Sensory Heritage Is Vital for Sustainable Cities: A Case Study of Soundscape and Smellscape at Wong Tai Sin

Abstract

1. Introduction

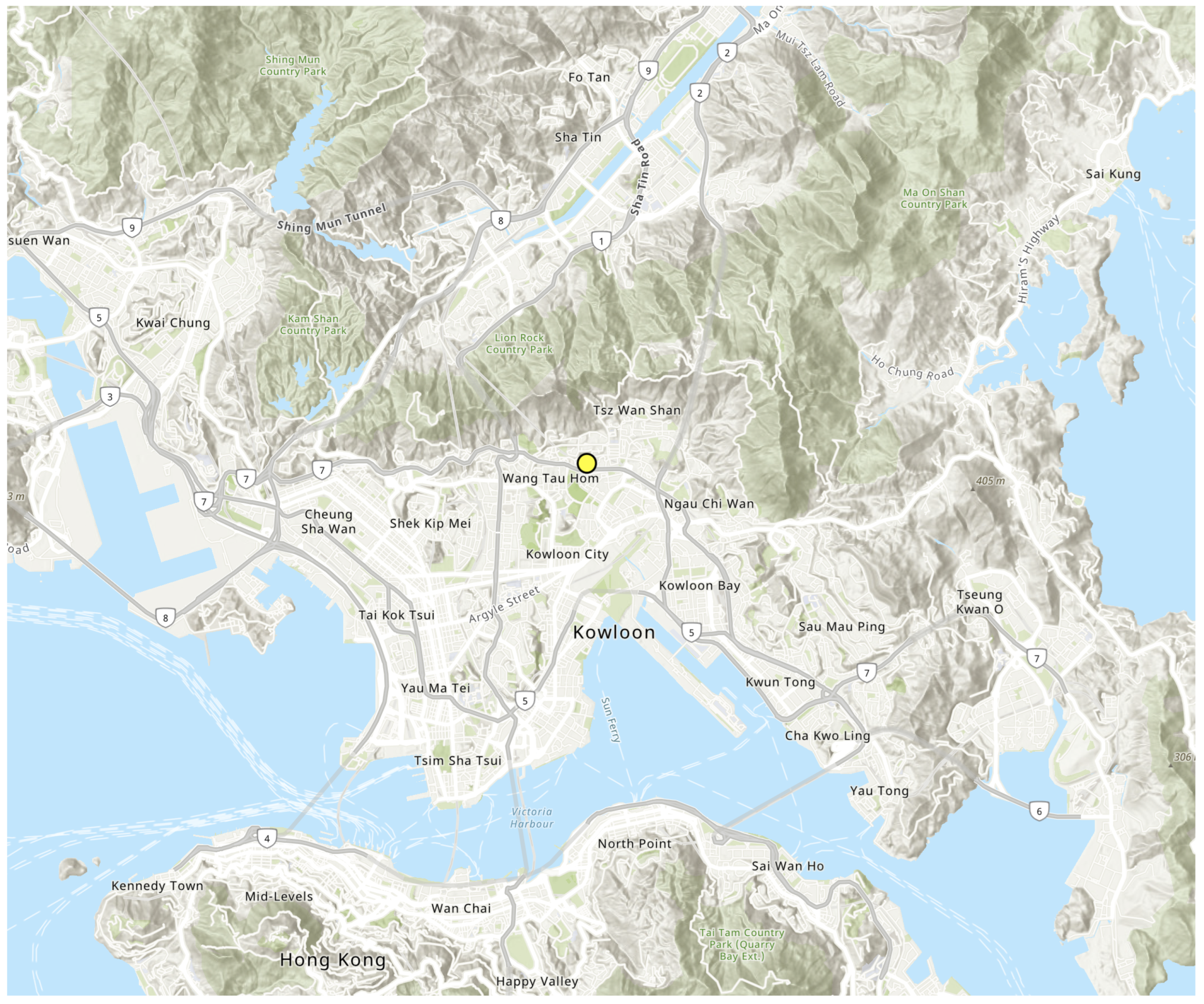

1.1. Context

1.2. Site Characteristics

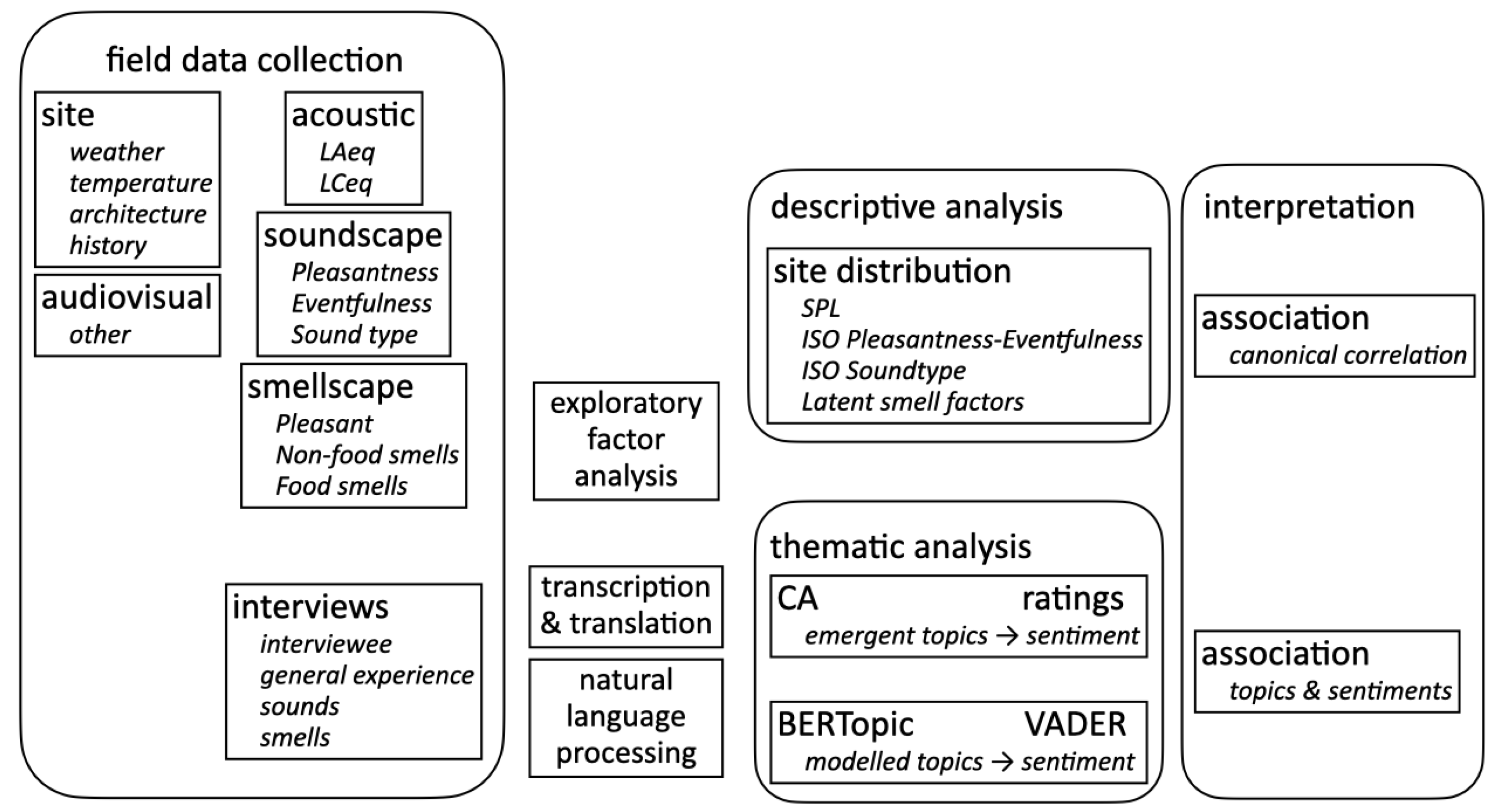

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Data Collection

2.2. Acoustic Measures

2.3. Soundscape Ratings

2.4. Smellscape Ratings

2.5. Interviews

2.6. Analysis and Topic Modelling

3. Analysis and Results—Field Data

3.1. Imputing Data

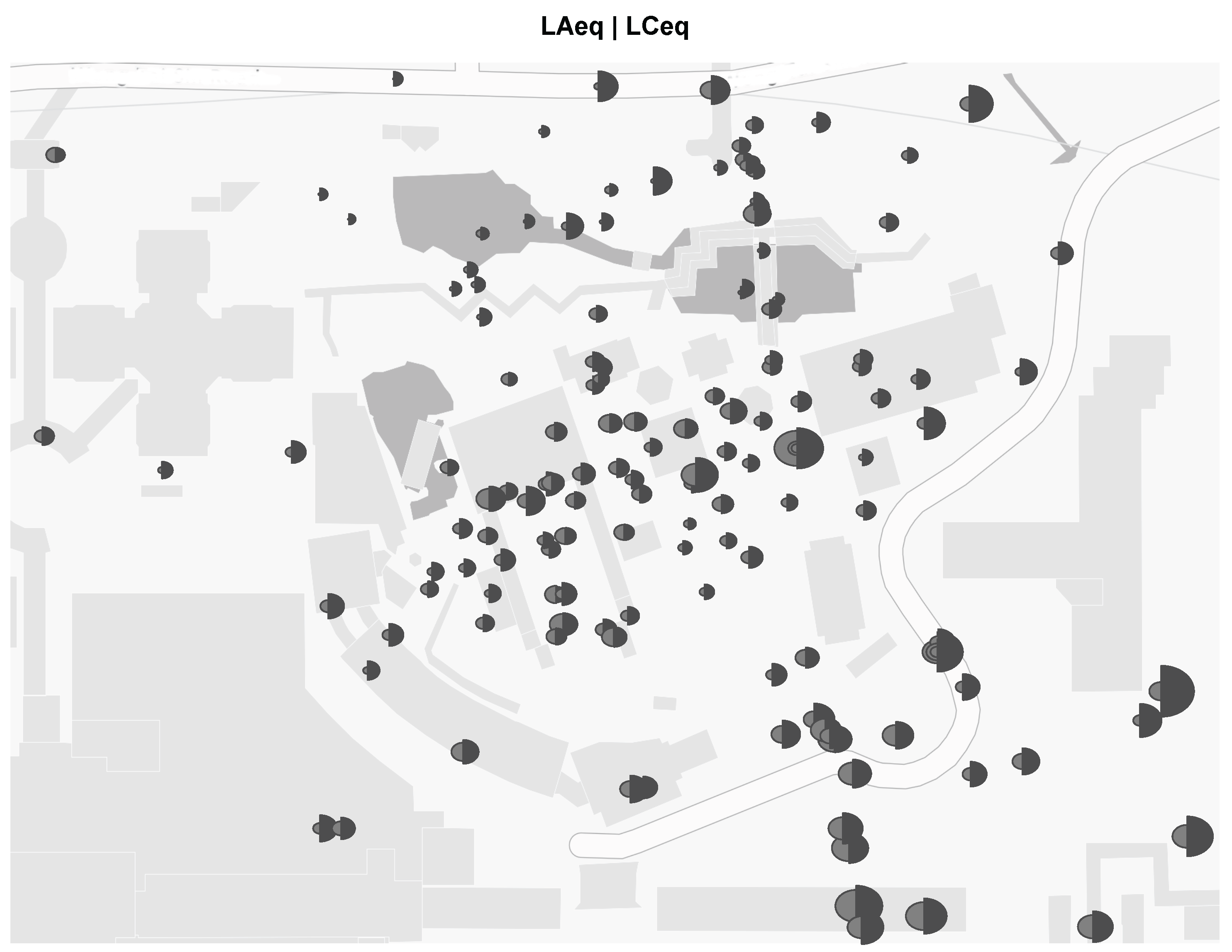

3.2. Acoustic Measures

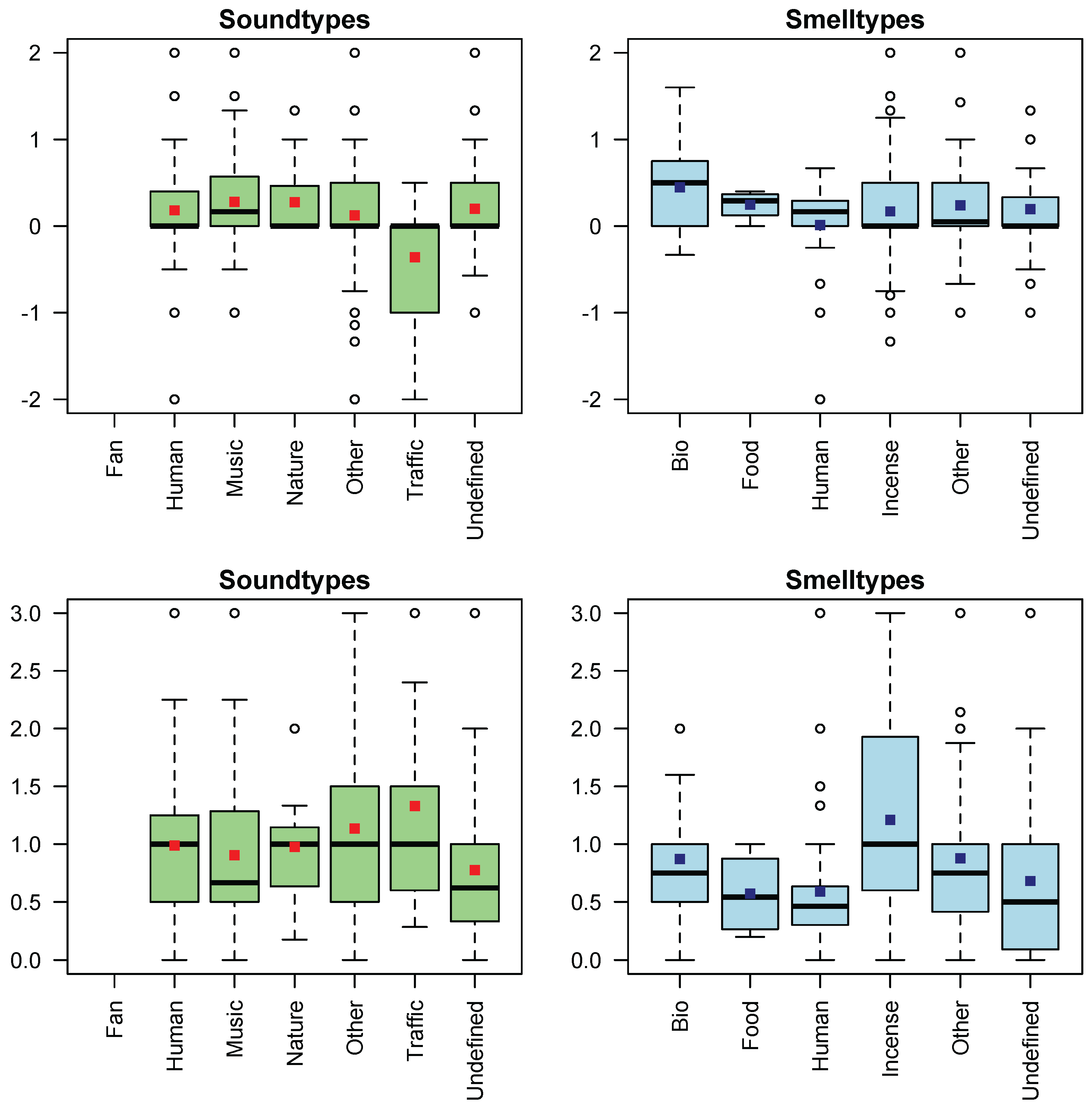

3.3. Soundscape Ratings

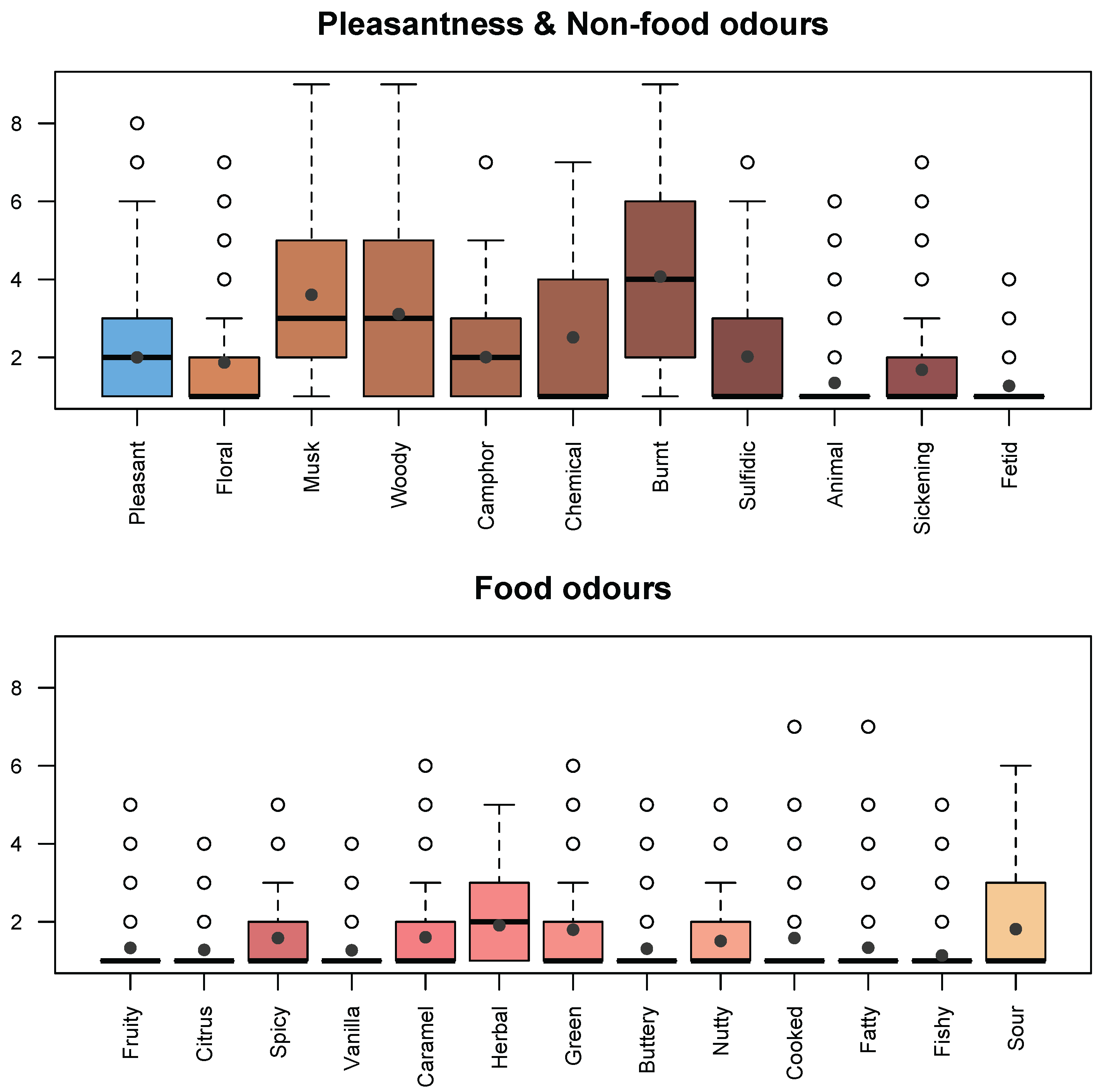

3.4. Smellscape Ratings

3.5. Canonical Correlation Analysis

4. Analysis and Results—Interviews

4.1. Thematic Analysis

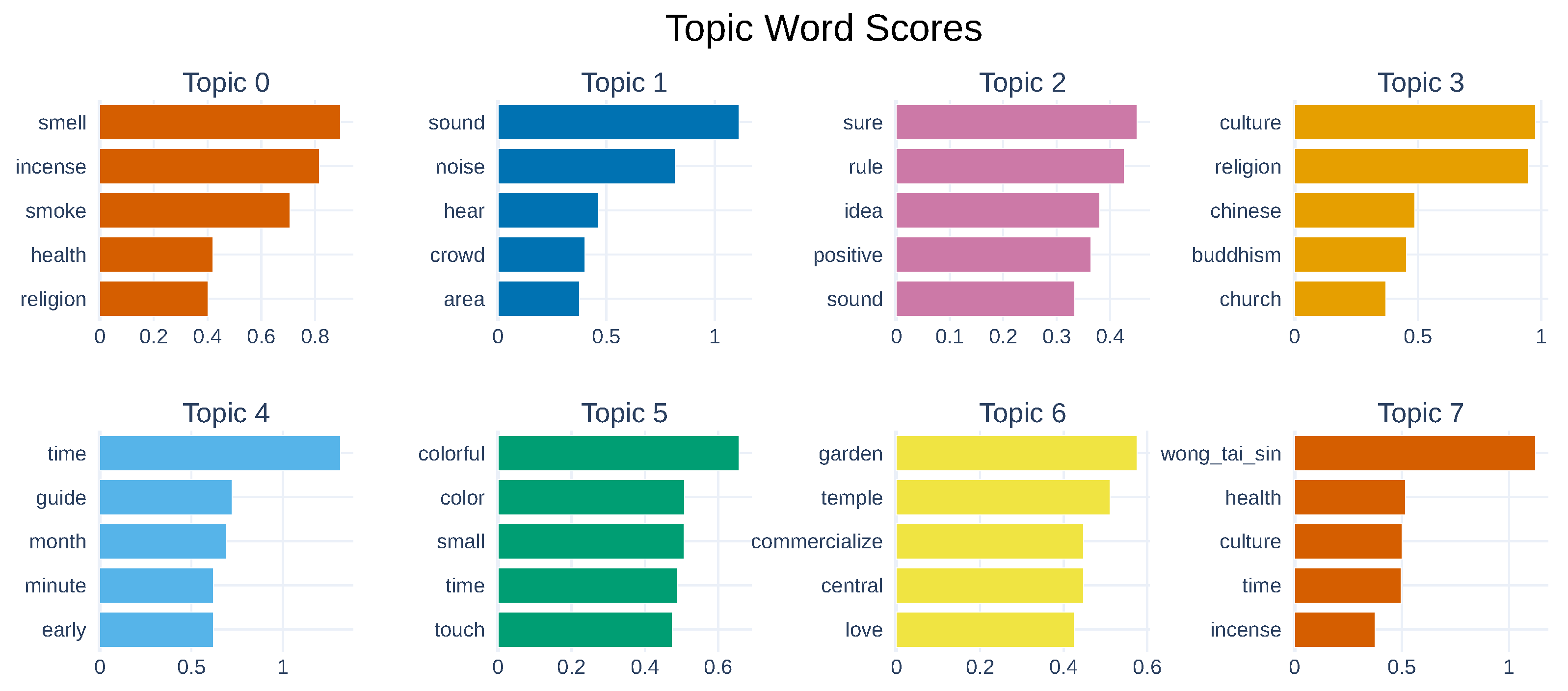

4.1.1. Topic Modelling

Sentence transformer (‘all-MiniLM-L6-v2’) +

Vectorizer (stop_words = “english”, ngram_range = (1, 2), min_df = 3) +

PartOfSpeech (‘en_core_web_sm’, stopword removal) +

UMAP (n_neighbors = 10, n_components = 5, min_dist = 0.01, metric = ‘cosine’) +

HDBSCAN (min_cluster_size = 20, min_samples = 5, metric = ‘euclidean’, cluster_selection_method = ‘eom’) +

TF-IDF (seed_words = [‘sound’, ‘music’, ‘noise’, ‘smell’, ‘incense’, ‘smoke’, ‘time’, ‘culture’, ‘religion’, ‘health’, ‘hong_kong’, ‘wong_tai_sin’], seed_multiplier = 2)

4.1.2. Content Analysis

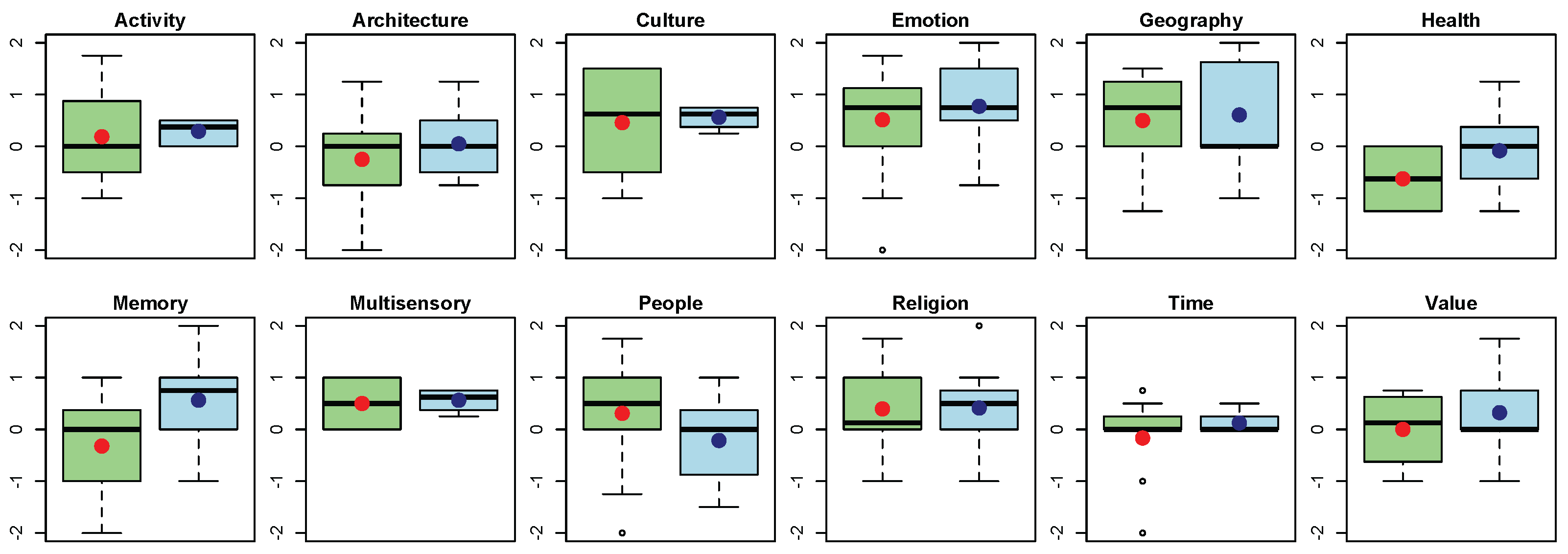

4.2. Sentiment Analysis

4.2.1. Computational Sentiment Analysis

“Yes, many come with happy or positive intentions. They ask for safety or success in their endeavors. And sometimes, people come just to give thanks. It’s usually a peaceful and uplifting experience.”(Mainland Chinese guide, speaking Mandarin, male 35 years old, YR.5.31)

“Yeah. Maybe I think because I have been also in China. In China, I didn’t feel so much about religion or things like Chinese people are not. So in going in, not that they don’t believe or anything. I don’t know about that. I didn’t discuss it very profoundly with them, but they are not going so much in temples that I saw as example in Sri Lanka or here. But in Hong Kong, I feel like there is a lot and a lot of people coming into the temple or even Like honoring their gods.”(French tourist, speaking English, female 30 years old, PM.8.48)

“Yes, I think the scent brings back a lot of memories. For me, the smell of incense doesn’t specifically remind me of my grandmother because we didn’t have this kind of scent at home. But I do think that the act of burning incense is deeply connected to religious faith—it’s very ingrained. You rarely hear of people burning incense who are Christians. Usually, those who do it believe in Guanyin, Buddha, or other deities from Buddhism or Taoism. So this act makes me think of certain religious concepts. This connection is related to my own memories and even shapes my perception of the practice. Of course, different religions have their own rituals—for example, Christians have Mass, while Buddhists and Taoists have their respective customs. To me, every religious ritual or symbol carries a specific meaning. As for the scent, the smell of incense evokes religious thoughts for me. It might remind me of the setting for worship or even create a kind of spiritual feeling.”(Chinese tourist, male 30 years old, Yui.4.10)

“The music they play? They play some music here. It’s a bit of music, yes. Some people find it very calming. It’s not like they’re playing something like golden sounds or anything. In some places, they focus on playing golden sounds.”(Local volunteer, speaking Mandarin, male 55 years old, YR.9.60)

4.2.2. Interpretative Sentiment Analysis

4.3. Association Between Topics

4.4. Summary of Interview Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Translating Key Terms

“For me, the [氣氛] here is very positive, especially the feeling that burning incense brings—it’s uplifting. Of course, as mentioned earlier, environmental concerns might be an issue, and I acknowledge that. However, I believe a city needs a mix of cultures. It can’t just be skyscrapers; it also needs cultural depth. As long as these practices are manageable, I think they are acceptable.”(Mainland Chinese tourist, speaking Mandarin, male 40 years old, Yui.3.4)

“Well, Wong Tai Sin Temple isn’t entirely within a residential area; there’s some distance. From where I am, I can’t really hear the temple sounds. As for the electronic music you mentioned, I think it helps create [氣氛], which is very important. In the past, there might have been live chanting or drumbeats, which added a traditional feel to the temple. Even with the switch to electronic music, as long as it maintains that ambiance, it can still convey the temple’s cultural and spiritual essence.”(same as above, Yui.3.8)

5.2. Sounds of Nature and Music

“For Wong Tai Sin, the sound I remember most distinctly is the sound of birds. Since I live nearby, there are bird nests in the area. Although there are fewer trees now, I used to hear birds chirping all the time, especially around the trees. The birds’ calls are a signature sound of this place for me. Apart from that, the bustling noise when I walk here also makes me feel the vibrancy [活力] of this area, which is part of Wong Tai Sin’s unique atmosphere [氛圍]. Birds’ calls are quite sharp, but for me, they represent nature and comfort—they’re a natural sound. Human voices or other artificial sounds give off a different feeling—they might feel noisy or stressful. For me, there’s a clear distinction between natural and artificial sounds, and this distinction shapes how I feel about them.”(Local tourist, speaking Cantonese, male 30 years old, Yui.4.12)

“I think human voices and music can mix naturally. That’s why this place feels special—because like you said, the musical instruments and people’s voices mix here. It creates a “third sound”. The first sound is the instrument. The second is people’s voices. When combined, they create something new. It becomes a unique sound, something entirely different.”(Korean tourist, speaking English, male 27 years old, YR.6.20)

“I actually like the music too. I don’t really like the loud noise, but the music is very nice. The music is also very unique and beautiful. It’s very Chinese. It’s actually hard to describe. It’s my first time experiencing this. It’s all very new and amazing. I’ve never experienced anything like this before. But everything is so beautiful and new to me.”(Mainland Chinese tourist, speaking Mandarin, female 25 years old, YR.1.19)

5.3. Soundscape and Emotion

“Oh, the people are so kind here. There are also a lot of tourists. So yeah, everyone’s really nice. I actually like the music too. I don’t really like the loud noise, but the music is very nice. The music is also very unique and beautiful. It’s very Chinese. It’s actually hard to describe. It’s my first time experiencing this. It’s all very new and amazing. I’ve never experienced anything like this before. But everything is so beautiful and new to me.”(Ukrainian tourist, speaking English, female 25 years old, YR.2.19)

“I’m used to it, used to it. In Hong Kong, everything is like this, full of food stalls. There are so many, I’m used to it. Compared to the mainland, there are some places … In rural areas, it’s quieter, with fewer cars. But here, it’s all about food and noise. It’s much louder here. Everything here is about food. It’s nothing, really. I hope for good health.”(Local incense seller, speaking Mandarin, female 55 years old, YR.3.42)

“Yes, I think the scent brings back a lot of memories. For me, the smell of incense doesn’t specifically remind me of my grandmother because we didn’t have this kind of scent at home. But I do think that the act of burning incense is deeply connected to religious faith—it’s very ingrained. You rarely hear of people burning incense who are Christians. Usually, those who do it believe in Guanyin, Buddha, or other deities from Buddhism or Taoism. So this act makes me think of certain religious concepts. This connection is related to my own memories and even shapes my perception of the practice. Of course, different religions have their own rituals—for example, Christians have Mass, while Buddhists and Taoists have their respective customs. To me, every religious ritual or symbol carries a specific meaning. As for the scent, the smell of incense evokes religious thoughts for me. It might remind me of the setting for worship or even create a kind of spiritual feeling.”(Chinese tourist, speaking Cantonese, male 30 years old, Yui.4.10)

5.4. People

“Yes, these [cultural heritage activities, like bell ringing and incense burning. They’re part of traditional culture] are good things. To preserve them, people need to keep participating. Doing good deeds, la! Worshiping has its own meaning, like the saying, ‘The more you worship, the more good things will happen.’ It’s true. Seeing elderly people—like those 90-year-old grannies—coming daily with their spouses to worship is so moving. Their spirits are so high!”(Local Cantonese Street hawker, female 47 years old, Yui.1.26)

5.5. The Smell of Religion

“I feel that Wong Tai Sin (Temple) has the most incense smoke on the first day of the Lunar New Year [頭炷香], when (people) come to offer the first incense. Personally, I’ve been to Wong Tai Sin (Temple) less than five times. My understanding of Wong Tai Sin (Temple) is that my parents’ generation would come here to draw divination sticks and pray for good fortune in the coming year.”(Mainland Chinese tourist, speaking Cantonese, male 65 years old, RL.1.13)

“I agree. They do a lot of good things. Although selling incense may involve money, there are also free services. For example, they offer free Chinese medicine to the elderly. I’ve heard about these from others, and they are good things. But if you’re a tourist, coming here for the experience, it’s nice. Since Hong Kong is a tourist destination, Wong Tai Sin isn’t bad. But if tourism is the main focus, perhaps there should be more emphasis on traditional culture, like sharing Wong Tai Sin’s history and culture.”(Local Housing Authority security staff, speaking Cantonese, female 40 years old, Yui.5.20)

“I go there when I need peace, or when things aren’t going well. It’s a place for spiritual renewal.”(Chinese Mainland guide, speaking Mandarin, male 35 years old, YR.5.35)

“It’s like the commercialization of everything—people chose to make it a business. Some places seem to have turned into business hubs, losing their pure religious atmosphere.”(Local Housing Authority security staff, speaking Cantonese, female 40 years old, Yui.5.16)

5.6. Identity

“Hong Kong is a place where people from everywhere gather. All kinds of people.”(Ukrainian tourist, speaking English, female 25 years old, YR.2.6)

“I don’t strictly follow any one faith. But I respect various beliefs, like Buddhism and Taoism. For example, I’m not specifically devoted to Wong Tai Sin, but I respect his teachings. Wong Tai Sin is a Taoist deity, but the temple also incorporates aspects of Buddhism.”(Local incense seller, speaking Mandarin, female 55 years old, YR.3.14)

5.7. Future Prospects

5.8. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lenzi, S.; Sádaba, J.; Lindborg, P. Soundscape in Times of Change: Case Study of a City Neighbourhood During the COVID-19 Lockdown. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 570741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classen, C.; Howes, D.; Synnott, A. Aroma: The Cultural History of Smell; Taylor & Francis e-Library: Abingdon, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Augé, M. Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity; Verso: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bembibre, C. Olfactory heritage: Opportunities for policymaking. In Sensory Dimensions in Heritage and Beyond: Exploring Soundscapes and Smellscapes; Multimodal Hong Kong: Hong Kong, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R.; Bond, J. Sensory perception in cultural studies—A review of sensorial and multisensorial heritage. Senses Soc. 2023, 19, 231–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ppali, S.; Pasia, M.; Wolf, S.; Han, J.; Muntean, R.; Yoo, M.; Rodil, K.; Berger, A.; Papallas, A.; Ciolfi, L.; et al. Sensing Heritage: Exploring Creative Approaches for Capturing, Experiencing and Safeguarding the Sensorial Aspects of Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the Companion Publication of the 2024 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference. Association for Computing Machinery, DIS ’24 Companion, Funchal, Portugal, 1–5 July 2024; pp. 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Tao, Y.; Smith, B. China’s emerging legislative and policy framework for safeguarding intangible cultural heritage. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2021, 28, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. The World Heritage Convention: Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage; Secretariat of the United Nations: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. International Round Table on ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage—Final Report’; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lindborg, P.; Lam, L.; Kam, Y.; Xiao, J. Developing Sensory Heritage Policy from International Soundscape and Smellscape Standards. In Proceedings of the Forum Acousticum-Euronoise, 11th Convention of the European Acoustics Association, Málaga, Spain, 23–26 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Caust, J.; Vecco, M. Is UNESCO World Heritage recognition a blessing or burden? Evidence from developing Asian countries. J. Cult. Herit. 2017, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindborg, P.; Aletta, F.; Xiao, J.; Liew, K.; Matsuda, Y.; Yue, R.; Jiang, Q.; Lam, L.H.; Wei, L. Multimodal Hong Kong: Documenting soundscape and smellscape at places of intangible cultural heritage. In Proceedings of the 53rd International Congress & Exposition on Noise Control Engineering (INTER-NOISE 2024), Nantes, France, 25–29 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fırat, H.B. Acoustics as Tangible Heritage: Re-embodying the Sensory Heritage in the Boundless Reign of Sight. Preserv. Digit. Technol. Cult. 2021, 50, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindborg, P. Sound Perception and Design in Multimodal Environments. Ph.D. Thesis, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, C. Using Ambient Scent to Enhance Well-Being in the Multisensory Built Environment. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 598859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindborg, P.; Liew, K. Real and Imagined Smellscapes. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 718172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrot, G.; Brochet, F.; Dubourdieu, D. The color of odors. Brain Lang. 2001, 79, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, R.S. Odor-Evoked Memory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 265–275. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, A.; Vosshall, L.B. Human olfactory psychophysics. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, R875–R878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, B.D. Olfactory imagery: Is exactly what it smells like. Philos. Stud. 2020, 177, 3303–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Lindborg, P. Spatializing Sensory Memories: Reflections from an experimental workshop on recalled sounds and smells. In The Senses and Memory, Vernon Press; Dupuis, C., Ed.; Vernon Press: Wilmington, DE, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- 12913-1: 2014; Acoustics—Soundscape—Part 1: Definition and Conceptual Framework. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Porteous, J.D. Smellscape. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 1985, 9, 356–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henshaw, V. Urban Smellscapes: Understanding and Designing City Smell Environments; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J. Smell, smellscape, and place-making: A review of approaches to study smellscape. In Handbook of Research on Perception-Driven Approaches to Urban Assessment and Design; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 240–258. [Google Scholar]

- AFP. France Passes ‘Sensory Heritage’ Law After Plight of Maurice the Noisy Rooster; AFP: Canberra, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Morel-à-L’Huissier, P. [Rapport] Visant à Définir et Protéger le Patrimoine Sensoriel des Campagnes Françaises. Available online: https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/dyn/15/rapports/cion-cedu/l15b2618_rapport-fond.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- Hong Kong Legislative Council. Chinese Temples Ordinance (Cap. 153). 1997. Available online: https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap153 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Cai, W.H.; Wong, P.P.Y. Associations between incense-burning temples and respiratory mortality in Hong Kong. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.H.; Lindborg, P.; Aletta, F.; Wong, P.P.Y.; Yue, R. Multimodal Hong Kong: A review of policies regarding soundscape and smellscape of Chinese temples. In Proceedings of the 53rd International Congress & Exposition on Noise Control Engineering (INTER-NOISE 2024), Nantes, France, 25–29 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.s. A nameless but active religion: An anthropologist’s view of local religion in Hong Kong and Macau. China Q. 2003, 174, 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antiquities and Monuments Office, Hong Kong SAR Government. Wong Tai Sin Temple Historic Building Appraisal; Antiquities and Monuments Office, Hong Kong SAR Government: Hong Kong, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Lee, S.C.; Ho, K.F.; Kang, Y.M. Characteristics of emissions of air pollutants from burning of incense in temples, Hong Kong. Sci. Total Environ. 2007, 377, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T. “Gods Feast on Holy Smoke, Not Tear Gas!” Religious Diffusion, Infrapolitics, and Identity Formation in Hong Kong. J. Asian Stud. 2024, 83, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sik Sik Yuen. Intangible Cultural Heritage Affairs of WTS Beliefs and Customs; Sik Sik Yuen: Hong Kong, China, 2025; Available online: https://www2.siksikyuen.org.hk/en/cultural-affairs/intangible-cultural-heritage-affairs-of-wong-tai-sin-beliefs-and-customs (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Mitchell, A.; Oberman, T.; Aletta, F.; Erfanian, M.; Kachlicka, M.; Lionello, M.; Kang, J. The Soundscape Indices (SSID) Protocol: A Method for Urban Soundscape Surveys—Questionnaires with Acoustical and Contextual Information. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindborg, P.; Friberg, A. Personality traits bias the perceived quality of sonic environments. Appl. Sci. 2016, 6, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, R.; Lindborg, P.; Lam, L.H.; Lin, A.; Kam, Y. Sunday Soundscapes: Foreign Domestic Helpers’ Acoustic Contributions to Hong Kong’s Public Spaces. In Proceedings of the Forum Acousticum-Euronoise, 11th Convention of the European Acoustics Association, Málaga, Spain, 23–26 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- 12913-2: 2018; Acoustics—Soundscape—Part 2: Data Collection and Reporting Requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Axelsson, O.; Nilsson, M.E.; Berglund, B. A principal components model of soundscape perception. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2010, 128, 2836–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aletta, F.; Mitchell, A.; Oberman, T.; Kang, J.; Khelil, S.; Bouzir, T.A.K.; Berkouk, D.; Xie, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; et al. Soundscape descriptors in eighteen languages: Translation and validation through listening experiments. Appl. Acoust. 2024, 224, 110109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinley, C.M.; McGinley, M.A. Odor testing biosolids for decision making. Proc. Water Environ. Fed. 2002, 2002, 1055–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzo, M. Multivariate Analysis and Classification of 146 Odor Character Descriptors. Chemosens. Percept. 2021, 14, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dravnieks, A.; Bock, F.; Powers, J.; Tibbetts, M.; Ford, M. Comparison of odors directly and through profiling. Chem. Senses 1978, 3, 191–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dravnieks, A.; Masurat, T.; Lamm, R.A. Hedonics of odors and odor descriptors. J. Air Pollut. Control Assoc. 1984, 34, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgiorno, V.; Naddeo, V.; Zarra, T. Odour Impact Assessment Handbook; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Doty, R.L.; Shaman, P.; Kimmelman, C.P.; Dann, M.S. University of pennsylvania smell identification test: A rapid quantitative olfactory function test for the clinic. Laryngoscope 1984, 94, 176–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprague, N.L.; Fan, I.B.; Dandeneau, M.; Hernandez Perez, J.F.; Birmingham, J.; De Los Santos, D.; Riddick, M.I.; Meltzer, G.Y.; Siegel, E.L.; Hernández, D. StreetTalk: Exploring energy insecurity in New York City using a novel street intercept interview and social media dissemination method. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. Episodic Interviewing; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2000; pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M.W.; Gaskell, G. Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound: A Practical Handbook for Social Research; SAGE: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Grootendorst, M. BERTopic: Neural topic modeling with a class-based TF-IDF procedure. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.05794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong Kong Observatory. Hong Kong Observatory Open Data; Hong Kong Observatory: Hong Kong, China, 2025. Available online: https://www.hko.gov.hk/en/abouthko/opendata_intro.htm (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department. Available online: https://hked.epd.gov.hk/ (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- To, W.M.; Mak, C.M.; Chung, W.L. Are the noise levels acceptable in a built environment like Hong Kong? Noise Health 2015, 17, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong Kong Legislative Council. Noise Control Ordinance (Cap. 400). 1989. Available online: https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap400 (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Directive 2002/49/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 June 2002 Relating to the Assessment and Management of Environmental Noise—Declaration by the Commission in the Conciliation Committee on the Directive Relating to the Assessment and Management of Environmental Noise; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2002.

- Peeters, H.M.; Nusselder, R.J. Quiet Areas, Soundscaping and Urban Sound Planning; European Network of the Heads of Environment Protection Agencies: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12913-3: 2019; Acoustics—Soundscape—Part 3: Data Analysis. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Thompson, B. Canonical correlation analysis. In Reading and Understanding More Multivariate Statistics; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 285–316. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; Version 4.4.0; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Michalke, M.; Brown, E.; Mirisola, A.; Brulet, A.; Hauser, L. KoRpus (Package for R); v0.13-8; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1802.03426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malzer, C.; Baum, M. A hybrid approach to hierarchical density-based cluster selection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Multisensor Fusion and Integration for Intelligent Systems (MFI), Karlsruhe, Germany, 14–16 September 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.10084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Hutto, C.; Gilbert, E. Vader: A parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1–4 June 2014; Volume 8, pp. 216–225. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, P. Traité des Objets Musicaux: Essai Interdiscipines; Ouvrage Publique. Avec le concours du service de la recherche de L’ORTF; Éditions du Seuil: Paris, France, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Space and Place: Humanistic Perspective. In Philosophy in Geography; Theory and Decision Library; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1977; Volume 20, pp. 387–427. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, L.H.; Yue, R.; Kam, Y.; Lindborg, P. Perceptions of Chinese Temples through Soundscape and Smellscape: A Case Study at Wong Tai Sin. In Proceedings of the Forum Acousticum-Euronoise, 11th Convention of the European Acoustics Association, Málaga, Spain, 23–26 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Blueprint for Hong Kong’s Tourism Industry 2.0. Available online: https://www.cstb.gov.hk/file_manager/en/documents/consultation-and-publications/Tourism_Blueprint_2.0_English.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Yahoo Finance Virtual Tourism Industry Eyes $31.6 Billion Opportunity by 2030-Increased Use of VR in Destination Marketing Creates Opportunities for Tourism Operators. Available online: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/virtual-tourism-industry-eyes-31-111200440.html (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Intangible Cultural Heritage Office. Hong Kong Week 2023@Bangkok. Available online: https://www.icho.hk/en/web/icho/hongkongweek_2023.html (accessed on 13 June 2025).

| Type | Variable | Mean | Median | Low Quartile | High Quartile | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acoustic | 65.3 | 65.15 | 63.2 | 67.1 | dBA, 1 min. | |

| 74.33 | 73.2 | 71.8 | 77.1 | dBC, 1 min. | ||

| Soundscape | Pleasantness | 0.01 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 | −1–+1 |

| Eventfulness | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.09 | 0.13 | −1–+1 | |

| Humans | 4.9 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 | scale 1–9 | |

| Nature | 2.86 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | scale 1–9 | |

| Traffic | 3.59 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 6.0 | scale 1–9 | |

| Fan | 2.25 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | scale 1–9 | |

| Other | 4.88 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 7.0 | scale 1–9 | |

| Smellscape | Pleasant | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | scale 1–9 |

| FA1. Off-putting/chemical | 0.0 | −0.27 | −0.71 | 0.52 | latent factor | |

| FA2. Incense | 0.0 | −0.16 | −0.77 | 0.59 | latent factor | |

| FA3. Grassy | 0.0 | −0.11 | −0.68 | 0.54 | latent factor |

| Topic | Statements | Words | Proportion | Nouns | Examples (Nouns) | Adjectives | Examples (Adjectives) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soundscape | 125 | 2833 | 13.50% | 598 | sound (58), music (44), people (28), temple (20), atmosphere (13), place (13), bell (12), chant (12), noise (9), lot (8), play (8), traffic (8), area (7), bird (7), bite (7), day (7), yes (7), car (5), crowd (5), drum (5), instrument (5), part (5), thing (5), time (5), tourist (5), use (5), voice (5) | 279 | noisy (12), sound (12), much (11), many (9), nice (9), quiet (9), electronic (8), other (7), traditional (7), different (6), okay (6), chinese (5), good (5), loud (5), peaceful (5) |

| Smellscape | 137 | 3472 | 16.50% | 701 | incense (107), smell (72), people (26), temple (22), smoke (17), burn (15), kind (13), scent (13), yes (12), lot (11), stick (10), air (8), bite (8), pollution (8), city (7), nothing (7), place (7), feel (6), sense (6), time (6), environment (5), issue (5), part (5), something (5), use (5) | 312 | good (19), strong (15), much (14), different (12), pleasant (12), other (9), smokeless (9), special (9), little (8), many (7), environmental (6), okay (6), unpleasant (6), traditional (5) |

| Emotion | 103 | 1820 | 8.70% | 328 | people (20), smell (19), incense (15), temple (13), music (12), peace (12), sound (12), experience (10), place (10), bite (8), feel (7), anything (6), sense (6), yes (6), crowd (5), lot (5) | 180 | peaceful (13), nice (10), much (8), pleasant (8), different (7), good (6), sound (6), unpleasant (5) |

| Religion | 102 | 2884 | 13.70% | 611 | temple (43), people (32), incense (27), religion (12), something (12), wong_tai_sin (11), yes (11), culture (10), god (10), kind (10), thing (10), lot (9), buddhist (8), church (8), place (8), smell (8), atmosphere (7), buddha (7), buddhism (7), experience (7), time (7), support (6), worship (6), … (5), burn (5), city (5), faith (5) | 224 | good (15), much (13), spiritual (12), different (11), other (8), religious (8), many (7) |

| Activity | 60 | 1491 | 7.10% | 309 | time (17), dollar (12), people (12), stick (12), incense (11), temple (9), place (6), bundle (5), kind (5), something (5), wish (5), yes (5) | 73 | other (6) |

| Value | 57 | 1556 | 7.40% | 307 | people (24), incense (18), temple (14), place (8), thing (8), time (8), wong_tai_sin (7), money (6), everyone (5), lot (5) | 151 | good (21), many (7), much (6), other (6), smokeless (6) |

| People | 48 | 975 | 4.60% | 187 | people (40), lot (11), temple (10), place (8), crowd (6), sound (6) | 100 | many (13), good (12), much (6) |

| Time | 44 | 924 | 4.40% | 184 | time (15), temple (11), incense (8), year (8), atmosphere (6), people (6), yes (6), day (5), place (5), wong_tai_sin (5) | 83 | first (9), different (8) |

| Geography | 41 | 1215 | 5.80% | 213 | temple (19), people (11), china (6), time (6), church (5) | 94 | different (9), mainland (6), other (5), similar (5) |

| Architecture | 38 | 844 | 4.00% | 156 | temple (13), place (7), incense (5), people (5) | 88 | different (6), beautiful (5), nice (5), same (5) |

| Memory | 33 | 1328 | 6.30% | 263 | incense (14), people (11), place (9), wong_tai_sin (8), temple (7), past (6), lot (5), smell (5), sound (5) | 104 | much (10), different (8), good (8), other (5) |

| Multisensory | 28 | 712 | 3.40% | 129 | temple (7), atmosphere (6), colour (6), experience (5) | 65 | beautiful (8), different (6), nice (6), colourful (5), same (5) |

| Health | 21 | 521 | 2.50% | 128 | incense (8), health (7), medicine (7) | 64 | good (7), chinese (6) |

| Culture | 18 | 416 | 2.00% | 82 | culture (7) | 45 | chinese (6) |

| Totals | 855 | 20,991 | 100.00% | 4196 | – | 1862 | – |

| Topic | Count | Representation | Smell- scape | Sound- scape | Inter- viewee | Multi- sensory | Geo- graphy | Cul- ture | Reli- gion | Other | Health | People | Time | Emo- tion | Archi- tecture | Experi- ence | Acti- vity | Memo- ry | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 108 | [‘culture’, ‘religion’, ‘time’, ‘fortune’, ‘bite’, ‘beautiful’, ‘noise’, ‘yesterday’, ‘incense’, ‘place’] | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0 | 111 | [‘smell’, ‘incense’, ‘smoke’, ‘health’, ‘religion’, ‘burn’, ‘stick’, ‘strong’, ‘little’, ‘kind’] | 0.66 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.18 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 1 | 99 | [‘sound’, ‘noise’, ‘hear’, ‘quiet’, ‘chant’, ‘crowd’, ‘area’, ‘calm’, ‘atmosphere’, ‘traditional’] | −0.1 | 0.70 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.17 | 0.1 | 0.14 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 74 | [‘time’, ‘dollar’, ‘guide’, ‘day’, ‘year’, ‘minute’, ‘early’, ‘work’, ‘expensive’, ‘come’] | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.28 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.24 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.18 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 59 | [‘colourful’, ‘small’, ‘colour’, ‘time’, ‘different’, ‘touch’, ‘matter’, ‘love’, ‘special’, ‘big’] | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 4 | 51 | [‘culture’, ‘religion’, ‘chinese’, ‘wong_tai_sin’, ‘buddhism’, ‘medicine’, ‘smoke’, ‘chinese medicine’, ‘temple’, ‘different’] | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 5 | 49 | [‘know’, ‘problem’, ‘fine’, ‘approach’, ‘acceptable’, ‘great’, ‘overall’, ‘good’, ‘strong’, ‘want’] | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 |

| 6 | 48 | [‘sure’, ‘idea’, ‘positive’, ‘sound’, ‘nice’] | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 7 | 44 | [‘garden’, ‘temple’, ‘commercialize’, ‘central’, ‘love’, ‘time’, ‘visit’, ‘food’, ‘pay’, ‘beautiful’] | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 8 | 39 | [‘health’, ‘peace’, ‘spiritual’, ‘pray’, ‘ask’, ‘mind’, ‘good thing’, ‘help’, ‘money’, ‘good’] | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.17 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 |

| 9 | 37 | [‘hong_kong’, ‘time’, ‘arrive’, ‘stop’, ‘bad’, ‘rest’, ‘travel’, ‘expensive’, ‘old’, ‘hand’] | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.12 |

| 10 | 35 | [‘wong_tai_sin’, ‘time’, ‘health’, ‘incense’, ‘culture’, ‘friend’, ‘pray’, ‘famous’, ‘offering’, ‘year’] | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.17 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| 11 | 29 | [‘clean’, ‘tourist’, ‘time’, ‘city’, ‘group’, ‘tour’, ‘spot’, ‘right’, ‘great’, ‘country’] | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Emergent Topic | Soundscape | Smellscape |

|---|---|---|

| Activity | 0.19 (173) | 0.29 (233) |

| Architecture | −0.25 (300) | 0.05 (419) |

| Culture | 0.46 (171) | 0.56 (134) |

| Emotion | 0.51 (650) | 0.78 (847) |

| Geography | 0.50 (279) | 0.61 (319) |

| Health | −0.62 (82) | −0.08 (580) |

| Memory | −0.32 (316) | 0.56 (990) |

| Multisensory | 0.50 (110) | 0.56 (163) |

| People | 0.31 (623) | −0.21 (252) |

| Religion | 0.40 (278) | 0.41 (984) |

| Time | −0.17 (344) | 0.12 (123) |

| Value | 0.00 (121) | 0.32 (561) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lindborg, P.; Lam, L.H.; Kam, Y.C.; Yue, R. Sensory Heritage Is Vital for Sustainable Cities: A Case Study of Soundscape and Smellscape at Wong Tai Sin. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167564

Lindborg P, Lam LH, Kam YC, Yue R. Sensory Heritage Is Vital for Sustainable Cities: A Case Study of Soundscape and Smellscape at Wong Tai Sin. Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167564

Chicago/Turabian StyleLindborg, PerMagnus, Lok Him Lam, Yui Chung Kam, and Ran Yue. 2025. "Sensory Heritage Is Vital for Sustainable Cities: A Case Study of Soundscape and Smellscape at Wong Tai Sin" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167564

APA StyleLindborg, P., Lam, L. H., Kam, Y. C., & Yue, R. (2025). Sensory Heritage Is Vital for Sustainable Cities: A Case Study of Soundscape and Smellscape at Wong Tai Sin. Sustainability, 17(16), 7564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167564