From Fast Fashion to Shared Sustainability: The Role of Digital Communication and Policy in Generation Z’s Consumption Habits

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1. Which communicative elements foster positive attitudes toward sustainable fashion among Generation Z?

- RQ2. How does peer influence mediate the relationship between digital communication and sustainable consumption behaviors?

- RQ3. How do young consumers perceive the sustainability practices of well-known fashion brands, and how does this affect purchase intentions?

2. Theoretical Framework and Methodology

2.1. Sustainable Fashion and Responsible Consumption in Gen Z

2.2. Digital Communication and Social Media in the Transformation of Consumption

2.3. Peer Influence on Fashion Consumption Habits

2.4. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Sample Profile

3.2. Internal Reliability of the Scales

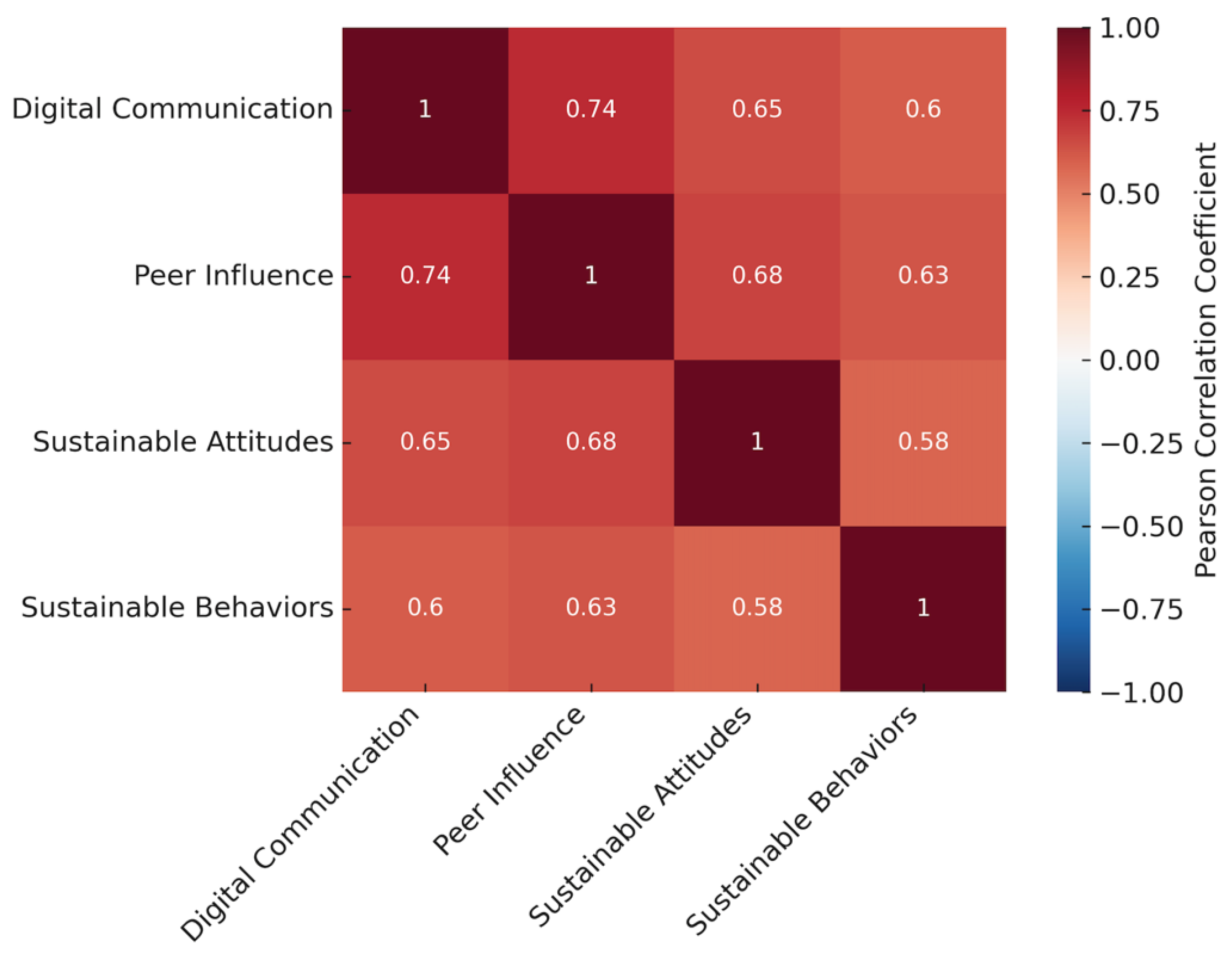

3.3. Correlation Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

- Block 2 (digital communication) and Block 3 (peer influence): r = 0.745;

- Block 3 (peer influence) and Block 1 (sustainable behaviors): r = 0.629;

- Block 2 (digital communication) and Block 1 (sustainable behaviors): r = 0.604 (p < 0.001).

3.4. Exploratory Analysis of Gender-Based Differences

3.5. Exploratory Analysis by Age Group

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bick, R.; Halsey, E.; Ekenga, C.C. The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. 2017. Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-new-textiles-economy (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Fletcher, K. Sustainable Fashion and Textiles: Design Journeys, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, A.; Sherry, J.F., Jr.; Venkatesh, A.; Wang, J.; Chan, R. Fast fashion, sustainability, and the ethical appeal of luxury brands. Fashion Theory 2012, 16, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E.; Alevizou, P.J.; Oates, C.J. What is sustainable fashion? J. Fashion Mark. Manag. 2016, 20, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L.; Moore, R. Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. State of Fashion 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/retail/our%20insights/state%20of%20fashion/2022/the-state-of-fashion-2022.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Park, H.; Kim, Y.K. An empirical test of the triple bottom line of customer-centric sustainability. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 610–618. [Google Scholar]

- Granskog, A.; Lee, L.; Magnus, K.H.; Sawers, C. The State of Fashion 2020; McKinsey & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Retail/Our%20Insights/The%20state%20of%20fashion%202020%20Navigating%20uncertainty/The-State-of-Fashion-2020-final.ashx (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Hogh, N.; Braun, J.; Watermann, L.; Kubowitsch, S. I Don’t Buy It! A Critical Review of the Research on Factors Influencing Sustainable Fashion Buying Behavior. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarik, M.S.; Naghavi, N. Digital Technologies and Consumption: How to Shape the Unknown? In The Palgrave Handbook of Corporate Sustainability in the Digital Era; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentina, E.; Tang, T.L.; Gu, Q. Does peer influence impact ethical consumption? Young Consum. 2021, 22, 429–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H. Narrativas visuales de sostenibilidad. Comunicar 2021, 29, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z. Greenwashing Versus Green Authenticity: How Green Social Media Influences Consumer Perceptions and Green Purchase Decisions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.; Plepys, A. Product-as-service in the circular economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Joy, A.; Peña, C. Sustainability and the fashion industry: Conceptualizing nature and traceability. In Sustainability in Fashion: A Cradle to Upcycle Approach; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Influencers on Instagram. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Nayak, L. Marketing Sustainable Fashion: Trends and Future Directions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brydges, T. Closing the loop on take-make-waste. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, T.; Hoefel, F. ‘True Gen’: Generation Z and Its Implications for Companies; McKinsey & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Consumer%20Packaged%20Goods/Our%20Insights/True%20Gen%20Generation%20Z%20and%20its%20implications%20for%20companies/Generation-Z-and-its-implication-for-companies.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Baena, V. The shift from fast fashion to socially and sustainable fast fashion. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 4315–4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bläse, R.; Filser, M.; Kraus, S.; Puumalainen, K.; Moog, P. Non-sustainable buying behavior. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 626–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.K.; Chang, Y.T. Exploring the key elements of sustainable design. Sustainability 2023, 15, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayaban, C.J.G.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Persada, S.F.; Borres, R.D.; Gumasing, M.J.J.; Nadlifatin, R. The influence of social media and sustainability advocacy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, P. Consumer attitude towards sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fill, C.; Turnbull, S.L. Marketing Communications: Brands, Experiences and Participation; Pearson: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, B.B.; Bakken, J.P.; Nguyen, J. Peer influence in adolescence. In The Encyclopedia of Child and Adolescent Development; Hupp, S., Jewell, J., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Workman, J.E.; Lee, S.H. Fashion consumer groups, gender, and need for uniqueness. Fashion Text. 2017, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papasolomou, I.; Melanthiou, Y.; Tsamouridis, A. The fast fashion vs environment debate: Consumers’ level of awareness, feelings, and behaviour towards sustainability within the fast-fashion sector. J. Mark. Commun. 2023, 29, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.M.; Ko, E.; Chae, H.; Mattila, P. Understanding fashion consumers’ attitude and behavioral intention toward sustainable fashion products: Focus on sustainable knowledge sources and knowledge types. J. Glob. Fashion Mark. 2016, 7, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Castillo Apraiz, J.; Cepeda Carrión, G.A.; Roldán, J.L. Manual de Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); OmniaScience: Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Thematic Block | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|

| 1: Consumer profile and current habits | 0.716 |

| 2: Influence of digital communication | 0.789 |

| 3: Influence of peers and close environment | 0.821 |

| 4: Attitudes and future disposition towards sustainability | 0.756 |

| Digital Communication | Peer Influence | Sustainable Attitudes | Sustainable Behaviors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Communication | 1.000 | 0.745 | 0.653 | 0.604 |

| Peer Influence | 0.745 | 1.000 | 0.675 | 0.629 |

| Sustainable Attitudes | 0.653 | 0.675 | 1.000 | 0.584 |

| Sustainable Behaviors | 0.604 | 0.629 | 0.584 | 1.000 |

| Gender | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Women | 3.33 | 0.99 |

| Men | 3.06 | 1.09 |

| t (gl ≈ 140)/p | 1.73 | 0.09 |

| Age Group | Mean | Standard Deviation | N (participants) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–21 | 3.02 | 0.97 | 132 |

| 22–25 | 3.71 | 1.02 | 56 |

| 26+ | 3.38 | 1.30 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Del Olmo Arriaga, J.L.; Pretel-Jiménez, M.; Ruíz-Viñals, C. From Fast Fashion to Shared Sustainability: The Role of Digital Communication and Policy in Generation Z’s Consumption Habits. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188382

Del Olmo Arriaga JL, Pretel-Jiménez M, Ruíz-Viñals C. From Fast Fashion to Shared Sustainability: The Role of Digital Communication and Policy in Generation Z’s Consumption Habits. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188382

Chicago/Turabian StyleDel Olmo Arriaga, José Luis, Marilé Pretel-Jiménez, and Carmen Ruíz-Viñals. 2025. "From Fast Fashion to Shared Sustainability: The Role of Digital Communication and Policy in Generation Z’s Consumption Habits" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188382

APA StyleDel Olmo Arriaga, J. L., Pretel-Jiménez, M., & Ruíz-Viñals, C. (2025). From Fast Fashion to Shared Sustainability: The Role of Digital Communication and Policy in Generation Z’s Consumption Habits. Sustainability, 17(18), 8382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188382