1. Introduction

The tourism industry plays a crucial role in promoting urban economic development. In 2023, tourism contributed 9.1% to global GDP, reflecting a 23.2% increase from 2022 levels, according to data from the World Travel & Tourism Council [

1]. Additionally, tourism consumption has become the main source of income, employment, private sector growth, and infrastructure development in many countries. Moreover, the growth and rise of tourism have a positive effect on all aspects of urban development [

2,

3]. Particularly in small and medium-sized cities with tourism-oriented industrial structures, as well as in cities reliant on traditional industrialization (such as Gunsan and Incheon in Korea), challenges such as industrial restructuring or insufficient economic vitality often lead these regions to adopt homogenized development models and standardized construction mechanisms in pursuit of economic growth and structural optimization. However, this convergence strategy has led to the “de-localization” or “non-localization” of tourist destinations in terms of culture and experience; that is, attractions lack regional characteristics and uniqueness, showing a high degree of homogeneity, which is described by scholars as “McDonaldization of attractions” [

4]. This phenomenon weakens tourists’ interest and reduces the appeal of a destination, thus posing a threat to the sustainable development of the tourism industry. Consequently, tourists are increasingly demanding authentic and meaningful experiences [

5]. As demand becomes increasingly diverse and complex, the tourism industry is gradually moving towards a new stage of horizontal development. This horizontal development requires tourist cities to focus on diversification and sustainability in their development planning and explore the possibility of deep integration with other industries [

6]. However, in the context of rapid global economic development, many tourist cities face a series of severe challenges, such as aging urban buildings and deteriorating infrastructure [

7]. These challenges not only limit the competitiveness of tourist cities but also pose a major obstacle to the sustainable and healthy development of their tourism industries. Therefore, it is necessary to formulate scientific and reasonable development strategies to deal with the challenges above and enhance overall attractiveness. Scholars have proposed concepts such as creative tourism, cultural tourism, regenerative tourism, healthy tourism, green tourism, and dark tourism to help tourist cities transform their tourism landscapes [

8,

9,

10,

11].

Regenerative tourism focuses on the positive role of tourism in promoting sustainable development, revitalization, and the well-being of local communities [

12]. Compared with sustainable tourism, regenerative tourism goes a step further, being aligned with many sustainable development goals. The core focus of regenerative tourism is not limited to the sustainability of the tourism industry but rather emphasizes how to use tourism as a medium to promote the well-being of local communities, revitalize economies, and enhance overall sustainable development [

11]. For example, South Korea has converted idle industrial facilities into recycled cafes. The unique cafe atmosphere formed by the old architectural style is eye-catching [

13]. Transforming abandoned urban spaces or buildings into vibrant spaces can have a positive impact on the daily lives and quality of life of citizens, as noted by many researchers [

14,

15,

16]. Therefore, as an emerging sustainable development model, regenerative tourism has attracted widespread attention and has been implemented around the world. Taking South Korea as an example, the “Urban Regeneration Plan” initiated by its government has successfully implemented more than 500 urban revitalization projects, aiming to achieve the synergistic goals of regional economic revitalization and sustainable urban development through the dual strategies of spatial function reconstruction and industrial transformation and upgrading. As a crucial practical carrier of regenerative tourism, regenerative composite cultural spaces are generated through the transformation of spatial resources such as idle industrial facilities. Driven jointly by policy orientation and industrial demand, these spaces have gradually evolved into new forms of development that combine economies of scale with industrial potential, embodying the concretization and practical implementation of the regenerative tourism model.

The rise of regenerative tourism is widely regarded as an extension or improved form of cultural tourism and green tourism [

17,

18,

19]. Compared with traditional cultural tourism, regenerative tourism emphasizes deeper interaction and co-creation between tourists and destination culture, pushing tourists from passive observers to active participants and experiencers. When tourism meets tourists’ needs for personalized experience and an in-depth cultural exchange, tourists tend to show higher loyalty and destination stickiness [

4]. Within the business model of regenerative tourism, tourists serve as key participants in achieving sustainable development, and their engagement directly influences the long-term sustainability and developmental trajectory of regenerative composite cultural spaces. Additionally, studies have pointed out that the degree of tourists’ participation in regenerative tourism can be regarded as a key factor in predicting tourists’ satisfaction. This view shows that the degree of tourists’ active participation and interaction in the regenerative tourism experience not only affects their overall evaluation of the tourism experience but also plays a significant role in their satisfaction level [

12].

Tourist projects are often operated and managed by practitioners with creative and cultural sensitivity, such as artists, “lifestyle entrepreneurs,” and “cultural creators” [

4]. This supply-oriented model often ignores tourists’ needs and opinions. However, tourists’ needs and perceived value are the main factors affecting their behavioral intentions. Further, tourists’ perceptions of a destination city may significantly influence their willingness to travel, and this influence may be positive or negative [

20]. Additionally, studies have shown that the image of a city plays a key role in tourists’ destination preferences and choices [

21]. Therefore, while exploring tourists’ demand for destination tourism, the focus should be placed on the intangible assets (city image) inherent in the destination to achieve a better balance between the supply and demand of regenerative tourism.

In recent years, cultural tourism has been recognized by the UNWTO as an important component of international tourism, accounting for more than 39% of the total number of tourists worldwide [

22]. Further, tourists’ preference for green tourism is significantly higher than their preference for other forms of tourism: 87% of tourists prefer green and sustainable tourism products, and 67% of tourists are willing to pay extra for a green tourism experience [

6]. This outcome shows that green and cultural factors play an important role in tourists’ consumption preferences. Further understanding of tourists’ green consumption values and cultural consumption values can not only deepen the present knowledge of their behaviors and needs but also provide a suitable basis for improving the competitiveness of tourist destinations. Therefore, this study emphasizes the need to further explore the interactive relationship between tourists and regenerative tourism and construct a relationship model between tourists and regenerative composite cultural spaces. Through this model, this research aims to clarify the underlying mechanism and pathways through which cultural consumption values and green consumption values influence this relationship. Ultimately, this study aims to provide a comprehensive analytical framework for the theoretical development and practical application of regenerative tourism.

This study aims to answer the following key questions:

In the proposed model, how do cultural consumption values and green consumption values affect tourists’ willingness to travel to regenerative complex cultural spaces?

What role does the attitude towards participating in regenerative tourism play in this process?

Which factor—(intrinsic) perceived value or (extrinsic) image of the destination city— has a stronger influence on the willingness to travel to the regenerated complex cultural space?

The answers to these questions will provide important theoretical support and practical guidance for government decision-making in urban tourism planning and help achieve more targeted and effective urban revitalization and tourism development strategies.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Theoretical Model

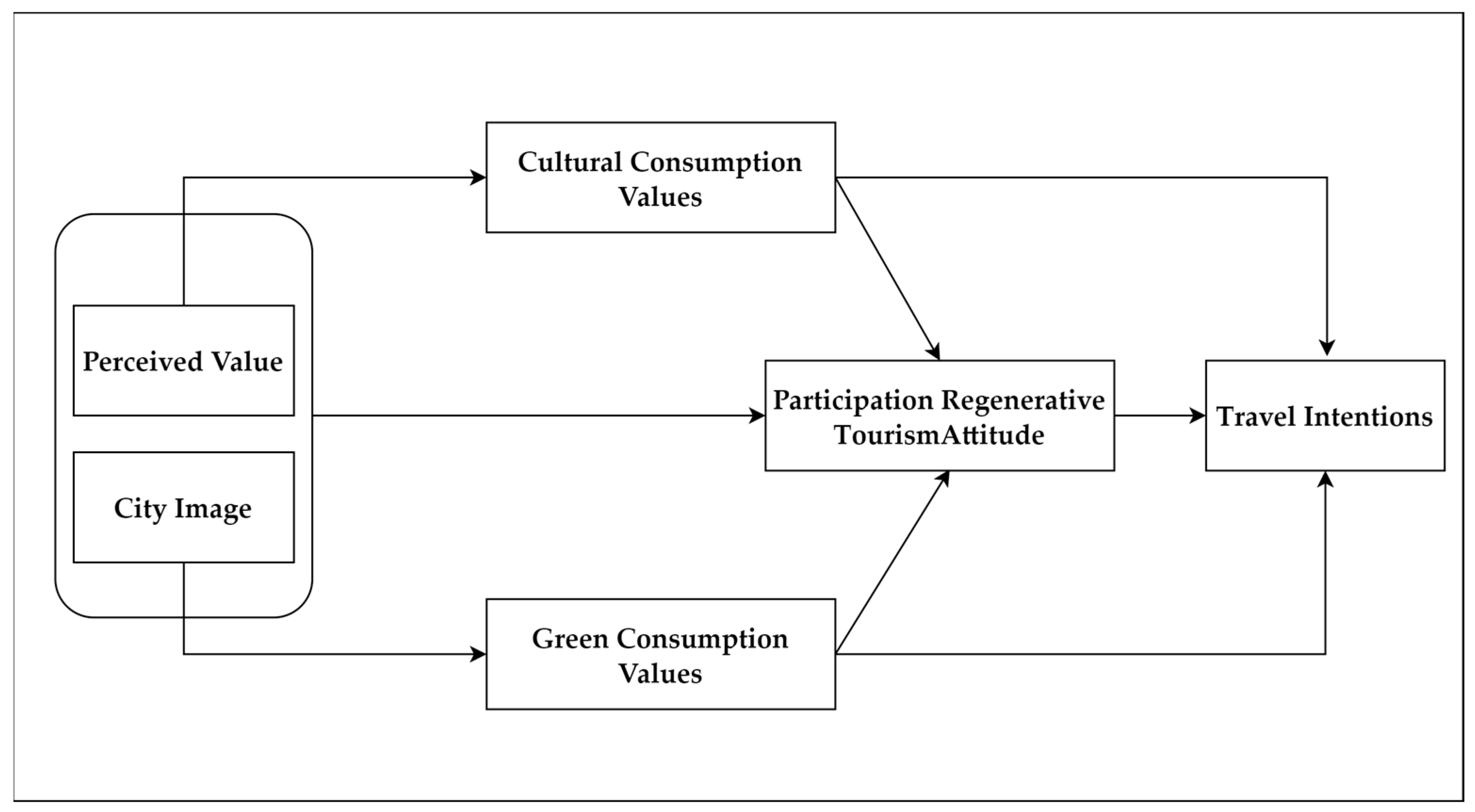

The values–attitudes–behavior (VAB) theory posits that values play an intermediary role in behavioral attitudes and influence specific behaviors, revealing the internal relationship among values, attitudes, and behaviors [

66]. The VAB model is widely used in research, especially in explaining the sustainability of different consumer behaviors, demonstrating strong applicability and explanatory power [

67]. Transitioning to sustainable development requires profound changes in human values, attitudes, and behaviors. Values not only guide individuals to achieve their goals but also shape their attitudes and provide important judgment criteria for evaluating the sustainable development behavior of individuals and society. Hence, values play a central role in driving sustainable development [

68]. However, existing research mostly focuses on the tourism experience stage, exploring the relationship among values, attitudes, and behaviors [

69,

70,

71] while paying scant attention to tourists’ cognitive process in the destination decision-making stage. Compared to post-visit experiences, the decision-making process before tourism plays a more important role in promoting the development of regenerative tourism. Therefore, this study uses the VAB model, combining tourists’ perceived value and city image, and undertakes an in-depth exploration of how their values and attitudes influence the relationship between tourism intention and behavior. Based on this framework, the theoretical model shown in

Figure 1 is developed.

3.2. Background and Questionnaire Survey

According to data from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism of Korea, there are currently 591 urban regeneration projects in progress, with a total investment of 1203.2 billion won. These projects are expected to create 9000 jobs, and this number is growing [

72]. This study focused on Korea.

The questionnaire content of this study is designed based on the existing questionnaire framework in related fields. To ensure the reliability and validity of the questionnaire, we invited seven Korean experts in related fields to engage in in-depth discussions and localize the contents of the questionnaire. On this basis, we carried out a pre-survey to test the applicability and scientificity of the questionnaire. Based on the results of the pre-survey and post-interview feedback, we optimized and improved the language of the questionnaire to improve its localization and descriptive accuracy. Finally, based on the above process, we created a questionnaire scale for six core variables, providing a scientific and effective data collection tool for follow-up research. For a detailed description of the indicators, please refer to the

Table 1.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis Methods

In this study, a mixed online and offline approach was used to collect data to improve the representativeness of the questionnaire. Data collection mainly focused on cities with relatively concentrated regenerated composite cultural spaces in South Korea, including Seoul, Busan, Gwangju, and Jeonju. All respondents had experienced regenerative composite cultural space tourism at least once. To ensure that respondents had a certain understanding of the concept of regenerated cultural space. To improve the data quality, repetitive questions were designed in the questionnaire to identify and exclude questionnaires with inconsistent data. Additionally, the content and format of online and offline questionnaires were standardized to ensure data consistency, thus enhancing the validity of the research results.

Data collection began in March 2025, resulting in a total of 579 questionnaires. After screening and eliminating 112 unreliable questionnaires, 467 valid questionnaires were retained for data analysis. The effective sample size exceeded 10 times the minimum required number of measurement items (26 items), ensuring the robustness and credibility of the data analysis.

This study mainly used SmartPLS for data analysis. SmartPLS can comprehensively evaluate the validity and rationality of all paths in structural equation models. Moreover, SmartPLS has excellent applicability in chain mediation model analysis, helping to clearly clarify the relationship between variables and their mechanism of action, thus improving the scientificity and robustness of model interpretation. Therefore, this study used a combination of SPSS 27 (IBM) and SmartPLS 4 (SmartPLS Executable) for data processing and analysis.

First, a descriptive statistical analysis of the respondents’ demographic characteristics was performed using SPSS 27 to provide sample background information for subsequent studies. Then, SmartPLS 4 was utilized for model evaluation, including analysis of key indicators: Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). Additionally, we tested the research hypothesis using the Bootstrapping algorithm. Moreover, we evaluated the model fit and predictive power using R2 values and Q2 values to ensure the scientific rigor and explanatory power of the research results.

5. Discussion

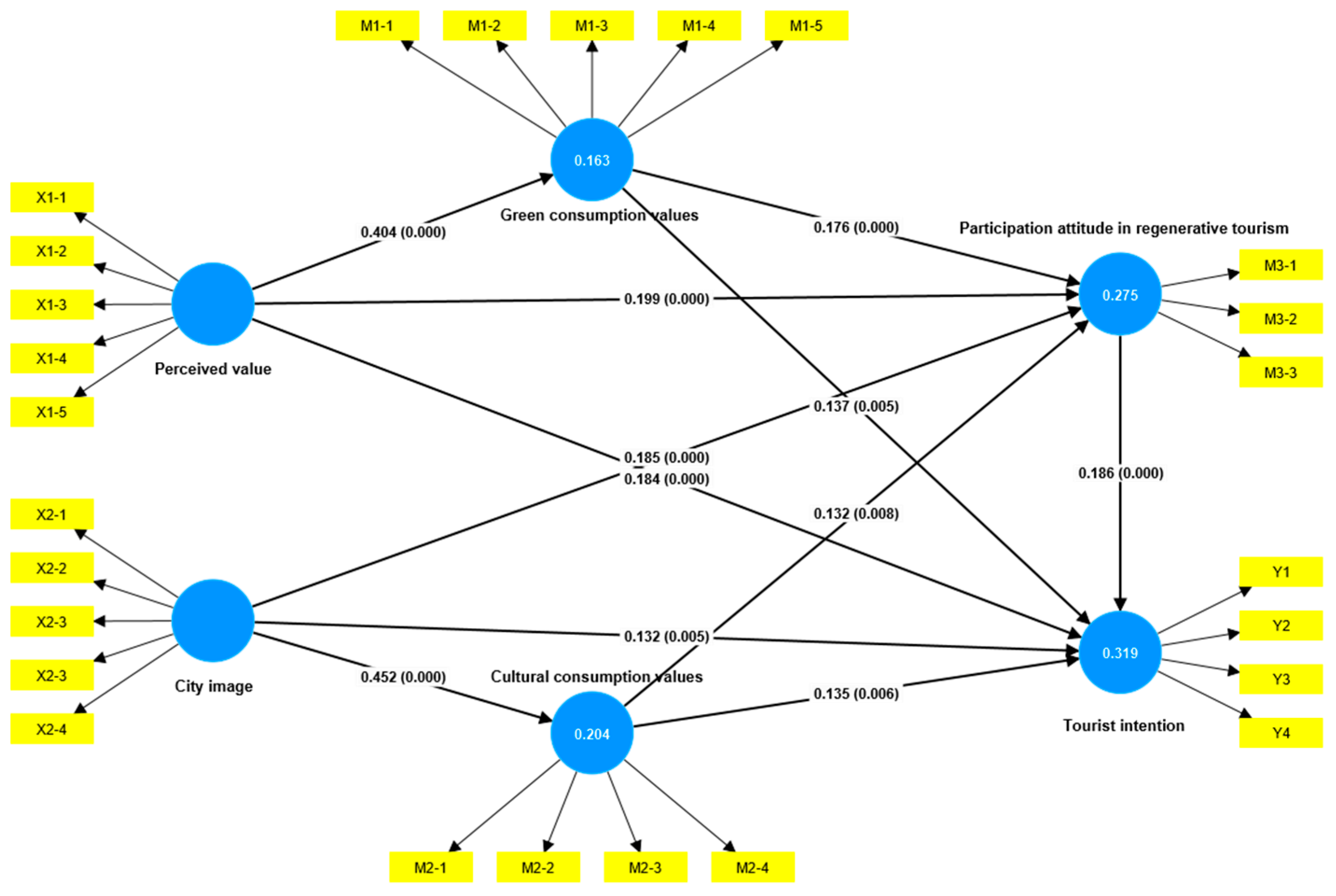

This study explores how tourists’ perceived value of urban image and regenerative complex cultural spaces in cities influences the tourists’ tourism intention in regenerative tourism and analyzes the mediating role of consumption values and participation attitudes in this relationship.

First of all, tourists’ perceived value of city image and regenerative complex cultural space in the city have a positive impact on tourism intention, which is consistent with the conclusions of some related studies [

86,

87,

88,

89]. The remarkable feature of this study lies in the use of dual dimensions to analyze tourists’ tourism motivation. Different from previous studies, this study not only focuses on tourists’ perceived value of regenerative complex cultural space and the overall city image, but also further explores the differentiated influence of macro and micro factors on tourism intention. The results show that the influence intensity of micro-factors (perceived value) on tourism intention is significantly higher than that of macro-factors (city image). This phenomenon may stem from the change of modern tourists’ tourism behavior pattern: compared with the traditional long-term tourism planning based on cities, contemporary tourists are more inclined to choose the form of “micro-tourism” with a strong purpose and short cycle. Therefore, city managers can attract tourists by creating more Internet celebrity attractions. Although such short-term tourism projects may bring a limited single income, they can achieve economies of scale by increasing tourist flow, thus bridging the income gap. However, with the large-scale development of scenic spots for online celebrities, the problem of homogenization has become increasingly prominent, which may weaken the unique attraction of scenic spots. In view of this challenge, this study proposes that in the planning and construction of regenerative complex cultural space, we should pay attention to the deep integration and innovative expression of regional characteristic culture. By creating a space carrier with cultural recognition, it can not only effectively alleviate the phenomenon of homogenization but also enhance the cultural attraction and competitiveness of scenic spots, thus realizing the long-term sustainable development of tourism.

In addition, the results show that tourists’ perceived value of regenerative complex cultural space in the city and the image of the city jointly affect their green consumption values, cultural consumption values, and attitudes towards participating in regenerative tourism. This result verifies the relationship of mutual influence between them and further confirms the association between perceived value and attitude in regenerative tourism [

42,

90]. It is worth noting that this study reveals a phenomenon of theoretical significance: in the relationship between perceived value and city image on green and cultural consumption values and attitudes of participating in regenerative tourism, the influence of perceived value on values is lower than that on attitudes, while the influence of city image on values is higher than that on attitudes. This result not only fills the theoretical gap of previous research but also provides a new research perspective for related fields. We speculate that this phenomenon may be due to the close relationship between tourists’ perceived value and values. In contrast, this closeness makes its influence on values less than on attitudes. This inference is consistent with the views of cognitive dissonance theory [

91]. At the same time, the influence of city image on values is higher than that on attitudes, which may be due to the fact that city image is a more macro evaluation dimension, and its extensiveness and inclusiveness are more conducive to the formation and shaping of values; As a more specific and subjective belief system, attitude has a relatively weak correlation with the macro-scale of city image, so the degree of its influence is correspondingly reduced.

In examining the intermediary relationship between perceived value, green and cultural consumption values, attitude of participating in regenerative tourism, and tourism intention, we find that both single intermediary effect and sequential intermediary effect exert a significant influence. Specifically, in analyzing the intermediary path, the intermediary effect of green consumption values is significantly higher than that of cultural consumption values. This phenomenon has been verified in the following paths: PV → GCV → PRTA, PV → CCV → PRTA, PV → GCV → PRTA → TI, and PV → CCV → PRTA → TI. We hypothesize that this phenomenon may be closely related to the increasing influence of the Internet. The rapid development of the Internet not only accelerates the spread and integration of multiculturalism but also significantly improves tourists’ awareness of cultural values [

92]. However, this extensive information acquisition and cultural contact have also raised tourists’ expectations and standards for cultural experiences. Conversely, since the “Green Economy Blueprint” was published in 1989, the continuous development of green values has covered many fields, and the widespread popularization of the concept of green life has evolved into a social consensus [

93]. With the deepening of public awareness about the importance of sustainable development of the earth, tourists pay more attention to green consumption behavior in the process of tourism decision-making, which gives green consumption values a stronger explanatory power in the intermediary path. In the relationships of PV → GCV → TI, PV → CCV → TI and PV → PRTA → TI, In the relationships of PV → GCV → TI, PV → CCV → TI and PV → PART → TI, the findings are consistent with the prediction that the mediation effect of Participation attitude in regenerative tourism (PART) is significantly higher than that of green consumption values versus cultural consumption values. This finding reinforces the central role of attitude in shaping behavioral intention and provides new empirical support for the application of planned behavior theory in regenerative tourism research.

Concerning the intermediary relationship between city image, green consumption values, and cultural consumption values on the attitude of participating in regenerative tourism and tourism intention, the results show that the intermediary effect of green consumption values is significantly higher than that of cultural consumption values. This result is verified in all intermediary relationships. We believe that city image, as a psychological projection and symbol, reflects the public’s overall perception and impression of a city [

28]. Although the cultural elements contained in the city image usually have distinctive regional characteristics, their influence on tourists may be significantly differentiated due to the differences of individual interests and preferences. Studies show that there is great heterogeneity in tourists’ recognition of specific cultural elements: some tourists may show a high degree of recognition of some cultural symbols, while others may pay less attention to them [

94]. Although the cultural elements contained in the city image usually have distinctive regional characteristics, their influence on tourists may be significantly differentiated due to the differences of individual interests and preferences. Studies show that there is great heterogeneity in tourists’ recognition of specific cultural elements: some tourists may show a high degree of recognition of some cultural symbols, while others may pay less attention to them [

94]. In contrast, a green image has wider universality and attractiveness, and the environmentally friendly concept and sustainable development goal driven by green consumption values are highly consistent with the global ecological consensus. Hence, green consumption values show a more significant mediating effect in influencing tourists’ attitudes and intentions.

The model constructed in this study is of great significance in understanding the rise of regenerative tourism. In essence, this study systematically analyzes the relationship among consumption values, participation attitudes, and tourism intentions by exploring tourists’ perceived value of regenerative complex cultural spaces and the influence of a city’s image on their tourism intentions. This research provides clearer theoretical guidance for policy formulation and urban development planning of regenerative complex cultural spaces and helps to enhance the attractiveness of such spaces, thus realizing the potential of urban regeneration. However, the findings show that although the sequence mediation effect is significant, its path coefficient is relatively small. This phenomenon may be attributed to the fact that tourists are easily influenced by external factors when making travel plans [

95]. For example, tourists often refer to the evaluation of destinations by people around them when making travel plans, but the authenticity and reliability of these evaluations may vary. Although a positive evaluation can theoretically promote the formation of tourism intention, in the current highly developed environment of social media and online marketing, some scenic spots highlighted by online celebrities artificially create a positive evaluation through misleading advertising and data manipulation. This phenomenon may make tourists skeptical, thus weakening their tourism intention.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Significance

This research model systematically analyzes tourists’ behavioral motivation before making decisions about regenerative tourism and improves and expands the values–attitude–behavior model to enhance its applicability and explanatory power in the field of regenerative tourism. The study not only makes important theoretical contributions but also provides scientific guidance for practical management.

Firstly, this study verifies the complex relationship among tourists’ perceived value, city image, green consumption values, cultural consumption values, attitudes toward participating in regenerative tourism, and tourism intention and reveals the interaction mechanisms of these key variables in regenerative tourism behavior decision-making. The study findings provide an in-depth understanding of tourists’ behavior motivation and value orientation and avail important empirical data for regenerative tourism research.

Based on the causal sequence relationship, this study reveals the dynamic interaction mechanism among perceived value, city image, consumption values, and participation attitude. Moreover, the study empirically analyzes the synergistic pathways of these variables in shaping tourism intention, thus deepening the understanding of tourists’ decision-making processes in the context of regenerative tourism. Compared with previous research, this study innovatively constructs a dual value integration analysis framework of green consumption values and cultural consumption values, breaking through the limitations of traditional single-dimensional interpretation. Moreover, from the perspective of micro–macro motivation binary analysis, this study explores the differentiated transmission mechanism of perceived value, city image, and green and cultural consumption values and participation attitudes to tourism willingness. This integrated perspective not only systematically deconstructs the antecedents of tourism intention formation but also addresses the theoretical gap in understanding the synergistic effects of dual consumption values and attitudes in regenerative tourism research. By enriching the theoretical framework related to green and cultural consumption values, this study introduces new theoretical perspectives, which provide strong support for academic research and practical management in regenerative tourism.

Previous studies on regenerative tourism, a new form of tourism, mostly focused on the environmental benefits [

19], economic benefits, and social significance of space reuse; however, there is a research gap on the internal mechanism of tourists’ consumption values driving behavior intention [

11,

96,

97]. By constructing an integrated theoretical framework of green consumption values and cultural consumption values, this study systematically deconstructs the mechanism of tourists’ tourism intention and innovatively introduces the interdisciplinary research paradigm of consumer psychology and behavioral science, which provides a new research perspective for the improvement of regenerative tourism theory.

This study further examines regenerative complex cultural spaces as the core foundation of regenerative tourism, and their essential characteristics are reflected in the dual-dimensional value reconstruction. The creative transformation of abandoned spaces, such as industrial relics and historical buildings, leads to the functional upgrade of physical spaces. Moreover, the innovative integration of local cultural elements and contemporary artistic expression creates a cultural consumption field with the characteristics of time and space dialogue. The production logic of this new tourism space essentially forms a synergistic trinity of economic, cultural, and ecological regeneration. However, the behavioral motivation of tourists in tourism scenes is complex and diverse [

98]. By refining the roles of green and cultural consumption values, this study reveals the different behavioral tendencies formed by tourists when they perceive environmental sustainability and cultural uniqueness and provides a new analysis framework for solving the cultural governance dilemma of urban renewal projects.

Although previous studies have discussed the role of consumption values in commodity consumption or specific types of tourism activities, they have mostly focused on the independent action of a single value, failing to fully reveal the interaction mechanism between multiple values [

99,

100]. Additionally, these studies have been mostly limited to traditional tourism scenes and have paid relatively little attention to emerging tourism forms such as regenerative tourism, which has constrained the theoretical explanatory power of the studies. To bridge this gap, this study systematically investigates regenerative tourism and innovatively constructs a sequence mediation model of green cultural consumption values and attitudes toward participating in regenerative tourism to comprehensively analyze tourists’ behavioral motivation and decision-making mechanism within the complex context of regenerative tourism. Through this analysis, this study further enriches the applicability and explanatory power of consumption value theory in the field of regenerative tourism.

Finally, this study systematically reveals the multi-dimensional demand structure of tourists in the context of regenerative tourism by integrating green consumption values, cultural consumption values, and attitudes toward participating in regenerative tourism [

101]. The results show that tourists’ needs have significant compound characteristics and that tourists pay attention to the sustainability of the ecological environment and the uniqueness of cultural resources and cultural identity. This finding shows that tourists’ tourism decisions are not driven by a single value but rather by the synergy of multidimensional values, which influence their final decisions.

6.2. Practical Significance

This study reveals the synergy between green consumption values and cultural consumption values, demonstrating that tourists exhibit dual value demands, namely, for ecological environmental sustainability and cultural resource uniqueness, when making decisions about regenerative tourism behavior. This finding explains why some urban regeneration tourism projects fail and underscores the importance of paying attention to the complex needs of tourists when planning projects. To avoid a one-dimensional development, a more balanced and comprehensive planning and design should be adopted, which is more attractive to target tourists.

Further, as a unique entity that integrates the reuse of abandoned spaces and multicultural elements, the regenerative compound cultural space embodies the comprehensive effect of economic, cultural, and ecological values. Based on the influence mechanism of green and cultural consumption values on tourists’ behavior revealed in this study, urban planners and developers can comprehensively consider combining ecological protection and cultural inheritance when designing regenerative cultural spaces to meet tourists’ dual needs for green sustainable development and in-depth cultural experience, thus enhancing the attractiveness of regenerative spaces and enhancing tourists’ willingness to participate.

This study offers a theoretical foundation and practical guidance for policy formulation, real-world applications, and academic research in regenerative tourism. Moreover, the study promotes the integration and development of green and cultural tourism while serving as a valuable reference for future tourism operators to design more compelling marketing strategies.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This study provides important theoretical and practical guidance in the field of regenerative tourism, but it also has limitations. Future research can further expand and deepen the scope of this study in many aspects. First, although this study focuses on regenerated complex cultural spaces, it does not fully consider the different effects of different types of regenerative tourism projects on tourist behavior. Each type of regeneration project may involve various cultural and environmental factors, so tourists’ behavioral motivations and values may vary. Therefore, future research can be extended to different types of regeneration tourism projects to further compare their influence pathways on tourists’ behavioral intentions.

Second, the sample used in the study is mainly concentrated in South Korea. Although the sample attempts to provide the broadest regional coverage possible, the sample may still limit the universal applicability of the research results. Therefore, future research should expand the sample size to cover a wider group of tourists, especially those from different cultural backgrounds, countries, or regions to improve the universality of research results. Cross-cultural research can help uncover the differences between tourists’ green and cultural consumption values under different cultural backgrounds and how these differences shape tourism behavior.

Third, this study does not fully consider the possible changes of tourist behavior over time or in response to external factors (such as seasonal changes, fluctuations in economic situations, etc.). Different time nodes and environmental factors may affect tourists’ tourism decisions and behavioral intentions. Therefore, future research can adopt a longitudinal research design to track long-term changes in tourists’ behavior or explore how environmental changes affect the role of green and cultural consumption values in tourism intentions.

The mediating role of participation attitudes is one of the important findings of this study. However, the complexity of this mechanism remains underexplored. Consequently, future research can further refine the constituent factors of participation attitudes, such as emotional identity, social influence, interaction of individual values, etc., and conduct a deep analysis of how these factors play a role in tourists’ decision-making process, thus promoting the formation of tourism intention. Understanding the multi-dimensional composition of participation attitudes will help uncover tourists’ behavioral motivations more accurately.

Additionally, with the progress of science and technology, technologies such as virtual reality, big data, and artificial intelligence are gradually penetrating the tourism industry. Future research can combine these scientific and technological factors to explore tourists’ behavior patterns and decision-making processes in regenerative tourism. For example, virtual tourism experiences can help researchers test tourists’ responses and emotional identity to the regeneration space, and big data analysis can help reveal tourists’ behavioral tendencies driven by green and cultural consumption values. Assessing the role of these technologies will provide more accurate and innovative research tools for future research.