Abstract

We aim to assess the difference in integrated report conformity towards the IIRC framework for companies who produce it voluntarily and those who were enforced. We study Brazilian companies because due to regulatory requirements, state-owned companies are mandated to publicly disclose an integrated report, while others may choose to do so voluntarily. The analysis involved a total of 1673 observations in panel data from 2018 to 2021 and was developed through six explanatory econometric models. A checklist based on the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) framework was used to conduct a survey on the reports to assess their conformity levels. The conformity level of listed companies that disclose IR is higher than that of state-owned companies, and it is primarily influenced by firm size, age, and board composition (board size and diversity). The hypothesis that mandatory disclosure would be associated with higher conformity level was not supported by our result, and empirical evidence is provided on the low effectiveness of integrated reporting enforcement. Moreover, evidence that women’s participation on the board of directors enhances IR disclosure may encourage future studies to delve deeper into this issue of diversity. Given that the IR framework reflects a holistic view of value creation, the study also reinforces the potential of Integrated Reporting as a tool to support and communicate alignment with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

1. Introduction

Integrated Reporting (IR) is an innovative tool for reporting financial and non-financial information in a single document. It provides a multi-capital lens—encompassing financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social and relationship, and natural capitals—to understand the trade-offs and interdependencies among SDGs, while offering a structured five-step process (understanding sustainable development issues; identifying material issues; developing strategy through the business model; fostering integrated thinking, connectivity, and governance; and preparing the integrated report) for their effective incorporation into corporate reporting and decision-making [1].

Beyond disclosure, it is necessary to observe the quality of the integrated report, a theoretical construct that includes the level of conformity of the content presented in the report with the structure developed by the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) [2]. This phenomenon has been investigated both from the perspective of the implementation process and the nature of the information disclosed [3,4,5]. Ref. [4] showed, for a limited sample of companies, that the quality of integrated reporting falls short of market expectations. Typically, organizations apply the IR framework but do not provide relevant features, such as the various categories of capitals, business models, and details about their perspectives, prioritizing disclosure over content quality.

A systematic literature review developed by [6] demonstrates a growing emphasis on sustainability and integrated reporting (IR), particularly after 2020. In the same study, corporate governance, disclosure practices, and alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are presented as central issues. Despite the increase in publications and the diffusion of theoretical frameworks such as stakeholder, legitimacy, institutional, and agency theories, the authors observe that challenges remain regarding the depth and quality of the information disclosed. This indicates that, beyond regulatory or voluntary requirements, organizations face increasing pressure to ensure not only the formal adoption of the IR framework but also the substantive integration of relevant content that enhances transparency and accountability in line with global sustainability objectives.

Bringing the potential of IR as a mechanism for corporate engagement with the SDGs into an empirical perspective, ref. [7] analyzed the top market-leading public listed companies in Malaysia between 2016 and 2020 and identified a significant increase in SDG-related disclosures, rising from 14% of companies in 2016 to 78% in 2020, mainly concerning SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Action). The study revealed that higher-quality integrated reports are associated with more comprehensive and meaningful disclosures. These findings suggest that IR, when implemented with substantive commitment, can move organizations beyond symbolic adoption, fostering more integrated and transparent reporting practices aligned with the 2030 Agenda.

In Brazil, there is a duality: state-owned entities are required to disclose reports on corporate social responsibility, while private entities do so voluntarily. This represents a shift in the usefulness of the disclosed information by parties associated with the government, as the integrated report shifts the focus to society, providing a detailed description of the resources and the value created in the period, in opposition to the model used before, which was focused on the acquisition of materials and simple compliance with auditing from public agencies, who hold enough enforcement power to demand additional data whenever needed [8].

Additionally, examining the effects on Integrated Reporting (IR) conformity under mandatory and voluntary regimes within a setting of coexistence in the same country reinforces this study’s main contribution to the literature and addresses the scarcity of evidence on the topic. To the best of our knowledge [9], conducted in South Africa, is among the few studies that tackle the mandatory-versus-voluntary dilemma using a before–after design of the mandate and without directly measuring IR conformity/quality, which underscores this study’s innovative and complementary contribution. In line with studies that indicate that firms have been pressured to increase their SDG-related disclosures, we also should expect high-quality reports. Even so, when a company is enforced, it may not have the skills or the commitment needed and deliver a poor report to comply with the rule. Therefore, we aim to compare the conformity level of integrated reports produced by companies who are mandated to produce them, to those voluntarily reported. We contribute to the current literature by providing a comparison between voluntary and mandatory reporting that may clarify if the imposition of this model may translate into a qualified disclosure.

The choice of the IIRC framework is associated with its importance: besides being cited as a source in the TCU No. 170/2018, it was the basis for an orientation provided by normative bodies of the accounting profession in Brazil towards the voluntary implementation of integrated reporting. To achieve this, we produced a checklist based on the studies of [10], which was used to score the integrated report of Brazilian companies, measuring their conformity level. We then estimate a set of regression analyses to assess whether mandatory disclosure, controlled by several firm characteristics, is associated with lower conformity. Broadly, our results indicate that SOC have lower conformity and that larger, older, and more diverse firms tend to have better scores.

2. Literature Review

There are several studies on the determinants associated with IR conformity, considering the realities of many countries, but a consensus has not yet been reached. Among the determinants are company size, industry sector, cultural context, organizational ownership structure, and corporate governance [11,12,13]. Usual theoretical frameworks to explain this phenomenon include organizational legitimacy [14], agency [15] or stakeholder theories [13]. Based on a meta-analysis of 61 studies published between 2015 and 2021, ref. [16] identify that board independence, the existence of a corporate social responsibility committee, institutional ownership, and having the financial statements audited by a Big Four firm are significantly associated with higher IR quality.

There is evidence that company size is positively associated with the expansion of integrated reporting practices [17,18]. The larger the organization, the greater the adherence to IR as a methodology for reporting information [19,20,21,22], although [23] have refuted the positive relationship between company size and IR adoption. It is worth noting that larger corporations value reputation and meeting the interests of their stakeholders [17,24,25].

In addition, there is a direct association between company age and the quality of IR: older companies are inclined to disclose a greater amount of information in their integrated reports, positively influencing their quality. This occurs because such companies aim to maintain their reputation and their legacy in the market through compliance with laws and regulations [26,27]. Moreover, older organizations typically face less uncertainty and instability [28,29]. This stability, in turn, contributes to a positive correlation between company age and IR compliance [21,30,31]. In contrast, ref. [32] did not find strong evidence on the relationship between company age and Integrated Reporting quality.

The board of directors can influence this phenomenon. Larger boards offer a wide diversity of knowledge and experience, contributing to stakeholders’ protection [33], which supports quality in complex processes, such as integrated reporting [34]. Other research corroborates this finding, showing that board size has a significant association with IR compliance, emphasizing the need for efficient boards to enhance these reports [21,35,36,37].

Gender diversity on the board of directors can affect the decisions made by the board [38] and influence the extent of non-financial statements [39]. The presence of women on boards has a positive impact on corporate social responsibility performance [40,41], the quality of environmental disclosure [42], the materiality level of IR [43], and both the likelihood of IR adoption [44] and its quality [21,37,45]). Ref. [18] further reinforce, among others, the idea that gender diversity on the board and company size significantly and positively influence disclosures, both qualitative and quantitative, especially those with a prospective nature, directly affecting the level of compliance with integrated reporting disclosure. This relationship also finds support by [46], but was not found by [22], that affirms that the reason for this might be the low number of female directors in Indian boards.

Furthermore, director independence contributes to greater transparency and accountability in the disclosure in Integrated Reporting [47] and there is evidence that adoption and conformity is linked to [21,22,48,49]. This relationship can be justified by the fact that board independence involves the responsibility of balancing the information provided. Such independence minimizes noise and enhances investments, primarily through the disclosure of reliable data and IR compliance [9,50]. In other words, board diversity and independence are factors associated with IR conformity [45,51].

However, studies indicate the absence of a clear association between integrated report conformity and financial performance and leverage. This analysis considers the basic principles of IR, which focus on how entities create value over time. In this regard, it is possible to explain the lack of relationship between Integrated Reporting compliance and financial performance through the time horizon in which the benefits manifest, being more likely in the long term rather than immediate in the short term [46,52].

The financial capacity of a company represents its ability to generate cash flows from its operating activities and is associated with the availability of financial resources to invest in strategic disclosure of information. This also means that the company can support proprietary costs of high-quality sustainability information needed by its stakeholders [53,54]. Companies with higher financial capacity tend to present higher levels of external assurance statements, as well as sustainability and integrated disclosures [55,56]. Thereby, this financial autonomy can be considered a relevant factor in influencing the extent, scope, and compliance of disclosures [57].

Profitability is considered a potential determinant of IR, as more profitable companies might have capital to invest in both integrated reporting and intellectual capital, which can generate higher quality information [58,59]. Indirectly, companies that are more profitable can allocate resources to various social and environmental sectors, which may lead them to intensify the disclosure of such investments for legitimization purposes [33]. Profitability emerges as an indicator that fosters value creation for shareholders, aligning with the objectives of Integrated Reporting. Thus, entities tend to voluntarily increase their level of disclosure and, consequently, differentiate themselves from their competitors through increased IR conformity [60].

Corporate governance mechanisms, such as the size and independence of the board of directors and the independence of the risk management committee, positively influence the quality of Integrated Reporting, while other characteristics, such as those related to the audit committee, may limit these practices. Furthermore, Integrated Reporting plays a crucial role in advancing the SDGs by embedding sustainability into corporate strategy through integrated thinking and the consideration of multiple capitals, reinforcing the importance of effective governance in enhancing the depth of disclosures and strengthening long-term value creation [61].

The introduction of the 17 SDGs by the United Nations (UN) in 2015 established a global roadmap for sustainable development, prompting corporations to align their operations and strategies with these objectives. However, the practical implementation of SDG reporting has encountered significant challenges. Empirical research indicates a frequently superficial level of engagement, characterized by the ‘cherry-picking’ of SDGs that conveniently align with pre-existing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) practices, rather than reflecting a genuine commitment. This approach can culminate in ‘SDG-washing,’ a practice wherein companies leverage the SDGs as a marketing tool without fundamentally embedding sustainability into their core operations [62]. In this context, Integrated Reporting (IR), advanced by the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), is identified as a potential “missing link” to foster more significant corporate engagement with the SDGs. The primary purpose of an integrated report is to explain to providers of financial capital how an organization creates, preserves, or erodes value over time. This type of report also benefits all stakeholders interested in a company’s capacity to create value. It seeks to promote a more cohesive and efficient approach to corporate reporting, communicating the full range of factors that materially affect an organization’s ability to create value [63]. By embedding sustainable development considerations into corporate strategy and governance, the IR supports integrated thinking and long-term value creation [1].

Ownership is a relevant issue regarding integrated reporting [16]. Under Agency Theory, there is a positive relationship between IR quality and government ownership [11]: when the Government is the major shareholder, it tends to efficiently monitor the company, which leads to a better performance through the enforcement of policies and initiatives, which may induce agency costs reduction [64]. That is, information asymmetry intensifies conflicts between managers and shareholders, and this can be mitigated through proper and high-quality reporting [11].

Legitimacy theory also may be used to explain greater environmental reporting by state-owned corporations, as political support tends to raise accountability pressure, leading companies into disclosing more information [65].

Therefore, one may expect Brazilian state-owned companies’ IR to have high-level conformity for the following reasons: (i) greater monitoring and information asymmetry reduction, given the role of the Government as a significant shareholder; (ii) public-sector accountability pressure inducing the company to produce IR as a mean to uphold its legitimacy before stakeholders and external audit institutions, such as TCU.

Considering this, we elaborate the following hypothesis:

H1.

In the context of IR, mandatory reporting is related with a higher level of conformity than voluntary reporting.

The evaluation of this hypothesis may offer valuable insight, as it investigates a context of coexistence between mandatory and voluntary regimes in a country. In addition, IR conformity is a complex, multidimensional problem that encompasses, but is not limited to, conforming to a framework. Yet, the discussion on the role of mandatory preparation of this report is scarce and should be addressed to provide evidence on the usefulness of an attempt to enforce companies to disclose it.

3. Sample and Methods

The scope of the analysis consists of companies with shares traded on the Brazilian stock market, Brasil, Bolsa, Balcão ([B]3), as of 31 December 2021, and Brazilian state-owned companies (state and federal). Municipal state-owned companies were excluded due to the unavailability of information on the quantity of these companies and the absence of data regarding their distinct financing reality compared to state and federal enterprises.

The list of state-owned companies was verified in the official data provided by the [66,67]; totaling, in 2021, 465 companies. Among these, we excluded: financial companies; companies that were privatized or undergoing privatization processes, due to significant changes in control; and subsidiaries, which often did not provide sufficient individualized data due to the process of consolidating information with the controlling entity. Regarding state-owned companies, all data were collected from the institutional websites and transparency portals of their respective controllers.

In relation to the private sector, there were 344 companies with available data in the Refinitiv Eikon database; among these, financial institutions and those that were also state-owned were excluded. Integrated reports and the age of the organizations were obtained from the institutional websites of the companies and the database of the Securities and Exchange Commission. Financial information was collected from the Refinitiv Eikon database, and board characteristics were extracted from the Formulário de Referência available in the Comissão de Valores Mobiliários (CVM) database, specifically in item 12 of the Assembleia e Administração (Subitem 12.5/6—Composição e experiência prof. da adm. e do CF).

It is important to emphasize that Integrated Reporting is a set of guidelines for the process of reporting information in an integrated manner. In that regard, reports that followed, at minimum, the structure established by the IIRC framework were included. The nomenclature of these reports has many variations, such as Integrated Reporting, Annual Management Report and Management Report. During the screening, mandatory reports under the State-Owned Companies Law, as contained in Article 8, such as the annual letter or the annual corporate governance letter, were not considered; and the Sustainability Report was used only when explicitly based on IIRC reporting parameters.

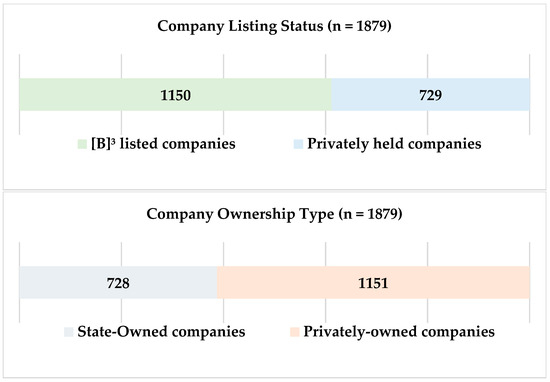

The period covered by the research was from 2018 to 2021, justified by the standardization and disclosure requirement of Integrated Reporting for state-owned companies according to Law No. 13,303/2016 (BR), which established a deadline of 24 months after its publication for the necessary adaptations for the disclosure of integrated reporting or sustainability reports. Following the data selection and cleaning procedures, the final sample comprised 1879 observations, categorized according to the distribution illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the final sample by category (n = 1879).

Model

Our dependent and explanatory variables are presented in Table 1. The dependent variable used to assess the level of conformity with the IR Framework was based on Frias- [10]. Conformity was verified using a 31-item checklist (available in Appendix A) and determined through a content analysis of the integrated reports disclosed by the companies over the years covered in the panel, assessing whether each item in the checklist was met in the IR. The scoring followed a dichotomous criterion, assigning a value of 1 (one) when the information was disclosed and 0 (zero) otherwise. Thus, for company i in period t, the total score was calculated as , where if item j was disclosed and 0 otherwise. The maximum possible score was 31 points. Finally, the conformity index with the IR Framework (CONF) for each entity was computed as , producing a normalized indicator of the level of adherence to the framework.

Table 1.

Explanatory Variables.

Since the aim is to investigate the relevance of firm characteristics for the level of conformity in disclosing the integrated report in Brazil, we opted to perform ordinary least squares regressions for unbalanced panel data, and we used the Hausman test to decide between fixed and random effects. The general model is presented in Equation (1), with variables defined in Table 1, and it was applied to different samples. It is a panel data model for companies i in time t.

Regressions 1 to 3 includes only companies that disclosed the integrated report, while Regressions 4 to 6 includes all companies in our sample. Regressions 1 and 4 include all companies, regardless of ownership; Regressions 2 and 5 include only non-state-owned companies, and Regressions 3 and 6 include only SOC. This is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Model Summary.

As we are interested in the conformity level, our main objective is to understand the reports, which leads to the first set (Regressions 1 to 3) being the most important for our analysis. Even so, there is a complimentary effect to be found in the second set, as we may learn from the comparison with companies who are not reporting it.

4. Results and Discussion

The descriptive statistics are presented in Table 3. From Panel A, it can be inferred that the sample covers a wide range of governance, financial and organizational situations, given the large standard deviations and intervals. In Panel B, it is shown that there is a low proportion of listed companies that have integrated reports, when compared to state-owned companies. Mean conformity of published reports is 29 percentage points higher for companies listed on [B]3.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics.

Table 4 presents the correlation matrix of the quantitative variables used in the analysis. The highest correlation coefficient among the variables is below 0.7, which rules out severe multicollinearity.

Table 4.

Correlation Matrix.

It is noteworthy the positive association between the size of the state-owned company and its degree of conformity with the International Integrated Reporting Council guidelines, which suggest that these entities are able to develop more comprehensive reports. This relationship, albeit with less intensity, also exists in the context of private companies with voluntary disclosure.

Regression Analysis

The econometric results are presented in Table 5. The first point of interest is that although there is no strong correlation between the variables, there seems to be a compensatory relationship between age and firm size, which encompasses all estimated models: when one is positive and significant, the other tends not to be, and in all cases at least one of the two is. The possible caveat lies in the first regression, where both are statistically significant. However, it can be observed that AGE does not acquire economic magnitude, considering the distribution of the possible values it can take, as presented in the descriptive statistics (Table 3). This phenomenon is being interpreted as a complementarity between the company’s size and its organizational maturity.

Table 5.

Regression Results.

In the first set of regressions (Reg. 1 to 3), the results for public and state-owned companies suggest, respectively, that conformity levels are positively associated with Company Size and Firm Age. That is, larger public companies (Reg. 2) can deal with higher costs to produce the report, resulting in more comprehensive documents. For state-owned companies (Reg. 3), organizational maturity plays a key role in the development of the report, as the results suggest that older firms have been able to produce reports with better conformity levels. Both the size of the company and its age contribute to strengthening the level of conformity, although the economic magnitude of age is considerably small, given its estimated coefficient and its possible values.

Moreover, when we compare both segments (Reg. 1), we find that state-owned companies have been performing worse: the average conformity achieved by state-owned companies is lower than the average achieved by listed companies, which is in line with the descriptive statistics presented in Table 3. This is consistent with the notion that companies voluntarily producing integrated reports tend to exercise greater care with them. Therefore, our results posit that the hypothesis (H1) that mandatory reporting is associated with a higher level of conformity than voluntary reporting cannot be accepted.

In the second set of regressions (Reg. 4 to 6), we have both firms that disclosed IR and those that did not. Regarding the individual regressions for public companies and SOCs (Models 5 and 6), the results are similar: conformity levels are positively associated with Firm Age and Board Gender Diversity, albeit the coefficients for state-owned companies are smaller in both cases. This reassures the importance of organizational maturity and governance for the implementation and quality of the integrated reporting. Also, it highlights that board diversity acts as a proxy for different views in the board. This is coherent with the results for the whole set of companies (Reg. 4), as they state that Company Size, Board Size, and Board Gender Diversity are positively associated with the conformity level.

Governance does not stand out among peers: board independence is not significant in any estimation; and Board size has a mixed result, as it is positive and significant in both regressions 1 and 4, while not significant in all other specifications. This suggests that among peers there is no linear relation between board size and conformity, but it is likely that boards have been contributing more to IR quality in some companies; that is, boards seem to have similar efficacies between peer companies but different behaviors between listed companies and SOC. Finally, as previously pointed out, board diversity is strongly associated with the company having the integrated report rather than how adherent this report is to the IIRC framework.

The main difference, in reference to the first set, is SOC, as it became positive, and this is due to the sample difference between the sets: Brazilian state-owned companies must publish the IR—even if some are late adopters—and therefore they have a higher proportion of non-zero conformity-level observations. This is also coherent with the descriptive statistics (Table 3, Panel B).

The estimated regression models helped identify the main factors associated with conformity, namely, company size, age, board size, and board diversity. We highlight that previous evidence presented by [51] for non-financial European companies also indicated a positive relationship, although we did not find a significant relationship for board independence. This is particularly interesting, as besides using a different geographical context, ref. [51] also measured quality in another period (2010–2019) and with another metric—the ASSET4 Datastream’s CGVS. Our results are also consistent with [68], who use a similar scoring system as its dependent variable to evaluate the impact of board characteristics on the IR quality of firms from 26 countries. They also found positive and significant regression coefficients for board characteristics, and firm size, but not for firm age. Again, a relevant difference is the role of board independence. Neither of these studies have analyzed the relationship between voluntary and mandatory disclosure.

Ref. [11] have used as a dependent variable a similar scoring system, and as main independent variables family ownership, government ownership, and foreign ownership to understand the relationship in Malaysian companies, in a similar period (2017–2020), although the sample was comprised only by publicly listed firms. They found a positive and significant coefficient for government ownership, which is in opposition to our results. It is not a contradiction per se, not only as different governments may have different policies regarding the management of the companies, but Malaysian government-linked companies are not required to publish an IR. Therefore, this difference may be due to voluntary disclosure behavior. In effect, Brazilian companies who voluntarily publish the IR also perform better than Brazilian state-owned companies.

Another remarkable result is that the only significant financial measure was total assets, indicating that, on average, it is not the most profitable companies or those with lower debt costs that are producing more comprehensive reports. This is in line with the idea that companies with more financial resources can better afford the expenses required for producing this information.

This is a particularly relevant finding for SOCs, given that these reports are required, and better reporting is being attributed to older organizations, which accumulate experience and organizational maturity. This is in line with the notion that although for these entities the publication was a legal requirement, many of them were already obliged, by previous legal norms, to disclose some related information, such as sustainability reports. It is therefore inferred that the expertise acquired previously with similar information translates into greater ease in the present production of Integrated Reporting.

5. Conclusions

Our study compared the conformity of IR towards the IIRC framework for companies who produce it voluntarily and those who were enforced to, under the hypothesis that the latter would achieve higher levels. From a sample of 165 SOC, 54 did not publish the IR (32.73%); and from our sample of 283 listed companies, only 70 had their integrated reports publicly disclosed (24.73%), which forms an initial evidence that the imposition is not yet ensuring publication, whereas making it optional is followed by a low adhesion.

It was found that the mean conformity for Brazilian state-owned firms was around 50%. This reveals that, on average, they do not adhere firmly to the integrated reporting principles, performing worse than listed companies in the [B]3 in this type of disclosure, as these firms achieved mean conformity around 80%. From a legitimacy perspective, since state-owned entities are funded by the population—a natural stakeholder of these entities—a superior outcome was expected. From this point of view of listed companies, their adhesion might be due to a belief in its relevance or pressure by stakeholders; ultimately it is a corporate decision signaling a commitment towards a cause, which is achieved through better compliance towards the framework. In addition, it seems costly and has been more effective in larger companies.

Our results are of particular interest to regulatory agencies intending to enforce integrated reporting on the markets under their supervision: the enforcement of mandatory disclosure is followed by low to medium quality reporting; that is, enforcement alone does not ensure the achievement of the goal proposed by the policy. For instance, in the Brazilian context, the CVM has established a mandatory regime for public companies, effective from 2026 onward. Given that our results did not support the hypothesis that mandatory disclosure would be positive for higher conformity, we point out that there is a possibility that a significant part of the new reports may not have an adequate conformity level.

In social contributions, we highlight the role of diversity in the board of directors as an indispensable aspect of corporate governance. Particularly noteworthy is the responsibility of women as fundamental within organizations, enhancing the likelihood of IR disclosure. Finally, considering the broader sustainable development agenda, the findings of this study reinforce the potential role of Integrated Reporting in supporting meaningful progress toward the SDGs. By highlighting the gaps in conformity, especially among state-owned enterprises subject to mandatory disclosure, this research draws attention to institutional weaknesses that hinder SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions), particularly in transparency and accountability. The relevance of board diversity aligns with SDG 5 (Gender Equality), confirming the value of inclusive governance in strengthening sustainability disclosures. Moreover, the uneven quality of reporting despite regulatory mandates suggests that the credibility of corporate contributions to SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) remains fragile. As IR practices mature and become more embedded in organizational culture—especially when backed by stronger governance and accumulated experience—corporate reporting can evolve into a reliable mechanism to support and communicate progress on sustainable development objectives.

Regarding the study’s limitations, the difficulty related to the availability and quality of data, both financial and non-financial, particularly in the context of Brazilian state-owned companies, stands out. This data scarcity had a direct impact on sample selection, leading to the exclusion of several enterprises from the research scope. Such deficiency in disclosure is accompanied by a relatively low conformity with the framework proposed by the International Integrated Reporting Council.

Further research should emphasize report readability, assessing another dimension of report quality, and contribute to the understanding of its drivers. Moreover, it may be useful to explore patterns associated with the several capitals described in the IIRC framework, which has the potential to help understand whether some aspects are neglected. Finally, it may be helpful to investigate whether late adopters have an initial conformity similar to the average conformity of the year, which may be an interesting proxy for the learning curve of this report.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P.d.O., A.B., R.M.d.F.N. and P.S.; data curation, S.P.d.O., A.B. and R.M.d.F.N.; validation, S.P.d.O., A.B., R.M.d.F.N. and P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P.d.O., A.B. and R.M.d.F.N.; writing—review and editing, S.P.d.O., A.B., R.M.d.F.N. and P.S.; supervision, P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study were manually collected from publicly available financial statements disclosed on the websites of the companies and the Brazilian Securities and Exchange Commission (CVM). A compiled dataset is not publicly archived but is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| [B]3 | Brasil, Bolsa, Balcão (Brazilian stock Exchange) |

| BR | Brazil |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| CVM | Comissão de Valores Mobiliários |

| IR | Integrated Reporting |

| IIRC | International Integrated Reporting Council |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SOC | State-owned companies |

| TCU | Tribunal de Contas da União (Federal Court of Accounts) |

Appendix A

The checklist below is largely based on [10], which primarily draws inspiration from the IIRC Framework. There are small differences in how some items were described and separated to improve the scoring process. One example is that 10 grouped all characteristics of Economic Efficiency in a single item, which has been segregated into three items in this study. After gathering the reports, they were read, and when the item (as listed below) was found, it was scored as 1.0. No weighing system was used; therefore, any company could receive a score ranging from 0 (none of the items were found) and 31 (all items were found).

Table A1.

Checklist based on the IIRC Framework.

Table A1.

Checklist based on the IIRC Framework.

| Category | Item | Indicator Description | Related SDGs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business and organization model | 01 | Corporate goals | SDGs 8, 9, 12 |

| 02 | Markets, activities, products, and services | SDGs 8, 9, 12 | |

| 03 | Key factors (intellectual capital, environmental impact, etc.) and key stakeholders | SDGs 13, 17 | |

| 04 | Attitude towards risk | SDG 16 | |

| Context, risk and opportunities | 05 | Commercial, social, environmental, and regulatory context | SDGs 13, 16 |

| 06 | Significant relationships with internal and external stakeholders (needs and expectations) | SDG 17 | |

| 07 | Main risks and opportunities | SDGs 7, 8, 11, 12, 13 | |

| Strategic goals and strategies | 08 | Key quantitative performance and risk indicators (KPI and KRI) | All SDGs |

| 09 | Corporate vision | All SDGs | |

| 10 | Risk management concerning key resources and their main relations | SDG 6, 7, 14, 15 | |

| 11 | Definition/identification of strategic goals | All SDGs | |

| 12 | Relating strategy to other elements | SDG 17 | |

| 13 | Differentiation and competitive advantage strategies | SDGs 9, 12 | |

| Corporate governance and remuneration policy | 14 | Description of corporate governance | SDG 16 |

| 15 | Influence of corporate governance on strategic decisions | SDG 16, 5, 10 | |

| 16 | Influence of corporate governance on executive compensation | SDGs 5, 10, 16 | |

| Behavior, performance, and value creation: financial, social, and environmental | 17 | Financial and non-financial results | All SDGs |

| 18 | Comparison of current results with past data | All SDGs | |

| 19 | Comparison of results with data and future estimates | All SDGs | |

| 20 | Relationship between KPI and strategic objectives | All SDGs | |

| Future outlook | 21 | Definition/identification of future challenges and opportunities (scenarios) | SDG 13 |

| 22 | Reference to the balance of short-, medium-, and long-term interests/goals | All SDGs | |

| 23 | Reference to future results and expectations | All SDGs | |

| Description of quantitative key performance indicators of performance and risk | Economic efficiency | SDGs 1, 8, 10 | |

| 24 | Added value, debt, economic contribution to the community, benefits and employees | SDG 8 | |

| 25 | Financial expenses, public administration expenses, profit, and revenue | SDGs 8, 12 | |

| 26 | Suppliers and shareholder compensation | SDGs 6, 7, 12 | |

| Environmental Efficiency | SDG 3, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 | ||

| 27 | Energy efficiency (energy and water consumption) | SDGs 11, 12 | |

| 28 | Pollution reduction (pollution emissions) | SDG 3, 4, 5, 8, 10 | |

| 29 | Waste reduction (waste generation and waste processed) | SDGs 8, 12, 16 | |

| Social Efficiency | SDGs 8, 9, 12 | ||

| 30 | Increase in human capital (absenteeism, workplace accidents and illnesses, employees, turnover, employee training, gender diversity, job stability, seniority) | SDGs 8, 9, 12 | |

| 31 | Increase in social capital (CSR-certified suppliers, local suppliers, non-compliance with legal regulation concerning customers, payment terms for suppliers) | SDGs 13, 17 |

References

- Adams, C.A. The Sustainable Development Goals, Integrated Thinking and the Integrated Report. International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC). 2017. Available online: https://www.integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/SDGs-and-the-integrated-report_full17.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Songini, L.; Pistoni, A.; Bavagnoli, F.; Minutiello, V. Integrated Reporting Quality: An Analysis of Key Determinants. In Non-Financial Disclosure and Integrated Reporting: Practices and Critical Issues; Studies in Managerial and Financial Accounting; Songini, L., Pistoni, A., Baret, P., Kunc, M.H., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2020; Volume 34, pp. 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Serafeim, G. Corporate and Integrated Reporting: A Functional Perspective. In Corporate Stewardship: Achieving Sustainable Effectiveness; Mohrman, S.A., O’Toole, J., Lawler, E.E., III, Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pistoni, A.; Songini, L.; Bavagnoli, F. Integrated Reporting Quality: An Empirical Analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, D.I.; Mazzioni, S.; Moura, G.D.; Oro, I.M. Fatores determinantes da conformidade dos relatórios integrados em relação às diretrizes divulgadas pelo International Integrated Reporting Council. Rev. Gestão Soc. Ambient. 2019, 13, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utami, E.R.; Atika, A.; Murti, C.D.; Widiastuti, H.; Rahmawati, E.; Kresnawati, E. Linking integrated or sustainability reporting to SDGs: A systematic literature review. J. Financ. Rep. Account. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, S.; Lai, F.W.; Shad, M.K.; Khatib, S.F.; Ali, S.E.A. Assessing the implementation of sustainable development goals: Does integrated reporting matter? Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2023, 14, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TCU. Tribunal de Contas da União. Decisão Normativa TCU n° 170/2018. 2018. Available online: https://portal.tcu.gov.br/data/files/FC/67/B0/53/1B199610DCEE6196F18818A8/DECISAO%20NORMATIVA-TCU%20N%20170_%20DE%2019%20DE%20SETEMBRO%20DE%202018.%20_2_.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Baboukardos, D.; Rimmel, G. Value relevance of accounting information under an integrated reporting approach: A research note. J. Account. Public Policy 2016, 35, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias-Aceituno, J.V.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L.; Garcia-Sánchez, I.M. Is integrated reporting determined by a country’s legal system? An exploratory study. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 44, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayad, A.A.; Ariff, A.H.B.M.; Ooi, S.C.; Aljadba, A.H.; Albitar, K. Ownership structure and integrated reporting quality: Empirical evidence from an emerging market. J. Financial Rep. Account. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songini, L.; Pistoni, A.; Tettamanzi, P.; Fratini, F.; Minutiello, V. Integrated reporting quality and BoD characteristics: An empirical analysis. J. Manag. Gov. 2021, 26, 579–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitolla, F.; Raimo, N.; Rubino, M.; Garzoni, A. The impact of national culture on integrated reporting quality. A stakeholder theory approach. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 1558–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Toit, E. The readability of integrated reports. Meditari Account. Res. 2017, 25, 629–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng, V.A.; Ahmed, K.; Cahan, S.F. Integrated Reporting and Agency Costs: International Evidence from Voluntary Adopters. Eur. Account. Rev. 2020, 30, 645–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, V.D.; Dumitru, M. Does corporate governance improve integrated reporting quality? A meta-analytical investigation. Meditari Account. Res. 2023, 31, 1846–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, E.K.; Jamal, J.; Puspitasari, E.; Gunardi, A. Factors influencing integrated reporting practices among Malaysian public listed real property companies: A sustainable development effort. Int. J. Manag. Financ. Account. 2018, 10, 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, M.; Kuzey, C. Assessing current company reports according to the IIRC integrated reporting framework. Meditari Account. Res. 2018, 26, 305–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias-Aceituno, J.V.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L.; Garcia-Sánchez, I.M. Explanatory factors of integrated sustainability and financial reporting. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2014, 23, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-García, L.; Zorio-Grima, A.; García-Benau, M.A. Stakeholder engagement, corporate social responsibility and integrated reporting: An exploratory study. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erin, O.; Adegboye, A. Do corporate attributes impact integrated reporting quality? An empirical evidence. J. Financ. Rep. Account. 2022, 20, 416–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vig, S. Impact of board characteristics and environmental commitment on adoption of voluntary integrated reporting: Evidence from India. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2378913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.; Melloni, G.; Stacchezzini, R. Integrated reporting and narrative accountability: The role of preparers. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 1381–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.E.; Cahan, S.; Chen, L.; Venter, E.R. The economic consequences associated with integrated report quality: Capital market and real effects. Account. Organ. Soc. 2017, 62, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, C.; Hsiao, P.-C.K.; Maroun, W. Developing a conceptual model of influences around integrated reporting, new insights and directions for future research. Meditari Account. Res. 2017, 25, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfiero, S.; Cane, M.; Doronzo, R.; Esposito, A. Board configuration and IR adoption. Empirical evidence from European companies. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2017, 15, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji, A.A. The role of audit committee attributes in intellectual capital disclosures: Evidence from Malaysia. Manag. Audit. J. 2015, 30, 756–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melloni, G.; Caglio, A.; Perego, P. Saying more with less? Disclosure conciseness, completeness and balance in Integrated Reports. J. Account. Public Policy 2017, 36, 220–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolo, G.; Zanellato, G.; Manes-Rossi, F.; Tiron-Tudor, A. Corporate reporting metamorphosis: Empirical findings from state-owned enterprises. Public Money Manag. 2021, 41, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes-Rossi, F.; Nicolò, G.; Tudor, A.T.; Zanellato, G. Drivers of integrated reporting by state-owned enterprises in Europe: A longitudinal analysis. Meditari Account. Res. 2020, 29, 586–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimo, N.; Vitolla, F.; Marrone, A.; Rubino, M. Factors affecting human capital disclosure in an integrated reporting perspective. Meas. Bus. Excel. 2020, 24, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitolla, F.; Raimo, N.; Rubino, M.; Garzoni, A. How pressure from stakeholders affects integrated reporting quality. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1591–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursimloo, S.; Ramdhony, D.; Mooneeapen, O. Influence of board characteristics on TBL reporting. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2020, 20, 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouari, G.; Dhifi, K. The impact of board characteristics on integrated reporting: Case of European companies. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2021, 18, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.A.R.; Abdullah, N.; Jamel, N.E.S.M.; Omar, N. Board Characteristics and Risk Management and Internal Control Disclosure Level: Evidence from Malaysia. Procedia Econ. Finance 2015, 31, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iredele, O.O. Examining the association between quality of integrated reports and corporate characteristics. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimo, N.; de Nuccio, E.; Vitolla, F. Corporate governance and environmental disclosure through integrated reporting. Meas. Bus. Excel. 2022, 26, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Feijoo, B.; Romero, S.; Ruiz-Blanco, S. Women on Boards: Do They Affect Sustainability Reporting? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.; Tilt, C. Board Composition and Corporate Social Responsibility: The Role of Diversity, Gender, Strategy and Decision Making. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulouta, I. Hidden Connections: The Link Between Board Gender Diversity and Corporate Social Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 113, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, F.; Chen, S.; Jiang, W.; Liu, T.; Shi, S. Gender Diversity on Boards and Firms’ Environmental Policy. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017, 26, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupley, K.H.; Brown, D.; Marshall, R.S. Governance, media and the quality of environmental disclosure. J. Account. Public Policy 2012, 31, 610–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerwanski, J.; Kordsachia, O.; Velte, P. Determinants of materiality disclosure quality in integrated reporting: Empirical evidence from an international setting. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 750–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.B.; Barbosa, A. Factors associated with the voluntary disclosure of the integrated report in Brazil. J. Financ. Rep. Account. 2021, 20, 446–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouaibi, J.; Belhouchet, S.; Almallah, R.; Chouaibi, Y. Do board directors and good corporate governance improve integrated reporting quality? The moderating effect of CSR: An empirical analysis. EuroMed J. Bus. 2022, 17, 593–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilling, P.F.A.; Caykoylu, S. Determinants of Companies that Disclose High-Quality Integrated Reports. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasan, M.; Mio, C. Fostering Stakeholder Engagement: The Role of Materiality Disclosure in Integrated Reporting. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017, 26, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlopoulos, A.; Magnis, C.; Iatridis, G.E. Integrated reporting: Is it the last piece of the accounting disclosure puzzle? J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2017, 41, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.C.; Nguyen, P.M.H.; Tran, B.H.; Nguyen, T.T.N.; Hoang, L.T.T.; Do, T.T.H. Integrated reporting disclosure alignment levels in annual reports by listed firms in Vietnam and influencing factors. Meditari Account. Res. 2022, 30, 1543–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.E. The Future of Financial Reporting: Insights from Research. Abacus 2018, 54, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouaibi, S.; Chouaibi, Y.; Zouari, G. Board characteristics and integrated reporting quality: Evidence from ESG European companies. EuroMed J. Bus. 2022, 17, 425–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churet, C.; Eccles, R.G. Integrated Reporting, Quality of Management, and Financial Performance. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2014, 26, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzey, C.; Uyar, A. Determinants of sustainability reporting and its impact on firm value: Evidence from the emerging market of Turkey. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazalin, N.; Mahmood, M. Economic, environmental, and social performance indicators of sustainability reporting: Evidence from the Russian oil and gas industry. Energy Policy 2018, 121, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhnke, K.; Gabriel, A. Determinants of voluntary assurance on sustainability reports: An empirical analysis. J. Bus. Econ. 2013, 83, 1063–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simnett, R.; Vanstraelen, A.; Chua, W.F. Assurance on Sustainability Reports: An International Comparison. Acc. Rev. 2009, 84, 937–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledoux, M.J.; Cormier, D.; Houle, S. Customer value disclosure and analyst forecasts: The influence of environmental dynamism. Manag. Decis. 2014, 52, 460–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L.; Frías-Aceituno, J.-V. The cultural system and integrated reporting. Int. Bus. Rev. 2013, 22, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniora, J. Is Integrated Reporting Really the Superior Mechanism for the Integration of Ethics into the Core Business Model? An Empirical Analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 755–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimo, N.; Vitolla, F.; Marrone, A.; Rubino, M. Do audit committee attributes influence integrated reporting quality? An agency theory viewpoint. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.M.A. The relationship between corporate governance mechanisms and integrated reporting practices and their impact on sustainable development goals: Evidence from South Africa. Meditari Account. Res. 2023, 31, 1919–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbieta, L. Firms reporting of sustainable development goals (SDGs): An empirical study of best-in-class companies. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 5005–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trucco, S.; Demartini, M.C.; Beretta, V. The reporting of sustainable development goals: Is the integrated approach the missing link? SN Bus. Econ. 2021, 1, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, H.; Musallam, S.R. Corporate ownership and company performance: A study of Malaysian listed companies. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 11, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D.; Gordon, I.M. An examination of social and environmental reporting strategies. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2001, 14, 587–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesouro Nacional. Raio-x das Empresas dos Estados Brasileiros em 2021. 2021. Available online: https://tesouro.github.io/empresas-estados/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Ministério da Economia. Boletim das Empresas Estatais Federais. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.br/gestao/pt-br/central-de-conteudo/publicacoes/boletins/boletim-das-empresas-estatais-federais (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Vitolla, F.; Raimo, N.; Rubino, M. Board characteristics and integrated reporting quality: An agency theory perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1152–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitendag, N.; Fortuin, G.S.; De Laan, A. Firm characteristics and excellence in integrated reporting. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2017, 20, a1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).