Impact of Financial Performance and Corporate Governance on ESG Disclosure: Evidence from Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To examine the impact of ROA on ESG disclosure in Saudi non-financial companies.

- To investigate the influence of board size on ESG disclosure in Saudi non-financial companies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Rise of ESG Disclosure and Its Importance in Emerging Markets

2.2. Relationship Between Financial Performance, Corporate Governance, and ESG Disclosure

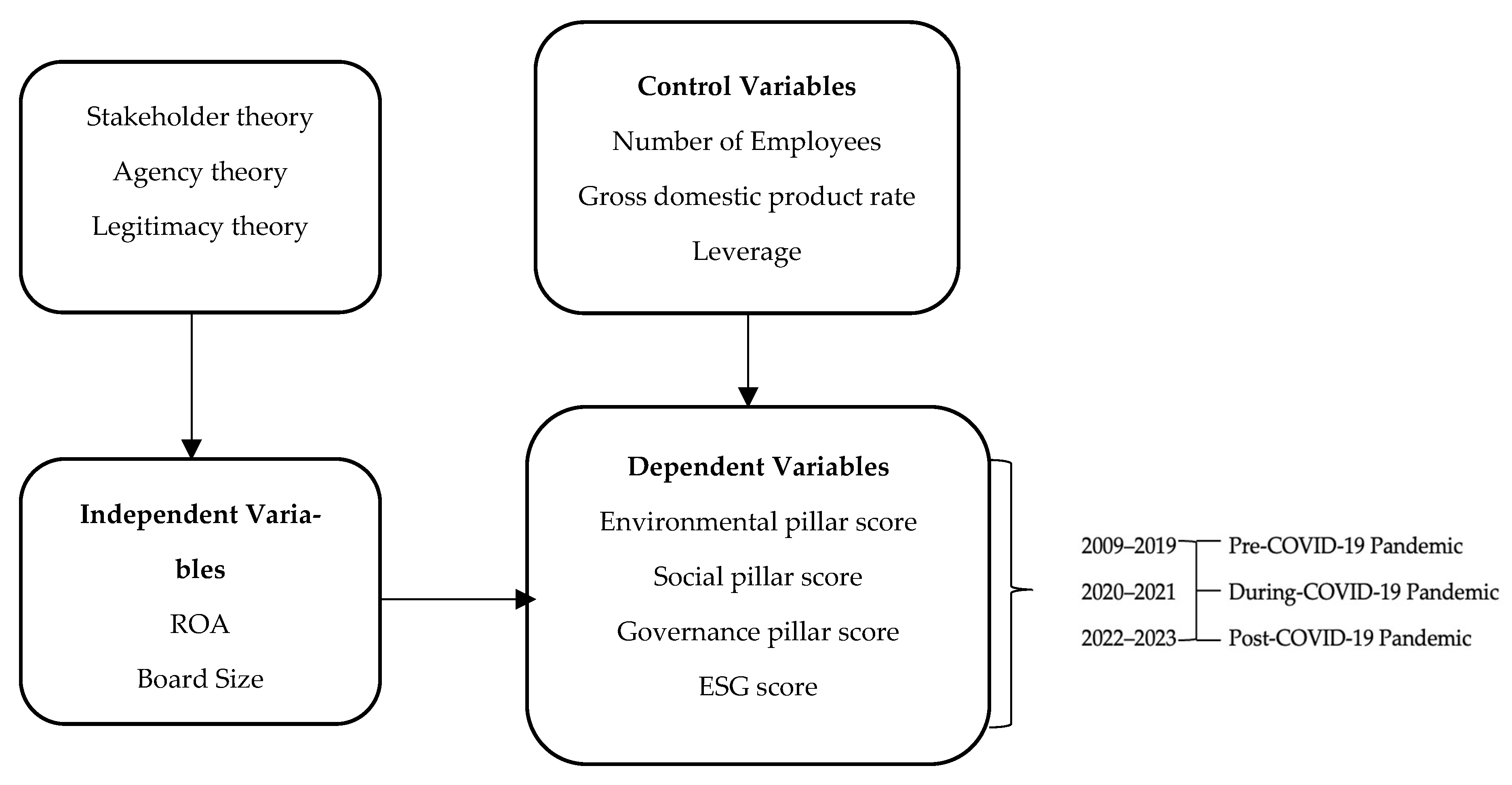

2.3. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses Development

2.3.1. ROA and ESG Disclosure

2.3.2. Board Size and ESG Disclosure

3. Research Methodology

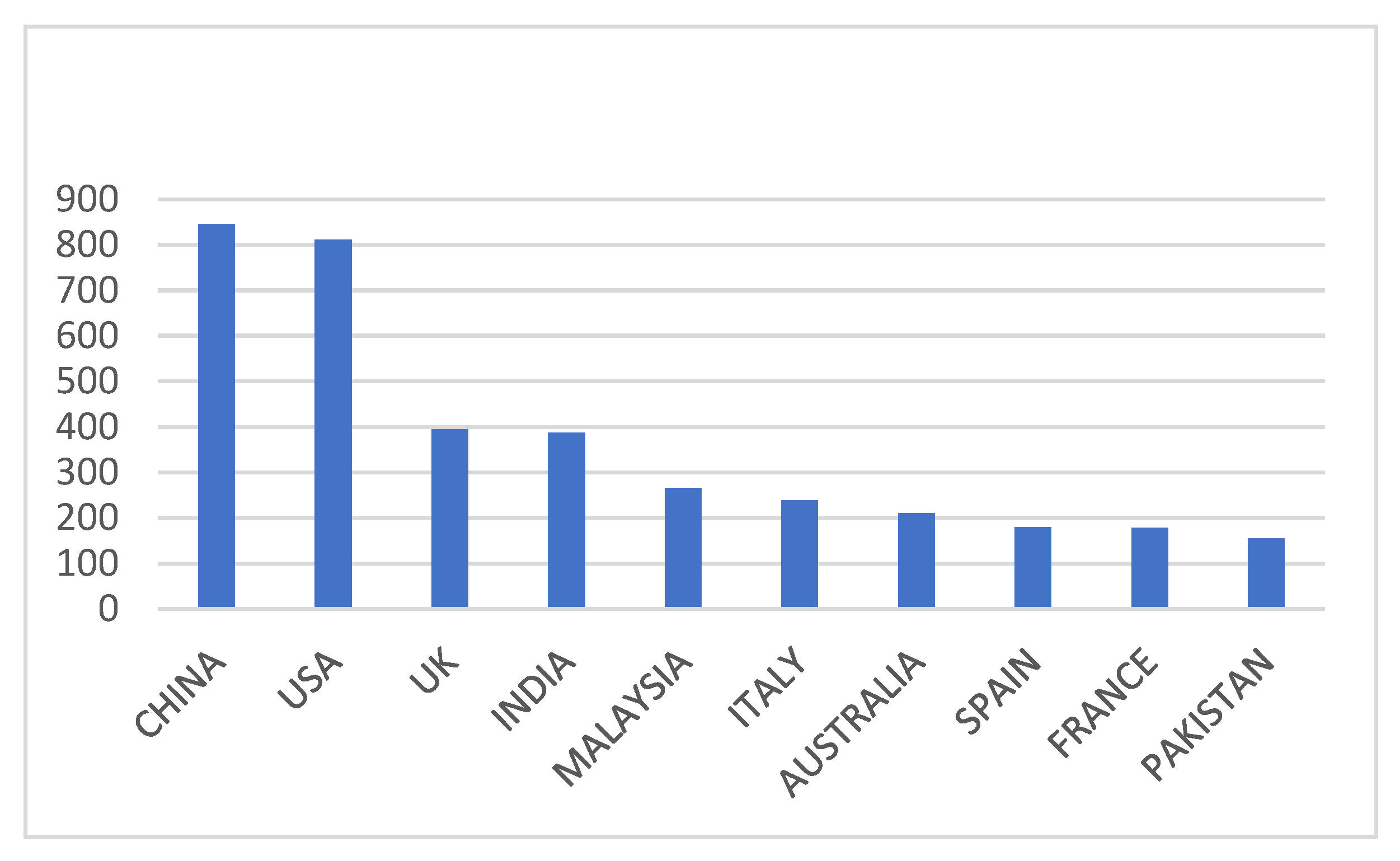

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measurement of Variables

3.3. Regression Model

4. Empirical Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

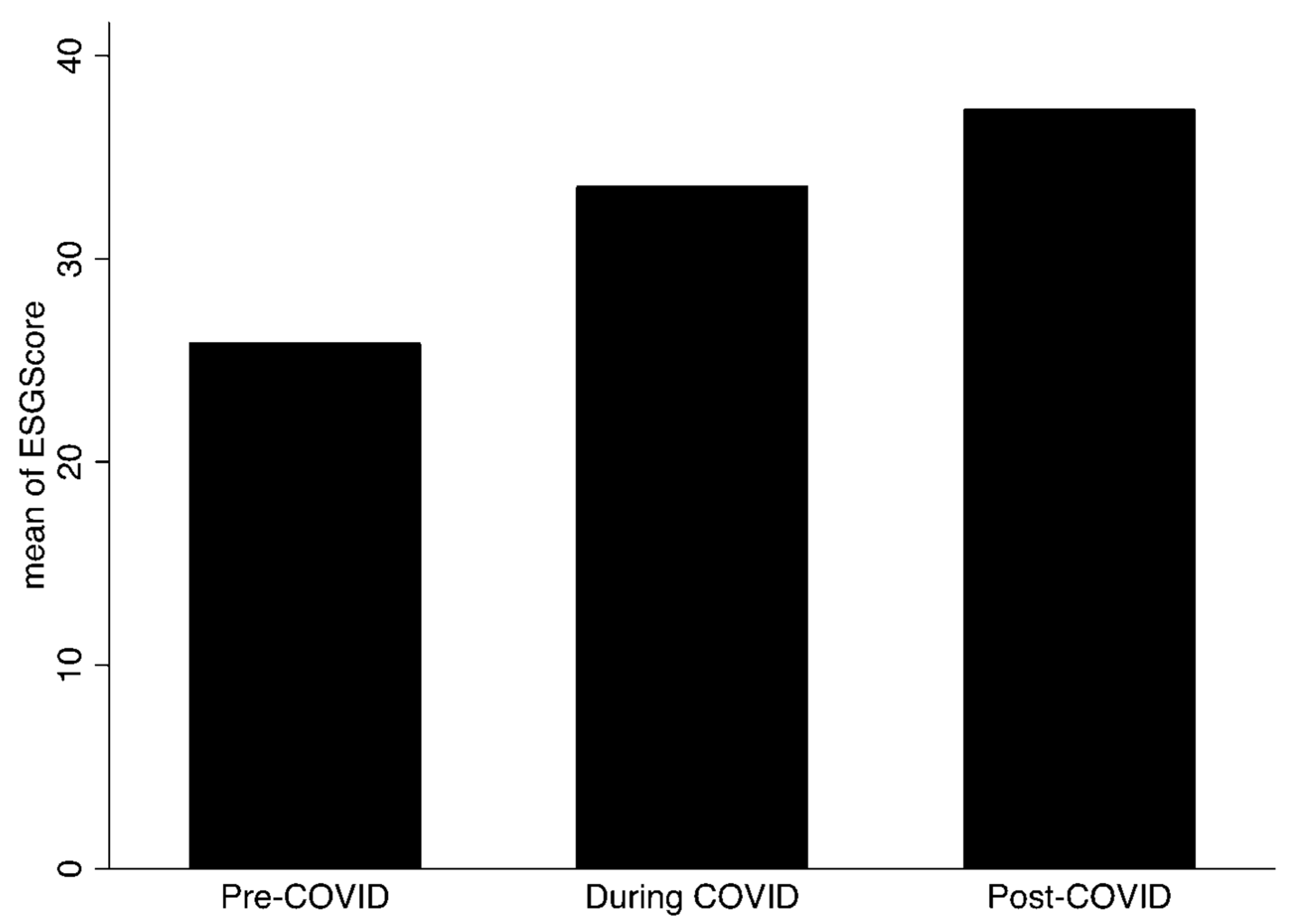

4.2. ESG Trends Across COVID-19 Periods

4.3. Correlation and Multicollinearity Analysis

4.4. Regression Analysis

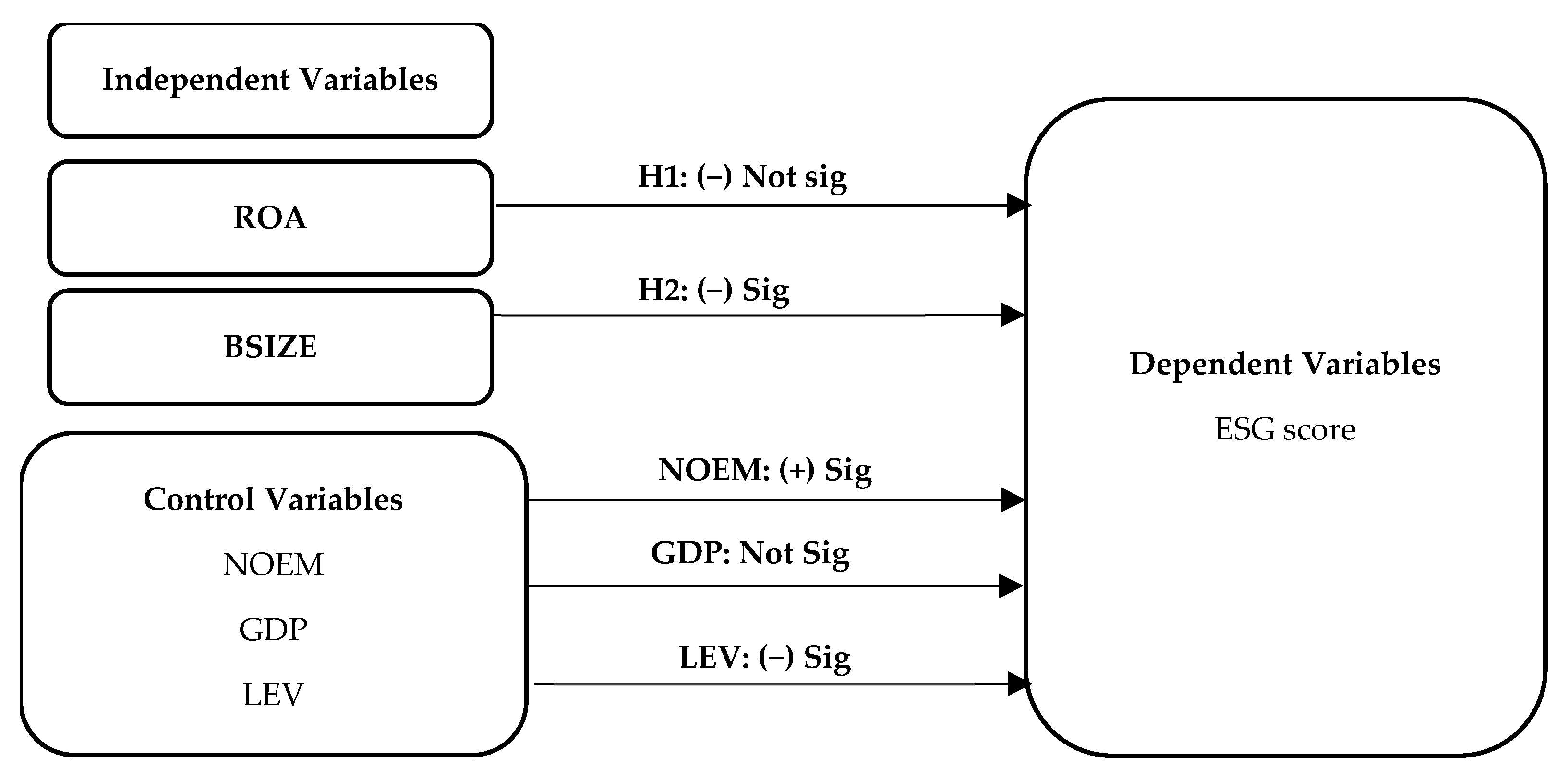

4.4.1. The Effect of Financial Performance on ESG Score

4.4.2. The Effect of Financial Performance and Board Size on ESG Score

4.5. Robustness Check

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Empirical Contributions

5.3. Policy Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BSIZE | Board Size |

| ENV | Environmental pillar |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| FE | Fixed Effects |

| GCC | Gulf Cooperation Council Countries |

| GMM | Generalized Method of Moments |

| GDP | Gross domestic product rate |

| GOV | Governance pillar |

| LEV | Leverage |

| MENA | Middle East and North Africa |

| NOEM | Number of Employees |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| ROA | Return on Assets |

| SOC | Social pillar |

| Tadawul | Saudi stock exchange |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

References

- Nuhu, Y.; Alam, A. Board Characteristics and ESG Disclosure in Energy Industry: Evidence from Emerging Economies. J. Financ. Report. Account. 2024, 22, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almubarak, W.I.; Ammer, M.A.; Chebbi, K.; Almubarak, A.I. ESG and Financial Sustainability: The Role of Saudi Corporate Governance Reforms. Cap. Mark. Auth. 2023. Available online: https://cma.gov.sa/en/ResearchAndReports/Documents/ESG-TheRoleofSaudiCorporateGovernanceReforms.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Winston, N. Sustainable Community Development: Integrating Social and Environmental Sustainability for Sustainable Housing and Communities. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.A.; Alsayegh, M.F.; Boshnak, H.A. The Impact of Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosure on the Performance of Saudi Arabian Companies: Evidence from the Top 100 Non-Financial Companies Listed on Tadawul. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, U.H.; Firmansyah, E.A.; Danlami, M.R.; Al-Faryan, M.A.S. Revisiting the Relationship between Corporate Governance Mechanisms and ESG Disclosures in Saudi Arabia. J. Account. Organ. Change 2024, 20, 724–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Vision 2030. Available online: https://vision2030.gov.sa/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Tadawul ESG Guidelines. Available online: https://www.saudiexchange.sa/wps/portal/saudiexchange/listing/issuer-guides/esg-guidelines (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Chebbi, K.; Ammer, M.A. Board Composition and ESG Disclosure in Saudi Arabia: The Moderating Role of Corporate Governance Reformsc. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezuidenhout, H.; Mhonyera, G.; Van Rensburg, J.; Sheng, H.H.; Carrera, J.M.; Cui, X. Emerging Market Global Players: The Case of Brazil, China and South Africa. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khoury, R.; Nasrallah, N.; Alareeni, B. The Determinants of ESG in the Banking Sector of MENA Region: A Trend or Necessity? Compet. Rev. 2023, 33, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalhoob, H.; Hussainey, K. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Disclosure and the Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) Sustainability Performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albitar, K.; Nasrallah, N.; Hussainey, K.; Wang, Y. Eco-Innovation and Corporate Waste Management: The Moderating Role of ESG Performance. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2024, 63, 781–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, A.S.; Elmarzouky, M. Does Capital Expenditure Matter for ESG Disclosure? A UK Perspective. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqatan, A. The Impact of Board Diversity on Earnings Management in Kuwait. J. Financ. Report. Account. 2024, 10, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treepongkaruna, S.; Kyaw, K.; Jiraporn, P. ESG Controversies and Corporate Governance: Evidence from Board Size. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2024, 33, 4218–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamahros, H.M.; Alquhaif, A.; Qasem, A.; Wan-Hussin, W.N.; Thomran, M.; Al-Duais, S.D.; Shukeri, S.N.; Khojally, H.M.A. Corporate Governance Mechanisms and ESG Reporting: Evidence from the Saudi Stock Market. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.B.; Lodha, S.; Sharma, A.; Ali, S.; Elmezughi, A.M. Environment, Social and Governance Reporting and Firm Performance: Evidence from GCC Countries. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Stud. 2022, 5, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amosh, H.; Khatib, S.F.A. ESG Performance in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Country Evidence. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 39978–39993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellili, N.O.D. Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Review of Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosure Papers: Current Topics and Recommendations for Future Research. Environ. Res. Commun. 2022, 4, 092001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siao, H.J.; Gau, S.H.; Kuo, J.H.; Li, M.G.; Sun, C.J. Bibliometric Analysis of Environmental, Social, and Governance Management Research from 2002 to 2021. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. ESG Disclosure and Firm Performance: A Bibliometric and Meta Analysis. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2022, 61, 101668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Mobarek, A.; Raid, M. Impact of Global Financial Crisis on Firm Performance in UK: Moderating Role of ESG, Corporate Governance and Firm Size. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2167548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqatan, A.; Hichri, A. CSR Practices and Earnings Management: The Mediating Effect of Accounting Conservatism and the Moderating Effect of Corporate Governance: Evidence from Finnish Companies. Compet. Rev. 2024, 35, 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnini Pulino, S.; Ciaburri, M.; Magnanelli, B.S.; Nasta, L. Does ESG Disclosure Influence Firm Performance? Sustainability 2022, 14, 7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Abeuova, D.; Alqatan, A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Institutional Investors: Evidence from Emerging Markets. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2021, 15, 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hichri, A.; Alqatan, A. Exploring Integrated Reporting’s Influence on International Firms’ Value Relevance. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, O.I.; Alsmady, A.A.; Rahman, R.A.; Alsayegh, M.F. Corporate Governance Mechanisms, Royal Family Ownership and Corporate Performance: Evidence in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Market. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Duais, S.D.; Qasem, A.; Wan-Hussin, W.N.; Bamahros, H.M.; Thomran, M.; Alquhaif, A. Ceo Characteristics, Family Ownership and Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting: The Case of Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Liu, L.; Luo, S. Sustainable Development, ESG Performance and Company Market Value: Mediating Effect of Financial Performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 3371–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O. Financial Centers and the Relationship between ESG Disclosure and Firm Performance: Evidence from an Emerging Market. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2015, 31, 1239–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygili, E.; Arslan, S.; Birkan, A.O. ESG Practices and Corporate Financial Performance: Evidence from Borsa Istanbul. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2022, 22, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birindelli, G.; Dell’Atti, S.; Iannuzzi, A.P.; Savioli, M. Composition and Activity of the Board of Directors: Impact on ESG Performance in the Banking System. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsartawi, A.M. Board Independence, Frequency of Meetings and Performance. J. Islam. Mark. 2019, 10, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buallay, A.; Fadel, S.M.; Al-Ajmi, J.Y.; Saudagaran, S. Sustainability Reporting and Performance of MENA Banks: Is There a Trade-Off? Meas. Bus. Excel. 2020, 24, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janadi, Y.; Abdul Rahman, R.; Alazzani, A. Does Government Ownership Affect Corporate Governance and Corporate Disclosure?: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Manag. Audit. J. 2016, 31, 871–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertzanis, C.; Basuony, M.A.K.; Mohamed, E.K.A. Social Institutions, Corporate Governance and Firm-Performance in the MENA Region. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2019, 48, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Stakeholder Management. A Strategic Approach; Cambridge University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M.; Meckling, W. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behaviour, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, J.; Pfeffer, J. Organizational Legitimacy: Social Values and Organizational Behavior. Pac. Sociol. Rev. 1975, 18, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Faryan, M.A.S.; Shil, N.C. Nexus between Governance and Economic Growth: Learning from Saudi Arabia. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2130157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, A.S.; Elmarzouky, M. Sustainability Reporting and Market Uncertainty: The Moderating Effect of Carbon Disclosure. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basali, M.A.; Mohammed, R.K. Leverage And Profitability Dynamics: An Empirical Study of Energy Sector Companies Listed on Tadawul in Saudi Arabia. Jazan Univ. J. Hum. Sci. 2025, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alregab, H. The Role of Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance on Attracting Foreign Ownership: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollah, S.; Zaman, M. Shari’ah Supervision, Corporate Governance and Performance: Conventional vs. Islamic Banks. J. Bank. Financ. 2015, 58, 418–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimi, A.; Rachdi, H.; Ben, R.; Mokni, S.; Hssini, H. Do Board Characteristics Affect Bank Performance? Evidence from the Bahrain Islamic Banks. J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2018, 9, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, H.; Mallin, C.; Ow-Yong, K. Corporate Governance in Islamic Banks: New Insights for Dual Board Structure and Agency Relationships. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2018, 54, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anas, M.; Gulzar, I.; Tabash, M.I.; Ahmad, G.; Yazdani, W.; Alam, M.F. Investigating the Nexus between Corporate Governance and Firm Performance in India: Evidence from COVID-19. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drempetic, S.; Klein, C.; Zwergel, B. The Influence of Firm Size on the ESG Score: Corporate Sustainability Ratings under Review. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 167, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, T.; Nur, T. The Effect of ESG Sustainability on Firm Performance: A View Under Size and Age on BIST Bank Index Firms. J. Res. Econ. Polit. Financ. 2023, 8, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nasser Mohammed, S.A.S.; Joriah Muhammed, D. Financial Crisis, Legal Origin, Economic Status and Multi-Bank Performance Indicators Evidence from Islamic Banks in Developing Countries. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2017, 18, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models; Cambridge University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tarighi, H.; Hosseiny, Z.N.; Akbari, M.; Mohammadhosseini, E. The Moderating Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Relation between Corporate Governance and Firm Performance. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2023, 16, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L. GMM and 2SLS Estimation of Mixed Regressive, Spatial Autoregressive Models. J. Econom. 2007, 137, 489–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazzani, A.; Wan-Hussin, W.N.; Jones, M.; Al-hadi, A. ESG Reporting and Analysts’ Recommendations in GCC: The Moderation Role of Royal Family Directors. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albitar, K.; Abdoush, T.; Hussainey, K. Do Corporate Governance Mechanisms and ESG Disclosure Drive CSR Narrative Tones? Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 28, 3876–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G* Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gujarati, D. Basic Econometrics; The McGraw-Hill Companies: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Badar Ul Munir, M.; Ishfaq, M. Impact of Environmental Award and Financial Performance on Environmental Disclosure Quality: A Case Study of Listed Companies in Pakistan. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.D.; Xie, Z. Transitioning to Sustainability: The Impact of ESG on Financial Performance in the Post-Soviet EU States. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2025, 15, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Label | Definition/Measurement | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | |||

| ESG score | ESG | ESG Score is an aggregate metric that assesses a company’s overall environmental, social, and governance performance. It is based on self-reported data across these three pillars. The ESG score is calculated using the data reported by the company itself on these parameters, with each pillar having specific metrics that are assessed and aggregated. The score typically ranges from 0 to 100, where a higher score represents better overall ESG performance based on the company’s disclosure, practices, and policies. It serves as a comprehensive indicator for investors and stakeholders to evaluate the company’s sustainability and ethical practices. | Thomson Reuters DataStream |

| Independent Variable | |||

| Return on assets | ROA | Indicator of how profitable a company is relative to its total assets. It is calculated by Net Income/Total Assets. | Thomson Reuters DataStream And Annual reports |

| Board size | BSIZE | Number of members on a company’s board of directors. | |

| Control Variable | |||

| Number of Employees | NOEM | Total number of employees | DataStream Worldscope |

| Gross domestic product rate | GDP | The annual percentage growth rate of GDP | World Bank Group |

| Leverage | LEV | Financial leverage, represented by the debt-to-equity ratio, shows how a firm’s capital is structured, highlighting the balance among debt and equity used for financing. | Thomson Reuters DataStream |

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | 260 | 31.14 | 20.69 | 0.73 | 82.59 |

| ROA | 260 | 7.17 | 7.26 | −4.16 | 24.83 |

| BSIZE | 260 | 9.59 | 1.89 | 7 | 14 |

| NOEM | 260 | 11,080.55 | 11,345.96 | 413 | 40,000 |

| GDP | 260 | 2.84 | 3.79 | −3.58 | 10.99 |

| LEV | 260 | 32.88 | 21.97 | 0 | 89.8 |

| Period | Mean | Std. Dev. | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-COVID | 25.88 | 17.94 | 113 |

| During COVID | 33.61 | 21.48 | 86 |

| Post-COVID | 37.39 | 22.18 | 61 |

| Total | 31.14 | 20.69 | 260 |

| Variable | ESGS | ROA | BSIZE | NOEM | GDP | LEV | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | 1.0000 | |||||||

| ROA | −0.0496 | 1.0000 | 1.16 | 0.864832 | ||||

| BSIZE | −0.0401 | 0.1021 | 1.0000 | 1.01 | 0.985895 | |||

| NOEM | 0.3360 * | −0.0420 | −0.0259 | 1.0000 | 1.03 | 0.968500 | ||

| GDP | −0.0016 | 0.1109 | 0.0125 | −0.0027 | 1.0000 | 1.01 | 0.985866 | |

| LEV | 0.1349 * | −0.3505 * | −0.0915 | 0.1756 * | −0.0779 | 1.0000 | 1.18 | 0.846873 |

| Mean VIF | 1.08 |

| OLS ESG | Robust ESG | Fixed Effects ESG | GMM ESG | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 3 | Model 3 |

| ROA | −0.141 (−0.80) | −0.024 (−0.13) | −0.141 (−0.87) | −0.024 (−0.15) | −0.261 (−1.34) | 0.001 (0.006) | ||

| BSIZE | −0.440 (−0.64) | −0.266 (−0.41) | −0.440 (−0.68) | −0.266 (−0.43) | −1.009 ** (−2.06) | −0.302 ** (0.129) | ||

| NOEM | 0.001 *** (5.38) | 0.001 *** (6.00) | 0.000540 (0.88) | 0.018 (0.083) | ||||

| GDP | 0.034 (0.11) | 0.034 (0.10) | 0.0947 (0.53) | 0.009 (0.008) | ||||

| LEV | 0.069 (1.15) | 0.069 (1.16) | −0.254 *** (−2.91) | −0.006 * (0.003) | ||||

| Constant | 32.153 *** (17.81) | 35.359 *** (5.31) | 24.980 *** (3.55) | 32.153 *** (18.55) | 35.359 *** (5.53) | 24.980 *** (3.74) | 44.78 *** (5.26) | 3.728 *** (0.767) |

| Observations | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 |

| R2 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.120 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.120 | 0.066 | 0.041 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.102 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.102 | 0.197 | 0.022 |

| OLS | Robust | Fixed Effects | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | ENV | SOC | GOV | ENV | SOC | GOV | ENV | SOC | GOV |

| ROA | 0.247 (1.23) | 0.0522 (0.26) | −0.109 (−0.50) | 0.247 (1.29) | 0.0522 (0.32) | −0.109 (−0.49) | 0.0978 (0.44) | −0.386 (−1.62) | −0.502 ** (−1.97) |

| BSIZE | 0.202 (0.28) | −1.031 (−1.44) | 1.257 (1.60) | 0.202 (0.26) | −1.031 * (−1.66) | 1.257 (1.62) | 0.420 (0.76) | −0.922 (−1.54) | −1.731 *** (−2.71) |

| NOEM | 0.000887 *** (7.29) | 0.000494 *** (4.10) | 0.000309 ** (2.34) | 0.000887 *** (7.23) | 0.000494 *** (4.24) | 0.000309 ** (2.47) | 0.00117 * (1.68) | 0.000482 (0.64) | −0.000528 (−0.66) |

| GDP | −0.418 (−1.16) | 0.0615 (0.17) | 0.386 (0.98) | −0.418 (−1.14) | 0.0615 (0.16) | 0.386 (0.95) | −0.246 (−1.22) | 0.139 (0.64) | 0.382 (1.64) |

| LEV | 0.0842 (1.25) | 0.0877 (1.32) | 0.196 *** (2.69) | 0.0842 (1.14) | 0.0877 (1.37) | 0.196 *** (2.68) | −0.155 (−1.58) | −0.258 ** (−2.42) | −0.233 ** (−2.05) |

| Constant | 7.370 (0.94) | 27.83 *** (3.59) | 23.04 *** (2.71) | 7.370 (0.79) | 27.83 *** (3.94) | 23.04 *** (2.83) | 10.62 (1.10) | 41.20 *** (3.95) | 77.93 *** (7.01) |

| N | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260 |

| R2 | 0.194 | 0.086 | 0.073 | 0.194 | 0.086 | 0.073 | 0.036 | 0.047 | 0.079 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.178 | 0.068 | 0.054 | 0.178 | 0.068 | 0.054 | 0.236 | 0.221 | 0.181 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Basali, M. Impact of Financial Performance and Corporate Governance on ESG Disclosure: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8473. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188473

Basali M. Impact of Financial Performance and Corporate Governance on ESG Disclosure: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8473. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188473

Chicago/Turabian StyleBasali, Mona. 2025. "Impact of Financial Performance and Corporate Governance on ESG Disclosure: Evidence from Saudi Arabia" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8473. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188473

APA StyleBasali, M. (2025). Impact of Financial Performance and Corporate Governance on ESG Disclosure: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 17(18), 8473. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188473