Does Digitalization Mean Equality? Digital Finance and Balanced Development Between Counties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Finance and Urban–Rural Income Gap

2.2. Digital Finance and Balanced Development Between Areas

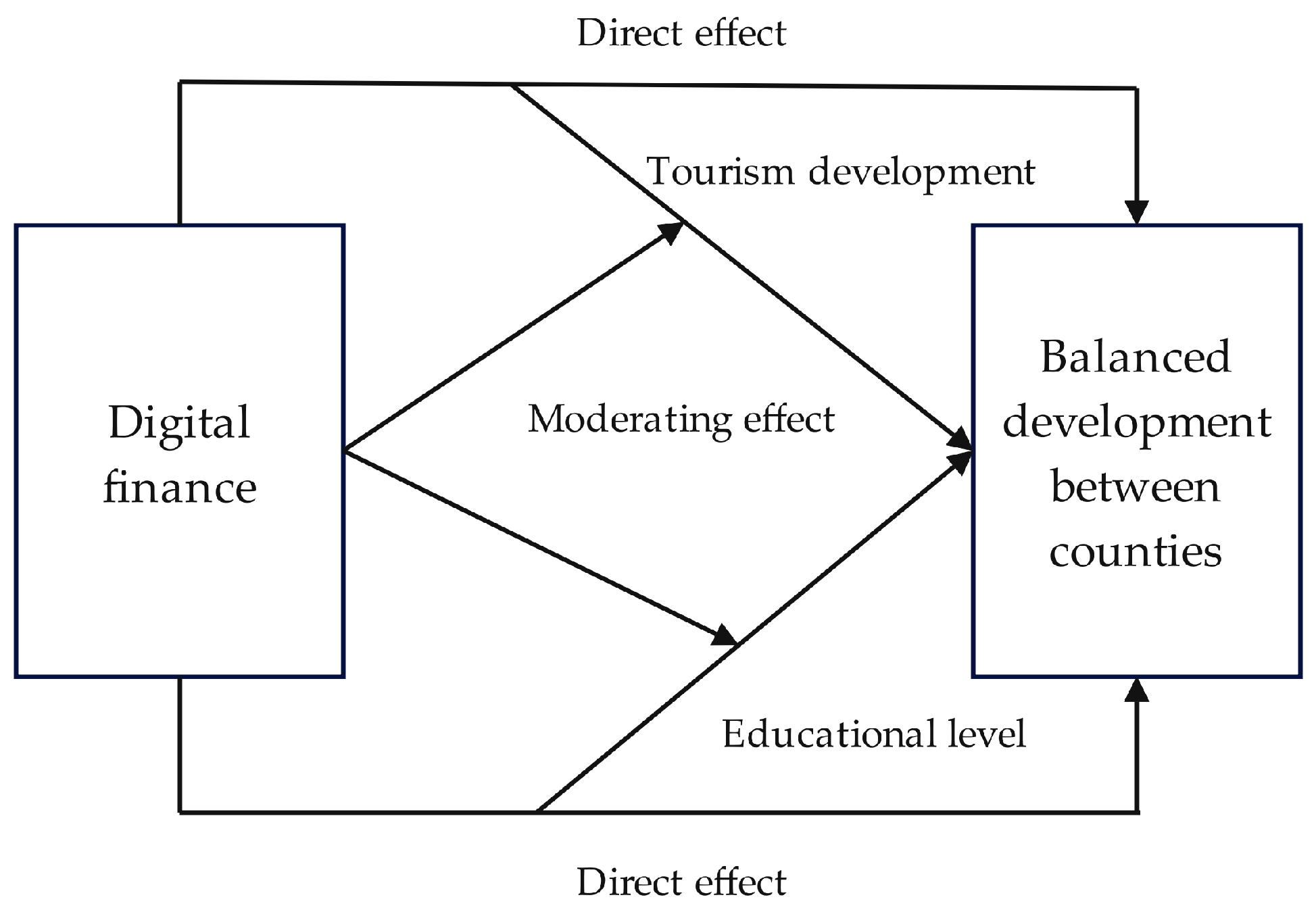

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

3.1. The Impact of Digital Finance on Balanced Development Between Counties

3.2. Digital Finance, Tourism Development, and Balanced Development Between Counties

3.3. Digital Finance, Educational Level, and Balanced Development Between Counties

4. Research Design

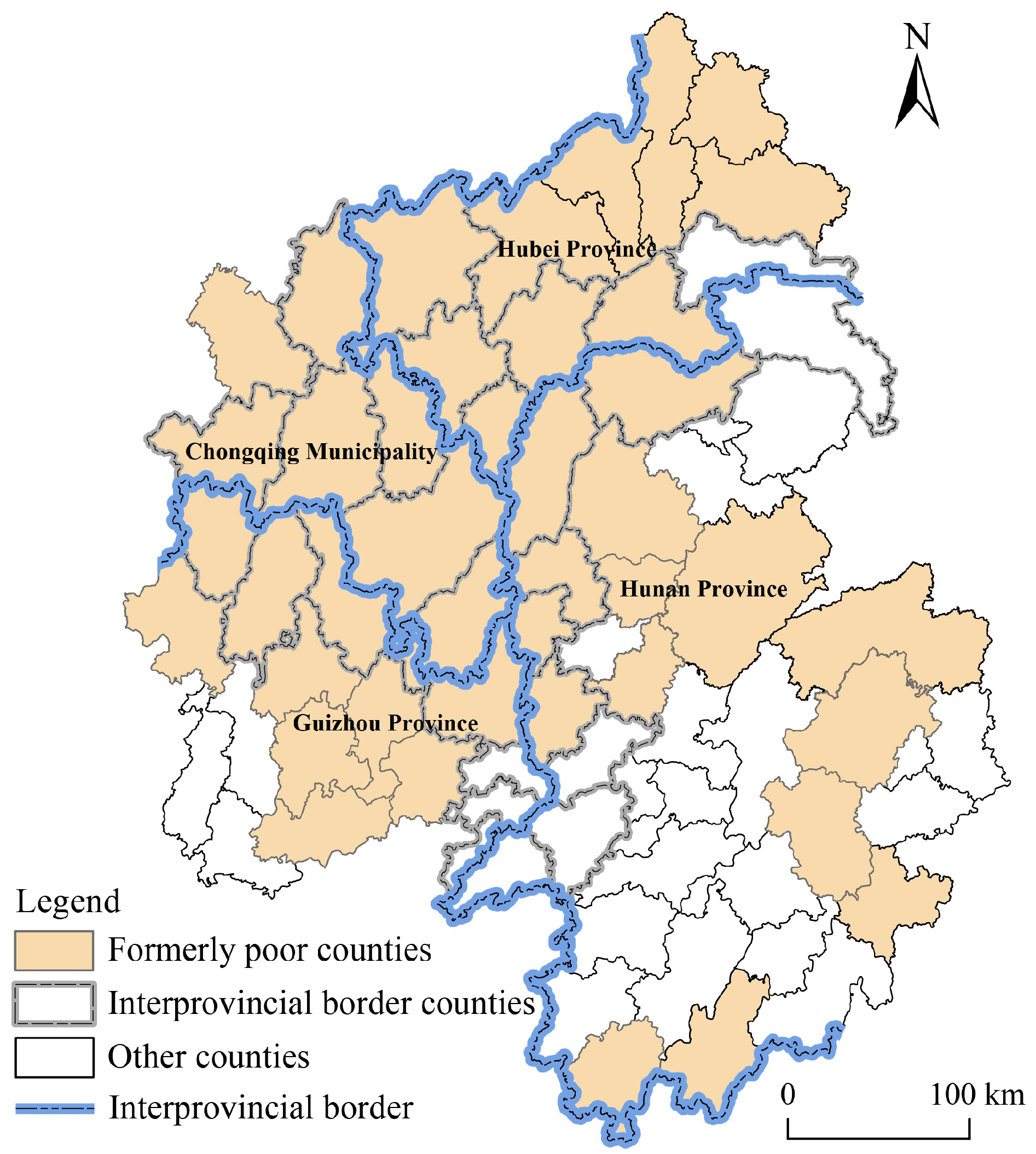

4.1. Research Area

4.2. Model Setting

4.2.1. Benchmark Regression Model

4.2.2. Panel Threshold Regression Model

4.2.3. Moderating Effect Model

4.3. Variable Measurement

4.3.1. Dependent Variable

4.3.2. Independent Variable

4.3.3. Moderating Variable

4.3.4. Control Variable

4.4. Data Sources

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Baseline Regression Analysis

5.2. Robustness Analysis

5.2.1. Substituting Explained Variable

5.2.2. Decreasing Particular Samples

5.2.3. Eliminating Unusual Years

5.2.4. Alternative Estimation Regression

5.2.5. Controlling High-Dimensional Fixed Effect

5.2.6. Endogeneity Test

5.3. Heterogenous Analysis

5.3.1. Formerly Poor Counties and Non-Formerly Poor Counties

5.3.2. Interprovincial Border Counties and Non-Interprovincial Border Counties

5.3.3. Before and After Poverty Alleviation

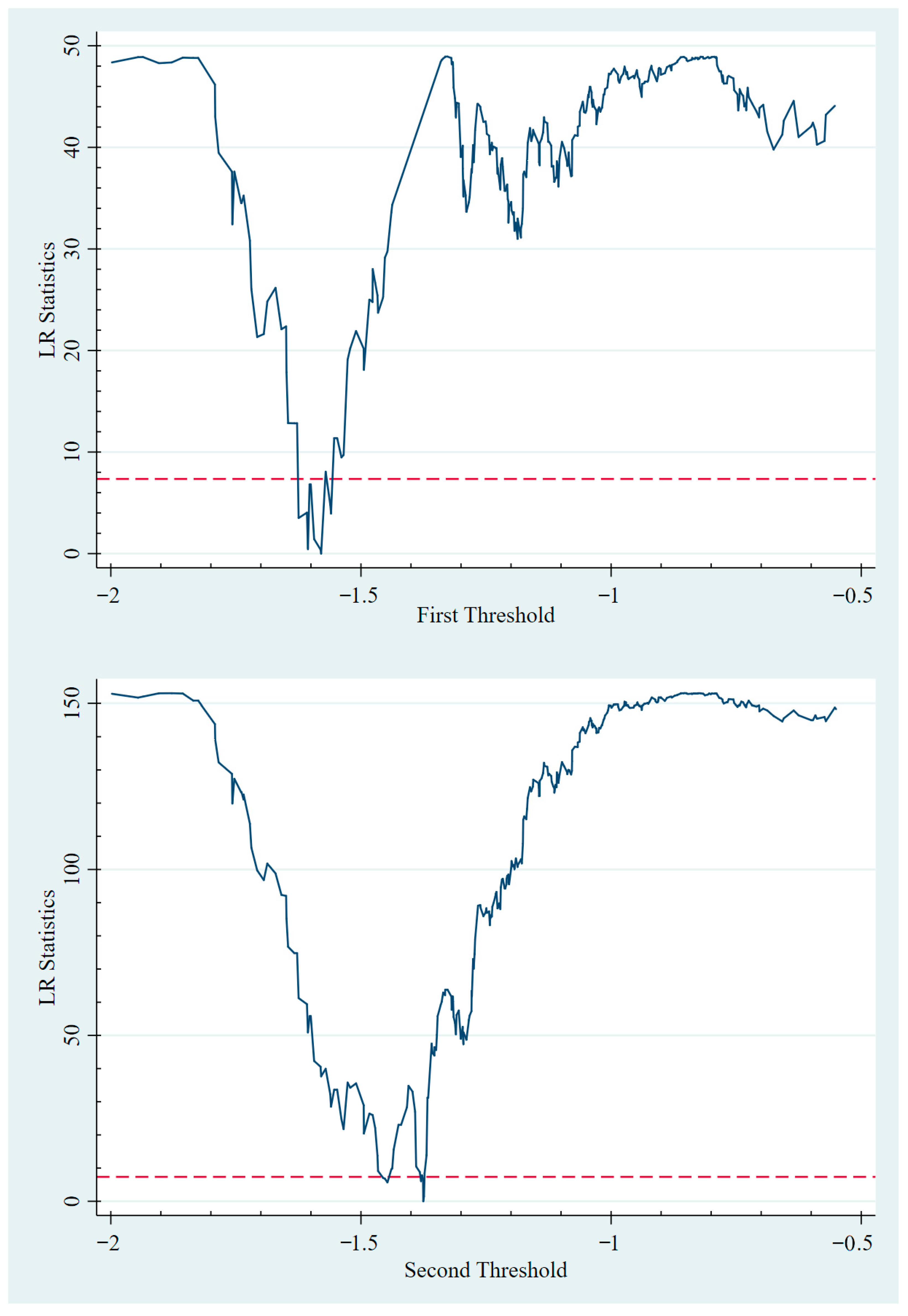

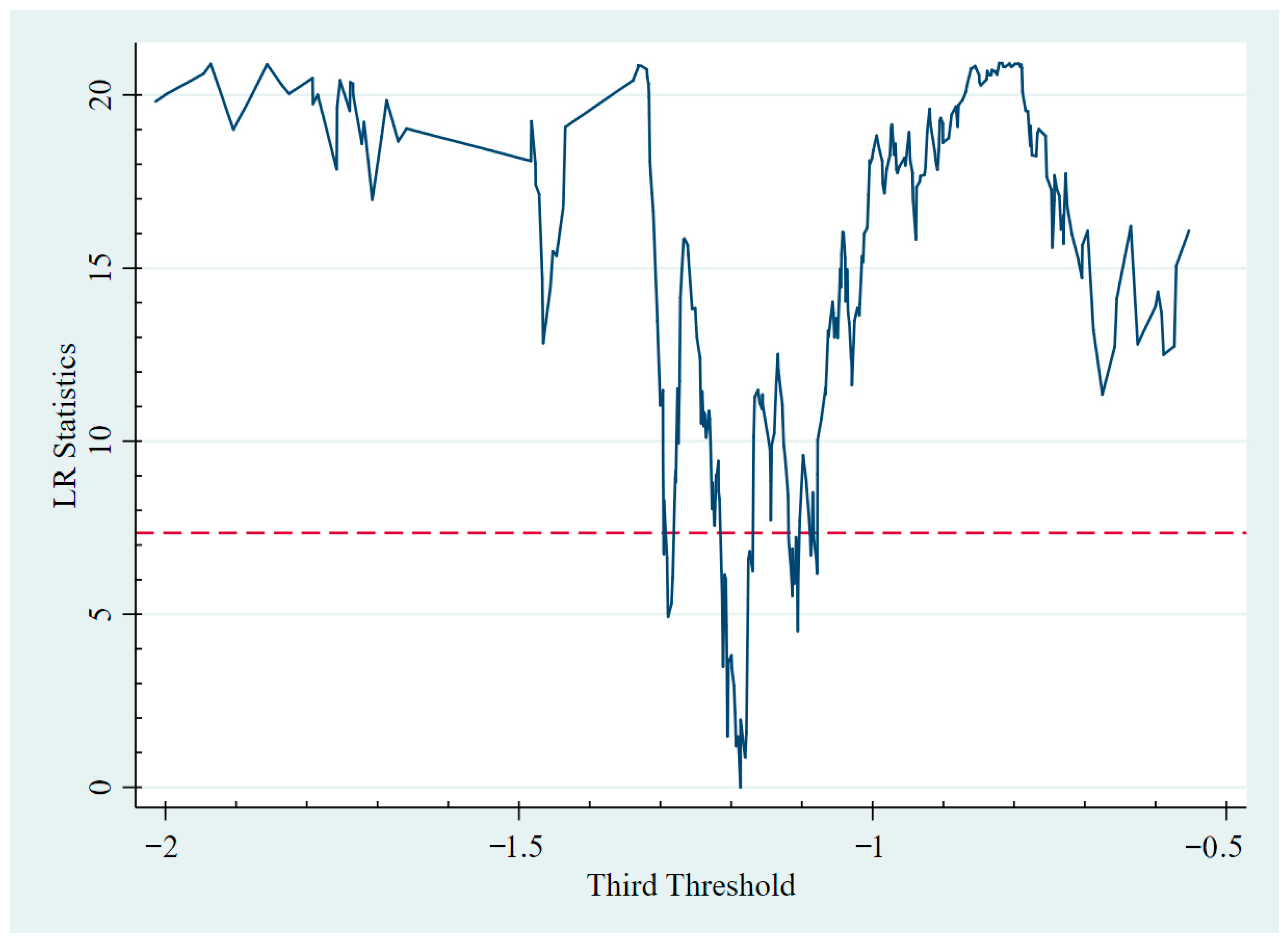

5.4. Non-Linear Effect Analysis

5.5. Moderating Effect Analysis

5.5.1. The Moderating Effect of Tourism Development

5.5.2. The Moderating Effect of Educational Level

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Main Conclusions

7.2. Theoretical Implications

7.3. Policy Implications

7.4. Limitations and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DF | Digital finance |

| WMA | Wuling Mountain Area |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| TLGH | Tourism-led growth hypothesis |

References

- UNDP. Human Development Report; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y. Regional social development gap and regional coordinated development based on mixed-methods research: Evidence from China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 927011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zhao, H.; Guo, R. The new trend and coping strategies of regional development gap in China. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 42, 1–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Kong, W. Agglomeration of innovative elements and balanced development between cities: “One city dominates” or “together with cities for development”. Ind. Econ. Res. 2024, 3, 88–100. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. Impact of digital finance on financial inclusion and stability. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2018, 18, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Wu, X.; Shi, L.; Wan, Y.; Hao, Z.; Ding, J.; Wen, Q. How does the digital economy affect the urban–rural income gap? Evidence from Chinese cities. Habitat Int. 2025, 157, 103327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaghir, M. Digital risks and Islamic FinTech: A road map to social justice and financial inclusion. J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Wang, K.; Xu, H.; Li, M. Has digital financial inclusion narrowed the urban-rural income gap: The role of entrepreneurship in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Luo, T.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Chuang, Y.-C. Digital financial inclusion and the urban–rural income gap in China: Empirical research based on the Theil index. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2023, 36, 2156575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-c.; Feng, S.-x.; Xie, X. Spatial effect of digital financial inclusion on the urban–rural income gap in China—Analysis based on path dependence. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2023, 36, 2106279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yin, M.; Wang, H.; Xiang, Y. Digital finance, digital usage Divide, and urban–rural income gap: Evidence from China. Systems 2025, 13, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Gao, X. The impact and heterogeneity of digital inclusive finance development on poverty alleviation-based on county-level panel data in Jing-Jin-Ji region. J. Econ. Sustain. 2024, 6, 20–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D. Financial Inclusion in the Middle East and North Africa: Analysis and Roadmap Recommendations. In World Bank Policy Research Working Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chiriko, A.Y.; Alemu, S.H.; Kim, S. Tourism-led growth hypothesis (TLGH) in Africa: Does institutional quality matter? Tour. Rev. 2025, 80, 568–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H. Digital literacy education for the development of digital literacy. Int. J. Digit. Lit. Digit. Competence (IJDLDC) 2014, 5, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranti, R.C.; Siregar, S.I.; Willyana, A.B. How does inclusion of digital finance, financial technology, and digital literacy unlock the regional economy across districts in Sumatra? A spatial heterogeneity and sentiment analysis. GeoJournal 2024, 89, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicular, T.; Ximing, Y.; Gustafsson, B.; Shi, L. The urban–rural income gap and inequality in China. Rev. Income Wealth 2007, 53, 93–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S. Has digital financial inclusion narrowed the urban–rural income gap? A study of the spatial influence mechanism based on data from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, J.-K.; Li, Z.-H.; Yu, J.-Y.; Ding, C.J. Inclusive or fraudulent: Digital inclusive finance and urban–rural income gap. Asia-Pac. Financ. Mark. 2024, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Xiao, Y.; Hu, B. Digital financial inclusion, industrial structure and urban–rural income disparity: Evidence from Zhejiang Province, China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303666. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Fan, H.; Cheng, Z. Social network of digital inclusive finance and urban-rural income gap. Appl. Econ. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Chatterjee, A. Impacts of ICT and digital finance on poverty and income inequality: A sub-national study from India. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2022, 29, 378–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, T.C.; Pratama, H.; Masbar, R.; Effendi, R. Does financial inclusion alleviate household poverty? Empirical evidence from Indonesia. Econ. Sociol. 2019, 12, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, X.; Wu, T.; Deng, W. Reducing farmers’ poverty vulnerability in China: The role of digital financial inclusion. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2023, 27, 1445–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Li, W.; Teo, B.S.X.; Othman, J. Can China’s digital inclusive finance alleviate rural poverty? An empirical analysis from the perspective of regional economic development and an income gap. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Velthoven, A.; De Haan, J.; Sturm, J.E. Finance, income inequality and income redistribution. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2019, 26, 1202–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moraes, C.O.; Roquete, R.M.; Gawryszewski, G. Who needs cash? Digital finance and income inequality. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 91, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odlyzko, A.; Tilly, B. A refutation of Metcalfe’s Law and a better estimate for the value of networks and network interconnections. Manuscr. March 2005, 2, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, Y.; Yu, X.; Li, H. The nonlinear impact of FinTech on the real economic growth: Evidence from China. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2023, 32, 1138–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Koster, S.; Chen, X. Digital divide or dividend? The impact of digital finance on the migrants’ entrepreneurship in less developed regions of China. Cities 2022, 131, 103896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, M.; Li, S.; Wu, Z. Can digital finance development improve balanced regional investment allocations in developing countries?—The evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2023, 56, 101035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Shimei. How digital finance affects income distribution: Evidence from 280 cities in China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267486. [Google Scholar]

- Solo, R.A. Neoclassical economics in perspective. J. Econ. Issues 1975, 9, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketterer, J.A. Digital Finance: New Times, New Challenges, New Opportunities; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Fan, A. Digital finance, industrial structure adjustment and high-quality economic development: From the perspective of gap between the North and the South. Financ. Econ. 2022, 11, 27–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, A.; Naima, U. Rethinking digital financial inclusion: Evidence from Bangladesh. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. Contesting digital finance for the poor. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2020, 22, 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Mignamissi, D.; Djijo, A.J.T. Digital divide and financial development in Africa. Telecommun. Policy 2021, 45, 102199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, M.M.; Subroto, S.; Chowdhury, N.; Koch, K.; Ruttan, E.; Turin, T.C. Dimensions and barriers for digital (in) equity and digital divide: A systematic integrative review. Digit. Transform. Soc. 2024, 4, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feurich, M.; Kourilova, J.; Pelucha, M.; Kasabov, E. Bridging the urban-rural digital divide: Taxonomy of the best practice and critical reflection of the EU countries’ approach. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2024, 32, 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, J.; Wilson, K. Causality between trade and tourism: Empirical evidence from China. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2001, 8, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Zhang, D. Does tourism promote economic growth in Chinese ethnic minority areas? A nonlinear perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Voda, M.; Wang, K. Balancing efficiency and fairness: The role of tourism development in economic growth and urban–rural income gap. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 5259–5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y. Cure-all or curse? A meta-regression on the effect of tourism development on poverty alleviation. Tour. Manag. 2023, 94, 104650. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan, R.; Suardi, S. Panel evidence on the impact of tourism growth on poverty, poverty gap and income inequality. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwuanyi, U.; Ugwuoke, R.; Onyeanu, E.; Festus Eze, E.; Isahaku Prince, A.; Anago, J.; Ibe, G.I. Financial inclusion-economic growth nexus: Traditional finance versus digital finance in Sub-Saharan Africa. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2133356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Qi, S. Digital infrastructure expansion and economic growth in Asian countries. J. Bus. Econ. Options 2024, 7, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mandić, A.; Mrnjavac, Ž.; Kordić, L. Tourism infrastructure, recreational facilities and tourism development. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 24, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaimovic, A.; Meskovic, M.N.; Dedovic, L.; Arnaut-Berilo, A.; Zaimovic, T.; Torlakovic, A. Measuring digital financial literacy. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 236, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.A.; Khan, M.S. The role of financial literacy, digital literacy, and financial self-efficacy in FinTech adoption. Investment Manag. Financ. Innov. 2024, 21, 370. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, P.; Phutela, N.; Guess, W. Role of Financial and Digital Literacy in Inclusive Finance and Sustainable Development. In FinTech and Financial Inclusion; Routledge: London, UK, 2025; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, A. The impact of openness on bridging educational digital divides. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2009, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Wei, Z.; Wang, Y. The mechanisms and pathways of the mutual promotion between enhancing human capital and bridging the digital divide. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2025, 1, 53–61. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zhuge, R.; Han, J.; Zhao, P.; Gong, M. Research on the impact of digital inclusive finance on rural human capital accumulation: A case study of China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 936648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Respati, H.; Triatmanto, B.; Wahyuni, N. Digital finance, human capital, and urban innovation in Indonesia. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2024, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, P.; Liu, W.; Huang, S. Securties market, capital space allocation and coordinated development of regional economy. Econ. Res. J. 2014, 49, 121–132. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Tan, Z.; Zuo, Y. Digital inclusive finance and common prosperity: The threshold effect based on rural revitalization. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 100, 104096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Gan, C.; Chen, L.; Voda, M. Poor residents’ perceptions of the impacts of tourism on poverty alleviation: From the perspective of multidimensional poverty. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Shen, T. Spatial evolution characteristics and driving forces of Chinese highly educated talents. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2021, 76, 326–340. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, J.; He, Z. Digital Economy, financial Inclusion, and inclusive growth. Econ. Res. J. 2019, 54, 71–86. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Morote, R.; Pontones-Rosa, C.; Núñez-Chicharro, M. The effects of e-government evaluation, trust and the digital divide in the levels of e-government use in European countries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 154, 119973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y. The Impacts of Digital Economy on Balanced and Sufficient Development in China: A Regression and Spatial Panel Data Approach. Axioms 2023, 12, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hua, C.; Jiang, M.S.; Miao, J. The spatial spillover effect of financial growth on high-quality development: Evidence from Yellow River Basin in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Du, B.; Yang, B. How does digital inclusive finance affect common prosperity: Empirical evidence from China’s underdeveloped and developed regions. Cities 2025, 158, 105640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Pang, Y. The impact of digital financial inclusion on the balanced development of provincial economies. Zhejiang Acad. J. 2024, 110–118. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, R. Divide or dividend: How digital finance impacts educational equality. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 55, 103858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shen, Y. Digital financial inclusion and regional economic imbalance. China Econ. Q. 2022, 22, 1805–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z. Deepening or lessening? The effects of tourism on regional inequality. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, J.L.; Li, G.; Goh, C. Tourism and regional income inequality: Evidence from China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 58, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandano, M.G.; Mastrangioli, A.; Palma, A. The digital divide and the growth of the hospitality industry: The case of Italian inner areas. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2023, 15, 1509–1532. [Google Scholar]

- Capo, J.; Font, A.R.; Nadal, J.R. Dutch disease in tourism economies: Evidence from the Balearics and the Canary Islands. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jesus, F.; Vicente, M.R.; Bacao, F.; Oliveira, T. The education-related digital divide: An analysis for the EU-28. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 56, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Song, B.; Huang, S. The development of informatics education in Europe: The conception of informatics, discipline, and curriculum. Glob. Educ. 2025, 54, 96–110. [Google Scholar]

| Type | Variables | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Bal | 0.761 | 0.153 | 0.293 | 0.999 | |

| Independent variable | lnDig | 4.477 | 0.432 | 1.903 | 4.987 | 1.41 |

| Moderating variable | lnTour | 2.415 | 1.0223 | −0.275 | 6.189 | 1.60 |

| lnEdu | 10.880 | 0.610 | 8.931 | 12.274 | 1.06 | |

| Control variable | lnGov | −1.169 | 0.387 | −2.879 | −0.292 | 1.80 |

| lnTrans | 7.956 | 0.666 | 5.704 | 9.221 | 1.31 | |

| lnUrb | −0.855 | 0.262 | −2.846 | −0.069 | 1.62 | |

| lnIndus | 0.569 | 0.668 | −1.139 | 4.296 | 1.26 | |

| lnScal | 5.175 | 0.500 | 4.109 | 6.894 | 1.58 | |

| lnCons | −0.040 | 0.573 | −1.490 | 1.562 | 1.24 |

| Variables | lnBal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| lnDig | 0.053 *** (0.019) | 0.079 *** (0.013) | 0.054 ** (0.021) | 0.095 *** (0.028) | |

| L.lnDig | 0.058 *** (0.009) | ||||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 0.570 ** (0.239) | 0.224 (0.182) | 1.461 ** (0.666) | 1.361 ** (0.668) | 0.233 (0.170) |

| County FE | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 639 | 639 | 639 | 639 | 639 |

| R2 | 0.243 | 0.261 | 0.154 | 0.152 | 0.309 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnDig | 0.233 *** (0.079) | 0.045 ** (0.022) | 0.064 ** (0.024) | 0.051 * (0.028) | 0.048 *** (0.011) | 0.054 *** (0.015) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 0.475 * (0.268) | 0.923 (0.808) | 2.520 ** (1.112) | 0.567 (0.405) | −22.601 (18.383) | 0.344 *** (0.128) |

| County FE | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Year FE | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| County × Year FE | No | No | No | Yes | No | |

| LM statistic | 74.071 (0.000) | |||||

| F statistic | 6386.42 <16.38> | |||||

| Observations | 639 | 587 | 426 | 639 | 639 | 639 |

| R2 | 0.131 | 0.123 | 0.047 | 0.882 | 0.304 |

| Variables | Formerly Poor Counties | Non-Formerly Poor Counties | Interprovincial Border Counties | Non-Interprovincial Border Counties | 2014~2020 | 2021~2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| lnDig | 0.088 ** (0.040) | 0.105 ** (0.039) | 0.095 * (0.053) | 0.096 *** (0.032) | 0.071 *** (0.024) | −0.069 (0.152) |

| Control variable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 1.355 (1.075) | 1.035 (0.742) | 0.593 (0.856) | 2.358 ** (0.999) | 2.549 *** (0.965) | 3.664 ** (1.479) |

| County FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 378 | 261 | 243 | 396 | 497 | 142 |

| R2 | 0.102 | 0.074 | 0.246 | 0.151 | 0.071 | 0.023 |

| Threshold Model Type | F-Value | 1% | 5% | 10% | Threshold Estimate Value | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single threshold model | 44.387 *** | 8.374 | 3.871 | 1.940 | −1.580 | [−1.625, −1.560] |

| Double threshold model | 150.563 *** | 25.184 | 14.349 | 10.721 | −1.375 | [−1.376, −1.373] |

| Triple threshold model | 20.923 *** | 11.269 | 7.332 | 5.904 | −1.187 | [−1.295, −1.078] |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| lnDig | 0.372 *** (0.091) | 0.498 * (0.294) | |

| lnDig × I (TH ≤ r1) | −0.019 (0.021) | ||

| lnDig × I (r2 ≥ TH > r1) | 0.026 (0.020) | ||

| lnDig × I (r3 ≥ TH > r2) | 0.062 *** (0.019) | ||

| lnDig × I (TH > r3) | 0.079 *** (0.019) | ||

| L.lnTour | 0.347 *** (0.098) | ||

| lnEdu | 0.171 (0.131) | ||

| lnDig×L.lnTour | −0.074 *** (0.020) | ||

| lnDig×lnEdu | −0.037 (0.027) | ||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 0.749 (0.136) | 0.004 (0.051) | −0.468 (1.551) |

| County FE | Yes | Yes | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | |

| Observations | 639 | 639 | 639 |

| R2 | 0.282 | 0.662 | 0.150 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gan, C.; Sun, X.; Voda, M.; Wang, K. Does Digitalization Mean Equality? Digital Finance and Balanced Development Between Counties. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188276

Gan C, Sun X, Voda M, Wang K. Does Digitalization Mean Equality? Digital Finance and Balanced Development Between Counties. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188276

Chicago/Turabian StyleGan, Chang, Xinying Sun, Mihai Voda, and Kai Wang. 2025. "Does Digitalization Mean Equality? Digital Finance and Balanced Development Between Counties" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188276

APA StyleGan, C., Sun, X., Voda, M., & Wang, K. (2025). Does Digitalization Mean Equality? Digital Finance and Balanced Development Between Counties. Sustainability, 17(18), 8276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188276