Analysis of Factors Influencing the Formation of Bioregions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Data Sources

2.2. Selection of Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Testing Normality and Correlations

2.3.2. Factor Analysis

- -

- Factor 1: Sustainable agriculture

- -

- Factor 2: Intensive agriculture

- -

- Factor 3: Tourism and service potential

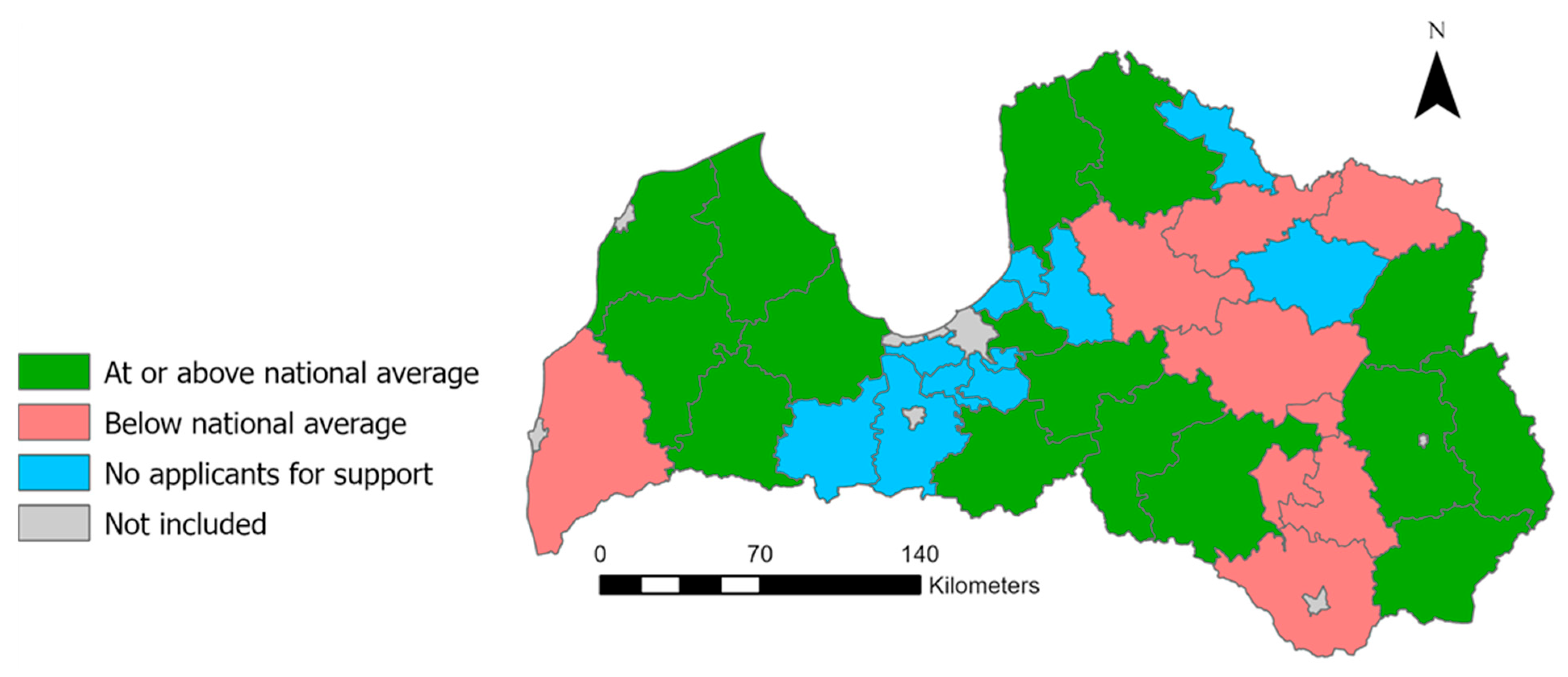

2.3.3. Regression Analysis

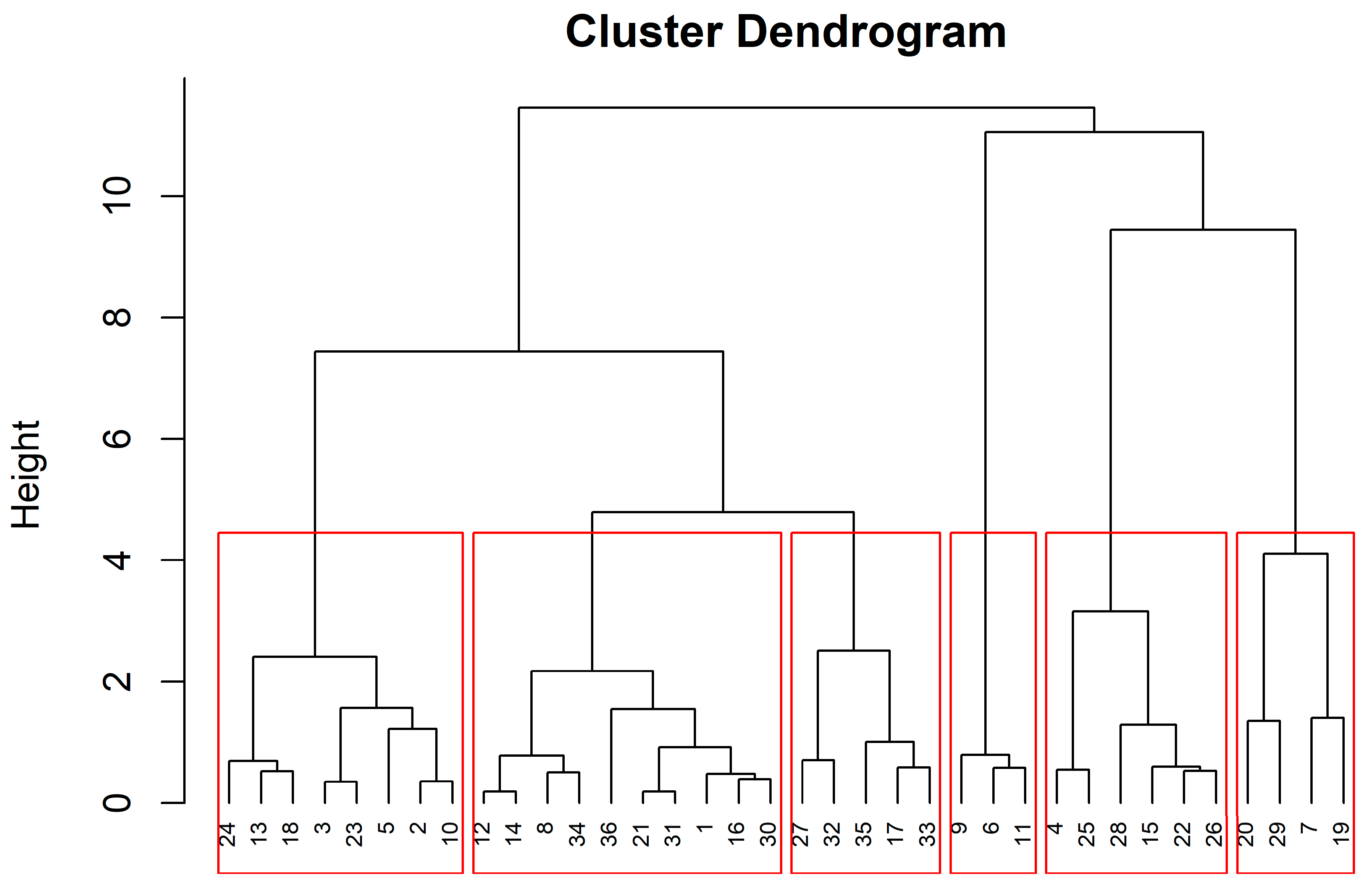

2.3.4. Cluster Analysis

2.4. Spatial Mapping and Visualization

2.5. Software and Reproducibility

- To identify the spread of organic farming, variables were selected to find the organically certified UAA in absolute terms (ha) and as a % of the total UAA area (%): FA1 and FA3. The factors provide an opportunity to assess the contribution of organic production to the total agricultural production in municipalities.

- The UAA as a % of the total area in the municipality: FA2 indicates the degree of specialization of municipalities in the agricultural industry. An important indicator of the economic development of municipalities in Latvia is agricultural output.

- The number of organic production operators: FA4 was selected to identify the attitude of agricultural operators towards organic production and the associated food quality.

- Profit from productive land (EUR per ha−1) indicates the efficiency of agricultural production. The factor (FA6) has been selected to identify the intensity of agricultural production in municipalities.

- The factor “number of agricultural enterprise managers with higher and professional agricultural education” (FA12) was selected to identify the motivation and competence of owners and managers of agricultural enterprises in the field of sustainable development of agricultural production. Educated business managers understand the importance of multifaceted development of rural areas, both in the socio-economic and environmental domains. The number of such specialists in certain areas provides the prospect of successful development of bioregions. The organic farming segment can be considered a basic prerequisite conducive to the creation of bioregions; however, initiatives by local communities are a sine qua non because it is impossible to create a bioregion without public support and authorization. One of the factors in the creation of Italian bioregions was solidarity procurement groups, which ensured the availability of ethical consumer networks; this was considered in the factor analysis of the suitability of 29 municipalities for the creation of bioregions in the north of Italy—the Bologna Apennines region [6]. Such groups could be the most direct factor in the readiness of local communities to take the next step in creating a bioregion. In Latvia, such groups represent consumers who want to buy fresh and high-quality food. Such groups can be found on social media; however, there are also groups that have united based on mutual contact, e.g., a person has relatives in rural areas and supplies the food to a group in the city (coworkers, other relatives, neighbors, etc.). Given that objective statistical data are not available for groups of this type, the category of social factors includes data on the prosperity of individuals and local initiative groups contributing to the preservation of traditions and culture and other territorial development issues supported by European Union funding programs.

- An essential component of the concept of bioregions is the activity of local communities and the desire to develop their municipality and neighborhood areas. One of the available statistical datasets is the number of EAGF and EAFRD beneficiaries under initiative A019.40 Ensuring the functioning of a LAG and activating the territory. This factor (FA5) has been selected to identify the readiness of local communities to play an active role in solving territorial development problems.

- PIT revenue per capita (EUR)—FA8 indicates the standard of living in municipalities, which is one of the most important socio-economic indicators for projecting any trends, having a motivating character, e.g., in the desire of the population for self-sufficiency in their material lives.

- The unemployment rate among the economically active population aged 15–74—this factor (FA9) was selected to identify the potential of municipalities in training and attracting the workforce, as well as possibly to motivate the part of the population looking for an opportunity to work within the limits of their abilities and to make a living for themselves based on the opportunities provided by bioregions.

- Amateur art collectives as a % of the total population shows the most active part of the local population, since participation in such collectives is an intangible desire to improve one’s personality and socialize, as well as preserve the culture, traditions and history of the municipality. At the same time, such an assumption is based on the specific conditions of Latvia. There is a very strong choral and folk dance movement in Latvia, and this movement unites 40,000 people [25]. Self-organizing groups are a strong movement, and their members are highly motivated to organize and participate in various social campaigns. At the same time, they form a discussion platform where people meet three to four times a week and can discuss local current affairs. Such collectives involve not only the participants but also family members and lovers of amateur art, as well as spectators. The events featured by such collectives are usually accompanied by fairs with the participation of masters of fine crafts, craftsmen and home producers. This factor (FA10) is important in the process of creating bioregions as an aspect of social activity in local communities. The diversification of the economy in rural areas and the concept of bioregions contribute to the development of other industries that provide opportunities for the population to engage in the development of the territory and obtain financial self-sufficiency by exploiting available resources. Such industries include tourism, e.g., agritourism, which can be easily combined with the activities of organic farms and involves offering tours and, at the same time, educating visitors about organic farming, local traditions and culture. Another kind of tourism could be ecotourism, which is associated with visiting natural landscapes and attractions. The organizers of this kind of tourism have an opportunity to perform an educational function related to environmental protection, nature and biodiversity. Another segment is home production and crafts, on which, unfortunately, objective and complete statistics could not be found; therefore, it was not included in the present research, but it should definitely be taken into account in future research studies because it is an important indicator, and many years of experience show that crafts are very popular in Latvia.

- Habitat quality (points ha−1) as a factor (FA7) measures the biodiversity of habitats in rural areas and relates to environmental factors.

- Specially protected areas (ha) as a factor (FA13) indicates the possibilities of exploiting an area; the larger the area, the more logical the creation of bioregions in municipalities. This factor involves aspects of nature, environment and landscape quality.

3. Results

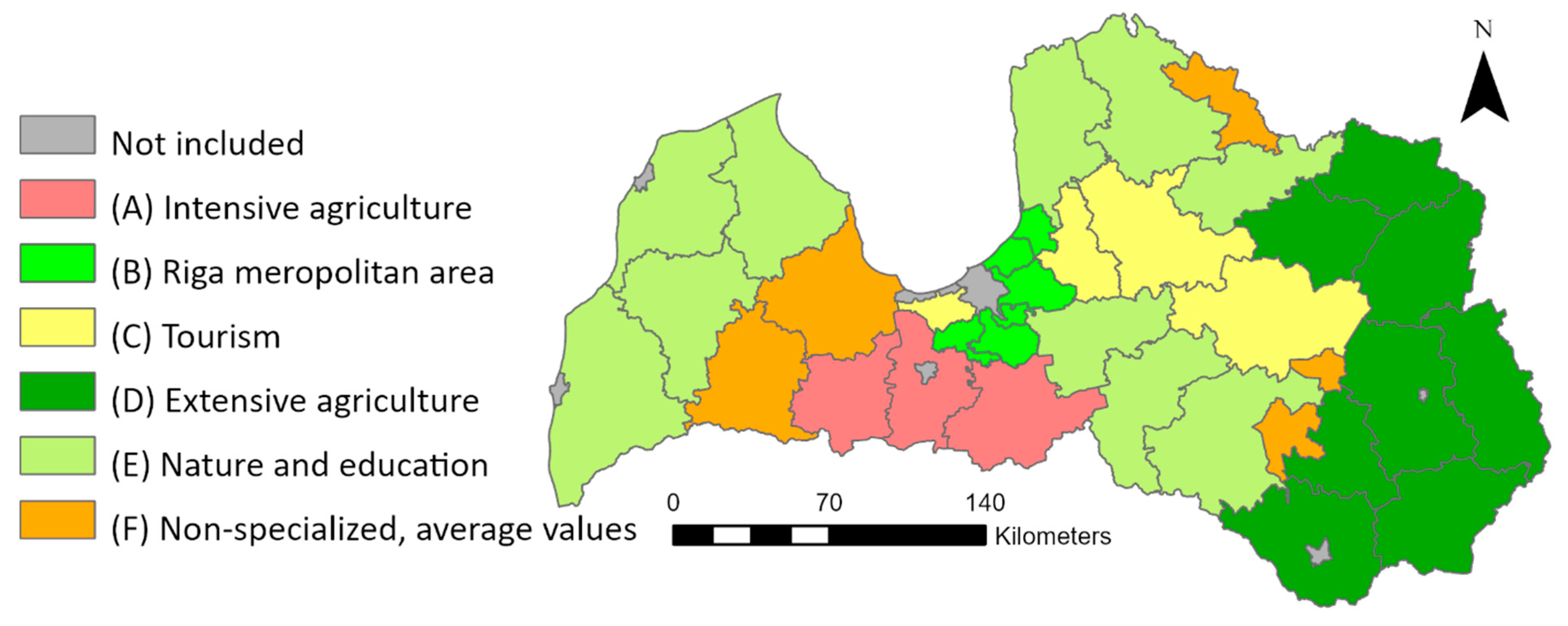

- (1)

- Intensive agriculture (cluster A): Bauska, Dobele and Jelgava Municipalities, in which, given the preconditions for agricultural development (terrain, soil quality, etc.), intensive agricultural production is traditional.

- (2)

- Pieriga region (cluster B): Adazi, Kekava, Olaine, Ropazi, Salaspils and Saulkrasti Municipalities, the locations of which are in the vicinity of the capital, thus shaping their development. The direct impact of Riga is observed through the high level of employment and economic activity and the opportunity to work in the capital. This cluster is characterized by well-developed transportation infrastructure.

- (3)

- Tourism (cluster C): Cesis, Madona, Marupe and Sigulda Municipalities, which are characterized by tourism development, as well as organic agriculture and large areas of specially protected nature territories.

- (4)

- Extensive agriculture (cluster D): Aluksne, Augsdaugava, Balvi, Gulbene, Kraslava, Ludza, Preili and Rezekne Municipalities, which are characterized by organic farming and high social activity.

- (5)

- Nature and education (cluster E): Aizkraukle, South Kurzeme, Jekabpils, Kuldiga, Limbazi, Ogre, Smiltene, Talsi, Valmiera and Ventspils Municipalities, which are characterized by large areas of specially protected nature territories, strong educational backgrounds and social activity and organic farming above the national average.

- (6)

- General specialization (cluster F): Livani, Saldus, Tukums, Valka and Varaklani Municipalities, which are characterized by mediocre levels across all the factors.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PSFP | Public School Food Procurement |

| SCMOs | Community Movement Organizations |

| GAS | Solidarity procurement groups |

| CSA | Community Supported Agriculture |

| PGS | Participation Guarantee Schemes |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease of 2019 |

| EU | European Union |

| CAP | EU Common Agriculture Policy |

| CSB | Central Statistical Bureau |

| RSS | Rural Support Service |

| SLS | State Land Service |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

| EAGF | European Agricultural Guarantee Fund |

| EAFRD | European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development |

| PIT | Personal Income Tax |

| ADC | Agriculture Data Centre |

| LASAM | Sustainable Resources Management Centre |

| RAIM | Regional Development Indicators Module |

| GIS OZOLS | Nature Data Management System |

| UAA | Utilized Agricultural Area |

| LAG | Local Action Group |

References

- Vaishar, A.; Stastná, M. Economically underdeveloped rural regions in Southern Moravia and possible strategies for their future developent. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 97, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, P.F.; de Castro-Pardo, M.; Barossa, V.M.; Azevedo, J.C. Assessing Sustainable Rural Development Based on Ecosystem Services Vulnerability. Land 2020, 9, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, A.; Wallet, F. Innovative Governance and Participatory Research for Agriculture in Territorial Development Processes: Lessons from a Collaborative Research Program (PSDR). Landsc. Agron. 2016, 8, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.P.; Phillips, D.A. Socio-cultural representations of greentrified Pennine rurality. J. Rural Stud. 2001, 17, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, A.; Wallet, F.; Huang, J. A collaborative and multidisciplinary approach to knowledge-based rural development: 25 years of the PSDR program in France. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 97, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assiri, M.; Barone, V.; Silvestri, F.; Tassinari, M. Planning sustainable development o f local productive systems: A methodological approach for the analytical identification of Ecoregions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naglis-Liepa, K.; Proškina, L.; Paula, L.; Kaufmane, D. Modelling the multiplier effect of a local food system. Agron. Res. 2021, 19, 1075–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraljevic, B.; Zanasi, C. Drivers affecting the relation between biodistricts and school meals initiatives: Evidence from the Cilento biodistrict. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1235871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Landscape Policy Implementation Plan for 2024–2027; Order of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Latvia: Riga, Republic of Latvia, 2024; Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/350823-par-ainavu-politikas-ieviesanas-planu-2024-2027-gadam (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Feola, G.; Koretskaya, O.; Moore, D. (Un)making in sustainability transformation beyond capitalism. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 69, 102290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberio, M.; Moralli, M. Social innovation in alternative food networks. The role of co-producers in Campi Aperti. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Ferre, M.G.; Gallar, D.; Calle-Colado, A.; Pimentel, V. Agroecological education for food sovereignty: Insights from formal and non-formal spheres in Brazil and Spain. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 88, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, A.; Vittori, F.; Uleri, F. Unmaking capitalism through community empowerment: Findings from Italian agricultural experiences. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 101, 103064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, J.P.; Lass, D.A. Consumer Benefits from Community supported Agriculture Membership. Rev. Agric. Econ. 1998, 20, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J. Communitarian cooperative organic rice farming in Hongdong District, South Korea. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 37, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuellar-Padilla, M.; Haro-Perez, I.; Begiristain-Zubillaga, M. Participatory Guarantee Systems: When People Want to Take Part. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, M.; Marty, P.; Prevot, A.C. Caring for vineyards: Transforming farmer-vine relations and practices in viticulture French farms. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 80, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raagmaa, G. Estonian population and regional development during the last 30 years—Back to the small town? Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2023, 15, 826–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lāce, I. Place Attachment and Diversity of Lifestyles in Rural Latvia Thesis Summary. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Latvia, Riga, Latvia, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecki, E.K. Entrepreneurs, networks, and economic development: A review of recent research. In Reflections and Extensions on Key Papers of the First Twenty-Five Years of Advances; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guzman, M.R.; Kim, S.; Taylor, S.; Padasas, I. Rural communities as a context for entrepreneurship: Exploring perceptions of youth and business owners. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 80, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law on Specially Protected Nature Territories; The Supreme Council of the Republic of Latvia: Riga, Republic of Latvia, 1993; Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/59994 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia. Population and Its Changes. Available online: https://stat.gov.lv/lv/statistikas-temas/iedzivotaji/iedzivotaju-skaits/247-iedzivotaju-skaits-un-ta-izmainas?themeCode=IR (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Rural Support Service of Latvia. European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD), European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF). Available online: https://www.lad.gov.lv/en/investment-measures (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Daroy, A.; Zeunert, J. Solidarity as spectacle: Resistance, resilience, and renewal in the Latvian Song and Dance Celebration. Res. Drama Educ. J. Appl. Theatre Perform. 2024, 29, 422–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naglis-Liepa, K.; Paula, L.; Janmere, L.; Kaufmane, D.; Proskina, L. Local Food Development Perspectives in Latvia: A Value-Oriented View. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Context | Economic | Social | Environmental | Political and Legal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preconditions | Organic farming; crafts; tourism | Community approach; education Employment | Nature protection; sustainable use of resources | EU Green Deal; EU sustainability strategies CAP |

| Internal incentives | Low economic potential; access to finance and innovation | Population; lack of knowledge; public services | Intensive production; brownfield areas | Lack of representation in city administrations; production policy |

| Strategy | Cooperation; protection and development of a new or traditional market segment | Educating and involving communities in decision-making | Conservation and sustainable use of ecosystem services | Development and adoption of laws and regulations and support mechanisms |

| Results | Self-producing and self-sufficient autonomy | Conscious consumption practices; prosperity and well-being | Biologically diverse and ecologically stable environment | Sustainable development of rural areas |

| Step | Description | Data and Methods | References and Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Data collection | Thirteen socio-economic, environmental and agricultural indicators for 36 municipalities (2021); CSB, RSS, SLS, ADC, LASAM, GIS OZOLS | [22,23,24] |

| 2 | Data preparation | Standardization of variables; multicollinearity check (correlation matrix); normality testing (Mardia test) | RStudio 4.3.3; psych, ggcorrplot |

| 3 | Principal Components Analysis (PCA) | Principal Axis Factoring with Varimax rotation; factor extraction, naming and interpretation | RStudio psych::principal |

| 4 | Regression analysis | Multiple regression to assess the impact of factor structures on young farmer support (A006.01) | RStudio, lm |

| 5 | Cluster analysis | Ward’s method with Euclidean distance; classification of municipalities; validation of clusters | RStudio, cluster |

| 6 | Visualization | Spatial mapping of clusters and regression results | ArcGIS Pro; RStudio graphics (ggcorrplot, base plotting) |

| Variable | Data Source | Symbol RStudio |

|---|---|---|

| Organically certified UAA, ha | CSB | FA1 |

| UAA as a % of the total area in the municipality | CSB | FA2 |

| Organically certified UAA as a % of the total UAA | CSB | FA3 |

| Number of organic production operators | ADC | FA4 |

| EAGF and EAFRD beneficiaries under initiative A019.40 Ensuring the functioning of a LAG and activating the territory | LAD | FA5 |

| Profit from productive land, EUR ha−1 | LASAM | FA6 |

| Habitat quality, points ha−1 | LASAM | FA7 |

| PIT revenue per capita, EUR | RAIM | FA8 |

| Unemployment rate among the economically active population aged 15–74, % | RAIM | FA9 |

| Amateur art collectives as a % of the total population | Ministry of Culture | FA10 |

| Tourists served as a % of the total population | CSB | FA11 |

| Number of agricultural enterprise managers with higher and professional agricultural education | CSB | FA12 |

| Specially protected areas, ha | GIS OZOLS | FA13 |

| Indicator | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA1 | 0.00 | 25,197.00 | 8393.81 | 6674.84 | 25,197.00 |

| FA2 | 11.09 | 56.22 | 32.46 | 11.07 | 45.13 |

| FA3 | 0.00 | 24.96 | 12.74 | 7.68 | 24.96 |

| FA4 | 0.00 | 260.00 | 95.69 | 76.31 | 260.00 |

| FA5 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 0.89 | 0.62 | 2.00 |

| FA6 | 39.00 | 300.00 | 110.44 | 61.56 | 261.00 |

| FA7 | 4.00 | 10.00 | 5.80 | 1.18 | 6.00 |

| FA8 | 321.00 | 1164.00 | 594.44 | 213.31 | 843.00 |

| FA9 | 5.10 | 22.70 | 9.14 | 4.11 | 17.60 |

| FA10 | 0.07 | 0.61 | 0.31 | 0.12 | 0.54 |

| FA11 | 0.83 | 39.44 | 9.80 | 8.64 | 38.60 |

| FA12 | 10.00 | 1359.00 | 567.47 | 373.83 | 1349.00 |

| FA13 | 0.00 | 45,835.31 | 5833.00 | 8285.05 | 45,835.31 |

| Symbol | Name | Factor |

|---|---|---|

| FG1 | Sustainable agriculture | Organically certified UAA, ha |

| Organically certified UAA as a % of the total UAA | ||

| Number of organic production operators | ||

| Unemployment rate among the economically active population aged 15–74, % | ||

| Amateur art collectives as a % of the total population | ||

| Number of agricultural enterprise managers with higher and professional agricultural education | ||

| Specially protected areas, ha | ||

| FG2 | Intensive agriculture | UAA as a % of the total area in the municipality |

| Profit from productive land, EUR ha−1 | ||

| FG3 | Tourism | Habitat quality, points ha−1 |

| PIT revenue per capita, EUR | ||

| Tourists served as a % of the total population |

| The Factors in the Creation of Bioregions | Cluster | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| Organically certified UAA, ha | 2542.00 | 291.50 | 12,420.75 | 14,645.63 | 11,009.00 | 4312.40 |

| UAA as a % of the total area in the municipality | 53.15 | 16.70 | 30.80 | 37.33 | 30.88 | 38.11 |

| Organically certified UAA as a % of the total UAA | 2.60 | 4.52 | 16.72 | 19.14 | 14.35 | 12.57 |

| Number of organic production operators | 33.00 | 6.50 | 129.50 | 179.63 | 120.33 | 47.40 |

| Profit from productive land, EUR ha−1 | 278.67 | 91.17 | 84.00 | 73.13 | 106.11 | 125.20 |

| Habitat quality, points ha−1 | 4.13 | 7.02 | 6.18 | 5.30 | 5.54 | 6.02 |

| PIT revenue per capita, EUR | 575.33 | 890.25 | 733.75 | 392.00 | 578.03 | 500.20 |

| Unemployment rate among the economically active population aged 15–74, % | 7.63 | 5.65 | 7.00 | 14.71 | 7.51 | 10.04 |

| Amateur art collectives as a % of the total population | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.30 | 0.37 |

| Tourists served as a % of the total population | 11.22 | 5.58 | 28.32 | 5.00 | 9.25 | 5.74 |

| Number of agricultural enterprise managers with higher and professional agricultural education | 652.33 | 49.67 | 527.75 | 919.25 | 710.22 | 386.40 |

| Specially protected areas, ha | 2789.71 | 688.85 | 14,534.46 | 4658.42 | 7587.38 | 3102.39 |

| Cluster | Dominant Indicators | Secondary Indicators | Typical Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| A—Intensive agriculture | High FA2 (share of UAA in municipality), FA6 (profit from land) | Moderate FA8 (PIT revenue) | Municipalities with favorable soils and terrain, long-standing intensive farming tradition |

| B—Riga metropolitan area (Pieriga) | High FA8 (income), FA12 (educated managers), strong employment | Medium FA2 (UAA share), FA11 (tourism) | High socio-economic activity, strong commuting ties to Riga, developed infrastructure |

| C—Tourism | High FA10 (amateur art collectives), FA11 (tourists served), FA7 (habitat quality) | Moderate FA3 (organic UAA share) | Municipalities with cultural vitality, nature protection areas and tourism flows |

| D—Extensive agriculture | High FA1–FA3 (organic farming indicators), FA4 (organic operators) | High FA9 (unemployment), FA10 (cultural activity) | Rural municipalities with strong organic sectors, high social activity |

| E—Nature and education | High FA13 (protected areas), FA12 (educated managers), FA10 (cultural activity) | Moderate FA1–FA3 (organic land) | Large areas of protected land, strong educational and cultural background, above-average organic farming |

| F—Non-specialized (average values) | None strongly dominant; mid-level across FA1–FA13 | Slightly higher FA8 (income) | Municipalities with average performance across factors |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Naglis-Liepa, K.; Megne, I.; Proskina, L.; Paula, L.; Kaufmane, D.; Pelse, M. Analysis of Factors Influencing the Formation of Bioregions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8288. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188288

Naglis-Liepa K, Megne I, Proskina L, Paula L, Kaufmane D, Pelse M. Analysis of Factors Influencing the Formation of Bioregions. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8288. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188288

Chicago/Turabian StyleNaglis-Liepa, Kaspars, Inga Megne, Liga Proskina, Liga Paula, Dace Kaufmane, and Modrite Pelse. 2025. "Analysis of Factors Influencing the Formation of Bioregions" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8288. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188288

APA StyleNaglis-Liepa, K., Megne, I., Proskina, L., Paula, L., Kaufmane, D., & Pelse, M. (2025). Analysis of Factors Influencing the Formation of Bioregions. Sustainability, 17(18), 8288. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188288