Measurement of the Modernization of Rural Governance Capacity: A Systematic Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Theoretical Basis

3.1. Systems Theory

3.1.1. Systems and Systems Theory

- (1)

- Holism represents one of the core and most distinct characteristics of systems theory. It denotes the existence of intricate interrelations among a system’s elements, whereby the functions of these elements are subordinate to the system’s overarching function. Critically, the system’s aggregate function does not equate to the mere arithmetic sum of its elements’ individual functions [31]. Owing to the interactive dynamics within the system, all constituent elements coalesce to form an organized totality [32], thereby engendering emergent functions that no single element can independently manifest. This gives rise to the phenomenon wherein the system’s functional capacity surpasses the simple additive sum of its elements’ capabilities.

- (2)

- Hierarchy refers to the phenomenon whereby a system exhibits distinct layers and hierarchical orderliness owing to differences in the modes of interconnection among its elements. Elements and hierarchical levels serve as the primary tools for depicting a system’s structure. Notably, there is a relativity between the system and its constituent elements, as well as between higher-level and lower-level subsystems [33].

- (3)

- Openness denotes the property of a system to continuously engage in exchanges of matter, energy, and information with its external environment. Through the introduction of negative entropy from the environment, the system reduces its total entropy, maintains a state far from equilibrium, and enhances the likelihood of self-organized evolution [29].

- (4)

- Stability refers to the capacity of an open system to maintain a certain level of self-stability under external influences, enabling it to self-regulate within a specific range to preserve and restore its original ordered state, structure, and functions [29].

- (5)

- Purposefulness refers to the characteristic of a system exhibiting a tendency toward a pre-determined state [29]. The overarching goal of the system serves as a pivotal guide for coordinating its elements [34], through which synergistic interactions among suboptimal elemental objectives facilitate the optimization of the system’s holistic functionality [35].

- (6)

- Self-organization refers to the capacity of a system, during its evolutionary process, to enable coordinated symbiosis among its internal elements and spontaneously generate spatial, temporal, or functional joint actions that form ordered structural activities—all without the coercive drive of external forces [36].

3.1.2. Applications of Systems Theory

- (1)

- Characteristics of Holism. Compared with “fragmented” governance approaches, the overall coordination of subjects allows for a more rational allocation of governance resources, thereby enabling the rural governance system to function more efficiently and sustainably [38]. Owing to the differences among multiple subjects in development goals, value orientations, ideological concepts, and information resources, the problem of “fragmentation” caused by decentralized actions often arises in the rural governance process [39], which restricts the improvement of governance effectiveness and sustainable development. The complexity and interconnection of rural governance demand a holistic perspective, regarding rural governance as an organic, unified whole composed of multiple interrelated and interacting elements. It is necessary to comprehensively consider the development and optimization of all elements, achieve coordinated and balanced development of all parts, and thus attain the optimal goal that the overall function is greater than the sum of the functions of the parts [37].

- (2)

- Characteristics of Hierarchy. The subjects of rural governance constitute a pluralistic governance community composed of grassroots Party organizations, local governments, villager autonomous organizations, rural economic and social organizations, and rural members participating in governance activities [40]. The hierarchy of the rural governance community is embodied in the relational structure among subjects, which also serves as a key influencing factor for governance efficiency [41]. According to resource dependence theory, no governance subject can possess all resources to achieve self-sufficiency, necessitating regular resource exchanges with other subjects [42]. In the governance process, vulnerable subjects often exchange their control rights for resources, which over time evolves into unequal hierarchical relationships of subordination and domination among subjects [43]. At present, rural governance in China has formed governance models dominated by administration, autonomy, or the market, with differences in the status and relational structures of subjects within the governance community across these models [41].

- (3)

- Characteristics of Openness. The external environment of the rural governance system encompasses the aggregate of production factors and the policy milieu. An increase in the quantity and quality of external inputs can facilitate the growth of systemic benefits [44]. This primarily involves the continuous influx of technology, capital, data, knowledge, and management—material, energy, and information that influence rural development—from the external environment during the rural governance process. In China, rural governance has established a pyramidal hierarchical structure of “central–local–grassroots” at the vertical level [45]. Through measures, such as governance framework design, foundational institutional support, public policy guidance, and resource investment, superior departments ensure resource provision and guidance for subordinate entities [46].

- (4)

- Characteristics of Stability. The process by which rural governance subjects handle specific matters follows a cycle of “detection (sorting)—matching—response—feedback—optimization.” Firstly, subjects organize the material, energy, and information at their disposal, subjecting them to standardized processing to form information sets. Subsequently, these sets are matched against the subjects’ “stimulus–response” rules, generating context-specific solutions, measures, and actions. Finally, the effectiveness of each action is validated through feedback on its outcomes, driving the continuous optimization of action plans and enhancing the robustness and adaptability of subjects’ governance capabilities [47]. When a single subject manages multiple tasks concurrently, variances in processing progress across tasks can induce performance fluctuations. Among multiple subjects handling parallel tasks, the accumulation of such progress disparities further amplifies fluctuations in governance capacity.

- (5)

- Characteristics of Purposefulness and Self-organization. The emergence of a governance community is premised upon the existence of shared objectives [48]. To achieve the collective goal of rural “good governance,” multiple subjects adopt diverse approaches to resolve interest conflicts and promote resource integration, thereby forming new interest alliances (interest communities) [45]. These alliances enable efficient resource exchange and allocation; through the mechanisms of shared obligations and mutual benefit, they generate spillover effects that lead to win–win outcomes, ultimately attaining maximum benefits unattainable by individual subjects [44]. The structure and order within interest alliances originate from the interactive influences among internal subjects of the system [49]. For individual subjects, the fundamental objective is to ensure their own survival, development, and growth. Consequently, they engage in resource exchanges with other subjects. To acquire resources more effectively, subjects divide labor according to their capabilities and conditions, taking on specific responsibilities in rural governance, such as capital investment, external liaison, information feedback, and action implementation [47].

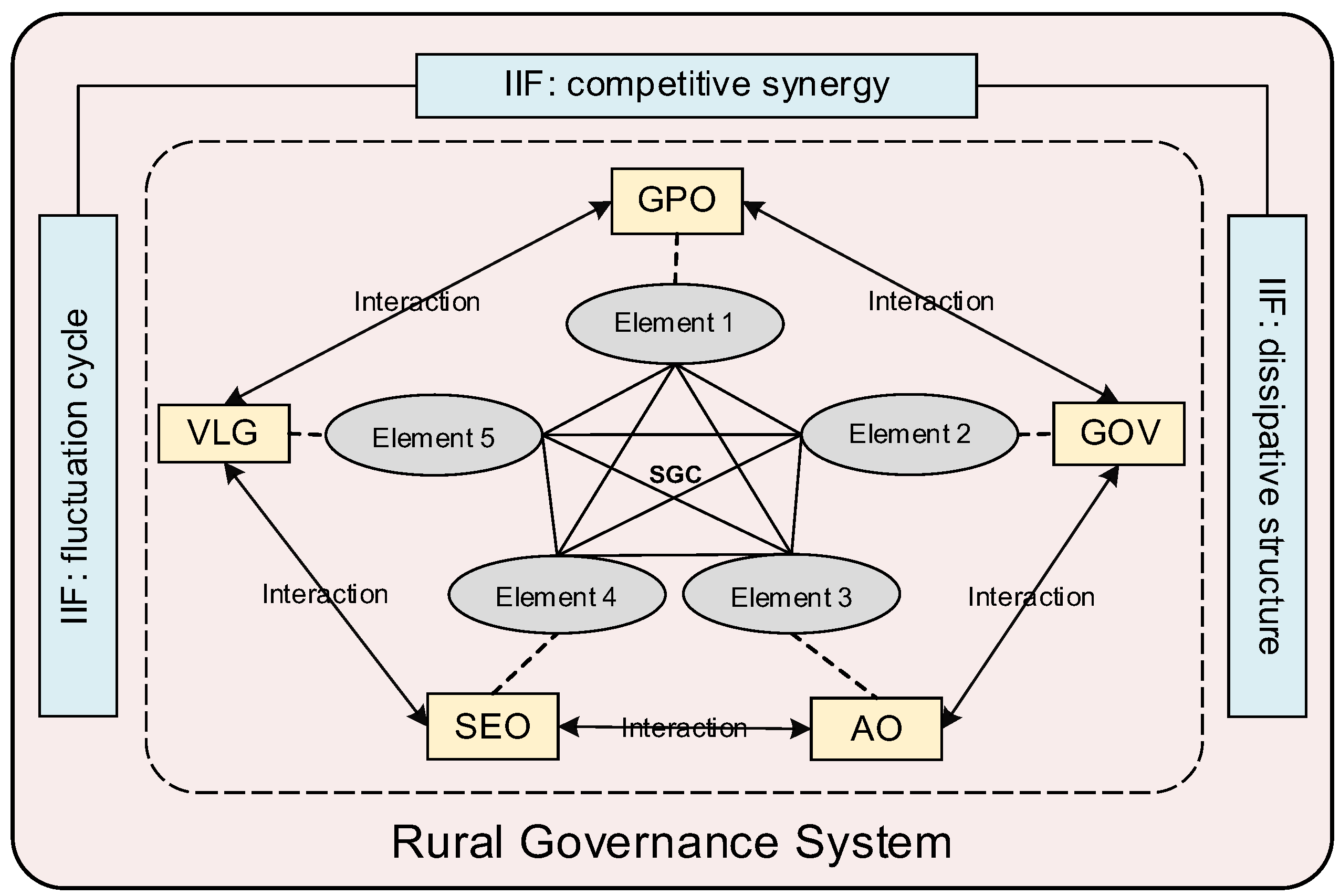

3.2. Rural Governance System

3.2.1. Dual Structure

3.2.2. Component Connotation

3.2.3. Organic Unity Relationship

4. Research Methods

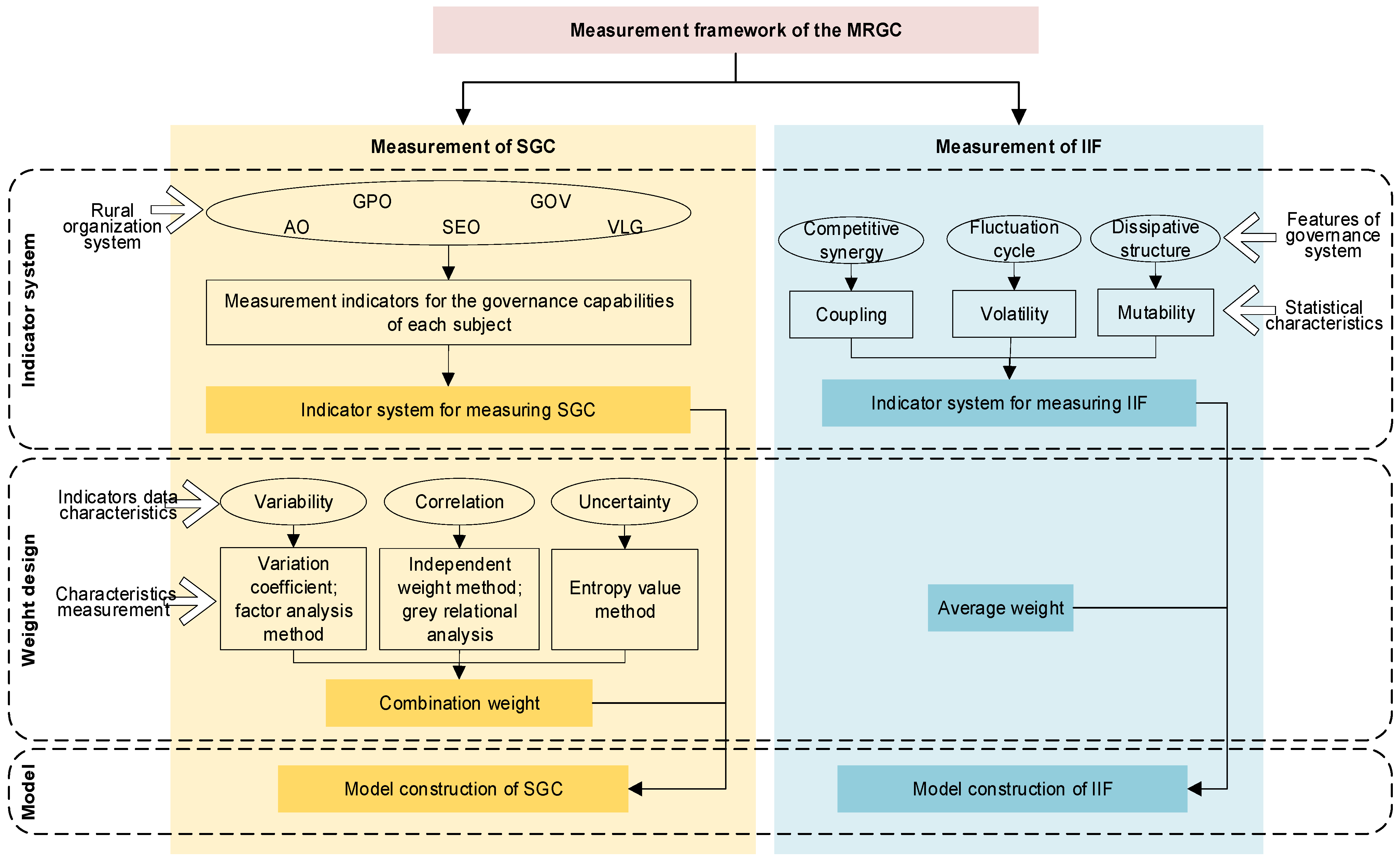

4.1. Measurement Framework

4.2. Dimension 1: The Subject Governance Capacity (SGC)

4.2.1. The Indicator System of SGC

- (1)

- The capacity to build a grassroots Party, as the core leadership in rural governance, serves as a fundamental guarantee for the MRGC. The governance capacity of grassroots Party organizations requires them to have a certain influence in various fields, groups, and levels. It is necessary to build a strict organizational structure that “extends vertically to the bottom and horizontally to the edges.” The key lies in the capacity for building the Party’s organizational system, the capacity for building the leading groups and the cadre teams, the capacity for building the talent teams, and the capacity for building the Party member teams: (a) The capacity to develop an organizational system serves as the foundation for incorporating the MRGC. A robust organizational network ensures the effective implementation of the Party’s lines, principles, and policies in rural areas, enabling the overall coordination and integration of various governance resources. This capacity is measured based on the proportion of administrative villages with Party organizations. (b) The capacity for building leading cadres and cadre teams determines the scientificity and executive effectiveness of governance decisions. A high-caliber cadre team can accurately grasp the needs of rural governance and promote the effective implementation of governance measures, which is measured by the proportion of village Party secretaries who concurrently serve as village directors. (c) The capacity for talent team development provides sustainable intellectual support for rural governance. By attracting and cultivating professional talents, technical bottlenecks and experience deficiencies in governance can be addressed, and this capacity is measured based on the proportion of young Party members. (d) The capacity for Party member team development is key to organizing joint efforts in governance. Giving full play to the role of Party members as leaders and representatives can strengthen the connection between Party organizations and the masses, allowing for the people that form the foundation for governance to come together. This capacity is measured based on the proportion of active Party members. The coverage of party organizations in administrative villages nationwide had exceeded 99.9 percent as of June 2022 (The Organization Department of The CPC Central Committee. Statistical Bulletin of the Communist Party of China. Available online: http://gs.people.com.cn/n2/2022/0630/c183342-40017329.html (accessed on 4 November 2024)), and the indicator “proportion of administrative villages with Party organizations” does not have a degree of differentiation, so it is removed.

- (2)

- As the government is a leading actor in rural public affairs, its capacity for governance directly affects the fairness, inclusiveness, and development direction of rural governance. The governance capacity of the government requires that it can organize, coordinate, and integrate the production factors of various subjects according to the overall national strategic policy, and supervise the key links in rural construction, maintain social order, and ensure public safety, which is reflected in the rural public service capacity, public management capacity, and public security guarantee capacity [57]: (a) The capacity to provide public services is key to meeting villagers’ basic public needs and achieving equal access to basic public services between urban and rural areas. These public services primarily cover key areas of livelihood such as elderly care, medical care, and education. This capacity is measured based on indicators such as the rate of participation in rural social endowment insurance and the rate of coverage by convenience service centers. (b) The capacity for public management is reflected in the design and coordination of policy implementation, planning formulation, and other aspects of rural governance, ensuring the systematicity and standardization of the governance process. This capacity is measured based on the rate of coverage by rural revitalization plans. (c) The capacity to guarantee public safety is a prerequisite for the stable development of rural areas. By improving public security prevention and control systems and responding to and handling public emergencies, the rural security defense line can be strengthened. This capacity is measured based on the social sense of security. Based on the results of the national government hall census, as early as 2017, 38,513 convenience service centers had been set up in townships (streets) across the country, with a coverage rate of 96.8% (Results of the First National General Survey of Government Affairs Halls Announced: The Coverage Rate of Government Affairs Halls at or above the County Level Exceeds 90%. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2017-11/23/content_5241850.htm (accessed on 8 January 2025)). The coverage rate of convenience service centers in all regions is generally high, and the indicators are not differentiated, so the index of “coverage rate of convenience service centers” is excluded.

- (3)

- The capacity of autonomous organizations, as bridges connecting the government to their villagers, serves as the core carrier for achieving villagers’ self-governance. The governance capacity of autonomous organizations requires that they can understand and implement major national policies, laws, and regulations associated with agriculture and rural areas, and can clearly and accurately publicize and explain to the public, and effectively organize and mobilize other subjects to participate in governance activities, and in the construction of rural rule of law; at the same time, they should be able to effectively mediate conflicts and disputes, and maintain rural social harmony and stability [58]. Regarding factors affecting self-governance, three aspects can be measured: policy interpretation capacity, organizational mobilization capacity, and dispute mediation capacity: (a) Policy interpretation capacity can bridge the “last mile” of policy implementation, help villagers accurately understand governance requirements, and enhance their recognition of governance work. This capacity is reflected by a village director’s average years of education. (b) Organizational mobilization capacity is the foundation for facilitating villagers’ participation in governance. By guiding villagers to participate in the decision-making of public affairs, their endogenous motivation for self-governance can be stimulated. This capacity is reflected by the voting rate in village committee elections. (c) Dispute mediation capacity is an important factor that guarantees internal harmony in rural areas. A high capacity for dispute mediation allows for neighborhood conflicts to be resolved based on village rules, conventions, and moral norms, and thus, reduces governance costs. This capacity is reflected by the level of harmony in rural areas.

- (4)

- As important participants in rural governance, social and economic organizations provide diversified support to governance. The governance capacity of social and economic organizations requires them to focus on the development of rural industries, establish a comprehensive organizational service system with complete content and structure, complete internal systems and procedures, and attract villagers to participate in rural organizations [59]. Regarding this support, three aspects can be measured: institutional building capacity, villager organizing capacity, and operational development capacity: (a) Institutional building capacity is a prerequisite for standardizing social and economic organizations’ own operations. A sound internal management system can ensure their orderly participation in governance and enhance service credibility, which is measured based on the degree of improvement in the collective economic system. (b) Villager organizing capacity is reflected in organizing production cooperation and skill training, among other aspects, which can enhance the degree of organization in villagers’ social life. This capacity is reflected by the rate of participation in the collective economy and cooperatives. (c) Operational development capacity is key in driving rural industrial revitalization. By activating rural resources and developing characteristic industries, economic support can be provided for governance. This capacity is measured based on the annual income of the collective economy.

- (5)

- As villagers are the primary actors in rural governance activities, their capabilities and qualities constitute the core driving force for the transformation of governance effectiveness. The governance capacity of villagers requires that they be able to obtain village and social conditions and information on upper development policies, have the ability to analyze and judge problems, make suggestions on the handling of public affairs through legal procedures or reflect their own reasonable demands, and be skilled in using modern information technology, which is embodied in the ability to make recommendations, to comply with procedures, and to apply digitalization [60,61]. (a) Discuss and advise capability is the foundation for villagers to participate in rural governance. Accurate information transmission, effective decision-making suggestions, and unobstructed expression channels can ensure that the direction of governance fully meets villagers’ needs. This capacity is measured based on the proportion of villagers with a college education or above. (b) Process compliance capability is a prerequisite for maintaining governance order. Villagers’ recognition and compliance with laws, regulations, and village rules and conventions ensure the orderly conduct of governance activities. This capacity is measured based on villagers’ degree of compliance. (c) Digital application capacity is an important quality for adapting to modern governance. By using digital tools to participate in the handling of government affairs and information acquisition, the intelligent transformation of governance methods can be promoted. This capacity is measured based on the proportion of rural households with computers.

4.2.2. Weight Design

- (1)

- Determine the indicator weights under the principle of variability. Calculate the indicator weights using the coefficient of variation method and the factor analysis method, and then synthesize the variability weights using the addition principle:

- (2)

- Determine the indicator weight under the principle of correlation. The independence weight method and grey correlation analysis method are used to calculate the indicator weight, and the correlation weight is determined using the addition principle:

- (3)

- Calculate the indicator weight under the uncertainty principle; that is, the entropy method is used to calculate the indicator weight .

- (4)

- Combine the above three weights according to the multiplication principle to obtain the information content of each indicator.

- (5)

- Normalize the amount of information of the indicators to obtain the weight of the measurement indicator for the governance capacity of the subject:

- (6)

- The governance capacity of each subject adopts the average weighting method: , .

4.2.3. Model Construction

4.3. Dimension 2: The Inter-Subject Interaction Force (IIF)

4.3.1. The Indicator System of IIF

4.3.2. Weights and Models

4.4. Comprehensive Measurement of the MRGC

4.4.1. Comprehensive Measurement Indicator System

4.4.2. Weights and Models for Comprehensive Measurement

4.5. Identification of Obstacle Factors

4.6. Research Area and Data Sources

5. Results

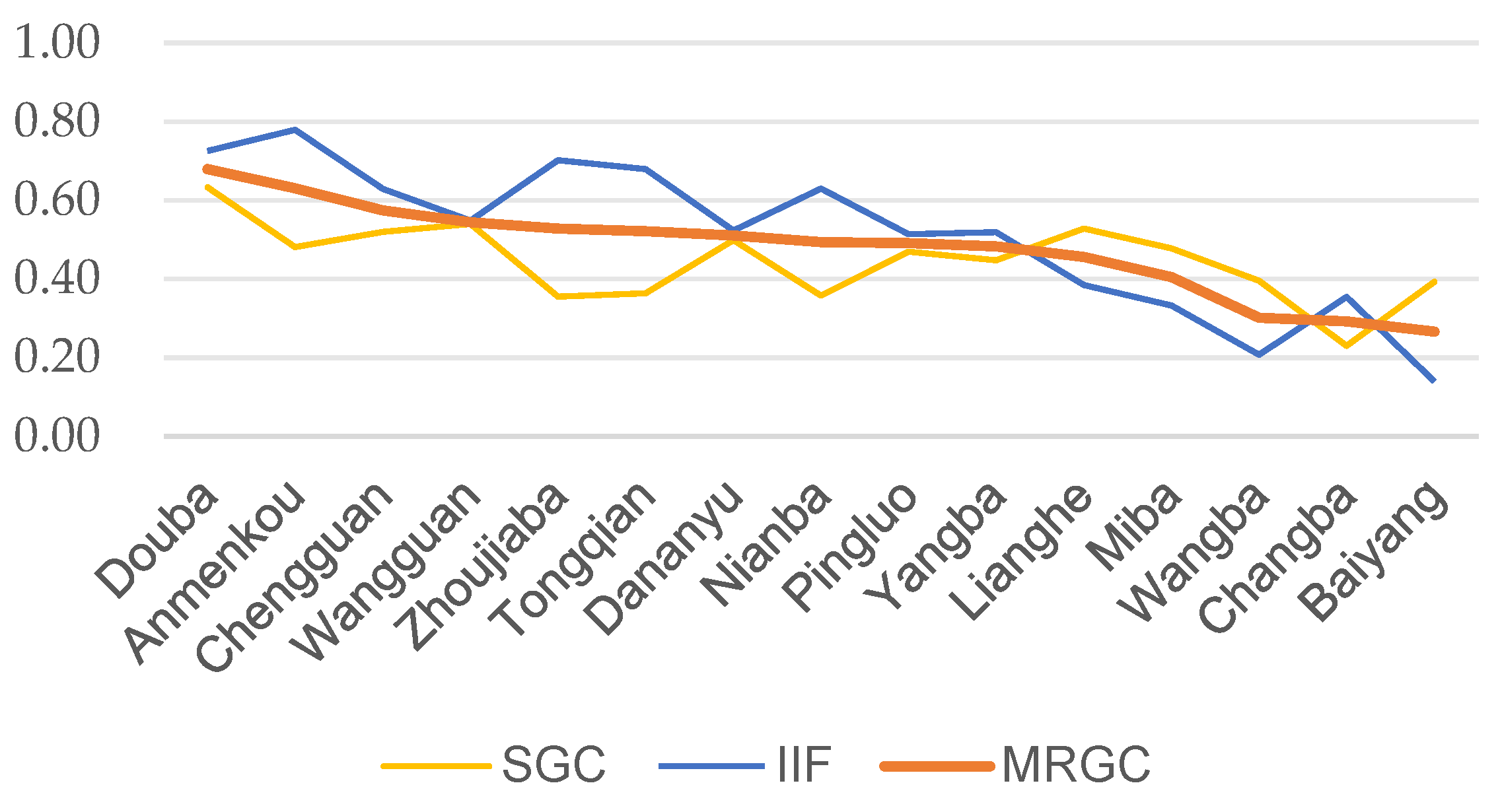

5.1. Analysis of the MRGC

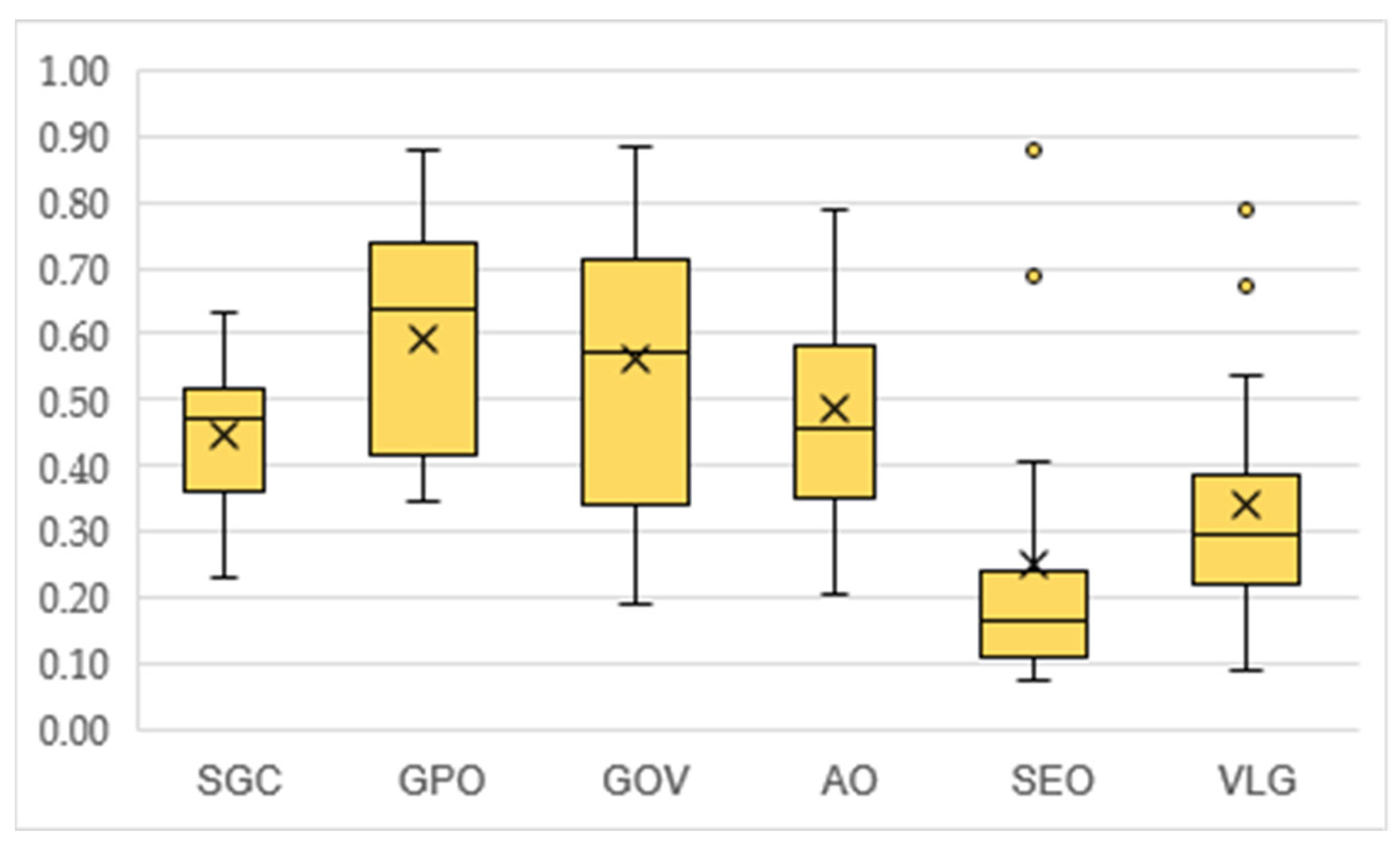

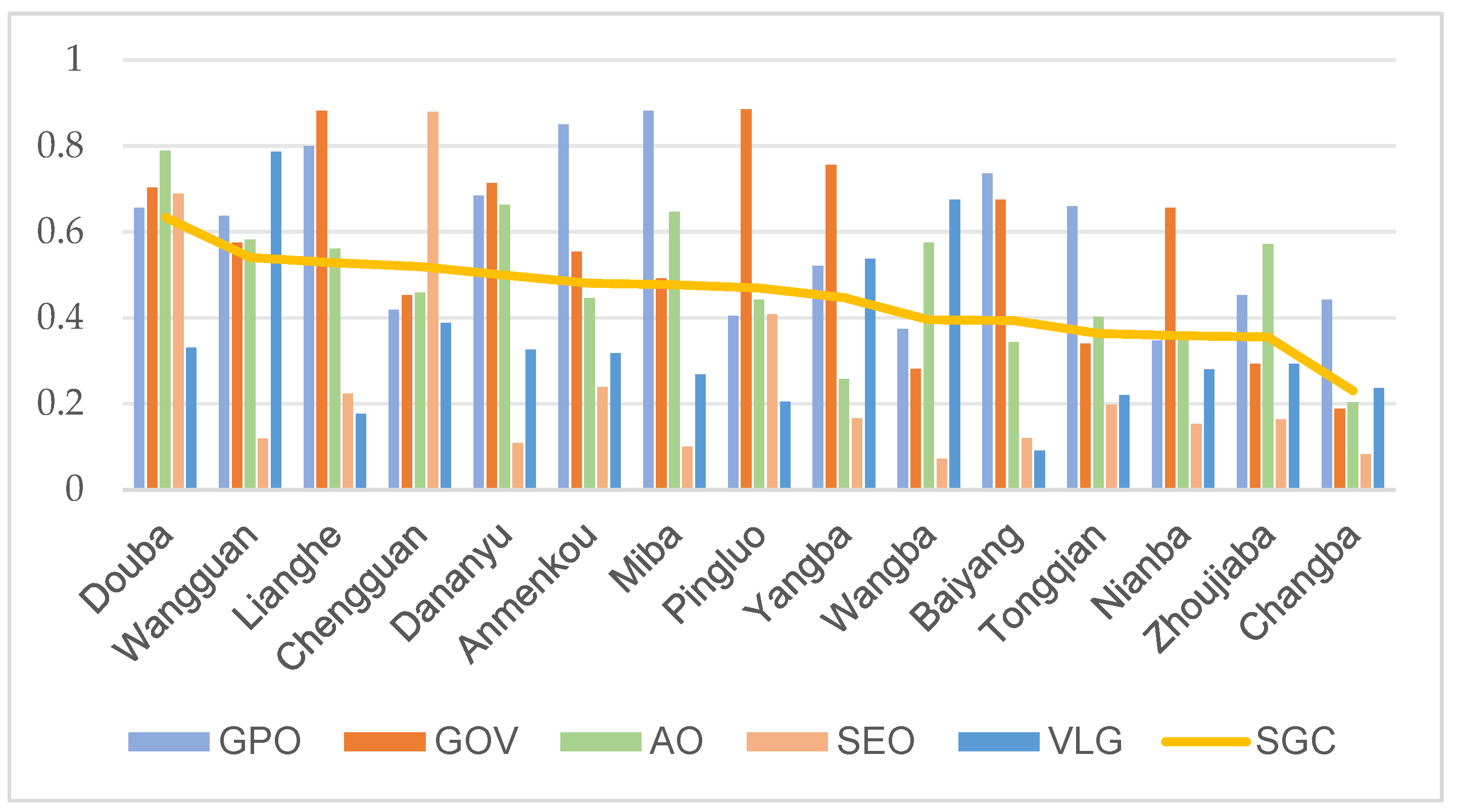

5.2. Analysis of SGC

5.2.1. Combination Weight

5.2.2. Results of SGC

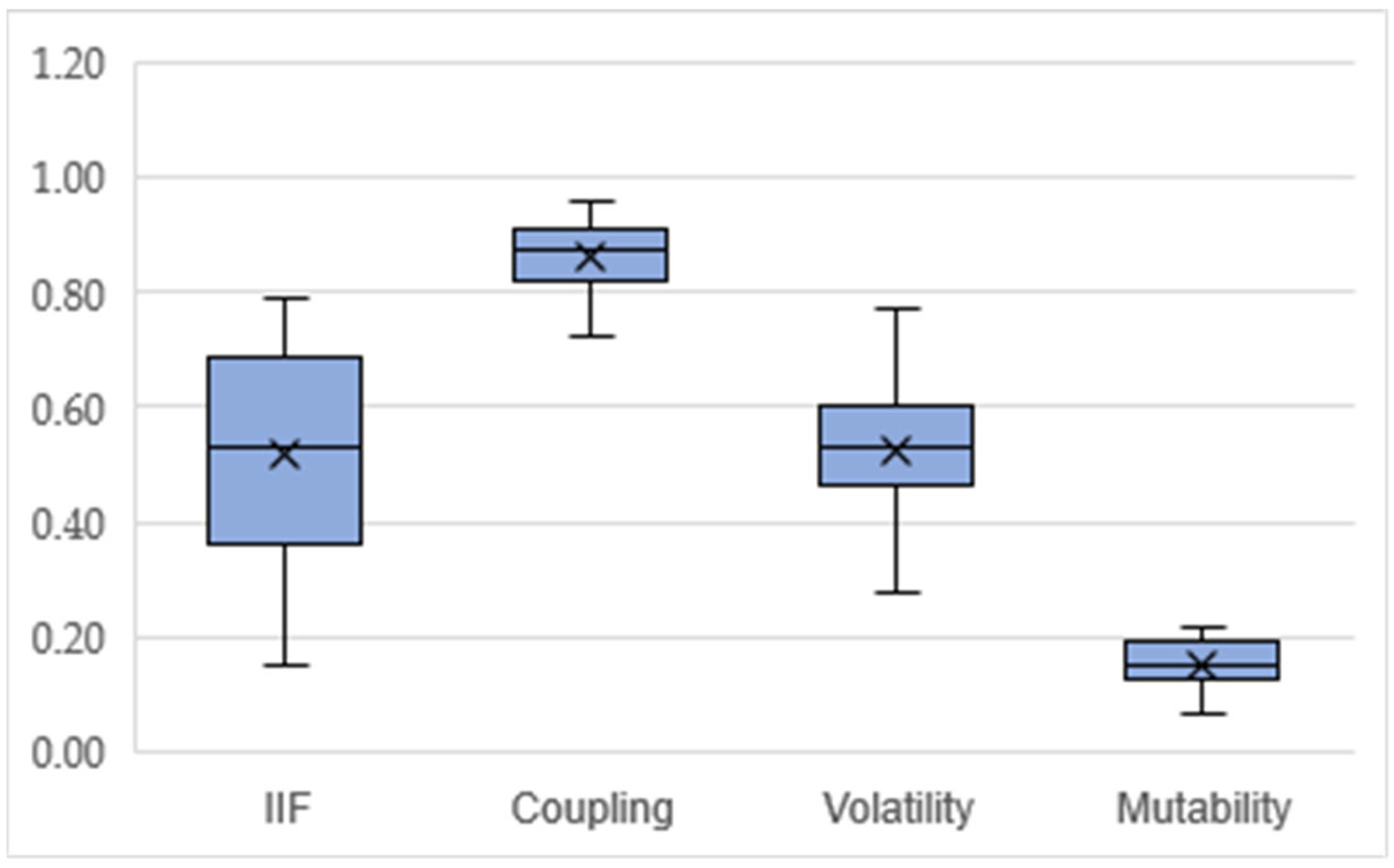

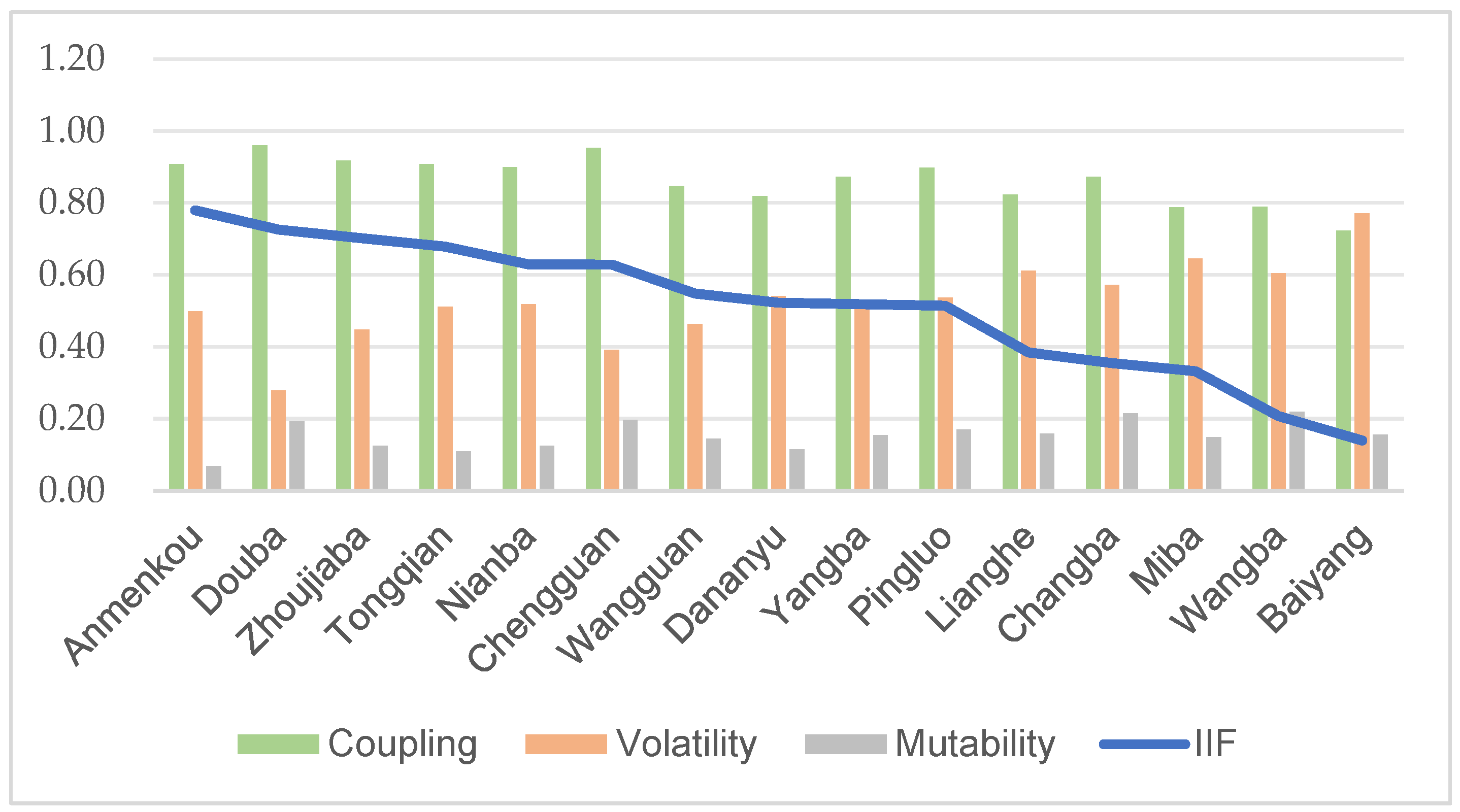

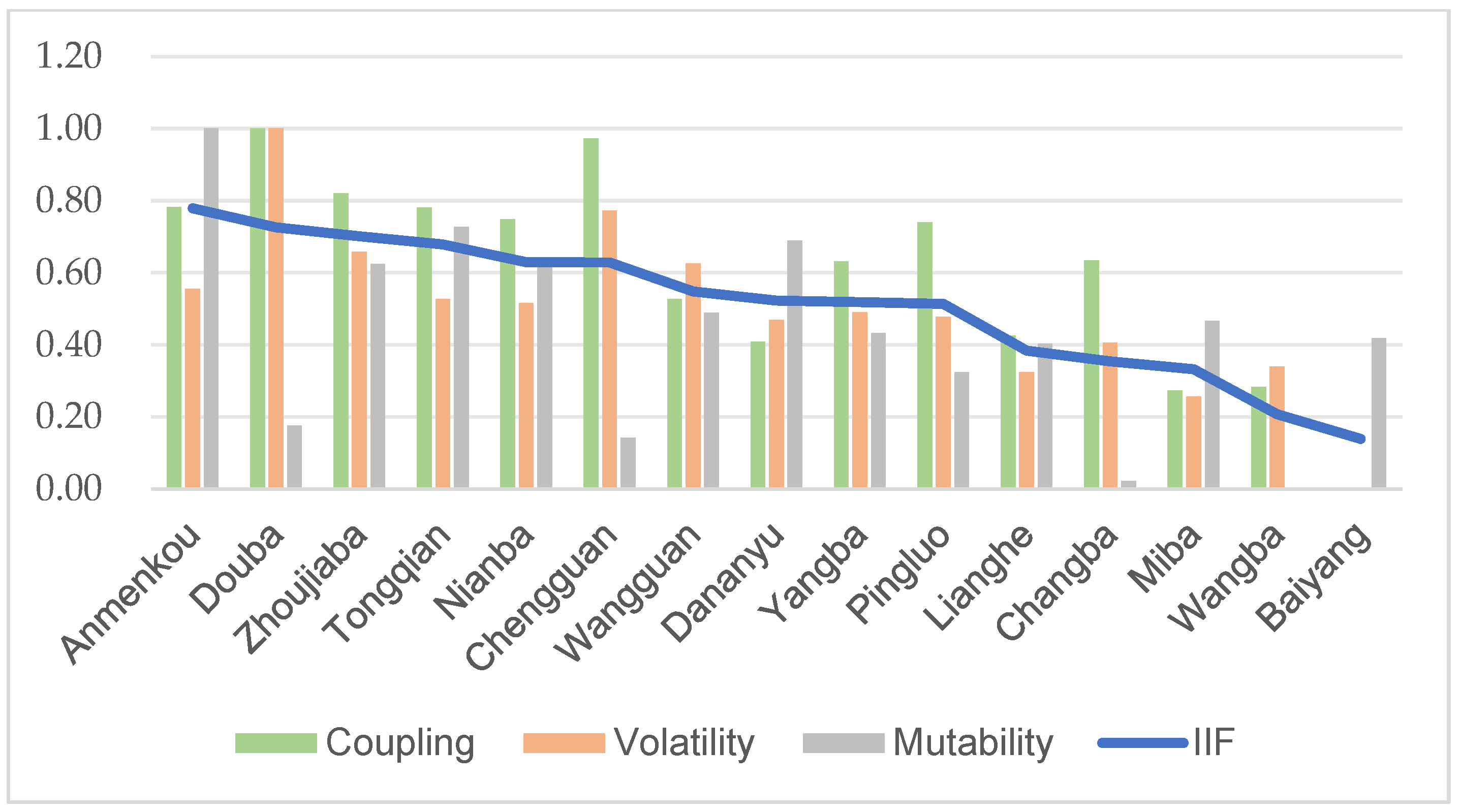

5.3. Analysis of IIF

5.4. Obstacle Factor Analysis

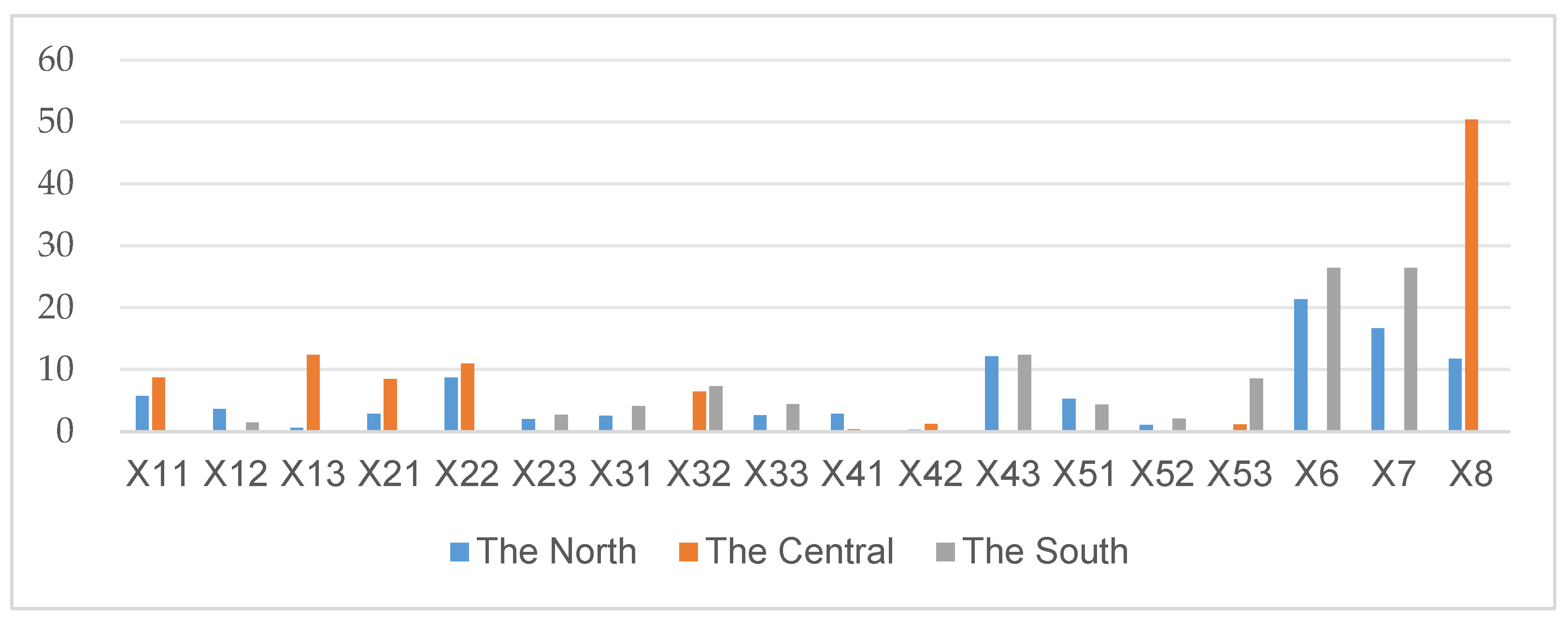

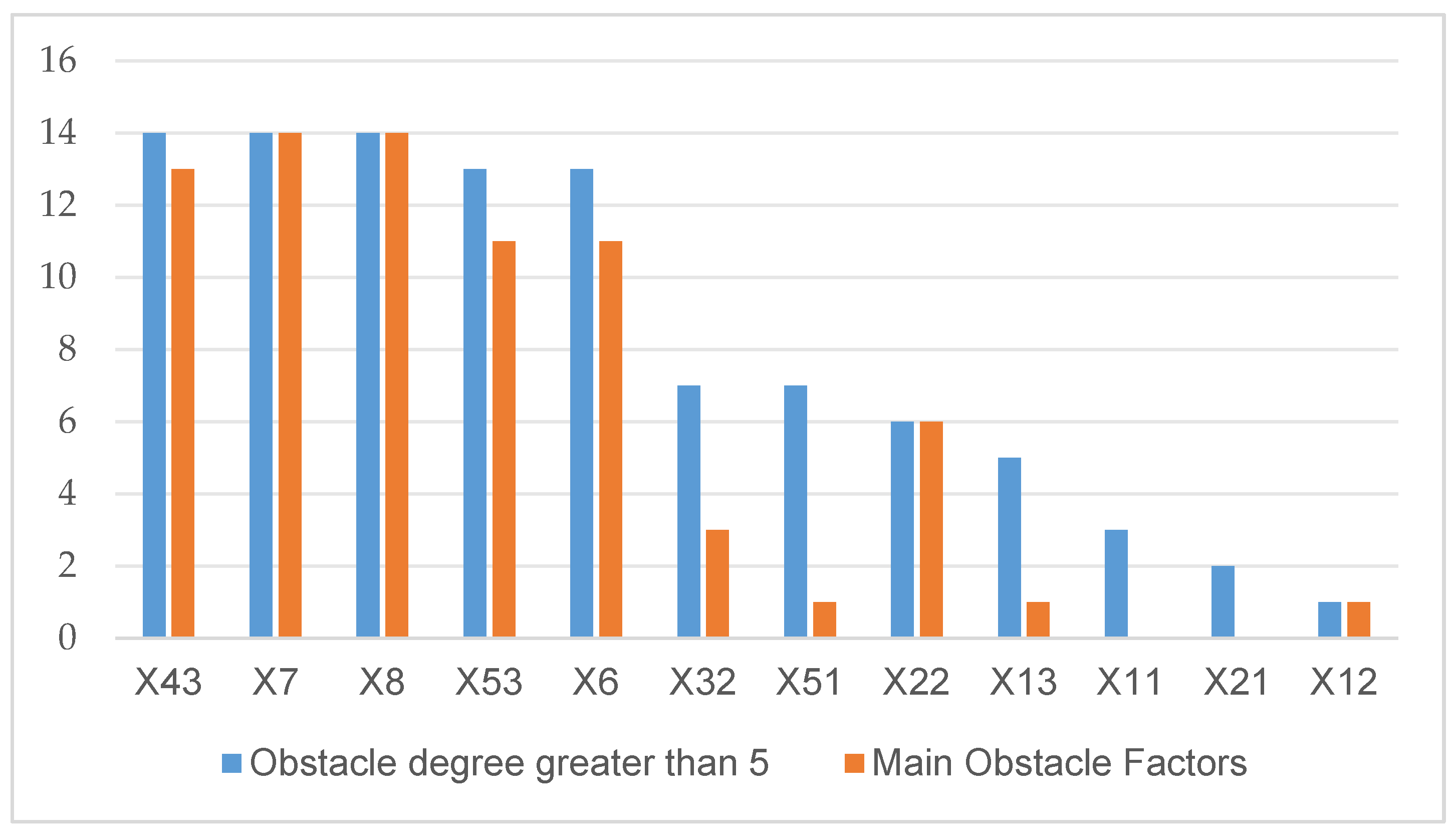

5.4.1. Obstacle Factors at the Regional Level

5.4.2. Obstacle Factors at the Township Level

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Research Contributions

- (1)

- Differing from previous studies that measured the MRGC from the perspective of rural public affairs, this research focuses on the pluralistic subjects of rural governance, highlights its modernization characteristics, and constructs a measurement index system for the MRGC. This approach provides a new perspective for measurement research focused on rural issues, offering an innovative framework that shifts the focus from transactional affairs to subject-oriented governance capacity assessment.

- (2)

- Prior studies have often overlooked the interrelations among sub-dimensions within the index system. By contrast, this research proceeds from the principles of systems theory, examining rural governance activities within complex economic–social contexts to conduct a statistical interpretation of their social system characteristics. It innovatively designs measurement indicators to quantify the intra-systemic interactions, enabling a more detailed analysis of system elements’ states and thus enhancing the accuracy of MRGC assessment.

- (3)

- In terms of index weighting, this study integrates three weighting principles—variability, correlation, and uncertainty—to design a combined weighting method. On the premise of ensuring that the original measurement ranking remains unchanged, this method effectively corrects the differences caused by a single weighting method while making the measurement scores more discriminative.

6.2. Conclusions

- (1)

- The IIF emerges as a critical determinant of the MRGC. Heterogeneity is prevalent in both SGC and IIF across townships, with relatively small variations in SGC but pronounced disparities in IIF. There is no significant difference in their means, but the variance of the IIF is significantly larger than that of the SGC. Thus, the primary driver of higher MRGC levels is the pulling effect of robust IIF, where subjects form mutually reinforcing, equitably balanced, and structurally rational cooperative relationships. Conversely, the lack of linkages among pluralistic subjects tends to lead to missed rural development opportunities, rendering them incapable of addressing external economic shocks and environmental crises [75].

- (2)

- The SGC of rural subjects in Kang County remains at a medium level, but significant heterogeneity exists among subjects, manifesting as two distinct states: heterogeneous high-level and homogeneous low-level. Notable disparities are observed in the SGC of various subjects: grassroots party organizations, governments, and self-governing organizations exhibit medium-level capabilities, whereas SEOs and villagers demonstrate relatively lower capacities. This indicates that GPOs can play a leading role in rural governance, and the primary-level Party members can effectively play their vanguard and exemplary roles. The government plays an important role in the service, management, and guarantee of public undertakings. AOs can achieve rural self-management, self-education, and self-service, to a certain extent. The villagers have the potential to participate in rural governance, while the capacities of SEOs need to be improved. In terms of the differences in subject capabilities, the governance capability disparities among high-level subjects are significantly greater than those among low-level subjects. This is attributed to villagers’ low educational attainment, insufficient democratic literacy, and ingrained habits, which slow their absorption of modern rural governance knowledge. As a result, passive participation in governance is common. Moreover, population out-migration has exacerbated the loss of highly educated groups, weakening governance participation vitality [76]. As for SEOs, rural financial institutions impose high thresholds and barriers on financial services; policy support features limited coverage and unstable safeguard mechanisms; and development approaches lack effective planning strategies, leading to low economic efficiency. These collectively result in a lack of endogenous motivation for SEOs in rural economic governance [77].

- (3)

- The Inter-Subjective Interaction Force (IIF) in Kang County remains at an intermediate level, with volatility identified as the primary factor influencing IIF levels. Significant disparities exist in the effects of various IIF components, presenting an order of coupling > volatility > abruptness. As the comprehensive IIF index declines from high to low (Figure 6), the degree of variation in volatility is notably higher than that in coupling and abruptness, indicating that the expansion of capability disparities among subjects is the dominant factor driving IIF reduction. Alejandro’s research [78] reaches a similar conclusion: disparities in actors’ capabilities, cognition, and technology are key barriers to cooperation, while effective information exchange can facilitate actors in forming shared goals and enhancing technological proximity.

- (4)

- Rural subjects in resource-endowed areas exhibit higher SGC but face a greater possibility of systemic structural imbalance. In the regional comparison, the SGC of rural subjects in the central region was found to be higher than that in the southern and northern regions, which can be attributed to more balanced governance capabilities among subjects in the central region—or, more specifically, the governance capabilities of SEOs and villagers in this region are significantly higher. The Levene test revealed that there is no homogeneity of variance in the governance capabilities of SEOs across the three regions. The variance of governance capabilities of social and economic organizations in the Central Kang region is significantly higher than that in the other two regions, indicating greater internal differences in levels within the Central Kang region. Under the policy orientation of centering on county seats, promoting new-type urbanization, and coordinating urban–rural development, county seats undertake multiple functions such as population aggregation, resource integration, information circulation, and public service provision [79]. As the location of the county seat, the Central Kang region is more prone to benefiting from the spillover effects of characteristic industry development, human resource aggregation, and basic public services in county construction. However, the scope of its radiating and driving effect is limited, and the towns in the Central Kang region that are not located in county seats have developed relatively slowly. In terms of the IIF, the central Kang region has a lower abruptness score than the other two regions, indicating the possibility of subject structural imbalance. This may give rise to new governance models or cause order chaos, necessitating the establishment of a dynamic monitoring and early warning mechanism and timely adjustment of development strategies.

- (5)

- The obstacle factors affecting the development of MRGC at both the regional and township levels include the coupling nature, volatility, and mutability of inter-subject interactions. From the regional perspective, the North Kang region faces constraints in all three aforementioned interactions; the South Kang region is only constrained in terms of coupling nature and volatility; while the Central Kang region is prominently constrained in mutability, which is consistent with the findings in Table 5. From the township perspective, the operational performance of rural SEOs and village’ information application capabilities also restrict the development of MRGC. The restrictive effects of institutional building in rural governance, human capital, and social security are to a certain extent universal but not strong. Government planning and design, as well as the age structure of Party organization members, have a strong impact within a narrow scope.

- (6)

- This study designed combined weights by integrating three data characteristics: variability, correlation, and uncertainty. The statistical test results show that the ranking of measurement results obtained via the combined weighting method is consistent with that of single weighting methods. Significant differences are found between its measurement scores and those from variability and correlation weighting methods. Furthermore, its standard deviation is larger than that of the three single-characteristic weighting methods. Therefore, besides ensuring that the original measurement ranking remains unchanged, the combined weighting method can effectively correct deviations caused by single weighting methods, as well as enhance the discrimination of measurement scores. Currently, combined weighting methods are increasingly applied to multicriteria decision-making problems in fields such as business economics, environment, and engineering [80].

6.3. Suggestions

- (1)

- In terms of activating subject capabilities, efforts should be made to enhance the information acquisition, analytical decision making, and action implementation capacities of governance subjects [47]. First, led by government departments, data from multiple subjects and departments should be collected and integrated to establish a comprehensive rural governance information and monitoring early warning platform that is publicly disclosed to the public in accordance with the law to break information barriers. Second, all subjects should actively recruit returned college students and migrant workers with rich professional knowledge and strong working capabilities to participate in decision making, combining the advanced technologies possessed by returned personnel with the past experience of local personnel to make scientific decisions. Finally, administrative and market means should be comprehensively used, and measures, such as financial subsidies, financial loans, and project demonstrations, should be adopted to ensure the implementation of subject actions.

- (2)

- In promoting inter-subjective interaction, approaches like goal consensus, communication consultation, and rational allocation should be employed to foster mutual trust and collective action among pluralistic subjects. First, common goals must focus on addressing livelihood issues in rural development and meeting villagers’ aspirations for a better life [45]. Therefore, the priorities of rural governance should lie in infrastructure construction, public service improvement, and resident welfare enhancement [47]. Second, a combination of online and offline approaches should be adopted, utilizing platforms, such as WeChat, Tencent Meeting, and village councils, to facilitate information sharing, collaborative learning, trust-building among pluralistic subjects, and long-term stability of cooperative relationships. Finally, a sound mechanism for shared responsibility and interest allocation should be established: laws and regulations should be formulated to clarify the scope and intensity of subject powers based on their characteristics, responsibilities should be shared according to the magnitude of subject powers, and interests should be distributed in proportion to the shareholdings of subjects in local industries, ensuring the alignment of rights, responsibilities, and interests to stimulate the enthusiasm of subjects for governance participation.

6.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

- (1)

- In terms of the measurement index system, rural governance encompasses a multitude of complex issues. The measurement content of the MRGC should evolve as our understanding of its connotations increases, embodying characteristics of the times. Future research could thoroughly explore the scientific connotations of MRGC under new circumstances and objectives—such as informatization, intelligentization, common prosperity, and urban–rural integration—before designing the measurement index system accordingly. In addition, the object of research on the measurement of rural governance capacity is the level and status of factor input in the process of rural governance. However, good input does not necessarily mean good results [81]. Therefore, future research can shift to a result-oriented perspective and study the effectiveness of rural governance from fields such as rural culture, ecology, and people’s livelihood.

- (2)

- In terms of research scope, this study selected only cross-sectional data from 15 towns in Kang County for analysis, making it difficult to characterize the dynamic changes in MRGC in the temporal dimension. Future research can proceed from two aspects: first, selecting several sample counties for periodic follow-up surveys to analyze the dynamic evolution of MRGC over time; second, attempting to expand the research scope to regional or national panel data to explore the evolutionary paths and differentiation characteristics of provincial-level MRGC in temporal and spatial dimensions.

- (3)

- In terms of research methods, the weight assignment approach prioritized objectivity, mainly adopting combined weights of objective weighting methods. Future studies could incorporate subjective weighting methods into the combined framework and attempt new weighting techniques such as CILOS, IDOCRIW, and FUCOM. In terms of model design, this study constructs a composite index through the linear synthesis of factors based on the assumption that there is a linear relationship between the elements of the governance system. However, the governance system is a complex system, and there may be non-linear relationships between its elements. Future research can conduct in-depth analysis of the mechanisms and influences between elements to further improve the model design.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shi, J.; Yang, X. Sustainable Development Levels and Influence Factors in Rural China Based on Rural Revitalization Strategy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Peng, X.; Li, X.; Lu, M.; Yin, M. Effectiveness in Rural Governance: Influencing Factors and Driving Pathways—Based on 20 Typical Cases of Rural Governance in China. Land 2023, 12, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. Research on National Governance Capability: Literature Review and Research Approach. Social. Stud. 2020, 5, 156–163. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Reevaluation on Korean New Village Movement: Lessons from the Key Stage of Rural Modernization of South Korea. Nanjing J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 2, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgios, C.; Barraí, H. Social Innovation in Rural Governance: A Comparative Case Study across the Marginalised Rural EU. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 99, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A.C.; Gordon, R. Grappling with Governance: Emerging Approaches to Build Community Economies. J. Rural. Stud. 2024, 107, 103242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, V.; Deshkar, S. Transitions towards Sustainable and Resilient Rural Areas in Revitalising India: A Framework for Localising SDGs at Gram Panchayat Level. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annahar, N.; Widianingsih, I.; Muhtar, E.A.; Paskarina, C. The Road to Inclusive Decentralized Village Governance in Indonesia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanets, N.; Hu, Z.; Chen, J. The Evolution and Experience of China’s Rural Governance Reform. Agric. Resour. Econ. Int. Sci. E-J. 2019, 5, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, L. Rural Revitalization of China: A New Framework, Measurement and Forecast. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 89, 101696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Tang, S. The Operational Logic of Rural Grid-Based Governance from the Perspective of Rural Order. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2024, 11, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Firmly Establish and Consciously Practice the Five Development Concepts. Party Build. 2015, 12, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- You, L.; Chen, S. The Historical Changes of China’s Rural Governance Structure from the Perspective of State Governance Ability. Social. Stud. 2014, 6, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P. Fully and Accurately Grasp the General Goal of Deepening the Reform Comprehensively. Soc. Sci. Chin. High. Educ. Inst. 2014, 1, 4–18+157. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.; Xie, D. The Practical Characteristics and Theoretical Innovations of Rural Governance in China in the New Era. Soc. Sci. Front. 2023, 6, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Ding, Z. The Modernization of Rural Governance with Chinese Characteristics: Theoretical Connotations, Evolutionary Logic and Practical Implications. Rural. Econ. 2023, 10, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Gu, R.; Yuan, L. Framework and Index System Design of Rural Governance Digitalization During the 14th Five-Year Plan Period. J. Stat. Inf. 2021, 36, 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Han, P. The Practice Review and Theoretical Reflection on Rural Governance Modernization. J. Northwest A&F Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 20, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitul, Z.; Ilona, D.; Novianti, N. Good Governance in Rural Local Administration. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, T.H. Developing a Regional Governance Index: The Institutional Potential of Rural Regions. J. Rural. Stud. 2014, 35, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, J. Research on Rural Governance Framework from the Perspective of Chinese-Style Modernization. J. Hohai Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2023, 25, 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Li, J. An Evaluation of Rural Governance Modernization Level. J. South China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 21, 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Xia, C. “Five in One” rural governance assessment system. J. South. Agric. 2016, 47, 766–772. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, X.; Pang, Z. Measurement and Spatial Convergence of Chinese Modernization of the Rural Governance. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2024, 45, 88–102. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, J.; Xiang, L. How Village Cadres’ Public Leadership Affect Village Governance Performance: A Chain Mediation Model. J. Manag. 2023, 36, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, Y. Measurement, Regional Difference and Dynamic Evolution of Rural Revitalization Level in China. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2022, 39, 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Xue, R.; Wang, J. Rural Revitalization Evaluation and Promotion Path Based on Village Level: Taking Baiquan, Heilongjiang, China as a Case Study. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 41, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, C. Connotation Analysis and Level Measurement of Good Governance of Villages: A Case of Tianyuan Town in Changning County, Yunnan. J. Nat. Sci. Hunan Norm. Univ. 2023, 46, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.; Zeng, G. Systematicism: Philosophy of Systems Science; World Publishing Corporation: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, X.; Xu, G.; Wang, S. The Technology of Organizational Management: Systems Engineering. In On Systems Engineering; Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press: Shanghai, China, 2007; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B. European Collaboration in Sustainable Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Engineering System Theory; China Astronautic Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B.; Sharman, A. Collaboration in Local Tourism Policymaking. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 392–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.L. The Economic Significance of National Border Effects. Am. Econ. Rev. 2003, 93, 1291–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocker, J. How Do International Trade Barriers Affect Interregional Trade. In Regional and Industrial Development Theories, Models and Empirical Evidence; Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1984; pp. 219–239. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.; Gu, X.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Q.; Jia, G. Spatial Layout Optimization of Rural Settlements Based on the Theory of Safety Resilience. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 271–279. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D. On the Systematicness of Rural Social Governance. Qilu J. 2019, 4, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. Toward Holistic Governance: A Study on Resolving the Compound Fragmentation in Rural Governance. J. Yanbian Party Sch. 2024, 40, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Yang, L.; Han, J. Cracking the Composite Fragmentation of Rural Governance by “Integration of Four Governance”: An Example from Tongxiang City, Zhejiang Province. J. Public Manag. 2023, 20, 142–154+175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Chen, H. Optimization of Efficiency Improvement Mechanism of Multi-Subject Participation in Rural Governance: Grounded in the Micro-Level Case Studies of Three Villages in L County, Shaanxi Province. J. Northwest A&F Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 1–11. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/61.1376.C.20250328.1505.002 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Xiang, L.Y. Resource Dependence, Relationship Structure and Governance Strategy: The Formation of Rural Governance Communities: An Investigation of Typical Villages in Southwest Hubei. J. Public Manag. 2023, 20, 131–141+174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Oriental Press: Beijing, China, 2006; pp. 51–52. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Z.; You, R. Differentiated Demand, Information Flow, and Organizational Cooperation in Resource Dependence. Open Times 2020, 2, 180–192+9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zeng, J.; Si, W. Construction of Rural Revitalization Symbiotic System and Stability Governance Mechanism. J. Sichuan Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 50, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F. Rural Social Governance Community: Conceptual Interpretation and Practical Pathways: Based on the Context of Rural Revitalization. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2025, 3, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. Modernization of Municipal-Level Social Governance: Internal Logic and Implementation Pathways. Theor. Explor. 2020, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.; Zhang, Y. Complex Adaptive Governance of Rural Environments: Theoretical Interpretation, Operational Mechanisms and Implementation Strategies. Issues Agric. Econ. 2025, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Ren, Z.; Du, Q.; Han, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, R. Definition, Notation and Evolving: Literature Review of Community. Sci. Sci. Manag. S. T. 2010, 31, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Stoker, G. Governance as Theory: Five Propositions. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2019, 36, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Ming, Z. The Logical Connotation and the Shaping Path of the Social Governance Community. J. South-Cent. Univ. Natl. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2021, 41, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wang, C.; Su, M. Multiple Desirability Synergies in Rural Governance: A Multiple Case Study Based from the Perspective of Tackling Institutional Complexity. China Rural. Surv. 2023, 6, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Guo, Z. Exploration on the Macroscopic Physical Meaning of Entropy. Sci. Sin. (Technol.) 2010, 40, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Peng, X. Engineering Thermodynamics; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2011; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Lv, Z.; Zhou, X. Overall Governance and Rural Resilience Development: A “Four-Dimensional” Theoretical Analysis Framework. Soc. Sci. Res. 2024, 4, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Z.; Zhang, A.; Wang, S.; Bai, Y. Designing Principles and Constructing Processes of the Comprehensive Evaluation Indicator System. Sci. Res. Manag. 2017, 38, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Huang, Y. From “Responsibility Isomorphism” to Governmental Responsibility System: The Generation and Cracking of the Phenomenon Overburden at the Grassroots. Chin. Public Adm. 2024, 4, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z. Evolution of Background, Transformation Trends and Effective Paths of Rural Governance in China. Theory J. 2020, 3, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, L.; Wan, M. Research on the Organizational Innovation of Rural Collective Economic Organizations under the Guidance of Rural Revitalization Strategy. Soc. Sci. Guangxi 2021, 3, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L. Rural Governance Effectiveness Driven by Digital Governance: Challenges, Theoretical Framework, and Policy Optimization. Issues Agric. Econ. 2024, 6, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Chen, M. Study on the Cultivation of Peasants’ Consultation Ability in Rural Social Governance—A Case Study of Beidongyuan Village in Gongcheng County, Guangxi. J. Guangxi Minzu Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 38, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sharma, P.N.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Liengaard, B.D. The Shortcomings of Equal Weights Estimation and the Composite Equivalence Index in PLS-SEM. Eur. J. Mark. 2024, 58, 30–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Dang, X.; Liu, P.; Gao, G.; Zhu, H.; Shi, J.; Zhang, Q.; Bol, R.; Zhang, P.; Lynch, I.; et al. Screening Uncalibrated Priority Pollutants by Improved AHP-CRITIC Method at Development Land. Environ. Int. 2025, 202, 109650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Du, M.; Yan, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Kou, Y. Coupling Coordination Degree Analysis and Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity between Water Ecosystem Service Value and Water System in Yellow River Basin Cities. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 79, 102440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhao, L. Synergistic Evolution Mechanisms for Improving Open Government Data Ecosystems Using the Haken Model. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2024, 46, 101284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Sun, C.; Wang, X. Social, Economic and Resource Environment Composite System of Co-Evolution: A Case Study of Dalian. Syst. Eng. Theory Pract. 2013, 33, 413–419. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J. Modeling and Simulation of the Market Fluctuations by the Finite Range Contact Systems. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2010, 18, 910–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomal, M. Evaluation of Coupling Coordination Degree and Convergence Behaviour of Local Development: A Spatiotemporal Analysis of All Polish Municipalities over the Period 2003–2019. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 71, 102992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Yu, J.; Dai, R. A New Field of Science: An Open Complex Giant System and Its Methodology. Chin. J. Nat. 1990, 1, 3–10+64. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Pan, W. Research on Individual Weight, Overall Weight and Pseudo Weight Problem in Academic Evaluation—Taking Linear Evaluation and JCR Economic Journal Evaluation as Examples. J. Intell. 2022, 41, 163–169+198. [Google Scholar]

- Shangguan, C.; Ma, R.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tian, M.; Teng, Y.; Jing, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Li, K.; et al. Assessment of Grain Production Levels and Analysis of Obstacle Factors in China: A Sustainable, Stable and Green Perspective. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1631845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Tao, S.; Hu, H.; Sun, M.; Wang, M. Spatio-Temporal Evaluation of Ecological Security of Cultivated Land in China Based on DPSIR-Entropy Weight TOPSIS Model and Analysis of Obstacle Factors. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Ji, M. Spatial-Temporal Differentiation and Influencing Factors of Rural Education Development in China: A Systems Perspective. Systems 2024, 12, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainio, O.; Teuho, J.; Klén, R. Evaluation Metrics and Statistical Tests for Machine Learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, N.; Sullivan, A.; Chen, S.T.; Qin, X. Changing Collaborative Networks and Transitions in Rural Sustainable Development: Qualitative Lessons from Three Villages in China. Ecol. Soc. 2023, 28, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Value Interpretation, Realistic Constraints and Promotion Strategies of Rural Governance from the Perspective of Rural Revitalization. Agric. Econ. 2024, 8, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, F. The Theoretical Connotation, Realistic Dilemma and Practical Path of New Rural Collective Economy. J. Guizhou Univ. Financ. Econ. 2024, 3, 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Torres, A. Asymmetry of Stakeholders’ Perceptions as an Obstacle for Collaboration in Inter-Organizational Projects: The Case of Medicine Traceability Projects. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2019, 13, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Giving Play to the Connecting Role of County Towns in Urban-Rural Integration. New Urban. 2025, 1, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Ayan, B.; Abacıoğlu, S.; Basilio, M.P. A Comprehensive Review of the Novel Weighting Methods for Multi-Criteria Decision-Making. Information 2023, 14, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shi, L.; Xu, A. Probe into the Assessment Indicator System on High-Quality Development. Stat. Res. 2019, 36, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension | Objects | Features | Indicator | Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGC | GPO | Proportion of administrative villages with Party organizations * | + | |

| Proportion of village Party secretaries doubling as village directors | + | |||

| Proportion of young Party members | + | |||

| Percentage of active Party members | + | |||

| GOV | Participation rate of social endowment insurance | + | ||

| Coverage rate of convenient service centers * | + | |||

| Coverage rate of the Rural Revitalization Plan | + | |||

| Residents’ sense of security | + | |||

| AO | Average years of education for village directors | + | ||

| Turnout in village committee elections | + | |||

| Degree of village harmony | + | |||

| SEO | Degree of improvement of the collective economic system | + | ||

| Proportion of participation in the collective economy and cooperative | + | |||

| Collective economic annual income | + | |||

| Villagers | Percentage of villagers with a college degree or above | + | ||

| Degree of villagers’ compliance with rules | + | |||

| Percentage of households with computers | + | |||

| IIF | Coupling coefficient | + | ||

| Fluctuation | Volatility coefficient | − | ||

| Mutability coefficient | − |

| Regions | Indicators | MRGC | SGC | IIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The North | Average | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.50 |

| Range | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.37 | |

| The Central | Average | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.55 |

| Range | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.52 | |

| The South | Average | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.50 |

| Range | 0.36 | 0.16 | 0.64 | |

| Kruskal–Wallis Test | — | 0.848 | 0.285 | 0.522 |

| Bartlett Test | — | 0.331 | 1.336 | 0.974 |

| Indicators | Combination Weights | Variability Weights | Correlation Weights | Uncertainty Weights | Three Weights Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.046 | |

| 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.010 | |

| 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 0.055 | |

| 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.26 | 0.39 | 0.097 | |

| 0.55 | 0.33 | 0.57 | 0.37 | 0.255 | |

| 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.079 | |

| 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.040 | |

| 0.46 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.031 | |

| 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.009 | |

| 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0.22 | 0.122 | |

| 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.09 | 0.149 | |

| 0.78 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.69 | 0.271 | |

| 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.012 | |

| 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.20 | 0.049 | |

| 0.54 | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.45 | 0.037 |

| Township | Combination Weights | Variability Weights | Correlation Weights | Uncertainty Weights | The Range of SGC Under Three Weights | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scores | Rank | Scores | Rank | Scores | Rank | Scores | Rank | ||

| Anmenkou | 0.480 | 6 | 0.517 | 5 | 0.550 | 4 | 0.480 | 7 | 0.070 |

| Baiyang | 0.393 | 11 | 0.423 | 13 | 0.454 | 14 | 0.402 | 12 | 0.051 |

| Chengguan | 0.519 | 4 | 0.510 | 7 | 0.506 | 8 | 0.524 | 3 | 0.018 |

| Dannanyu | 0.499 | 5 | 0.559 | 2 | 0.591 | 3 | 0.531 | 2 | 0.060 |

| Douba | 0.634 | 1 | 0.621 | 1 | 0.654 | 1 | 0.645 | 1 | 0.033 |

| Lianghe | 0.528 | 3 | 0.534 | 3 | 0.603 | 2 | 0.510 | 4 | 0.093 |

| Miba | 0.477 | 7 | 0.514 | 6 | 0.541 | 6 | 0.486 | 6 | 0.055 |

| Nianba | 0.358 | 13 | 0.387 | 14 | 0.459 | 11 | 0.355 | 14 | 0.104 |

| Pingluo | 0.469 | 8 | 0.484 | 9 | 0.532 | 7 | 0.465 | 9 | 0.068 |

| Tongqian | 0.363 | 12 | 0.465 | 10 | 0.457 | 12 | 0.415 | 11 | 0.049 |

| Wangba | 0.395 | 10 | 0.461 | 11 | 0.467 | 10 | 0.420 | 10 | 0.047 |

| Wangguan | 0.540 | 2 | 0.523 | 4 | 0.547 | 5 | 0.501 | 5 | 0.046 |

| Yangba | 0.447 | 9 | 0.494 | 8 | 0.494 | 9 | 0.472 | 8 | 0.023 |

| Changba | 0.230 | 15 | 0.235 | 15 | 0.224 | 15 | 0.238 | 15 | 0.014 |

| Zhoujiaba | 0.355 | 14 | 0.448 | 12 | 0.456 | 13 | 0.394 | 13 | 0.062 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.099 | 0.088 | 0.098 | 0.093 | |||||

| Shapiro–Wilk Test | 0.970 | 0.892 | 0.867 * | 0.954 | |||||

| Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test | — | 2.670 ** | 3.181 ** | 1.822 | |||||

| Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance | 0.949 *** | ||||||||

| Regions | Indicators | SGC | GPO | GOV | AO | SEO | VLG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The North | Average | 0.43 | 0.58 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.16 | 0.35 |

| Range | 0.31 | 0.48 | 0.70 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.58 | |

| The Central | Average | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.42 |

| Range | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.81 | 0.39 | |

| The South | Average | 0.44 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 0.40 | 0.19 | 0.27 |

| Range | 0.16 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.45 | |

| Kruskal–Wallis Test | — | 0.285 | 5.76 | 1.027 | 2.943 | 2.361 | 3.018 |

| Levene Test | — | 1.336 | 0.771 | 0.258 | 0.585 | 23.002 *** | 0.036 |

| Regions | Indicators | IIF | Coupling | Volatility | Mutability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The North | Average | 0.50 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 0.44 |

| Range | 0.37 | 0.55 | 0.40 | 0.67 | |

| The Central | Average | 0.55 | 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.24 |

| Range | 0.52 | 0.72 | 0.66 | 0.62 | |

| The South | Average | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.60 |

| Range | 0.64 | 0.78 | 0.56 | 0.60 | |

| Kruskal–Wallis Test | — | 0.522 | 1.710 | 1.815 | 3.188 |

| Bartlett Test | — | 1.590 | 1.066 | 1.632 | 0.058 |

| Regions | Township | Ranking of Obstacle Degrees | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| The North | Dannanyu | X6 (20.11) | X7 (18.07) | X43 (15.30) | X8 (10.55) | X53 (9.92) |

| Miba | X7 (20.80) | X6 (20.32) | X8 (14.95) | X43 (11.95) | X53 (6.42) | |

| Pingluo | X8 (22.10) | X7 (17.12) | X43 (9.93) | X53 (8.74) | X6 (8.55) | |

| Wangguan | X8 (18.65) | X6 (17.26) | X43 (16.41) | X7 (13.71) | X12 (5.05) | |

| Changba | X8 (23.01) | X7 (14.01) | X43 (10.32) | X6 (8.60) | X22 (7.13) | |

| Zhoujiaba | X43 (15.52) | X8 (13.23) | X7 (12.07) | X22 (10.68) | X53 (10.42) | |

| The Central | Chengguan | X8 (33.54) | X7 (8.95) | X53 (8.73) | X22 (7.47) | X32 (6.53) |

| Douba | X8 (42.80) | X53 (14.96) | X22 (6.29) | X13 (6.07) | X51 (6.00) | |

| Nianba | X7 (15.91) | X43 (14.98) | X8 (12.36) | X6 (8.28) | X53 (8.07) | |

| Wangba | X8 (23.84) | X6 (17.09) | X7 (15.73) | X43 (10.96) | X22 (6.18) | |

| The South | Anmenkou | X7 (19.98) | X43 (16.79) | X53 (12.48) | X6 (9.81) | X32 (8.26) |

| Baiyang | X6 (22.71) | X7 (22.71) | X8 (13.19) | X43 (10.18) | X53 (7.36) | |

| Lianghe | X7 (20.71) | X8 (18.29) | X6 (17.62) | X43 (14.34) | X53 (7.61) | |

| Tongqian | X7 (16.40) | X43 (14.65) | X22 (11.47) | X53 (10.84) | X8 (9.49) | |

| Yangba | X8 (18.26) | X7 (16.39) | X43 (12.69) | X6 (11.85) | X32 (8.89) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

You, J.; Pang, Z.; Niu, X.; Zhang, Y. Measurement of the Modernization of Rural Governance Capacity: A Systematic Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167464

You J, Pang Z, Niu X, Zhang Y. Measurement of the Modernization of Rural Governance Capacity: A Systematic Perspective. Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167464

Chicago/Turabian StyleYou, Jingchen, Zhiqiang Pang, Xijuan Niu, and Yize Zhang. 2025. "Measurement of the Modernization of Rural Governance Capacity: A Systematic Perspective" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167464

APA StyleYou, J., Pang, Z., Niu, X., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Measurement of the Modernization of Rural Governance Capacity: A Systematic Perspective. Sustainability, 17(16), 7464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167464