Indicator Assessment of Sustainable Development Goals: A Global Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Analysis

2.1. Development Goals Towards Sustainability

- At the journal level, Sustainability prevails with 14,970 documents (4.2% of the total), followed by the Journal of Cleaner Production with 4067 and Energies with 3105 documents in the period 2021–2025. In the total period, Sustainability again stood out with 19,739 documents (3.7% of the total), the Journal of Cleaner Production with 6638, and Energies with 3805 documents;

- At the country level, China prevails with 66,091 documents (18.6% of the total), followed by the United States with 44,154 and India with 36,238 documents in the period 2021–2025. Comparing the data with the total, the United States emerges with 85,745 documents (16.3% of the total), followed by China with 79,626 and the United Kingdom with 51,555 documents.

2.2. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

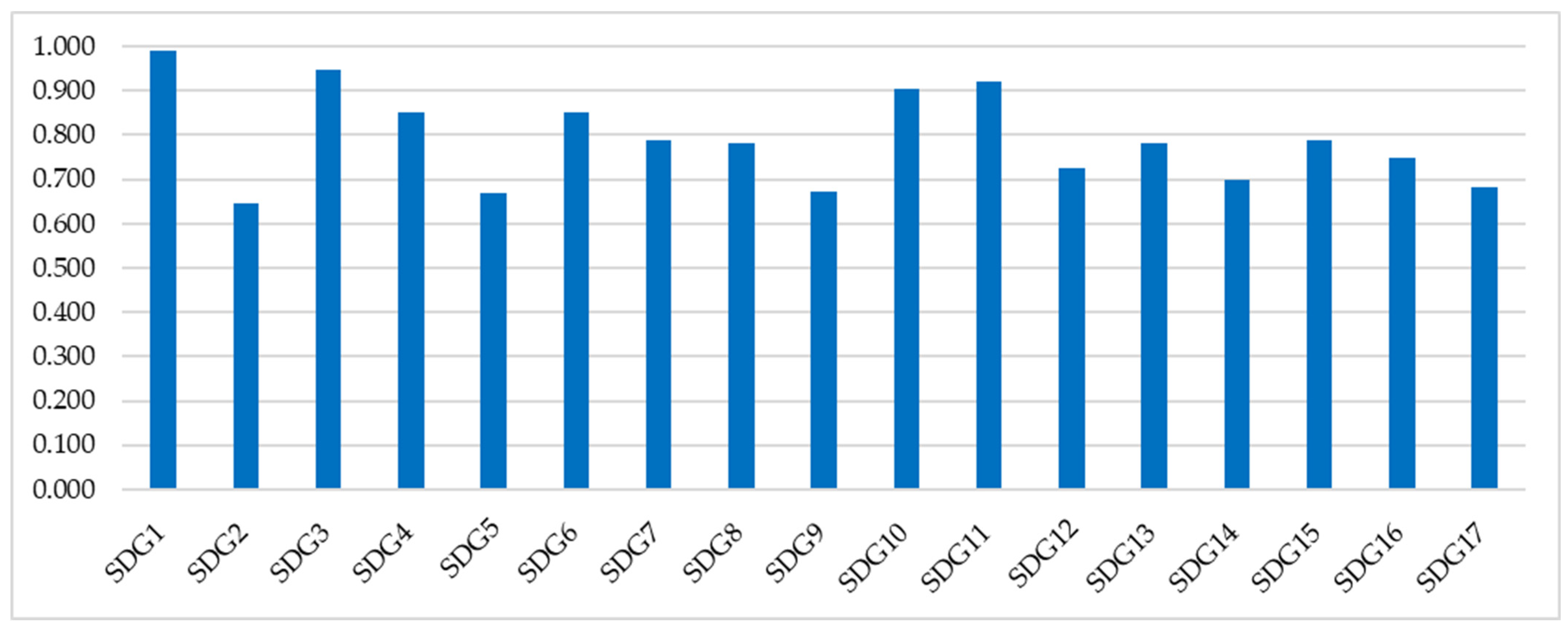

4.1. SDG Value Through Normalization Min-Max

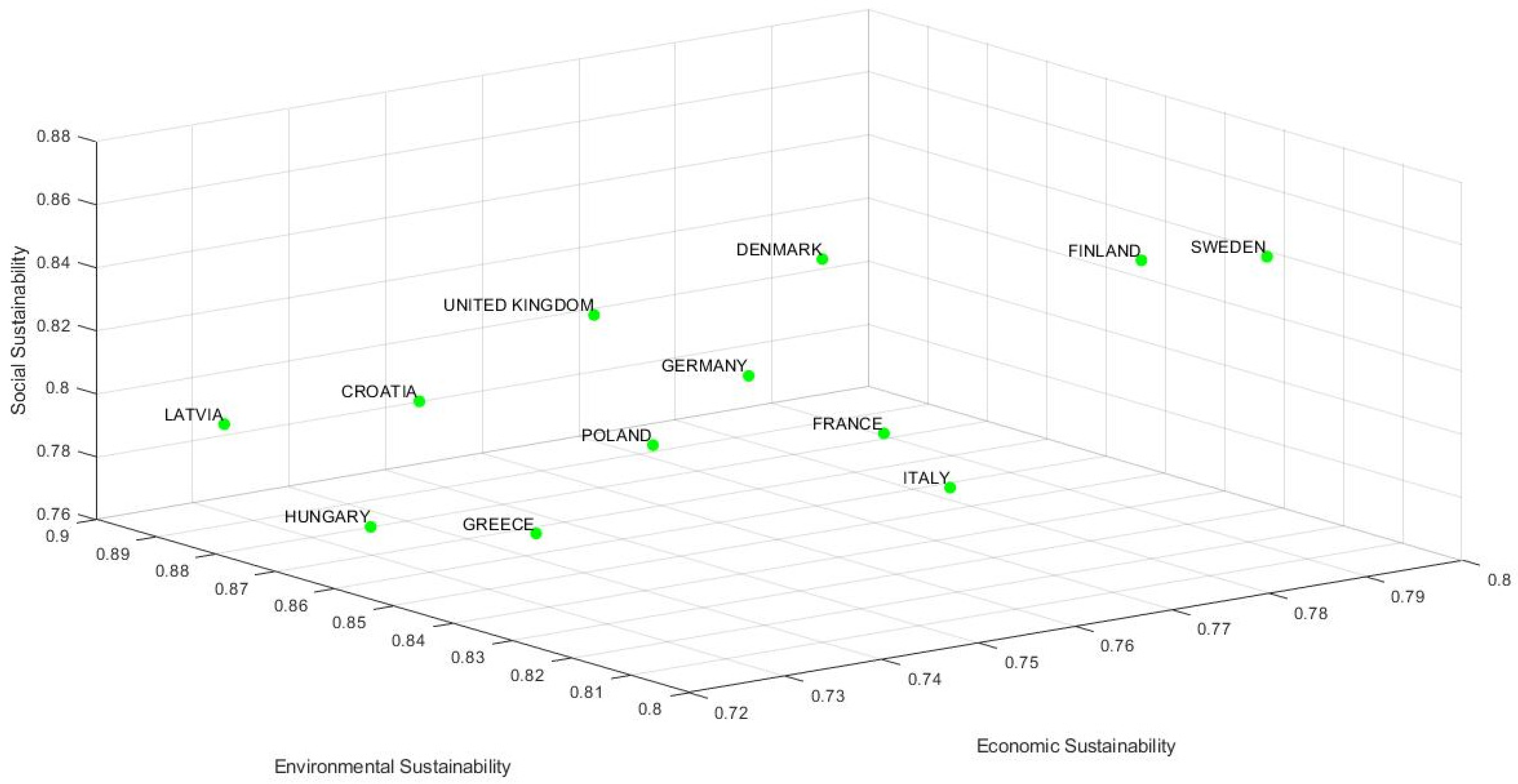

4.2. SDG Analysis by SDG Dimensions

4.3. A Comparison Between the OECD and BRICS+

4.4. A Comparison Among Continents

4.5. A Comparison Between Italy and the EU27

4.6. TOPSIS

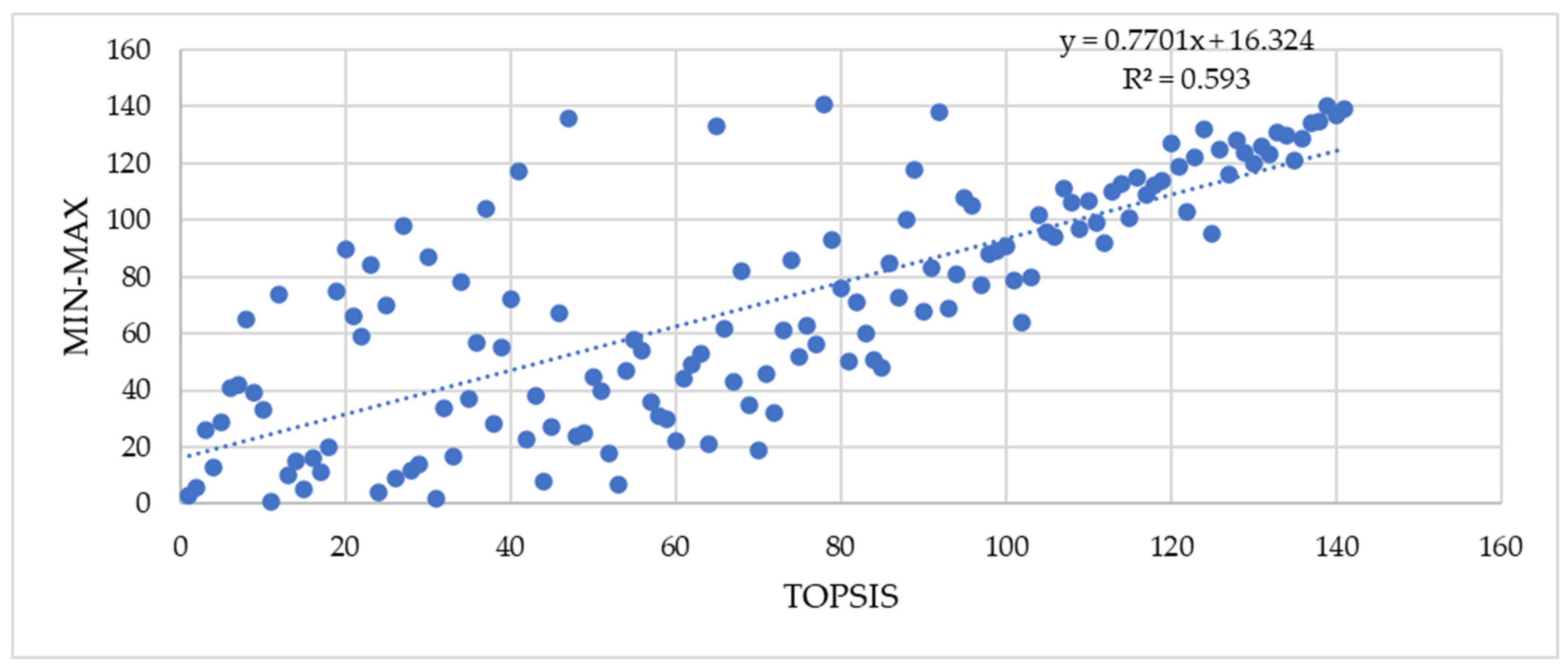

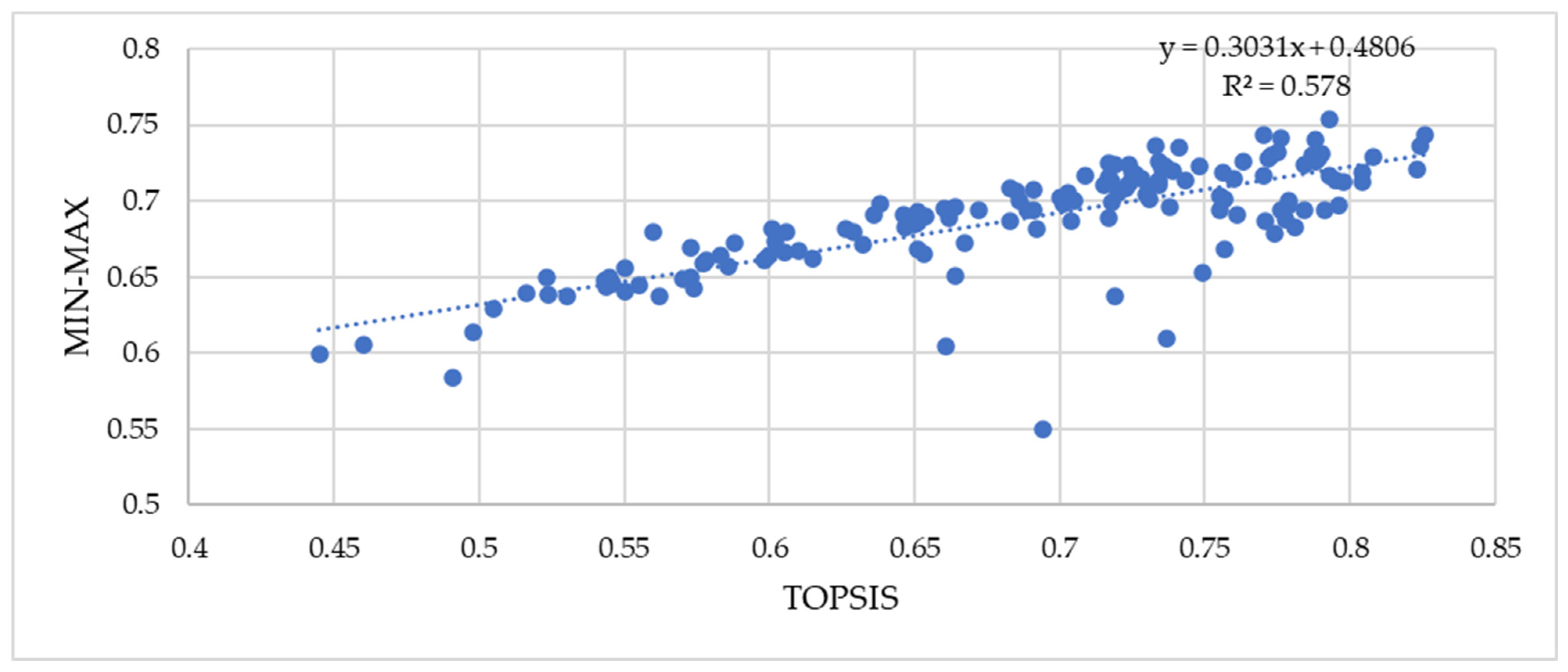

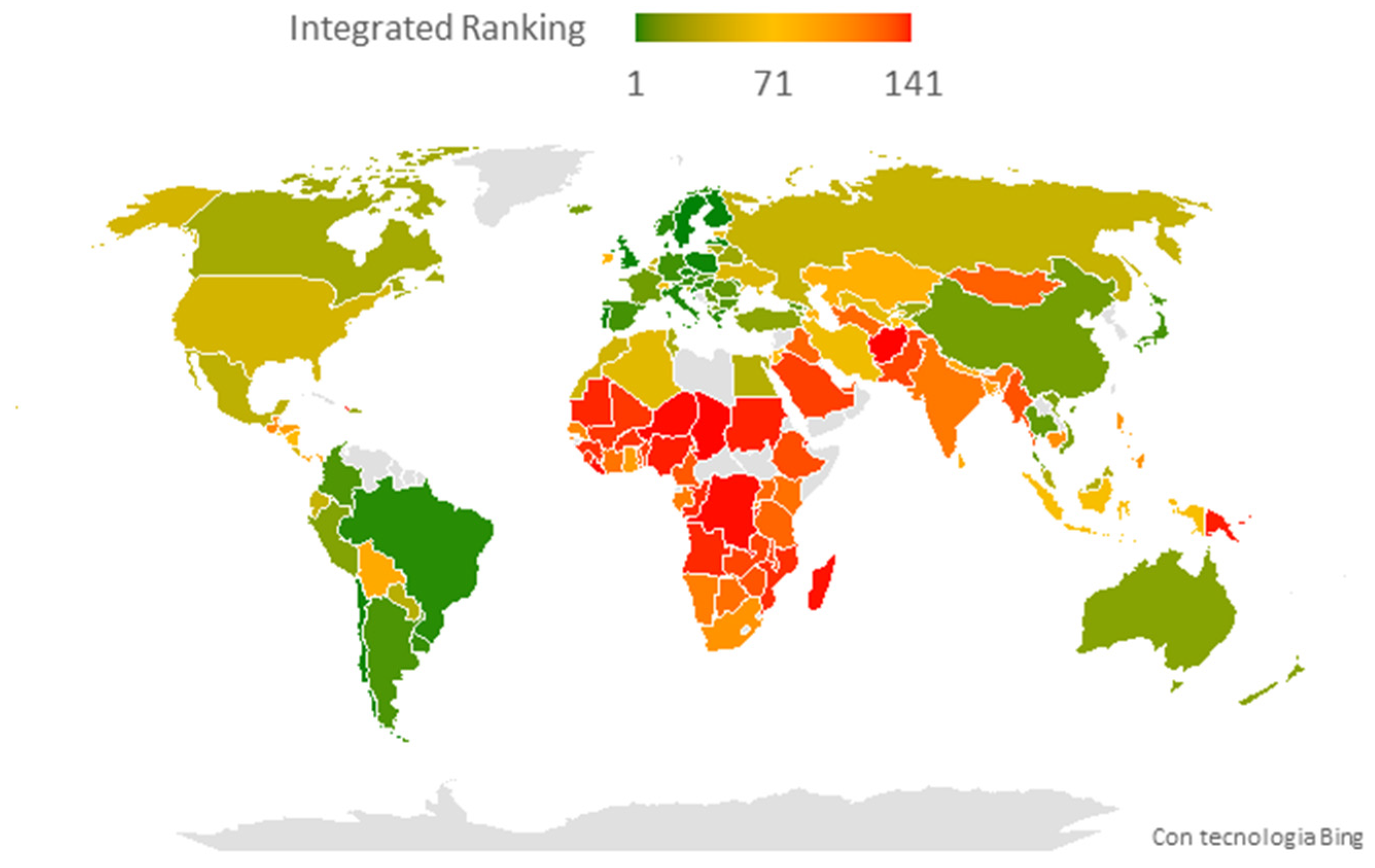

4.7. The Integrated Min-Max and TOPSIS Method

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leal Filho, W.; Dibbern, T.; Pimenta Dinis, M.A.; Coggo Cristofoletti, E.; Mbah, M.F.; Mishra, A.; Clarke, A.; Samuel, N.; Castillo Apraiz, J.; Rimi Abubakar, I.; et al. The added value of partnerships in implementing the UN sustainable development goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 438, 140794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Di Carlo, C.; Gastaldi, M.; Rossi, E.N.; Uricchio, A.F. Economic Performance, Environmental Protection and Social Progress: A Cluster Analysis Comparison towards Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazar, R.; Meo, M.S.; Ali, S. Role of public health and trade for achieving sustainable development goals. J. Public Aff. 2022, 22, e2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.-L.; Yeh, S.-C. The trends of major issues connecting climate change and the sustainable development goals. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordonez-Ponce, E. Exploring the Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals on Sustainability Trends. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, L.P.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Zlati, M.L.; Fortea, C.; Antohi, V.-M.; Barbuta-Misu, N. Cluster Analysis of the Transition to Climate Neutrality in the European Union. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudełko, J. Development sustainability levels in EU countries. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 2797–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lella, L.; Oses-Eraso, N.; Stamos, I. Pioneering a sustainable development goals monitoring framework for European regions. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhle, P.; Stamos, I.; Proietti, P.; Siragusa, A. Environmental monitoring in European regions using the sustainable development goals (SDG) framework. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 21, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegan, J.C.; Filion, A.M.; Keisler, J.M.; Linkov, I. Trends and applications of multi-criteria decision analysis in environmental sciences: Literature review. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2017, 37, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.; Coles, S.R.; Kirwan, K. Analysis of the potentials of multi criteria decision analysis methods to conduct sustainability assessment. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 46, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanifar, M.; Tavana, M.; Santos-Arteaga, F.J.; Sharafi, H. A hybrid multi-attribute decision-making and data envelopment analysis model with heterogeneous attributes: The case of sustainable development goals. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 147, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.; Almeida, M.F.; Calili, R. Multiple Criteria Decision Making for the Achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals: A Systematic Literature Review and a Research Agenda. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Silva, D.F.; de Almeida Filho, A.T. Sorting with TOPSIS through boundary and characteristic profiles. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 141, 106328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M.; Cenk, Z.; Erdebilli, B.; Selim Özdemir, Y.; Gholian-Jouybari, F. Pythagorean Fuzzy TOPSIS Method for Green Supplier Selection in the Food Industry. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 224, 120036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancas, F.J.; Contreras, I. Global SDG composite indicator: A new methodological proposal that combines compensatory and non-compensatory aggregations. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Gastaldi, M.; Uricchio, A.F. A multiple criteria analysis approach for assessing regional and territorial progress toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in Italy. Decis. Anal. J. 2025, 15, 100559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miola, A.; Schiltz, F. Measuring sustainable development goals performance: How to monitor policy action in the 2030 Agenda implementation? Ecol. Econ. 2019, 164, 106373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcamo, J.; Thompson, J.; Alexander, A.; Antoniades, A.; Delabre, I.; Dolley, J.; Marshall, F.; Menton, M.; Middleton, J.; Scharlemann, J.P.W. Analysing interactions among the sustainable development goals: Findings and emerging issues from local and global studies. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1561–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Barrera, M.E.; Alfaro-Aucca, C.; Pacheco-Mendoza, J.; Moreno-Albarrán, M.; Pacheco-Luza, E.F.; Rengifo Chunga, C.E. Bibliometric analysis of prominent topics in global scientific production on sustainable development goals in Scopus (2013–2022). Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuc-Czarnecka, M.; Markowicz, I.; Sompolska-Rzechuła, A. SDGs implementation, their synergies, and trade-offs in EU countries—Sensitivity analysis-based approach. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavesley, A.; Trundle, A.; Oke, C. Cities and the SDGs: Realities and possibilities of local engagement in global frameworks. Ambio 2022, 51, 1416–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandari, R.; Moallemi, E.A.; Kharrazi, A.; Trogrlić, R.Š.; Bryan, B.A. Transdisciplinary approaches to local sustainability: Aligning local governance and navigating spillovers with global action towards the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 1293–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostetckaia, M.; Hametner, M. How Sustainable Development Goals interlinkages influence European Union countries’ progress towards the 2030 Agenda. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 916–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Bao, S.; Ren, J.; Xu, Z.; Xue, S.; Liu, J. Global transboundary synergies and trade-offs among Sustainable Development Goals from an integrated sustainability perspective. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebara, C.H.; Thammaraksa, C.; Hauschild, M.; Laurent, A. Selecting indicators for measuring progress towards sustainable development goals at the global, national and corporate levels. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 44, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I. Sustainable communities: We are the world. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, E.; Filipowicz-Chomko, M. Measuring sustainable development in the education area using multi-criteria methods: A case study. Cent. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 28, 1219–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, F.; Grigoroudis, E.; Zopounidis, C.; Tsagarakis, K.P. An integrated evaluation framework for Environmental, Social, and Governance-driven social media performance through Multi-criteria Decision-Analysis. Decis. Anal. J. 2024, 12, 100505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Ke, G.Y.; Hipel, K.W. An ordinal classification of brownfield remediation projects in China for the allocation of government funding. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, I.B.; Keisler, J.; Linkov, I. Multi-criteria decision analysis in environmental sciences: Ten years of applications and trends. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 3578–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munda, G. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis and Sustainable Development. In Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: State of the Art Surveys; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 953–986. ISBN 978-0-387-23081-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six Transformations to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zanten, J.A.; van Tulder, R. Towards nexus-based governance: Defining interactions between economic activities and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2021, 28, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Gastaldi, M. Sustainable Development Goals: A Regional Overview Based on Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hametner, M.; Kostetckaia, M. Frontrunners and laggards: How fast are the EU member states progressing towards the sustainable development goals? Ecol. Econ. 2020, 177, 106775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akande, A.; Cabral, P.; Gomes, P.; Casteleyn, S. The Lisbon ranking for smart sustainable cities in Europe. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 44, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Gastaldi, M. Monitoring Performance of Sustainable Development Goals in the Italian Regions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Drumm, E. Implementing the SDG Stimulus: Sustainable Development Report 2023; SDSN: Paris, France; Dublin University Press: Dublin, Ireland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, C.; Metternicht, G.; Wiedmann, T. Prioritising SDG targets: Assessing baselines, gaps and interlinkages. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño-Pineda, A.; Cano, J.A.; Gómez-Montoya, R. Application of AHP for the Weighting of Sustainable Development Indicators at the Subnational Level. Economies 2021, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B.; Burgess, J.C. Sustainable development goal indicators: Analyzing trade-offs and complementarities. World Dev. 2019, 122, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandakoglu, A.; Frini, A.; Ben Amor, S. Multicriteria decision making for sustainable development: A systematic review. J. Multi-Criteria Decis. Anal. 2019, 26, 202–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciolini, E.; Rocchi, L.; Cardinali, M.; Paolotti, L.; Ruiz, F.; Cabello, J.M.; Boggia, A. Assessing Progress Towards SDGs Implementation Using Multiple Reference Point Based Multicriteria Methods: The Case Study of the European Countries. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 162, 1233–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, A.; Suresh, M.; Nedungadi, P.; Raman, R.R. Mapping analytical hierarchy process research to sustainable development goals: Bibliometric and social network analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Górecka, D.; Roszkowska, E. Enhancing Spatial Analysis through Reference Multi-Criteria Methods: A Study Evaluating EU Countries in terms of Sustainable Cities and Communities. Netw. Spat. Econ. 2025, 25, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaimo, L.S.; Ciacci, A.; Ivaldi, E. Measuring Sustainable Development by Non-aggregative Approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 157, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toro, P.; Formato, E.; Fierro, N. Sustainability Assessments of Peri-Urban Areas: An Evaluation Model for the Territorialization of the Sustainable Development Goals. Land 2023, 12, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abanda, F.H.; Chia, E.L.; Enongene, K.E.; Manjia, M.B.; Fobissie, K.; Pettang, U.J.M.N.; Pettang, C. A systematic review of the application of multi-criteria decision-making in evaluating Nationally Determined Contribution projects. Decis. Anal. J. 2022, 5, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.S.; Steffen, V.; de Francisco, A.C.; Trojan, F. Integrated data envelopment analysis, multi-criteria decision making, and cluster analysis methods: Trends and perspectives. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 8, 100271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchinetti, S.; Siletti, E. Well-being Indicators: A Review and Comparison in the Context of Italy. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 159, 523–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, P.P.; Sharma, D.K. Performance measures of sustainable development goals using SWI MCDM methods: A case of the Indian states. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Alkhawaji, R.N.; Shafieezadeh, M.M. Evaluating sustainable water management strategies using TOPSIS and fuzzy TOPSIS methods. Appl. Water Sci. 2024, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, E.; Filipowicz-Chomko, M. A Multi-Criteria Method Integrating Distances to Ideal and Anti-Ideal Points. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G. The SDGs and the UN Summit of the Future: Sustainable Development Report 2024; SDSN: Paris, France; Dublin University Press: Dublin, Ireland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| SDG | Indicators |

|---|---|

| SDG1 No poverty | Incidence rate of poverty at USD 2.15/day (2017 PPP, %) |

| Poverty incidence rate at USD 3.65/day (2017 PPP, %) | |

| SDG2 Zero hunger | Prevalence of undernourishment (%) |

| Prevalence of stunting in children under 5 years of age (%) | |

| Prevalence of wasting in children under 5 years of age (%) | |

| Prevalence of obesity, BMI ≥ 30 (% of adult population) | |

| Human trophic level (2–3) | |

| Cereal yield (tons per hectare of harvested land) | |

| Sustainable nitrogen management index (0–1.41) | |

| SDG3 Good health and well-being | Maternal mortality ratio (per 100,000 live births) |

| Neonatal mortality rate (per 1000 live births) | |

| Under-five mortality rate (per 1000 live births) | |

| Tuberculosis incidence (per 100,000 inhabitants) | |

| Age-standardized mortality rate due to cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, or chronic respiratory disease in adults aged 30–70 years (%) | |

| Age-standardized mortality rate attributable to domestic and environmental air pollution (per 100,000 inhabitants) | |

| Deaths from road accidents (per 100,000 inhabitants) | |

| Life expectancy at birth (years) | |

| Adolescent fertility rate (births per 1000 women aged 15 to 19) | |

| Births attended by skilled health personnel (%) | |

| Infants surviving and receiving two WHO-recommended vaccines (%) | |

| Universal health coverage (UHC) service coverage index (0–100) | |

| Subjective well-being (average score on a scale of 0–10) | |

| SDG4 Quality education | Net primary school enrollment rate (%) |

| Lower secondary school completion rate (%) | |

| SDG5 Gender equality | Family planning demand satisfied with modern methods (% of women aged 15 to 49) |

| Ratio of average years of schooling received by women and men (%) | |

| Ratio of women to men in the labor force (%) | |

| Seats held by women in national parliament (%) | |

| SDG6 Clean water and sanitation | Population using at least basic drinking water services (%) |

| Population using at least basic sanitation (%) | |

| Freshwater withdrawal (% of available freshwater resources) | |

| Anthropogenic wastewater receiving treatment (%) | |

| Water consumption embedded in imports (m3 H2O eq/capita) | |

| SDG7 Affordable and clean energy | Population with access to electricity (%) |

| Population with access to clean cooking fuels and technologies (%) | |

| CO2 emissions from fuel combustion for total electricity production (MtCO2/TWh) | |

| Share of renewable energy in total final energy consumption (%) | |

| SDG8 Decent work and economic growth | Adjusted GDP growth (%) |

| Victims of modern slavery (per 1000 inhabitants) | |

| Adults with a bank account or other financial institution account or with a mobile money service provider (% of population aged 15 and over) | |

| Fatal accidents at work incorporated into imports (per million inhabitants) | |

| Victims of modern slavery incorporated into imports (per 100,000 inhabitants) | |

| SDG9 Industry, innovation, and infrastructure | Rural population with access to roads usable in all seasons (%) |

| Population using the Internet (%) | |

| Mobile broadband subscriptions (per 100 inhabitants) | |

| Logistics performance index: infrastructure score (1–5) | |

| Times Higher Education University Rankings: average score of top 3 universities (0–100) | |

| Articles published in academic journals (per 1000 inhabitants) | |

| SDG10 Reduced inequalities | Palma Index |

| SDG11 Sustainable cities and communities | Average annual concentration of PM2.5 (μg/m3) |

| Access to improved water sources connected to the network (% of urban population) | |

| SDG12 Responsible consumption and production | Municipal solid waste (kg/capita/day) |

| Electronic waste (kg per capita) | |

| Air pollution based on production (DALY per 1000 inhabitants) | |

| Air pollution associated with imports (DALY per 1000 inhabitants) | |

| Nitrogen emissions based on production (kg/capita) | |

| Nitrogen emissions associated with imports (kg/capita) | |

| SDG13 Climate action | CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion and cement production (tCO2/per capita) |

| Greenhouse gas emissions embodied in imports (tCO2/capita) | |

| SDG14 Life below water | Threats to marine biodiversity embedded in imports (per million inhabitants) |

| SDG15 Life on land | Average protected area in terrestrial sites important for biodiversity (%) |

| Average protected area in freshwater sites important for biodiversity (%) | |

| Red List Index of species survival (0–1) | |

| Imported deforestation (m2/capita) | |

| SDG16 Peace, justice, and strong institutions | Birth registrations with civil authorities (% of children under 5) |

| Corruption perception index (0–1) | |

| Exports of major conventional weapons (millions of USD TIV constant per 100,000 inhabitants) | |

| Press freedom index (0–100) | |

| SDG17 Partnerships for the goals | Public spending on health and education (% of GDP) |

| Corporate tax haven score (0–100) | |

| Statistical performance index (0–100) | |

| Index of countries’ support for UN-based multilateralism (0–100) |

| Rkg | Countries | Avg | Rkg | Countries | Avg | Rkg | Countries | Avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sweden | 0.826 | 48 | Romania | 0.736 | 95 | Turkmenistan | 0.653 |

| 2 | Finland | 0.824 | 49 | China | 0.735 | 96 | Botswana | 0.651 |

| 3 | Denmark | 0.823 | 50 | Tunisia | 0.734 | 97 | Cambodia | 0.651 |

| 4 | United Kingdom | 0.808 | 51 | Dominican Republic | 0.734 | 98 | Rwanda | 0.651 |

| 5 | Norway | 0.804 | 52 | Georgia | 0.734 | 99 | Gabon | 0.650 |

| 6 | Germany | 0.804 | 53 | Albania | 0.733 | 100 | India | 0.647 |

| 7 | Japan | 0.798 | 54 | Malaysia | 0.731 | 101 | Senegal | 0.646 |

| 8 | France | 0.796 | 55 | Ukraine | 0.731 | 102 | Bangladesh | 0.638 |

| 9 | Spain | 0.795 | 56 | Russia | 0.730 | 103 | Lao People’s Democratic Republic | 0.636 |

| 10 | Austria | 0.793 | 57 | Republic of Kyrgyzstan | 0.728 | 104 | Iraq | 0.632 |

| 11 | Croatia | 0.793 | 58 | Armenia | 0.726 | 105 | Kenya | 0.629 |

| 12 | Australia | 0.791 | 59 | Turkey | 0.725 | 106 | Ivory Coast | 0.626 |

| 13 | Portugal | 0.790 | 60 | Vietnam | 0.724 | 107 | Burma | 0.615 |

| 14 | Czech Republic | 0.789 | 61 | Mexico | 0.724 | 108 | Gambia | 0.610 |

| 15 | Poland | 0.788 | 62 | Morocco | 0.723 | 109 | Tanzania | 0.606 |

| 16 | Italy | 0.788 | 63 | Algeria | 0.720 | 110 | Zimbabwe | 0.605 |

| 17 | Latvia | 0.787 | 64 | Peru | 0.719 | 111 | Togo | 0.602 |

| 18 | Republic of Korea | 0.784 | 65 | Cyprus | 0.719 | 112 | Uganda | 0.601 |

| 19 | Canada | 0.784 | 66 | Jamaica | 0.718 | 113 | Syrian Arab Republic | 0.60 |

| 20 | Netherlands | 0.781 | 67 | Ecuador | 0.718 | 114 | Malawi | 0.598 |

| 21 | New Zealand | 0.779 | 68 | Kazakhstan | 0.717 | 115 | Cameroon | 0.588 |

| 22 | Iceland | 0.779 | 69 | Paraguay | 0.717 | 116 | Sierra Leone | 0.586 |

| 23 | Belgium | 0.778 | 70 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 0.717 | 117 | Zambia | 0.583 |

| 24 | Chile | 0.776 | 71 | Uzbekistan | 0.715 | 118 | Benin | 0.578 |

| 25 | Slovenia | 0.776 | 72 | Arab Republic of Egypt | 0.709 | 119 | Mali | 0.577 |

| 26 | Greece | 0.775 | 73 | Bhutan | 0.705 | 120 | Republic of Congo | 0.574 |

| 27 | Switzerland | 0.774 | 74 | Panama | 0.704 | 121 | Burkina Faso | 0.573 |

| 28 | Hungary | 0.773 | 75 | Islamic Republic of Iran | 0.703 | 122 | Pakistan | 0.573 |

| 29 | Uruguay | 0.772 | 76 | Jordan | 0.701 | 123 | Mozambique | 0.570 |

| 30 | Estonia | 0.771 | 77 | El Salvador | 0.700 | 124 | Burundi | 0.562 |

| 31 | Brazil | 0.770 | 78 | United Arab Emirates | 0.694 | 125 | Ethiopia | 0.560 |

| 32 | Slovakia | 0.770 | 79 | South Africa | 0.692 | 126 | Mauritania | 0.555 |

| 33 | Argentina | 0.763 | 80 | Bolivia | 0.691 | 127 | Guinea | 0.550 |

| 34 | Malta | 0.761 | 81 | Indonesia | 0.691 | 128 | Nigeria | 0.550 |

| 35 | Thailand | 0.760 | 82 | Sri Lanka | 0.689 | 129 | Djibouti | 0.546 |

| 36 | Belarus | 0.757 | 83 | Azerbaijan | 0.686 | 130 | Angola | 0.545 |

| 37 | Ireland | 0.757 | 84 | Nicaragua | 0.685 | 131 | Haiti | 0.544 |

| 38 | Moldova | 0.756 | 85 | Tajikistan | 0.683 | 132 | Sudan | 0.543 |

| 39 | Lithuania | 0.755 | 86 | Philippines | 0.683 | 133 | Liberia | 0.530 |

| 40 | United States | 0.755 | 87 | Honduras | 0.672 | 134 | Madagascar | 0.524 |

| 41 | Israel | 0.749 | 88 | Namibia | 0.667 | 135 | Papua New Guinea | 0.523 |

| 42 | Bulgaria | 0.748 | 89 | Mongolia | 0.664 | 136 | Democratic Republic of Congo | 0.516 |

| 43 | North Macedonia | 0.743 | 90 | Nepal | 0.664 | 137 | Niger | 0.505 |

| 44 | Colombia | 0.741 | 91 | Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela | 0.662 | 138 | Republic of Yemen | 0.498 |

| 45 | Serbia | 0.739 | 92 | Saudi Arabia | 0.661 | 139 | Afghanistan | 0.491 |

| 46 | Costa Rica | 0.738 | 93 | Ghana | 0.660 | 140 | Chad | 0.460 |

| 47 | Luxembourg | 0.737 | 94 | Guatemala | 0.654 | 141 | Central African Republic | 0.445 |

| Rkg | Countries | Avg | Rkg | Countries | Avg | Rkg | Countries | Avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sweden | 0.792 | 48 | Romania | 0.711 | 95 | Senegal | 0.649 |

| 2 | Japan | 0.790 | 49 | North Macedonia | 0.710 | 96 | Guatemala | 0.646 |

| 3 | Finland | 0.784 | 50 | Jordan | 0.709 | 97 | Ivory Coast | 0.640 |

| 4 | Brazil | 0.777 | 51 | Austria | 0.709 | 98 | Luxembourg | 0.639 |

| 5 | United States | 0.773 | 52 | Netherlands | 0.707 | 99 | Iraq | 0.636 |

| 6 | Republic of Korea | 0.768 | 53 | Tunisia | 0.707 | 10 | Nepal | 0.633 |

| 7 | Portugal | 0.767 | 54 | Arab Republic of Egypt | 0.707 | 101 | Lao People’s Democratic Republic | 0.631 |

| 8 | Malaysia | 0.762 | 55 | Mexico | 0.705 | 102 | Syrian Arab Republic | 0.628 |

| 9 | Spain | 0.762 | 56 | Slovakia | 0.705 | 103 | Bangladesh | 0.621 |

| 10 | Australia | 0.760 | 57 | Bulgaria | 0.704 | 104 | Zimbabwe | 0.621 |

| 11 | Canada | 0.759 | 58 | Paraguay | 0.704 | 105 | Tanzania | 0.615 |

| 12 | United Kingdom | 0.759 | 59 | Armenia | 0.703 | 106 | Rwanda | 0.614 |

| 13 | Norway | 0.757 | 60 | Peru | 0.699 | 107 | Zambia | 0.610 |

| 14 | Poland | 0.757 | 61 | Dominican Republic | 0.697 | 108 | Uganda | 0.608 |

| 15 | South Africa | 0.754 | 62 | Albania | 0.697 | 109 | Burma | 0.607 |

| 16 | Denmark | 0.753 | 63 | Lithuania | 0.697 | 110 | Gambia | 0.607 |

| 17 | Thailand | 0.753 | 64 | Ukraine | 0.696 | 111 | Saudi Arabia | 0.606 |

| 18 | Uruguay | 0.751 | 65 | Philippines | 0.694 | 112 | Cameroon | 0.596 |

| 19 | Italy | 0.751 | 66 | Algeria | 0.693 | 113 | Pakistan | 0.594 |

| 20 | China | 0.748 | 67 | Indonesia | 0.689 | 114 | Ethiopia | 0.593 |

| 21 | France | 0.745 | 68 | Belgium | 0.688 | 115 | Sudan | 0.590 |

| 22 | Croatia | 0.743 | 69 | Ghana | 0.688 | 116 | Malawi | 0.590 |

| 23 | Israel | 0.743 | 70 | Botswana | 0.688 | 117 | Angola | 0.589 |

| 24 | Malta | 0.741 | 71 | Gabon | 0.683 | 118 | Mozambique | 0.589 |

| 25 | Iceland | 0.739 | 72 | Uzbekistan | 0.680 | 119 | Mongolia | 0.589 |

| 26 | Germany | 0.737 | 73 | Cyprus | 0.680 | 120 | Togo | 0.587 |

| 27 | Greece | 0.733 | 74 | Moldova | 0.679 | 121 | Turkmenistan | 0.585 |

| 28 | Chile | 0.733 | 75 | Bhutan | 0.679 | 122 | Mali | 0.580 |

| 29 | Latvia | 0.731 | 76 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 0.677 | 123 | Benin | 0.570 |

| 30 | Hungary | 0.730 | 77 | India | 0.675 | 124 | Nigeria | 0.567 |

| 31 | Serbia | 0.729 | 78 | El Salvador | 0.674 | 125 | Djibouti | 0.565 |

| 32 | Colombia | 0.729 | 79 | Slovenia | 0.672 | 126 | Guinea | 0.564 |

| 33 | New Zealand | 0.728 | 80 | Panama | 0.671 | 127 | Republic of Yemen | 0.560 |

| 34 | Costa Rica | 0.728 | 81 | Kazakhstan | 0.671 | 128 | Papua New Guinea | 0.555 |

| 35 | Russia | 0.725 | 82 | Sri Lanka | 0.669 | 129 | Republic of Congo | 0.554 |

| 36 | Morocco | 0.725 | 83 | Belarus | 0.668 | 130 | Madagascar | 0.548 |

| 37 | Turkey | 0.724 | 84 | Ireland | 0.667 | 131 | Liberia | 0.547 |

| 38 | Switzerland | 0.722 | 85 | Namibia | 0.667 | 132 | Democratic Republic of Congo | 0.546 |

| 39 | Argentina | 0.721 | 86 | Honduras | 0.663 | 133 | Sierra Leone | 0.539 |

| 40 | Islamic Republic of Iran | 0.721 | 87 | Bolivia | 0.660 | 134 | Burkina Faso | 0.538 |

| 41 | Georgia | 0.721 | 88 | Azerbaijan | 0.659 | 135 | Mauritania | 0.529 |

| 42 | Ecuador | 0.720 | 89 | Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela | 0.658 | 136 | Haiti | 0.528 |

| 43 | Czech Republic | 0.718 | 90 | Tajikistan | 0.658 | 137 | Burundi | 0.520 |

| 44 | Estonia | 0.715 | 91 | Cambodia | 0.655 | 138 | Niger | 0.513 |

| 45 | Republic of Kyrgyzstan | 0.715 | 92 | Kenya | 0.654 | 139 | Afghanistan | 0.494 |

| 46 | Vietnam | 0.714 | 93 | Nicaragua | 0.651 | 140 | Central African Republic | 0.494 |

| 47 | Jamaica | 0.711 | 94 | United Arab Emirates | 0.650 | 141 | Chad | 0.469 |

| Rkg | Countries | Avg | Rkg | Countries | Avg | Rkg | Countries | Avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Belarus | 0.898 | 48 | Zimbabwe | 0.757 | 95 | Switzerland | 0.711 |

| 2 | Latvia | 0.897 | 49 | Guinea | 0.757 | 96 | Guatemala | 0.707 |

| 3 | Croatia | 0.883 | 50 | Belgium | 0.757 | 97 | Turkey | 0.705 |

| 4 | United Kingdom | 0.879 | 51 | Burundi | 0.756 | 98 | Mozambique | 0.705 |

| 5 | Hungary | 0.870 | 52 | Chile | 0.756 | 99 | Kazakhstan | 0.702 |

| 6 | Czech Republic | 0.866 | 53 | Nepal | 0.755 | 10 | Republic of Congo | 0.700 |

| 7 | Poland | 0.866 | 54 | Ivory Coast | 0.755 | 101 | Vietnam | 0.700 |

| 8 | Greece | 0.847 | 55 | Portugal | 0.754 | 102 | Cyprus | 0.699 |

| 9 | Bulgaria | 0.845 | 56 | Tajikistan | 0.751 | 103 | Chad | 0.699 |

| 10 | Slovak Republic | 0.842 | 57 | Namibia | 0.751 | 104 | Sri Lanka | 0.698 |

| 11 | Slovenia | 0.839 | 58 | Netherlands | 0.750 | 105 | Japan | 0.695 |

| 12 | Moldova | 0.833 | 59 | Syrian Arab Republic | 0.749 | 106 | Burma | 0.693 |

| 13 | Denmark | 0.832 | 60 | Thailand | 0.749 | 107 | Haiti | 0.692 |

| 14 | Finland | 0.828 | 61 | Afghanistan | 0.746 | 108 | Cameroon | 0.690 |

| 15 | Sweden | 0.820 | 62 | Togo | 0.746 | 109 | Bangladesh | 0.687 |

| 16 | Albania | 0.819 | 63 | Uzbekistan | 0.745 | 110 | Niger | 0.687 |

| 17 | Germany | 0.818 | 64 | Azerbaijan | 0.744 | 111 | Australia | 0.685 |

| 18 | Lithuania | 0.817 | 65 | Ireland | 0.738 | 112 | Israel | 0.679 |

| 19 | Ukraine | 0.815 | 66 | Mexico | 0.737 | 113 | Angola | 0.678 |

| 20 | Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela | 0.813 | 67 | Sierra Leone | 0.737 | 114 | Benin | 0.675 |

| 21 | Algeria | 0.809 | 68 | Costa Rica | 0.736 | 115 | Uganda | 0.674 |

| 22 | France | 0.809 | 69 | Peru | 0.736 | 116 | Turkmenistan | 0.672 |

| 23 | Brazil | 0.808 | 70 | Philippines | 0.734 | 117 | New Zealand | 0.671 |

| 24 | Italy | 0.806 | 71 | Rwanda | 0.734 | 118 | China | 0.671 |

| 25 | Romania | 0.806 | 72 | Cambodia | 0.731 | 119 | Serbia | 0.670 |

| 26 | Mali | 0.803 | 73 | Burkina Faso | 0.731 | 120 | Republic of Korea | 0.668 |

| 27 | North Macedonia | 0.801 | 74 | Uruguay | 0.731 | 121 | Tanzania | 0.667 |

| 28 | Tunisia | 0.797 | 75 | Bhutan | 0.731 | 122 | United States | 0.667 |

| 29 | Honduras | 0.796 | 76 | Panama | 0.730 | 123 | Liberia | 0.667 |

| 30 | Gambia | 0.796 | 77 | El Salvador | 0.729 | 124 | Malaysia | 0.665 |

| 31 | Estonia | 0.793 | 78 | Senegal | 0.727 | 125 | Mauritania | 0.661 |

| 32 | Dominican Republic | 0.790 | 79 | Lao People’s Democratic Republic | 0 | 126 | India | 0.66 |

| 33 | Morocco | 0.790 | 80 | Armenia | 0.725 | 127 | Iraq | 0.658 |

| 34 | Austria | 0.790 | 81 | Norway | 0.724 | 128 | Republic of Yemen | 0.652 |

| 35 | Arab Republic of Egypt | 0.782 | 82 | Indonesia | 0.722 | 129 | Democratic Republic of Congo | 0.651 |

| 36 | Colombia | 0.781 | 83 | Pakistan | 0.722 | 130 | Kenya | 0.650 |

| 37 | Ghana | 0.776 | 84 | Botswana | 0.720 | 131 | Jamaica | 0.644 |

| 38 | Paraguay | 0.776 | 85 | Central African Republic | 0.720 | 132 | Canada | 0.640 |

| 39 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 0.773 | 86 | Russia | 0.719 | 133 | Sudan | 0.637 |

| 40 | Gabon | 0.772 | 87 | Malta | 0.718 | 134 | Iceland | 0.633 |

| 41 | Nigeria | 0.772 | 88 | Zambia | 0.715 | 135 | Madagascar | 0.625 |

| 42 | Spain | 0.765 | 89 | Jordan | 0.715 | 136 | Luxembourg | 0.616 |

| 43 | Nicaragua | 0.765 | 90 | Ecuador | 0.715 | 137 | Papua New Guinea | 0.607 |

| 44 | Georgia | 0.762 | 91 | Mongolia | 0.714 | 138 | Ethiopia | 0.602 |

| 45 | Republic of Kyrgyzstan | 0.762 | 92 | South Africa | 0.713 | 139 | Djibouti | 0.582 |

| 46 | Bolivia | 0.761 | 93 | Islamic Republic of Iran | 0.713 | 140 | Saudi Arabia | 0.577 |

| 47 | Argentina | 0.760 | 94 | Malawi | 0.711 | 141 | United Arab Emirates | 0.505 |

| Rkg | Countries | Avg | Rkg | Countries | Avg | Rkg | Countries | Avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Denmark | 0.863 | 48 | Jamaica | 0.746 | 95 | Bangladesh | 0.634 |

| 2 | Norway | 0.860 | 49 | Costa Rica | 0.745 | 96 | India | 0.625 |

| 3 | Iceland | 0.851 | 50 | Bulgaria | 0.744 | 97 | Cambodia | 0.623 |

| 4 | Sweden | 0.849 | 51 | North Macedonia | 0.744 | 98 | Iraq | 0.622 |

| 5 | Finland | 0.849 | 52 | Armenia | 0.741 | 99 | Senegal | 0.618 |

| 6 | Austria | 0.847 | 53 | Dominican Republic | 0.738 | 10 | Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela | 0.615 |

| 7 | Canada | 0.847 | 54 | Vietnam | 0.738 | 101 | Lao People’s Democratic Republic | 0.609 |

| 8 | New Zealand | 0.846 | 55 | Russia | 0.737 | 102 | Kenya | 0.608 |

| 9 | Australia | 0.844 | 56 | Colombia | 0.736 | 103 | Botswana | 0.606 |

| 10 | Germany | 0.842 | 57 | Malaysia | 0.734 | 104 | Ghana | 0.605 |

| 11 | Belgium | 0.842 | 58 | Georgia | 0.732 | 105 | Burma | 0.594 |

| 12 | Luxembourg | 0.838 | 59 | Turkey | 0.731 | 106 | Gabon | 0.590 |

| 13 | Netherlands | 0.836 | 60 | Tunisia | 0.731 | 107 | Tanzania | 0.581 |

| 14 | Japan | 0.836 | 61 | Mexico | 0.731 | 108 | Ivory Coast | 0.576 |

| 15 | Republic of Korea | 0.832 | 62 | Romania | 0.729 | 109 | Uganda | 0.574 |

| 16 | Switzerland | 0.827 | 63 | Albania | 0.728 | 110 | Malawi | 0.566 |

| 17 | Spain | 0.825 | 64 | Uzbekistan | 0.727 | 111 | Sierra Leone | 0.565 |

| 18 | France | 0.824 | 65 | Peru | 0.726 | 112 | Togo | 0.564 |

| 19 | Slovenia | 0.821 | 66 | Republic of Kyrgyzstan | 0.725 | 113 | Benin | 0.552 |

| 20 | Ireland | 0.819 | 67 | Ukraine | 0.725 | 114 | Gambia | 0.551 |

| 21 | Portugal | 0.816 | 68 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 0.723 | 115 | Cameroon | 0.550 |

| 22 | United Kingdom | 0.816 | 69 | Saudi Arabia | 0.722 | 116 | Zimbabwe | 0.546 |

| 23 | Chile | 0.811 | 70 | Ecuador | 0.718 | 117 | Republic of Congo | 0.545 |

| 24 | Czech Republic | 0.809 | 71 | Panama | 0.715 | 118 | Burkina Faso | 0.544 |

| 25 | Italy | 0.806 | 72 | Bhutan | 0.714 | 119 | Mauritania | 0.536 |

| 26 | Uruguay | 0.799 | 73 | Algeria | 0.708 | 120 | Syrian Arab Republic | 0.535 |

| 27 | Estonia | 0.798 | 74 | El Salvador | 0.707 | 121 | Ethiopia | 0.525 |

| 28 | Croatia | 0.795 | 75 | Paraguay | 0.705 | 122 | Burundi | 0.524 |

| 29 | Argentina | 0.790 | 76 | Morocco | 0.70 | 123 | Zambia | 0.524 |

| 30 | Malta | 0.788 | 77 | Sri Lanka | 0.699 | 124 | Djibouti | 0.523 |

| 31 | Slovak Republic | 0.787 | 78 | Mongolia | 0.695 | 125 | Mozambique | 0.515 |

| 32 | Latvia | 0.786 | 79 | Jordan | 0.691 | 126 | Pakistan | 0.513 |

| 33 | Poland | 0.783 | 80 | Islamic Republic of Iran | 0.689 | 127 | Haiti | 0.506 |

| 34 | United Arab Emirates | 0.782 | 81 | Turkmenistan | 0.689 | 128 | Mali | 0.501 |

| 35 | Moldova | 0.779 | 82 | Bolivia | 0.688 | 129 | Sudan | 0.483 |

| 36 | Greece | 0.778 | 83 | Arab Republic of Egypt | 0.687 | 130 | Madagascar | 0.477 |

| 37 | Israel | 0.775 | 84 | Azerbaijan | 0.684 | 131 | Papua New Guinea | 0.476 |

| 38 | United States | 0.772 | 85 | Indonesia | 0.683 | 132 | Liberia | 0.476 |

| 39 | Lithuania | 0.771 | 86 | Nicaragua | 0.680 | 133 | Guinea | 0.474 |

| 40 | Hungary | 0.769 | 87 | Tajikistan | 0.677 | 134 | Angola | 0.474 |

| 41 | Thailand | 0.768 | 88 | Philippines | 0.659 | 135 | Nigeria | 0.468 |

| 42 | Serbia | 0.767 | 89 | Nepal | 0.653 | 136 | Democratic Republic of Congo | 0.453 |

| 43 | Belarus | 0.766 | 90 | South Africa | 0.648 | 137 | Niger | 0.441 |

| 44 | Brazil | 0.753 | 91 | Rwanda | 0.647 | 138 | Republic of Yemen | 0.409 |

| 45 | Kazakhstan | 0.751 | 92 | Guatemala | 0.643 | 139 | Afghanistan | 0.406 |

| 46 | Cyprus | 0.749 | 93 | Namibia | 0.640 | 140 | Chad | 0.376 |

| 47 | China | 0.748 | 94 | Honduras | 0.637 | 141 | Central African Republic | 0.326 |

| Global | Economic | Environment | Social | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRICS+ | 0.693 | 0.704 | 0.689 | 0.688 |

| OECD | 0.779 | 0.734 | 0.765 | 0.811 |

| Difference | 0.086 | 0.030 | 0.076 | 0.123 |

| Continents | Global | Economic | Environmental | Social |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | 0.772 | 0.720 | 0.793 | 0.797 |

| North America | 0.754 | 0.746 | 0.681 | 0.783 |

| Latin America | 0.733 | 0.715 | 0.764 | 0.734 |

| Oceania | 0.698 | 0.681 | 0.654 | 0.722 |

| Central America and the Caribbean | 0.683 | 0.663 | 0.732 | 0.680 |

| Asia | 0.680 | 0.670 | 0.702 | 0.679 |

| Africa | 0.595 | 0.603 | 0.716 | 0.551 |

| Indicator | Initial Values | Normalized Values |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence rate of poverty at USD 2.15/day (2017 PPP, %) | 0.8 | 0.990 |

| Poverty incidence rate at USD 3.65/day (2017 PPP, %) | 1 | 0.990 |

| Prevalence of undernourishment (%) | 2.5 | 1.000 |

| Prevalence of stunting in children under 5 years of age (%) | 2.6 | 0.962 |

| Prevalence of wasting in children under 5 years of age (%) | 0.7 | 0.968 |

| Prevalence of obesity, BMI ≥ 30 (% of adult population) | 17.3 | 0.638 |

| Human trophic level (2–3) | 2.4 | 0.333 |

| Cereal yield (tons per hectare of harvested land) | 4.8 | 0.183 |

| Sustainable nitrogen management index (0–1.41) | 0.8 | 0.429 |

| Maternal mortality rate (per 100,000 live births) | 4.6 | 0.997 |

| Neonatal mortality rate (per 1000 live births) | 1.6 | 0.979 |

| Under-five mortality rate (per 1000 live births) | 2.6 | 0.994 |

| Incidence of tuberculosis (per 100,000 inhabitants) | 4.6 | 0.994 |

| Age-standardized mortality rate due to cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, or chronic respiratory disease in adults aged 30 to 70 (%) | 9 | 0.981 |

| Age-standardized mortality rate attributable to domestic and environmental air pollution (per 100,000 inhabitants) | 15 | 0.973 |

| Deaths from road accidents (per 100,000 inhabitants) | 5 | 0.903 |

| Life expectancy at birth (years) | 82.9 | 0.941 |

| Adolescent fertility rate (births per 1000 women aged 15 to 19) | 2.9 | 0.986 |

| Births attended by skilled health personnel (%) | 99.4 | 0.990 |

| Surviving newborns who received 2 WHO-recommended vaccines (%) | 94 | 0.919 |

| Universal health coverage (UHC) service coverage index (0–100) | 84 | 0.887 |

| Subjective well-being (average score on a scale of 0–10) | 6.2 | 0.762 |

| Net primary school enrolment rate (%) | 98.4 | 0.963 |

| Lower secondary school completion rate (%) | 100.3 | 0.736 |

| Family planning demand satisfied with modern methods (% of women aged 15–49) | 75 | 0.761 |

| Ratio of average years of education received by women and men (%) | 97.4 | 0.751 |

| Ratio of female-to-male labor force participation (%) | 70.2 | 0.640 |

| Seats held by women in the national parliament (%) | 32.3 | 0.527 |

| Population using at least basic services for drinking water (%) | 99.9 | 0.998 |

| Population using at least basic sanitation services (%) | 99.9 | 0.999 |

| Freshwater withdrawal (% of available freshwater resources) | 29.7 | 0.981 |

| Anthropogenic wastewater receiving treatment (%) | 58.8 | 0.588 |

| Water scarcity embedded in imports (m3 H2O eq/capita) | 2638.8 | 0.691 |

| Population with access to electricity (%) | 100 | 1.000 |

| Population with access to clean cooking fuels and technologies (%) | 100 | 1.000 |

| CO2 emissions from fuel combustion for total electricity production (MtCO2/TWh) | 1.2 | 0.924 |

| Share of renewable energy in total final energy consumption (%) | 18.7 | 0.225 |

| Adjusted GDP growth (%) | 15.6 | 0.521 |

| Victims of modern slavery (per 1000 inhabitants) | 3.3 | 0.911 |

| Adults with an account at a bank or other financial institution or with a mobile money service provider (% of population aged 15 and over) | 97.3 | 0.971 |

| Fatal accidents at work incorporated into imports (per million inhabitants) | 1.8 | 0.719 |

| Victims of modern slavery incorporated into imports (per 100,000 inhabitants) | 50.7 | 0.779 |

| Rural population with access to roads usable in all seasons (%) | 99.8 | 0.997 |

| Population using the Internet (%) | 85.1 | 0.839 |

| Mobile broadband subscriptions (per 100 inhabitants) | 95.9 | 0.408 |

| Logistics performance index: infrastructure score (1–5) | 3.8 | 0.778 |

| Times Higher Education University Rankings: average score of the top 3 universities (0–100) | 60.9 | 0.622 |

| Articles published in academic journals (per 1000 inhabitants) | 2.3 | 0.390 |

| Palma Index | 1.3 | 0.903 |

| Average annual concentration of PM2.5 (μg/m3) | 16.3 | 0.840 |

| Access to an improved water source connected to the network (% of urban population) | 100 | 1.000 |

| Municipal solid waste (kg/capita/day) | 17.5 | 0.328 |

| Electronic waste (kg/capita) | 8.4 | 0.683 |

| Air pollution based on production (DALY per 1000 inhabitants) | 7.4 | 0.716 |

| Air pollution associated with imports (DALY per 1000 inhabitants) | 28.1 | 0.816 |

| Nitrogen emissions based on production (kg/capita) | 27.7 | 0.853 |

| Nitrogen emissions associated with imports (kg/capita) | 3.6 | 0.947 |

| CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion and cement production (tCO2/capita) | 5.7 | 0.780 |

| Greenhouse gas emissions embodied in imports (tCO2 per capita) | 4.6 | 0.782 |

| Threats to marine biodiversity embedded in imports (per million inhabitants) | 0.3 | 0.700 |

| Average protected area in terrestrial sites important for biodiversity (%) | 76.7 | 0.772 |

| Average protected area in freshwater sites important for biodiversity (%) | 85.2 | 0.852 |

| Red List Index of species survival (0–1) | 0.87 | 0.721 |

| Imported deforestation (m2/capita) | 12.2 | 0.809 |

| Birth registrations with civil authorities (% of children under 5) | 100 | 1.000 |

| Corruption perception index (0–1) | 56 | 0.558 |

| Exports of major conventional weapons (millions of constant TIV USD per 100,000 inhabitants) | 2 | 0.733 |

| Press freedom index (0–100) | 69.8 | 0.703 |

| Public spending on health and education (% of GDP) | 11.2 | 0.651 |

| Corporate tax haven score (0–100) | 58 | 0.408 |

| Statistical performance index (0–100) | 91.9 | 0.973 |

| Index of countries’ support for UN-based multilateralism (0–100) | 68.4 | 0.702 |

| Global | Economic | Environment | Social | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 0.788 | 0.726 | 0.478 | 0.664 |

| EU27 | 0.779 | 0.709 | 0.490 | 0.659 |

| Difference | 0.009 | 0.017 | −0.012 | 0.005 |

| Rkg | Countries | Avg | Rkg | Countries | Avg | Rkg | Countries | Avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Croatia | 0.754 | 48 | Tajikistan | 0.708 | 95 | Ethiopia | 0.680 |

| 2 | Brazil | 0.743 | 49 | Morocco | 0.708 | 96 | Kenya | 0.680 |

| 3 | Sweden | 0.743 | 50 | Indonesia | 0.707 | 97 | Tanzania | 0.680 |

| 4 | Chile | 0.741 | 51 | Nicaragua | 0.706 | 98 | Switzerland | 0.679 |

| 5 | Poland | 0.740 | 52 | Islamic Republic of Iran | 0.705 | 99 | Togo | 0.673 |

| 6 | Finland | 0.736 | 53 | Algeria | 0.705 | 10 | Namibia | 0.672 |

| 7 | Albania | 0.736 | 54 | Russia | 0.704 | 101 | Cameroon | 0.672 |

| 8 | Colombia | 0.735 | 55 | Lithuania | 0.703 | 102 | Iraq | 0.671 |

| 9 | Greece | 0.732 | 56 | El Salvador | 0.702 | 103 | Pakistan | 0.669 |

| 10 | Portugal | 0.731 | 57 | Belarus | 0.701 | 104 | Ireland | 0.668 |

| 11 | Latvia | 0.730 | 58 | Ukraine | 0.701 | 105 | Botswana | 0.668 |

| 12 | Hungary | 0.730 | 59 | Iceland | 0.70 | 106 | Gambia | 0.667 |

| 13 | United Kingdom | 0.729 | 60 | Azerbaijan | 0.700 | 107 | Zimbabwe | 0.666 |

| 14 | Uruguay | 0.728 | 61 | Bhutan | 0.700 | 108 | Turkmenistan | 0.665 |

| 15 | Czech Republic | 0.728 | 62 | Jamaica | 0.699 | 109 | Zambia | 0.664 |

| 16 | Italy | 0.726 | 63 | Jordan | 0.698 | 110 | Syrian Arab Republic | 0.664 |

| 17 | Argentina | 0.726 | 64 | Bangladesh | 0.698 | 111 | Burma | 0.662 |

| 18 | Georgia | 0.726 | 65 | France | 0.697 | 112 | Benin | 0.661 |

| 19 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 0.725 | 66 | New Zealand | 0.697 | 113 | Malawi | 0.661 |

| 20 | Republic of Korea | 0.724 | 67 | Costa Rica | 0.696 | 114 | Mali | 0.659 |

| 21 | Peru | 0.724 | 68 | Nepal | 0.696 | 115 | Sierra Leone | 0.657 |

| 22 | Vietnam | 0.724 | 69 | Ghana | 0.695 | 116 | Guinea | 0.656 |

| 23 | Bulgaria | 0.723 | 70 | Slovenia | 0.694 | 117 | Israel | 0.653 |

| 24 | Romania | 0.723 | 71 | Sri Lanka | 0.694 | 118 | Mongolia | 0.651 |

| 25 | China | 0.722 | 72 | United States | 0.694 | 119 | Burkina Faso | 0.650 |

| 26 | Denmark | 0.721 | 73 | Honduras | 0.694 | 120 | Angola | 0.650 |

| 27 | Serbia | 0.720 | 74 | Australia | 0.694 | 121 | Papua New Guinea | 0.650 |

| 28 | Moldova | 0.719 | 75 | Canada | 0.694 | 122 | Mozambique | 0.649 |

| 29 | Norway | 0.719 | 76 | Bolivia | 0.694 | 123 | Sudan | 0.648 |

| 30 | Turkey | 0.719 | 77 | Cambodia | 0.693 | 124 | Djibouti | 0.646 |

| 31 | Armenia | 0.718 | 78 | Malta | 0.691 | 125 | Mauritania | 0.645 |

| 32 | Arab Republic of Egypt | 0.717 | 79 | Senegal | 0.691 | 126 | Haiti | 0.644 |

| 33 | Austria | 0.717 | 80 | Lao People’s Democratic Republic | 0.691 | 127 | Republic of The Congo | 0.643 |

| 34 | Slovak Republic | 0.717 | 81 | Guatemala | 0.690 | 128 | Nigeria | 0.641 |

| 35 | Paraguay | 0.716 | 82 | Kazakhstan | 0.689 | 129 | Democratic Republic of Congo | 0.639 |

| 36 | Republic of Kyrgyzstan | 0.715 | 83 | Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela | 0.689 | 130 | Madagascar | 0.638 |

| 37 | Thailand | 0.715 | 84 | Belgium | 0.688 | 131 | Liberia | 0.637 |

| 38 | North Macedonia | 0.714 | 85 | Philippines | 0.687 | 132 | Burundi | 0.637 |

| 39 | Spain | 0.714 | 86 | Panama | 0.687 | 133 | Cyprus | 0.637 |

| 40 | Dominican Republic | 0.714 | 87 | Estonia | 0.687 | 134 | Niger | 0.629 |

| 41 | Germany | 0.713 | 88 | Rwanda | 0.686 | 135 | Republic of Yemen | 0.614 |

| 42 | Japan | 0.713 | 89 | Gabon | 0.685 | 136 | Luxembourg | 0.610 |

| 43 | Ecuador | 0.713 | 90 | Netherlands | 0.683 | 137 | Chad | 0.606 |

| 44 | Mexico | 0.712 | 91 | India | 0.683 | 138 | Saudi Arabia | 0.604 |

| 45 | Tunisia | 0.710 | 92 | Uganda | 0.682 | 139 | Central African Republic | 0.599 |

| 46 | Uzbekistan | 0.710 | 93 | South Africa | 0.682 | 140 | Afghanistan | 0.584 |

| 47 | Malaysia | 0.709 | 94 | Ivory Coast | 0.682 | 141 | United Arab Emirates | 0.550 |

| Rkg | Countries | Rkg | Countries | Rkg | Countries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sweden | 48 | Slovenia | 95 | Gabon |

| 2 | Finland | 48 | Tunisia | 95 | Namibia |

| 3 | Croatia | 50 | Malaysia | 97 | India |

| 4 | United Kingdom | 51 | Paraguay | 98 | Cyprus |

| 5 | Poland | 51 | Arab Republic of Egypt | 99 | Ivory Coast |

| 6 | Portugal | 53 | Mexico | 100 | Botswana |

| 7 | Chile | 54 | Belgium | 100 | Kenya |

| 7 | Latvia | 55 | Ecuador | 102 | Turkmenistan |

| 9 | Denmark | 55 | Russian Federation | 103 | Uganda |

| 9 | Czech Republic | 55 | Netherlands | 104 | Iraq |

| 11 | Italy | 58 | Morocco | 104 | Tanzania |

| 12 | Brazil | 59 | Malta | 106 | Mongolia |

| 13 | Norway | 59 | United States | 107 | Togo |

| 14 | Greece | 61 | Costa Rica | 108 | Gambia |

| 15 | Republic of Korea | 61 | Ukraine | 109 | Cameroon |

| 16 | Hungary | 63 | Algeria | 110 | Zimbabwe |

| 17 | Austria | 64 | Estonia | 111 | Burma |

| 17 | Uruguay | 64 | Uzbekistan | 112 | United Arab Emirates |

| 19 | Germany | 66 | Switzerland | 113 | Ethiopia |

| 20 | Spain | 67 | Islamic Republic of Iran | 114 | Syrian Arab Republic |

| 21 | Japan | 68 | Jamaica | 115 | Pakistan |

| 22 | Argentina | 69 | Indonesia | 116 | Zambia |

| 23 | Colombia | 70 | El Salvador | 117 | Malawi |

| 24 | Albania | 70 | Tajikistan | 118 | Saudi Arabia |

| 25 | Bulgaria | 72 | Bhutan | 118 | Benin |

| 26 | Moldova | 73 | Nicaragua | 120 | Sierra Leone |

| 26 | Slovakia | 74 | Jordan | 121 | Mali |

| 28 | Georgia | 75 | Ireland | 122 | Burkina Faso |

| 29 | Romania | 76 | Azerbaijan | 123 | Guinea |

| 29 | Serbia | 77 | Kazakhstan | 124 | Mozambique |

| 29 | Thailand | 78 | Sri Lanka | 125 | Republic of Congo |

| 32 | France | 79 | Bolivia | 126 | Angola |

| 33 | China | 80 | Israel | 127 | Mauritania |

| 34 | Iceland | 80 | Nepal | 128 | Djibouti |

| 34 | North Macedonia | 82 | Honduras | 129 | Sudan |

| 36 | Vietnam | 82 | Panama | 130 | Burundi |

| 37 | Peru | 84 | Ghana | 130 | Nigeria |

| 38 | Australia | 85 | Bangladesh | 130 | Papua New Guinea |

| 39 | New Zealand | 86 | Philippines | 133 | Haiti |

| 40 | Armenia | 87 | South Africa | 134 | Liberia |

| 40 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 88 | Cambodia | 134 | Madagascar |

| 40 | Turkey | 88 | Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela | 136 | Democratic Republic of Congo |

| 43 | Dominican Republic | 90 | Guatemala | 137 | Niger |

| 44 | Belarus | 91 | Senegal | 138 | Republic of Yemen |

| 44 | Republic of Kyrgyzstan | 92 | Luxembourg | 139 | Chad |

| 46 | Canada | 92 | Lao People’s Democratic Republic | 140 | Afghanistan |

| 46 | Lithuania | 94 | Rwanda | 141 | Central African Republic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Adamo, I.; Della Sciucca, M.; Gastaldi, M.; Lupi, B. Indicator Assessment of Sustainable Development Goals: A Global Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188259

D’Adamo I, Della Sciucca M, Gastaldi M, Lupi B. Indicator Assessment of Sustainable Development Goals: A Global Perspective. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188259

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Adamo, Idiano, Marialucia Della Sciucca, Massimo Gastaldi, and Barbara Lupi. 2025. "Indicator Assessment of Sustainable Development Goals: A Global Perspective" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188259

APA StyleD’Adamo, I., Della Sciucca, M., Gastaldi, M., & Lupi, B. (2025). Indicator Assessment of Sustainable Development Goals: A Global Perspective. Sustainability, 17(18), 8259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188259