1. Introduction

Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), requires the adoption of robust prosocial and philanthropic behaviors to address complex socioeconomic challenges globally. In the face of escalating development pressures, it has become increasingly important for individuals to cultivate prosocial and philanthropic tendencies that promote social well-being and collective resilience [

1,

2]. Charitable giving serves as a vital non-state mechanism for strengthening social sustainability and building community resilience, playing a central role in mitigating poverty and inequality [

2,

3]. Unlike state-led redistribution, charity channels resources directly from individuals to those in need, reflecting both moral obligation and voluntary solidarity. This is particularly salient in transitional economies such as Uzbekistan, where charitable efforts complement emerging welfare systems and foster a more equitable society.

In recent decades, charitable practices have evolved alongside rapid technological and socio-cultural change. Modern prosocial financial behavior now includes digital donations and structured community philanthropy, which coexist with deeply rooted traditions such as almsgiving and benevolent loans [

4]. These transformations underscore the need to analyze donation behavior within diverse cultural and institutional environments to ensure that philanthropic capital is effectively mobilized for sustainable outcomes [

5,

6]. Yet, existing theoretical frameworks—largely developed in Western contexts—may not fully explain how charitable behavior manifests in transitional economies, where formal charity institutions are still evolving and informal giving networks remain dominant.

Differences between traditional philanthropy and emerging donation models further challenge conventional explanations of giving behavior. Anonymity in online and collective religious giving reduces the influence of social image concerns that typically motivate public generosity [

7]. Moreover, individuals in emerging markets increasingly donate beyond their kinship networks, guided by shared moral values rather than geographic or familial proximity [

8]. Donors are also becoming more proactive—actively seeking causes to support—while the institutionalization of charity through NGOs and philanthropic funds introduces new forms of accountability, transparency, and trust-building [

3,

9]. Understanding how these social, cultural, and institutional changes reshape motivations to give is crucial for sustainable development policy.

Although global charitable giving continues to expand, resource mobilization remains uneven. Prior research has examined donation behavior through lenses such as social conformity [

10], religiosity [

11], and institutional trust [

12]. However, these models often overlook the unique intersections of religion, family, and community solidarity that shape giving in developing contexts [

13,

14]. In transitional economies like Uzbekistan—where traditional Islamic practices such as Zakat and Sadaqah reinforce social norms of generosity [

15], and new philanthropic and civil-society organizations increasingly complement state welfare programs [

16,

17]—existing theories may fail to capture the complex blend of spiritual, cultural, and structural drivers of giving.

Evidence from the World Giving Index 2024 places Uzbekistan 45th globally, with 61% of respondents reporting that they helped a stranger, 52% reporting donating money, and 18% reporting volunteering in the previous month. These patterns suggest strong civic potential, yet the determinants of giving remain insufficiently understood. Rising incomes, demographic change, and digital platforms are reshaping donation patterns, but recent studies show that economic capacity alone cannot explain charitable behavior. Factors such as subjective well-being, perceived behavioral control, and moral duty appear to mediate giving decisions [

18,

19]. This underscores the need for an integrated theoretical framework combining socio-economic, normative, and psychological dimensions—especially as Uzbekistan transitions toward an upper-middle-income economy within Central Asia. Uzbekistan is a transition economy in Central Asia with a population of more than 37 million. The Government of Uzbekistan has implemented ambitious socio-economic reforms since 2017 which liberalized economy, fostered private sector development, and more importantly significantly increased the real incomes of population and reduced poverty. This further highlights the need to study socio-economic predictors of charitable giving and social capital as it may have untapped potential to contribute to sustainable economic development in the long run.

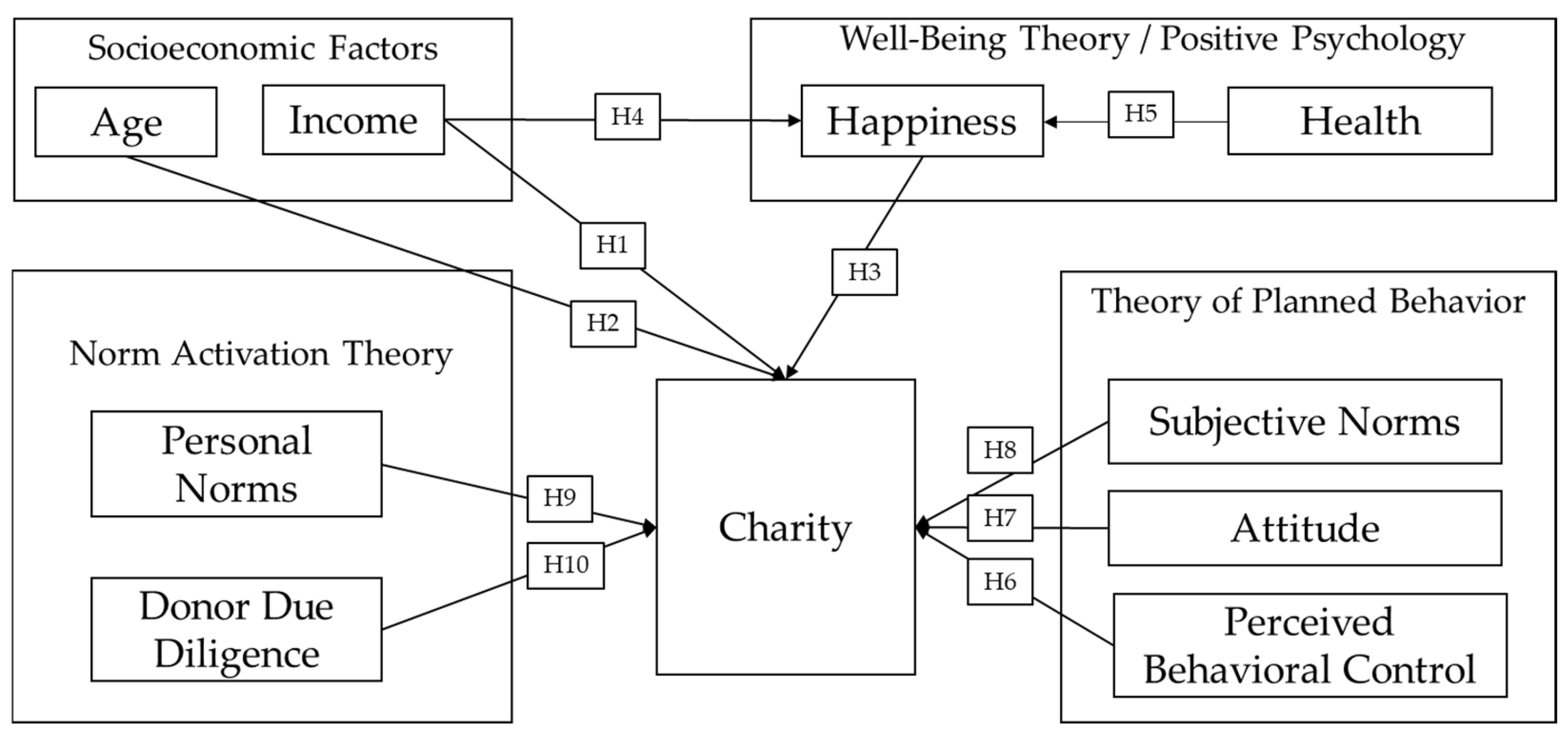

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) provides a widely used framework for explaining prosocial intentions through attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [

20,

21,

22]. Yet, TPB alone may overlook deeper moral and contextual motivations. The Norm Activation Theory (NAT) complements TPB by emphasizing internalized moral norms as key drivers of altruistic behavior [

23]. Similarly, the Well-Being Theory (WBT) highlights how happiness and health promote prosocial engagement [

24,

25], while donor trust—rooted in institutional and relationship-marketing perspectives—reduces uncertainty and strengthens giving intentions [

12].

This study contributes to the literature in three ways. First, it integrates TPB, NAT, and WBT [

26] into a single framework to analyze charitable behavior—representing one of the first systematic applications of this model in Uzbekistan. Second, it examines how socioeconomic factors such as income and age interact with psychological and normative constructs to shape giving. Third, it offers practical insights for policymakers, NGOs, and faith-based organizations to enhance philanthropic engagement and strengthen social sustainability in transitional economies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundation

Ajzen’s [

27] Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) remains a central framework for analyzing the psychological mechanisms underlying charitable giving and other forms of prosocial behavior. It posits that intention—the immediate antecedent of behavior—is shaped by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (PBC) [

18,

27]. Attitude reflects an individual’s evaluation of donating, subjective norm captures perceived social pressure, and PBC represents perceived ease of giving. Empirical studies frequently confirm that these factors jointly influence donation intentions, which in turn predict actual giving [

10].

In charitable contexts, TPB has provided valuable insights into how personal evaluations, social expectations, and perceived abilities interact to shape generosity. Meta-reviews highlight those attitudes and norms that often exert strong effects, while PBC captures perceived barriers and enablers [

28]. Yet, TPB is not without limitations. Several recent studies find that its constructs do not always predict charitable outcomes consistently, with attitude or norms becoming insignificant under conditions of institutional distrust, cultural variation, or resource constraints [

29,

30]. This suggests that the classic TPB may be less applicable in transitional economies, where informal giving, low trust in institutions, and cultural norms complicate behavioral prediction.

Extensions of TPB have therefore emphasized additional factors. Norm Activation Theory (NAT) highlights the influence of personal moral norms, or internalized duties, which can operate independently of external pressures [

13,

19]. Building on this perspective, well-being theory highlights that individuals with higher levels of happiness and health are more inclined toward prosocial engagement, reflecting the “feel-good, do-good” phenomenon [

20,

21]. Meanwhile, donor trust and due diligence—grounded in transparency and accountability—have emerged as increasingly important in shaping charitable choices [

5,

9].

The Uzbek context underscores the need for this extended model. Islamic giving practices such as Zakat, Sadaqah, and Qarzi Hasan embed both subjective and personal norms, while limited trust in formal charities may heighten the importance of donor due diligence. Socioeconomic resources such as income and health condition further constrain or enable giving, while happiness and perceived control influence whether these resources are translated into action [

31].

Building on these insights, this study adopts an extended TPB framework enriched by NAT, well-being perspectives, and trust-based constructs. This multidimensional approach not only accommodates contradictions in the literature but also provides a culturally sensitive framework for analyzing the determinants of charitable giving in Uzbekistan.

2.2. Research Hypotheses

2.2.1. Socioeconomic/Demographic Perspectives

Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics are widely recognized as fundamental determinants of charitable giving, with income and age playing particularly important roles. Higher income provides greater disposable resources, lowering the economic “cost” of donating and enabling more frequent or larger gifts. Empirical evidence generally confirms a positive association between income and charitable contributions: wealthier individuals are more likely to give and tend to donate larger amounts [

28,

32]. Charitable donations can therefore be partly conceptualized as economic behaviors shaped by financial capacity, since resource-rich donors face fewer constraints in acting on altruistic intentions [

32]. Yet, the income–giving link is not uniform. Geys and Sørensen [

33] demonstrate that only large windfall shocks increase giving, while small income changes have little effect. Likewise, Jackson [

34] shows that the proportion of income donated decreases when earning requires higher effort, and volatility in income patterns can further alter giving. Moreover, when donors perceive inefficiencies or high overhead costs in charitable organizations, they may reduce contributions regardless of income levels. Chlaß et al. [

35] highlight how the perceived “price” of charitable output—reflecting hidden costs in intermediaries—can erode the positive effect of financial capacity on giving. Taken together, these findings reveal that income effects on philanthropy are conditional, nonlinear, and mediated by institutional or psychological considerations.

Age is another salient demographic determinant. Charitable giving tends to rise with age, as individuals accumulate resources, strengthen community ties, and develop a heightened sense of social responsibility [

28,

36]. Older adults often display stronger philanthropic tendencies due to life-cycle effects such as financial stability, empathy, and long-term community engagement. Indeed, several studies confirm a positive association between age and donation frequency or amount, with middle-aged and older individuals more likely to contribute than younger adults [

36,

37]. However, these effects are not universal. Best and Freund [

37] for example, show that when the measure of generosity is non-monetary (e.g., donating small amounts of time), older adults were not consistently more giving than their younger counterparts [

38]. This indicates that age effects may depend on the domain of giving, suggesting that demographic influences, like income effects, are more complex and context-specific than often assumed. Building on the preceding discussion, the following hypothesis is advanced for empirical validation:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Income has a positive effect on Charity.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Age has a significant effect on Charity.

2.2.2. Well-Being Theory/Positive Psychology

Positive psychology and well-being theories demonstrate that happier individuals are more prone to prosocial behaviors, with subjective well-being potentially mediating the impact of other factors on generosity. The “feel-good, do-good” phenomenon is well documented: individuals experiencing positive affect and life satisfaction often show greater willingness to help others [

21]. Happiness, as both a cognitive and emotional component of well-being, is believed to foster empathy, social trust, and a sense of reward from altruistic acts, thereby encouraging charitable giving. Empirical evidence supports this link: surveys and longitudinal research indicate that people with higher self-reported happiness or life satisfaction are more likely to volunteer and donate to charity [

20,

21]. Dunn et al. [

20] further demonstrated experimentally that spending money on others increases one’s happiness, suggesting a reciprocal relationship between generosity and well-being.

However, findings remain mixed. Köbrich and Schobin [

39] induced positive incidental emotions and found no significant overall effect on donation levels, although they observed changes in allocation among charities. Similarly, Krasnozhon and Levendis [

40] showed that happiness is more strongly associated with volunteering than with monetary giving. After accounting for socioeconomic variables such as income, unemployment, race, and gender, happiness appears only loosely connected with both volunteering and charitable donations. Collectively, these findings imply that while happiness is often theorized as a robust driver of prosocial behavior, its influence on financial donations is more nuanced and context-dependent, warranting further investigation.

Well-being theory also provides evidence that happiness may serve as an intervening mechanism between personal conditions and prosocial actions. With respect to financial status, prior research indicates that income can enhance life satisfaction up to a threshold [

41]. Higher income improves evaluations of life and reduces stress from basic needs, contributing to overall happiness. In turn, happiness encourages charitable behavior. Thus, part of income’s effect on giving may be mediated through enhanced happiness: individuals donate more not only because they can (economic ability), but also because they feel better off and derive joy from giving. This mediating pathway aligns with positive psychology’s emphasis that generosity is most meaningful when it enhances well-being [

20].

Health operates in a similar manner. As a core component of well-being, good health is strongly associated with greater happiness and life satisfaction, while poor health undermines emotional well-being [

42] (Improved self-perceived health and mental wellness have been shown to significantly enhance happiness [

43]). Healthier, happier individuals often possess greater capacity and energy to engage in prosocial activities [

21]. In this sense, happiness can be seen as the psychological benefit of health that motivates generosity, linking physical well-being with charitable engagement. From the arguments outlined above, the subsequent hypothesis is formulated for empirical testing:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Happiness has a positive effect on Charity.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Happiness mediates the relationship between Income and Charity.

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Happiness mediates the relationship between Health and Charity.

2.2.3. Theory of Planned Behavior

Perceived behavioral control (PBC) refers to one’s perception of the ease or difficulty of donating, often linked to confidence in financial ability and opportunity [

27]. Generally, higher PBC is expected to increase participation, as individuals who feel capable face fewer barriers. Prior research confirms its positive role in predicting donation intentions [

10] and prosocial actions like green volunteering [

44]. Conversely, findings are mixed: Susanto [

30] reported a non-significant effect of opportunity to donate on PBC, while Kim and Han [

29] showed that negative nonprofit reputations nullify its influence. These results reveal that although PBC can facilitate giving, its impact weakens under conditions of limited opportunity or mistrust. Nonetheless, it is still reasonable to assume that individuals with greater financial and practical control are more likely to donate [

45].

Attitude in the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) refers to an individual’s overall evaluation of donating—whether it is seen as good, beneficial, or worthwhile [

27]. Generally, positive attitudes are expected to strengthen intentions and actual giving behavior. Prior research supports this: attitude has been shown to significantly predict donation intentions in charitable giving [

10] and online crowdfunding contexts [

45]. Nevertheless, more recent evidence highlights important limitations. Kim and Han [

29] found that when nonprofit reputation was negative, the effect of attitude on donation intention became insignificant. Similarly, Susanto [

30] reported that attitude was not always a robust predictor when other contextual factors, such as opportunity to donate, were included. Balaskas et al. [

46] also noted that while attitude correlated with intentions, it did not reliably predict actual giving behavior. It can be inferred from these findings that while attitudes generally facilitate charitable engagement, their influence may weaken under reputational, institutional, or contextual constraints.

Subjective norm refers to the perceived social pressure from important others—such as family, peers, or religious leaders—to engage in a behavior [

27]. In the context of charity, it reflects the extent to which giving is seen as socially expected or endorsed. Positive subjective norms are generally assumed to strengthen intentions to donate, as individuals tend to conform when generosity is viewed as desirable in their community [

10]. Prior research shows that social approval and religious expectations can motivate giving, especially in collectivist contexts [

22]. Li et al. [

47] similarly found that both subjective and moral norms predicted donation intentions, though moral norms had a stronger effect. Alternatively, findings are not universally consistent. Gugenishvili [

48] highlighted that misalignment between injunctive and descriptive norms can reduce their predictive power, while Pérez y Pérez and Egea [

49] showed that descriptive norms were non-significant, and injunctive norms explained only a small share of variance. These results demonstrate that the influence of subjective norms is context-dependent and may weaken in settings where institutional trust is low or informal giving dominates. Based on the theoretical reasoning presented, this study proposes the following hypothesis for empirical assessment:

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Perceived Behavioral Control positively influences Charity.

Hypothesis 7 (H7). Attitude toward charity positively influences Charity.

Hypothesis 8 (H8). Subjective Norm positively influences Charity.

2.2.4. Norm Activation Theory

Personal norms represent an internalized moral duty to act, reflecting one’s ethical obligation to help others [

19]. In charitable contexts, this manifests as a belief that one ought to donate to support those in need. Many studies confirm that moral obligations often drive giving behavior beyond external social expectations. For example, Li et al. [

47] found moral norms to be a stronger predictor of online donation intention than subjective norms in China, while Bekkers and Ottoni-Wilhelm [

50] identified a “principle of care” as central to donation decisions. In Islamic contexts, obligations such as zakat or sadaqah reinforce these norms and sustain generosity [

13]. Yet, recent evidence suggests that personal norms may not always reliably translate into charitable action. Veseli et al. [

51] showed that moral norms weakened among both donors and non-donors during the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting their instability in times of crisis, whereas in some collectivist societies, social pressure (subjective norm) may dominate [

52]. In addition, Andersson et al. [

53] found that when individuals avoided normative cues, donation behavior declined, pointing to the fact that normative influences can lose strength or even backfire depending on context. These findings indicate that while personal norms often predict prosocial behavior, their effect is not universal and may diminish under certain social or economic conditions.

Donor due diligence refers to the extent to which individuals seek information and verify a charity’s trustworthiness, transparency, and effectiveness before donating. It captures how much potential donors evaluate an organization’s reputation and impact as part of their decision-making process. Theoretically, greater due diligence should enhance giving because informed donors feel more confident that their contributions will be used appropriately, reducing fears of fraud or inefficiency and strengthening trust [

5,

9]. This perspective aligns with the growing emphasis on “informed giving,” where modern donors actively examine accountability, results, and fund allocation before deciding to contribute [

54]. However, recent evidence establishes that due diligence does not always translate into higher donations. Hung et al. [

55] show that donors are negatively sensitive to the “price of giving,” with high overhead or fundraising costs reducing donation levels, which may weaken the positive effect of transparency. Similarly, Ünal and Aydın [

56] report that transparency did not significantly predict donation intention in their study, indicating that accountability cues are not universally influential. These findings imply that while due diligence can build trust and increase donor confidence, its effect is context-dependent and may be attenuated when concerns about efficiency or costs dominate donor perceptions. Drawing on the foregoing discussion, the subsequent hypothesis is introduced for validation through data analysis:

Hypothesis 9 (H9). Personal Norm positively influences Charity.

Hypothesis 10 (H10). Donor Due Diligence positively influences Charity.

Figure 1 presents the integrated framework, where charity is influenced by socio-economic (income, age), well-being (happiness, health), TPB constructs (PBC, attitude, subjective norm), and normative factors (personal norm, donor due diligence). The following section outlines the methodology used to test this model (

Supplementary Materials).

3. Research Method

3.1. Sample Collection

The research focused on individuals aged 16 to 80 years, representing both urban and semi-rural populations from Tashkent city and the Sirdarya region of Uzbekistan. Data were collected between 5 July and 30 August 2025, using a structured questionnaire administered via Google Forms. Surveys were distributed in public gathering places such as supermarkets and national parks, which attract both urban and rural residents, thereby ensuring exposure to a diverse pool of respondents. While the questionnaire did not explicitly record whether participants lived in urban or rural areas, the sampling frame covered two distinct contexts: 193 responses were obtained from Tashkent city, representing an urban setting, and 155 from the Sirdarya region, which is predominantly rural. In total, 348 valid responses were retained for analysis after data cleaning. Participation was entirely voluntary, with informed consent obtained from all respondents, who were briefed on the study’s objectives prior to completing the survey.

An a priori power analysis was performed using G*Power 3.1 (Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany) to estimate the minimum sample size required for adequate statistical power in the structural model. Following the guidelines of Faul et al. [

57], the number of predictors was determined by identifying the most complex regression equation in the model—specifically, the endogenous construct with the greatest number of direct predictors. In this study, Charity served as the dependent (endogenous) variable and was predicted by eight independent variables: Income, Age, Happiness, Perceived Behavioral Control, Attitude, Subjective Norm, Personal Norm, and Donor Due Diligence. Based on this specification, an a priori power analysis was performed with eight predictors, a medium effect size f

2 = 0.15, a significance level of α = 0.05, and a statistical power of 0.95. The results of the a priori power analysis indicated that a minimum of 160 observations was required to achieve adequate statistical power. To minimize sampling bias and enhance model stability, the study deliberately targeted a larger sample of over 300 respondents. A total of 362 responses were initially collected; however, after data screening and the removal of incomplete or inconsistent cases, 348 valid responses were retained for analysis. This final sample was used to test the hypothesized relationships among the study constructs and to assess their effects on Charity within the structural model.

3.2. Measurement

The dependent variable in this study is Charity, measured as a binary single-item indicator (1 = Yes, 0 = No) reflecting whether respondents reported engaging in charitable giving. Binary outcomes of this type are common in behavioral research when the construct represents a concrete and observable action rather than a latent psychological trait. Prior methodological work demonstrates that PLS-SEM can accommodate binary single-item variables under appropriate conditions [

58,

59]. Given the unambiguous operationalization of charitable giving, its representation as a single yes/no item is both theoretically justified and empirically feasible. Attitude toward charity was conceptualized as an individual’s evaluative orientation toward prosocial giving, consistent with the Theory of Planned Behavior [

27]. It was assessed using six items: three adapted from Manzur and Olavarrieta [

60] two from Balaskas et al. [

46] and one from Weiss-Sidi and Riemer [

61]. This scale was chosen for its strong theoretical grounding and ability to capture multidimensional aspects of attitudes, including moral duty, self-identity, intrinsic motivation, and emotional satisfaction. Subjective norms reflect perceived social pressure or expectations regarding charitable behavior. This construct was measured with two items: one adapted from Chen et al. [

45] and one from France et al. [

62]. Together, these items capture both religious and value-based normative expectations. Personal norms were measured through four items reflecting internalized moral obligations and responsibilities to help others. Two items were adapted from Bekkers and Ottoni–Wilhelm [

50] and two from Ai and Rosenthal [

63]. This measure was selected for its capacity to capture the moral dimension of prosocial behavior beyond external pressures. Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) was assessed using two items designed in line with Ajzen [

64] focusing on confidence in personal financial management and perceived sufficiency of resources to support others. This operationalization is consistent with prior applications [

4,

65]. Health was measured with two items: one adapted from Caramenti and Castiglioni [

43] assessing overall health status, and another from Tinajero-Chávez et al. [

66] evaluating satisfaction with personal health. For all constructs—including Charity, Happiness, Attitude, Subjective Norm, Personal Norm, PBC, Health, and Donor Due Diligence—special attention was given to ensuring cultural and contextual fit for the Uzbek population. Scales were carefully reviewed and, where necessary, linguistically and conceptually adapted to reflect the socio-economic realities and behavioral tendencies of the setting.

All final measurement items are listed in

Appendix A. Except for binary Charity; all items were measured using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

3.3. Normality Assumption

Multivariate normality was assessed using Mardia’s skewness and kurtosis tests, implemented through the Peng and Lai [

67] online tool. The results indicated significant departures from multivariate normality, as both skewness and kurtosis values exceeded recommended thresholds. These deviations confirm that the data violate the assumption of multivariate normality, thereby supporting the use of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). This method is well-suited for non-normally distributed data and small-to-moderate sample sizes, offering robust parameter estimates under such conditions [

68].

3.4. Data Processing and Analysis

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed to estimate the hypothesized causal relationships among latent constructs [

68]. Compared with covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM), PLS-SEM provides distinct advantages when dealing with complex models involving multiple constructs, mediating effects, and non-normal data distributions [

67]. Given the sample size of 348 respondents, which exceeds the commonly recommended minimum threshold of 100 observations, the application of PLS-SEM using SmartPLS 4.1.1.5 software was deemed appropriate for evaluating both the measurement and structural components of the model.

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Participant Characteristics

Table 1 provides a summary of the demographic characteristics of the 348 valid respondents. Gender distribution was relatively balanced, with 51.7% male and 48.3% female participants, indicating that both genders were adequately represented in the sample. Respondents were grouped into four age categories. The largest share fell within the 16–29 group (46.8%), followed by those aged 30–44 (42.8%). In contrast, only 9.5% of respondents were between 45 and 59 years, and less than 1% were aged 60 and above. This distribution suggests that the survey predominantly captured the perspectives of younger and middle-aged individuals, who are more active in economic and social spheres.

In terms of educational attainment, the majority of respondents (52.9%) held a bachelor’s degree, while 20.7% possessed a master’s degree and 10.6% had postgraduate qualifications, indicating a relatively well-educated sample population. A smaller portion had completed college (13.2%) or secondary school (2.6%). This pattern reflects a highly educated sample.

Regional distribution showed that 55.5% of participants were from Tashkent, whereas 44.5% resided in the Sirdarya region, providing a balanced geographic representation. With respect to income, about 17.8% earned less than 2 million UZS monthly, while the majority clustered between 2.1 and 10 million UZS. A smaller segment reported higher income levels above 15 million UZS.

4.2. Reliability and Validity

In structural equation modeling, constructs are typically measured with multiple items to ensure internal consistency and convergent validity. However, in some contexts, single-item indicators can be both theoretically defensible and empirically appropriate. In this study, Charity, Age, Income, Donor Due Diligence (DDD), and Happiness were modeled as single indicators.

Single-item measures offer practical advantages, such as parsimony, shorter survey length, and reduced respondent fatigue, thereby minimizing careless responses and random error [

69,

70]. Their appropriateness depends on the construct: they are suitable when the concept is unidimensional, concrete, and narrowly defined [

71,

72]. In this study, constructs like Age and Income are objective and directly observable, while Charity was a binary yes/no behavior, all of which meet these criteria [

58].

The justification for Charity, Happiness, and DDD relies on their classification as “doubly concrete” measures—specific in both object and evaluation—minimizing interpretive ambiguity [

72]. For instance, Charity was measured with a binary yes/no item, a valid approach supported by recent advances such as Binary PLS Regression [

59]. Similarly, Happiness was assessed on a 1–10 scale, consistent with findings from Lukoševičiūtė et al. [

73,

74] who demonstrated the convergent validity of single-item happiness measures across diverse populations. Donor Due Diligence was captured through a 1–5 Likert item asking respondents about their ability to identify trustworthy organizations. Prior work shows that donors actively verify trustworthiness and transparency before giving [

54] supporting the use of a focused, behavior-proximal indicator.

A recognized limitation of single-item measures is the inability to compute internal consistency metrics (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha, Composite Reliability). Reliability must instead be inferred from conceptual clarity, face validity, and prior validation evidence [

69,

75]. In this study, the chosen single items were highly focused, thereby reducing error risk and maximizing predictive validity within the PLS-SEM framework.

Finally, Personal Norms were initially modeled with four indicators. During model assessment, multicollinearity diagnostics indicated that one item exceeded the recommended VIF threshold (>5.0). This item was removed, resulting in a refined three-item construct with adequate reliability and validity, ensuring both statistical robustness and theoretical coherence. The removed item is documented in

Appendix A.2.

The evaluation of the measurement model began with an assessment of construct reliability, indicator reliability, and convergent validity. Construct reliability was assessed using Composite Reliability (CR), with values above 0.70 indicating satisfactory internal consistency [

76]. As shown in

Table 2, all constructs exceeded this threshold, ranging from 0.837 for Attitude to 0.959 for Personal Norm, with the exception of Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC), which fell below 0.70. While this reveals limited reliability, such outcomes are not uncommon for constructs measured with only two items [

58]. Theoretically, the two items capture distinct but complementary aspects of financial confidence and perceived ability to assist others, supporting the decision to retain the construct. In line with Hair et al. [

77] single- or two-item constructs may remain in PLS-SEM models if they are conceptually essential.

Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) values were also examined. All constructs surpassed the 0.60 threshold, ranging from 0.697 to 0.938, except for PBC, which fell below this level. As previous studies have noted, CA tends to underestimate reliability in two-item constructs [

58,

77]. Despite the lower reliability estimates, PBC was retained given its central role in the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and its empirical relevance. Dillon–Goldstein’s rho (DG rho) was used as an alternative reliability coefficient, and all constructs demonstrated values above the recommended 0.60 benchmark, further supporting adequate internal consistency. Convergent validity was assessed using the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), with values above 0.50 indicating sufficient variance explained by the construct relative to error [

78]. Most constructs met this criterion. The only exception was Attitude, with an AVE of 0.465. Although slightly below the conventional threshold, Attitude was retained due to its strong theoretical grounding and contextual significance in predicting charitable behavior in Uzbekistan. Prior research points to the conclusion that AVE values marginally below 0.50 can still be acceptable when other indicators, such as CR and factor loadings, demonstrate adequate psychometric properties [

77]. In this case, Attitude achieved a CR of 0.837, confirming satisfactory internal consistency.

Cumulatively, these results indicate that the majority of constructs achieved robust reliability and validity. Although PBC and Attitude showed marginal weaknesses, both were retained for their theoretical importance, ensuring that the model preserves conceptual completeness while maintaining an acceptable level of measurement rigor.

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) analysis showed that all values were below the recommended threshold of 5, indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern. To further assess single-source bias, a full collinearity test was conducted following Kock [

79] where all constructs were regressed on a common method factor. Again, VIF values remained below 5, confirming the absence of substantial common method bias.

Discriminant validity was evaluated using two complementary approaches: the cross-loading method and the Fornell–Larcker criterion. Cross-loading analysis confirmed that each indicator loaded more strongly on its intended construct than on any other, consistent with Hair et al. [

76]. The Fornell–Larcker test showed that the square root of each construct’s AVE exceeded its correlations with other constructs, providing additional evidence of discriminant validity. Together, these results confirm that all constructs are empirically distinct. Detailed results are reported in

Table 3 (Fornell–Larcker criterion) and

Table 4 (cross-loadings). To address potential endogeneity, Gaussian Copula (GC) procedures were applied to the structural model, as recommended by Hair et al. [

80]. Two GC tests were performed: one for the Happiness → Charity path and another for the Donor Due Diligence → Charity path. The GC term for Happiness was not significant (

p > 0.05), indicating no endogeneity concern. For Donor Due Diligence, the GC term was marginally significant (

p = 0.08), suggesting weak evidence of potential endogeneity, though below conventional significance thresholds. This implies that, overall, endogeneity does not substantially bias the model’s estimates, but future research with instrumental variable approaches or larger samples may help validate the DDD–Charity relationship. Synthesizing these findings, these analyses show that the model is robust: free from multicollinearity and common method bias, demonstrates satisfactory discriminant validity, and is largely unaffected by endogeneity.

4.3. Structural Model

Following the guidelines of Hair et al. [

77] the coefficient of determination (R

2) was employed to assess the explanatory power of the structural model. For the primary endogenous construct, Charity, the R

2 value was 0.154, indicating that 15.4% of the variance in charitable behavior was explained by the proposed predictors. This reflects a modest but meaningful level of explanatory power, which is consistent with the complexity and context-dependent nature of prosocial behavior. The mediator construct, Happiness, achieved an R

2 of 0.283, suggesting that 28.3% of its variance was explained by its antecedent variables, thereby representing a noteworthy degree of explanatory strength. Although the overall explained variance remains relatively limited, such values are common in behavioral and social science research, where human decision-making is influenced by numerous unobserved factors. Consequently, the model can be considered theoretically sound and empirically acceptable, especially given the statistical significance observed for several hypothesized paths. In summary, these findings demonstrate that the model explains meaningful variance in both subjective well-being and charitable behavior, while also highlighting the need for future studies to incorporate additional contextual and cultural determinants of giving.

The significance of the hypothesized relationships was examined using a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples and a no-sign-change option. The estimated path coefficients (β-values) for each relationship are presented in

Figure 2 and

Table 5. Overall, approximately half of the proposed hypotheses were empirically supported at the 5% significance level. The analysis revealed that several constructs significantly influenced Charity. Income had a positive and significant effect, indicating that individuals with higher income levels were more likely to engage in charitable giving. Age also showed a significant positive relationship with Charity, revealing that older respondents were more inclined to donate. Similarly, Happiness was found to positively influence Charity, confirming the role of subjective well-being as a driver of prosocial behavior. Interestingly, Personal Norms had a statistically significant but negative effect on Charity. This unexpected finding suggests that stronger self-imposed obligations may not necessarily translate into actual charitable actions, possibly reflecting context-specific cultural or economic constraints. Other direct paths were not supported. Perceived Behavioral Control, Attitude, Subjective Norms, and Donor Due Diligence were all statistically insignificant, indicating that these constructs did not play a decisive role in predicting charitable behavior within this sample.

The mediation analysis provided partial support for indirect relationships. The mediating effect of Happiness between Health and Charity was significant, implying that healthier individuals tend to be happier, which in turn fosters greater charitable activity. Conversely, the mediating effect of Happiness in the relationship between Income and Charity was not significant at the 5% level, though it showed a marginal effect at the 10% threshold. Approximately half of the hypothesized relationships were empirically supported. The findings highlight the relevance of socio-economic (Income, Age), psychological (Happiness), and normative (Personal Norms) factors in explaining charitable giving, while traditional TPB predictors (Attitude, Subjective Norms, and Perceived Behavioral Control) and Donor Due Diligence did not demonstrate significance in this context.

5. Discussion

It is important to interpret the supported relationships within the constraints of our cross-sectional design. While the structural model specifies directional pathways grounded in established psychological theories (e.g., Happiness → Charity), the data permit only inferences about associations and predictive relationships, not definitive causal effects. For example, although H3 and H5 were supported—indicating that happiness is positively associated with charitable giving and mediates the health–charity relationship—the reverse pathway (e.g., giving fostering happiness) remains plausible. Thus, the positive links identified here should be understood as predictive associations consistent with the hypothesized mechanisms, rather than conclusive evidence of temporal causality.

Against this backdrop, the study aimed to examine charitable giving through a multifaceted lens by integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), Norm Activation Theory (NAT), and well-being perspectives. The findings provide a nuanced picture: certain results confirm theoretical expectations, whereas others challenge conventional assumptions. The following sections interpret these outcomes within each framework, highlighting how the evidence supports, extends, or contradicts existing models, and consider broader implications for poverty alleviation, social well-being, and the sustainability agenda.

5.1. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) posits that charitable giving should be shaped by three proximal determinants—attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [

23,

27]. Contrary to this expectation, our analysis revealed that none of these factors significantly predicted donation behavior. Favorable attitudes toward charity, perceived social pressure to give, and confidence in one’s ability to donate did not translate into higher giving. This diverges from much of the TPB literature, where these cognitions are typically associated with charitable intentions and, to a lesser extent, behavior [

23]. Our findings therefore question the generalizability of TPB in transitional economies and highlight the limited explanatory power of psychosocial predictors in this case. The null results for attitude (H7), subjective norm (H8), and perceived behavioral control (H6) resonate with some earlier studies. Smith and McSweeney [

10] found that while attitudes and control beliefs predicted intentions, their direct influence on actual donations weakened once moral norms or past behavior were included. Likewise, van der Linden [

81] reported that incorporating moral norms into TPB can attenuate the predictive role of attitude and subjective norms. Our findings are consistent with this dynamic: once internalized moral obligations and well-being factors were considered, traditional TPB drivers lost significance.

Several explanations are plausible. Culturally, charitable giving in Uzbekistan often takes the form of informal, values-driven practices (e.g., zakat, sadaqah, or private transfers), which may reduce the salience of peer pressure or generalized positive attitudes. Donations are often discreet rather than publicly signaled, limiting the influence of subjective norms. Similarly, perceived behavioral control may have shown little effect because respondents already reported relatively few barriers to modest giving, leaving insufficient variance for prediction. Methodologically, TPB specifies that attitudes, norms, and control act primarily through behavioral intention, which we did not measure. Their absence in direct paths to behavior may therefore reflect the model’s structure rather than the true absence of influence. The aggregate results indicate that these results extend prior evidence that TPB alone provides an incomplete explanation for charitable behavior, particularly in cultural contexts where moral duty and affective factors outweigh cognitive appraisals. This reveals that interventions relying on attitudinal change or normative appeals (“everyone is donating”) may be less effective in Uzbekistan compared to strategies emphasizing personal values, moral obligations, or well-being benefits.

5.2. Norm Activation Theory (NAT)

Norm Activation Theory (NAT) emphasizes personal moral norms as central drivers of altruistic action, predicting that stronger internalized obligations should increase charitable behavior [

19,

82]. In contrast to this expectation, our results showed that personal norms were significant, but negatively associated with charitable giving. This unexpected finding challenges NAT’s standard prediction and prior evidence where moral norms consistently act as strong positive predictors [

23,

83]. Rather than implying that moral obligations discourage generosity, several explanations merit consideration. First, the negative sign may reflect a statistical suppression effect or multicollinearity, as personal norms correlate with other psychosocial factors. Once entered together, the residual variance may capture respondents who feel strong obligations but nevertheless fail to donate, yielding an inverse relationship. Second, cultural and economic dynamics in Uzbekistan may drive this gap between aspiration and action. Many individuals experience strong religious or social pressure to give (e.g., zakat, sadaqah), yet resource constraints limit actual donations. Such respondents report high personal norms but low giving, producing a paradoxical correlation. Furthermore, the unexpected negative effect of moral norms on giving may reflect methodological issues. Self-reported measures of morality are prone to social desirability bias, especially in cultures where altruism is highly valued. Respondents may overstate their moral duty while limited by real constraints like income or time, creating a mismatch between belief and action. Moreover, questionaries’ respondents may rely on memory and not on what they are really experiencing [

52]. Third, measurement and psychological nuances may play a role: individuals with very high obligations might perceive their contributions as insufficient, leading them to rate their norms highly while underreporting their giving. Collectively, these explanations suggest that the negative coefficient is more likely an artifact of local context or model specification than a genuine reversal of NAT. Importantly, personal norms still emerged as significant, underscoring NAT’s argument that internalized duty matters more than external subjective norms, which were null in our model. The finding highlights the need for further culturally sensitive research, possibly using qualitative methods, to unpack how economic constraints and moral expectations interact in transitional economies.

Turning to Donor Due Diligence (DDD), Hypothesis 10 was not supported, as the path from DDD to charity was statistically insignificant (β = 0.141, t = 1.147). This result should not be seen as a failure of measurement quality but rather as a contextual null effect. In Western settings, transparency, information-seeking, and institutional trust are critical to donation decisions [

54]. By contrast, in Uzbekistan, philanthropy often operates through informal trust networks, religious teachings, and community solidarity, reducing the role of formal due diligence in donation behavior. In this environment, individuals may donate based on personal familiarity with beneficiaries or cultural duty rather than verifying organizational efficiency. The robustness of this conclusion is reinforced by the Gaussian Copula analysis, which showed only marginal evidence of endogeneity (

p = 0.08), which may imply that the null effect reflects a genuine theoretical finding rather than bias. Thus, while donor diligence is well-established as a predictor in formalized philanthropic markets, its predictive role may be muted in transitional economies where informal trust dominates decision-making.

5.3. Well-Being Theory

From a well-being perspective rooted in positive psychology, our results support the notion that happier and healthier individuals are more likely to engage in prosocial acts such as charitable giving. Subjective well-being, measured as happiness or life satisfaction, showed a significant positive effect on donation behavior, consistent with the classic “feel-good, do-good” hypothesis [

84]. In other words, respondents reporting greater life satisfaction were also more inclined to donate, aligning with evidence that positive emotional states promote altruism and may, in turn, be enhanced by altruistic behavior in a reciprocal cycle. These findings confirm Well-Being Theory’s proposition that individual flourishing is closely tied to socially beneficial action and extend its applicability to a transitioning economy like Uzbekistan.

Health also played a notable role, exerting an indirect effect on giving through happiness. As in prior research linking health to life satisfaction [

85] healthier respondents reported greater happiness, which subsequently increased their likelihood of donating. This mediation (H5) supports the idea that physical and mental well-being provides the emotional and cognitive resources that facilitate generosity. Conceptually, individuals in better health are more energetic, positive, and outward-looking, making them more able and willing to contribute to others. In contrast, income did not influence giving indirectly via happiness. While higher income directly predicted greater donations—reflecting resource capacity—it did not make people happier in ways that translated into more giving. This null mediation is consistent with research showing that beyond a certain threshold, additional income produces limited improvements in subjective well-being [

41]. Many respondents in our sample may already have met basic material needs, so extra income affected giving through disposable resources rather than mood. Taken together, these results highlight two distinct pathways to generosity: a psychological route, whereby happiness and life satisfaction enhance prosocial motivation, and a material route, whereby economic resources enable donations independently of well-being. The findings underscore the dual role of flourishing and financial capacity in sustaining philanthropy, and they suggest that fostering subjective well-being—through mental health, community belonging, and overall life satisfaction—may indirectly strengthen charitable engagement.

5.4. Cultural and Institutional Context in Uzbekistan

We consider cultural and institutional factors that may explain the reversal of the personal norm effect and the broader pattern of results in the Uzbek context. Social and institutional environments strongly shape how moral obligations are translated into charitable action. In Uzbekistan, two factors stand out: underdeveloped private charities and the prevalence of informal giving networks.

Limited number of efficiently functioning charitable organization may lead to lowertrust in them and likely attenuates the effect of moral norms on formal donations. Even if individuals feel morally obliged to help others, skepticism about NGOs’ effectiveness can discourage donations to official charities. Concerns about mismanagement of funds and limited accountability have been documented in the Central Asian region, with a recent analysis highlighting the absence of a strong “culture of charity” in Central Asia, partly due to limited public awareness and institutional credibility [

86]. Instead, philanthropic norms are often enacted through informal, community-based giving. Traditional institutions such as the mahalla (neighborhood community) remain central to redistributive practices. Mahalla leaders frequently organize collections from residents and redistribute resources directly to families in need, ensuring high visibility, trust, and community legitimacy [

87]. Religious channels such as mosques also serve as trusted intermediaries for donations. In this context, individuals with strong personal moral norms may prefer to give through these informal or relational avenues rather than to formal charities. This substitution effect could make those with the strongest sense of obligation appear less likely to donate to formal organizations, thereby producing the negative statistical association observed.

Thus, the anomalous coefficient for personal norms may not indicate that moral obligation suppresses generosity, but rather that generosity is redirected toward informal networks more consistent with cultural expectations and institutional trust. We therefore interpret the result as context-specific: in Uzbekistan, moral norms may drive prosocial behavior outside formal charitable channels. Future research should explicitly measure both social capital and informal giving practices to test their moderating effects on the relationship between moral obligation and donation behavior.

In summary, Uzbekistan’s institutional environment—characterized by cautious attitudes toward NGOs and reliance on robust informal support networks—offers a plausible explanation for why personal norms show a reversed effect in our model. This highlights the importance of situating models of charitable giving within their cultural context and cautions against assuming direct transferability of findings across societies [

86].

5.5. Contributions to the Sustainability Agenda

Finally, our study carries implications for the broader sustainability agenda, particularly the social dimension of sustainable development. Charitable giving is a vital mechanism for addressing societal challenges and advancing humanitarian goals. It directly supports initiatives to reduce poverty, improve health and education, and build resilient communities—outcomes aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (e.g., SDG 1 “No Poverty”, SDG 3 “Good Health and Well-Being”, SDG 10 “Reduced Inequalities”). By identifying the determinants of charitable behavior in an emerging economy context, we provide insights on how to foster greater public participation in these sustainability efforts. Our findings suggest that increasing individual well-being and economic security can have the dual benefit of enhancing quality of life and boosting prosocial contributions to society. For instance, the positive effect of happiness on giving indicates that policies and programs that improve citizens’ life satisfaction (through better public services, community engagement, mental health support, etc.) may yield a more civically active and generous populace. Similarly, the link between higher income and greater donation levels reinforces the importance of economic development and equality: as more households achieve financial stability, their capacity and propensity to donate grow, creating a virtuous cycle of resource redistribution. This resonates with prior observations that charitable donations help channel private resources into public good, thereby complementing government and international efforts to meet social needs [

23].

Moreover, the prominent role of personal moral norms in our study underscores the value of cultural and educational strategies for sustainable development. Instilling strong prosocial values—whether through family, schools, or religious institutions—can activate individuals’ sense of responsibility toward community welfare. In Uzbekistan’s case, leveraging existing cultural norms of generosity and solidarity (for example, the ethos of mahalla community support) could encourage giving behavior, but it must be performed carefully. Our unexpected negative finding for personal norms serves as a caution: simply exhorting people that they “ought” to donate is not enough, and excessive moral pressure in the absence of enabling conditions might even backfire. To promote sustainable philanthropy, it is crucial to couple moral encouragement with practical facilitation—for example, making donation opportunities accessible, transparent, and trust-inspiring, and ensuring people have the economic means to contribute. By integrating psychological drivers with socioeconomic levers, stakeholders (policymakers, non-profits, and community leaders) can more effectively cultivate a culture of giving that supports long-term sustainable development. Moreover, it is essential to account for financial literacy in the charitable giving modeling in the context of sustainable development [

88].

6. Theory and Practical Implications

This study integrates three major theoretical perspectives—Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), Norm Activation Theory (NAT), and Well-Being Theory (WBT)—to analyze charitable giving in Uzbekistan. By combining these frameworks, the research provides a multidimensional view of philanthropy that accounts for socioeconomic, psychological, and normative drivers.

From a theoretical standpoint, the findings highlight a dual-pathway model of charitable giving. On one hand, socioeconomic resources such as income and age significantly influence charity, reflecting the resource-based pathway. On the other hand, subjective well-being, particularly happiness, emerged as a robust predictor, underscoring the psychological pathway. Together, these results affirm that both financial capacity and positive well-being conditions are necessary to sustain prosocial behavior. This dual-pathway contribution extends the current literature by showing that financial and psychological determinants are not substitutes but complementary forces shaping charitable action. At the same time, the non-significance of traditional TPB constructs—attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control— could be interpreted as showing that the explanatory power of TPB may be limited in transitional economies where cultural norms and institutional trust differ from Western contexts. The unexpected negative relationship between personal norms and charitable giving further challenges the universality of NAT, pointing to the importance of cultural and institutional conditions in shaping norm–behavior links. Thus, the study refines both TPB and NAT by showing their boundary conditions in non-Western societies. The results confirm that higher income and older individuals are more likely to give, suggesting that NGOs and policymakers could design targeted fundraising strategies aimed at these groups. For example, charities could develop membership-based programs for older citizens or create tax incentives and recognition schemes for high-income donors. Moreover, the positive association between happiness and charity demonstrates that emphasizing the well-being benefits of giving may be more effective than appealing to moral duty. Campaigns that frame charity as a source of personal fulfillment and life satisfaction are likely to resonate strongly in this context.

Finally, the findings imply that religious and community institutions should complement appeals to moral duty with strategies that build trust, transparency, and institutional credibility. Given the limited influence of subjective norms, campaigns should move beyond simple peer pressure and instead focus on tangible well-being and community impact outcomes. By doing so, NGOs and faith-based organizations can better align with the cultural realities of Uzbekistan and enhance sustainable engagement in charitable activities.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This study makes an important contribution to understanding charitable giving in Uzbekistan, yet several limitations must be acknowledged, each of which shapes how the findings should be interpreted and points toward future research opportunities.

First, the low explanatory power of the model limits practical predictability. The R2 for charitable giving was 0.154, meaning that the predictors captured only part of the variance. While this is not unusual in behavioral studies, it highlights the need to consider additional factors. Accordingly, the results should be interpreted as exploratory evidence of significant psychological and socio-economic associations, rather than as a fully predictive model of giving behavior. Future research should expand the model by including theoretically relevant variables such as institutional trust, religiosity, social capital, and digital giving behaviors, which may increase explanatory power and provide a more complete account of prosocial action.

Second, the use of self-reported survey measures raises concerns about social desirability bias and recall error. Respondents may have overstated their charitable behavior or reported moral attitudes not reflected in their actual actions. This limitation is particularly important for explaining the counterintuitive negative effect of personal norms. Future studies should incorporate behavioral indicators (e.g., real donation pledges, willingness-to-donate tasks) or administrative data from charitable organizations, and apply social desirability scales to control for bias.

Third, the cross-sectional design restricts the ability to establish causal relationships. Although associations between income, happiness, and charity were observed, causality cannot be inferred. Longitudinal designs would allow tracking of how determinants and charitable behavior evolve over time, while experimental approaches could test specific causal mechanisms.

Fourth, the geographic and demographic scope of the sample constrains generalizability. The study was limited to Tashkent and Syrdarya, which may not represent the broader diversity of Uzbekistan’s population. Charitable practices in rural areas or among different cultural subgroups may differ substantially. Future research should therefore adopt more geographically diverse sampling and, ideally, conduct comparative studies across Central Asian countries to reveal shared and distinct regional patterns of giving.

Fifth, some constructs—such as income, happiness, and donor due diligence—were measured using single-item indicators. While pragmatic, single-item measures may reduce reliability and understate the constructs’ explanatory power. Future studies should use multi-item validated scales to capture these variables more robustly and improve construct reliability.

The negative association between personal norms and charity remains a striking anomaly. This may reflect multicollinearity with related constructs, cultural factors such as the importance of informal giving, or measurement artifacts. Future research should explore this issue through mixed-method approaches, such as interviews and focus groups, which can provide deeper insight into how individuals interpret moral obligation and reconcile it with economic constraints or institutional trust. Quantitative extensions could also examine moderators such as religiosity and institutional trust to test under what conditions personal norms enhance rather than diminish giving.

8. Conclusions

This study advances the understanding of charitable giving in Uzbekistan by integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior, Norm Activation Theory, and Well-Being Theory into a multidimensional explanatory framework. The findings highlight two distinct pathways to prosocial financial behavior: a resource-driven pathway, where income and age significantly predict giving, and a well-being pathway, where happiness plays both a direct role and a mediating role between health and charitable behavior. At the same time, the non-significance of traditional TPB constructs (attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control) and the unexpected negative effect of personal norms underscore the limitations of Western-centric behavioral models in transitional economies, where cultural norms, institutional trust, and informal giving practices shape behavior differently.

Theoretically, this research contributes by demonstrating that established models of planned and moral behavior require contextual adaptation to accurately capture prosocial actions in emerging economies. Practically, the results point to the importance of emphasizing well-being benefits and demographic targeting in charitable campaigns, rather than relying solely on appeals to duty or social pressure. From a policy perspective, the findings suggest that building institutional trust, strengthening transparency in charitable organizations, and aligning strategies with cultural traditions of giving can enhance philanthropic engagement.

Overall, this study underscores the value of culturally grounded approaches in sustainability-oriented research on philanthropy. By situating charitable behavior within the socioeconomic and psychological realities of Uzbekistan, it provides both theoretical refinement and actionable guidance for NGOs, policymakers, and community leaders seeking to foster inclusive and sustainable prosocial engagement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.E. and R.S.; methodology, D.E.; software, D.E.; validation, D.E.; formal analysis, D.E.; investigation, D.E. and A.M.; resources, D.E. and A.M.; data curation, D.E. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.E.; writing—review and editing, D.E. and R.S.; visualization, D.E.; supervision, R.S.; project administration, D.E.; funding acquisition, D.E., A.M. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted on a voluntary and anonymous basis among diverse group of individuals. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by the Ethics Panel of Westminster International University in Tashkent (Exemption Protocol Code: RO/06-01-00131, Date of Exemption: 22 May 2025), as the research involved only anonymous survey procedures and posed no more than minimal risk to participants. This study has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participation in the survey was voluntary, and completion of the survey was considered implied informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the author and can be produced upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lab for Social and Human Capital for feedback received from the HIVE Courses for Academic Research Publishing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NGO | Non-government organization |

| TPB | The Theory of Planned Behavior |

| PBC | Perceived Behavioral Control |

| NAT | The Norm Activation Theory |

| SPHS | Self-Perceived Health Scale |

| BPLSR | Binary Partial Least Squares Regression |

| CAF | Charities Aid Foundation |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Scales and items.

Table A1.

Scales and items.

| Key Constructs | Items Description |

|---|

| Charity | Have you donated to charity in the last 12 months? |

| Attitude | I am satisfied with my participation in charity.

I feel it is my moral duty to help those in need.

I usually consider myself a generous person.

I believe that helping others is an important part of being a good person.

I would still donate to charity even if I did not receive recognition or reward.

Donating to charity gives me spiritual satisfaction/encouragement. |

| Subjective Norms | My religious belief encourage me to donate to charity.

In my values, helping those in need is considered a normal and expected behavior. |

| Personal Norms | Helping people with problems is very important to me.

People in society should be more generous to others.

It is always necessary to provide help to those in need.

People should try to support the less fortunate. |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | I am confident in managing my personal finances.

I believe that I have sufficient means to provide financial assistance to others. |

| Health | I am satisfied with my health.

Overall, I would describe my health as good. |

| Donor Due Diligence | Before donating, I am able to identify trustworthy organizations. |

| Happiness | Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays? |

Appendix A.2

Table A2.

Item removed from Personal Norm construct after multicollinearity check.

Table A2.

Item removed from Personal Norm construct after multicollinearity check.

| Key Constructs | Items Description | Status |

|---|

| Personal Norms | Helping people with problems is very important to me. | Retained |

| People in society should be more generous to others. | Retained |

| It is always necessary to provide help to those in need. | Retained |

| People should try to support the less fortunate. | Excluded during model evaluation due to high VIF |

References

- Yu, H.C.; Kuo, L. Corporate philanthropy strategy and sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuran, T. The provision of public goods under Islamic law: Origins, impact, and limitations of the waqf system. Law Soc. Rev. 2001, 35, 841–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napiórkowska, A.; Zaborek, P.; Witek-Hajduk, M.K.; Grudecka, A. Individual Cultural Values and Charitable Crowdfunding: Driving Social Sustainability Through Consumer Engagement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Tang, T. Digital economy and private donation behavior: An empirical analysis based on the CFPS data. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1195114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, A.; Lee, S. Trust and relationship commitment in the United Kingdom voluntary sector: Determinants of donor behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 613–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehringer, T. Corporate foundations as partnership brokers in supporting the United Nations’ sustainable development goals (SDGs). Sustainability 2020, 12, 7820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.; Savani, S. Predicting the accuracy of public perceptions of charity performance. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 2003, 11, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiepking, P.; Bekkers, R. Who Gives? A Literature Review of Predictors of Charitable Giving II¿ Gender, Marital Status, Income and Wealth. Volunt. Sect. Rev. 2012, 3, 217–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, R. Trust and volunteering: Selection or causation? Evidence from a 4 year panel study. Political Behav. 2012, 34, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R.; McSweeney, A. Charitable giving: The effectiveness of a revised theory of planned behaviour model in predicting donating intentions and behaviour. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 17, 363–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Fan, Z.; Gao, J. Implementation evaluation and sustainable development of China’s religious charity policy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, X.; Liu, F. The impact of social capital on volunteering and giving: Evidence from urban China. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2018, 47, 1201–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, R.; Ismail, A.G. Taking stock of the waqf-based Islamic microfinance model. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2017, 44, 1018–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apergis, N.; Lau, C.K.M.; Şen, F.Ö.; Wang, S. Market integration between Turkey and Eurozone countries. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2021, 57, 2674–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadov, A.; Turaboev, I.; Nor, M.Z.M. Garnering potential of zakat in Uzbekistan: A tax policy proposal. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EM Insight. Uzbekistan’s Civil Society Institutions: A Bridge Between Society and State. 22 October 2024. Available online: https://eminsight.co.uk/2024/10/22/uzbekistans-civil-society-institutions-a-bridge-between-society-and-state/ (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Third Sector in Uzbekistan: New Trends. Embassy of Uzbekistan in India. 2020. Available online: https://www.uzbekembassy.in/third-sector-in-uzbekistan-new-trends/ (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: Brighton and Hove, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, E.W.; Aknin, L.B.; Norton, M.I. Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science 2008, 319, 1687–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P.A.; Hewitt, L.F. Volunteer Work and Well-Being. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2001, 42, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, F.; Lu, Y.P.; Zhang, Y. Does religious belief affect volunteering and donating behavior of Chinese college students? Religions 2020, 11, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.M.; Starfelt Sutton, L.C.; Zhao, X. Charitable donations and the theory of planned behaviour: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekkers, R.; Wiepking, P. Generosity and Philanthropy: A Literature Review. Science of Generosity Project, University of Notre Dame. 2007. Available online: https://generosityresearch.nd.edu/assets/17402/generosity_and_philanthropy_revised.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Zhu, W.; Du, Z.; Zhai, F.; Lv, K. Mediating effects of physical self-esteem and subjective well-being on physical activity and prosocial behavior among college students. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, R.; Wiepking, P. A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: Eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2011, 40, 924–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.; Han, E. The application of the theory of planned behavior to identify determinants of donation intention: Towards the comparative examination of positive and negative reputations of nonprofit organizations CEO. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanto, A. Opportunity to donate as the antecedent of theory of planned behaviour in determining intention to donate to donation behavior. J. Leg. Ethical Regul. Isses 2022, 25, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Yang, C. Sustainable Consumption and Residents’ Happiness: An Empirical Analysis Based on the 2021 Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS2021). Sustainability 2024, 16, 8763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Zhou, R. Do Mixed Religions Make Families More Generous? An Empirical Analysis Based on a Large-Scale Survey of Chinese Families. Religions 2024, 15, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geys, B.; Sørensen, R.J. Transitory income windfalls and charitable giving: Evidence from Norwegian register data, 1993–2021. Econ. J. 2025, 135, 943–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.K. Charitable giving with stochastic income. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2022, 97, 101826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlaß, N.; Gangadharan, L.; Jones, K. Charitable giving and intermediation: A principal agent problem with hidden prices. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2023, 75, 941–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midlarsky, E.; Hannah, M.E. The generous elderly: Naturalistic studies of donations across the life span. Psychol. Aging 1989, 4, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, R.; Freund, A.M. Beyond money: Nonmonetary prosociality across adulthood. Psychol. Aging 2021, 36, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiepking, P.; James, R.N., III. Why Are the Oldest Old Less Generous? Explanations for the Unexpected Age-Related Drop in Charitable Giving. Ageing Soc. 2013, 33, 486–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]