1. Introduction

Qatar is currently allocating substantial resources toward developing contemporary urban public transport systems, including the Doha Metro, Light Rail Transit (LRT), and Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) networks. These projects are particularly significant in light of Doha’s rapid economic expansion and urbanization over the past three decades. Globally, researchers and decision-makers are progressively advocating for transit investments and Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) as essential approaches to promote sustainable and environmentally resilient urban lifestyles.

By concentrating relatively high-density, mixed-use developments near transit nodes within walkable surroundings, TODs aim to reduce dependence on private vehicles, thereby mitigating traffic congestion, lowering fossil fuel use, and reducing carbon emissions. In the context of Qatar’s urbanization trajectory, the TOD planning model is considered particularly relevant and beneficial [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

A critical determinant of long-term TOD success lies in the integration of transit systems with surrounding land uses, ensuring they effectively reduce car dependency and attract ridership. Over two decades of TOD research have consistently emphasized the importance of the so-called ‘3 Ds’: Design, Density, and Diversity of land use in station areas [

9,

10,

11,

12]. High-quality urban design—regardless of whether stations are elevated, underground, or situated along medians or in mixed-traffic corridors—is essential. Successful stations are characterized not only by accessibility and safety but also by the presence of vibrant, inclusive, and socially engaging public spaces.

Well-functioning TODs typically support dense, walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods with seamless pedestrian connectivity, ample sidewalks, and carefully organized street layouts. Such urban environments are not the product of chance; rather, they require meticulous planning and design interventions both before system construction and after project implementation, through post-occupancy evaluation [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Qatar’s targeted investments in transit infrastructure align with its wider national goals of establishing Doha as an international center for services. To achieve this vision, the design of transit stations and planning of their adjacent urban environments are critical for increasing system ridership, enhancing urban quality, and ensuring long-term operational and financial sustainability. Moreover, global evidence suggests that effective integration of transit and land use can lead to increased property values in station-adjacent areas, further incentivizing thoughtful TOD implementation [

1,

14,

17,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

Similarly, Saudi Arabia’s strategic investments in public transit infrastructure form a core component of its broader national agenda under Vision 2030, which aims to diversify the economy, decrease reliance on private vehicles, and enhance urban livability. In Riyadh, the development of the six-line metro network—one of the region’s most ambitious transit initiatives—demonstrates a strong commitment to transforming the city into a more sustainable and globally competitive urban hub. The design and planning of metro stations, together with the urban areas around them, are crucial for promoting public transit use, improving the quality of public spaces, and sustaining the social and economic benefits of these investments over the long term. International precedents affirm that well-integrated transit and land use strategies can significantly boost real estate value and stimulate compact urban growth. As such, the Riyadh Metro, and particularly key nodes like the King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD), acts as a vital catalyst for promoting Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) and establishing a model for future urban revitalization throughout the Kingdom.

This study is based on a comparative examination of two Gulf region case studies: Doha’s West Bay District in Qatar and Riyadh’s King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD) in Saudi Arabia, each exemplifying different strategies for implementing Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) in line with their national urban objectives.

The study focuses on West Bay—Doha’s contemporary Central Business District (CBD) and Qatar’s primary financial and commercial hub—as a key case study for examining TOD implementation [

2,

28]. It seeks to investigate the planning concepts and design standards crucial for successfully creating or revitalizing a transit village in West Bay. Through identifying and examining the core challenges and factors contributing to success, the research proposes a set of planning and design recommendations aimed at enhancing livability, sustainability, social cohesion, and economic vitality within the emerging West Bay Transit Village.

Similar to Doha’s city’s evolution, the capital city of Saudi Arabia, Riyadh, is seeking to undergo a paradigm shift towards a sustainable, inclusive, and integrated city transformation in alignment with the strategic objectives of Vision 2030. To this end, the KAFD is a flagship project and a testbed for implementing TOD principles in a purpose-built, high-density urban node. While West Bay represents a retrofitted urban district undergoing post-development integration of TOD strategies—responding to the challenges of an existing car-oriented layout—KAFD exemplifies a proactive planning approach, where vertical density, multimodal access, and climate-responsive design were embedded from inception. This research captures a comprehensive spectrum of TOD applications in the Gulf Regions by comparing two significant case studies and offering critical insights into how retrofitted and newly planned districts can advance urban livability, sustainability, and mobility through context-specific planning and design strategies.

Despite increasing worldwide adoption of TOD principles in urban planning, their implementation in the specific morphological, socio-economic, and climatic conditions of Gulf cities has yet to occur widely. While much of the published literature discusses TOD in temperate climates, few comparative case studies have examined TOD implementation in hyper-arid climates like Doha and Riyadh, where urban morphology, government, and climatic resilience all play dominant roles.

Gulf cities provide a particularly compelling context for studying TOD because they exhibit distinctive characteristics that set them apart from many other global urban environments. Their rapid urbanization, largely fueled by oil and gas wealth since the mid-20th century, has resulted in car-dependent spatial structures, expansive zoning, and fragmented public realms. At the same time, these cities are shaped by hyper-arid climatic conditions, with extreme heat and scarce water resources posing significant challenges to walkability and outdoor public life. Unlike many temperate-climate contexts where TOD has been extensively studied, Gulf cities demand context-adaptive models that integrate climate-responsive design, shaded and cooled pedestrian environments, and innovative approaches to resource efficiency. Furthermore, strong national visions—such as Qatar National Vision 2030 and Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030—have positioned TOD not only as a mobility strategy but also as a catalyst for economic diversification, global competitiveness, and sustainable urban transformation. These unique combinations of climatic, socio-economic, and governance conditions make Gulf cities particularly suitable and necessary testbeds for examining how TOD principles can be reinterpreted and localized to enhance livability in hot-desert Urbanism.

For instance, Furlan and Almohannadi [

29] demonstrated how Light Rail Transit (LRT) integration in Doha’s Al-Qassar district catalyzed compact, mixed-use development supported by shaded pedestrian linkages and climate-adaptive public realm strategies. Similarly, Jarrar and Al-Homoud [

30] examined Riyadh’s projected walkability model, stressing the importance of shading, thermal comfort, and active transport networks as prerequisites for successful TOD implementation in desert environments. These precedents underscore that TOD in arid cities requires not only high-density, transit-proximate development but also microclimatic responsiveness and culturally sensitive urban design. By building on such regionally relevant studies, this research positions West Bay and KAFD within a growing body of knowledge on how TOD principles can be adapted to the climatic and socio-economic realities of Gulf cities.

This paper tries to fill this gap by examining, in part, the following main research questions:

In what ways do TOD approaches affect urban livability in purpose-built compared to retrofitted high-density districts in Gulf cities?

To what extent are TOD principles such as land use diversity, walkability, and transit integration realized in West Bay and KAFD?

How do climatic constraints and planning legacies affect the operationalization of TOD in each context?

What spatial and policy strategies can enhance TOD effectiveness in arid urban environments?

By addressing these questions, the research aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of how TOD can be adapted to support sustainable urban transformation in the Gulf.

Beyond their immediate significance for Doha and Riyadh, the findings of this study hold broader implications for advancing global sustainability discourse. As climate change intensifies and arid regions worldwide grapple with resource constraints, extreme temperatures, and rapid urbanization, lessons from Gulf cities offer transferable insights into how transit-oriented planning can be adapted to environmentally challenging contexts. By examining both retrofitted and purpose-built TOD models, this research provides comparative evidence that can inform not only Middle Eastern urban strategies but also similar efforts in North Africa, Central Asia, and other rapidly growing hot-climate cities. More broadly, the study contributes to the international sustainability debate by emphasizing that TOD success depends on coupling transit integration with climate-responsive design and socio-cultural adaptability—principles increasingly vital for creating resilient, inclusive, and livable cities in diverse global contexts.

2. Literature Review

2.1. From Principles to Practice: Integrating Sustainable Urbanism and TOD in the Qatari and Saudi Contexts

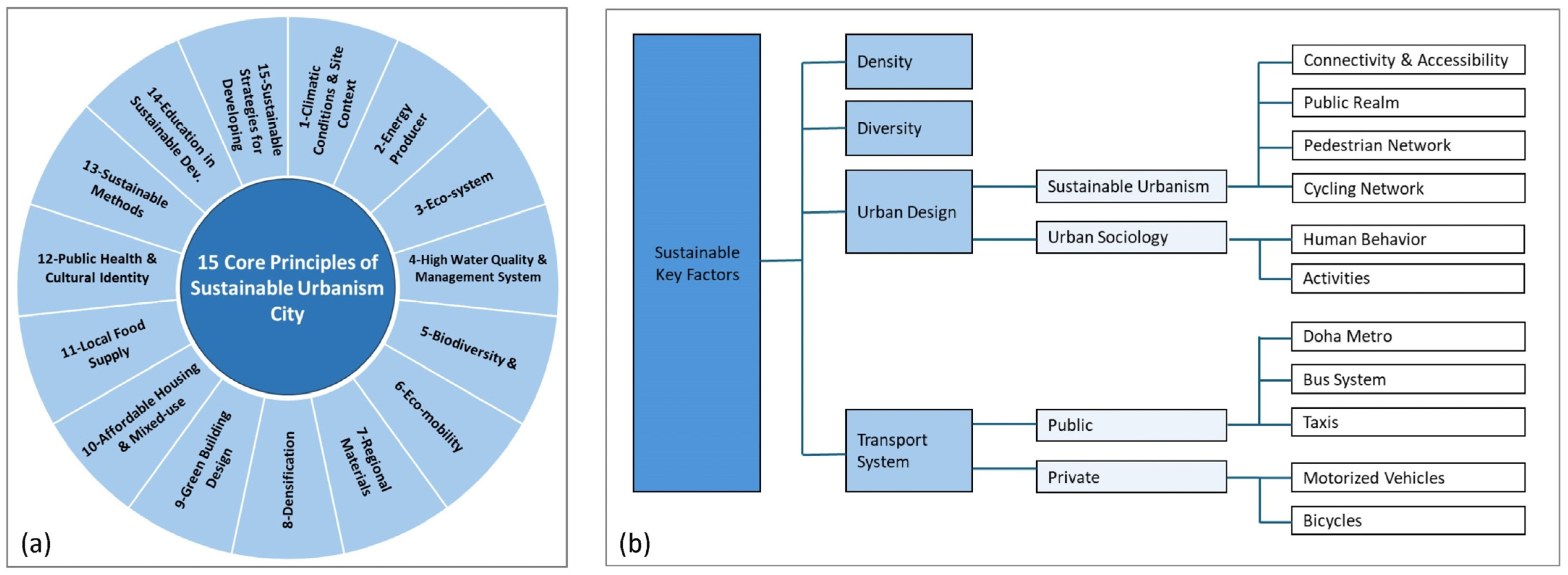

The study is structured around fifteen core principles of sustainable Urbanism, which serve as its conceptual framework. These principles help identify the essential factors, concepts, variables, and their interconnections (

Figure 1a), offering clarity and direction for understanding the phenomena being examined.

The “fifteen core principles of sustainable urbanism” adopted in this study originate from established theoretical frameworks developed by Lehmann [

31] and later expanded by Farr [

16]. These principles consolidate key dimensions of environmental performance, livability, social equity, and urban form, and they have been widely referenced in sustainability and planning literature as benchmarks for evaluating sustainable development strategies. Their selection for this study responds to their comprehensive scope and proven applicability across diverse contexts, offering a robust lens for assessing the integration of transport and land use in Gulf cities. By situating TOD within this established framework, the analysis ensures comparability with international sustainability discourse while adapting the principles to the specific climatic and socio-cultural conditions of Doha and Riyadh.

Contemporary scholars emphasize the need to form or regenerate neighborhoods and cities by focusing on five overarching objectives:

(1) Improving livability,

(2) Fostering community,

(3) Broadening opportunities,

(4) Promoting equality,

(5) Advancing sustainability.

Designing and planning sustainable cities, villages, and communities is seen as crucial for humanity’s future, ensuring that today’s needs are met without jeopardizing those of future generations [

14].

Sustainable Urbanism is increasingly seen as an effective strategy for addressing the environmental and ecological impacts of climate change. The regeneration of neighborhoods or the formation of new transit-oriented communities must therefore follow an interdisciplinary planning approach—one that can flexibly respond to shifting demographic, environmental, social, and economic factors. As illustrated in

Figure 1a, this planning model is based on fifteen interconnected core principles and is rooted in the “triple-zero framework,” which aims for zero fossil fuel consumption, zero waste production, and zero emissions [

31]. In hyper-arid climates such as those of Doha and Riyadh, the application of TOD principles faces distinct constraints and opportunities. Extreme heat limits walkability and outdoor activity, requiring climate-adaptive measures such as shaded pathways, cooling strategies, and compact urban form to support pedestrian movement. Water scarcity also constrains the integration of green infrastructure, demanding innovative approaches to landscape design and resource efficiency. At the same time, TOD offers significant opportunities in these contexts by reducing car dependency, lowering energy demand for cooling through compact land use, and fostering sustainable mobility. This study engages with these dual challenges and potentials, examining how TOD frameworks can be adapted to enhance livability and resilience in hyper-arid urban environments.

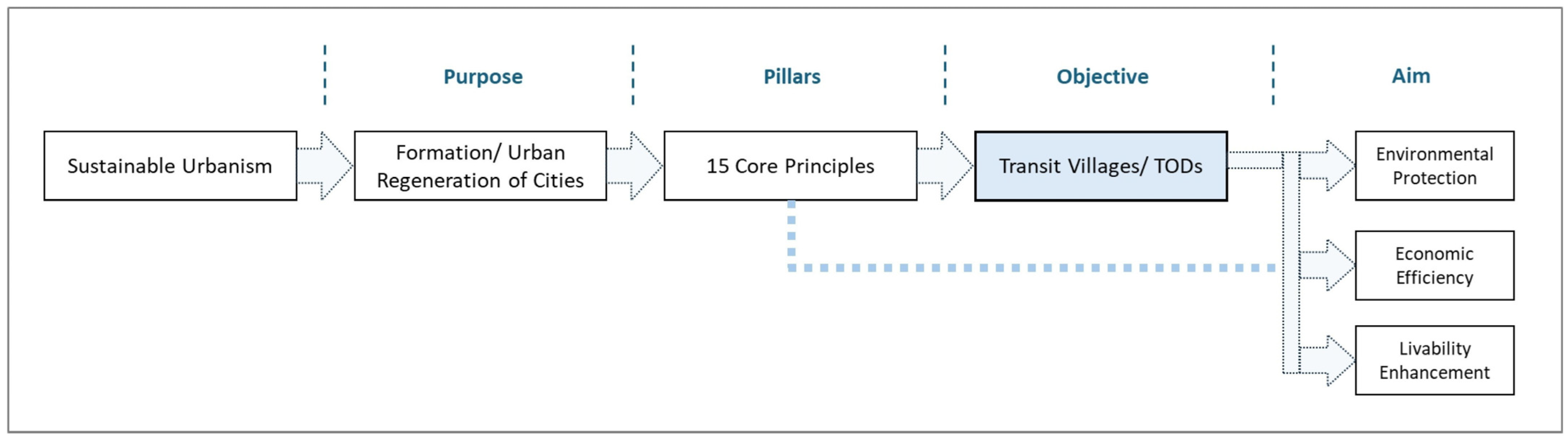

This approach enables both the conceptual modeling of sustainable urban development to address current urban challenges and the physical implementation of transit villages that are integrated with public transportation infrastructure. In this context, Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) strategies aim to:

(A) Achieve eco-mobility through low-impact public transport systems,

(B) Offer well-designed, livable spaces,

(C) Establish replicable models for future eco-cities [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

These insights, which initially emerged in response to urban challenges in North America and Europe—such as traffic congestion, rising oil prices, and sprawling metropolitan growth—are increasingly relevant to the context of the State of Qatar. Facing similar urban pressures, Qatar has invested more than

$36 billion in public transportation infrastructure to guide its rapid urban expansion while also promoting a vision of sustainable Urbanism. This vision supports not only growth, but also the regeneration of Doha, Riyadh, and other cities (

Figure 2).

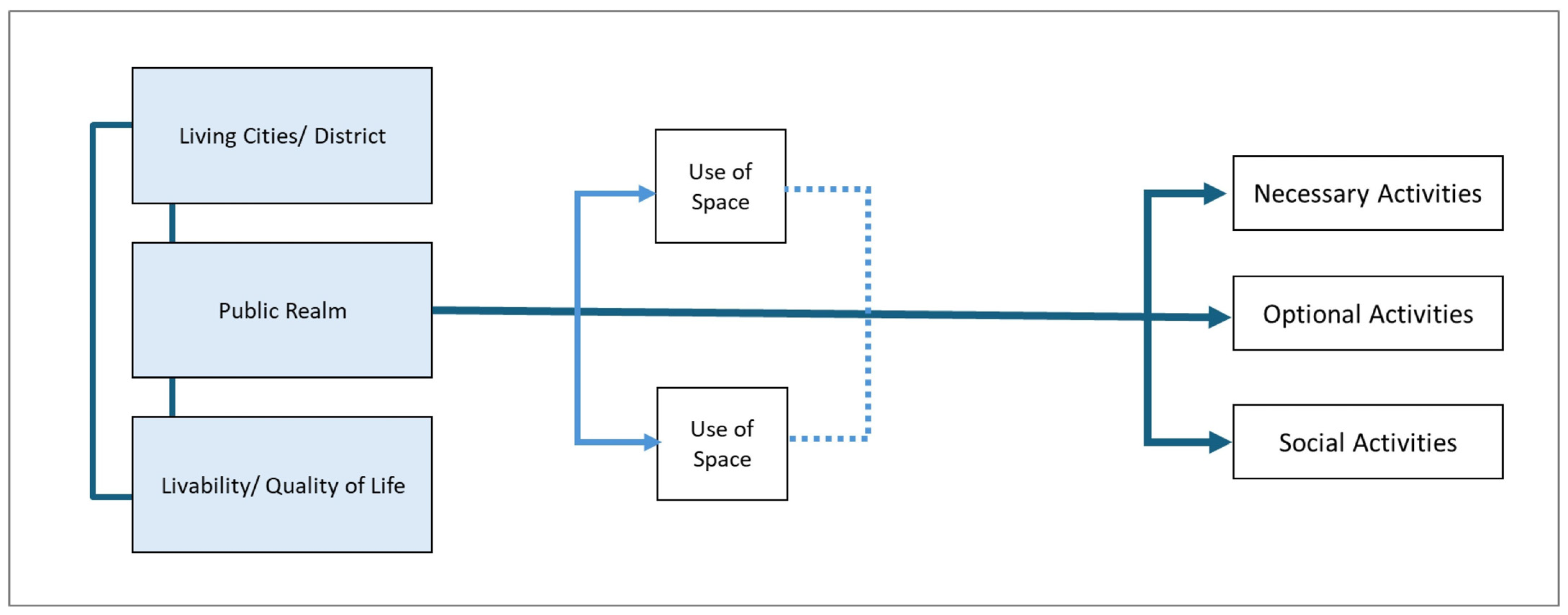

2.2. Urban Sociology and the Built Environment: Designing Public Spaces for Livable TODs

Urban sociology focuses on understanding urban societies, specifically the social dynamics that occur in the spaces between buildings. Urban sociologists investigate the qualities of public spaces that have historically been linked to social interactions in urban areas, considering these spaces as key elements in urban design and town planning. Altering the physical structure of urban environments is seen as vital for enhancing the public realm, as it has a direct effect on livability and overall quality of life [

37,

38]. Although societies worldwide have evolved due to growth and modernization, urban sociologists maintain that the fundamental principles for improving public space quality have remained stable over time. Gehl emphasizes that the design of outdoor spaces significantly shapes human behavior, noting that the quality of such spaces strongly affects both (a) how frequently people use them and (b) their social importance [

39,

40,

41].

Gehl’s emphasis on public space quality for social cohesion [

40] (

Figure 3).

Gehl’s framework suggests that public spaces in urban areas should be designed to facilitate social connections, with areas where gatherings and spontaneous interactions can occur. Such spaces foster vibrant cities where people can connect, in contrast to automobile-centric cities, which often lack opportunities for interaction.

The development of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) villages along public transport systems aligns with a broader vision for urban regeneration, aiming to improve livability and quality of life while reducing the prevalence of sprawling, car-dependent districts. TODs create vibrant, interactive spaces by integrating residential, commercial, and public spaces within walking distance of transit stations. These areas are designed to promote eco-mobility, reduce reliance on cars, and encourage social interactions. In contrast to lifeless, automobile-oriented urban environments, TODs are carefully planned to facilitate community building and social connection [

33,

42,

43].

TODs are seen as opportunities to cluster employment, boost transit usage, and strengthen the sense of place surrounding transit hubs. Effective TODs incorporate public features like seating, greenery, parks, and plazas, which support social interactions and community services [

10].

To ensure that TODs foster livable spaces and a strong sense of community, urban planning needs to address not only the physical design of the environment but also the social, economic, and cultural dimensions of everyday life. This is particularly relevant for TOD planning in Qatar, where urban development must respond to human behavior and the community’s social dynamics [

2,

28]. Sustainable Urbanism provides the overarching conceptual framework, emphasizing environmental responsibility, social equity, and economic efficiency. Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) operationalizes these principles through the “3 Ds”—Density, Diversity, and Design—fostering compact, mixed-use, and pedestrian-friendly districts [

11,

12]. Complementing this, urban sociology underscores the importance of public space quality and human interaction, with Gehl [

39,

40] demonstrating how well-designed environments enhance social cohesion and livability. Together, these frameworks establish TOD not only as a transport and land use strategy but also as a vehicle for creating inclusive, sustainable, and socially vibrant neighborhoods, particularly when adapted to arid urban contexts such as Doha and Riyadh.

2.3. Doha 2032: Navigating Growth Through National Planning and Urban Infrastructure

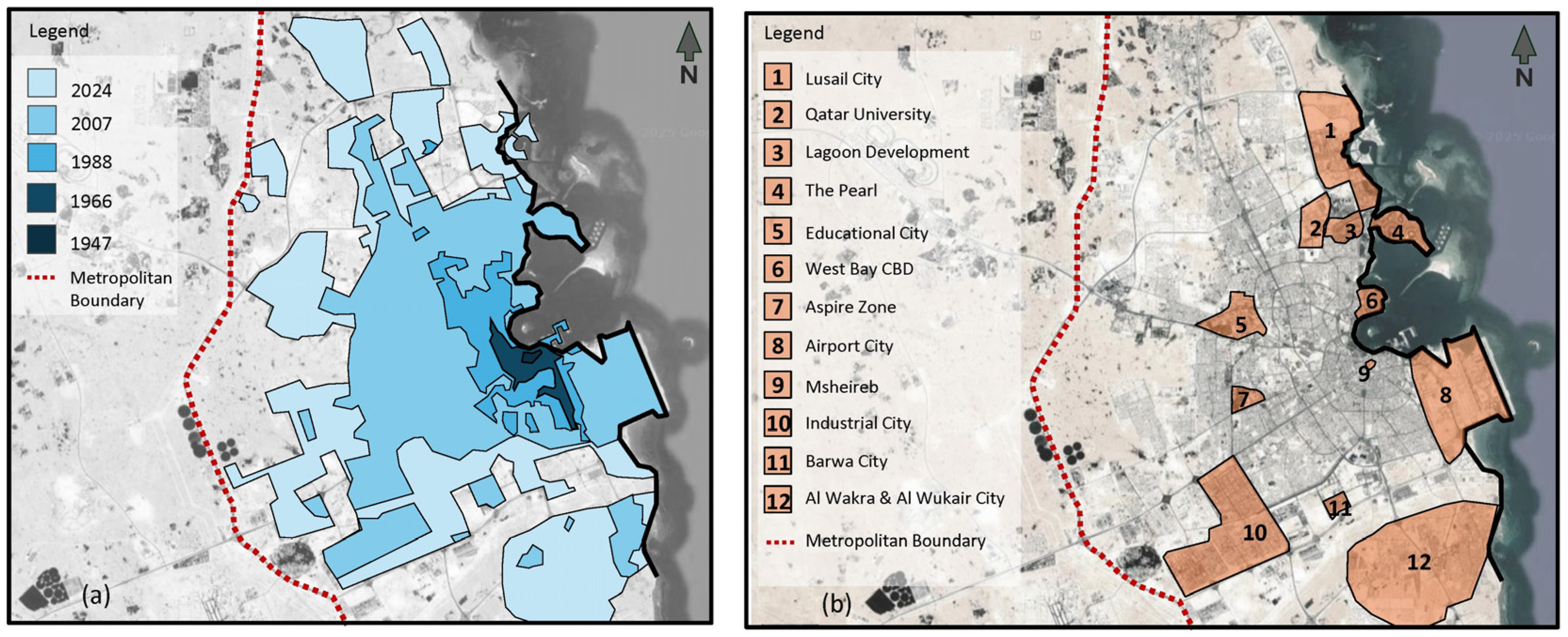

Doha, among the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)’s oldest cities, has undergone a remarkable transformation since the mid-1970s.

Today, Qatar stands as one of the fastest-growing economies in the Middle East (

Figure 4), particularly in the construction sector [

44].

A core driver of these developments has been the Qatari leadership’s vision to establish the country as an economic ‘powerhouse’ in the region. This ambition has materialized through mega-projects such as stadiums and sports facilities for the World Cup, the establishment of international seaports to enhance tourism and commerce, extensive improvements to urban infrastructure and services, and the creation of smart cities such as Lusail.

However, without a unified national planning framework, the rapid urbanization driven by these mega-projects has also given rise to several urban challenges—ranging from inflated land values and housing affordability issues to traffic congestion and environmental degradation. To address these concerns, the Ministry of Municipality and Urban Planning (MMUP) introduced the Qatar National Development Framework (QNDF-2032) in 2011. This comprehensive strategy was designed to guide urban growth, land use, and development in alignment with (QNV-2030)—a long-term strategy focused on establishing a sustainable and thriving society for both present and future generations [

45] (

Figure 5).

QNDF-2032 encompasses a range of planning tools, including the National Master Plan, Municipal Structure Plans, Action Area Plans for city and town centers, zoning regulations, and urban design guidelines. It identifies key challenges such as air pollution (caused by car dependency), traffic congestion (due to limited public transport), and urban fragmentation. It also addresses broader concerns, including the decline of smaller settlements, inefficient energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, food insecurity, and the degradation of natural and urban environments.

As part of this framework, Qatar is investing heavily in transforming its urban mobility landscape. Major public transportation networks—including the Doha Metro, Lusail Light Rail Transit (LRT), and Bus Rapid Transit (BRT)—are either under construction or in operation, to be fully functional before the 2022 FIFA World Cup. These initiatives are not only intended to facilitate large-scale event logistics but also to support the long-term integration of economic, environmental, and socio-cultural priorities [

29,

46,

47,

48].

The Doha Metro, in particular, is a cornerstone of this urban mobility transformation. It aims to connect key locations, including Hamad International Airport, Doha Port, major stadiums, urban districts, and residential hubs (

Figure 6). Once complete, the network will comprise four lines totaling 300 km and 98 stations, incorporating underground, at-grade, and elevated tracks:

This transport infrastructure is seen as pivotal not only for managing congestion and environmental concerns but also for enhancing urban livability and spatial integration [

3,

4,

36,

46,

49,

50,

51].

The Qatar National Master Plan (QNMP) 2032 provides a strategic roadmap for both short- and long-term urban development. According to the plan, all major infrastructure projects—including highways, railways, Metro, and new residential developments—are to be completed by 2026. The QNDF Spatial Strategy outlines a hierarchical urban structure, positioning West Bay, Airport City, and the Government District at the heart of Metro Doha. These hubs are interconnected via orbital transit corridors linking dense, mixed-use urban and town centers.

To ensure food security and environmental stewardship, an agricultural belt is envisioned to contain urban sprawl. A central focus of the strategy is coordinating land use with transportation planning, an essential step for alleviating congestion and promoting job opportunities.

The plan emphasizes livability, identity, and integration of existing and future mega-projects. It promotes compact urban form through higher densities, mixed-use development, and a clearly defined hierarchy of centers. Furthermore, it encourages the strategic utilization of underdeveloped land within the metropolitan region to create a more sustainable and efficient urban morphology.

In conclusion, the development of the Doha Metro and related transit-oriented infrastructure presents a unique opportunity to design, regenerate, and connect vital urban precincts—laying the foundation for a more livable, sustainable, and resilient city.

2.4. Reimagining Urbanism in the Gulf: The Development and Challenges of West Bay, Doha

West Bay emerged as Doha’s showcase the Central Business District (CBD) with its modern high-rises and iconic structures. Despite its symbolic role, the district has fragmented public space, static tower bases, and limited pedestrian connectivity [

28,

47,

49,

52,

53,

54]. As a TOD node, it places great stress on retrofit strategies such as shaded walkways, infill, and diversification of land use (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8).

Today, West Bay’s striking skyline stands as an iconic representation of Doha’s architectural ambition [

30,

55,

56,

57] (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10).

Situated along Doha’s red metro line, West Bay has been designated as a major node for Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) (

Figure 11). The recent implementation of the railway network offers significant potential for revitalizing the district, which currently remains underutilized due to inactive open spaces surrounding tower bases, poor pedestrian connectivity, and limited green infrastructure. To fully harness the benefits of TOD, the regeneration of West Bay requires a comprehensive and inclusive design strategy that prioritizes livability, social engagement, and vibrant public life.

2.5. Riyadh 2030: Shaping Urban Futures Through Transit Integration and Vision-Led Development in King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD)

As Saudi Arabia advances its Vision 2030 agenda to transition from a petroleum-based economy to one driven by innovation, tourism, and international investment, its major cities are undergoing rapid and strategic transformations [

30,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63]. The KAFD stands out as a centerpiece of Riyadh’s urban and economic evolution. While Doha’s West Bay reflects a retroactive integration of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) into an existing urban district, Riyadh presents a markedly different trajectory that proactively leverages large-scale infrastructural investments to shape future urban growth. Central to this transformation is the Riyadh Metro project, a six-line, 176 km network with 85 stations, which serves as the backbone of the city’s multimodal mobility strategy (

Figure 12).

The Riyadh Metro anchors Vision 2030’s mobility strategy, with the King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD) as its central TOD hub. Purpose-built, KAFD combines high-density vertical development with multimodal access through metro, monorail, and skywalk systems. However, evidence highlights persistent challenges such as limited climatic comfort, weak ground-level activation, and insufficient active mobility. The iconic metro interchange station, automated people movers, and vast network of subterranean roads are all set up to reduce the city’s traffic and improve walkability. Although it is adapted to the particular socio-political and climatic conditions of the Gulf, this spatial logic reflects more general worldwide tendencies in sustainable city-making. KAFD shows that the nation’s priorities are much more than a building construction project. It manifests Saudi Arabia’s dedication to integrating compactness, international economic connectivity, and environmental performance as part of its new urbanization paradigm. Unlike West Bay, where TOD principles must be retrofitted into a fragmented urban fabric, KAFD exemplifies a comprehensive vision where transit infrastructure, land use diversity, and urban form are co-developed from the outset (

Figure 13). However, both cases face similar climatic and socio-cultural constraints that complicate the application of TOD models designed for temperate contexts [

55]. While more systematically integrated, Riyadh’s approach must still address micro-scale issues such as walkability in extreme heat, shading, thermal comfort, and creating vibrant, inclusive public spaces. The comparison between KAFD and West Bay thus illustrates two distinct but complementary pathways toward sustainable Urbanism in the Gulf: one shaped by adaptive retrofitting, the other by pre-planned integration. Together, they offer a nuanced understanding of the region’s evolving urban strategies and the operationalization of TOD as a tool for livability, economic diversification, and environmental resilience.

Within this transformative context, Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) emerges as a central planning strategy, offering a cohesive framework that integrates land use with transportation infrastructure to promote sustainable urban growth [

64]. While originally conceptualized by scholars such as Cervero [

65] as the development of compact, pedestrian-oriented communities organized around high-capacity transit systems, the application of TOD has evolved substantially in recent years. Contemporary studies have expanded this framework across varying geographies and planning contexts. Zemp et al. (2011) demonstrated how TOD contributes to increased transit ridership and spatial efficiency [

66]. Vale (2021) [

57] emphasized the importance of walkability metrics in assessing TOD success, particularly in mixed-use districts and

examined the equity implications of TOD in Lisbon, showing how well-planned transit hubs can reduce car dependence while promoting inclusivity. Similarly, Atkinson-Palombo & Kuby (2011) [

67] evaluated light rail TOD zones in the United States, highlighting the role of station design and accessibility in determining neighborhood-level outcomes. Most recently, a comparative content analysis of high-speed railway station areas in China illustrated how TOD principles have been selectively localized [

67] to promote compact urban growth, though with varying adherence to best practices and notable deviations from internationally established TOD frameworks [

68].

2.6. The King Abdullah Financial District in Riyadh: Challenges and Opportunities

An extraordinary test location for TOD implementation is Riyadh, a city that is typically organized on private car use and an extensive zoning approach to urban development. In recent decades, Riyadh’s hot temperature, low historical emphasis on pedestrian infrastructure, and deeply entrenched vehicle reliance have made it difficult to create walkable, transit-oriented surroundings. However, the Riyadh Metro’s six-line network signals a shift toward multimodal urban planning. The KAFD, situated at the convergence of multiple metro lines and featuring a landmark interchange station, represents the most concentrated effort to translate TOD principles into practice. With its underground vehicle network, automated people mover system, and layered spatial zoning (

Figure 14a), KAFD provides a controlled environment where global TOD models can be examined under localized constraints. The district’s integration of vertical density, architectural distinction (

Figure 14b), and multimodal access enables a critical investigation into how symbolic infrastructure and strategic planning coalesce in state-driven development.

2.7. From Literature Gaps to Research Questions

While TOD has been extensively examined in temperate and high-density contexts [

12,

69,

70], little research addresses its adaptation to hyper-arid Gulf environments where extreme heat and car-dependence prevail. Comparative studies are scarce, particularly between retrofitted districts like West Bay and purpose-built enclaves [

71] such as KAFD [

66,

69]. Furthermore, although Qatar’s QNV-2030 and Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 promote TOD, their translation into lived urban form and public realm quality remains underexplored. Existing studies tend to focus either on post hoc retrofits in established urban cores or on newly planned districts, but rarely juxtapose both trajectories to evaluate their relative successes and challenges in advancing livability. This leaves unanswered how TOD principles perform differently when applied to fragmented, car-oriented districts such as Doha’s West Bay compared with purpose-built, transit-integrated enclaves like Riyadh’s KAFD.

Finally, the literature does not sufficiently explore the role of governance frameworks and national visions in shaping TOD outcomes in the Gulf. While documents such as Qatar National Vision 2030 and Saudi Vision 2030 explicitly link TOD to sustainability and economic diversification, little empirical evidence exists on how these high-level strategies filter down into spatial design, public realm quality, and day-to-day livability.

These research gaps directly frame the core questions guiding this study, presented in the introduction:

In what ways do TOD approaches affect urban livability in retrofitted versus purpose-built high-density districts in Gulf cities?

To what extent are TOD principles—such as land use diversity, walkability, and transit integration—realized in Doha’s West Bay and Riyadh’s KAFD?

How do climatic constraints, planning legacies, and governance frameworks shape the operationalization of TOD in these contexts?

By addressing these questions, the study contributes to extending the TOD discourse into hyper-arid regions. It offers comparative evidence on how context-adapted TOD strategies can enhance livability in Gulf cities and other rapidly urbanizing arid environments.

By directly linking these research questions to the identified literature gaps, this study positions itself to extend TOD discourse into underexplored Gulf contexts, offering comparative evidence on how TOD models can be localized to improve urban livability in hyper-arid environments.

3. Methodology: The Research Design

Urban design focuses on envisioning and planning collections of buildings, street networks, and public spaces that together create the structure of neighborhoods, districts, and the broader urban environment. It addresses the needs of people, influenced by various factors such as lifestyles, human behavior, and activity patterns. Ultimately, urban designers aim to transform urban spaces into places that are more livable, practical, visually appealing, and sustainable.

As a result, urban design is inherently interdisciplinary, drawing on knowledge from a wide range of fields—including urban planning, economics, engineering, and the social sciences. Equally critical is the integration of insights gathered from users and stakeholders, whose perspectives help shape-built environments that truly serve people’s needs. A comprehensive understanding of how users interact with the built environment—and of the mechanisms linking spatial design to human behavior—enables urban designers to create environments that foster vitality and quality of life [

70,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80].

This research seeks to critically examine and assess the current urban conditions of West Bay, Doha’s contemporary Central Business District, in comparison with Riyadh’s King Abdullah Financial District through the lens of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) principles. The goal is to compare and formulate a strategic vision for the regeneration of the two districts, enhancing their livability for a diverse spectrum of users. To achieve this, the research adopts a two-pronged approach.

3.1. Conceptual and Policy Framework

A comprehensive literature review is conducted to examine the interdisciplinary context of Sustainable Urbanism, Urban Sociology, and transit village models, with a focus on their applicability within the framework of the Qatar National Development Framework (QNDF 2032). Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, supported by the National Spatial Strategy, the Riyadh Strategic Plan, and TOD-oriented policies led by the Royal Commission for Riyadh City’. This review facilitates the identification of key TOD criteria, including land use diversity and density, urban design quality, connectivity, walkability, the character of the public realm, and the integration of transportation systems.

The interdisciplinary literature review directly informed the subsequent case study analyses by establishing the evaluative criteria and analytical lenses applied to both West Bay and KAFD. Insights from sustainable urbanism theory guided the selection of TOD indicators such as density, land use diversity, and environmental responsiveness. At the same time, urban sociology contributed perspectives on the role of public space and social interaction in assessing livability outcomes. Furthermore, planning scholarship on Gulf cities highlighted the importance of climate adaptation and governance frameworks, shaping the way spatial, policy, and design variables were examined in each case. By integrating these diverse strands of knowledge, the literature review provided a robust foundation for interpreting empirical findings, ensuring that the case study assessments were not only descriptive but also theoretically grounded and aligned with broader sustainability discourse.

3.1.1. Case Study Exploration: West Bay

The selected case study involves a detailed examination of West Bay. Oral data is collected through focus groups and semi-structured interviews with experts such as urban designers, planners, and social scientists, including representatives from the Ministry of Municipality and Environment (MME), Ashghal (Public Works Authority), and Qatar Rail (QR) (

Figure 15).

Visual data is collected via historical maps, cartographic resources, architectural drawings, site observations, and photographic documentation, facilitating a comparative spatial analysis of the district’s evolution. The overall research design adopted for this study follows a two-stage methodology, combining theoretical investigation with empirical analysis to address the study’s central objective: the formulation of strategies for the regeneration of West Bay’s Transit-Oriented Development (TOD), with a focus on enhancing urban livability.

3.1.2. Case Study Exploration: King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD)

The second case study centers on Riyadh’s King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD), a purpose-built urban core developed to embody Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 objectives. This analysis draws from planning documents, urban master plans, and official data released by the Royal Commission for Riyadh City, in addition to site surveys and observational data. The study also engages with interviews from regional planning experts and stakeholders involved in infrastructure implementation. The methodological approach integrates visual and spatial analysis based on satellite imagery, mobility plans, land use diagrams, and metro network overlays to assess how TOD principles are operationalized in KAFD. Special attention is paid to the functional relationships between the Riyadh Metro interchange station (Yellow, Blue, and Purple Lines), skywalk systems, and mixed-use programmatic layers distributed across the district’s high-density vertical urban form.

The KAFD case offers insights into how new districts can integrate climate-adaptive design, transit intermodality, and economic symbolism within a singular spatial entity. The research identifies both strengths—such as strategic location and transit convergence—and limitations, notably regarding walkability, outdoor comfort, and socio-spatial inclusivity, making it a pivotal site for evaluating the translation of TOD from theory into practice in arid urban contexts.

3.2. Stage 2: Data Collection

Case Studies: Comparisons of West Bay (Doha’s Contemporary Central Business District) with King Abdullah Financial District in Riyadh

The second stage focuses on a comprehensive case study of West Bay in comparison with the King Abdullah Financial District.

Oral data for Wast Bay is collected through focus groups and semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders, including urban designers, planners, and social scientists from institutions such as the Ministry of Municipality and Environment (MME), the Public Works Authority (Ashghal), and Qatar Rail (QR). Oral data for King Abdullah Financial District is collected through focus groups and semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders, including urban designers, planners, transport engineers, and policy advisors from institutions such as the Royal Commission for Riyadh City (RCRC), Riyadh Metro Project Office, and the Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs and Housing (MoMRAH).

These discussions explore institutional coordination, TOD policy implementation, transit infrastructure integration, and challenges in ensuring pedestrian comfort and mixed-use balance. Complementing this, visual data are obtained from master plan documentation, metro network schematics, on-site field observations, and spatial mapping tools, allowing for a comparative spatial analysis of KAFD’s evolution and alignment with TOD principles.

In addition to expert interviews and focus groups, oral data collection also included user surveys to capture the everyday experiences of residents, commuters, and employees within West Bay and KAFD. These surveys gathered perceptions on walkability, accessibility to transit, comfort of public spaces, and overall satisfaction with the urban environment. By incorporating user perspectives alongside expert insights, the survey results enhanced the validity of the case study analyses, ensuring that the evaluation of TOD performance reflected not only planning and design intentions but also the lived experiences of district users.

This case provides insight into how new urban centers can be designed from inception to accommodate high-density, multimodal, and climate-adaptive development, while also highlighting the operational and social challenges in translating TOD from planning into practice.

While the primary focus of this research is on West Bay in Doha and KAFD in Riyadh, the methodology was designed to ensure that findings can be generalized and adapted to other arid urban contexts. By employing a comparative case study approach, the study identifies both shared challenges—such as extreme heat, car dependency, and limited public realm quality—and localized strategies, including climate-responsive design and multimodal integration. These insights are framed within established TOD and sustainable urbanism frameworks, which provide transferable evaluative criteria (e.g., density, diversity, connectivity, and walkability). This approach enables the findings to be interpreted not only as site-specific outcomes but also as evidence-based lessons applicable to other rapidly urbanizing arid cities in the Middle East, North Africa, and beyond.

Visual data is gathered from a range of sources, including historical maps (analyzed through comparative chronological methods), cartographic materials (e.g., site plans), on-site observations, architectural drawings, and photographic documentation.

This mixed-methods approach enables a robust assessment of West Bay’s and King Abdullah Financial District’s existing urban fabric against TOD criteria. The subsequent analysis and discussion inform strategic recommendations aimed at revitalizing the district through more integrated, sustainable, and people-centered design interventions, thereby improving its overall livability.

To strengthen the robustness of the evaluation and move beyond a descriptive SWOT framework, this study employed a comprehensive multi-method approach integrating both quantitative and qualitative dimensions, as summarized in

Figure 16. Alongside SWOT, GIS-based spatial diagnostics were applied to derive measurable indicators such as metro accessibility buffers (400 m and 800 m), TOD proximity classifications, building shape compactness indices, and composite TOD performance scores. These indicators allowed systematic comparisons across density, connectivity, and environmental responsiveness, complementing the broader analytical framework structured around seven established TOD principles—land use diversity, density, connectivity, walkability, public realm quality, transit accessibility, and environmental responsiveness. In parallel, qualitative methods were incorporated to validate and enrich the spatial findings: oral data were collected through expert interviews, stakeholder focus groups, and user surveys, while visual data included historical maps, cartographic sources, site observations, architectural drawings, and photographic documentation. The triangulation of geospatial, oral, and visual evidence not only reinforced the validity of the results but also captured the lived experiences of comfort, walkability, and usability within both case studies. Taken together, these methodological layers establish a rigorous, evidence-based evaluation framework that extends significantly beyond descriptive assessment and ensures a comprehensive understanding of TOD implementation in West Bay and KAFD.

3.3. Site Analysis of the Case Study 1: West Bay in Doha

3.3.1. Diversity

West Bay features a diverse mix of commercial and residential land uses interwoven with public spaces, all set within an urban fabric defined by wide, car-oriented streets. The approximate land use distribution across the district comprises 50% commercial office space, 10% multi-family residential, 15% single-family residential, 15% special use (including hotels and institutional buildings), and 10% dedicated to community infrastructure and open space, as represented in

Figure 17a.

3.3.2. Density

Figure 17b illustrates how density levels are distributed across the studied area. High-density developments cluster along the main southern corridor, largely dominated by commercial uses. Meanwhile, medium-density zones are mostly found in the northern part, where residential buildings prevail. Low-density areas, shown in light grey, correspond to vacant or undeveloped green spaces as shown in

Figure 17b. Additionally,

Figure 17c illustrates the physical state of the current building stock, indicating that only buildings in new or good condition exist within a 400 m radius of the West Bay station.

3.3.3. Street and Pedestrian Connectivity

West Bay is defined by its contemporary high-rise architecture, which establishes a cohesive and striking visual identity when viewed from a distance. Despite this modern skyline, the district suffers from significant shortcomings in pedestrian infrastructure. There is a noticeable absence of shaded walkways, thoughtfully designed streetscapes, and adequate street furnishings. Many roads lack dedicated pedestrian pathways altogether, resulting in unsafe and fragmented pedestrian connectivity across the area (

Figure 18).

3.3.4. Public Realm (Paved and Green Open Nodes)

The area is deficient in small-scale public open spaces integrated into its urban fabric. While Sheraton Park serves as a major green space, it is located approximately 1.3 km away from the new train station, making it less accessible for everyday use by commuters and residents. Furthermore, the few existing green areas within West Bay are primarily ornamental rather than functional, offering limited opportunities for recreation or social interaction. Notably, paved surfaces account for approximately 45% of the district’s total area, highlighting the dominance of hardscape over usable green space as depicted in

Figure 18a.

3.3.5. Cycling Network/Lanes

The site analysis reveals that West Bay lacks dedicated cycling paths. Currently, the only evident cycling infrastructure is found along the Corniche, leaving the district itself disconnected from this network (

Figure 19b). To promote sustainable and active modes of transportation, it is essential to extend and integrate the existing cycling network into a newly planned pedestrian and cyclist infrastructure within West Bay. This can be achieved either by creating safe, dedicated paths separated from major roads or by redesigning existing roads to accommodate shared or exclusive lanes for pedestrians and cyclists.

3.3.6. Public Transport Systems

Qatar aims for a future focused on sustainable urban growth, driven by the development of public transit systems such as the Doha Metro and the nationwide bus network. To realize this vision, it is essential to ensure the seamless integration of these two major systems. A well-coordinated and interconnected transit network will significantly decrease dependence on private cars, improve overall mobility, and help build a more accessible and environmentally sustainable urban environment, as shown in

Figure 19a.

3.3.7. SWOT Analysis (West Bay, Doha)

Strengths

Strategic location as a major transit hub;

Recognized as the contemporary financial and commercial heart of Doha;

Presence of mixed-use buildings offering a combination of residential, office, and commercial spaces.

Weaknesses

Inadequate building setbacks affect the quality of the streetscape.

Insufficient infrastructure, including narrow roads, poorly designed ramps, and degraded street conditions;

Limited pedestrian accessibility, with a lack of sidewalks and safe crossings;

Increased traffic volume due to concentration of commercial and retail functions, dead-end streets reducing connectivity, and insufficient parking spaces;

Overdependence on private vehicles due to limited public transport accessibility.

Green and open public spaces are scarce.

Opportunities

Potential to develop a pedestrian-friendly environment to enhance walkability and urban connectivity;

Introduction and integration of the new transit systems (e.g., Metro and bus) can help alleviate traffic congestion.

Revitalizing the public realm can significantly boost livability and elevate the quality of life for residents, workers, and visitors.

Threats

3.4. Case Study 2: King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD) in Riyadh

Riyadh presents a unique testing ground for TOD implementation due to its extensive zoning and standard automobile-centered design. The city has significant obstacles in creating walkable, transit-oriented settings because of its deeply embedded vehicle reliance, lack of historical emphasis on pedestrian infrastructure, and harsh climate. However, the Riyadh Metro’s six-line network indicates a move toward multimodal urban design. However, the Riyadh Metro’s six-line network signals a shift toward multimodal urban planning. The KAFD, situated at the convergence of multiple metro lines and featuring a landmark interchange station, represents the most concentrated effort to translate TOD principles into practice. With its auto transportation system, spatial zoning on a layer level, and subterranean car network, KAFD presents a context for research on international TOD patterns while maintaining local regulations. With vertical density, architectural differentiation, and multimodal access built into the district, we can examine the co-mingling of symbolic infrastructure and strategic planning with state-led development.

3.4.1. Diversity and Density

KAFD spans more than 1.6 million square meters and embodies a high-density, vertically layered urban typology that combines business, residential, institutional, leisure, and cultural functions within a compact footprint (

Figure 21). This functional mix supports the principles of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) by enabling a live–work–play environment within walking distance of major transit nodes. KAFD’s urban form is deliberately compact, promoting vertical stacking of programs and land use diversity on a plot-by-plot basis—one of the key departures from traditional horizontal zoning in Riyadh’s urban planning.

3.4.2. Connectivity

KAFD is strategically located at the intersection of three Riyadh Metro lines—the Yellow (Line 4), Blue (Line 5), and Purple (Line 6) (

Figure 22)—and includes a flagship interchange metro station designed by Zaha Hadid Architects. The station is also connected by an internal monorail and a long skywalk system joining above-ground-level structures, limiting severe climatic exposure to users. Despite this advanced connectivity infrastructure, walkability at the ground level remains challenging due to climatic extremes and limited active street frontage, indicating the need for improved environmental comfort strategies such as shading and cooling interventions.

3.4.3. Cycling and Network Lines

Cycling infrastructure within KAFD remains minimal and largely symbolic, with only limited internal pathways. However, a major catalyst for broader active travel integration across Riyadh is the ongoing Sports Boulevard project—a 135 km linear park stretching from Wadi Hanifah in the west to Wadi Al Sulai in the east. It includes 220 km of cycling tracks, 135 km of walking trails, and 149 km of equestrian routes, passing in proximity to KAFD and enhancing potential first/last-mile links for district users (

Figure 23). Phase 1 of the Boulevard, now 40 percent complete with 83 km opened, includes a cycling and pedestrian ‘Promenade’ segment and a Cycling Bridge that connects Wadi Hanifah to urban corridors near KAFD. These developments underscore Riyadh’s broader mobility strategy, emphasizing dedicated active travel corridors. However, the challenge remains to connect networks with internal KAFD pathways.

3.4.4. KAFD’s Experience and Pedestrian Realm

While macro-scale TOD metrics such as density, transit proximity, and land use integration offer critical planning insights, the lived experience of transit-oriented districts ultimately hinges on micro-scale urban design. In KAFD, the pedestrian environment is characterized by a distinct duality: architectural grandeur on the one hand and emergent challenges in environmental comfort and spatial usability on the other.

Figure 24 shows that the station’s exterior (a) adopts a parametric, futuristic architectural language emblematic of KAFD’s branding as a global financial node. The sweeping curves and deep façade perforations evoke symbolic sophistication and technological modernity, contributing to the district’s international image and skyline identity.

Inside the station (b), the transit hub extends this visual language into a controlled, air-conditioned interior with ambient lighting, sculptural ceiling finishes, and glazed walls. These interiors provide thermal refuge from the desert climate and ensure seamless passenger movement, aligning well with TOD transit comfort and legibility principles. However, this climatic control is spatially confined, as much of the district still relies on uncovered at-grade access and long outdoor traverses. While spatially efficient, the station’s placement and controlled transitions may inadvertently limit unplanned urban encounters and discourage spontaneous pedestrian use during hot periods.

As can be observed from photographs (c) and (d), the adjacent public space exhibits significant effort to activate the outdoor spaces with open public spaces, tree-lined axes, and outdoor benches. The outdoor areas appear open and coherent, with open views and connections between principal buildings. However, challenges emerge in terms of thermal comfort and pedestrian retention. Despite vegetation efforts, canopy coverage remains sparse, and paved surfaces absorb considerable heat throughout the day. Without robust shade structures or evaporative cooling features, these areas risk underutilization during Riyadh’s extreme summer months, raising concerns about diurnal usability and equity of access.

3.4.5. Integrated Mapping of Urban Components in KAFD

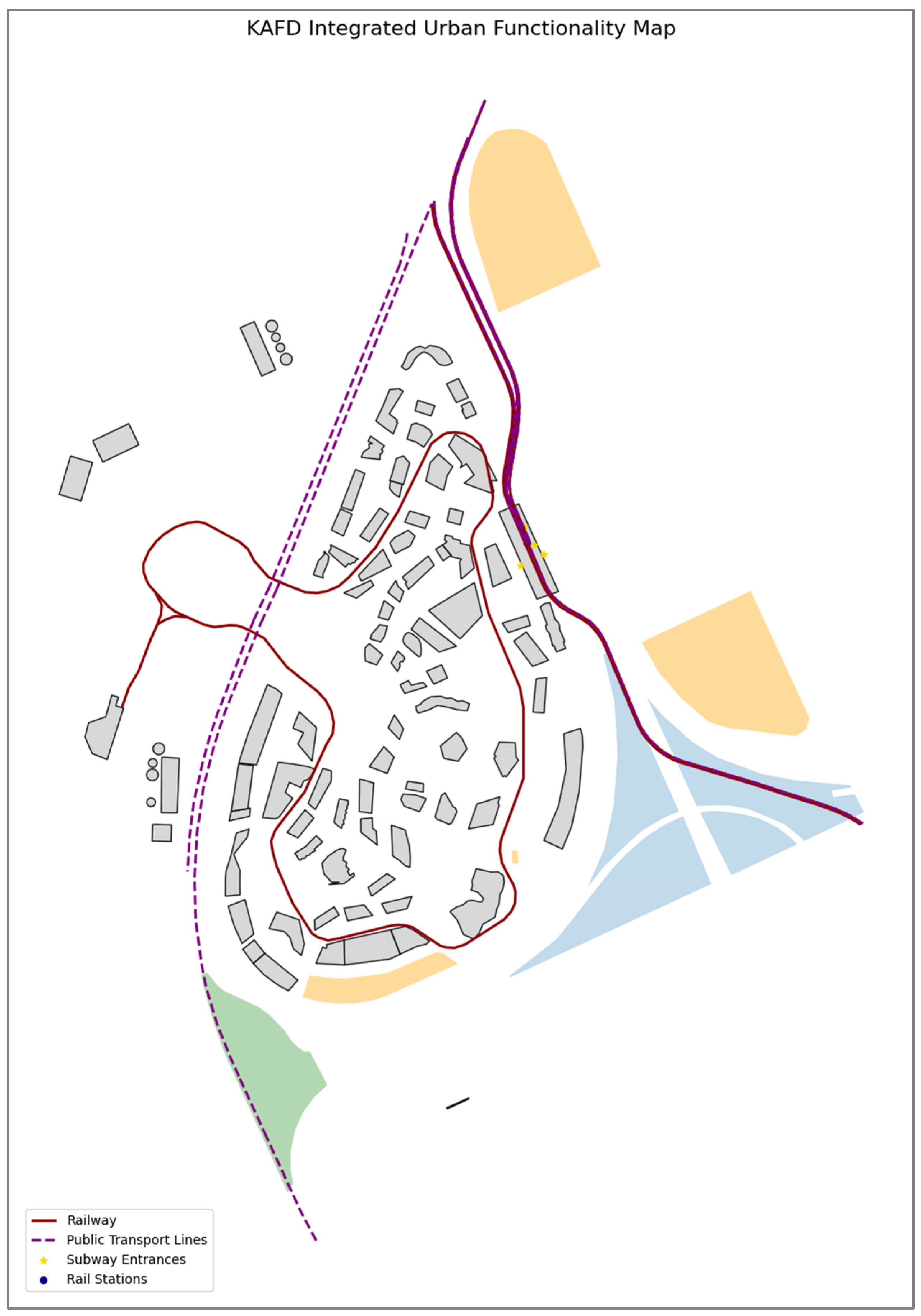

To spatially assess the functional integration of urban elements within KAFD, a composite geospatial map was generated using multiple thematic layers from the NextGIS database. Originally stored as GeoPackage (.gpkg) files, these datasets were reprojected to the Web Mercator coordinate system (EPSG: 3857) for unified spatial analysis. The core layers included buildings, land use typologies, green areas, parking zones, and key transit infrastructure such as metro entrances, railways, and public transport lines. The visual representation, shown in

Figure 25, synthesizes these elements into a single urban functionality map. Grey polygons represent building footprints, overlaid on semi-transparent land use zoning (cmap: tab20c) and vegetation layers. Railway lines and public transport routes are highlighted in red and purple, respectively, while subway entrances and rail stations are marked with distinctive gold stars and blue circles. This figure establishes a base map for subsequent analytical tasks such as TOD scoring, catchment buffer analysis, and morphological assessments, providing an integrated view of land use, mobility access, and built-form distribution within the district.

3.4.6. Evaluating Transit-Oriented Development Metrics in KAFD Through Spatial Analysis

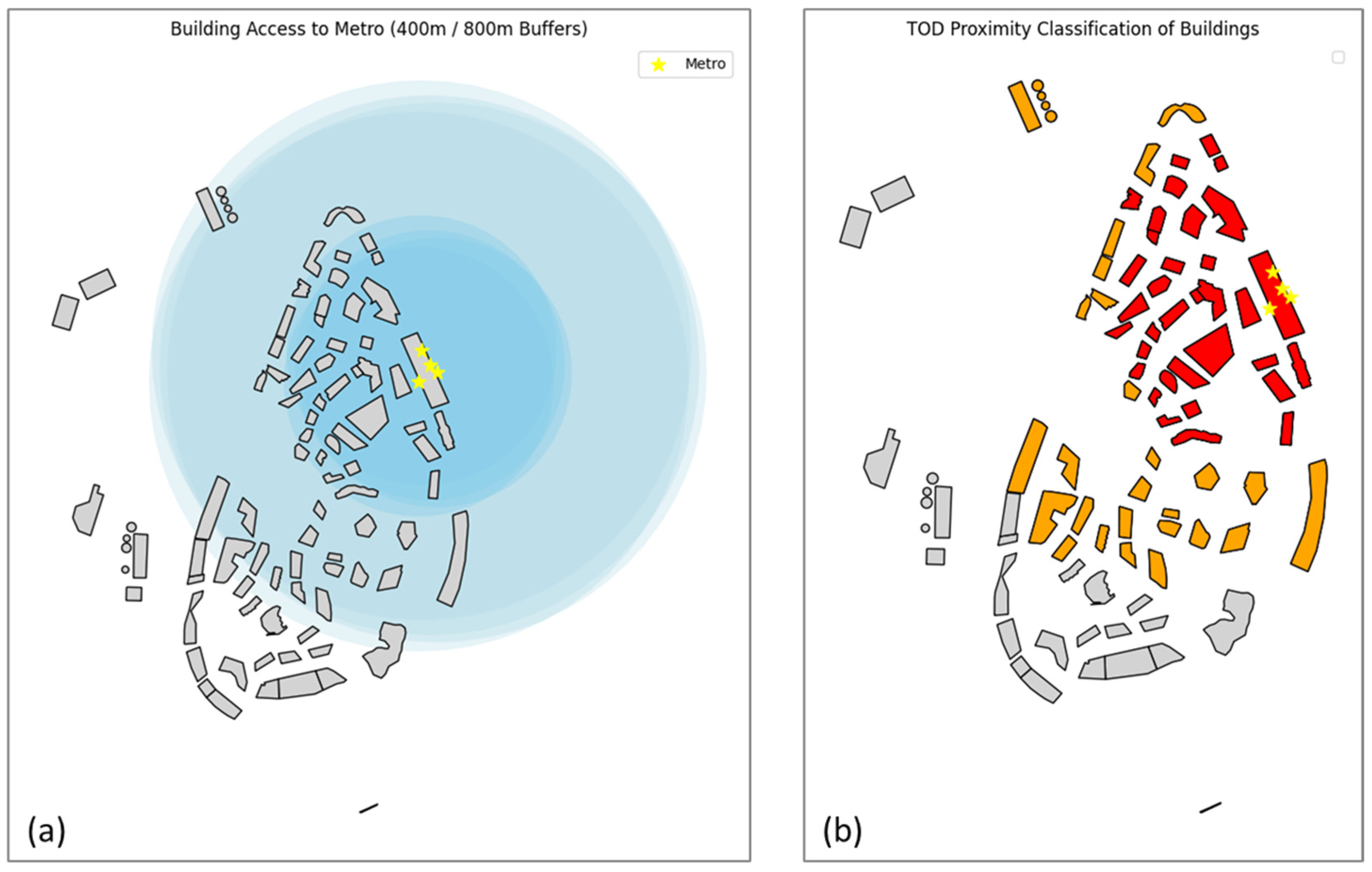

To systematically evaluate the spatial performance of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) within King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD), four key geospatial indicators were derived and mapped: metro accessibility buffers, TOD proximity classification, building shape compactness, and composite TOD score. Using measurable standards relevant to TOD theory, these indicators aid in evaluating the district’s success in combining transportation infrastructure with urban form.

Concentric buffer zones surrounding KAFD’s primary subway entrances are used to map access to the metro infrastructure in the first area of study. Buildings within 400- and 800 m catchment areas—widely accepted cutoff points in TOD studies for walkability and transit access—are shown in

Figure 26a. A high baseline of spatial accessibility is demonstrated on the maps by showing that a significant number of buildings are located within these circles. This facial proximity emphasizes KAFD’s deliberate design focused on transit centers, promoting transit-oriented modes and diminishing car dependency.

In addition to this, another classification places each building within one of three groups based on the distance from the transit center: farther than 800 m (grey), between 400 m (red), or less than 800 m (orange). As seen in

Figure 27b, this TOD proximity classification spatially stratifies KAFD’s building stock, allowing planners to visualize transit alignment intensity. The concentration of red buildings around the central metro cluster demonstrates the district’s success in placing high-density structures closest to transit. This zoning pattern reflects TOD best practices, which advocate for mixed-use density centered around transit to maximize ridership and land value uplift.

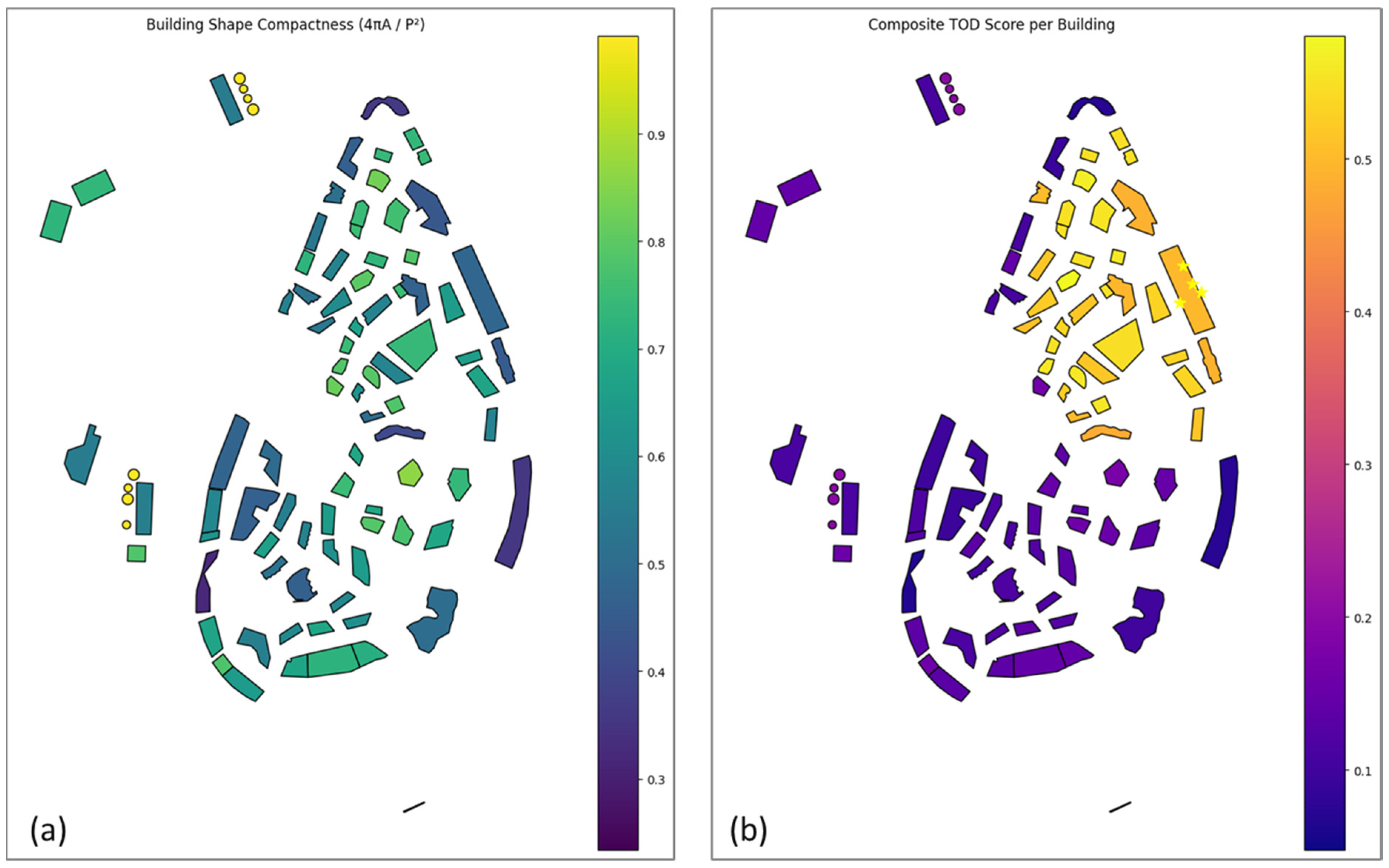

Beyond location, the geometric shape of buildings was analyzed to evaluate thermal and spatial efficiency. Shape compactness is revealed in

Figure 27a with the circularity ratio formula

, with building footprint area, A, given as square meters, and building perimeter, P, given in meters. Values close to the number 1 are more energy-efficient and compact ideas. Value distribution exhibits a geographical variation in geometry performance within the region. Irregular building concepts (blue and purple) may have thermal inefficiencies, especially within a desert climate like Riyadh, as solar irradiance imposes cooling loads. In addition to supporting sustainability evaluations, this map serves as a crucial foundation for upcoming design interventions that emphasize passive design techniques.

The final physical metric creates a composite TOD score by combining the previous layers. This score includes shape compactness (20%), distance to green space and points of interest (20%), and accessibility to the Metro (weighted 40%).

Figure 27b represents a continuous distribution of TOD performance across the district, with buildings closest to transit and exhibiting compact forms achieving the highest scores (yellow tones). This composite measure facilitates nuanced comparisons and ranking of buildings based on their TOD alignment, enabling targeted interventions to improve weakly performing zones. It also serves as an operational tool for planners and policymakers to prioritize redevelopment, investment, or policy reform based on empirical spatial metrics.

3.4.7. SWOT Analysis (KAFD, Riyadh)

Strengths

KAFD demonstrates several notable strengths as a transit-oriented development. It features a high-density, mixed-use urban form deliberately anchored around transit nodes. The masterplan integrates residential, commercial, leisure, and institutional functions in a compact vertical layout, fostering a vibrant live-work-play environment within ~1.6 million m2 of space. Over 60 high-rise towers populate the district, reflecting a paradigm shift toward walkable density in Riyadh’s car-centric context.

Additionally, KAFD boasts strategic multimodal connectivity. It sits at the convergence of three Riyadh Metro lines (Blue, Yellow, and Violet) with a landmark interchange station designed by Zaha Hadid Architects, which links seamlessly to the district’s internal monorail and feeder bus services [

78]. This hub enables smooth intermodal transfers and a broad transit catchment, reducing car dependency through convenient access. Another strength is KAFD’s commitment to sustainable design. The project incorporates advanced green building practices and infrastructure; as of 2025, it is recognized as the world’s largest LEED Platinum-certified mixed-use business district. Dozens of its buildings have achieved LEED Silver, Gold, or Platinum status, exemplifying energy-efficient design and smart technology integration on a district-wide scale. These strengths—density around transit, excellent connectivity, and sustainable construction—establish KAFD as a pioneering model for TOD principles in the Gulf region.

Weaknesses

Notwithstanding its macro-scale advantages, KAFD faces environmental and design weaknesses that challenge day-to-day usability. Foremost, Riya’s extreme climate undermines outdoor comfort and pedestrian activity. Summer temperatures routinely exceed 45 °C, and the intense sun and low humidity make walking outdoors arduous for much of the year. In KAFD’s at-grade public spaces, limited shade and heat-reflective paving lead to low daytime foot traffic despite the TOD layout. The development has mitigated this partly with air-conditioned sky bridges and an internal people-mover. However, large portions of the pedestrian realm remain exposed to harsh conditions. Thus, the walkability and ground-level street life are constrained without additional climate-adaptive measures (e.g., continuous shading, cooling mist, and greenery). Another weakness is the underdeveloped cycling infrastructure. KAFD provides minimal dedicated bicycle lanes or facilities within its footprint, meaning active mobility options are scant. This gap limits first/last-mile connectivity and makes the district highly auto-oriented outside the immediate metro access. By relying heavily on transit and cars while neglecting cycling, KAFD misses an opportunity to diversify mobility; the lack of bike paths and related amenities contrasts with the project’s otherwise modern transport vision. These weaknesses highlight that micro-scale design and comfort need improvement—the district must better adapt to the local climate and promote active travel to fully realize a human-friendly, all-day, every-day, urban environment.

Opportunities

There are significant opportunities for KAFD to enhance its performance and influence broader urban development. One key opportunity is to expand active rail infrastructure and green connectivity in and around the district. Riyadh is investing in city-scale recreational mobility projects, most notably the Sports Boulevard—a 135 km linear park stretching east–west across the capital with 220 km of cycling paths and over 130 km of walking trails. This network passes near KAFD, including new features like a dedicated cycling bridge and a 4 km landscaped promenade in the vicinity. By linking KAFD’s internal walkways and transit stations with these emerging bike/pedestrian corridors, the district can greatly improve first-and-last-mile access for commuters and visitors. Enhancing shaded sidewalks, bike lanes, and safe crossings to interface with Sports Boulevard would encourage active mobility and extend KAFD’s reach into surrounding neighborhoods. Another opportunity is to leverage KAFD as a replicable TOD model for future projects in Riyadh and across Saudi Arabia. The planning lessons learned—such as mixing land uses, aligning high-density development with transit, and creating semi-climate-controlled public realms—can inform new urban nodes as the Riyadh Metro and other Vision 2030 initiatives expand. KAFD is one of the region’s main districts that commands high-density, transit-oriented development possibilities. Its long-term viability could set an international standard for polycentric city growth, centered on more metro interchanges or “giga-project” districts and cementing TOD as a national benchmark of best practices. By capitalizing on these opportunities—strengthening active transit links and serving as a prototype for sustainable urban centers, KAFD can improve livability and usage and influence a wider shift toward transit-oriented planning in the Kingdom.

Threats

Finally, KAFD must navigate certain threats that may impede its objectives. One concern is the encroachment of automobile traffic from the surrounding roadway network. The district is encircled by major arterial highways (e.g., the Northern Ring Road along its edge). If a significant portion of people continue to drive to or around KAFD—due to habit or insufficient area-wide transit coverage—the influx of vehicles could create congestion and erode the walkable environment. Indeed, despite KAFD’s internal transit-friendly design, the broader city’s car dependence and incomplete transit links have historically led to high vehicular loads and traffic bottlenecks in this area. Traffic spill-over from adjacent expressways or excessive parking demand would threaten the pedestrian-priority ethos of the district. Another major threat lies in real-estate market risk, particularly the potential oversupply of commercial space and the long-term economic viability of the project. KAFD was conceived as a colossal financial hub, and observers early on warned that its office and retail capacity might far exceed near-term market needs. The initial development phase coincided with a global financial downturn, resulting in delayed openings and difficulty attracting tenants. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 plan openly acknowledged that the project lacked economic feasibility initially, leading to “a significant increase in construction costs… and a large oversupply of commercial space for the years to come”, making it challenging to achieve healthy occupancy rates (82). Despite a new strategy to relocate KAFD to the Public Investment Fund and inject fresh residential activity, the KAFD’s success relies on absorption within the market. The absence of absorption will leave some KAFD phases unoccupied or subject to artificially lower leasing rates, possibly turning the project into an inadequate, vibrant, thriving urban center. Stabilizing this dimension requires an aggressive stance towards diversifying the composition and makeup of the user, appropriate expansion planning, and parallel KAFD products accordingly with realistic demand. All else being equal, traffic elements and demand as a market shall always take primacy over KAFD, not underestimating TOD ideals and long-term results.

4. Results: Comparative Overview

4.1. Case Study 1: High-Rise, Low-Function: The Misalignment of Form and Function in West Bay-Doha

The iconic skyline of West Bay, viewed from the Museum of Islamic Art, has dramatically evolved since the 1970s and stands as a striking symbol of Doha’s rapid modernization. However, this very skyline reveals a contradiction at the heart of the district: the vertical growth of skyscrapers reflects a lack of coherent formal structure, resulting in an architectural collage of grotesque simulacra emblematic of global neo-liberal urbanism.

West Bay suffers from foundational structural deficiencies, primarily stemming from an early lack of clarity about the district’s purpose. Initially envisioned as a residential zone with luxurious villas, it was subsequently dissected by large regional road infrastructures, fragmenting the area into three disconnected sectors. Later, the district was reimagined as a Central Business District (CBD), but superficial changes marked this transition. Today, West Bay occupies a hybrid identity—neither a fully integrated city center nor a cohesive residential district. The area has evolved into a “vertical village,” where individual towers rise in isolation, lacking any meaningful formal or functional relationship with each other. A rudimentary zoning scheme governs these towers, specifying only a minimum height (G + 15), a base footprint coverage of 50%, an upper floor coverage of 30%, and a minimum setback of 12.5 m from the plot boundaries.

Despite their flamboyant architectural forms, the towers create a monotonous urban landscape, typically based on a 45 × 40 m footprint and surrounded by surface parking, devoid of street-level commercial engagement. Their arbitrary placement within plots prevents alignment with adjacent roads, which are designed solely for high-speed vehicular traffic, thereby undermining pedestrian connectivity.

The public realm—comprising streets, sidewalks, alleys, parks, and squares—suffers the most. Streets in each sector often have disjointed, inconsistent layouts that terminate in T-junctions, lacking basic pedestrian infrastructure such as sidewalks, shade, or seating areas. Walking between buildings is often an “adventure” through sun-exposed alleyways. Apart from the recently developed Sheraton Park, connected to the Corniche’s green belt, most green spaces are residual, misused as informal parking lots.

Public gathering is limited to enclosed commercial environments such as City Center and The Gate Mall, or confined to hotel lobbies. However, the popularity of privately initiated outdoor spaces, like the Lavazza café terrace near The Gate Mall, reveals a public appetite for high-quality open spaces. This success, driven by Tactical Urbanism, underscores the urgent need to multiply such interventions and integrate them into a continuous pedestrian network with associated public amenities.

While the role of West Bay’s Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) as a transportation node within the regional system is uncontested, its ability to act as a place-maker remains questionable. The newly established West Bay North Station, opposite the Doha Exhibition and Convention Center on Omar Al Mukhtar Street, has spurred the creation of a service cluster around City Center Mall and The Gate Mall. These elements are linked by minimal-grade and elevated pedestrian walkways. However, this approach—consolidating services within mega-containers—fails to enrich the public realm or activate the vast, underutilized spaces between towers.

In contrast, the West Bay station along Majlis Al Taawon Street remains underdeveloped, characterized by a lack of services and vacant plots. This site represents a potential laboratory for strategic redevelopment, not through grand schemes but through modest retrofits: shaded sidewalks, usable open spaces, road reconfiguration, and the removal of fences. Both governmental bodies (the Ministry of Planning and the Municipality) and academia recognize the importance of aligning TOD with higher density and programmatic intensity.

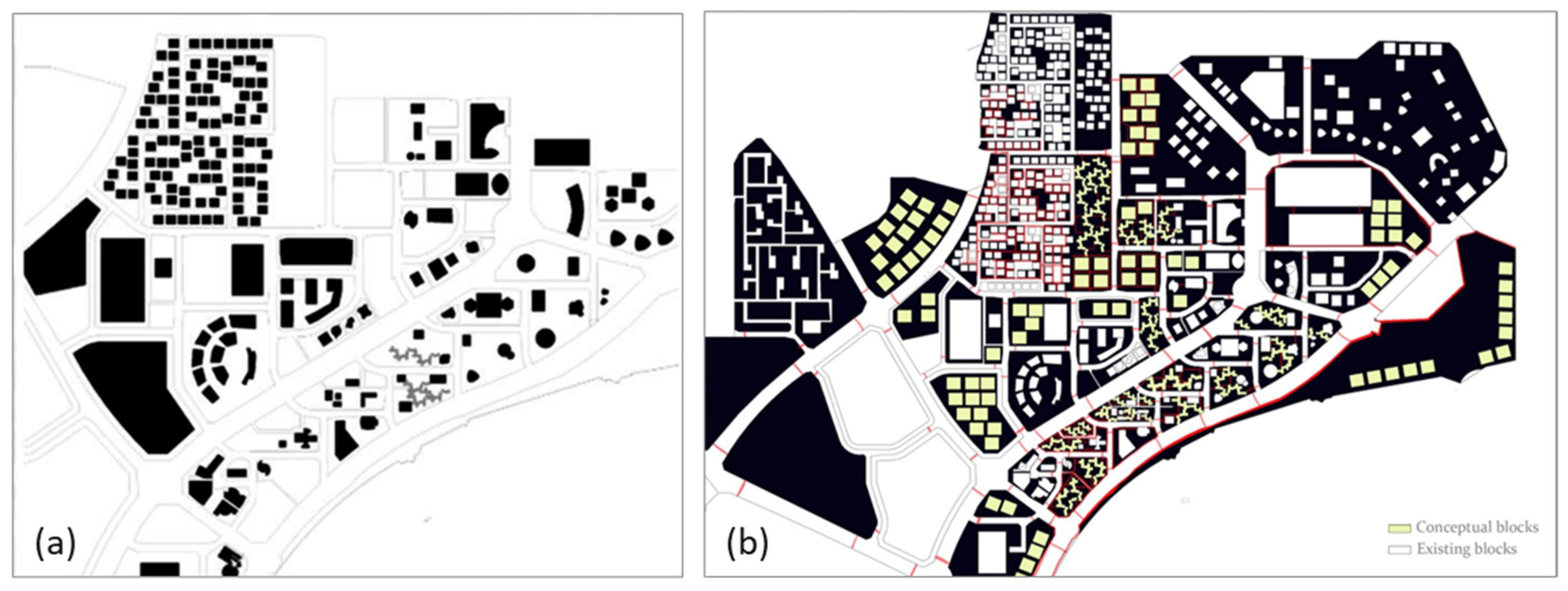

Nevertheless, current approaches risk over-relying on increasing tower height and intensifying commercial hubs, expecting private developers to activate voids between towers spontaneously. In-filling these spaces with mid-rise buildings (3–4 stories), as proposed in

Figure 28, may offer a more organic transformation—mirroring the older residential fabric to the northwest. This densification could stimulate demand for local services and foster neighborhood vitality.

A comparable model, widely implemented in China, features a continuous podium structure (3–4 stories high) at the base of towers, stretching across entire blocks and integrating public services, retail, and parking. One local adaptation is the Ezdan Towers complex, composed of four 35-story towers rising above a four-story base of underground parking, a roof garden, community amenities, and street-level retail. This mixed-use podium has not only enhanced residential options but has also attracted users from across West Bay. However, this solution introduces challenges:

Impenetrability: The podiums often present blank façades at street level, limiting permeability and walkability.

Privatization of space: Retail functions are inward-facing, effectively enclosing public space.

Poor environmental performance: Continuous podium walls hinder airflow, exacerbate heat retention, and reduce air quality.

Retrofit limitations: Unlike Ezdan Towers, most existing towers in West Bay were not designed with podiums, complicating retrofitting efforts.

Conceptually, the redevelopment of West Bay’s station area bears parallels to the post-Soviet rehabilitation of Khrushchyovka neighborhoods in the 1990s. Just as those Soviet-era districts required careful reintegration of social, spatial, and functional layers, West Bay must now reconcile its fragmented urban fabric through a balanced, human-centric approach to urban transformation.

4.2. Case Study 2: Form and Function in King Abdullah Financial District in Riyadh

The King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD) emerges as a flagship development within Riyadh’s Vision 2030 agenda, conceived as a purpose-built, high-density financial district where form and function are intended to align from the outset. In contrast to the piecemeal evolution of West Bay, KAFD was strategically planned to embody the principles of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD), integrating vertical layering, mixed land use, and multimodal access across its 1.6 million square meter footprint (

Figure 29). The district hosts a diverse programmatic mix, combining office towers, residential blocks, retail zones, institutional facilities, and planned leisure venues, all within walking distance of multiple transit options. The center of its transit system is a principal interchange station of metros, the Zaha Hadid Architects project, interconnecting Riyadh Metro’s Blue, Yellow, and Purple Lines. With the station, an internal monorail, and an extensive skywalk system, KAFD’s emphasis on multimodal interoperability and climate-responsive mobility infrastructure comes to the fore.

At the macro level, KAFD’s infrastructure and zoning logic adhere closely to TOD ideals: compact building forms, a hierarchical transport system, and planned density gradation all contribute to its spatial coherence [

Table 1]. However, at the micro-scale, significant challenges emerge. While the district features shaded plazas, granite-paved walkways, and landscaped boulevards, the pedestrian experience remains uneven. Riyadh’s extreme heat and arid climate—combined with insufficient shading and sparse vegetation in many public areas—limit the usability and comfort of outdoor spaces. Despite climate mitigation efforts, thermal exposure discourages prolonged engagement with the public realm, often redirecting pedestrians and flows into enclosed, air-conditioned interiors or elevated walkways. Its two-circulation system—a formal and exposed one and an interior and functional one—can produce a vertical division of city life, a visually beautiful ground plan, but socially inactive.

In addition, KAFD’s bike infrastructure remains underutilized, a missed opportunity for bike mobility and integration with the future connection to the adjacent Sports Boulevard project—a 135 km recreational spine connecting Riyadh. Regarding symbolic value, KAFD is a visual and infrastructural representation of Saudi Arabia’s global competitiveness and ambitions for sustainable urban transformation. However, like West Bay, it faces a critical tension between symbolic architecture and lived experience. Usability gaps in the public realm, limited spontaneity in urban encounters, and concerns over long-term real estate viability underscore the challenges of translating planning vision into day-to-day urban vitality. In this context, while KAFD performs strongly across most TOD metrics—such as land use diversity, transit proximity, and compactness [

Table 1]—its success as a place-maker will ultimately depend on addressing microclimatic comfort, enhancing pedestrian and cycling infrastructure, and fostering inclusive, street-level activation. Its bold design and planning innovations translate into a resilient, lively urban district that can thrive beyond mere symbolism.

4.3. Comparisons Doha vs. Riyadh

To systematically compare the spatial performance and implementation of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) in West Bay (Doha) and the King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD, Riyadh), a set of key urban planning parameters was selected to structure the comparative analysis, as detailed in

Table 1. These parameters were not chosen arbitrarily but rather derived from the broader theoretical framework outlined in the literature review and aligned with the empirical focus of the research. Specifically, the parameters reflect the seven foundational TOD principles—land use diversity, density, connectivity, walkability, public realm quality, transit accessibility, and environmental responsiveness—which have been consistently emphasized throughout this research’s analytical and methodological sections. By including metrics such as urban typology, transit integration, metro access range (400–800 m), and climate adaptation strategies, the table allows for a holistic evaluation of both macro and micro-scale TOD components.

The inclusion of parameters like green space proximity, building compactness, and symbolic function responds directly to the spatial mapping and qualitative assessments previously conducted in both case studies. For example, density and walkability are particularly critical in assessing the usability of public space in extreme climates. At the same time, transit integration and metro access buffers allow for quantifiable spatial diagnostics related to first- and last-mile connectivity. Similarly, adding climate adaptation and symbolic function categories helps contextualize each district’s alignment with national planning narratives—namely, Qatar’s Vision 2030 and the QNDF 2032 in the case of West Bay and Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 in the case of KAFD. These broader ambitions frame the physical planning and investment logic of both sites.

By structuring the comparison along these parameters,