Regional Disparities and Determinants of Paediatric Healthcare Accessibility in Poland: A Multi-Level Assessment of Socio-Economic Drivers and Spatial Convergence (2010–2023)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Consideration and Previous Research

2.1. Theoretical Considerations

2.2. Previous Research on Regional Disparities in Healthcare Accessibility

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Model Specifications and Estimation Techniques

+ β3 × Disposable Incomeit + εit

4. Results

4.1. Normality Tests and Justification for Non-Parametric Methods

4.2. Local Rank-Based Correlations and Wilcoxon Tests

4.3. Panel Regression Results

4.4. Interpretation and Implications

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| FE | Fixed Effects |

| PSA Index | Paediatric Healthcare Accessibility Index |

| RE | Random Effects |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| UN | United Nations |

References

- WHO. Health in 2015: From MDGs, Millennium Development Goals to SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-92-4-156511-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach, J.P.; Stirbu, I.; Roskam, A.-J.R.; Schaap, M.M.; Menvielle, G.; Leinsalu, M.; Kunst, A.E. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health in 22 European Countries. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2468–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Health at a Glance: Europe 2022: State of Health in the EU Cycle; Health at a Glance: Europe; OECD: Paris, France, 2022; ISBN 978-92-64-46211-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rój, J. Inequality in the Distribution of Specialist. In Sustainable Finance in the Green Economy, Proceedings of the 3rd Finance and Sustainability Conference, Wrocław, Poland, 12–13 December 2019; Springer Nature: London, UK, 2022; p. 177. [Google Scholar]

- Zienkiewicz, T.; Klatka, M.; Zienkiewicz, E.; Klatka, J. Determinants and Disparities in Access to Paediatricians in Poland. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabiński, T.; Wydymus, S.; Zeliaś, A. Metody Taksonomii Numerycznej w Modelowaniu Zjawisk Społeczno-Gospodarczych; Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warszawa, Polska, 1989; ISBN 978-83-01-08596-4. [Google Scholar]

- Goryakin, Y.; Rocco, L.; Suhrcke, M. The Contribution of Urbanization to Non-Communicable Diseases: Evidence from 173 Countries from 1980 to 2008. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2017, 26, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Svedberg, P.; Olén, O.; Bruze, G.; Neovius, M. The Longitudinal Integrated Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies (LISA) and Its Use in Medical Research. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 34, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reibling, N.; Ariaans, M.; Wendt, C. Worlds of Healthcare: A Healthcare System Typology of OECD Countries. Health Policy 2019, 123, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houweling, T.A.J.; Grünberger, I. Intergenerational Transmission of Health Inequalities: Research Agenda for a Life Course Approach to Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2024, 78, 650–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabani, J.; Mazumdar, S.; Suhrcke, M. The Effect of Health Financing Systems on Health System Outcomes: A Cross-country Panel Analysis. Health Econ. 2023, 32, 574–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allin, S.; Masseria, C. Research Note: Unmet Need as an Indicator of Access to Health Care in Europe. Lond. Sch. Econ. Political Sci. Res. Note 2009, 15, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorslaer, E.; Wagstaff, A.; Van Der Burg, H.; Christiansen, T.; De Graeve, D.; Duchesne, I.; Gerdtham, U.-G.; Gerfin, M.; Geurts, J.; Gross, L.; et al. Equity in the Delivery of Health Care in Europe and the US. J. Health Econ. 2000, 19, 553–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanikolos, M.; Mladovsky, P.; Cylus, J.; Thomson, S.; Basu, S.; Stuckler, D.; Mackenbach, J.P.; McKee, M. Financial Crisis, Austerity, and Health in Europe. Lancet 2013, 381, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowada, C.; Sagan, A.; Kowalska-Bobko, I.; Badora-Musiał, K.; Bochenek, T.; Domagała, A.; Dubas-Jakóbczyk, K.; Kocot, E.; Mrożek-Gąsiorowska, M.; Sitko, S.; et al. Poland: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2019, 21, 1–234. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Socio-Economic and Ethnic Health Inequalities in COVID-19 Outcomes Across OECD Countries; OECD Health Working Papers; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD): Paris, France, 2023; p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Baltagi, B.H. Econometric Analysis of Panel Data; Springer Texts in Business and Economics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-53952-8. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom (1999). In The Globalization and Development Reader. Perspectives on Development and Global Change; Roberts, J.T., Hite, A.B., Chorev, N., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2014; pp. 525–548. ISBN 978-1-118-73510-7. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E.W. Seeking Spatial Justice; Globalization and Community; University of Minnesota Press: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-8166-6668-3. [Google Scholar]

- Vo, A.; Tao, Y.; Li, Y.; Albarrak, A. The Association Between Social Determinants of Health and Population Health Outcomes: Ecological Analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2023, 9, e44070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcena-Martín, E.; Melchor-Ferrer, E.; Pérez-Moreno, S. Spatial Convergence in the Quality of Public Services: Evidence from European Regions. Lett. Spat. Resour. Sci. 2025, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Health at a Glance: Europe 2024: State of Health in the EU Cycle; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024; p. 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Wang, X. Unveiling Spatial Disparities in Basic Medical and Health Services: Insights from China’s Provincial Analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, M.; Chaiyachati, K.H.; Fung, V.; Manson, S.M.; Mortensen, K. Eliminating Health Care Inequities through Strengthening Access to Care. Health Serv. Res. 2023, 58, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, C.C.; Nuzhath, T. An Exploration of Barriers to Access to Healthcare in Hancock County, Tennessee: A Qualitative Study. Health Expect. 2024, 27, e14074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, N. Discrimination and Health Inequities. Int. J. Health Serv. 2014, 44, 643–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Bauermeister, J.A.; Oyiborhoro, U.; Villarruel, A.M.; Bonett, S. The Relationship between Racial Discrimination in Healthcare, Loneliness, and Mental Health among Black Philadelphia Residents. Int. J. Equity Health 2025, 24, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fustolo-Gunnink, S.F.; De Boode, W.P.; Dekkers, O.M.; Greisen, G.; Lopriore, E.; Russo, F. If Things Were Simple, Word Would Have Gotten around. Can Complexity Science Help Us Improve Pediatric Research? Pediatr. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R.J.; Sala-i-Martin, X. Economic Growth, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-262-02553-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdański, M.; Janusz, M. Effective Cohesion Policy? Long-Term Economic and Social Convergence in Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gächter, M.; Theurl, E. Health Status Convergence at the Local Level: Empirical Evidence from Austria. Int. J. Equity Health 2011, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.T.; Higgins, M.J.; Levy, D. Sigma Convergence versus Beta Convergence: Evidence from U.S. County-Level Data. J. Money Credit. Bank. 2008, 40, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. E4As Guide for Advancing Health and Sustainable Development: Resources and Tools for Policy Development and Implementation; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021; p. 254. [Google Scholar]

- Kickbusch, I.; Gleicher, D. Governance for Health in the 21st Century; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013; ISBN 978-92-890-0274-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bambra, C. Work, Worklessness and the Political Economy of Health Inequalities. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2011, 65, 746–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, R.G.; Marmot, M.G.; Weltgesundheitsorganisation (Eds.) Social Determinants of Health: The Solid Facts, 2nd ed.; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2003; ISBN 978-92-890-1371-0. [Google Scholar]

- Galea, S.; Vlahov, D. URBAN HEALTH: Evidence, Challenges, and Directions. Annu. Rev. Public. Health 2005, 26, 341–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (Ed.) Poland: Country Health Profile 2023; State of Health in the EU; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023; ISBN 978-92-64-73548-4. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Horizon Europe. Work Programme 2023–2025; Health 2024; European Commission Horizon Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, S.; O’Reilly, D.; Ross, E.; Maguire, A.; O’Hagan, D. Suicide Risk Following Emergency Department Presentation with Self-Harm Varies by Hospital. IJPDS 2023, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Diderichsen, F.; Evans, T.; Shkolnikov, V.M.; Wirth, M. Measuring Disparities in Health: Methods and Indicators. In Challenging Inequities in Health; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 48–67. ISBN 978-0-19-513740-8. [Google Scholar]

- Levesque, J.-F.; Harris, M.F.; Russell, G. Patient-Centred Access to Health Care: Conceptualising Access at the Interface of Health Systems and Populations. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, O.; Katz, L. Regional Evolutions. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 1992, 23, 1–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezcurra, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Political Decentralization, Economic Growth and Regional Disparities in the OECD. Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulhol, H.; Sowa, A.; Golinowska, S.; Sicari, P. Improving the Health-Care System in Poland; OECD Economics Department Working Papers; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD): Paris, France, 2012; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Rój, J. Inequality in the Distribution of Healthcare Human Resources in Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, J.; Schwierz, C. Efficiency Estimates of Health Care Systems; European Economy Economic Papers; European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; ISBN 978-92-79-44820-1. [Google Scholar]

- Athey, S.; Imbens, G.W. The State of Applied Econometrics: Causality and Policy Evaluation. J. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 31, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macinko, J.; Starfield, B.; Shi, L. The Contribution of Primary Care Systems to Health Outcomes within Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Countries, 1970–1998. Health Serv. Res. 2003, 38, 831–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conover, W.J. Practical Nonparametric Statistics, 3rd ed.; Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics; Applied Probability and Statistics Section; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-471-16068-7. [Google Scholar]

- Titaley, C.R.; Dibley, M.J.; Roberts, C.L. Factors Associated with Underutilization of Antenatal Care Services in Indonesia: Results of Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey 2002/2003 and 2007. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R.; Davidson, P. Improving Access to Care in America: Individual and Contextual Indicators. In Changing the US Health Care System: Key Issues in Health Services Policy and Management; Kominski, E., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 3–31. ISBN 978-1-118-12891-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, G.; Nolan, A.; Lyons, S. An Investigation of the Effect of Accessibility to General Practitioner Services on Healthcare Utilisation among Older People. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 220, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Walsh, B.; Wren, M.-A.; Barron, S.; Morgenroth, E.; Eighan, J.; Lyons, S. Geographic Inequalities in Non-Acute Healthcare Supply: Evidence from Ireland. HRB Open Res. 2021, 4, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neutens, T.; Schwanen, T.; Witlox, F.; De Maeyer, P. Equity of Urban Service Delivery: A Comparison of Different Accessibility Measures. Environ. Plan. A 2010, 42, 1613–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D.; Miller, G. The Role of Public Health Improvements in Health Advances: The Twentieth-Century United States. Demography 2005, 42, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO (Ed.) Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture, 3rd ed.; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-92-2-131581-0. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, L.Y.; Settles, I.; McGillen, G.G.; Davis, T.M. Critical Contributions to Scholarship on Women and Work: Celebrating 50 Years of Progress and Looking Ahead to a New Decade. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 126, 103490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemieńska, R. Gender, Family, and Work: The Case of Poland in Cross-National Perspective. Int. J. Sociol. 2008, 38, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS Knowledge Database. Labour Market. Online Resource; 2024. Available online: https://dbw.stat.gov.pl/en/dashboard/28 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Cottre, A.; Lucchetti, R. Gretl User’s Guide, Gnu Regression, Econometrics and Time-Series Library; Free Software Foundation: Boston, MA, USA, 2025; p. 186. [Google Scholar]

- Gál, Z.; Lux, G. ET2050 Territorial Scenarios and Visions for Europe: Territorial Scenarios and Visions for Central and Eastern Europe; ESPON: Luxembourg, 2014; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Antonescu, D.; Florescu, I.C. The Dynamics of Regional Inequalities in Romania. Comparative Analysis between the Major Crises—Financial and Sanitary. Cent. Eur. J. Geogr. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 6, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patache, L.; Chiru, C.; Pârvu, I. Study on Romanian Regional Convergence Under the Impact of the Health Crisis. Rom. J. Reg. Sci. 2021, 15, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Stańczyk, R. Convergence of Health Status in the European Union: A Spatial Econometric Approach. Am. J. Hypertens. 2016, 3, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraliyska, M. The EU Cohesion Policy’s Impact on Regional Economic Development: The Case of Bulgaria. J. Econ. Soc. Stud. (JECOSS) 2018, 7, 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bayerlein, M. Regional Health Care in the EU: ESI Funds as a Means of Building the European Health Union; SWP Research Paper 1/2024; German Institute for International and Security Affairs: Berlin, Germany, 2024; p. 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjinikolov, D. Bulgaria in the EU Cohesion Process. Econ. Altern. 2017, 2, 213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Font, J.; Gil, J. Exploring the Pathways of Inequality in Health, Health Care Access and Financing in Decentralized Spain. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2009, 19, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, A.; Fraile, M.; Gonzalez, P. Regional Decentralisation of Health Policy in Spain: Social Capital Does Not Tell the Whole Story. West Eur. Politics 1998, 21, 180–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosik, P.; Mazur, M.; Komornicki, T.; Goliszek, S.; Stępniak, M.; Duma, P.; Jakubowski, A.; Pomianowski, W. National and Regional Potential Accessibility Convergence by Decay and Decades in Germany, France, Spain, Poland and Romania in the Years of 1960–2020. J. Transp. Geogr. 2025, 123, 104106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, A.; Kostarakos, I.; Mylonakis, C.; Varthalitis, P. The Heterogeneous Causal Effects of the EU’s Cohesion Fund. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.13223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crucitti, F.; Lazarou, N.-J.; Monfort, P.; Salotti, S. The Impact of the 2014–2020 European Structural Funds on Territorial Cohesion. Reg. Stud. 2024, 58, 1568–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Province | Spearman’s Rho | Wilcoxon (PSA Index vs. Employment Rate) p-Value | Wilcoxon (PSA Index vs. Urbanisation Rate) p-Value | Wilcoxon (PSA Index vs. Disposal Income p.c.) p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLN | 0.13 | 0.0011 | 0.0011 | 0.0011 |

| KPM | 0.28 | 0.0058 | 0.0049 | 0.0064 |

| LUB | 0.15 | 0.0278 | 0.0312 | 0.0215 |

| LBS | 0.1 | 0.0491 | 0.0574 | 0.0448 |

| LDZ | 0.31 | 0.0025 | 0.0031 | 0.0027 |

| MLP | 0.42 | 0.0007 | 0.0005 | 0.0008 |

| MAZ | 0.45 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 |

| OPO | 0.23 | 0.0114 | 0.0097 | 0.0106 |

| PDK | 0.12 | 0.0338 | 0.0396 | 0.0309 |

| PDL | 0.26 | 0.0072 | 0.0065 | 0.0083 |

| POM | 0.35 | 0.0019 | 0.0013 | 0.0022 |

| WMZ | 0.37 | 0.0009 | 0.0010 | 0.0011 |

| SKL | 0.18 | 0.0181 | 0.0203 | 0.0169 |

| SWK | 0.33 | 0.0023 | 0.0016 | 0.0028 |

| WKL | 0.39 | 0.0008 | 0.0006 | 0.0010 |

| ZPM | 0.39 | 0.0042 | 0.0037 | 0.0053 |

| Variable | FE | p-Value (FE) | RE | p-Value (RE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.26096 | 0.414 | 0.06457 | 0.630 |

| Employment rate | 0.00260 | 0.610 | 0.00549 | 0.004 |

| Urbanisation rate | −0.00357 | 0.005 | −0.00312 | 0.016 |

| Disposable income | 0.000061 | 0.000 | 0.00006 | 0.001 |

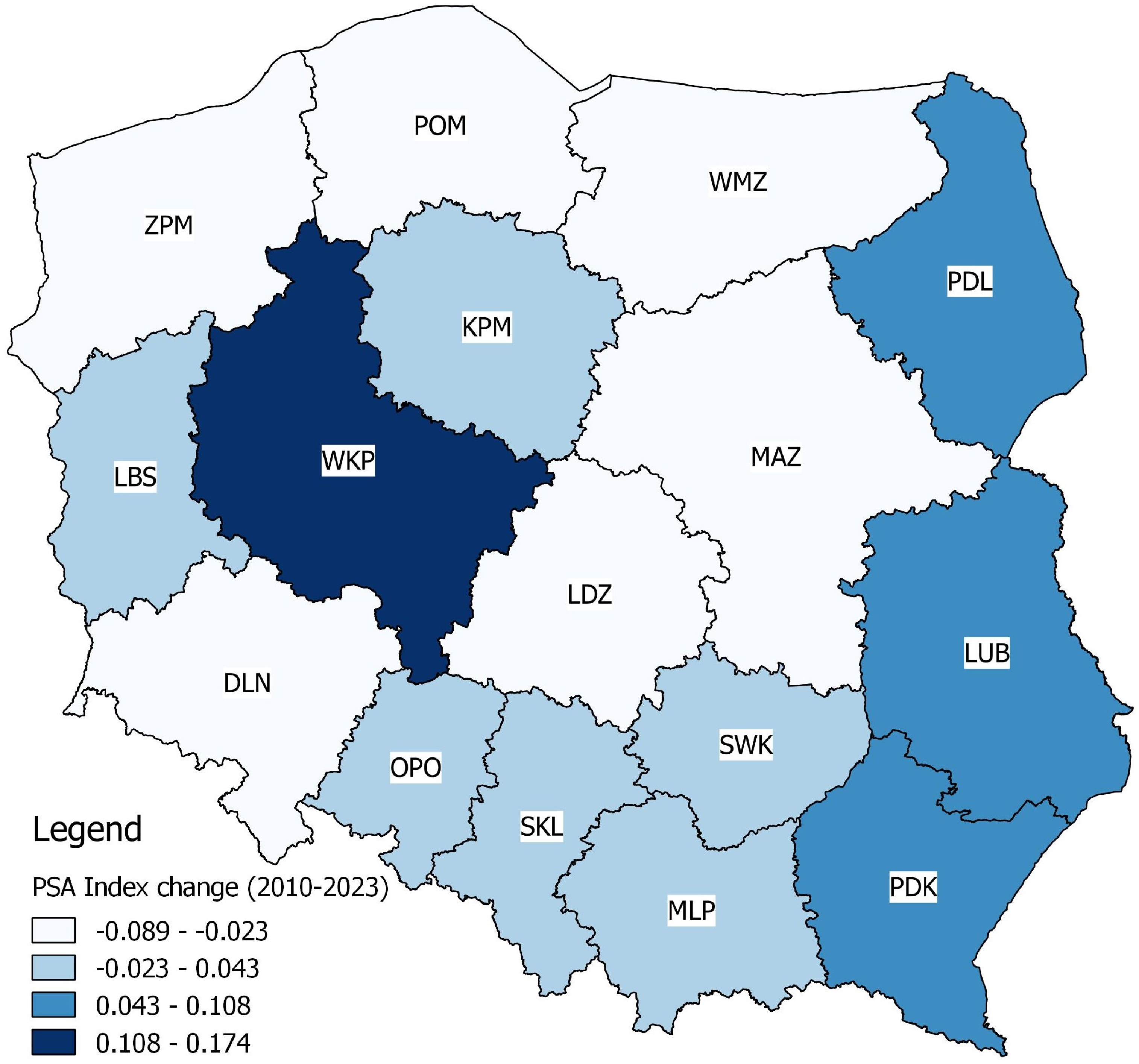

| Convergence Group | Provinces | Direction of Convergence | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong convergence | Mazowieckie, Małopolskie, Wielkopolskie, Śląskie | From below | High correlation and significant tests; PSA is steadily approaching the level of economic indicators. |

| Moderate convergence | Pomorskie, Warmińsko-Mazurskie, Zachodniopomorskie, Łódzkie | From below | Mean correlation and stable differences; further convergence is possible if trends continue. |

| Potential convergence | Podlaskie, Kujawsko-Pomorskie, Opolskie, Świętokrzyskie | Bottom or mixed | Moderate correlation values and test differences; the situation is diverse, requiring local diagnosis. |

| Lack of convergence | Lubuskie, Podkarpackie, Lubelskie, Dolnośląskie | From below or divergence | The low correlations and differences between PSA and socio-economic indicators are persistent and systematic. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zienkiewicz, T.; Zalewska, A.; Zienkiewicz, E. Regional Disparities and Determinants of Paediatric Healthcare Accessibility in Poland: A Multi-Level Assessment of Socio-Economic Drivers and Spatial Convergence (2010–2023). Sustainability 2025, 17, 8210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188210

Zienkiewicz T, Zalewska A, Zienkiewicz E. Regional Disparities and Determinants of Paediatric Healthcare Accessibility in Poland: A Multi-Level Assessment of Socio-Economic Drivers and Spatial Convergence (2010–2023). Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188210

Chicago/Turabian StyleZienkiewicz, Tadeusz, Aleksandra Zalewska, and Ewa Zienkiewicz. 2025. "Regional Disparities and Determinants of Paediatric Healthcare Accessibility in Poland: A Multi-Level Assessment of Socio-Economic Drivers and Spatial Convergence (2010–2023)" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188210

APA StyleZienkiewicz, T., Zalewska, A., & Zienkiewicz, E. (2025). Regional Disparities and Determinants of Paediatric Healthcare Accessibility in Poland: A Multi-Level Assessment of Socio-Economic Drivers and Spatial Convergence (2010–2023). Sustainability, 17(18), 8210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188210