Stakeholder Perspectives on Multipurpose Shipyard Integration in Indonesia: Benefits, Challenges, and Implementation Pathways

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What are the main views of Indonesian stakeholders on multipurpose shipyards?

- RQ2: What benefits do stakeholders see from the combination of shipbuilding, repair, and recycling?

- RQ3: What challenges can stakeholders expect in the management of multipurpose shipyards?

- RQ4: How can stakeholder traits and creative dynamics influence the possible acceptance of this model?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Indonesia Shipbuilding Overview

2.1.1. Economic Significance

2.1.2. Infrastructure Challenges

2.1.3. Regulatory Environment

2.2. Shipyard Operational Model

2.2.1. Multipurpose Shipyard Concept

2.2.2. Hybrid and Integrated Approaches

2.2.3. International Examples of Shipyard Operational Models

2.3. Stakeholder Perspectives in Maritime Industries

2.3.1. Environmental and Safety Considerations

2.3.2. Economic and Operational Factors

2.3.3. Regulatory Compliance and Governance

2.3.4. Sustainability Consideration

2.3.5. Regional Implementation Variations

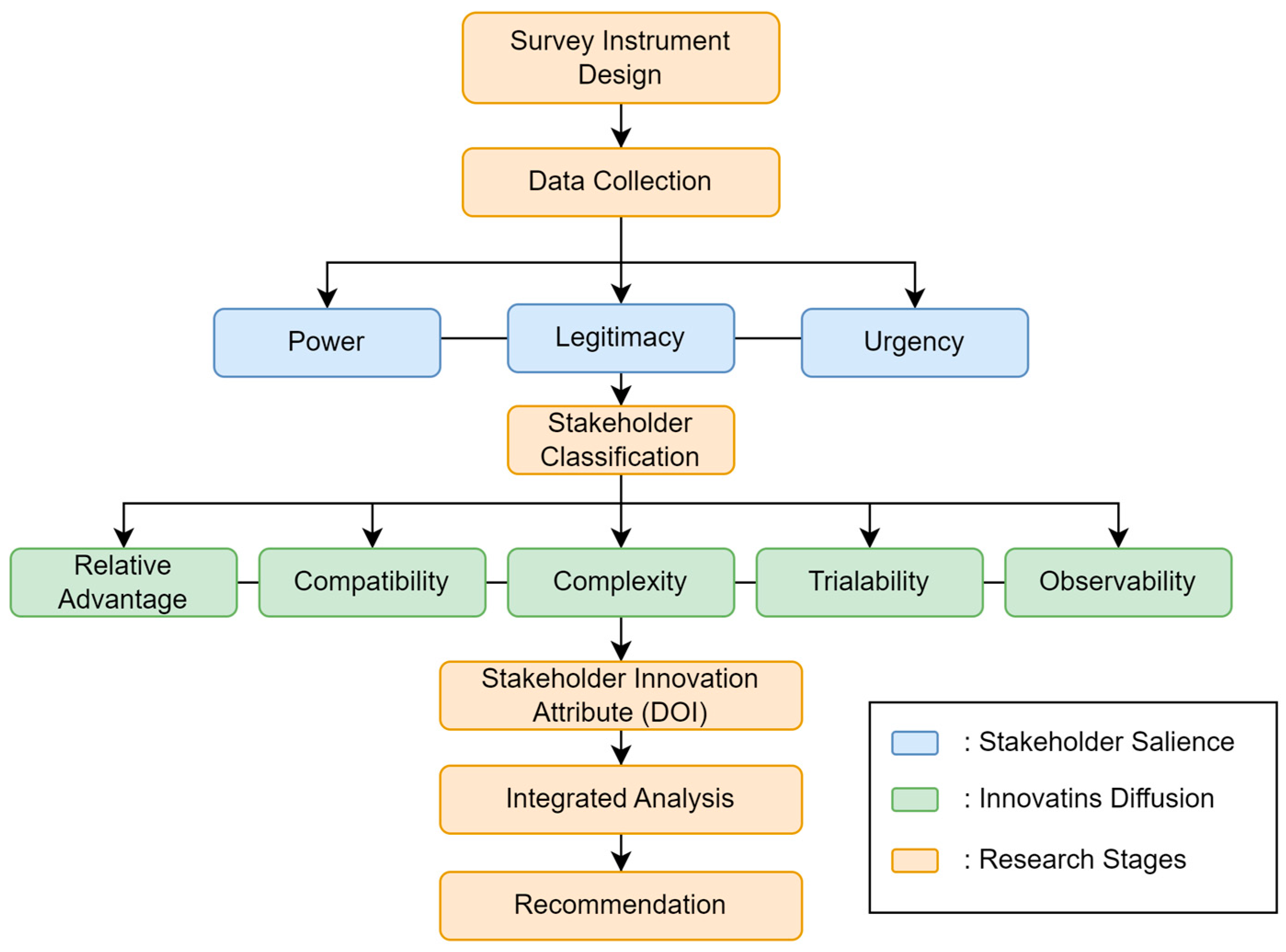

2.4. Theoretical Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Participant Selection and Sampling Strategy

3.3. Data Collection

- Based on the wording, phrasing, and emphasis of the stakeholders, researchers independently examined and analysed the raw textual material to extract relevant codes.

- These codes were then grouped into generic categories showing linked trends and stakeholder concerns. This approach is described by axial modelling.

- Theme Consolidation Following several rounds of discussion and synthesis, the codes were organised into five main themes closely related to the research topic and the stories of the stakeholders.

- Market demand themes concern financial and market advantages like the feasibility, the client’s interest, and the possibility of monetary loss.

- Workforce development themes emphasising the readiness of skills, human resources, and occupational health and safety (OHS) with a focus on skill development needs.

- Regulatory compliance themes in the context of environmental and recycling laws that include government support, enforcement, and clarification with concerns over policy ambiguity.

- Environmental themes include opinions on sustainable practices, environmentally acceptable recycling methods, and pollution control emphasising sustainability and waste management.

- Operational efficiency theme focuses on layout design, work division, infrastructure preparation, and time-saving strategies, highlighting facility and cost efficiency.

4. Result

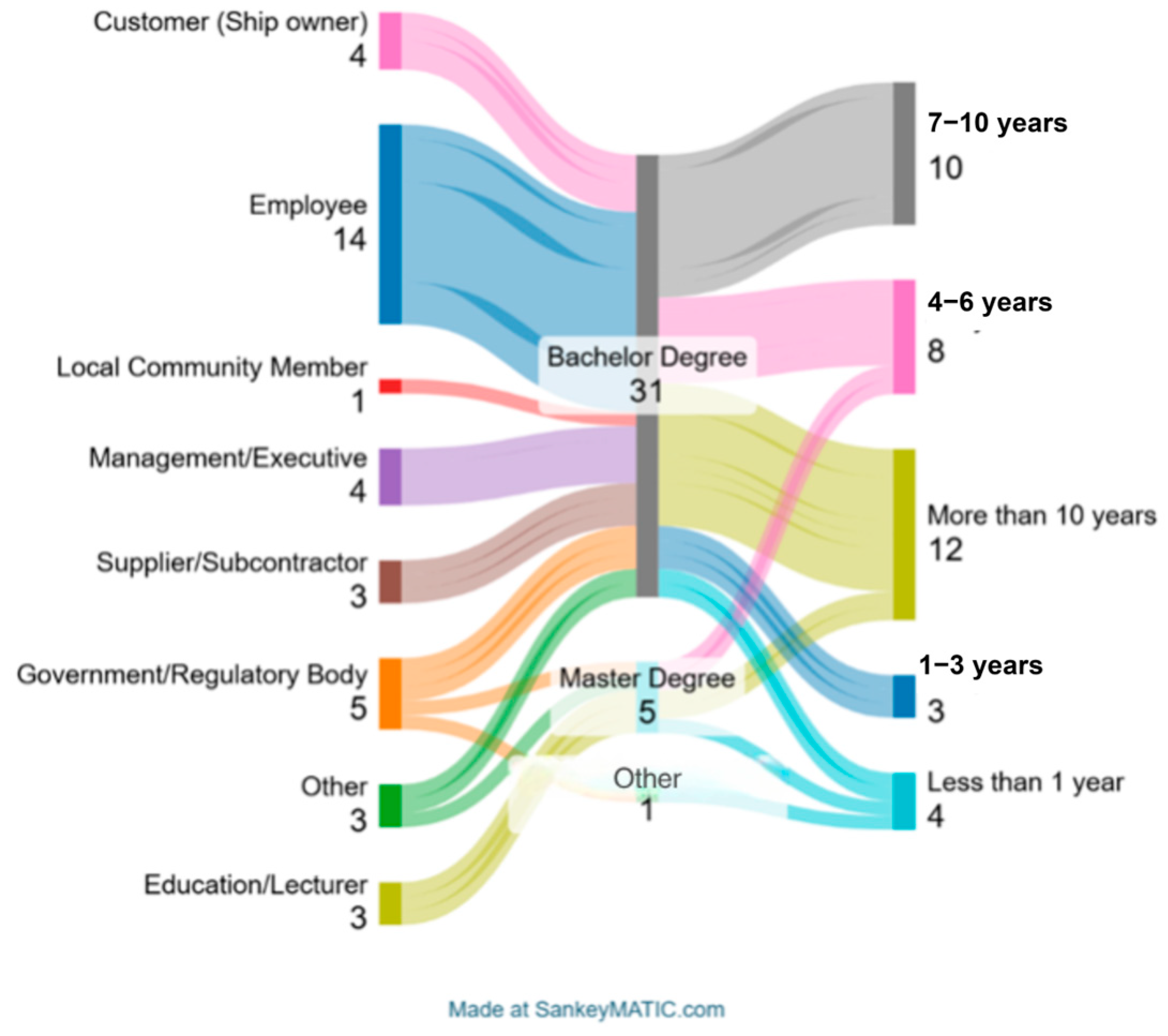

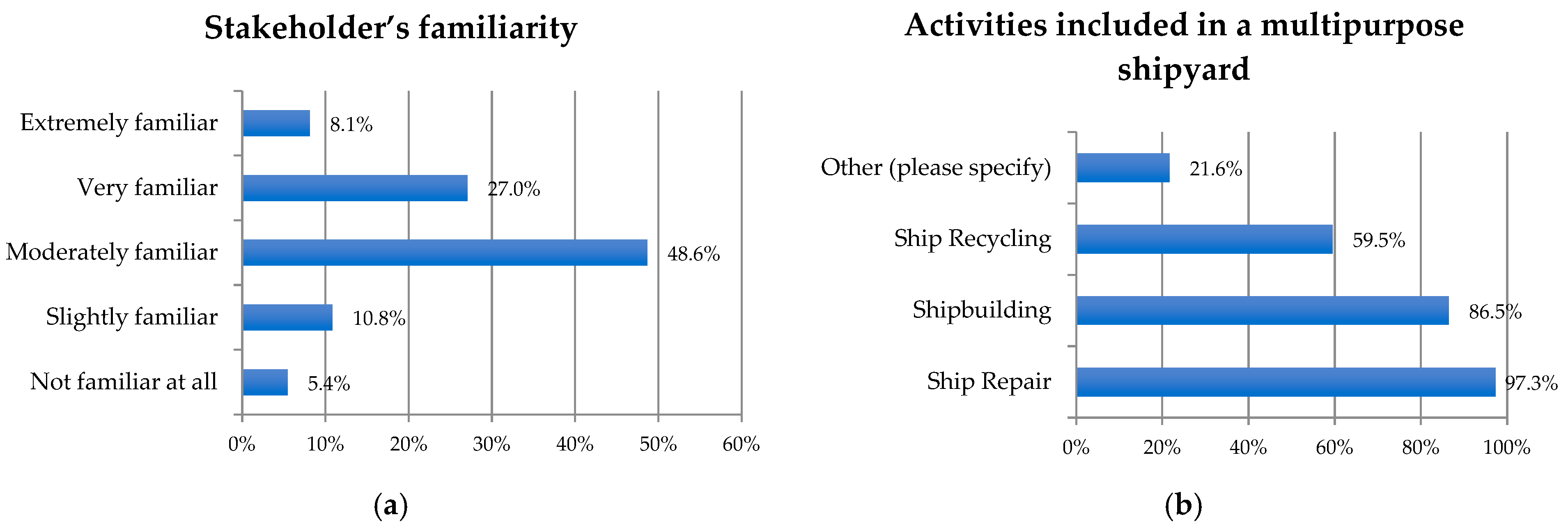

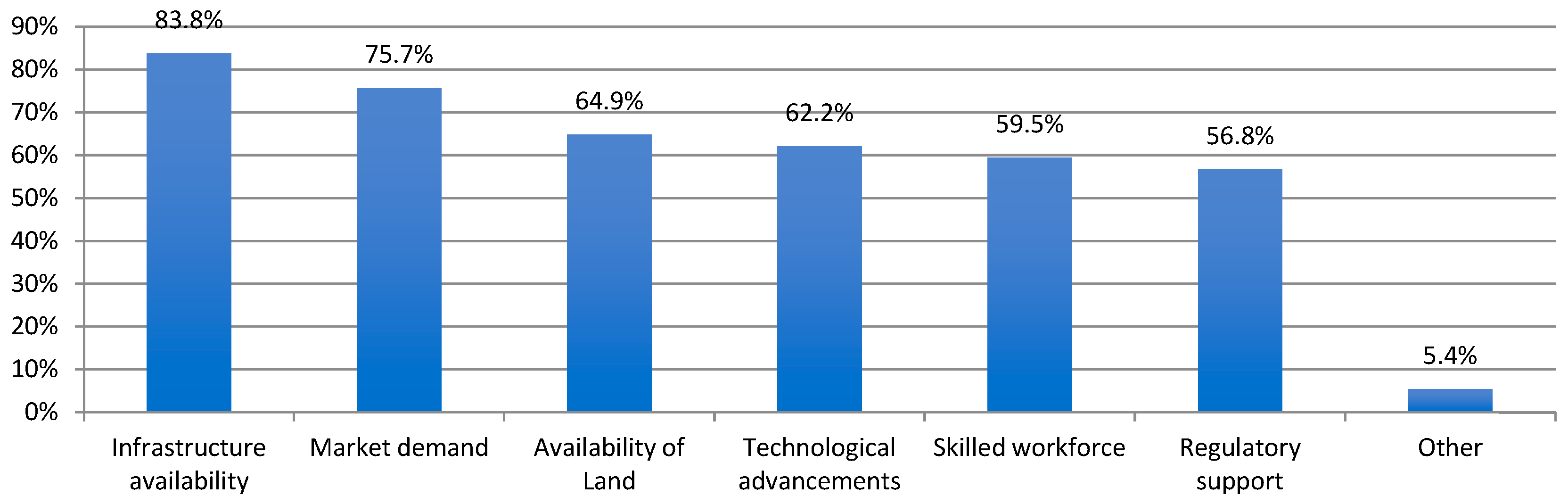

4.1. Stakeholder Profile

4.2. Stakeholder Perception of the Multipurpose Shipyard Concept

“A multipurpose shipyard could become a model for sustainable maritime development, provided it is supported by strong regulations.”

“It would be efficient in working time and increased financial income if we can ensure adequate space and smart layout.”

“We still need evidence and operational proof before we can scale the model nationwide.”

4.3. Feasibility of Integration

“Combining these two functions will improve financial turnover and efficiency due to shared dock and machinery use.”

“It is risky to conduct ship recycling near construction; clear environmental boundaries and protocols must be ensured.”

4.4. Stakeholder Perceptions of Benefits and Challenges

“Green recycling requires a whole new mindset, equipment, and enforcement. Without that, we risk undermining our environmental goals.”

“The biggest challenge is enforcement, without proper oversight, recycling becomes a liability rather than an opportunity.”

“The financial risks are too high unless we receive support from both the government and the market.”

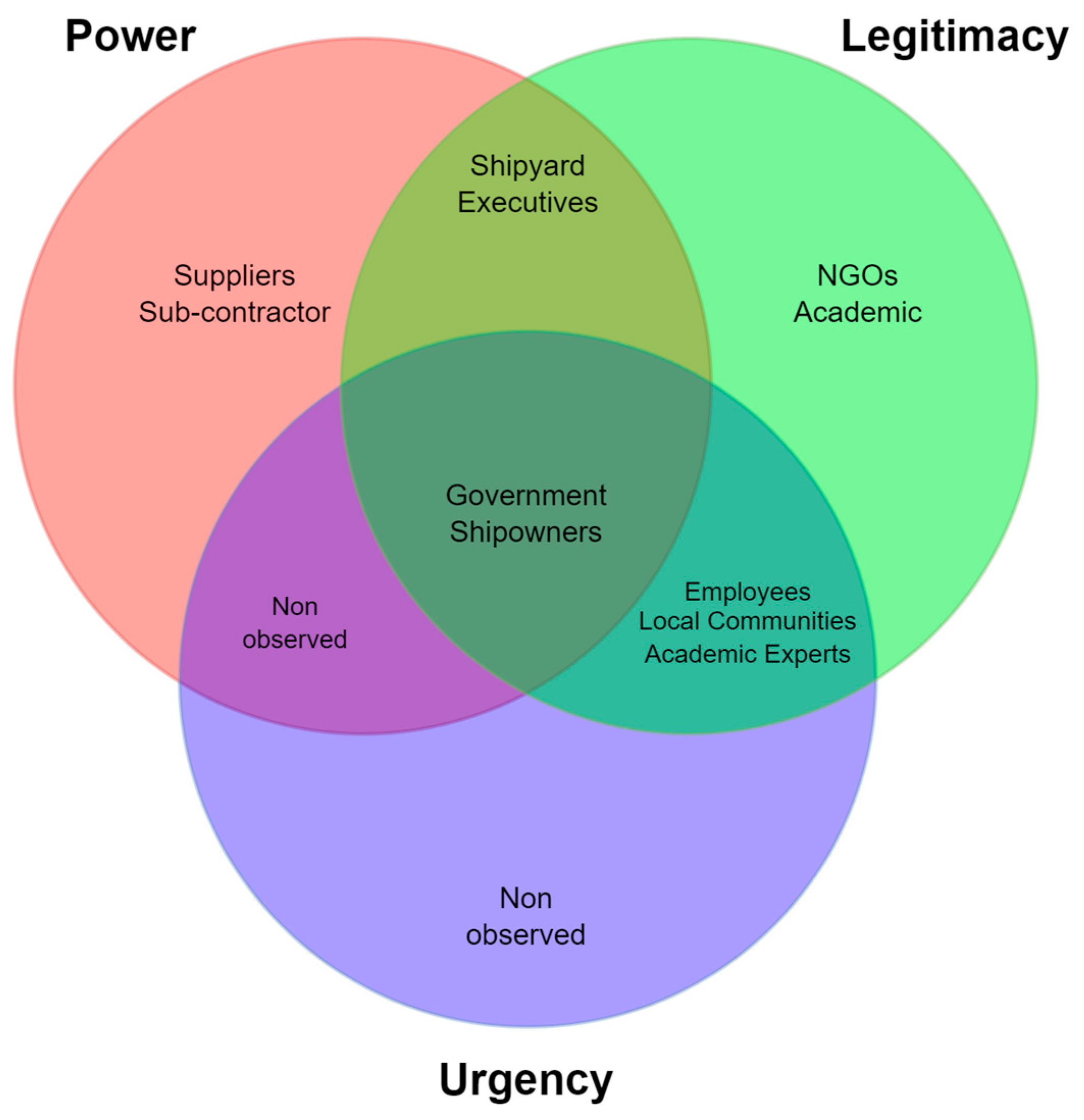

4.5. Stakeholder Classification and Salience Analysis

“Strong collaboration between government and regulators is essential to ensure smooth integration of all activities.”

“Maintaining competitiveness depends on enforcing ship recycling rules and guaranteeing quality, safety, and innovation.”

“This is acceptable as long as the shipyard has adequate space and management separation for each function.”

“We need a clear concept and training to safely integrate new operations. Human resource improvement is essential at all levels.”

“We need strong justification and evidence to promote integration. There are technical and training gaps that must be addressed.”

“Integrating operations needs targeted training across all levels, staff, subcontractors, and management.”

“Shipyards must prepare a structured plan for handling pollution and material flow, it’s not just a matter of engineering but of regulation.”

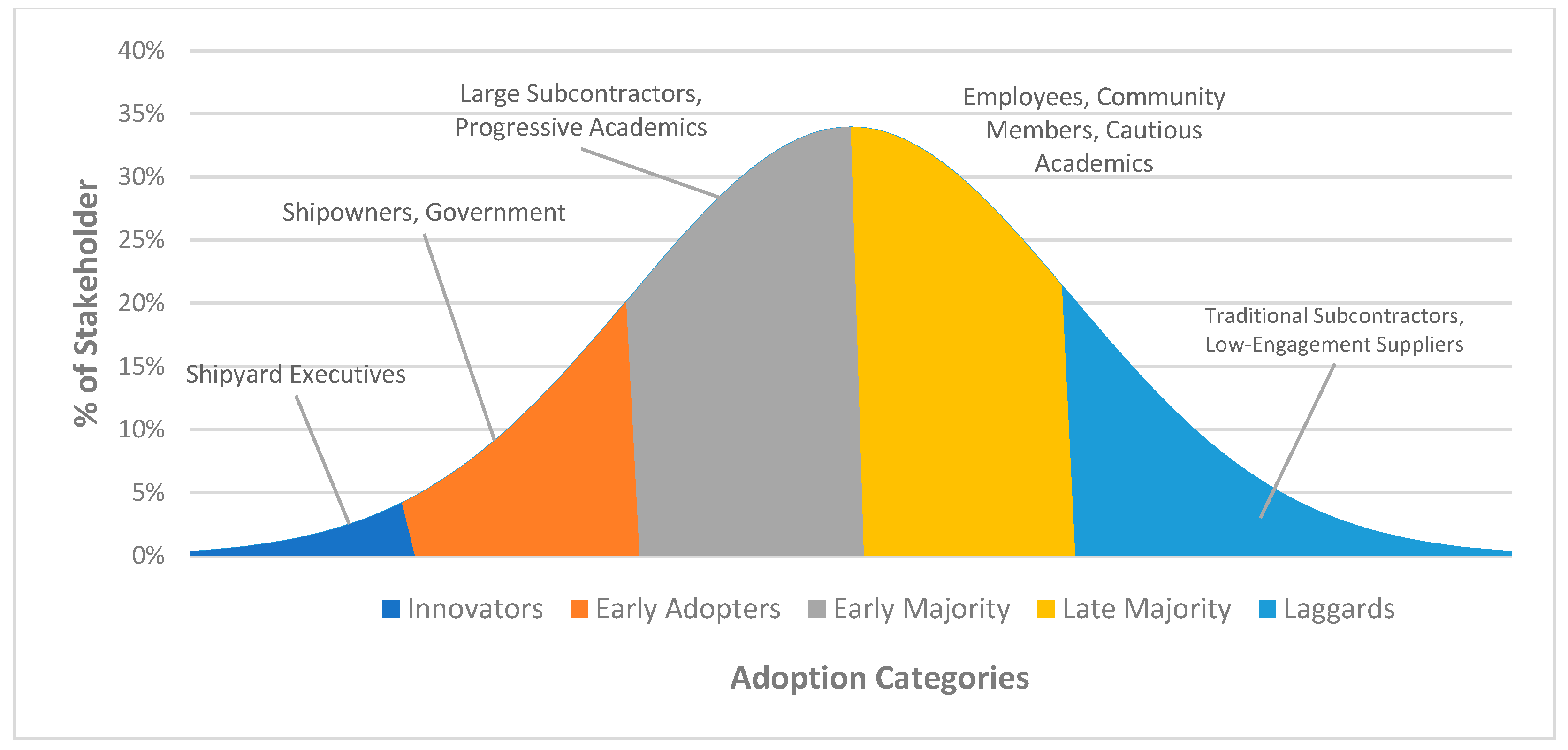

4.6. Innovation Adoption and Diffusion Among Stakeholders

“Understanding market dynamics and operational composition is essential; each activity must match demand, feasibility, and risk. We’ve already begun adjusting our shipyard operations to reflect this integration.”—Shipbuilding Executive.

“This transformation must align with long-term demand, risk management, and the strategic purpose of each operation within the yard.”Shipowners

“Shipyards must prepare a structured plan for handling pollution and material flow, and it’s not just a matter of engineering but of regulation.”Government official.

“Integration is challenging but possible if done with proper planning and skill development.”Shipyard Employee.

4.7. Joint Display of Mixed-Methods Findings

5. Discussion

5.1. Integrating Shipyard Services: Stakeholder Perspectives in Context

5.1.1. RQ1: Main Views of Indonesian Stakeholders on Multipurpose Shipyards

5.1.2. RQ2: Benefits Stakeholders See from Combining Shipbuilding, Repair, and Recycling

5.1.3. RQ3: Challenges Stakeholders Expect in Managing Multipurpose Shipyards

5.1.4. RQ4: Influence of Stakeholder Traits and Creative Dynamics on Acceptance of the Model

5.2. Stakeholder Dynamics: Salience and Innovation Diffusion

5.3. Implications for Policy and Sustainable Implementation

- Policy and Regulatory Framework: The regulatory framework requires further harmonisation with international standards. As of 2024, Indonesia has ratified several key IMO instruments, including MARPOL Annexes III, IV, V, and VI, through Presidential Regulation No. 29 of 2012, reflecting its ongoing commitment to expanding maritime environmental protections [22]. Indonesia should prioritise ratification of the Hong Kong International Convention (HKC), which entered into force on 26 June 2025, to establish robust ship recycling regulations, addressing stakeholder concerns about regulatory ambiguity and ensuring compliance with global standards. Recent IMO updates indicate Indonesia’s progress toward legal harmonisation, though formal accession is pending. Optimising permission procedures and providing centralised regulatory approval for integrated operations will diminish bureaucratic obstacles that hinder yard expansion, as specific stakeholders have cited regulatory uncertainty as a potential risk for delays or non-compliance. Policymakers should establish a maritime industrial working group of industry stakeholders to revise regulations and train enforcement authorities to supervise complex shipyard operations. This regulatory foundation is critical to support subsequent infrastructure and environmental policy actions.

- Environmental and Safety Measures: Implement robust environmental and occupational safety regulations to ensure sustainability. This requires ship recycling yards to possess ISO 30000 [6] certifications and to have appropriate waste management systems in place for oil, asbestos, scrap steel, and other materials. Certification, waste management, and transparent oversight are crucial to establishing trust and positioning Indonesia as a leader in sustainable ship recycling. Multipurpose shipyards enable resource recovery, material reuse, and operational innovation, advancing the circular economy and cost efficiency. These measures directly address environmental concerns raised by stakeholders and align with HKC mandates for Inventories of Hazardous Material (IHM) and Ship Recycling Plans (SRP). Brief comparative insight from Turkey (Aliga’s EU-approved recycling yards), the Philippines (voluntary HKC practices), and Vietnam (drydock recycling) suggests that robust environmental regulations and public–private collaboration can change sustainability outcomes, offering models for Indonesia to adapt. This focus on environmental safeguards sets the stage for infrastructure investment that must comply with these standards.

- Infrastructure and Investment Support: Given high capital costs and infrastructure needs, government investment facilitation will drive success. Financial incentives could include tax discounts on capital equipment for ship recycling facilities, as well as low-interest loans and grants for yards updating their infrastructure to support multipurpose shipyard activities. Public–private collaborations can help create green recycling zones near shipyards. A shipyard cluster where infrastructure can be pooled (e.g., a centralised hazardous waste treatment plant serving several shipyards) is one realistic idea from the feedback. Cluster models and shared investment reduce costs and comply with regulations. Indonesia, as the largest archipelagic country in the world with a strategic location, has a potentially large ship recycling market, with thousands of Indonesian-flagged ships over 25 years old eligible for recycling [29]. Stricter environmental risk assessment should be integrated into infrastructure planning and investment decision-making to address identified environmental challenges [70]. This focus on infrastructure and investment builds on regulatory and enviromental policies to provide the practical resources needed for implementation.

- Stakeholder Engagement and Integration: Participation in local forums and multi-stakeholder partnerships will build credibility, address concerns, and support implementation. Partnership must engage definitive stakeholders, such as government and shipowners, to facilitate policy alignment; dominant stakeholders, including shipyard executives, to secure operational buy-in; and dependent stakeholders, like employees and communities, to consider workforce and local impact issues. Mechanisms such as regular stakeholder workshops, joint task forces with IPERINDO, and public consultation platforms can enhance dialogue and consensus-building throughout the phases of the implementation roadmap. This engagement is essential for integrating diverse perspectives, reducing resistance, and ensuring the sustainable adoption of the multipurpose shipyard model, thereby connecting all policy dimensions through collaborative action.

5.4. Phased Implementation Roadmap and Scenario-Based Strategies for Regulatory Readiness Post-HKC Enforcement

5.4.1. Phased Implementation Roadmap for Multipurpose Shipyard in Indonesia

- Phase 1: Planning and Capacity Building (2026–2027).The initial phase emphasises feasibility assessment, policy revision, workforce development, and the selection of pilot sites. The government, specifically the Ministry of Transportation and the Ministry of Industry, leads policy and regulatory enhancements to align with international standards, including the Hong Kong Convention. Academics contribute by conducting research and implementing training programs that address sustainability and technical deficiencies. Key activities include drafting regulatory updates, conducting feasibility studies, initiating capacity-building efforts, and identifying potential pilot locations. The Ministry of Transportation monitors progress via regular stakeholder reporting to ensure alignment and transparency.

- Phase 2: Pilot Multipurpose Shipyard(s) (2028–2029).The second phase launches demonstration shipyards to assess integrated operation and monitor operational results. The government is responsible for pilot approvals and regulatory compliance, whereas shipyard executives handle operational integration and technical execution. Pilot shipyards, including those located in Batam and Cilegon, developed shared infrastructure and gathered data regarding efficiency, compliance, and environmental impact. A joint task force conducts regular reviews of pilot outcomes and gathers stakeholder feedback to facilitate continuous improvement.

- Phase 3: Evaluation and Scale-Up (2030–2031).Following Pilot implementation, evaluation and strategy refinement take place, leading to expansion into additional regions, including underdeveloped areas characterised by substantial infrastructure deficiencies. Government agencies assess pilot outcomes and modify policies for wider implementation, whereas shipowners stimulate demand and invest in enhanced facilities. The adaptation of operational models by shipyard executives facilitates scalability. The government publishes evaluation reports, and formal market commitments from shipowners support the expansion strategy.

- Phase 4: Full Integration and Continuous Improvement (2032–2035).The final phase seeks to build a network of multipurpose shipyards, institutionalise best practices, and ensure ongoing updates to standards as knowledge advances in environmental and safety. A national compliance committee ensures government oversight, whereas shipowners contribute to consistent market demand. Continuous training and enhancements in operations are emphasised to guarantee resilience and adaptability within the industry. Annual stakeholder forums facilitate feedback and promote iterative improvement.

5.4.2. Scenario-Based Strategies for Regulatory Readiness Post-HKC Enforcement

- Scenario 1: Proactive Alignment and Green TransitionIn an ideal scenario, Indonesia would immediately align its regulatory framework, ratify the HKC, and implement updated regulations before the commencement of Phase 1. Initial demonstration projects in shipyard hubs, such as Batam and Cilegon, exhibit compliance with HKC standards, featuring comprehensive hazardous material management, consistent third-party audits, and efficient stakeholder engagement. This scenario establishes Indonesia as a regional leader in sustainable ship recycling by the conclusion of phase 2, reducing environmental risks and fostering community trust.

- Scenario 2: Partial Readiness and uneven implementationA likely scenario, informed by current stakeholder feedback, suggests partial readiness: by June 2025, Indonesia is expected to have updated numerous regulations; however, enforcement remains inconsistent, particularly in less-developed regions. Particular shipyards achieve best practice certification, whereas others fail to meet the standard. Environmental risks persist in areas characterised by outdated infrastructure and inadequate control. The government and industry should strategically direct investment and training to address these gaps during the scale-up phase in Eastern Indonesia. Delay in achieving full compliance may undermine community trust and decrease regional competitiveness.

- Scenario 3: Regulatory Lag and Environmental LiabilityThe most pessimistic scenario anticipates regulatory inertia and postponed ratification of the HKC, resulting in ship recycling proceeding under fragmented national regulations. This results in ongoing environmental hazards, improper management of hazardous substances, and international clients redirecting vessels to alternative locations. Inadequate enforcement, particularly in underdeveloped regions, results in reduced economic opportunities and increased reputational risks for both governments and industries. Emergency interventions and significant recovery efforts may be necessary, potentially disrupting Phases 3 and 4 and postponing complete integration.

5.4.3. Key Recommendations for Regulatory Readiness

- Timely HKC Ratification and Regulatory HarmonisationEssential for ensuring legal certainty and standardised practices, which are crucial for attracting investment and facilitating smooth implementation, preferably before Phase 1

- Phased Implementation and Demonstration projectsCritical for capacity building, compliance demonstration, and informing strategies for scaling up, particularly through early pilots in the key shipyard hubs.

- Targeted Investment and Capacity BuildingFocusing on infrastructure and workforce training to address technical and operational disparities, especially in Eastern Indonesia, to avoid uneven sectoral development

- Robust Monitoring and Stakeholder EngagementEssential for managing environmental risks and ensuring community trust during all phases. This requires enforcement of transparency, continuous monitoring, and ongoing consultation with stakeholders.

5.4.4. International Comparison and Scope of Replicability

6. Conclusions and Further Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baso, S.; Musrina, M.; Anggriani, A. Strategy for Improving the Competitiveness of Shipyards in the Eastern Part of Indonesia. Kapal J. Ilmu Pengectahuan Dan. Teknol. Kelaut. 2020, 17, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, T.; Rizki, A.; Salsabila, U.; Muhammad, M.; Maulana, R.; A Chaliluddin, M.; Affan, J.M.; Thaib, R.; Suhendrianto, S.; Muchlis, Y. Literature review on shipyard productivity in Indonesia. Depik 2021, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agung, B.J.; Afriansyah, A. The Urgency Of Green Ship Recycling Methods And Its Regulations In Indonesia From The International Law Perspective. Unram Law Rev. (ULREV) 2022, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriadi, F.; Ayob, A.F.M. Optimizing Traditional Shipyard Industry: Enhancing Manufacturing Cycle Efficiency for Enhanced Production Process Performance. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Technol. Oper. Manag. 2023, 1, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainol, I.; Siow, C.L.; Ahmad, A.F.; Zoolfakar, M.R.; Ismail, N. Hybrid shipyard concept for improving green ship recycling competitiveness. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 114321, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 30000:2009; Ships and Marine Technology—Ship Recycling Management Systems—Specifications for Management Systems for Safe and Environmentally Sound Ship Recycling Facilities. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- IMO. The Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/about/Conventions/pages/the-hong-kong-international-convention-for-the-safe-and-environmentally-sound-recycling-of-ships.aspx (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Rogers, E.M.; Singhal, A.; Quinlan, M.M. Diffusion of innovations. In An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 432–448. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista.com, Topic: Maritime Industry in Indonesia, Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/12042/maritime-industry-in-indonesia/ (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- trade.gov, Indonesia-Market Overview. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/indonesia-market-overview (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- business-indonesia.org, Maritime|Business-Indonesia. Available online: https://business-indonesia.org/maritime (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Mustajib, M.I.; Ma’RUf, B.; Basuki, S.S.A.; Putera, E.Y.; Irawan, B.; Baroroh, I.; Sutrisno, S.; Dewi, D.A. Prioritizing Key Internal Strategic Factors for Long-term Competitiveness of Medium-sized Shipyards using the DEMATEL-ANP Method. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komara, K.; Iroth, T.P.; Sungkono, S.; Saragih, J.S.; Sahubawa, S.U.; Dwiwanti, M. The Potential of Indonesias Ship Engine Market to Attract Foreign Investors for Domestic Manufacturing. Equity 2024, 12, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indonesian Shipbuilding and Offshore Association (IPERINDO). Member Directory 2025—Chapter 04: Shipyard Industry. Available online: https://iperindo.co.id/list-directory/chapter-04/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Firmansyah, F.; Arta, N.; Gurning, R.O.S. A Study on Indonesia Shipbuilding Competitiveness Challenge and Opportunity. In Proceeding of the Marine Safety and Maritime Installation (MSMI 2018), Bali, Indonesia, 9–11 July 2018; Clausius Scientific Press: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MARPOL 73/78; International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973 as modified by the Protocol of 1978. International Maritime Organization: London, United Kingdom, 1978. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/knowledgecentre/conferencesmeetings/pages/marpol.aspx (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- IMO (Ed.) Hong Kong Convention: Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships, 2009; with the Guidelines for Its Implementation, 2013rd ed.; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- IMO. Guidelines for the Development of the Inventory of the Hazardous Materials. 2023. Available online: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/Documents/MEPC.379(80).pdf (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Oktaviany, M.A. Challenges for the Ratification of the Hong Kong Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships, 2009 in Indonesia, WMU. 2019. Available online: https://commons.wmu.se/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2168&context=all_dissertations (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- IMO. International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL). Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/about/Conventions/Pages/International-Convention-for-the-Prevention-of-Pollution-from-Ships-(MARPOL).aspx (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- IMO. Indonesia Ratifies Several IMO Instruments, Indonesia Ratifies Several IMO Instruments. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/Pages/33-indonesiaratifies.aspx (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Sudirman, A.; Maulana, M.; Yola, A. Legal Cooperation in the ASEAN Maritime Environment in the Free Trade Era: Its Implication for Indonesia. Hasanuddin Law Rev. 2022, 8, 288–298. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Basel Convention on Hazardous Wastes. 1989. Available online: http://www.basel.int (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Basel. Basel Convention Regional Centre for South-East Asia in Indonesia (BCRC Indonesia). Available online: https://www.basel.int/?tabid=4845 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Ministry of Transportation of Indonesia. Peraturan Menteri Perhubungan Republik Indonesia Nomor: Pm 29 Tahun 2014 Tentang Pencegahan Pencemaran Lingkungan Maritim, Rules and Regulation. 2014. Available online: https://hubla.dephub.go.id/storage/portal/documents/post/6659/pm_29_tahun_2014.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- President of Republic Indonesia. Undang-Undang No. 17 Tahun 2008 Tentang Pelayaran (Law 17/2008 on Shipping). 2008. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Download/28451/UU%20Nomor%2017%20Tahun%202008.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Ishak, N.; Meica, M. Implementation of Cabotage Principle in Indonesia Territory and Its Implication for Shipping: A Study from Law Perspective. In Proceeding of the Marine Safety and Maritime Installation (MSMI 2018), Bali, Indonesia, 9–11 July 2018; Clausius Scientific Press: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariya, S.; Suastika, K.; Arif, M.S. Design of Sustainable Ship Recycling Yard in Madura, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the Conference of Theory and Application on Marine Technology, Surabaya, Indonesia, 15–16 December 2016; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/36352866/PROCEEDING_Marine_Technology_for_Fulfilling_Global_Maritime_Axis (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Zainol, I.; Loon, S.C.; Fuad, A.F.A.; Ismail, N.; Rosli, K. Integrating Ship Recycling Facility into Existing Shipyard: A Study of Malaysian Shipyard. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 32, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabane, H. Design of a Small Shipyard Facility Layout Optimised for Production and Repair. 2004. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/93033554/Layout-1-Design-of-a-Small-Shipyard-Facility-Layout-Optimised (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Sunaryo, S.; Santoso, F.Y. Conversion Design of an Idle Ferry Port into Green Ship Recycling Yard. In Proceedings of the MARTEC 2022, The International Conference on Marine Technology, BUET, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 21–22 December 2022; SSRN: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sunaryo; Tjitrosoemarto, B.A. Integrated ship recycling industrial estate design concept for Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 972, 012042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, A.; Harahab, N.; Putra, F.; Kurniawan, A. Environmental sustainability criteria in the multi-oriented shipbuilding industry in Indonesia. Aust. J. Marit. Ocean. Aff. 2023, 16, 410–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.Q. An Assessment of Development Opportunities of Ship Recycling Facilities Based on the Shipbuilding Yards Infrastructures in Vietnam; World Maritime University: Malmö, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- amayadockyard.com. Amaya Dockyard and Marine Services. Available online: https://amayadockyard.com/salvaging-shipbreaking/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- amayadockyard.com. Shipbreaking in the Philippines: Marine Engineers Guide 2023. Available online: https://amayadockyard.com/ship-repair/shipbreaking-in-the-philippines-marine-engineers/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- marina.gov.ph, Philippines Marina Hosts IMO Workhop on Safe Ship Recycling as Hong Kong Convention Approchaes Enactment, Maritime Industry Authority. Available online: https://marina.gov.ph/2024/11/07/philippines-marina-hosts-imo-workhop-on-safe-ship-recycling-as-hong-kong-convention-approchaes-enactment/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Vakili, S.; Schönborn, A.; Ölçer, A.I. The road to zero emission shipbuilding Industry: A systematic and transdisciplinary approach to modern multi-energy shipyards. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2023, 18, 100365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NGO Shipbreaking Platform. Ship Recycling in Turkey Challenges and Future Direction. 2023. Available online: https://shipbreakingplatform.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Turkey-Report-2023-NGOSBP.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Senturk, Ö.U. The interaction between the ship repair, ship conversion and shipbuilding industries. OECD J. Gen. General. Pap. 2011, 2010, 7–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, S.V.; Ölçer, A.I.; Schönborn, A. Identification of Shipyard Priorities in a Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Environment through a Transdisciplinary Energy Management Framework: A Real Case Study for a Turkish Shipyard. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14001:2015; Environmental Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Barua, S.; Rahman, I.M.M.; Hossain, M.M.; Begum, Z.A.; Alam, I.; Sawai, H.; Maki, T.; Hasegawa, H. Environmental hazards associated with open-beach breaking of end-of-life ships: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 30880–30893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcaide, J.I.; Rodríguez-Díaz, E.; Piniella, F. European policies on ship recycling: A stakeholder survey. Mar. Policy 2017, 81, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiyanto, A.; Kusnoputranto, H.; Widjaja, R.S.; Lestari, F. Environmental Insurance Model in the Shipyard Industry. Asian J. Appl. Sci. 2016, 4, 577–584. [Google Scholar]

- Schøyen, H.; Burki, U.; Kurian, S. Ship-owners stance to environmental and safety conditions in ship recycling. A case study among Norwegian shipping managers. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2017, 5, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazim, H.M.; Abdullah, J. Malaysia Shipbuilding Industry: A Review on Sustainability and Technology Success Factors. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2022, 28, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaabi, M.A.; Pech, R. Strategic corporate governance stakeholder complexities in strategic decision implementation (sdi): The shipbuilding industry in Abu Dhabi. J. Dev. Areas 2015, 49, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantan, M.; Camgöz-Akdağ, H. Sustainability Concept in Turkish Shipyards; Presented at the SDP 2020; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2020; pp. 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo, E.S.; Pereira, N.N. Can ship recycling be a sustainable activity practiced in Brazil? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 224, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, A.; Harahab, N.; Putra, F.; Kurniawan, A.; Poundra, G.A.P. Concept of Multi-Orientation Shipyard Industry Development Environmentally Friendly and Sustainable. Int. J. Mar. Eng. Innov. Res. 2024, 9, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tola, F.; Mosconi, E.M.; Marconi, M.; Gianvincenzi, M. Perspectives for the Development of a Circular Economy Model to Promote Ship Recycling Practices in the European Context: A Systemic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunaryo, S.; Aidane, M.A. Development Strategy of Eco Ship Recycling Industrial Park. Evergreen 2022, 9, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silveira, C.A.M.; De Castro Bertagnolli, D.; Pereira, N.N.; Da Cunha Jácome Vidal, P.; De Oliveira, J.A. Mapping sustainable practices in ship recycling. Mar. Syst. Ocean Technol. 2025, 20, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, T.; Chang, H. A Study on User-Oriented and Intelligent Service Design in Sustainable Computing: A Case of Shipbuilding Industry Safety. Sustainability 2017, 9, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Qiao, W.; Luo, H.; He, P. Human factor risk modeling for shipyard operation by mapping fuzzy fault tree into bayesian network. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tola, F.; Mosconi, E.M.; Gianvincenzi, M. Demolition of the European ships fleet: A scenario analysis. Mar. Policy 2024, 166, 106222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabowo, H. The Methodologist for Regulation a New Policy of Ship Recycling in Indonesia Based on HKC 2009; World Maritime University: Malmö, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hayman, B.; Dogliani, M.; Kvale, I.; Fet, A.M. Technologies for Reduced Environmental Impact from Ships-Ship Building, Maintenance and Dismantling Aspects. 2023. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Brian-Hayman/publication/253362781_Technologies_for_reduced_environmental_impact_from_ships_-_Ship_building_maintenance_and_dismantling_aspects/links/02e7e52a0c9c8eee7d000000/Technologies-for-reduced-environmental-impact-from-ships-Ship-building-maintenance-and-dismantling-aspects.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Egorova, E.; Torchiano, M.; Morisio, M.; Wohlin, C.; Aurum, A.; Svensson, R.B. Stakeholders Perception of Success: An Empirical Investigation. In Proceedings of the 2009 35th Euromicro Conference on Software Engineering and Advanced Applications, Patras, Greece, 27–29 August 2009; pp. 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskafi, M.; Fazeli, R.; Dastgheib, A.; Taneja, P.; Ulfarsson, G.F.; Thorarinsdottir, R.I.; Stefansson, G. Stakeholder salience and prioritization for port master planning, a case study of the multi-purpose Port of Isafjordur in Iceland. Eur. J. Transp. Infrastruct. Res. 2019, 19, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, M.D.; Azmi, F.; Puentes, M. Stakeholder perceptions and implications for technology marketing in multi-sector innovations: The case of intelligent transport systems. Int. J. Technol. Mark. 2009, 4, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sooprayen, K.; Van De Kaa, G.; Pruyn, J.F.J. Factors for innovation adoption by ports: A systematic literature review. J. Ocean Eng. Mar. Energy 2024, 10, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.; Klajnberg, P.M.; Barcaui, A.B.; Castro, M.; Klajnberg, P.M.; Barcaui, A.B. The Impact of Stakeholder Salience in the Relationship between Stakeholder-Oriented Governance Practices and Project Success. In Corporate Governance-Evolving Practices and Emerging Challenges; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariyanto, N.; Gutami, I.; Qonita, Z.; Shabrina, N.; Wibowo, D.A.; Muhtadi, A. The Development of Ship Recycling Facility Cluster in Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1166, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, P.; Fadillah, A. Study on development of shipyard type for supporting pioneer ship in Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 339, 012045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiskanen, E.; Hyvönen, K.; Laakso, S.; Laitila, P.; Matschoss, K.; Mikkonen, I. Adoption and Use of Low-Carbon Technologies: Lessons from 100 Finnish Pilot Studies, Field Experiments and Demonstrations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensrec, International Maritime Organization Programme No. TC/1514 “SENSREC” Safe and Environmentally Sound Ship Recycling in Bangladesh–Phase I December 2016, IMO, Bangladesh, Programme No. TC/1514. 2024. Available online: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/PartnershipsProjects/Documents/Ship%20recycling/WP1b%20Environmental%20Impact%20Study.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Stakeholder Support | The level of Endorsement or positive perception expressed by stakeholders (e.g., government, shipowner, shipyard executives, employees, etc.) towards the concept of multipurpose shipyards, often measured through survey responses or qualitative feedback. |

| Integration Feasibility | The perceived practicality or likelihood of successfully combining shipbuilding, repair and recycling activities within a single shipyard facility, as assessed by stakeholders based on operational, technical, and regulatory factors. |

| Multipurpose Shipyard | A shipyard facility designed to perform multiple activities such as shipbuilding, repair and recycling under a unified operational framework, aiming to optimise resource use, reduce downtime and enhance economic and environmental sustainability. |

| Operational Efficiency | The improvement in performance and reduction in redundancy achieved by integrating multiple shipyard functions lead to cost savings, reduced downtime, and better resource utilisation. |

| Regulatory Compliance | The adherence to national and international laws, standards and conventions (e.g., Hong Kong Convention) governing shipyard operations, particularly in environmental and safety aspects, as a critical factor for multipurpose shipyard implementation |

| Regulatory Level | Key Regulation(s) | Features/Requirements | Relevance to Multipurpose Shipyards | Status in Indonesia | Implementation Gaps/Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| International (IMO) | Hong Kong International Convention (HKC) | Requires Inventory of Hazardous Materials (IHM), Ship Recycling Plan, certified facilities [18,19] | Gold standard for safe recycling; aligns with national rules | Not yet ratified; enters into force globally June 2025 [7] | Indonesia not party; domestic law lags HKC; pilot projects only [20] |

| MARPOL 73/78 [21] | Limits oil and pollutant discharges from ships | Applies to environmental compliance in yard operations | Ratified by Indonesia [22] | Enforcement and monitoring capacity varies across regions | |

| Regional | ASEAN Marine Environmental Law/Cooperation | Marine pollution prevention, transboundary standards, cooperative action | Encourages harmonised approaches and regional benchmarks | Indonesia participates, but implementation is uneven [23] | National legal harmonisation slow; variable local uptake |

| Basel Convention [24] | Controls the cross-border movement of hazardous waste, applies to shipbreaking | Mandates the safe export/import of hazardous waste from ships | Ratified and in force [25] | Some weak points in national enforcement and tracking | |

| National (Indonesia) | PM 29/2014 [26] | Prevents marine pollution, regulates ship recycling and hazardous material handling | Main legal framework for shipyard pollution control | In force; updated by the Ministry of Transportation No. 24/2022 | Enforcement is inconsistent, especially outside Java/Batam |

| Law No. 17/2008 (Shipping), Gov. Reg 21/2010, GR 101/2014 [27] | Environmental impact assessment (AMDAL), hazardous waste management, operational licencing | Determines site approval, waste protocols, and permits | Enacted; national coverage | Limited regional enforcement and monitoring capacity [28] | |

| Local/Provincial | Regional zoning and environmental licencing | Site-specific permits, zoning for shipyard activity, local AMDAL requirements [29] | Determines legal operation and environmental approval | Varies by region (often strict in Java, weaker in eastern provinces) [1] | Legal patchwork creates uncertainty, slows investment |

| Stakeholder | Relative Advantage | Compatibility | Complexity | Trialability | Observability | Total DOI Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shipyard Executives | 4.80 | 4.50 | 2.90 | 3.60 | 3.80 | 19.80 |

| Government | 4.60 | 4.40 | 3.00 | 3.40 | 3.60 | 19.00 |

| Shipowners | 4.50 | 4.20 | 3.10 | 3.30 | 3.50 | 18.40 |

| Employees | 3.90 | 3.60 | 3.70 | 2.90 | 3.10 | 15.80 |

| Academics | 4.10 | 3.90 | 3.90 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 16.10 |

| Suppliers | 3.80 | 3.70 | 3.60 | 2.70 | 2.80 | 15.40 |

| Community | 3.70 | 3.40 | 4.10 | 2.50 | 2.60 | 14.10 |

| Stakeholder | Market Demand | Workforce Dev. | Regulatory | Environmental | Operational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academics | 3.6 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 4.2 |

| Community | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 3.4 |

| Employees | 3.5 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 4 |

| Government | 4 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 3.8 |

| Shipowners | 4.3 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 4.2 |

| Shipyard Managers | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 4.3 |

| Suppliers | 4.1 | 3.7 | 4 | 3.5 | 3.9 |

| Qualitative Theme | Quantitative Survey Score/Percentage | Description/Illustrative Stakeholder Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Market Demand | 3.8 (mean score)/75.7% identified as critical enabling factor | Stakeholders perceive strong market demand for integrated shipyard services, emphasising Indonesia’s strategic maritime position and the need to reduce reliance on foreign facilities. |

| Workforce Development | 3.9 (means score)/40.5% cited skill shortages as a challenge | Emphasis on the need for targeted training and upskilling to address gaps in modular construction, recycling, and advanced operations. Stakeholders highlighted the importance of workforce readiness for successful integration. |

| Regulatory Compliance | 4.0 (mean score)/45.9% cited regulatory ambiguity as a challenge. 56.8% stressed regulatory support as enabling factor | High importance is placed on clear regulations and compliance, with calls for harmonisation with international standards (e.g., the Hong Kong Convention) and consistent enforcement across regions. |

| Environmental Considerations | 3.6 (mean score)/32.4% saw significant environmental benefits | Concerns about sustainable practices, pollution control, and hazardous waste management. Stakeholders noted the potential for multipurpose shipyards to contribute to a circular economy, but also highlighted the need for robust environmental safeguards |

| Operational Efficiency | 4.2 (mean score)/32.4% saw significant environmental benefits | Stakeholders expect significant improvements in efficiency through integration, including reduced downtime, shared infrastructure, and cost savings. Operational efficiency was the most frequently cited benefit in open-ended responses. |

| Stakeholder Group | Salience Attributes | Adoption Category | Top Concern Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government | Definitive | Early Adopter | Regulatory compliance |

| Shipyard Executive | Dominant | Innovator | Operational efficiency |

| Shipowners | Definitive | Early Adopter | Market demand |

| Employees | Dependent | Late Majority | Workforce development |

| Suppliers | Dependent | Laggard | Process disruption |

| Academics | Discretionary | Late Majority | Sustainability |

| Community | Dependent | Late Majority | Environmental impact |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arif, M.S.; Gunbeyaz, S.A.; Kurt, R.E.; Supomo, H. Stakeholder Perspectives on Multipurpose Shipyard Integration in Indonesia: Benefits, Challenges, and Implementation Pathways. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8368. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188368

Arif MS, Gunbeyaz SA, Kurt RE, Supomo H. Stakeholder Perspectives on Multipurpose Shipyard Integration in Indonesia: Benefits, Challenges, and Implementation Pathways. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8368. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188368

Chicago/Turabian StyleArif, Mohammad S., Sefer A. Gunbeyaz, Rafet E. Kurt, and Heri Supomo. 2025. "Stakeholder Perspectives on Multipurpose Shipyard Integration in Indonesia: Benefits, Challenges, and Implementation Pathways" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8368. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188368

APA StyleArif, M. S., Gunbeyaz, S. A., Kurt, R. E., & Supomo, H. (2025). Stakeholder Perspectives on Multipurpose Shipyard Integration in Indonesia: Benefits, Challenges, and Implementation Pathways. Sustainability, 17(18), 8368. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188368