Responsible Entrepreneurship Through Public Eyes: A Qualitative Exploration of Moral and Sustainable Expectations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Background

2.1. Responsible Entrepreneurship: Scope and Distinctions

2.2. Responsible Entrepreneurship’s Social Legitimacy and Public Accountability

2.3. Responsible Entrepreneurship and Citizen Perspectives

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Research Design: A Social Constructionist Epistemology

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection Strategy

3.3. Research Instruments and Analytical Procedures

4. Results

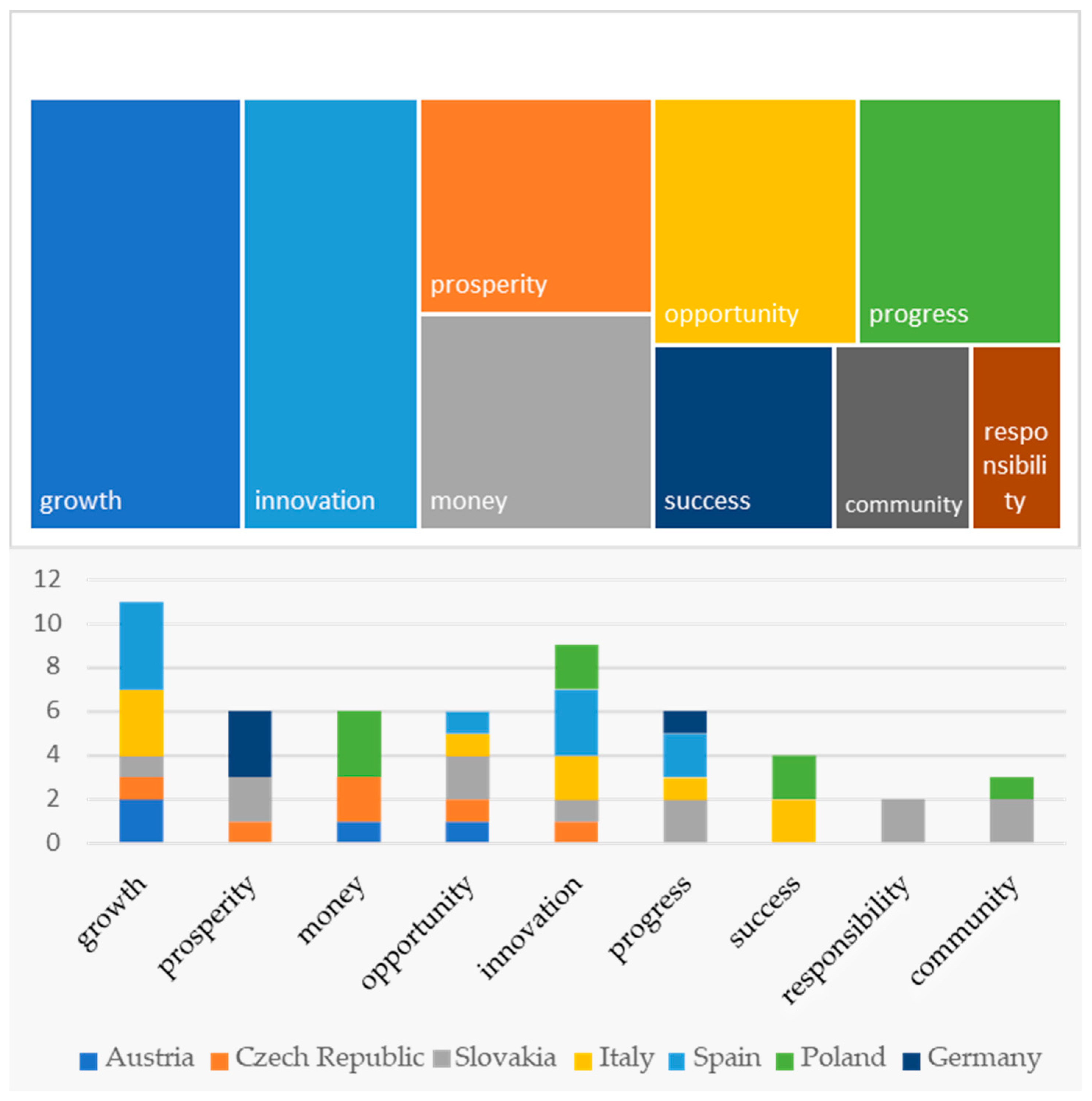

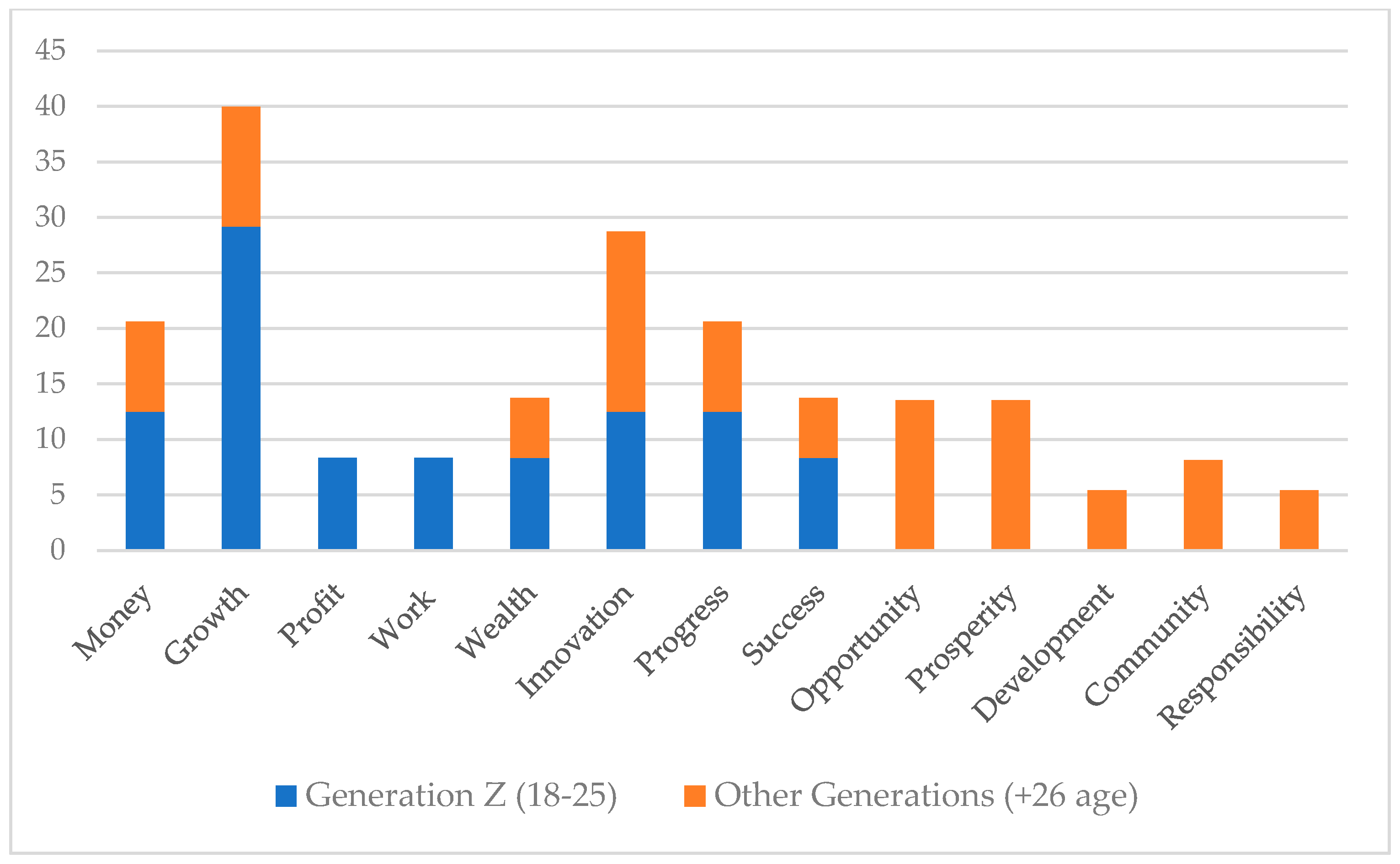

4.1. Perceptions on Business’ Purposes and Difficulties

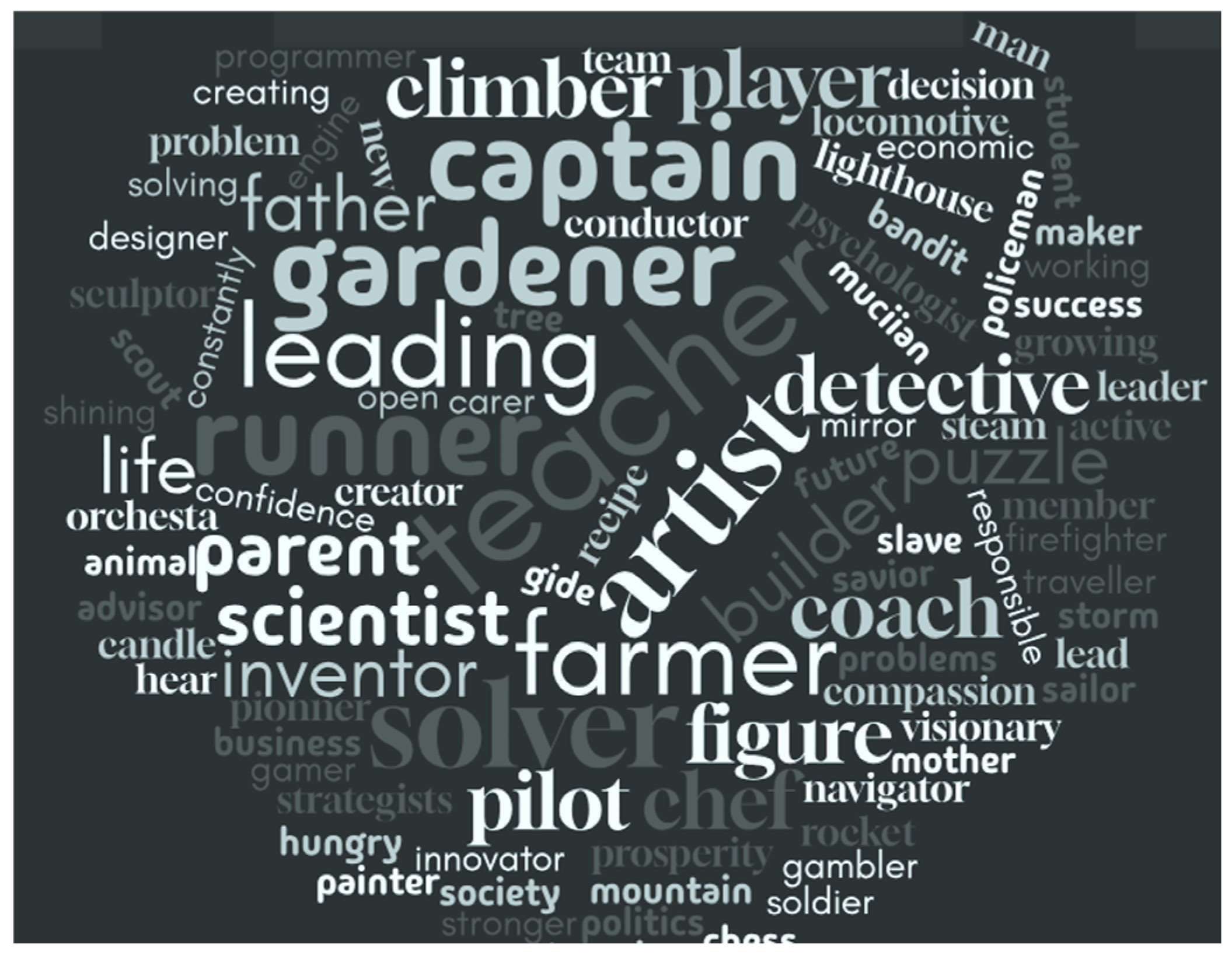

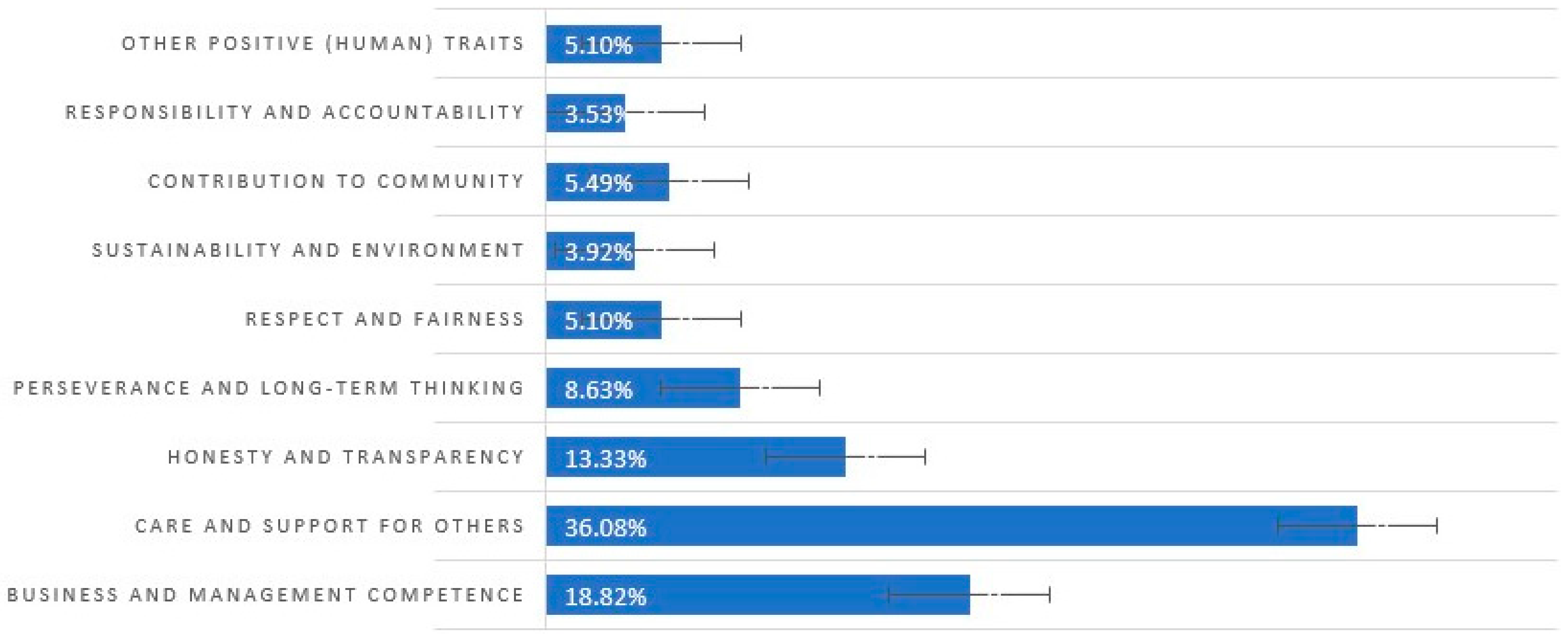

4.2. Metaphorical Associations with Entrepreneurs and Responsible Entrepreneurs

4.3. Citizens’ Role in Supporting Responsible Transformation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Research Lines

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Illustrative Categorization of Metaphors About the Figure of the Entrepreneur by Country and Valance

| Country | Valance | Example of Metaphor | Interpretation Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Positive | A captain guiding a small ship | Responsible leadership, guidance; the entrepreneur steers and protects the venture and its people. |

| Austria | Neutral | A puzzle solver | Analytical ability; resolving complex issues without strong positive or negative moral connotation. |

| Austria | Negative | A person balancing on a rope | Risk, precariousness; highlights instability and vulnerability in entrepreneurial activity. |

| Czech R. | Positive | A sculptor, shaping ideas | Creativity and transformation; brings abstract ideas into tangible forms. |

| Czech R. | Neutral | A chameleon | Adaptability; changing roles and behaviors depending on the environment, without clear moral connotation. |

| Czech R. | Negative | A gambler, betting everything | Risk, recklessness; decision-making marked by chance and imprudence. |

| Germany | Positive | As oil in economic engine | Essential, facilitator of progress; makes the system work. |

| Germany | Neutral | A person on his/her own | Independence, self-reliance; no clear positive or negative evaluation. |

| Germany | Negative | A gambler | High risk, imprudence, reliance on luck. |

| Italy | Positive | A sailor, always ready for the storm | Resilience, adaptability, preparedness for challenges. |

| Italy | Negative | A tightrope walker, always in precarious balance | Instability, risk, constant danger of falling, precarious balance. |

| Poland | Positive | A chef creating a new recipe | Creativity, combination of resources, value creation. |

| Poland | Neutral | A striker on a football team | Goal-oriented, competitive, focus on results. |

| Poland | Negative | A bandit | Opportunism, law-breaking, unethical. |

| Slovakia | Positive | A teacher inspiring other | Guiding, educating, positive influence. |

| Slovakia | Neutral | A gamer solving puzzles | Analytical skills, problem-solving, perseverance. |

| Spain | Positive | A programmer debugging society | Problem-solving, innovation, societal impact. |

| Spain | Neutral | A Scout preparing for challenges | Preparation, anticipation, readiness. |

References

- George, G.; Fewer, T.J.; Lazzarini, S.; McGahan, A.M.; Puranam, P. Partnering for grand challenges: A review of organizational design considerations in public–private collaborations. J. Manag. 2024, 50, 10–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, F.; Rossignoli, C.; Zardini, A. Grand challenges and entrepreneurship: Emerging issues, research streams, and theoretical landscape. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 1673–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, I. Transformational business models, grand challenges, and social impact. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, G.D.; Waldron, T.L.; Gianiodis, P.T.; Espina, M.I. E pluribus unum: Impact entrepreneurship as a solution to grand challenges. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 33, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Corporate Social Responsibility, Responsible Business Conduct, and Business & Human Rights: Overview of Progress (Commission Staff Working Document, SWD (2019) 143 Final). European Union: Brussels. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/34482 (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- OECD. OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/investment/due-diligence-guidance-for-responsible-business-conduct.html (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Carpentier, C.L.; Braun, H. Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development: A powerful global framework. J. Int. Counc. Small Bus. 2020, 1, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Maldonado-Briegas, J.J. Sustainable entrepreneurial culture programs promoting social responsibility: A European regional experience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiba, S.; van Rijnsoever, F.J.; Hekkert, M.P. Firms with benefits: A systematic review of responsible entrepreneurship and corporate social responsibility literature. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, S.; Nguyen, N.P. Responsible entrepreneurship, social innovation, and entrepreneurial performance: Does commitment to SDGs matter? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 4887–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heucher, K.; Alt, E.; Soderstrom, S.; Scully, M.; Glavas, A. Catalyzing action on social and environmental challenges: An integrative review of insider social change agents. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2024, 18, 295–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledano, N. Restoring the Garden of Eden: A Ricoeurian view of the ethics of environmental entrepreneurship. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2022, 31, 1174–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heigl, J.; Müller, M.; Gotling, N.; Proyer, M. Justice, What a Dream!—Mapping Intersections of Sustainability and Inclusion. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, N.; Kiefer, K.; York, J.G. Distinctions not dichotomies: Exploring social, sustainable, and environmental entrepreneurship. In Social and Sustainable Entrepreneurship; Lumpkin, G.T., Katz, J.A., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2011; pp. 201–229. [Google Scholar]

- Adomako, S.; Tran, M.D. Responsible Entrepreneurship and Social Legitimacy in Turbulent and Demanding Market Environments. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 3278–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Responsible Entrepreneurship: A Collection of Good Practice Cases Among Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Across Europe; Enterprise Publications: Brussels, Belgium, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, S.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Hansen, E.G. Business models for sustainability: A co-evolutionary analysis of sustainable entrepreneurship, innovation, and transformation. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 264–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallaster, C.; Kraus, S.; Kailer, N.; Baldwin, B. Responsible entrepreneurship: Outlining the contingencies. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 25, 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress-Ludwig, M.; Funcke, S.; Böhm, M.; Ruppert-Winkel, C. A citizen survey in the district of Steinfurt, Germany: Insights into the local perceptions of the social and environmental activities of enterprises in their region. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżewska, M.; Szczygieł, E.; Tsaples, G.; Manou, D.B.; Papathanasiou, J. The Future of Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Youth Perspectives in Greece and Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemczyk, A.; Gródek-Szostak, Z.; Adler, D.; Niewiadomski, M.; Benková, E. Green entrepreneurship: Knowledge and perception of students and professionals from Poland and Slovakia. Sustainability 2023, 16, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D. Business Ethics: Managing Corporate Citizenship and Sustainability in the Age of Globalization; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, A.R.; Warren, L. The entrepreneur as hero and jester: Enacting the entrepreneurial discourse. Int. Small Bus. J. 2011, 29, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, K.M. Corporate Moral Responsibility vs. Corporate Social Responsibility: Friedman was Right. J. Bus. Ethics 2025, Online first, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrempf-Stirling, J.; Palazzo, G. Upstream corporate social responsibility: The evolution from contract responsibility to full producer responsibility. Bus. Soc. 2016, 55, 491–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. The metaphorical structure of the human conceptual system. Cogn. Sci. 1980, 4, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, L.; Anderson, A.R. News and nuances of the entrepreneurial myth and metaphor: Linguistic games in entrepreneurial sense–making and sense–giving. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.; Holt, R. Imagery of ad-venture: Drawing out metaphors of the entrepreneurship process. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2016, 2016, 13815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.D.; Hamilton, E.; Jack, S.L. Understanding entrepreneurial opportunities through metaphors: A narrative approach to theorizing family entrepreneurship. In Families in Business: The Next Generation of Family Evolution; Randerson, K., Frank, H., Dibrell, C., Memili, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 30–51. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, T.; Tian, Y. Social and symbolic capital and responsible entrepreneurship: An empirical investigation of SME narratives. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, S.; Tran, M.D. Doing Well and Being Responsible: The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Legitimacy on Responsible Entrepreneurship. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 1794–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmat, F.; Samaratunge, R. Responsible entrepreneurship in developing countries: Understanding the realities and complexities. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 90, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedula, S.; Doblinger, C.; Pacheco, D.; York, J.G.; Bacq, S.; Russo, M.V.; Dean, T.J. Entrepreneurship for the public good: A review, critique, and path forward for social and environmental entrepreneurship research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2022, 16, 391–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, K.; Corner, P.D.; Kearins, K. Social, environmental and sustainable entrepreneurship research: What is needed for sustainability-as-flourishing? Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Mauer, R.; Brettel, M. Regulatory focus theory and sustainable entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 408–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wu, Y. Doing Well and Doing Good: How Responsible Entrepreneurship Shapes Female Entrepreneurial Success. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 178, 803–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanda, C.; Toledano, N. The promotion of ethical entrepreneurship in the Third World: Exploring realities and complexities from an embedded perspective. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, D.; Lozano, J.M. SMEs and CSR: An approach to CSR in their own words. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Herrador-Alcaide, T.C.; Sánchez-Domínguez, J.C. Developing a measurement scale of corporate socially responsible entrepreneurship in sustainable management. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 18, 1377–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T.; Kaneko, S. The Sustainable Development Goals as new business norms: A survey experiment on stakeholder preferences. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 191, 107236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Zou, J. Selective engagement in corporate social responsibility: A stakeholder perspective. Front. Bus. Res. China 2015, 9, 371–399. [Google Scholar]

- Etter, M.; Ravasi, D.; Colleoni, E. Social media and the formation of organizational reputation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 28–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halme, M.; Korpela, M. Responsible innovation toward sustainable development in small and medium sized enterprises: A resource perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2014, 23, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemann, C.C.; Dickel, P.; Eckardt, G. The interplay of corporate entrepreneurship, environmental orientation, and performance in clean-tech firms—A double-edged sword. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manika, D.; Wells, V.K.; Gregory-Smith, D.; Gentry, M. The impact of individual attitudinal and organisational variables on workplace environmentally friendly behaviours. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 663–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G. Toward a political conception of corporate responsibility: Business and society seen from a Habermasian perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 1096–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, G.; Scherer, A.G. Corporate legitimacy as deliberation: A communicative framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 66, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanuth, A.; Urbano, D. Exploring social enterprise legitimacy within ecosystems from an institutional approach: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2024, 26, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanuth, A.; Urbano, D. Unseen heroes: How social enterprises facilitate legitimation of marginalized groups. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2025, 39, 94–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.; Gronewold, U.; Weiß, K. Using legitimacy strategies to secure organisational survival over time: The case of EFRAG. Account. Bus. Res. 2025, 55, 271–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achuthan, K.; Khobragade, S. Content dynamics and emotional engagement in online zero waste communities: A longitudinal study. Cities 2025, 165, 106119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.H.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.; Urbano, D. Socio-cultural factors and entrepreneurial activity: An overview. Int. Small Bus. J. 2011, 29, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Toledano, N.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. Socio-cultural factors and transnational entrepreneurship: A multiple case study in Spain. Int. Small Bus. J. 2011, 29, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano Pulido, D.; Toledano Garrido, N. Los proyectos innovadores en las PyMes españolas: Un estudio de casos múltiple. Econ. Ind. 2008, 368, 213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Toledano, N.; Urbano, D.; Rialp, A.; Bradshaw, M.V. Entrepreneurship policies: A multiple case study in a highly entrepreneurial Spanish region. In Entrepreneurship and Its Economic Significance, Behavior and Effects; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 41–53. ISBN 978-1-60692-669-7. [Google Scholar]

- Toledano, N.; Urbano, D. Políticas de apoyo a la creación de empresas en España. Un estudio de casos. Bol. ICE Econ. 2007, 2905, 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sandmann, L.; Bülbül, E.; Castano-Rosa, R.; Hanke, F.; Großmann, K.; Guyet, R.; Vornicu, A. The European Green Deal and its translation into action: Multilevel governance perspectives on just transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 115, 103659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de España. Law 11/2018 on Non-Financial Reporting and Diversity; Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2018; No. 314. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Ministry for Climate Action, Environment, Energy, Mobility, Innovation and Technology (Austria). Action Plan for Sustainable Public Procurement (naBe Action Plan, Updated 2021); Federal Ministry: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Prenzel, P.; Bosma, N.; Schutjens, V.; Stam, E. Cultural diversity and innovative entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2024, 63, 1381–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volintiru, C.; Surubaru, N.C.; Epstein, R.A.; Fagan, A. Re-evaluating the East-West divide in the European Union. J. Eur. Public Policy 2024, 31, 782–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q.; He, P.; Jiang, C. How and when does socially responsible HRM affect employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment? J. Bus. Ethics 2021, Online first, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, M.; Packendorff, J. Social constructionism and entrepreneurship: Basic assumptions and consequences for theory and research. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2009, 15, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.R.; Starnawska, M. Research practices in entrepreneurship: Problems of definition, description and meaning. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2008, 9, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyaert, C.; Katz, J. Reclaiming the space of entrepreneurship in society: Geographical, discursive and social dimensions. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2004, 16, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.R. The economic reification of entrepreneurship: Re-engaging with the social. In Rethinking Entrepreneurship: Debating Research Orientations; Fayolle, A., Riot, P., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; Chapter 4; pp. 44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Goss, D. Entrepreneurship and ‘the social’: Towards a deference-emotion theory. Hum. Relat. 2005, 58, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, D. Schumpeter’s legacy? Interaction and emotions in the sociology of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuogume, A.; Toledano, N. Co-creation in sustainable entrepreneurship education: Lessons from business–university educational partnerships. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledano, N.; Anderson, A.R. Theoretical reflections on narrative in action research. Action Res. 2020, 18, 302–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etter, M.; Colleoni, E.; Illia, L.; Meggiorin, K.; D’Eugenio, A. Measuring organizational legitimacy in social media: Assessing citizens’ judgments with sentiment analysis. Bus. Soc. 2018, 57, 60–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Crane, A. Corporate citizenship: Toward an extended theoretical conceptualization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolin-Lopez, R.; Martinez-del-Rio, J.; Cespedes-Lorente, J.J. Environmental entrepreneurship as a multi-component and dynamic construct: Duality of goals, environmental agency, and environmental value creation. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2019, 28, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Down, S.; Warren, L. Constructing narratives of enterprise: Clichés and entrepreneurial self-identity. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2008, 14, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, S.D.; Jack, S.; Anderson, A.R. From admiration to abhorrence: The contentious appeal of entrepreneurship across Europe. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2013, 25, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyaert, C.; Bouwen, R. Telling stories of entrepreneurship: Towards a narrative-contextual epistemology for entrepreneurial studies. In Entrepreneurship and SME Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Toledano, N.; Karanda, C. Morality, religious writings and entrepreneurship education: An integrative proposal using the example of Christian narratives. J. Moral Educ. 2017, 46, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neergaard, H. Sampling in entrepreneurial settings. In Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods in Entrepreneurship; Neergaard, H., Ulhoi, J.P., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2007; pp. 253–278. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. Sampling and generalization. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection; Flick, U., Ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2018; pp. 84–97. [Google Scholar]

- de Koning, A.; Dodd, S.D. Metaphors of entrepreneurship across cultures. J. Asia Entrep. Sustain. 2008, 4, 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, C.; Anderson, A. Visitor narratives: Researching and illuminating actual destination experience. Qual. Mark. Res. 2010, 13, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundin, E. Catching it as it happens. In Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods in Entrepreneurship; Neergaard, H., Ulhoi, J.P., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2007; pp. 279–300. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, S.D.; de Koning, A. Enacting, experimenting and exploring metaphor methodologies in entrepreneurship. In Handbook of Qualitative Research Techniques and Analysis in Entrepreneurship; Neergaard, H., Leitch, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 109–138. [Google Scholar]

- Steyaert, C. A qualitative methodology for process studies of entrepreneurship: Creating local knowledge through stories. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 1997, 27, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. Con ‘text’ualizing images of enterprise: An examination of ‘visual metaphors’ used to represent entrepreneurship in textbooks. In Handbook of Qualitative Research Techniques and Analysis in Entrepreneurship; Neergaard, H., Leitch, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 139–169. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rozmi, A.N.A.; Nohuddin, P.N.; Hadi, A.R.A.; Bakar, M.I.A. Identifying small and medium enterprise smart entrepreneurship training framework components using thematic analysis and expert review. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2021, 12, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürger, T.; Volkmann, C. Mapping and thematic analysis of cultural entrepreneurship research. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2020, 40, 192–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attribute | Manifestation | Distribution | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 40% | |

| Female | 60% | ||

| Age group | 18–25 | 47% | |

| 26–35 | 16% | ||

| 36–45 | 6% | ||

| 46–60 | 18% | ||

| 60+ | 13% | ||

| Country | Austria | 10% | |

| Czech Republic | 10% | ||

| Germany | 10% | ||

| Italy | 21% | ||

| Poland | 12% | ||

| Slovakia | 19% | ||

| Spain | 19% | ||

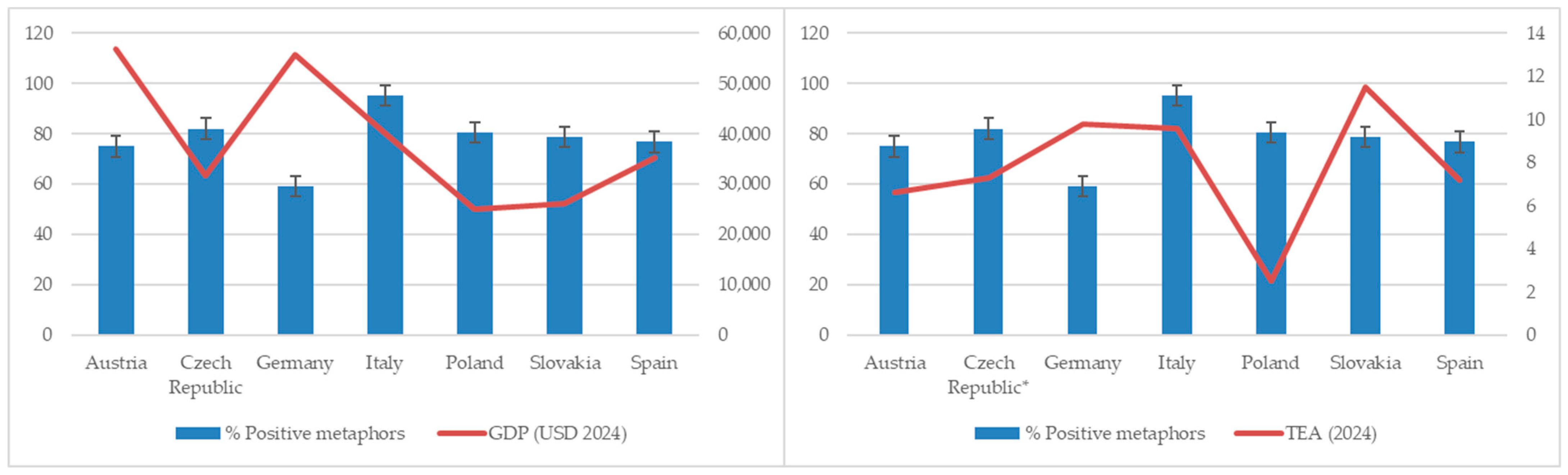

| Country | Nº Metaphors | % Positive Metaphors | % Neutral Metaphors | % Negative Metaphors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 28 | 75.00 | 10.71 | 10.71 |

| Czech Republic | 28 | 82.10 | 3.60 | 14.30 |

| Germany | 27 | 59.30 | 18.50 | 14.80 |

| Italy | 65 | 95.40 | 0.00 | 4.60 |

| Poland | 36 | 80.60 | 16.70 | 2.80 |

| Slovakia | 56 | 78.60 | 21.40 | 0.00 |

| Spain | 56 | 76.80 | 23.20 | 0.00 |

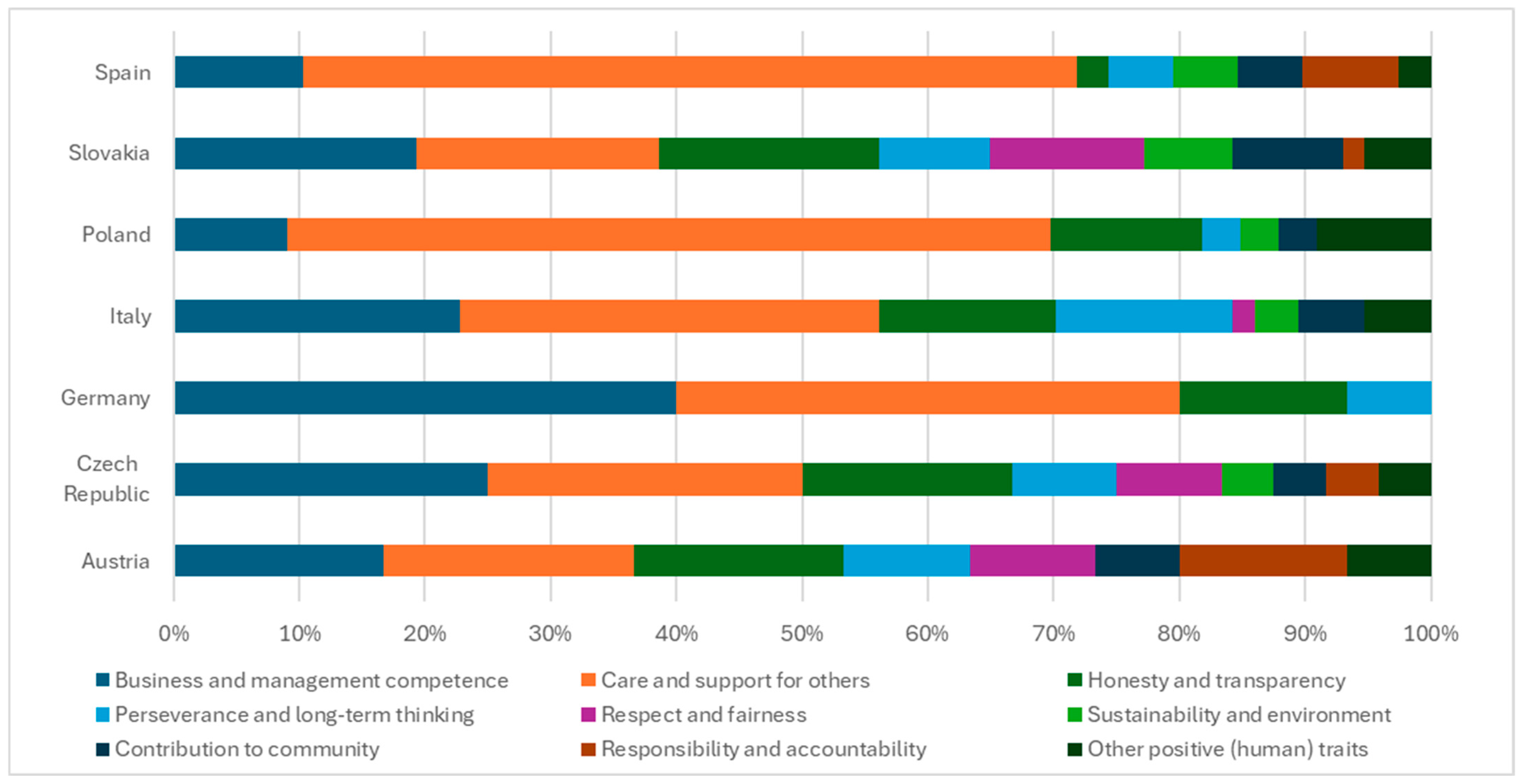

| Main Category | Examples of Responses | Mentions |

|---|---|---|

| Honesty and transparency | Acts with integrity, does not lie; is sincere; transparent with clients | 34 |

| Special care and support for others | Leads by examples; supports people with fewer resources; gives opportunities develops others | 92 |

| Respect and fairness | Respects employees; treats others fairly; does not exploit people | 13 |

| Responsibility and accountability | Takes responsibility; keeps promises, admits mistakes; is accountable | 9 |

| Contribution to community | Benefits society; creates values for the community | 14 |

| Sustainability and environment | Cares for the planet; uses ecological materials, protects nature | 10 |

| Perseverance and long-term thinking | Thinks about the future; doesn’t seek short-term gain; builds something lasting | 22 |

| Business and management competence | Values teamwork; solves problems creatively; understands well the economy; works hard without complaining; innovates responsibly | 48 |

| Other general positive (human) traits and values | Listens; is open to other opinions; adapts to change without losing their human values | 13 |

| Country | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Austria | I would buy eco-friendly products even if they are more expensive. |

| Czech Republic | I would support local and eco-conscious brands, even if it costs a bit more. |

| Germany | I would donate a small part of my salary to good causes. I would pay more as a consumer, taking into account the sustainable and environmentally friendly production of goods. |

| Italy | I would buy local products and products made in Italy. I would reduce comforts to support sustainable healthcare progress. |

| Poland | I would avoid unnecessary purchases and support local businesses more. |

| Slovakia | I’ve already cut personal spending to support social causes. I’m restructuring my business to minimize its environmental impact. |

| Spain | I would stop buying from big companies that don’t care about the environment and I would buy local or sustainable products even if they are more expensive. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Toledano, N.; Horie, T. Responsible Entrepreneurship Through Public Eyes: A Qualitative Exploration of Moral and Sustainable Expectations. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7874. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177874

Toledano N, Horie T. Responsible Entrepreneurship Through Public Eyes: A Qualitative Exploration of Moral and Sustainable Expectations. Sustainability. 2025; 17(17):7874. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177874

Chicago/Turabian StyleToledano, Nuria, and Tetsuya Horie. 2025. "Responsible Entrepreneurship Through Public Eyes: A Qualitative Exploration of Moral and Sustainable Expectations" Sustainability 17, no. 17: 7874. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177874

APA StyleToledano, N., & Horie, T. (2025). Responsible Entrepreneurship Through Public Eyes: A Qualitative Exploration of Moral and Sustainable Expectations. Sustainability, 17(17), 7874. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177874