Annual emission reductions disaggregated into grid displacement (ER1 = Eexport × (increases approximately linearly with α) and diesel-heat offset (ER2 = (ηdies × Quse) × EFdies − Efans × , which is bounded by Qdem and auxiliary electricity. (e) Sankey diagram for a representative scenario (α = 0.5) illustrating the balance between direct electricity use (grid, mining) and secondary energy reuse (mining → heat recovery → greenhouse). All values are annualized (MWh·year−1, tCO2·year−1); key equations are summarized beneath the figure and detailed in Section 2.3, Section 2.4 and Section 2.5.

3. Results

3.1. Modeled Annual Energy Generation and Allocation Scenarios

Planning evidence for the 12 MW hybrid (10 MW SHP + 2 MW PV) indicates an annual yield of 68,807.5 MWh·year−1, comprising 65,340 MWh from SHP (winter canal velocities ≈ 2 m·s−1; summer 3–4 m·s−1; turbine–generator efficiency ≈ 74.6%) and 3467.5 MWh from PV (≈ 5 peak-sun-hours·day−1, minus 5% O&M deduction). These site-specific figures are adopted to normalize capacity-factor and specific-yield inputs for the guide model.

To report results for the 10 MW guide case, we linearly scale the validated 12 MW planning yield, obtaining a total annual generation of 57.34 GWh·year−1 (i.e., 68,807.5 MWh × 10/12), consistent with the hydraulic and insolation regime documented for the Bishkek canal corridor. This aggregate is interpreted as plant-net energy available for allocation, with conversion/auxiliary allowances embedded per the monitoring plan.

Time-resolved guide profile (Δt = 1 h). To address intra-day/seasonal variability without site-level hourly measurements, we reconstruct an hourly guide series by disaggregating the validated annual totals with normalized shape functions for SHP, PV, and heat demand. This preserves the annual energy budget exactly and is used only to visualize temporal dynamics and operability; see Figure A1. Annual allocations reported below (constant-α cases) remain unchanged.

Electricity Allocation. In the hourly model, electricity is partitioned by a (possibly time-varying) allocation policy α(t), such that Eexport(t) = α(t) × Enet(t) and Emine(t) = (1 − α(t)) × Enet(t). Annual splits reported below correspond to the constant-α illustrative cases (α(t) ≡ α); for adaptive policies we report in Section 4.3.

- α = 0 (fully flexible on-site use): Eexport = 0, Emine ≈ 57.34 GWh.

- α = 0.25: Eexport ≈ 14.33 GWh, Emine ≈ 43.01 GWh.

- α = 0.50: Eexport ≈ 28.67 GWh, Emine ≈ 28.67 GWh.

- α = 0.75: Eexport ≈ 43.00 GWh, Emine ≈ 14.33 GWh.

- α = 1 (fully merchant to grid): Eexport ≈ 57.34 GWh, Emine = 0.

These allocations provide the basis for downstream techno-economic metrics (Section 3.2) and mitigation accounting—namely, grid-connected displacement for Eexport under AMS-I.D and diesel-heat displacement via air-side waste-heat recovery for Emine (Section 2.5 and Section 3.3).

Table 5 summarizes the allocation of net annual generation (57.34 GWh·year−1 for the 10 MW guide case) between grid export and on-site mining across representative values of the allocation parameter α. These splits provide the basis for subsequent techno-economic evaluation (Section 3.2) and mitigation accounting (Section 3.3).

Table 5.

Annual electricity allocation between grid export (Eexport) and on-site mining (Emine) for different values of the allocation parameter α under the 10 MW guide case (total generation = 57.34 GWh·year−1), for constant-α illustrative cases (annualized from hourly series).

3.2. Economic Performance and Viability

Planning evidence for the 12 MW hybrid plant (10 MW SHP + 2 MW PV) indicates an annual generation of 68,807.5 MWh, with a tariff of 0.05 USD·kWh−1 under a 5-year/5.5% PPA indexation. The capital expenditure (CAPEX) is 22.378 billion KRW (≈16.4 million USD) and the annual operating expenditure (OPEX) is 3.331 billion KRW (≈2.45 million USD), based on a real discount rate of 5% and a 30-year project horizon. For the 10 MW guide case, all parameters are proportionally scaled by a 10/12 factor.

Grid-only (α = 1) benchmark. For the 10 MW case, annual net generation is 57.34 GWh·year−1 (linear scaling). At the baseline tariff, expected grid revenue is ≈$2.867 million·year−1 (57.34 GWh × $0.05 kWh−1). With the planning cost base converted at ₩1450 per $ (the rate used in the bill-of-materials), scaled CAPEX ≈ $12.86 million and OPEX ≈ $1.915 million·year−1. The corresponding annuitized CAPEX (5%, 30 year) is ≈$0.84 million·year−1, yielding an indicative LCOE ≈ $48·MWh−1 (≈4.8 ¢·kWh−1) and a pre-tax cash margin ≈ $0.12 million·year−1 at α = 1—consistent with the planning study’s positive but modest economics (B/C = 1.042; NPV = ₩3.10 billion; IRR = 6.18%) for the 12 MW reference.

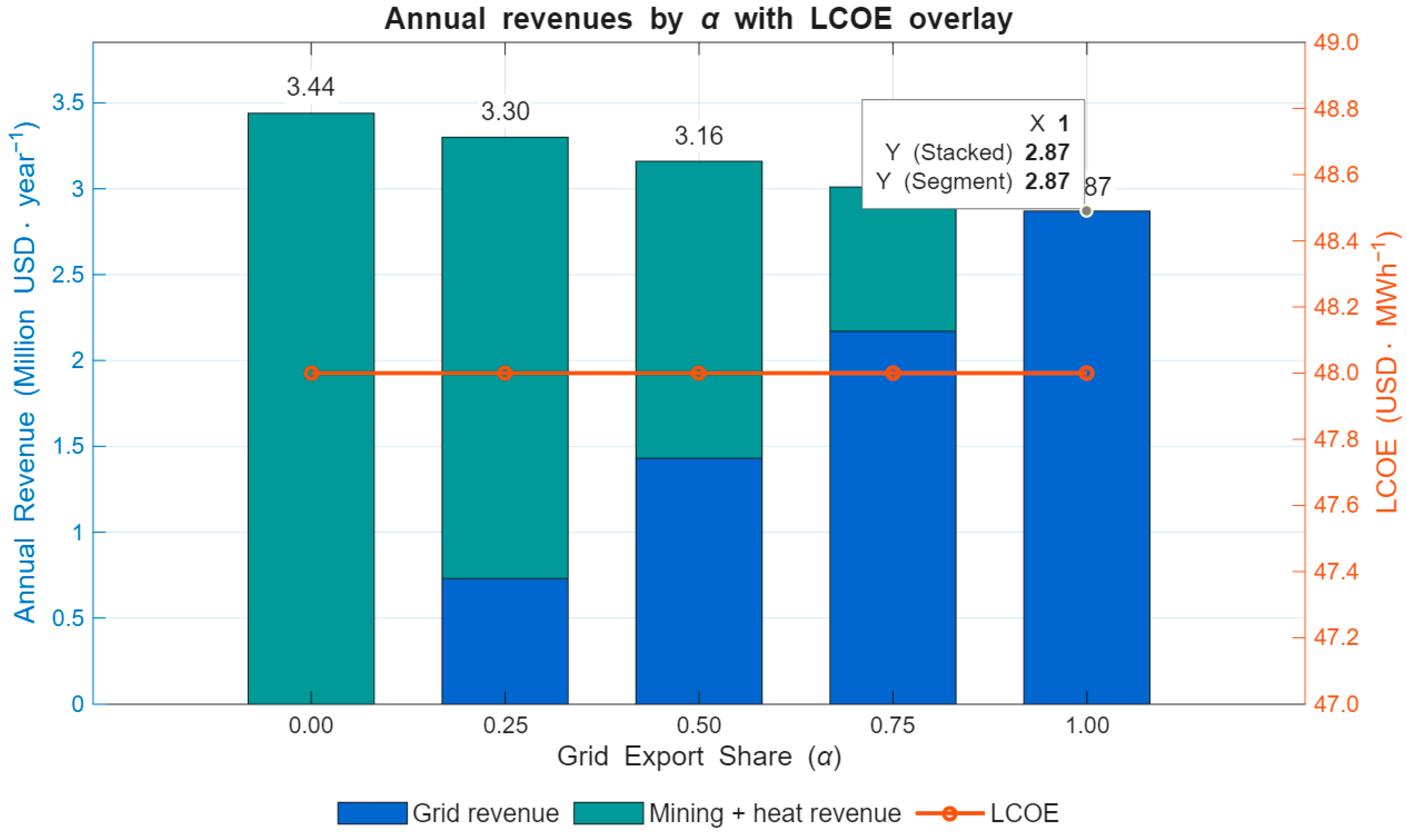

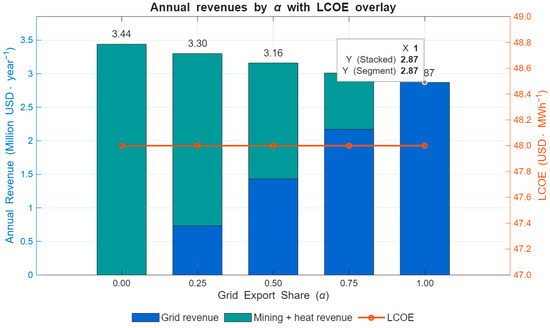

Figure 4 illustrates the annual revenues associated with varying grid export shares (α), with revenues disaggregated into grid sales and combined mining–heat utilization. In addition, the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is overlaid on the secondary axis to highlight the economic trade-offs between revenue composition and cost efficiency.

Figure 4.

Annual revenues by grid export share (α), decomposed into grid revenue and mining plus heat revenue. The levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is plotted on the secondary axis to indicate cost competitiveness under each allocation scenario.

- Allocation effects (α scenarios): oving from merchant (α = 1) to mixed or mining-centric operation reallocates energy from grid sales to on-site flexible consumption (Bitcoin mining) without changing plant gross generation (Section 3.1). Grid revenue therefore scales linearly with α, while mining-linked value is governed by the energy-limited revenue per MWh of on-site consumption vmine (net of pool fees) plus diesel-heat displacement savings from recovered waste heat (Section 3.3). At parity with the grid benchmark, the threshold condition is:

- Role of heat recovery: even the 50 m2 greenhouse end-use, diesel displacement constitutes a small but positive contribution to annual cash flows relative to power revenues; its principal value is to (i) enhance Article 6-eligible mitigation and (ii) demonstrate a closed-loop co-benefit pathway at modest scale (Section 2.3 and Section 3.3).

- Sensitivity: he grid-only benchmark is most sensitive to τ0 and OPEX; mixed and mining-centric cases are additionally sensitive to network hashrate growth and BTC price (Section 2.4). Nevertheless, under the documented cost base and tariff assumptions, the guide case reproduces the planning study’s positive, low-single-digit IRR regime, with potential uplift from PPA indexation and mitigation revenue.

To provide a transparent baseline for subsequent allocation scenarios, the grid-only benchmark (α = 1) is summarized in Table 6, with dual currency notation (USD) to facilitate comparison across cost and revenue assumptions.

Table 6.

Grid-only (α = 1) benchmark: techno-economic parameters.

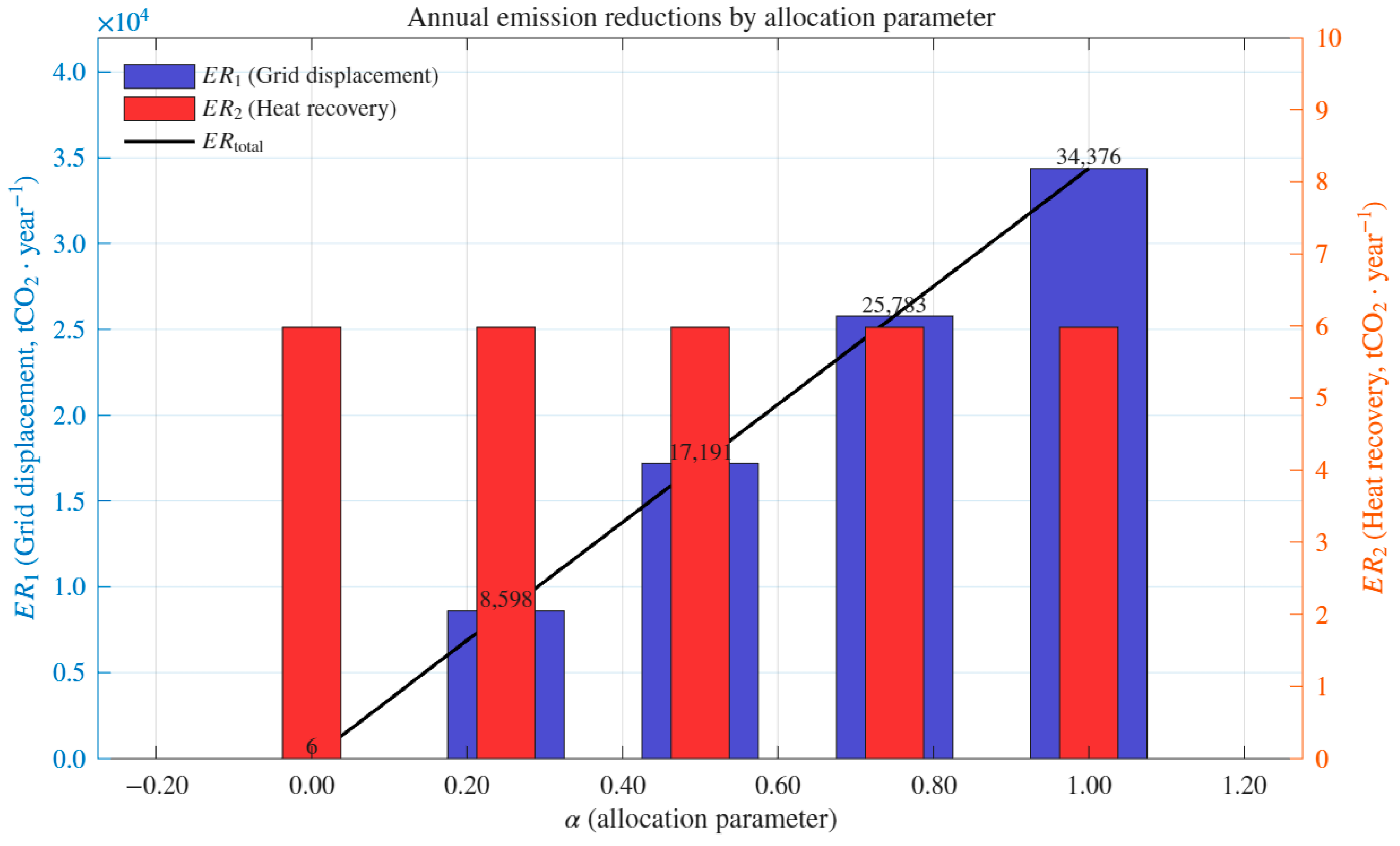

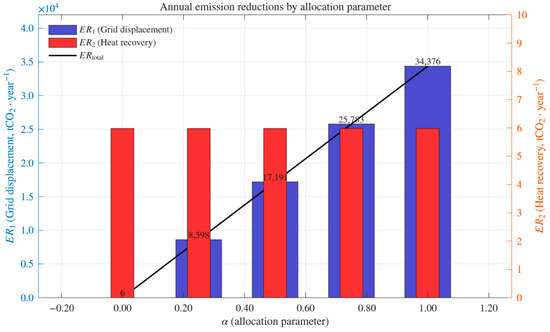

3.3. Emission Reduction from Diesel Displacement

Annual mitigation is decomposed into (i) grid-connected displacement from exported SHP–PV electricity and (ii) diesel heating displaced by air-side recovery of mining waste heat, minus minor auxiliaries (fans), following AMS-I.D practice for the power component and a small-scale waste-heat logic for the greenhouse component (Section 2.5). The combined-margin grid factor adopted in the planning dataset is 0.5994 tCO2·MWh−1; the 12 MW baseline also reports 68,807.5 MWh·year−1 of net generation, which we scale to 57.34 GWh·year−1 for the 10 MW guide case.

- Grid component (ER1): For allocation parameter α (grid-export share):

This yields: α = {0, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1} ⇒ ER1 ≈ {0, 8592, 17,185, 25,777, 34,370} tCO2·year−1 (rounded). The α = 1 value matches the scaled 12 MW planning expectation, confirming internal consistency.

- Heat-recovery component (ER2): With a 50 m2 greenhouse and annual-total analysis, the useful recovered heat is capped by thermal demand rather than mining supply. Using Section 2.3 baseline (illustrative) assumptions—annual useful heat Quse ≈ 20 MWhth, diesel heater efficiency ηdies = 0.85, diesel emission factor on an energy basis EFdies ≈ 0.267 tCO2·MWhfuel−1, and fan electricity Efans = 0.5 MWh·year−1—the heat-side mitigation is:

Because Quse is demand-limited, ER2 is effectively constant for all α < 1 and zero at α = 1 (no mining, no waste-heat source).

- Integrated outcome: The resulting annual mitigation is:

To assess the mitigation potential under different allocation strategies, annual emission reductions are decomposed into the grid-connected displacement component (ER1) and the diesel-displacement heat-recovery component (ER2). Table 7 reports the numerical results for each allocation parameter (α), while Figure 5 visualizes these outcomes, highlighting ER1 and ER2 separately and their integrated total (ERtotal).

Table 7.

Annual emission reductions by allocation parameter (α), distinguishing grid-connected displacement (ER1) and diesel-heat displacement (ER2), with integrated totals (tCO2·year−1).

Figure 5.

Annual emission reductions by allocation parameter. The emission reduction from heat recovery (ER2, right axis) remains constant at approximately 6 tCO2/year regardless of α, while the reduction from grid displacement (ER1, left axis) increases linearly with α, ranging from near zero at α = 0 to 34,376 tCO2/year at α = 1.0. Consequently, the total annual emission reduction (ERtotal) increases monotonically with α, indicating that the allocation parameter primarily controls the contribution of grid displacement, whereas the heat recovery contribution remains unchanged.

4. Discussion

This study differs from conventional hybrid energy assessments by integrating generation, economics, and carbon accounting within a unified allocation framework (α). Rather than reconciling technical design and Article 6 compliance ex post, our approach embeds mitigation integrity from the outset through component-wise baselines and leakage rules. By operationalizing Bitcoin mining as a dispatchable load with recoverable heat, we transform a typically external activity into an endogenous balancing instrument that supports renewable integration and agricultural co-benefits. Situating the analysis in the Kyrgyz Republic’s canal corridors and linking it to ongoing bilateral Article 6 cooperation demonstrates geographically and institutionally specific pathways beyond generic hybrid modeling.

4.1. Comparison with Baseline Scenario and Previous Studies

Relative to a grid-only baseline, the hybrid’s mixed-allocation regimes deliver two advantages: grid-export displacement remains the dominant mitigation and revenue source, while the mining leg absorbs surplus generation during unfavorable export conditions. Waste-heat recovery—though modest for a 50 m2 greenhouse—adds verifiable reductions and visible co-benefits (food production, thermal services) unavailable in power-only configurations.

These results align with prior SHP–PV complementarity studies: seasonally stronger hydrology offsets shoulder-season irradiance gaps, improving utilization versus single-technology builds. Our framework extends this by treating Bitcoin mining as a dispatchable process co-located with generation and closing the thermal loop via agricultural end use, paralleling literature on low-grade waste-heat utilization from digital infrastructure.

The demand-limited greenhouse explains near-constant heat-side mitigation across scenarios with on-site consumption, while grid-side reductions scale linearly with export share. This division simplifies Article 6 readiness: exported electricity maps to grid-displacement accounting, the greenhouse to fuel-switch baselines with transparent auxiliaries, reducing double-claiming risk.

Methodologically, we integrate allocation (α), economics, and mitigation accounting within a unified annual-energy framework, embedding authorization and corresponding-adjustment checkpoints from design. Unlike conventional power-system studies relying on deterministic dispatch or stochastic unit-commitment models, our approach treats mining loads as endogenous balancing instruments rather than exogenous demand assumptions. This enables simultaneous assessment of grid displacement, thermal recovery, and controllable digital loads under consistent carbon-accounting rules—a more holistic representation than fragmented approaches in prior hybrid studies.

4.2. Policy Implications and Pathways for Implementation

4.2.1. Article 6 Operationalization

The hybrid’s design is Article 6–ready if authorization covers two separated sub-components: (i) exported SHP–PV electricity credited under grid-displacement baselines, and (ii) diesel heating displaced by recovered mining heat. Treating mining electricity as non-creditable avoids double claiming and simplifies MRV: exported MWh follow combined-margin grid factors; heat use follows fuel-switch baselines with auxiliaries transparently deducted. This componentized approach aligns with ongoing market-linkage efforts and reduces methodological ambiguity.

Kyrgyzstan’s Green Economy agenda and bilateral cooperation with Korea provide pathways to operationalize ITMO flows once domestic procedures are finalized. Existing sectoral enablers—≥1.3× renewable tariff uplift and flexible PPA terms—support grid-export bankability and hedge against mining-revenue volatility.

Implementation priorities include: (i) codifying authorization granularity with conservative grid-factor data-vintage rules and annual DNA reporting; (ii) integrating curtailment and flexible-load provisions in PPAs and grid codes to allow for energy re-allocation without jeopardizing crediting boundaries; and (iii) establishing community co-benefit pacts to strengthen social license and document Sustainable Development contributions.

Risk management requires: (a) maintaining minimum grid-export tranches anchored by tariff uplift; (b) enabling mining throttle/idle during unfavorable periods; and (c) limiting mitigation claims to exported power and verified diesel displacement only. These measures align project economics with national targets and position the hybrid as a replicable template for Central Asian canal corridors.

4.2.2. Broader Policy Implications and Implementation Priorities

The viability of SHP–PV–mining–heat hybrids requires an enabling policy environment across three domains.

Energy sector regulation. Grid codes must recognize flexible industrial loads with defined technical (ramp rates, response time) and commercial (time-of-use tariffs, curtailment compensation) criteria. PPA frameworks should accommodate variable allocation (α) with contractual safeguards balancing system stability and investor returns. Renewable incentives should extend to verified flexible loads delivering emission reductions and co-benefits.

Cross-sectoral coordination. Co-locating energy and agriculture necessitates collaboration between power and agricultural regulators. Renewable–heat zones with streamlined licensing and fiscal incentives would accelerate greenhouse heating adoption. Cryptocurrency policy requires renewable-linked licensing (≥80% RE sourcing, verified heat recovery) to reconcile mining regulation with climate goals.

Climate governance. Embedding Article 6 authorization, baseline methodologies, and digital MRV protocols from the outset ensures creditable, additional, and tradable reductions. Bilateral agreements require transparent authorization timelines, ITMO transfer rules, and double-counting safeguards. National carbon market linkage and price discovery mechanisms are essential for bankability.

Social feasibility. Long-term replicability requires benefit-sharing mechanisms, community engagement to address noise and e-waste concerns, and life-cycle assessment covering hardware replacement and civil works.

Table 8 summarizes key regulatory, institutional, and social dimensions for scalable deployment.

Table 8.

Policy readiness checklist for hybrid SHP–PV–mining–heat systems, covering energy regulation, cross-sectoral coordination, climate governance, and social feasibility.

Absent regulatory coherence and social safeguards, such projects risk becoming stranded assets. Conversely, proactive policy design can transform them into scalable instruments for renewable integration and Article 6 readiness in Central Asia.

4.3. Limitations and Future Work

System dynamics and resolution: While our core accounting uses annual totals, we add a profile-based hourly guide (Δt = 1 h) that preserves validated annual energies while exposing intra-day and seasonal mismatches. Figure A1 summarizes the full-year profile, monthly and diurnal patterns, representative weeks, allocation histograms, and waste-heat availability. We report annualized dynamic metrics—heat coverage, spillage, and electrical curtailment—to characterize temporal matching without altering annual balances. Adaptive α(t) dispatch reduces spillage and curtailment relative to constant-α baselines, though ramp limits and minimum stable power bound realizable flexibility. Future work will replace the guide with measured sub-hourly forcing and price-aware dispatch to co-optimize grid exports, mining load, and thermal services under uncertainty. Consistent with ref. [89], the move to sub-hourly inputs is expected to materially improve hydrologic realism and dispatch fidelity.

Quantified mismatch and implications: The hourly guide reveals material timing gaps between waste-heat availability and greenhouse demand. Under constant-α baselines, heat coverage is seasonally variable, with spillage during mid-day surpluses and deficits during winter nights. Mismatch concentrates in colder nocturnal periods, while summer daytime shows persistent surplus. At α = 0.50, modest thermal storage and adaptive dispatch reduce deficit hours and improve coverage, though operational constraints bound achievable gains. These patterns indicate that mitigation and economics should reference Quse (useful heat) rather than gross Qcap, informing thermal sink and storage sizing (see also Section 2.3 and Figure A1).

Parameter uncertainty and derating (planning-data caveat): The key performance figures used here (e.g., SHP efficiency of 74.6% and PV specific yield of 1737.5 kWh·kW−1·year−1) are derived from planning documents and may not fully capture site-specific operating conditions. In particular, suspended-sediment abrasion in glacier-fed canals can depress turbine efficiency, while regional sandstorm/soiling can reduce the PV performance ratio by ≈5–10%. A simple O&M deduction is unlikely to encompass these degraders, creating a risk of modest overestimation of realizable output. To guard against this, we adopt conservative derating envelopes (Table A1)—covering hydro abrasive/hydraulic losses and PV soiling/temperature effects. This treatment tempers the interpretation of annual totals without altering this study’s qualitative conclusions regarding temporal matching, operability bounds, and mitigation pathways. Going forward, a monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) program—turbine efficiency testing with SSC/PSD sampling, and continuous PR/soiling and meteorological logging—will enable empirical refinement of Table A1 envelopes.

Applicability to non-glacier hydrological regimes and storage considerations: Precipitation-fed canals generally exhibit higher flow intermittency than glacier-melt systems, which reduces the firm SHP output available to the mining load. In such settings, flexible mining dispatch can absorb part of the variability, but modest battery storage (order-of-hours) may be warranted to bridge sub-hourly deficits and satisfy ramp/minimum-power constraints. A practical screening is to quantify the flow coefficient of variation (CV) and minimum assured flows: sites with CV ≲ 0.3 may operate without storage, whereas CV ≳ 0.5 typically benefit from ~2–4 h of equivalent mining-load coverage. The economic case is site-contingent, trading storage capex and cycling/degradation costs against improved uptime, reduced start–stop wear, potential time-of-use arbitrage (where applicable), and higher useful-heat (Quse) coverage. Consistent with our scope, we therefore treat storage as a sensitivity rather than a core assumption; future work will extend the framework with a parametric storage module to identify break-even sizes for precipitation-dominated canals.

Thermal sink sizing: The 50 m2 greenhouse validates the concept but leaves substantial heat underutilized. Scaling studies should consider (i) modular expansion of horticultural loads, (ii) cascading into aquaculture or drying processes, and (iii) seasonal storage via water tanks or phase-change materials. Ref. [90] show that waste-heat reuse from digital infrastructure, when matched with agricultural demand, provides a credible and scalable low-carbon pathway, supporting conservative sizing while highlighting expansion potential.

Economic volatility and alternatives: Mining revenue remains highly sensitive to BTC price, network hashrate, and policy shocks. Scenario envelopes and stress testing are required, together with operational guardrails (minimum merchant tranche, throttle/idle strategies, hedging). Evaluating alternative flexible loads—batch computing, AI inference/training with thermal recovery, desalination—could reduce reliance on a single industrial consumer while maintaining the heat-use pathway.

Social feasibility. Deployment depends on social acceptance: Concerns about noise, visual impacts, and e-waste from ASIC hardware may limit community support. Equity issues arise as grid exports generate public revenues while mining profits accrue to private investors, underscoring the need for transparent benefit-sharing mechanisms. Life-cycle assessment covering hardware replacement and inverter turnover is critical to extend footprint accounting beyond operational emissions.

Mitigation integrity and MRV: Ensuring integrity requires attention to grid emission factor provenance, diesel baseline realism, and metering accuracy. As host-country combined-margin values and Article 6 procedures evolve, periodic recalibration and transparent data-vintage rules will be needed. Ref. [91] show that blockchain-enabled digital MRV can enhance transparency and auditability in climate reporting, streamlining authorization, first transfer, and corresponding adjustment.

Replicability and climate robustness: Transferability depends on hydrology, tariff structures, and heat-sink availability. Coupling the framework with decadal glacier-mass-balance projections and climate-stress testing would improve bankability assessments and inform adaptive design measures.

Methodological extensions: Two priorities emerge: (i) codifying a standardized methodology for small-scale waste-heat applications in agriculture with clear baselines and auxiliary deductions; and (ii) releasing an open, versioned toolchain to enable third-party replication and meta-analysis across sites.

5. Conclusions

This study developed a guide model integrating technology, economics, and Article 6 mitigation accounting for a small hydropower–photovoltaic hybrid with flexible Bitcoin mining loads and waste-heat recovery for greenhouse heating. Operating on an annual-energy basis, the model allocates net generation between grid export and on-site use through a single parameter (α), enabling direct comparison across operating regimes.

Using planning evidence scaled to a representative 10 MW configuration in the Kyrgyz Republic, the analysis shows grid export remains the dominant source of emission reduction and revenue. Mixed-allocation cases retain this core climate value while adding operational optionality: on-site consumption absorbs energy during unfavorable export conditions without stranding production. Air-side heat recovery to a 50 m2 greenhouse yields small but verifiable reductions by displacing diesel heat and creates visible co-benefit pathways in food and thermal services.

Financially, the guide case reproduces positive but modest returns under merchant operation, with upside in mixed regimes driven by export tariff indexation, energy-limited mining value, and diesel displacement savings. The greenhouse’s economic role is secondary in magnitude but strategic for integrity and community acceptance.

For Article 6 readiness, componentized accounting is central: exported electricity maps to grid displacement under combined-margin approaches; the greenhouse maps to fuel-switch baselines with auxiliaries transparently deducted. Treating mining electricity as non-creditable avoids double claiming and simplifies authorization, monitoring, and corresponding adjustment.

Implementation guidance includes (i) securing PPA terms allowing for seasonal indexation and recognizing flexible-load operations; (ii) installing revenue-grade meters at switchyard, mining bus, and heat-recovery train; and (iii) formalizing community co-benefit pacts to document Sustainable Development contributions.

The model extends to glacier-fed canals and peri-urban corridors in Central Asia and to other flexible industrial loads accepting variable energy and returning useful heat. By unifying allocation, techno-economics, and mitigation integrity, it provides developers, regulators, and financiers with a common framework for evaluating hybrid, multi-service renewable projects. Future efforts should deepen temporal resolution, scale thermal sinks, and release an open toolchain for third-party replication across sites and sectors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-S.Y., T.-Y.K., J.-S.C., J.-S.K. and S.-J.L.; methodology, H.-S.Y., T.-Y.K., J.-S.C. and S.-J.L.; software, H.-S.Y. and S.-J.L.; validation, H.-S.Y., S.-J.L. and J.-S.K.; formal analysis, H.-S.Y. and S.-J.L.; investigation, H.-S.Y. and S.-J.L.; resources, H.-S.Y. and S.-J.L.; data curation, H.-S.Y. and S.-J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.-S.Y. and S.-J.L.; writing—review and editing, T.-Y.K., J.-S.C. and J.-S.K.; visualization, H.-S.Y. and S.-J.L.; supervision, J.-S.K.; project administration, J.-S.K.; funding acquisition, T.-Y.K., J.-S.C. and J.-S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS–2021–NR059478).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Financial & Techno-Economic Terms | |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditure |

| OPEX | Operating Expenditure |

| NPV | Net Present Value |

| IRR | Internal Rate of Return |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Energy |

| LCOH | Levelized Cost of Heat |

| PPA | Power Purchase Agreement |

| WACC | Weighted Average Cost of Capital |

| BTC | Bitcoin |

| ASIC | Application-Specific Integrated Circuit |

| Carbon Accounting Terms (CDM/Article 6) | |

| CDM | Clean Development Mechanism |

| SDM | Sustainable Development Mechanism |

| AMS | Approved Methodology (Small-scale) |

| ER | Emission Reductions |

| BE | Baseline Emissions |

| PE | Project Emissions |

| LE | Leakage |

| EF | Emission Factor |

| MRV | Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| COP | Conference of the Parties |

| Energy System & Technical Terms | |

| SHP | Small Hydropower |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| HX | Heat Exchanger |

| SCADA | Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| PSU | Power Supply Unit |

| NCV | Net Calorific Value |

| LHV | Lower Heating Value |

| HDD | Heating Degree Days |

| Cross-Domain Variables | |

| RCO2 | Carbon credit revenue (bridges CDM notation ER with financial USD/year) |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Temporal dynamics: hourly resolution guide analysis (Δt = 1 h; annual totals preserved). (a) Hourly generation profile over a full year (SHP, PV, total). (b) Monthly seasonal variation (average power by month). (c) 24 h diurnal pattern (daily average). (d) Intra-day dynamics—representative winter week. (e) Intra-day dynamics—representative summer week. (f) Power-allocation distribution at α = 0.5 (histogram of hourly export vs. mining power). (g) Waste-heat temporal availability (annualized). The hourly series is a profile-based reconstruction that exactly preserves the validated annual energies for the 10 MW guide case; it is used to illustrate temporal matching (generation vs. demand), potential spillage/curtailment, and operability effects (ramp/minimum-power/restart constraints), without altering the annual allocations reported in Section 3.1. Units: power in MW; heat in MWhth.

Figure A1.

Temporal dynamics: hourly resolution guide analysis (Δt = 1 h; annual totals preserved). (a) Hourly generation profile over a full year (SHP, PV, total). (b) Monthly seasonal variation (average power by month). (c) 24 h diurnal pattern (daily average). (d) Intra-day dynamics—representative winter week. (e) Intra-day dynamics—representative summer week. (f) Power-allocation distribution at α = 0.5 (histogram of hourly export vs. mining power). (g) Waste-heat temporal availability (annualized). The hourly series is a profile-based reconstruction that exactly preserves the validated annual energies for the 10 MW guide case; it is used to illustrate temporal matching (generation vs. demand), potential spillage/curtailment, and operability effects (ramp/minimum-power/restart constraints), without altering the annual allocations reported in Section 3.1. Units: power in MW; heat in MWhth.

Table A1.

Prior ranges for site-specific derating envelopes (used in sensitivity/uncertainty; to be updated post-commissioning via MRV).

Table A1.

Prior ranges for site-specific derating envelopes (used in sensitivity/uncertainty; to be updated post-commissioning via MRV).

| Factor (Resource) | Symbol | Prior Range | Basis/Notes (Condensed) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sediment/abrasion (SHP) | δsed | 3–12% | Glacier-fed canal; SSC/PSD↑, velocity↑ → runner wear | [92,93,94] |

| Hydraulic/fouling (SHP) | δhyd | 1–4% | Trashrack/biofouling/deposition → head loss | [93,94] |

| Availability (SHP) | δavl, SHP | 3–7% | O&M outages; small-plant availability ≳93% | [95] |

| Soiling/sandstorms (PV) | δsoil | 5–10% | Central Asia dust; cleaning interval dependent | [96,97] |

| Temperature (PV) | δtemp | 3–6% | Module temp coeff.; summer ambient | [96] |

References

- Kougias, I.; Szabó, S.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Huld, T.; Bódis, K. A Methodology for Optimization of the Complementarity between Small-Hydropower Plants and Solar PV Systems. Renew. Energy 2016, 87, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, D.; Cholewa, D.; Korzeń, A. Run-of-the-River Hydro-PV Battery Hybrid System as an Energy Supplier for Local Loads. Energies 2021, 14, 5160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Ming, B.; Cheng, L.; Yu, M.; San, M.; Jurasz, J. Modelling Long-Term Operational Dynamics of Grid-Connected Hydro- Photovoltaic Hybrid Systems. J. Energy Storage 2024, 99, 113403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Ahmar, M.; Jiang, Y.; AlAhmad, M. A Techno-Economic Assessment of Hybrid Energy Systems in Rural Pakistan. Energy 2021, 215, 119103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.K.; Alotaibi, M.A.; Das, P.; Islam, M.S.; Das, S.K.; Hossain, M.A. Feasibility and Techno-Economic Analysis of Stand-Alone and Grid-Connected PV/Wind/Diesel/Batt Hybrid Energy System: A Case Study. Energy Strategy Rev. 2021, 37, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murty, V.V.V.S.N.; Kumar, A. Optimal Energy Management and Techno-Economic Analysis in Microgrid with Hybrid Renewable Energy Sources. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2020, 8, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Q.; Algburi, S.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M. A Review of Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems: Solar and Wind-Powered Solutions: Challenges, Opportunities, and Policy Implications. Results Eng. 2023, 20, 101621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, T.K.; Mahmud, M.A.; Oo, A.M.T. Techno-Economic Feasibility of Stand-Alone Hybrid Energy Systems for a Remote Australian Community: Optimization and Sensitivity Analysis. Renew. Energy 2025, 241, 122286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubaarak, S.; Zhang, D.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Zaki, S.A.; Yuan, R.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M. Potential Techno-Economic Feasibility of Hybrid Energy Systems for Electrifying Various Consumers in Yemen. Sustainability 2020, 13, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figaj, R. Energy and Economic Sustainability of a Small-Scale Hybrid Renewable Energy System Powered by Biogas, Solar Energy, and Wind. Energies 2024, 17, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, A.; Weber, P.; Yates, A.J. Can Bitcoin Mining Increase Renewable Electricity Capacity? Resour. Energy Econ. 2023, 74, 101376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.; Connell, S.; Jones, B.; Porter, D.; Rudd, M. Leveraging Bitcoin Miners as Flexible Load Resources for Power System Stability and Efficiency. SSRN J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.T.; Hayibo, K.S.; Hafting, F.; Pearce, J. Economics of Open-Source Solar Photovoltaic Powered Cryptocurrency Mining. Ledger 2023, 8, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimi, A.; Pazuki, M.-M.; Salimi, M.; Amidpour, M. Renewable Energy and Cryptocurrency: A Dual Approach to Economic Viability and Environmental Sustainability. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgari, N.; McDonald, M.T.; Pearce, J.M. Energy Modeling and Techno-Economic Feasibility Analysis of Greenhouses for Tomato Cultivation Utilizing the Waste Heat of Cryptocurrency Miners. Energies 2023, 16, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emezirinwune, M.U.; Adejumobi, I.A.; Adebisi, O.I.; Akinboro, F.G. Synergizing Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems and Sustainable Agriculture for Rural Development in Nigeria. e-Prime Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2024, 7, 100492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natividad, L.E.; Benalcazar, P. Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems for Sustainable Rural Development: Perspectives and Challenges in Energy Systems Modeling. Energies 2023, 16, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 2023. Available online: https://Unfccc.Int/Process-and-Meetings/the-Paris-Agreement/Article6 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Pollack, K.; Bongaerts, J.C. Mathematical Model on the Integration of Renewable Energy in the Mining Industry. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2020, 14, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, C.; Devrim, Y. Design and Simulation of the PV/PEM Fuel Cell Based Hybrid Energy System Using MATLAB/Simulink for Greenhouse Application. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 22092–22106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]