The Mechanism of Textile Recycling Intention and Behavior Transformation: The Moderating Effect Based on Community Response

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundations

2.2. Hazards of Used Clothing

2.3. Significance of Old Clothing Recycling

2.4. Demand for Used Clothing

2.5. Policies Related to Used Clothing Recycling

2.6. The Textile Circular Economy and Consumer Psychology

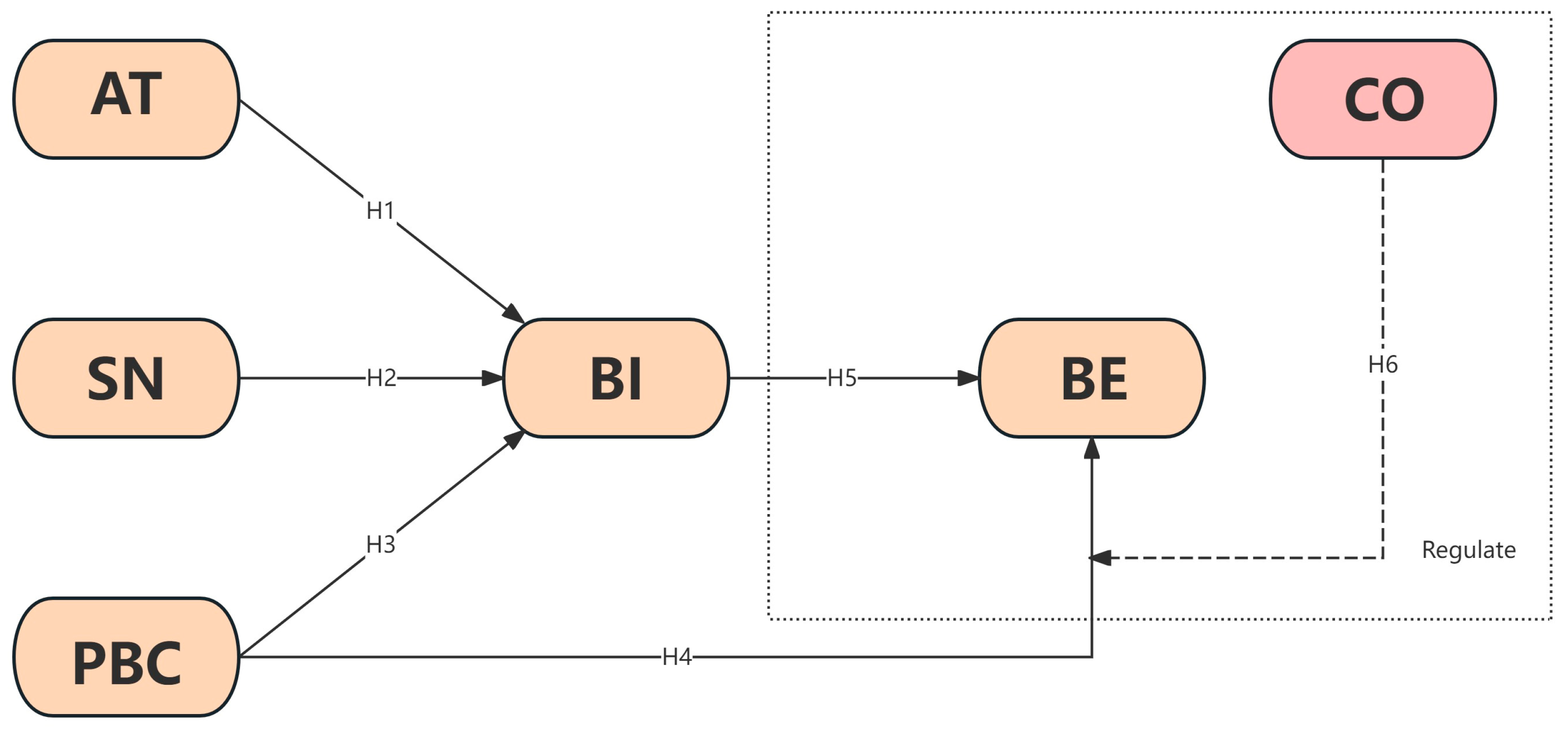

3. Theories and Research Hypotheses

Model and Hypothesis Proposed

- (1)

- Attitude

- (2)

- Subjective norms

- (3)

- Perceived behavioral control

- (4)

- Behavioral intention

- (5)

- Community outreach

4. Methodology

4.1. Method Introduction

- (1)

- Respondents were clearly informed of the purpose and the importance of the survey before it began, ensuring that respondents understand the value of their contributions to the research.

- (2)

- For each question or measurement item in the questionnaire, provide a detailed explanation, including the purpose of the question and how it is expected to be answered.

- (3)

- Inform respondents in advance that their personal information will be protected, absolute anonymity of the questionnaire was ensured, and only the collected data were used for study analysis.

- (4)

- Emphasize that there is no such thing as a right or wrong answer in the questionnaire and encourage respondents to respond based on their true feelings and experience.

- (5)

- Participants were informed that they were free to choose whether to participate in the survey and that they had the right to decide not to complete the questionnaire or withdraw at any time during the survey.

- (6)

- To ensure the legitimacy of the data, review it after it has been collected and exclude responses that are clearly not logical or consistent, such as situations where all questions choose the same option.

- (7)

- Before data analysis, data cleaning is performed to eliminate invalid or abnormal data points to guarantee the precision and dependability of the analysis outcomes.

- (8)

- Maintain a high degree of transparency and integrity to ensure the fairness and objectivity of the investigation process and results.

4.2. Questionnaire Design

4.3. Data Collection

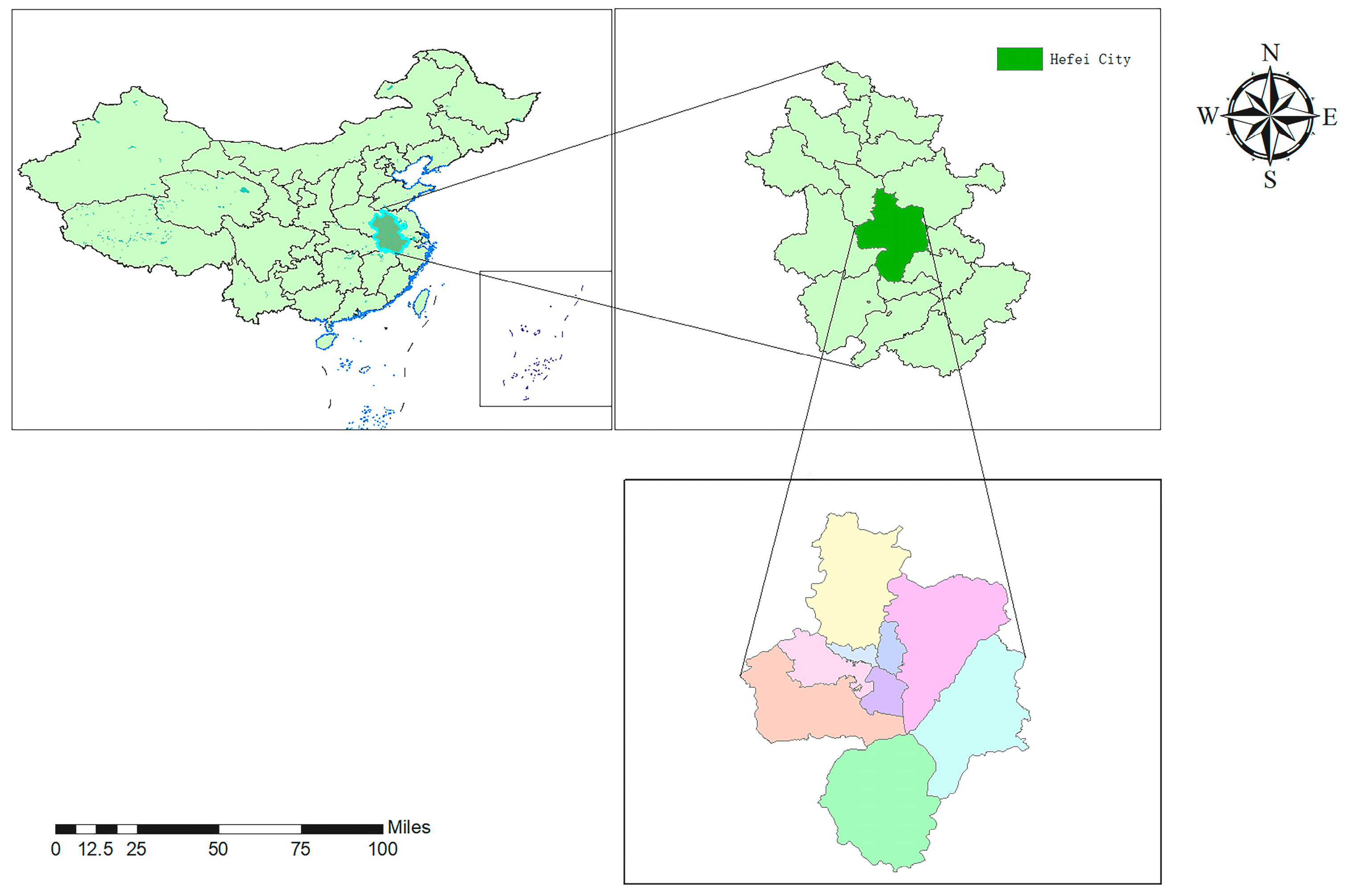

4.4. Study Area

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Reliability and Validity Test

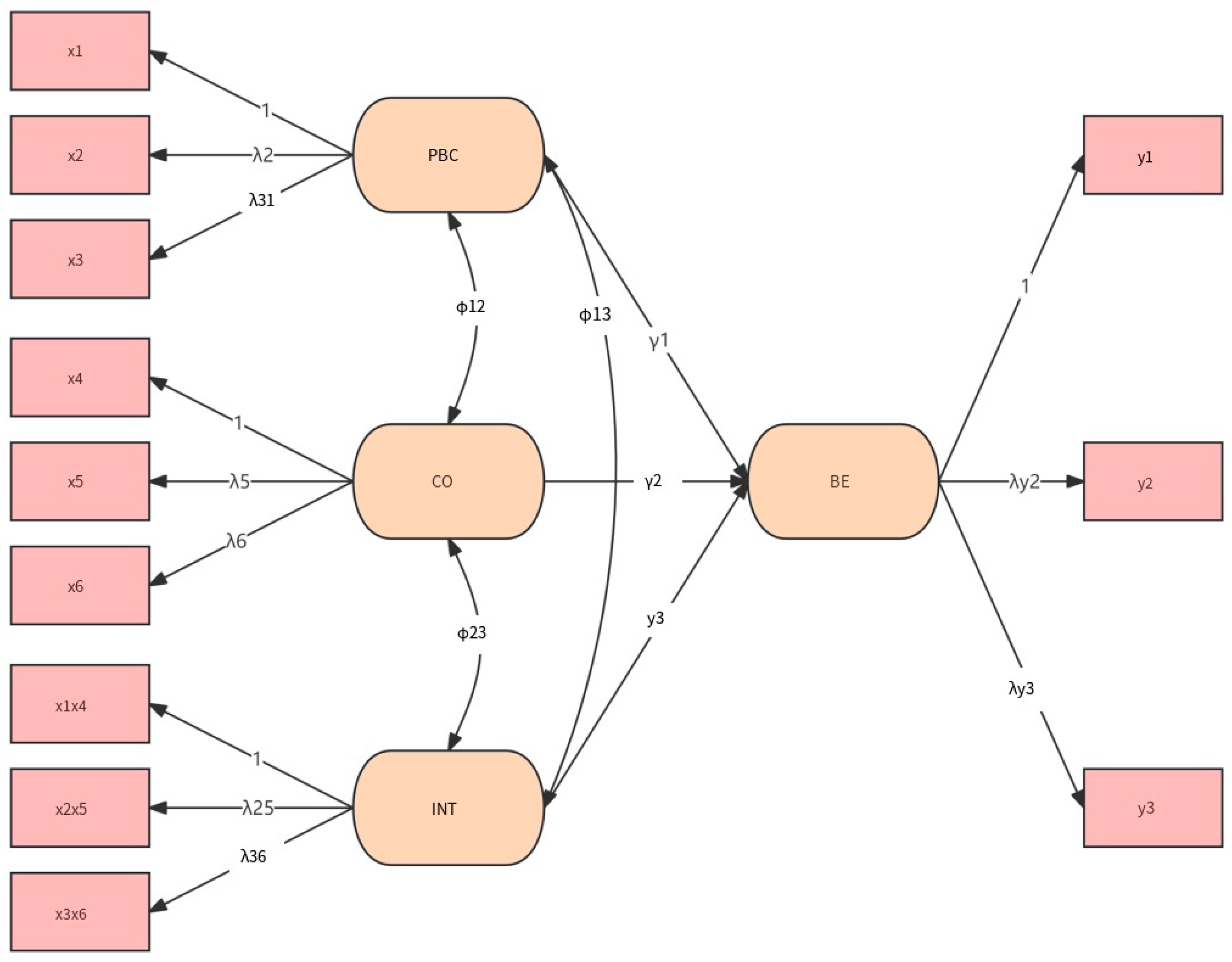

5.2. Model Fit Test

5.3. Path Analysis Results

5.4. Adjust the Test Results

6. Discussion

6.1. Analysis of Influencing Factors of Residents’ Old Clothing Recycling

- (1)

- The effect of attitude on the willingness to recycle used clothing

- (2)

- The influence of subjective norms on the willingness to recycle used clothing

- (3)

- Perceive the effect of behavioral control on willingness and behavior

- (4)

- The influence of recycling intention on recycling behavior

- (5)

- An introduction to the influencing factors of residents’ used clothes recycling

6.2. Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Community Promotion

6.3. Countermeasures and Suggestions

- (1)

- Enhance environmental publicity and education to increase residents’ awareness of the value of recycling used clothing. The environmental significance and economic value of used clothing recycling should be popularized among residents through publicity activities and the production of publicity materials, and residents should be guided to establish environmental awareness and actively participate in the recycling of used clothing.

- (2)

- Encourage positive interaction and imitation among community residents, such as through the demonstration role of community leaders or opinion leaders, to promote the popularization of used clothing recycling.

- (3)

- Reasonably plan community promotion activities to ensure that activities can actually improve residents’ perceived behavior control, rather than merely increasing the frequency or intensity of community promotion. Establish a tracking and evaluation mechanism for the effect of used clothing recycling, regularly evaluate the effectiveness of recycling policies and activities, and adjust and optimize according to the evaluation results.

- (4)

- Encourage cooperation between the government, enterprises, non-governmental organizations, and community residents to jointly promote the recycling of used clothing and resource recycling. More incentives, such as recycling rewards and tax incentives, should be introduced by the government and relevant departments to encourage residents and businesses to participate in the recycling of used clothes.

6.4. Inadequacies of the Research

- (1)

- The research could be confined to the particular conditions of Hefei, Anhui province, China, and may not be fully representative of used clothing recycling practices in other regions or countries.

- (2)

- The study mainly focused on residents’ intention and behavior of used clothing recycling, and may not fully cover all influencing factors, such as cultural differences and economic incentives.

- (3)

- Most of the subjects investigated in this paper have a certain educational background, which may lead to a decrease in the universal applicability of the data results.

6.5. Future Outlook

- (1)

- It is suggested that the scope of the study be expanded to include residents from different regions and various cultural backgrounds to confirm the universality and applicability of the model.

- (2)

- Further research is recommended on the specific barriers and facilitators in the recycling process of used clothing, as well as how to overcome them more effectively.

- (3)

- It is recommended to explore the influence of different incentives on used clothing recycling behavior, such as financial incentives, policy support, etc.

- (4)

- Interdisciplinary research is encouraged, combining knowledge from fields such as environmental science, sociology, psychology, and economics to understand and promote used clothing recycling more comprehensively.

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- At the 10% significance level, the path coefficient between attitude and intention is greater than 0 (β = 0.059), which is a positive correlation. Residents’ attitude towards used clothing recycling has an impactful influence on their behavioral intention. When citizens have a favorable view on secondhand clothing recycling, they are more inclined to possess a readiness to engage in the recycling of used garments. This positive attitude may stem from environmental recognition, recognition of the reuse of resources, and a concern to reduce the environmental impact of waste.

- (2)

- There is a significant positive correlation between subjective norms and residents’ intention (β = 0.323, p < 0.01). Subjective norms also have an important impact on residents’ behavioral intention to recycle used clothing. When residents feel that people around them (such as family, friends, community members, etc.) have a positive attitude towards used clothing recycling and expect them to participate, they are more likely to have a willingness to participate in used clothing recycling.

- (3)

- The results of standardized path coefficient showed that perceived behavior control had a major positive impact on residents’ used clothing recycling intention (β = 0.615, p < 0.01). Perceived behavioral control is also a key factor affecting residents’ behavioral intention of used clothing recycling. Residents are more likely to be willing to participate in recycling when they believe they have the capacity, resources, and opportunities to participate in recycling.

- (4)

- The intention-to-be has a high degree of significance to the result of the behavior, and the path coefficient is large (β = 0.718); residents’ intention and behavior are highly positively correlated. There is a notable connection between behavioral intention and real behavior. When residents have a strong will to participate in the recycling of old clothes, they are more likely to translate this will into actual action.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Economic Daily. China’s Textile Power Goal Has Been Basically Achieved. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-01/18/content_5580593.htm (accessed on 18 October 2024). (In Chinese)

- National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Implementation Opinions on Accelerating the Recycling of Waste Textiles. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-04/12/content_5684664.htm (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Deng, M. Turn the mountain of old clothes and garbage into a mountain of gold and silver. China Sustain. Trib. 2022, 5, 53–60. Available online: https://wenku.baidu.com/view/2f59d1c16b0203d8ce2f0066f5335a8103d26657.html?_wkts_=1760973563652&needWelcomeRecommand=1 (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Xinhua News Agency. What Should I Do with the “garbage” of 26 Million Tons of Old Clothes Discarded Every Year?—Survey of Used Clothes Recycling. 2019. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2019-08/01/c_1124826784.htm (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Yan, C.; Zhai, W. Research and analysis of old clothes recycling, environmental protection and regeneration, and discussion of the value and significance of transformation. Light Ind. Technol. 2020, 11, 116–117. Available online: https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=7103407234 (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Yu, B. The Recycling of Used Clothes Is an Easily Overlooked 100 Billion Market. 2021. Available online: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_15216472 (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- Li, J. Actively Promote the Recycling of Waste Textiles and Garments. 2015. Available online: https://www.chinacace.org/news/view?id=5151 (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenberg, J.; Fryk, L. Urban Empowerment Through Community Outreach in Teaching and Design. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 3284–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Network, C.C. “Replace the Old with the New” Allows the Community Environment to Say Goodbye to the Old and Welcome the New. 2024. Available online: https://www.bjwmb.gov.cn/wmsj/10052859.html (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Mancha, R.M.; Yoder, C.Y. Cultural antecedents of green behavioral intent: An environmental theory of planned behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansser, O.A.; Reich, C.S. Influence of the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) and environmental concerns on pro-environmental behavioral intention based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 134629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M. Theory of planned behavior. In Handbook of Sport Psychology; Taylor & Francis Group: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; p. 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Dewitte, S. Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Pan, J. The investigation of green purchasing behavior in China: A conceptual model based on the theory of planned behavior and self-determination theory. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohu.com Limited. What Is the Impact on the Environment If you Simply Throw Away Old Clothes? 2021. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/500223474_468814 (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Xiang, K.L. Minhou County Industrial and Commercial Bureau “Released” 160 Tons of Foreign Garbage with Bacteria. 2004. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=5MjHqO3BiXVCMeLsJRbS6L0uO9D0CES41DCS9lTP01O8Z2wm2UVFloECzH6oWTtSOuHxRfBz5019hzRPtT1kBnopx3-0FPXqESxGU2RzilhiDxyWD4A8Xi5Iwu0MJRV0V9ga3pNiADROHdB2G5L7DCSMGtrLtKjwf1GxBLsUuq31OQqEZMUvXjSE8mOyOGlUhNeGftDdAAw=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Liu, Y. The development and significance of the “Zero Disposal of Used Clothes” project. China Text. Lead. 2015, 12, 117–119. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Farrant, L.; Olsen, S.I.; Wangel, A. Environmental benefits from reusing clothes. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohu.com Limited. Comprehensive Analysis of the Second-Hand Clothing Market in 2025. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/873013649_122162097 (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Sohu.com Limited. Used “Clothes Recycling” Is Looking Forward to Policy Support 2017. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/206356059_628232 (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- WISDING. Notice of the Office of the Hefei Municipal People’s Government on Printing and Distributing the Implementation Plan for the Construction of the Recycling System of Waste Materials in Hefei City. 2024. Available online: http://news.qyzyw.com/article/4654 (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Bukhari, M.A.; Carrasco-Gallego, R.; Ponce-Cueto, E. Developing a national programme for textiles and clothing recovery. Waste Manag. Res. 2018, 36, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Memon, H.A.; Wang, Y.; Marriam, I.; Tebyetekerwa, M. Circular Economy and Sustainability of the Clothing and Textile Industry. Mater. Circ. Econ. 2021, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Escamilla, H.G.; Martínez-Rodríguez, M.C.; Padilla-Rivera, A.; Domínguez-Solís, D.; Campos-Villegas, L.E. Advancing Toward Sustainability: A Systematic Review of Circular Economy Strategies in the Textile Industry. Recycling 2024, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofei, O.; Iordachi, V.; Perciun, R. Consumer Behavior Towards Recycled Clothing. Cogito 2024, 16, 119–140. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk, E.; Şahin, A. Encouraging sustainable clothing disposal: Consumers’ social recycling motivations in Turkey. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2023, 25, 3021–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M.; Lohmann, S.; Albarracín, D. The influence of attitudes on behavior. In The Handbook of Attitudes; Taylor & Francis Group: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 197–255. [Google Scholar]

- Baierl, T.-M.; Kaiser, F.G.; Bogner, F.X. The supportive role of environmental attitude for learning about environmental issues. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandve, A.; Øgaard, T. Exploring the interaction between perceived ethical obligation and subjective norms, and their influence on CSR-related choices. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tonder, E.; Fullerton, S.; De Beer, L.T.; Saunders, S.G. Social and personal factors influencing green customer citizenship behaviours: The role of subjective norm, internal values and attitudes. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, N.; Shah, A.; Munir, F. Impact of socio-demographic, psychological and emotional factors on household direct and indirect electricity saving behavior: A case study of Pakistan. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 429, 139581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fisbbein, M.J.H. Factors influencing intentions and the intention-behavior relation. Hum. Relat. 1974, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Chi, X.; Kim, J.J.; Kim, G.; Quan, W.; Han, H. Traveling with pets and staying at a pet-friendly hotel: A combination effect of the BRT, TPB, and NAM on consumer behaviors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 120, 103771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likert, R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 55, 22140. [Google Scholar]

- WJX. 2006. Available online: https://www.wjx.cn/ (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- News, H.E. Hefei Used Clothes Recycling Factory Receives an Average of 2 Tons of Used Clothes Per Day for Sorting and Reuse. 2015. Available online: https://ah.ifeng.com/news/zaobanche/detail_2015_10/29/4496889_0.shtml (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Wu, M. The List of National Key Cities has been Announced! Hefei Is on the List! 2022. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzA5ODM0NzUxNQ==&mid=2651078198&idx=1&sn=393b2d98dfc7a1ab1924ad1c172a3501&chksm=8b626ea2bc15e7b45f76dc41f520a7e1bf1b188ecc3db06347a7380bd5df4af6ad3ed37e91c5&scene=27#wechat_redirect (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- News, H.E. The Old Clothes Recycling Bin Appeared in the Hefei Community to Recycle 30,000 Kilograms of Old Clothes a Month. 2015. Available online: https://ah.ifeng.com/detail_2015_08/28/4290029_0.shtml (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Bujang, M.A.; Omar, E.D.; Baharum, N.A. A review on sample size determination for Cronbach’s alpha test: A simple guide for researchers. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 25, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate data analysis with readings. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1988, 151, 558–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeish, D. Should we use F-tests for model fit instead of chi-square in overidentified structural equation models? Organ. Res. Methods 2020, 23, 487–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Curran, P.J.; Bollen, K.A.; Kirby, J.; Paxton, P. An empirical evaluation of the use of fixed cutoff points in RMSEA test statistic in structural equation models. Sociol. Methods Res. 2008, 36, 462–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muneswarao, J.; Hassali, M.A.; Ibrahim, B.; Saini, B.; Naqvi, A.A.; Hyder Ali, I.A.; Rao, J.M.; Ur Rehman, A.; Verma, A.K. Translation and validation of the Test of Adherence to Inhalers (TAI) questionnaire among adult patients with asthma in Malaysia. J. Asthma 2021, 58, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Fassott, G. Testing moderating effects in PLS path models: An illustration of available procedures. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Spinger: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 713–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Wu, Y. Evolution and Simplification of Latent Variable Interaction Modeling Methods. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 18, 1306–1313. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=Ss1McYY34CfGGZgcZaWjY1i2JAMLgrWL4QA6S7Mqj3Wh4QBhypHGsXN3sOWSNn6InBPqyPjC_n5aaOawyPa3dbcx2dZHcu-HBwfA6sWt481Z8HNyB4dwS5KImWGWbg4jC5N69INZ4eFrYHa1wwDQ2dq1Gelaz9i89Z0x2Ogg2AtsKHWeQxFO8w==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Wu, Y.; Wen, Z.; Hou, J.; Marsh, H.W. Standardized estimation of latent variable interaction effect models without mean structure. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2011, 43, 1219–1228. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=Y4WXQ1XfpS7oOi_YA2ypC8x7nZojMmXkukuHLSbPhEn1BarjYemM8x3PQwZAlvg_Olmu6kaQz-TrI4FozcTvuqDYDepWtMoXuse37bOEmuHPNqGieA6ZjpfTsJPFmyfrdAsTkZL8uIf1z9RX6nnB1AeduPn6ETtxpQSPt2xYDh2ALe6ABUr689HKqbhTn4O5&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Robinson, C.D.; Tomek, S.; Schumacker, R.E. Tests of moderation effects: Difference in simple slopes versus the interaction term. Gen. Linear Model J. 2013, 39, 16–24. Available online: https://ojs.lib.ua.edu/glmj/article/view/268/222 (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Lin, C.-W.R.; Chen, M.T.; Tseng, M.-L.; Jantarakolica, T.; Xu, H. Multi-Objective Production Programming to Systematic Sorting and Remanufacturing in Second-Hand Clothing Recycling Industry. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B. A general structural equation model with dichotomous, ordered categorical, and continuous latent variable indicators. Psychometrika 1984, 49, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onel, N. Pro-environmental Purchasing Behavior of Consumers: The Role of Norms. Soc. Mark. Q. 2016, 23, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Xu, Y. Investigating the factors influencing urban residents’ low-carbon travel intention: A comprehensive analysis based on the TPB model. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 22, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzoff, A.N. ‘Like me’: A foundation for social cognition. Dev. Sci. 2007, 10, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.-Z.; Wong, K.-H.; Lau, T.-C.; Lee, J.-H.; Kok, Y.-H. Study of intention to use renewable energy technology in Malaysia using TAM and TPB. Renew. Energy 2024, 221, 119787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Mangmeechai, A. Understanding the Gap between Environmental Intention and Pro-Environmental Behavior towards the Waste Sorting and Management Policy of China. Public Health 2021, 18, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G. How Large Can a Standardized Coefficient Be. 1999. Available online: https://cscar.github.io/misc/HowLargeCanaStandardizedCoefficientbe.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Liu, X. Research on Farmers’ Pro Environmental Production Behavior and Its Influencing Factors in Qingzhou City. Master’s Thesis, Yantai University, Yantai, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiqing, Y. A Study on the Willingness and Influencing Factors of Green Production Behavior among Small Farmers in Yantai City. Master’s Thesis, Yantai University, Yantai, China, 2025. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, C.W. Recycling Makes Old Clothes Transform into New Resources. 2022. Available online: https://epaper.cnwomen.com.cn/html/2022-07/22/nw.D110000zgfnb_20220722_1-8.htm (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Jih, W.-J. Effects of consumer-perceived convenience on shopping intention in mobile commerce: An empirical study. Int. J. E-Bus. Res. 2007, 3, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharat, M.G.; Murthy, S.; Kamble, S.J.; Kharat, M.G. Analysing the Determinants of Household Pro-Environmental Behaviour: An Exploratory Study. Environ. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 6, 184–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yang, M.; Yu, Q. An Analytical Study on the Resource Recycling Potentials of Urban and Rural Domestic Waste in China. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2012, 16, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- News, C.E. Old Clothes Recycling Upgraded. 2025. Available online: http://ccta.org.cn/jnhb/xhjj/201609/t20160914_2288136.html (accessed on 22 October 2024). (In Chinese).

| Demographic Attributes | Frequency, N | Percentage,% |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 311 | 55 |

| Female | 255 | 45 |

| Age | ||

| 18–35 years old | 351 | 62 |

| Ages 35–65 | 198 | 35 |

| Age 66+ | 17 | 3 |

| Level of education | ||

| Elementary school | 17 | 3 |

| Junior high | 62 | 11 |

| Senior high school | 182 | 32 |

| College degree or above | 305 | 54 |

| Income (month) | ||

| Less than 2000 yuan | 85 | 15 |

| 2000–5000 yuan | 170 | 30 |

| 5000–10,000 yuan | 237 | 42 |

| More than 10,000 yuan | 74 | 13 |

| Family size | ||

| 1 person | 11 | 2 |

| 2 people | 40 | 7 |

| 3 people | 209 | 37 |

| 4 people | 216 | 38 |

| 5 people | 62 | 11 |

| 6 and up | 28 | 5 |

| Constructs | N | AVE | CR | Alpha (>0.7) | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | 4 | 24.14 | 11.562 | 0.854 | 3.400 |

| SN | 3 | 15.87 | 17.017 | 0.879 | 4.125 |

| PBC | 3 | 16.23 | 12.568 | 0.875 | 3.545 |

| BI | 3 | 16.19 | 14.537 | 0.887 | 3.813 |

| BE | 3 | 15.53 | 17.882 | 0.887 | 4.229 |

| CO | 5 | 19.33 | 87.104 | 0.968 | 9.333 |

| Indicators | Standardize the Load | Unstandardized Load Capacity | S.E. | C.R. (t-Value) | P (*** p < 0.01) | SMC | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT1 | 0.824 | 1 | 0.68 | 0.839 | 0.568 | |||

| AT2 | 0.614 | 0.715 | 0.05 | 14.162 | *** | 0.38 | ||

| AT3 | 0.779 | 1.007 | 0.054 | 18.83 | *** | 0.61 | ||

| AT4 | 0.78 | 0.972 | 0.052 | 18.684 | *** | 0.61 | ||

| SN1 | 0.895 | 1 | 0.80 | 0.855 | 0.665 | |||

| SN2 | 0.729 | 0.672 | 0.035 | 19.065 | *** | 0.53 | ||

| SN3 | 0.814 | 0.816 | 0.036 | 22.602 | *** | 0.66 | ||

| PBC1 | 0.868 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.859 | 0.670 | |||

| PBC2 | 0.799 | 0.899 | 0.041 | 21.905 | *** | 0.64 | ||

| PBC3 | 0.786 | 0.87 | 0.04 | 21.738 | *** | 0.62 | ||

| BI1 | 0.776 | 1 | 0.60 | 0.878 | 0.706 | |||

| BI2 | 0.874 | 1.209 | 0.054 | 22.556 | *** | 0.76 | ||

| BI3 | 0.867 | 1.184 | 0.052 | 22.623 | *** | 0.75 | ||

| BE1 | 0.805 | 1 | 0.65 | 0.878 | 0.706 | |||

| BE2 | 0.842 | 1.11 | 0.05 | 22.347 | *** | 0.71 | ||

| BE3 | 0.872 | 1.177 | 0.049 | 24.046 | *** | 0.76 |

| AVE | Perceived Behavioral Control | Subjective Norms | Attitude | Behavioral Intent | Behavior | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived behavioral control | 0.670 | 0.818 | ||||

| Subjective norm | 0.665 | 0.634 | 0.815 | |||

| Attitude | 0.568 | 0.229 | 0.263 | 0.754 | ||

| Behavioral intent | 0.706 | 0.833 | 0.728 | 0.285 | 0.840 | |

| Behavior | 0.706 | 0.811 | 0.670 | 0.259 | 0.915 | 0.840 |

| Empty Cell | Indicators | Norm | Judgment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute fit measures | CMIN/DF | 1–3 | 2.956 |

| GFI | >0.9 | 0.938 | |

| AGFI | >0.9 | 0.913 | |

| RMSEA | <0.08 | 0.059 | |

| Incremental fit measures | NFI | >0.9 | 0.952 |

| IFI | >0.9 | 0.968 | |

| CFI | >0.9 | 0.968 | |

| Parsimonious fit measures | PNFI | >0.5 | 0.762 |

| PCFI | >0.5 | 0.774 | |

| PGFI | >0.5 | 0.662 |

| Path Coefficient | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | Non-Standard Coefficient | Standard Coefficient | S.E. | C.R. | P (*** p < 0.01) | ||

| PBC | - | BE | 0.571 | 0.543 | 0.063 | 9.022 | *** |

| CO | - | BE | 0.2 | 0.298 | 0.031 | 6.541 | *** |

| INT | - | BE | 0.081 | 0.135 | 0.021 | 3.819 | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lou, S.; Huang, J.; Zhang, D. The Mechanism of Textile Recycling Intention and Behavior Transformation: The Moderating Effect Based on Community Response. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9386. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219386

Lou S, Huang J, Zhang D. The Mechanism of Textile Recycling Intention and Behavior Transformation: The Moderating Effect Based on Community Response. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9386. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219386

Chicago/Turabian StyleLou, Sha, Junjie Huang, and Dehua Zhang. 2025. "The Mechanism of Textile Recycling Intention and Behavior Transformation: The Moderating Effect Based on Community Response" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9386. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219386

APA StyleLou, S., Huang, J., & Zhang, D. (2025). The Mechanism of Textile Recycling Intention and Behavior Transformation: The Moderating Effect Based on Community Response. Sustainability, 17(21), 9386. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219386