Management Commitment to Compliance with Occupational Safety and Health Laws and Regulations in Polish Rock Mining Companies

Abstract

1. Introduction

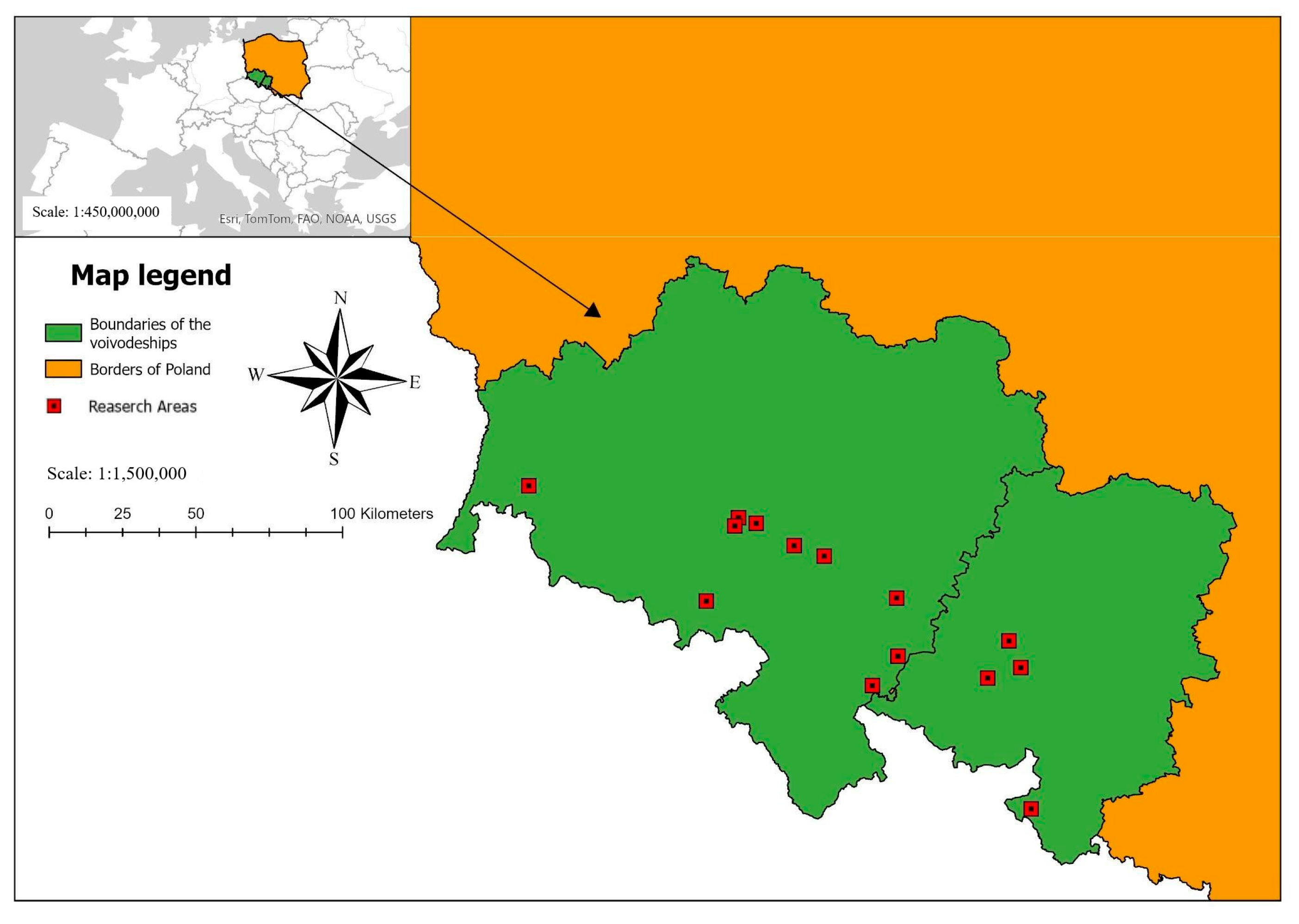

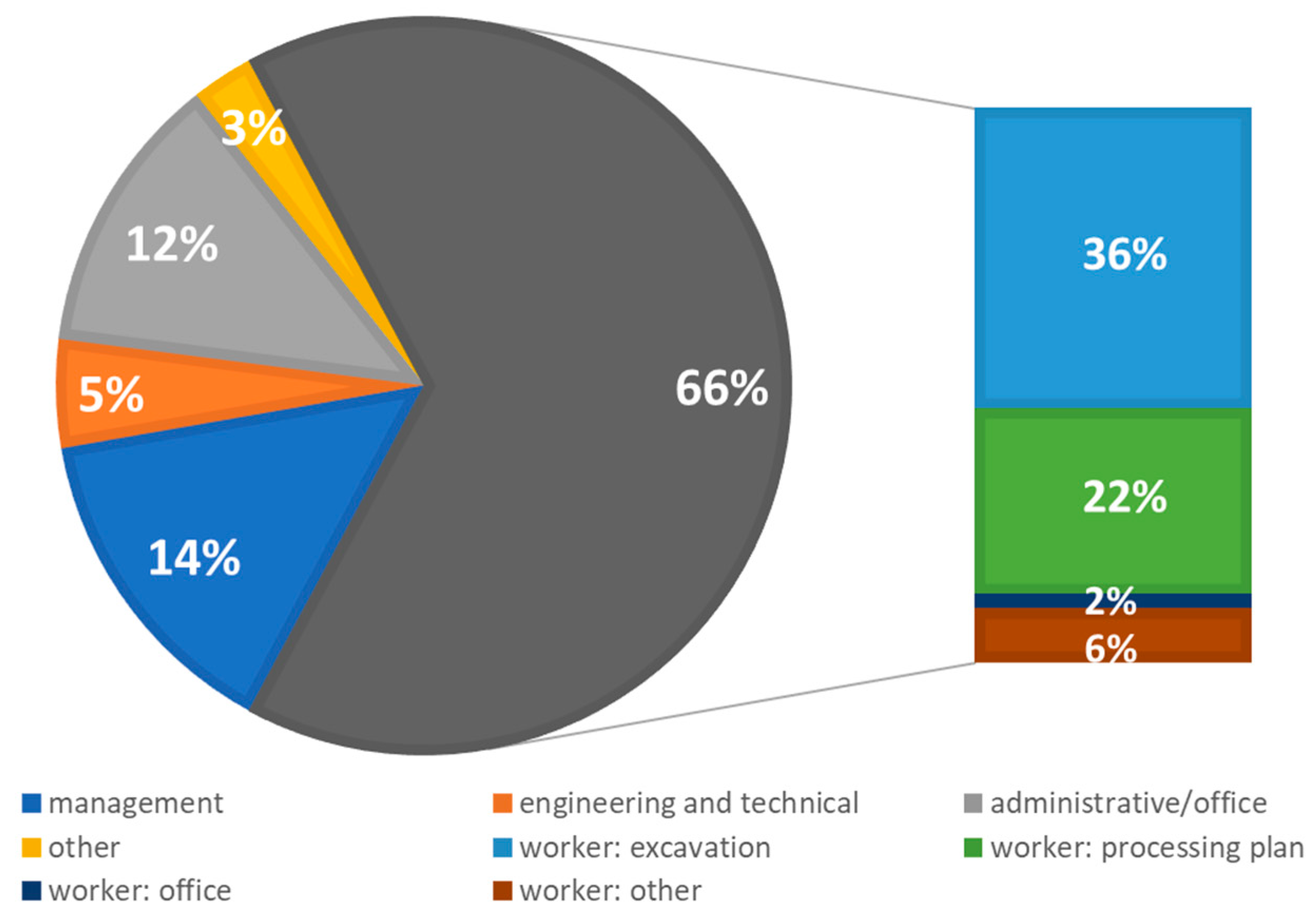

2. Research Area and Methodology

- n—sample size,

- u—critical value of normal distribution,

- d—statistical error,

- α = 0.05 (confidence level 0.95),

- d = 0.10 (statistical error 10%),

- = 1.96 (from tables).

| Number of Statement | Survey Statement |

|---|---|

| 1 | Managers comply with occupational safety and health regulations. |

| 2 | In my workplace, audits are performed to control OSH levels on a regular basis. |

| 3 | Taking safe actions/safe behaviour is appreciated by leaders. |

| 4 | Taking risky actions/unsafe behaviours to achieve the norm is favoured by leaders. |

| 5 | Personal protective equipment is available and used at the workplace where I work. |

| 6 | Collective protection measures are available and used in the workplace where I work. |

| 7 | The level of OSH at my workplace is increasing. |

| 8 | If OSH regulations were no longer in existence and employees performed work at their own discretion the number of accidents at work would not change. |

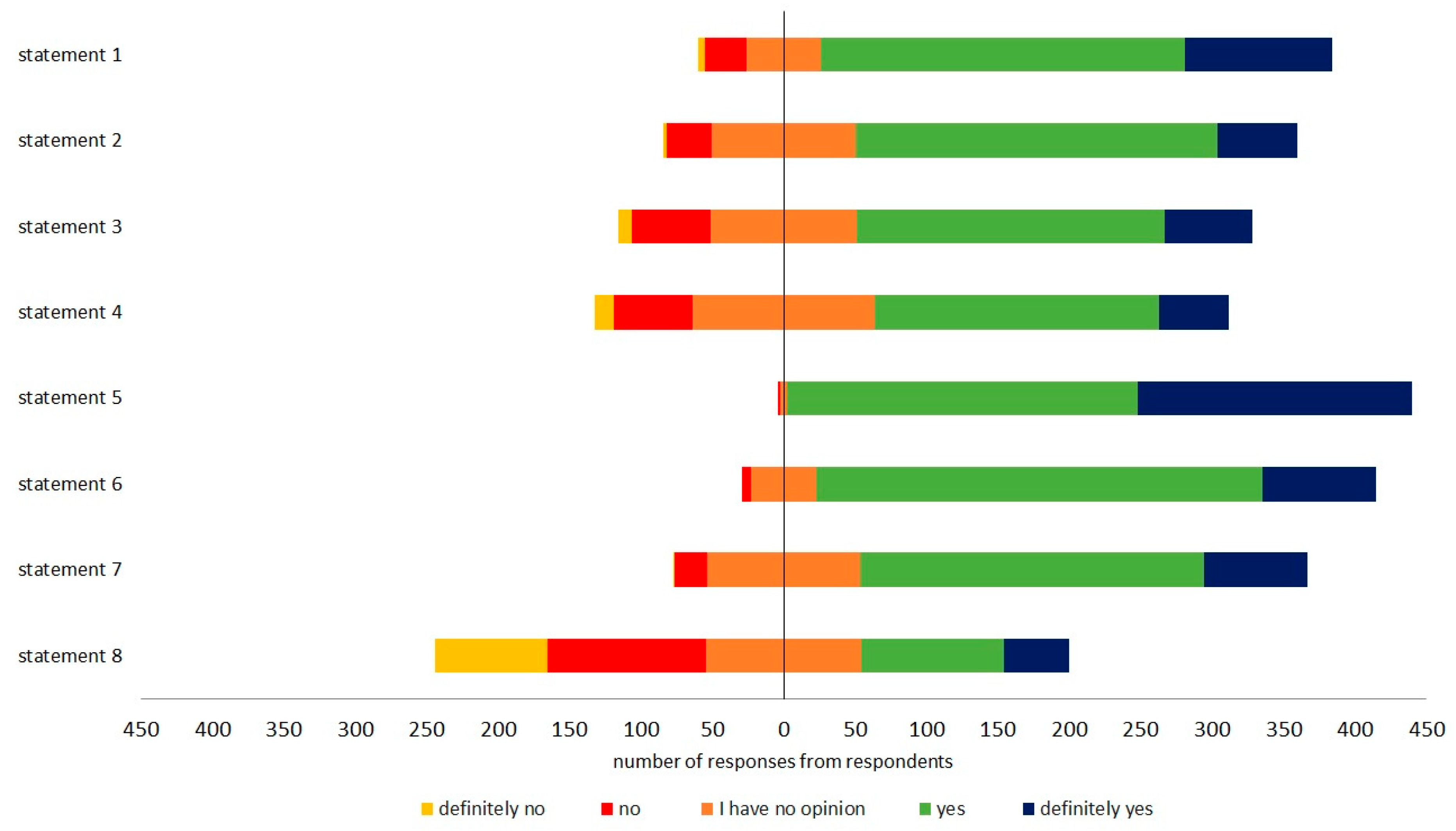

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- -

- development of a framework of best practices in OSH leadership has the potential to provide valuable material for the creation of training programmes,

- -

- organisation of management training is intended to enhance leadership skills in the domain of safety, thereby equipping management with the necessary competencies to effectively address safety-related challenges,

- -

- establishment of a forum for the exchange of knowledge and experience on safety issues and challenges among managers is a proposed initiative,

- -

- creation of an environment that is conducive to the reporting of errors and near misses by employees without the apprehension of repercussions is of paramount importance,

- -

- creation of a multifaceted approach that promotes employee engagement, communication and continuous learning is of paramount importance in order to embed a safety culture that can significantly enhance risk management capabilities while concomitantly boosting morale and productivity.

5. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X.; Ma, L.; Ruman, A.M.; Iqbal, N.; Strielkowski, W. Impact of natural resource mining on sustainable economic development: The role of education and green innovation in China. Geosci. Front. 2024, 15, 101703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Niu, J. Role of mineral-based industrialization in promoting economic growth: Implications for achieving environmental sustainability and social equity. Resour. Policy 2024, 88, 104396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, M.; Honuk, A.; Ak, H. The effect of investment incentives for mining sector on the economic growth of Turkey. Miner. Resour. Manag. 2020, 36, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, M.; Löf, O. Mining’s contribution to national economies between 1996 and 2016. Miner. Econ. 2019, 32, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherin, S.; Raza, S. Risk Analysis and Prioritization with AHP and Fuzzy TOPSIS Techniques in Surface Mines of Pakistan. J. Min. Environ. 2024, 15, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherin, S.; Raza, S.; Ahmad, I. Conceptual Framework for Hazards Management in the Surface Mining Industry—Application of Structural Equation Modeling. Safety 2023, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasarwanji, M.F.; Dempsey, P.G.; Pollard, J.; Whitson, A.; Kocher, L. A taxonomy of surface mining slip, trip, and fall hazards as a guide to research and practice. Appl. Ergon. 2021, 97, 103542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekol, A. Evaluation and Risk Analysis of Open-Pit Mining Operations. Berg. Huettenmaenn. Monatsh. 2019, 164, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasap, Y.; Subaşı, E. Risk assessment of occupational groups working in open pit mining: Analytic Hierarchy Process. J. Sustain. Min. 2017, 16, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzałkowski, P.; Woźniak, J.; Górniak-Zimroz, J.; Delijewska, B.; Bęś, P.; Solatycka, D.; Janiszewski, M. Identification and systematics of safety hazards in surface rock mining. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strzałkowski, P. Statistical Analysis of Workplace Accidents in Polish Mining Industry. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 362, 012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S. Development of uncertainty-based work injury model using Bayesian structural equation modelling. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2014, 21, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claxton, G.; Hosie, P.; Sharma, P. Toward an effective occupational health and safety culture: A multiple stakeholder perspective. J. Saf. Res. 2022, 82, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chib, S.; Kanetkar, M. Safety Culture: The Buzzword to Ensure Occupational Safety and Health. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 11, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sharma, R.; Mishra, D.K. An analysis of thematic structure of research trends in occupational health and safety concerning safety culture and environmental management. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 125346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmoro, B.J.B.; Gumasing, M.J. Antecedents of Safety and Health in the Workplace: Sustainable Approaches to Welding Operations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inness, M.; Turner, N.; Barling, J.; Stride, C.B. Transformational leadership and employee safety performance: A within-person, between-jobs design. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bęś, P.; Strzałkowski, P. Analysis of the Effectiveness of Safety Training Methods. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turskis, Z.; Dzitac, S.; Stankiuviene, A.; Šukys, R. A Fuzzy Group Decision-making Model for Determining the Most Influential Persons in the Sustainable Prevention of Accidents in the Construction SMEs. Int. J. Comput. Commun. Control 2019, 14, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.-J. The Effects of Safety Management Systems, Attitude and Commitment on Safety Behaviors and Performance. Int. J. Appl. Inf. Manag. 2021, 1, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, A.A.M.; Wahab, W.A.; Omar, R.C.; Nordin, M.Z.M.; Taha, H.; Roslan, R. Factors Influencing the Compliance of Workplace Safety Culture in the Government Linked Company (GLC). E3S Web Conf. 2021, 325, 06005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.Z.; Isha, A.S.N.; Memon, M.A.; Azeem, S.; Zahid, M. Psychosocial safety climate, safety compliance and safety participation: The mediating role of psychological distress. J. Manag. Organ. 2022, 28, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.N.; Ramli, A.; Aziz, H.A. Influencing factors on safety culture in mining industry: A systematic literature review approach. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colim, A.; Carneiro, P.; Carvalho, J.D.; Teixeira, S. Occupational Safety & Ergonomics training of Future Industrial Engineers: A Project-Based Learning Approach. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 204, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafuente, E.; Abad, J.; Vaillant, Y. Safety disconnect: Analysis of the role of labor experience and safety training on work safety perceptions. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2018, 11, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, L.A.; Bauer, G.F.; Jenny, G.J. Is the health-awareness of leaders related to the working conditions, engagement, and exhaustion in their teams? A multi-level mediation study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milczarek, M. Kultura bezpieczeństwa w przedsiębiorstwie–nowe spojrzenie na zagadnienia bezpieczeństwa. Bezpieczeństwo Pr. Nauka I Prakt. 2000, 10, 17–20. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Krok, E. Budowa kwestionariusza ankietowego a wyniki badań. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego. Stud. Inform. 2015, 37, 55–73. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, N.C.; Dykema, J. Questions for Surveys: Current Trends and Future Directions. Public Opin. Q. 2011, 75, 909–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E. Survey Questionnaire Construction. Encycl. Soc. Meas. 2005, 3, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arda, M.; Manurung, Y.H. The effect of consumer motivation on halal food purchase decisions on street traders of kesawan medan area in the pandemic period of COVID 19. Proceeding Int. Semin. Islam. Stud. 2021, 2, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sobczyk, M. Statystyka; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 1995; p. 151. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Rolke, W.; Gongora, C.G. A chi-square goodness—Of- fit test for continuous distributions against a known alternative. Comput. Stat. 2021, 36, 1885–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Poland. Employment in the National Economy in 2022; Statistics Poland: Warszawa/Bydgoszcz, Poland, 2023; p. 33.

- Baak, M.; Koopman, R.; Snoek, H.; Klous, S. A new correlation coefficient between categorial, ordinal and interval variables with Pearson characteristics. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2020, 152, 107043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zara, J.; Nordin, S.M.; Isha, A.S.N. Influence of communication determinants on safety commitment in a high-risk workplace: A systematic literature review of four communication dimensions. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1225995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flin, R.; Mearns, K.; Gordon, R.; Fleming, M. Risk perception by offshore workers on UK oil and gas platforms. Saf. Sci. 1996, 22, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, J.H.; Evans, D.D.; Jansen, K.J.; Haight, J.M. Management commitment to safety as organizational support: Relationships with non-safety outcomes in wood manufacturing employees. J. Saf. Res. 2005, 36, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajmal, M.; Isha, A.S.N.; Nordin, S.M.; Al-Mekhlafi, A.-B.A. Safety-Management Practices and the Occurrence of Occupational Accidents: Assessing the Mediating Role of Safety Compliance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, S.; Clarke, S.; O’Connor, E. Contextualizing leadership: Transformational leadership and Management-By-Exception-Active in safety-critical contexts. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 90, 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, T.L.; Chee, T.L. Healthcare workers’ safety compliance behavior in times of COVID-19: The interaction model. WORK 2023, 78, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-M.; Liao, P.-C.; Yu, G.-B. The Mediating Role of Job Competence between Safety Participation and Behavioral Compliance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, T.; Zhu, J.; Tao, Y.; Liu, Q. Perceived working conditions and employee performance in the coal mining sector of China: A job demands-resources perspective. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2024, 18, 1656–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M.A.; Swartz, S.M. Career stage and truck drivers’ regulatory attitudes. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2016, 27, 686–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Liu, Y. The Relationship Between Leadership Safety Commitment and Resilience Safety Participation Behavior. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldock, R.; James, P.; Smallbone, D.; Vickers, I. Influences on Small-Firm Compliance-Related Behaviour: The Case of Workplace Health and Safety. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2006, 24, 827–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruhen, L.S.; Griffin, M.A.; Andrei, D.M. What does safety commitment mean to leaders? A multi-method investigation. J. Saf. Res. 2019, 68, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Becker, T.E.; Vandenberghe, C. Employee Commitment and Motivation: A Conceptual Analysis and Integrative Model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 991–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levovnik, D.; Aleksić, D.; Gerbed, M. Examining the relationship between managers’ commitment to safety, leadership style, and employees’ perception of managers’ commitment. J. Saf. Res. 2025, 92, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Takda, L.; Jia, H. Influence of management practices on safety performance: The case of mining sector in China. Saf. Sci. 2020, 132, 104947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosak, J.; Coetsee, W.J.; Cullinane, S.-J. Safety climate dimensions as predictors for risk behavior. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 55, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurence, D. Safety rules and regulations on mine sites—The problem and a solution. J. Saf. Res. 2005, 36, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Jungsun, P.; Mijin, P. Creating a Culture of Prevention in Occupational Safety and Health Practice. Saf. Health Work 2016, 7, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, K. The Safety and Sustainability of Mining at Diverse Scales: Placing Health and Safety at the Core of Responsibility. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Luria, G.; Rafaeli, A. Testing safety commitment in organizations through interpretations of safety artifacts. J. Saf. Res. 2008, 39, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Fan, D.; Fu, G.; Zhu, C.J. An integrative model of organizational safety behavior. J. Saf. Res. 2013, 45, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Hua, X.; Huang, G.; Shi, X. How Does Leadership in Safety Management Affect Employees’ Safety Performance? A Case Study from Mining Enterprises in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, E.J.; Yorio, P.L. Behavioral safety compliance in an interdependent mining environment: Supervisor communication, procedural justice and the mediating role of coworker communication. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2021, 28, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthelo, L.; Mothiba, T.M.; Malema, N.R.; Mbombi, M.O.; Mphekgwana, P.M. Exploring Occupational Health and Safety Standards Compliance in the South African Mining Industry, Limpopo Province, Using Principal Component Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saat, M.Z.M.; Mashi, M.S.; Subramaniam, C.; Shamsudin, F.M. The Relationship between Management Practices and Safety Performance in Manufacturing SMEs: The Moderating Role of Proactive Personality. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2024, 14, 1585–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, A.; Borys, D. Working to rule, or working safely? Part 1: A state of the art review. Saf. Sci. 2013, 55, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twumasi, E. Work-Family Conflict and Safety Behaviour among Dual-Earner Couples; Does Family Supportive Supervisor Behavior Matter? Int. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2022, 9, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Wu, Y.; Deng, X.; Wang, X.; Yan, Y. The impact of environmental stimuli on the psychological and behavioral compliance of international construction employees. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1395400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claro, G.T.N.; Soto, J.A.B.; Ascanio, J.G.A. Impact of the occupational health and safety management system (OHSMS) on human talent management and organizational performance in the construction sector. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11, 1618356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.K.C.; Zorigt, D. Managing occupational health and safety in the mining industry. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2321–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah-Tawiah, K.; Ntow, M.A.O.; Mensah, J. Occupational Health and Safety Management and Turnover Intention in the Ghanaian Mining Sector. Saf. Health Work 2016, 7, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Parameter | Statements | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| gender | χ2 | 10.0564 | 0.6829 | 12.8313 | 7.7113 | 12.6530 | 0.2242 | 4.3971 |

| χ2-crit | 5.9915 | 5.9915 | 5.9915 | 5.9915 | 3.8415 | 3.8415 | 5.9915 | |

| sig | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | no | no | |

| position type | χ2 | 13.4871 | 2.3785 | 5.4469 | 13.2792 | 6.6455 | 12.3977 | 16.9005 |

| χ2-crit | 9.4877 | 9.4877 | 9.4877 | 9.4877 | 5.9915 | 5.9915 | 9.4877 | |

| sig | yes | no | no | yes | no | yes | yes | |

| experience length | χ2 | 9.0730 | 14.2305 | 10.4580 | 12.5678 | 2.2402 | 2.7384 | 13.5380 |

| χ2-crit | 15.5073 | 15.5073 | 15.5073 | 15.5073 | 9.4877 | 9.4877 | 15.5073 | |

| sig | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | |

| Management Staff | Others Employment | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definitely No | No | I Have No Opinion | Yes | Definitely Yes | Definitely No | No | I Have No Opinion | Yes | Definitely Yes | |

| Statement 1 | 0.00 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 65.63 | 21.88 | 1.32 | 6.58 | 12.63 | 56.05 | 23.42 |

| Statement 2 | 3.13 | 4.69 | 21.88 | 56.25 | 14.06 | 0.26 | 7.37 | 22.89 | 57.11 | 12.37 |

| Statement 3 | 0.00 | 9.38 | 17.19 | 53.13 | 20.31 | 2.63 | 12.89 | 23.95 | 47.89 | 12.63 |

| Statement 4 | 1.56 | 7.81 | 18.75 | 51.56 | 20.31 | 3.42 | 13.16 | 30.26 | 43.68 | 9.47 |

| Statement 5 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 45.31 | 54.69 | 0.00 | 0.53 | 1.05 | 57.11 | 41.32 |

| Statement 6 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.25 | 75.00 | 18.75 | 0.00 | 1.58 | 11.05 | 69.47 | 17.89 |

| Statement 7 | 0.00 | 3.13 | 9.38 | 67.19 | 20.31 | 0.26 | 5.53 | 26.58 | 52.11 | 15.53 |

| Statement 8 | 37.50 | 21.88 | 15.63 | 12.50 | 12.50 | 14.47 | 25.53 | 25.79 | 24.21 | 10.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Strzałkowski, P.; Bęś, P.; Sitarska, M.; Woźniak, J.; Pactwa, K.; Konopacka, Ż.; Niemiec, K. Management Commitment to Compliance with Occupational Safety and Health Laws and Regulations in Polish Rock Mining Companies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9168. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209168

Strzałkowski P, Bęś P, Sitarska M, Woźniak J, Pactwa K, Konopacka Ż, Niemiec K. Management Commitment to Compliance with Occupational Safety and Health Laws and Regulations in Polish Rock Mining Companies. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9168. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209168

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrzałkowski, Paweł, Paweł Bęś, Magdalena Sitarska, Justyna Woźniak, Katarzyna Pactwa, Żaklina Konopacka, and Kamila Niemiec. 2025. "Management Commitment to Compliance with Occupational Safety and Health Laws and Regulations in Polish Rock Mining Companies" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9168. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209168

APA StyleStrzałkowski, P., Bęś, P., Sitarska, M., Woźniak, J., Pactwa, K., Konopacka, Ż., & Niemiec, K. (2025). Management Commitment to Compliance with Occupational Safety and Health Laws and Regulations in Polish Rock Mining Companies. Sustainability, 17(20), 9168. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209168