Toward a Disciplinary Knowledge–Led Approach for Sustainable Heritage-Based Art Districts in Shanghai

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Constructing the Multidimensional Explanatory Conceptual Framework: EBDA

2.1. Multidimensional Frameworks in the Literature

2.2. Evidence-Based Disciplinary Assessment as a Framework for Sustainable Heritage

2.2.1. Institutional and Governance Sustainability

2.2.2. Cultural Sustainability

2.2.3. Social Sustainability

2.2.4. Environmental Sustainability

2.2.5. Economic Sustainability

| The Corresponding Subsection No. | Dimensions | Criteria | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.2.1 | Institutional and Governance Sustainability | 2.2.1.1 Assessment of compatibility with existing cultural relics laws and alignment with elite-led heritage assessment frameworks in China. | Evans [21]; Vitkova and Silaci [9]; Chapple et al. [14]; De Luca et al. [24]; Kong [16]; Santagata [15]; Lazzeretti [10]. |

| 2.2.1.2 Potential for expanding state-sanctioned heritage narratives toward a more inclusive valuation framework in China. | |||

| 2.2.1.3 Recognition of experts, artists, and cultural practitioners as participants in dialog between top-down planning and grassroots cultural memory. | |||

| 2.2.1.4 Valuation of the mediating role of narratives between state objectives and local identity, contributing to institutional legitimacy and cultural governance. | |||

| 2.2.1.5 Integration of art-historical evidence into planning as a means of strengthening institutional resilience by linking symbolic capital with policy frameworks. | |||

| 2.2.2 | Cultural Sustainability | 2.2.2.1 Minimum threshold (e.g., 25%) of land use in the core preservation area reflecting Republican-period artistic life. | IJECESS [25]; Stevenson [26]; Paddison [27]; Bassett [28]; Blandy and Fenn [29]; Kong [16,30]; Yung et al. [20]. |

| 2.2.2.2 Inclusion of educational programming on the history and achievements of Republican-period Shanghai artists. | |||

| 2.2.2.3 Valuation of everyday cultural practices, creative processes, and social environments of Republican-period artists. | |||

| 2.2.2.4 Visibility of local cultural identity and esteem linked to Republican-period art history through commemorative and public cultural forms. | |||

| 2.2.2.5 Inclusion of local artists, historians, and residents in heritage-related planning, programming, and interpretation. | |||

| 2.2.2.6 A contemporary reinterpretation of Republican-period artistic traditions within ongoing cultural activities. | |||

| 2.2.3 | Environmental Sustainability | 2.2.3.1 Retention of the traditional street and lane network characteristic of Republican-period artists’ neighborhoods, including the spatial configuration of pathways and enclosures. | Evans [21]; Johnson and Thomas [32]; Zhang et al. [33]; Yung et al. [20]; Montgomery [34,35]; Roodhouse [36]. |

| 2.2.3.2 Conservation of the original architectural styles and defining elements of Republican-period artists’ residences. | |||

| 2.2.3.3 Preservation of the overall spatial integrity and continuity of the Republican-period art district, maintaining its historical coherence as a unified cultural landscape. | |||

| 2.2.3.4 High spatial permeability, ensuring accessible and well-connected pedestrian pathways to key artistic and cultural venues within the district. | |||

| 2.2.4 | Social Sustainability | 2.2.4.1 Collaborative development frameworks involving art historians, artists, art organizations, and hopefully local residents. | IJECESS [25]; Stevenson [26]; Paddison [27]; Lopes et al. [6]; Baek et al. [31]; Darchen [13]. Sacco and Blessi [12]; Yung et al. [20]. |

| 2.2.4.2 Public participation mechanisms enabling art history specialists and local residents to comment on and influence project planning and implementation. | |||

| 2.2.4.3 Capacity-building programs in heritage restoration and cultural skills for local residents. | |||

| 2.2.4.4 Preservation and activation of collective memory and sense of place associated with Republican-period artistic heritage. | |||

| 2.2.4.5 Provision of affordable creative workspaces for emerging artists to promote inclusiveness and intergenerational cultural exchange. | |||

| 2.2.4.6 Strengthening of social networks and community trust. | |||

| 2.2.5 | Economic Sustainability | 2.2.5.1 Supporting a vibrant creative economy rooted in local cultural production. | Miles [37]; Skrede [4]; Garcia [22]; Landry [38]; Florida [39]; Maggiore and Vellecco [18]; Lazzeretti et al. [10]. |

| 2.2.5.2 Sustaining a diverse job market for artists and creative professionals, building on the legacy of Republican-period Shanghai. | |||

| 2.2.5.3 Providing affordable living and working spaces for economically marginalized artists. | |||

| 2.2.5.4 Leveraging Republican-period artistic heritage as cultural capital for tourism and cultural consumption. |

3. Research Methods

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Advancing Institutional and Governance Sustainability

4.2. Realizing Cultural Sustainability

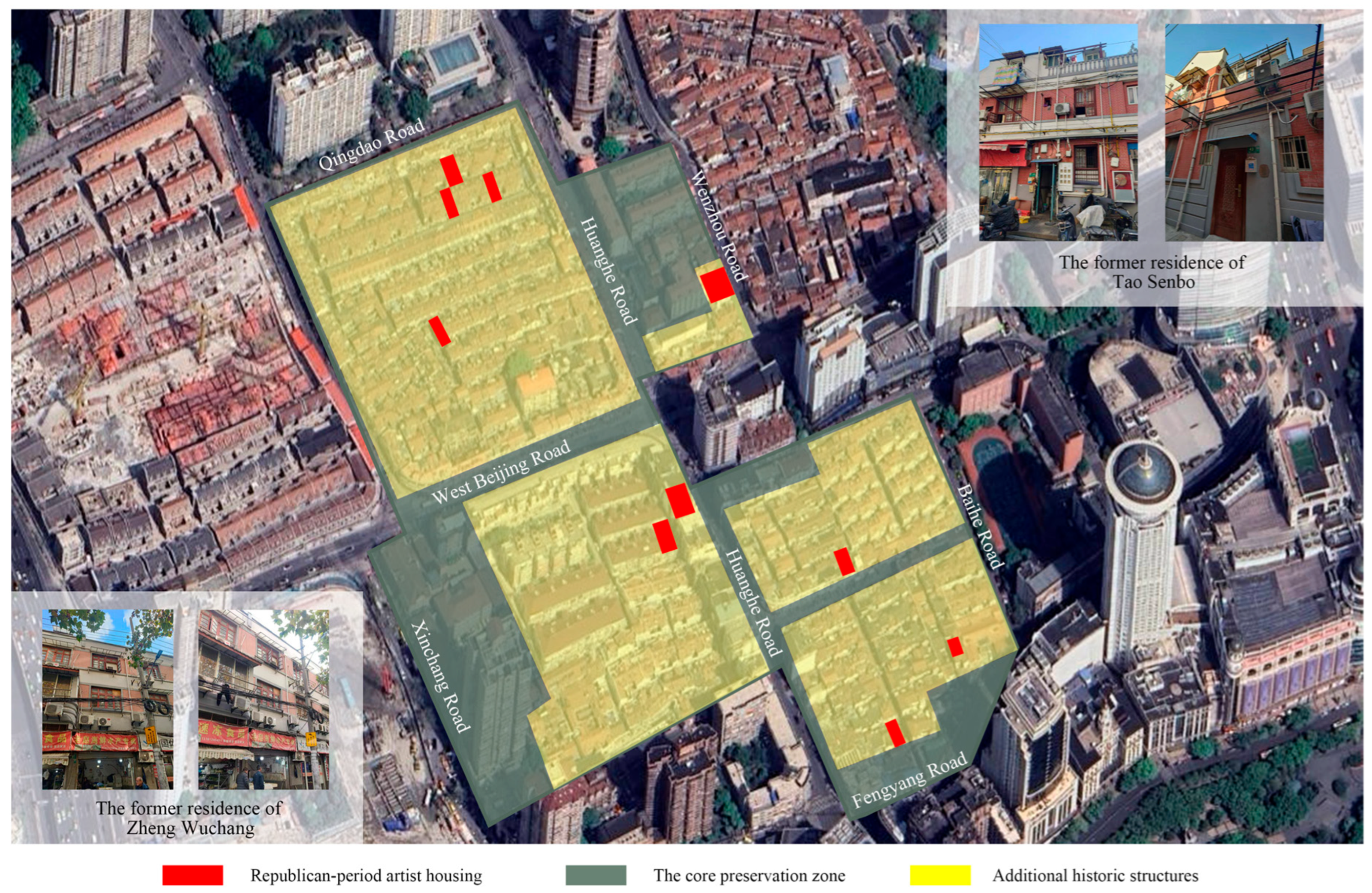

4.3. Preserving Environmental Sustainability

4.4. Negotiating Social Sustainability

4.5. Challenging Economic Sustainability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ward, P. Conservation and Development in Historic Towns and Cities; Oriel Press: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1968; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Doratli, N. Revitalizing Historic Urban Quarters: A Model for Determining the Most Relevant Strategic Approach. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2005, 13, 749–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, P.L.; Ferilli, G.; Blessi, G.T.; Nuccio, M. Culture as an Engine of Local Development Processes: System-Wide Cultural Districts I: Theory. Growth Chang. 2013, 44, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrede, J. What May Culture Contribute to Urban Sustainability? Critical Reflections on the Uses of Culture in Urban Development in Oslo and Beyond. J. Urban. 2016, 9, 408–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, N.; Hosagrahar, J.; Pascual, J. Why Must Culture Be at the Heart of Sustainable Urban Development? Agenda 21 for Culture. 2016. Available online: https://estudogeral.uc.pt/bitstream/10316/44016/1/Why%20must%20culture%20be%20at%20the%20heart%20of%20sustainable%20urban%20development.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Lopes, A.C.; Farinha, J.; Amado, M. Sustainability Through Art. Energy Procedia 2017, 119, 752–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. Achieving Sustainability Through Adaptive Reuse Strategies: Beijing 798 Arts District Demonstrates the Power of Cultural and Creative Industry. Available online: https://www.viurrspace.ca/server/api/core/bitstreams/70c349ac-8ad8-4992-8497-813e6e88c4a9/content (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Naheed, S.; Shooshtarian, S. The Role of Cultural Heritage in Promoting Urban Sustainability: A Brief Review. Land 2022, 11, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitkova, L.; Silaci, I. Potential of Culture for Sustainable Urban Development. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 603, 032072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeretti, L. City of Art as a High Culture Local System and Cultural Districtualization Processes: The Cluster of Art Restoration in Florence. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.; Foord, J. Cultural Mapping and Sustainable Communities: Planning for the Arts Revisited. Cult. Trends 2008, 17, 65–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, P.L.; Blessi, G.T.; Nuccio, M. Cultural Policies and Local Planning Strategies: What Is the Role of Culture in Local Sustainable Development? J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 2009, 39, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darchen, S. Regeneration and Networks in the Arts District (Los Angeles): Rethinking Governance Models in the Production of Urbanity. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 3615–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, K.; Jackson, S.; Martin, A.J. Concentrating Creativity: The Planning of Formal and Informal Arts Districts. City Cult. Soc. 2010, 1, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santagata, W. Cultural Districts, Property Rights and Sustainable Economic Growth. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2002, 26, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L. Making Sustainable Creative/Cultural Space in Shanghai and Singapore. Geogr. Rev. 2009, 99, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Lau, S.S.Y.; Shen, Z.; Lau, S.S.Y. Sustainability Issues in the Industrial Heritage Adaptive Reuse: Rethinking Culture-Led Urban Regeneration Through Chinese Case Studies. J. Housing Built Environ. 2018, 33, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiore, G.; Vellecco, I. Cultural Districts, Tourism and Sustainability. In Strategies for Tourism Industry—Micro and Macro Perspectives; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ketsuwan, P.; Sareewas, T.; Sirikhotchpun, S.; Sukkasem, T. Sustainability of Arts and Culture: A Comparative Case Study of Cultural Village, Chiang Kham District, Phayao Province, Thailand and Luang Prabang, World Heritage City. Laos. Turkish J. Comput. Math. Educ. 2021, 12, 3035–3042. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W.; Xu, Y. Sustainable Development and the Rehabilitation of a Historic Urban District–Social Sustainability in the Case of Tianzifang in Shanghai. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Generalized Anxiety Disorder. In Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy: Innovative Applications; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, B. Deconstructing the City of Culture: The Long-Term Cultural Legacies of Glasgow 1990. In Culture-Led Urban Regeneration; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 841–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Q. Creative Milieux: How Urban Design Nurtures Creative Clusters. J. Urban Des. 2015, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G.; Shirvani Dastgerdi, A.; Francini, C.; Liberatore, G. Sustainable Cultural Heritage Planning and Management of Overtourism in Art Cities: Lessons from Atlas World Heritage. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IJECESS International Journal of Environmental, Cultural, Economic and Social Sustainability. Available online: https://www.scimagojr.com/journalsearch.php?q=19900193223&tip=sid (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Stevenson, D. “Civic Gold” Rush: Cultural Planning and the Politics of the Third Way. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2004, 10, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S.; Paddison, R. Introduction: The Rise and Rise of Culture-Led Urban Regeneration. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, K. Urban Cultural Strategies and Urban Regeneration: A Case Study and Critique. Environ. Plan. A 1993, 25, 1773–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandy, D.; Fenn, J. Sustainability: Sustaining Cities and Community Cultural Development. Stud. Art Educ. 2012, 53, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L. Sustainable Cultural Spaces in the Global City: Cultural Clusters in Heritage Sites, Hong Kong and Singapore. In The New Blackwell Companion to the City; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 452–462. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, Y.; Jung, C.; Joo, H. Residents’ Perception of a Collaborative Approach with Artists in Culture-Led Urban Regeneration: A Case Study of the Changdong Art Village in Changwon City in Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarker, S. Tangential attachments: Towards a more nuanced understanding of the impacts of cultural urban regeneration on local identities. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 3421–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Yu, S.; Zhou, J. The Sustainable Development of Street Texture of Historic and Cultural Districts―A Case Study in Shichahai District, Beijing. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J. Cultural Quarters as Mechanisms for Urban Regeneration. Part 2: A Review of Four Cultural Quarters in the UK, Ireland, and Australia. Plann. Pract. Res. 2004, 19, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J. Working Memory and Comprehension in Children with Specific Language Impairment: What We Know So Far. J. Commun. Disord. 2003, 36, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodhouse, S. Cultural Quarters: Principles and Practice; Intellect Books: Bristol, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. Cities and Cultures; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Landry, C. The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J. Contextualizing Public Art Production in China: The Urban Sculpture Planning System in Shanghai. Geoforum 2017, 82, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. ‘Creative Industry Clusters’ and the ‘Entrepreneurial City’ of Shanghai. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 3561–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. The “Entrepreneurial State” in “Creative Industry Cluster” Development in Shanghai. J. Urban Aff. 2010, 32, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; He, J.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, S.P.; Lin, H.; Leung, Y.S. Mapping the Most Influential Art Districts in Shanghai (1912–1948) through Clustering Analysis. J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 2022, 52, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, S.P.; Fan, Z.; He, J.; Leung, Y.S. Spatial Proximity in Artists’ Social Networks: The Shanghai Art World, 1912–1948. Trans. Plan. Urban Res. 2025, 4, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, S.P.; Fan, Z.; Lin, H.; Leung, Y.S. Rediscovering Shanghai Modern: Chinese Cosmopolitanism and the Urban Art Scene, 1912–1948. Urban Hist. 2024, 51, 198–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; PY Zhang, S.; Fan, Z.; Lin, H.; Leung, Y.S.; Liu, Y. Modeling the Creative Milieu of Cosmopolitan Cities: Shanghai, 1912–1948. J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 2024, 54, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions | Criteria | Applicability | Dimension Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional and Governance Sustainability | Assessment of compatibility with existing cultural relics laws and alignment with elite-led heritage assessment frameworks in China. | Strongly supported—EBDA is fully compatible with existing cultural relics laws and expert-led heritage assessment practices, making it readily adoptable within China’s institutional framework. | EBDA demonstrates strong institutional and governance relevance, with clear evidence of compatibility, policy uptake, and community engagement. While some criteria face constraints—particularly around balancing cultural and livelihood priorities, and the persistence of “red culture” dominance—the framework overall has strong applicability to China’s governance context. |

| Potential for expanding state-sanctioned heritage narratives toward a more inclusive valuation framework in China. | Partially supported—EBDA has the potential to broaden state-sanctioned narratives, but current policies still prioritize ideological alignment with “red culture.” Influence is possible mainly through expert advocacy. | ||

| Recognition of experts, artists, and cultural practitioners as participants in dialog between top-down planning and grassroots cultural memory. | Supported—EBDA effectively engages experts, artists, and residents and is already functioning as a bridge between top-down governance and grassroots memory in community cultural activities. | ||

| Valuation of the mediating role of narratives between state objectives and local identity, contributing to institutional legitimacy and cultural governance. | Partially supported—EBDA can strengthen cultural governance and legitimacy, but risks arise when cultural projects divert resources from livelihood improvements, creating tension at the neighborhood level. | ||

| Integration of art-historical evidence into planning as a means of strengthening institutional resilience by linking symbolic capital with policy frameworks. | Supported—Integrating art-historical evidence into planning enhances resilience by linking symbolic capital to policy, with practical uptake already observable in Shanghai’s planning practices. | ||

| Cultural Sustainability | Minimum threshold (e.g., 25%) of land use in the core preservation area reflecting Republican-period artistic life. | Partially supported—Current physical constraints limit practice, though strong public support and future potential exist. | The most strongly supported and feasible dimension for EBDA. Evidence shows it not only documents heritage but also actively sustains cultural identity by embedding art-historical narratives into education, daily life, community pride, and creative reinterpretation. Applicability is particularly high for criteria tied to intangible heritage, education, visibility, and reinterpretation, while spatial constraints remain the primary limitation. |

| Inclusion of educational programming on the history and achievements of Republican-period Shanghai artists. | Highly supported—Strongly supported by officials, communities, and survey data; clear pathways for integration in schools and communities. | ||

| Valuation of everyday cultural practices, creative processes, and social environments of Republican-period artists. | Highly supported—Officials emphasize intangible heritage; supported by community observations and survey evidence. | ||

| Visibility of local cultural identity linked to Republican-period art history through commemorative and public cultural forms. | Highly supported—Strong government and community willingness; existing murals and plaques demonstrate feasibility. | ||

| Inclusion of local artists, historians, and residents in heritage-related planning, programming, and interpretation. | Supported—Institutional structures and practices already in place; EBDA can enhance coordination and engagement. | ||

| Contemporary reinterpretation of Republican-period artistic traditions within ongoing cultural activities. | Highly supported—EBDA strengthens community cultural facilities and enables reinterpretation via contemporary art. | ||

| Environmental Sustainability | Retention of traditional street and lane networks characteristic of Republican-period artists’ neighborhoods. | Supported—Strong community and official support; emotional and cultural significance recognized; practical challenges exist in balancing conservation with daily needs. | EBDA demonstrates strong environmental sustainability relevance. The approach effectively preserves spatial patterns, architectural integrity, and visual identity, while supporting pedestrian connectivity and integrating heritage into everyday urban life. |

| Conservation of original architectural styles and defining elements of Republican-period artists’ residences. | Supported—EBDA-aligned restoration efforts actively preserve Republican-era residences; tangible heritage fosters intergenerational engagement. | ||

| Preservation of overall spatial integrity and continuity of the district as a unified cultural landscape. | Supported—Spatial continuity maintained under EBDA guidance; high institutional and community commitment; clear evidence from maps and observations. | ||

| Maintenance of high spatial permeability, ensuring accessible pedestrian pathways to key cultural venues. | Supported—Improved circulation between residences and landmarks; internal movement enhanced, though access depends on location and current use. | ||

| Social Sustainability | Collaborative development frameworks involving art historians, artists, art organizations, and local residents. | Supported—Strong potential to foster engagement among art historians, cultural organizations, and residents; backed by community and official support. | EBDA demonstrates partial social sustainability relevance, as it strengthens public participation, collective memory, and community engagement. Applicability varies by criterion: collaboration, collective memory, and social networks are well supported, while capacity-building programs and affordable creative spaces face structural and spatial limitations. |

| Mechanisms for public participation enabling specialists and residents to influence planning and implementation. | Partially supported—Engagement exists but is limited by current governance structures; EBDA can strengthen meaningful participation over time. | ||

| Capacity-building programs in heritage restoration and cultural skills for local residents. | Limited applicability—Current institutions do not provide heritage training; implementation requires structural policy support. | ||

| Valuation of collective memory and sense of place associated with Republican-period artistic heritage. | Supported—Strongly endorsed by officials and communities; enhances local identity and belonging. | ||

| Provision of affordable creative workspaces for emerging artists, supporting inclusiveness and intergenerational cultural exchange. | Limited applicability—Short-term feasibility constrained by land use and community acceptance; long-term planning required. | ||

| Strengthening of social networks and community trust. | Supported—EBDA can expand informal gathering spaces and foster inclusive neighborhood ties; backed by observations and survey data. | ||

| Economic Sustainability | Support for a vibrant creative economy rooted in local cultural production. | Partially supported—EBDA can stimulate creative activity, but impact is limited by land-use constraints and residential predominance; long-term policy support needed. | EBDA demonstrates economic sustainability relevance. The relevance is strong, particularly in terms of leveraging heritage for cultural consumption and tourism. The framework can partially support local creative economies, employment, and affordable artist spaces, but these outcomes depend on structural and policy conditions. |

| Sustaining a diverse job market for artists and creative professionals linked to Republican-period legacies. | Partially supported—EBDA can facilitate employment opportunities in creative sectors, though effects are modest and contingent on broader urban planning measures. | ||

| Provision of affordable living and working spaces for economically marginalized artists. | Partially supported—By property ownership, rising rents, and active residential use; requires strategic interventions. | ||

| Leveraging Republican-period artistic heritage as cultural capital for tourism and cultural consumption. | Supported—Strong potential to enhance cultural tourism, attract resources, and generate foot traffic; supported by surveys and interviews. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Xie, M.; Ge, W. Toward a Disciplinary Knowledge–Led Approach for Sustainable Heritage-Based Art Districts in Shanghai. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8215. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188215

Zheng J, Liu Y, Li X, Xie M, Ge W. Toward a Disciplinary Knowledge–Led Approach for Sustainable Heritage-Based Art Districts in Shanghai. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8215. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188215

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Jane, Yue Liu, Xiaotian Li, Mingyang Xie, and Wenhao Ge. 2025. "Toward a Disciplinary Knowledge–Led Approach for Sustainable Heritage-Based Art Districts in Shanghai" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8215. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188215

APA StyleZheng, J., Liu, Y., Li, X., Xie, M., & Ge, W. (2025). Toward a Disciplinary Knowledge–Led Approach for Sustainable Heritage-Based Art Districts in Shanghai. Sustainability, 17(18), 8215. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188215