1. Introduction

The shadow economy is a complex and elusive phenomenon with far-reaching implications for both developed and developing countries [

1]. Its size is variable and, in some European Union member states, may exceed one-quarter of the gross domestic product (GDP) [

2].

Understanding the factors influencing the scale of the informal economy is crucial for the effective formulation of economic policy, as well as for increasing budget revenues and reducing unfair competition. In recent years, growing attention has been paid to the role of technological development, the digitalization of the economy and society, and changes in payment structures as potential tools for curbing the shadow economy [

3,

4].

The literature frequently emphasizes that the scale of the shadow economy is shaped not only by economic factors but also by institutional and social determinants [

5,

6]. Among the most commonly cited factors are the level of taxation, the complexity of tax regulations, the efficiency of public administration, and citizens’ trust in state institutions [

7]. In recent years, increasing attention from researchers and policymakers has also focused on the impact of modern technologies, including the development of cashless payment systems and digital tools for monitoring economic activity, which can limit opportunities for concealing income and transactions.

The aim of this article is to examine the impact of selected macroeconomic factors, the level of economic digitalization, and implemented tax measures on the size of the shadow economy in European Union countries. The analysis assesses the relationships between economic development, the labor market, payment structures, indicators of digitalization in the economy and society, the level of digitalization in tax administration, and regulations limiting cash transactions, and the share of the informal economy.

Previous studies on the factors influencing the shadow economy in EU countries have primarily focused on macroeconomic determinants, such as economic growth rates, unemployment, and taxation levels. Much less attention has been devoted to the combined effects of digitalisation, payment structures, and fiscal innovations, and almost no research has systematically integrated these elements into a single analytical framework. Earlier research has largely sought to identify stable cause-and-effect relationships between different macroeconomic, social, and technological factors and the reduction in the shadow economy, whereas this study also emphasises the role of disruptions in this process. Moreover, these disruptions are analysed in the context of the varying levels of development already achieved by EU countries. This article fills this gap by bringing together, in one comprehensive empirical analysis, macroeconomic conditions, societal digitalisation, changes in payment structures, and tax administration tools (e.g., SAF-T, e-PIT) for EU countries over two decades, also covering periods of significant crises such as the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. The novelty of this approach lies not only in the breadth of factors examined simultaneously but also in the introduction of original indicators of tax administration digitalisation in UE countries developed by the authors, which have so far been largely absent from the literature. Such a broad perspective makes it possible to capture interactions between economic, institutional, and technological forces in shaping the shadow economy, offering insights that go beyond earlier studies and providing a stronger foundation for both academic debate and policy design. Moreover, the results demonstrate that reducing the shadow economy is a necessary condition for ensuring long-term fiscal stability and for effectively achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Based on a review of the relevant literature and in line with the study’s objective, the research question is formulated as follows:

RQ: Which factors—macroeconomic conditions, economic and social digitalisation, payment structures, and fiscal innovations in tax administration—play the most significant role in determining the size of the shadow economy in EU countries and to what extent do these mechanisms have broader implications for fiscal sustainability and sustainable development?

The research question was formulated in a general manner and further specified through a set of five hypotheses, which serve as a tool for operationalizing the main research problem:

H1: A higher level of economic development, and consequently the wealth and prosperity of a country, is a significant factor contributing to the reduction in the shadow economy’s share in GDP.

H2: An increase in the unemployment rate is a significant factor driving the expansion of the shadow economy, whereas higher wages and household consumption reduce its size.

H3: The share of card payments relative to GDP is negatively correlated with the level of the shadow economy.

H4: A higher level of digitalization in the economy and society contributes to a reduction in the shadow economy.

H5: The implementation of digital tax solutions (e.g., SAF-T or e-PIT/pre-filled forms) and restrictions on cash transaction values are associated with a significant decrease in the shadow economy’s share of GDP in EU countries.

The above hypotheses combine the macroeconomic level (growth and development, unemployment), the institutional level (tax solutions, regulations, payment-related measures), and the digital level (digitalisation of the economy, society and public administration). Together, they form a coherent set that allows for a comprehensive explanation of the determinants of the shadow economy and, consequently, the potential determinants for sustainable development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual Framework of the Shadow Economy

The ambiguity of the concept of the shadow economy is evidenced by the multiplicity of terms used in both academic literature and the media [

8]. Terms such as informal economy, unofficial economy or underground economy are often used interchangeably to denote economic activity conducted without the knowledge of the state [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] and will be treated as interchangeable throughout this paper.

The concept of the shadow economy encompasses a wide range of phenomena. Some definitions focus on hidden production [

14], while others emphasize hidden employment [

15]. In practice, various forms of activity outside the knowledge of the state can be observed—unregistered entities conceal all of their operations, whereas registered enterprises may choose to hide part of their activities in order to reduce their tax liabilities [

16]. P.M. Gutmann defines the shadow economy as a broad spectrum of economic activities that escape fiscal registration and are, to a large extent, absent from official statistics [

17]. In the work of Schneider et al. [

18], the definition of the shadow economy includes all economic activities and the income derived from them that evade or otherwise circumvent government regulations, taxation, or supervision. In this study, the shadow economy is understood as activity deliberately concealed from the state. It covers both income-generating activities that are legal in nature but unreported for tax purposes, borderline practices, as well as outright illegal or criminal activities [

19]. This understanding is consistent with the approach presented by European institutions (the European Commission, Eurostat, etc.) [

20,

21,

22].

There are multiple reasons for engaging in the shadow economy, most frequently identified in the literature [

5,

23,

24]:

avoiding the payment of taxes and social security contributions;

avoiding compliance with specific labor market standards, such as minimum wages, maximum working hours, or safety regulations;

avoiding compliance with certain administrative procedures, such as completing statistical questionnaires or other administrative forms imposed by the state;

the illegality of the goods or services offered.

The shadow economy is thus an undeniably complex phenomenon [

25], the size of which is determined by a variety of factors. The impact of individual factors on its development may be perceived and interpreted differently within the framework of economic theory. In this context, several theories can be distinguished that offer alternative approaches to explaining its causes.

According to neoliberal theory, excessive government intervention, high taxation and burdensome regulations may encourage entrepreneurs to operate in the shadow economy [

26,

27]. Entrepreneurs avoid regulations and bureaucratic procedures imposed by the state in order to reduce associated costs. They may also evade the obligation to pay social or health insurance contributions by employing workers “off the books.” This allows them to significantly lower operating costs and gain a competitive advantage in an unfair manner [

28].

In their study, Johnson et al. [

29] analyzed the phenomenon of the unofficial economy in countries undergoing economic transition, i.e., Eastern European countries and those of the former Soviet Union. According to the authors, excessive government regulations, bureaucratic obstacles and weak law enforcement led to the growth of the shadow economy in countries transitioning from centrally planned to market economies. Participation in the shadow economy served as a way to avoid complex formalities.

In the article by Djankov et al. [

30], the issue of the shadow economy is not directly addressed, but the study’s findings are related to this topic. The authors point out that complex and time-consuming regulations regarding registration and other market entry formalities may discourage the registration of new enterprises. As a result, they may either refrain from operating or conduct their activities without registration.

In recent studies, neoliberal theory is also strongly associated with the motives behind the development of the shadow economy. For example, Gërxhani and Cichocki [

31] emphasize that low trust in institutions, as well as complex and excessive regulation, foster tendencies toward hidden activities encompassing both legal and illegal actions. In turn, research by Barra and Papaccio [

32] indicates that higher regulatory quality, considered as an indicator of institutional quality, significantly reduces the size of the shadow economy. In regions of Italy with higher institutional quality and stronger regulatory compliance, the level of hidden employment is lower.

In contrast to neoliberalism, political economy theory suggests that the shadow economy is the result of insufficient state intervention both in the economy and in the provision of social protection, social transfers, or worker protection [

25,

33]. In situations where the state does not provide adequate safeguards, workers may be forced to engage in the informal economy. In sectors with low regulation and lack of enforcement of labor laws, employees may work without formal contracts. Without state support, such as minimum wages or protection against dismissal, these individuals often accept employment in the shadow economy to secure a source of income, despite lacking insurance and social benefits [

34].

Moreover, it has been suggested that the political economy approach is more applicable to relatively poor populations, whereas the neoliberal approach better explains informal activities among relatively wealthier social groups within a given country [

35,

36,

37,

38].

According to Zolkover and Kovalenko [

25], who analyzed scientific studies published in journals indexed in Scopus and WoS between 2014 and 2020, three main groups can be distinguished that categorize research on theories of the shadow economy. These are as follows:

The shadow economy arises primarily due to low levels of economic development in a country;

The shadow economy arises due to high unemployment;

The growing share of the shadow economy in the economy is a consequence of ineffective government policies.

Although the literature presents numerous concepts and determinants of the shadow economy, there is a lack of a unified theoretical framework that comprehensively integrates macroeconomic, institutional, fiscal, and technological dimensions. Research typically focuses on a single aspect, such as economic development, employment, or tax avoidance, often neglecting the interactions between them. Moreover, many analyses are conducted at the national level, whereas cross-country comparisons within the EU that simultaneously consider these determinants are particularly important.

2.2. Economic Development and the Shadow Economy

Schneider et al. [

18] confirm in their research that, alongside tax burdens, an unstable economic situation is a significant factor affecting the size of the shadow economy. The study results show a strong influence of economic crises on shadow economy activities—during crises, the scale of the shadow economy increases substantially [

39,

40]. In many countries, it reached peak levels during the financial crisis of 2008 [

16]. In times of economic downturn, the shadow economy may be not only a consequence but also a cause of a greater decline in gross domestic product and can further propagate the crisis [

41]. Moreover, the shadow economy is generally associated with low productivity, poverty, high unemployment and slower economic growth [

42].

During periods of economic downturn, the shadow economy can contribute to a deepening of the slowdown by weakening formal structures or reducing tax revenues. Its long-term impact on the economy is negative, leading to the weakening of state institutions. According to Arandarenko [

41], instead of creating new jobs, it produces a displacement effect (“bad jobs just drive out the good ones”). On the other hand, it is emphasized that the shadow economy can act as a safety net during crises—in the face of rising unemployment and declining incomes, entrepreneurs and workers may turn to informal economic activities as a means of survival. Thus, the shadow economy can play a stabilizing role in the short term, while in the longer perspective it contributes to the deepening of economic crises [

43].

Interesting conclusions were presented by La Porta and Shleifer [

44], who argue that activities within the shadow economy typically remain small, low in productivity, and in the long run are displaced by more competitive ones from the formal sector, which is reflected in GDP statistics. Consequently, the reduction of the shadow economy does not result from changes within informal structures, but rather from the growing institutional and competitive strength of the formal sector. While this mechanism has been well documented in the context of developing countries, it has not been conclusively examined in relation to EU member states, which are characterized by higher levels of institutionalization and digitalization. It remains to be investigated to what extent this mechanism holds in highly developed economies, particularly during periods of crisis.

Previous studies consistently confirm that higher levels of economic development contribute to reducing the shadow economy [

16,

23]. However, the mechanisms underlying this relationship remain insufficiently understood. The literature offers no clear answer as to whether the reduction of the shadow economy is primarily a direct consequence of higher national income, or rather the result of accompanying factors such as improved efficiency of tax administration, ongoing digitalization, or the increasing share of cashless payments. These considerations form the basis for formulating hypothesis H1.

2.3. Labour Market Conditions and Household Welfare

Some authors argue that the shadow economy emerges in the economy primarily due to high unemployment [

45]. This means that the higher the share of people remaining unemployed in the formal sector, the more of them seek alternative sources of income in the shadow economy. An interesting study in this regard was conducted in Romania [

46], which demonstrated a unidirectional causal relationship, in which changes in the unemployment rate affect the size of the shadow economy.

An increase in the unemployment rate leads to a significant decline in household consumption, which may stimulate activity in the informal sector. Moreover, even households that do not directly experience unemployment reduce their consumption in response to rising unemployment, thereby promoting the expansion of the informal sector [

47]. According to Sahnoun and Abdennadher [

48], the impact of unemployment on the size of the shadow economy depends on institutional quality. In developing countries, unemployment increases informal economic activity, particularly when corruption levels are high, whereas in developed countries this effect is weaker or even reversed. Strong institutions and effective administration can mitigate the impact of unemployment on the shadow economy.

Evidence from Putniņš and Sauka [

49] on post-transition economies indicates that the gap between official wages and employees’ expectations is also a significant factor—the larger the discrepancy, the greater the tendency to engage in shadow economy activities. Furthermore, in some countries, higher social transfers may reduce the need to work in the informal sector [

50], whereas in others, low wages encourage employees to participate in informal economic activities.

Although there are studies examining the impact of unemployment, consumption, and income levels on the shadow economy, there is a lack of comparative research assessing the extent to which labor market factors influence the shadow economy during periods of economic and social crises. Based on the above, hypothesis H2 can be formulated.

2.4. Payment Structures and Cashless Transactions

With the development of cashless payments, an increasing number of studies suggest that cash plays a significant role in the growth of the shadow economy [

51]. This view challenges traditional economic theories. While earlier research focused primarily on regulatory gaps and tax avoidance, the new line of research emphasizes the potential impact of cash transactions on the persistence of unreported economic exchanges. Cash leaves no trace in accounting records and payments made with it can remain anonymous. The literature posits that if cash were seriously restricted or eliminated, crime would be significantly reduced and the shadow economy would be drastically curtailed, as most transactions in the shadow economy are typically conducted in cash [

52]. Many European countries promote cashless transactions in B2B and B2C operations while simultaneously introducing restrictions on cash use [

53,

54]. A study conducted by EY across eight European countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Poland, Serbia, Slovakia and Slovenia) confirmed that a 100% increase in the value of cashless payments would reduce the shadow economy in the analyzed countries by 0.6–3.7% of GDP and increase government revenues by 0.1–0.8% of GDP [

55,

56]. According to an analysis by the Bank of Italy, a 1% increase in the share of cashless payments results in a 0.4% rise in VAT revenues due to greater compliance with tax regulations [

57]. Other researchers conducted an analysis covering 25 European Union countries and estimated that an additional ten card transactions per capita per year reduces the VAT gap by 0.08% to 0.2% of GDP [

58].

Many studies have primarily focused on the static relationship between the share of cashless payments and the shadow economy, without sufficiently accounting for strong economic shocks or interactions with other determinants. It should also be noted that the evidence regarding the role of cashless payments is inconclusive. Kowal-Pawul and Lichota [

9] point out that despite the dynamic increase in cashless transactions in Poland, the size of the shadow economy increased after 2020. This suggests that crisis and macroeconomic factors (such as the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and economic slowdown) or other factors (e.g., complex tax legislation, increases in the minimum wage) may offset the positive effect of payment structure. There is a lack of research examining this issue across all EU countries. Marmora, Brenden, and Mason [

59] emphasize that merely promoting cashless payments is insufficient to reduce the demand for cash, especially in countries with a large shadow economy. This implies that the effectiveness of such measures depends on institutional and macroeconomic conditions. These considerations form the basis for formulating hypothesis H3.

2.5. Digitalisation of Society and Tax Governance

Some studies also indicate that a higher level of digitalization in society and the economy positively affects the reduction of the shadow economy [

60]. Digitalization of tax administration, including e-services, automated VAT reporting and the limitation of cash payments, increases the transparency of economic transactions and reduces opportunities to operate outside the official system [

61,

62]. This effect is particularly strong in countries with low levels of corruption, where digital tools are used more effectively [

60].

Studies from developing countries also confirm that the digitalization of public services and electronic reporting systems can limit opportunities for tax evasion and increase transparency [

63]. Evidence from Hungary suggests that the introduction of online cash registers increased reported turnover and improved VAT compliance, particularly among smaller businesses, with the greatest effects observed in retail trade as well as in the hospitality and catering sectors [

64]. Kowal-Pawul and Przekota [

61] indicate that the implementation of digital solutions in Poland enables more effective monitoring of economic transactions, thereby hindering informal sector activity. However, despite the positive effects of digitalization, the problem of the shadow economy persists and requires further measures in tax policy and administration.

Previous research shows that the digitalization of tax administration and public services increases transparency and reduces informal economic activity. However, many studies are case-based, focusing on selected countries and/or individual tools (e.g., e-invoicing, SAF-T) over a short-term perspective [

61,

65]. Comprehensive analyses comparing different digitalization instruments and their long-term effectiveness across various countries and institutional or macroeconomic contexts (such as economic crises) are still lacking.

Some studies examining broader digitalization of society and the economy also confirm its association with reducing the shadow economy. Yurevich [

3] demonstrated that a higher level of digitalization reduces the share of the informal economy in GDP, although these effects vary significantly depending on institutional quality and may be nonlinear. Overall, modeling results suggest that excessive acceleration of digital transformation in weak institutional environments may stimulate informal activity, as the lack of an appropriate regulatory framework and oversight limits the effectiveness of digital tools. At the same time, despite growing interest in this issue, it remains insufficiently understood which areas of digitalization—such as the development of citizens’ digital skills or the dissemination of digital public services—are crucial for effectively reducing the shadow economy in highly developed economies. These considerations provide the basis for formulating hypotheses H4 and H5.

2.6. Sustainable Development and the Shadow Economy

Sustainable development is one of the key paradigms of contemporary economic, social, and environmental policy [

66]. It is founded on a balance between three pillars: economic growth, social cohesion, and environmental protection. Achieving these objectives requires stable institutions, transparent economic mechanisms, and a high level of public trust in the state [

67]. In this context, the shadow economy remains a major challenge—it represents a portion of economic activity that is neither reported nor included in official statistics, often taking place outside tax and legal regulations. The relationship between sustainable development and the shadow economy is complex and multidimensional, encompassing both economic and social dimensions [

68]. The shadow economy undermines the economic foundations of sustainable development. Reduced tax revenues limit the state’s capacity to invest in infrastructure, education, and innovation—all of which are crucial for long-term growth [

69]. The parallel economy also exacerbates inequality, as the benefits of informal activity are often captured by narrow groups, while the costs are borne by society as a whole. In the social dimension, the shadow economy weakens cohesion and citizens’ trust in public institutions [

70]. When a significant share of the population operates outside the official system, the sense of equality before the law diminishes, and compliance with regulations ceases to be the norm. This leads to an erosion of social capital, which is essential for achieving collective development goals. In the environmental dimension, the shadow economy can likewise pose a threat [

71]. Informal activities often disregard environmental protection standards and technological requirements, resulting in greater resource exploitation or uncontrolled pollution. Consequently, it hinders the achievement of ecological objectives, which are an integral component of sustainable development. Overall, the shadow economy stands in clear contradiction to sustainable development. The informal sector undermines the state’s ability to implement development-oriented policies, weakens social cohesion, and contributes to environmental degradation. Reducing its scale is therefore one of the key prerequisites for achieving sustainable development goals. The implementation of modern technological solutions [

72], the strengthening of institutions, the building of public trust [

73], and the development of a transparency-based fiscal policy [

74] are measures that can gradually minimize the size of the shadow economy, thereby bringing the economies of the European Union and other countries closer to a sustainability-driven development model.

Research shows that the determinants of the shadow economy are complex and multifaceted and their impact on the economy is not always straightforward. Therefore, further analyses are necessary to identify which factors most significantly influence the size of the shadow economy.

3. Materials and Methods

The empirical research was based on data covering all European Union member states. The analysis focused on the size of the shadow economy in relation to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) over the years 2003–2022. This period includes both years of stable growth and two major crises—the global financial crisis of 2008–2009 and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020—which allows for a more comprehensive capture of the determinants shaping the shadow economy. Based on the literature review, a set of independent variables was identified as potential factors influencing the size of the shadow economy. Among these, the following factors were tested:

The study was divided into six stages. In each stage, appropriate methods were applied to explain the impact of potential factors on the development of the shadow economy. The division into six stages reflects the sequential phases of our empirical strategy: from descriptive trends (stage 1) to econometric modelling (stages 2–4), and from institutional instruments (stage 5) to comparative synthesis (stage 6), emphasizing the combined role of empirical data and institutional context in explaining the size and dynamics of the shadow economy.

Stage 1. Trends in the development of the shadow economy:

The dynamics of the shadow economy were presented for each EU member state (data on the size of the shadow economy from [

78]);

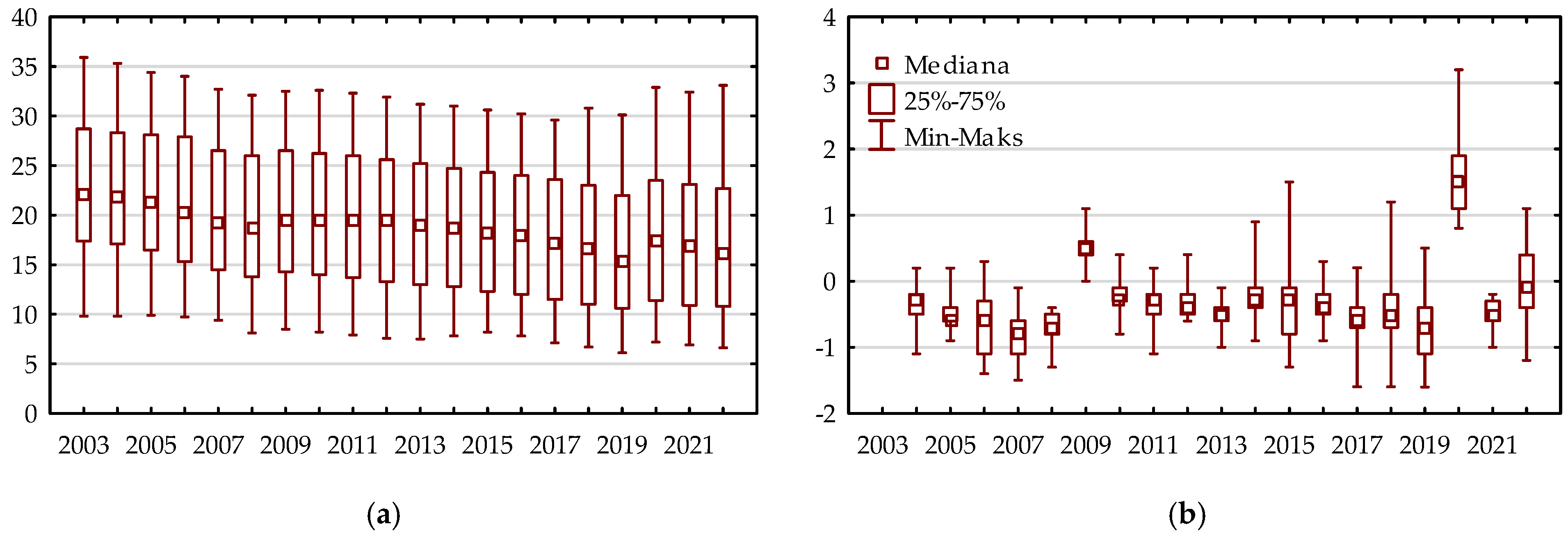

Descriptive statistics (median, quartiles, min, max) of the shadow economy level were calculated for each year and illustrated using a boxplot;

Descriptive statistics (median, quartiles, min, max) of annual changes in the shadow economy were also calculated and visualized using boxplots;

Changes in the shadow economy level were highlighted for each country in years that were critical due to significant global events;

Correlation analysis was conducted between the level of the shadow economy and its rate of change;

The relationship between overall trends in the shadow economy across all EU member states was analyzed.

The research in this section makes it possible to determine the scale of the shadow economy, identify long-term tendencies observed throughout the study period, examine interdependencies between countries and assess the impact of geopolitical events on the dynamics of the shadow economy.

Stage 2. Macroeconomic determinants of the shadow economy. A multilevel analysis model was carried out, in which the level of the shadow economy (as well as its increments) was conditioned by the following macroeconomic indicators:

The modelling approach is based on multilevel analysis, which allows for an accurate assessment of the impact of macroeconomic factors on the shadow economy within a country–time panel. A key issue here is accounting for the hierarchical structure of the data. In panel datasets, yearly observations are “nested” within individual countries, meaning that the observations are not fully independent. Traditional regression models assume independence of data, which in this context would lead to incorrect estimation of standard errors and potentially biased inferences. In contrast, a multilevel model enables the simultaneous consideration of variance between countries and variance over time, allowing the effect of country-specific characteristics (e.g., institutions, culture, tax system quality) to be disentangled from the effect of macroeconomic variables observed over the years. This makes it possible to more precisely estimate the impact of factors such as GDP, unemployment rate, level of digitalization, or payment structure on the size of the shadow economy, without the risk of results being distorted by country-specific idiosyncrasies. Additionally, multilevel analysis controls for autocorrelation of observations within countries and heteroskedasticity across them, thereby increasing the reliability of the results. It also enables the examination of effects at different levels—both time-varying and country-specific—offering a more comprehensive view of the mechanisms shaping the shadow economy. Thus, the use of multilevel analysis provides more robust and valid conclusions that account for both temporal dynamics and cross-country heterogeneity within the examined panel.

In this assessment, a two-level model was used, with the first level representing the year and the second level representing the country. The IGLS procedure in MLwiN version 3.05 was applied. For each model, a set of statistics was reported:

Structural model parameters—intercept (B0) and regression coefficients B1 for economic level (various variables), B2 for unemployment and B3 for HICP;

Standard errors of the structural parameters;

Significance levels for the structural parameters;

VIF statistics;

Variance in the structural parameters at the country level;

The Pearson correlation coefficient between intercepts and regression coefficients at the country level;

Goodness-of-fit statistic: −2 ILL.

Stage 3. The impact of card payments on the shadow economy. Using a procedure analogous to that in Part 2, the effect of card payment volumes on the shadow economy was determined:

The rationale for this analysis is that recorded transactions can potentially hinder the functioning of the shadow economy.

Stage 4. The significance of the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) and its Integration of Digital Technology (IDT) component. The DESI ranking concerns the broadly defined quality of the economy. It takes into account four components:

Human capital—internet skills, advanced skills and digital development;

Connectivity—fixed and mobile broadband access, broadband prices;

Integration of Digital Technologies—digital intensity, digital technologies for business, e-commerce;

Digital Public Services—e-government.

The significance of these components for reducing the shadow economy lies in the expectation that as the quality of economic functioning improves, the level of the shadow economy will decline. Integration of Digital Technology promotes automation, visibility and formalization of transactions; Connectivity ensures better access to e-services; Digital Skills foster greater readiness to operate legally; and Digital Public Services reduce bureaucracy and make tax compliance more convenient. Altogether, these factors may decrease the motivation to operate outside the formal system.

In this part, one of the DESI components, namely Integration of Digital Technology, was examined. It may be linked to reducing the shadow economy, particularly in the context of business digitalization and the automation of economic processes. Several specific connections and mechanisms can be highlighted, primarily due to processes such as digitalization, which increases transparency of activities; e-commerce and cashless payments, which formalize transactions; cloud computing and big data, which enable automation and reporting; and data sharing, which improves law enforcement. It is expected that the higher the level of digital technology integration by businesses, the more difficult it becomes to operate within the shadow economy.

The analysis in this part was based on the correlation between a country’s ranking position and the level of the shadow economy in a given year:

Stage 5. Tax system measures. Tax administration digitalization, tax reporting and restrictions on cash payments are among the most important instruments for reducing potential tax fraud and, consequently, limiting the shadow economy. The analysis in this part was based on descriptive statistics, comparing countries that implement a given measure with those that do not. The data used in this section are from 2022.

Stage 6. Changes in the level and growth of the shadow economy over time depending on GDP and card payment values. This summarizing section presents the significance of two factors: GDP per capita, which proved to be a real determinant and card payment values, which are sometimes indicated in the literature as important but were found to be a secondary factor in this study. Waffle charts and multilevel modeling were used for the analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Trends in the Development of the Shadow Economy

The shadow economy is one of the most important problems of modern economies. Entrepreneurs entering the shadow economy, people working without an employment contract, tax fraud and other events cause various problems for the economy. On the one hand, it is an undeniable depletion of the state budget and in a situation of deficit and public debt, the necessity of its repayment falls on those working legally. On the other hand, individuals and enterprises operating in the shadow economy cannot be cut off from public services. They benefit on equal terms from education, healthcare, culture and other social services. Reducing the shadow economy can bring many benefits to the economy, above all it allows for a reduction in the budget deficit, levels the playing field in the economy and helps stabilize the labor market. Therefore, countries are interested in keeping the shadow economy as small as possible.

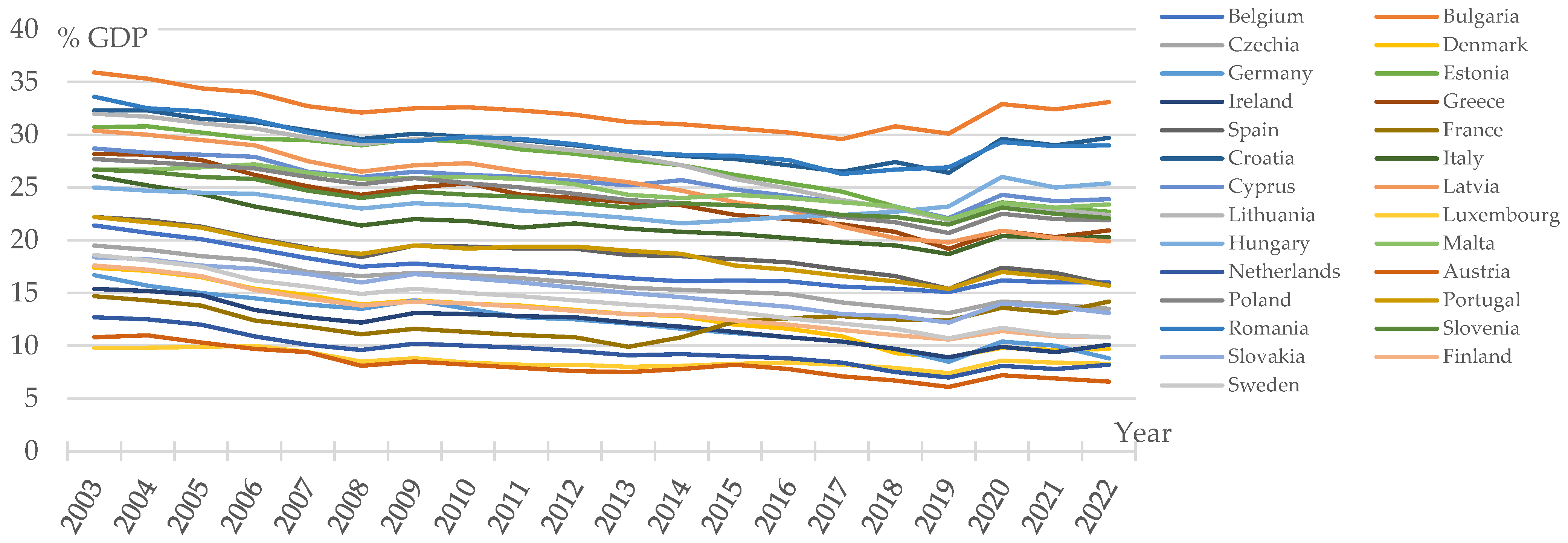

In the countries of the European Union, significant differences in the level of the shadow economy can be observed (

Figure 1), reaching from several to even several dozen percentage points. In 2003, the level of the shadow economy ranged from 9.8% of GDP (Luxembourg) to 35.9% of GDP (Bulgaria), whereas in 2022 it ranged from 6.6% (Austria) to 33.1% of GDP (Bulgaria).

Despite the observed decline in the level of the shadow economy between 2003 and 2022, the reduction was not uniform (

Figure 1). Two years can be identified in which the level of the shadow economy increased, namely 2009 and 2020. The reasons for the rise in the shadow economy in these two years were different: in 2009 it was the global economic crisis, while in 2020 it was the lockdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. It is quite interesting that during times of extremely severe economic difficulties, such as in 2009 and 2020, in every country—regardless of whether the level of the shadow economy was high or low—an increase in the shadow economy indicator occurred. It also turns out that the shutdown of the economy, even if only temporary, produces much more serious consequences than a traditional economic crisis. The effects of the economic closure in some countries triggered secondary local economic crises, which is visible in the statistics on changes in the shadow economy in 2022.

What happened in 2009 and 2020 was likely partly due to the decline in GDP and, consequently, the increase in the ratio of the shadow economy to GDP. However, it can also be assumed that regardless of whether a country is rich or poor, in times of crisis entrepreneurs and individuals, in order to survive and secure their livelihoods, resort to various strategies, including entering the shadow economy. Periods of economic calm and stability, on the other hand, tend to favor a decline in the shadow economy. This phenomenon is particularly visible in

Figure 2b, where in all years (except 2009 and 2020) the medians of changes in the ratio of the shadow economy to GDP are negative, which is the expected and beneficial state for the economy.

The way in which individual countries cope with the phenomenon of the shadow economy is presented in

Table 1. Over the entire study period, the level of the shadow economy increased only in Hungary (by 0.4 percentage points), while in the remaining countries it decreased, with the largest decline observed in Latvia (by 10.5 percentage points). For the entire group of countries, the median amounted to −5.4 percentage points. The significance of the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic becomes evident when comparing the 2022/2003 statistics with the 2019/2003 figures. In 2019, the statistics were much more favorable, as the decline in the shadow economy ranged from 1.8 percentage points for Hungary to 10.6 percentage points for Latvia, while the median for the entire group of countries stood at −6.6 percentage points.

The statistics for the 2020 crisis are significantly worse than for the 2009 crisis. In 2020, compared to 2019, every country recorded a greater increase in the shadow economy than in 2009 compared to 2008. The increase in the share of the shadow economy in GDP in 2020 relative to 2019 ranged from 0.8 percentage points in Finland to 3.2 percentage points in Croatia, with a median of 1.5 percentage points. In 2009, compared to 2008, the level of the shadow economy in relation to GDP increased from 0.0 percentage points in Romania to 1.1 percentage points in Spain, with a median of 0.5 percentage points. Thus, the statistics for 2009 are not as unfavorable as those for 2020.

The rate of growth of the shadow economy in 2009 relative to 2008 was practically independent of the initial level of the shadow economy in 2008 (

Figure 3a). The value of the correlation coefficient was −0.1360. In contrast, in 2020 the increase in the shadow economy relative to 2019 was dependent on the initial level of the shadow economy in 2019 (

Figure 3b). The value of the correlation coefficient in this case was 0.7587. Countries with a higher level of the shadow economy reacted much more negatively to the crisis.

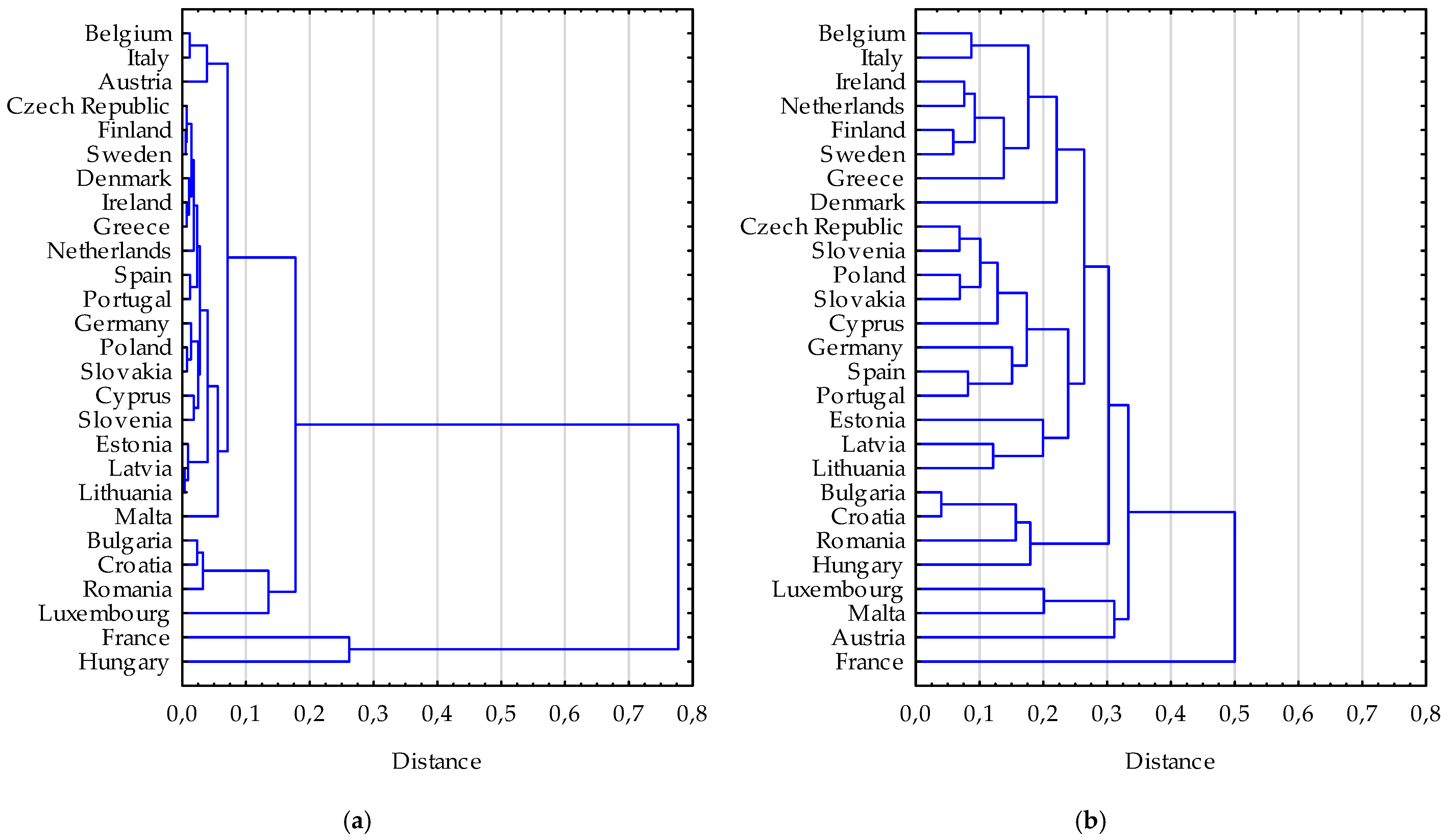

The correlation between the level of the shadow economy (

Figure 4a) and the increments in the shadow economy (

Figure 4b) for the entire group of European Union countries is relatively strong. Apart from France and Hungary, the difference in the strength of the trend for shadow economy levels is below 0.2 (measured by Pearson’s correlation coefficient), while for increments it is below 0.5 and excluding France, Malta and Austria, even below 0.3. This is a rather natural phenomenon, as these countries form a community.

These results indicate that economic impulses quickly transmit from one country to another, as states implement similar or nearly identical legal solutions, forming a more or less homogeneous politico-economic system. This is precisely why the directions of change are consistent. Nevertheless, the variation in the level of the shadow economy remains significant (

Figure 1), which means that the question of the determinants of shadow economy levels remains relevant.

4.2. Macroeconomic Determinants of the Shadow Economy

The observation that economic crises (in this study, 2009 and 2020) were accompanied by an increase in the shadow economy suggests that one of the potentially most important factors affecting the size of the shadow economy may be the wealth of a country. This hypothesis can be verified by assessing the impact of selected macroeconomic variables on the level and growth of the shadow economy. If correct, macroeconomic variables should explain differences in the shadow economy across countries.

Examining the impact of macroeconomic variables representing national wealth effectively addresses the following questions:

GDP per capita—does a larger, wealthier economy generally exhibit a smaller share of the shadow economy?

Compensation—does the growth of employee wages and thus household wealth, contribute to reducing the shadow economy?

Consumption of households—does increased demand in the economy and thus higher sales of goods and services, help limit the shadow economy?

Consumption of government—does increased government expenditure, reflecting a welfare state concept (improved quality of public services), contribute to reducing the shadow economy?

The models presented below also take into account the unemployment rate and HICP changes. Four separate models are necessary because GDP per capita, compensation, household consumption and government consumption are strongly positively correlated.

This relationship is graphically illustrated in

Figure 5.

For each macroeconomic variable (GDP per capita, compensation, household consumption and government consumption), a higher value corresponds to a lower level of the shadow economy. The obtained correlation coefficients are as follows:

GDP per capita—shadow economy: −0.7298;

Compensation—shadow economy: −0.8142;

Consumption of households—shadow economy: −0.8136;

Consumption of government—shadow economy: −0.8022.

In contrast, for the unemployment rate and HICP, no significant relationship was observed; therefore, these variables can only serve as auxiliary factors in explaining the shadow economy and are not dominant determinants. The obtained parameters are as follows:

The level model (

Table 2) allows us to conclude that each of the variables (GDP per capita, compensation, consumption of households and consumption of government) is statistically significant in determining the level of the shadow economy (

p-value < 0.001). Higher values of these variables are associated with a lower level of the shadow economy (negative regression coefficients).

Each variable from

Table 2 can thus be used to represent the wealth of a country as a predictor of the shadow economy. Specifically:

An increase in GDP per capita by EUR 1000 leads to a reduction in the shadow economy’s share of GDP by 0.611 (±0.024) percentage points. Considering that the average GDP per capita for the entire group of countries is EUR 26,925, an average increase in GDP per capita of 3.71% can contribute to an average decrease in the shadow economy’s share of GDP by 0.611 percentage points. Proportionally, a 1% increase in GDP per capita corresponds to a 0.165 percentage point decrease in the shadow economy’s share of GDP.

An increase in compensation per capita by EUR 1000 leads to a reduction in the shadow economy’s share of GDP by 0.345 (±0.012) percentage points. Considering that the average compensation for the entire group of countries is EUR 28,734 per capita, an average increase in compensation of 3.48% can contribute to an average decrease in the shadow economy’s share of GDP by 0.345 percentage points. Proportionally, a 1% increase in compensation corresponds to a 0.099 percentage point decrease in the shadow economy’s share of GDP.

An increase in household consumption per capita by EUR 1000 leads to a reduction in the shadow economy’s share of GDP by 0.870 (±0.029) percentage points. Considering that the average household consumption for the entire group of countries is EUR 12,891 per capita, an average increase in household consumption of 7.76% can contribute to an average decrease in the shadow economy’s share of GDP by 0.870 percentage points. Proportionally, a 1% increase in household consumption corresponds to a 0.112 percentage point decrease in the shadow economy’s share of GDP.

An increase in government consumption per capita by EUR 1000 leads to a reduction in the shadow economy’s share of GDP by 1.529 (±0.054) percentage points. Considering that the average government consumption for the entire group of countries is EUR 5361 per capita, an average increase in government consumption of 18.65% can contribute to an average decrease in the shadow economy’s share of GDP by 1.529 percentage points. Proportionally, a 1% increase in government consumption corresponds to a 0.082 percentage point decrease in the shadow economy’s share of GDP.

Thus, from the perspective of proportional response, GDP per capita appears to have the strongest impact.

As expected, unemployment and HICP are only supplementary and do not possess high statistical significance (the ratio of the regression coefficient to the standard error for these variables is approximately ten times smaller than for GDP per capita, compensation, consumption of households and government consumption). In the model including both GDP per capita and government consumption, the unemployment variable is statistically insignificant. Overall, a 1 percentage point change in the unemployment rate contributes to a change in the shadow economy’s share of GDP of approximately 0.075–0.148 percentage points, while a 1 percentage point change in HICP contributes to a change in the shadow economy’s share of GDP of approximately 0.200–0.288 percentage points.

The models are well specified (VIF statistics close to 1).

Similar conclusions can be drawn from the analysis of the growth model (

Table 3). The growth of three of the variables (GDP per capita, compensation, consumption of households), apart from the fourth (government consumption), is statistically significant in shaping the growth of the shadow economy. Higher growth in these variables is associated with a greater reduction in the shadow economy. Specifically:

A change in the growth rate of GDP per capita by 1 percentage point results in a change in the growth rate of the shadow economy by 0.03252 percentage points.

A change in the growth rate of Compensation by 1 percentage point results in a change in the growth rate of the shadow economy by 0.01738 percentage points.

A change in the growth rate of Consumption of households by 1 percentage point results in a change in the growth rate of the shadow economy by 0.02339 percentage points.

A change in the growth rate of Consumption of government by 1 percentage point results in a change in the growth rate of the shadow economy by 0.00077 percentage points.

Thus, both in the long term (level model,

Table 2) and in the short term (growth model,

Table 3), the most important factor in reducing the shadow economy is GDP.

In the growth model, unemployment plays a greater role, as expected, exerting a negative impact on the shadow economy. A 1 percentage point change in the growth rate of unemployment results in a change in the growth rate of the shadow economy ranging from 0.060 to 0.128, depending on the model (interaction with the main macroeconomic variable).

Observing the ratio of regression coefficients to their standard errors, it can be stated that unemployment, as a factor affecting the shadow economy in the short term, is only slightly less important than GDP growth (regression-to-standard-error ratios: −4.37 for GDP vs. 3.16 for unemployment in model 1), more important than compensation (−3.30 for compensation vs. 6.82 for unemployment in model 2) and almost as important as household consumption (−4.08 for household consumption vs. 3.72 for unemployment in model 3). Consumption of government is practically negligible, as compared to unemployment it is statistically insignificant (−0.16 for government consumption vs. 7.11 for unemployment in model 4).

In the short term, changes in inflation have practically no impact on the growth rate of the shadow economy—in every model, the regression coefficient for the HICP variable is statistically insignificant.

The models are well-specified, with VIF statistics below 5.

From a practical perspective, the most important aspect is how economic changes translate into changes in the shadow economy. It turns out that a doubling of economic growth corresponds, on average, to a decrease in the growth of the shadow economy by –3.252 percentage points. Achieving a doubling of GDP often takes several, sometimes more than a dozen, years. This explains why, despite the passage of many years (the 2003–2022 period), differences in the levels of the shadow economy between countries remain significant. Nonetheless, GDP growth is the primary factor in reducing the shadow economy. In the case of unemployment, an increase (decrease) of 1 percentage point contributes to a decrease (increase) in the shadow economy by approximately 0.06–0.13 percentage points, depending on the model specification.

In general, it appears that macroeconomic variables, primarily GDP and thus the wealth of a country, have a significant impact on the level of the shadow economy. Changes in GDP (its growth) and in unemployment (its decline) can contribute to an improvement in the situation, but these are long-term processes.

4.3. Impact of Card Payments on the Shadow Economy

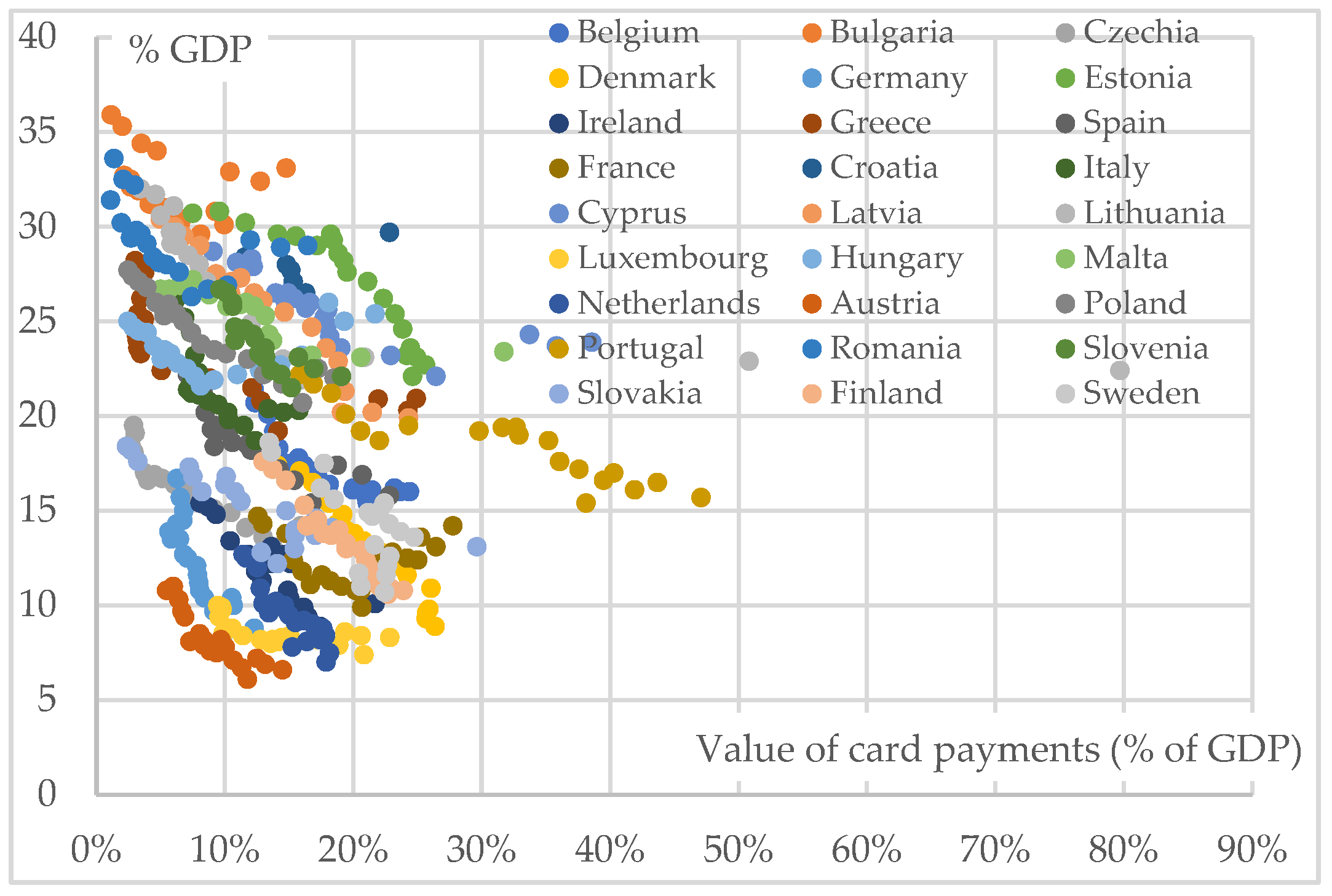

The impact of card payments on the shadow economy may complement the influence of macroeconomic factors. Card transactions are, to some extent, traceable and their recording could potentially hinder the functioning of the shadow economy. Evidence for the potential importance of this factor is visible in

Figure 6, where higher ratios of card payments to GDP are on average associated with a lower level of the shadow economy. The overall correlation coefficient for this scatterplot is −0.2999. However, this relationship may also be spurious, reflecting the effect of GDP: higher GDP corresponds to a smaller shadow economy and over time, as GDP grows, the shadow economy tends to shrink. Simultaneously, with technological progress and convenience, an increasing number of transactions are made via card payments. Therefore, the observed relationship between card payments and the shadow economy may be indirect. This can be further clarified by analyzing the responses of both levels and increments of the variables.

It can therefore be concluded that, based on variable levels (

Table 4), there is a significant relationship between the value of card payments and the level of the shadow economy. The correlation coefficient between the intercepts and the regression coefficients for individual countries is negative, indicating that higher levels of card payments are, on average, associated with lower levels of the shadow economy. This is consistent with the point distribution in

Figure 7 and the overall correlation coefficient. Moreover, with a 1 percentage point increase in the share of card-paid transactions in GDP, the share of the shadow economy in GDP decreases on average by 0.00269 percentage points.

On the other hand, a different conclusion emerges from the model of variable increments (

Table 5). It turns out that the growth in the value of card payments does not have a statistically significant effect on the increase in the shadow economy (

p-value = 0.282). This may indicate that the apparent relationship between the value of card payments and the level of the shadow economy is driven primarily by underlying trends and is therefore essentially spurious.

Focusing only on the crisis periods (

Figure 7), a weak positive correlation can be observed between the growth of card payments and the growth of the shadow economy (0.1393 in 2009 and 0.3782 in 2020). This positive relationship is not expected, because if it were significant, it would imply that the shadow economy increases as card payments increase. In reality, this reflects the fact that the number of card payments rises year by year (even during crises), while coincidentally the crisis itself caused an increase in the shadow economy. The resulting positive correlation therefore lacks practical significance.

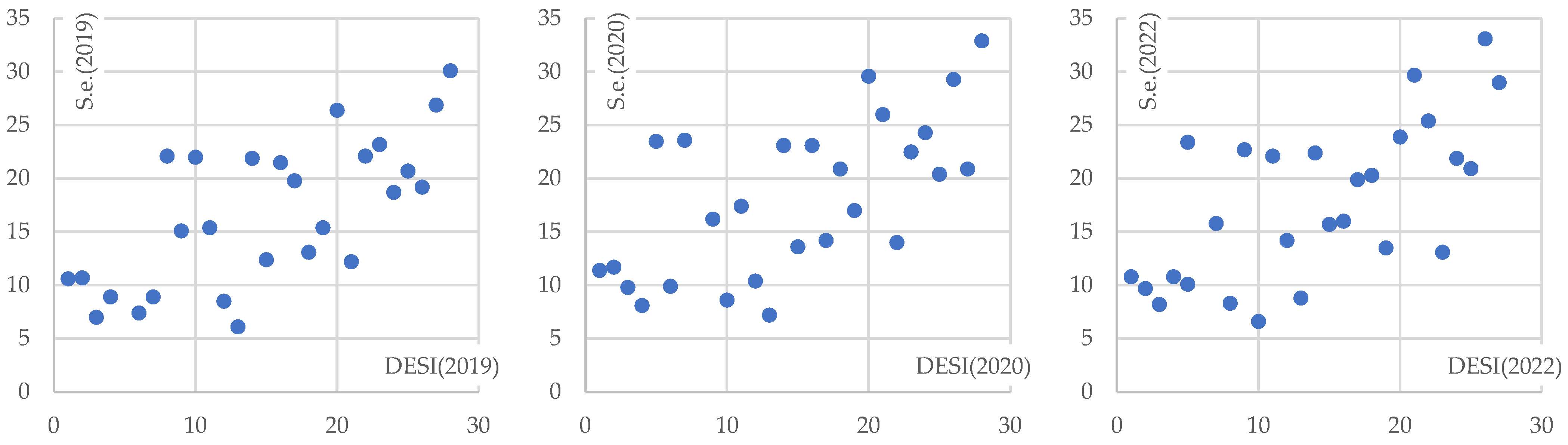

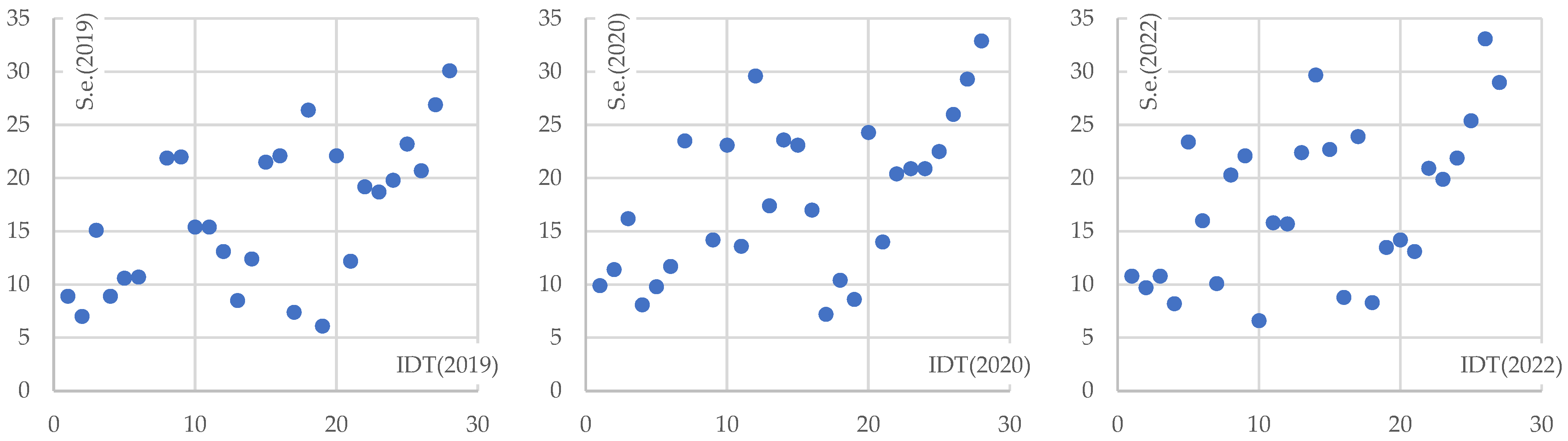

4.4. The Significance of the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) and the Integration of Digital Technology (IDT) Component

The quality of the economy, measured by the DESI, has a clear significance for the level of the shadow economy (

Figure 8). Countries ranking high on the index generally exhibit lower levels of the shadow economy, whereas countries at the lower end of the ranking typically have higher levels. This result is particularly important because the level of the shadow economy is not a component of the DESI, which implies that improving the elements included in DESI can potentially contribute to reducing the shadow economy.

The correlation between a country’s position in the DESI ranking and the level of the shadow economy in 2019 was 0.6856. It decreased slightly during the 2020 crisis to 0.6417, but by 2022 it had increased again to 0.6620.

One of the most important components of the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) is the Integration of Digital Technology (IDT). For this indicator, the relationship is also positive, meaning that higher rankings correspond to lower levels of the shadow economy. However, the correlation coefficients are lower, amounting to 0.5960, 0.5453 and 0.5155 for the respective years analyzed (

Figure 9).

The lower correlation coefficients of the IDT component compared to the overall DESI suggest that the other components are equally important. Therefore, the DESI as a whole may be the aspect most relevant for policymakers.

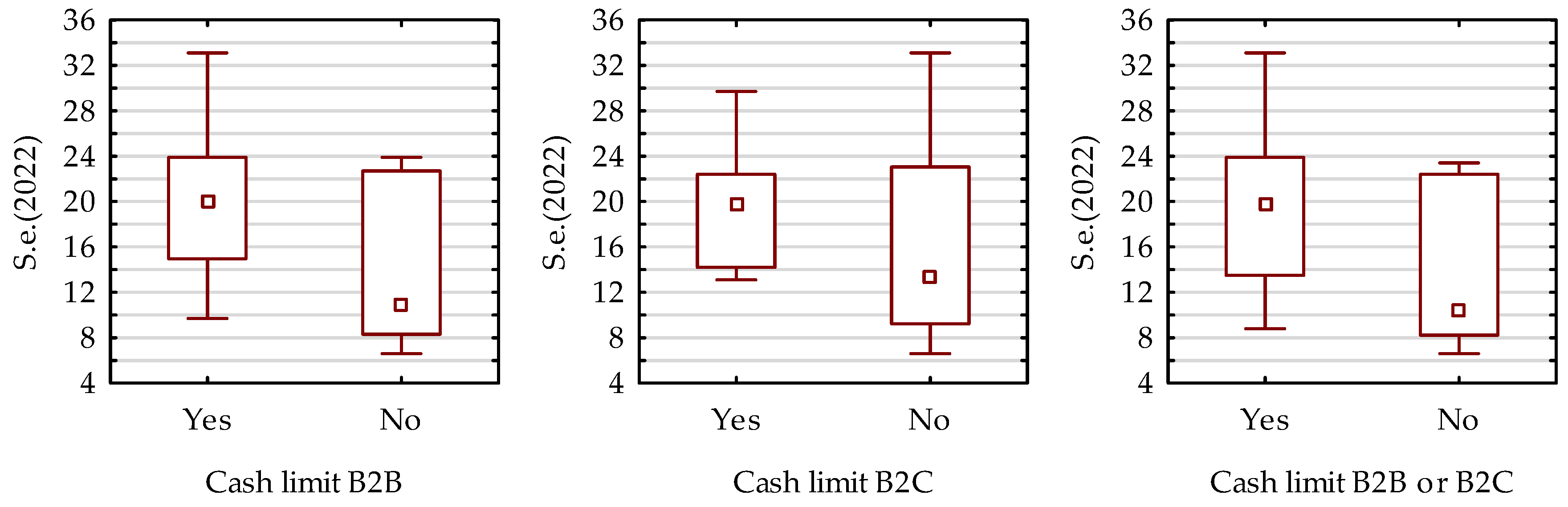

4.5. Tax System Measures

Certain barriers to entering the shadow economy can be related to tax digitalization measures (

Figure 10). Countries that implement SAF-T or E-PIT/pre-filled systems exhibit slightly lower levels of the shadow economy. The difference in median shadow economy levels amounts to approximately 4–6 percentage points, which is relatively substantial.

Another approach to combating tax evasion and consequently the shadow economy, is the limitation of cash payments. This instrument is primarily used in countries with a high level of shadow economy (

Figure 11). It cannot be claimed that the introduction of such measures contributes to an increase in the shadow economy, as in no country implementing cash payment restrictions did this result in a rise in the shadow economy.

4.6. Changes in the Level and Growth of the Shadow Economy over Time Depending on GDP and Card Payment Values

Over the examined period, there was a significant increase in the wealth of European Union countries. Observing the level of the shadow economy in relation to GDP in successive years (

Figure 12), a rightward shift in the waffle chart can be noticed. The right side of the waffle chart is consistently green, while the left side is red, indicating that countries with higher GDP generally exhibit lower levels of the shadow economy, whereas countries with lower GDP display higher levels of the shadow economy.

During the studied period, the value of card payments also increased. At the beginning of the period, it ranged from approximately 1–15% of GDP, while by the end of the period it reached about 12–80% of GDP. This represents both an increase in value and a rise in disparity between countries. However, the color distribution in the waffle charts suggests that the impact of card payment values is limited. The overall color pattern does not change significantly, although it can be observed that at higher card payment values, the level of the shadow economy is slightly lower than at lower card payment values (more yellow appears higher and red lower).

Previously, the model for card payment levels yielded a statistically significant result, but it was determined to be a spurious relationship. When GDP and card payment values are combined in a single model, only GDP proves to be significant (ratio of regression coefficient to its standard error approximately 23.7, i.e., −0.593/0.025), while the effect of card payment values is not significant (ratio of regression coefficient to its standard error approximately 0.4, i.e., −0.009/0.025). From the Ω

u matrix, it can be seen that there is considerable variation between countries in both the intercept (variance 16.759) and the regression coefficient (variance 0.047) and the correlation between the intercepts and regression coefficients is positive. This means that the higher the intercept (higher shadow economy level), the higher the GDP regression coefficient (weaker decrease in the shadow economy level). This explains the almost parallel lines of shadow economy levels observed in

Figure 1.

The regression coefficient for the effect of GDP on the shadow economy obtained in this model (

Figure 13) is −0.593. In model 1 (

Table 2), it was −0.611. The difference is negligible, indicating that whether we consider the effect of interactions between GDP, Unemployment and HICP on the shadow economy (

Table 2) or the interaction between GDP and card payment values on the shadow economy (

Figure 14), the impact of GDP is consistently significant and of similar magnitude.

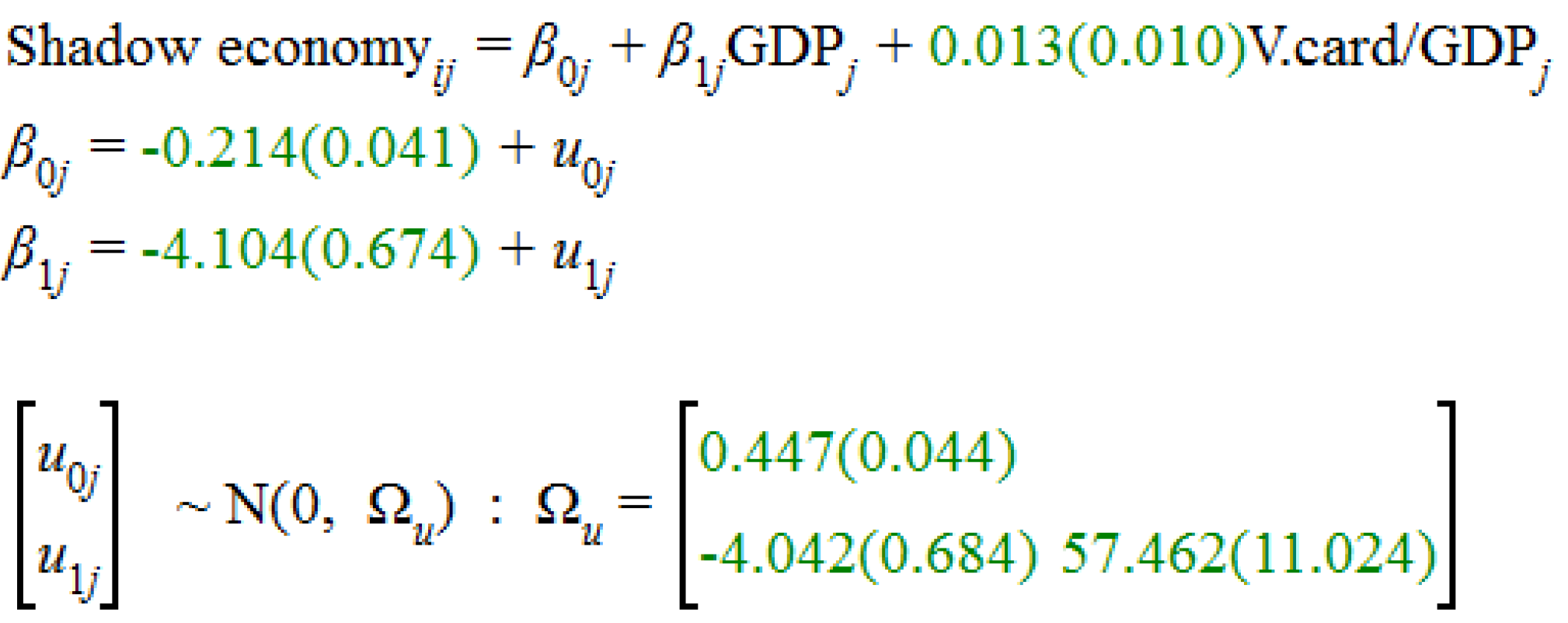

An analogous study was conducted to examine the simultaneous impact of GDP growth and growth in card payment values on the growth of the shadow economy (

Figure 14).

From the presented layout, it is difficult to draw clear conclusions regarding the effect of these increases on the shadow economy’s growth. Each year exhibits its own specific pattern: in some years, the green areas (favorable changes, decrease in the shadow economy) appear on the right side, while in others on the left, sometimes at the bottom, sometimes at the top of the chart. These variations correspond to larger or smaller increases in GDP and card payment growth.

The model-based analysis of the relationship between shadow economy growth and the growth of GDP and card payment values across all years and countries (

Figure 15) allows for the extraction of universal conclusions. It turns out that the impact of GDP growth on shadow economy growth is significant: the greater the GDP increase, the larger the decrease in the shadow economy (−4.104 with a standard error of 0.674). In contrast, the effect of the growth in card payment values is insignificant (0.013 relative to a standard error of 0.010). Additionally, the Ω

u matrix indicates that the variation in both the intercept and the GDP regression coefficient across countries is significant. Furthermore, the relationship between intercepts and regression coefficients is negative, meaning that the greater the overall rate of decline in the shadow economy, the smaller the effect of GDP changes.

The regression coefficient obtained in the model (

Figure 15) for the impact of GDP growth (d(GDP)) on the growth of the shadow economy (d(Shadow Economy)) is −4.104. In contrast, in model 1 (

Table 3), it was −3.252. The difference is not significant and regardless of the presence of other variables in the model, economic growth consistently emerges as the most important factor shaping changes in the shadow economy.

The obtained results confirm that both the level of GDP and its growth are significant in shaping the shadow economy, while other factors may play a supplementary role. The research indicates that such qualitative factors influencing the shadow economy may include DESI components or tax digitization measures, with their importance being particularly pronounced in the short term (incremental model).

5. Discussion

This study advances the existing literature on the shadow economy by addressing several research gaps that have thus far remained largely unexplored. Previous works typically examined the determinants of the shadow economy in a fragmented manner—focusing either on macroeconomic factors (such as GDP growth, unemployment, or the tax system) or on technological and institutional aspects such as digitalization or payment structures. The present article integrates these dimensions within a single empirical model covering a long time span and two major crises. The two-decade period makes it possible to capture the evolution of the shadow economy both in times of stability and under conditions of profound disruption. The inclusion of the 2008–2009 global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic allows the analysis to transcend the scope of earlier studies, which primarily focused on periods of stability or on isolated crisis episodes. Such a long time horizon enhances the reliability and practical relevance of the results obtained. By combining macroeconomic conditions, economic and social digitalization, payment innovations, and digital tax administration tools, the analysis provides a more comprehensive view of the mechanisms shaping the shadow economy in EU countries. The article introduces original indicators of tax administration digitalization, including, among others, the implementation of electronic reporting systems, pre-filled tax forms, and cash transaction restrictions. These variables—absent from most previous studies—enable a more precise assessment of the impact of technological and regulatory innovations on the scale of informal activity. In this sense, the article contributes not only new empirical evidence but also expands the methodological toolkit for future analyses.

Empirical studies on the determinants of the shadow economy in European Union countries between 2003 and 2022 allow for the formulation of several important conclusions. The analysis of research results clearly indicates that the shadow economy remains a phenomenon strongly linked to macroeconomic conditions, the level of economic development and the degree of digitalization of the economy and public administration. At the same time, the collected empirical data show that, although many factors are relevant for shaping the scale of informal economic activity, not all of them play an equally significant role. It is possible to distinguish those that are key and those that are complementary. However, even if a factor is only complementary, it may reinforce the effects of the main determinants.

The obtained empirical results confirm the widely documented relationship in the literature between the level of economic development and the scale of the shadow economy. According to the research findings, it is GDP per capita and its growth that are the most limiting factors for the informal sector. Analyses have shown that wealthier countries, with higher national income per capita, are characterized by a smaller share of the shadow economy in GDP. Economic growth in this context acts as a stabilizing factor—it enables higher wages, increases the level of consumption, strengthens the state’s capacity to provide public services and thus reduces the pressure to participate in the shadow economy. In other words, a wealthier society tends to have a stronger sense of identification with the state and is less likely to seek illegal sources of income. However, any crisis disrupts this principle: in every country, whether rich or poor, a crisis leads to an expansion of the shadow economy. Generally, in the long term, sustained and stable economic development constitutes the most effective tool for reducing the scale of the shadow economy in the European Union. This is consistent with the findings of Kelmanson et al. [

16], who indicated that rising national income, combined with improving public institutional quality, reduces the pressure to turn to informal economic activities. Similar conclusions were drawn by Kelmanson et al. [

79], who showed that stable economic growth and good governance are the most effective mechanisms for the long-term reduction of the shadow economy. Schneider and Medina [

23] also confirmed that differences in economic development explain a large part of the variation in the size of the shadow economy between EU countries. Thus, the primary factor limiting the size of the shadow economy is GDP per capita and its growth.

While not as influential as GDP, labor markets also play an important role in limiting the shadow economy. Higher wages and household consumption reduce the attractiveness of informal activities, whereas rising unemployment promotes their expansion. These findings align with the results of Sahnoun and Abdennadher [

48], who showed that an increase in the unemployment rate leads to a growth of the shadow economy in both developed and developing countries. This provides further evidence that, regardless of the level of economic development, economic difficulties always result in the expansion of the shadow economy, which can be considered rational. This rationality is reflected in the fact that during difficult periods, businesses and individuals seek various solutions to secure their livelihood and sometimes entering the shadow economy becomes such a solution. Analyses indicate that both the global financial crisis of 2009 and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 caused a marked increase in the share of the shadow economy in GDP. In particular, the economic freeze during the COVID-19 pandemic and the restrictions on the functioning of many sectors led to a rapid expansion of informal forms of activity. These findings suggest that the shadow economy serves as a “buffer” in times of economic downturn, acting as a form of societal adaptation to sudden income losses and labor market difficulties. The study conducted in this work shows that the pandemic crisis had an even stronger effect than the financial crisis, which is also confirmed in the literature. Lago-Peñas [

80] demonstrated that the pandemic increased the scale of the shadow economy more than previous recessions and additionally shifted some activity from cash to cashless transactions, while Schneider [

81] showed that recovery from this period is very slow, which is also confirmed in this study.

An interesting aspect of the study is the role of cashless payments. Although the research results indicated that the effect of card payments appears to be secondary, the literature suggests a more complex picture. The work of Hondroyiannis and Papaoikonomou [

82] demonstrated that an increase in the number of card transactions in Greece and the euro area led to a significant rise in VAT revenues, suggesting that recordable transactions hinder the functioning of the shadow economy. Similarly, Bohne, Koumpias and Tassi [

83], using EU data, indicated that a higher share of cashless payments reduces the VAT gap and thereby limits the scale of the shadow economy. Research by Madzharova [

84] also confirms that an increasing share of traceable transactions improves the efficiency of VAT collection. Thus, although in the present analysis the effect of card payments was considered secondary to economic development, the literature shows that this instrument can significantly support the fight against the shadow economy—especially when combined with appropriate fiscal policy. However, the literature does not fully clarify these relationships in the context of economic development. Conclusions based on the literature are rather indirect, indicating the long-term influence of cashless transactions on the shadow economy, rather than short-term impulses. It seems more accurate to suggest that the growth of cashless payments correlates with the reduction in the shadow economy primarily because it reflects the increasing wealth of societies. In other words, card payments alone are not sufficient to curb informal economic activity—only in combination with economic development and administrative digitalization can they become part of an effective strategy.

A clearer confirmation was found in the research results regarding the digitalization of the economy and public administration. The DESI and its components (IDT) show a strong correlation with a lower share of the shadow economy. This finding is consistent with studies indicating that the digitalization of tax administration—through e-invoices, automated reporting, cash restrictions and online cash registers—increases transaction transparency and reduces opportunities for tax evasion [

61,

64,

85]. A review of the literature in this area clearly demonstrates that digitalization is one of the most effective tools in combating the shadow economy and its effects are particularly strong in countries with low levels of corruption [

60]. In general, countries with a higher level of digitalization report a lower share of the shadow economy in GDP. This phenomenon can be explained by greater transparency of economic processes, automated reporting and the growing importance of e-commerce, which reduce the possibilities for hiding transactions. Moreover, digitalization of public administration—including the introduction of tools such as SAF-T, e-invoices, or pre-filled income tax returns—supports the reduction of informal economic activity by limiting opportunities for tax avoidance. The research results therefore confirm that digitalization is one of the key instruments supporting the fight against the shadow economy.

The last, yet extremely important, aspect is restrictions on cash transactions. Literature findings indicate that countries implementing limits on cash payments in B2B and B2C transactions tend to have a lower level of the shadow economy. This phenomenon is confirmed by the research of Reimers et al. [

86], who showed that an increase in cash in circulation expands the size of the shadow economy, while limiting the maximum value of cash transactions reduces it. Similarly, the study by Giammatteo et al. [

87] indicates that higher cash usage is associated with a larger share of the shadow economy. However, an analysis of data from 2022 showed that countries applying cash limits in B2B and B2C transactions actually had a higher level of the shadow economy. This can be assumed to result from the restrictions imposed by countries with higher levels of the shadow economy in an effort to reduce it. Implementing cash payment limits is a very straightforward tool, which explains why it became more widely used in such countries in 2022. These countries likely expect a future positive effect in the form of a reduction in the shadow economy. Thus, this observation is not inconsistent with previous research but rather reflects the practical application of research findings in countries with higher levels of the shadow economy.

The article situates the issue of the shadow economy within the broader context of sustainable development. Rather than treating informality solely as a fiscal challenge, the study emphasizes its implications for the stability of public finances and the attainment of long-term development goals. This shift in focus embeds the analysis within the global debate on the SDGs, linking the economic perspective with the institutional and social foundations of inclusive growth.

6. Conclusions

The shadow economy, defined as the sphere of economic activity that remains outside official state records, constitutes a complex and multidimensional phenomenon influencing both the functioning of the national economy and the social landscape. The analysis presented in this study demonstrates that the causes of the shadow economy’s development are diverse, encompassing economic, social, political and cultural factors. The consequences of its existence may be categorized as both positive and negative, although the overall balance should be assessed critically. On the one hand, the shadow economy can serve as a “safety valve” for the economy—enabling unemployed or marginalized individuals to engage in income-generating activity, providing households with supplementary earnings and allowing many entities to maintain liquidity under conditions of excessive fiscal burdens. On the other hand, the macroeconomic repercussions are significant: reduced tax revenues constrain the state’s investment capacity, hinder the financing of public services and deepen the budget deficit. Moreover, the illicit nature of such activities fosters unfair competition, impedes innovation, discourages legal employment and perpetuates structural pathologies in socio-economic relations.

A comparative analysis of the data indicates that the size of the shadow economy varies across countries depending on the level of economic development, the efficiency of public institutions and the quality of fiscal policy. Countries with stable and transparent tax systems, a high level of social trust and effective law enforcement are characterized by a significantly lower share of the shadow economy in GDP. By contrast, in less developed states, the share of the shadow economy may reach several dozen percent of total economic activity. It is worth emphasizing that this refers to countries belonging to the European Union, which requires its member economies to strictly adhere to legal frameworks. The findings are broadly consistent with the existing literature. While the shadow economy is shaped by multiple factors, the key determinants are the level of economic development, labor market stability and the degree of digitalization of both society and public administration (hypotheses H1, H2 and H4 were confirmed). Non-cash payments and restrictions on cash transactions, although not capable of eliminating the shadow economy on their own, serve as effective complements to economic policy (hypothesis H3 was only partially confirmed). In the long run, the most important conclusion is that only the combination of stable economic growth with the development of digital fiscal control tools can effectively reduce the size of the informal economy in EU member states.

In light of the conducted research, it can be concluded that the strategy for reducing the informal economy should be based on a dual-track approach. On the one hand, it is crucial to ensure the conditions for sustained and stable economic growth, which in itself constitutes the most effective mechanism for reducing the shadow economy. On the other hand, it is essential to implement modern digital tools in public administration, expand e-government services, promote cashless payments and consistently restrict cash transactions. Only such a comprehensive set of measures can, in the long term, effectively reduce the share of the shadow economy in GDP and strengthen the foundations of economic stability within the European Union (hypothesis H5 was confirmed).

From a sustainable development perspective, the results yield three key implications:

- (i)

Economic formalization through sustained growth and macroeconomic stabilization expands the fiscal base necessary to finance public goods and services (education, healthcare, infrastructure, adaptive investments), directly supporting the achievement of SDG targets related to economic growth and decent work, inequality reduction, and the state’s financial capacity to pursue environmental objectives;

- (ii)

The digitalization of administration and payments enhances transaction transparency and improves tax collection, thereby strengthening public institutions and their ability to manage public finances over the long term;

- (iii)

The shadow economy’s procyclical response to crises—expanding during periods of economic shutdown—indicates the need to combine formalization policies with social protection and labour market activation measures. Without such integration, formalization efforts may prove fragile and short-lived, particularly in countries with weaker institutions.

From a public policy perspective, the recommendations derived from the findings are as follows:

- (i)

Pro-growth and fiscal policies should be accompanied by investments in digital administrative infrastructure—promotional efforts focused solely on cashless payments are insufficient;

- (ii)

When implementing digital tools (e-invoicing, SAF-T, pre-filled forms, online cash registers), governance standards must be raised simultaneously (anti-corruption measures, simplification of tax law, staff training) to ensure that technology functions as an effective instrument rather than merely a formal solution;

- (iii)

Cash-limitation policies should account for the risk of financial exclusion and be coordinated with inclusive programmes (access to bank accounts, financial education);

- (iv)

In times of crisis, automatic income support mechanisms and labour activation programmes are essential to reduce the pressure to shift towards informal sources of livelihood.

Such an integrated approach increases the likelihood that formalization will be durable and aligned with the SDGs.