1. Introduction

In recent decades, higher education has been globally recognized as a pivotal engine of sustainable development. The United Nations’ 2030 Agenda identifies quality education (SDG 4) as central to building societies that are economically vibrant, socially inclusive, and environmentally resilient [

1,

2]. Yet recent monitoring shows uneven progress toward SDG 4, with widening gaps both between and within countries [

3]. Higher education acts as a catalyst—driving innovation, nurturing human capital, and supporting nearly every other SDG through research, leadership, and community engagement [

4,

5]. However, its role is double-edged sword: while it offers immense potential for progress, uneven spatial distribution can reinforce existing inequalities, undermining the sustainability it is meant to foster. The geography of higher education remains highly unequal, posing a critical challenge to global equity and sustainability [

6].

Disparities in access, quality, and resources persist across various scales—globally and within nations. In global higher education systems, scholars have identified center-periphery divides (e.g., Ben-David’s comparative study of Britain, France, Germany, and the United States) [

7]. Differences between Eastern and Western traditions [

8], as well as between the Global North and South, have also been highlighted [

9]. At the national level, research often shifts focus to domestic systems because higher education quality not only affects sustainable development but is also crucial for national competitiveness in a globalizing world. This issue is especially acute in large, diverse countries like China and India. Profound economic and geographic disparities have produced deep spatial divides [

10]. While regional variation may reflect functional specialization, excessive divergence erodes social cohesion, distorts the allocation of human capital, and weakens coordinated responses to common challenges such as climate change and economic restructuring [

11]. For sustainable development to be achieved, such gaps must remain within functional and equitable bounds.

In China, the challenge is particularly prominent. Since the late 1990s, the country has dramatically expanded its higher education system. Yet resource allocation remains uneven—eastern coastal provinces concentrate elite institutions and cutting-edge research, while many central and western provinces face chronic underfunding, weaker infrastructure, and persistent talent outflows. This imbalance threatens educational equity and poses long-term risks to national sustainability, potentially entrenching a ‘haves vs. have-nots’ divide. Research confirms this spatial inequality: higher education development in China is heavily clustered in regions such as Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei, the Yangtze River Delta, and the Pearl River Delta. Disparities between the eastern, central, and western regions are pronounced in both input and outcome dimensions [

12]. Extensive quantitative evidence shows that higher education resources remain far from equitably distributed relative to provincial student populations—and this inequality has intensified over the past decade [

13]. Provincial panel analyses further document persistent inter-provincial inequality closely tied to uneven economic development, even during the period of rapid mass expansion [

14].At the access level, studies also show sizeable urban–rural disparities in entry to elite universities—gaps that have narrowed since 2010 but remain substantial—highlighting stratification pressures that intersect with regional divides [

15].

To assess such gaps, empirical studies have followed a recognizable methodological progression. First are dispersion-based measures (e.g., Gini, Theil, coefficient of variation), which summarize the magnitude of inequality but tend to treat “zero disparity” as an implicit ideal. Second, decomposition approaches—most notably the Dagum Gini—improve on simple dispersion by separating intra-regional, inter-regional, and transvariation components and by better handling group overlap [

16], thereby offering clearer diagnoses of where disparities arise. Third, spatial statistics and distributional diagnostics (e.g., Moran’s I, kernel density, geographical detectors) uncover spatial autocorrelation and multimodality that single indices may miss [

12]. Finally, system-linkage models such as coupling–coordination move beyond “education in isolation” to test how well higher education co-evolves with the economy, shifting the evaluative criterion from absolute equality to structural alignment [

17]. In short, later approaches enhance earlier ones by: (i) decomposing “where” inequality sits (Dagum vs. raw indices); (ii) revealing “how” it clusters in space (spatial diagnostics vs. scalars); and (iii) assessing whether such disparities are developmentally appropriate.

International organizations have long framed education-led development as a forward-looking path to sustainable growth, in which investment in higher education may precede and enable later economic gains. Building on this premise, we pose a policy-critical question that remains underexplored: Are inter-regional disparities in higher education rational and sustainable relative to underlying economic differences? Rather than merely describing inequality, our approach evaluates whether education gaps are kept within a rational range—namely, smaller than economic gaps—so that narrowing disparities in education can help drive the narrowing of economic disparities. Grounded in human-capital and endogenous-growth perspectives, we introduce a two-level Development Equilibrium Index (DEI) to evaluate alignment rather than absolute equality. At the national level, the N-DEI gauges whether education and economic disparities are aligned overall (rational when N-DEI > 0); at the provincial level, the P-DEI assesses each province’s equilibrium status within the national landscape.

Empirically, using panel data for 31 mainland Chinese provinces from 2003 to 2020, we find that the national index (N-DEI) is positive in most years, indicating that inter-provincial education disparities are generally smaller than economic disparities—consistent with higher education’s role in compressing economic gaps and supporting sustainability. At the provincial level (P-DEI), only 4 of 31 regions (12.9%) report negative values, whereas the vast majority occupy positions favorable to sustainable development. For 2020, a median-based quadrant display groups the 31 provinces into seven descriptive types and clarifies why P-DEI signs and magnitudes vary, forming the basis for targeted, province-specific policy recommendations.

4. Results

4.1. National Development Equilibrium Index (N-DEI)

This section analyzes the temporal evolution and structural characteristics of inter-provincial equilibrium in higher education development in China from 2003 to 2020, based on provincial-level data and the calculated values of the National Development Equilibrium Index (N-DEI).

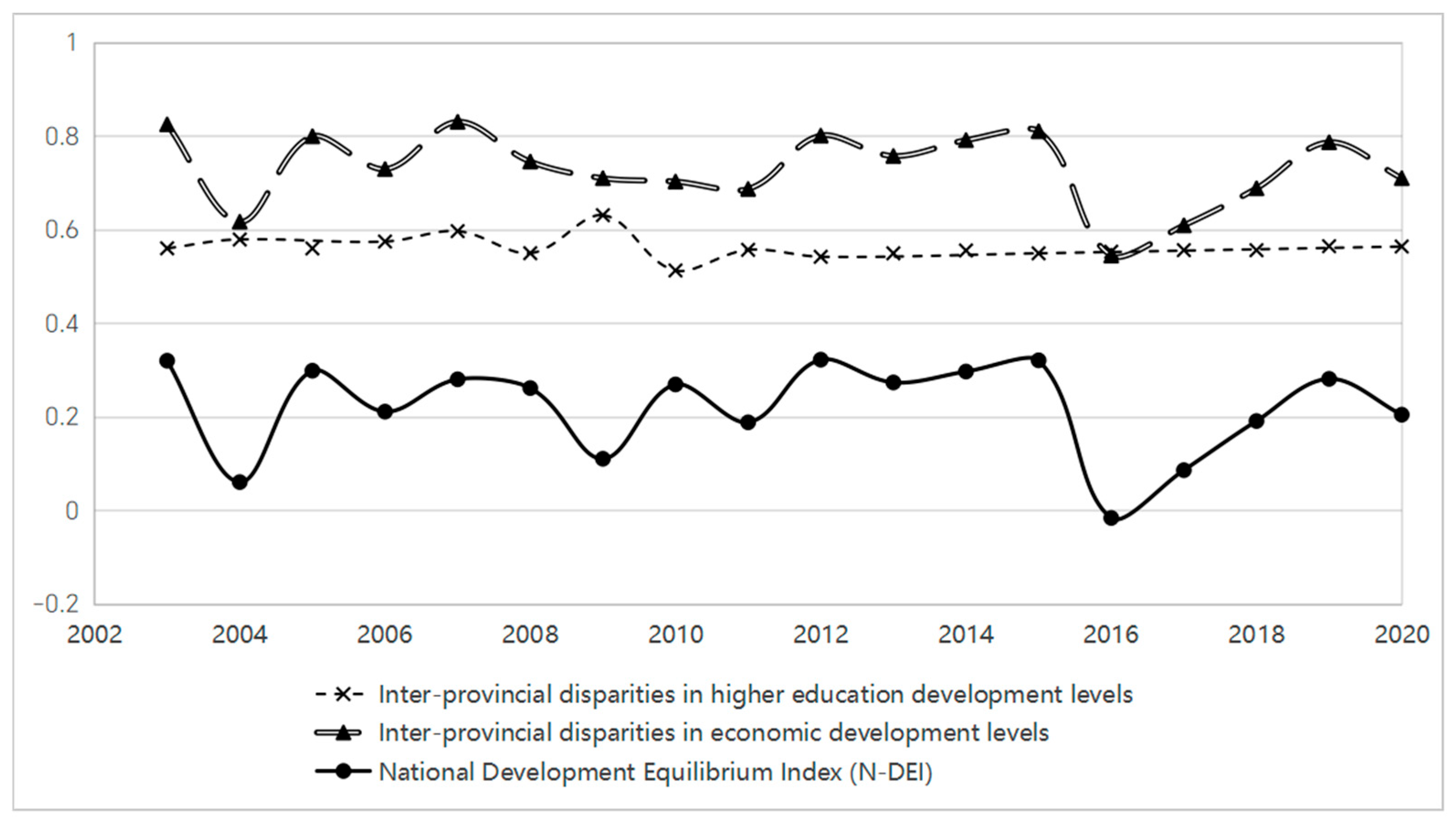

Figure 1 illustrates the trends in inter-provincial disparities in higher education development levels, economic development levels, and the corresponding national equilibrium index. Overall, from 2003 to 2020, disparities in higher education development across Chinese provinces were consistently smaller than those in economic development. This suggests that, on the whole, higher education development maintained a relatively balanced status. However, the

N-DEI values remained at a relatively low level throughout the period, with only limited improvement in recent years.

Between 2003 and 2005, the N-DEI showed a declining trend. From 2006 to 2011, the index exhibited slight fluctuations with a modest upward tendency. In 2012 the N-DEI reached a temporary peak (approximately 0.32) that coincided with the launch of the “Revitalization Plan for Higher Education in Central and Western China”; however, Bai–Perron style multiple-break testing indicates that this 2012 peak does not correspond to a statistically significant structural break.

During the 2013–2015 period, the N-DEI declined again. This drop can be attributed to the widening gap in economic development across provinces, while disparities in higher education showed only limited adjustment. Formal breakpoint analysis identifies a clear structural change in the 2015/2016 interval: the BIC-guided multi-break search points to a break around 2015–2016, coinciding with the observed sharp fall to the 2016 trough (−0.015). That year saw a significant narrowing of inter-provincial economic disparities, largely aligned with the nationwide promotion of supply-side structural reforms and the implementation of the “Three Cuts, One Reduction, and One Strengthening” policy. However, due to the inertia and lag in higher education system adjustments, the disparities in education development did not narrow correspondingly, resulting in a temporary imbalance. From 2017 onward, the N-DEI gradually rebounded and became more stable. The official launch of the “Double First-Class” initiative in 2017 further promoted the concentration of high-quality higher education resources while also supporting development in the central and western regions. This helped prevent a significant increase in regional disparities, with the N-DEI fluctuating mildly between 0.19 and 0.28 during the subsequent years. This suggests that the relationship between disparities in higher education and economic development had reached a relatively stable phase.

4.2. The Provincial Development Equilibrium Index (P-DEI)

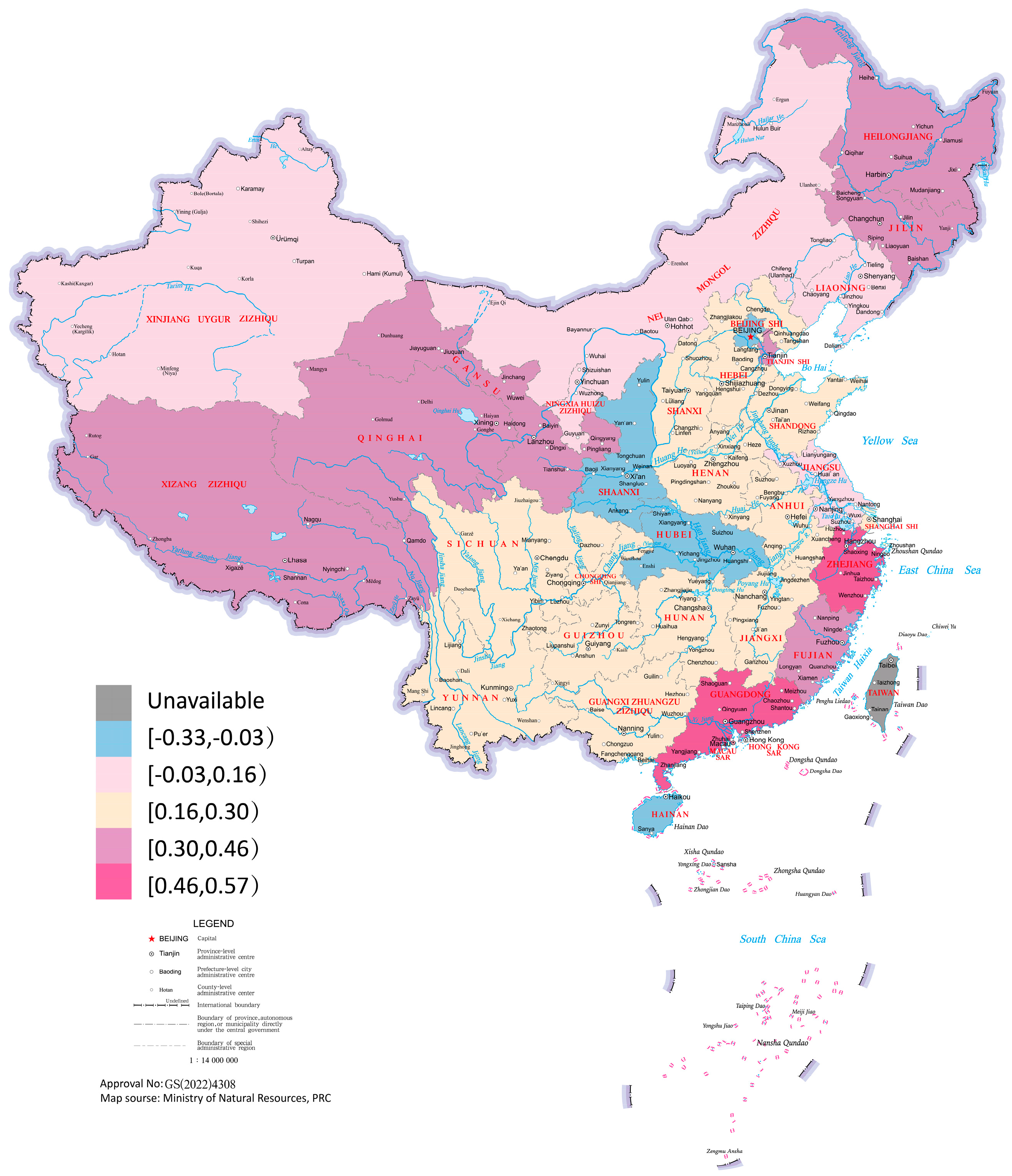

Using 2020 data, this section examines the spatial distribution and structural patterns of the Provincial Development Equilibrium Index (

P-DEI) across 31 provincial-level regions in China. To identify groups of provinces with similar

P-DEI profiles, we applied hierarchical agglomerative clustering using Ward’s minimum-variance linkage with Euclidean distance on the scalar

P-DEI values; the dendrogram was cut to produce five clusters (k = 5). As shown in

Figure 2, the highest-

P-DEI group contains Guangdong and Zhejiang. An upper-level group includes Tianjin, Qinghai, Shanghai, Heilongjiang, Xizang, Jilin, Fujian, and Gansu. A larger middle-to-lower group consists of Hebei, Shanxi, Shandong, Henan, Anhui, Jiangxi, Guangxi, Ningxia, Guizhou, Sichuan, Hunan, and Chongqing. A near-zero/low group comprises Hainan, Xinjiang, Nei Mongolia, and Jiangsu. A negative group includes Beijing, Hubei, and Shaanxi. Overall, eastern coastal provinces show higher

P-DEI, followed by western provinces with larger variation, while many central provinces fall into the middle-to-lower range.

Four provinces—Beijing, Hubei, Shaanxi, and Hainan—have negative P-DEI values (4/31 ≈ 12.9%). Only Beijing has a 95% bootstrap confidence interval entirely below zero (statistically below zero); the other three negative provinces have intervals overlapping zero (not statistically different from zero). Among the 27 provinces with positive P-DEI, 19 are statistically above zero: Zhejiang, Guangdong, Gansu, Jilin, Fujian, Xizang, Heilongjiang, Shanghai, Qinghai, Tianjin, Shandong, Anhui, Chongqing, Henan, Yunnan, Hebei, Guangxi, Shanxi, and Jiangsu. The remaining eight—Jiangxi, Hunan, Sichuan, Guizhou, Ningxia, Liaoning, Nei Mongolia, and Xinjiang—are positive but not statistically different from zero. Significance here pertains only to uncertainty around P-DEI relative to zero and does not imply causality.

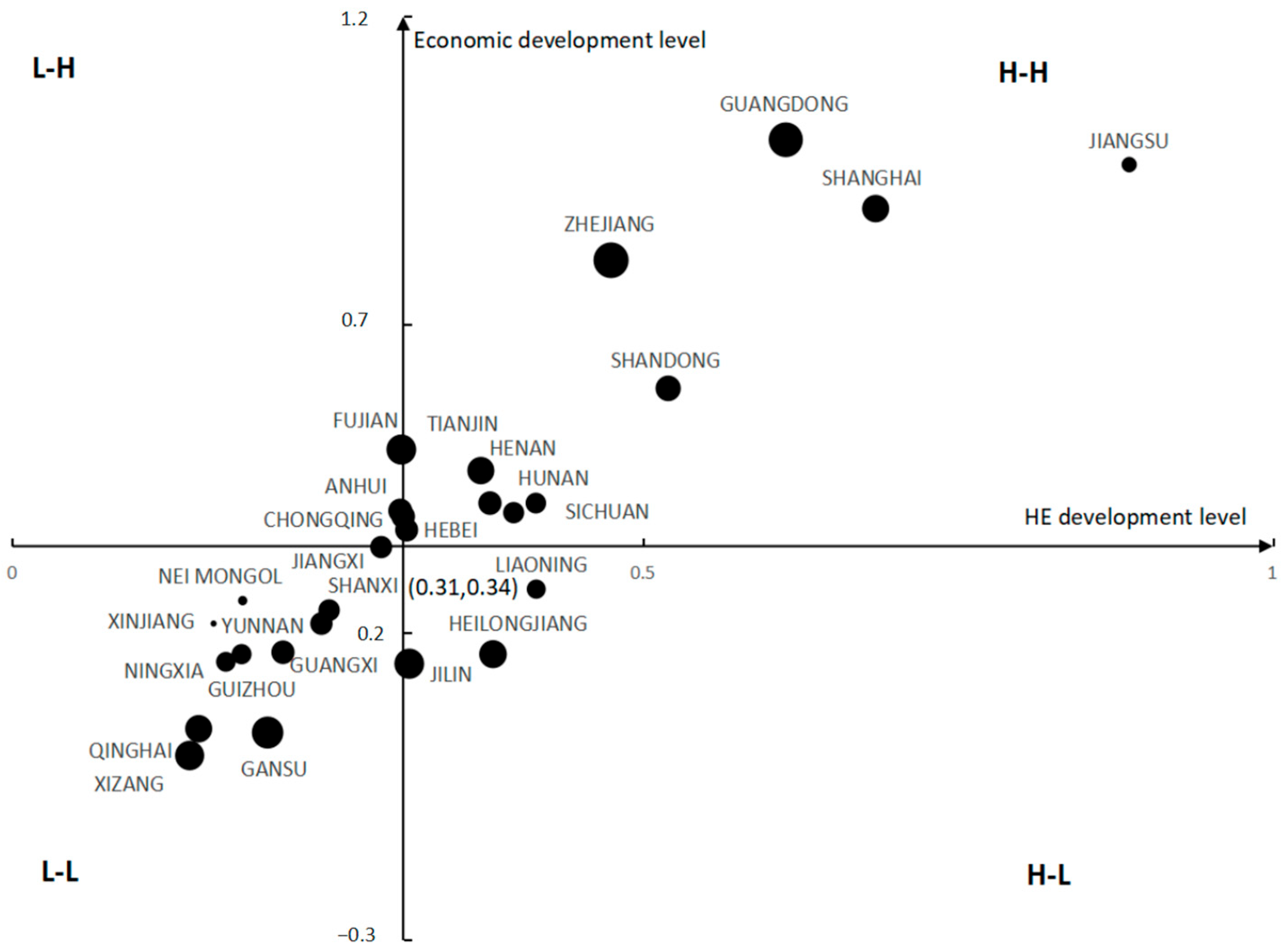

To further examine how provinces differ when

P-DEI is positive or negative,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 present a quadrant display using the sample medians of the higher-education (x) and economic (y) indices (0.31 and 0.34) as descriptive cut-offs. The sole purpose of these medians is to classify provinces as “higher” vs. “lower” on each axis for comparative positioning across the national sample; a practical advantage is that the resulting classification is not overly concentrated in a single group.

Figure 3 shows provinces with

P-DEI > 0, while

Figure 4 shows those with

P-DEI < 0. Marker area is proportional to ∣

P-DEI∣: in

Figure 3, larger markers denote larger positive

P-DEI; in

Figure 4, larger markers denote more negative

P-DEI.

Among the 27 provinces with P-DEI > 0, four patterns emerge:

4.2.1. High–High (H–H) Type (P-DEI > 0)

This type includes 11 provinces, mainly in the east (Zhejiang, Guangdong, Shanghai, Tianjin, Shandong, Hebei, and Jiangsu), together with central provinces (Hunan and Henan) and two western provinces (Sichuan and Chongqing). The defining feature here is that both higher education and the economy are at relatively high national levels; however, the lead in higher education is smaller than the lead in the economy, so P-DEI is positive. This structure provides a practical basis for the notion that higher education should be moderately ahead of the economy: by keeping inter-provincial education distances smaller than economy distances, higher education can play a guiding role that supports provinces with relatively weaker economies and, in turn, contributes to longer-run regional sustainability.

4.2.2. Low–High (L–H) Type (P-DEI > 0)

Fujian and Anhui fall into this category. Their higher education levels are slightly below the national average, and their education distances to other provinces are small—far smaller than their economy distances. In this national positioning, higher education helps reduce inter-provincial economy gaps. For these provinces, raising higher education levels toward the average would not weaken P-DEI so long as education distances remain below economy distances (e.g., through efficient allocation and targeted investment).

4.2.3. Low–Low (L–L) Type (P-DEI > 0)

This group comprises 11 provinces, including Shanxi and Jiangxi in central China and nine western provinces (Gansu, Xizang, Qinghai, Yunnan, Guangxi, Guizhou, Ningxia, Nei Mongolia, and Xinjiang). The typical profile is that both higher-education and economic levels are below the national median, but the relative disadvantage in higher education is smaller than that in the economy, yielding P-DEI > 0. This underscores a key finding of the study: even where overall levels are low, a modestly leading position in higher education can still underpin progress, provided education distances remain smaller than economy distances.

4.2.4. High–Low (H–L) Type (P-DEI > 0)

This includes Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning. These northeastern provinces have higher-education levels that are slightly above the national average, while their economies lag behind. By leveraging the guiding role of higher education to gradually narrow economy gaps with other provinces—and maintaining education distances below economy distances—these provinces are positioned in a favorable state for sustainable development.

In contrast, the four provinces with

P-DEI < 0 are classified into three types (see

Figure 4).

4.2.5. High–High (H–H) Type (P-DEI < 0): Beijing and Hubei

Both higher-education and economic levels are high, but higher education is excessively ahead of the economy, so P-DEI is negative. Such over-advancement can amplify talent attraction and agglomeration effects, further reinforcing local advantages and potentially widening inter-provincial disparities from a national perspective. These provinces should moderately de-concentrate higher-education resources. In fact, Beijing has begun relocating parts of university functions to Hebei, which is broadly consistent with this analysis. Beijing’s bootstrap CI lies entirely below zero (statistically below 0), indicating urgency for adjustment; Hubei’s CI overlaps zero (not statistically significant), suggesting that overly forceful reallocation is unnecessary at this stage.

4.2.6. High–Low (H–L) Type (P-DEI < 0): Shaanxi

In Shaanxi, higher-education standing is relatively strong, whereas the economy is slightly below the national average. The leading edge of higher education relative to peers is too large for its economic position, producing P-DEI < 0. Given that the bootstrap result is not significant, moderate adjustments—such as enhancing industrial absorption and strengthening university–industry linkages to ensure education distances do not exceed economy distances—are advisable.

4.2.7. Low–Low (L–L) Type (P-DEI < 0): Hainan

Hainan is below the national medians on both axes, and the education lag is more severe than the economy lag, resulting in P-DEI < 0. Because higher education has a leading, pre-emptive role, insufficient improvement in higher education may further widen Hainan’s economic disadvantage relative to other provinces. Targeted investment and alignment with local development priorities are therefore needed to reduce education distances below economy distances and improve P-DEI.

5. Discussion

At the national level, the expansion of higher education is often expected to widen access, improve social mobility, and reduce inequality. Evidence from China, however, reveals a more complex and sometimes paradoxical reality. Since the late 1990s, China has dramatically expanded its higher education system, yet regional disparities remain pronounced. Massification and partial privatization have not reduced inequalities; in many respects, they have reinforced them. As Jiang (2018) notes, initiatives such as the Changjiang Scholars Program, though designed to promote excellence, have disproportionately benefited elite universities in already advantaged regions, thereby widening rather than narrowing developmental gaps [

36]. Similarly, Gao (2018) observes that while top coastal universities have advanced in global rankings, the uneven distribution of resources continues to hinder balanced national development [

37]. Recent synthetic reviews reach similar conclusions for the post-massification era, documenting persistent stratification and uneven gains across regions and groups [

38,

39].

Two structural dynamics explain this persistence. The first is institutional path dependence. Under the planned economy, resources were distributed relatively evenly across six administrative regions, with centralized planning and graduate job assignment preventing extreme disparities [

40]. Following the reform era, however, China’s strategy shifted to “supporting key regions to drive the whole.” This approach prioritized coastal growth, fueling rapid economic advancement but deepening geographic polarization in higher education. The second is the enduring imbalance in economic development across provinces. Wealthier provinces such as Guangdong and Jiangsu, leveraging robust fiscal capacity and dynamic innovation ecosystems, have invested heavily in building world-class universities. By contrast, less-developed provinces in central and western China, constrained by limited resources, have fallen further behind. Together, these dynamics reflect the Matthew effect—“the strong get stronger, while the weak get weaker”—and continue to exacerbate structural divergence in outcomes.

Our findings, operationalized through the Development Equilibrium Index (DEI), provide a new interpretive perspective. Unlike conventional metrics such as the Gini or Theil indices, which implicitly assume that zero disparity is ideal, the DEI evaluates whether education gaps remain smaller than economic gaps (i.e., whether P-DEI/N-DEI are positive). Results show that the national system as a whole has maintained a positive DEI for most of the period, though with only slow and fragile improvement. By shifting the evaluative criterion from absolute equality to alignment, the DEI underscores that inequalities may be acceptable if education disparities remain below economic disparities, but become problematic when they exceed them (negative DEI), raising risks of long-term divergence.

At the provincial level, the quadrant-based typology reveals seven distinct configurations of

P-DEI values, each associated with specific sustainability challenges and policy implications. Among provinces with

P-DEI > 0, four categories emerge. High–High (H–H) provinces such as Zhejiang, Shanghai, Guangdong, and Jiangsu illustrate endogenous growth dynamics: the co-location of advanced economies and strong higher education systems generates virtuous cycles of innovation, agglomeration, and human capital development. Yet this positive configuration remains fragile. Their challenge is to preserve competitiveness while also functioning as national growth poles. Excessive concentration risks exacerbating inequalities elsewhere, making outward-oriented strategies—knowledge spillovers, “brain circulation,” and interregional collaborations—essential. Evidence suggests that such linkages can mitigate inequalities if they promote two-way flows [

41].

Low–High (L–H) provinces, such as Fujian and Anhui, represent the opposite configuration: economies outpace education development. Their positive P-DEI reflects smaller education gaps relative to economic ones, but it also highlights the time lag between educational investment and economic returns. To prevent education from becoming a bottleneck, these provinces must expand capacity in strategic fields, strengthen quality assurance, and accelerate alignment with industrial upgrading.

Low–Low (L–L) provinces, such as Gansu, Guizhou, and Qinghai, operate at modest levels in both higher education and the economy. Their positive P-DEI indicates that their education lag is smaller than their economic lag, offering a fragile but policy-relevant alignment. The challenge is to leverage this modest educational lead as a driver of transformation, for example, by cultivating niche strengths in ecological tourism, renewable energy, or modern agriculture, while also improving local absorptive capacity. Without stronger economic structures, graduate outmigration will perpetuate cycles of underdevelopment.

High–Low (H–L) provinces, including Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning, show relatively strong higher education legacies but weaker economies. Their positive P-DEI reflects education gaps smaller than economic ones, but continued economic stagnation could undermine sustainability. Policy should therefore reconnect universities with new industries, strengthen technology transfer, and foster entrepreneurial ecosystems capable of absorbing surplus talent.

In contrast, provinces with P-DEI < 0 reveal unsustainable patterns. Beijing (H–H with P-DEI < 0) illustrates over-concentration, where higher education is excessively advanced relative to its economy. Policy should link Double First-Class funds to verifiable cross-regional spillovers and relocate non-core functions to Tianjin or Hebei. For Hubei, tying competitive allocations to collaborative outputs with neighboring provinces (e.g., graduate flows, co-authored patents, teaching-hospital rotations) can ensure diffusion of benefits. Shaanxi (H–L with P-DEI < 0) shows strong education but weaker economic performance; strengthening university–industry linkages and absorptive capacity is critical. Hainan (L–L with P-DEI < 0) combines weak performance on both axes, with higher education lagging more than the economy. As a Free Trade Port, it faces risks of human-capital shortages; targeted investments in applied programs (marine economy, logistics, digital trade) and science–industry partnerships are needed.

Taken together, these findings show that P-DEI structures are differentiated rather than uniform. Positive P-DEI types demonstrate that keeping education gaps below economic gaps—even at low levels—can support balanced growth, provided strategies are tailored to local advantages. Negative P-DEI cases highlight misalignment and require urgent correction. By distinguishing between these categories, the DEI framework not only diagnoses disparities but also identifies actionable pathways for strengthening higher education’s role in sustainable national development.

From a policy perspective, the findings suggest differentiated strategies. Provinces with P-DEI > 0 should maintain or enhance alignment, while contributing to national cohesion through outward-oriented spillovers. Provinces with P-DEI < 0 require structural reforms to bring education gaps back within permissible bounds. Recognizing this distinction is essential to moving beyond one-size-fits-all approaches toward developmentally rational alignment.

Beyond China, the findings contribute to global debates on higher education and regional inequality. Spatial disparities are not unique to China but reflect a global hierarchy of knowledge production. Altbach (2004) argues that globalization has intensified the divide between knowledge-producing “centers” in North America and Western Europe and knowledge-consuming “peripheries” in the Global South [

42]. Negative

P-DEI cases in China, such as Beijing’s over-concentration or Fujian and Anhui’s lagging provision, mirror challenges in other contexts—for example, London’s dominance in the UK or the contrasts between U.S. coasts and interior states. The DEI framework thus offers a transferable analytical tool to examine whether higher education–economy alignment is developmentally rational in diverse settings.

These dilemmas also resonate with Europe. Hazelkorn (2011) highlights how the pursuit of “world-class university” status has created tensions between global competitiveness and regional cohesion [

43]. The European Union faces challenges similar to China’s: reconciling elite concentration with balanced development across member states. China’s negative-

P-DEI cases resemble the dominance of Paris or Oxford–Cambridge, where international prestige comes at the cost of regional equity.

The framework also contributes to understanding the South–North divide. Marginson (2022) emphasizes that China’s scientific development reflects a dynamic interplay between global integration and national imperatives [

9].This mirrors challenges in other parts of the Global South, such as India or Brazil, where balancing global competition with domestic equity is critical. By focusing on whether education gaps remain smaller than economic gaps, the DEI provides a new lens to distinguish between disparities that are functionally sustainable and those that are destabilizing.

Finally, the study contributes to debates on higher education’s role in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. UNESCO (2022) underscores that education is both a global public good and a foundation for just and sustainable futures [

44]. By operationalizing a proportional framework linking education to economic disparities, the DEI shifts attention from absolute levels of access or quality to alignment and developmental rationality. This perspective is essential for policymakers seeking to balance excellence, equity, and sustainability.

Despite these contributions, limitations remain. First, the analysis is descriptive and diagnostic; it identifies patterns in DEI but does not establish causal mechanisms. Policy recommendations should therefore be viewed as hypotheses rather than confirmed effects. Future work will pre-specify testable hypotheses (e.g., “keeping education distances below economic distances raises P-DEI for lagging provinces”) and employ causal designs such as difference-in-differences, event studies around major policy shifts (e.g., 2012 Plan; 2017 Double First-Class), or spatial panel models (e.g., SAR/SDM with province fixed effects). Where feasible, complementary strategies (instrumental variables, synthetic control) will be explored. Second, our use of min–max normalization improves interpretability but may be sensitive to extreme years; for P-DEI values near zero, signs could occasionally flip. Nonetheless, provincial rankings are preserved because the transformation is monotonic, and quadrant classifications remain largely stable. Third, the coefficient of variation used in N-DEI is sensitive to distributional shape and small means, which can introduce volatility; these issues do not affect P-DEI, which is based on relative distances. Robustness checks using entropy- or rank-based measures will be explored in future work.