Inequalities in Drinking Water Access in Piura (Peru): Territorial Diagnosis and Governance Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

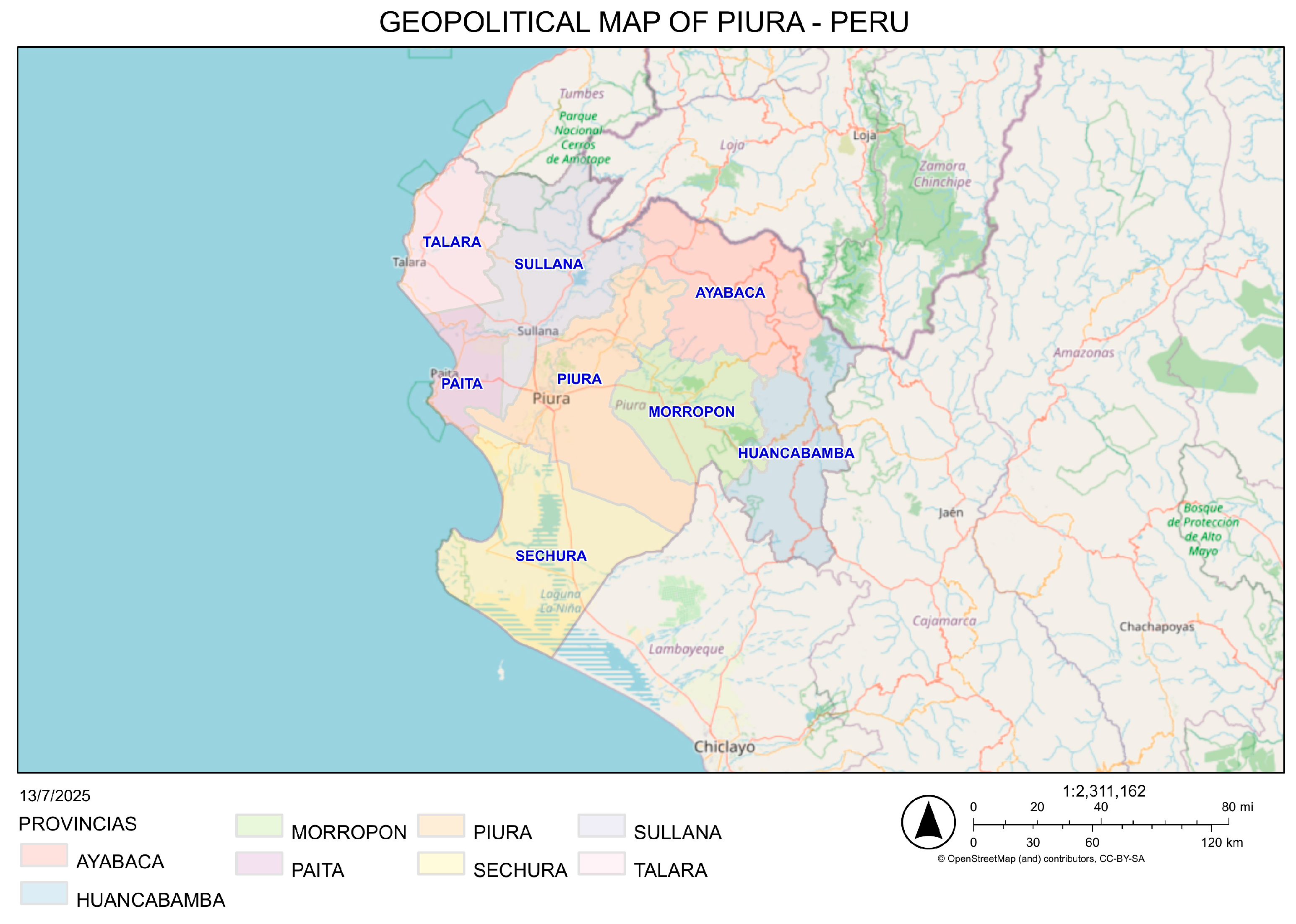

1.1. Territorial and Institutional Context in Piura

1.2. Research Gap and Conceptual Relevance

1.3. Research Objectives and Questions

1.4. Stakeholders and Innovation Cases in the Region

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Data Sources

- Structured review of the scientific literature: articles from Q1 and Q2 journals were selected through targeted keyword searches in high-impact academic databases, focusing on terms such as “rural water access”, “inequality”, “Latin America”, and “Peru”. Both global and regional perspectives were considered to contextualize Piura’s situation within broader development trends.

- Review of institutional reports and policy frameworks: sources included documents from the OECD, United Nations Inter-Agency Coordination Mechanism for Water (UN-Water), the ANA, the Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento (MVCS, Ministry of Housing, Construction and Sanitation), and OTASS. Additional national sources included the National Water Resources Management Plan (PNRH) and regional planning documents.

2.2. Literature Screening and Synthesis

2.3. Analytical Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Territorial Disparities in Drinking Water Access

3.2. Structural and Institutional Drivers of Disparity

3.3. Governance Efforts and Illustrative Interventions

4. Discussion

4.1. Integrative Analysis of Findings

4.2. Alignment with International Frameworks and SDGs

4.3. Lessons for Policy and Territorial Innovation

4.4. Limitations and Research Gaps

5. Conclusions

5.1. Synthesis of Key Findings

5.2. Policy and Practical Implications

5.3. Scientific Contribution

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- UN Water. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2023: Partnerships and Cooperation for Water. Available online: https://www.unwater.org/publications/un-world-water-development-report-2023 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- OECD. The Circular Water Economy in Latin America. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/the-circular-water-economy-in-latin-america_a0508572-en.html (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI). Perú: Formas de Acceso al Agua y Saneamiento Básico. Available online: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/boletines/boletin_agua_2024.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Cervilla, J. Emergencia Hídrica En Piura: Impactos y Desafíos Para La Gestión Del Agua En El Norte Del País. Available online: https://www.pucp.edu.pe/climadecambios/noticias/emergencia-hidrica-en-piura-impactos-y-desafios-para-la-gestion-del-agua-en-el-norte-del-pais/ (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Radio Nacional del Perú. Sequía En Piura: Otass Abastece Con Cisternas Zonas Donde Se Carece de Agua. Available online: https://www.radionacional.gob.pe/novedades/el-informativo-edicion-tarde/sequia-en-piura-otass-abastece-con-cisternas-zonas-donde-se-carece-de-agua (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- OECD. Water Governance in Peru. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/water-governance-in-peru_568847b5-en.html (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- OECD. Toolkit for Water Policies and Governance. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/toolkit-for-water-policies-and-governance_ed1a7936-en.html (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Sánchez Llanos, M.d.P.; Peñalver Higuera, M.J. Planificación y Gestión Integral Del Recurso Hídrico En La Región de Ancash. Rev. InveCom 2025, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, P.; Mazhari, T.; Khanolkar, A.R. Effectiveness of Infrastructural Interventions to Improve Access to Safe Drinking Water in Latin America and the Caribbean on the Burden of Diarrhoea in Children <5 Years: A Systematic Literature Review and Narrative Synthesis. Glob. Health Action. 2025, 18, 2451610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Moreno, C.; Amaya-Domínguez, J.; Bernal-Pedraza, A.Y. Experiences of Community-Based Water Supply Organizations Partnerships in Rural Areas of Colombia. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2024, 14, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellanos, E.; Guzman, W.; García, L. How to Prioritize the Attributes of Water Ecosystem Service for Water Security Management: Choice Experiments versus Analytic Hierarchy Process. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Slimming, P.A.; Wright, C.J.; Lancha, G.; Carcamo, C.P.; Garcia, P.J.; Ford, J.D.; Harper, S.L. Climatic Changes, Water Systems, and Adaptation Challenges in Shawi Communities in the Peruvian Amazon. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, B.; Aldunce, P.; Fallot, A.; Le Coq, J.F.; Sabourin, E.; Tapasco, J. Research on Climate Change Policies and Rural Development in Latin America: Scope and Gaps. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.; Gitau, M.; Lara-Borrero, J.; Paredes-Cuervo, D. Framework for Water Management in the Food- Energy-water (FEW) Nexus in Mixed Land-use Watersheds in Colombia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policy Framework on Sound Public Governance: Baseline Features of Governments That Work Well; OECD: Paris, France, 2020.

- Wu, S.; He, B.J. Assessment of Economic, Environmental, and Technological Sustainability of Rural Sanitation and Toilet Infrastructure and Decision Support Model for Improvement. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, N.G.; Lee, H. Sustainable and Resilient Urban Water Systems: The Role of Decentralization and Planning. Sustainability 2019, 11, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Water. Agua Para La Prosperidad y La Paz Informe Mundial de Las Naciones Unidas Sobre El Desarrollo de Los Recursos Hídricos 2024. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000391195 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Autoridad Nacional del Agua (ANA). Plan de Gestión de Recursos Hídricos de Cuenca Chira-Piura 2023. Available online: https://repositorio.ana.gob.pe/handle/20.500.12543/5655 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- OECD. Driving Performance at Peru’s Water and Sanitation Services Regulator. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/driving-performance-at-peru-s-water-and-sanitation-services-regulator_89f3ccee-en.html (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Albrecht, M.B. Disclosable Version of the ISR—Modernization of Water Supply and Sanitation Services; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Peruano de Economía (IPE). Piura: Continuidad En El Acceso a Agua Potable Llega a Nueve Horas al Día. Available online: https://ipe.org.pe/piura-continuidad-en-el-acceso-a-agua-potable-llega-a-nueve-horas-al-dia/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Benites Otero, Y.G. Diseño de Un Prototipo Compacto Potabilizador de Agua Superficial Con Independencia Energética. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Piura, Piura, Peru, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Japan International Cooperation Agency. Ex-Post Evaluation: The Project for Institutional Reinforcement of Water Supply and Sanitation in the North Area of Peru. Available online: https://www2.jica.go.jp/en/evaluation/pdf/2012_0800641_3_f.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Inter-American Development Bank (BID). Pilot Project: Access to Water and Sanitation to Dispersed Rural Communities—Phase II. Available online: https://www.iadb.org/es/proyecto/PE-G1009 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit. Adapting Urban Water Resources Management to Climate Change with Private Sector Participation. Available online: https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/28610.html (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Moscol Hilbck, D. Desarrollo de Estrategias de Gestión Del Recurso Hídrico Para Enfrentar La Escasez y Garantizar Su Uso Eficiente En La Ciudad de Piura; Universidad de Piura: Piura, Peru, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Periche Chunga, R. Fabricación de Prototipo Que Potabilice El Agua de Un Manantial Empleando Energía Solar En Sechura. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Piura, Piura, Peru, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Codina, L. Revisiones Bibliográficas Sistematizadas Procedimientos Generales y Framework Para Ciencias Humanas y Sociales; Pompeu Fabra University: Barcelona, España, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kassie, A.W.; Mengistu, S.W. Spatiotemporal Analysis of the Proportion of Unimproved Drinking Water Sources in Rural Ethiopia: Evidence from Ethiopian Socioeconomic Surveys (2011 to 2019). J. Environ. Public Health 2022, 2022, 2968756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, E.E.; Lauber, T.; Van Den Hoogen, J.; Donmez, A.; Bain, R.E.S.; Johnston, R.; Crowther, T.W.; Julian, T.R. Mapping Safe Drinking Water Use in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. Science 2024, 385, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azage, M.; Motbainor, A.; Nigatu, D. Exploring Geographical Variations and Inequalities in Access to Improved Water and Sanitation in Ethiopia: Mapping and Spatial Analysis. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassivi, A.; Guilherme, S.; Bain, R.; Tilley, E.; Waygood, E.O.D.; Dorea, C. Drinking Water Accessibility and Quantity in Low and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Alam, K. Inequality in Access to Improved Drinking Water Sources and Childhood Diarrhoea in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 226, 113493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Implementing the OECD Principles on Water Governance: Indicator Framework and Evolving Practices. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/implementing-the-oecd-principles-on-water-governance_9789264292659-en.html (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Inquilla-Mamani, J.; Quispe-Borda, W.; Apaza-Ticona, J.; Inquilla-Arcata, F.; Calatayud-Mendoza, A.P.; Chaiña-Chura, F.F.; Velásquez-Sagua, H.L.; Mamani-Flores, A. Access to Drinking Water and Reduction of Acute Diarrheal Diseases in Rural Populations Puno-Peru. J. Posthumanism 2025, 5, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, L.; Vargas, L.; Jimenez, A. Priorities for the Rural Water and Sanitation Services Regulation in Latin America. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1406301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesus, F.S.M.; Monteiro, A.M.V.; Tomasella, J. Spatial Inequalities in Access to Safe Drinking Water in an Upper-Middle-Income Country: A Multi-Scale Analysis of Brazil. Water 2023, 15, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toribio Brito, G.E.; Ríos, A.L. Challenges in the Access to Piped Water in Rural Localities of the Municipality of Acapulco de Juarez, Guerrero, Mexico. Int. J. Hydrol. 2024, 8, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahoy, M.J.; Hubbard, S.; Mattioli, M.; Culquichicón, C.; Knee, J.; Brown, J.; Cabrera, L.; Barr, D.B.; Ryan, P.B.; Lescano, A.G.; et al. High Prevalence of Chemical and Microbiological Drinking Water Contaminants in Households with Infants Enrolled in a Birth Cohort-Piura, Peru, 2016. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 107, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Vásquez, A.; Vargas-Fernández, R. Beyond the Faucet: Social-Geographic Disparities and Trends in Intermittent Water Supply in Peru. J. Water Health 2025, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.; Carvalho, M.; Martins, S. Sustainable Water Management: Understanding the Socioeconomic and Cultural Dimensions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.V.M.; dos Santos, J.A.N.; Quindeler, N.d.S.; Alves, L.M.C. Critical Factors for the Success of Rural Water Supply Services in Brazil. Water 2019, 11, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlbert, M.; Acharibasam, J.B.; Datta, R.; Strongarm, S.; Starblanket, E. Decolonizing Indigenous Drinking Water Challenges and Implications: Focusing on Indigenous Water Governance and Sovereignty. Water 2024, 16, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.A.; Megdal, S.B.; Zuniga-Teran, A.A.; Quanrud, D.M.; Christopherson, G. Equity Assessment of Groundwater Vulnerability and Risk in Drinking Water Supplies in Arid Regions. Water 2024, 16, 3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain | Description | Geographic Focus | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coverage | Low service penetration in rural and peri-urban zones (e.g., <30% in Sub-Saharan Africa, <50% in rural highlands of Peru, and <70% in rural Piura) | Sub-Saharan Africa; Highlands of Peru; Piura, Peru | [4,19,31,37,38] |

| Continuity | Service often available (≥50% of piped systems in low-income countries are intermittent; <8 h/day in some Andean districts and <3 h/day in rural Piura) | Global (low-income countries—LICs); Andean Peru; Piura, Peru | [19,34,35,41,42] |

| Water quality | Presence of pathogens and chemicals (e.g., ~70% of waterborne disease burden in Southeast Asia linked to untreated water; arsenic detected in rural Peru; ≥40% of households in Piura report E. coli contamination) | Southeast Asia; Piura, Peru | [35,41] |

| Source reliability | Reliance on informal sources (e.g., ~30% of rural households in Latin America rely on unimproved water sources; >150,000 people in Piura use cistern trucks, shallow wells, or untreated surface water) | Rural Latin America; Piura, Peru | [42] |

| Income-based inequity | Access disparities correlate with income (e.g., ~60% of those without access in Latin America are rural poor; households in the lowest income quintile in Peru are >2× more likely to lack safely managed water) | Latin America; Peru | [4,38,39,40] |

| Type of Barrier | Description | Manifestation in Piura | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory fragmentation | Multiple overlapping institutions without unified mandates | Disjointed interventions (ANA, OTASS) | [7,20] |

| Technical capacity | Lack of trained personnel at municipal or community level | Informal or poorly maintained systems | [28,42] |

| Monitoring deficit | Absence of reliable service data and quality control | No baseline to assess water continuity | [24,38] |

| Institutional coordination | Weak articulation between local and national actors | Delays, overlap, limited accountability | [29,43] |

| Level | Type of Intervention | Key Characteristics | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global | IWRM Framework (UN-Water) | Multisector coordination, basin-level planning | [19] |

| Regional | Public–Community Partnerships (Colombia, Brazil) | Decentralization, community co-management | [36,44] |

| National (Peru) | ANA watershed governance programs | Monitoring, integration, local committees | [36] |

| Piura (Piura) | University–community pilot projects | Treatment tech, training, limited scalability | [41] |

| Dimension | Manifestation in Piura | Interlinked Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Territorial disparities | Intermittent access, unsafe storage, rural–urban gaps | Income, location, climate exposure |

| Institutional weakness | Fragmented mandates, lack of monitoring, low enforcement capacity | Coordination failures, underfunding, decentralization |

| Isolated innovations | University-led pilots without scale-up | No institutional linkage, absence of policy integration |

| Global Framework | Key Principle or Target | Observed Condition in Piura |

|---|---|---|

| OECD water governance | Coordination, effectiveness, trust | Implementation gap at local level |

| IWRM (UN-Water) | Multisector integration, basin-scale planning | Weak territorial articulation, institutional silos |

| SDG 6.1 | Universal access to safe and affordable drinking water | Coverage achieved, but continuity and quality remain weak |

| SDG 6.b | Community participation in water and sanitation management | Limited data systems and community monitoring |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez Ruiz, E.A.; Cremades, L.V.; Villanueva Benites, S. Inequalities in Drinking Water Access in Piura (Peru): Territorial Diagnosis and Governance Challenges. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167542

Sánchez Ruiz EA, Cremades LV, Villanueva Benites S. Inequalities in Drinking Water Access in Piura (Peru): Territorial Diagnosis and Governance Challenges. Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167542

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez Ruiz, Eduardo Alonso, Lázaro V. Cremades, and Stephanie Villanueva Benites. 2025. "Inequalities in Drinking Water Access in Piura (Peru): Territorial Diagnosis and Governance Challenges" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167542

APA StyleSánchez Ruiz, E. A., Cremades, L. V., & Villanueva Benites, S. (2025). Inequalities in Drinking Water Access in Piura (Peru): Territorial Diagnosis and Governance Challenges. Sustainability, 17(16), 7542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167542