Abstract

This study investigates the interconnections among sustainability reporting, social performance, and firm value across the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). Employing a quantitative research design, the study utilizes firm-level data from the Refinitiv database, covering 862 firms operating in the BRICS countries from 2017 to 2022. The analysis begins with Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression and extends to models incorporating year-fixed effects and firm-fixed effects to account for heterogeneity and omitted variable bias. Robustness checks are conducted using OLS regression with robust standard errors, fixed effects regression with Driscoll–Kraay standard errors, and an instrumental variable approach to address potential endogeneity concerns. To examine the moderating role of sustainability reporting, interaction terms are incorporated into the regression models and margin plots are used for visualization. The findings reveal that social performance positively impacts firm value, underscoring the role of social responsibility in driving financial performance. Furthermore, sustainability reporting strengthens this relationship, indicating that firms with well-established reporting frameworks can effectively leverage social initiatives to enhance market valuation. Therefore, this study contributes to the literature by providing empirical evidence on the moderating effect of sustainability reporting in emerging markets. The findings offer valuable implications for policymakers, investors, and corporate leaders seeking to optimize CSR strategies and enhance firm value in dynamic economic environments.

1. Introduction

In recent years, sustainability has gained significant attention as firms are increasingly recognizing the importance of social and environmental factors in business operations [1]. Sustainability reporting has emerged as a critical mechanism for firms to disclose their social and environmental initiatives, fostering transparency and accountability. This reporting practice aligns with stakeholders’ growing demand for responsible corporate behavior and ethical business practices. Social performance, a key dimension of sustainability, reflects a firm’s commitment to social well-being, encompassing aspects such as employee welfare, community engagement, diversity, and human rights [2]. However, the extent to which social performance translates into firm value (FV) remains a subject of debate. While some studies argue that strong social performance enhances firm reputation and investor confidence [3], others contend that the associated costs may outweigh the benefits [4,5,6], leading to inconclusive results in the existing literature.

In a similar vein, the significance of sustainability reporting and its impact on business performance has gained widespread recognition. Research has extensively explored the relationship between overall sustainability reporting, its specific components, and firm performance [7]. Sustainability reporting enhances a firm’s reputation, which in turn contributes to increased firm value [8]. These reports typically encompass economic, environmental, and social indicators, all of which are non-financial. Moreover, to enhance sustainability reporting, firms prioritize improving these dimensions, particularly social aspects [9]. As a result, sustainability reporting strengthens the influence of social performance on firm value.

The moderating role of sustainability reporting in the relationship between social performance and firm value remains underexplored, particularly in the context of the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). These economies are defined by rapid industrial expansion, shifting regulatory frameworks, and growing integration into the global market. According to [9,10], over the past two decades, China maintained the highest GDP growth among the BRICS nations, but India surpassed it in the mid-2010s and is projected to lead in growth throughout the 2020s. All five countries experienced economic slowdowns during the 2008 global financial crisis and again in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, China remained the only economy to sustain growth in both periods. India also managed to expand during the Great Recession. In 2014, Brazil entered a recession driven by economic and political instability, and Russia faced a downturn due to plummeting oil prices and international sanctions. The distinct institutional settings of the BRICS countries create an intriguing backdrop for deciding whether sustainability reporting amplifies or diminishes the relationship between social performance and firm value. Due to differences in regulatory enforcement and stakeholder influence across these nations, the extent to which sustainability disclosures contribute to firm value may vary significantly. Understanding this dynamic is essential for policymakers, investors, and business leaders aiming to enhance sustainability strategies in emerging markets.

Despite the growing body of research examining the link between sustainability reporting and firm value [8,11], limited attention has been given to how sustainability reporting influences the relationship between corporate social performance (CSP) and firm value, particularly within the context of emerging economies. Prior studies have predominantly focused on developed markets, where institutional frameworks, regulatory enforcement, and stakeholder expectations are relatively mature and consistent. In contrast, the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) exhibit varied and evolving corporate governance structures, sustainability practices, and disclosure norms. These institutional differences may influence how social performance is perceived and how effectively sustainability reporting communicates a firm’s social commitments to stakeholders. However, empirical evidence exploring this moderating role of sustainability reporting in the BRICS context remains scarce.

This study addresses this gap by investigating whether sustainability reporting strengthens the relationship between corporate social performance and firm value in the BRICS economies. Specifically, the study has two core objectives: (1) to examine the direct impact of social performance on firm value; (2) to assess the moderating effect of sustainability reporting on this relationship in the BRICS nations, given their diverse institutional, economic, and regulatory settings. By pursuing these objectives, the study contributes to the literature on sustainability, corporate governance, and emerging markets, offering novel insights for both academic researchers and policymakers aiming to improve ESG-related disclosures and enhance firm value through socially responsible practices.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a review of the relevant literature and theoretical foundations. Section 3 outlines the research methodology, including data sources, variable measurement, and econometric models. Section 4 presents the empirical results and discussion. Finally, Section 5 concludes with key findings, implications, and directions for future research.

Contextual Background: Sustainability Reporting in BRICS Countries

The BRICS countries, namely Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, represent a group of emerging economies with diverse institutional environments, regulatory systems, and approaches to corporate sustainability reporting. Understanding the reporting context in each of these countries is crucial to interpreting the relationship between social performance, sustainability disclosures, and firm value.

India has taken significant regulatory steps by mandating Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) under Section 135 of the Companies Act, 2013. According to this Section, Indian companies meeting certain thresholds are required to spend at least 2% of their average net profits on CSR activities and report these expenditures [12,13]. Additionally, India’s top listed firms are subject to the Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting (BRSR) framework introduced by SEBI in 2021, which has gradually shifted CSR disclosures toward a more integrated ESG focus [14].

China has also made considerable progress in sustainability reporting. According to [15], since April 2024, the stock exchanges in Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Beijing have introduced the Sustainability Reporting Guidelines for Select Listed Companies. These guidelines require major listed firms in China to disclose information on a broad range of environmental, social, governance (ESG), and sustainable development topics. This marks a significant step toward formalizing ESG disclosure practices in China and reflects the growing regulatory emphasis on corporate transparency and sustainability. The primary objectives of these standards are to enhance the quality and reliability of sustainability information provided to investors, creditors, regulators, and other stakeholders. The guidelines aim to serve as a framework for Chinese companies to apply sustainability reporting requirements in a consistent and uniform manner [15]. Additionally, they are intended to promote standardized disclosure of environmental, social, and climate-related risks, opportunities, and impacts, thereby improving transparency and facilitating informed decision-making.

South Africa stands out in the BRICS group for its advanced and well-established approach to sustainability and integrated reporting. The adoption of the King IV Report on Corporate Governance has played a pivotal role in promoting integrated reporting practices, encouraging companies to disclose both financial and non-financial information cohesively [16]. In addition to corporate-level initiatives, South Africa has institutional mechanisms that support ongoing monitoring of corporate social investment (CSI) activities [17]. Countries are required to report biannually on their CSI programs and related expenditures. These reports are consolidated and submitted to the Group Social, Ethics, and Sustainability Committee, which oversees and evaluates progress in achieving ethical, social, and environmental objectives.

In October 2023, Brazil announced the adoption of the ISSB’s IFRS S1 and S2 disclosure standards into its regulatory framework [18]. Under the Brazilian Securities Commission’s Resolution CVM No. 193/2023, sustainability reporting is voluntary for the years 2024 and 2025 but will become mandatory in 2026 [19]. From that year onward, all listed companies and investment funds will be required to disclose sustainability and climate-related information in accordance with ISSB standards.

In Russia, ESG reporting is not mandatory. However, the government has introduced a non-binding guideline through the 2023 Order of the Ministry of Economic Development. This framework outlines 44 key sustainability indicators intended to guide companies in the voluntary disclosure of their environmental, social, and governance practices [20]. The aim is to provide a foundation for consistent and transparent reporting on corporate responsibility.

Overall, the BRICS context is characterized by a mixture of mandatory and voluntary sustainability reporting regimes, evolving regulatory landscapes, and varying levels of institutional enforcement. These differences are crucial to understanding how sustainability reporting moderates the relationship between social performance and firm value. Firms operating in more transparent and structured environments may benefit more from social initiatives, while those in less regulated settings may experience limited valuation effects due to weaker stakeholder accountability and disclosure quality.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

The relationship between social performance and firm value can be understood through the stakeholder theory. Stakeholder Theory [21] suggests that firms engaging in strong social performance activities build trust with stakeholders, ultimately enhancing firm value. Firms can foster long-term sustainability and a competitive advantage by addressing the interests of employees, customers, investors, and society [22]. According to [22], corporate social performance (CSP) refers to a series of business activities that benefit a specific social stakeholder group while ensuring that the rights and interests of other stakeholders are not compromised over time. In addition, Ref. [23] suggests that enhancing CSP can help firms attract and retain talented employees, lower costs, and improve operational efficiency. Similarly, Ref. [24] contends that a strong CSP can create new market opportunities and serve as an indicator of stronger stakeholder relationships.

In addition, Ref. [4] and other neoclassical economists argue that implementing social policies such as CSP could negatively impact firm value and shareholder wealth. Their argument is based on the notion that managers may treat corporate social investments as agency costs, diverting resources toward sustainability initiatives to fulfill personal objectives and enhance stakeholder relationships [4,5,6]. These agency costs may surpass the potential benefits, leading to a competitive disadvantage and adversely affecting financial performance [25].

The conflict-resolution hypothesis, rooted in stakeholder theory, suggests that if managers implement effective sustainability monitoring mechanisms to mitigate conflicts of interest among stakeholders, firm value will be positively associated with social performance. Firms’ sustainability reporting plays a crucial role in lowering agency costs by enhancing stakeholder relationships and reducing information asymmetry [26]. Sustainability reporting plays a vital role in communicating social policies and corporate social performance to stakeholders, fostering stronger firm-stakeholder relationships and helping to reduce agency costs.

2.2. Corporate Social Performance and Firm Value

The relationship between corporate social performance and firm value has been a subject of ongoing debate. In certain countries, integrating social objectives into corporate communications is seen as an essential strategy for enhancing a company’s public image, particularly among key stakeholders such as shareholders, consumers, and the broader community [27]. Scholars who support this view contend that strong social performance can enhance firm value by fostering positive stakeholder relationships, building reputational capital, and strengthening the company’s market image—all of which are crucial to maintaining a competitive advantage and driving financial success [21,28,29].

Prior empirical studies present mixed evidence on the relationship between social performance and firm value. Some researchers find that high social performance enhances brand reputation, customer loyalty, and risk mitigation, ultimately improving financial value [3,7]. Several studies [23,30,31,32] have reported a positive link between CSP and firm performance. For instance, Ref. [33] examined composite ESG scores and individual ESG pillars across Asia, Europe, and Africa, using Tobin’s Q as a proxy for firm value, and found a positive effect of the social pillar. These results align with the view that stakeholders increasingly expect firms to actively engage in social initiatives [34] and that meeting such expectations is rewarded by the market. Similarly, Ref. [35] found that environmental, social, and governance scores, particularly the social component, positively influence firm value, while Ref. [36] confirmed that higher CSP is associated with stronger market valuations.

Conversely, other research challenges this positive association. Using Refinitiv data, Ref. [37] reported a negative relationship between the social pillar and firm value, suggesting that substantial investments in employee welfare, community engagement, or diversity may not yield immediate financial returns and can be perceived as cost burdens that reduce short-term profitability. Likewise, Ref. [38] noted that allocating greater resources and managerial effort to social initiatives may detract from core business operations, potentially leading to a negative correlation with firm value. Some studies even find no significant relationship between CSP and financial performance [37]. These variations suggest that contextual factors—such as industry characteristics, stakeholder expectations, and the time horizon of returns—play a critical role in shaping the CSP–value link.

Evidence also points to the moderating influence of environmental and institutional conditions. For example, Ref. [39] found that CSP has a stronger impact on firm performance in dynamic, resource-abundant contexts. This is particularly relevant for the BRICS economies, which are marked by weaker market structures, institutional uncertainty, and symbolic adaptation behaviors [40]. Under such conditions, firms may adopt socially responsible practices to align with perceived norms or secure legitimacy, even when the financial benefits are uncertain.

Overall, the literature indicates that the CSP–firm value relationship is both inconclusive and context-dependent. While many studies in developed economies highlight the reputational and stakeholder trust benefits of CSP, others emphasize the cost implications and potential trade-offs. The limited research on BRICS countries, characterized by diverse governance systems, evolving regulatory frameworks, and varying stakeholder demands leaves a gap in understanding how these factors shape the relationship. This study addresses that gap by examining the effect of corporate social performance on firm value in BRICS nations from 2017 to 2022, a period marked by increasing global emphasis on ESG practices. In this context, strong CSP is expected to help firms cultivate stakeholder and government relationships, enhance resource access, and strengthen market value. Based on this reasoning, we propose:

H1.

Corporate social performance has a significantly positive impact on firm value across BRICS countries.

2.3. Sustainability Reporting, Corporate Social Performance, and Firm Value

Sustainability reporting bridges CSP and firm value by making social commitments visible to stakeholders, thereby reducing information asymmetry and boosting investor confidence. Firms with robust sustainability disclosures often enjoy lower capital costs and greater investor trust. The effectiveness of reporting, however, varies across institutional settings.

Through sustainability reporting, companies signal their commitment to ESG principles [1,41,42,43], attract ethically minded investors [44], and differentiate themselves in a market that increasingly values transparency [45]. This aligns with the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) framework, which emphasizes “People, Planet, and Profit” as interconnected objectives [46,47]. By demonstrating balanced attention to social and environmental concerns, firms enhance their reputation and, ultimately, firm value [11].

Extensive research has explored the direct relationship between corporate social performance (CSP) and firm value, yet the moderating role of sustainability reporting in this relationship remains underexplored. Although sustainability reporting is increasingly recognized as a tool for enhancing transparency, stakeholder trust, and reputational capital, very few studies have empirically examined whether and how such disclosures strengthen the influence of social performance on firm value. Most existing literature treats sustainability reporting and social performance as independent predictors of firm value, overlooking the potential interactive effect between them. Furthermore, in the context of emerging markets, particularly the BRICS countries, where institutional frameworks and reporting standards vary significantly, the role of sustainability reporting as a mechanism that amplifies the impact of CSP on firm outcomes has not been sufficiently investigated. This study seeks to address this gap by analyzing whether sustainability reporting serves as a positive moderator in the relationship between social performance and firm value.

H2.

Sustainability reporting significantly strengthens the impact of social performance on firm value.

3. Methodology

This study has adopted a quantitative research design, utilizing firm-level data sourced from the Refinitiv database for 862 firms operating across the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) over the period from 2017 to 2022. The initial dataset comprised 13,048 firms, totaling 130,480 firm-year observations. After excluding entries with missing values for the variables of interest, the final balanced panel consisted of 862 firms with 5172 observations. The selected firms span a wide range of industries, including manufacturing, utilities, consumer goods, services, energy, real estate, and technology, thereby providing a comprehensive cross-industry coverage suitable for robust corporate finance and governance analysis.

The country-wise distribution of observations included 3312 from China, 1134 from India, 318 from Brazil, 306 from South Africa, and 102 from Russia. The selection of the BRICS countries is particularly significant due to their increasing economic influence, diverse institutional environments, and evolving corporate governance structures. As emerging economies, the BRICS nations encounter unique challenges in balancing economic development with corporate social responsibility, making them an ideal context for analyzing the relationship between corporate social performance and firm value.

The period from 2017 to 2022 was selected for this study due to its alignment with major global and national developments in sustainability reporting and corporate social responsibility. This timeframe captures the post-adoption phase of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, the rise of globally accepted ESG disclosure standards (such as GRI, SASB, and TCFD), and significant regulatory and institutional changes in the BRICS countries. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic between 2020 and 2022 further amplified the importance of social performance and transparent stakeholder communication. These developments collectively created a context in which firms’ social responsibility initiatives and their reporting practices were more likely to influence investor perceptions and firm value, making this period particularly relevant for examining the moderating role of sustainability reporting in the relationship between social performance and firm value.

The dependent variable in this study, firm value, was measured using Tobin’s Q (TQ), a widely recognized financial metric for assessing a company’s market valuation relative to its assets. This selection is consistent with the prior literature [33,35]. Tobin’s Q is calculated as the ratio of a firm’s market capitalization plus total debt to its total assets. This measure serves as an indicator of how effectively a company utilizes its assets to generate market value. A higher Tobin’s Q suggests that investors perceive the firm as having strong growth potential and effective management, whereas a lower value may indicate undervaluation or inefficiencies in asset utilization. By employing Tobin’s Q, this study ensures a robust assessment of firm value that integrates both market expectations and financial fundamentals, providing a comprehensive perspective on the impact of corporate social performance on firm valuation.

The independent variable, social performance score (SOC), represents the social pillar of ESG performance, as sourced from the Refinitiv database. This pillar evaluates a company’s ability to foster trust and loyalty among its employees, customers, and broader society by implementing best management practices [48]. It serves as an indicator of the company’s reputation and social license to operate, both of which are crucial in ensuring long-term sustainability and shareholder value. A strong social performance score suggests that a firm effectively manages its stakeholder relationships, thereby enhancing its market position and overall financial resilience. This variable selection is also aligned with the prior literature [36,37].

The moderating variable, sustainability reporting score [41], reflects the extent to which firms disclose their corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives, policies, and sustainability practices in a transparent and structured manner. A higher CSR sustainability reporting score indicates that a company is committed to accountability and ethical business practices, actively communicating its social and environmental efforts to stakeholders. By providing detailed and reliable CSR disclosures, firms can enhance stakeholder trust, reduce information asymmetry, and mitigate agency costs, ultimately influencing their financial valuation. The moderating effect of CSR reporting is crucial, as it determines whether greater transparency in social performance strengthens or weakens its impact on firm value across firms operating in BRICS countries.

The control variables included in this study are audit tenure, board-specific skill, audit expertise, firm size, and leverage, each selected to account for firm-specific and governance-related factors that may influence the relationship between social performance and firm value.

- Audit Tenure (ATEN): Represents the number of years the current auditor has been serving the organization. A longer audit tenure may lead to improved financial reporting quality due to the auditor’s deeper understanding of the firm’s operations, but it may also increase the risk of complacency and reduce auditor independence.

- Board-specific skill (BSS): Measured as a percentage of board members who have either an industry-specific background or a strong financial background. A highly skilled board is better equipped to oversee sustainability initiatives, mitigate risks, and enhance decision-making processes, potentially influencing firm value.

- Audit Expertise (AEXP): Refers to the proficiency and industry-specific knowledge of the external auditor. This variable is measured as a dichotomous variable (binary: 0 or 1). It is coded as 1 if the company has an audit committee with at least three members and at least one “financial expert” (as defined by the Sarbanes–Oxley Act), and 0 otherwise. Firms with auditors who specialize in their sector may benefit from enhanced financial transparency and compliance with regulatory standards, which can contribute to investor confidence and firm valuation.

- Firm Size (FSIZE): Typically measured by the natural logarithm of total assets, firm size is a critical determinant of financial performance. Larger firms tend to have more resources, better access to capital markets, and greater capacity for implementing sustainability initiatives, which may impact firm value.

- Leverage (LEV): Defined as the ratio of total debt to total assets; leverage reflects a firm’s financial risk and capital structure. Highly leveraged firms may face constraints in allocating resources to sustainability-related activities due to financial obligations, potentially affecting their social performance and overall valuation.

By incorporating these control variables, the study aims to isolate the impact of social performance on firm value while accounting for other factors that may influence financial outcomes, ensuring a more robust and reliable empirical analysis. Moreover, to address potential outliers and improve the robustness of the analysis, all continuous variables are winsorized at a 2% level.

Statistical Models

The analysis employs multiple regression techniques, beginning with Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression. To account for potential heterogeneity and omitted variable bias, the researcher extended the model to include year-fixed effects and a more comprehensive model with both year and firm-fixed effects. Robustness checks were conducted using OLS regression with robust standard errors, fixed effects regression with Driscoll–Kraay standard errors, and an instrumental variable approach to address potential endogeneity concerns. To further explore the moderating role of sustainability reporting, interaction terms were included in the regression models, and margin plots were used to visualize the effects. These methodological approaches ensure the reliability and validity of the findings, contributing to a deeper understanding of the moderating role of a sustainability score on the relationship between corporate social performance and firm value in emerging economies. The investigated models are expressed in the equations as follows:

4. Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables used in the analysis. The mean value of firm value is 2.17, with a standard deviation of 2.58, indicating significant variability among firms. Social performance has a mean of 37.34, while sustainability reporting averages 44.92, suggesting that firms exhibit varying levels of engagement in social and sustainability-related activities. The average audit tenure is approximately 3.75, with a maximum value of 16. Board-specific skill has a mean of 41.68, suggesting firms with a higher percentage of boards with specific skills. Firm size averages 9.55, leverage has a mean of 0.26, and audit expertise shows a mean of 0.79, indicating that most firms have audit committees with expertise.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

4.2. Correlation Analysis

Table 2 presents the pairwise correlations between the variables. Notably, firm value is negatively correlated with social performance (−0.030, p < 0.05) and sustainability reporting (−0.128, p < 0.01), suggesting that higher social and CSR engagement may be associated with lower firm value. Audit tenure and board-specific skills show positive correlations with social and CSR factors, indicating that firms with board expertise and audit members with longer tenure tend to engage more in social and sustainability practices. Leverage has a significant negative correlation with board size and social performance, implying that highly leveraged firms may engage less in these activities. However, variance inflation factors (VIFs) indicate no significant multicollinearity concerns, as all values are below the threshold of 10 (see Table 3) [9].

Table 2.

Pairwise correlations.

Table 3.

Direct effect.

4.3. Regression Analysis

4.3.1. Direct Effect

Table 3 presents the results of the OLS regression models assessing the direct effect of social performance on firm value, using alternative specifications that incorporate firm- and year-fixed effects. Across all models, the coefficient for social performance is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level, confirming a robust association with firm value. Specifically, a one-unit increase in social performance is associated with increases in firm value of 0.009, 0.010, and 0.005, respectively, across different model specifications. These findings are economically meaningful, indicating that improvements in social responsibility initiatives, such as community engagement, employee welfare, and human rights practices, translate into tangible market value for firms.

The reduction in coefficient magnitude after the inclusion of firm-fixed effects suggests that time-invariant firm-specific characteristics explain part of the variation, yet the relationship remains significant, highlighting the independent contribution of social performance to firm value. This supports Hypothesis 1 (H1) and aligns with stakeholder theory, which posits that firms generating value for a wide range of stakeholders, beyond just shareholders, benefit from a stronger reputation, customer loyalty, and reduced risk exposure, all of which enhance firm valuation [21,28].

These findings are consistent with earlier studies, such as Ting et al. (2019) [35] and Aydoğmuş et al. (2022) [33], who also reported a significant positive relationship between the social pillar of ESG performance and firm value using Tobin’s Q as a proxy. Similarly, Luffarelli et al. (2019) [36] demonstrated that firms with higher social performance ratings tend to receive favorable investor evaluations, reinforcing the market’s appreciation for socially responsible conduct. However, the magnitude of the coefficients in this study is somewhat lower than those reported in more developed markets, possibly reflecting the institutional and regulatory differences in the BRICS countries, where stakeholder expectations and enforcement mechanisms around social responsibility are still evolving.

Concerning the control variables, audit tenure exhibits a positive and significant effect on firm value, implying that longer audit relationships may contribute to greater financial transparency and trust, thus enhancing firm valuation. Conversely, firm size and leverage display negative and significant relationships with firm value. The negative coefficient for firm size may reflect diseconomies of scale or complexity in larger firms, while high leverage can indicate greater financial risk, both of which may reduce investor confidence and firm valuation.

The inclusion of both firm- and year-fixed effects significantly improves model fit, as reflected by increased R-squared values, suggesting that the model effectively controls for unobserved heterogeneity across firms and over time. Overall, the results provide robust evidence for the beneficial role of corporate social performance in enhancing firm value, particularly in the context of emerging economies, where effective stakeholder engagement can serve as a source of competitive advantage.

4.3.2. Moderating Effect

Table 4 presents the results examining the moderating effect of sustainability reporting on the relationship between corporate social performance and firm value. The interaction term between sustainability reporting (CSR) and social performance (SOC) is positive and statistically significant across all model specifications, providing strong evidence that sustainability reporting strengthens the positive effect of social performance on firm valuation. This supports Hypothesis 2 (H2), confirming that firms that both perform well socially and disclose such efforts transparently tend to be more highly valued by the market.

Table 4.

Moderating effect.

From a statistical standpoint, the consistent significance of the interaction term across models enhances the robustness of the results. Economically, the interaction effects reveal that a one-unit increase in both sustainability reporting and social performance leads to a 0.004 and 0.002 increase in firm value, depending on the specification. While these marginal effects may appear modest, in the context of large firms and capital markets, even small improvements in valuation can represent significant financial gains. This implies that the value generated from social performance is further amplified when stakeholders can clearly observe and assess these efforts through structured disclosures.

These findings align well with stakeholder theory and the signaling perspective, suggesting that transparent CSR reporting serves as a credible signal of a firm’s long-term commitment to sustainability, ethical practices, and social impact. By publicly disclosing social initiatives, firms reduce information asymmetry and build reputational capital, thereby gaining greater investor trust and potentially attracting a broader base of socially responsible investors. These results are consistent with prior studies [1,11,41], which emphasized that effective sustainability disclosures enhance stakeholder confidence and firm credibility.

Furthermore, the results resonate with recent literature (e.g., [8,42]), highlighting that sustainability reporting improves market perception and positively influences investment decisions, particularly in institutional contexts where formal ESG disclosure regulations may be weaker or voluntary, as is often the case in the BRICS countries. In such environments, voluntary disclosure becomes a strategic tool for firms to distinguish themselves and signal accountability.

From a practical perspective, these findings underscore the strategic importance of integrating sustainability reporting with social performance initiatives. Firms that invest in social responsibility must also adopt transparent, standardized, and reliable disclosure practices to fully capitalize on their non-financial efforts. For managers, this highlights the dual need for both substantive action and clear communication. For investors, the presence of detailed sustainability reports can act as a decision-making tool, indicating responsible management and long-term orientation.

In addition, the findings carry policy implications, particularly for emerging markets. Regulators and standard-setting bodies may consider introducing or reinforcing mandatory sustainability disclosure requirements. Doing so could promote more consistent transparency, reduce market uncertainty, and ultimately foster more sustainable financial systems.

Overall, the results clearly demonstrate that sustainability reporting plays a strengthening moderating role in the social performance–firm value relationship. This reinforces the argument that financial value is not just derived from performing socially responsible actions, but also from communicating them effectively. The study contributes important empirical evidence from the underexplored BRICS context, offering valuable insights for corporate leaders, investors, and policymakers aiming to align financial and social goals.

4.4. Robustness Analysis

Table 5 presents robustness tests using OLS with robust standard errors and fixed effects with Driscoll–Kraay standard errors. The results remain largely consistent, with social performance continuing to have a positive impact on firm value in direct effect models. The moderating effect of sustainability reporting remains positive and significant, reinforcing the previous findings. The inclusion of robust standard errors reduces standard errors, increasing confidence in the estimated coefficients.

Table 5.

Robustness analysis.

Table 6 employs an instrumental variable approach to address potential endogeneity concerns. The direct effect model confirms the positive impact of social performance on firm value, with a slightly higher coefficient compared to OLS estimates. The moderating effect of sustainability reporting remains significant, indicating that firms heavily engaged in sustainability reporting may experience an improved firm valuation. The results validate the robustness of the findings and suggest that social performance and sustainability strategies are essential components of firm value creation.

Table 6.

Instrumental variables (2SLS).

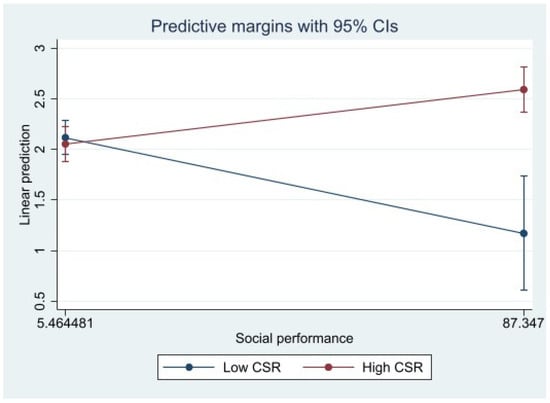

The margin plot (Figure 1) illustrates the moderating role of sustainability reporting on the relationship between social performance and firm value. The results indicate a clear divergence in trends based on the level of sustainability reporting. Firms with high sustainability reporting exhibit a positive relationship between social performance and firm value, suggesting that as social performance increases, firm value also improves. Conversely, firms with low sustainability reporting experience a negative relationship, where higher social performance is associated with lower firm value. This finding underscores the importance of sustainability reporting in reinforcing the financial benefits of social performance. The results highlight that sustainability reporting enhances the transparency and credibility of a firm’s social initiatives, thereby strengthening stakeholder trust and ultimately contributing to firm value.

Figure 1.

Margin plot.

Overall, the results indicate that social performance positively influences firm value, and sustainability reporting plays a crucial moderating role in this relationship. The findings underscore the importance of board activeness and governance mechanisms in shaping firm performance. The robustness checks and instrumental variable approach confirm the validity of the results, providing strong evidence for the role of sustainability strategies in financial outcomes. These findings highlight that firms can strategically use sustainability reporting to enhance the financial benefits of their social performance initiatives.

5. Discussion, Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Discussion

The results of this study provide important theoretical and practical insights into the link between corporate social performance, sustainability reporting, and firm value in the BRICS economies. Each hypothesis is considered below within the relevant theoretical frameworks.

H1 predicted that higher social performance would be positively associated with firm value. This hypothesis is strongly supported by the regression results, which remained robust across multiple specifications. From a stakeholder theory perspective, firms that invest in initiatives such as employee welfare, community engagement, and human rights practices generate value for a broad range of stakeholders, thereby enhancing reputation, strengthening legitimacy, and reducing operational risks. These benefits, in turn, contribute to improved market valuations. The results are also consistent with signaling theory in that observable social performance initiatives can signal a firm’s commitment to long-term value creation, especially when stakeholders face uncertainty about corporate intentions.

H2 proposed that sustainability reporting would positively moderate the relationship between social performance and firm value. The evidence supports this hypothesis, showing that the association between social performance and firm value is significantly stronger when sustainability activities are transparently reported. Within signaling theory, such reporting acts as a costly and credible signal, especially in emerging markets where institutional enforcement mechanisms are less developed. Under agency theory, the transparency afforded by sustainability reporting helps reduce information asymmetry between managers and shareholders, constraining managerial opportunism and aligning corporate actions with investor and societal expectations.

An interesting methodological point emerges from the contrast between the descriptive statistics and regression results. The raw correlations showed a negative relationship between social performance and firm value, whereas the regression analysis revealed a strong positive effect after controlling for relevant firm characteristics. This apparent contradiction can be explained by the possibility that some firms invest in CSR reactively, often after reputational damage or financial decline, creating a short-term negative association in simple correlations. When controlling for these confounding effects, the underlying long-term positive relationship becomes clear. This suggests the presence of threshold or non-linear effects, whereby only sustained and strategically integrated CSR efforts coupled with credible disclosure yield positive market rewards.

Overall, the integration of stakeholder, signaling, and agency perspectives provides a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms at play. Stakeholder theory explains why firms benefit from meeting societal expectations; signaling theory clarifies how sustainability reporting enhances the credibility of those actions; and agency theory highlights the role of transparency in aligning managerial and shareholder interests. These combined insights show that in the BRICS economies, social performance and sustainability reporting are not simply compliance exercises, they are strategic levers for long-term value creation in evolving institutional environments.

5.2. Conclusions

The growing global emphasis on sustainability has prompted many companies to adopt sustainability reporting as a strategic tool to engage stakeholders and maintain legitimacy. Social performance, as a core dimension of sustainability disclosure, encourages firms to improve their societal contributions while enhancing corporate reputation. Nevertheless, there remains debate over whether such disclosures reflect genuine commitment or are merely symbolic gestures.

This study examined the effect of corporate social performance (CSP) on firm value and explored the moderating role of sustainability reporting using evidence from the BRICS countries between 2017 and 2022. The results consistently demonstrate that CSP has a positive and statistically significant impact on firm value, highlighting the increasing influence of socially responsible practices on market perceptions and financial outcomes. Moreover, sustainability reporting strengthens this relationship, suggesting that firms which actively invest in social initiatives and transparently communicate their efforts are more likely to be rewarded with higher valuations.

The robustness of these findings is supported by multiple econometric approaches, including OLS with robust standard errors and a two-stage least squares (2SLS) instrumental variable method. While the study focuses on the BRICS economies, the implications extend globally due to the universal relevance of sustainability in achieving balanced economic and environmental progress. The application of the internationally recognized GRI framework further enhances the comparability and global relevance of the findings.

5.3. Theoretical Implication

This research advances the literature on CSP, sustainability reporting, and firm value in several ways. First, drawing on stakeholder theory, the findings demonstrate that firms aligning social initiatives with stakeholder expectations enhance their reputation, legitimacy, and long-term value. Transparent sustainability practices build trust, reduce conflict with stakeholders, and support sustainable development objectives. Second, the results reinforce signaling theory by showing that sustainability reporting, when integrated with strong social performance, functions as a credible, costly, and informative signal to the market. Such disclosures reduce information asymmetry, convey corporate priorities, and differentiate firms from less committed peers. Finally, by combining stakeholder and signaling perspectives, the study offers an integrated framework explaining how firms, particularly in emerging economies, can leverage sustainability practices and transparent reporting to strengthen stakeholder relationships, enhance legitimacy, and increase firm value.

5.4. Managerial and Policy Implication

5.4.1. Managerial Implications

For corporate managers in the BRICS economies, the findings underline the strategic importance of embedding social performance and sustainability reporting into core business operations rather than treating them as compliance exercises. High-quality, transparent reporting should be viewed as an investment that can build investor confidence, attract socially conscious capital, and foster long-term competitiveness. Managers should actively engage with stakeholders, especially local communities and investors, to ensure that sustainability initiatives address relevant social needs and generate measurable impact.

For investors, the results suggest that CSP combined with credible sustainability reporting can serve as a reliable indicator of a firm’s long-term value potential and risk profile. Investment decision-making can therefore integrate ESG metrics not only as ethical criteria but also as predictors of financial performance.

5.4.2. Policy Implications

From a policy perspective, harmonizing national reporting requirements with global frameworks such as the GRI can improve the consistency, comparability, and reliability of sustainability disclosures. Governments can incentivize comprehensive social sustainability practices through tax benefits, subsidies, or preferential financing for firms meeting high reporting and performance standards. Regulatory authorities should also mandate periodic audits of sustainability reports to discourage greenwashing and ensure that disclosures reflect actual practices.

Given the global momentum toward ESG policy convergence, the BRICS economies have an opportunity to take a leadership role by aligning their reporting frameworks with international norms. Such harmonization could enhance global investor confidence, promote accountability, and accelerate the transition toward a more sustainable economic model.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research Researches

This study has several limitations. First, the reliance on secondary data may introduce measurement bias, as reported figures depend on firms’ disclosure practices. Second, the analysis does not explicitly account for contextual variables such as cultural norms, institutional quality, or industry-specific factors, which may influence the CSP–firm value relationship. Third, although the findings are relevant beyond the BRICS economies, differences in institutional environments may limit direct generalization to developed markets. Future research could address these limitations in several ways. First, by conducting comparative studies between emerging and developed markets to test the robustness of the findings. Second, by incorporating qualitative methods, such as interviews or case studies, to provide deeper insights into the mechanisms linking CSP, reporting, and value creation. Third, by examining potential mediating or moderating factors, such as institutional quality, stakeholder activism, or regulatory enforcement, in shaping the effectiveness of sustainability initiatives.

Funding

This research received funding from the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, under the grant J:71-245-1441. The author, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR for the technical and financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon request to the corresponding author. Additional materials are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sahu, M.; Alahdal, W.M.; Pandey, D.K.; Baatwah, S.R.; Bajaher, M.S. Board Gender Diversity and Firm Performance: Unveiling the ESG Effect. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouslah, K.; Kryzanowski, L.; M’Zali, B. The Impact of the Dimensions of Social Performance on Firm Risk. J. Bank. Financ. 2013, 37, 1258–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y.L.; Jiang, K.; Mak, B.S.C.; Tan, W. Corporate Social Performance, Firm Valuation, and Industrial Difference: Evidence from Hong Kong. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. In Corporate Social Responsibility; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. Value Maximisation, Stakeholder Theory, and the Corporate Objective Function. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2001, 7, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, C.J.; Santaló, J.; Diestre, L. Corporate Governance and the Environment: What Type of Governance Creates Greener Companies? J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 492–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.J.; Sethuraman, K.; Lam, J.Y. Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Dimensions on Firm Value: Some Evidence from Hong Kong and China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.Z.A.; Akbar, S.; Zhu, X. Mandatory CSR Disclosure, Institutional Ownership and Firm Value: Evidence from China. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 30, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, M.; Prusty, T.; Alahdal, W.M.; Ariff, A.M.; Almaqtari, F.A.; Hashim, H.A. The Role of Education in Moderating the Impact of Development on Environmental Sustainability in OECD Countries. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, A. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Growth Rate in the BRICS Countries 2000–2029. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/741729/gross-domestic-product-gdp-growth-rate-in-the-bric-countries/ (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Tasnia, M.; Syed Jafaar Alhabshi, S.M.B.; Rosman, R.; Kabir, M.R. Corporate Social Responsibility and the Financial Performance of Global Banks: The Moderating Role of Corporate Tax. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2025, 15, 644–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyrill, M. Corporate Social Responsibility in India. Available online: https://www.india-briefing.com/news/corporate-social-responsibility-india-5511.html/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Department of Public Enterprises. Guidelines on Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability for Central Public Sector Enterprises. Available online: https://dpe.gov.in/sites/default/files/Guidelines_on_CSR_SUS_2014.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- PWC. Navigating India’s Transition to Sustainability Reporting. 2024. Available online: https://www.pwc.in/assets/pdfs/navigating-indias-transition-to-sustainability-reporting.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Chiam, L. China Published the Sustainability Disclosure Standards for Businesses. Available online: https://www.complianceandrisks.com/blog/china-has-published-the-sustainability-disclosure-standards-for-businesses/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- van der Lugt, C.; Malan, D. Making Investment Grade: The Future of Corporate Reporting. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/651Making_Investment_Grade.pdf#page=4.00 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Standard Bank Group. Sustainability Disclosures Report. Available online: https://www.standardbank.com/static_file/StandardBankGroup/filedownloads/RTS/2023/SBG_SustainabilityDisclosuresReport2023.pdf#page=95.16 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- de Oliveira, R.F.; Rossit, L.A. ESG Compliance in Action in the Brazilian Life Sciences Industry. Available online: https://www.ibanet.org/esg-compliance-brazil-life-sciences (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Thurston, C. Brazil Adopts Sustainability Reporting Requirement. Available online: https://www.coatingsworld.com/brazil-adopts-sustainability-reporting-requirement/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Kuzmin, E.; Rakhimova, G.; Nasirova, H.; Namozov, J. Assessing the Spread and Coverage of ESG Practices in Russian Companies. Front. Sustain. 2025, 6, 1574190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hamoudah, M.M.; Banhmeid, B.; Alahdal, W.M.; Sahu, M. Corporate Governance and Emission Performance: Malaysian Evidence on the Moderating Role of Environmental Innovation. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Ahuja, G. Does It Pay to Be Green? An Empirical Examination of the Relationship between Emission Reduction and Firm Performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 1996, 5, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Van Der Linde, C. Green and Competitive: Ending the Stalemate Harvard Business Review; Harvard Business Publishing: Brighton, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kampoowale, I.; Kateb, I.; Salleh, Z.; Alahdal, W.M. Board Gender Diversity and ESG Performance: Pathways to Financial Success in Malaysian Emerging Market. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M. Instrumental Stakeholder Theory: A synthesis of ethics and economics. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 404–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usunier, J.C.; Furrer, O.; Furrer-Perrinjaquet, A. The Perceived Trade-off between Corporate Social and Economic Responsibility: A Cross-National Study. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2011, 11, 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowell, G.; Hart, S.; Yeung, B. Do Corporate Global Environmental Standards Create or Destroy Market Value? Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 1059–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Keim, G.D. Shareholder Value, Stakeholder Management, and Social Issues: What’s the Bottom Line? Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğmuş, M.; Gülay, G.; Ergun, K. Impact of ESG Performance on Firm Value and Profitability. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2022, 22, S119–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, M.; Alahdal, W.M.; Baatwah, S.R.; Elbanna, S. Governance and Green Energy: Unveiling Their Impact on Sustainable Development in OECD Countries. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, I.W.K.; Azizan, N.A.; Bhaskaran, R.K.; Sukumaran, S.K. Corporate Social Performance and Firm Performance: Comparative Study among Developed and Emerging Market Firms. Sustainability 2019, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luffarelli, J.; Markou, P.; Stamatogiannakis, A.; Gonçalves, D. The Effect of Corporate Social Performance on the Financial Performance of Business-to-Business and Business-to-Consumer Firms. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1333–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawęda, A. Does Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance Elevate Firm Value? International Evidence. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 73, 106639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R.D.; Whybark, D.C. Environmental Management in Operations: The Selection of Environmental Technologies. Decis. Sci. 1999, 30, 601–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goll, I.; Rasheed, A.A. The Moderating Effect of Environmental Munificence and Dynamism on the Relationship between Discretionary Social Responsibility and Firm Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 49, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kateb, I.; Alahdal, W.M. Tracing the Path to Sustainable Governance: CSR Committees as Mediators of Board Impact on ESG Performance in the MENA Region. Corp. Gov. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werastuti, D.N.S.; Atmadja, A.T.; Adiputra, I.M.P. Value Relevance of Sustainability Report and Its Impact on Value of Companies. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Tourism, Economics, Accounting, Management, and Social Science (TEAMS 2021); Atlantis Press International B.V.: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahdal, W.M.; Farhan, N.H.S.; Vishwakarma, R.; Hashim, H.A. The Moderating Role of CEO Power on the Relationship between Environmental, Social and Governance Disclosure and Financial Performance in Emerging Market. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 85803–85821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahdal, W.M.; Muhmad, S.N.; Farhan, N.H.S.; Almaqtari, F.A.; Mhawish, A.; Hashim, H.A. Unveiling the Impact of Firm-Characteristics on Sustainable Development Goals Disclosure: A Cross-Country Study on Non-Financial Companies in Asia. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2024, 24, 916–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahdal, W.M.; Hashim, H.A.; Almaqtari, F.A.; Salleh, Z.; Pandey, D.K. The Moderating Role of Board Gender Diversity in ESG and Firm Performance: Empirical Evidence from Gulf Countries. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2024, 7, e70004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, M.; Mishra, A. Impact of Country-Level Environmental, Social and Governance Pillars on Sustainable Development Goals: Evidence from G20 Countries. Int. J. Account. Bus. Financ. 2023, 3, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, M.S. Sustainability: An Overview of the Triple Bottom Line and Sustainability Implementation. Int. J. Strateg. Eng. 2019, 2, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Hazaea, S.A.; Alsayegh, M.F.; Sahu, M.; Raid, M.; Al-Ahdal, W.M. Media Coverage as a Moderator in the Nexus between Audit Quality and ESG Performance: Evidence from China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0312510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).