1. Introduction

Traditional classroom education often confines learning to structured settings with fixed curricula, whereas outdoor education transcends these boundaries by creating dynamic, engaging, and versatile learning opportunities [

1,

2,

3]. Outdoor education—also referred to as “outdoor learning,” “environmental education,” or “nature education”—involves activities outside school buildings that achieve curriculum goals through direct, hands-on experiences [

1,

4,

5]. In this study, “outdoor education” specifically refers to formal, curriculum-aligned instruction delivered both in natural environments (e.g., school gardens, forests, beaches) and structured non-school environments (e.g., museums, science centers, botanical gardens). This dual focus underscores the pedagogical breadth of outdoor education and its potential to advance sustainability.

Outdoor education spans various subjects, including arts, science, and physical education, fostering critical thinking, risk management, and holistic development [

2,

6,

7]. Studies confirm its benefits for students’ emotional, cognitive, and physical development, including enhanced engagement, well-being, and environmental stewardship [

2,

3,

8,

9,

10]. Post-pandemic research also highlights its role in supporting mental health and re-engagement with learning [

11]. By integrating multisensory, experiential activities, outdoor education accommodates diverse learning styles and strengthens knowledge retention [

2,

12,

13].

Yet ambiguities persist in how outdoor learning is defined, as varied environments (e.g., museums, gardens, playgrounds) are grouped under a single label [

5,

12]. These inconsistencies complicate implementation and teacher understanding, emphasizing the need to examine educators’ preparedness. Effective outdoor education also requires careful planning, execution, and evaluation, supported by adequate training [

3,

8,

13,

14]. Teachers, therefore, play a central role, yet studies reveal gaps in their knowledge and preparation [

2,

15,

16]. Barriers such as financial limitations, administrative obstacles, and low motivation also restrict implementation [

3,

17,

18].

Teachers’ personal and professional experiences shape their approaches. Early exposure to nature fosters confidence, while professional training strengthens pedagogical competence [

17,

19,

20]. Outdoor education also aligns closely with sustainability by engaging students in ecological challenges and fostering resource stewardship [

9,

17]. Teachers equipped with sustainability knowledge and outdoor methods can bridge theory and practice, preparing students for sustainable living [

21,

22].

In conclusion, outdoor education offers opportunities for fostering academic, emotional, and environmental growth. Teachers’ competency is central to success and must be strengthened through systematic professional development [

2]. To avoid conceptual ambiguity, this paper distinguishes between: (a) background studies on benefits and challenges of outdoor education, (b) theoretical foundations grounded in experiential learning and sustainability frameworks, and (c) empirical research reviewed in the literature. To guide this investigation, this paper first outlines the theoretical frameworks underpinning outdoor learning, then reviews prior research and challenges, and finally presents the methodology, findings, and implications of our study.

1.1. Theoretical Foundation

The present study is grounded in established theories of experiential learning and progressive education. A central influence is John Dewey’s pragmatist philosophy and the New School movement, which emphasized learning through experience and the interaction between learners and their environments as essential to meaningful education [

23]. Dewey’s framework views education as an active, situated process rather than passive knowledge transfer, laying the groundwork for later developments in outdoor and experiential education [

24]. Building on this tradition, Kolb’s experiential learning cycle [

25] conceptualized learning as four dynamic stages: experiencing, reflecting, thinking, and acting. This cyclical model underscores the value of direct engagement, reflective observation, conceptualization, and experimentation—processes especially relevant to outdoor learning. Together, Dewey’s pragmatism and Kolb’s experiential learning theory form the theoretical foundation of this study. These frameworks establish outdoor education as a pedagogy rooted in experience, where interaction with real-world environments supports not only cognitive growth but also social, emotional, and practical competencies.

1.2. Theoretical Background

Prior research demonstrates that outdoor learning extends experiential learning into varied contexts where students develop knowledge as well as interpersonal and emotional skills through real-world engagement [

24]. Recent studies [

20,

26,

27] propose that outdoor learning should be integrated more broadly into pedagogical practices, as it supports holistic development. These recent works are built on previous research by linking outdoor learning with sustainability education, emphasizing the role of outdoor learning in fostering environmental consciousness and ecological responsibility in students [

17]. The connection between outdoor learning and sustainability has gained prominence, with scholars such as Onge & Eitel [

28] asserting that outdoor educational experiences directly contribute to students’ understanding of energy literacy and sustainable living practices. Additional evidence suggests outdoor learning fosters pro-environmental behaviors, systems thinking, and ecological responsibility [

9,

29]. This convergence of experiential learning theory with sustainability education reinforces the need for structured out-door learning programs in modern curricula.

Building on this, scholars increasingly argue that outdoor learning represents not only a pedagogical tool but also a pathway to achieving broader sustainability goals [

9,

29]. By immersing learners in natural contexts, outdoor education develops systems thinking, ecological interdependence, and responsibility for environmental stewardship [

9,

29]. These dimensions are critical for sustainability education, which aims to empower students to act as informed citizens who can address complex global challenges such as climate change and biodiversity loss. Thus, the theoretical overlap between experiential learning and sustainability provides a strong rationale for positioning outdoor education as a central component of education for sustainable development.

1.3. Sustainability, Out-of-School Learning and Teacher Education

The integration of sustainability into education has become increasingly significant as global education systems recognize the need for students to develop the knowledge, skills, and values necessary for sustainable living [

30,

31,

32,

33]. This shift underscores the role of out-of-school and experiential education as key strategies for sustainability education. Teacher education plays a critical role in equipping educators to facilitate these experiences and adopt a holistic approach to sustainability [

33,

34]. Out-of-school learning offers students opportunities to engage directly in environmental challenges, fostering an understanding of ecological systems and sustainable practices [

12,

35,

36]. By engaging with nature, students cultivate critical thinking about human–environment interactions and resource use. Schroth [

9] highlights that hands-on experiences in outdoor environments help internalize sustainability concepts and cultivate long-term environmental stewardship through direct interaction with ecosystems and communities. To implement sustainability effectively, teacher training programs must emphasize both sustainability knowledge and outdoor pedagogy. Teachers with strong sustainability knowledge and pedagogical skills are better equipped to engage students in meaningful learning experiences that promote pro-environmental behaviors [

22]. Training in outdoor education methods enhances teachers’ abilities to create dynamic learning environments that inspire sustainable thinking [

21]. Professional development programs should emphasize experiential learning, community engagement, and critical thinking, as advocated by UNESCO [

37]. The intersection of sustainability, out-of-school learning, and teacher education provides a powerful framework for fostering holistic educational practices. Teachers’ ability to integrate sustainability into curricula and leverage outdoor learning environments is crucial to addressing global challenges [

36,

38]. By engaging students in immersive, real-world learning, educators connect classroom knowledge to practical sustainability applications. In conclusion, out-of-school learning and teacher education are essential for promoting sustainability. Effective teacher training ensures educators are equipped to create transformative learning experiences that encourage sustainable practices. By fostering environmental awareness through experiential learning, we prepare students to face future sustainability challenges as informed and responsible global citizens.

1.4. Literature Review

Extensive research has been conducted on the benefits and challenges of outdoor education. Unlike the theoretical frameworks described above, this section summarizes prior empirical findings that contextualize the study. Several studies, e.g., [

39,

40,

41,

42], highlight the potential of outdoor education in fostering cognitive development and social skills among students. Yet barriers persist, including safety concerns, lack of resources, and insufficient training [

20,

27]. Recent research, e.g., [

43], has further explored the role of teacher training in overcoming these barriers, emphasizing the need for structured professional development programs that equip teachers with the skills and confidence to incorporate outdoor learning into their practice.

The link between outdoor education and sustainability has gained increasing attention in recent years. Studies [

8,

17] confirm that outdoor learning not only boosts academic achievement but also cultivates environmental awareness. This highlights its potential as a tool for sustainability. Research has also shown that outdoor learning can help bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application, offering students the chance to engage in hands-on learning experiences [

9,

17]. Teachers, therefore, play a crucial role in facilitating these experiences. Studies from recent years, e.g., [

44], indicate that teachers who have undergone specific training in outdoor education are more likely to implement these practices effectively, further underscoring the importance of targeted teacher education.

Additionally, outdoor learning contributes directly to the goals of sustainability education by enabling students to connect classroom concepts with real-world environmental issues, such as resource management, energy conservation, and biodiversity protection [

29,

41]. Such encounters encourage pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors that extend beyond the classroom. Aligning with UNESCO’s Education for Sustainable Development, these findings demonstrate the global importance of outdoor education as both pedagogy and sustainability practice.

1.5. Rationale

The growing recognition of outdoor education as a transformative pedagogical approach highlights its potential to enrich students’ learning experiences and holistic development. However, there remains a critical need to evaluate educators’ competency in organizing and facilitating outdoor learning environments, as teachers play a central role in planning, implementing, and assessing these activities. Building on the theoretical foundations of experiential learning and sustainability education, and informed by the empirical literature reviewed above, this study addresses a key gap by evaluating Turkish teachers’ competency in regulating outdoor learning across several dimensions. Educators’ proficiency directly influences the quality and effectiveness of outdoor learning, impacting student engagement, knowledge retention, and overall development. Additionally, with the increasing emphasis on sustainability education, assessing teachers’ skills in outdoor learning becomes essential to foster environmentally conscious and responsible future citizens.

This study addresses a key gap in the literature by evaluating Turkish teachers’ competency in regulating outdoor learning across several dimensions. Despite the increased interest in outdoor learning, there remains limited empirical evidence about how well-equipped teachers are to plan, implement, and evaluate outdoor instruction across different types of environments. Most existing studies focus on attitudes or perceptions, leaving a gap regarding measurable competencies. To better understand these dynamics, we focus on specific educator characteristics that are likely to shape their outdoor teaching practices, as outlined in the following research questions.

Variables such as gender, subject specialization, prior training, teaching experience, childhood environment, and teaching location were carefully selected for their potential to provide insights into educators’ practices. These variables were informed by previous research, which suggests that demographic and experiential factors shape teachers’ attitudes and practices toward outdoor learning [

17,

20]. For instance, gender was explored to assess potential disparities in teaching approaches, while subject specialization aimed to capture the influence of diverse academic disciplines on outdoor education practices. Prior training and teaching experience were included to evaluate the role of professional development in enhancing outdoor learning regulations. Childhood environment and teaching location were examined to understand how early exposure to outdoor settings and current teaching contexts (urban vs. rural) shape teachers’ approaches.

By examining these variables, this study provides a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing outdoor learning regulation. It aims not only to clarify how teachers conceptualize outdoor education in diverse settings but also to inform targeted training and policy efforts that address the specific needs of different teacher profiles. Addressing these dimensions allows for valuable insights into how educators’ backgrounds and experiences impact their ability to facilitate outdoor education. This research not only fills a gap in the literature but also highlights the importance of targeted professional development and inclusive frameworks to enhance outdoor learning practices, ultimately supporting more effective and sustainable education. Importantly, this study does not aim to establish causal relationships, but rather to examine associations and differences that may inform more tailored teacher training and policy initiatives.

Based on the aforementioned, this study aims to evaluate teachers’ competency in organizing outdoor learning, providing valuable insights into their abilities in terms of information, planning, implementation, and evaluation across different subject areas in the context of outdoor education. To achieve this goal, the study seeks to answer the following research questions:

- (1)

Does gender significantly influence Turkish teachers’ competency in organizing outdoor learning?

- (2)

Are there significant differences in the competency to organize outdoor learning among Turkish teachers from different subject areas?

- (3)

Does the mode of prior training (online vs. face-to-face) significantly affect Turkish teachers’ competency in organizing outdoor learning?

- (4)

Does teaching experience in non-school environments significantly contribute to teachers’ competency in organizing outdoor learning?

- (5)

Is there a significant association between Turkish teachers’ childhood environments and their competency in organizing outdoor learning?

- (6)

Does the geographical location where Turkish teachers have taught (e.g., rural vs. urban) significantly relate to their competency in organizing outdoor learning?

- (7)

Are there significant differences in Turkish teachers’ competency in organizing outdoor learning when examined across the study’s sub-factors?

While broad in scope, this design was chosen to capture the diverse influences shaping outdoor learning practices. The findings aim to provide broad insights that can guide more targeted future studies.

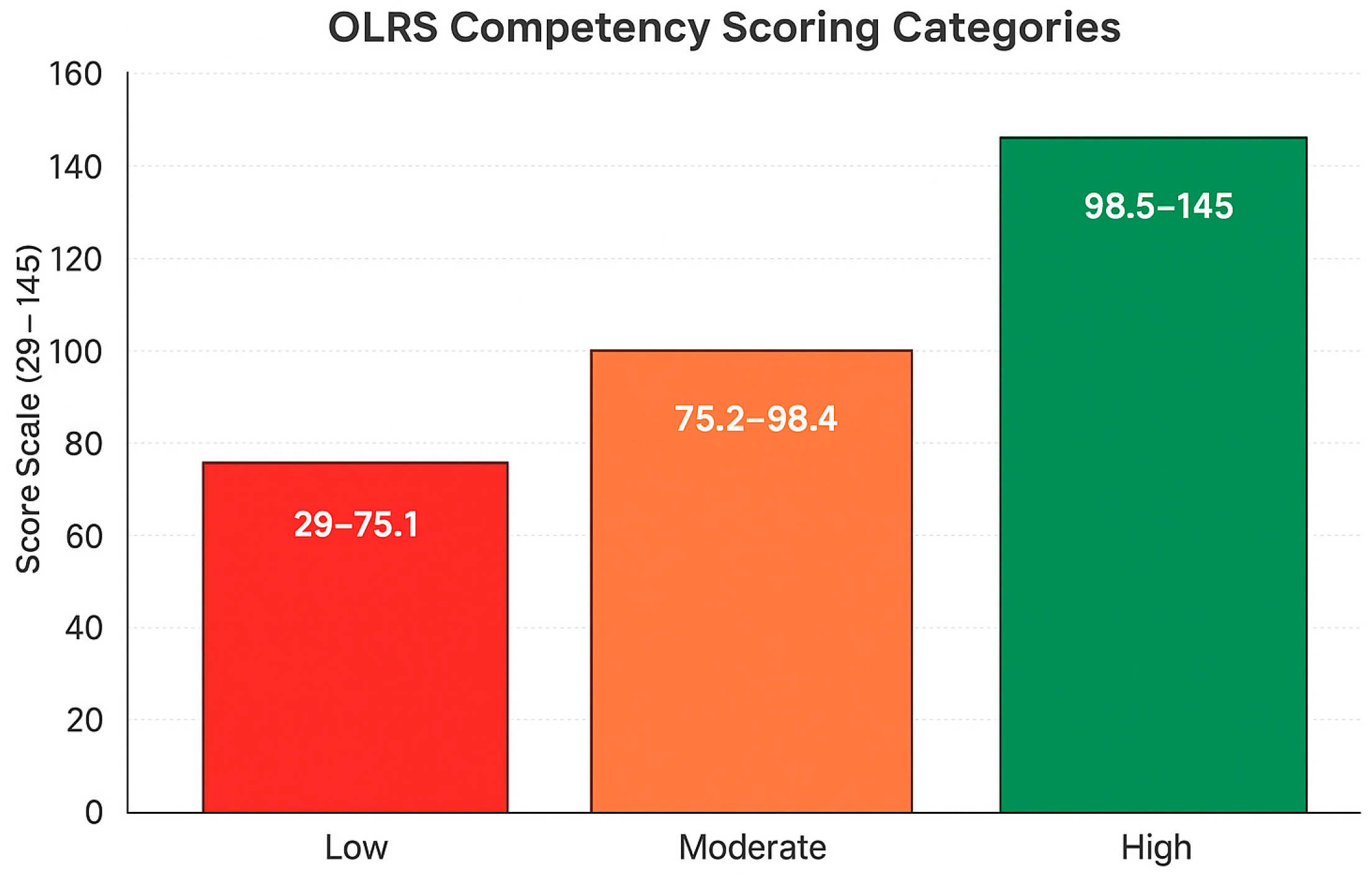

3. Results

This study provides distinct tables presenting participants’ demographic information, total scores from the scales, participant levels, and the relationships and levels of association between the variables. The tables below illustrate teachers’ competence in regulating outdoor learning based on the scale’s variables. The competency levels of the participants were assessed according to their gender and their total scores on the OLRS. The data, categorized by both factors and the overall scale, are presented in

Table 2, along with corresponding frequencies and percentages.

Table 2 indicates observable differences in the distribution of proficiency levels in outdoor learning regulation based on gender. For instance, male teachers exhibited slightly higher scores in the information factor, suggesting a stronger grasp of content knowledge related to outdoor learning. Female teachers, on the other hand, demonstrated higher levels in the planning factor, which may reflect strengths in organizing and designing outdoor learning experiences. These patterns are consistent with earlier research on teaching styles, e.g., [

56,

57]. However, despite these descriptive variations, the results of independent samples

t-tests revealed no statistically significant gender differences across OLRS dimensions (all

p > 0.65). This finding suggests that gender is not a determinant of outdoor learning regulation competence. Rather, individual experience and professional development appear to play stronger roles. Importantly, this supports equity in teacher training: both male and female educators can be equally effective when provided with appropriate support.

In summary, instead of focusing on gender as a variable of difference, these findings emphasize the importance of fostering inclusive training opportunities that develop all teachers’ capacity for outdoor learning regulation.

The participants’ proficiency levels were also assessed based on their respective academic fields.

Table 3 illustrates the distribution of participants in terms of frequencies and percentages across the various factors and the overall scale, accompanied by ANOVA test results.

Table 3 presents the percentage of teachers at low, medium, and high competency levels across branches. For readability, the data are grouped descriptively rather than reported in detail for each factor. The findings from the descriptive statistics and one-way ANOVA analysis provide a comprehensive view of how teachers’ proficiency in regulating outdoor learning varies—or does not vary—across academic fields. At a descriptive level, teachers in fields such as elementary education, social sciences, science, and guidance counseling showed somewhat higher proportions of high-level competency. These patterns suggest that the nature of the curriculum, pedagogical approaches, or prior exposure to outdoor learning principles in these disciplines may support stronger competence in outdoor learning regulation [

58,

59]. For example, science and elementary teachers may have more opportunities to use inquiry-based approaches, while guidance counselors may emphasize reflective and experiential components. However, none of these differences reached statistical significance (all

p > 0.05). This indicates that while descriptive variations exist, disciplinary specialization does not systematically influence outdoor learning regulation competence. These findings align with earlier research emphasizing that regulatory competencies often transcend subject-specific boundaries [

60,

61].

The participants’ proficiency levels were assessed by considering whether they had previously undergone online or in-person training in outdoor learning, in addition to their cumulative scores on the OLRS.

Table 4 summarizes these results, presenting overall group means, standard deviations, and independent samples

t-test findings. For ease of interpretation, the descriptive percentages are simplified into broad patterns rather than detailed factor-by-factor breakdowns.

The table demonstrates a clear and statistically significant positive effect of prior training—whether online or in-person—on teachers’ competence in regulating outdoor learning. Trained teachers not only achieved higher mean scores but also showed a substantially larger proportion in the “high” proficiency category. In contrast, untrained teachers were concentrated at the “low” level, particularly in planning and evaluation. Independent samples

t-test results confirmed that these differences were statistically significant for all OLRS factors (Information:

p = 0.000; Planning:

p = 0.000; Application:

p = 0.000; Evaluation:

p = 0.000; Total:

p = 0.000). The effect sizes, while not reported in the table, indicate meaningful practical differences between trained and untrained groups, suggesting that training is not only statistically significant but also educationally relevant. Several mechanisms may explain these outcomes. Training programs often provide comprehensive curricula that combine theoretical foundations with practical applications, enabling teachers to build both confidence and competence in outdoor education [

55,

58,

60]. Hands-on activities, exposure to best practices, and structured guidance around safety protocols, behavior management, and sustainability principles strengthen teachers’ regulatory abilities in real-world contexts. From a professional development perspective, these findings underscore the importance of integrating outdoor education training into both pre-service teacher education and ongoing in-service programs. Rather than leaving outdoor learning to individual initiative, schools and education systems should institutionalize training opportunities. This would ensure equitable access to the competencies needed for high-quality outdoor learning implementation. Future research could usefully explore which training formats, content areas, and durations have the greatest impact, thereby optimizing the design of professional development interventions in this field.

The participants’ proficiency levels were assessed based on whether they utilized outdoor learning environments in their teaching practices, as well as their cumulative scores on the OLRS. The results are presented in

Table 5, illustrating the distribution of participants in terms of frequencies and percentages across various factors and the overall scale, categorized by their use of outdoor learning environments while teaching. The findings from both the descriptive and inferential analyses consistently highlight the significant role of teachers’ experience in utilizing outdoor learning environments in shaping their proficiency levels in regulating outdoor learning. Educators who had outdoor teaching experience consistently achieved higher mean scores and a markedly larger proportion at the high proficiency level across all OLRS dimensions. In contrast, teachers without outdoor teaching experience were disproportionately concentrated in the low-proficiency group. The independent samples

t-test confirmed that these differences were statistically significant for all factors (Information:

p = 0.000; Planning:

p = 0.000; Application:

p = 0.000; Evaluation:

p = 0.001; Total:

p = 0.000).

This demonstrates not only a statistical but also a practical impact, suggesting that hands-on experience with outdoor environments substantially enhances regulatory competencies. Teachers who actively use outdoor settings appear better equipped to acquire and process information related to outdoor pedagogy, plan effective activities, implement outdoor learning principles, and evaluate outcomes [

34,

55].

In particular, their higher scores in information and planning may reflect the contextualized, interdisciplinary, and experiential opportunities provided by outdoor settings, while stronger application and evaluation outcomes suggest that outdoor practice fosters authentic inquiry, reflection, and critical thinking. From a theoretical perspective, the significant differences further highlight the importance of considering experiential dimensions in models of outdoor education pedagogy. Teaching in outdoor environments exposes educators to dynamic, real-world conditions that build adaptability, resilience, and creativity, while simultaneously deepening their understanding of place-based and experiential frameworks. These results carry important implications for teacher education and professional development. Programs should intentionally integrate structured opportunities for outdoor teaching into preservice and in-service training, ensuring that educators can gain both competence and confidence. Beyond pedagogical strategies, training must also emphasize safety, behavior management, and sustainability practices, empowering teachers to create safe, engaging, and environmentally responsible outdoor learning experiences [

34,

55].

The participants’ proficiency levels were assessed based on the locations where they spent their childhoods, alongside their cumulative scores on the OLRS.

Table 6 presents both the distribution of participants in terms of frequencies and percentages across the factors and overall scale and the outcomes of the independent samples

t-test. The descriptive results (

Table 6) reveal certain patterns suggesting potential influences of childhood environments on teachers’ regulatory skills. Teachers who grew up in villages appeared slightly stronger in the information, planning, and evaluation factors, while those raised in cities showed marginally higher results in application and total scores. These tendencies could reflect how rural upbringings may cultivate organizational and evaluative skills through early contact with natural settings, whereas urban contexts may foster adaptability, problem-solving, and access to diverse institutional resources. However, the inferential results from the independent samples

t-test demonstrated that these differences were not statistically significant (all

p > 0.05). This means that while descriptive contrasts exist, they are not strong enough to conclude that village or city childhood backgrounds systematically shape teachers’ regulatory competence in outdoor learning. One possible explanation is that later professional development, training opportunities, and teaching experiences provide teachers with the skills and strategies necessary for regulating outdoor learning, regardless of their childhood environment [

58,

60]. In modern contexts, the expansion of urban access to outdoor recreation and environmental education initiatives may further reduce differences between rural and urban upbringings.

Overall, while descriptive results hint at nuanced influences of early environmental exposure, the statistical findings underscore that professional training, institutional support, and personal motivation are more decisive in shaping teachers’ outdoor learning regulation. This highlights the importance of investing in teacher education programs and ongoing professional development to ensure that educators from diverse backgrounds are equally prepared to deliver meaningful and effective outdoor learning experiences.

The participants’ proficiency levels were assessed based on the locations where they conducted their teaching, alongside their cumulative scores on the OLRS.

Table 7 illustrated the distribution of participants across frequencies and percentages for each factor and the overall scale, categorized by teaching locations. The descriptive results indicated that teachers working in villages showed slightly higher scores in information, whereas city-based teachers reported marginally higher results in planning, application, evaluation, and total regulation. These differences suggest that rural environments may offer advantages through access to natural landscapes and community-based resources, whereas urban contexts provide diverse institutional and cultural opportunities that support planning and implementation [

62]. Despite these patterns, the inferential results of the independent samples

t-test revealed no statistically significant differences between rural and urban teachers across any OLRS factor (all

p > 0.05). This indicates that teaching location alone is not a decisive determinant of outdoor learning regulation. Instead, professional training, institutional support, and pedagogical approaches appear to play more influential roles than geography. The non-significant findings also suggest that both rural and urban teachers adapt effectively to their respective contexts. Rural teachers may rely on natural settings and local networks, while urban teachers draw upon partnerships and adapt outdoor pedagogy to city environments. In both cases, teacher agency, creativity, and professional expertise remain central.

Overall, these results highlight that effective regulation of outdoor learning is less about geographic setting and more about teachers’ competencies, experiences, and support systems. This reinforces the importance of professional development programs that both address contextual opportunities and strengthen universal pedagogical skills required for outdoor education. Such initiatives should be designed to help teachers leverage local strengths—whether natural or institutional—while also building core competencies that transcend geographic boundaries [

62].

4. Discussion

The findings from this study provide valuable insights into how different factors influence teachers’ regulation of outdoor learning. By analyzing various demographic and experiential variables, several key patterns emerged that contribute to a deeper understanding of how educators engage with and facilitate outdoor learning. Importantly, these interpretations are supported by the strong psychometric properties of the Outdoor Learning Regulation Scale (OLRS). The factor analysis confirmed a valid four-factor structure—information, planning, application, and evaluation—with high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.99), indicating that the findings reported across these dimensions reflect reliable and theoretically meaningful distinctions in teachers’ competencies.

Gender differences in outdoor learning regulation: The results revealed some observable descriptive differences in the proficiency levels of male and female teachers across the factors of outdoor learning regulation. Specifically, male teachers tended to show slightly higher scores in the information, application, and evaluation factors, while female teachers scored higher in the planning factor. However, the independent samples

t-test results indicated that none of these gender differences were statistically significant (all

p > 0.05). Given the validated multidimensional structure of the OLRS, these non-significant differences suggest that gender does not systematically influence any of the four core competency domains—information, planning, application, or evaluation. This suggests that gender is not a significant determinant of teachers’ regulation of outdoor learning. The findings support the perspective that teachers’ effectiveness in outdoor education is shaped more by professional training, experience, and access to resources than by gender-based factors. This aligns with previous research that highlights the importance of avoiding essentialist assumptions about gender and pedagogy [

63,

64]. While the binary gender classification used here follows conventional demographic reporting, future studies should seek to include a more inclusive understanding of gender to capture diverse teacher identities.

Variations across academic fields: Descriptive analyses suggested that teachers in elementary education, science, social studies, and psychological counseling and guidance tended to report higher proficiency levels in certain OLRS factors. These findings are in line with research showing that such fields often incorporate experiential, interdisciplinary, or inquiry-based learning that is conducive to outdoor teaching [

54,

55,

58]. Yet, the ANOVA results indicated that none of these branch-based differences reached statistical significance (all

p > 0.05). The validated four-factor model lends further confidence to this interpretation, showing that while descriptive trends exist, core regulatory competencies—across information, planning, application, and evaluation—are consistently distributed among disciplines. This finding tempers the interpretation of descriptive variations and emphasizes that academic discipline alone does not systematically predict teachers’ competence in outdoor learning regulation. It further suggests that core competencies in outdoor pedagogy (e.g., structured planning, safe implementation, reflective evaluation) transcend subject boundaries [

60,

61].

Impact of prior training in outdoor education: A significant outcome from the analysis was that teachers who had received online or face-to-face training in outdoor education exhibited notably higher scores across all factors. Teachers who had received online or face-to-face training in outdoor education scored significantly higher across all OLRS factors (all

p = 0.000). This result underscores the transformative role of professional development in shaping teachers’ knowledge, confidence, and pedagogical skills for outdoor education. Given the strong factor loading across all four subdimensions confirmed by the factor analysis, these training effects can be confidently interpreted as improvements in comprehensive regulation competencies—not limited to a single skill, but spanning knowledge acquisition (information), instructional design (planning), practical delivery (application), and reflective evaluation. Training provides structured exposure to theoretical and practical strategies, equipping teachers to effectively design and regulate outdoor learning activities [

55,

60]. Based on these findings, teacher training programs should prioritize (a) integrating hands-on outdoor teaching practice alongside theoretical coursework, (b) including modules on safety management, risk assessment, and behavioral strategies specific to outdoor environments, and (c) embedding sustainability-focused content to link outdoor pedagogy with broader ecological literacy goals. Furthermore, training should expose teachers to a variety of settings (urban, rural, formal, and informal) so they can adapt flexibly across contexts.

Role of teaching experience in outdoor settings: The data revealed that teachers with experience teaching in outdoor settings scored higher across all aspects of outdoor learning regulation. This finding highlights the importance of practical, hands-on teaching experiences, which allow educators to effectively utilize outdoor environments to enrich student learning [

34,

54,

55]. The validated four-factor structure reinforces that such experience enhances multiple interconnected competencies—teachers not only gain factual knowledge and planning ability but also develop the applied and evaluative skills necessary to manage dynamic outdoor learning contexts. Relevant papers, e.g., [

54], support this by demonstrating how teachers who regularly engaged in outdoor teaching developed a deeper understanding of its educational potential, including increased student motivation, enhanced communication, and stronger participation. Moreover, direct exposure to outdoor teaching fosters key teaching skills such as creativity and adaptability [

34,

55]. Fägerstam [

54] found that teachers learned to navigate the complexities of outdoor settings, which required them to think on their feet and adjust their teaching methods to dynamic environments. These experiences also helped educators gain a deeper appreciation for the diverse learning opportunities that outdoor education offers, which complement traditional indoor learning by making it more experiential and multisensory. Given these benefits, it is evident that teacher preparation programs should incorporate experiential learning opportunities in outdoor settings. The factor analysis evidence provides confidence that improvements in one domain (e.g., application) are likely to be accompanied by growth in complementary domains (e.g., evaluation), underscoring the value of holistic, field-based practice. The research [

54] shows that teachers who practice outdoor teaching not only become more confident in their abilities but also foster better learning outcomes for their students. This suggests that embedding outdoor teaching experiences in teacher education programs is crucial for building the skills necessary to manage and optimize diverse learning environments. Teacher preparation programs should therefore embed structured field-based practicums in natural and built outdoor environments, giving educators the opportunity to plan, deliver, and reflect on real outdoor lessons before entering the profession.

Influence of childhood environment on outdoor learning regulation: Descriptive patterns suggested that teachers from rural backgrounds performed slightly better in information, planning, and evaluation, whereas those from urban backgrounds scored somewhat higher in application. However, independent

t-tests showed no statistically significant differences between village- and city-raised teachers (all

p > 0.05). These non-significant results across the validated factors further suggest that early environmental context may shape attitudes rather than measurable competencies across the four domains. This supports the view that later professional training and teaching practice are more influential [

65,

66]. While early childhood experiences may influence initial attitudes toward outdoor environments, professional training, and experiences play a more substantial role in shaping teachers’ proficiency in regulating outdoor learning. The literature supports this perspective, emphasizing that exposure to natural outdoor settings during childhood can foster an appreciation for nature, but this does not always translate into the skills required for effective teaching in outdoor environments. For instance, Wells & Lekies [

66] noted that childhood experiences with nature are linked to positive environmental attitudes in adulthood, but professional development and structured learning experiences are crucial for developing specific teaching competencies. Furthermore, studies have highlighted that educators who undergo formal training in utilizing outdoor learning environments are better equipped to integrate these spaces into their curricula effectively [

65,

67]. Therefore, this study emphasizes the importance of ongoing professional development in overcoming initial disparities, suggesting that opportunities for growth in outdoor learning regulation are not constrained by one’s early environmental exposure but rather enhanced through targeted training and experience.

Relevance of teaching location to outdoor learning practices: A similar pattern emerged when comparing teachers currently working in rural versus urban environments. Descriptive results suggested some contextual strengths (e.g., higher information scores for rural teachers, higher planning/application/evaluation for urban teachers), but these differences were not statistically significant (all

p > 0.05). The factor analysis confirms that the OLRS captures consistent competencies across contexts, supporting the interpretation that adaptability—rather than location—is key to effective outdoor learning regulation. This supports the notion of adaptability in outdoor pedagogy. The relevant paper [

54] reinforces this finding, illustrating that teachers in both urban and rural areas can equally leverage their local environments to create meaningful outdoor learning experiences. Whether utilizing parks, gardens, or urban spaces in cities or forests and rivers in rural areas, teachers demonstrated similar competencies in engaging students with nature and facilitating outdoor learning. This reflects the flexibility of outdoor teaching strategies, which can be adapted to various environmental settings to meet educational goals. Moreover, Neville et al. [

68] point out that the capacity to implement effective outdoor learning depends not only on the environment but also on teachers’ ability to creatively integrate these settings with curriculum objectives. Teachers across diverse settings can maximize the learning potential of their local environments by identifying suitable outdoor spaces that align with learning outcomes, whether urban or rural [

68]. The findings suggest that the adaptability of teachers in outdoor learning is a significant asset, allowing them to use the resources available in their specific contexts effectively. Future research could further explore how teachers tailor their strategies to different settings, deepening our understanding of the nuances involved in outdoor learning across various geographic contexts [

21].

Professional development and policy implications: Overall, the findings emphasize that while descriptive patterns exist across gender, academic field, and environmental background, the only consistently significant predictors of higher outdoor learning regulation were prior training and actual teaching experience in outdoor environments. Given the validated multidimensional structure of the OLRS, these predictors can be interpreted as influencing a comprehensive set of regulatory competencies rather than isolated skills. This has clear implications for educational policy and teacher education. Investments should be directed toward providing comprehensive training opportunities and structured outdoor teaching experiences, both in pre-service and in-service contexts. Such efforts will better prepare teachers to integrate outdoor pedagogy effectively across diverse subjects and settings [

38]. In practice, this means policy frameworks should mandate regular in-service training workshops, encourage school–community partnerships to expand outdoor opportunities, and support interdisciplinary collaboration so that outdoor pedagogy becomes embedded across the curriculum rather than treated as an optional add-on.

This study contributes to the growing body of literature on outdoor learning by clarifying that demographic and contextual factors alone do not strongly determine teachers’ competence. Instead, professional development and experiential practice are the decisive levers for strengthening outdoor learning regulation. The validated four-factor model provides a robust framework for designing such professional development, ensuring that all dimensions—knowledge, planning, implementation, and evaluation—are systematically addressed. As outdoor education becomes increasingly central to sustainability education, focusing on these levers will be essential to equipping teachers with the skills and confidence to promote meaningful, hands-on learning beyond the classroom. Future research should build on these findings by conducting longitudinal studies to track how teachers’ competencies evolve over time with continued training and practice. Comparative research across regions and educational systems could also illuminate how institutional support and policy frameworks shape outcomes. Finally, mixed-methods studies combining quantitative and qualitative approaches may provide deeper insights into how teachers translate outdoor training into day-to-day classroom practice.

5. Conclusions and Implications

This study offered a comprehensive examination of teachers’ regulation of outdoor learning and the factors influencing their competencies. By analyzing variables such as gender, academic specialization, prior training, teaching experience, childhood background, and teaching location, the research provides nuanced insights into how educators engage with and facilitate outdoor education. Importantly, the robustness of the study’s findings is strengthened by the results of the factor analysis. The Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) confirmed a clear and coherent four-factor structure—information, planning, application, and evaluation—with strong loadings (all > 0.60) and high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.99), indicating that the Outdoor Learning Regulation Scale (OLRS) reliably captures the multidimensional nature of teachers’ competencies. The four extracted factors explained 57.8% of the total variance, providing empirical support for the distinct yet interrelated domains of outdoor learning regulation. This statistical evidence reinforces confidence in the interpretation of group differences and predictor relationships reported in this study.

The findings revealed that while early environmental background and current teaching location did not significantly impact regulation levels, prior training in outdoor education and hands-on teaching experience in outdoor settings were strong predictors of teacher competency. This underscores the value of practical, context-rich experiences in shaping teachers’ confidence and proficiency in managing outdoor learning. Gender differences also emerged, with male teachers demonstrating greater strengths in application and evaluation, while female teachers excelled in planning. Teachers from disciplines such as elementary education, science, and social studies showed higher proficiency, likely due to the experiential nature of these fields. The validated four-factor structure provides deeper insight into how these competencies manifest across teachers. For instance, teachers with prior outdoor experience scored consistently higher across all four factors, suggesting that experiential engagement supports not only the practical (application) and reflective (evaluation) aspects of regulation but also enhances knowledge (information) and instructional design (planning) capabilities. This multidimensional view underscores the interdependence of cognitive, procedural, and evaluative competencies in effective outdoor education. These results underscore the importance of tailored, field-specific, and gender-sensitive professional development to build capacity across diverse educator profiles. Crucially, this study centers on the regulation competencies of teachers rather than student outcomes. While enhanced student learning is a long-term goal, our findings emphasize the need to first equip educators with the skills to plan, implement, and evaluate effective outdoor experiences. Additionally, this research provides context-specific insight into Türkiye’s educational landscape, where bureaucratic challenges—such as permission procedures, limited infrastructure, and curricular constraints—may hinder teachers’ ability to incorporate outdoor learning. Recognizing these systemic barriers is vital for shaping actionable policy reforms [

34,

55]. Addressing these institutional and policy-level barriers could create a more enabling environment for outdoor pedagogy. In line with the existing literature, this study reaffirms that well-planned outdoor learning activities enhance students’ cognitive, emotional, social, and physical development. Outdoor education fosters interdisciplinary learning, improves engagement and retention, promotes environmental awareness, and supports inclusive pedagogies [

1,

5,

49]. However, these benefits can only be realized when teachers possess the necessary regulation competencies to manage these learning environments effectively. Thus, strengthening teachers’ capacity to integrate outdoor learning into formal curricula is vital for promoting both academic success and sustainability-oriented mindsets among students. By confirming the psychometric soundness of the OLRS through factor analysis, this study provides a reliable framework for future research and practice. Policymakers and teacher educators can utilize the validated four-factor model to design professional learning programs that target each dimension—enhancing knowledge acquisition, planning efficiency, instructional execution, and reflective evaluation.

The implications of these findings are twofold. First, educational policymakers and institutions should prioritize the integration of outdoor education into teacher training curricula, with an emphasis on experiential, sustainability-focused approaches. Second, professional development programs must go beyond theoretical frameworks and include practice-based, reflective, and collaborative components that enhance teachers’ confidence and adaptability in diverse educational settings. Such programs could include mentoring, peer observation, and field-based practicums to bridge the gap between theory and practice. Despite its contributions, the study has limitations. The sample consisted primarily of Turkish teachers, which may limit generalizability. Additionally, the use of self-reported data introduces the potential for response bias. Nevertheless, the confirmed factor structure and high reliability indices strengthen the credibility and transferability of the findings. Future research should include cross-cultural comparisons, employ more representative sampling techniques, and consider longitudinal or regression-based approaches to examine how various factors predict teachers’ outdoor learning competencies over time. Investigating the long-term impact of teacher competencies on student outcomes could also offer valuable insights. By aligning its focus with the global shift toward sustainability education, this study contributes to the international discourse on teacher preparedness for outdoor learning. Future studies could examine how geographic, cultural, and policy differences affect teachers’ capacity to adopt outdoor pedagogy, thereby enriching comparative education frameworks.

Ultimately, this study contributes to the growing body of literature on outdoor education and sustainability by highlighting the importance of equipping teachers with the tools necessary to transform learning beyond the classroom. The validated four-factor model underscores the need for comprehensive professional preparation that addresses all aspects of regulation—knowledge, planning, implementation, and evaluation—to foster inclusive, engaging, and environmentally responsible learning environments.