Developing and Validating a Data-Driven Application for Street-Accessible Urban Bench Analysis and Planning to Support Evidence-Based Decision Making in Age-Friendly, Sustainable Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Preparation

2.2. Formulating Guidelines for Bench Distribution Assessment

- “Insufficiently age-friendly (moderate)”—a street with several benches, distributed at intervals of more than 150 m;

- “Insufficiently age-friendly (minimal)”—a street containing one bench [27];

- “Not age-friendly”—a street with no benches.

- Each class was reflected using an assigned colour, as in Figure 2.

2.3. Bench-to-Street Assignment

- Filtering Open Street Map geometric data (e.g., polygons and multipolygons) that do not represent sidewalks. Walkways of less than 55 m in length were removed to prevent excessive misassignments; moreover, junctions and pedestrian crossings were removed, since they are not suitable for placing benches.

- Creating a spatial margin for each pavement, with a width of 11 m; such a margin of error makes it possible to assign benches, even when there are minor shifts in the geospatial data.

- Assigning benches iteratively. The algorithm searches through bench data and assigns each bench to a sidewalk (OSM street segment) if it is within its spatial margin. In a situation where a bench can potentially be assigned to more than one sidewalk, the algorithm chooses the closest sidewalk according to Euclidean distance. The benches taken into account during this step include those originally in OSM, as well as any user-specified bench coordinates provided via external files (e.g., collected as part of a field study).

- Dynamically reclassifying segments. Once benches are assigned to street segments, the walkways are classified according to the guidelines detailed in Section 2.2; for this purpose, the tool calculates the spacing between benches to determine a given street’s classification. We note that this is not a simple straight-line measurement. Instead, the algorithm projects each bench’s location onto the street segment’s geometry (a linestring), and then calculates the distance along this linestring path between each consecutive bench; this method ensures that the measurement accurately reflects the true pedestrian walking distance, accounting for any curves in the street. The final classification (e.g., ‘optimal’, ‘convenient’) is based on the maximum path distance found between any two consecutive benches on that segment.

2.4. Metric for Calculating Street Age-Friendliness in Terms of Urban Bench Placement

2.5. An App for Assessing Street Age-Friendliness in Terms of Urban Bench Placement

- User interface: The application features a straightforward design with a functional sidebar for navigation, facilitating seamless switching between the map view and heat map view, as well as map parameter tweaking.

- Map view: At the heart of the app is the map view, incorporating Open Street Map data; it showcases the benches, and the streets are coloured per their respective classes. Users can interact with this map for detailed exploration of specific regions.

- Settings page: The settings page offers customisation options for analysis parameters, including options such as “Admin Level”, with a scale to change the administrative division level from 1 to 5 (where lower values are more general, e.g., city; and higher values are more specific, e.g., neighbourhood), as well as the ability to upload custom location data for the benches or demographic heatmap.

- The following functionalities can also be accessed in the settings page: “Map Options”, which allows the user to show a heatmap overlay and show or hide benches; “Street display options”, which enables the user to show or hide the selection of individual street classes, with a slider for setting the optimal and convenient distances; and “Advanced Road Options”, allowing the user to customise which Open Street Map ‘highway’ types are included in the analysis. By default, we focused on the most pedestrian-friendly environments, those safer and more comfortable for older adults; however, every region is different, so it is also possible to consider additional road, path, or infrastructure types depending on local conditions, data availability, and specific goals.

- Simulation: This feature enables the user to initiate a simulation that estimates the enhancement of the Street Age-Friendliness Score in terms of urban bench placement, taking into account a specified budget and the cost of a single bench; both settings are entered into the application and can be updated at any time. The current approach employs a heuristic method through which to identify the longest street segments that fall short of the minimum street age-friendliness class in terms of the urban bench placement criteria; the existing benches are displayed in grey, and the suggested ones in brown (Figure 4).

- The map’s appearance can be individually customised by changing the colour palette for street classes.

2.6. Comparison of Five Poznan Neighbourhoods

- Density (number of seniors/km2);

- Number of street segments (sections depending on the street layouts, e.g., located between cross-sections; sections were downloaded from Open Street Map and can vary for given city or country);

- Number of age-friendly streets;

- Percentages of the following:

- ⚬

- Age-friendly (optimal) streets;

- ⚬

- Age-friendly (convenient) streets;

- ⚬

- Insufficiently age-friendly (moderate) streets;

- ⚬

- Insufficiently age-friendly (minimal) streets;

- ⚬

- Non-age-friendly streets.

- Average distance (m) between benches in a given neighbourhood.

2.7. Comparative Analysis of Selected Age-Friendly Polish and European Cities

- Number of street segments;

- Number of age-friendly streets;

- Percentages of the following:

- ⚬

- Age-friendly (optimal) streets;

- ⚬

- Age-friendly (convenient) streets;

- ⚬

- Insufficiently age-friendly (moderate) streets;

- ⚬

- Insufficiently age-friendly (minimal) streets;

- ⚬

- Non-age-friendly streets.

- Average distance (m) between benches in a given urban area.

2.8. Simulation of Bench Distribution

- Generating candidate locations. On each street, potential bench location points are generated at intervals adapted to the street length, with the number of candidates proportional to the street length.

- Iteratively selecting the best locations. In each step, the algorithm selects a location that maximises the distance from existing benches, improving the areas with the greatest deficits.

- Dynamically updating the distances for subsequent candidates and the street age-friendliness classifications after adding each bench.

- Ending the simulation when there are no more bench placement candidates, or a user-specified budget is exhausted.

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Analysis of Five Poznan Neighbourhoods

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Polish Cities from Age-Friendly Cities Network

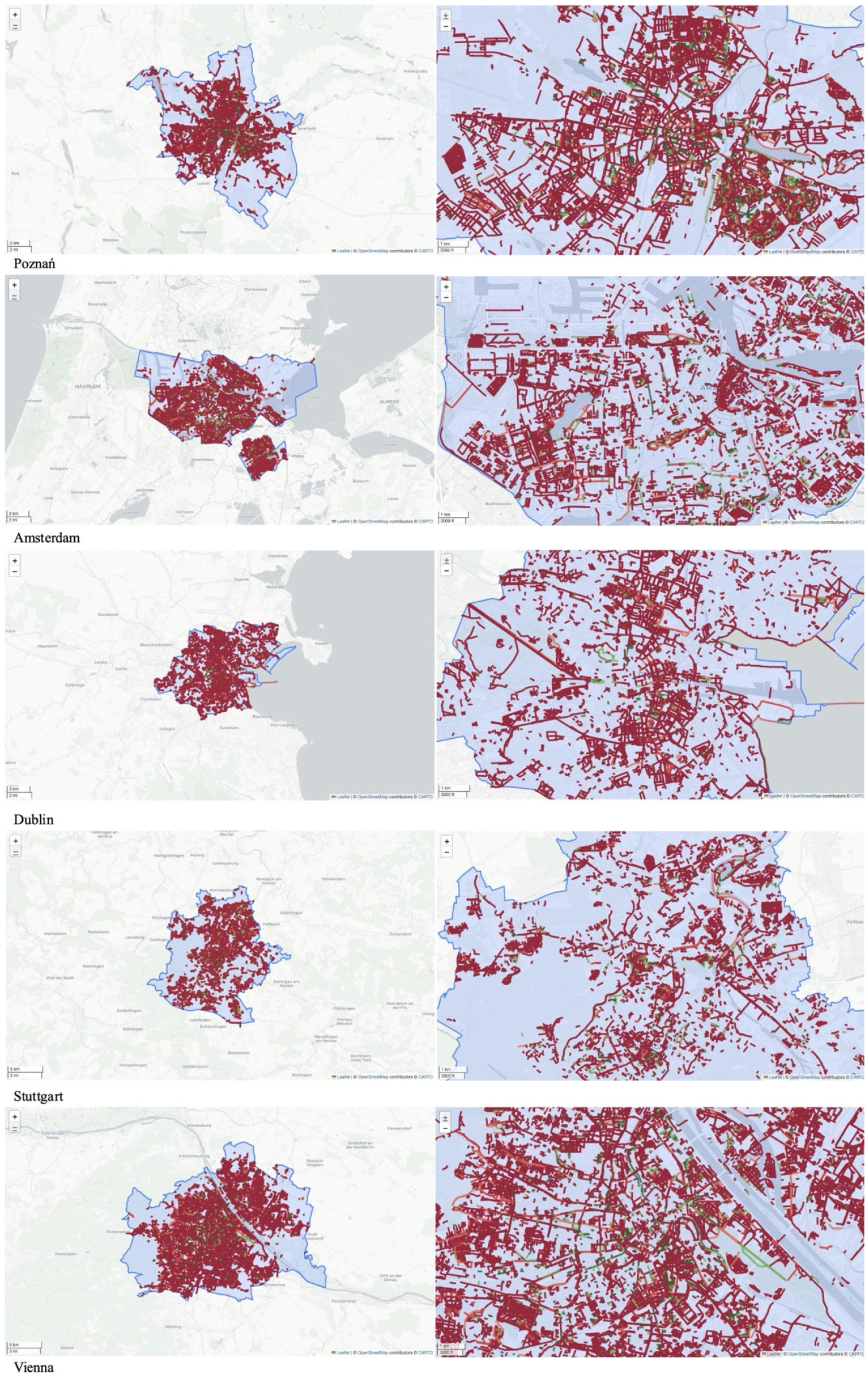

3.3. Comparative Analysis of European Cities from the Age-Friendly Cities Network

3.4. Proposed Standards for the Number and Distribution of Age-Friendly Benches’

4. Discussion

- Status (city centre street, periphery, recreational area, etc.) related to the volume of trips made on foot;

- Terrain (flat or sloped);

- Presence of greenery on the street (flowers, flowerbeds, nearby park, etc.);

- Other amenities (public toilet, shelter, lighting, drinking fountain, etc.);

- Presence of an important function of a 15 min city within 700 m.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. 2022. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/World-Population-Prospects-2022 (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- World Economic Forum. Global Risks Report 2025, 20th ed. 2025. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report-2025/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Lee, J.Y.; Kim, H. Projection of future temperature-related mortality due to climate and demographic changes. Environ. Int. 2016, 94, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, D.W.; Barnett, A.; Nathan, A.; Van Cauwenberg, J.; Cerin, E.; Council on Environment and Physical Activity (CEPA)—Older Adults working group. Built environmental correlates of older adults’ total physical activity and walking: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beard, J.R.; Petitot, C. Ageing and Urbanization: Can Cities be Designed to Foster Active Ageing? Public Health Rev. 2010, 32, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS The New EU Urban Mobility Framework, COM/2021/811 final. Publications Office of the EU. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/ad816b47-8451-11ec-8c40-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- About the Initiative—European Union. Available online: https://new-european-bauhaus.europa.eu/about/about-initiative_en (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Moreno, C. 15-Minutowe Miasto. Jak Uratować Nasz Czas i Planetę [The 15-Minute City: A Solution to Saving Our Time and Our Planet]; Wysoki Zamek: Kraków, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-minute city”: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Kim, J.-H. Variations in Ageing in Home and Ageing in Neighbourhood. Aust. Geogr. 2017, 48, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbicka, M. Analiza parametrów czasowo-przestrzennych chodu u słuchaczy Uniwersytetu Trzeciego Wieku. Zesz. Nauk. Coll. Witelona 2022, 4, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottoni, C.; Sims-Gould, J.; Winters, M.; Heijnen, M.; McKay, H. “Benches become like porches”: Built and social environment influences on older adults’ experiences of mobility and well-being. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 169, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C.; Ishikawa, S.; Silverstein, M.; Jacobson, M.; Fiksdahl-King, I.; Angel, S. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Mehaffy, M.; Kryazheva, Y.; Rudd, A.; Salingaros, N. A New Pattern Language for Growing Regions: Places, Networks, Processes; Sustasis Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ptak-Wojciechowska, A. Analiza Wybranych Narzędzi do Ewaluacji Jakości Życia w Mieście w Kontekście Zmian Społeczno-Demograficznych. Ph.D. Thesis, Politechnika Poznańska, Poznań, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gawlak, A.; Matuszewska, M.; Ptak, A. Inclusiveness of Urban Space and Tools for the Assessment of the Quality of Urban Life—A Critical Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptak-Wojciechowska, A. Zróżnicowanie etykiet i narzędzi służących do oceny i porównywania miast. Zesz. Nauk. Politech. Poznańskiej. Archit. Urban. Archit. Wnętrz 2023, 17, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Moreira, B.; Cristina de Souza Andrade, A.; de Carvalho Bastone, A.; Simone de Souza Vasconcelos, K.; Teixeira, V.B.D.; Xavier, C.C.; Proietti, F.A.; Caiaffa, W.T. Individual characteristics, perceived neighborhood, and walking for transportation among older Brazilian people residing in a large urban area. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2022, 12, 2620–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, M.; da Silva, A.; Santos, R.D.; d ‘Orsi, E.; Bestetti, M.; Perracini, M. How Do Older Adults Living in the Community in Brazil Perceive Walkability in the Context of Sidewalks? J. Aging Environ. 2024, 38, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.R.; Werner, P.; Doron, I.; HaGani, N.; Benvenisti, Y.; King, A.C.; Winter, S.J.; Sheats, J.L.; Garber, R.; Motro, H.; et al. Exploring the Objective and Perceived Environmental Attributes of Older Adults’ Neighborhood Walking Routes: A Mixed Methods Analysis. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2017, 25, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Matsuoka, R.H.; Tsai, K.-C. Spatial measurement of mobility barriers: Improving the environment of community-dwelling older adults in Taiwan. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2015, 23, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Padillo, A.; Oestreich, L.; Torres, T.; Rhoden, P.; Larranaga, A.; Cybis, H. Weighted assessment of barriers to walking in small cities: A Brazilian case. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 109, 103392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Yang, D.; Owen, N.; Van Dyck, D. The built environment and mental health among older adults in Dalian: The mediating role of perceived environmental attributes. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 311, 115333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Holle, V.; Van Cauwenberg, J.; Gheysen, F.; Van Dyck, D.; Deforche, B.; Van de Weghe, N.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. The Association between Belgian Older Adults’ Physical Functioning and Physical Activity: What Is the Moderating Role of the Physical Environment? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Tang, X.; Yang, L. Spatially varying associations between the built environment and older adults’ propensity to walk. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1003791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauwenberg, J.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Clarys, P.; Nasar, J.; Salmon, J.; Goubert, L.; Deforche, B. Street characteristics preferred for transportation walking among older adults: A choice-based conjoint analysis with manipulated photographs. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookfield, K.; Tilley, S. Using virtual street audits to understand the walkability of older adults’ route choices by gender and age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tournier, I.; Dommes, A.; Cavallo, V. Review of safety and mobility issues among older pedestrians. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 91, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Fu, Y.; Xu, Y. Satisfaction with neighbourhood environment moderates the associations between objective neighbourhood environment and leisure-time physical activity in older adults in Beijing, China. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglione, F.; Gargiulo, C.; Zucaro, F. Where can the elderly walk? A spatial multi-criteria method to increase urban pedestrian accessibility. Cities 2022, 127, 103724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauwenberg, J.; Nathan, A.; Barnett, A.; Barnett, D.W.; Cerin, E.; Council on Environment and Physical Activity (CEPA)—Older Adults Working Group. Relationships Between Neighbourhood Physical Environmental Attributes and Older Adults’ Leisure-Time Physical Activity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1635–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerin, E.; Nathan, A.; van Cauwenberg, J.; Barnett, D.W.; Barnett, A.; Council on Environment and Physical Activity (CEPA)—Older Adults working group. The neighbourhood physical environment and active travel in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moniruzzaman, M.; Paez, A. An investigation of the attributes of walkable environments from the perspective of seniors in Montreal. J. Transp. Geogr. 2016, 51, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, S.; Ruiz, T.; Mars, L. A qualitative study on the role of the built environment for short walking trips. Transp. Res. Part F-Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2015, 33, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cain, K.L.; Conway, T.L.; Gavand, K.A.; Millstein, R.A.; Geremia, C.M.; Frank, L.D.; Saelens, B.E.; Glanz, K.; King, A.C. Is your neighborhood designed to support physical activity? A brief streetscape audit tool. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2015, 12, E141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Heng, C.K.; Fung, J.C. Using walk-along interviews to identify environmental factors influencing older adults’ out-of-home behaviors in a high-rise, high-density neighborhood. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookfield, K.; Thompson, C.W.; Scott, I. The uncommon impact of common environmental details on walking in older adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocki, M. Standardy Dostępności dla Miasta Gdyni; Centrum Projektowania Uniwersalnego, Politechnika Gdańska Wydział Architektury: Gdańsk, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nowoczesne i Estetyczne Ławki Dla Ulicy Starodworcowej—BO Gdynia. Available online: https://bo.gdynia.pl/projects/nowoczesne-i-estetyczne-lawki-dla-ulicy-starodworcowej/ (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2019, in the Sustainable Development Goals Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, D.R.; Pucher, J.; Buehler, R.; Thompson, D.L.; Crouter, S.E. Walking, cycling, and obesity rates in Europe, North America, and Australia. J. Phys. Act. Health 2008, 5, 795–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Global Network for Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: Looking Back Over the Last Decade, Looking Forward to the Next; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. About the Global Network for Age-friendly Cities and Communities—Age-Friendly World. Available online: https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/who-network/ (accessed on 17 May 2023).

- City of Poznan—Age-Friendly World. Available online: https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/network/city-of-poznan/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Browse the Network—Age-Friendly World. Available online: https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/network/ (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Garcia, D.A.; Cumo, F.; Pennacchia, E.; Pennucci, V.S.; Piras, G.; De Notti, V.; Roversi, R. Assessment of a urban sustainability and life quality index for elderly. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2017, 12, 908–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptak-Wojciechowska, A. Use of the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) method to assess the urban quality of life of seniors in terms of architectural and urban planning aspects. Architectus 2024, 4, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnamed Street—Streetmix. Available online: https://streetmix.net/-/2728279/ (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Badii, C.; Bellini, P.; Cenni, D.; Chiordi, S.; Mitolo, N.; Nesi, P.; Paolucci, M. Computing 15MinCityIndexes on the Basis of Open Data and Services. In Computational Science and Its Applications–ICCSA 2021; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Misra, S., Garau, C., Blečić, I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Tarantino, E., Torre, C.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, L.; D’Autilia, R.; Marrone, P.; Montella, I. Graph Representation of the 15-Minute City: A Comparison between Rome, London, and Paris. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tota-Stawarczyk, P.; Rymsza, B.; Kasperczak, K.; Miśkowiec, M. Standardy Dostępności Architektonicznej dla Miasta Stołecznego Warszawy, City of Warsaw: Warsaw, Poland, 2022. Available online: https://wsparcie.um.warszawa.pl/dostepnosc-architektoniczna (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Newton, R.; Ormerod, M. ‘Seating’, Inclusive Design for Getting Outdoors (I’DGO). 2012. Available online: https://www.idgo.ac.uk/design_guidance/pdf/DSOPM-Seating-120820.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Department for Transport. Inclusive Mobility: A Guide to Best Practice on Access to Pedestrian and Transport Infrastructure. 2005. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/inclusive-mobility (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Portal Systemu Informacji Przestrzennej Miasta Poznania. Available online: https://sipgeoportal.geopoz.poznan.pl (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Network for Age-Friendly Cities and Communities, WHO Maps ArcGIS. Available online: https://who.maps.arcgis.com/apps/instant/minimalist/index.html?appid=66799d4ec039487e8ef8367f0254a99a (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Bloom, L.B. The 20 Best Cities to Live in the World, Ranked in A 2024 Report, Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/laurabegleybloom/2024/06/26/the-20-best-cities-to-live-in-the-world-ranked-in-a-2024-report/ (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Department for Transport. Manual for Streets, Thomas Telford Publishing. 2007. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/manual-for-streets (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- World Health Organization. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Lu, S.; Chan, O.F.; Chui, C.H.K.; Ho, H.C.; Song, Y.; Cheng, W.; Chiu, R.L.H.; Webster, C.; et al. Understanding the long-term effects of public open space on older adults’ functional ability and mental health. Build. Environ. 2023, 234, 110126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, N.; Kaufman, P. Examining the role of urban street design in enhancing community engagement: A literature review. Health Place 2016, 41, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Lu, Z.; Yu, C.-Y.; Lee, C.; Mann, G. Walkable communities: Impacts on residents’ physical and social health. World Health Des. 2013, 6, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, A.; Cerin, E.; Ching, C.S.-K.; Johnston, J.M.; Lee, R.S.Y. Neighbourhood environment, sitting time and motorised transport in older adults: A cross-sectional study in Hong Kong. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburgt, M.; Asselman, J.; Trakul-Masłowska, M.; Kubecka, M.; Mayer, P.; Panek, P. D2. 3 Requirements of Primary and Secondary End-Users-A Toilet for Me Envisioned, 2021. Available online: https://repositum.tuwien.at/handle/20.500.12708/40489 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Turel, H.S.; Yigit, E.M.; Altug, I. Evaluation of elderly people’s requirements in public open spaces: A case study in Bornova District (Izmir, Turkey). Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 2035–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chartowo | Grunwald Południe | Piątkowo | Rataje | Św. Łazarz | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Total area (km2) | 4.47 | 3.82 | 3.83 | 5.17 | 3.67 |

| Total street length (km) | 107.63 | 91.18 | 119.02 | 168.94 | 83.30 | |

| Number of street segments | 581 | 473 | 783 | 918 | 316 | |

| Current number of benches | 966 | 405 | 467 | 1432 | 569 | |

| Average distance to the nearest bench (m) | 20.34 | 18.01 | 18.18 | 18.46 | 20.58 | |

| Number of seniors (aged 60+) | 7053 | 6622 | 9255 | 8531 | 7424 | |

| Density (no. of seniors/km2) | 1576.61 | 1732.77 | 2415.75 | 1649.15 | 2023.45 | |

| Percentage of Total Length [%] | Age-friendly (optimal) streets | 11.64 | 5.67 | 6.25 | 10.86 | 6.63 |

| Age-friendly (convenient) streets | 18.69 | 8.94 | 10.80 | 18.18 | 11.47 | |

| Insufficiently age-friendly (moderate) streets | 6.35 | 5.04 | 1.19 | 5.44 | 8.66 | |

| Insufficiently age-friendly (minimal) streets | 9.54 | 11.07 | 8.98 | 7.89 | 12.51 | |

| Non-age-friendly streets | 53.79 | 69.28 | 72.78 | 57.62 | 60.73 | |

| Index | Overall Street Age-Friendliness (%) | 25.17 | 12.64 | 13.28 | 23.30 | 15.98 |

| Benches needed (number) to achieve class: | Age-friendly (optimal) | 1845 | 1800 | 2424 | 2966 | 1528 |

| Age-friendly (convenient) | 629 | 657 | 920 | 1043 | 512 | |

| Insufficiently age-friendly (moderate) | 523 | 542 | 828 | 881 | 354 | |

| Insufficiently age-friendly (minimal) | 349 | 361 | 595 | 606 | 195 |

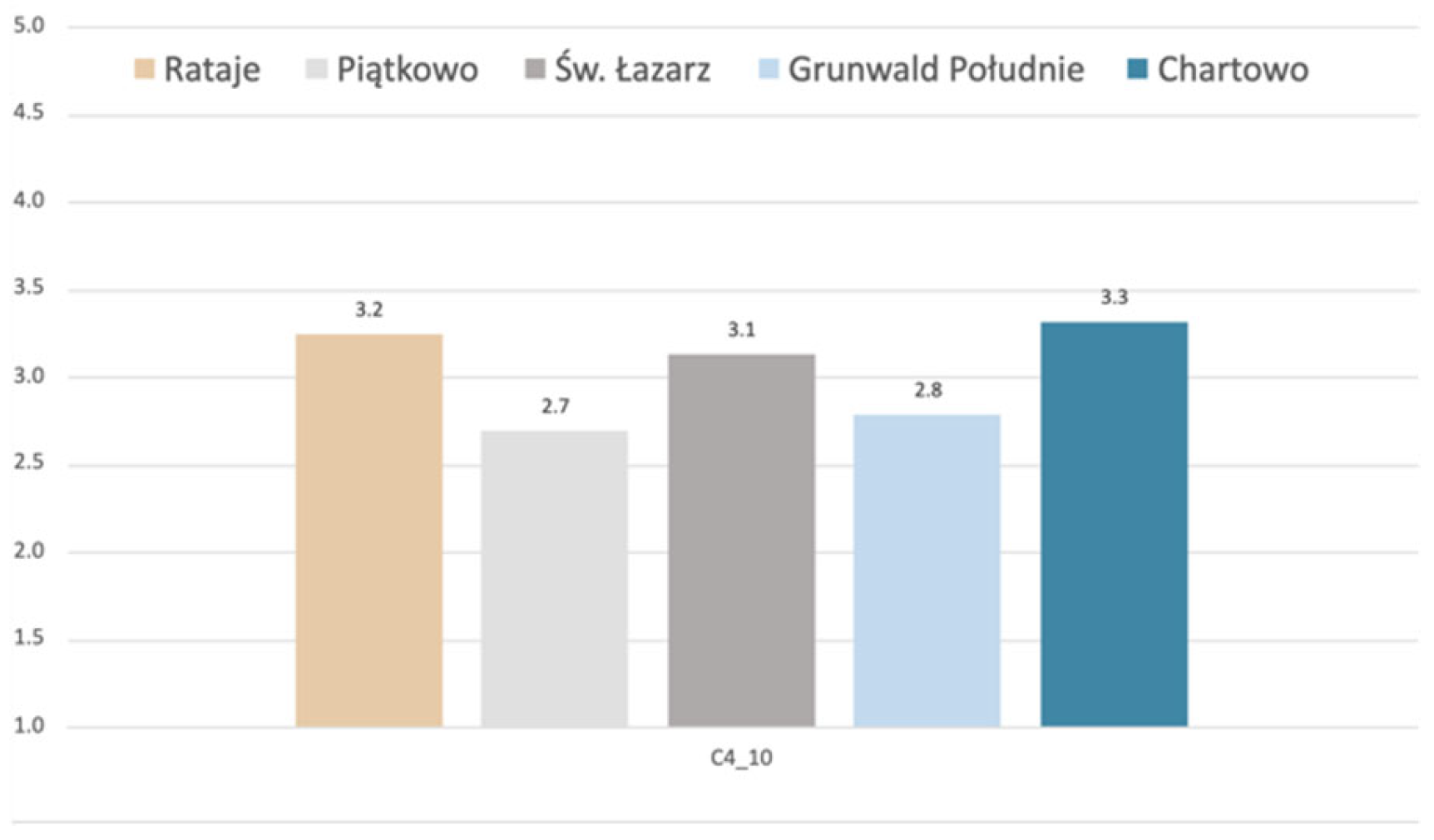

| Neighbourhood | Senior Assessments Normalised | Expert Assessments Normalised | Tool: “Overall Street-Age Friendliness” |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chartowo | 66% | 49% | 25.17% |

| Grunwald Południe | 56% | 60% | 12.64% |

| Piątkowo | 54% | 60% | 13.28% |

| Rataje | 64% | 65% | 23.30% |

| Św. Łazarz | 62% | 61% | 15.98% |

| Location | Poznań | Gdańsk | Gdynia | Kraków | Wrocław | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Total area (km2) | 261.90 | 258 (749.55) | 135 (432.41) | 295.22 | 276.75 |

| Total street length (km) | 2151.32 | 2241.95 | 786.45 | 2781.30 | 2533.33 | |

| Number of street segments | 10,727 | 12,653 | 4596 | 15,885 | 15,179 | |

| Current number of benches | 9155 | 6549 | 2040 | 8657 | 6092 | |

| Average distance to the nearest bench (m) | 17.60 | 23.57 | 24.02 | 16.18 | 12.05 | |

| Percentage of Total Length (%) | Age-friendly (optimal = 50 m) streets | 5.08 | 4.01 | 3.28 | 4.45 | 2.84 |

| Age-friendly (convenient) streets | 6.44 | 7.06 | 4.82 | 4.87 | 2.91 | |

| Insufficiently age-friendly (moderate) streets | 3.18 | 3.21 | 3.03 | 1.73 | 0.65 | |

| Insufficiently age-friendly (minimal) streets | 4.48 | 6.00 | 5.54 | 2.76 | 2.07 | |

| Non-age-friendly streets | 80.82 | 79.72 | 83.38 | 86.19 | 91.52 | |

| Index | Overall Street Age-Friendliness (%) | 9.73 | 9.02 | 6.97 | 7.80 | 4.79 |

| Benches needed (number) to achieve class: | Age-friendly (optimal) | 43,799 | 46,732 | 16,827 | 58,837 | 55,697 |

| Age-friendly (convenient) | 16,506 | 17,796 | 6535 | 22,973 | 22,258 | |

| Insufficiently age-friendly (moderate) | 13,030 | 14,843 | 5550 | 19,325 | 19,333 | |

| Insufficiently age-friendly (minimal) | 8861 | 10,490 | 3977 | 13,764 | 13,946 |

| Locations | Poznań | Amsterdam | Dublin | Stuttgart | Vienna | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Total Area (km2) | 261.90 | 219.17 | 123.92 | 177.80 | 347.98 |

| Statistic | Total street length (km) | 2151.32 | 1510.83 | 1088.34 | 961.98 | 3761.54 |

| Number of street segments | 10,727 | 9476 | 4549 | 6471 | 20,405 | |

| Current number of benches | 9155 | 5012 | 1173 | 5320 | 11,610 | |

| Average distance to the nearest bench (m) | 17.60 | 22.27 | 31.99 | 23.70 | 16.21 | |

| Percentage of Total Length | Age-friendly (optimal) streets | 5.08 | 2.92 | 1.08 | 2.50 | 3.05 |

| Age-friendly (convenient) streets | 6.44 | 6.73 | 2.74 | 6.15 | 4.05 | |

| Insufficiently age-friendly (moderate) streets | 3.18 | 2.98 | 3.24 | 2.80 | 2.89 | |

| Insufficiently age-friendly (minimal) streets | 4.48 | 4.33 | 2.22 | 5.35 | 4.64 | |

| Non-age-friendly streets | 80.82 | 83.05 | 90.72 | 83.20 | 85.37 | |

| Index | Overall Street Age-Friendliness (%) | 9.73 | 7.58 | 3.26 | 7.00 | 6.11 |

| Benches needed (number) to achieve class: | Age-friendly (optimal) | 43,799 | 32,486 | 23,358 | 21,066 | 80,616 |

| Age-friendly (convenient) | 16,506 | 12,656 | 8839 | 8301 | 31,272 | |

| Insufficiently age-friendly (moderate) | 13,030 | 11,110 | 6127 | 7444 | 25,528 | |

| Insufficiently age-friendly (minimal) | 8861 | 8263 | 4237 | 5629 | 18,073 |

| Chartowo | Grunwald Południe | Piątkowo | Rataje | Św. Łazarz | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | Overall Street Age-Friendliness (%) for 50 m | 25.17 | 12.64 | 13.28 | 23.30 | 15.98 |

| Index | Overall Street Age-Friendliness (%) for 100 m | 33.30 | 17.39 | 18.37 | 31.27 | 22.84 |

| Benches needed | Age-friendly (optimal) for 50 m | 1845 | 1800 | 2424 | 2966 | 1528 |

| Age-friendly (optimal) for 100 m | 895 | 930 | 1256 | 1456 | 751 | |

| Poznań | Gdańsk | Gdynia | Kraków | Wrocław | ||

| Index | Overall Street Age-Friendliness (%) for 50 m | 9.73 | 9.02 | 6.97 | 7.80 | 4.79 |

| Index | Overall Street Age-Friendliness (%) for 100 m | 12.89 | 12.77 | 9.91 | 10.12 | 6.18 |

| Benches needed | Age-friendly (optimal) for 50 m | 43,799 | 46,732 | 16,827 | 58,837 | 55,697 |

| Age-friendly (optimal) for 100 m | 22,977 | 24,449 | 8929 | 31,364 | 30,146 | |

| Poznań | Amsterdam | Dublin | Stuttgart | Vienna | ||

| Index | Overall Street Age-Friendliness (%) for 50 m | 9.73 | 7.58 | 3.26 | 7.00 | 6.11 |

| Index | Overall Street Age-Friendliness (%) for 100 m | 12.89 | 11.03 | 4.85 | 10.45 | 8.41 |

| Benches needed | Age-friendly (optimal) for 50 m | 43,799 | 32,486 | 23,358 | 21,066 | 80,616 |

| Age-friendly (optimal) for 100 m | 22,977 | 17,223 | 12,316 | 11,149 | 42,917 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ptak-Wojciechowska, A.; Gawlak, A.; Maciejewski, P.; Romaniv, D.; Skrzypek, M.; Brzeziński, D.; Stefanowski, J. Developing and Validating a Data-Driven Application for Street-Accessible Urban Bench Analysis and Planning to Support Evidence-Based Decision Making in Age-Friendly, Sustainable Cities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8251. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188251

Ptak-Wojciechowska A, Gawlak A, Maciejewski P, Romaniv D, Skrzypek M, Brzeziński D, Stefanowski J. Developing and Validating a Data-Driven Application for Street-Accessible Urban Bench Analysis and Planning to Support Evidence-Based Decision Making in Age-Friendly, Sustainable Cities. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8251. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188251

Chicago/Turabian StylePtak-Wojciechowska, Agnieszka, Agata Gawlak, Patryk Maciejewski, Dmytro Romaniv, Michał Skrzypek, Dariusz Brzeziński, and Jerzy Stefanowski. 2025. "Developing and Validating a Data-Driven Application for Street-Accessible Urban Bench Analysis and Planning to Support Evidence-Based Decision Making in Age-Friendly, Sustainable Cities" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8251. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188251

APA StylePtak-Wojciechowska, A., Gawlak, A., Maciejewski, P., Romaniv, D., Skrzypek, M., Brzeziński, D., & Stefanowski, J. (2025). Developing and Validating a Data-Driven Application for Street-Accessible Urban Bench Analysis and Planning to Support Evidence-Based Decision Making in Age-Friendly, Sustainable Cities. Sustainability, 17(18), 8251. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188251