4.1. Variable Selection and Justification

To empirically investigate the dynamics of China’s Juglar cycles, this study adopts a multifaceted empirical framework grounded in macroeconomic theory. The selection of variables is designed to capture both the core cyclical patterns and the unique structural and institutional features of the Chinese economy. The key variables are as follows:

Gross Domestic Product (GDP): This study uses the real GDP as the primary benchmark indicator of China’s economic activity and the reference cycle. Real GDP stands as the most comprehensive metric for assessing aggregate economic output. Its fluctuations represent the concentrated outcome of all economic activities and serve as the definitive empirical manifestation of the economic cycle, against which the behavior of other variables is typically compared.

Fixed Asset Investment (FAI): To examine the investment-driven Juglar cycle, real FAI is employed. The nominal FAI series is deflated using the fixed asset investment price index to eliminate the influence of price changes. The Juglar cycle is fundamentally characterized by cyclical fluctuations in FAI. Real FAI, being the most extensive statistic of capital formation in China, directly captures investment activities in equipment, plant construction, and infrastructure. Its inherent volatility reflects the cyclical patterns of equipment replacement, industrial upgrading, and capacity expansion, thus providing a crucial macro-level perspective on China’s investment cycle.

Government Fiscal Expenditure (GFE): The general public budget expenditure is used to proxy the stance and intensity of China’s counter-cyclical fiscal policy. To ensure consistency with other real variables, the nominal expenditure series is converted into real terms using the GDP deflator. Budget expenditure is the most direct instrument for macroeconomic management by the Chinese government. Changes in its growth rate reflect policymakers’ real-time assessment of the economic cycle and their strategic response. Its inclusion allows this study to account for the significant role of government intervention and to explore the coupling between the policy-induced cycle and the endogenous economic cycle in China.

Total Factor Productivity (TFP): Total factor productivity is incorporated to isolate the driver of economic growth beyond simple factor accumulation. TFP represents the portion of output growth attributable to technological progress, efficiency improvements, organizational optimization, and institutional change. Analyzing the cyclical component of TFP growth helps identify changes in economic efficiency and is critical for assessing the quality and sustainability of growth, beyond the short-term effects of policy stimulus. The TFP data for China used in this study are obtained from the Penn World Table (PWT), version 10.01, where it is computed based on the Solow residual methodology [

70].

Industrial Structure Upgrading (ISU): This index, defined as the ratio of the value-added of the tertiary (service) sector to that of the secondary (industrial) sector, is introduced to capture the profound structural transformation of the Chinese economy. An ascending ratio signifies a transition towards a service-oriented, advanced economic structure. This structural shift is hypothesized to alter the inherent characteristics of business cycles, including their volatility and persistence, thereby enriching the analysis of China’s economic fluctuations from a structural perspective.

All data are sourced from official institutions, including the National Bureau of Statistics of China (

https://www.stats.gov.cn/ (accessed on 17 March 2025)) and the United Nations Population Division (

https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed on 22 July 2025)), ensuring reliability and consistency. The sample covers the period from 1981 to 2024 at an annual frequency. This study utilizes exclusively publicly available aggregate macroeconomic data from official sources. No confidential or individual-level data were used, thus posing no ethical concerns.

4.2. Identification and Analysis of Juglar Cycles in China

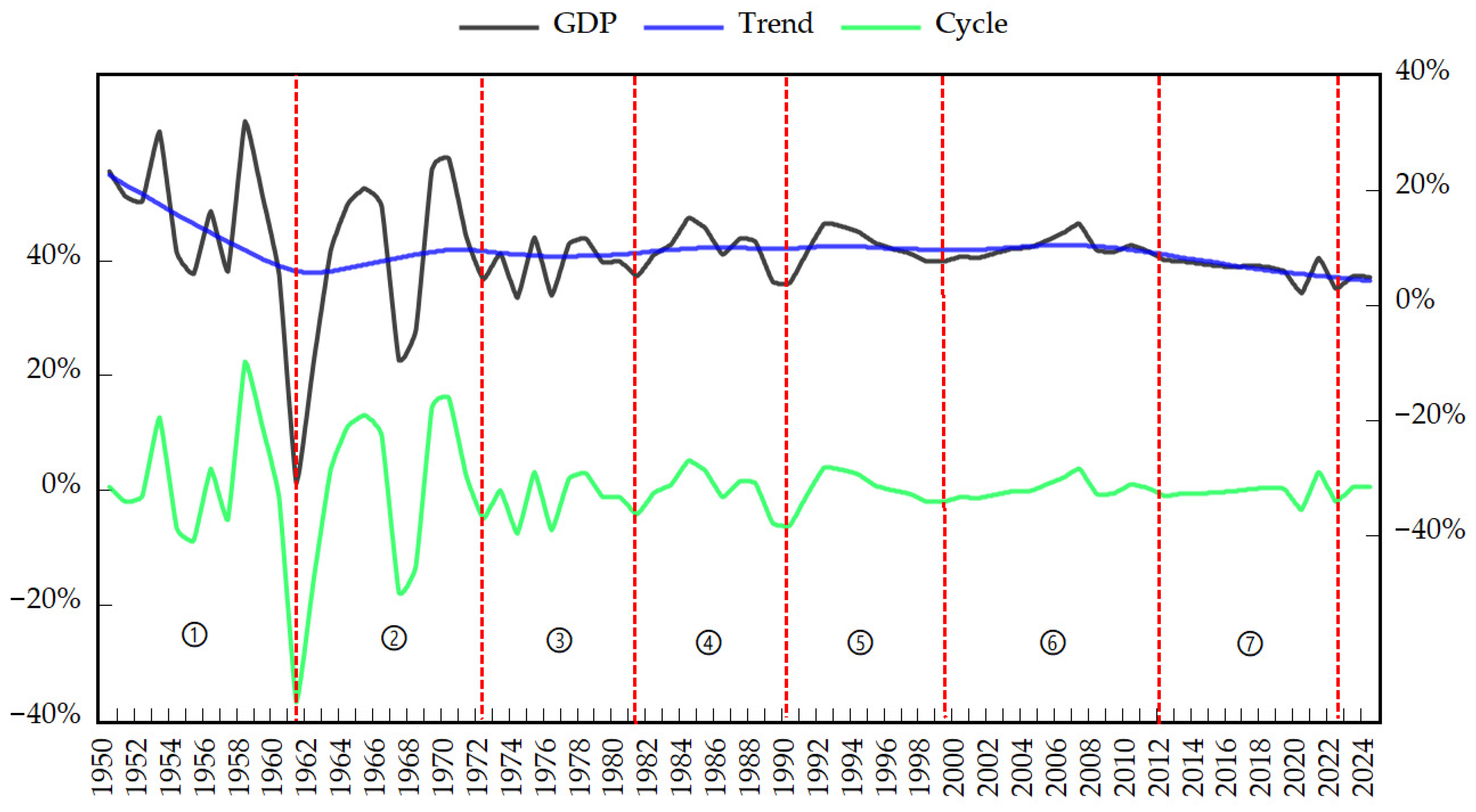

We apply the HP Filter to the GDP growth rate of China’s economy from 1950 to 2024, with the results shown in

Figure 1. The horizontal axis denotes the time series, while the left vertical axis shows the GDP growth rate after HP filtering, and the right axis indicates the trend component and the actual GDP growth rate. The black dotted line plots actual GDP growth, the green dotted line represents the cyclical component, and the blue dotted line indicates the long-term trend.

Figure 1 identifies seven distinct economic cycles in actual GDP growth: 1951–1961, 1961–1972, 1972–1981, 1981–1991, 1991–2000, 2000–2012, and 2012–2022, labeled as cycles ①, ②, ③, ④, ⑤, ⑥, and ⑦, respectively. The vertical red lines mark the initiation points of these cycles. It can be observed that economic cycles prior to 1972 exhibited pronounced boom-bust volatility, primarily driven by frequent political movements. The growth rate trend descended from its initial level, began recovering in 1961, and subsequently stabilized post-1972. China’s unique institutional characteristics—including government policy interventions, state-owned enterprise investment behaviors, and financial repression—significantly shape these economic fluctuations.

Figure 2 plots the cyclical components of China’s real GDP growth extracted using the HP filter, the Christiano–Fitzgerald (CF) filter, and the Baxter–King (BK) filter. The results demonstrate a striking concordance in the identification of China’s Juglar cycles. Specifically, the timing of the major peaks and troughs is remarkably consistent across all three methods. The visual alignment is corroborated by quantitative measures. The pairwise correlation coefficients between the cyclical series all exceed 0.85, indicating a very strong positive linear relationship. Therefore, we conclude that the chronology of Juglar cycles in China is robust and not sensitive to the choice of detrending algorithm. The evidence strongly suggests that these medium-term fluctuations are an inherent feature of the Chinese macroeconomic data rather than a statistical artifact.

Using Juglar’s methodology, we identify seven complete Juglar cycles in China’s economic trajectory from 1951 to 2024, as presented in

Table 2.

The first Juglar cycle (1951–1961) spanned 10 years and comprised three Kitchin cycles of 4, 2, and 4 years, respectively. During the recovery and boom phase (1951–1958), state-directed investment in heavy industry and infrastructure was channeled through the centralized planning system, supported by Soviet-aided projects and the First Five-Year Plan. This phase reached its zenith in 1958 with the launch of the Great Leap Forward. Subsequently, a severe Crisis phase (1959–1961) occurred, where the unsustainable policies led to a dramatic economic contraction.

The second Juglar cycle (1961–1972) lasted 11 years and encompassed two Kitchin cycles of 5 and 6 years. Its average annual GDP growth rate was 9.74%, peaking in 1970 at 25.7%. The cycle’s phases unfolded as follows: The recovery phase (1961–1964) featured a gradual rebound of public investment and economic activity following the previous crisis, as policy adjustments were implemented to stabilize the economy. The subsequent boom phase (1965–1966) experienced a significant acceleration in investment, particularly in defense and ‘Third Front’ construction, which drove economic expansion. A sharp crisis phase ensued (1967–1968), where political turmoil severely disrupted normal industrial production and investment activities, leading to a substantial economic contraction. The final recovery phase (1969–1972) was marked by a return to relative political stability and planned development. Investment and industrial output gradually recovered, culminating in a period of overheating around 1970 before growth moderated towards the end of the cycle.

The third Juglar cycle (1972–1981) spanned nine years, consisting of two Kitchin cycles of four and five years, respectively. Its average annual GDP growth rate was 7.46%. The recovery phase (1972–1976) featured moderate economic revitalization through strategic industrial investment, establishing a foundation for expansion with GDP growth averaging 4.0%. The boom phase (1977–1979) witnessed accelerated investment in comprehensive industrialization, pushing economic expansion to a peak growth of 13.19% in 1978. The crisis phase (1980–1981) emerged as structural imbalances required investment recalibration and policy adjustment, with growth moderating to an average of 8.2% during this consolidation period.

The fourth Juglar cycle (1981–1991) spanned ten years with 9.75% average annual GDP growth, encompassing two five-year Kitchin cycles. FAI grew at 18.2% annually with high volatility. The recovery phase (1982–1984) saw investment growth at 24.1% annually as reforms took hold. The boom phase (1985–1988) featured investment peaks above 27.6%, driving expansion but accumulating inflationary pressures. The crisis phase (1989–1991) experienced sharp investment contraction to 6.36% annual growth during economic adjustment. This cycle demonstrated high volatility with GDP growth ranging from 3.9% to 15.2%, reflecting investment-driven cyclical patterns throughout the reform period. This phase represented the initial stage of economic system reform, during which inflation and unemployment emerged as major challenges.

The fifth Juglar cycle (1991–2000) spanned 9 years with 10.58% average annual GDP growth, consisting of two Kitchin cycles of 4 and 5 years, respectively. FAI maintained strong growth at 23.9% annually with significantly lower volatility. During the recovery phase (1991–1992), investment growth rebounded to 34.4% annually as market reforms deepened. The boom phase (1993–1996) was characterized by sustained high investment growth at 31.1% annually, driving economic expansion while maintaining relative stability. The crisis phase (1997–2000) experienced moderated investment growth at 9.52% annually during the Asian Financial Crisis, demonstrating China’s enhanced macroeconomic resilience. This cycle exhibited moderated volatility with GDP growth ranging from 7.6% to 14.2%, reflecting China’s increasing maturity in managing investment-driven business cycles through market-oriented reforms.

The sixth Juglar cycle (2000–2012) spanned 12 years with 10.12% average annual GDP growth, encompassing three Kitchin cycles of 3, 3, and 6 years. FAI maintained robust growth at 19.8% annually, driven by infrastructure and real estate investment. The recovery phase (2000–2003) saw investment growth at 16% annually following WTO accession. The boom phase (2004–2007) featured investment peaks of 21.8% annually, fueling rapid economic expansion. The crisis phase (2008–2009) was triggered by the Global Financial Crisis, causing a sharp but brief economic contraction. In response, the Chinese government implemented a ¥4 trillion stimulus package in November 2008, with over 80% of which was directed toward infrastructure and real estate investment. This was followed by continuous policy refinements that formed a comprehensive crisis mitigation framework. This cycle exhibited sustained growth with GDP ranging from 7.9% to 14.2%, demonstrating the maturity of the investment-driven growth model during China’s accelerated globalization.

The seventh Juglar cycle (2012–2022) spanned 10 years with 6.72% average annual GDP growth, encompassing three Kitchin cycles of 3, 3, and 6 years. FAI growth moderated to 8.5% annually, reflecting the ongoing economic transition. The recovery phase (2012–2014) saw investment growth at 16% annually amid post-stimulus adjustment. The boom phase (2015–2018) featured stable investment growth at 6.9% annually, supporting quality-focused development. The crisis phase (2019–2022) experienced investment slowdown to 4.34% annually during trade tensions and the pandemic. This cycle showed moderated volatility with GDP growth ranging from 5.1% to 13.4%, reflecting China’s economic transition from high-speed to high-quality development.

The period from 2022 to 2024 exhibits characteristics that may indicate the early stages of a new Juglar cycle. However, definitive classification must await the availability of complete data and a clearer manifestation of cyclical phases.

4.3. The Role of Investment and Industrial Structure

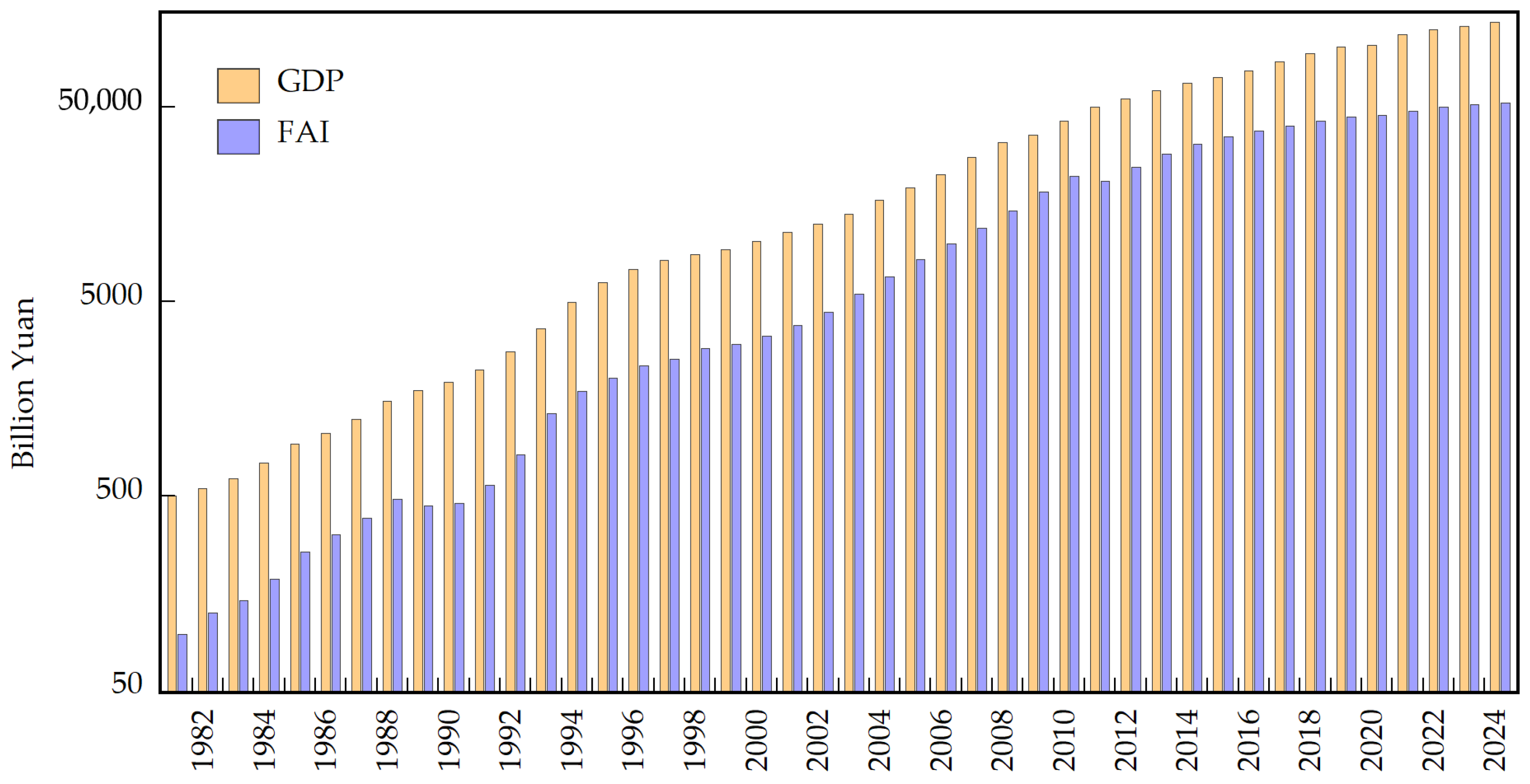

The time series data for GDP and FAI from 1981 to 2024 were analyzed. The data were sourced from various issues of the China Statistical Yearbook and the official website of the National Bureau of Statistics of China (

https://www.stats.gov.cn/; accessed on 17 March 2025). As illustrated in

Figure 3, GDP and FAI are represented by orange and blue bars, respectively. China’s FAI increased from 96.1 billion yuan in 1981 to 52.0916 trillion yuan in 2024, representing a 542-fold expansion. Over the same period, GDP grew from 494.5 billion yuan to 134.9085 trillion yuan, an increase of 273 times.

Figure 3 demonstrates that both indicators exhibit nearly parallel growth trajectories. Following the implementation of the reform and opening-up policy in 1978, China experienced rapid economic development, with annual growth rates typically ranging between 8% and 10% [

71]. By embracing market economy principles, the country significantly increased total social FAI, which played a critical role in driving economic growth.

Figure 4 identifies four distinct Juglar cycles in total social FAI: 1981–1989, 1989–1999, 1999–2011, and 2011–2020, labeled as cycles ①, ②, ③, and ④, respectively. The vertical lines mark the initiation points of these cycles. Notably, these investment cycles precede corresponding fluctuations in the GDP growth rate by 1–2 years, indicating a delayed economic impact of capital formation.

Industrial structure refers to the composition and configuration of various material production sectors within the national economy, including their respective shares in total social production. China’s industrial structure specifically denotes the proportional relationships among agriculture, light industry, and heavy industry. The primary sector encompasses agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fisheries. The secondary sector includes mining, manufacturing, electricity, gas, and water supply industries, as well as construction. The tertiary sector encompasses all other economic activities beyond the primary and secondary sectors, including the proportional relationships between distribution-related sectors and services supporting production and daily life.

Figure 5 displays the trend of GDP and the added values of the three industries from 1978 to 2024. The required data were collected from the issues of the China Statistical Yearbook and the official website of the National Bureau of Statistics of China (

https://www.stats.gov.cn/ (accessed on 17 March 2025)). The black curve represents GDP, the red curve represents the added value of the primary industry (PIVA), the blue curve represents the added value of the secondary industry (SIVA), and the green curve represents the added value of the tertiary industry (TIVA).

Figure 6 shows the proportion of added value of the three industries to GDP. The red, blue, and green curves represent the proportion of added value from the three major industries to GDP. These figures reveal that since the economic reforms began in 1978, China’s economy has embarked on a path of rapid development, with continuous growth in GDP and the added value of the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries. The industrial structure has undergone profound adjustments and optimizations, resulting in significant changes in the proportion of added value from these three sectors to GDP.

Since the reform and opening-up policy began in 1978, China’s economy has embarked on a high-speed development track, with GDP and the added value of the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries continuously increasing. The industrial structure has undergone deep adjustments and optimizations, leading to significant changes in the proportion of added value of the three industries to GDP. The proportion of the primary industry has been steadily declining; in 1978, it accounted for 27.69% of GDP, dropping to 14.68% by 2000. In the 21st century, this ratio continued to decline, reaching just 6.78% by the end of 2024. This trend reflects the gradual reduction in agriculture’s share in the national economy due to technological advances and industrialization progress. Despite this, agricultural modernization accelerated through measures like technological empowerment and large-scale operations, which led to continuous improvements in production efficiency and quality. The secondary industry displayed phase-specific fluctuations from 1978 to 2006; the proportion of added value of the secondary industry in GDP showed an upward trend, peaking at 47.56% in 2006. The subsequent decline was largely driven by strategic national policies, specifically the Supply-Side Structural Reforms and stringent environmental protection laws enacted after 2015. These policies deliberately phased out excess capacity in heavy industries (e.g., steel, coal) and reoriented investment towards advanced manufacturing and services, accelerating the sector’s relative contraction.

Subsequently, its proportion gradually decreased to 36.48% by 2024 due to economic restructuring and environmental policies. During this period, China’s industry transitioned from traditional extensive models to modern intensive ones, and from labor-intensive to technology and capital-intensive structures. On one hand, traditional industries have upgraded through technological transformation, phasing out outdated capacities, and enhancing production efficiency and product quality.

On the other hand, emerging industries such as high-end equipment manufacturing, new energy, and new materials have expanded rapidly, becoming new growth points in the industrial economy. The tertiary sector has also undergone significant expansion, increasing its share of GDP from 24.6% in 1978 to 39.79% by 2000. By 2024, it accounted for a dominant 56.75% share, underscoring its pivotal role in the economic structure. Continuously propelled by technological innovation and consumption upgrades, high-tech and modern services within this sector are expected to serve as key engines for promoting high-quality economic development in China. The economic composition in 2024 (primary: 6.78%, secondary: 36.48%, tertiary: 56.75%) reflects this shift towards a new development paradigm. This structure aligns with China’s broader strategic goals of high-quality growth, underpinned by the dual-circulation strategy that leverages a robust domestic service sector, and supports the transition to a greener economy in line with carbon neutrality objectives.

As illustrated in the annotated

Figure 6, these structural shifts are closely linked to key historical policy milestones. The accelerated decline of the primary sector and the rapid expansion of the secondary industry after 2001, for instance, can be largely attributed to China’s accession to the WTO, which more deeply integrated the nation into global supply chains. Similarly, the stimulus measures implemented after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis temporarily boosted secondary-industry investment. The more recent decline in the secondary sector’s proportion and the simultaneous rise of the tertiary sector, evident from around 2010 onward, are consistent with strategic policy shifts towards environmental protection and a rebalancing of the economy toward consumption and services.

Furthermore, from a macroeconomic perspective, a given total resource endowment will yield differing economic benefits depending on allocation methods and structural arrangements. In other words, under identical social resource endowments, different industrial structures lead to distinct economic growth outcomes, with the structure of industrial investment representing a critical determinant of economic growth.