Towards Corporate Sustainability: Can the Cultural and Tourism Consumption Promotion Policy Enhance Corporate ESG Performance?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. ESG Measurement and Economic and Social Impact

2.2. Research on the Effect of the CTCP Policy

2.3. DID Model Application Research

2.4. Research Gaps

3. Policy Background and Theoretical Analysis

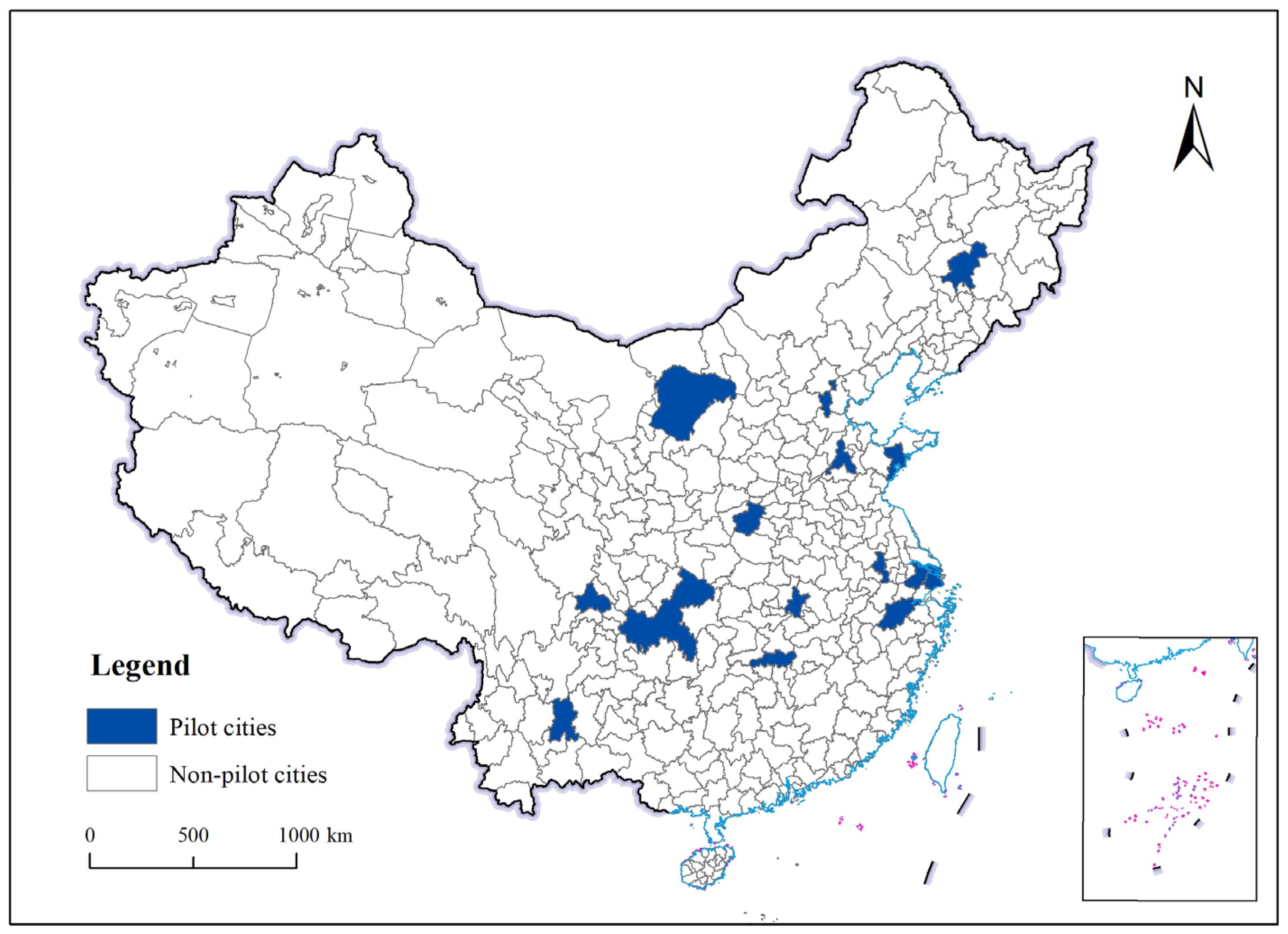

3.1. Policy Background

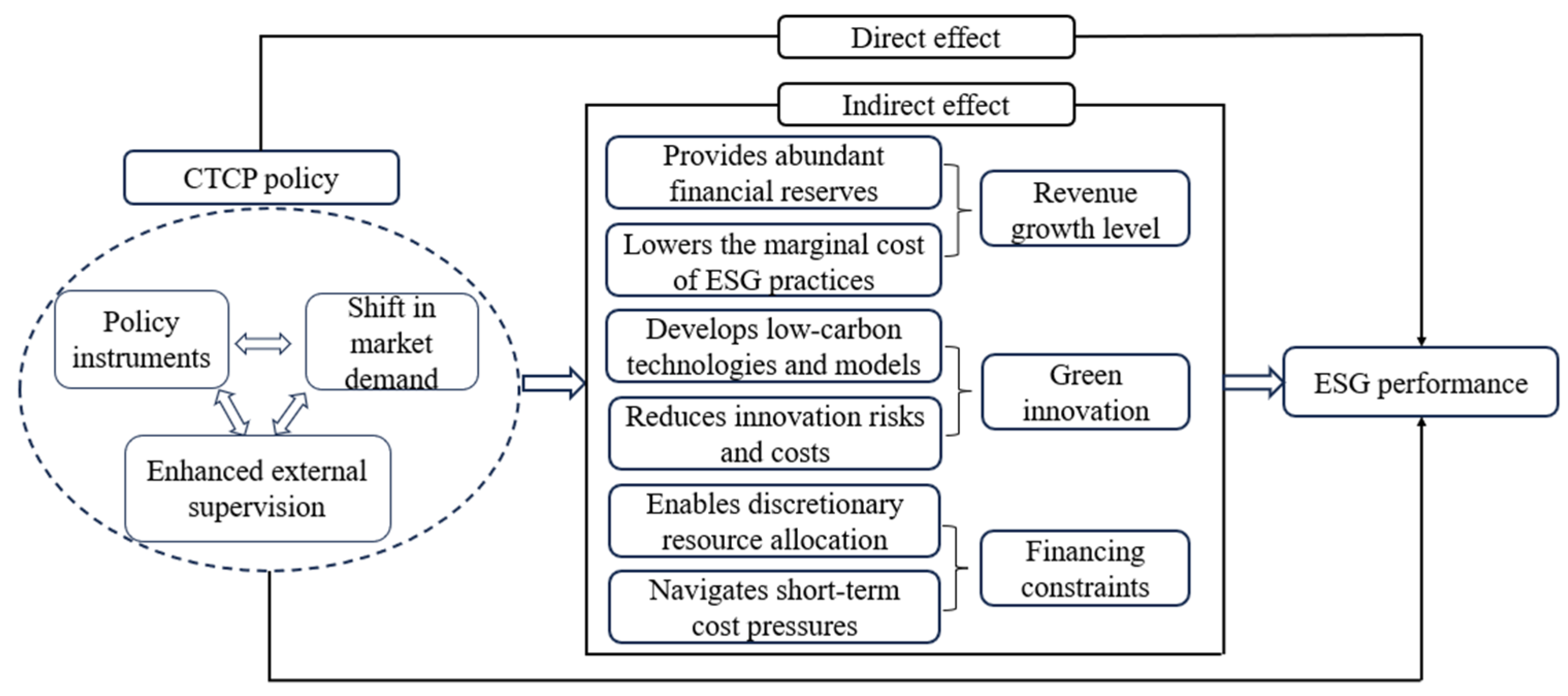

3.2. Theoretical Analysis

3.2.1. Direct Effect

3.2.2. Indirect Effect

4. Methodology

4.1. Model Setting

4.2. Variable Selection

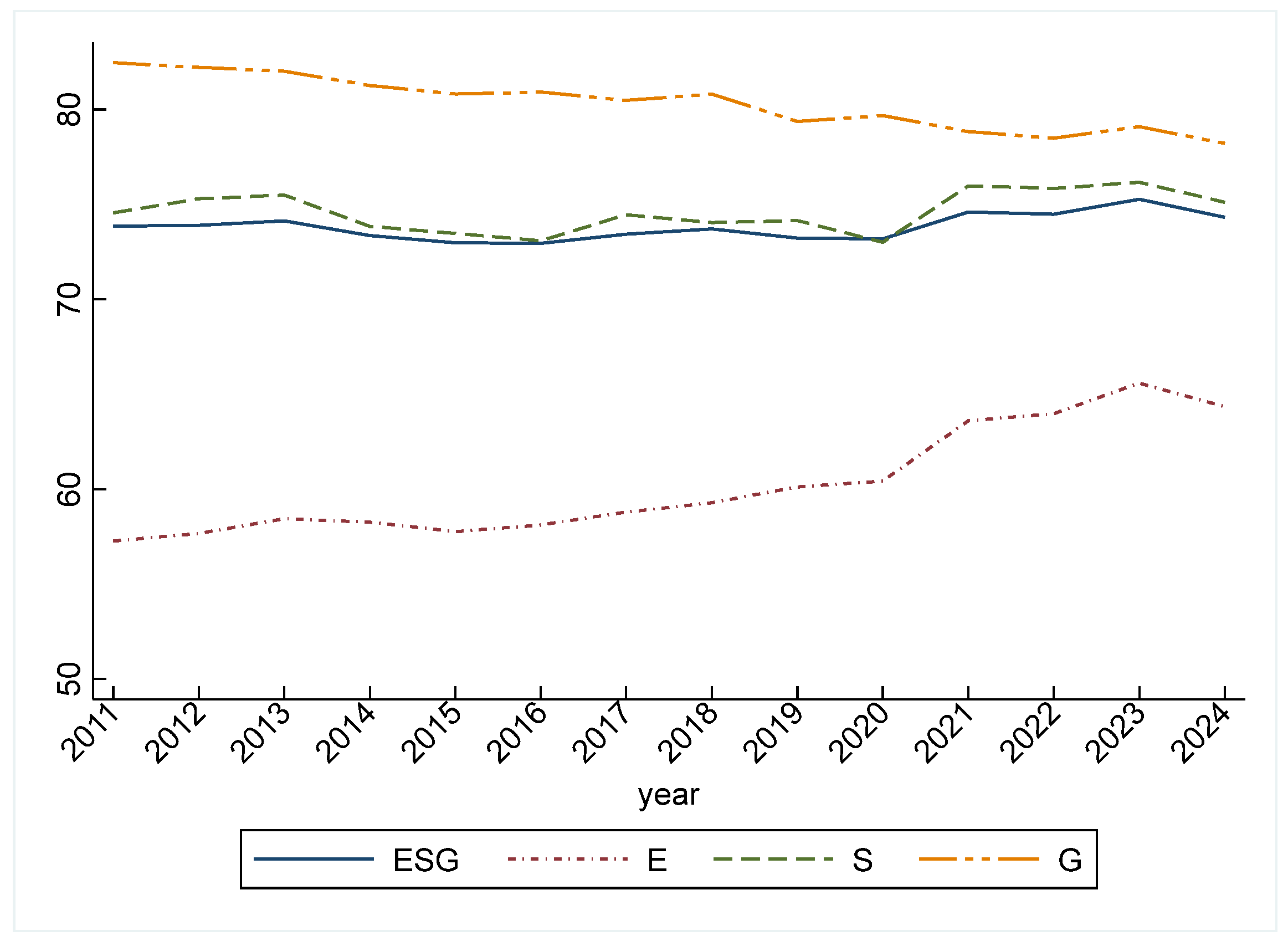

4.2.1. Explained Variable

4.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable

4.2.3. Control Variables

4.2.4. Mediating Variables

4.3. Data Description

4.4. Correlation Matrix

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Benchmark Regression

5.2. Robustness Tests

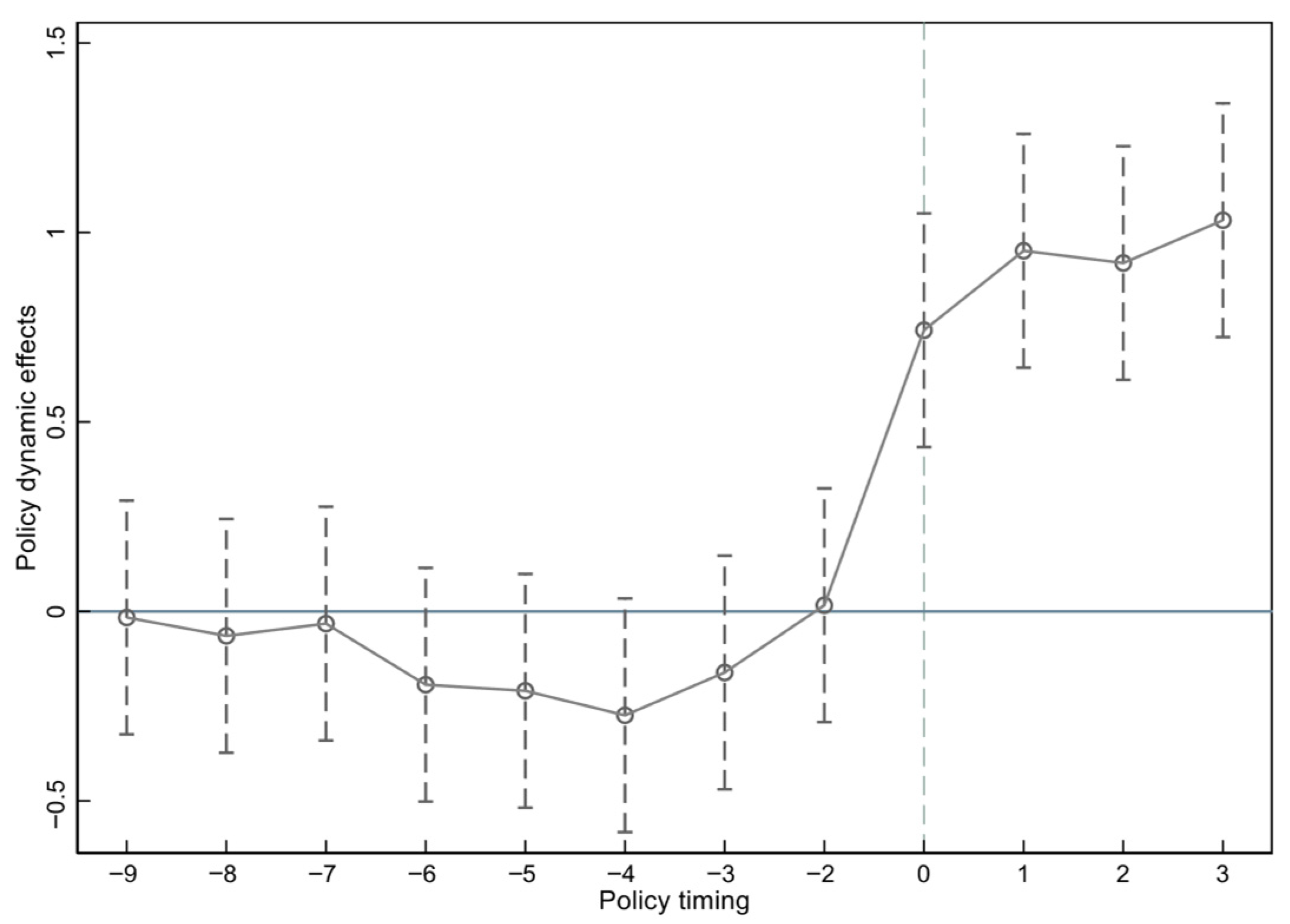

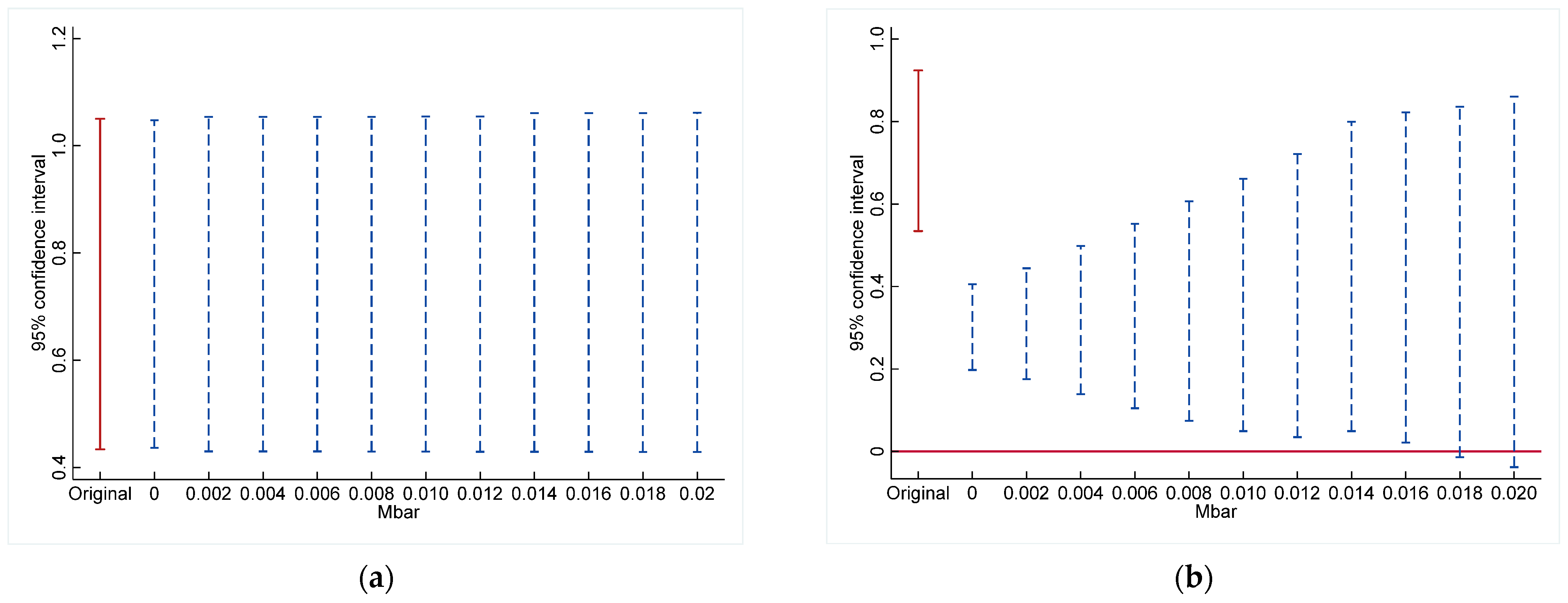

5.2.1. Parallel Trend Test

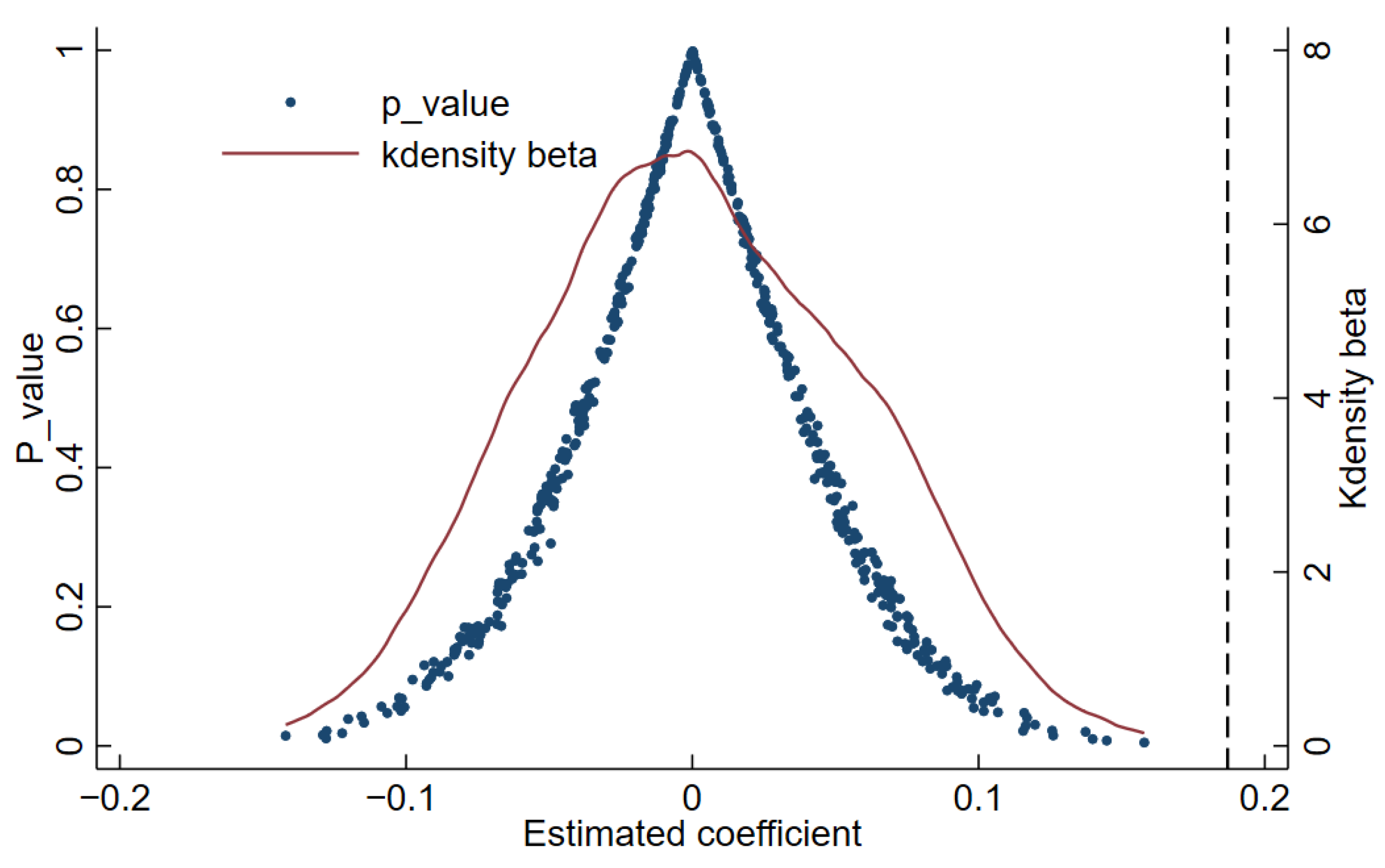

5.2.2. Placebo Test

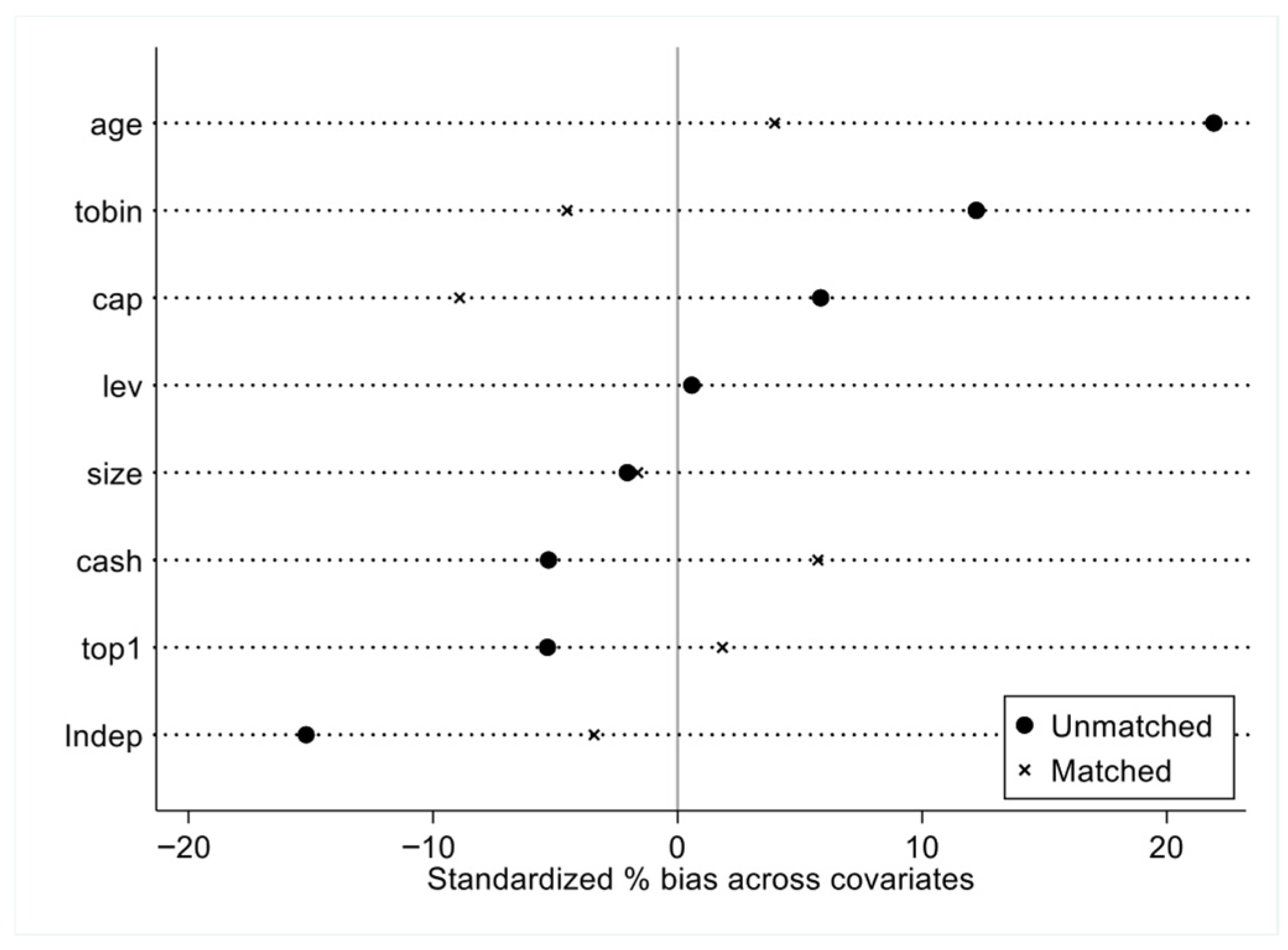

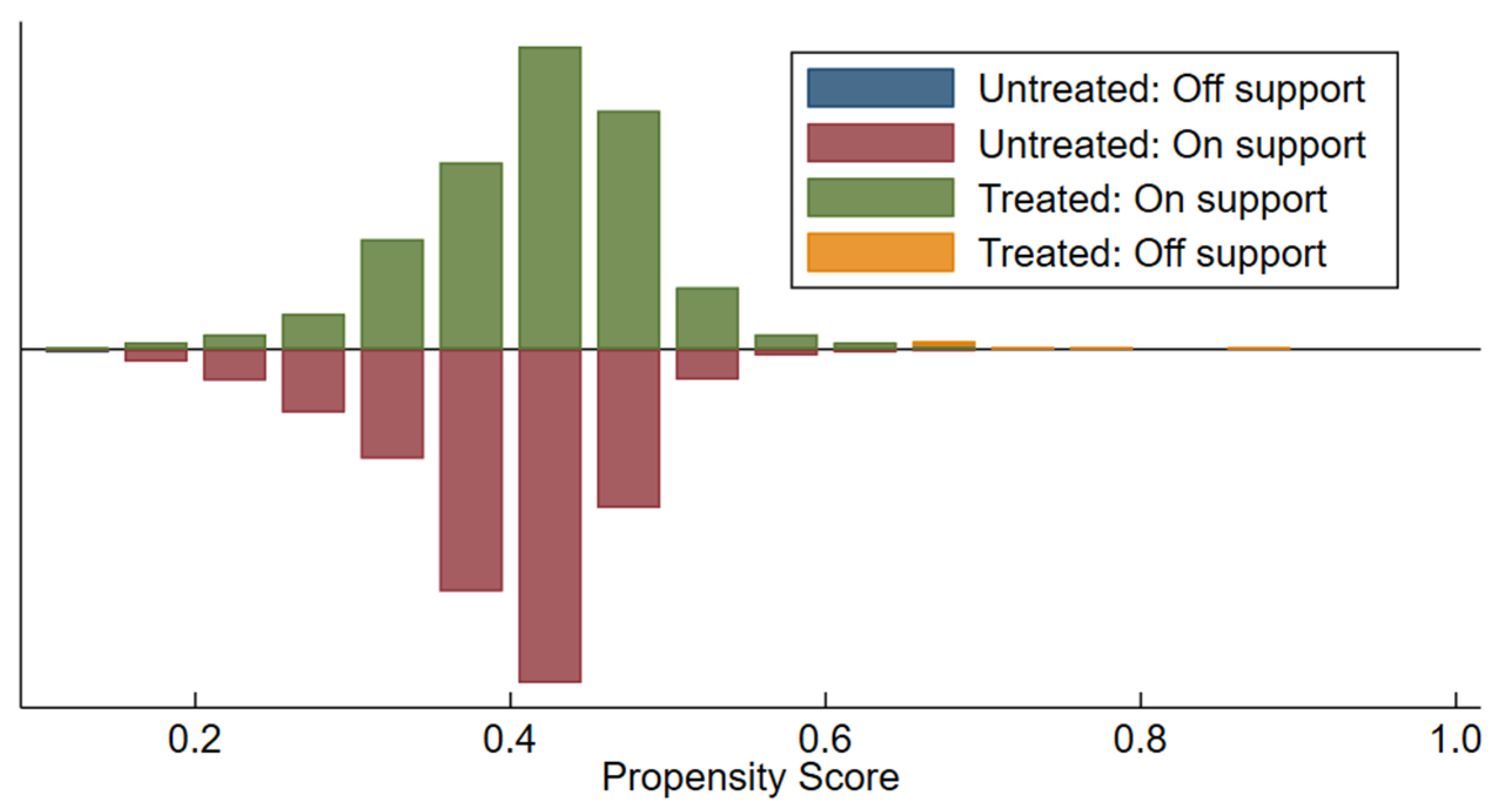

5.2.3. Endogeneity Issues

5.2.4. Other Robustness Tests

5.3. Mechanism Verification

5.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.4.1. Heterogeneity in Terms of the Nature of Property Rights

5.4.2. Heterogeneity of the Governance Structure

5.4.3. Labor-Intensive Heterogeneity

6. Further Analysis: ESG Rating Divergence and Strategic Disclosure

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESG | Environmental, Social and Governance |

| CTCP | Cultural and tourism consumption promotion |

| DID | Difference-in-differences |

| PSM | Propensity Score Matching |

References

- Niesten, E.; Jolink, A.; Bacha, E. Sustainable development in turbulent environments: The impact of ESG capabilities on responses to turbulence. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2024, 33, 6468–6490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidage, M.; Bhide, S. ESG and economic growth: Catalysts for achieving sustainable development goals in developing economies. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 2060–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.S.; Zhang, H.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) measurement in the tourism and hospitality industry: Views from a developing country. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliani, K.; Hamza, F.; Alessa, N.; Borgi, H.; Albitar, K. ESG disclosure in G7 countries: Do board cultural diversity and structure policy matter? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 3031–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah Zhu, N.; Hashmi, M.A.; Shah, M.H. CEO power, board features and ESG performance: An extensive novel moderation analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 5627–5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyhunov, A.; Kim, J.D.; Bae, S.M. The effects of board diversity on Korean Companies’ ESG performance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xing, Y.; Xiao, D. An empirical study on the relationship between executives’ financial background and corporate ESG performance. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 102, 104141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Mi, W.; Zhang, R. Provincial ESG performance in China: Evolution trends and the role of environmental regulation. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 107, 107570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Ning, M.; Chen, Q.; Shi, C.; Wang, N. How does command-and-control environmental regulation impact firm value? A study based on ESG perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 11477–11508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognesi, E.; Burchi, A.; Goodell, J.W.; Paltrinieri, A. Stakeholders and regulatory pressure on ESG disclosure. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 103, 104145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Q.; Kong, L.Y. Business environment innovation pilot and corporate ESG performance. Financ. Econ. Collect. 2025, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhou, C.; Gan, Z. Green finance policy and ESG performance: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Yu, J. Striving for sustainable development: Green financial policy, institutional investors, and corporate ESG performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 1177–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, L.; de Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests and Identities; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.F.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate confusion: The divergence of ESG ratings. Rev. Financ. 2022, 26, 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariyer, G.; Mangla, S.K.; Chowdhury, S.; Sozen, M.E.; Kazancoglu, Y. Predictive and prescriptive analytics for ESG performance evaluation: A case of fortune 500 companies. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 181, 114742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Lee, L.E.; Stroehle, J.C. The social origins of ESG: An analysis of Innovest and KLD. Org. Environ. 2020, 33, 575–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimanski, T.; Reding, A.; Reding, N.; Bingler, J.; Kraus, M.; Leippold, M. Bridging the gap in ESG measurement: Using NLP to quantify environmental, social, and governance communication. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 61, 104979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, R.; Koskinen, Y.; Zhang, C. Corporate social responsibility and firm risk: Theory and empirical evidence. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 4451–4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Lee, W. ESG and financial performance of China firms: The mediating role of export share and moderating role of carbon intensity. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornuf, L.; Yüksel, G. The performance of socially responsible investments: A meta-analysis. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2024, 30, 1012–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jiao, S.; Ma, C. The impact of ESG responsibility performance on corporate resilience. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 93, 1115–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.K.; Zhang, Q.M. Understanding the mechanism of environmental, social, and governance impact on enterprise performance in the context of sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 784–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnaoui, A. ESG ratings and investment performance: Evidence from tech-heavy mutual funds. Rev. Account. Financ. 2025, 24, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahat, B.; Nguyen, P. Does ESG performance impact credit portfolios? Evidence from lending to mineral resource firms in emerging markets. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 104052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Chen, H.; Tang, H.; Chen, M. Can the Chinese cultural consumption pilot policy facilitate sustainable development in the agritourism economy? Agriculture 2025, 15, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.Y.; Liu, X.Z. The impact and mechanism of cultural and tourism consumption promotion policy under the background of the integration of culture and tourism: Empirical evidence from pilot demonstration cities. J. East China Norm. Univ. 2025, 57, 162–175+180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.J.; Guo, Y.Z. Multiple paths of urban tourism policy change: A clear set qualitative comparative (csQCA) analysis based on Suzhou. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 41, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, F. Resource constraints, differentiation of government roles and policy implementation by local governments: A case study based on public culture service demonstration areas. Manag. World 2023, 39, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.S.; Chen, K.X.; Li, Y.T. Can institutional innovation promote digital industry innovation: Evidence from pilot free trade zones. Int. Econ. Trade Res. 2025, 41, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.T.; Wang, D. Targeted sustainable development policy and corporate green innovation: An analysis on the first batch of national sustainable development agenda innovation demonstration zones. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2025, 47, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Jin, S.Y. What drives sustainable development of enterprises? Focusing on ESG management and green technology innovation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, W.; Shen, H. The dynamic effect of environmental regulation on firms’ energy consumption behavior—Evidence from China’s industrial firms. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 156, 111966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.X.; Liu, C.Y.; Zhou, Q.; Jin, Y.L.; Gong, F.Y. Will the innovation of local industrial chain policy achieve a win-win situation of “economy-environment”? A quasi-natural experiment based on the “industrial chain leader institution”. J. Financ. Econ. 2024, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbard, S.; Etheridge, J.C.; Murray, E.J. A tutorial on applying the difference-in-differences method to health data. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2024, 11, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtmann, M.; Rjosk, C.; Jansen, M.; Lüdtke, O. The double-edged sword of de-tracking reforms in germany: Using a difference-in-differences approach to estimate effects on students’ educational aspirations and their association with students’ socioeconomic backgrounds. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2024, 81, 101350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shen, H.; Li, Y.; Yin, T. Impact of industrial symbiotic agglomeration on energy efficiency: Analysis using time-varying difference-in-difference model. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Wang, Y.; Jing, L. Low-carbon city pilot, external governance, and green innovation. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 67, 105768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, G.; Zhang, W.; Li, C. How does low-carbon city pilot policy catalyze companies toward ESG practices? Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 81, 1593–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H. Investigating the nexus between environmental information disclosure and green development efficiency: The intermediary role of green technology innovation: A PSM-DID analysis. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 11653–11683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Z.C.; Tao, C.Q. Can innovative pilot city policies improve the allocation level of innovation factors? Evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 200, 123135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Han, Y.; Jiao, H.; Feng, Y. Re-evaluating the effectiveness of regional energy saving targets: Empirical evidence from the Eleventh Five-year plan in China. Energy 2025, 318, 134769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.C.; Larcker, D.F.; Wang, C.C. How much should we trust staggered difference-in-differences estimates? J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 144, 370–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, P.; Tamer, E.; Tang, X. Parallel trends and dynamic choices. J. Polit. Econ. Microecon. 2024, 2, 129–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Li, S.; Choi, Y. Has the belt and road initiative enhanced economic resilience in cities along its route? Land 2025, 14, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunerhjelm, P. Rethinking stabilization policies: Including supply-side measures and entrepreneurial processes. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 963–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Tuo, S.; Lei, K.; Gao, A. Assessing quality tourism development in China: An analysis based on the degree of mismatch and its influencing factors. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 9525–9552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, S.; Dumay, J. Corporate ESG reporting quantity, quality and performance: Where to now for environmental policy and practice? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2022, 31, 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T.; Iqbal, S.; Ayub, A.; Fatima, T.; Rasool, Z. Promoting responsible sustainable consumer behavior through sustainability marketing: The boundary effects of corporate social responsibility and brand image. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, S.; Shahab, Y. State-led supply chains and ESG outcomes: Evidence from China’s industrial policy. Appl. Econ. 2025, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Lin, W.; Wang, H. ESG and customer stability: A perspective based on external and internal supervision and reputation mechanisms. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Liu, G. Global perspectives on environmental policy innovations: Driving green tourism and consumer behavior in circular economy. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 374, 124138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Chen, Z. Can government subsidies promote the green technology innovation transformation? Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 74, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Liu, D.; Huang, F. Synergistic effect of government policy and market mechanism on the innovation of new energy vehicle enterprises. Energy 2024, 295, 130998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Deng, X.; Wang, D.; Pan, X. Financial regulation, financing constraints, and enterprise innovation performance. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 95, 103387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algeri, C.; Brighi, P.; Venturelli, V. Integrating ESG factors into cost-efficiency frontier: Evidence from the European listed banks. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2025, 34, 3242–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Branstetter, L.G. Does “Made in China 2025” work for China? Evidence from Chinese listed firms. Res. Policy 2024, 53, 105009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D.; Guedhami, O.; Li, K.; Lu, G. National culture and the value implications of corporate environmental and social performance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 71, 102123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Bao, K.; Hu, X.; Gao, C.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, T. Climate-Resilient City Construction and Firms’ ESG Performance: Mechanism Analysis and Empirical Tests. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Z. Does ESG rating disagreement affect management tone manipulation? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 101, 104039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Deng, H.; Gao, X. Corporate coupling coordination between ESG and financial performance: Evidence from China’s listed companies. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 107, 107546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, C. Regional digitalization and corporate ESG performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 473, 143503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, N.; Su, W.; Zhou, H. Green innovation and corporate ESG performance: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 95, 103461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Tan, H.; Ling, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B.; Tu, Y. Impact of environmental information uncertainty and market competition on corporate ESG performance. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 99, 103935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.M.; Zhu, Q.W. How can green innovation solve the dilemmas of “harmonious coexistence”? Manag. World 2021, 37, 128–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; He, R. The impact of carbon emissions trading policy on the ESG performance of heavy-polluting enterprises: The mediating role of green technological innovation and financing constraints. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Mardani, A. Digital finance and enterprise financing constraints: Structural characteristics and mechanism identification. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 165, 114074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhao, M.F.; Hu, Y.; Wang, L.J. Study on the impact of culture and tourism integration on the ESG performance of tourism listed enterprises. Tour. Sci. 2025, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Yang, O.; Xia, D.; Liu, H. Substantive or symbolic? The strategic choice of sustainable environmental strategy for enterprises induced by the new environmental protection law. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 7461–7481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, J.; Sant’Anna, P.H.; Bilinski, A.; Poe, J. What’s trending in difference-in-differences? A synthesis of the recent econometrics literature. J. Econom. 2023, 235, 2218–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambachan, A.; Roth, J. A more credible approach to parallel trends. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2023, 90, 2555–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zhu, Y. Does AI elevate corporate ESG performance? A supply chain perspective. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2025, 34, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Ghimire, A.; Long, X.; Chen, L. Will more multinational corporations inflow approach closer toward carbon neutrality? Novel propensity score matching-difference-in-difference evidence across 35 developing countries. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2025, 34, 1625–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Jiao, S.T. Cracking the innovation dilemma with culture: The case of museums. Rev. Ind. Econ. 2025, 25, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodory, H.; Huber, M.; Lafférs, L. Evaluating (weighted) dynamic treatment effects by double machine learning. Econometr. J. 2022, 25, 628–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athey, S.; Imbens, G.W. Identification and inference in nonlinear difference-in-differences models. Econometrica 2006, 74, 431–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Song, S.; Liu, C. Green signals: The impact of environmental protection support policies on firms’ green innovation. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2024, 33, 3258–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, H. Manufacturing enterprises move towards sustainable development: ESG performance, market-based environmental regulation, and green technological innovation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 372, 123244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, H.; Yang, H.; Cifuentes-Faura, J.; Rauf, A. The role of carbon trading in enhancing enterprise green productivity and ESG performance: A quasi-natural evidence from China. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2025, 34, 1691–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Wang, C.; Zhang, M. Does social media pressure induce corporate hypocrisy? Evidence of ESG greenwashing from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2025, 197, 311–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silkoset, R.; Nygaard, A. Leveraging blockchain and smart contracts to combat greenwashing in sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 5874–5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhu, H.; Meng, Y. ESG greenwashing and equity mispricing: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkaite-Vaitone, N.; Tamuliene, V. Unveiling the untapped potential of green consumption in tourism. Sustainability 2024, 16, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; Raschke, R.L.; Krishen, A.S. Signaling green! firm ESG signals in an interconnected environment that promote brand valuation. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 138, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Yang, S.; Maqsood, U.S.; Zahid, R.A. Tapping into the green potential: The power of artificial intelligence adoption in corporate green innovation drive. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2024, 33, 4375–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.L.; Chen, Z.L.; Ouyang, F. Research on the impact of enterprise digitalization on capacity utilization from the perspective of investment efficiency. Bus. Rev. 2025, 37, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keresztúri, J.L.; Berlinger, E.; Lublóy, Á. Environmental policy and stakeholder engagement: Incident-based, cross-country analysis of firm-level greenwashing practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 192–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2142 | 4.193 | 1.097 | 1.000 | 8.000 | |

| 2142 | 0.145 | 0.352 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| 2142 | 22.786 | 1.284 | 19.563 | 26.452 | |

| 2142 | 2.731 | 0.596 | 0.000 | 3.466 | |

| 2142 | 0.439 | 0.198 | 0.042 | 0.935 | |

| 2142 | 0.056 | 0.063 | −0.199 | 0.266 | |

| 2142 | 1.712 | 1.202 | 0.789 | 16.647 | |

| 2142 | 3.202 | 2.826 | 0.379 | 19.481 | |

| 2142 | 0.374 | 0.151 | 0.074 | 0.758 | |

| 2142 | 37.389 | 5.842 | 30.000 | 60.000 | |

| 2142 | 0.107 | 0.386 | −0.654 | 3.808 | |

| 2142 | 3.150 | 0.914 | 0.000 | 5.473 | |

| 2142 | −1.042 | 0.099 | −3.832 | −0.487 |

| Variables | Esg | Size | Age | Lev | Cash | Tobin | Top1 | Indep | Cap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| esg | 1 | ||||||||

| size | 0.177 | 1 | |||||||

| age | −0.080 | 0.263 | 1 | ||||||

| lev | −0.068 | 0.406 | 0.231 | 1 | |||||

| cash | 0.102 | 0.139 | −0.043 | −0.140 | 1 | ||||

| tobin | −0.059 | −0.421 | −0.150 | −0.300 | −0.001 | 1 | |||

| top1 | 0.073 | 0.173 | −0.065 | −0.124 | 0.094 | −0.098 | 1 | ||

| indep | 0.134 | 0.131 | −0.026 | 0.059 | 0.041 | 0.100 | −0.096 | 1 | |

| cap | −0.127 | 0.106 | 0.131 | −0.163 | −0.090 | −0.062 | 0.070 | −0.0240 | 1 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.136 ** | 0.187 ** | 0.212 *** | 0.181 ** | |

| (2.02) | (2.26) | (3.24) | (2.21) | |

| 0.220 *** | 0.499 *** | |||

| (9.64) | (8.19) | |||

| −0.180 *** | −0.425 *** | |||

| (−4.88) | (−3.71) | |||

| −1.081 *** | −1.422 *** | |||

| (−7.51) | (−6.10) | |||

| 0.262 | −0.033 | |||

| (0.72) | (−0.09) | |||

| −0.037 * | −0.004 | |||

| (−1.94) | (−0.18) | |||

| −0.070 *** | −0.048 *** | |||

| (−8.79) | (−3.59) | |||

| 0.116 | 0.229 | |||

| (0.73) | (0.68) | |||

| 0.021 *** | 0.016 *** | |||

| (5.51) | (3.03) | |||

| 4.174 *** | 4.166 *** | −0.432 | −5.943 *** | |

| (163.06) | (184.20) | (−0.95) | (−4.42) | |

| NO | YES | NO | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| NO | YES | NO | YES | |

| N | 2142 | 2142 | 2142 | 2142 |

| R2 | 0.0019 | 0.4372 | 0.1125 | 0.4752 |

| Variables | E | S | G |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.562 | 1.593 * | 0.046 | |

| (1.08) | (1.83) | (0.11) | |

| YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | |

| N | 2142 | 2142 | 2142 |

| R2 | 0.5940 | 0.5507 | 0.5420 |

| Variables | PSM-DID | Instrumental Variable Approach | Double Machine Learning Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| 0.175 ** | 0.898 ** | 1.225 * | 1.011 ** | |

| (2.13) | (2.14) | (1.75) | (2.46) | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| N | 2129 | 2142 | 2142 | 2142 |

| R2 | 0.4759 | 0.4520 | ||

| Variables | Replace the Dependent Variable | Adjust the Window Period | CIC Model | Exclude Interference from Other Policies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| 0.694 * | 0.176 ** | 0.163 * | 0.195 * | 0.195 ** | 0.175 ** | |

| (1.75) | (2.05) | (1.85) | (1.94) | (2.06) | (2.11) | |

| 0.031 | ||||||

| (0.40) | ||||||

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| N | 2142 | 1683 | 1530 | 2142 | 2142 | 2142 |

| R2 | 0.5036 | 0.5047 | 0.5175 | 0.4752 | ||

| Variables | Grow | Esg | Ginn | Esg | Fcon | Esg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| 0.064 ** | 0.101 * | −0.005 * | ||||

| (1.99) | (1.82) | (−2.35) | ||||

| 2.809 ** | ||||||

| (2.21) | ||||||

| 1.787 ** | ||||||

| (2.21) | ||||||

| −12.751 ** | ||||||

| (−2.37) | ||||||

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| 2142 | 2142 | 2142 | 2142 | 2142 | 2142 | |

| 0.2167 | 0.4752 | 0.6834 | 0.4752 | 0.8542 | 0.4403 |

| Variables | State-Owned | CEO Duality | Labor-Intensive | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| 0.220 ** | 0.151 | 0.307 | 0.236 ** | 0.173 * | 0.206 | |

| (2.28) | (0.98) | (1.32) | (2.55) | (1.92) | (1.09) | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| 1442 | 700 | 350 | 1769 | 1598 | 519 | |

| 0.5098 | 0.4476 | 0.5574 | 0.4934 | 0.5073 | 0.4944 | |

| Variables | ESG Rating Divergence | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All Firms | Large-Scale Firms | Small-Scale Firms | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| 0.258 ** | 0.164 | 0.582 *** | |

| (2.03) | (0.91) | (2.92) | |

| YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | |

| 989 | 489 | 490 | |

| 0.4867 | 0.5633 | 0.4947 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Bao, K.; Gao, C.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, T. Towards Corporate Sustainability: Can the Cultural and Tourism Consumption Promotion Policy Enhance Corporate ESG Performance? Sustainability 2025, 17, 8402. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188402

Chen X, Bao K, Gao C, Wen Y, Zhang T. Towards Corporate Sustainability: Can the Cultural and Tourism Consumption Promotion Policy Enhance Corporate ESG Performance? Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8402. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188402

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xiatian, Kaihua Bao, Chen Gao, Ya Wen, and Ting Zhang. 2025. "Towards Corporate Sustainability: Can the Cultural and Tourism Consumption Promotion Policy Enhance Corporate ESG Performance?" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8402. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188402

APA StyleChen, X., Bao, K., Gao, C., Wen, Y., & Zhang, T. (2025). Towards Corporate Sustainability: Can the Cultural and Tourism Consumption Promotion Policy Enhance Corporate ESG Performance? Sustainability, 17(18), 8402. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188402