1. Introduction

Promoting economic growth and common prosperity are the main focus of the country’s economic policy [

1]. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) Annual Report 2024 notes a marked slowdown in worldwide economic expansion, anticipating a prolonged phase of moderate growth. Multiple developing countries and emerging economies grapple with the combined pressures of slowing growth and persistent distributive inequities [

2]. China similarly confronts issues of suboptimal economic development quality and income inequality [

3]. As evidenced by official data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the urban–rural income ratio stood at 2.34 in 2024, while the Gini coefficient has exceeded 0.46 for four consecutive years, highlighting the urgency of transitioning from “getting rich first” to “common prosperity”. Research demonstrates that unequal income distribution and significant urban–rural disparities negatively impact citizens’ overall well-being, whereas high-quality public services prompt industry development and ensure equal opportunities [

4,

5]. In response, China has rolled out a set of policy initiatives to tackle inefficient economic growth and uneven wealth distribution, including the Plan to Promote Common Prosperity through Digital Economy and the Resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Further Deepening Reform Comprehensively to Advance Chinese Modernization.

Achieving common prosperity necessitates the provision of high-quality public services, the generation of sufficient employment opportunities, and the establishment of equitable mechanisms for wealth distribution [

6]. However, conventional governance patterns often suffer from postponement of information and execution inefficiencies, limiting their capacity to meet public expectations. Therefore, leveraging digital government construction (DG) to foster common prosperity has become an international consensus.

Amid the global wave of DG, the governments of developed countries are accelerating the improvement of government service quality by widely leveraging digital technologies in management [

7]. The e-Government Benchmark Report 2024 indicates that 37 European nations are providing and promoting digital government services. By employing strategies such as “Upstream Social Marketing”, governments can more effectively deploy mobile governance services and strengthen public involvement and policy responsiveness [

8]. Moreover, comparative analysis of local governance models in Slovakia and Lithuania demonstrates that civic participation substantially shapes the implementation effect of digital democracy [

9]. As one of the earliest developing countries to incorporate DG as a national strategy, China has also made remarkable advances in policy design. In 2022, the Guidelines for Strengthening the Construction of Digital Government designated that DG is a central instrument for enhancing public service capacity and the efficiency of public administration. Driven by this policy, China’s digital infrastructure and the state of DG digital infrastructure and digital governance in China have consistently improved. China attains the highest standing among developing nations in the United Nations E-Government Survey 2024, with its E-Government Development Index standing at 0.8718. The ongoing process of DG accelerates public sector modernization while creating novel pathways to advance common prosperity.

What effects does DG have on common prosperity? Existing academic studies converge on the economic benefits of DG for common prosperity. Literature on digital governance theory demonstrates that adopting diverse digital technologies effectively curbs corruption and improves governance performance [

10]. In particular, the pervasive adoption of AI, big data, and similar digital solutions fosters a more accuracy implementation of common prosperity policies by advancing the digitization and intellectualization of the policy process [

11]. The platformization of government services functions to overcome geographical barriers in resource allocation, which significantly extends the reach and improves the accessibility of rural public services [

12]. This allows traditionally underserved populations to benefit more equitably from public goods and ensures that the economic fruits are distributed more broadly across society. However, the economic effects of DG remain uncertain. For instance, the digital divide has resulted in unequal distribution of benefits for different groups during the early phases of DG. The dividends of digital development have less reached farmers in regions with pronounced income inequality, while significantly narrowing the wealth gap among citizens in highly economically developed areas [

13]. This divergence is especially evident across regions with different levels of human capital. Lower-skilled individuals must upgrade their competencies to fully benefit from DG [

14]. In the domain of employment and income, while digital technologies drive growth in the Internet economy, they may also disrupt the real economy in the short term, producing dual effects of destruction and creation to employment [

15]. Against this backdrop, a thorough examination of the impact mechanisms linking DG to common prosperity is critical.

While a body of prior research has yielded certain progress in DG and common prosperity, several limitations remain. First, the theoretical framework for how DG specifically influences common prosperity is not yet fully articulated. Most current studies treat these two domains separately rather than exploring their interconnections. Given that common prosperity represents a vital pathway toward enhancing citizen welfare, further investigation is urgently needed to clarify how DG serves as a key governance means in advancing this goal. Second, developing countries frequently face a shortage of sufficient motivation and resources to implement measures to prompt DG, which leads to existing research mostly focusing on developed countries while paying less attention to developing countries and emerging economies. These regions confront distinct challenges in pursuing DG and common prosperity, and must reconcile the need between the imperative of rapid economic growth and equitable wealth sharing.

The governance innovations driven by DG are transforming the mode and effectiveness of public service supply, thereby strengthening equitable resource allocation and enhancing citizen well-being. This study makes three primary contributions. First, this study focuses on developing countries with relatively large wealth disparities. Due to their relatively lower economic development and uneven resource distribution, these countries exhibit evident income inequality. Within this context, this study examines whether DG facilitates the attainment of common prosperity, thereby extending the relevant theories and existing literature on the subject. Second, this study establishes a multidimensional assessment index system applicable to common prosperity. Employing a panel data model, this study delineates the specific transmission channels governing the U-shaped relationship between DG and common prosperity. Third, this study further reveals the heterogeneous influence of core DG dimensions on common prosperity, while also examining spatial effects and regional heterogeneity. In addition, this study equips policymakers with targeted recommendations, delivering theoretical foundations and actionable guidance to steer DG and foster common prosperity.

The following outline summarizes the organization of the rest of this article.

Section 2 reviews the pertinent literature on DG and common prosperity, and derives hypotheses.

Section 3 describes the research methodology.

Section 4 reports empirical analysis results.

Section 5 provides the discussion. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the main findings, policy implications, and study limitations.

5. Discussion

Against the backdrop of digital transformation, enhancing common prosperity has become a critical societal issue attracting widespread attention from scholars and governments globally. However, limited understanding exists regarding the impact and mechanisms of DG on common prosperity. This study addresses this under-explored area by examining how DG fosters both economic growth and distributional equity. It further elucidates pathways through which less developed regions and vulnerable groups can overcome developmental disadvantages and achieve more inclusive benefits from digitalization. Current measurement frameworks for common prosperity continue to evolve. This research innovatively develops a comprehensive evaluation system integrating sharing value and prosperity value, enabling multidimensional and precise assessment. EWM-based indices reveal considerable disparities in common prosperity across Chinese provinces from 2018 to 2023. The overall low average index indicates an urgent need for more balanced regional development. These findings align with recent studies [

65]. Regions endowed with abundant resources and sound economic foundations typically provide stronger institutional support and sufficient resources for advancing common prosperity. These advantaged areas not only better meet basic public service demands but also supply higher-quality development opportunities. In contrast, less developed regions face multiple constraints—including weak infrastructure, limited fiscal capacity, scarce human capital, and ineffective policy implementation-which further exacerbate interregional disparities in common prosperity.

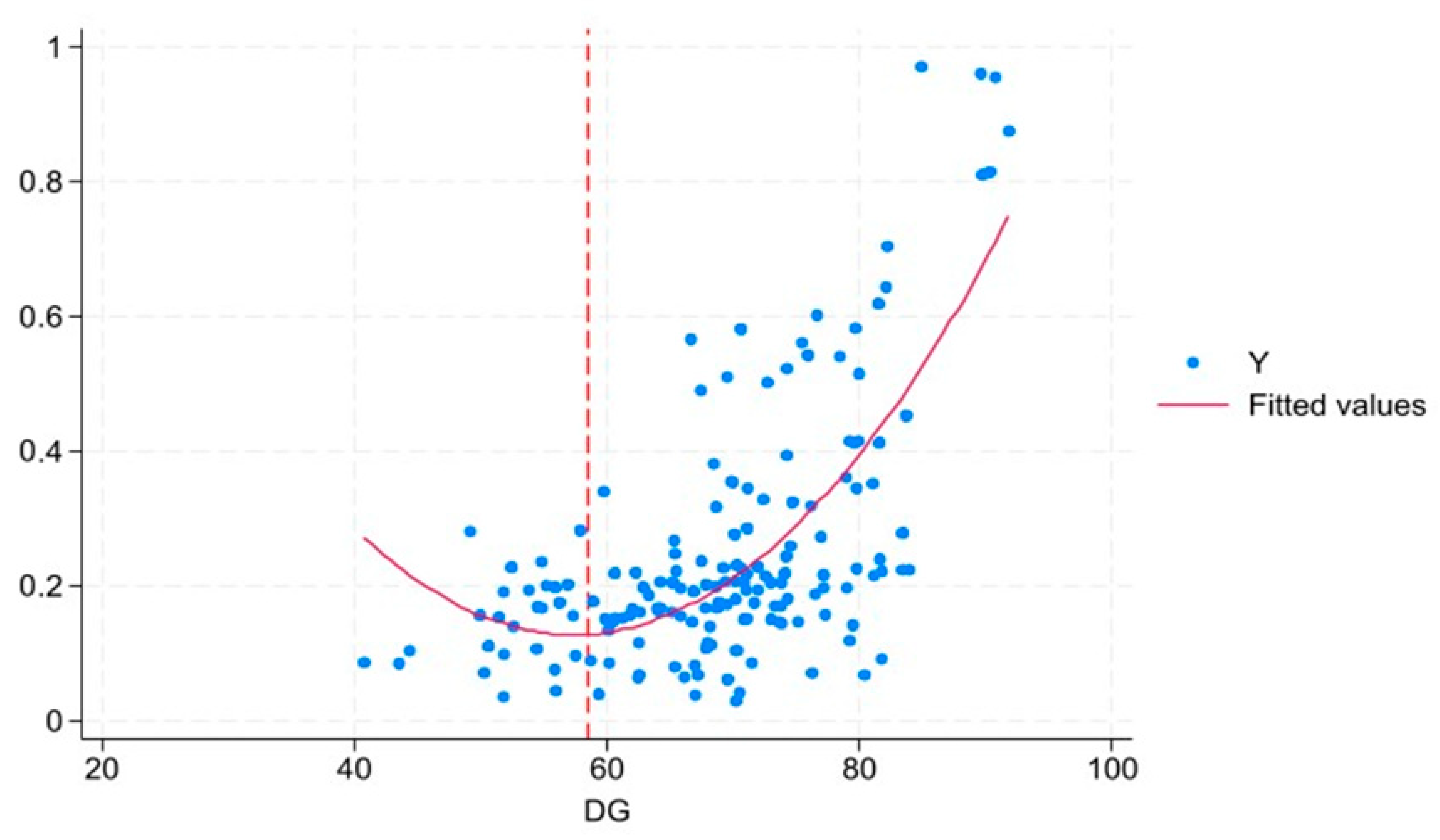

While studies on common prosperity in developed countries offer valuable insights, developing countries commonly face acute resource allocation imbalances and heightened vulnerability to digital divide escalation. These contexts underscore the particular importance of DG in unlocking developmental benefits. Empirical findings reveal a U-shaped relationship where DG initially suppresses but subsequently accelerates common prosperity. This result replenishes the conventional assumption of a purely linear association prevalent in existing literature [

66].

Common prosperity is also constrained by underdeveloped digital finance and insufficient human capital. Promoting digital inclusive finance and strengthening education expenditure represent two key channels through which DG advances common prosperity. By leveraging the internet and digital technologies, DG facilitates information exchange between government agencies and financial institutions. This enhances the precision of credit allocation and contributes to equalizing economic opportunities [

67]. Meanwhile, increased investment in education helps improve digital literacy and technical skills among the population, strengthening productive capabilities and technological adoption. These improvements raise labor productivity and stimulate innovation, thereby mitigating income inequality [

68]. Although DG may require citizens to invest more time in acquiring digital skills during the process of public service optimization and resource allocation, the resulting accumulation of digital literacy ultimately generates substantial economic and social returns. These gains support the broader goal of common prosperity.

Furthermore, the multidimensional nature of DG offers a robust foundation for examining its differential effects on common prosperity. In terms of individual dimensions, both service supply capacity and service intelligence capacity show significant U-shaped relationships with common prosperity, whereas service responsiveness shows only a weak influence. These findings suggest that DG generates heterogeneous effects across distinct functional domains, thereby extending and enriching existing literature [

38].

6. Conclusions, Implications and Limitations

6.1. Main Findings

DG represents a vital indicator of modernization in public governance, reflecting the expansion and integration of information technology across all stages and domains of government operations. Based on provincial-level panel data from China (2018–2023), this study systematically examines the impact of DG on common prosperity. Adopting multiple empirical approaches, it identifies and verifies the transmission channels through which DG influences common prosperity. These findings help to a deeper understanding of the conceptual and practical dimensions of digital government and enrich theoretical discourse on its effects within public governance. The study yields three main findings:

First, this study reveals that the relationship between DG and common prosperity is not simply linear, but rather follows a nonlinear U-shaped pattern characterized by initial suppression followed by promotion. This finding underscores the long-term and conditional nature of DG effectiveness. Further analysis confirms the robustness of this relationship, though the effect does not yet exhibit cross-regional spillovers. The above findings provide strong evidence that DG contributes to common prosperity through multiple pathways, thereby enriching theories and existing literature on the economic effects of DG. Solomon & van Klyton found that the coefficient of the impact of enterprises and governments’ use of ICT on economic growth in African countries is sometimes not significant, and our study supplements this finding [

69].

Second, mechanism analyses indicate that DG exerts a U-shaped impact on common prosperity through two core channels: enhancing digital inclusive finance and increasing education expenditure. Digital inclusive finance expands service availability while lowering transaction expenses, effectively supporting income growth among vulnerable groups. Increased education expenditure strengthens human capital accumulation, laying a foundation for social mobility and long-term equitable development.

Third, further analysis indicates that two sub-dimensions of DG exert a significant U-shaped influence on common prosperity, whereas the service responsiveness dimension shows no statistically significant effect. This conclusion is consistently supported by U-test results. Moreover, the impact of DG exhibits notable regional heterogeneity. A significant U-shaped relationship is observed in the more economically developed eastern regions, while this association is not statistically significant in western regions. These findings underscore the dependence of DG on initial regional digital resource conditions and provide an empirical basis for formulating differentiated regional policies.

6.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study not only identifies the complex effects of DG on common prosperity but also clarifies its underlying mechanisms and contextual boundaries. Based on empirical findings, this study proposes targeted policy implications. That offer theoretical support and empirical insights to assist governments in formulating precise and efficient DG strategies aimed at promoting common prosperity and sustainable social development.

First, implement differentiated regional strategies for DG and improve digital infrastructure. During the initial phase, efforts should prioritize addressing infrastructure gaps in underdeveloped regions to reduce access and usage barriers, thereby shortening the duration of the inhibitory effect. This can be achieved through targeted central fiscal transfers to support the construction of 5G networks, government cloud platforms, and other digital infrastructure in western and rural areas. In the middle and later stages, the focus should shift toward sustained institutional optimization. Meanwhile, equal access to digital public services should be incorporated into local government performance evaluation systems to establish binding mechanisms that ensure equitable advancement of DG across regions.

Second, promote the development of digital inclusive finance and increase education expenditure. Facilitate the growth of digital financial inclusion by integrating government databases with financial institution interfaces and enabling secure data sharing across departments. Such measures enable digital financial services to address credit and financing challenges more accurately and efficiently. Concurrently, education expenditure should be directed preferentially toward less developed regions and specifically allocated to digital skills training, thereby boosting human capital and advancing common prosperity.

Third, maintaining policy continuity and coordinating diverse governance tools to maximize the overall effectiveness of DG in advancing common prosperity. In addition, deepen a strategic integration of AI and blockchain to accelerate the maturation of DG and foster common prosperity. In more developed eastern regions, policy emphasis should transition from infrastructure “construction” to “deepened application.” Examples include adopting AI-powered approval systems and blockchain-based governance to transcend the inflection point and pioneer pathways to common prosperity underpinned by high-quality DG. In less developed western regions, policymakers should develop simplified digital service platforms adapted to local socioeconomic conditions. These efforts should strengthen public capacity to utilize digital tools in accessing services and opportunities, creating essential conditions for DG to improve income distribution.

6.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study provides new empirical evidence on the U-shaped relationship between DG and common prosperity and its transmission mechanisms, several limitations remain that warrant further investigation in future research. First, this study conducts analysis at the provincial level and fails to capture the differential effects of DG on common prosperity across cities and counties. Future research can employ city-level data for more granular empirical investigations. Second, due to data availability constraints at the provincial level, this study employs a Gini coefficient based on night lights data as a proxy for common prosperity. Although widely adopted in the literature, this measure may not fully capture income distribution details directly relevant to common prosperity. Future studies could incorporate more accurate micro-level income survey data to enhance the empirical robustness of the findings. Third, the DG index used in this study is sourced from a third-party database, which has inherent limitations in statistical coverage and indicator selection. Future research could develop a more comprehensive evaluation index system, for instance, the fiscal expenditure for DG. Finally, while this study identifies significant regional heterogeneity, the model remains unable to fully account for all region-specific factors, such as institutional quality and social capital. Future research can introduce more abundant microscopic data to explore heterogeneous effects.