Corporate Dual-Organizational Performance and Substantive Green Innovation Practices: A Quasi-Natural Experiment Analysis Based on ESG Rating Events

Abstract

1. Introduction

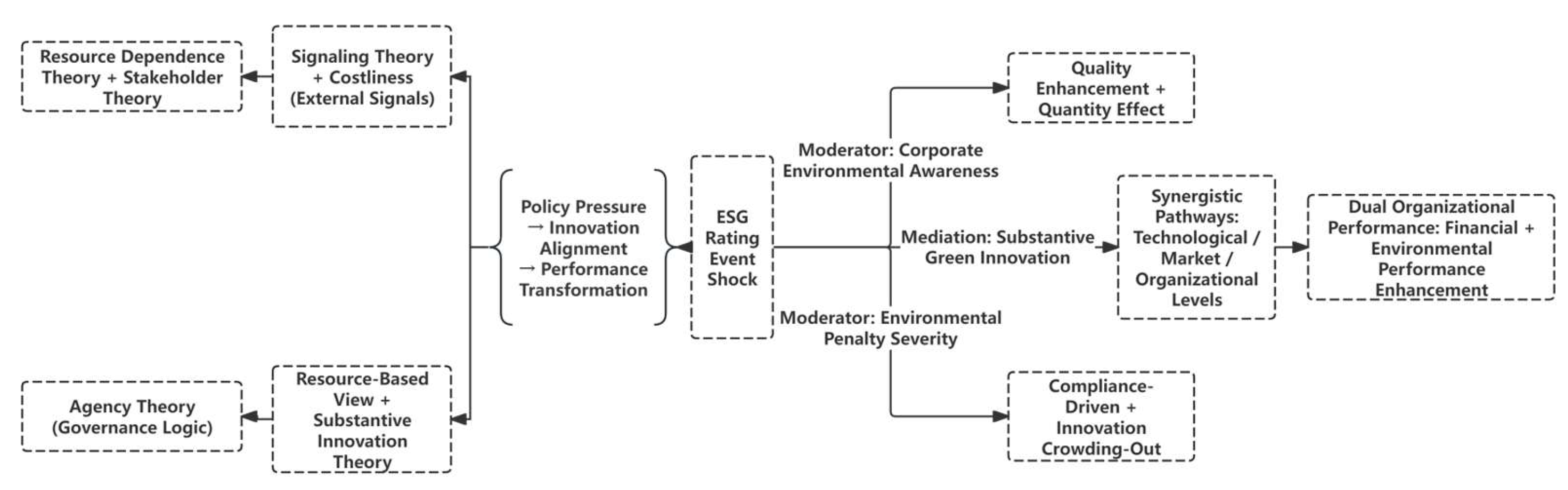

2. Research Hypotheses

2.1. ESG Ratings and Corporate Dual-Organizational Performance

2.2. Mediating Mechanism of Substantive Green Innovation

2.3. Moderating Mechanism of Corporate Environmental Awareness and Environmental Penalty Intensity

3. Model Setup and Indicator Selection

3.1. Sample Selection

3.2. Variable Definitions

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variable

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.3. Model Construction

4. Empirical Analysis and Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Multi-Period Difference-in-Differences Test

4.4. Robustness Test

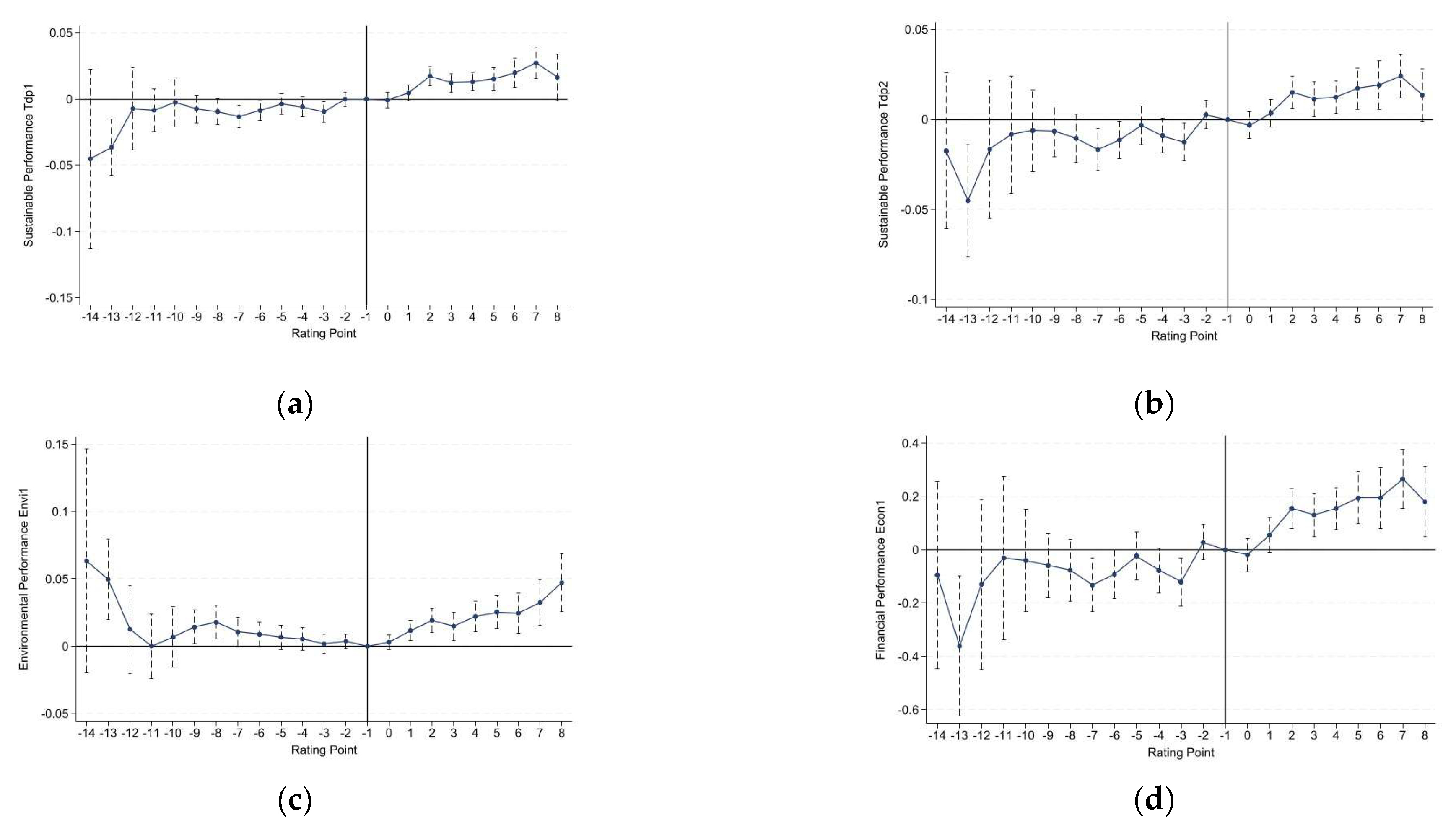

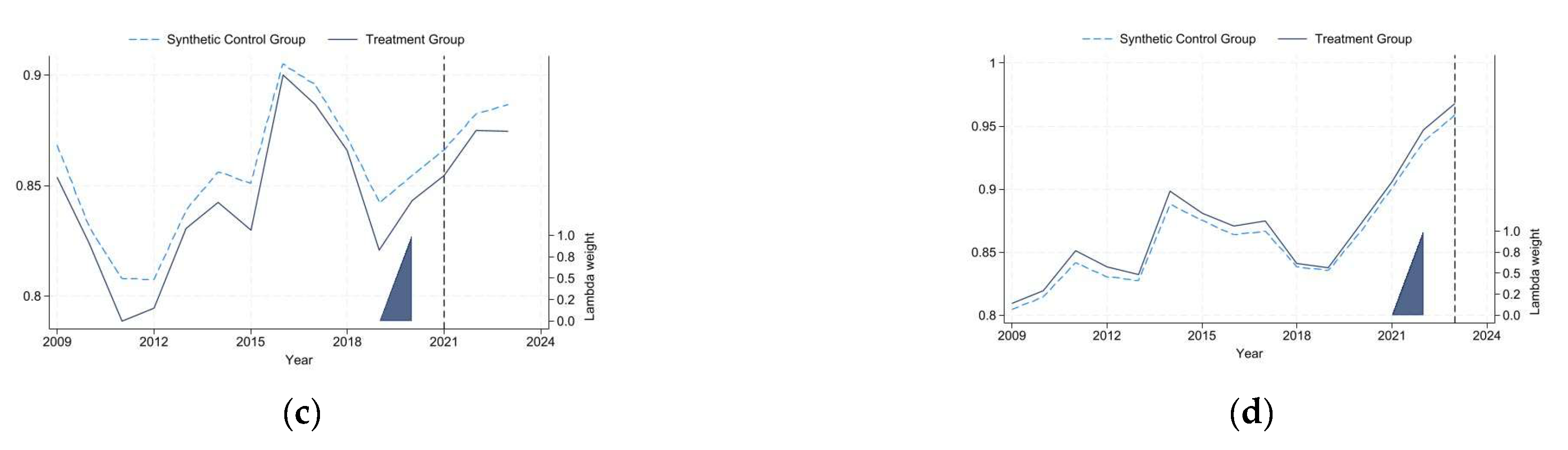

4.4.1. Parallel Trend Test

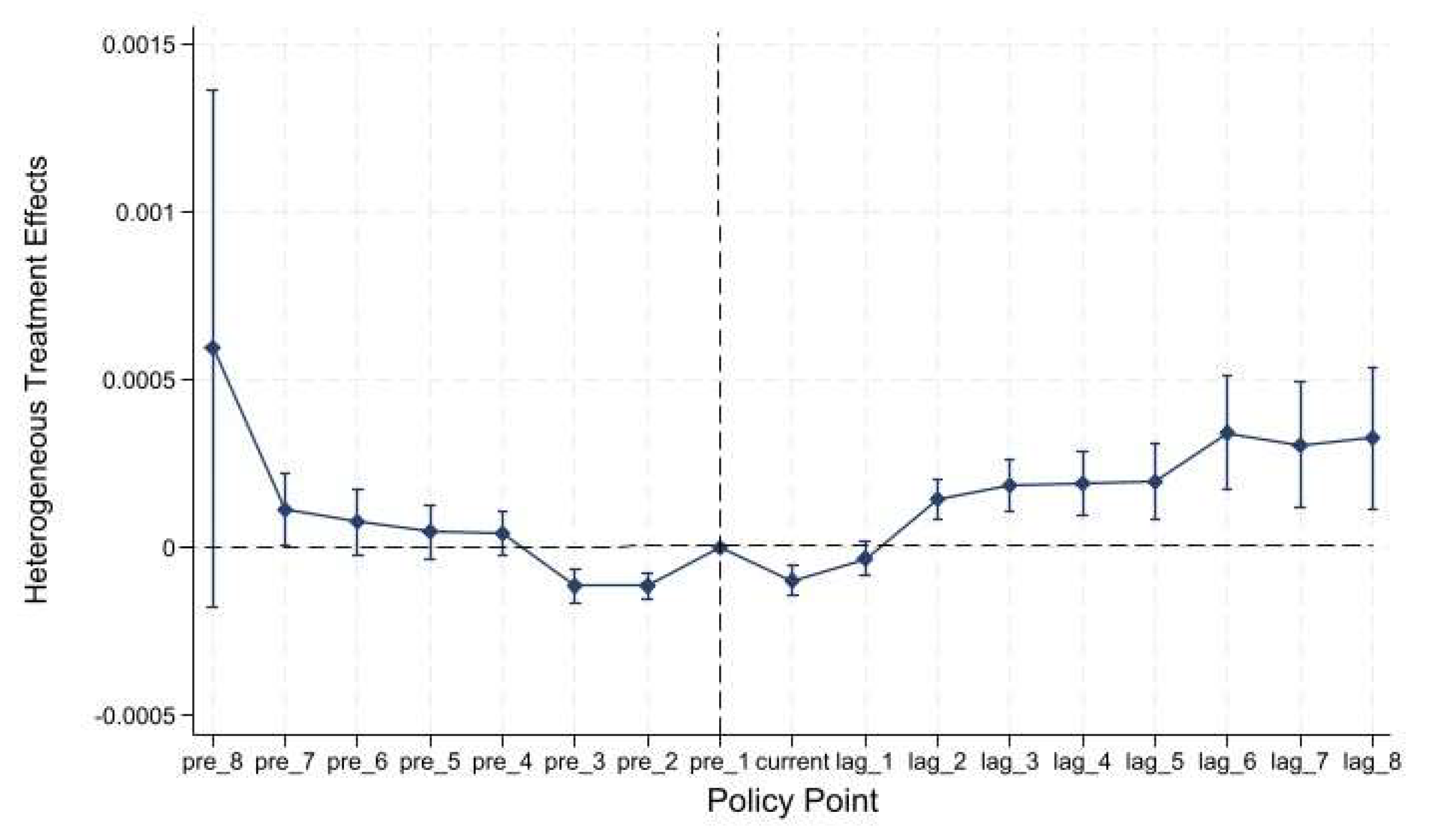

4.4.2. Heterogeneous Treatment Effects

4.4.3. Other Robustness Tests

5. Conditional Mediation Model

5.1. Path Analysis

5.2. Further Analysis

5.3. Path Testing

6. Heterogeneity Analysis

6.1. ESG Rating Discrepancy

6.2. Ownership Structure

6.3. Corporate Life Cycle

7. Discussion, Conclusions, and Policy Recommendations

7.1. Discussion

7.2. Conclusions

7.3. Policy Recommendations

7.3.1. Encouraging the Integration of Green Patent Quality Assessment into the ESG Evaluation System

7.3.2. Adopting a “Dual Incentive-Constraint” Policy Tool to Regulate Environmental Behavior

7.3.3. Developing Differentiated Policies Based on Business Attributes

7.3.4. Building a Dynamic, Interactive Feedback System Through Sustainable Development

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Data Collection and Processing Procedure

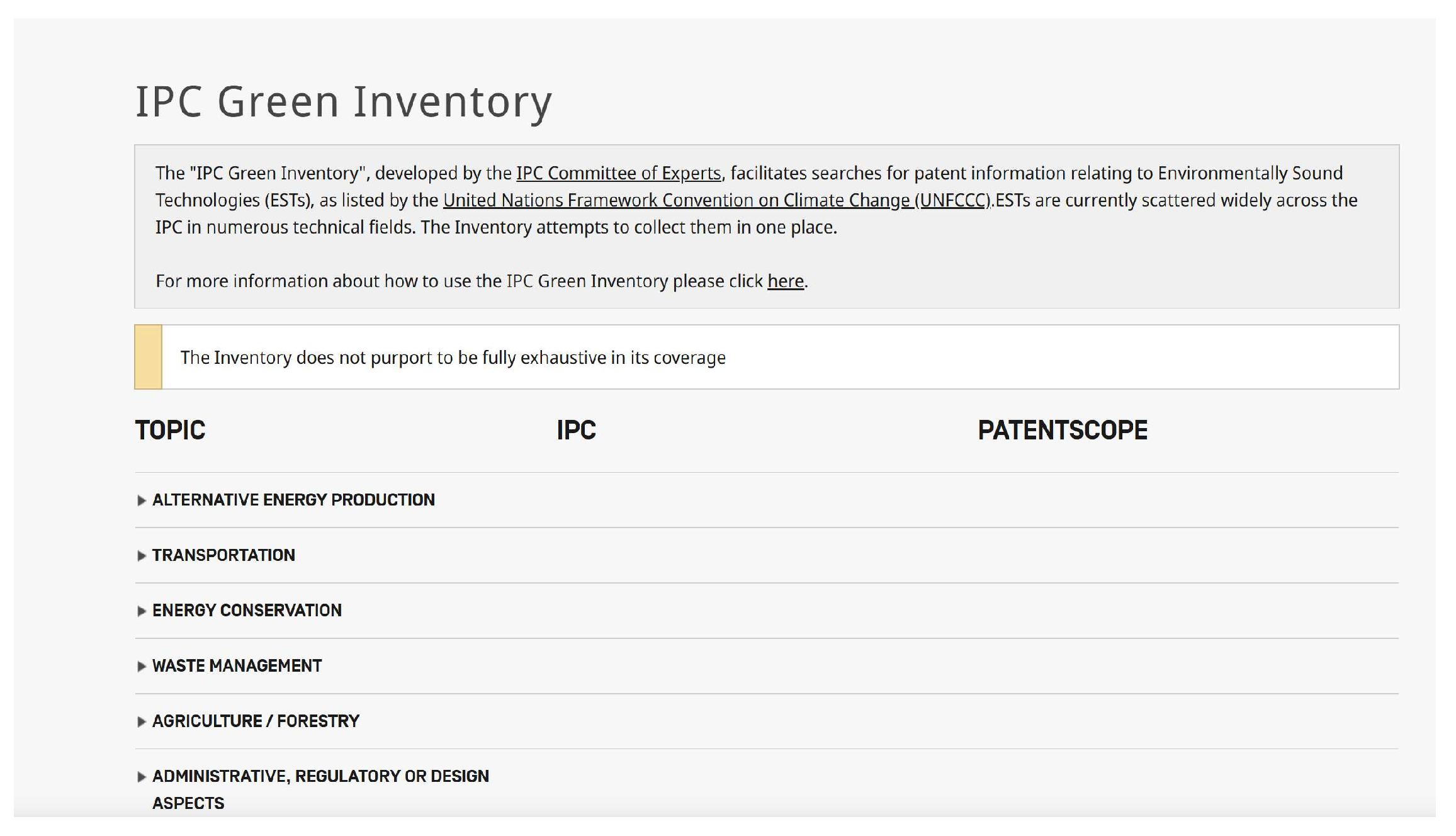

Appendix A.1. Patent Data from WIPO IPC Green Inventory

Appendix A.2. Patent Data from CNIPA

Appendix A.3. Cross-Validation Using CNRDS Green Patent Research Database

Appendix A.4. Firm-Level Financial Data and Control Variables

References

- Hojnik, J.; Ruzzier, M. The driving forces of process eco-innovation and its impact on performance: Insights from Slovenia. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 812–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, A.; Glaum, M.; Kaiser, S. ESG Performance and Firm Value: The Moderating Role of Disclosure. Glob. Financ. J. 2018, 38, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Pavelin, S. Building a Good Reputation. Eur. Manag. J. 2004, 22, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Gurun, U.G.; Nguyen, Q.H. The ESG-Innovation Disconnect: Evidence from Green Patenting; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Berrone, P.; Fosfuri, A.; Gelabert, L.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Necessity as the Mother of ‘Green’ Inventions: Institutional Pressures and Environmental Innovations. Strategy Manag. J. 2013, 34, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Yu, Q. The Impact of Senior Management’s Background Characteristics on Corporate Substantive Green Innovation. Res. Financ. Econ. 2017, 6, 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and Financial Performance: Aggregated Evidence from More Than 2000 Empirical Studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.W.; Li, Y.H. Green Innovation and Performance: The View of Organizational Capability and Social Reciprocity. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wang, S.-P.; Liu, D. A Degradation Modeling Method Based on Artificial Neural Network Supported Tweedie Exponential Dispersion Process. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.T.; Freeman, J. Structural Inertia and Organizational Change. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1984, 49, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meckling, W.H.; Jensen, M.C. Theory of the Firm. Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G. External Control of Organizations—Resource Dependence Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 355–370. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun, C.; Shanley, M. What’s in a Name? Reputation Building and Corporate Strategy. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS Procedures for Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, A.; Fooladi, I.; Tehranian, H. Valuation Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bank. Financ. 2015, 59, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.F.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. Rev. Financ. 2022, 26, 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, X. The Correlation between ESG Performance and Corporate Financing Costs. China Certif. Public Account. 2022, 9, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, M. Competitive and Optimal Responses to Signals: An Analysis of Efficiency and Distribution. J. Econ. Theory 1974, 7, 296–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Corporate Social Responsibility Information Disclosure and Innovation Performance—Empirical Study of Chinese Listed Companies in the ‘Mandatory Disclosure Era’. Stud. Sci. Sci. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2021, 42, 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Xiao, Z. Heterogeneous Environmental Regulation Tools and Corporate Substantive Green Innovation Incentives—Evidence from Green Patents of Listed Companies. Econ. Res. 2020, 55, 192–208. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Linde, C. Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, R.; Hinze, A.K.; Hardeck, I. Impact of ESG Factors on Firm Risk in Europe. J. Bus. Econ. 2016, 86, 867–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seman, N.A.A.; Govindan, K.; Mardani, A.; Zakuan, N.; Saman, M.Z.M.; Hooker, R.E.; Ozkul, S. The Mediating Effect of Green Innovation on the Relationship Between Green Supply Chain Management and Environmental Performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T. Mediation and Moderation Effects in Causal Inference Empirical Research. China Ind. Econ. 2022, 5, 100–120. [Google Scholar]

- El Ghoul, S.; Guedhami, O.; Kwok, C.C.Y.; Mishra, D.R. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Affect the Cost of Capital? J. Bank. Financ. 2011, 35, 2388–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Shen, H.; Zhou, Y. Client Enterprise Digitization, Supplier Enterprise ESG Performance, and Sustainable Development of Supply Chains. Econ. Res. 2024, 59, 54–73. [Google Scholar]

- Aboud, A.; Diab, A. The Financial and Market Consequences of Environmental, Social, and Governance Ratings: The Implications of Recent Political Volatility in Egypt. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2019, 10, 498–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, M.A.; Nieswiadomy, M.L. Environmental Kuznets Curve: Threatened Species and Spatial Effects. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 55, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atan, R.; Alam, M.M.; Said, J.; Zamri, M. The Impacts of Environmental, Social, and Governance Factors on Firm Performance: Panel Study of Malaysian Companies. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2018, 29, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business Models and Dynamic Capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, C.L.; Ritter, T.; Di Benedetto, C.A. Managing through a Crisis: Managerial Implications for Business-to-Business Firms. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 88, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WIPO. IPC Green Inventory. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/classifications/ipc/green-inventory/home (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA Green Innovation Special Topic). Available online: https://english.cnipa.gov.cn/ (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Xi, L.; Zhao, H. Dual Environmental Awareness of Executives, Substantive Green Innovation, and Corporate Dual Organizational Performance. Econ. Manag. 2022, 44, 139–158. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Zhu, Q. How Can Corporate Green Innovation Practices Solve the Dilemma of “Harmonious Coexistence”? Manag. World 2021, 37, 128–149. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Guo, L. Does Digital Transformation Improve Corporate ESG Responsibility Performance? Foreign Econ. Manag. 2023, 45, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, D. The Impact Mechanism of Patent Quality on Corporate Export Competitiveness: An Investigation from the Knowledge Width Perspective. World Econ. Res. 2021, 1, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Drempetic, S.; Klein, C.; Zwergel, B. The Influence of Firm Size on the ESG Score: Corporate Sustainability Ratings Under Review. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 167, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D.; Hail, L.; Leuz, C. Adoption of CSR and Sustainability Practices in Emerging Markets: Evidence from Corporate Governance and Institutions. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 132, 93–122. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, R. ESG Rating Disagreement and Corporate Green Innovation Bubbles: Evidence from Chinese A-Share Listed Firms. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 95, 103495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Chaisemartin, C.; d’Haultfoeuille, X. Two-way Fixed Effects Estimators with Heterogeneous Treatment Effects. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 2964–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, N. Green innovation, digital transformation, and carbon emission reduction performance of energy-intensive enterprises. J. Manag. Eng. 2023, 37, 66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Liu, Q.; Tang, D. Carbon performance, quality of carbon information disclosure, and cost of equity financing. Manag. Rev. 2019, 31, 221–235. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Fan, M.; Fan, Y. The Impact of ESG Ratings under Market Soft Regulation on Corporate Green Innovation: An Empirical Study from Informal Environmental Governance. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1278059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhu, C.; Albitar, K. ESG ratings and green innovation: U-shaped journey towards sustainable development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 4108–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Lin, S.; Cui, J. Can Environmental Rights Trading Markets Induce Substantive Green Innovation?—Evidence from Green Patent Data of Listed Companies in China. Econ. Res. 2018, 53, 129–143. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Dimension | Measurement Method | Data Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Dual Organizational Performance (Tdp) | Financial Performance (Econ) Environmental Performance (Evir) | Tobin’s Q Index | CSMAR Database |

| Log of Hexun Environmental Score | Wind Database | |||

| Independent Variable | ESG Rating (ESG) | Grouping and Time Dummy Variable | The ESG policy time shock is measured using the interaction term (Treat × Post) to capture the policy’s impact after implementation | Shang Dao Rong LV Rating Agency |

| Mediating Variable | Substantive Green Innovation (Inno) | Green Patent Authorization Quantity (Green) Green Patent Application Quantity (Green1) Green Patent Authorization Citation Quality (Anuctd) | Database Results Correcting and Comparing | CNRDS Database, CSMAR Database, National Intellectual Property Office Patent Database |

| Moderating Variables | Corporate Environmental Awareness (Sum) | Scoring is based on the disclosure of keywords such as Environmental Concepts, Goals, Management Systems, Education, Special Actions, Emergency Mechanisms, Honors, and ‘Three Simultaneities’ (0/1/2 for No/Qualitative/Quantitative Disclosure) | 2009–2023 Listed Companies’ CSR Reports, Sustainability Reports | |

| Environmental Penalty Intensity (Pub) | The ratio of environmental penalty cases at the prefecture-level city to local sulfur dioxide emissions is used to measure government penalty intensity | Peking University Lawbao Judicial Case Search System for annual environmental penalty cases at the prefecture-level cities | ||

| ESG Rating Discrepancy (ESGU) | Standardized treatment of annual company ESG rankings, deviation average of any two rating agencies’ ranking combinations | Hua Zheng, Wind, FTSE Russell, Meng Lang, Shang Dao Rong LV, and MSCI Rating Agencies | ||

| Control Variables | Firm Size (Size) | Natural logarithm of total market value | CSMAR Database | |

| Book-to-Market Ratio (BM) | Net assets/total market value | |||

| Cash Ratio (Cash) | Net cash flow from operating activities/total assets | |||

| Institutional Investor Ownership (Inst) | Number of shares held by institutional investors/total shares | |||

| Ownership Concentration (Top10) | Number of shares held by the top 10 shareholders/total shares | |||

| Capita Sales (Psale) | Sales revenue/number of employees | |||

| Variable | Sample Size | Mean | Standard Deviation | Min Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Treatment Group | Control Group | ||||

| ESG | 34,135 | 0.153 | 1 | 0 | 0.36 | 0 |

| Tdp1 | 34,135 | 0.133 | 0.142 | 0.116 | 0.123 | −0.567 |

| Envi1 | 34,135 | 3.998 | 4.166 | 3.967 | 0.688 | 0 |

| Econ | 34,135 | 2.055 | 1.844 | 2.094 | 1.433 | 0.83 |

| Green | 34,107 | 1.697 | 7.613 | 0.629 | 15.026 | 0 |

| Green1 | 34,107 | 3.195 | 11.575 | 1.682 | 16.576 | 0 |

| Anuctd2 | 34,135 | 0.387 | 0.875 | 0.299 | 0.964 | 0 |

| Regu1 | 26,045 | 0.255 | 0.217 | 0.261 | 0.099 | −2.095 |

| Media | 33,233 | 0.347 | 0.517 | 0.316 | 0.428 | −1 |

| Size | 34,135 | 0.223 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.014 | 0.194 |

| BM | 34,135 | 0.629 | 0.724 | 0.612 | 0.257 | 0.104 |

| Cash | 34,135 | 0.85 | 0.595 | 0.895 | 1.491 | 0.013 |

| Inst | 34,135 | 0.452 | 0.571 | 0.43 | 0.24 | 0.003 |

| Top10 | 34,135 | 0.564 | 0.602 | 0.557 | 0.157 | 0.214 |

| Gdp | 29,518 | 1.017 | 1.274 | 0.97 | 0.473 | 0.052 |

| Psale | 34,135 | 0.139 | 0.143 | 0.138 | 0.009 | 0.118 |

| Tdp1 | DID | Envi4 | Econ1 | Regu1 | Media | ESGU | Size | BM | Cash | Inst | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | 0.085 ** | ||||||||||

| Envi4 | 0.326 ** | 0.034 ** | |||||||||

| Econ1 | 0.049 ** | −0.063 ** | −0.056 ** | ||||||||

| Regu1 | 0.018 ** | −0.151 ** | 0.070 ** | 0.052 ** | |||||||

| Media | 0.062 ** | 0.170 ** | −0.013 * | −0.087 ** | −0.187 ** | ||||||

| ESGU | 0.140 ** | 0.092 ** | 0.201 ** | −0.115 ** | 0.052 ** | 0.064 ** | |||||

| Size | 0.034 ** | 0.534 ** | 0.144 ** | −0.448 ** | −0.106 ** | 0.157 ** | 0.213 ** | ||||

| BM | −0.097 ** | 0.158 ** | 0.059 ** | −0.795 ** | −0.067 ** | 0.088 ** | 0.103 ** | 0.593 ** | |||

| Cash | 0.171 ** | −0.073 ** | 0.063 ** | 0.116 ** | 0.020 ** | −0.058 ** | 0.054 ** | −0.244 ** | −0.156 ** | ||

| Inst | 0.119 ** | 0.212 ** | 0.151 ** | −0.074 ** | 0.060 ** | −0.005 | 0.084 ** | 0.419 ** | 0.164 ** | −0.091 ** | |

| Top10 | 0.204 ** | 0.105 ** | 0.143 ** | −0.146 ** | 0.050 ** | −0.013 * | 0.142 ** | 0.201 ** | 0.169 ** | 0.135 ** | 0.550 ** |

| Gdp | −0.012 * | 0.232 ** | −0.054 ** | −0.046 ** | −0.357 ** | 0.164 ** | 0.060 ** | 0.179 ** | 0.078 ** | −0.040 ** | −0.082 ** |

| Psale | 0.058 ** | 0.218 ** | 0.102 ** | −0.216 ** | −0.124 ** | 0.072 ** | 0.077 ** | 0.442 ** | 0.313 ** | −0.163 ** | 0.189 ** |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tdp1 | Envi | Econ | Tdp1 | Envi | Econ | Tdp1 | Envi | Econ | |

| ESG | 0.015 *** | 0.128 *** | 0.158 *** | ||||||

| (0.002) | (0.036) | (0.028) | |||||||

| ESG_S | 0.001 *** | 0.023 *** | 0.001 | 0.001 *** | 0.023 *** | 0.005 *** | |||

| (0.000) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.002) | (0.002) | ||||

| ESGU | −0.016 *** | 0.082 * | −0.155 *** | ||||||

| (0.003) | (0.048) | (0.037) | |||||||

| w1 | 0.000 | −0.006 ** | 0.011 ** | ||||||

| (0.000) | (0.003) | (0.005) | |||||||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 29,494 | 29,494 | 29,494 | 28,258 | 28,258 | 28,258 | 28,258 | 28,258 | 28,258 |

| R-squared | 0.778 | 0.423 | 0.800 | 0.789 | 0.406 | 0.797 | 0.789 | 0.406 | 0.797 |

| Year dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Variable | Tdp1 | Tdp2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| SDID | 0.03339 *** | 0.02490 *** | 0.02098 *** | 0.02119 *** |

| (0.00514) | (0.00528) | (0.00221) | (0.00235) | |

| Controls | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Firm dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm weights | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year weights | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry weights | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (3) | (4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV1: Female Executives | V1: Financial Background | V2: Policy Shock | Substitute Variables | Lag Effects | |||||

| First Stage | Second Stage | First Stage | Second Stage | First Stage | Second Stage | ||||

| ESG | Tdp1 | ESG | Tdp1 | ESG | Tdp1 | Tdp2 | Tdp1_w | ||

| IV1 | 0.076 *** | 0.083 *** | 0.0412 ** | ||||||

| (0.012) | (0.021) | (0.017) | |||||||

| ESG | 0.122 ** | 0.387 *** | 0.0815 ** | 0.016 *** | 0.019 *** | ||||

| (0.056) | (0.051) | (0.041) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||

| Controls | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | |

| Year dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Firm dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Number | 26,172 | 26,172 | 26,095 | 26,095 | 28,025 | 28,025 | 29,494 | 21,700 | |

| R-squared | 0.426 | 0.603 | 0.337 | 0.684 | 0.621 | 0.384 | 0.695 | 0.774 | |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tdp1 | Green | Green1 | Anuctd | |

| ESG | 0.015 *** | 14.422 *** | 8.180 *** | 0.354 *** |

| (0.002) | (1.903) | (1.105) | (0.054) | |

| Controls | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Observations | 29,494 | 29,462 | 29,462 | 5509 |

| R-squared | 0.778 | 0.688 | 0.679 | 0.815 |

| (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Sum | −0.001 *** | −0.263 | −0.137 | −0.005 |

| (0.000) | (0.326) | (0.166) | (0.010) | |

| ESG | 0.013 *** | 9.355 *** | 4.263 *** | 0.285 *** |

| (0.003) | (1.520) | (0.810) | (0.059) | |

| Sum-ESG | 0.002 *** | 3.762 *** | 1.952 *** | 0.044 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.763) | (0.436) | (0.016) | |

| Controls | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Observations | 25,581 | 25,557 | 25,557 | 4768 |

| R-squared | 0.794 | 0.740 | 0.738 | 0.825 |

| (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

| Pub | −0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| ESG | 0.016 *** | 6.786 *** | 3.442 *** | 0.197 *** |

| (0.003) | (1.464) | (0.937) | (0.055) | |

| Pub-ESG | 0.000 | 3.204 *** | 2.129 *** | 0.016 |

| (0.001) | (0.880) | (0.622) | (0.018) | |

| Controls | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Observations | 14,242 | 14,227 | 14,227 | 2976 |

| R-squared | 0.792 | 0.753 | 0.738 | 0.841 |

| Year dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bub | bub1 | bub | bub1 | bub | bub1 | |

| DID | 0.240 *** | 0.285 *** | 0.174 *** | 0.208 *** | 0.192 *** | 0.172 *** |

| (0.053) | (0.056) | (0.064) | (0.055) | (0.056) | (0.055) | |

| ESGU | −0.004 | −0.074 | ||||

| (0.052) | (0.050) | |||||

| w8 | 0.778 *** | 0.704 *** | ||||

| (0.262) | (0.239) | |||||

| Sum | −0.018 * | −0.013 | ||||

| (0.009) | (0.011) | |||||

| w10 | 0.053 *** | 0.068 *** | ||||

| (0.020) | (0.021) | |||||

| Pub | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| w9 | 0.045 | 0.062 ** | ||||

| (0.029) | (0.026) | |||||

| Controls | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Observations | 17,342 | 19,077 | 14,080 | 15,664 | 13,945 | 15,186 |

| R-squared | 0.719 | 0.710 | 0.754 | 0.754 | 0.764 | 0.755 |

| Year dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mediators | (M) | Mediators | (Mo)Mediators | (Int) | Coeff(a): {X→Y} | Coeff(b): {X→M} |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green | Sum | ESG × Sum | 0.0231 *** | [0.0198,0.0264] | 1.8422 *** | [1.3595,2.3742] |

| Pub | ESG × Pub | 0.0217 *** | [0.0182,0.0252] | −0.1644 | [−0.8801,0.5823] | |

| Green1 | Sum | ESG × Sum | 0.0231 *** | [0.0198,0.0264] | 4.6452 *** | [3.5601,5.8538] |

| Pub | ESG × Pub | 0.0217 *** | [0.0182,0.0254] | 1.2489 | [−0.7643,3.6582] | |

| Anuctd | Sum | ESG × Sum | 0.0231 *** | [0.0198,0.0264] | 0.0408 *** | [0.0184,0.0627] |

| Pub | ESG × Pub | 0.0217 *** | [0.0182,0.0254] | −0.1200 *** | [0.0675,0.1750] | |

| Bub | Sum | ESG × Sum | 0.0231 *** | [0.0198,0.0264] | 0.0818 ** | [0.0407,0.1275] |

| Pub | ESG × Pub | 0.0217 *** | [0.0182,0.0252] | 0.1512 ** | [0.1131,0.1944] | |

| Bub1 | Sum | ESG × Sum | 0.0231 *** | [0.0198,0.0264] | 0.0857 ** | [0.0409,0.1353] |

| Pub | ESG × Pub | 0.0217 *** | [0.0182,0.0252] | 0.1394 ** | [0.1053,0.1757] |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension 1: Environmental Regulation | Green | Green1 | Anuctd | ||||

| High ESG Rating Discrepancy | Low ESG Rating Discrepancy | High ESG Rating Discrepancy | Low ESG Rating Discrepancy | High ESG Rating Discrepancy | Low ESG Rating Discrepancy | ||

| Regu | 11.407 | −1.058 | 1.294 | −1.224 | 0.318 | −0.579 * | |

| (7.536) | (1.889) | (5.346) | (1.255) | (0.335) | (0.295) | ||

| ESG | 12.473 *** | 7.571 *** | 5.758 *** | 4.603 *** | 0.305 *** | 0.388 *** | |

| (2.137) | (2.148) | (1.059) | (1.133) | (0.077) | (0.104) | ||

| Regu-ESG | −1.573 *** | −0.340 *** | −1.229 *** | −0.151 ** | 0.012 | −0.009 | |

| (0.418) | (0.130) | (0.352) | (0.063) | (0.011) | (0.014) | ||

| Fisher’s test: | |||||||

| Regu | −12.466 *** | −2.519 | −0.897 | ||||

| ESG | −4.902 *** | −1.155 | 0.083 | ||||

| Regu-ESG | −1.913 *** | −1.381 *** | −0.021 | ||||

| Controls | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | |

| Observations | 12,505 | 9425 | 12,505 | 9425 | 2882 | 1153 | |

| R-squared | 0.720 | 0.557 | 0.678 | 0.508 | 0.864 | 0.795 | |

| Year dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Firm dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension 2: Environmental Regulation | Green | Green1 | Anuctd | |||

| State-owned Enterprises | Non-State-owned Enterprises | State-owned Enterprises | Non-State-owned Enterprises | State-owned Enterprises | Non-State-owned Enterprises | |

| Regu | 8.834 | 7.143 ** | −1.238 | 3.292 | 0.245 | −0.437 |

| (7.389) | (3.417) | (3.757) | (2.377) | (0.386) | (0.326) | |

| ESG | 12.124 *** | 9.318 *** | 6.400 *** | 5.028 *** | 0.408 *** | 0.289 *** |

| (2.923) | (1.937) | (1.466) | (1.065) | (0.090) | (0.087) | |

| Regu-ESG | 0.954 *** | 0.715 ** | 0.754 *** | 0.664 ** | 0.011 | 0.014 |

| (0.307) | (0.350) | (0.269) | (0.279) | (0.015) | (0.011) | |

| Fisher’s test: | ||||||

| Regu | −1.691 | 0.004 *** | 0.428 | |||

| ESG | −2.806 ** | 0.001 *** | 0.197 | |||

| Regu-ESG | −0.239 | 0.011 ** | 0.474 | |||

| Controls | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Observations | 8897 | 12,718 | 8897 | 12,718 | 1727 | 2490 |

| R-squared | 0.657 | 0.686 | 0.619 | 0.663 | 0.837 | 0.805 |

| Year dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension 3: Media Supervision | Green | Green1 | Anuctd | ||||||

| Growth Stage | Maturity Stage | Decline Stage | Growth Stage | Maturity Stage | Decline Stage | Growth Stage | Maturity Stage | Decline Stage | |

| Media | −2.682 ** | −0.456 | −0.172 | −2.244 *** | −0.547 | −0.352 ** | −0.100 | 0.075 | −0.046 |

| (1.058) | (0.493) | (0.235) | (0.713) | (0.338) | (0.159) | (0.075) | (0.048) | (0.029) | |

| ESG | 13.595 *** | 11.959 *** | 9.088 *** | 5.553 ** | 5.208 *** | 4.292 *** | 0.199 ** | 0.266 *** | 0.382 *** |

| (3.666) | (3.005) | (1.978) | (2.353) | (1.417) | (1.152) | (0.098) | (0.084) | (0.080) | |

| Media-ESG | 7.943 | 9.032 ** | 5.432 *** | 9.897 ** | 9.033 *** | 5.186 *** | 0.282 * | 0.020 | 0.284 *** |

| (5.317) | (4.002) | (2.025) | (3.877) | (2.900) | (1.290) | (0.158) | (0.128) | (0.079) | |

| Fisher’s test: | |||||||||

| Media | 2.227 *** | 0.283 * | 2.510 *** | 1.697 *** | 0.194 * | 1.891 *** | 0.175 * | −0.121 * | 0.054 |

| ESG | −1.636 | −2.872 ** | −4.508 *** | −0.345 | −0.916 | −1.261 * | 0.068 | 0.115 | 0.183 * |

| Media-ESG | 1.089 | −3.600 ** | −2.512 | −0.864 | −3.847 *** | −4.711 *** | −0.262 | 0.264 | 0.001 |

| Controls | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Observations | 4457 | 6839 | 10,296 | 4457 | 6839 | 10,296 | 825 | 1109 | 1510 |

| R-squared | 0.636 | 0.792 | 0.824 | 0.603 | 0.781 | 0.846 | 0.870 | 0.858 | 0.854 |

| Year dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Zhao, L. Corporate Dual-Organizational Performance and Substantive Green Innovation Practices: A Quasi-Natural Experiment Analysis Based on ESG Rating Events. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8897. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198897

Li H, Zhao L. Corporate Dual-Organizational Performance and Substantive Green Innovation Practices: A Quasi-Natural Experiment Analysis Based on ESG Rating Events. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8897. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198897

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Huirong, and Li Zhao. 2025. "Corporate Dual-Organizational Performance and Substantive Green Innovation Practices: A Quasi-Natural Experiment Analysis Based on ESG Rating Events" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8897. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198897

APA StyleLi, H., & Zhao, L. (2025). Corporate Dual-Organizational Performance and Substantive Green Innovation Practices: A Quasi-Natural Experiment Analysis Based on ESG Rating Events. Sustainability, 17(19), 8897. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198897