Assessing Food Policies for Sustainability Transitions: A Scoping Review of Evaluation Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

- identifying processes and evaluation methods associated with food policies to develop a comprehensive understanding of the concept;

- exploring future research directions for studying and evaluating food policies.

2. Theoretical Framework

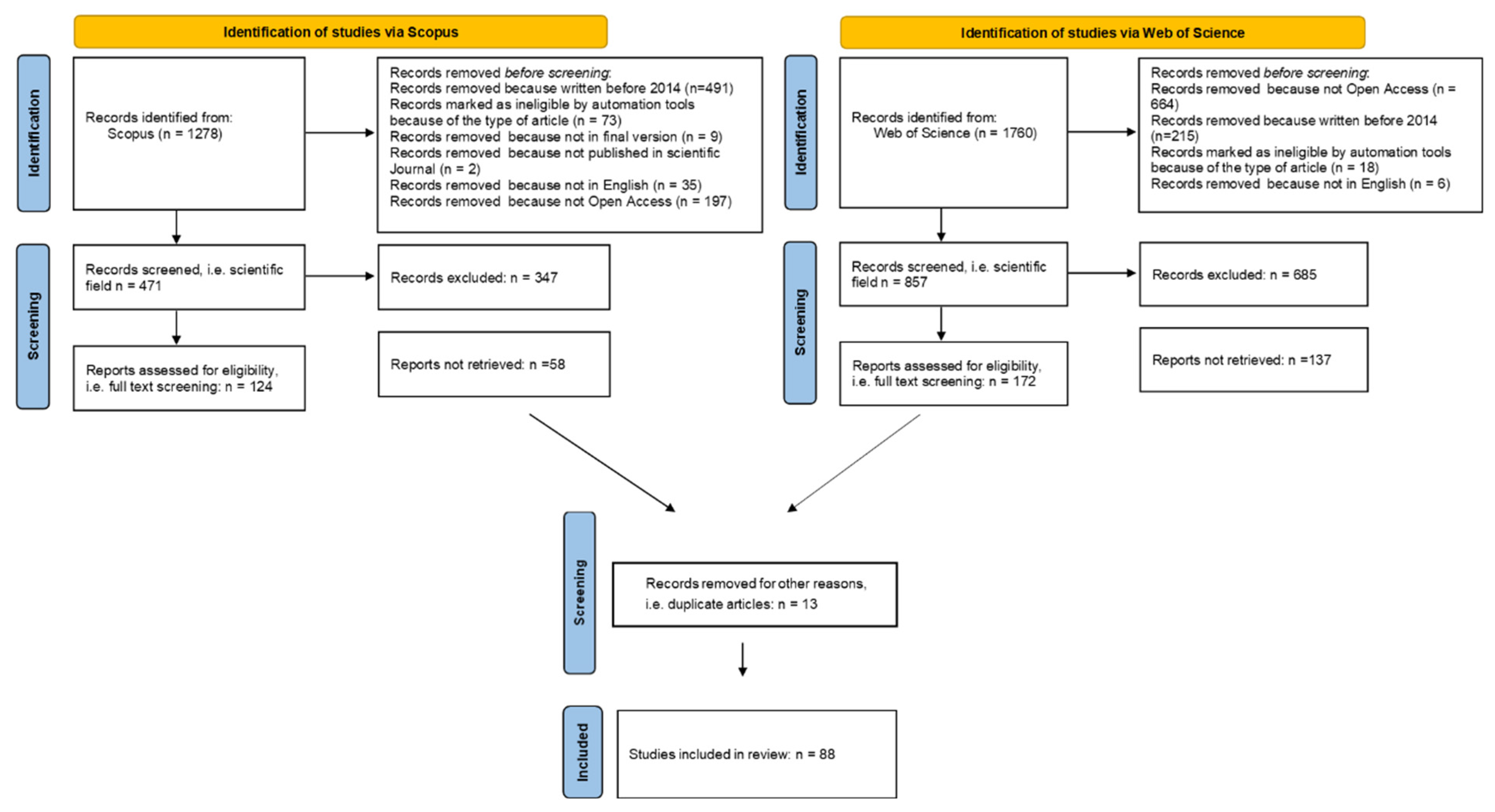

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

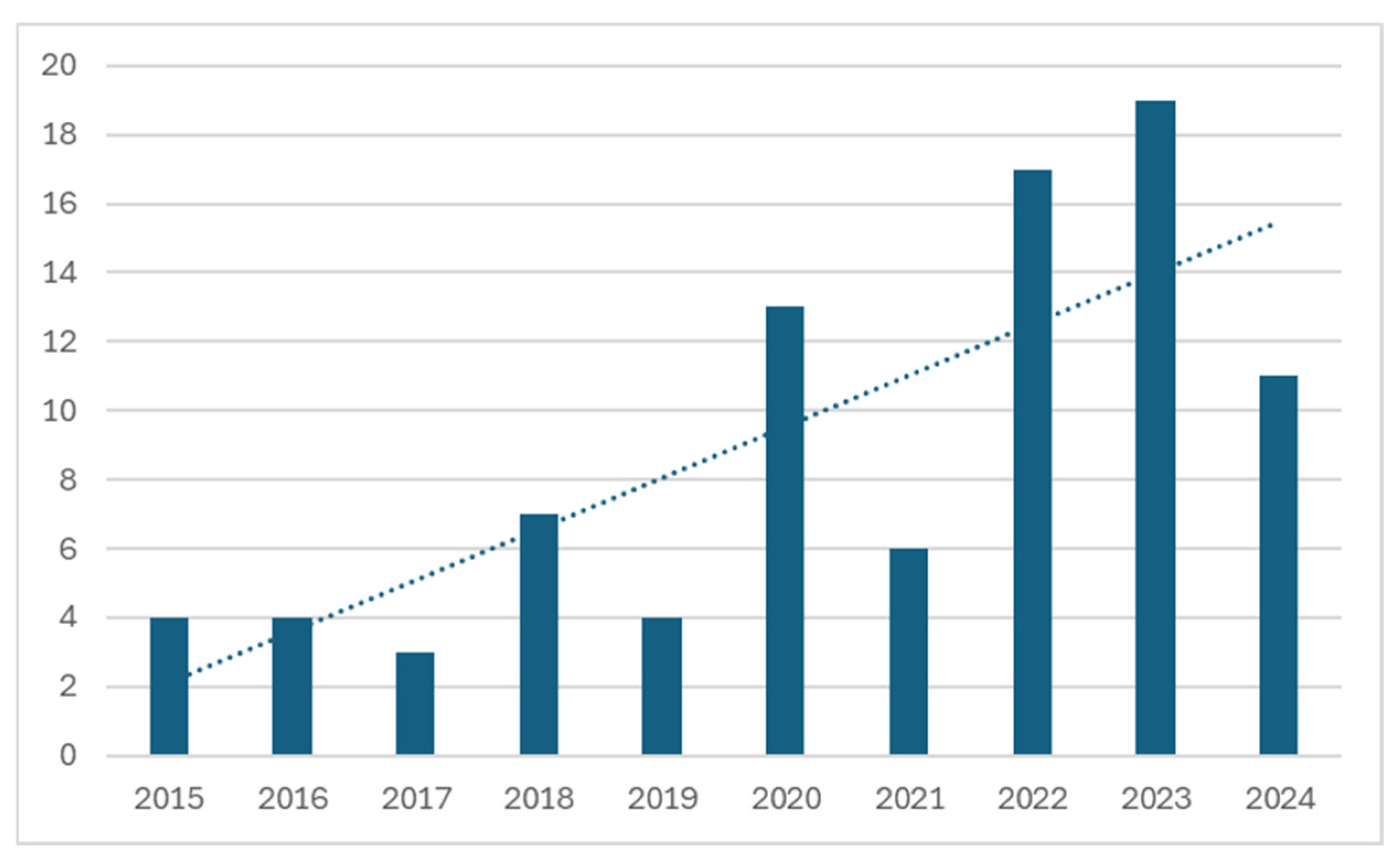

4.1. Descriptive Results

4.2. Substantive Results

4.2.1. Substantive Results: The Main Goals

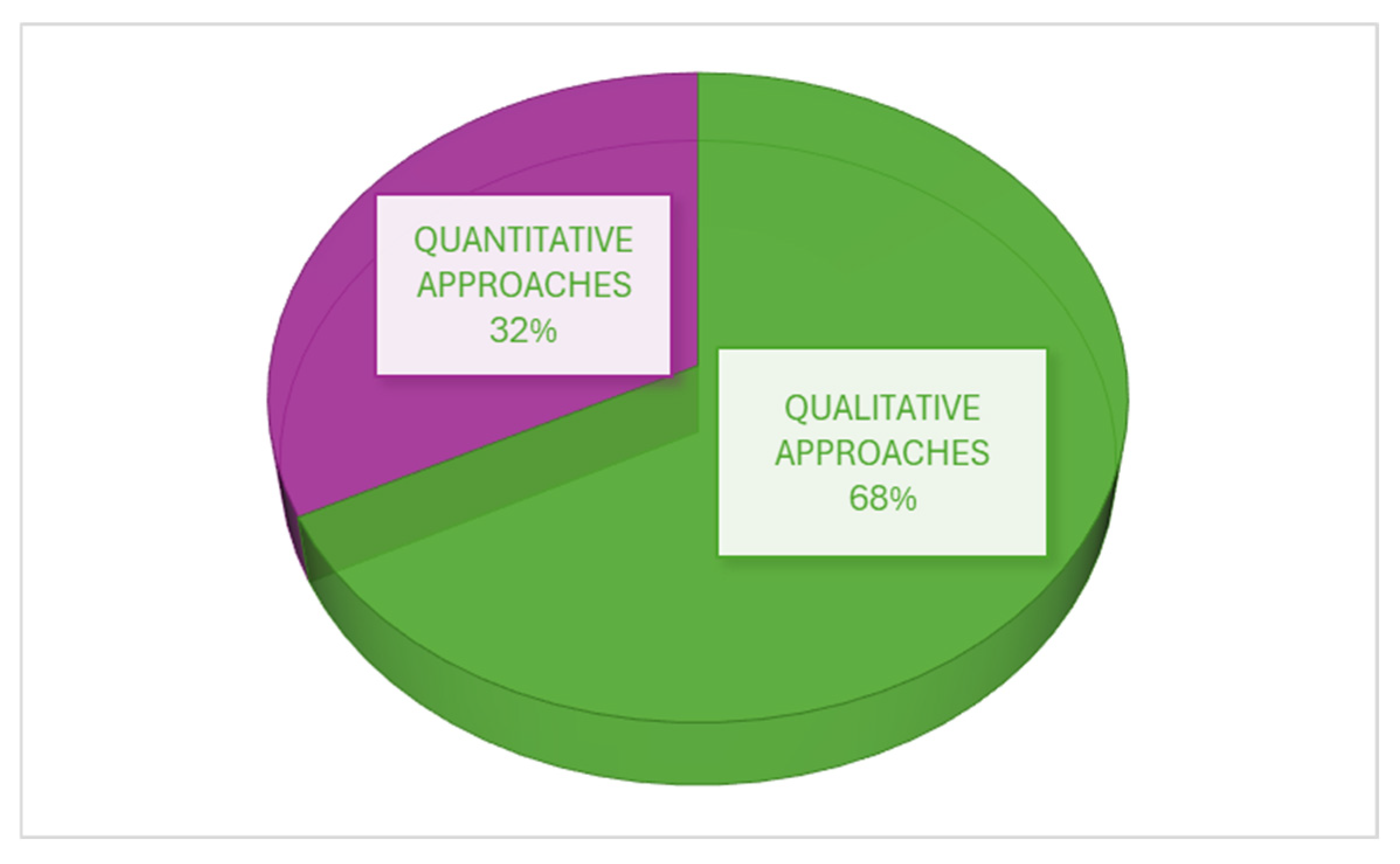

4.2.2. Substantive Results: The Main Methodology

4.2.3. Literature-Based Indicators

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Authors | Methodology | Geographical Contexts | Goals | Findings | Key Future Research Avenues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [40] | Netnographic approach | N/A | Investigating how food literacy is co-constructed on social media and identifying potential sources of bias leading to knowledge distortion | Food literacy constructed by consumers online is not always qualitative due to potential bias in contributions | Test results quantitatively to assess the importance and impact of different distortion biases; explore co-construction practices in other domains |

| [48] | Desk-based review of literature and documents | United Kingdom | Providing a snapshot of Secondary School Food Policy (SSFP) across devolved nations | Need for a coherent, whole-school approach to food supported by long-term resources and child engagement; importance of reviewing food curriculum, linking to school meals, and enhancing monitoring/reporting of standards | Difficulty comparing policies due to variations in education structures |

| [64] | Dataset analysis | United Kingdom | Describing existing UK food expenditure and diet datasets | No dataset suitable for reliable monitoring or prediction of sustainable diet transitions | Develop a coherent single instrument combining individual motivations, behaviors, and food consumption over time |

| [5] | Content analysis | The Netherlands | Assessing the extent to which food has been integrated across municipal policies | Various food challenges are integrated across municipal policies | Extend analysis from outputs to outcomes to assess societal effects |

| [51] | Focus group analysis (In Vivo coding; Structural coding) | California | Understand current produce recovery system and determine major challenges/opportunities | Key obstacles: long-term funding, regulatory tensions, need for more coordination along emergency food supply chain; critique of organizational categorization | Broaden research to represent wider food recovery movement; explore in-depth processes across more diverse organizations |

| [53] | Socioecological Integrated Analysis; multi-criteria indicator evaluation | Barcelona | Identify strategic factors for sustainable land-use planning to strengthen ecosystem services from agricultural systems | Industrial agriculture model has low energy efficiency, high carbon footprint; integration of farming, forestry, and livestock could improve sustainability | Develop multidimensional approaches for planning agroecosystems as metropolitan green infrastructures |

| [45] | Policy framework analysis; case studies | Seven European countries and New Zealand | Assess public policies impacting diet, physical activity, sedentary behavior | Produced Food Environment Policy Index (Food-EPI) and prototype PA-EPI | Use PEN framework for further comparative policy evaluation |

| [65] | Statistical adjustment method; literature synthesis | N/A | Assess how agroecology can be scaled up for sustainable, resilient agri-food systems | Lack of integrated research between agroecology and food systems | Develop overarching analytical framework linking agroecology, sustainability dimensions, and SDGs, with operationalization strategies |

| [46] | Conceptual framework design | Sweden | Develop national indicator framework for food system sustainability transition | Introduced “Food System Sustainability House” | Adapt framework for decision-making by individual actors |

| [66] | Regional IO framework (IMPLAN) and analysis-by-parts | USA | Evaluate economic impacts of food hubs on regional economies and participating farms | Developed a replicable empirical framework | Collect more farm-level data |

| [56] | Literature review, interviews, ANOVA analysis | Poland | Assess use of higher VAT tax rate on junk food | Higher VAT can promote sustainable consumption if paired with protective measures | Need better quantification along food supply chain |

| [67] | Secondary data analysis, interviews | North Carolina | Identify conditions affecting local food market development | Success depends more on institutional than local conditions | Research on how agencies can facilitate necessary infrastructure and networks |

| [43] | Healthy Food Environment Policy Index | Kenya | Assess extent of government action on healthy food environments | Most actions still in development phase | Study implementation processes |

| [68] | Surveys and interviews | India | Test link between food security programs and well-being | Qualitative evidence links food security to reduced hunger and improved well-being | Explore causal pathways |

| [55] | Preliminary analysis of catering service structure; carbon footprint analysis | Italy | Quantify climate change reduction potential of three green public procurement (GPP) policies in school catering services | 61–70% of GHGs emitted in production, 6–11% in provisioning, 24–28% in urban distribution. Policies targeting production practices have the highest potential; transport-related policies can have controversial effects | Couple carbon footprint analysis with other indicators (ecological, water footprint, full LCA) to evaluate overall environmental sustainability |

| [54] | Spatially explicit material flow analysis; life cycle assessment | Spain | Assess potential benefits and trade-offs of nutrient circularity using municipal solid waste (OMSW) compost in urban agriculture | Compost from 50% of selectively collected OMSW can substitute 8% of NPK demand; increasing to 21% with improved collection and compost infrastructure. Environmental benefits substantial, with up to 95–1.049% impact reduction | Explore broader nutrient circularity scenarios; improve infrastructure to maximize substitution and environmental gains |

| [69] | Quantitative Story-Telling (QST) with socio-institutional analysis | Canary Islands | Apply QST to study non-conventional water sources (AWR) for water and agricultural governance | Mainstream support for AWR reflects wider meta-narratives and socio-technical imaginaries | Address underrepresentation of local knowledge (farmers, civil society, women); improve continuity and participation in engagement processes; manage diversity and power asymmetries |

| [70] | Literature review; conceptual analysis of urban governance and collective consumption | United States | Explore how experimental governance around food consumption can foster transformative urban sustainability | Catalytic points of transformation at urban level can support broader sustainability transitions; transformative policy should increase governance capacity, engage stakeholders, and foster new alliances | Examine practical mechanisms for long-term transformative governance; study multi-stakeholder engagement strategies in urban food systems |

| [71] | Pre-interview survey; semi-structured interviews; thematic analysis using NVivo | Florida, USA | Characterize commercial urban farms and identify barriers, opportunities, and informational needs | CUA operations face typical small farm barriers plus local regulatory challenges; urban location is a key advantage; operators see potential for future growth | Expand research with larger sample sizes for generalizability; study policy interventions to reduce regulatory barriers |

| [72] | Literature review; multi-phased, practice-oriented, participatory backcasting | Thailand | Examine operationalization of practice-oriented futures policy development in urban food policy | Interventions were both conventional and practice-oriented. Participants’ agency perception and practice memory influenced generation of practice-oriented interventions. Narrative and drama helped illustrate future scenarios. Government seen as key driver; siloed governance is an obstacle | Future research could focus on foresight approaches within food policy councils to better leverage social practice complexity; account for author biases in scenario creation |

| [34] | Online self-administered and validated questionnaire | Saudi Arabia | Measure prevalence of healthy food consumption and effect of Saudi food policies | Most Saudis do not comply with dietary guidelines, are physically inactive, and use apps/social media that influence food choices. Calorie label awareness is increasing, but policy effects on weight take time | Address multiple variables in future studies; improve accuracy given recall and social desirability biases in self-reported tools |

| [35] | Advocacy coalition framework; qualitative semi-structured survey | Will County, IL, USA | Examine stakeholder perspectives to design food policies and community-based local food system | Stakeholders exhibited overlapping and divergent viewpoints (Pragmatic, Environmental/Food Justice, Visionary). Coalition-building and collaboration can empower communities, promote food justice, and support local food system identity | Further research could explore mechanisms to strengthen coalition-building and collaboration for local food system transformation |

| [73] | Scoping review | – | Create open access database of food system indicators for local food system assessment | Extracted 384 indicators | Expand search to identify additional indicators; assess practical use of database in food system evaluations |

| [74] | Sensory evaluation and hedonic testing | 7 countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America | Understand consumers’ acceptance of foods made with biofortified staple crops | Crops with visible nutrition traits generally accepted even without nutritional information; crops with invisible traits had mixed acceptance | Further research on long-term exposure, branding, competing products, promotion, and drivers of acceptance of invisible vs. visible traits; methodological work on loss aversion in experimental design |

| [75] | Living lab approach within Transdisciplinary Action Research | Trento, Italy | Discuss preliminary results of Nutrire Trento to analyze potentialities and critical aspects | Impasse likely due to power tensions among “extended peer communities” with different values, priorities, interests, and capacities. Tensions between participatory table and institutional environment; local executive power ignored municipal council decisions | Explore ways to resolve power tensions and improve institutional capacity to implement and sustain dialogue within living labs |

| [39] | Nutritional quality analysis (NRD9.3, health gain score) + life cycle assessment (carbon and water footprints) | EU and USA | Compare dietary guidelines across countries | High adherence generally benefits both nutritional and environmental indicators. Italian case best environmentally; Spanish MD best nutritionally | Refine carbon footprint data for diverse food items; incorporate more detailed geographical and food-specific variability to improve diet-environment assessments |

| [42] | Input–output model (IMPLAN SAM) | USA | Assess economic impact of public incentives for farm-to-school food purchases | Net positive value-added impacts; for every USD 1 lost in GDP to support program, USD 1.06 expected added GDP | Expand analysis to multiple school districts and years; account for broader market and demographic conditions; explore alternative metrics and empirical approaches |

| [38] | Systematic map/literature review | N/A | Examine evidence on effects of public policy interventions | Evidence dominated by non-intrusive instruments (labels, info campaigns, menu design); need research beyond lab settings; collaboration with public/private stakeholders essential | Conduct studies outside Europe/North America; scale up impact evaluations; strengthen multidisciplinary research and real-world policy implementation studies |

| [8] | Multi-actor approach; literature review; semi-structured interviews, focus groups, online survey | Austria | Contribute to research/policy on sustainable diets by understanding how different actors frame, negotiate, enact SD objectives | Identified synergies, tensions, trade-offs affecting policy implementation; context-dependent drivers (e.g., retailer density), public procurement, out-of-home consumption, community-supported agriculture | Conduct micro-level participatory analyses with citizens, especially vulnerable groups; strengthen multi-actor participatory methodologies; link macro- and micro-level analyses for policy insights |

| [76] | Stylized model of seasonal frictions + cost–benefit analysis | Indonesia | Test whether seasonal storage and credit programs improve well-being by raising consumption and health or reducing seasonal fluctuations | Storage program increased staple retention and non-food consumption but had no effect on health; credit program increased reported income; programs cost-effective for adapting to seasonality | Examine scaled-up consumption impacts and unpack program operation channels; improve food intake and staple inventory measurement |

| [77] | Five-day audit of donated food using standardized assessment | Australia | Assess safety and quality of food donations at an Australian food bank | 96% of 84,996 kg donations satisfactory; 4% unsafe/potentially unsafe/unsuitable, mostly from supermarkets | Assess nutritional quality and suitability for meals; better capture hazardous food volumes; inform food bank policy for increasing demand |

| [78] | Qualitative mixed methods: scenario chapter analysis, workshop notes, expert survey | Asia, America, Africa, Europe | Evaluate usefulness of scenario archetypes in science-policy processes (IPBES assessments) | Scenario archetypes useful for synthesizing diverse information and enhancing policy relevance; bridge science-policy gap | Combine with collaborative future assessment design; guide interventions for equitable and sustainable futures; overcome expert/time constraints |

| [79] | Qualitative content analysis + descriptive statistics | Brazil | Explore family farmers’ perceptions of public policy impacts on production, markets, food security, and land access | Crop diversification and agroecology increased; credit limited; public procurement stabilized income but increased dependency; food security improved but land access problematic | Develop policies enhancing on-farm autonomy, land access security, and reduce dependence on institutional markets |

| [80] | Focus groups + semi-structured interviews with farmers, market managers, key informants | USA (Oregon) | Evaluate Oregon’s Farm Direct Marketing Law (FDML): use, benefits, barriers, and food safety | FDML clarified regulatory ambiguity and enabled cottage food opportunities; initial uptake limited, benefits expected to scale over time | Expand quantitative assessment for generalizability; monitor scaling of benefits across farmers and communities |

| [81] | MFSS model integrating food demand and supply based on regional production and dietary patterns | Europe | Assess spatial extent of foodsheds and theoretical self-sufficiency of metropolitan communities | Substantial variation in foodshed extent and self-sufficiency between regions depending on population density, geography, and urban proximity; MFSS model useful for food planning and assessing spatial consequences of food system changes | Explore practical applications of the MFSS model in planning; examine effects of potential changes in regional food systems on self-sufficiency |

| [82] | Photovoice method: youth document and discuss food system issues with cameras | Study how youth engage with and transform school food systems | Youth learned about food and public policy through documenting and reflecting on their school food environments | Expand to larger or comparative studies; explore long-term impacts on youth civic engagement and policy influence | |

| [49] | Systematic literature review; bibliometric and thematic analysis | N/A | Review methodologies and trends in Food Policy Coherence and Integration (PCI) research | Europe dominates the literature; most studied policy domains: nutrition and trade, agriculture and environment; quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods used | Explore PCI at urban or regional level; overcome stakeholder complexity; expand language and database coverage beyond English, Scopus, and Web of Science |

| [83] | Literature review + decision tree analysis | Canada | Evaluate Canada’s National Food Policy regarding food security | FPC aims to improve food security; effectiveness depends on income/price/housing interventions; variation in household food insecurity important; policies promoting local food may not reduce food insecurity | Compare food consumption bundles of food-secure vs. food-insecure households; explore different definitions and measures of food security under policy mandates |

| [84] | Action research and citizen science with direct observation and participation | Portugal | Evaluate FoodLink network and its role in urban food transition | FoodLink contributes to literature, documents networking process and action plan; existence of network alone insufficient for sustainable food supply; governance and co-learning critical; academia’s strategic role positive | Further assess qualitative and participatory methods; monitor implementation of action roadmap; evaluate long-term governance and food planning impacts |

| [85] | Theory and expert-guided typology; Boolean logic solution formulas to classify countries by policy relevance | N/A | Assess how blue foods can contribute to food system ambitions across nations | Blue foods can provide critical nutrients, healthy alternatives to terrestrial meat, reduce dietary environmental footprints, and support nutrition, economies, and livelihoods under climate change. African and South American nations benefit for nutrient deficiencies; Global North nations for health and environmental gains | Analytical framework identifies countries at high future climate risk; emphasizes need for climate adaptation in blue food systems |

| [86] | Multilevel perspective on sociotechnical transitions; multiple streams framework; content analysis | USA (New York) | Track and assess food system changes and policy responses during COVID-19 | Policies emphasized support for food businesses and workers, and expanded food access. Most measures were incremental and temporary, but the crisis enabled novel policy approaches | Long-term trajectories of food access/nutrition policy; institutionalizing food as a human right; longitudinal studies; data from tribal governments and organizations |

| [87] | Literature review, internal UC ANR survey, community interviews | USA (California) | Support urban farming by assessing needs of urban farmers and extension personnel | Preliminary findings highlight engagement of UC ANR staff with urban agriculture and the tools needed by urban farmers | No open access to full study; further studies could expand on findings and implementation of support tools |

| [59] | Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA), fuzzy-set approach | Europe (Milano Urban Food Policy Pact cities) | Determine governance combinations that drive highly innovative urban food policies | Absence of practices like mapping initiatives, integrating government, and monitoring prevents high innovation; governance practices crucial | Generalization to other cities requires testing; further research on unexplained high innovativeness needed |

| [30] | Literature review; empirical model linking green environment, social protection, and food security | Africa | Evaluate interaction between green environment, social protection, and food security | Improvement in environmental management (+0.81%) and social protection (+1.17%) enhances food security; interaction effect +0.96% | Focused only on food availability dimension; future studies should include access, stability, and utilization dimensions |

| [88] | Scoping review | Manitoba, Canada | Assess impacts of COVID-19 on food systems and resilience; examine changes in food access and policy responses | Findings organized into: (1) food security policy, funding, programming; (2) food security for individuals, households, vulnerable groups; (3) food systems | Explore community experiences; develop local food systems |

| [36] | Interviews, focus groups, retrospective pre/post survey | NC State EMFV program, USA | Evaluate pilot program training FCS educators and volunteers in food systems and local food | Need for training in food systems; interest in cross-program collaboration; handling controversial food system issues; intersection with food insecurity | Building cross-program collaborations and addressing controversial topics while integrating evidence-based and community values |

| [89] | Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM), Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) | Valencia, Spain | Identify sustainable urban dietary patterns for recommendation or policy | Vegan diet prioritized environmentally; Mediterranean diet ranked best overall considering health, socio-economic, cultural, affordability, social impact, and local production | Compare chosen patterns with current consumption |

| [90] | Interviews | Pisa, Italy | Examine relationship between farm market orientation and agricultural intensity in periurban systems | Demonstrated relationship between market orientation and agricultural intensity in periurban farms | Develop single agricultural intensity index |

| [91] | Policy review | Switzerland | Review 20 years of Swiss agricultural policy reforms and lessons for other countries | Key implications: (i) policy goals met at high cost, efficiency needed; (ii) need coherence and coordination for “food system policy”; (iii) cross-compliance measures are effective; (iv) spatial targeting and results-based payments improve outcomes | future research should explore transferability of lessons, causal effects of policy mixes, and integrated policy frameworks to balance food and ecosystem services |

| [92] | Nutritional analysis, prospective cohort study | Brazil | Compare changes in BMI, waist circumference, and food consumption over 4 years between manufacturing workers in companies participating vs. not participating in the Workers’ Food Program (WFP) | Access to WFP associated with increased weight and waist circumference; in some workers, weight gain negatively affected nutritional status | Conduct longitudinal studies in other states; analyze qualitative and quantitative aspects of WFP menus to assess nutritional adequacy |

| [37] | Secondary qualitative content analysis | United States | Evaluate effectiveness of Food Policy Councils (FPCs) in urban areas regarding leadership, governance, stakeholder engagement, and food justice | FPCs collaborating with both city and county had higher effectiveness and better integration of diversity and inclusion compared to FPCs representing only city or county | Further assess urban FPC effectiveness relative to regional goals and higher-level funding, including USDA support |

| [55] | Life cycle assessment (LCA) | Italy (Turin) | Rank sustainable public procurement (GPP) options for climate-friendly catering services based on environmental impact | Some GPP policies highly effective in specific modules, but overall reduction in carbon footprint limited; expert judgments highlight practical implementation challenges | Expand evaluation to additional impact categories |

| [93] | Participatory serious games | Japan (Kyoto) | Design games to impact anticipatory climate governance and assess implications for developers and stakeholders | Games piloted successfully; strong evaluation allows scaling; games can serve educational and governance purposes | Explore full institutionalization of anticipatory governance games |

| [29] | Case study questionnaire | Zimbabwe | Assess nutritional vulnerability of pregnant women benefiting from the 2010 Vulnerable Group Feeding Programme | Food baskets and supplements insufficient to meet nutritional needs; women remained vulnerable despite program participation | Government should provide additional provisions for vulnerable pregnant women; monitor progress toward Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) |

| [94] | Comparative case study, pragmatic logic model evaluation | Upper-Rhine region (Fribourg, Basel, Mulhouse, Strasbourg) | Analyze success of Food Policy Councils (FPCs) in contributing to food system sustainability, food democracy, and good governance | Mixed results: FPCs mostly lay groundwork for later efforts and face challenges adhering to democratic and good governance principles | Address data gaps, expand sample size to validate causal links between democratic/governance practices and outcomes, adopt longitudinal perspective, apply action research approaches, improve methodological frameworks |

| [95] | Case study, participant–observer interviews, vulnerability framework, Fault Tree Analysis | Baltimore, U.S. | Increase resilience of Baltimore’s urban food system | Identified success factors and challenges for food system resilience | Apply framework in other urban contexts, combine participant observation with longitudinal monitoring |

| [32] | Sustainable Food System Policy Index, regression analysis | U.S. | Assess inclusion of social, environmental, and economic sustainability dimensions in local food system plans and relationship with community capitals | Wide range of topics included, but some issues like decision-making participation, financial infrastructure, and natural resource management are underrepresented | Explore tertiary scoring for multidimensional integration, inventory strategies by mechanism of action, expand index-based assessment |

| [50] | Policy coherence scoring (−3 to +3) comparing water, energy, food policies | Kenya | Assess interconnections and opportunities for coherence among WEF policies in Tana River Basin | Water policy objectives showed most synergies; policy coherence can improve resource management | Apply approach to other regions and at later policy stages, integrate longitudinal assessment |

| [96] | Lab and field experiments | U.S. (students), Peru (farmers) | Test producer behavior under output price risk | Mixed results: Batra and Ullah model partially supported; Sandmo’s predictions not supported; non-linear effects under relaxed assumptions | Test alternative behavioral models (e.g., prospect theory), explore context-specific findings, address experimental simplifications |

| [97] | Statistical adjustment method combining HCES and 24HR dietary surveys | Bangladesh | Reduce gender bias in household food consumption data for better-targeted fortification interventions | HCES overestimates household-level intake, underestimates women’s share; new method reduces bias using small 24HR sample | Validate method in other countries and contexts, collect more disaggregated and detailed intra-household consumption data |

| [98] | Systematic review | Global | Evaluate effectiveness and policy implications of health taxes on high-fat, sugar, salt foods | Health taxes reduce consumption, raise revenue; effects context-dependent, substitutes and low visibility limit impact | Study long-term impacts, low-income settings, optimize tax design, assess unintended effects |

| [41] | Literature review | Urban settings (various) | Identify chemical and biological risks in urban agriculture; develop food safety assessment framework | Urban agriculture poses food safety risks; framework helps assess and manage risks | Apply framework across urban settings, gather empirical data, adapt to regulatory contexts |

| [52] | Qualitative content analysis | Europe | Examine social justice integration in urban food strategies (redistribution, recognition, representation) | Limited integration of social justice; focus on sustainability over equity | Research inclusive governance approaches, assess outcomes for marginalized communities, develop specific indicators |

| [99] | Experimental design, ex-post treatment vs. control | Bangladesh | Develop practical framework for resilience impact assessment under data constraints | Framework allows rigorous assessment even in data-scarce settings | Test in diverse geographical and programmatic contexts, improve generalizability |

| [57] | Sustainability Impact Assessment (SIA) framework | Berlin (Germany), London (UK), Ljubljana (Slovenia), Nairobi (Kenya) | Rapid assessment of short food supply chains (SFSCs) sustainability | SFSCs show social sustainability benefits; economic/environmental trade-offs exist; tool facilitates stakeholder discussions | Apply in additional contexts and food chain types, collect longitudinal data, improve data collection approaches |

| [61] | Water footprint analysis | N/A | Provide a framework for policymakers to address water stress and optimize water use in food production | Weak correlation between water use and water stress; need for better allocation strategies; support for sustainable intensification | Improve benchmarks for water productivity; study dietary shifts; advance understanding of green water scarcity and granular water productivity |

| [100] | Ecological footprint accounting | Portugal | Identify contribution of food consumption to ecological overshoot and gaps in national/local food policies | Food consumption accounts for 30% of Portugal’s ecological overshoot; local policies poorly coordinated | Explore localized food strategies; improve policy integration, especially in urban areas |

| [101] | Basket-based choice experiment | N/A | Provide a tool to assess policy impacts on food choices more realistically | Consumers select multiple items; many products are complements rather than substitutes | Explore basket-based choice dynamics in different contexts |

| [102] | Document review | South Africa | Assess coordination and alignment of food system policies for food security | Policies are fragmented; limited adaptive management; poor monitoring and evaluation | Improve cross-sectoral coordination |

| [44] | Food-EPI Index | Poland | Assess strength of healthy food environment policies; identify gaps and prioritize improvements | Many indicators rated null/weak; top priority actions include food labeling and school nutrition training | Clarify socio-economic impacts; explore equity considerations in policy evaluation |

| [103] | Review | N/A | Place evaluation of food/agriculture policies in the context of quantitative policy assessment | Alternative indicators vary over time/context; policies need local adaptation | Further research on validity of alternative indicators |

| [104] | Dynamic fixed effects panel data model | China | Analyze impact of rice support policies on farmers’ rice acreage decisions | Support policies significantly increased rice area; influenced provincial-level choices | Investigate long-term impacts and environmental consequences; consider regional dynamics |

| [33] | Longitudinal analysis | England | Evaluate impact of school exclusion zones on number/type of food outlets | Significant changes in number/type of outlets; promoted healthier environments | Study different planning guidance types over time; consider external factors |

| [105] | Documents, observation, interviews | Valencia | Examine power dynamics in urban food governance and co-existence of governance spaces | Multiple power types coexist; longitudinal/transversal evaluation highlights tensions | Explore relation to new translocal governance instruments; study evolving urban governance frameworks |

| [58] | FAO-based framework adaptation, interviews, observations | Madrid | Assess effectiveness of urban food governance for food security | Governance mechanisms like UFS and policy platforms do not guarantee effective food security governance | Examine how urban governance can move beyond technocratic structures |

| [47] | Analysis of Food Metrics Reports | New York | Verify indicators | 51% of indicators improved, 40% declined; some limitations | Improve indicators and monitoring tools |

| [106] | Literature review | N/A | Measure social benefits | Benefits for community cohesion, diet, health; few studies on education/economy | Larger samples, cross-country studies, controlled trials |

| [107] | Interviews, indicator selection | N/A | Monitor food systems | Selected global indicators and baseline; data gaps exist | Fill data gaps, study system evolution, meet user needs |

| [108] | Semi-structured interviews | Toronto | Equity and health | Support for evidence on economic, health, and equity impacts; local data needed | Strengthen evidence for policy and risk management |

| [109] | Literature review and comparative analysis | US | Food Policy Councils impact | Impacts on food equity, local economy, environment, participation | Include more communities; fill gaps in quantitative data |

| [17] | Agroecological assessment, interviews, document review | Rome | Urban agriculture and local food policy | Strong agroecological potential; fragmented policy support; social and biodiversity benefits | Study food security, biodiversity, inequality; comparative urban studies |

| [110] | Document analysis and interviews | US and UK | Trans-local food governance | Local policies boost resilience, reduce inequities, foster alliances | Include social well-being, food justice, sustainability |

| [111] | Literature and qualitative analysis | N/A | Evidence-based policies | Better integration of research and policy; scientific data supports decisions | Use robust data, quantitative methods, predictive models |

| [31] | Qualitative analysis, documents, interviews | China | City Region Food Systems | Innovative policies; focus on urban–rural integration and green tech | Study tech role, urban–rural interactions; collect long-term data |

| [112] | Qualitative policy analysis and interviews | Rwanda | Translating national nutrition policies | Resource and coordination challenges; some progress in community programs | Improve coordination and integrate local initiatives |

| [113] | Geographic data, spatial analysis, semi-structured interviews | US | Explore role of small non-chain grocers in urban food access | Small non-chain stores provide fresh, diverse food in low-income areas, filling gaps left by supermarkets | Compare urban vs. rural access; evaluate local policies supporting small stores |

| [114] | LM3 economic analysis | France, Hungary, Italy, Poland, UK | Assess economic impacts of short food supply chains | Short supply chains keep revenue local, generating strong multiplier effects (LM3 > 2) | Capture multiplier differences along the supply chain; compare organic vs. conventional effects |

| [115] | Interviews | Portugal | Understand why urban food initiatives take time to become policy | Political engagement and funding are critical bottlenecks; gaps in monitoring, governance, and participatory processes slow policy translation | Study mechanisms to accelerate policy adoption and improve governance and evaluation |

References

- Mendes, W. Implementing social and environmental policies in cities: The case of food policy in Vancouver, Canada. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2008, 32, 942–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doernberg, A.; Horn, P.; Zasada, I.; Piorr, A. Urban food policies in German city regions: An overview of key players and policy instruments. Food Policy 2019, 89, 101782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.J.; Santini, F. The sustainability of “local” food: A review for policy-makers. Rev. Agric. Food Environ. Stud. 2022, 103, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S.; Hand, M.; Pra, M.; Pollack, S.; Ralston, K.; Smith, T.; Vogel, S.; Clark, S.; Lohr, L.; Low, S.; et al. Local Food Systems: Concepts, Impacts, and Issues. In Local Food Systems: Background and Issues; Diane Publishing: Collingdale, PA, USA, 2010; pp. 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Sibbing, L.; Candel, J.; Termeer, K. A comparative assessment of local municipal food policy integration in the Netherlands. Int. Plan. Stud. 2021, 26, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, D.; Carrascosa-García, M. Sustainable food policies without sustainable farming? Challenges for agroecology-oriented farmers in relation to urban (sustainable) food policies. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 105, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.L.; Fanzo, J.C.; Cogill, B. Understanding sustainable diets: A descriptive analysis of the determinants and processes that influence diets and their impact on health, food security, and environmental sustainability. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Cifuentes, M.; Freyer, B.; Sonnino, R.; Fiala, V. Embedding sustainable diets into urban food strategies: A multi-actor approach. Geoforum 2021, 122, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niza, S.; Rosado, L.; Ferrão, P. Urban metabolism methodological advances in urban material flow accounting based on the Lisbon case study. J. Ind. Ecol. 2009, 13, 384–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.; West, G. A unified theory of urban living. Nature 2010, 467, 912–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.T.; Lobao, L.M.; Betz, M.R. Collaborative Counties: Questioning the Role of Civil Society. Econ. Dev. Q. 2017, 31, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnino, R.; Tegoni, C.L.S.; De Cunto, A. The challenge of systemic food change: Insights from cities. Cities 2019, 85, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornaghi, C. Urban Agriculture in the Food-Disabling City: (Re)defining Urban Food Justice, Reimagining a Politics of Empowerment. Antipode 2017, 49, 781–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.A.; Früh-Müller, A.; Lehmann, I.; Schwarz, N. Linking food and land system research in Europe. Land Use Policy 2023, 131, 106692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dansero, E.; Marino, D.; Mazzocchi, G.; Nicolarea, Y. Lo Spazio delle Politiche Locali del Cibo: Temi, Esperienze e Prospettive; Celid: Torino, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moragues-Faus, A.; Morgan, K. Reframing the foodscape: The emergent world of urban food policy. Environ. Plan. A 2015, 47, 1558–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, D.; Curcio, F.; Felici, F.B.; Mazzocchi, G. Toward Evidence-Based Local Food Policy: An Agroecological Assessment of Urban Agriculture in Rome. Land 2024, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassi, M. The history of food security: Approaches and policies. In Understanding Food Insecurity: Key Features, Indicators, and Response Design; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 89–120. [Google Scholar]

- Candel, J.; Daugbjerg, C. Overcoming the dependent variable problem in studying food policy. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Giraldo, L.A.; Franco-Giraldo, Á. Review of food policy approaches: From food security to food sovereignty (2000–2013). Cadernos Saúde Pública 2015, 31, 1355–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Righettini, M.S.; Bordin, E. Exploring food security as a multidimensional topic: Twenty years of scientific publications and recent developments. Qual. Quant. 2023, 57, 2739–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji, M.; Himpel, F. Building Resilience in Food Security: Sustainable Strategies Post-COVID-19. Sustainability 2024, 16, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, D.A.; Clark, J.K.; Lounsbury, D.W.; Boswell, L.; Burns, M.; Jackson, M.B.; Mikelbank, K.; Donley, G.; Worley-Bell, L.Q.; Mitchell, J.; et al. Food system dynamics structuring nutrition equity in racialized urban neighborhoods. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergonzini, C. Just food transition: For a gender mainstreaming approach in urban food policies. A review of 20 cities. Cities 2024, 148, 104876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, D.; Vassallo, M.; Cattivelli, V. Urban food policies in Italy: Drivers, governance, and impacts. Cities 2024, 153, 105257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeman, G.; Dijkman, J.; Termeer, C. Enhancing food security through a multi-stakeholder process: The global agenda for sustainable livestock. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Med. Flum. 2021, 57, 444–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.; Dodd, W.; Nguyen-Viet, H.; Unger, F.; Le, T.T.H.; Dang-Xuan, S.; Skinner, K.; Papadopoulos, A.; Harper, S.L. How can climate change and its interaction with other compounding risks be considered in evaluation? Experiences from Vietnam. Evaluation 2023, 29, 228–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncube, A.; Kunguma, O.; Nyahwo, M.; Manombe, S. Nutritional vulnerability: An assessment of the 2010 feeding food programme in Mbire district, Zimbabwe, and its impact on pregnant women. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2017, 9, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Osabohien, R.; Karakara, A.A.; Ashraf, J.; Al-Faryan, M.A.S. Green Environment-Social Protection Interaction and Food Security in Africa. Environ. Manag. 2023, 71, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, S.; Qian, Z.; Santini, G.; Ni, J.; Bing, Y.; Zhu, L.; Fu, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, N. Towards the high-quality development of City Region Food Systems: Emerging approaches in China. Cities 2023, 135, 104212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karetny, J.; Hoy, C.; Usher, K.M.; Clark, J.K.; Conroy, M.M. Planning toward sustainable food systems: An exploratory assessment of local U.S. food system plans. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2022, 11, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.; Kirkman, S.; Albani, V.; Goffe, L.; Akhter, N.; Hollingsworth, B.; von Hinke, S.; Lake, A. The impact of school exclusion zone planning guidance on the number and type of food outlets in an English local authority: A longitudinal analysis. Health Place 2021, 70, 102600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabur, A.M.; Alsharief, L.A.; Amer, S.A. Determinants of Healthy Food Consumption and the Effect of Saudi Food Related Policies on the Adult Saudi Population, a National Descriptive Assessment 2019. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2022, 10, 1058–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Othmen, M.A.; Kavouras, J.H. Developing a community-based local food system in Will County, Illinois: Insights from stakeholders’ viewpoints. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2022, 11, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, J.D.; Lelekacs, J.M.; Hofing, G.L.; Stout, R.; Marshall, M.; Davis, K. Integrating food systems and local food in family and consumer sciences: Perspectives from the pilot Extension Master Food Volunteer program. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2020, 9, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Range, C.; O’Hara, S.; Jeffery, T.; Toussaint, E.C. Measuring the Effectiveness of Food Policy Councils in Major Cities in the United States. Foods 2023, 12, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, Y.; Van Rysselberge, P.; Macura, B.; Persson, U.M.; Hatab, A.A.; Jonell, M.; Lindahl, T.; Röös, E. Effects of public policy interventions for environmentally sustainable food consumption: A systematic map of available evidence. Environ. Evid. 2024, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambeses-Franco, C.; González-García, S.; Feijoo, G.; Moreira, M.T. Driving commitment to sustainable food policies within the framework of American and European dietary guidelines. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 150741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steils, N.; Obaidalahe, Z. “Social food”: Food literacy co-construction and distortion on social media. Food Policy 2020, 95, 101932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscaroli, E.; Braschi, I.; Cirillo, C.; Fargue-Lelièvre, A.; Modarelli, G.C.; Pennisi, G.; Righini, I.; Specht, K.; Orsini, F. Reviewing chemical and biological risks in urban agriculture: A comprehensive framework for a food safety assessment of city region food systems. Food Control 2021, 126, 107050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnoff, S.M.; Schmit, T.M.; Bilinski, C.B. Economic impact assessment of public incentives to support farm-to-school food purchases. Food Policy 2023, 121, 102545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiki, G.; Wanjohi, M.N.; Barnes, A.; Bash, K.; Muthuri, S.; Amugsi, D.; Doughman, D.; Kimani, E.; Vandevijvere, S.; Holdsworth, M.; et al. Benchmarking food environment policies for the prevention of diet-related noncommunicable diseases in Kenya: National expert panel’s assessment and priority recommendations. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaniuk, P.; Kaczmarek, K.; Brukało, K.; Grochowska-Niedworok, E.; Łobczowska, K.; Banik, A.; Luszczynska, A.; Poelman, M.; Harrington, J.M.; Vandevijvere, S.; et al. The Healthy Food Environment Policy Index in Poland: Implementation Gaps and Actions for Improvement. Foods 2022, 11, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakerveld, J.; Woods, C.; Hebestreit, A.; Brenner, H.; Flechtner-Mors, M.; Harrington, J.M.; Kamphuis, C.B.; Laxy, M.; Luszczynska, A.; Mazzocchi, M.; et al. Advancing the evidence base for public policies impacting on dietary behaviour, physical activity and sedentary behaviour in Europe: The Policy Evaluation Network promoting a multidisciplinary approach. Food Policy 2020, 96, 101873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, H.; Säll, S.; Abouhatab, A.; Ahlgren, S.; Berggren, Å.; Hallström, E.; Lundqvist, P.; Persson, U.M.; Rydhmer, L.; Röös, E.; et al. An indicator framework to guide food system sustainability transition—The case of Sweden. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 22, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberg, N.; Willingham, C.; Cohen, N. The role of metrics in food policy: Lessons from a decade of experience in New York City. Community Dev. 2018, 8, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalli, G.; Smith, K.; Woodside, J.; Defeyter, G.; Skafida, V.; Morgan, K.; Martin, C. A brief review of Secondary School Food Policy (SSFP) approaches in the UK from 2010 to 2022. Nutr. Food Sci. 2024, 54, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monticone, F.; Samoggia, A.; Specht, K.; Schröter, B.; Rossi, G.; Wissman, A.; Bertazzoli, A. Harvesting connections: The role of stakeholders’ network structure, dynamics and actors’ influence in shaping farmers’ markets. Agric. Human Values 2024, 41, 1503–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, A.O.; Sušnik, J.; Masia, S.; Jewitt, G. Policy coherence assessment of water, energy, and food resources policies in the Tana River Basin, Kenya. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 159, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarella, C.; Lamoureaux, Y.; Pires, A.A.F.; Surls, R.; Bennaton, R.; Van Soelen Kim, J.; Grady, S.; Ramos, T.M.; Koundinya, V.; DiCaprio, E. A preliminary assessment of food policy obstacles in California’s produce recovery networks. Agric. Hum. Values 2023, 40, 1239–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaal, S.A.L.; Dessein, J.; Wind, B.J.; Rogge, E. Social justice-oriented narratives in European urban food strategies: Bringing forward redistribution, recognition and representation. Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 38, 709–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marull, J.; Padró, R.; Cirera, J.; Giocoli, A.; Pons, M.; Tello, E. A socioecological integrated analysis of the Barcelona metropolitan agricultural landscapes. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 51, 101368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arosemena, J.D.; Toboso-Chavero, S.; Adhikari, B.; Villalba, G. Closing the nutrient cycle in urban areas: The use of municipal solid waste in peri-urban and urban agriculture. Waste Manag. 2024, 183, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerutti, A.K.; Contu, S.; Ardente, F.; Donno, D.; Beccaro, G.L. Carbon footprint in green public procurement: Policy evaluation from a case study in the food sector. Food Policy 2016, 58, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska-Chmielewska, A.; Wielicka-Regulska, A.; Mruk-Tomczak, D. Assessment of the usage of VAT tax as a sustainable and environmentally friendly food policy tool: Evidence from Poland. Econ. Environ. 2023, 86, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doernberg, A.; Piorr, A.; Zasada, I.; Wascher, D.; Schmutz, U. Sustainability assessment of short food supply chains (SFSC): Developing and testing a rapid assessment tool in one African and three European city regions. Agric. Hum. Values 2022, 39, 885–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbian, T.; de Luis Romero, E. The role of cities in good governance for food security: Lessons from Madrid’s urban food strategy. Territ. Polit. Gov. 2023, 11, 794–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polman, D.; Bazzan, G. Governance tools for urban food system policy innovations in the Milano Urban Food Policy Pact. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2023, 30, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, O.; Koya, S.F.; Corkish, C.; Abdalla, S.M.; Galea, S. Food, big data, and decision-making: A scoping review—The 3-D commission. J. Urban Health 2021, 98 (Suppl. 1), 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanham, D.; Leip, A. Sustainable food system policies need to address environmental pressures and impacts: The example of water use and water stress. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 730, 139151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljand, M.; Eckerberg, K. Using systematic reviews to inform environmental policy-making. Evaluation 2022, 28, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadad, S.; Aharony, N.; Raban, D.R. Unlocking Scholarly Realms: Revealing Discipline-Specific Publication and Citation Benefits in Open Access. Proc. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 61, 925–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Grave, R.B.; Rust, N.A.; Reynolds, C.J.; Watson, A.W.; Smeddinck, J.D.; Monteiro, D.M.S. A catalogue of UK household datasets to monitor transitions to sustainable diets. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 24, 100344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewert, F.; Baatz, R.; Finger, R. Agroecology for a sustainable agriculture and food system: From local solutions to large-scale adoption. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2023, 15, 351–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, B.B.; Schmit, T.M.; Kay, D. Assessing the economic impacts of food hubs on regional economies: A framework that includes opportunity cost. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2016, 45, 143–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godette, S.K.; Beratan, K.; Nowell, B. Barriers and facilitators to local food market development: A contingency perspective. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2015, 5, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.C.; Fernandez, A.; Jha, S. Beyond the grumpy rich man and the happy peasant: Mixed methods and the impact of food security on subjective dimensions of wellbeing in India. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2016, 44, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, V.; Romero, D.; Musicki, A.; Guimarães Pereira, Â.; Peñate, B. Co-creating narratives for WEF nexus governance: A Quantitative Story-Telling case study in the Canary Islands. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, T.; Davis, D.E. Collective consumption and food system complexity. Transdiscipl. J. Eng. Sci. 2022, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.G.; DeLong, A.N.; Diaz, J.M. Commercial urban agriculture in Florida: A qualitative needs assessment. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2023, 38, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantamaturapoj, K.; McGreevy, S.R.; Thongplew, N.; Akitsu, M.; Vervoort, J.; Mangnus, A.; Ota, K.; Rupprecht, C.D.; Tamura, N.; Spiegelberg, M.; et al. Constructing practice-oriented futures for sustainable urban food policy in Bangkok. Futures 2022, 139, 102949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoloye, A.; Schouboe, S.; Misiaszek, C.; Harding, J.; Stowers, K.C.; Bassarab, K.; Calancie, L. Developing a food system indicators database to facilitate local food systems assessments: Using a scoping review approach. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2023, 13, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birol, E.; Meenakshi, J.V.; Oparinde, A.; Perez, S.; Tomlins, K. Developing country consumers’ acceptance of biofortified foods: A synthesis. Food Sec. 2015, 7, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannini, M.; Forno, F. Doing transdisciplinary action research: A critical assessment of an Italian lab-like sustainable food initiative. JEOD 2023, 12, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, K.; Wong, M. Evaluating seasonal food storage and credit programs in east Indonesia. J. Dev. Econ. 2015, 115, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossenson, S.; Giglia, R.; Pulker, C.E.; Chester, M.; McStay, C.; Pollard, C.M. Evidence for initiating food safety policy: An assessment of the quality and safety of donated food at an Australian food bank. Food Policy 2024, 123, 102589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitas, N.; Harmáčková, Z.V.; Anticamara, J.A.; Arneth, A.; Badola, R.; Biggs, R.; Blanchard, R.; Brotons, L.; Cantele, M.; Coetzer, K.; et al. Exploring the usefulness of scenario archetypes in science-policy processes. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 24, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, E.A.F.; Santos, T.D.R.; Rist, S. Family farmers’ perceptions of the impact of public policies on the food system: Findings from Brazil’s semi-arid region. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 556732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwin, L.; Brekken, C.A.; Trant, L. Farm Direct at five years: An early assessment of Oregon’s farm-focused cottage food law. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2018, 8, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasada, I.; Schmutz, U.; Wascher, D.; Kneafsey, M.; Corsi, S.; Mazzocchi, C.; Monaco, F.; Boyce, P.; Doernberg, A.; Sali, G.; et al. Food beyond the city–Analysing foodsheds and self-sufficiency for different food system scenarios in European metropolitan regions. City Cult. Soc. 2019, 16, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, K.; Sands, C.; Angarita Horowitz, D.; Totman, M.; Maitín, M.; Rosado, J.S.; Colon, J.; Alger, N. Food justice youth development: Using Photovoice to study urban school food systems. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, B.J.; Scholz, A. Food security, food insecurity, and Canada’s national food policy: Meaning, measures, and assessment. Outlook Agric. 2022, 51, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R. FoodLink—A Network for Driving Food Transition in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area. Land 2022, 11, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crona, B.I.; Wassénius, E.; Jonell, M.; Koehn, J.Z.; Short, R.; Tigchelaar, M.; Daw, T.M.; Golden, C.D.; Gephart, J.A.; Allison, E.H.; et al. Four ways blue foods can help achieve food system ambitions across nations. Nature 2023, 616, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, R.T.; Fraser, K.T.; Cohen, N. From multiple streams to a torrent: A case study of food policymaking and innovations in New York during the COVID-19 emergency. Cities 2023, 136, 104222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surls, R.; Feenstra, G.; Golden, S.; Galt, R.; Hardesty, S.; Napawan, C.; Wilen, C. Gearing up to support urban farming in California: Preliminary results of a needs assessment. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2015, 30, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowitt, K.; Slater, J.; Rutta, E. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on food systems in Manitoba, Canada and ways forward for resilience: A scoping review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 7, 1214361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Alvarez-Coque, J.M.; Abdullateef, O.; Fenollosa, L.; Ribal, J.; Sanjuan, N.; Soriano, J.M. Integrating sustainability into the multi-criteria assessment of urban dietary patterns. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2021, 36, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippini, R.; Marraccini, E.; Lardon, S.; Bonari, E. Is the choice of a farm’s commercial market an indicator of agricultural intensity? Conventional and short food supply chains in periurban farming systems. Ital. J. Agron. 2016, 11, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, R.; El Benni, N.; Finger, R. Lessons learned and policy implications from 20 years of Swiss agricultural policy reforms: A review of policy evaluations. Bio-Based Appl. Econ. 2024, 13, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, K.G.; Bezerra, I.W.; Pereira, G.S.; Costa, R.M.; Souza, A.M.; Oliveira, A.G. Long-term effect of the Brazilian Workers’ Food Program on the nutritional status of manufacturing workers: A population-based prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vervoort, J.M.; Milkoreit, M.; van Beek, L.; Mangnus, A.C.; Farrell, D.; McGreevy, S.R.; Ota, K.; Rupprecht, C.D.; Reed, J.B.; Huber, M. Not just playing: The politics of designing games for impact on anticipatory climate governance. Geoforum 2022, 137, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, S.; Wiek, A.; Bloemertz, L.; Bornemann, B.; Granchamp, L.; Villet, C.; Gascón, L.; Sipple, D.; Blanke, N.; Lindenmeier, J.; et al. Opportunities and challenges of food policy councils in pursuit of food system sustainability and food democracy—A comparative case study from the Upper-Rhine region. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 916178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biehl, E.; Buzogany, S.; Baja, K.; Neff, R.A. Planning for a resilient urban food system: A case study from Baltimore City, Maryland. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2018, 8, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, M.F.; Lee, Y.N.; Just, D.R. Producer attitudes toward output price risk: Experimental evidence from the lab and from the field. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 102, 806–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris-Fry, H.; Lamson, L.; Roett, K.; Katz, E. Reducing gender bias in household consumption data: Implications for food fortification policy. Food Policy 2022, 110, 102279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, E.; Gressier, M.; Li, D.; Brown, T.; Mounsey, S.; Olney, J.; Sassi, F. Effectiveness and policy implications of health taxes on foods high in fat, salt, and sugar. Food Policy 2024, 123, 102599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C.; Chowdhury, F.S.; Rashid, M.; Dhali, S.A.; Jahan, F. Squaring the circle: Reconciling the need for rigor with the reality on the ground in resilience impact assessment. World Dev. 2017, 97, 212–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, A.; Pires, S.M.; Iha, K.; Alves, A.A.; Lin, D.; Mancini, M.S.; Teles, F. Sustainable food transition in Portugal: Assessing the Footprint of dietary choices and gaps in national and local food policies. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 141307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, V.; Lusk, J.L. The basket-based choice experiment: A method for food demand policy analysis. Food Policy 2022, 109, 102252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushitor, S.B.; Drimie, S.; Davids, R.; Delport, C.; Hawkes, C.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Ngidi, M.; Slotow, R.; Pereira, L.M. The complex challenge of governing food systems: The case of South African food policy. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josling, T. The historical evolution of alternative metrics for developing countries’ food and agriculture policy assessment. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2018, 10, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Gardebroek, C.; Heerink, N. The impact of Chinese rice support policies on rice acreages. Food Secur. 2024, 16, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbian, T.; Escario-Chust, A.; Palau-Salvador, G.; Segura-Calero, S. The multiple and contested worlds of urban food governance: The case of the city of Valencia. Cities 2023, 141, 104516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, R.T.; Cohen, N.; Israel, M.; Specht, K.; Fox-Kämper, R.; Fargue-Lelièvre, A.; Poniży, L.; Schoen, V.; Caputo, S.; Kirby, C.K.; et al. The socio-cultural benefits of urban agriculture: A review of the literature. Land 2022, 11, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.R.; Fanzo, J.; Haddad, L.; Herrero, M.; Moncayo, J.R.; Herforth, A.; Remans, R.; Guarin, A.; Resnick, D.; Covic, N.; et al. The state of food systems worldwide in the countdown to 2030. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 1090–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, K.; Archbold, J.; Baker, L.E.; Elton, S.; Cole, D.C. Toronto municipal staff and policy-makers’ views on urban agriculture and health: A qualitative study. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2018, 8, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calancie, L.; Cooksey-Stowers, K.; Palmer, A.; Frost, N.; Calhoun, H.; Piner, A.; Webb, K. Toward a community impact assessment for food policy councils: Identifying potential impact domains. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2018, 8, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, R.; Moragues-Faus, A. Towards a trans-local food governance: Exploring the transformative capacity of food policy assemblages in the US and UK. Geoforum 2019, 98, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Benni, N.; Grovermann, C.; Finger, R. Towards more evidence-based agricultural and food policies. Q Open 2023, 3, qoad003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iruhiriye, E.; Olney, D.K.; Frongillo, E.A.; Niyongira, E.; Nanama, S.; Rwibasira, E.; Mbonyi, P.; Blake, C.E. Translation of policy for reducing undernutrition from national to sub-national levels in Rwanda. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 977–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, K.Y.; Tong, D.; Plane, D.A.; Buechler, S. Urban food accessibility and diversity: Exploring the role of small non-chain grocers. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 125, 102275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłoczko-Gajewska, A.; Malak-Rawlikowska, A.; Majewski, E.; Wilkinson, A.; Gorton, M.; Tocco, B.; Wąs, A.; Saïdi, M.; Török, Á.; Veneziani, M. What are the economic impacts of short food supply chains? A local multiplier effect (LM3) evaluation. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2024, 31, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, C. What makes food policies happen? Insights from Portuguese initiatives. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2019, 9, 235–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Journals | No. of Articles |

|---|---|

| Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development | 11 |

| Food Policy | 8 |

| Agriculture and Human Values | 4 |

| Food Security | 4 |

| Cities | 3 |

| Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems | 3 |

| Geoforum | 3 |

| Land | 3 |

| Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems | 3 |

| Science of the Total Environment | 3 |

| Annual Review of Resource Economics | 2 |

| European Urban and Regional Studies | 2 |

| Foods | 2 |

| PLOS One | 2 |

| Agricultural and Resource Economics Review | 1 |

| American Journal of Agricultural Economics | 1 |

| Applied Geography | 1 |

| Bio-Based and Applied Economics | 1 |

| City, Culture and Society | 1 |

| Current Research in Nutrition and Food Science | 1 |

| Ecology and Society | 1 |

| Economics and Environment | 1 |

| Ecosystem Services | 1 |

| Environmental and Sustainability Indicators | 1 |

| Environmental Evidence | 1 |

| Environmental Management | 1 |

| Environmental Science and Policy | 1 |

| Food Control | 1 |

| Futures | 1 |

| Global Food Security | 1 |

| Health and Peace | 1 |

| International Planning Studies | 1 |

| Italian Journal of Agronomy | 1 |

| Italian Review of Agricultural Economics | 1 |

| Journal of Development Economics | 1 |

| Journal of Disaster Risk Studies | 1 |

| Journal of Entrepreneurial and Organizational Diversity | 1 |

| Local Environment | 1 |

| Nature | 1 |

| Nature Food | 1 |

| Nutrition & Food Science | 1 |

| Outlook on Agriculture | 1 |

| Oxford Development Studies | 1 |

| Q Open | 1 |

| Sustainability Science | 1 |

| Territory, Politics, Governance | 1 |

| The International Journal of Life Cycle | 1 |

| Transdisciplinary Journal of Engineering & Science | 1 |

| Waste Management | 1 |

| Country | No. | Country | No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 17 | Italy | 6 |

| Spain | 6 | United Kingdom | 4 |

| Canada | 3 | France | 2 |

| Poland | 2 | Kenya | 2 |

| Bangladesh | 2 | China | 2 |

| Brazil | 2 | Sweden | 1 |

| Austria | 1 | Switzerland | 1 |

| Portugal | 1 | India | 1 |

| Indonesia | 1 | Australia | 1 |

| Zimbabwe | 1 | Rwanda | 1 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | Hungary | 1 |

| Germany | 1 | Slovenia | 1 |

| New Zealand | 1 | Peru | 1 |

| Macro Topic | Specific Subtopics | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| FOOD POLICIES AND SUSTAINABILITY | Integration of food policies, sustainable diets, food recovery, environmental policies, food security programs, public policies influencing food behavior, innovations in food systems, sustainable food consumption, local food markets. | 20 | 22.7 |

| AGRICULTURE AND CULTIVATION | Urban agriculture, metropolitan agriculture, commercial urban agriculture, agroecology, farm-to-school food procurement, seasonal food storage. | 12 | 13.6 |

| FOOD SYSTEMS AND FOOD HUBS | Local food systems, food hubs, food supply chains based on food, perceptions of family farmers, food consumption, implementation of local food programs. | 11 | 12.5 |

| HEALTH AND NUTRITION | Healthy food consumption, food justice, malnutrition, obesity, access to food, food security. | 10 | 11.4 |

| POLICY INTEGRATION AND GOVERNANCE | Coherence and integration of food policies, governance of urban food systems, governance of food systems, food policy design, complexity of food systems. | 10 | 11.4 |

| PUBLIC HEALTH AND OBESITY | Public policy interventions for environmentally sustainable food consumption, health taxes on food systems. | 6 | 6.8 |

| ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT AND RESOURCES | Environmental sustainability, water-energy-food nexus, climate impact, resilience of food security, water use. | 7 | 8.0 |

| ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL ISSUES | Social justice in food systems, equity and inclusion in food systems, sustainable public procurement (SPP). | 5 | 5.7 |

| FOOD WASTE AND FOOD SECURITY | Waste management in agriculture, reduction of food waste, food donation programs. | 4 | 4.5 |

| MONITORING AND EVALUATION OF FOOD SYSTEMS | Monitoring of food systems, food system indicators, system assessment capacity, food system evaluation. | 3 | 3.4 |

| Methodology | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| Literature review | 24 |

| Focus groups | 6 |

| Interviews | 19 |

| Dataset analysis | 5 |

| Document analysis | 6 |

| Netnography | 1 |

| Content analysis | 4 |

| Comparative study | 3 |

| Observation | 3 |

| Conceptual modeling | 4 |

| Analytical/statistical modeling (e.g., LCA, IMPLAN) | 7 |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | 1 |

| Policy Environment Network (PEN) approach | 1 |

| Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) | 1 |

| Econometric analysis | 4 |

| Surveys | 5 |

| Life cycle assessment (LCA) | 3 |

| Carbon footprint analysis | 1 |

| Laboratory experiments | 4 |

| Cost–benefit analysis | 1 |

| Photovoice experiments | 1 |

| Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) | 1 |

| Nutritional value analysis | 1 |

| Game theory analysis | 1 |

| Water footprint assessment | 1 |

| Ecological footprint assessment | 1 |

| Ecological assessment | 1 |

| Geographic data analysis | 1 |

| Case study | 74 |

| Mixed methods | 21 |

| Dimension | Variables | Indicators | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy Coherence | - | - | [48,49,50] |

| Integration | Level of coordination between sectors and connection with other areas (e.g., environment, economy, education). | Level of coordination between sectors | [5,36,48,49,51] |

| Governance and Leadership | Involvement of key actors; social justice. | Number and quality of participation initiatives (e.g., local communities, children) | [37,52] |

| Metabolic Efficiency | Optimal energy consumption in agricultural systems. | Percentage of non-renewable resources used | [53] |

| Biodiversity Conservation | Energy-landscape integration. | Presence of measures to preserve habitats and species | [53] |

| Ecosystem Services | Nutrient recycling in soil, carbon storage, agricultural production. | Environmental indicators (e.g., carbon stock) | [53] |

| Footprint and Environmental Impact | Life cycle assessment (LCA); nutrient demand. | Carbon footprint and nutrient demand | [54,55] |

| Eating Behaviors | Eating habits, physical activity, and sedentary behaviors. | Frequency of physical activity, consumption of healthy foods | [45] |

| Social Acceptance | Public acceptance of food policies. | Feedback and evaluations from stakeholders | [56] |

| Structural and Operational Challenges | Institutional obstacles, lack of coordination, inadequate funding. | Number and type of challenges reported | [51] |

| Food System Sustainability | Healthy and adequate diet. | Average intake of critical nutrients relative to dietary guidelines | [46] |

| Food Safety | Foodborne diseases. | Clinical cases of foodborne diseases (per year and per number of individuals) | [46,57] |

| Food Availability | National production. | Nutrients and fruit/vegetables produced nationally relative to population need | [46] |

| Just and Fair Food Systems | Working conditions. | Absence of occupational disease due to work-related accidents | [46] |

| Biodiversity Conservation | Terrestrial biodiversity. | Abundance and diversity of pollinators | [46] |

| Natural Resource Management | Water use. | Total blue water used for food production | [46] |

| Governance | Effectiveness and efficiency, equality and equity, accountability, responsiveness, transparency, participation, protection of human rights and food. | - | [31,46,58] |

| Economic Viability | Return on capital. | Total return on capital (%) for food companies | [46] |

| Diversity in Production | Level of diversity. | Entropy index | [46] |

| Innovation in Urban Food Policy | - | Number of recognitions in the “Milan Pact Awards” | [59] |

| Active Integrated Government Body | - | Presence of an active governmental body for food policies | [59] |

| Active Multi-Stakeholder Structure | - | Presence of an active food planning structure | [59] |

| Integrated Food Policy Strategy | - | Presence of an integrated food policy strategy | [59] |

| Policy Development Mapping | - | Presence of a local initiative inventory used for food policy development | [59] |

| Policy Development Monitoring | - | Presence of a mechanism to collect and analyze urban food system data | [59] |

| Information and Awareness | Awareness of food consumption and production models. | - | [57] |

| Support Structures and Tools | Robust data framework and indicators, educational campaigns, and participatory food governance. | - | [57] |

| Administrative and Governmental Capacity | Adequate human resources with knowledge and skills, trans-departmental structure or coordination mechanisms, organizational autonomy. | - | [57] |

| Articulation with Other Government Levels | Regulations and government incentives (e.g., sustainable public procurement). | - | [57] |

| Local Government Functions | Integration of food issues in territorial planning, promotion of urban–rural connections, coordination mechanisms among stakeholders in governance. | - | [57] |

| Strategic Policies | Strong political commitment to healthy and sustainable diets, strategies to reallocate priorities in agricultural production and promote agri-food innovation, plans to reduce food waste, incentives to reconnect farmers and citizens. | - | [57] |

| Food Security | Per capita food production. | - | [57] |

| Sustainable Environment | Policies and institutions for environmental sustainability. | - | [57] |

| Social Protection | Social coverage policies. | - | [57] |

| Arable Land | Hectares of arable land. | - | [57] |

| Agricultural Credit | Total agricultural credit. | - | [57] |

| Technology and Information | Percentage of the population using the internet. | - | [57] |

| Agricultural Employment | Percentage of employment in agriculture. | - | [57] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moramarco, L.; di Santo, N.; Di Sparti, D.; Petrontino, A.; Moro, G.; Santoro, F.; Fucilli, V. Assessing Food Policies for Sustainability Transitions: A Scoping Review of Evaluation Methods. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188105

Moramarco L, di Santo N, Di Sparti D, Petrontino A, Moro G, Santoro F, Fucilli V. Assessing Food Policies for Sustainability Transitions: A Scoping Review of Evaluation Methods. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188105

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoramarco, Loretta, Naomi di Santo, Daniele Di Sparti, Alessandro Petrontino, Giuseppe Moro, Francesco Santoro, and Vincenzo Fucilli. 2025. "Assessing Food Policies for Sustainability Transitions: A Scoping Review of Evaluation Methods" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188105

APA StyleMoramarco, L., di Santo, N., Di Sparti, D., Petrontino, A., Moro, G., Santoro, F., & Fucilli, V. (2025). Assessing Food Policies for Sustainability Transitions: A Scoping Review of Evaluation Methods. Sustainability, 17(18), 8105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188105