Structural Determinants of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Convergence in OECD Countries: A Machine Learning-Based Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Environmental Convergence: Theoretical Background and Empirical Evidence

2.2. Machine Learning Applications in Environmental Research

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data and Variables

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Club Convergence Analysis

3.2.2. Extreme Gradient Boosting

4. Results and Discussions

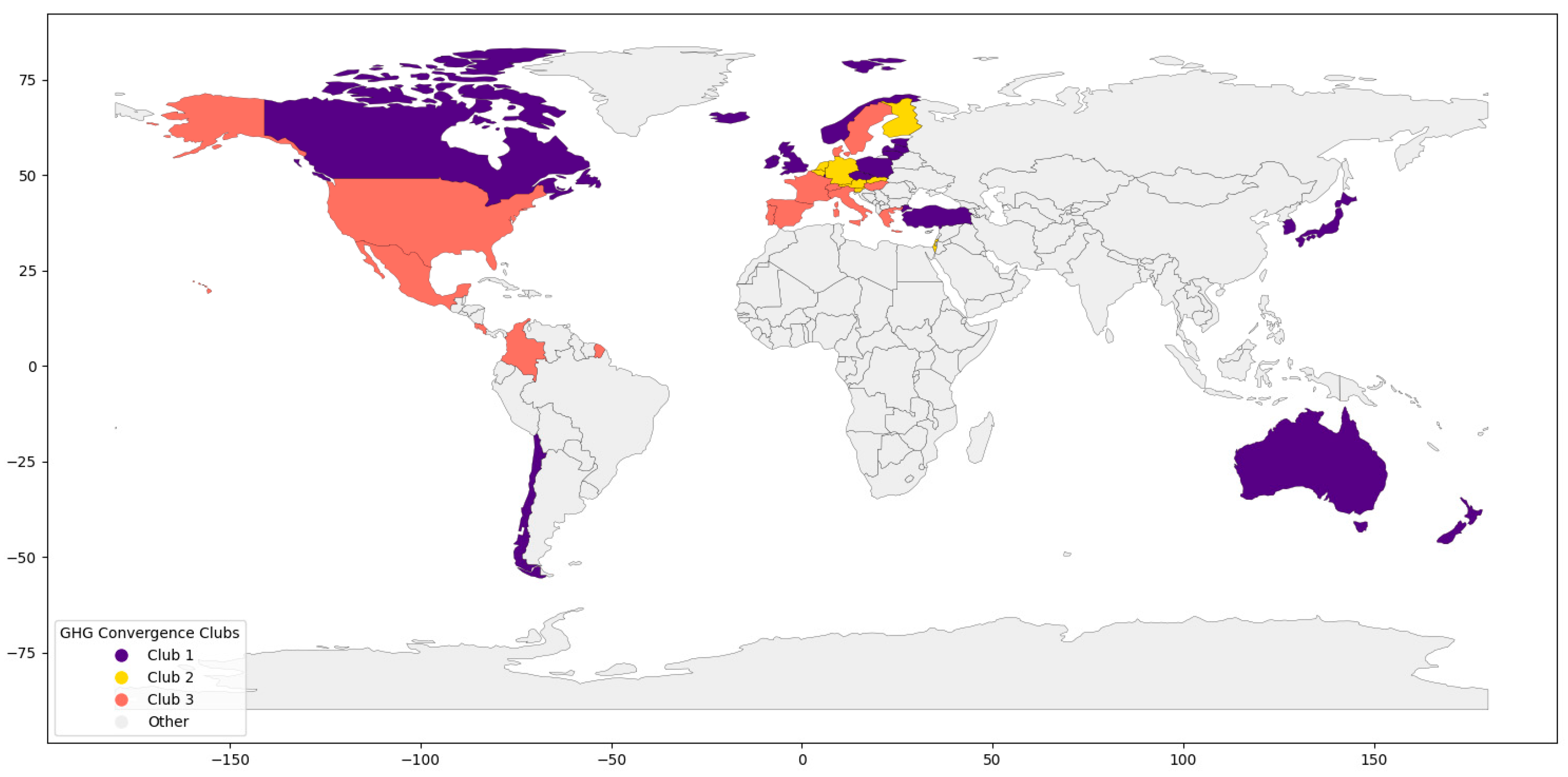

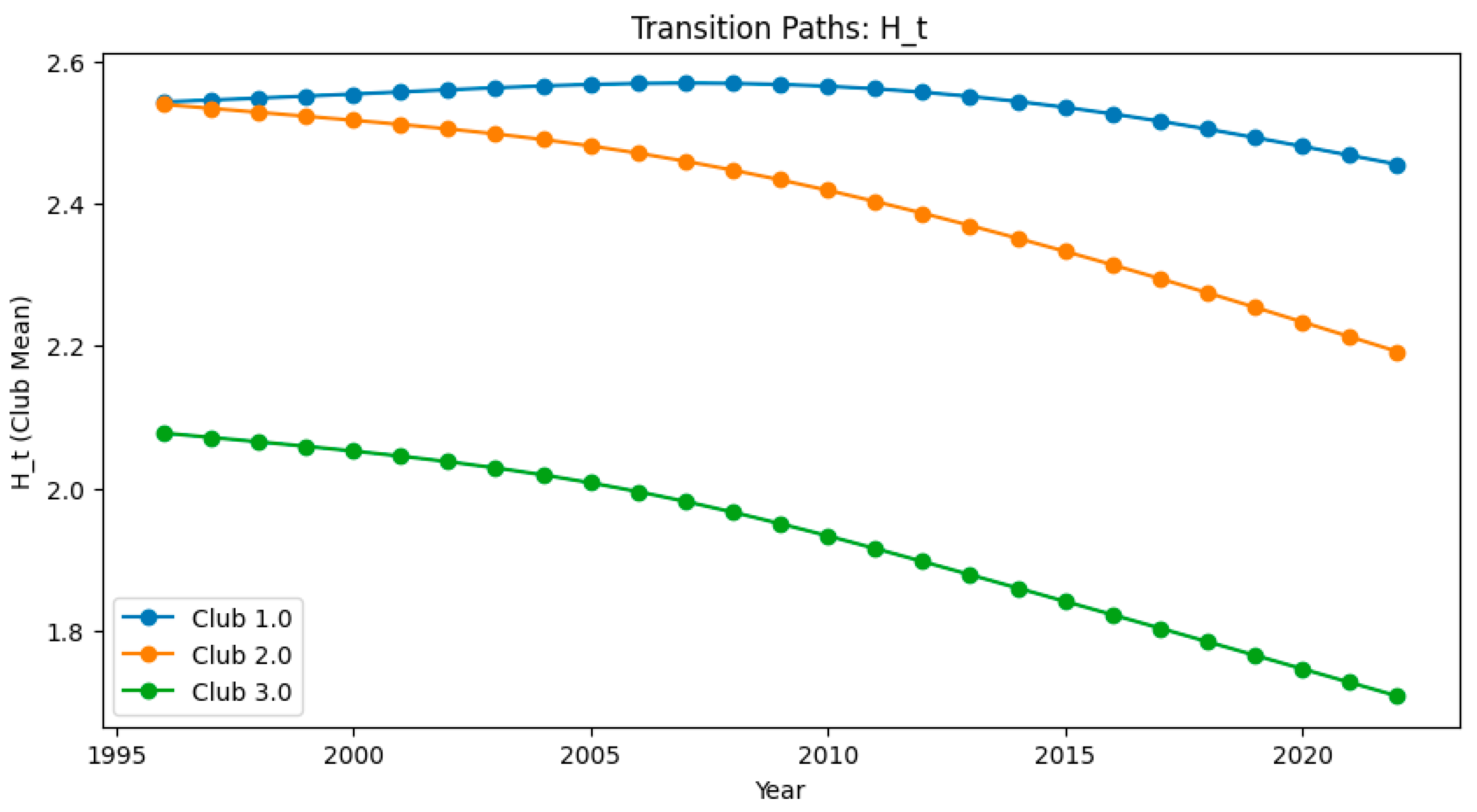

4.1. Club Covergence Results

4.2. XGBoost Results

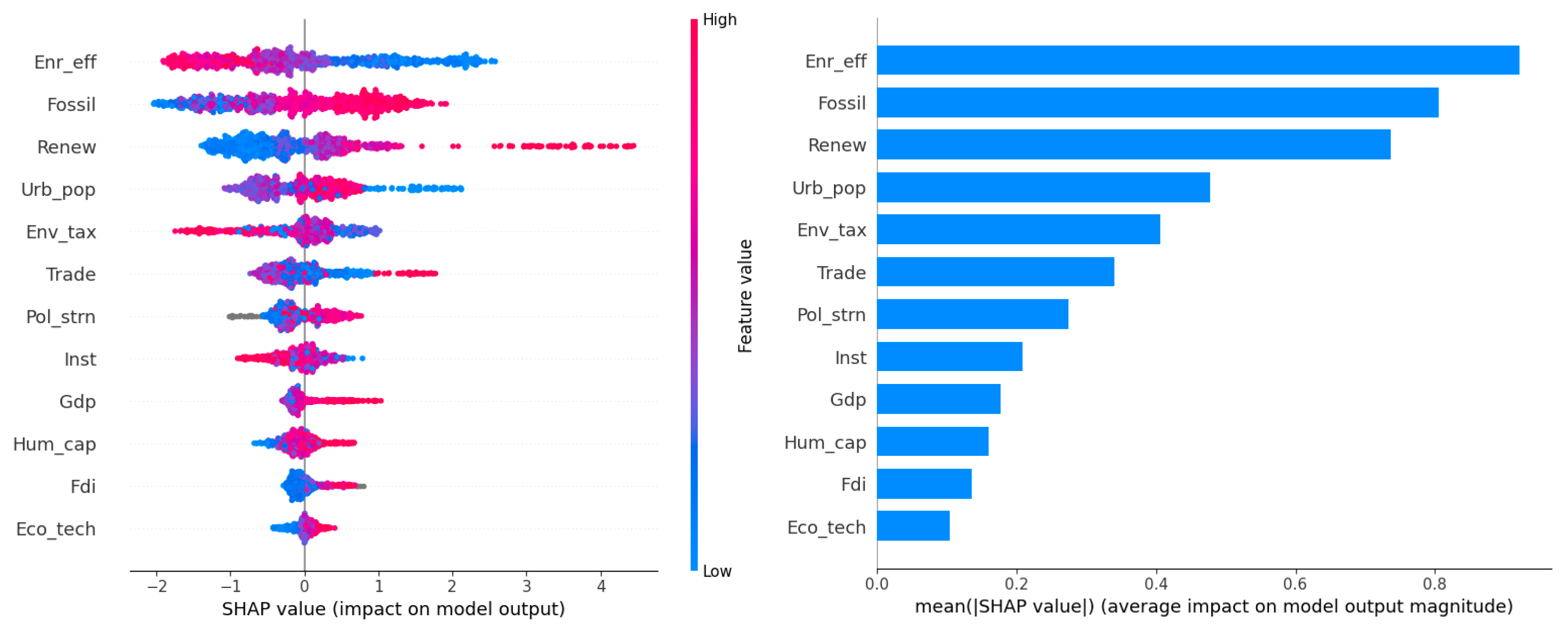

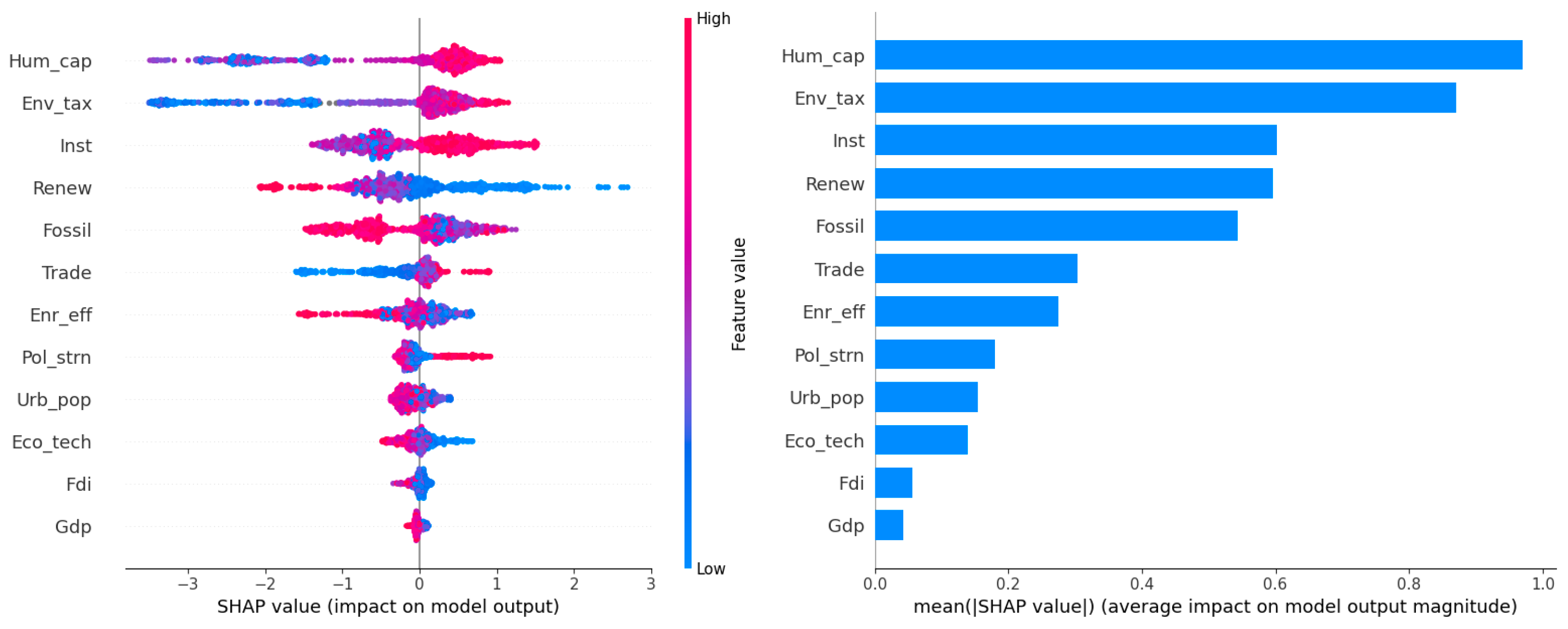

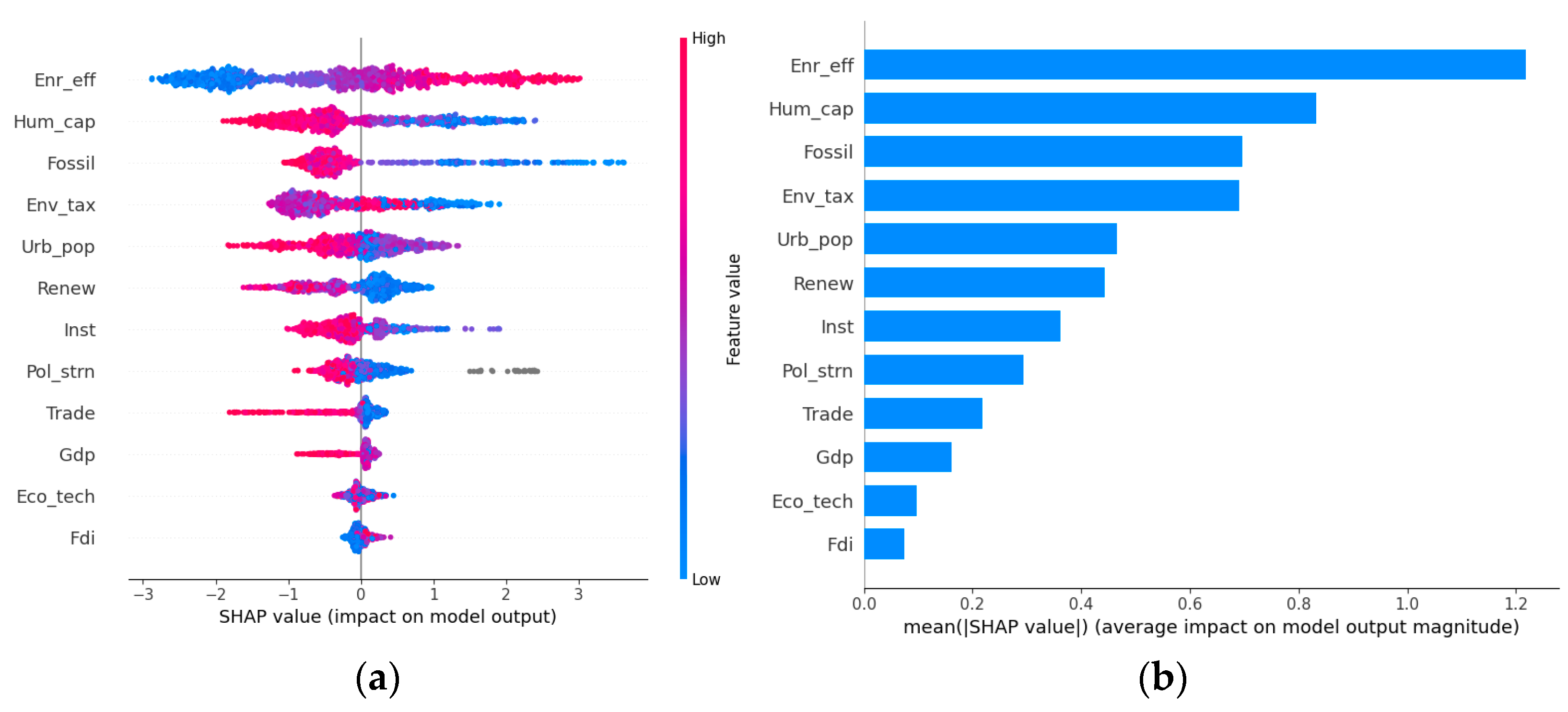

4.3. SHAP Analysis Results

4.4. Robustness Check

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GHGs | Greenhouse Gas Emissions |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| SHAP | SHAPley Additive Explanations |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| CH4 | Methane |

| N2O | Nitrous Oxide |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change |

| NDCs | Nationally Determined Contributions |

| ML | Machine Learning (ML) |

| WDI | World Development Indicators |

| WGI | Worldwide Governance Indicators |

| PDPs | Partial Dependence Plots |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Values |

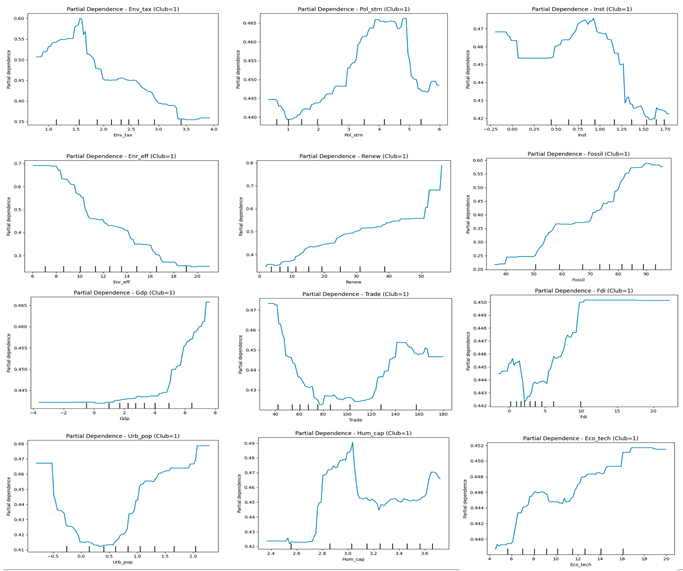

Appendix A. Partial Dependence for Club 1

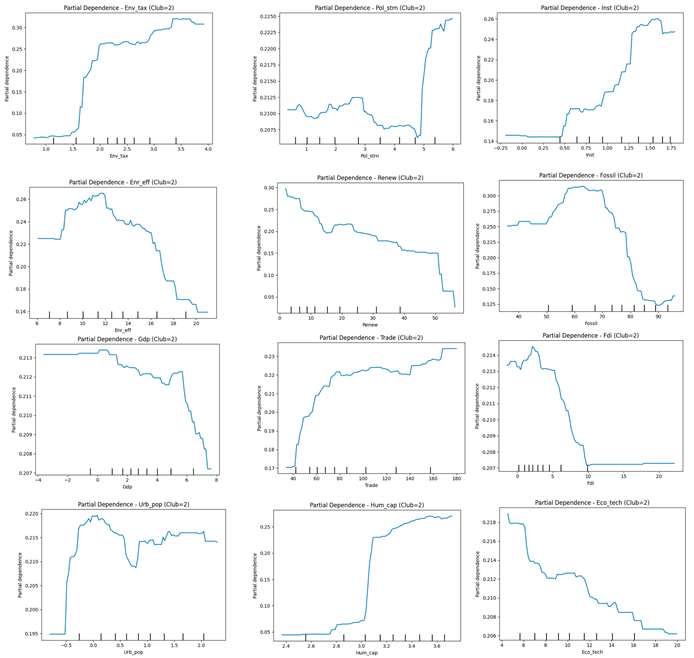

Appendix B. Partial Dependence for Club 2

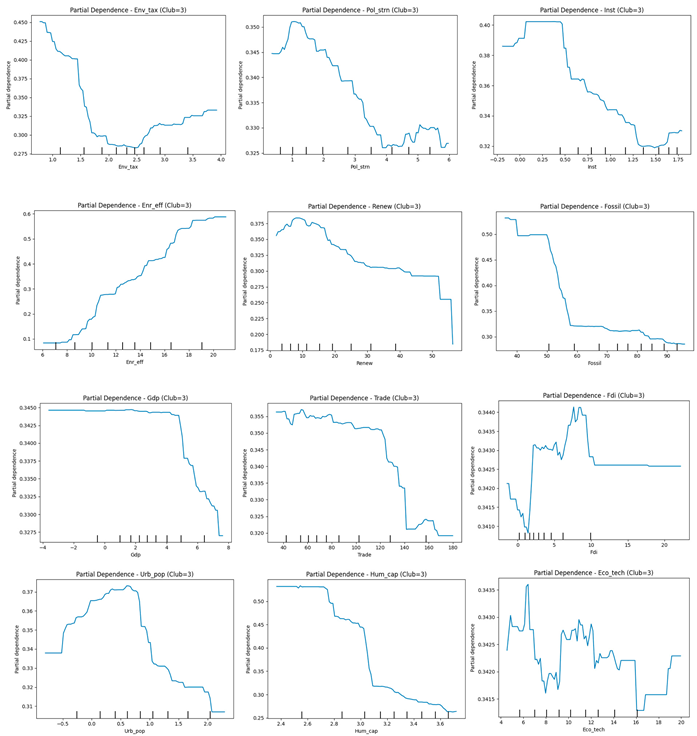

Appendix C. Partial Dependence for Club 3

References

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics: Monitoring Health for the SDGS, Sustainable Development Goals; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Nationen, V. (Ed.) Realizing the Importance of Forests in a Changing World; The Global Forest Goals Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kjellström, T.; Maître, N.; Saget, C.; Otto, M.; Karimova, T. Working on a Warmer Planet: The Effect of Heat Stress on Productivity and Decent Work; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5 °C: IPCC Special Report on Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels in Context of Strengthening Response to Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329841417_Global_warming_of_15C_An_IPCC_Special_Report_on_… (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- GHG Emission Trends and Targets (GETT): Harmonised Quantification Methodology and Indicators; OECD Environment Working Papers No. 230. 2024. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/ghg-emission-trends-and-targets-gett_decef216-en.html (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Barassi, M.R.; Spagnolo, N.; Zhao, Y. Fractional Integration Versus Structural Change: Testing the Convergence of CO2 Emissions. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2018, 71, 923–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarin, S.A. Convergence in CO2 emissions, carbon footprint and ecological footprint: Evidence from OECD countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 6167–6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, L.A.; Martino, R.; Nguyen-Van, P. Environmental convergence and environmental Kuznets curve: A unified empirical framework. Ecol. Model. 2020, 437, 109289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Kporsu, A.K.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Edziah, B.K. Estimating environmental efficiency and convergence: 1980 to 2016. Energy 2020, 208, 118224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bektaş, V.; Ursavaş, N. Revisiting the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis with globalization for OECD countries: The role of convergence clubs. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 47090–47105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowiec, J.; Papież, M. Convergence of CO2 emissions in countries at different stages of development. Do globalisation and environmental policies matter? Energy Policy 2024, 184, 113866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahouangbe, V.L.; Turcu, C. How bilateral foreign direct investment influences environmental convergence. World Econ. 2024, 47, 37–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, S. Effect of renewable energy consumption on environmental quality in sub-Saharan African countries: Evidence from defactored instrumental variables method. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2024, 35, 839–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.C.B.; Sul, D. Transition Modeling and Econometric Convergence Tests. Econometrica 2007, 75, 1771–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R.J.; Sala-i-Martin, X. Convergence. J. Polit. Econ. 1992, 100, 223–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldy, J.E. Per capita carbon dioxide emissions: Convergence or divergence. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2006, 33, 533–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezcurra, R. Is there cross-country convergence in carbon dioxide emissions? Energy Policy 2007, 35, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigerna, S.; Bollino, C.A.; Polinori, P. Convergence in renewable energy sources diffusion worldwide. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 292, 112784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strazicich, M.C.; List, J.A. Are CO2 Emission Levels Converging Among Industrial Countries? Environ. Resour. Econ. 2003, 24, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acaravcı, A.; Erdogan, S. The convergence behavior of CO2 emissions in seven regions under multiple structural breaks. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2016, 6, 575–580. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Yucel, A.G.; Islam, M.T. Convergence of CO2 emissions in OECD countries. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2023, 2, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKibbin, W.J.; Stegman, A. Convergence and per capita carbon emissions. CAMA Work. Pap. Ser. 2005, 167, 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, W.A.; Taylor, M.S. The green Solow model. J. Econ. Growth 2010, 15, 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lin, B. Global convergence in per capita CO2 emissions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 24, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaya, E.; Alataş, S.; Yılmaz, B. Replication of Strazicich and List (2003): Are CO2 emission levels converging among industrial countries? Energy Econ. 2019, 82, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panopoulou, E.; Pantelidis, T. Club Convergence in Carbon Dioxide Emissions. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2009, 44, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrerias, M.J. The environmental convergence hypothesis: Carbon dioxide emissions according to the source of energy. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 1140–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.; Akram, V. Club convergence analysis of ecological and carbon footprint: Evidence from a cross-country analysis. Carbon Manag. 2019, 10, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulucak, R.; Apergis, N. Does convergence really matter for the environment? An application based on club convergence and on the ecological footprint concept for the EU countries. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 80, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, F.; Ulucak, R. Is there deterministic, stochastic, and/or club convergence in ecological footprint indicator among G20 countries? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 35404–35419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varian, H.R. Big Data: New Tricks for Econometrics. J. Econ. Perspect. 2014, 28, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaraiti, M.; Merabet, A. Solar Power Forecasting Using Deep Learning Techniques. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 31692–31698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, D.; Direkoglu, C.; Kusaf, M.; Fahrioglu, M. Hybrid deep learning models for time series forecasting of solar power. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 9095–9112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, E.; Baldinelli, G.; Wang, J.; Bartocci, P.; Shamim, T. Artificial intelligence based forecasting and optimization model for concentrated solar power system with thermal energy storage. Appl. Energy 2025, 382, 125210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, R.; Patne, N.R.; Padmanaban, S.; Sana Amreen, T. Comparative and Novel Priority Ranking Analysis for Short-Term Solar Power Prediction. IETE J. Res. 2025, 71, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, K.; Du, J.; Appah, R.; Quacoe, D. Prediction of Potential Carbon Dioxide Emissions of Selected Emerging Economies Using Artificial Neural Network. J. Environ. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 7, 321–335. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Huang, G.; Yan, N. Forecasting Energy-Related CO2 Emissions Employing a Novel SSA-LSSVM Model: Considering Structural Factors in China. Energies 2018, 11, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komeili Birjandi, A.; Fahim Alavi, M.; Salem, M.; Assad, M.E.H.; Prabaharan, N. Modeling carbon dioxide emission of countries in southeast of Asia by applying artificial neural network. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2022, 17, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakilu, O.B.; Chen, H. Carbon Dioxide Emissions Prediction of Selected Developing Countries Using Artificial Neural Network. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025; Advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zheng, X.; Yang, Z.; Kuang, L. Predicting Short-Term Electricity Demand by Combining the Advantages of ARMA and XGBoost in Fog Computing Environment. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2018, 2018, 5018053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yu, Z.; Qu, Y.; Xu, J.; Cao, Y. Application of the XGBoost Machine Learning Method in PM2.5 Prediction: A Case Study of Shanghai. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; An, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, C.; Yu, H.; Zhou, X.; Geng, Y. Application of XGBoost algorithm in the optimization of pollutant concentration. Atmos. Res. 2022, 276, 106238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, A.M.; Mobin, M.A. A machine learning approach to carbon emissions prediction of the top eleven emitters by 2030 and their prospects for meeting Paris agreement targets. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imran, M.; Jijian, Z.; Sharif, A.; Magazzino, C. Evolving waste management: The impact of environmental technology, taxes, and carbon emissions on incineration in EU countries. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 364, 121440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Xiong, W.; Zhang, S.; Shi, H.; Wu, S.; Bao, S.; Xiao, T. Research on the Nonlinear Relationship Between Carbon Emissions from Residential Land and the Built Environment: A Case Study of Susong County, Anhui Province Using the XGBoost-SHAP Model. Land 2025, 14, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, S.; Gong, H.; Zhang, C. Revealing the nonlinear impact of environmental regulation on ecological resilience using the XGBoost-SHAP model: Evidence from the Yangtze River Delta region, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 514, 145700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K. Econometric Convergence Test and Club Clustering Using Stata. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 2017, 17, 882–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.; Feng, S.; Li, K.; Chang, R.; Huang, R. Unveiling the effects of artificial intelligence and green technology convergence on carbon emissions: An explainable machine learning-based approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, S.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.07874. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| GHG | Total greenhouse gas emissions per capita (t CO2e/capita) | OECD |

| Env_Tax | Environmental tax revenue as a share of GDP | OECD |

| Sect_Pol | The stringency of environmental regulations by sector (0 = least, 10 = most stringent) | OECD |

| Enr_eff | GDP per unit of energy use (constant 2021 PPP $ per kg of oil equivalent) | WDI |

| Eco_Tech | Eco-friendly technologic development (Relative advantage in environment-related technologies index) | OECD |

| Fossil_Enr | Fossil fuel energy consumption (% of total) | OECD |

| Rnw_Enr | Renewable energy consumption (% of total) | OECD |

| Urban_Pop_Growth | Urban population growth rate | WDI |

| Inst | Institutional quality indicator (Average of voice and accountability, Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism, Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Quality, Rule of Law, Control of Corruption | WGI |

| Hum_Cap | Human capital index | WDI |

| Gdp | GDP growth | WDI |

| Trade | Trade openness | WDI |

| Fdi | Foreign direct investments oreign direct investment (net inflows, (% of GDP) | WDI |

| Clubs | Countries | Coefficient |

|---|---|---|

| Whole sample | 38 | −0.5751 (−32.237) |

| Club 1 | Australia, Canada, Korea, Türkiye | 0.166 (3.022) |

| Club 2 | Lithuania, New Zealand, United Kingdom | 0.186 (3.843) |

| Club 3 | Chile, Czechia, Estonia, Iceland, Ireland, Japan, Latvia, Luxembourg, Norway, Poland | 0.254 (3.575) |

| Club 4 | Belgium, Finland, Germany, Netherlands, Slovak Republic | 0.470 (4.317) |

| Club 5 | Austria, Israel, Slovenia | 0.228 (0.530) |

| Club 6 | Colombia, Costa Rica, Denmark, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Mexico, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United States | 0.066 (1.030) |

| Group Merge | ||

| Club 1 + 2 | 0.157 (3.027) | |

| Club 2 + 3 | 0.125 (2.205) | |

| Club 3 + 4 | 0.193 (2.815) | |

| Club 4 + 5 | 0.363 (4.785) | |

| Club 5 + 6 | −0.25 (−5.453) | |

| Final Club | ||

| Club 1 | Australia, Canada, Chile, Czechia, Estonia, Iceland, Ireland, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Türkiye, United Kingdom | 0.021 (0.409) |

| Club 2 | Austria, Belgium, Finland, Germany, Israel, Netherlands, Slovak Republic, Slovenia | 0.363 (4.785) |

| Club 3 | Colombia, Costa Rica, Denmark, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Mexico, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United States | 0.066 (1.030) |

| (Counts Per Year 1996–2022) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Club 1 | Club 2 | Club 3 | Total |

| 1996 | 17 | 8 | 13 | 38 |

| 1997 | 17 | 8 | 13 | 38 |

| … | … | … | … | … |

| 2022 | 17 | 8 | 13 | 38 |

| Counts by period | ||||

| Period | Club 1 | Club 2 | Club 3 | Total |

| 1996–2002 | 119 | 56 | 91 | 266 |

| 2003–2012 | 170 | 80 | 130 | 380 |

| 2013–2022 | 170 | 80 | 130 | 380 |

| Overall | 459 | 216 | 351 | 1026 |

| Prediction\Reference | Club 1 | Club 2 | Club 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Club 1 | 90 | 1 | 1 |

| Club 2 | 0 | 43 | 0 |

| Club 3 | 0 | 0 | 71 |

| Metric | Mean | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | Cohen’s Kappa | p-Value (Accuracy > NIR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 98.05% | 97.44% | 98.66% | 98.48% | <2.5 × 10−68 |

| Precision (macro) | 97.66% | 97.50% | 98.43% | - | - |

| Recall (macro) | 97.92% | 97.20% | 98.65% | - | - |

| F1 Score (macro) | 97.93% | 97.37% | 98.49% | - | - |

| Seed | Accuracy | Precision Macro | Recall Macro | F1 Macro |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 98.05% | 97.96% | 97.92% | 97.93% |

| 42 | 98.05% | 97.96% | 97.92% | 97.93% |

| 123 | 98.05% | 97.96% | 97.92% | 97.93% |

| 999 | 98.05% | 97.96% | 97.92% | 97.93% |

| 2025 | 98.05% | 97.96% | 97.92% | 97.93% |

| Reference/Prediction | Club 1 | Club 2 | Club 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Club 1 | 90.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Club 2 | 1 | 42 | 0.2 |

| Club 3 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 68.8 |

| Club | Sensitivity | Specificity | Precision (PPV) | NPV | Balanced Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 97.83% | 100% | 100% | 98.28% | 98.91% |

| 2 | 100% | 99.39% | 97.73% | 100% | 99.69% |

| 3 | 100% | 99.26% | 98.61% | 100% | 99.63% |

| Feature | Importance | Normalized Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Enr_eff | 2.0976 | 0.1473 |

| Trade | 1.81 | 0.1271 |

| Hum_cap | 1.5386 | 0.108 |

| Env_tax | 1.3501 | 0.0948 |

| Fossil | 1.2562 | 0.0882 |

| Urb_pop | 1.1899 | 0.0835 |

| Renew | 1.1386 | 0.0799 |

| Pol_strn | 1.1365 | 0.0798 |

| Inst | 1.0288 | 0.0722 |

| Gdp | 0.7863 | 0.0552 |

| Eco_tech | 0.5084 | 0.0357 |

| Fdi | 0.4041 | 0.0284 |

| Variable | Club 2 (Coefficient (p-Value)) | Club 3 (Coefficient (p-Value)) |

|---|---|---|

| Hum_cap | 1.6272 *** (0.000) | −1.4862 *** (0.000) |

| Fossil | −0.1171 *** (0.000) | −0.2281 *** (0.000) |

| Enr_eff | 0.1814 *** (0.000) | 0.5267 *** (0.000) |

| Renew | −0.1372 *** (0.000) | −0.1995 *** (0.000) |

| Trade | −0.0047 ** (0.019) | −0.0310 *** (0.000) |

| Urb_pop | −0.1435 (0.293) | −0.2760 * (0.063) |

| Pol_strn | −0.1213 (0.184) | −0.3169 *** (0.002) |

| Inst | 0.5931 ** (0.020) | −0.7575 *** (0.003) |

| Gdp | −0.1042 *** (0.002) | −0.1612 *** (0.000) |

| Fdi | 0.0027 * (0.482) | 0.0246 ** (0.027) |

| Eco_tech | −0.0534 (0.077) | 0.0357 (0.218) |

| Env_tax | 1.0360 *** (0.000) | 0.8555 *** (0.000) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bektaş, V. Structural Determinants of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Convergence in OECD Countries: A Machine Learning-Based Assessment. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198730

Bektaş V. Structural Determinants of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Convergence in OECD Countries: A Machine Learning-Based Assessment. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198730

Chicago/Turabian StyleBektaş, Volkan. 2025. "Structural Determinants of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Convergence in OECD Countries: A Machine Learning-Based Assessment" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198730

APA StyleBektaş, V. (2025). Structural Determinants of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Convergence in OECD Countries: A Machine Learning-Based Assessment. Sustainability, 17(19), 8730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198730