Photo Portraiture Enhances Empathy for Birds with Potential Benefits for Conservation and Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Theory

2.1. Bird Population Importance for Ecosystem Sustainability

2.2. Empathy Drives Conservation and Sustainability Behaviors

Empathy is an emotional state that relies on the ability to engage in one or more of the following: perception, understanding, feeling, and/or action in response to the experiences or perspectives of another human or nonhuman animal.

2.3. Public Perception and Empathy for Birds

2.4. Critical and Strategic Anthropomorphism to Promote Sustainability

2.5. Comparing Animal Photo Portraiture to Traditional Wildife Photography

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Survey Experiment

3.2. Creating the Empathy for Animals Scale (EAS)

3.3. Descriptive Statistics

4. Results

4.1. Assessing Between Photo Impacts

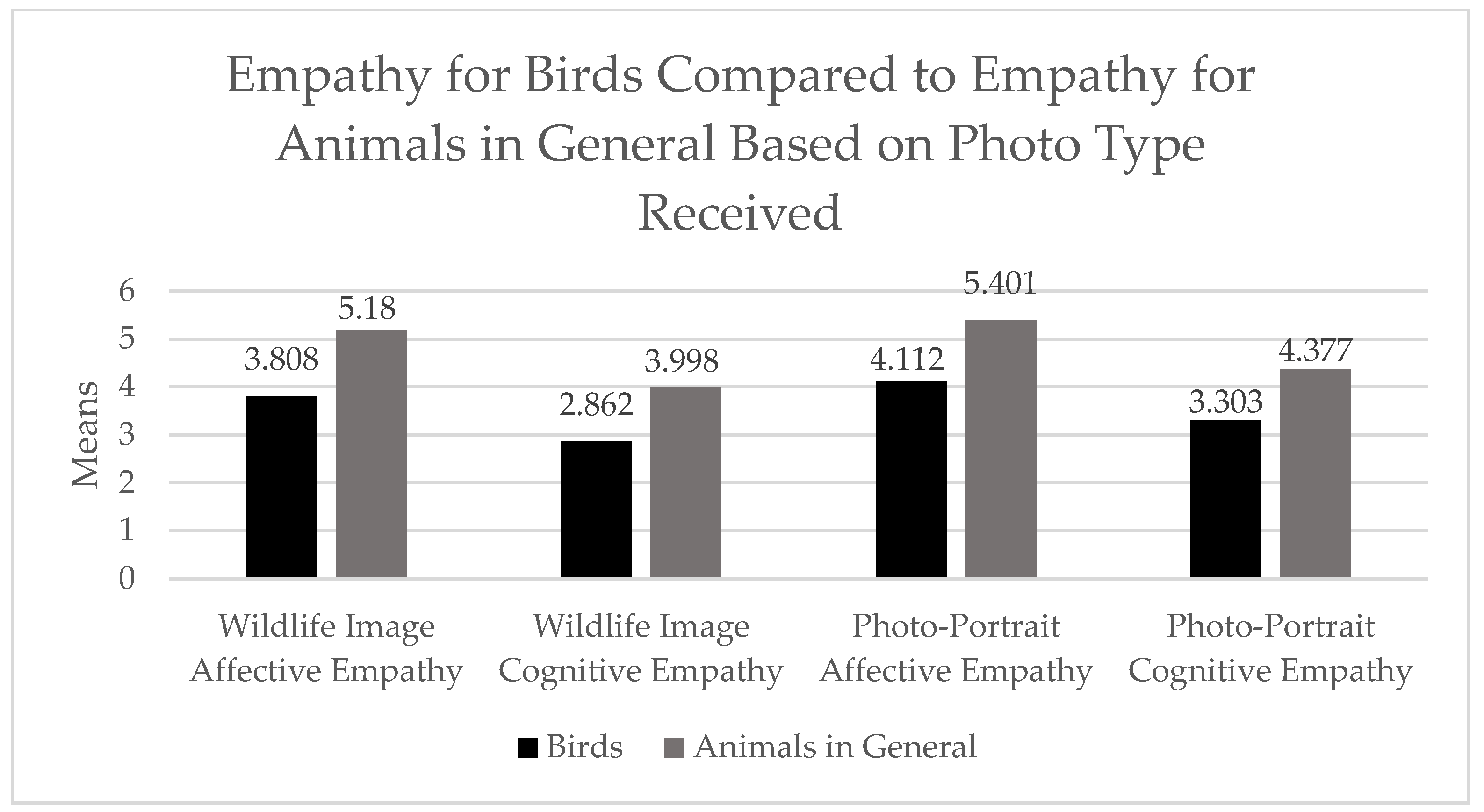

4.2. Comparison of Empathy for Birds and Empathy for Animals Broadly

4.3. Empathy for Birds: Comparing Bird Photo Portraiture and Wildlife Birds

4.4. Empathy for Birds: Comparing Bird Photo Portraiture and Wildlife Animals Broadly

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alagona, P.S. Biography of a ”Feathered Pig”: The California Condor Conservation Controversy. J. Hist. Biol. 2004, 37, 557–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, M. A Message from Martha: The Extinction of the Passenger Pigeon and Its Relevance Today; A&C Black: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 1-4729-0626-8. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, D.; Gladstone, I. The Passenger Pigeon’s Past on Display for the Future. Environ. Hist. 2022, 27, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ienna, M.; Rofe, A.; Gendi, M.; Douglas, H.E.; Kelly, M.; Hayward, M.W.; Callen, A.; Klop-Toker, K.; Scanlon, R.J.; Howell, L.G. The Relative Role of Knowledge and Empathy in Predicting Pro-Environmental Attitudes and Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Mann, J.; Marsh, A. Empathy for Wildlife: The Importance of the Individual. Ambio 2024, 53, 1269–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howlett, K.; Lee, H.; Jaffé, A.; Lewis, M.; Turner, E.C. Wildlife Documentaries Present a Diverse, but Biased, Portrayal of the Natural World. People Nat. 2023, 5, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, M.-X.A.; Clayton, S. Technologically Transformed Experiences of Nature: A Challenge for Environmental Conservation? Biol. Conserv. 2020, 244, 108532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, C.T.; Kalof, L.; Flach, T. Using Animal Portraiture to Activate Emotional Affect. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 837–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, K.V.; Dokter, A.M.; Blancher, P.J.; Sauer, J.R.; Smith, A.C.; Smith, P.A.; Stanton, J.C.; Panjabi, A.; Helft, L.; Parr, M. Decline of the North American Avifauna. Science 2019, 366, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, A.C.; Haskell, L.; Allinson, T.; Bezeng, S.B.; Burfield, I.J.; Renjifo, L.M.; Rosenberg, K.V.; Viswanathan, A.; Butchart, S.H. State of the World’s Birds. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2022, 47, 231–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moraes, K.F.; Santos, M.P.D.; Goncalves, G.S.R.; de Oliveira, G.L.; Gomes, L.B.; Lima, M.G.M. Climate Change and Bird Extinctions in the Amazon. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galetti, M.; Guevara, R.; Côrtes, M.C.; Fadini, R.; Von Matter, S.; Leite, A.B.; Labecca, F.; Ribeiro, T.; Carvalho, C.S.; Collevatti, R.G. Functional Extinction of Birds Drives Rapid Evolutionary Changes in Seed Size. Science 2013, 340, 1086–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuff, B.M.; Brown, S.J.; Taylor, L.; Howat, D.J. Empathy: A Review of the Concept. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, H. The Science of Empathy. J. Patient Exp. 2017, 4, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behler, A.M.C.; Berry, D.R. Closing the Empathy Gap: A Narrative Review of the Measurement and Reduction of Parochial Empathy. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2022, 16, e12701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, J.H.; Meranius, M.S. Toward a Consensus on the Nature of Empathy: A Review of Reviews. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieten, C.; Rubanovich, C.K.; Khatib, L.; Sprengel, M.; Tanega, C.; Polizzi, C.; Vahidi, P.; Malaktaris, A.; Chu, G.; Lang, A.J. Measures of Empathy and Compassion: A Scoping Review. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, S.; Fraser, J.; Saunders, C.D. Zoo Experiences: Conversations, Connections, and Concern for Animals. Zoo Biol. Publ. Affil. Am. Zoo Aquar. Assoc. 2009, 28, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faner, J.M.V.; Dalangin, E.A.R.; De Leon, L.A.T.C.; Francisco, L.D.; Sahagun, Y.O.; Acoba, E.F. Pet Attachment and Prosocial Attitude toward Humans: The Mediating Role of Empathy to Animals. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1391606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, O.E., Jr.; Saunders, C.D.; Garrett, E. What Do Children Think Animals Need? Developmental Trends. Environ. Educ. Res. 2004, 10, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.-P. Dispositional Empathy with Nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wice, M.; Goyal, N.; Forsyth, N.; Noel, K.; Castano, E. The Relationship between Humane Interactions with Animals, Empathy, and Prosocial Behavior among Children. Hum.-Anim. Interact. Bull. 2020, 8, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, J. The Effect of Empathy in Proenvironmental Attitudes and Behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Song, C.; Ma, C. Effect of Different Types of Empathy on Prosocial Behavior: Gratitude as Mediator. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 768827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascione, F.R. Enhancing Children’s Attitudes about the Humane Treatment of Animals: Generalization to Human-Directed Empathy. Anthrozoös 1992, 5, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, O.G. The Significance of Children and Animals: Social Development and Our Connections to Other Species; Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2007; ISBN 1-55753-429-2. [Google Scholar]

- Cassels, T.G.; Chan, S.; Chung, W. The Role of Culture in Affective Empathy: Cultural and Bicultural Differences. J. Cogn. Cult. 2010, 10, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolrych, T.; Eady, M.J.; Green, C.A. Authentic Empathy: A Cultural Basis for the Development of Empathy in Children. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2020, 64, 954–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Khalil, K.A.; Wharton, J. Empathy for Animals: A Review of the Existing Literature. Curator Mus. J. 2018, 61, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M.; Haddaway, N.R. Which Academic Search Systems Are Suitable for Systematic Reviews or Meta—analyses? Evaluating Retrieval Qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 Other Resources. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, 11, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maibom, H.L. Affective Empathy. In The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Empathy; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Spaulding, S. Cognitive Empathy. In The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Empathy; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.; Adger, W.N.; Devine-Wright, P.; Anderies, J.M.; Barr, S.; Bousquet, F.; Butler, C.; Evans, L.; Marshall, N.; Quinn, T. Empathy, Place and Identity Interactions for Sustainability. Glob. Environ. Change 2019, 56, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, E.; Fancovicová, J.; Randler, C.; Ozel, M.; Usak, M.; Medina-Jerez, W.; Prokop, P. Interest in Birds and Its Relationship with Attitudes and Myths: A Cross-Cultural Study in Countries with Different Levels of Economic Development. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2015, 15, 285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, R.; Larson, K.L.; Franklin, J.; Lerman, S.B.; Bateman, H.L.; Warren, P.S. Species Traits Explain Public Perceptions of Human–Bird Interactions. Ecol. Appl. 2022, 32, e2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaire, J.A.; Westphal, L.M.; Whelan, C.J.; Minor, E.S. Urban Residents’ Perceptions of Birds in the Neighborhood: Biodiversity, Cultural Ecosystem Services, and Disservices. Condor Ornithol. Appl. 2015, 117, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.K. Human–Bird Interactions. In The Welfare of Domestic Fowl and Other Captive Birds; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 17–51. [Google Scholar]

- Clergeau, P.; Mennechez, G.; Sauvage, A.; Lemoine, A. Human Perception and Appreciation of Birds: A Motivation for Wildlife Conservation in Urban Environments of France. In Avian Ecology and Conservation in an Urbanizing World; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Jerolmack, C. Animal Practices, Ethnicity, and Community: The Turkish Pigeon Handlers of Berlin. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2007, 72, 874–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerolmack, C. How Pigeons Became Rats: The Cultural-Spatial Logic of Problem Animals. Soc. Probl. 2008, 55, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, J.L.; Paul, E.S.; Harris, L.; Penturn, S.; Nicol, C.J. No Evidence for Emotional Empathy in Chickens Observing Familiar Adult Conspecifics. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Liévin-Bazin, A. Prosociality, Social Cognition and Empathy in Psittacids and Corvids. Ph.D. Thesis, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ingham, H.R.W.; Neumann, D.L.; Waters, A.M. Empathy-Related Ratings to Still Images of Human and Nonhuman Animal Groups in Negative Contexts Graded for Phylogenetic Similarity. Anthrozoös 2015, 28, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.S. Empathy with Animals and with Humans: Are They Linked? Anthrozoös 2000, 13, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmeister, A.-K.; Drasch, K.; Rinder, M.; Prechsl, S.; Peschel, A.; Korbel, R.; Saam, N.J. Development and Application of the Owner-Bird Relationship Scale (OBRS) to Assess the Relation of Humans to Their Pet Birds. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 575221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, E.L. Birds Are Not More Human than Dogs: Evidence from Naming. Names 2007, 55, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt, S. Human Attitudes towards Animals in Relation to Species Similarity to Humans: A Multivariate Approach. Biosci. Horiz. 2009, 2, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C.R. Anthropomorphism, Anthropocentrism, and Human-Orientation in Environmental Discourse. J. Lang. Polit. 2023, 22, 601–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredo, M.J.; Berl, R.E.; Teel, T.L.; Bruskotter, J.T. Bringing Social Values to Wildlife Conservation Decisions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2021, 19, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Melara, J.L.; Acosta-Naranjo, R.; Izar, P.; Sah, S.A.M.; Pladevall, J.; Maulany, R.I.; Ngakan, P.O.; Majolo, B.; Romero, T.; Amici, F. A Cross-Cultural Comparison of the Link between Modernization, Anthropomorphism and Attitude to Wildlife. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daston, L.; Mitman, G. Thinking with Animals: New Perspectives on Anthropomorphism; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 0-231-13038-4. [Google Scholar]

- Colléony, A.; Clayton, S.; Couvet, D.; Saint Jalme, M.; Prévot, A.-C. Human Preferences for Species Conservation: Animal Charisma Trumps Endangered Status. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 206, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.W. Respect for Nature: A Theory of Environmental Ethics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 1-4008-3853-3. [Google Scholar]

- Grasso, C.; Lenzi, C.; Speiran, S.; Pirrone, F. Anthropomorphized Nonhuman Animals in Mass Media and Their Influence on Human Attitudes toward Wildlife. Soc. Anim. 2020, 31, 196–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, G.L. Anthropomorphism and Animals in the Anthropocene. In Engaging with Animals: Interpretations of a Shared Experience; Sydney University Press: Sydney, Australia, 2014; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, N. Anthropomorphism and the Animal Subject. In Anthropocentrism; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 265–280. [Google Scholar]

- Gertz, C. Deep Play: The Interpretation of Cultures. N. Y. 1973. Available online: https://a-better.wales/pages/play-wales/pages/resources/Deep-Play-Notes-on-the-Balinese-Cockfight.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Flach, T. Tim Flach. Available online: https://timflach.com (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Sartore, J. Man on a Mission: Building the Photo Ark. Available online: https://www.joelsartore.com (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- International League of Conservation Photographers. Available online: https://conservationphotographers.org/ethics (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Thomas-Walters, L.; McNulty, C.; Veríssimo, D. A Scoping Review into the Impact of Animal Imagery on Pro-Environmental Outcomes. Ambio 2020, 49, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiot, C.E.; Bastian, B. Solidarity with Animals: Assessing a Relevant Dimension of Social Identification with Animals. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0168184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalof, L.; Zammit-Lucia, J.; Kelly, J.R. The Meaning of Animal photo-portraiture in a Museum Setting: Implications for Conservation. Organ. Environ. 2011, 24, 150–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalof, L.; Zammit-Lucia, J.; Bell, J.; Granter, G. Fostering Kinship with Animals: Animal photo-portraiture in Humane Education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 203–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, D.; Tong, Z.; Tian, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Y. Anthropomorphic Strategies Promote Wildlife Conservation through Empathy: The Moderation Role of the Public Epidemic Situation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, e3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, T.H.; Yoon, S.; Kim, S. The Baby Animal Effect in Wildlife Conservation Advertising. J. Advert. Res. 2025, pp. 1–20. Available online: https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.library.wwu.edu/doi/pdf/10.1080/00218499.2024.2447126?casa_token=5P10Jqz2dBAAAAAA:zfc1oTq-zS9cCBk-g9JxHmqfyX-6_MMwAcsgje4oWIeXK7LqJRf3zyGOT0u3k7oLLFgApbttixnO (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Douglas, B.D.; Ewell, P.J.; Brauer, M. Data Quality in Online Human-Subjects Research: Comparisons between MTurk, Prolific, CloudResearch, Qualtrics, and SONA. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, E.; Rothschild, D.; Gordon, A.; Evernden, Z.; Damer, E. Data Quality of Platforms and Panels for Online Behavioral Research. Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 54, 1643–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Smith, J.K.; Tinio, P.P. Time Spent Viewing Art and Reading Labels. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2017, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flach, T. Birds; Abrams: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychological Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. QuickFacts United States Census. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/sis/resources/data-tools/quickfacts.html (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Shaw, M.N.; Borrie, W.T.; McLeod, E.M.; Miller, K.K. Wildlife Photos on Social Media: A Quantitative Content Analysis of Conservation Organisations’ Instagram Images. Animals 2022, 12, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miralles, A.; Raymond, M.; Lecointre, G. Empathy and Compassion toward Other Species Decrease with Evolutionary Divergence Time. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edney, G.; Smart, T.; Howat, F.; Batchelor, Z.E.; Hughes, C.; Moss, A. Assessing the Effect of Interpretation Design Traits on Zoo Visitor Engagement. Zoo Biol. 2023, 42, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, C.; McWhorter, T.J.; Xie, S.; Mohd Nasir, T.S.B.; Reh, B.; Fernandez, E.J. A Comparison of Staff Presence and Signage on Zoo Visitor Behavior. Zoo Biol. 2023, 42, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, K.; McConney, A.; Mansfield, C.F. How Do Zoos ‘Talk’to Their General Visitors? Do Visitors ‘Listen’? A Mixed Method Investigation of the Communication between Modern Zoos and Their General Visitors. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 30, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballarotto, G.; Ghezzi, V.; Velotti, P. Feeling the Nature to Foster Sustainability: The Mediating Role of (Self) Compassion. Sustainability 2025, 17, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paffen, K. Shoebill Stork [Photography]. 2023. Available online: https://ourplanetinmylens.com/wildlife/african-animals/shoebill/ (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Flach, T. 25 Shoebill [Photography]. 2017. Available online: https://timflach.com/work/endangered/slideshow/#25 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Gardner, M. Gouldian Finch [Photography]. 2018. Available online: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/96388321 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Flach, T. 63 Gouldian Finch [Photography]. 2021. Available online: https://timflach.com/work/birds/slideshow/#63 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Phillippine Eagle Foundation. Phillippine Eagle [Graphic]. 2024. Available online: https://www.philippineeaglefoundation.org/philippine-eagle (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Flach, T. 23 Phillippine Eagle Front [Photography]. 2017. Available online: https://timflach.com/work/endangered/slideshow/#23 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Oldroyd, R. Inca Tern [Photography]. 2023. Available online: https://www.istockphoto.com/photo/inca-tern-stood-on-a-log-gm1489806991-514592726 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Flach, T. 7 Inca Tern [Photography]. 2021. Available online: https://timflach.com/work/birds/slideshow/#7 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

| Survey Item | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|

| Affective Empathy for Animals in General | 0.896 |

| I feel happy when I see happy animals. | |

| Seeing a sad animal does NOT make me feel upset. (R) | |

| I can feel the emotions of animals. | |

| I am NOT really affected by the emotions of animals. (R) | |

| Seeing an animal in pain affects me. | |

| Cognitive Empathy for Animals in General | 0.849 |

| I am NOT usually aware of the feelings of animals. (R) | |

| I can usually understand when animals feel sad. | |

| I DON’T often wonder what animals are thinking. (R) | |

| I often think about what animals are feeling. | |

| I CAN’T really understand how animals are feeling. (R) | |

| Affective Empathy for Birds | 0.770 |

| Seeing the bird happy would make me feel happy. | |

| I would NOT feel upset if I knew the bird was sad. (R) | |

| I could feel the emotions of the bird. | |

| I was NOT really affected by the emotions of the bird. (R) | |

| Seeing the bird in pain would affect me. | |

| Cognitive Empathy for Birds | 0.890 |

| I was NOT aware of the feelings of the bird. (R) | |

| I could understand if the bird was sad. | |

| I DIDN’T wonder what the bird was thinking. (R) | |

| I thought about what the bird was feeling. | |

| I could NOT really understand what the bird was feeling. (R) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Whitley, C.T.; Kalof, L.; Urquhart, L.C.; Tatem, N.; Mair, M.; Ankoudinova, K.; Haight, I.; Meglathery, E.; Worden, M.; Wilkinson, D.; et al. Photo Portraiture Enhances Empathy for Birds with Potential Benefits for Conservation and Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8833. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198833

Whitley CT, Kalof L, Urquhart LC, Tatem N, Mair M, Ankoudinova K, Haight I, Meglathery E, Worden M, Wilkinson D, et al. Photo Portraiture Enhances Empathy for Birds with Potential Benefits for Conservation and Sustainability. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8833. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198833

Chicago/Turabian StyleWhitley, Cameron T., Linda Kalof, L. C. Urquhart, Nate Tatem, Melissa Mair, Katya Ankoudinova, Ingrid Haight, Eva Meglathery, Matthew Worden, Daniella Wilkinson, and et al. 2025. "Photo Portraiture Enhances Empathy for Birds with Potential Benefits for Conservation and Sustainability" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8833. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198833

APA StyleWhitley, C. T., Kalof, L., Urquhart, L. C., Tatem, N., Mair, M., Ankoudinova, K., Haight, I., Meglathery, E., Worden, M., Wilkinson, D., Schulz, M., Neville, K., & Flach, T. (2025). Photo Portraiture Enhances Empathy for Birds with Potential Benefits for Conservation and Sustainability. Sustainability, 17(19), 8833. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198833