Diversification of Rural Development in Poland: Considerations in the Context of Sustainable Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the characteristics of rural areas at high levels of sustainable development for each of the following domain types: economic, social, and environmental?

- What are the characteristics of rural areas at low levels of sustainable development for each of the following domain types: economic, social, and environmental?

- What is the geographic distribution of rural areas at high and low levels of sustainable development?

- Which territorial features affect these distributions?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

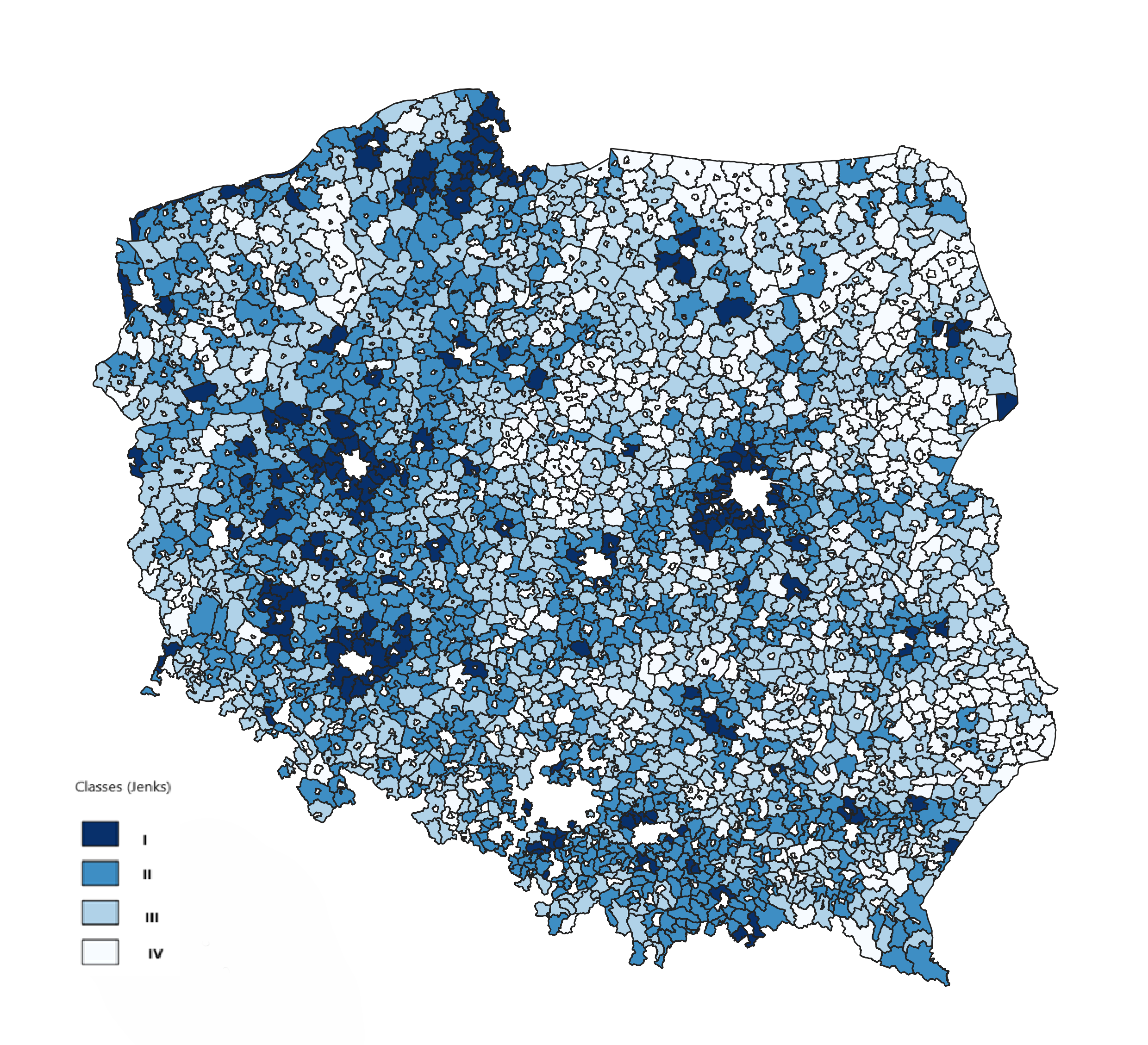

3.1. Economic Domain

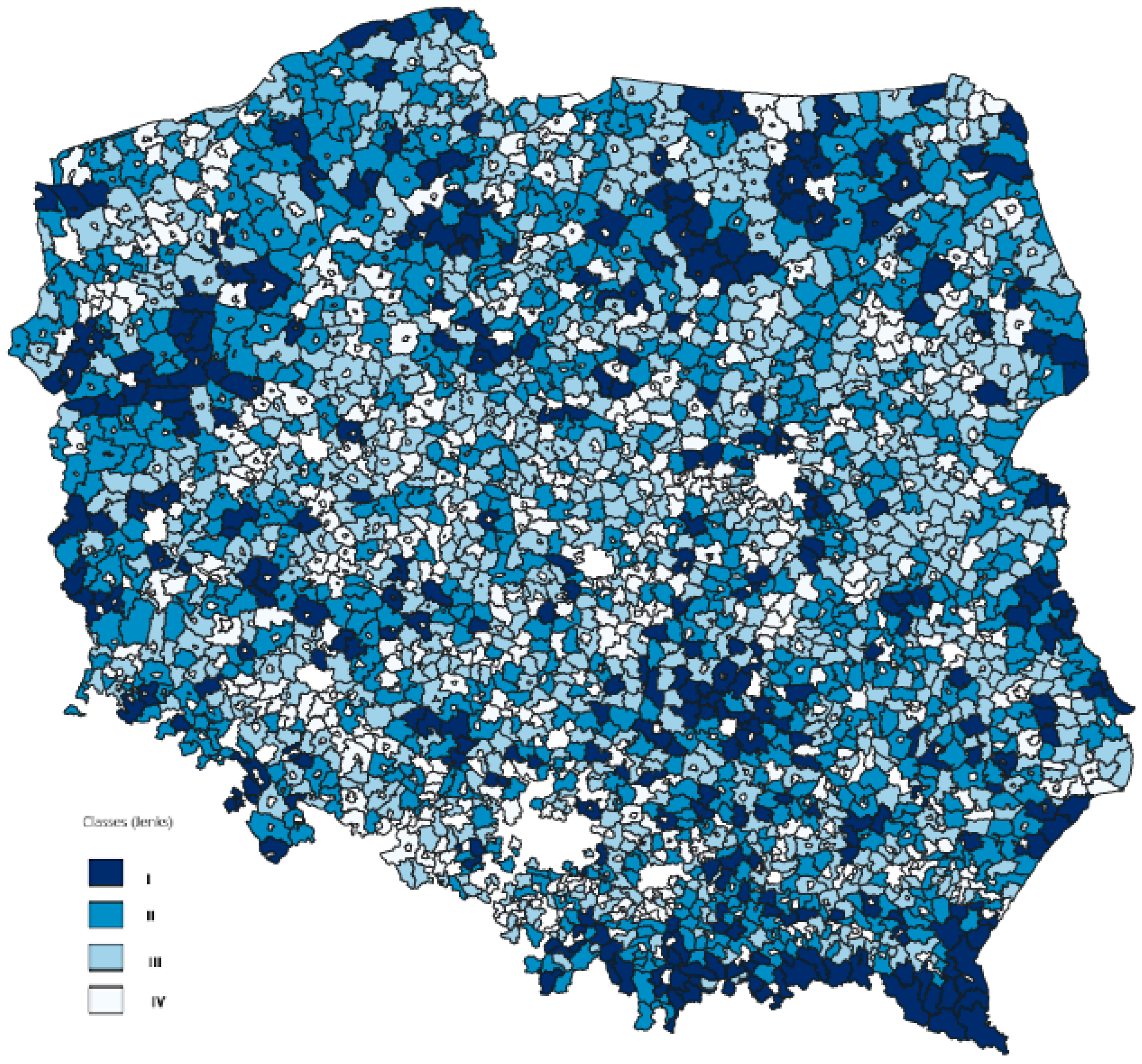

3.2. Social Domain

3.3. Environmental Order

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cattivelli, V. Where Is the City? Where Is the Countryside? Assessing the Methods for the Classification of Urban, Rural, and Intermediate Areas in Europe. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 109, 103288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poczta, W. Przemiany w rolnictwie polskim w okresie transformacji ustrojowej i akcesji Polski do UE [Changes in Polish Agriculture in the Period of Political Transformation and Accession of Poland to the EU]. Wieś Rol. 2020, 187, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanny, M.; Rosner, A.; Komorowski, Ł. Monitoring Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich; Etap III; Fundacja Europejski Fundusz Rozwoju Wsi Polskiej: Miedziana, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aslund, A.; Orlowski, W.M. The Polish Transition in a Comparative Perspective (Polska Transformacja Ustrojowa w Perspektywie Porównawczej). In Proceedings of the mBank–CASE Seminar Proceedings; CASE: Tokyo, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Territorial Cohesion in Rural Europe: The Relational Turn in Rural Development; Copus, A., de Lima, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-203-70500-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dax, T. Shaping Rural Development Research in Europe: Acknowledging the Interrelationships between Agriculture, Regional and Ecological Development. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2014, 116, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- OECD. The New Rural Paradigm: Policies and Governance; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, N.; Brown, D.L. Placing the Rural in Regional Development. Reg. Stud. 2009, 43, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryden, J. Rural Development Indicators and Diversity in the European Union. In Proceedings of the Conference on “Measuring Rural Diversity”, Washington, DC, USA, 21–22 November 2002; Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Rural-Development-Indicators-and-Diversity-in-the-Bryden/68f40b9e4e0746637b32da361be81fc8fc11fe0c (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Stanny, M. Wieś, obszar wiejski, ludność wiejska—O problemach z ich definiowaniem. Wielowymiarowe spojrzenie. Wieś Rol. 2014, 162, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.S.; Nguyen, T.D.; Brownstein, N.A.; Garcia, D.; Walker, H.C.; Watson, J.T.; Xin, A. Definitions, Measures, and Uses of Rurality: A Systematic Review of the Empirical and Quantitative Literature. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eupen, M.; Metzger, M.J.; Pérez-Soba, M.; Verburg, P.H.; van Doorn, A.; Bunce, R.G.H. A Rural Typology for Strategic European Policies. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloke, P.; Marsden, T.; Mooney, P.; Ray, C. Neo-Endogenous Rural Development in the EU; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2006; pp. 278–291. [Google Scholar]

- Biczkowski, M. LEADER as a Mechanism of Neo-Endogenous Development of Rural Areas: The Case of Poland. Misc. Geogr. Reg. Stud. Dev. 2020, 24, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fałkowski, J. Political Accountability and Governance in Rural Areas: Some Evidence from the Pilot Programme LEADER+ in Poland. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkin, J. Wielofunkcyjność Rolnictwa i Obszarów Wiejskich. In Wyzwania Przed Obszarami Wiejskimi i Rolnictwem w Perspektywie lat 2014–2020; Kłodziński, M., Ed.; IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2008; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Matuszczak, A. Ewolucja Kwestii Agrarnej a Środowiskowe Dobra Publiczne; Instytut Ekonomiki Rolnictwa i Gospodarki Żywnościowej-Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zegar, J.S. Przesłanki Nowej Ekonomiki Rolnictwa. Zagadnienia Ekon. Rolnej 2007, 4, 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Czyżewski, A.; Kułyk, P. Dobra Publiczne w Koncepcji Wielofunkcyjnego Rozwoju Rolnictwa; Ujęcie Teoretyczne i Praktyczne. Probl. World Agric. Rol. Świat. 2011, 11, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, R.; Sleszynski, J. Nowe Funkcje Rolnictwa-Dostarczanie Dóbr Publicznych. Rocz. Nauk. Stowarzyszenia Ekon. Rol. Agrobiznesu 2009, 11, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Chen, C.; Findlay, C. A Review of Rural Transformation Studies: Definition, Measurement, and Indicators. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 3568–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Development Research Centre. The Local Agenda 21 Planning Guide: An Introduction to Sustainable Development; IDRC: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1996; ISBN 978-0-88936-801-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sztumski, W. Idea Zrównoważonego Rozwoju a Możliwości Jej Urzeczywistnienia. Probl. Ekorozwoju 2006, 1, 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Borys, T. Wskaźniki Zrównoważonego Rozwoju; Ekonomia i Środowisko: Warsaw, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Borys, T. Zrównoważony Rozwój–Jak Rozpoznać Ład Zintegrowany. Probl. Ekorozwoju 2011, 6, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J. The Economic Transformation of Eastern Europe: The Case of Poland. Econ. Plan. 1992, 25, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorzelak, G. Regional and Local Potential for Transformation in Poland; Regional and Local Studies; European Institute for Regional and Local Development: Warsaw, Poland, 1998; ISBN 978-83-87722-01-2. [Google Scholar]

- Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z dnia 2 kwietnia 1997 r. (Dz. U. Nr 78, poz. 483 z późn. zm.). Available online: https://sip.lex.pl/akty-prawne/dzu-dziennik-ustaw/konstytucja-rzeczypospolitej-polskiej-16798613 (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Stanny, M. Przestrzenne Zróżnicowanie Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich w Polsce; Instytut Rozwoju Wsi i Rolnictwa Polskiej Akademii Nauk: Warsaw, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stanny, M.; Komorowski, Ł.; Rosner, A. The Socio-Economic Heterogeneity of Rural Areas: Towards a Rural Typology of Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopczewska, K. Renta Geograficzna a Rozwój Społeczno-Gospodarczy; CeDeWu: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kachniarz, M. Bogactwo Gmin–Efekt Gospodarności Czy Renty Geograficznej? Ekonomia 2011, 17, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bański, J.; Mazur, M. Classification of Rural Areas in Poland as an Instrument of Territorial Policy. Land Use Policy 2016, 54, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocki, F.; Lira, J. Statystyka Opisowa; Wydawnictwo Akademii Rolniczej im; Augusta Cieszkowskiego: Poznań, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Opial-Gałuszka, U. Zastosowanie Wielowymiarowej Analizy Porównawczej (WAP) Do Klasyfikacji Obiektów Przestrzennych Pod Kątem Wpływu Działalności Człowieka Na Środowisko Wodne. In Antropogeniczne Oddziaływania i ich Wpływ na Środowisko Wodne; Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej: Warsaw, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jenks, G.F. The Data Model Concept in Statistical Mapping. Int. Yearb. Cartogr. 1967, 7, 186–190. [Google Scholar]

- North, M.A. A Method for Implementing a Statistically Significant Number of Data Classes in the Jenks Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2009 Sixth International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery, Tianjin, China, 14–16 August 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 1, pp. 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Yang, S.T.; Li, H.W.; Zhang, B.; Lv, J.R. Research on Geographical Environment Unit Division Based on the Method of Natural Breaks (Jenks). Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2013, 40, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanny, M.; Czarnecki, A. Zrównoważony Rozwój Obszarów Wiejskich Zielonych Płuc Polski: Próba Analizy Empirycznej; Instytut Rozwoju Wsi i Rolnictwa Polskiej Akademii Nauk: Warsaw, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Adamowicz, M.; Dresler, E. Zrównoważony Rozwój Obszarów Wiejskich Na Przykładzie Wybranych Gmin Województwa Lubelskiego (Sustainable Development of Rural Areas the Case of Selected Communes of Lublin Voivodeship–in Polish). Zesz. Nauk. Akad. Rol. We Wrocławiu 2006, 540, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Adamowicz, M.; Smarzewska, A. Model Oraz Mierniki Trwałego i Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich w Ujęciu Lokalnym. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW Polityki Eur. Finans. Mark. 2009, 1, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, P.; Stagl, S.; Zawalinska, K.; Michalek, J. Measuring Quality of Life in Rural Europe. A Review of Conceptual Foundations. East. Eur. Countrys. 2007, 13, 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Michalek, J.; Zarnekow, N. Application of the Rural Development Index to Analysis of Rural Regions in Poland and Slovakia. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 105, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawalińska, K. Rozwój Obszarów Wiejskich: Doświadczenia Krajów Europejskich; Instytut Rozwoju Wsi i Rolnictwa Polskiej Akademii Nauk: Warsaw, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Berger-Schmitt, R.; Noll, H.-H. Conceptual Framework and Structure of a European System of Socialindicators; ZUMA: Kamakura, Japan, 2000; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Schultink, G. Critical Environmental Indicators: Performance Indices and Assessment Models for Sustainable Rural Development Planning. Ecol. Model. 2000, 130, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowicz, M.; Zwolińska-Ligaj, M. Koncepcja Wielofunkcyjności Jako Element Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW Polityki Eur. Finanse Mark. 2009, 2, 11–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bański, J.; Stola, W. Przemiany Struktury Przestrzennej i Funkcjonalnej Obszarów Wiejskich w Polsce, Studia Obszarów Wiejskich; PAN Instytut Geografii Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego: Warsaw, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stanny, M. Typologia Wiejskich Obszarów Peryferyjnych Pod Względem Anatomii Struktury Społeczno-Gospodarczej. Wieś Rol. 2011, 151, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churski, P. Obszary Problemowe w Polsce z Perspektywy Celów Polityki Regionalnej Unii Europejskiej; Wyższa Szkoła Humanistyczno-Ekonomiczna we Włocławku: Warsaw, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bański, J. Typy Ludnościowych Obszarów Problemowych. Stud. Obsz. Wiej. 2002, 2, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Banski, J. Obszary Problemowe w Polsce; Biuletyn/PAN Komitet Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Kraju: Warsaw, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bański, J.; Czapiewski, K. Identyfikacja i Ocena Czynników Sukcesu Społeczno-Gospodarczego Na Obszarach Wiejskich; Zespół Badań Obszarów Wielskich IGiPZ PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Czapiewski, K. Koncepcja Wiejskich Obszarów Sukcesu Społeczno-Gospodarczego i Ich Rozpoznanie w Województwie Mazowieckim. Studia Obszarów Wiejskich; IGiPZ PAN, Warszawa, Polska, 2010. Available online: https://rcin.org.pl/igipz/Content/647/PDF/Wa51_3554_r2010-t22_SOW.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Bartkowiak-Bakun, N. Instytucjonalny Wymiar Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich w Polsce; Wydanie, I., Ed.; CeDeWu: Warszawa, Poland; Krajowa Sieć Obszarów Wiejskich: Warszawa, Poland; Uniwersytet Przyrodniczy w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2023; ISBN 978-83-8102-769-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowiak-Bakun, N. Ocena Oddziaływania Wybranych Działań PROW 2014–2020 na Zrównoważony Rozwój Obszarów Wiejskich Polski: Analiza Regionalna—II Etap Badań; Wydanie, I., Ed.; CeDeWu: Warszawa, Poland, 2021; ISBN 978-83-8102-524-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski, A. Zrównoważony Rozwój Gospodarstw Rolnych z Uwzgędnieniem Wpływu Wspólnej Polityki Rolnej Unii Europejskiej; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego Poznań: Poznań, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Czapiewski, K. Location Matters–Analiza Zależności Pomiędzy Dostępnością Przestrzenną a Sukcesem Społeczno-Gospodarczym Obszarów Wiejskich Mazowsza. Red M Wesołowska Stud. Obsz. Wiej. 2011, 26, 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Czapiewski, K. Wyposażenie Infrastrukturalne i Potencjał Gospodarczy Obszarów Wiejskich a Pozarolnicze Funkcje Gmin.[W:] E. Pałka Red Pozar. Dział. Gospod. Obsz. Wiej. Stud. Obsz. Wiej. 2004, 5, 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Churski, P.; Dubownik, A.; Szyda, B.; Adamiak, C.; Pietrzykowski, M. Wewnętrzne Peryferie w Świetle Wybranych Typologii Obszarów Wiejskich. Rozw. Reg. Polityka Reg. 2024, 69, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkin, J. Sprawiedliwość–Najważniejsza Cnota Społecznych Instytucji. Wieś Rol. 2023, 198, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śleszyński, P.; Bański, J.; Degórski, M.; Komornicki, T. Delimitacja Obszarów Strategicznej Interwencji Państwa: Obszarów Wzrostu i Obszarów Problemowych: Delimitation of the State Intervention Strategic Areas: Growth Areas and Problem Areas; IGiPZ PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; Volume 260. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Liu, Y. Why Some Rural Areas Decline While Some Others Not: An Overview of Rural Evolution in the World. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidich, A.J.; Bensman, J. Small Town in Mass Society: Class, Power, and Religion in a Rural Community; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- The Sustainability of Rural Systems: Geographical Interpretations; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-1-4020-0513-8.

| Domain | Indicator (Year/Years) |

|---|---|

| economic | Businesses per 1000 population (2019) Unemployed persons per 100 people of working age * (2019) Transportation expenditures per capita (2017–2019) Share of PIT and CIT taxes in total income (2017–2019) Own income per capita (PLN) (2017–2019) Investment expenditures in total expenditures (2017–2019) Funds obtained from the EU per capita (PLN) (2017–2019) |

| social | Expenditures on social assistance per capita (PLN) * (2017–2019) Expenditures on physical culture and sports per capita (PLN) (2017–2019) Expenditures on culture and arts per capita (PLN) (2017–2019) Residential area per capita (m2) (2019) Voter turnout in local elections in 2018. (%) Share of councilors with secondary and higher education in total councilors (%) (2017–2019) Foundations, associations, and social organizations per 1000 residents (2019) Number of cultural events per 1000 residents (2017–2019) Relationship between children and the elderly (2017–2019) Population growth (per 1000 residents) (2017–2019) Feminization rate (20–35 years old) (2017–2019) Migration balance (per 1000 residents) (2017–2019) |

| environmental | Share of forests in total area (%) (2019) Share of meadows and pastures in agricultural land (%) (2019) Tourists using overnight accommodations per 1000 residents (2019) Area of wild dumps per 100 km2 of total area (2019) Total household water consumption per 1 resident (m3) (2019) Total waste per 1 resident (kg) (2019) Users of water supply system in total population (%) (2019) Using sewage treatment plants in total population (%) (2019) Share of investment expenses of department 901 in total investment expenses (%) ** (2017–2019) Investment expenditures of department 901 per capita (PLN) ** (2017–2019) |

| Specification | Class I | Class II | Class III | Class IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic domain | 0.31–0.54 | 0.25–0.30 | 0.20–0.24 | 0.06–0.19 |

| Social domain | 0.39–0.63 | 0.34–0.38 | 0.31–0.33 | 0.19–0.30 |

| Environmental domain | 0.50–0.65 | 0.44–0.49 | 0.38–0.43 | 0.23–0.37 |

| Specification | Class I | Class II | Class III | Class IV | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Businesses per 1000 population * | 208.8 | 147.4 | 121.5 | 106.9 | 133.2 |

| Unemployed persons per 100 people of working age | 2.7 | 3.5 | 4.4 | 7.2 | 4.6 |

| Transportation expenditures per capita | 749.2 | 439.8 | 355.1 | 275.2 | 395.7 |

| Share of PIT and CIT taxes in total income | 21.8 | 16.0 | 12.1 | 9.9 | 10.5 |

| Own income per capita (PLN) | 3319.4 | 1972.5 | 1542.6 | 1379.3 | 1784.3 |

| Investment expenditures in total expenditures | 25.9 | 19.9 | 15.1 | 10.5 | 16.4 |

| Funds obtained from the EU per capita (PLN) | 405.7 | 295.2 | 191.6 | 128.3 | 225.4 |

| Voivodeship | Class I | Class II | Class III | Class IV | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dolnośląskie | 29 | 55 | 35 | 14 | 133 |

| Kujawsko-pomorskie | 4 | 21 | 57 | 45 | 127 |

| Lubelskie | 4 | 42 | 89 | 58 | 193 |

| Lubuskie | 5 | 28 | 27 | 13 | 73 |

| Łódzkie | 16 | 52 | 67 | 24 | 159 |

| Małopolskie | 11 | 61 | 78 | 18 | 168 |

| Mazowieckie | 31 | 50 | 98 | 100 | 279 |

| Opolskie | 2 | 22 | 38 | 6 | 68 |

| Podkarpackie | 5 | 36 | 57 | 45 | 143 |

| Podlaskie | 8 | 21 | 49 | 27 | 105 |

| Pomorskie | 9 | 39 | 38 | 12 | 98 |

| Śląskie | 21 | 63 | 32 | 2 | 118 |

| Swiętokrzyskie | 2 | 19 | 45 | 31 | 97 |

| Warmińsko-mazurskie | 4 | 14 | 32 | 50 | 100 |

| Wielkopolskie | 28 | 77 | 93 | 9 | 207 |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 13 | 15 | 32 | 42 | 102 |

| Total | 192 | 615 | 867 | 496 | 2170 |

| Specification | Class I | Class II | Class III | Class IV | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expenditures on social assistance per capita (PLN) * | 466.3 | 519 | 580.8 | 554.9 | 558.6 |

| Expenditures on physical culture and sports per capita (PLN) | 243.4 | 159.4 | 90.2 | 51.7 | 74.4 |

| Expenditures on culture and arts per capita (PLN) | 362.2 | 200.5 | 169.5 | 133 | 152.8 |

| Residential area per capita (m2) | 49.1 | 32.2 | 28.8 | 30.1 | 30.2 |

| Voter turnout in local elections in 2018 (%) | 60.4 | 58.9 | 56.7 | 55.1 | 56 |

| Share of councilors with secondary and higher education in total councilors (%) | 87.5 | 86 | 82.4 | 72.2 | 76.5 |

| Foundations, associations, and social organizations per 1000 residents | 4 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.5 |

| Number of cultural events per 1000 residents | 19.2 | 9.6 | 8.8 | 5.8 | 7.2 |

| Relationship between children and the elderly | 122 | 96.2 | 80 | 63.9 | 72.1 |

| Population growth (per 1000 residents) | 6.1 | 3.4 | 0.8 | −2.3 | −0.8 |

| Feminization rate (20–35 years old) | 101.6 | 97.5 | 94.6 | 91.4 | 92.9 |

| Migration balance (per 1000 residents) | 19.6 | 7.4 | 0.5 | −2.1 | −0.2 |

| Voivodeship | Class I | Class II | Class III | Class IV | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dolnośląskie | 4 | 14 | 44 | 71 | 133 |

| Kujawsko-pomorskie | 1 | 8 | 47 | 71 | 127 |

| Lubelskie | 2 | 29 | 162 | 193 | |

| Lubuskie | 1 | 3 | 41 | 28 | 73 |

| Łódzkie | 1 | 2 | 29 | 127 | 159 |

| Małopolskie | 27 | 65 | 76 | 168 | |

| Mazowieckie | 4 | 22 | 83 | 170 | 279 |

| Opolskie | 1 | 5 | 62 | 68 | |

| Podkarpackie | 1 | 4 | 52 | 86 | 143 |

| Podlaskie | 2 | 9 | 94 | 105 | |

| Pomorskie | 10 | 25 | 41 | 22 | 98 |

| Śląskie | 1 | 19 | 98 | 118 | |

| Świętokrzyskie | 5 | 15 | 77 | 97 | |

| Warmińsko-mazurskie | 2 | 6 | 44 | 48 | 100 |

| Wielkopolskie | 8 | 29 | 92 | 78 | 207 |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 4 | 8 | 37 | 53 | 102 |

| Total | 37 | 158 | 652 | 1323 | 2170 |

| Specification | Class I | Class II | Class III | Class IV | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Share of forests in total area (%) | 40.4 | 29.4 | 22.1 | 16.3 | 26.5 |

| Share of meadows and pastures in agricultural land (%) | 29.7 | 22.1 | 18.8 | 15.4 | 21.1 |

| Share of legally protected areas in total area (%) | 61.1 | 36.8 | 21.8 | 10.8 | 31.2 |

| Tourists using overnight accommodations per 1000 resi-dents | 957.5 | 478.1 | 267.6 | 282 | 447.7 |

| Area of wild dumps per 100 km2 of total area | 159.1 | 412.6 | 410.1 | 661.5 | 411.2 |

| Total household water consumption per 1 resident (m3) | 126.2 | 29.5 | 33.8 | 35.6 | 31.5 |

| Total waste per 1 resident (kg) | 247.3 | 243.4 | 244.2 | 264.1 | 247.5 |

| Users of water supply system in total population (%) | 81.5 | 85.6 | 88.3 | 92.1 | 86.9 |

| Using sewage treatment plants in total population (%) | 47.5 | 45.3 | 42.1 | 45.2 | 44.5 |

| Share of investment expenses of department 901 in total investment expenses (%) | 18.2 | 17.7 | 17.1 | 15.2 | 17.2 |

| Investment expenditures of department 901 per capita (PLN) | 159.6 | 159.9 | 157 | 138.3 | 155.4 |

| Voivodeship | Class I | Class II | Class III | Class IV | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dolnośląskie | 22 | 48 | 40 | 23 | 133 |

| Kujawsko-pomorskie | 16 | 44 | 51 | 16 | 127 |

| Lubelskie | 26 | 69 | 72 | 26 | 193 |

| Lubuskie | 21 | 25 | 22 | 5 | 73 |

| Łódzkie | 11 | 39 | 68 | 41 | 159 |

| Małopolskie | 40 | 63 | 39 | 26 | 168 |

| Mazowieckie | 23 | 87 | 115 | 54 | 279 |

| Opolskie | 6 | 21 | 21 | 20 | 68 |

| Podkarpackie | 30 | 51 | 47 | 15 | 143 |

| Podlaskie | 12 | 34 | 41 | 18 | 105 |

| Pomorskie | 12 | 38 | 35 | 13 | 98 |

| Śląskie | 13 | 38 | 41 | 26 | 118 |

| Świętokrzyskie | 27 | 38 | 24 | 8 | 97 |

| Warmińsko-mazurskie | 27 | 32 | 32 | 9 | 100 |

| Wielkopolskie | 14 | 60 | 82 | 51 | 207 |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 13 | 40 | 29 | 20 | 102 |

| Total | 313 | 727 | 759 | 371 | 2170 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bartkowiak-Bakun, N. Diversification of Rural Development in Poland: Considerations in the Context of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020519

Bartkowiak-Bakun N. Diversification of Rural Development in Poland: Considerations in the Context of Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2025; 17(2):519. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020519

Chicago/Turabian StyleBartkowiak-Bakun, Natalia. 2025. "Diversification of Rural Development in Poland: Considerations in the Context of Sustainable Development" Sustainability 17, no. 2: 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020519

APA StyleBartkowiak-Bakun, N. (2025). Diversification of Rural Development in Poland: Considerations in the Context of Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 17(2), 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020519