Consumer Attitudes, Awareness, and Purchase Behaviour for Certified Mountain Products in Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Certification and Consumer Behavior in Mountain Products: A Brief Literature Review

2.1. Definition and Regulation of Mountain Products

2.2. Literature Background and Research Hypotheses

2.2.1. Impact of Label Awareness on Mountain Product Purchases

2.2.2. Consumers’ Willingness to Pay a Higher Price for Certified Food Products and Sustainable Food Systems Development

2.2.3. Socio-Demographic Determinants of Mountain Product Consumption

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Purpose and Specific Objectives

- OS1: To identify the level of knowledge and understanding of the “mountain product” label among consumers.

- OS2: To examine how consumers’ socio-demographic characteristics influence their consumption habits on the mountain products market (frequency of consumption, preferred products, purchase locations, and criteria guiding their purchasing decisions).

- OS3: To assess consumers’ willingness to pay a higher price for certified mountain products.

- OS4: To assess consumers’ perception of the health benefits resulting from the consumption of certified mountain products.

3.2. Key Variables of the Research

3.3. Sampling and Target Consumers

3.4. Research Tool Design

3.5. Data Collection and Analysis

3.6. Research Hypothesis Validation

Coherence Between Research Topic, Objectives, Hypotheses, and Questionnaire Design

- OS1 is linked to Q6–Q9 (Section II); its achievement supports the validation of H1.

- OS2 is linked to Q10–Q14 (Section III) and Q1–Q5 (Section I); its achievement supports the validation of H1 and H5.

- OS3 is linked to Q14–Q16 (Sections III and IV); its achievement supports the validation of H2 and H3.

- OS4 is linked to Q17 (Section IV); its achievement supports the validation of H4.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. OS1 Achieving: Knowledge, Perception and Attitudes of Mountain Certification

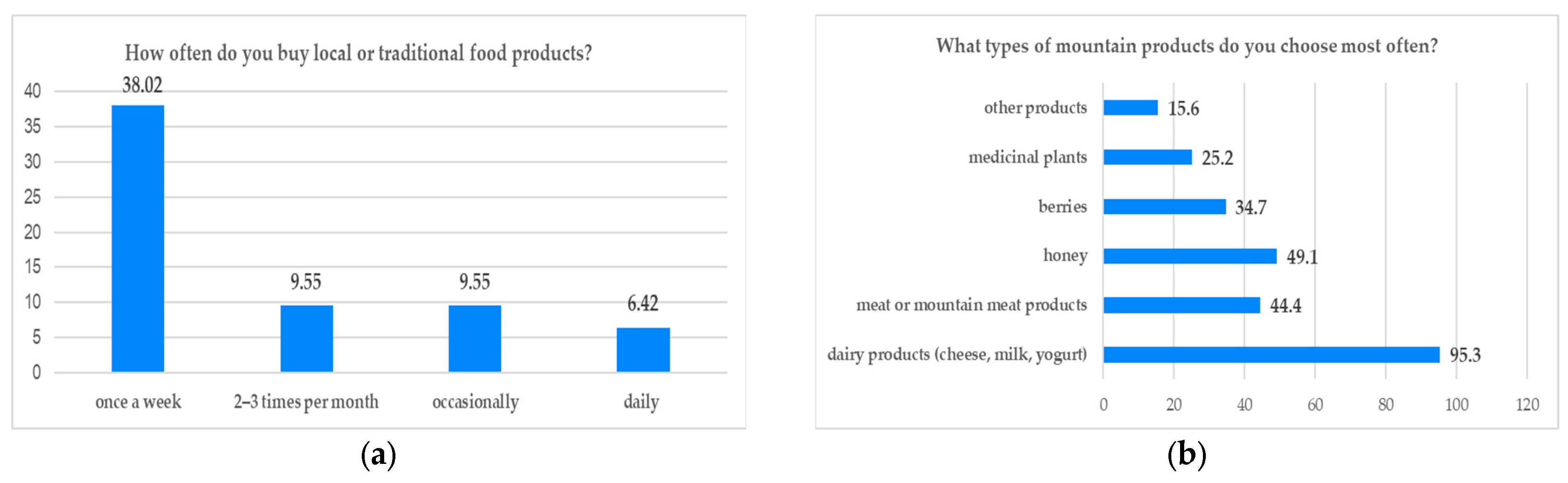

4.3. OS2 Achieving: Shaping Consumption Habits Related to Consumers’ Socio-Demographic Characteristics

4.4. OS3 Achieving: Price and Value Perception

4.5. OS4 Achieving: Consumers’ Attitudes Regarding the Health Benefits Related to the Consumption of Certified Mountain Products

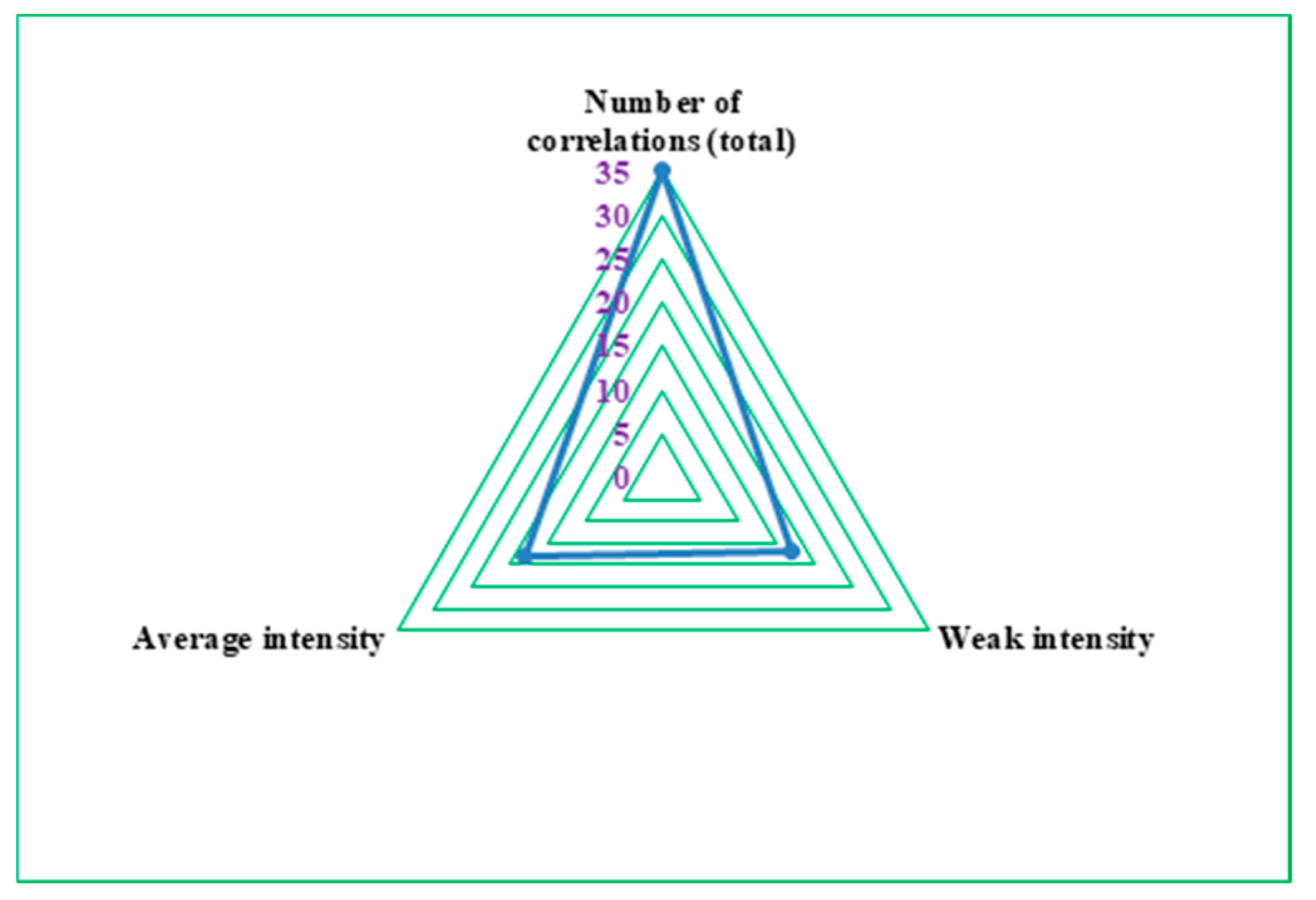

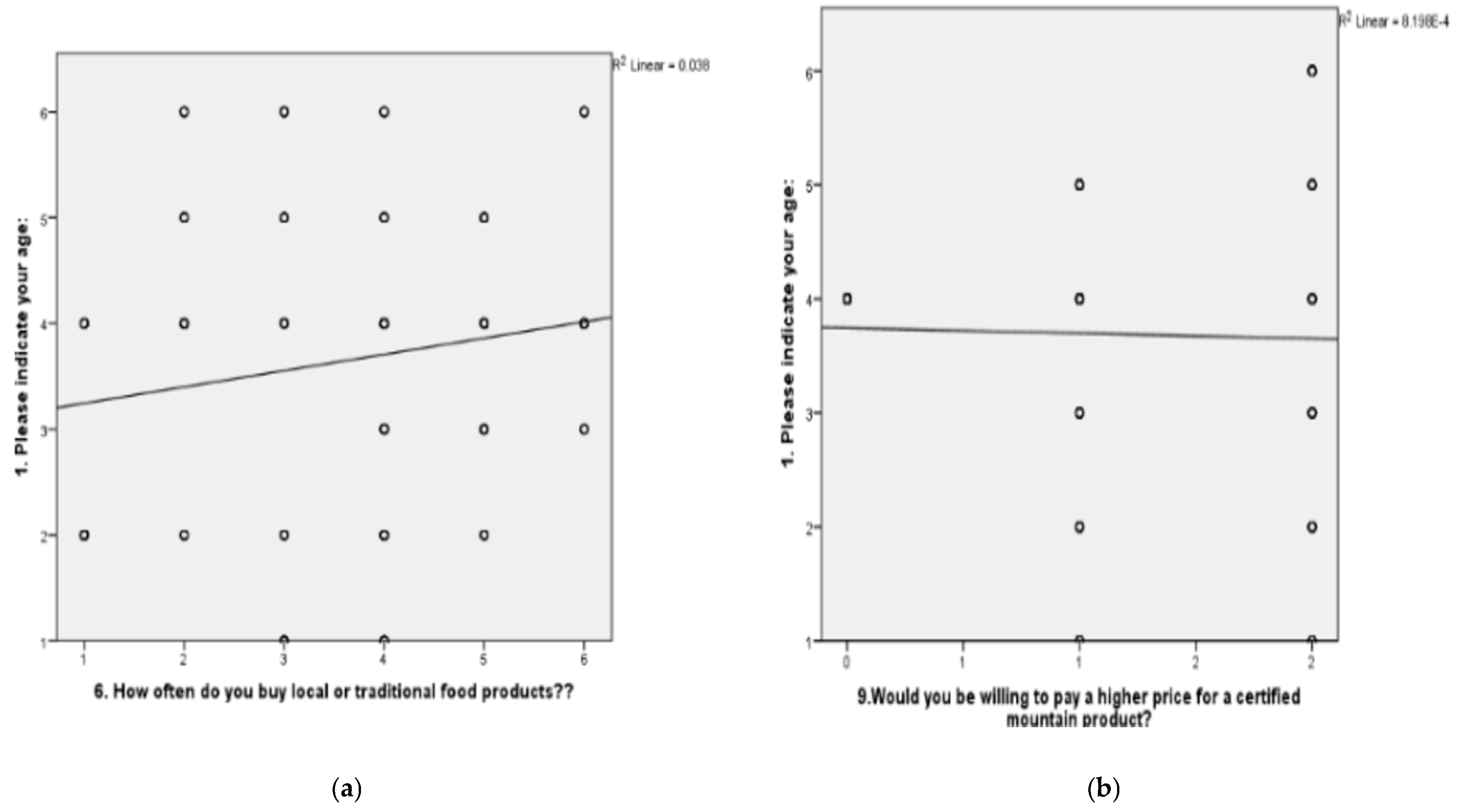

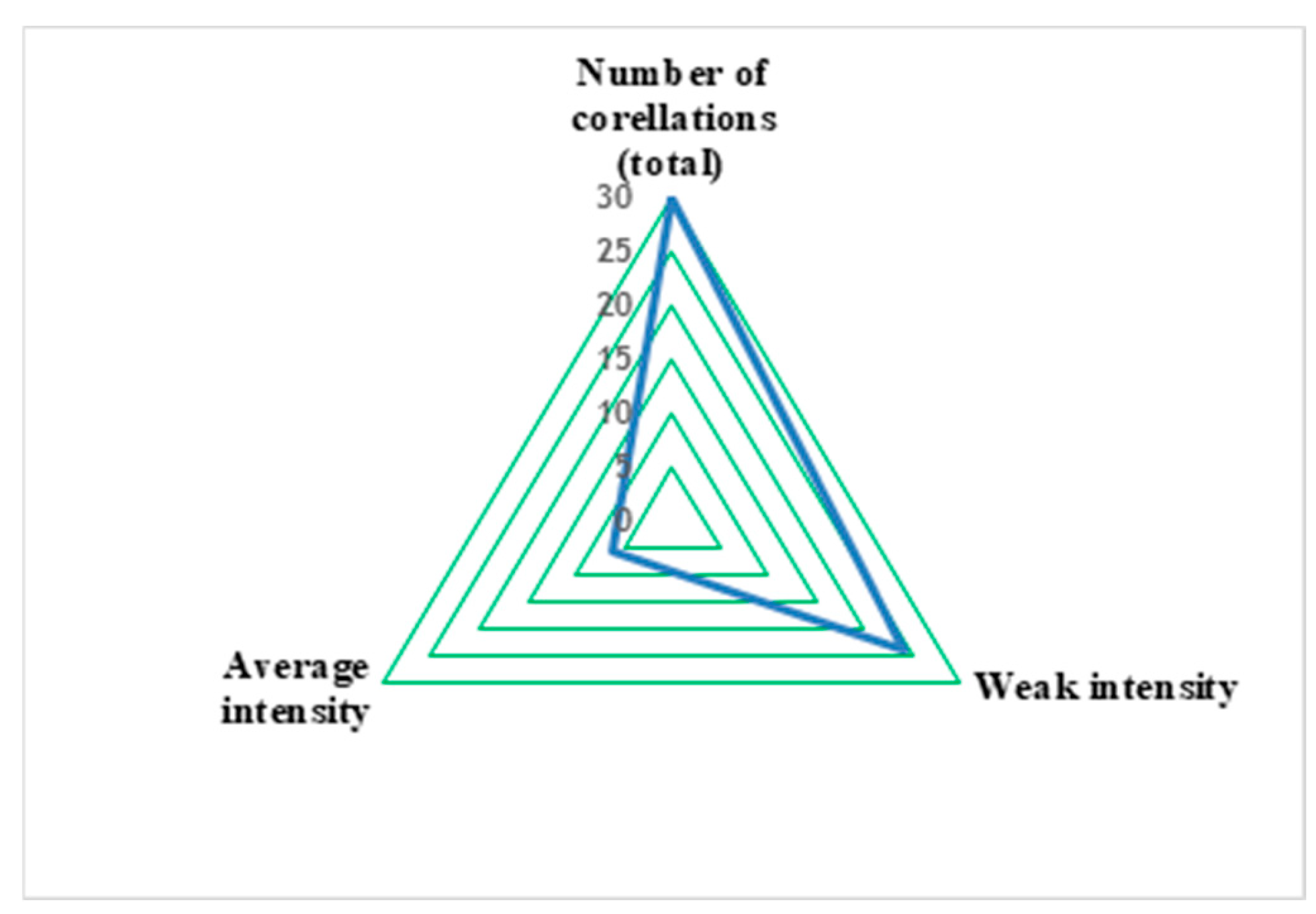

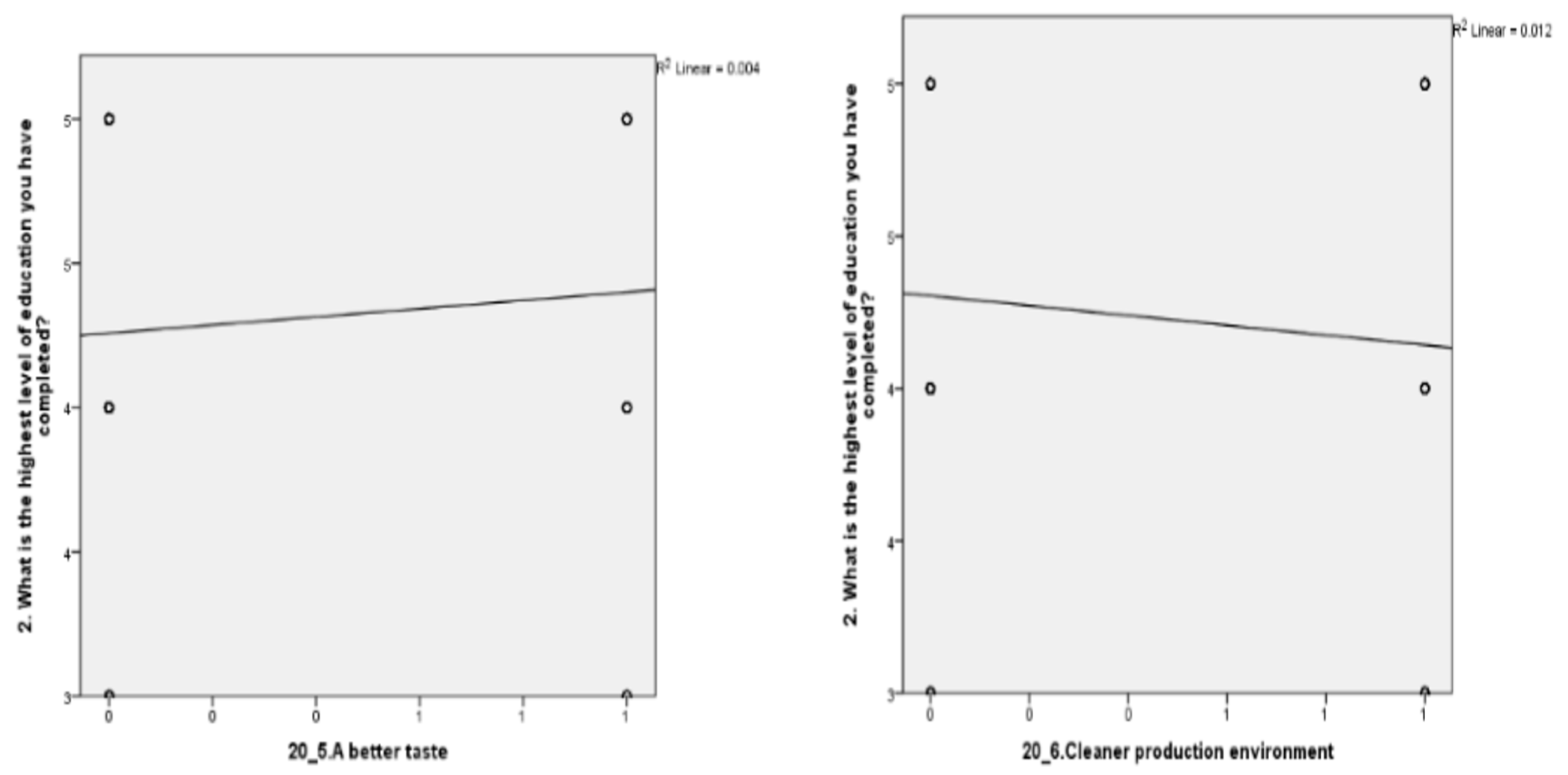

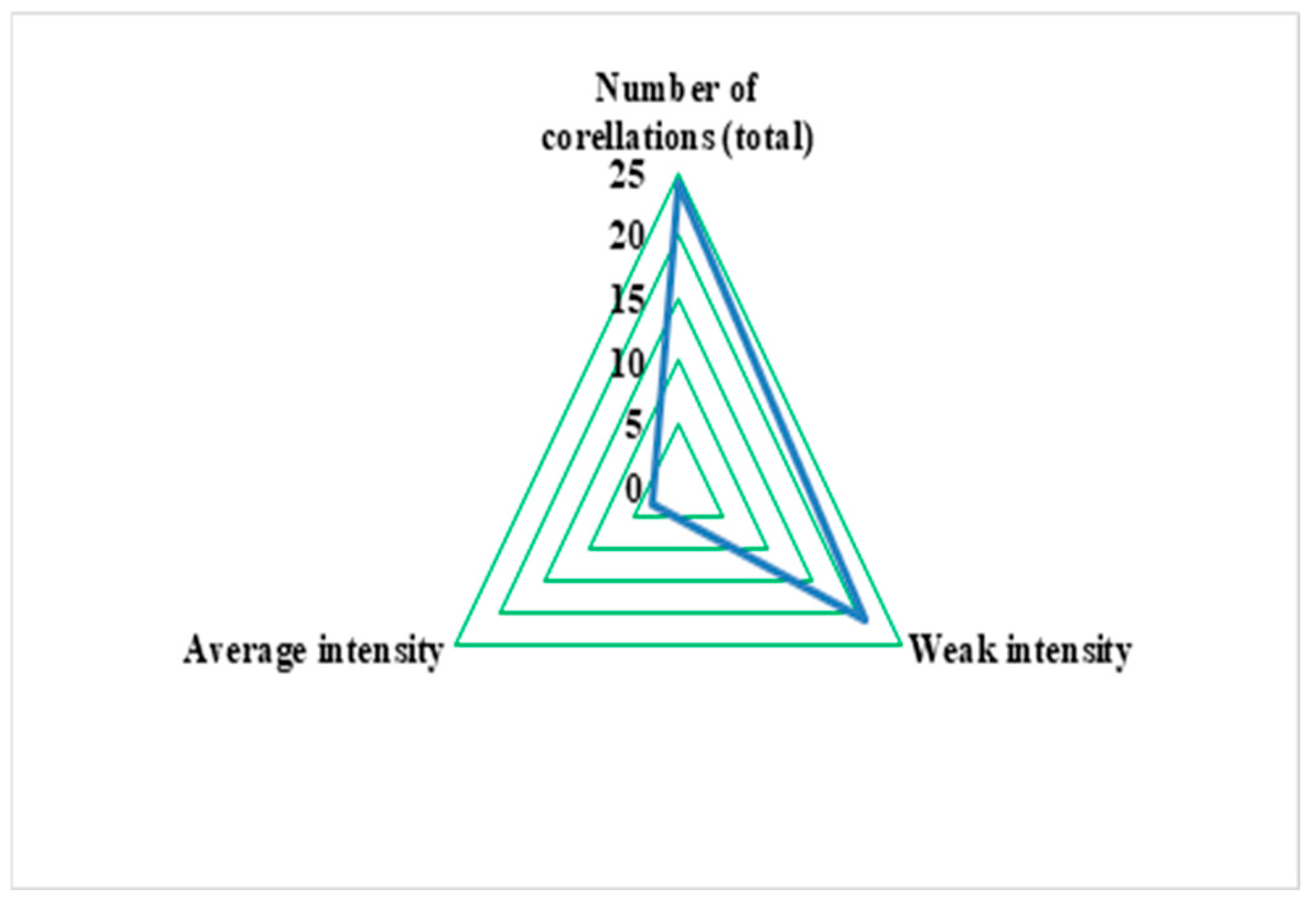

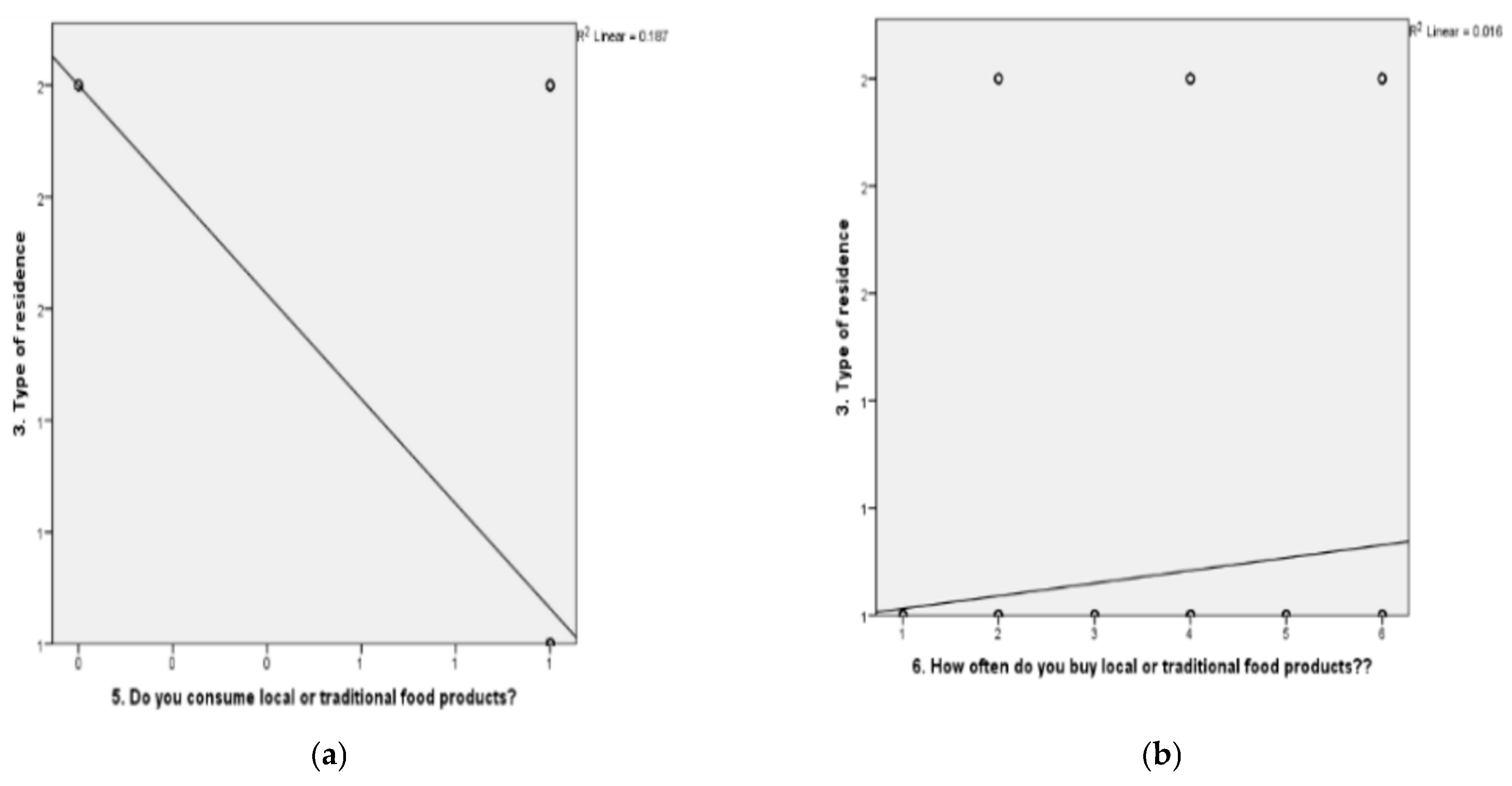

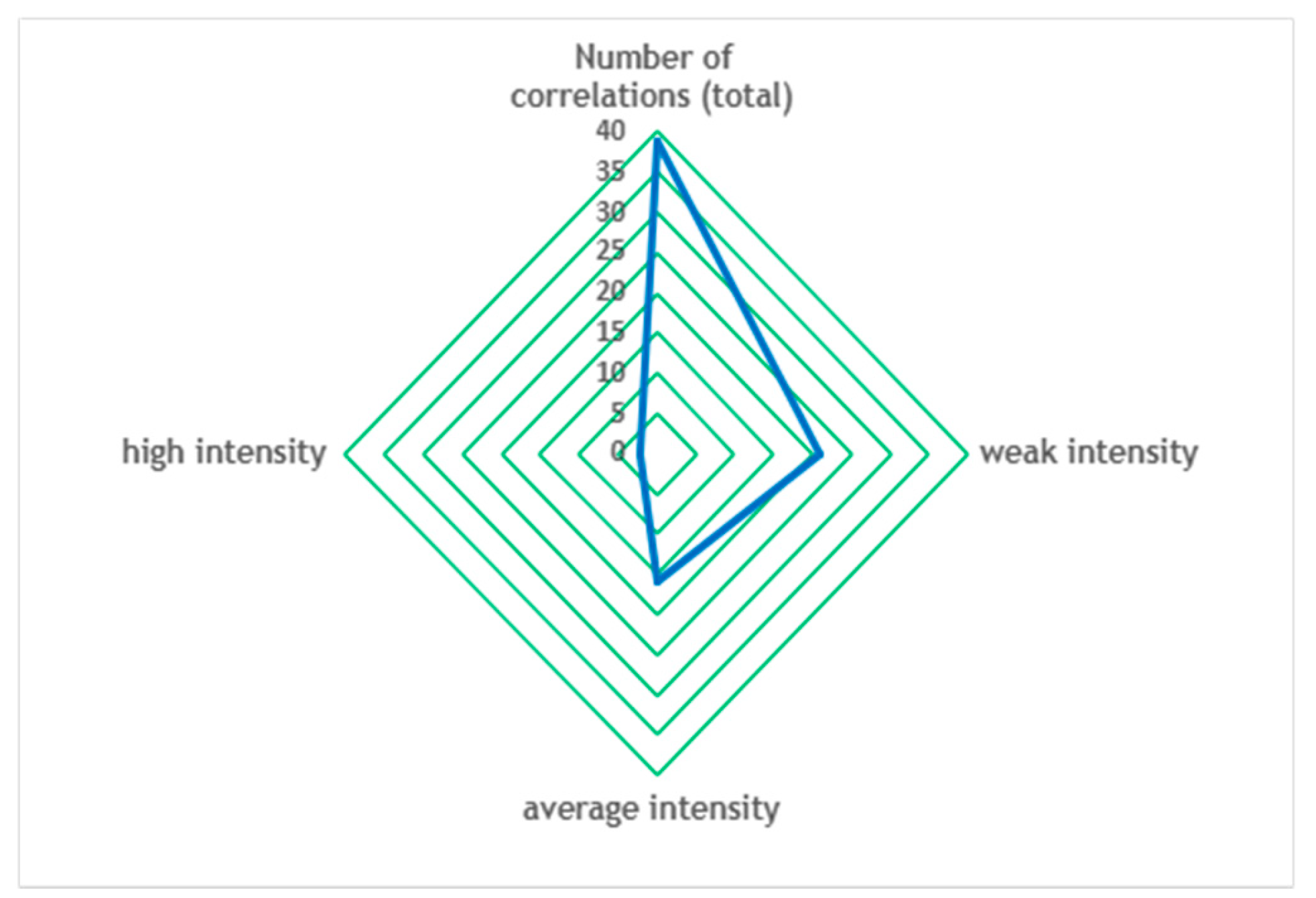

4.6. Correlations Between Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Consumer Behavior, Attitudes, and Perceptions

5. Discussion

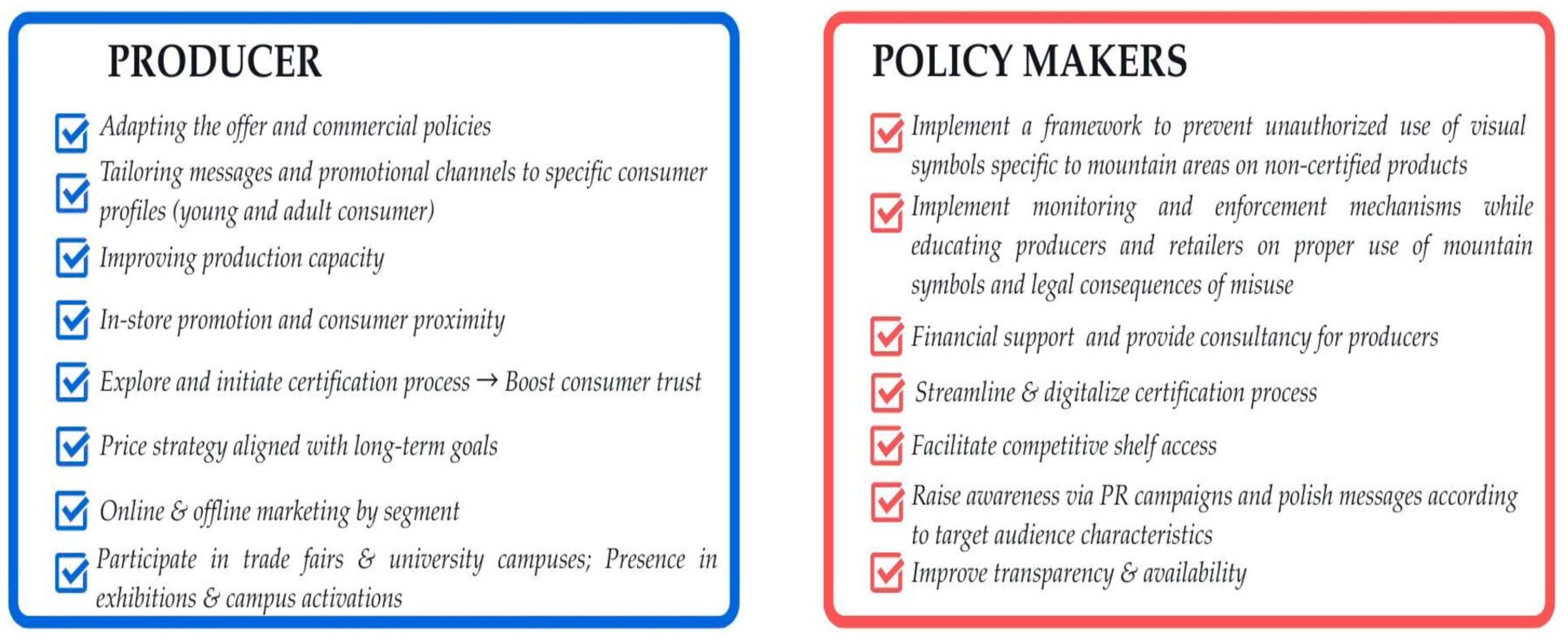

Implications for Policy, Marketing, and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Questionnaire on Consumer Attitudes, Perceptions, and Purchase Intentions Regarding Certified Mountain Products

- Section I. Socio-demographic data

- Q1. You are:

- ☐ male

- ☐ female

- Q2. What is your age?

- ☐ 18–25 years

- ☐ 26–35 years

- ☐ 36–45 years

- ☐ 46–55 years

- ☐ 56–65 years

- ☐ Over 65 years

- Q3. What is your level of education?

- ☐ Primary education

- ☐ Secondary education

- ☐ High school

- ☐ University education

- ☐ Postgraduate education

- Q4. Residence environment:

- ☐ urban

- ☐ rural

- Q5. What is your household’s net monthly income?

- ☐ under 2000 lei

- ☐ 2001–4000 lei

- ☐ 4001–6000 lei

- ☐ 6001–8000 lei

- ☐ over 8000 lei

- Section II. Perception of the “mountain product” certification

- Q6. Have you heard of the “mountain product” label?

- ☐ yes

- ☐ no

- Q7. If so, what do you understand by “mountain product”? ________________

- Q8. Do you consider certified mountain products to be:

- ☐ better in quality

- ☐ the same as the others

- ☐ worse in quality

- ☐ I can’t say

- Q9. Does the label “mountain product” influence your purchasing decision?

- ☐ yes

- ☐ no

- Section III. Consumption habits

- Q10. Do you buy local or traditional food products?

- ☐ yes

- ☐ no

- Q11. How often do you buy local or traditional food?

- ☐ Daily

- ☐ 2–3 times a week

- ☐ Once a week

- ☐ 2–3 times a month

- ☐ Once a month

- ☐ Occasionally

- Q12. What types of mountain products do you choose most often? (choose all that apply)

- ☐ dairy products (cheese, milk, yogurt)

- ☐ meat and meat products

- ☐ honey

- ☐ berries

- ☐ medicinal herbs

- ☐ other products

- Q13. Where do you usually buy certified mountain products?

- ☐ supermarket

- ☐ market

- ☐ directly from the manufacturer

- ☐ online

- ☐ I do not buy certified mountain products

- Q14. Are you willing to pay more for a certified mountain product?

- ☐ yes

- ☐ no

- ☐ don’t know

- Section IV. Price and value perception

- Q15. How do you rate the quality/price ratio of certified mountain products?

- ☐ very good

- ☐ good

- ☐ acceptable

- ☐ poor

- Q16. How much more would you be willing to pay for a similar product without certification?

- ☐ 0–10% more

- ☐ 11–25% more

- ☐ 26–50% more

- ☐ over 50%

- ☐ I am not willing to pay more

- Q17. Do you believe that certified mountain products have health benefits?

- ☐ yes

- ☐ no

- ☐ don’t know

References

- Bernués, A.; Tenza-Peral, A.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Clemetsen, M.; Eik, L.O.; Martín-Collado, D. Targeting best agricultural practices to enhance ecosystem services in European mountains. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duglio, S.; Bonadonna, A.; Letey, M. The Contribution of Local Food Products in Fostering Tourism for Marginal Mountain Areas: An Exploratory Study on Northwestern Italian Alps. Mt. Res. Dev. 2022, 42, R1–R10. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48664426 (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Staffolani, G.; Rahmani, D.; Bentivoglio, D.; Finco, A.; Gil, J.M. The mountain product label: Choice drivers and price premium. Future Foods 2023, 8, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Pedersen, S.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. The impact of organic certification and country of origin on consumer food choice in developed and emerging economies. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 72, 10–30. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0950329318301782 (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A. Agroecology: The Science of Sustainable Agriculture, 2nd ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995; pp. 1–240. [Google Scholar]

- Madududu, P.; Jourdain, D.; Tran, D.; Degieter, M.; Karuaihe, S.; Ntuli, H.; De Steur, H. Consumers’ willingness-to-pay for dairy and plant-based milk alternatives towards sustainable dairy: A scoping review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 51, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Lee, J. Effects of Cultural Background on Consumer Perception and Acceptability of Foods and Drinks: A Review of Latest Cross-Cultural Studies. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 42, 248–256. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214799321001119 (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Banterle, A.; Cereda, E.; Fritz, M. Labelling and sustainability in food supply networks: A comparison between the German and Italian markets. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 769–783. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/bfj/article-abstract/115/5/769/13698/Labelling-and-sustainability-in-food-supply?redirectedFrom=fulltext (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Caputo, V.; Scarpa, R. Methodological Advances in Food Choice Experiments and Modeling: Current Practices, Challenges, and Future Research Directions. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2022, 14, 63–90. Available online: https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-resource-111820-023242 (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, E.; Caputo, V.; Nayga, R.M., Jr.; Banterle, A. Time preferences and food choices: Evidence from a choice experiment. Food Policy 2016, 62, 99–109. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/ (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Council Regulation (EC) No 1257/1999 of 17 May 1999 on Support for Rural Development from the European Agricultural Guidance and Guarantee Fund (EAGGF) and Amending and Repealing Certain Regulations. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A31999R1257 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Santini, F.; Guri, F.; Gómez y Paloma, S. Labelling of Agricultural and Food Products of Mountain Farming; JRC Scientific and Policy Reports, EUR 25768 EN; Joint Research Centre: Luxembourg, 2013; Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Euromontana. European Charter for Mountain Quality Food Products. Version 2016. Available online: https://euromontana.sky-t.bm-services.com (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 November 2012 on Quality Schemes for Agricultural Products and Foodstuffs. Off. J. Eur. Union 2012, L 343, 1–29. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2012/1151/oj/eng (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No 665/2014 of 11 March 2014 Supplementing Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards the Optional Quality Term “Mountain Product”. Off. J.Eur. Union 2014, L 179, 23–25. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2014/665/oj/eng (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: The European Green Deal. COM(2019) 640 final. Brussels, 11 December 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52019DC0640 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System. COM(2020) 381 Final. Brussels, 20 May 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0381 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- European Commission. CAP Strategic Plans—European Commission. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/cap-my-country/cap-strategic-plans_en (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Bassi, I.; Carzedda, M.; Grassetti, L.; Iseppi, L.; Nassivera, F. Consumer attitudes towards the mountain product label: Implications for mountain development. J. Mt. Sci. 2021, 18, 2255–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carzedda, M.; Gallenti, G.; Troiano, S.; Cosmina, M.; Marangon, F.; de Luca, P.; Pegan, G.; Nassivera, F. Consumer Preferences for Origin and Organic Attributes of Extra Virgin Olive Oil: A Choice Experiment in the Italian Market. Foods 2021, 10, 994. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/10/5/994 (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, C. Short food supply chains: Definitions, approaches and indicators. Agric. Econ. Rev. 2017, 18, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Holzapfel, S.; Wollni, M. Is Global GAP Certification of Small-Scale Farmers Sustainable? Evidence from Thailand. J. Dev. Stud. 2014, 50, 731–747. Available online: https://0d1106a8e-y-https-www-tandfonline-com.z.e-nformation.ro/doi/full/10.1080/00220388.2013.874558 (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhifeng, G.; Swisher, M.; Zhao, X. Consumers’ Preferences for Fresh Broccolis: Interactive Effects Between Country of Origin and Organic Labels. 2015. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/agec.12193 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- McMorran, R.; Santini, F.; Guri, F.; Gomez-y-Paloma, S.; Price, M.; Beucherie, O.; Monticelli, C.; Rouby, A.; Vitrolles, D.; Cloye, G. A mountain food label for Europe? The role of food labelling and certification in delivering sustainable development in European mountain regions. J. Alp. Res. Rev. Géogr. Alp. 2015, 103-4, 1–21. Available online: http://rga.revues.org/2654 (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Mountain food products: A broad spectrum of market potential to be exploited. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 67, 12–18. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0924224417302455 (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lamarque, P.; Lambin, E.F. The effectiveness of marked-based instruments to foster the conservation of extensive land use: The case of Geographical Indications in the French Alps. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 706–717. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0264837714002269 (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zanchini, R.; Di Vita, G.; Panzone, L.; Brun, F. What Is the Value of a “Mountain Product” Claim? A Ranking Conjoint Experiment on Goat’s Milk Yoghurt. Foods 2023, 12, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finco, A.; Bentivoglio, D.; Bucci, G. A label for mountain products? Let’s turn it over to producers and retailers. Qual.-Access Success 2017, 18, 198–205. Available online: https://0d10t3uak-y-https-www-webofscience-com.z.e-nformation.ro/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000417405300037 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- National Institute of Statistics (INSSE). TEMPO Online Database. Time Series Populația Rezidentă la 1 Ianuarie, pe Grupe de Vârstă, Sexe și Medii.. Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Voineagu, V.; Ţiţan, E.; Ghiţă, S. Statistică: Baze Teoretice şi Aplicaţii; Editura Economică: Bucuresti, Romania, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mainali, K.; Arion, F.; Rogozan, C. Consumer Understanding and Perception of Mountain Label in the City of Brașov, Romania. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2024, 24, 1. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380465071 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Apetrei, C.I. Review of Mountain Product Quality Scheme in Romania. 2024. Available online: https://www.madr.ro/docs/poca/2024/A9.2-ENG-Mountain-Product-Quality-Scheme.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Ungureanu, D.; Chiran, A.; Leonte, E.; Dona, I.; Vîntu, C.R. Considerations regarding the legislative framework for the development of the mountain area in Romania. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2020, 20, 67. Available online: https://managementjournal.usamv.ro/pdf/vol.20_2/Art67.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Necula, D.; Ungureanu-Iuga, M.; Ognean, L. Beyond the Traditional Mountain Emmental Cheese in “Țara Dornelor”, Romania: Consumer and Producer Profiles, and Product Sensory Characteristics. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379915754 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Renting, H.; Marsden, T.K.; Banks, J. Understanding alternative food networks: Exploring the role of short food supply chains in rural development. Environ. Plan 2023, 35, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, J.; Faria, F. Quest for purposefully designed conceptualization of the country-of-origin image construct. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4411–4420. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0148296316302715 (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Galli, F.; Brunori, G. Short Food Supply Chains as Drivers of Sustainable Development; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T.; Banks, J.; Bristow, G. Food supply chain approaches: Exploring their role in rural development. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumă, I.-S.; Jelea, A.R.; Rodino, S. Organic Agriculture and Products Certified under Quality Schemes in Romania. Ann. Acad. Rom. Sci. Ser. Agric. Silvic. Vet. Med. 2023, 12, 29. Available online: https://aos.ro/wp-content/anale/AVol12Nr2Art.3.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Giampietri, E. The Short Food Supply Chains Phenomenon. Ph.D. Thesis, Universita Politécnica delle Marche, Ancona, Italy, 2015. Available online: https://iris.univpm.it/retrieve/handle/11566/245486/41772/tesi_giampietri.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Hinrichs, C.C. Embeddedness and local food systems: Notes on two types of direct agricultural market. J. Rural Stud. 2000, 16, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilbery, B.; Maye, D. Food supply chains and sustainability: Evidence from specialist food producers. Land Use Policy 2005, 22, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malak-Rawlikowska, A.; Majewski, E.; Wąs, A.; Gołaś, M.; Kłoczko-Gajewska, A.; Borge, S.O.; Coppola, E.; Csillag, P.; de Labarre, M.D.; Freeman, R.; et al. Quantitative Assessment of Economic, Social and Environmental Sustainability of Short Food Supply Chains and Impact on Rural Territories; Deliverable 7.2., Strength2Food Project no. 678024; Strength2Food: Krakow, Poland, 2019; Available online: https://www.strength2food.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/D7.2 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Zulkifli, T.I.N.T.M.; Syahlan, S.; Saili, A.R.; Pahang, J.T.; Ruslan, N.A.; Suyanto, A. Consumer preferences towards goat milk and goat milk products: A mini review. Food Res. 2023, 7, 57–69. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/374184272 (accessed on 29 September 2025). [CrossRef]

| Year | Document | Definition | Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | Art 18. of Regulation (EC) No. 1257/99 [11] | Defines mountain areas as regions with harsh climatic conditions, short vegetation periods, and higher production costs. | Provides the only EU-wide legal definition of mountain areas. |

| 2000 | National measures (Switzerland, France, Italy) [12] | National frameworks to protect the use of “mountain” in product labeling. | Recognize the added value of “mountain product” designation for local product promotion. |

| 2005 | European Charter for Mountain Quality Food Products [13] | European-level voluntary initiative. | Promotes recognition and value of mountain food products. |

| 2012 | Regulation (EU) No. 1151/2012 [14] | Establishes mountain product as an optional quality term reserved for products obtained and processed in mountain areas. | provides the legal framework that defines and protects quality schemes, including the “mountain product,” ensuring traceability, authenticity, and support for the sustainable development of rural and mountain areas. |

| 2014 | Delegated Act (EU) No. 665/2014 [15] | Specifies conditions for use of the term Mountain product. | Operationalizes Regulation 1151/2012; ensures clarity and transparency in labeling. |

| Independent Variable | Category | Sample Distribution (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | 18–25 | 3.3 |

| 26–35 | 16 | |

| 36–45 | 11 | |

| 46–55 | 55.6 | |

| 56–65 | 7.8 | |

| over 65 | 6.3 | |

| Gender | female | 69 |

| male | 31 | |

| Education level | High school | 9.4 |

| University | 54.3 | |

| Postgraduate | 36.3 | |

| Income level (ron) | Under 2000 | 1.6 |

| 2001–4000 | 9.7 | |

| 4001–6000 | 17.5 | |

| 6001–8000 | 25.3 | |

| Over 8000 | 45.8 | |

| Residence | Urban | 92 |

| Rural | 8 | |

| 46–55 | 55.6 | |

| 56–65 | 7.8 | |

| over 65 | 6.3 |

| YES | NO | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of People | Share | Number of People | Share | |

| Have you heard of the “mountain product” label? (Q6) | 512 | 88.89% | 64 | 11.11% |

| Does the “mountain product” label influence the purchasing decision? (Q9) | 55 | 9.55% | 521 | 90.45% |

| Profile Characteristics | Consumer | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A | B* | ||

| Awareness | Mountain product/certified mountain product concepts | 4 | 3 |

| Importance for sustainable agricultural practices, biodiversity conservation, and the development of rural communities | 4 | 3 | |

| The positive impact on the environment and public health | 4 | 3 | |

| Attitudes | Value intrinsic aspects (traditionalism, environmental concern, interest in support for local economy) | 4 | 3 |

| Perceptions | Associate certified mountain products with naturalness, authenticity, and healthier lifestyles | 5 | 3 |

| Behavior | Consumers prioritize price when selecting food products | 3 | 5 |

| Willingness to pay a premium price for certified mountain products | 4 | 2 | |

| Preference for buying from supermarkets | 2 | 4 | |

| The extent to which socio-demographic characteristics influence the selection of profile products: | |||

| age | 4 | 3 | |

| gender | 4 | 5 | |

| education level | 4 | 2 | |

| income level | 3 | 5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marin, A.; Rodino, S.; Pop, R.-E.; Dragomir, V.; Butu, M. Consumer Attitudes, Awareness, and Purchase Behaviour for Certified Mountain Products in Romania. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8950. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198950

Marin A, Rodino S, Pop R-E, Dragomir V, Butu M. Consumer Attitudes, Awareness, and Purchase Behaviour for Certified Mountain Products in Romania. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8950. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198950

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarin, Ancuța, Steliana Rodino, Ruxandra-Eugenia Pop, Vili Dragomir, and Marian Butu. 2025. "Consumer Attitudes, Awareness, and Purchase Behaviour for Certified Mountain Products in Romania" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8950. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198950

APA StyleMarin, A., Rodino, S., Pop, R.-E., Dragomir, V., & Butu, M. (2025). Consumer Attitudes, Awareness, and Purchase Behaviour for Certified Mountain Products in Romania. Sustainability, 17(19), 8950. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198950