1. Introduction

Sustainability has become a ubiquitous term in corporate and political discourse, frequently used as a marker of organizational responsibility but often compromised when exposed to economic or political pressures. These concerns are consistent with recent supervisory and investor analyses pointing to greenwashing risks and reporting complexity within the EU framework, underscoring the importance of stability and feasibility in institutional signals [

1,

2,

3]. The prevalence of sustainability-related language in corporate communications continues to grow, yet this rhetorical commitment is not always matched by substantive action. Research on corporate sustainability strategies shows that without strong institutional frameworks, such commitments risk devolving into symbolic compliance rather than genuine transformation [

4,

5,

6].

Within the European Union (EU), the European Green Deal was launched as an ambitious roadmap to achieve climate neutrality by 2050. However, recent developments—Including the “Green Omnibus” package and delays in implementing key instruments such as the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD)—signal a weakening of institutional resolve [

7]. While officially framed as measures to reduce administrative burdens and protect competitiveness, these changes risk being interpreted as concessions to short-term economic and political pressures.

This conceptual review builds on institutional theory [

5,

8,

9] and organizational sustainability scholarship [

10,

11,

12,

13] to examine how regulatory instability shapes corporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) behavior. Specifically, it investigates: (i) how unstable policy frameworks influence corporate sustainability strategies, (ii) how organizations interpret and respond to ambiguous sustainability signals, and (iii) what governance mechanisms can embed long-term responsibility in an environment increasingly dominated by short-term incentives [

14,

15]. By integrating literature from organizational theory, corporate governance, and sustainability policy, the article highlights the critical role of consistent institutional signals in fostering structural transformation.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

This section reviews key theoretical perspectives and empirical insights that inform the analysis, focusing on how temporal dynamics, institutional structures, governance mechanisms, and organizational sensemaking shape sustainability strategy.

2.1. Temporal Myopia and Systemic Short-Termism

Short-termism is not merely a managerial oversight; it is a systemic feature of contemporary economic and political systems. Embedded in the cultural logic of modern capitalism, it manifests through quarterly reporting cycles, short electoral mandates, volatile shareholder expectations, and performance-based funding models across sectors, including NGOs and academia [

14,

15]. These structural characteristics disincentivize long-term thinking and strategic resilience. In the sustainability context, this temporal compression undermines the cultivation of foresight, patience, and institutional memory—qualities essential for environmental and social transformation [

10,

13]. This aligns with the natural-resource-based view, which frames sustainability as a long-term strategic capability linked to resource dependence and competitive advantage [

16].

2.2. The EU’s Sustainability Commitments as Institutional Signals

Building on institutional theory—which predicts that organizations reflect the stability and coerciveness of their policy environment—this subsection situates the EU’s commitments within that lens. We show how the trajectory of the Green Deal, and the 2024–2025 adjustments to key instruments, constitute institutional signals that propagate organizational short-termism.

Institutional theory offers a foundational lens for understanding these dynamics. DiMaggio and Powell describe how organizations adopt the values, norms, and structures of their institutional environment—a process termed institutional isomorphism [

8]. When public institutions signal inconsistency or conditionality in sustainability commitments, businesses often mirror that ambivalence, rendering sustainability provisional, optional, or symbolic rather than strategic. This tendency is reinforced when performance metrics or investor expectations favor short-term returns, leading even committed managers to defer transformative initiatives [

14,

15].

Recent assessments warn that parts of the EU’s disclosure framework risk bureaucratic overload and unintentionally encourage symbolic compliance if complexity outpaces usefulness. Investor groups flagged that the first ESRS package could even raise greenwashing concerns by weakening comparability and auditability of disclosed data [

3]. Supervisors have likewise documented greenwashing risks across the financial value chain and highlighted uneven supervisory practices, reinforcing the need for clear, credible, and enforceable rules [

1,

2].

2.3. Sustainability as a Governance Issue

Sustainability outcomes are closely linked to governance structures that institutionalize long-term thinking. In particular, the natural-resource-based view underscores how firms’ resource strategies and environmental dependencies shape their competitive position [

16]. Eccles, Ioannou, and Serafeim [

12] show that firms embedding sustainability into board oversight and strategic planning—despite short-term trade-offs—are better positioned to deliver genuine environmental and social value. Their work reframes sustainability from a communications or branding concern into a structural and leadership imperative.

2.4. Sensemaking and Strategic Interpretation

Recent scholarship has turned to the concept of sensemaking, defined as the cognitive process through which individuals or groups interpret and act upon environmental cues [

17]. When sustainability is framed internally as a reputational safeguard rather than a strategic imperative, it often results in shallow or symbolic implementation. Dziubaniuk et al. [

18] demonstrate that divergent stakeholder interpretations of sustainability can undermine institutional coherence, underscoring the importance of internal alignment and interpretive clarity—particularly when external cues are weak or shifting.

A consistent theme across this literature is that organizational sustainability is not driven solely by internal values or leadership commitment; it is profoundly shaped by the consistency, coherence, and credibility of external institutional frameworks. While a strong internal vision is important, it remains insufficient in the absence of policy environments that provide reliable, long-term signals. Policy backtracking or dilution not only alters compliance requirements but also erodes the strategic foundations for sustainability investment, fostering risk aversion, short-term fixes, and what Christensen et al. term “

aspirational talk” [

4]. Conversely, strategic continuity in policy acts as an institutional anchor, legitimizing deep transformation, enabling long-term planning, and fostering innovation aligned with planetary boundaries. Just as ecological systems require stability to thrive, organizational sustainability requires coherent policy frameworks that transcend political and economic cycles.

EU-level supervision further illustrates how ambiguous external cues can be read as permission for

aspirational talk rather than substantive change: ESMA reports detail patterns of mislabeling and weak verification in sustainable finance [

1,

2]. Industry reviews also point to recurrent symbolic implementation in operational settings, underscoring how sensemaking under uncertainty prioritizes interpretive minimalism and low-cost compliance [

19]. Indeed, corporate environmental policies themselves can become a form of greenwashing when they lack substantive organizational backing [

20].

2.5. Methodology and Data Basis

This article adopts a conceptual review approach, synthesizing insights from institutional theory, organizational behavior, and sustainability policy analysis. The selection of literature and policy documents was guided by three criteria: (i) recency (2020–2025, to reflect ongoing EU policy developments), (ii) relevance (focus on institutional stability, corporate ESG strategies, and policy volatility), and (iii) representativeness (inclusion of both academic sources and EU policy documents to capture theoretical and practical perspectives).

The figures presented are illustrative visualizations rather than empirical datasets. They are derived from mock data modeled on secondary sources such as Statista trend reports, regulatory briefings, and industry surveys. Estimates (e.g., CSRD delays, ESG fund flows, ESG board oversight) were generated by extrapolating from reported policy postponements and survey-based expectations of corporate compliance. Their purpose is to illustrate institutional and organizational dynamics conceptually, not to provide statistically validated results.

This approach allows the article to highlight systemic patterns of short-termism in sustainability governance, while recognizing the absence of firm-level empirical testing.

3. EU Sustainability: Shifting Signals and Retrenchment

Over the past decade, the European Union (EU) has emerged as a global standard-setter in sustainability governance, with the European Green Deal serving as its flagship initiative. Introduced in 2019, the Green Deal articulated a strategic roadmap to achieve climate neutrality by 2050, leveraging regulatory mechanisms to integrate sustainability into corporate strategy, finance, and reporting [

21]. In 2025, debate coalesced around a proposed Clean Industrial Deal (CID), presented as an industrial-competitiveness complement to decarbonisation. While the Commission emphasizes cheaper energy, lead markets, financing and skills, critics caution that technology-neutral vagueness and administrative “simplification” could dilute earlier sustainability ambitions [

22,

23,

24]. Scholarly perspectives echo this tension: some argue for pragmatic sustainability that rebalances social and industrial needs without abandoning climate goals [

25], while others warn that legal-technical shifts in the EU’s sustainable-finance regime can re-open trade-offs and greenwashing loopholes [

26]. Read as institutional signals, such moves can heighten corporate short-termism unless anchored in credible, stable policy design.

However, policy developments in 2024 and 2025 have introduced substantial uncertainty into this framework. Rather than reinforcing institutional commitment, these changes risk signaling a strategic retrenchment. Among the most consequential is the Omnibus Simplification Package, introduced by the European Commission in early 2025. This legislative bundle proposed significant delays and revisions to two cornerstone measures of the Green Deal: the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) [

7].

Marketed as a pragmatic response to concerns over administrative burden, compliance costs, and business competitiveness, the package includes the so-called “Stop the Clock” Directive, which extends CSRD implementation deadlines by up to two years for many reporting entities. While framed as a technical adjustment, the symbolic implications are considerable—reinforcing the perception that sustainability commitments remain vulnerable to short-term economic and political pressures [

7].

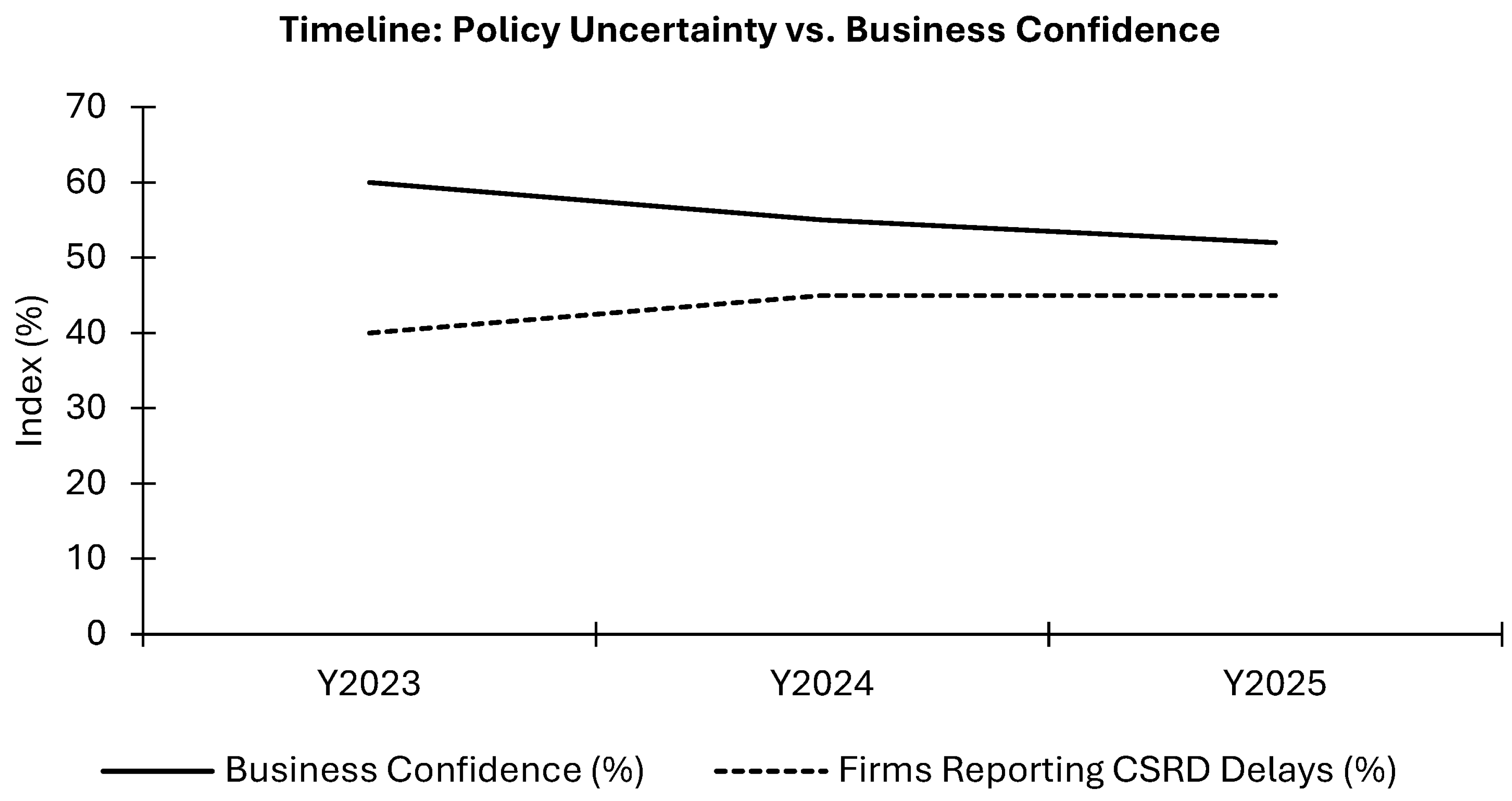

These policy modifications have had visible effects on both capital markets and public trust. As illustrated in

Figure 1, ESG fund inflows have plateaued while delays in CSRD implementation have increased, reflecting declining confidence in ESG regulation. This divergence reflects a widening credibility gap between organizational signaling and stakeholder expectations [

4,

11,

27]. The perception is growing that sustainability rhetoric increasingly lacks operational substance, particularly when regulatory enforcement appears conditional or delayed.

The solid line depicts the decline in business confidence in ESG regulation from 2023 to 2025, while the dashed line shows the estimated percentage of firms reporting delays in Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) implementation. Together, these trends illustrate how weakening regulatory commitment—evidenced by widespread CSRD delays—coincides with reduced confidence in ESG, highlighting the destabilizing effect of institutional ambiguity on long-term corporate sustainability planning.

By weakening the pace and clarity of policy implementation, the EU risks eroding the institutional momentum required for sustained corporate transformation. Strategic ambiguity disrupts firms’ long-term planning horizons and signals to the broader market that climate objectives are reversible. In a global context, where consistency in sustainability governance is a key determinant of investor confidence, competitive advantage, and corporate accountability [

12,

27,

28], such reversals carry significant economic and reputational risks.

While some stakeholders contend that recent regulatory adjustments provide firms with additional time to prepare, others interpret them as a de-prioritization of environmental accountability. The World Wide Fund for Nature has described the Omnibus Simplification Package as a “devastating blow” to the EU’s environmental agenda, cautioning that the rollback of enforcement mechanisms sends conflicting market signals and undermines institutional legitimacy [

7].

From an organizational theory perspective, such policy reversals introduce institutional uncertainty, which directly influences how firms interpret and respond to sustainability imperatives. Oliver [

9] argues that the likelihood of substantive organizational change depends on the perceived stability and enforceability of external pressures. When regulatory requirements are ambiguous or subject to frequent revision, firms engage in decoupling—the symbolic adoption of sustainability practices without corresponding operational changes [

5].

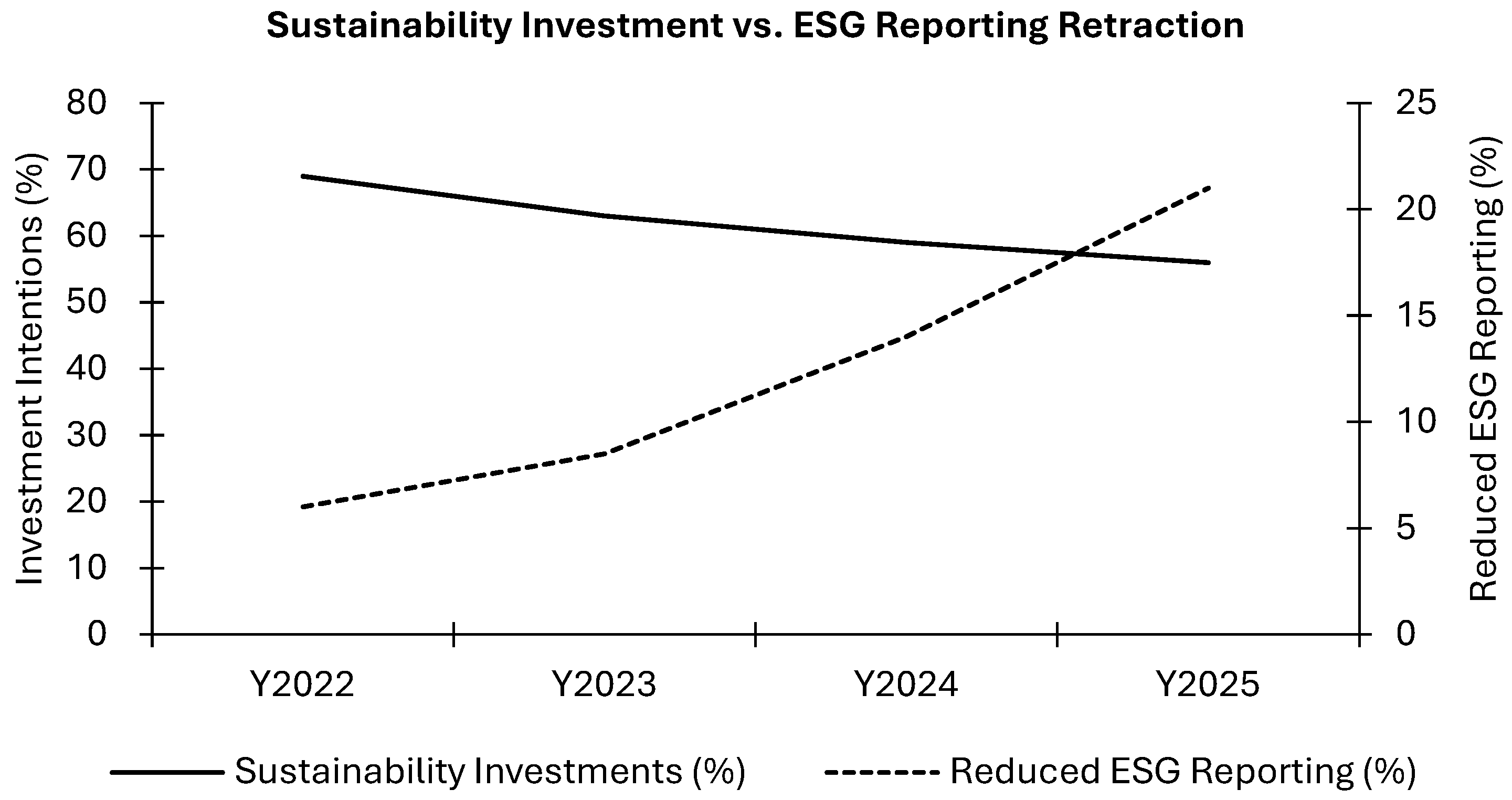

Figure 2 shows how sustainability investment intentions have declined in parallel with an increase in ESG reporting retractions, underscoring the organizational consequences of policy uncertainty. This pattern demonstrates a reactive withdrawal of sustainability efforts in the absence of consistent and credible policy signals.

The solid line shows the percentage of firms intending to increase sustainability-related investments, while the dashed line indicates the percentage of firms reducing their ESG reporting activities. The opposing trends highlight how policy uncertainty and weakening institutional signals can simultaneously deter new sustainability commitments and encourage retreat from transparency obligations.

The risk associated with weakening regulatory frameworks is not only reputational but also behavioral. Strong and consistent regulation is critical for aligning corporate conduct with societal expectations [

11]. In the absence of clear and enforceable mandates, firms can postpone investments in sustainable infrastructure, human rights due diligence, or emissions-reduction technologies—particularly when competitors are afforded similar regulatory leniency.

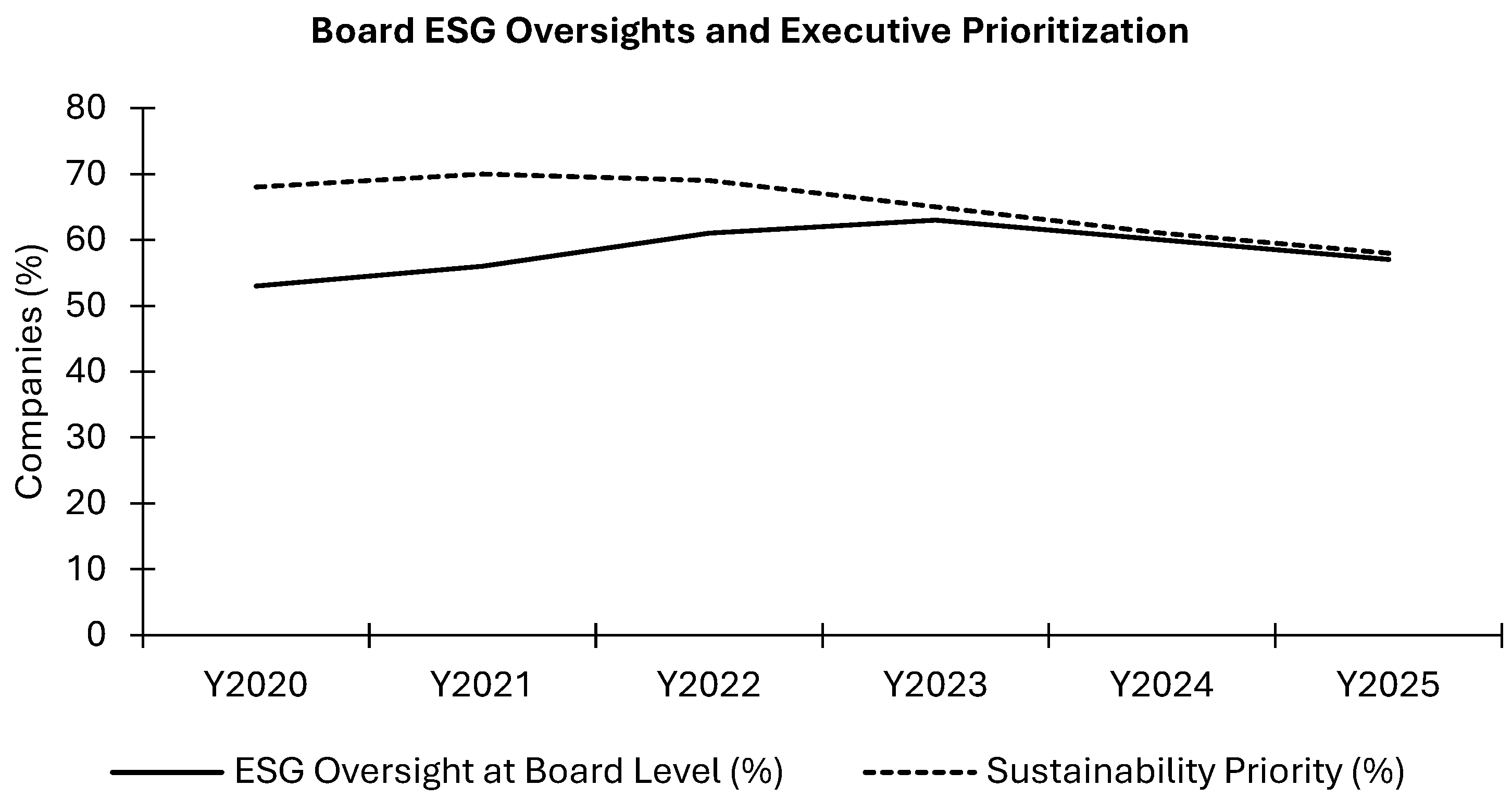

Recent corporate governance research further indicates that policy inconsistency undermines the integration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations at the board level [

27]. When regulatory expectations are unstable, sustainability risks losing its position as a strategic priority and is instead reframed as a compliance obligation—one that can be deferred, deprioritized, or delegated.

Figure 3 illustrates this shift: both ESG oversight at the board level and the prioritization of sustainability within executive decision-making have declined steadily over time, signaling a broader institutional weakening.

The solid line represents the share of boards with formal ESG oversight, while the dashed line shows the share of executives identifying sustainability as a strategic priority. Both measures have declined steadily since 2022, illustrating how policy inconsistency and weakening institutional signals can diminish sustainability’s strategic role in corporate governance.

In summary, the EU’s recent policy adjustments, though politically expedient, risk widening the gap between long-term sustainability objectives and their enforcement. For regulation to catalyze systemic transformation, it must be consistent, binding, and shielded from short-term political shifts. Absent such stability, organizations do not commit the resources required to integrate sustainability into their core strategies.

4. Organizational Impacts of Policy Retraction

The credibility gap identified in the previous section has direct consequences for corporate behavior. When regulatory stability weakens, firms adjust their strategies—not necessarily due to a loss of interest in sustainability, but out of caution. Regulatory certainty is a critical factor in shaping strategic risk assessments, and as institutional theory and contingency-based management show, organizations reflect the clarity—or ambiguity—of their external environment [

8,

9].

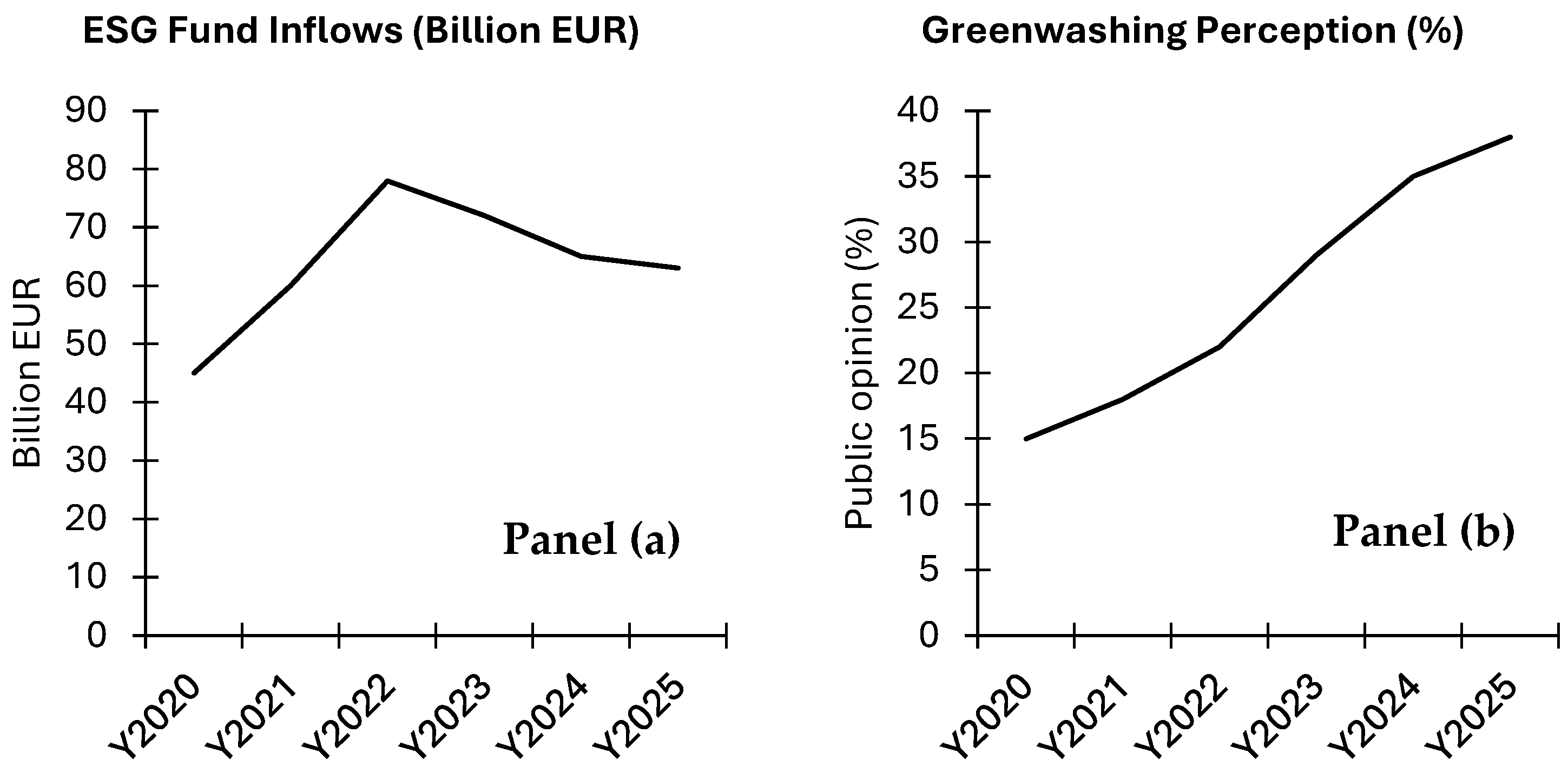

One of the most immediate outcomes of the EU’s recent regulatory delays is a slowdown in ESG-related investment. Many firms are reassessing or deferring initiatives that had been planned to meet CSRD or CSDDD requirements. This effect is not purely theoretical: market data indicate that ESG fund inflows across Europe have plateaued, and in some cases declined, since 2024—a period that aligns closely with the EU’s policy retreat.

As illustrated in

Figure 4, delays in CSRD implementation coincide with a measurable reduction in business confidence in ESG regulation. These parallel trends reinforce the relationship between policy instability and organizational uncertainty, highlighting how weakened institutional signals can undermine both investor trust and corporate commitment to sustainability.

Panel (a) shows annual ESG fund inflows in billions of euros, highlighting a plateau and subsequent decline after 2022. Panel (b) depicts the percentage of the public reporting concern about corporate greenwashing, which has risen steadily over the same period. Together, these trends illustrate how weakening policy signals can coincide with declining financial commitment to ESG initiatives and increasing public skepticism toward corporate sustainability claims.

As shown in

Figure 4, ESG fund inflows began to stagnate after 2022, while public concern over greenwashing increased steadily. This divergence underscores the risk of symbolic compliance when regulatory consistency is lacking. Such a shift aligns with findings by Eccles and Klimenko [

28], who argue that when policy environments signal regulatory softening, ESG initiatives lose strategic momentum—not because business leaders abandon values-based commitments, but because strategic ambiguity generates operational hesitation.

The retreat of firm-level ESG ambition is not solely financial; it is also symbolic. In the context of weaker oversight and reduced reporting obligations, some companies revert to symbolic compliance—employing sustainability rhetoric in communications without implementing substantive operational changes [

4,

5]. The practice of greenwashing, once thought to be on the decline, appears to be regaining prominence under these conditions.

The problem also manifests internally. As social systems, organizations are sensitive to shifts in their institutional environment, and policy retraction can alter the internal climate. Periods of policy ambiguity are often accompanied by declining employee engagement in sustainability initiatives—particularly among middle managers, who are both key implementers of change and deeply embedded in performance-driven contexts [

17,

29]. In such settings, sustainability is deprioritized in favor of conventional key performance indicators (KPIs) such as cost reduction, revenue growth, and quarterly financial results.

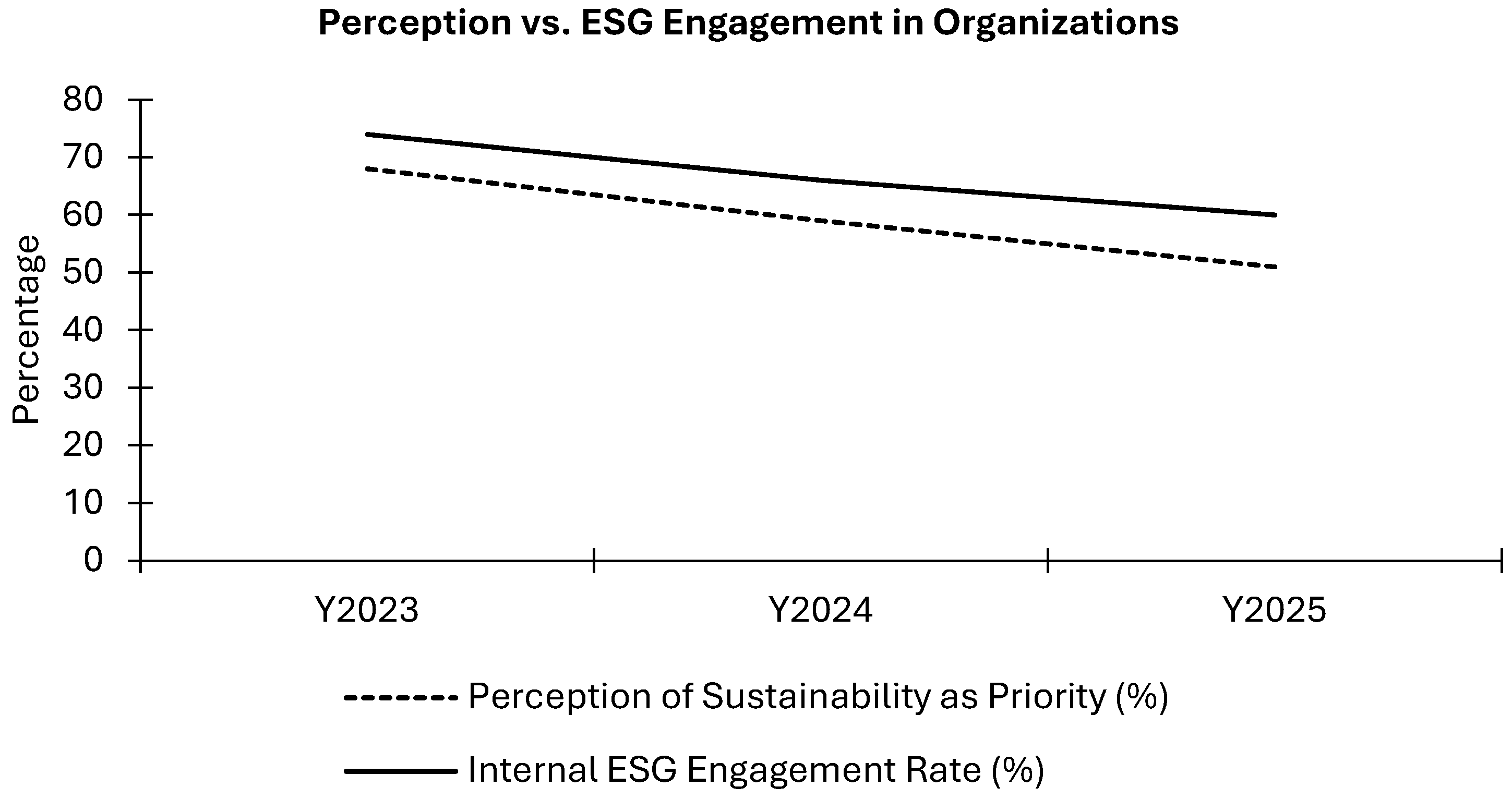

To illustrate the strategic impact of regulatory volatility,

Figure 5 presents a parallel timeline showing the decline in sustainability investment intentions alongside the increase in ESG reporting reductions among EU companies.

The solid line shows the percentage of employees and managers perceiving sustainability as a strategic organizational priority, while the dashed line represents the share of employees engaged in ESG-related initiatives. Both measures decline over the observed period, indicating how policy uncertainty and weakened institutional signals can erode internal commitment to sustainability and reduce active participation in ESG programs.

These findings reinforce a well-established principle in sustainability management: consistent and credible regulation is a critical enabler of deep organizational commitment [

4,

9]. When such consistency is weakened or withdrawn, firms adopt reactive behavior—risk avoidance, minimal compliance, and the postponement of strategic initiatives—rather than pursuing innovation or creating long-term value. In this context, regulatory volatility does not merely slow progress; it actively reshapes corporate priorities in ways that undermine transformative change, setting the stage for the broader implications discussed in the following section.

5. Results and Interpretation

This review identifies a consistent pattern linking regulatory volatility to declining corporate sustainability engagement. Across multiple indicators—ESG fund inflows, public perception of greenwashing, board-level ESG oversight, and internal employee engagement—there is a measurable deterioration following the EU’s recent policy delays.

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 collectively show that weakening external policy signals corresponds with reduced sustainability investments, diminished strategic prioritization, and increased risk of symbolic compliance.

These trends show that regulatory stability functions not only as a compliance driver but also as a strategic anchor for corporate sustainability. When this anchor is removed, organizations shift towards short-term risk management, deprioritizing innovation and long-term value creation in favor of immediate operational and financial performance. This dynamic, observed consistently across the reviewed data and literature, underscores the need for sustained, credible policy frameworks that maintain organizational momentum toward environmental and social goals.

6. Discussion

The implications of these findings extend beyond legislative design into the broader realm of institutional signaling. Regulatory frameworks not only mandate compliance but also shape expectations, legitimize long-term planning, and act as normative anchors within complex organizational fields. When such frameworks become inconsistent or vulnerable to short-term political pressures, the perceived legitimacy of sustainability initiatives is undermined.

EU monitoring shows uneven progress toward the SDGs across Member States and goals, highlighting persistent trade-offs between competitiveness and ecological limits [

30]. This strengthens the argument that predictable and coherent frameworks are not only a legal necessity but a strategic anchor enabling firms to translate sustainability from rhetoric to operations.

Empirical studies underscore the critical role of stable policy signals. Minutolo et al. [

31] demonstrate that sustainability reporting functions as a signal to stakeholders, directly influencing perceptions and organizational behavior. Similarly, the Morgan Stanley Institute for Sustainable Investing [

28] reports that institutional investors increasingly seek policy environments that provide stability and predictability to support long-term sustainable investments. At the firm level, proactive sustainability strategies are also shown to positively influence corporate sustainability performance [

32].

Strategic inconsistency erodes trust not only between regulators and corporations but also within organizations themselves. This erosion can foster symbolic compliance, whereby sustainability language is adopted without corresponding operational changes [

4]. In the context of SMEs, tensions between sustainability performance and reporting can reinforce this risk of symbolic compliance [

33]. Although retrenchment during periods of economic or political crisis can seem pragmatic, such responses are short-sighted. Crises should serve as catalysts for strengthening—not diluting—sustainability commitments. Embedding these commitments within durable institutional structures, such as constitutional mandates or independent oversight bodies, can shield long-term objectives from cyclical political shifts.

Moreover, evidence from Iannone et al. [

34] shows that ESG investments often demonstrate greater resilience during periods of market volatility than traditional investments, reinforcing the strategic value of integrating ESG factors into long-term corporate and investment planning.

7. Limitations

This study is conceptual in nature and does not include primary data collection such as interviews, surveys, or case studies. While this approach enables a broad synthesis across disciplines and institutional contexts, it inherently limits the empirical validity of the findings.

A further limitation concerns the use of modeled data: all figures are based on secondary sources and mock trend estimates, which are intended solely for illustrative purposes. They should not be interpreted as quantitative evidence.

Finally, the scope is restricted to the European Union. Caution should be exercised when generalizing to regions with different institutional architectures or political dynamics.

Future research should address these gaps through empirical and longitudinal studies, including: (i) multi-sector corporate case studies, (ii) surveys on managerial perceptions of regulatory volatility, and (iii) cross-regional comparisons to assess whether similar patterns of policy instability and organizational short-termism emerge outside the EU.

8. Conclusions

This review shows that policy instability in the EU directly undermines corporate ESG engagement. When disclosure and due-diligence rules are delayed or diluted, firms shift toward symbolic compliance, defer investment, and weaken board-level oversight and employee engagement. In short, sustainability performance mirrors the credibility and continuity of institutional signals.

Implications for policy. Treat sustainability as governance architecture, not communications. Priority actions are: (i) hard-wiring continuity through statutory provisions and legal “non-retrogression” safeguards that prevent ad hoc rollbacks; (ii) independent oversight with audit/enforcement capacity across reporting and finance rules; (iii) stable, phased timetables for CSRD/CSDDD that avoid retroactive scope changes and maintain comparability; and (iv) aligned capital signals (taxonomy, SFDR, public procurement) that reward long-horizon investment.

Implications for firms. Anchor sustainability in board charters and executive incentives, link strategy to time-bounded transition plans, and use scenario analysis to keep investment on track when politics fluctuate. These steps convert external uncertainty into internal commitment.

The evidence assembled here supports a clear claim: durable sustainability outcomes require consistent, enforceable policy that persists beyond electoral and market cycles. Without that anchor, organizations reallocate attention to short-term targets, stalling structural transformation.

This article is conceptual; figures are illustrative. Future work should test these mechanisms empirically through multi-sector case studies, manager surveys on policy volatility, and longitudinal analyses of EU firms.