1. Introduction

The redevelopment of large-scale idle military sites has become a central issue in contemporary urban regeneration, as cities worldwide seek to transform surplus land into sustainable assets that advance cultural, economic, and ecological objectives [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In Korea, these challenges are intensified by rapid urbanization, demographic decline, and the persistence of military installations within the urban fabric. The relocation of the K-2 Airbase in Daegu represents one of the nation’s most critical opportunities for transformation.

Daegu, once an industrial hub with strong textile, machinery, and medical clusters, has faced structural decline, youth outmigration, and limited cultural visibility compared to Seoul and Busan [

5,

6]. These dynamics highlight the urgent need for redevelopment strategies that extend beyond conventional brownfield regeneration to address questions of competitiveness, identity, and livability. Daegu’s geographical advantages—its position in the southeastern economic belt, proximity to the planned new airport, and potential integration into national innovation corridors—present unique opportunities to reposition the city within both domestic and global networks [

7,

8,

9].

Accordingly, the redevelopment of the K-2 site should be framed not as a mere exercise in land reuse but as a strategic intervention that aligns ecological restoration with cultural, educational, and industrial revitalization. This approach positions the project as a catalyst for reimagining Daegu’s role in Korea’s urban hierarchy and enhancing its global competitiveness.

1.1. Background and Objectives of the Design

The relocation of the Daegu K-2 Airbase has created one of the largest urban voids in Korea, producing a 7 km

2 site adjacent to the city center. While this transformation threatens continuity in Daegu’s spatial structure, it also provides an unprecedented opportunity to reimagine the city’s future trajectory [

10]. The site’s location, infrastructure, and linkages with the integrated new airport situate it as a national and regional asset. However, redevelopment also raises complex issues, including soil remediation, financing, governance, and social consensus [

11,

12]. International cases such as Munich-Riem in Germany, Tempelhof in Berlin, Toronto’s brownfield redevelopments, and Stapleton in Denver illustrate how military and industrial lands can be transformed into vibrant urban districts [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Concurrently, they highlight recurring barriers, including high remediation costs, conflicts among stakeholders, and the need for long-term governance [

2,

4].

Against this backdrop, the objectives of this study are twofold. First, it conceptualizes the “Global Contents City” as a sustainable regeneration model that embeds cultural exchange, creative industries, education, and tourism into a comprehensive planning framework [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Unlike conventional redevelopment approaches that emphasize housing or commercial functions, this model positions cultural and educational infrastructures as drivers of urban identity and competitiveness. Second, the study critically examines the transferability of lessons from global precedents to the Korean context, identifying opportunities and limitations in applying international experiences to Daegu [

7,

13]. These objectives underscore the dual contribution of the research: expanding academic discourse on sustainable post-military regeneration and providing a masterplanning vision that aligns with Daegu’s global aspirations [

10,

13].

1.2. Design Scope and Methods

The scope of this study is defined across spatial, temporal, and thematic dimensions. Spatially, it focuses on the former K-2 Airbase in Daegu, covering approximately 7 km

2 adjacent to the city center [

10]. This scale enables the integration of diverse urban functions, from residential and industrial uses to cultural, ecological, and educational facilities [

14]. Temporally, the study adopts a long-term perspective, addressing immediate redevelopment challenges such as remediation and infrastructure, while envisioning sustainable management, resilience, and urban identity for future decades [

11]. Thematically, it emphasizes four interlinked axes: cultural exchange, creative industries, education, and tourism, all supported by ecological restoration and low-carbon infrastructure [

9,

12,

15,

16,

17].

Methodologically, the study employs a qualitative framework integrating three approaches. First, a theoretical review situates the study within discourses on brownfield regeneration, cultural cities, and post-military site redevelopment [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Second, a comparative case analysis investigates international precedents—Munich-Riem, Tempelhof, Toronto, and Stapleton—to derive lessons that can be transferred to the Korean context [

1,

2,

3]. Third, a design-oriented exploration translates these conceptual insights into masterplanning strategies for the K-2 site [

10]. Although primarily conceptual, the research also acknowledges the importance of future empirical validation through GIS-based simulations, environmental performance assessments, and stakeholder engagement [

12]. By combining these methods, the study aims to contribute to academic debates on sustainable city-making while offering practical guidance for policymakers and urban designers addressing large-scale military site redevelopment.

While the study is primarily conceptual and design-oriented, indicative parameters were also considered to reinforce methodological rigor. In particular, basic metrics such as accessibility from the site to major urban nodes, the baseline and target ratio of green coverage, and a preliminary balance between projected residents and employment opportunities were qualitatively reviewed. These elements, though not fully quantified, provided a reference frame for structuring the Global Contents City masterplan. The study also acknowledges the need for further empirical research, including GIS-based simulations, environmental performance assessments, and structured stakeholder engagement, to validate and operationalize the proposed strategies in future work [

12].

4. Design Strategies for the Global Contents City

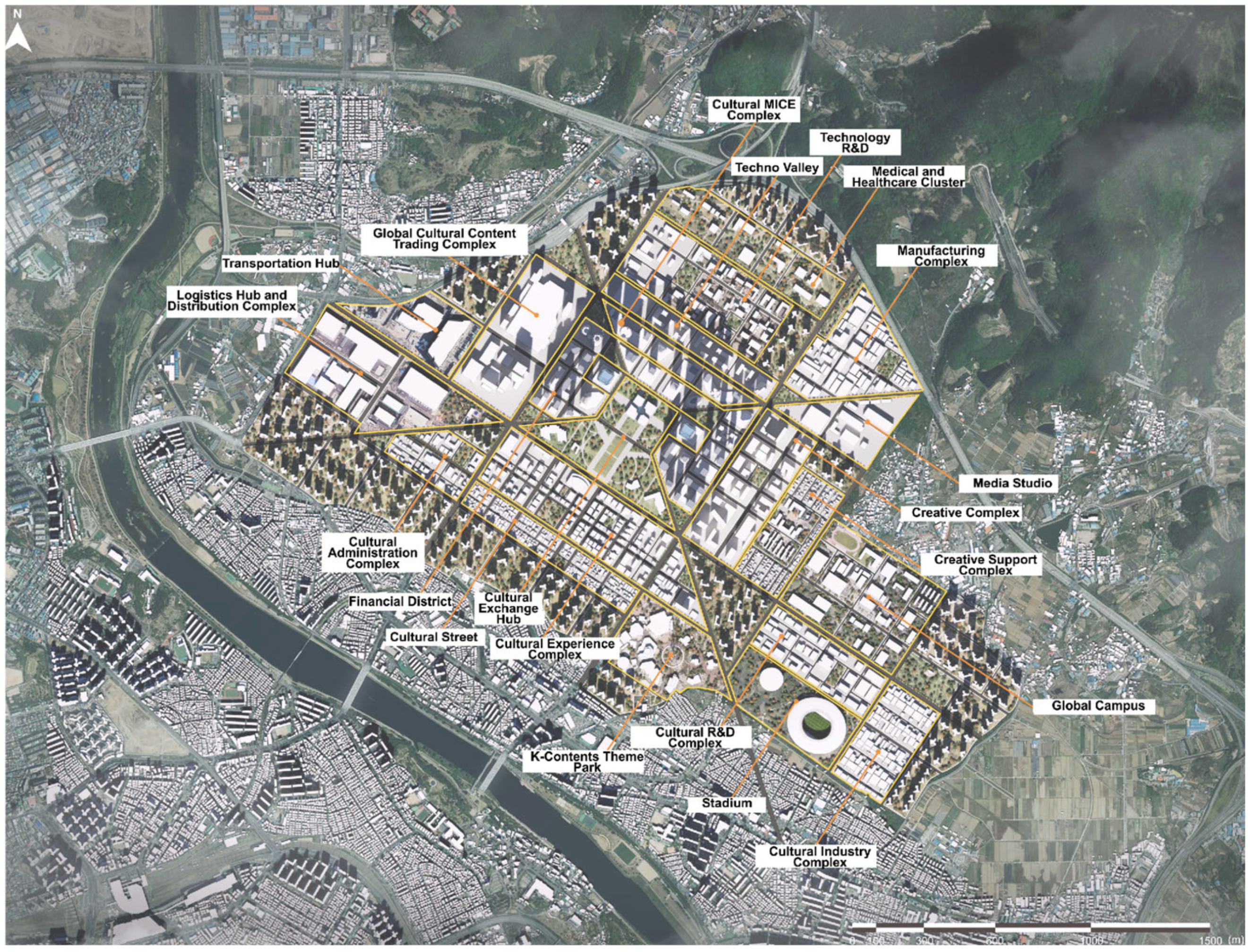

4.1. Zoning

The zoning framework of the Global Contents City is conceived as a strategic mechanism for spatializing the project’s core vision, namely the integration of international exchange, education, industry, and tourism. At the center, the International Exchange Hub is positioned as a symbolic axis that concentrates global cultural activities and international events, thereby anchoring the overall urban structure [

9,

10,

15,

16]. To the north, the Technology Zone is linked with Sinseo Innovation City and hosts clusters in advanced industry and healthcare, serving as a growth driver connected to global knowledge industries [

7,

14]. To the east, the Creative Zone is designed as a knowledge and creative cluster in collaboration with nearby universities, supporting both the cultivation of global talent and the production of cultural contents [

15,

16]. The Tourist Zone to the south integrates Daegu’s cultural and tourism resources, accommodating experiential culture and international tourism; within this context, performances, exhibitions, and experiential programs related to K-Culture are incorporated to strengthen the city’s global brand [

13,

17]. To the west, the Urban Logistics Zone is directly connected to the highway interchange and metropolitan transport networks, providing the physical foundation for industrial activity and international exchange (

Figure 1) [

11].

This four-directional zoning structure interlinks the central hub with specialized districts, forming an integrated urban ecosystem in which international cultural exchange, creative education, industrial innovation, and tourism are mutually reinforcing. Within this framework, the cultural and tourism sectors combine local resources with K-Culture to generate a distinctive urban identity, while the education and research sectors embed these resources within processes of creation and learning to enhance long-term sustainability. Rather than being confined to any single function, K-Culture is interwoven across exchange, education, industry, and tourism, thereby establishing a foundation for the city’s sustained expansion within global cultural networks [

12,

19].

In this regard, this zoning strategy reflects the principles of polycentric urbanism, balancing specialized functions across districts while fostering systemic resilience in socio-economic and environmental dimensions [

15,

16].

4.2. Urban Road Network

The road network of the Global Contents City is planned as a core infrastructure that organically integrates international exchange, education, industry, and tourism, functioning as a critical device for materializing the city’s vision in spatial terms [

4]. Radiating from the central International Exchange Hub, the primary arterial roads extend northward to the Technology Zone, eastward to the Creative Zone, southward to the Tourist Zone, and westward to the Urban Logistics Zone, ensuring that each functional axis directly connects to the city’s core values [

7]. In particular, the western transport corridor is strategically linked to the Palgong Interchange, which connects directly to the regional expressway system. This enhances metropolitan accessibility and provides a robust foundation not only for logistics but also for accommodating large-scale international events and tourism flows [

10,

15]. Accordingly, arterial roads function not merely as transport routes but as conduits for the international diffusion of industry, education, culture, tourism, and logistics (

Figure 2).

Secondary arterial roads complement these primary corridors by facilitating inter-district interaction and enabling the cyclical diffusion of exchange, learning, creation, and consumption across the city. This structure ensures that cultural and industrial activities are not confined to isolated districts but are disseminated citywide, with educational, research, and industrial functions intersecting to reinforce overall urban vitality.

Collector roads connect neighborhood-scale living zones and are integrated with pedestrian and bicycle networks, providing a foundation for the coexistence of international events and everyday activities. Such a configuration creates conditions under which festivals and large-scale events coexist with daily cultural experiences, allowing both residents and visitors to engage in cultural exchange as part of ordinary urban life.

Taken together, the road network of the Global Contents City opens up multilayered arenas for international cultural exchange and continuously activates an urban ecosystem in which education, industry, and tourism operate synergistically. Furthermore, when combined with digital communication infrastructures, the physical road system evolves beyond a mechanism of movement to become a strategic foundation for the global diffusion of culture and industry. Within this process, K-Culture operates as a catalytic element that links local resources with global cultural flows, reinforcing the city’s international identity [

9,

16].

In addition, the road system incorporates a hierarchical street typology, ranging from arterial to local roads, which ensures functional differentiation and accessibility at multiple scales. Arterial roads provide metropolitan connectivity and support large-scale flows, while collector and local roads prioritize pedestrian comfort and neighborhood-level mobility. This hierarchy not only enhances circulation efficiency but also aligns with sustainability goals by promoting walkability and multimodal integration within the overall transport framework.

Accordingly, beyond physical connectivity, the road system embodies the concept of sustainable mobility, enabling the diffusion of cultural, industrial, and educational functions while minimizing ecological impact [

11,

19].

4.3. District Unit Plan

The District Unit Plan of the Global Contents City is structured in a radial configuration, with the central Cultural Exchange District serving as the focal point and specialized functions distributed to the north, east, south, and west. The Cultural Exchange District accommodates international exhibitions, performances, and events, acting as a symbolic hub that connects to global networks and provides a stage for diverse cultural contents, including K-Culture, to engage in international exchange [

13,

17].

The northern Technology and Healthcare District is linked to the Sinseo Innovation City, driving the growth of advanced industries and the bio-medical sector. By integrating digital technologies with cultural content, this district expands the potential for next-generation industrial development [

14]. To the east, the Creative and Educational Research District establishes a knowledge and creativity cluster connected to local universities, forming a global learning ecosystem through international education centers and creative talent cultivation hubs [

15,

19].

The southern Cultural, Experiential, and Tourism District connects Daegu’s cultural resources with broader tourism networks, providing a concentrated venue for performances and festivals. Here, K-Culture is integrated with local cultural assets, establishing a foundation for absorbing international tourism demand [

9]. Meanwhile, the western Transportation and Logistics District is directly connected to metropolitan transportation systems, supporting the physical infrastructure necessary for global exchange and industrial activity, while also facilitating the international distribution of cultural industry-related content and products (

Figure 3) [

11].

Collectively, this plan establishes an integrated structure in which each specialized district is organically connected around the Cultural Exchange District, creating an urban ecosystem where exchange, education, industry, and tourism operate in a mutually reinforcing manner. Within this process, K-Culture functions as a catalyst—particularly in the central and southern districts—by combining with other functions to enable the city’s sustained expansion within global cultural networks [

12,

16].

Thus, by integrating cultural, technological, educational, and tourism functions, this district structure aligns with the sustainable city paradigm, ensuring that diverse urban activities reinforce one another in a resilient ecosystem [

9,

10,

19].

4.4. Green Open Space

The green and open space framework of the Global Contents City is conceived as the ecological foundation that integrates international exchange, education, industry, and tourism. At the core, a central plaza is designed to accommodate international events and multicultural festivals, serving as both a symbolic and functional space for global interaction [

12]. On the eastern side, campus-style green areas are introduced to support learning and creative activities, fostering an environment conducive to knowledge production and cultural innovation [

10,

15].

In the southern district, experiential parks and outdoor performance venues are strategically located to connect with tourism resources, thereby enhancing cultural consumption and visitor engagement. On the western edge, buffer green zones are established to mediate between logistics functions and residential environments, ensuring a balance between economic activity and quality of life (

Figure 4) [

4].

Collectively, these spatial strategies generate a sustainable urban environment where international exchange intersects with everyday activities. By integrating green and open spaces into the city’s cultural and functional fabric, the plan not only supports ecological resilience but also reinforces the inclusivity and livability essential to a globally connected cultural city [

16,

19]. These strategies directly advance environmental sustainability by expanding ecological coverage from baseline conditions, incorporating soil and groundwater remediation, and embedding low-carbon infrastructure as measurable indicators of ecological resilience [

12]. Building upon this ecological foundation, the open space strategy also incorporates brownfield remediation measures, thereby ensuring that environmental risks are addressed as a prerequisite for redevelopment.

Accordingly, the green and open space framework exemplifies the application of ecosystem service theory, ensuring that cultural and economic activities are grounded in ecological resilience and long-term sustainability [

12]. Building upon this ecological foundation, the open space strategy also incorporates brownfield remediation measures, including soil restoration, groundwater treatment, and low-carbon ecological infrastructure, thereby ensuring that environmental risks are addressed as a prerequisite for redevelopment [

3,

11].

4.5. Land Use

The land use strategy of the Global Contents City is designed to realize a complex urban ecosystem in which international exchange, cultural industries, education and research, tourism, and logistics are organically interconnected. At the core, a Cultural Exchange Hub and a Cultural MICE (Meetings, Incentives, Conventions, and Exhibitions) district are located to host international exhibitions, conferences, and festivals, thereby functioning as symbolic anchors that articulate the identity of the city [

9,

17]. This central area also serves as a space that accommodates a wide spectrum of global cultural contents—including K-Culture—providing a multi-layered platform where international events coexist with local cultural activities [

13].

Surrounding this hub, a cluster of cultural industry complexes, cultural R&D centers, K-Content theme parks, and cultural experience districts are strategically integrated to form a cyclical structure of production, experimentation, exhibition, and consumption [

9]. This configuration not only encompasses K-Culture’s creation, experience, and consumption but also aspires to foster a balanced ecosystem that accommodates the growth of diverse cultural industries [

14].

The northern district is structured around technology R&D, technovalley functions, and medical–healthcare clusters, in connection with the Sinseo Innovation City, thereby establishing an advanced industrial cluster that enables global technology exchange and the development of bio–healthcare industries [

14]. Within this process, digital technology and the media industry are naturally aligned with the global dissemination of K-Culture content. The eastern district concentrates global campuses, creative clusters, creative support facilities, and media studios to form an international hub where education, research, and creative production converge. This area supports cultural and artistic education programs—including K-Culture—as well as collaborative research initiatives, fostering creative talent and enabling global partnerships [

15,

19].

The southern district incorporates a cultural street, sports centers, and cultural administration facilities, providing inclusive public cultural experience spaces for both citizens and visitors, while reinforcing Daegu’s urban brand through direct linkage with the city’s tourism resources. This zone has strong potential to evolve into a destination where K-Culture performances and experiential programs are closely integrated with tourism initiatives. The western district is anchored by transportation hubs, logistics centers, and financial complexes, which consolidate regional transportation and commercial–logistics functions, strengthening the networks of global business and distribution. These infrastructures further promote the international circulation of cultural contents and products, including K-Culture (

Figure 5).

Taken together, this land use structure spatializes the core values of the Global Contents City—cultural exchange, creative education, industrial innovation, tourism activation, and logistics integration—into a balanced urban framework. In this process, K-Culture does not remain confined to a single functional area but acts as a catalyst that interlinks various districts, thereby amplifying the city’s cultural attractiveness and positioning it within global networks.

Consequently, the land use strategy embodies the logic of circular urbanism, interlinking cultural creation, education, industry, and tourism in a cyclical system of production and consumption [

16,

19].

To secure implementability, the framework anticipates a governance structure combining national–local leadership with PPP arrangements. Land-value capture mechanisms and cultural industry investment funds are proposed as financing tools to support long-term sustainability. The project’s viability relies not only on institutional leadership but also on the active involvement of diverse stakeholders. Residents, local communities, and businesses are to be engaged through participatory planning workshops, community consultations, and business forums, ensuring that decisions reflect multiple perspectives. Embedding transparent communication mechanisms helps build trust, mitigate conflict, and align stakeholder expectations, thereby reinforcing both the legitimacy and resilience of the redevelopment process.

4.6. Facility Layout Plan

The facility layout plan emphasizes an integrated spatial organization rather than isolated clusters, fostering synergies consistent with principles of adaptive and sustainable urban design [

9,

10]. The arrangement establishes functional linkages across cultural, educational, industrial, and residential districts, ensuring balanced interactions within the Global Contents City.

To secure feasibility, development is structured in three phases. Phase 1 delivers an eco-park and foundational infrastructure, prioritizing site remediation, soil restoration, and green corridors to expand ecological coverage. Phase 2 activates cultural and educational facilities, with programmatic hubs that strengthen accessibility to Daegu’s urban core, the new airport, and surrounding industrial and educational clusters within 20–30 min. Phase 3 consolidates residential–industrial clusters with the aim of achieving a balanced jobs–housing structure. This phase emphasizes the integration of cultural industries, education, and service-sector employment to reinforce everyday livability and urban vitality (

Figure 6).

This phased strategy provides a structured pathway for implementation, aligning program activation with infrastructural readiness and demand triggers. It also enhances resilience by sequencing ecological restoration, cultural activation, and socio-economic consolidation in a cumulative process of urban transformation.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that the redevelopment of large-scale idle military sites should not be treated merely as physical land reuse but rather as the creation of integrated urban ecosystems. The Global Contents City framework interlinks cultural, educational, industrial, and ecological functions, demonstrating how post-military land can be repositioned as a driver of regional competitiveness and global connectivity. This aligns with international precedents such as Munich-Riem and Stapleton, where ecological restoration and mixed-use communities were prioritized, yet it confirms a distinct trajectory in the Korean context by positioning cultural content industries as a central pillar of regeneration.

The comparative analysis further shows that while some international cases emphasize ecological remediation (Toronto) or civic participation (Tempelhof), the Daegu K-2 project foregrounds cultural exchange and global branding. Related experiences in East Asian cities—as discussed in

Section 3—highlight that regeneration lessons must be contextually adapted rather than replicated wholesale. This confirms that the Global Contents City contributes both as a planning vision and as a cultural strategy, reinforcing sustainable urbanism and positioning Daegu within global cultural flows.

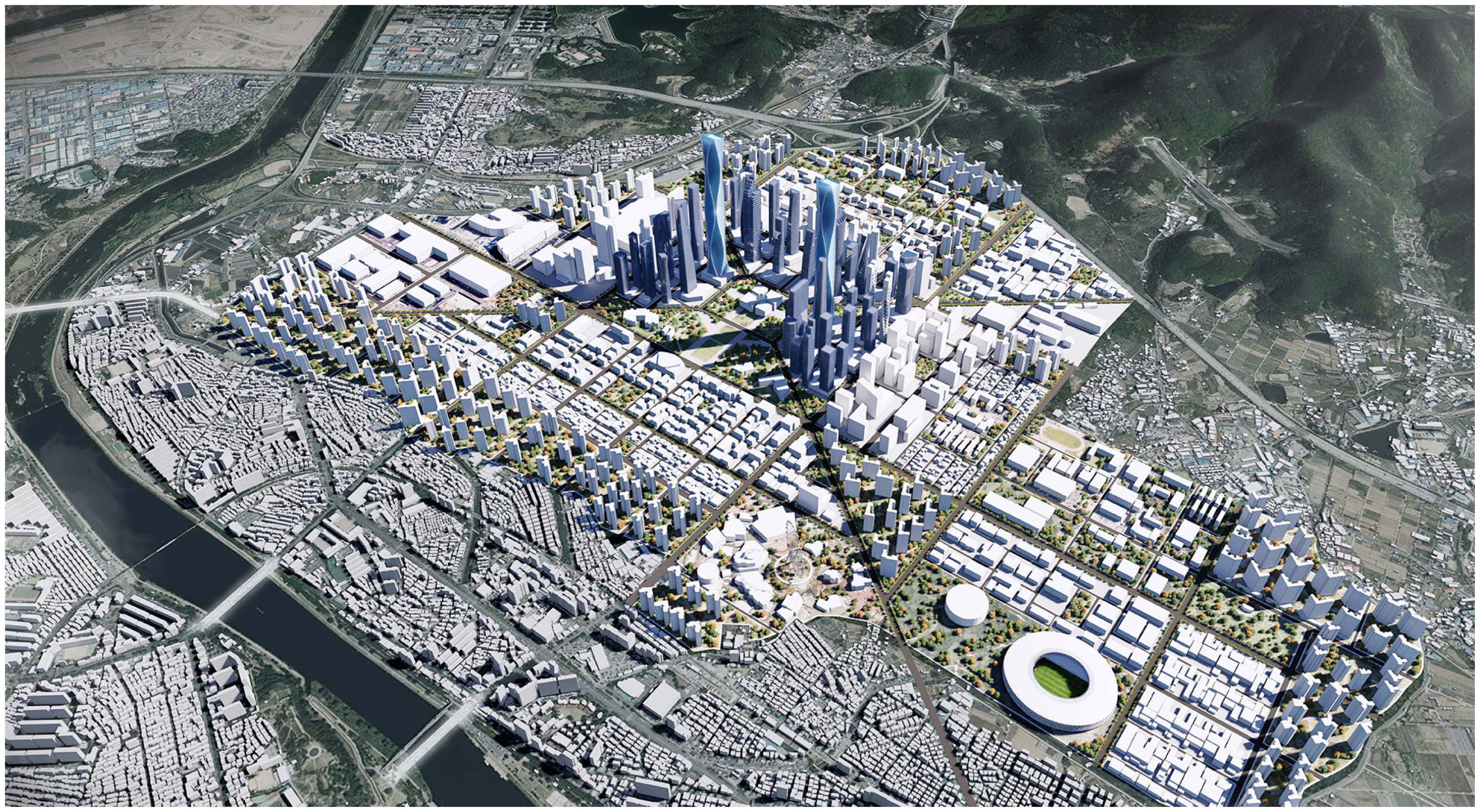

This vision is substantiated through the Master Plan of the Sustainable Global Contents City (

Figure 7), which illustrates the integration of cultural, educational, industrial, and ecological zones in a comprehensive satellite-view layout. In addition, the bird’s-eye perspective (

Figure 8) visualizes the proposed urban environment at the human scale, demonstrating how the conceptual framework translates into tangible urban form that emphasizes connectivity, inclusivity, and ecological resilience.

The phased development strategy further anchors the vision to measurable milestones. Phase 1 delivers an eco-park and essential infrastructure, raising ecological coverage from the current 12% baseline to at least 20% and ensuring site readiness through remediation and green corridors. Phase 2 activates cultural and educational facilities, improving accessibility by enabling 20–30 min connections to Daegu’s urban core, the new airport, and regional clusters. Phase 3 consolidates residential–industrial clusters, aiming to approximate a balanced jobs–housing ratio supported by employment in cultural industries, education, and service sectors. Collectively, these phases provide a cumulative pathway toward competitiveness and resilience.

The analysis confirms that successful implementation cannot rely solely on physical planning and financing mechanisms. Active participation by local communities, residents, and businesses is essential. Embedding communication platforms—such as participatory workshops, community consultations, and business forums—ensures balanced interests, mitigates conflict, and enhances legitimacy. Stakeholder engagement therefore functions not only as a governance mechanism but also as a social sustainability strategy, reinforcing inclusiveness and long-term ownership of the redevelopment process.

In conclusion, this research proposes the Global Contents City as a sustainable urban regeneration model for the redevelopment of the Daegu K-2 military airbase. By situating the case within international discourse, it confirms that large-scale idle military land can be transformed into a strategic urban asset that integrates cultural, industrial, educational, and ecological dimensions. The study contributes to scholarly debates by demonstrating cultural industries as a distinctive driver of regeneration in the East Asian context.

The framework also anchors its vision to sustainability targets across three dimensions. Environmentally, it prioritizes ecological restoration through soil remediation, groundwater treatment, and the expansion of green coverage from a 12% baseline to at least 20%. Socially, it emphasizes inclusiveness by embedding educational hubs, international exchange facilities, civic cultural spaces, and stakeholder participation platforms that foster broad engagement and strengthen community identity. Economically, it underscores long-term competitiveness through job creation, industrial diversification, and innovative financing. Beyond immediate employment and service activation, fiscal growth is projected through expanded tax bases derived from cultural tourism, creative industries, and knowledge-intensive sectors. To secure financial sustainability, mechanisms such as land-value capture, cultural industry investment funds, and PPP-based governance are proposed. These frameworks are envisioned to function through diversified funding sources, transparent profit-sharing, and distributed risk-management strategies, ensuring resilient and reinvestable revenue streams.

Nevertheless, this study remains conceptual in nature. While the framework draws on international precedents and indicative parameters to support feasibility, it does not yet incorporate field-based research such as questionnaires, interviews, or direct observation. Future research should therefore provide empirical validation through accessibility modeling, environmental performance assessments, socio-economic impact studies, and participatory workshops. In addition, potential obstacles such as financial constraints, political resistance, and technical challenges are acknowledged as critical issues that require deeper empirical investigation to provide practical guidance for implementation.