Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted tourism systems worldwide, particularly ecologically sensitive and tourism-dependent regions such as the Galapagos Islands. This study investigated the impact of the pandemic on profiles of tourists visiting Santa Cruz Island by comparing an analysis from 2019 to data we gathered in 2021. Using survey-based data and cluster analysis, we identified significant shifts in tourist origin, travel modalities, and expenditure patterns. Results showed a marked increase in domestic tourism, with Ecuadorians becoming the dominant visitor group during the pandemic, primarily favoring land-based tourism and shorter stays. In contrast, international tourists remained present in niche, higher-spending segments associated with cruise-based and multi-island itineraries. These findings highlight a temporary yet meaningful transformation in the tourism dynamic, driven by changes in risk perception, economic factors, and policy restrictions. The emergence of these segments underscores the need for adaptive destination management strategies that align with sustainability goals, conservation priorities, and socioeconomic resilience. We also demonstrated the value of structured surveys as a cost-effective tool for evidence-based decision-making in resource-constrained settings.

1. Introduction

The Galapagos Islands lie about 1000 km off mainland Ecuador. Despite being located on the northeastern margin of the Southern Tropical Gyre (often considered a marine “desert”), the archipelago has a unique ecosystem and climate shaped by the convergence of several marine current systems [1,2]. In recognition of its unique biodiversity, UNESCO designated the Galapagos Islands as a Natural World Heritage Site in 1978 [3].

Most of the Galapagos Islands are legally protected: 97% of their terrestrial area (7795 km2) and approximately 133,000 km2 of their surrounding marine territory [3]. However, since the 1980s, the archipelago has undergone rapid development driven primarily by tourism, resulting in significant demographic and ecological changes [4]. For example, the number of tourist arrivals surged by 545% between 1989 and 2019, and the resident population increased by 415% between 1982 and 2022 [5,6].

This accelerated growth led to an increase in invasive species, migration, overfishing, and uncontrolled tourism, prompting UNESCO to place the Galapagos on the List of World Heritage in Danger in 2007 [7]. Following this designation, the Ecuadorian government implemented a series of management reforms, which led to the archipelago’s removal from the list in 2010 [8]. Despite these efforts, between 2007 and 2016, there was a notable rise in land-based tourism, diverging from the historically dominant cruise-based model [1,6,9]. This shift in tourist preferences has remained consistent over the last decade, with the exception of a temporary disruption during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In response to the emergence of the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in late 2019 and the subsequent global pandemic, the Ecuadorian government declared a state of health emergency in March 2020 [10]. The pandemic led to a near-total halt in tourism between April and July 2020, with unprecedented and devastating impacts for the local population as well as a change in tourist behaviors and preferences [11,12,13].

Tourism began a slow recovery in August 2020, initially attracting fewer than 1000 visitors per month, but gradually increasing to approximately 6000 by December [14]. By May 2021, monthly tourist arrivals had nearly reached pre-pandemic levels, signaling a rapid rebound. Notably, the composition of visitors changed significantly during this time, with over 60% of tourists in 2021 being domestic travelers, a reversal from historical trends dominated by international tourism [15].

Our study aims to analyze and compare the profiles and preferences of tourists visiting the Galapagos Islands before (2019, data to be reported somewhere else) and during (2021) the COVID-19 pandemic. We seek to provide a data-driven understanding of how global health crises may influence tourism dynamics in ecologically sensitive destinations, offering valuable insights for sustainable tourism planning in the post-pandemic context. These findings can inform more sustainable management strategies in protected areas facing increasing pressure.

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. COVID-19 Pandemic and Tourism

Tourism is highly sensitive to external shocks such as economic downturns, terrorism, and health crises. However, none have matched the scale and global disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic [16,17].

The novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) was first reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) Country Office in Wuhan, China, on 31 December 2019. By mid-March 2020, the virus had spread to 146 countries, prompting the WHO to declare a global pandemic [18]. In response, governments worldwide imposed stringent travel restrictions. By 6 April 2020, 96% of tourist destinations enacted some form of border closure or control, resulting in an unprecedented halt in global tourism [16,19,20].

Unlike previous localized outbreaks, COVID-19 had a worldwide impact across individual, societal, and economic domains [16,17]. Travel restrictions, mandatory quarantines, health testing, and vaccination requirements contributed to the global decline in mobility [16,21,22]. The tourism industry was especially vulnerable, with over 100 million jobs at risk globally due to a 72% decline in international tourism in 2020—a reduction of 1.1 billion travelers compared to 2019. This decline brought tourism back to levels seen 30 years ago [23].

Many tourists either canceled or postponed their travel plans. Older tourists, in particular, expressed greater concern over health risks and demonstrated a lower inclination to travel [22,24,25,26,27]. Travel behavior also shifted toward domestic, nature-based, rural tourism, and road travel [17,28,29,30]. Budget allocations decreased [26], and trips became shorter, covering smaller distances [27,31,32,33]. Preferences also shifted toward sustainability, authenticity, and local experiences [22,24,25,26,27].

In Ecuador, the pandemic exposed the structural fragility of the tourism sector. The country experienced a 70% drop in international arrivals in 2020 compared to 2019, recording only a total of 456,634 international visitors [10,34]. As a consequence, the economic loss was significant, with a drop of around USD 16.38 million from March to December 2020 [35]. In response, the Ecuadorian government implemented support strategies, including tax deferrals and domestic tourism promotion, to help mitigate the impact on tourism businesses [36].

1.1.2. The Effect of COVID-19 on Tourism in Island Destinations

Island destinations are particularly dependent on tourism due to limited economic diversification and natural resource constraints, which make them highly vulnerable to fluctuations in the global tourism market [13,37,38,39].

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, many islands (e.g., Caribbean) experienced rapid growth in tourist arrivals, with some recording double-digit increases, raising concerns about over-tourism in ecologically fragile and protected areas [40,41,42]. The Galapagos Islands were no different, experiencing a 14% rise in tourism in 2018, with more than 280,000 visitors [42,43,44].

However, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic reversed this growth, causing dramatic declines in tourism exports and severely impacting the economic stability of island economies [45]. The extent of the damage varied depending on the degree of tourism dependency. In the case of the Galapagos, tourism accounted for nearly 80% of the economy before the pandemic [4]; hence, the extent of the damage due to the reduced tourism influx for the local economy was extensive [13].

The pandemic led to a complete halt in visitor arrivals for the first time in modern history, being devastating for economies highly dependent on tourism like the Galapagos [13,20,46]. A sociocultural study in the Galapagos assessed the impacts of the pandemic, focusing on local tourism stakeholders’ perceptions (i.e., hotel administrators, tour guides, and residents). The study found that 97% of tourism guides, whose livelihoods depended directly on the industry, reported pandemic-related job losses. However, the adverse effects were not exclusive to the tourism sector, with 56% of non-tourism workers reporting economic decline during the pandemic. This finding suggests a strong indirect dependence on tourism across the broader community [12].

Several strategies were adopted to ameliorate the effects of the pandemic on the tourism sector of the archipelago. To attract tourists, strategies included lodging and service discounts, along with a government call to support domestic tourism. As a result, Ecuadorian visitors (hereafter referred to as domestic visitors in the context of the Galapagos) played a key role in supporting the archipelago’s economy during the pandemic, a trend also observed in other island destinations [25,31,40,47,48].

1.1.3. The Impact of COVID-19 on Tourist Travel Behavior

The COVID-19 pandemic had a major impact on tourism, shaping destination management, the use of protected areas, and tourist experiences and decision-making under uncertainty [24,25,29,31,47,49,50,51,52]. Many destinations were compelled to reassess their tourism strategic approaches by incorporating factors such as health risks, government-imposed travel restrictions, safety protocols, and the need to rebuild trust in the tourism sector. These considerations shaped the development of tailored marketing and recovery strategies, emphasizing clear communication to address traveler concerns and re-engage potential markets [53].

These strategic approaches led to a change in the tourists’ demographics and travel behavior. For example, age emerged as critical in influencing travel behavior during the pandemic. Older adults, due to heightened vulnerability and risk perception, were more likely to postpone or cancel travel and avoid public transport and crowded areas [24,54,55,56]. Changes in travel behavior also included a shift in the travel group composition, with a marked increase in solo travelers seeking nature-based destinations [32,33].

Nature-based destinations and protected areas became more popular during the pandemic, as individuals sought outdoor spaces to maintain physical and mental health [47,57] while avoiding densely populated environments [30,31,57]. Interestingly, traditional motivators such as cultural experiences held less influence during this period. In contrast, health-related concerns, including safety measures and sanitary protocols, became key determinants of tourist satisfaction [28,58,59,60].

Another travel behavior that shifted during the pandemic was a preference for domestic destinations. This global trend was embraced during and shortly after the pandemic, as travel restrictions limited international mobility [28,31,32]. In mainland Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands, domestic tourism played a crucial role in partially offsetting the decline in international visitors, and travel preferences leaned heavily toward open and uncrowded environments [24,25,31].

Cost sensitivity was also a major drive influencing travel behavior during this period of uncertainty. Tourists opted for low-cost destinations, and some travel modalities tailored to visitors with financial means were perceived as unsafe. For example, in the Galapagos, cruise-based tourism declined as it was widely perceived as a high-risk setting for infectious disease transmission due to its enclosed nature [16].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The Galapagos Islands comprise 13 main islands, but only 4 are inhabited. Among them, Santa Cruz Island hosts over 60% of the archipelago’s population (mostly in Puerto Ayora) and serves as a central hub for tourism-related activities [5,6].

We selected Santa Cruz as the study site due to its demographic significance, strategic role in visitor flows, and availability of tourism infrastructure. Because tourism operations are interconnected in the archipelago, and all islands share governance and conservation frameworks, Santa Cruz serves as a representative of broader tourism trends in the Galapagos.

2.2. Surveys

We conducted one structured tourist survey on Santa Cruz Island in 2021. We gathered 383 surveys, targeting a reduced population of about 10,000 monthly visitors. Sample sizes were calculated using a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error, consistent with online sample size estimation tools [61,62].

The questionnaire—available in Spanish, English, and German—consisted of open-ended and closed-ended (multiple-choice) questions. Questions were divided into four sections: (1) sociodemographic profile, (2) trip organization, (3) motivational profile, and (4) perceptions of the destination. The 2021 questionnaire included additional questions related to biosecurity measures, travel adaptations, and health concerns in response to the ongoing pandemic (Table 1).

Table 1.

Topics included in the survey administered to tourists in Puerto Ayora (Santa Cruz Island).

To minimize selection bias, we collected data using random on-site sampling, ensuring that each eligible tourist had an equal chance of participation. Eligible respondents were those 18 years or older who had spent at least two nights in the Galapagos. This criterion aimed to exclude transient visitors less familiar with the destination, improving the reliability of satisfaction and perception responses.

To capture the continuum of travel preferences and allow subsequent comparisons based on sociodemographic characteristics, we grouped the respondents according to their travel modalities. Four modalities were identified: (1) cruise-based, traveling and spending the night exclusively on a vessel; (2) land-based, staying solely in populated centers; (3) island-hopping, moving between islands while spending the night on land; and (4) mixed, combining cruise-based travel with land-based stays.

Our survey was designed to capture deeper insights into visitor motivations, preferences, and experiences. This multidimensional data allowed for robust statistical analysis of trends and differences between the pre-pandemic and post-lockdown recovery tourist cohorts [63]. Part of the pre-pandemic dataset will be published in a separate analysis focusing on tourist profiles and imaginaries in nature-based destinations such as the Galápagos. The present study, however, addresses a different research question by comparing pre-pandemic- and pandemic-period data to examine changes in tourist preferences.

2.3. Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the sociodemographic and travel-related characteristics of the respondents. To identify significant differences between groups (e.g., domestic vs. international visitors; pre-pandemic vs. pandemic period), we employed a suite of inferential statistical tests. Chi-square tests of independence were used for categorical variables (e.g., visitor origin), and t-tests and one-way ANOVA were applied to compare means of continuous variables (e.g., trip budget and length of stay).

Predictors of Travel Modality: To understand the factors predicting the choice of travel modality (cruise-based, land-based, island-hopping, or mixed), we used multinomial logistic regression to model how predictor variables—age, origin, and educational level—influence the probability of selecting each option. Cruise-based itineraries served as the reference category, and each coefficient (β) represents the change in log-odds of choosing a given modality relative to that baseline.

Visitor Segmentation: We used the K-Prototypes algorithm to analyze the dataset, which contains a mix of categorical (e.g., origin, education) and numerical variables (e.g., budget, length of stay). This method is particularly suitable for mixed-type data and allowed us to identify profiles that integrated demographic, economic, and behavioral dimensions simultaneously.

In defining the segmentation criteria, age group and origin were prioritized as core predictors, while education was included to explore its correlation with travel modality. These segmentation outputs were subsequently linked to explanatory models through multinomial logistic regressions, which estimated how changes in predictor variables (e.g., age, education, and per-person budget) influenced the probability of selecting a travel modality (cruise-based, island-hopping, land-based, or mixed) relative to a reference category. Models were implemented using both scikit-learn’s LogisticRegression (multi_class = “multinomial”, solver = “lbfgs”) and statsmodels’ MNLogit, depending on the specific variable of interest. The robustness of results was assessed with standard classification metrics, including confusion matrixes and precision–recall reports. This two-stage approach (unsupervised clustering followed by regression modeling) provided both a descriptive and inferential understanding of visitor profiles, ensuring that segmentation was not only statistically sound but also interpretable for policy and management purposes.

Additionally, we used statsmodels’ MNLogit to run separate multinomial logistic regressions for other categorical outcomes (e.g., perceptions of social life, environmental education, or beach services), with predictors like origin and educational level. The results from MNLogit included coefficient estimates and statistical significance levels, which enabled the interpretation of relationships between explanatory variables and the probability of being in each outcome category.

To examine differences in per-person trip budgets by origin and other grouping factors, we used Welch’s two-sample t-test for two-group comparisons (e.g., domestic vs. international visitors), implemented via scipy.stats.ttest_ind with equal_var = False, which is robust to heteroskedasticity. For comparisons involving three or more groups, we estimated one-way ANOVA models with statsmodels (ordinary least squares with sm.stats.anova_lm, typ = 2), and when omnibus results were significant, we conducted post hoc multiple comparisons using Tukey’s HSD (pairwise_tukeyhsd). These choices follow the analysis pipeline used in the supplementary files and provide inference that is resilient to unequal variances in the two-group case while offering interpretable groupwise contrasts in multi-group settings. Non-parametric alternatives (e.g., Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis) were not employed in our codebase; instead, robustness in two-group comparisons relied on the Welch correction [64].

The data was analyzed using Python (version 3.11), leveraging the scikit-learn and statsmodels libraries for regression and clustering analyses [61,63].

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Profile

The sociodemographic profile of respondents differed significantly notably between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods. In 2019, 25% of respondents (official statistics ~30% [15]) were domestic visitors, whereas in 2021, the number of domestic respondents significantly increased to 57% (official statistics ~60% [15]) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic profile of visitors to Puerto Ayora (Santa Cruz Island). Comparison between 2019 and 2021.

Gender distribution was nearly equal between the two years, and visitors were mostly young. However, the 2019 cohort (29% were aged 26–35) was relatively older than the 2021 visitor cohort (34% were aged 26–35). Educational attainment remained high across both periods, with the majority of respondents holding graduate or postgraduate degrees (Table 2).

3.2. Motivational Profile

Main Reason for Visiting the Galapagos and Visitor Origin

In 2021, motivations differed between international and domestic visitors. Among the international respondents, the leading motivations were wildlife viewing (52%) and the uniqueness of the destination (21%). By contrast, among domestic respondents, motivations were more evenly distributed: wildlife viewing (34%), World Heritage experience (30%), and landscape and scenery (12%). Overall, more than two-fifths of all visitors in 2021 reported a motivation directly linked to the natural environment or outdoor activities, underscoring the prevalence of nature-based values among pandemic-period travelers [40,57].

International visitors selected nature-oriented motivations more frequently than would be expected if origin made no difference (χ2 (21, n = 383) = 99.34, p < 0.001). This finding highlights the role of origin as a key factor shaping why tourists choose to visit the Galapagos, and it is consistent with broader tourism research on the interplay between traveler demographics and destination appeal [25,27,65].

Tourists’ primary motivations for visiting the Galapagos during the pandemic were largely nature-centric. In the 2021 survey, the most cited motivation was observing flora and fauna (42%), followed by experiencing a World Heritage Site (19%), and recognizing the unique character of the destination (14%).

In 2019, foreign visitors emphasized the islands’ ecological and scientific appeal, while domestic visitors expressed a more diverse range of motivations, often highlighting recreational, social, or personal experiences. These differences were found to be statistically significant.

3.3. Perception of the Tourist Destination

3.3.1. The Most Significant Part of the Galapagos Trip

To understand what visitors found most meaningful about their trip, we asked participants to select the three most noteworthy aspects of their Galapagos experience from a list of six options: the places visited, the overall lived experience, knowledge gained, emotions felt, the local population, and the activities undertaken.

In 2021, the most frequently chosen element was the “overall lived experience” (24%), ranking even higher than “places visited” and “activities” (18% combined). This distribution suggests that the experiential dimension of the trip was paramount for visitors. In other words, the immersive experience of being in the Galapagos mattered even more than the specific sites seen.

Differences emerged when analyzing by origin. Among domestic respondents, the top choice was the “overall lived experience” (24%), followed by places visited (22%) and knowledge gained (20%). Among the international respondents, the “overall lived experience” remained dominant (24%); however, secondary preferences leaned toward “activities” (19%) and “emotions” (15%), with “local population” (11%) chosen more often than among domestic visitors. These significant differences (χ2 (5, n = 383) = 12.47, p = 0.029) indicate that while both groups shared the same primary appreciation of the overall lived experience, foreign visitors tended to emphasize active and social aspects (activities, emotions, local population), whereas domestic visitors strongly valued the destination itself and knowledge gained.

In 2019, international tourists most often highlighted “the place visited”, while domestic visitors placed less emphasis on this aspect and instead prioritized more general motivations such as recreation and personal experiences. The 2021 shift toward experience- and activity-centered motivations reveals how pandemic travel restrictions reshaped decision-making processes. As restrictions eased, travelers resumed their journeys with altered priorities, favoring holistic, experiential, and context-driven engagements over purely destination-centric motivations. This shift underlines the dynamic nature of tourist preferences and the need for continuous monitoring in response to global crises and risks such as pandemics, wars, or natural disasters [16,47].

3.3.2. Perceived Values

We asked visitors to list three values they associate with their Galapagos experience. In 2021, the coded results revealed a hierarchy of perceptions. The most frequently mentioned was “security,” (14%), followed by “respect for nature and human beings” (11%), “conservation,” (10%), and “tranquility” (9%). In 2019, “security” (26%), “responsibility” (61%), and “freedom” (6%) consistently emerged as core Galapagos values.

These findings suggest that, even during the pandemic, visitors strongly associated the Galapagos with ideals of personal safety, environmental stewardship, and peace of mind. The recurrence of themes such as safety, responsibility to nature, and a freeing sense of tranquility in both 2019 and 2021 indicates a stable and resilient destination image, persisting even amid the global health crisis. This finding underlines how fundamental these values are in shaping tourists’ experiences and the overall reputation of the Galapagos as a nature-based destination [11].

3.4. Organization of the Trip

3.4.1. Travel Modality, Travel Group, Stay, and Number of Visits

In 2019, island-hopping was predominant among younger visitors, especially in the 26–35 age group, where 72% preferred this travel modality. Cruise-based travel was frequent among older segments, particularly those aged 56–65, where 32% preferred this travel modality. Land-based tourism remained a secondary choice across most age groups.

In contrast, in 2021, the chosen travel modalities were land-based (53%), mixed (21%), island-hopping (18%), and cruise-based (8%), with land-based tourism being the dominant modality across all ages. Cruise-based tourism declined significantly, especially among international visitors, while land-based and island-hopping gained strength, particularly among domestic tourists. This shift reflects changing health concerns, cost sensitivities, and a preference for more flexible, independent travel during the pandemic. Also, during this time, most visitors traveled accompanied by others (90%), with 44% traveling in family groups. This pattern suggests a strong social component in the pandemic period, with families prioritizing shared, immersive travel experiences.

3.4.2. Modality of Travel According to Visitors’ Origin, Age, and Education Level

In 2019, travel modality already showed significant differences by visitor origin (χ2 (3, n = 384) = 27.00, p < 0.001). Domestic tourists concentrated mainly on island-hopping itineraries (52%) and land-based tourism (38%), with cruise-based tourism virtually absent (1%). In contrast, international tourists displayed a more diversified pattern: island-hopping (60%), cruise-based (10%), land-based (17%), and mixed itineraries (5%). In 2021, these differences became even more pronounced (χ2 (3, n = 383) = 90.55, p < 0.001). Domestic tourists shifted strongly toward land-based travel (85%), while international visitors remained more evenly distributed, with higher shares in cruise-based tourism (17%) and mixed modalities (16%). This comparative perspective highlights a pandemic-driven reconfiguration of travel preferences, particularly a strong move toward localized land-based tourism among domestic visitors.

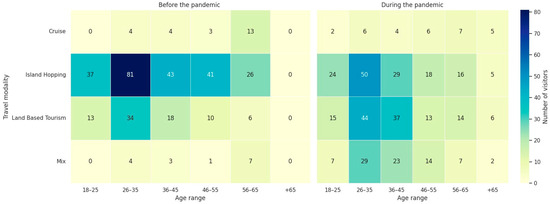

In 2021, travel modality was not independent of age group (χ2 (15, n = 383) = 23.58, p = 0.0088). In 2019, younger tourists (aged 26–35) overwhelmingly favored island-hopping (72%), far surpassing all other age–modality combinations. The cruise-based modality was more common among older segments, especially those aged 56–65 (32%), while land-based tourism remained a secondary choice among most age groups. During the pandemic (2021), land-based tourism became the dominant modality across nearly all age groups. For example, 34% of the 26–35 cohort and 40% of the 36–45 cohort chose land-based tourism. This shift indicates a behavioral transition among younger and middle-aged travelers, who previously preferred mobile formats like island-hopping but during the pandemic opted for more contained and localized experiences. On the other hand, cruise-based tourism declined across all age groups, although it remained slightly higher among older tourists (e.g., 10% of the 56–65 age cohort), likely due to perceived safety and comfort. The preference for mixed modalities increased among the 26–45 age cohorts, with both groups combined representing more than 15% of respondents in these age ranges, suggesting a growing preference for flexible itineraries that combine structured and independent components. In summary, it was a pandemic-induced reconfiguration of travel preferences, with a broader move toward localized, land-based tourism across age groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Travel modality by age before and during the pandemic. The color scale represents frequency (darker = more tourists; lighter = fewer tourists), and the cell values correspond to the number of tourists.

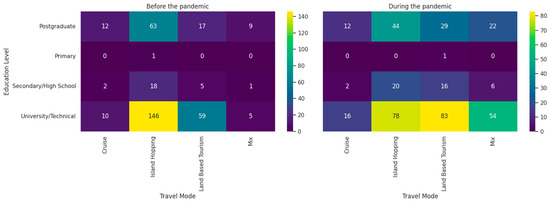

Travelers with higher education showed a broader distribution across travel modalities, while those with lower education levels remained underrepresented before and during the pandemic (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Education level vs. travel modality. The color scale represents frequency (darker = fewer tourists; lighter = more tourists), and the cell values correspond to the number of tourists.

In 2019, respondents with university or technical degrees (57%) showed a strong preference for island-hopping (66%), followed by land-based tourism (27%). Postgraduate visitors (26%) also favored island-hopping (62%), while moderate proportions participated in cruise-based (12%) and mixed travel (9%).

During the pandemic, the pattern shifted. Among university or technical degree holders (60%), 36% chose land-based tourism, 34% selected island-hopping, and 23% opted for mixed travel. Similarly, among postgraduate visitors (28%), 40% chose island-hopping, 27% opted for land-based tourism, and 20% selected mixed travel. The choice for the cruise-based modality among higher-educated groups was similar to what was observed in 2019, around 6.3% for university/technical degree holders and 14.3% for postgraduate visitors.

Our results resonate with the existing literature linking education to greater planning capacity, destination knowledge, and economic flexibility [32]. We observed meaningful contrasts in travel preferences across education levels, such as the stronger participation of university and postgraduate visitors in island-hopping or mixed travel. However, these differences were not statistically significant (χ2 (20, n = 383) = 17.13, p = 0.645).

3.4.3. Tourist Profiles

To capture the evolving heterogeneity of tourist profiles, we conducted a cluster-based segmentation analysis focused on the COVID-19 pandemic period and contrasted it with previously documented pre-pandemic patterns. This comparative perspective reveals a marked transformation in visitor composition. While pre-pandemic segments were predominantly characterized by highly educated international visitors with strong environmental motivations and higher spending capacity, the pandemic-era clusters uncovered a more diversified and cost-conscious landscape.

We observed a marked diversification of tourist segments during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially when contrasted with pre-pandemic profiles. A low-budget domestic segment emerged as the dominant group—Cluster 2 (49% of respondents in 2021)—representing a reversal of the historically foreign-dominated visitor profile observed before 2020. Before the pandemic, domestic tourists represented a smaller share of arrivals (25% of visitors in 2019) and were frequently associated with limited environmental engagement and socially driven motivations. In contrast, during the pandemic, this cluster not only became numerically dominant but also exhibited distinct travel behaviors: the vast majority opted for land-based tourism (85% of Cluster 2), favoring localized and cost-efficient itineraries. Meanwhile, international visitors showed a more even distribution among modalities, with stronger preferences for island-hopping (30%), mixed modalities (25%), and cruise-based travel (17%).

International visitors continued to exhibit the longest stays during the pandemic. For example, Cluster 0 (7% of respondents) comprised mostly international travelers, reporting average stays of 8 days and the highest per-capita budgets (USD 4432 per person). By contrast, Cluster 2 (49% of respondents) comprised mostly domestic visitors, reporting shorter average stays of 5.5 days and lower budgets (USD 830 per person). In the intermediate position were Cluster 1 (26% of respondents, mostly international visitors, with average budgets of around USD 2900 per person) and Cluster 3 (16% of respondents, also predominantly international, with average budgets of around USD 1700 per person).

Although travel restrictions reshaped the overall volume and profile of visitors, core economic distinctions remained evident, underscoring both the resilience of historical tourism structures and the emergence of new preference trends driven by health concerns, distance constraints, and evolving preferences for flexibility and independence [27,55].

3.5. Cluster-Based Segmentation of Tourists During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Based on the elbow method, the optimal number of clusters was determined at k = 4, where the cost reduction curve leveled off (from 87 million at k = 2 to 19 million at k = 4). This balance between interpretability and granularity led to the adoption of Model G, which captures the multidimensional heterogeneity of post-COVID-19 visitors.

In pre-pandemic segmentation models, three broad profiles were identified based on visitors’ environmental connection or their modes of experiencing nature: solid, mild, and little interest in nature. In contrast, our 2021 model revealed a more behaviorally and economically segmented structure with clusters that differed not only in size but also in travel behavior, spending capacity, and origin composition.

In 2021, Cluster 2 comprised 49% of respondents, predominantly domestic visitors, characterized by shorter stays (5.6 days on average), low per-capita budgets (USD 830), and a preference for land-based tourism. Cluster 3 accounted for 16% of respondents, mainly international visitors, reporting stays of 7.3 days, average budgets of USD 1700, and a tendency toward island-hopping itineraries. Cluster 0, comprising 7% of respondents, also included mostly international visitors, associated with the highest budgets (USD 4432), the longest stays (8.0 days), and island-hopping as the dominant travel modality. Finally, Cluster 1 represented 26% of respondents, again predominantly international, with intermediate stays (7.3 days), mid-range budgets (USD 2900), and a preference for mixed travel modalities. These segments span the full spectrum of tourist types, ranging from low-budget, short-stay, domestic tourists (Cluster 2) to high-spending, long-stay, foreign visitors (Cluster 0).

This distribution reflects a fundamental shift in segmentation logic between 2019 and 2021, with the pre-pandemic clusters primarily organized around motivational or environmental interests. In contrast, the post-pandemic structure integrates behavioral, economic, and demographic dimensions, offering a more nuanced and comprehensive typology of visitors to the Galapagos.

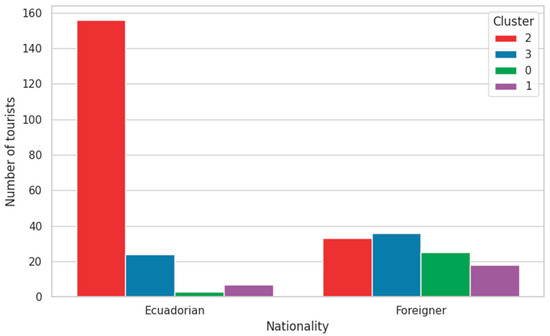

3.5.1. Composition and Demographic Shift

In 2021, clusters differed in their composition of visitors by origin. For example, 71% of domestic tourists belonged to Cluster 2, while smaller proportions were distributed across Cluster 3 (11%), Cluster 1 (3%), and Cluster 0 (1%). In contrast, the distribution of foreign tourists was more balanced across clusters: Cluster 2 (20%), Cluster 3 (22%), Cluster 0 (17%), and Cluster 1 (10%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Tourist nationality distribution by cluster, 2021 survey.

This composition underscores the predominance of a low-budget domestic segment during the pandemic, contrasting with the more evenly distributed international visitors. This transition reflects a structural change from the pre-pandemic, motivation-centered typology to a multidimensional, data-driven segmentation, integrating demographic, behavioral, and economic factors into the analysis.

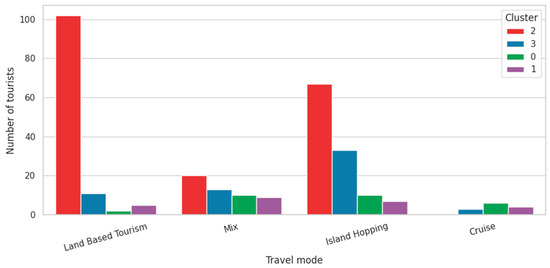

3.5.2. Travel Modality and Origin

Differences in travel modality further reinforced the segmentation observed during the pandemic. Most visitors in Cluster 2 (49% of the total sample) corresponded to the low-budget domestic group, who primarily selected land-based tourism (54%), followed by island-hopping (35%), mixed travel (11%), and cruise-based (1%) (Figure 4). This pattern indicates that the majority of low-budget domestic tourists favored short, localized trips that minimized both cost and logistical complexity.

Figure 4.

Travel modality preferences by cluster, highlighting localized travel among national tourists.

On the other hand, Cluster 3 (16% of the total sample) comprised mostly international tourists, who primarily selected island-hopping (53%), followed by mixed travel (23%), land-based (20%), and cruise-based (3%) tourism. Similarly, Cluster 0 (7% of the total sample) represented international visitors, distributed more evenly, who favored island-hopping (39%), followed by land-based (29%), mixed travel (25%), and cruise-based (7%) tourism. This pattern contrasts sharply with pre-pandemic behavior, when foreign visitors, especially those with strong environmental motivations, often engaged in broader itineraries involving cruise-based travel or island-hopping, which allowed for greater ecological immersion. Finally, Cluster 1 (26% of the total sample) comprised predominantly international visitors, displaying a balanced participation across modalities: mixed travel (36%), island-hopping (24%), land-based (20%), and cruise-based (20%).

This behavioral distinction underscores a persistent correlation between economic capacity and spatial tourism behavior, where higher-income tourists (Clusters 0 and 3) continued to seek expansive formats such as island-hopping or mixed modalities, and domestic visitors (Cluster 2) gravitated toward simplified, cost-contained modalities aligned with affordability.

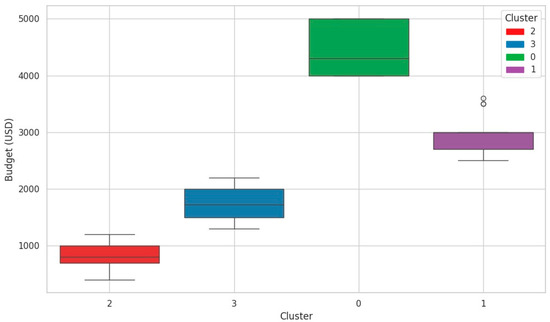

3.5.3. Spending Profiles and Economic Segmentation

Spending behavior serves as another key differentiator among the clusters identified during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourists in Cluster 0 (7% of respondents) reported the highest individual budgets per person, averaging USD 4432 (USD 4000–5000), followed by Cluster 1 (6%), averaging USD 2914 (USD 2500–3500), and Cluster 3 (16%), averaging USD 1738 (USD 1300–2200). In contrast, Cluster 2 (49%), which comprised the low-budget domestic group, reported the lowest travel budgets per person, averaging USD 830 (USD 400–1200) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Per-capita trip budget by cluster. Circles represent outliers automatically detected by the boxplot.

This distribution reveals a clear economic stratification across tourist segments, consistent with patterns observed before the pandemic. Historically, higher-spending foreign tourists dominated the cruise-based and island-hopping markets, while low-spending domestic visitors (fewer at the time) dominated the land-based market. The persistence of this pattern, even amid pandemic-driven shifts in mobility and demand, suggests both a degree of structural continuity and the emergence of new economic configurations within the Galapagos tourism landscape.

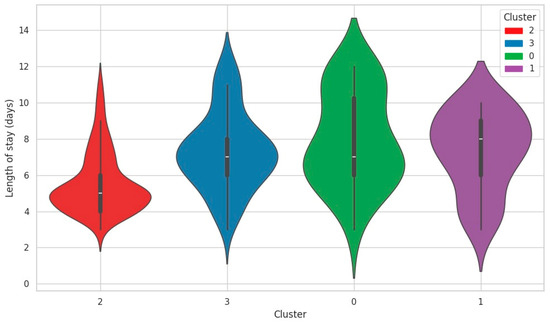

3.5.4. Duration of Stay and Visit Dynamics

Trip duration also varied significantly by segment, with a clear association between budget and length of stay. Cluster 0 (7% of respondents) comprised the highest-spending group, with the longest stays, averaging 8.1 days (6–11 days). Cluster 1 (6%) also showed extended visits, averaging 8.6 days (6–10 days). In contrast, Cluster 2 (49%), the low-budget domestic segment, had the shortest stays, averaging 5.4 days (4–6 days), consistent with their cost-sensitive travel behavior. Cluster 3 (16%) occupied an intermediate position, with an average of 6.9 days (5–9 days), showing more flexibility than Cluster 2 but shorter durations than the higher-spending groups (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Average length of stay by cluster, confirming the connection between visit duration and expenditure. The width of each violin represents the density of tourists at a given length, with wider sections showing higher concentration of visitors.

These findings reinforce a well-documented linkage between financial capacity and travel flexibility, which persisted under the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. The consistency of this pattern highlights how economic resources continue to shape the temporal dimension of travel, despite broader shifts in demand and mobility.

Taken together, it becomes evident that the COVID-19 pandemic not only reduced the overall volume of tourism in the Galapagos but also profoundly reshaped its internal composition. The emergence of a dominant domestic segment, represented by nearly half of the sample (Cluster 2), shows both a structural adjustment and a behavioral adaptation to global uncertainty and restricted mobility. In contrast, high-spending foreign visitors persisted, albeit concentrated in smaller, more clearly defined clusters (Clusters 0 and 1), highlighting the resilience of international demand, more selective and economically stratified during the COVID-19 pandemic.

4. Discussion

This study compared tourist profiles on Santa Cruz Island, Galapagos, before (2019) and during (2021) the COVID-19 pandemic, and found significant shifts in tourist origin, travel modality, and expenditure.

Visitor composition shifted from predominantly international in 2019 to predominantly domestic in 2021. This transition reflects structural disruptions caused by global mobility restrictions and behavioral responses to risk and affordability during the pandemic [16,24,25,29,31].

Notably, in 2021, both international and domestic tourists predominantly chose land-based travel, while cruise tourism saw significantly lower participation among international visitors. This shift was largely due to the widespread perception of cruises as high-risk environments for COVID-19 transmission [16]. However, domestic tourists outnumbered international tourists, a shift from pre-pandemic patterns [15]. A key enabling factor for this domestic surge was a sharp drop in accommodation prices (e.g., ~50% discount and last-minute prices), which made the destination more accessible to middle- and lower-income domestic travelers [36]. These patterns underscore the importance of understanding the socioeconomic elasticity of tourism demand in crisis contexts [53]. Moreover, promoting domestic tourism can enhance the resilience of the tourism sector by simultaneously creating economic opportunities for local communities and supporting the conservation of natural heritage, which forms the principles of tourism activities in the Galapagos [4,13]

Cluster analysis further refined this understanding by identifying four distinct post-pandemic tourist profiles in 2021. Of them, the largest segment, composed mainly of domestic travelers, was defined by limited budgets, short stays, and localized travel within Santa Cruz Island. The second most relevant segment, composed mainly of international tourists, was defined by high spending, longer stays, and multi-island itineraries. This segmentation based on socioeconomic and behavioral variables during the pandemic contrasts with a 2019 study, where the cluster analysis was mainly driven by environmental motivations, such as interest in nature-based experiences.

Our findings point to a temporary yet meaningful reconfiguration of the tourism dynamic in the Galapagos. Whereas in 2019 domestic tourists represented only about one-quarter of all visitors (~24%), during the pandemic in 2021, they made up more than half (~57%), playing a vital role in economic recovery. In contrast, international visitors remained active in more stratified, niche market segments. This evolution highlights the need for adaptive tourism management strategies that are capable of responding to emerging visitor profiles while balancing economic recovery with the long-term goals of sustainability and conservation [16,32]. Moreover, the results also coincide with the global shift toward a preference for domestic, nature-based tourism [28,29,57].

The observed demographic and behavioral shifts may also have implications for environmental planning and conservation. Prior research suggests that shorter visits driven by recreation, rather than environmental education, may result in weaker engagement with conservation goals. Increases in younger visitors and short-stay domestic travelers could also increase the pressures placed on protected areas. However, during global crises, younger, well-educated travelers tend to exhibit higher levels of adaptability and resilience [20,66]

Demographic and psychographic attributes significantly shape tourist decision-making and preferences, especially under conditions of uncertainty or risk [51,56]. Preferences for open spaces and nearby locations, along with factors such as age and spending capacity, also shaped travel behavior during the pandemic [27,47,65,67]. Although this is not a longitudinal study, which can be considered a limitation, it effectively illustrates the differences in visitor profiles before and during the pandemic.

Finally, this research reinforces the value of face-to-face survey-based data collection in resource-constrained settings. Structured questionnaires proved to be a cost-effective and reliable method for capturing large, diverse samples that support robust statistical analysis and inform policymaking [68]. Unlike studies relying on online questionnaires or social media data—often limited by sampling bias or insufficient context—our research provides a grounded and representative snapshot of tourist preferences.

By capturing data before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study offers valuable insights for a sensitive and highly regulated destination like the Galapagos. Integrating demographic factors (i.e., age, origin, and travel purpose) into destination planning will allow the development of strategies that are not only responsive to market changes but also aligned with principles of sustainability, equity, and long-term resilience.

5. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study contributes to the growing body of literature on tourism resilience and adaptation by offering empirical evidence on how global crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, reshape tourist behavior in ecologically sensitive destinations. By applying cluster-based segmentation to pre- and post-pandemic data, the research extends theoretical understandings of travel preferences under conditions of uncertainty and risk. The findings reinforce the relevance of sociodemographic and motivational variables in tourism segmentation, while also highlighting the dynamic nature of these factors in response to external shocks. Moreover, this study advances discussions in sustainable tourism theory by linking visitor travel patterns to broader sustainability challenges, such as ecological, social, and psychographic carrying capacity, equity in tourism access, and destination stewardship and conservation.

From a policy and management perspective, the results offer actionable insights for tourism planners and stakeholders in the Galápagos and other protected areas. The documented rise in short-stay, domestic tourists points to a shift in market composition that requires adjustments in infrastructure, services, and marketing strategies. Tourism managers must consider how to engage this emerging visitor profile in conservation goals while mitigating pressures on fragile ecosystems. Additionally, the use of cost-effective survey methods provides a practical tool for ongoing visitor monitoring, especially in resource-constrained contexts. This study underscores the need for adaptive, data-informed decision-making frameworks that balance tourism recovery with long-term environmental and community well-being—critical considerations not only for the Galápagos but for other destinations facing increasing vulnerability to pandemics, climate change, and geopolitical instability.

6. Limitations and Future Research

While this study offers valuable insights into the changing dynamics of tourism in the Galapagos Islands in the context of a global crisis, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the data is geographically limited to Santa Cruz Island, which, although central to Galapagos tourism, may not fully represent patterns across the entire archipelago. Future research should include a broader spatial scope to capture inter-island variations in tourist preferences.

Second, the use of self-reported survey data introduces potential biases related to recall accuracy and respondent subjectivity. Incorporating complementary methods, such as observational studies, transactional data analysis, or qualitative interviews with different stakeholders, could enhance the robustness of future findings.

Third, this study offers a temporal snapshot of pre- and immediate post-pandemic tourism. As travel dynamics continue to evolve in response to shifting global conditions, longitudinal studies are needed to assess the persistence or transformation of observed trends over time.

Finally, while cluster-based segmentation proved useful in identifying emerging tourist profiles, future research could explore more advanced data analytics, including machine learning techniques, to refine visitor classification and prediction models. Additional emphasis on equity, access, and community perspectives—especially from local residents and service providers—would also enrich the understanding of tourism’s broader socioecological implications.

7. Conclusions

This study contributes to a deeper understanding of how global crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, can rapidly reshape tourism dynamics in ecologically sensitive destinations like the Galapagos Islands. By comparing pre- and post-pandemic tourist profiles on Santa Cruz Island, we found significant demographic and behavioral shifts, particularly a rise in domestic tourism, changes in travel modalities, and variations in spending patterns. The application of cluster-based segmentation provided valuable insights into emerging visitor types, offering a nuanced view of how socioeconomic and motivational factors influence travel behavior under conditions of uncertainty. These findings underscore the importance of flexible and adaptive tourism management strategies that can respond to shifting market realities while supporting both economic recovery and environmental stewardship.

From a sustainability perspective, the implications are multifaceted. The increasing presence of younger, short-stay domestic tourists introduces new challenges and opportunities for conservation planning, especially in terms of aligning recreational use with ecological protection. Our research highlights the need for continued monitoring of tourist segments to inform targeted policy interventions and destination planning that balance economic development with long-term sustainability goals. Moreover, our study demonstrates the utility of cost-effective, survey-based methodologies in generating evidence-based insights for decision-makers operating in resource-limited settings. As global tourism continues to face risks from pandemics, geopolitical instability, and climate change, the lessons from the Galapagos emphasize the need for resilient, data-informed, and equity-driven approaches to sustainable tourism development.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17188302/s1, dateset.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.-B. and A.Ö.; methodology, A.M.-B., K.R. and A.Ö.; software, K.R. and E.D.A.; validation, K.R., E.D.A. and A.M.-B.; formal analysis, K.R. and E.D.A.; investigation, A.M.-B. and A.Ö.; resources, A.M.-B.; data curation, K.R. and E.D.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.-B. and A.Ö.; writing—review and editing, A.M.-B., A.Ö., K.R. and E.D.A.; visualization, K.R.; supervision, A.M.-B.; project administration, A.M.-B.; funding acquisition, A.M.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Direction of the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Grant number 121-UIO-2019) and the Charles Darwin Foundation for Galapagos (Contribution No. 2520). The APC was funded by Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, PUCE, Codes CEI-EO-01-2021, approved 20 January 2021, and CEI-25-2018, approved 15 January 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in [Zenodo] [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16424378].

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all survey participants for their time and willingness to contribute to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grenier, C. Conservación Contra Natura. Las Islas Galápagos; Abya-Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 2002; ISBN 978-9978-22-654-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación Charles Darwin (FCD); WWF-Ecuador. Atlas de Galápagos: Especies Nativas e Invasoras Galápagos Atlas de Ecuador; Fundación Charles Darwin (FCD): Galapagos, Ecuador; WWF-Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2018; ISBN 978-9978-353-94-3. [Google Scholar]

- DPNG. Plan de Manejo de Las Áreas Protegidas de Galápagos Para El Buen Vivir; Ministry of Environment of Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzitutti, F.; Walsh, S.J.; Rindfuss, R.R.; Gunter, R.; Quiroga, D.; Tippett, R.; Mena, C.F. Scenario Planning for Tourism Management: A Participatory and System Dynamics Model Applied to the Galapagos Islands of Ecuador. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1117–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEC. Presentación de Resultados Nacionales. Available online: https://www.censoecuador.gob.ec/# (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Dirección del Parque Nacional Galápagos; Observatorio de Turismo de Galápagos. Informe Anual de Visitantes a Las Áreas Protegidas de Galápagos; Parque Nacional Galápagos & MINTUR: Quito, Ecuador, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Islas Galápagos Entran a Lista de Patrimonio Mundial En Peligro. Available online: https://news.un.org/es/story/2007/06/1107101 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- IUCN. Galápagos Fuera de La Lista En Peligro. Available online: https://iucn.org/es/content/galapagos-fuera-de-la-lista-en-peligro (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Epler, B. Turismo, Economía, Crecimiento Poblacional y Conservación En Galápagos; Fundación Charles Darwin: Puerto Ayora, Ecuador, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Llugsha, V. Turismo y Desarrollo Desde Un Enfoque Territorial y El COVID-19; CONGOPE: Ediciones Abya Yala: Incidencia Pública Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2021; ISBN 978-9942-09-753-8. [Google Scholar]

- Schep, S.W.; Reusen, M.; Luján Gallegos, V.; van Beukering, P.; Botzen, W. Does Tourism Growth in the Galapagos Islands Contribute to Sustainable Economic Development? The Tourism Value of Ecosystems in the Galapagos and a Cost-Benefit Analysis of Tourism Growth Scenarios; Institute for Environmental Studies: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Varga, P.; Muñoz-Barriga, A. The Broken Golden Egg of the Galápagos: Mistrust and Short Sightedness in the UNESCO World Heritage Site. In Proceedings of the EuroCHRIE 2024 Conference: Building Bridges and Overcoming Challenges, Doha, Qatar, 5–7 November 2024; pp. 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Burbano, D.V.; Valdivieso, J.C.; Izurieta, J.C.; Meredith, T.C.; Ferri, D.Q. “Rethink and Reset” Tourism in the Galapagos Islands: Stakeholders’ Views on the Sustainability of Tourism Development. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2022, 3, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirección del Parque Nacional Galápagos. Informe Anual de Visitantes a Las Áreas Protegidas de Galápagos del Año 2020; Dirección del Parque Nacional Galápagos: Puerto Ayora, Ecuador, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Observatorio de Turismo de Galápagos. Arribos Anuales. Available online: https://www.observatoriogalapagos.gob.ec/arribos-anuales (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, Tourism and Global Change: A Rapid Assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škare, M.; Soriano, D.R.; Porada-Rochoń, M. Impact of COVID-19 on the Travel and Tourism Industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 163, 120469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Pei, S.; Chen, B.; Song, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yang, W.; Shaman, J. Substantial Undocumented Infection Facilitates the Rapid Dissemination of Novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). Science 2020, 368, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Respuesta a La COVID-19: El 96 % de Los Destinos Del Mundo Impone Restricciones a Los Viajes, Informa La OMT; The United Nations World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Couto, G.; Castanho, R.A.; Pimentel, P.; Carvalho, C.; Sousa, Á.; Santos, C. The Impacts of COVID-19 Crisis over the Tourism Expectations of the Azores Archipelago Residents. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utkarsh; Sigala, M. A Bibliometric Review of Research on COVID-19 and Tourism: Reflections for Moving Forward. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Tourism. Impact Assessment of the COVID-19 Outbreak on International Tourism. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/impact-assessment-of-the-covid-19-outbreak-on-international-tourism (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- UN Tourism. Tourism Back to 1990 Levels as Arrivals Fall by More than 70%. Available online: https://unwto-web.leman.un-icc.cloud/news/tourism-back-to-1990-levels-as-arrivals-fall-by-more-than-70 (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Abdullah, M.; Dias, C.; Muley, D.; Shahin, M. Exploring the Impacts of COVID-19 on Travel Behavior and Mode Preferences. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 8, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardt, D.; Glückstad, F.K. A Social Media Analysis of Travel Preferences and Attitudes, before and during Covid-19. Tour. Manag. 2024, 100, 104821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, N. COVID19: Holiday Intentions during a Pandemic. Tour. Manag. 2021, 84, 104287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orden-Mejía, M.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Huertas, A.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Landeta-Bejarano, N.; Carvache-Franco, O. Post-COVID-19 Tourists’ Preferences, Attitudes and Travel Expectations: A Study in Guayaquil, Ecuador. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Hu, F.; Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Innes, J.L.; Xie, Y.; Wang, G. Visitor Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions in Nature-Based Tourism during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study from Zhangjiajie National Forest Park, China. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2022, 10, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaire, J.A.; Galí, N.; Camprubi, R. Empty Summer: International Tourist Behavior in Spain during COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.P.; Guedes, A.; Bento, R. Rural Tourism Recovery between Two COVID-19 Waves: The Case of Portugal. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Shao, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Z. Impacts of COVID-19 on Chinese Nationals’ Tourism Preferences. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desculțu Grigore, M.-I.; Niță, A.; Drăguleasa, I.-A.; Mazilu, M. Geotourism, a New Perspective of Post-COVID-19-Pandemic Relaunch through Travel Agencies—Case Study: Bucegi Natural Park, Romania. Sustainability 2024, 16, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. Use and Experience of Tourism Green Spaces in Ishigaki City before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic Based on Web Review Data. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Turismo. Rendición de Cuentas. 2020. Available online: https://www.turismo.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Informe-de-Rendicio%CC%81n-de-Cuentas-2020.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Banco Central del Ecuador. La Pandemia Incidió En El Crecimiento 2020: La Economía Ecuatoriana Decreció 7,8%. Available online: https://www.bce.fin.ec/la-pandemia-incidio-en-el-crecimiento-2020-la-economia-ecuatoriana-decrecio-7-8/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Ministerio de Turismo. Plan de Reactivación Turística 2020; Ministerio de Turismo: Quito, Ecuador, 2020; pp. 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, S. The Economic Impact of Tourism in SIDS. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Momsen, J.H. Tourism and Poverty Reduction: Issues for Small Island States. Tour. Geogr. 2008, 10, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, E.B.; Rotarou, E.S. Island Tourism-Based Sustainable Development at a Crossroads: Facing the Challenges of the Covid-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, M.; Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Waage, E.R.H. A Break from Overtourism: Domestic Tourists Reclaiming Nature during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 788–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Cheer, J.M.; Novelli, M. Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pecot, M.; Ricaurte-Quijano, C. “¿Todos a Galápagos?” Overtourism in Wilderness Areas of the Global South. In Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2019; pp. 70–85. [Google Scholar]

- Dirección del Parque Nacional Galápagos. Informe Anual Visitantes a Las Áreas Protegidas de Galápagos del Año 2021; Dirección del Parque Nacional Galápagos: Puerto Ayora, Ecuador, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, C.A. The Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. In Overtourism: Lessons for a Better Future; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Policy Brief: COVID-19 and Transforming Tourism. 2020. Available online: https://doi.org/10.18111/wtobarometereng (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Muñoz, A.; Varga, P. Postcards from the Galapagos Islands: Do the Fittest Really Survive? EHL Hospitality Business School: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, M.D.; Lynch, M.L.; Evensen, D.; Ferguson, L.A.; Barcelona, R.; Giles, G.; Leberman, M. The Nature of the Pandemic: Exploring the Negative Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic upon Recreation Visitor Behaviors and Experiences in Parks and Protected Areas. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 41, 100498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, M.; Ali, N.; Hussain, S.A.; Aslam, A.B.; Javid, M.A. Measuring Changes in Travel Behavior Pattern Due to COVID-19 in a Developing Country: A Case Study of Pakistan. Transp. Policy 2021, 108, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Z.D.; Freimund, W.; Dalenberg, D.; Vega, M. Observing COVID-19 Related Behaviors in a High Visitor Use Area of Arches National Park. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, I.; Velasquez, E.; Norman, P.; Pickering, C. Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Popularity of Protected Areas for Mountain Biking and Hiking in Australia: Insights from Volunteered Geographic Information. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 41, 100588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbulú, I.; Razumova, M.; Rey-Maquieira, J.; Sastre, F. Measuring Risks and Vulnerability of Tourism to the COVID-19 Crisis in the Context of Extreme Uncertainty: The Case of the Balearic Islands. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.X.; Rickly, J.M. A Review of Early COVID-19 Research in Tourism: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research’s Curated Collection on Coronavirus and Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 91, 103313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, M.; Seyfi, S. COVID-19 Pandemic, Tourism and Degrowth. In Degrowth and Tourism. New Perspectives on Tourism Entrepreneurship, Destinations and Policy; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; pp. 220–238. [Google Scholar]

- Cahyanto, I.; Wiblishauser, M.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Schroeder, A. The Dynamics of Travel Avoidance: The Case of Ebola in the U.S. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čaušević, A. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Travel Behavior and Travel Mode Preferences: The Example of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, K.; Larsen, S. Pre- and Post-Pandemic Risk Perceptions and Worries. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1412252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venter, Z.S.; Barton, D.N.; Gundersen, V.; Figari, H.; Nowell, M.S. Back to Nature: Norwegians Sustain Increased Recreational Use of Urban Green Space Months after the COVID-19 Outbreak. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štumpf, P.; Kubalová, T. Tangible or Intangible Satisfiers? Comparative Study of Visitor Satisfaction in a Nature-Based Tourism Destination in the Pre- and during-COVID Pandemic. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 46, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, I.; Miravet, D.; Gutiérrez, A. Tourist Satisfaction during the Pandemic: An Analysis of the Effects of Measures to Prevent COVID-19 in a Mediterranean Costal Destination. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2022, 45, 1706–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humagain, P.; Singleton, P.A. Examining Relationships between COVID-19 Destination Practices, Value, Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions for Tourists’ Outdoor Recreation Trips. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 22, 100665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanadesikan, R. Methods for Statistical Data Analysis of Multivariate Observations; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-471-16119-6. [Google Scholar]

- Perneger, T.V.; Courvoisier, D.S.; Hudelson, P.M.; Gayet-Ageron, A. Sample Size for Pre-Tests of Questionnaires. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.M.F. The Foundations of Survey Sampling: A Review. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Gen. 1976, 139, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabold, S.; Perktold, J. Statsmodels: Econometric and Statistical Modeling with Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; pp. 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Hernández-Lara, A.B.; Hassan, T.; Carvache-Franco, O. The Cognitive and Conative Image in Insular Marine Protected Areas: A Study from Galapagos, Ecuador. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 47, 100793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntounis, N.; Parker, C.; Skinner, H.; Steadman, C.; Warnaby, G. Tourism and Hospitality Industry Resilience during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Evidence from England. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Pérez, F.M.; García-González, C.G.; Fyall, A.; Fu, X.; Deel, G.; Fernandez-Hdez, C. The Altered Perceptions of Visitors to National Parks: A Comparison between a Pre- and Post-Covid-19 Periods. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 11, 101219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, R.M.; Lyberg, L. Total Survey Error: Past, Present, and Future. Public Opin. Q. 2010, 74, 849–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).