Non-Monotone Carbon Tax Preferences and Rebate-Earmarking Synergies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Method

3.1. The Survey

3.1.1. Type of Tax

3.1.2. General Questions and Participant Information

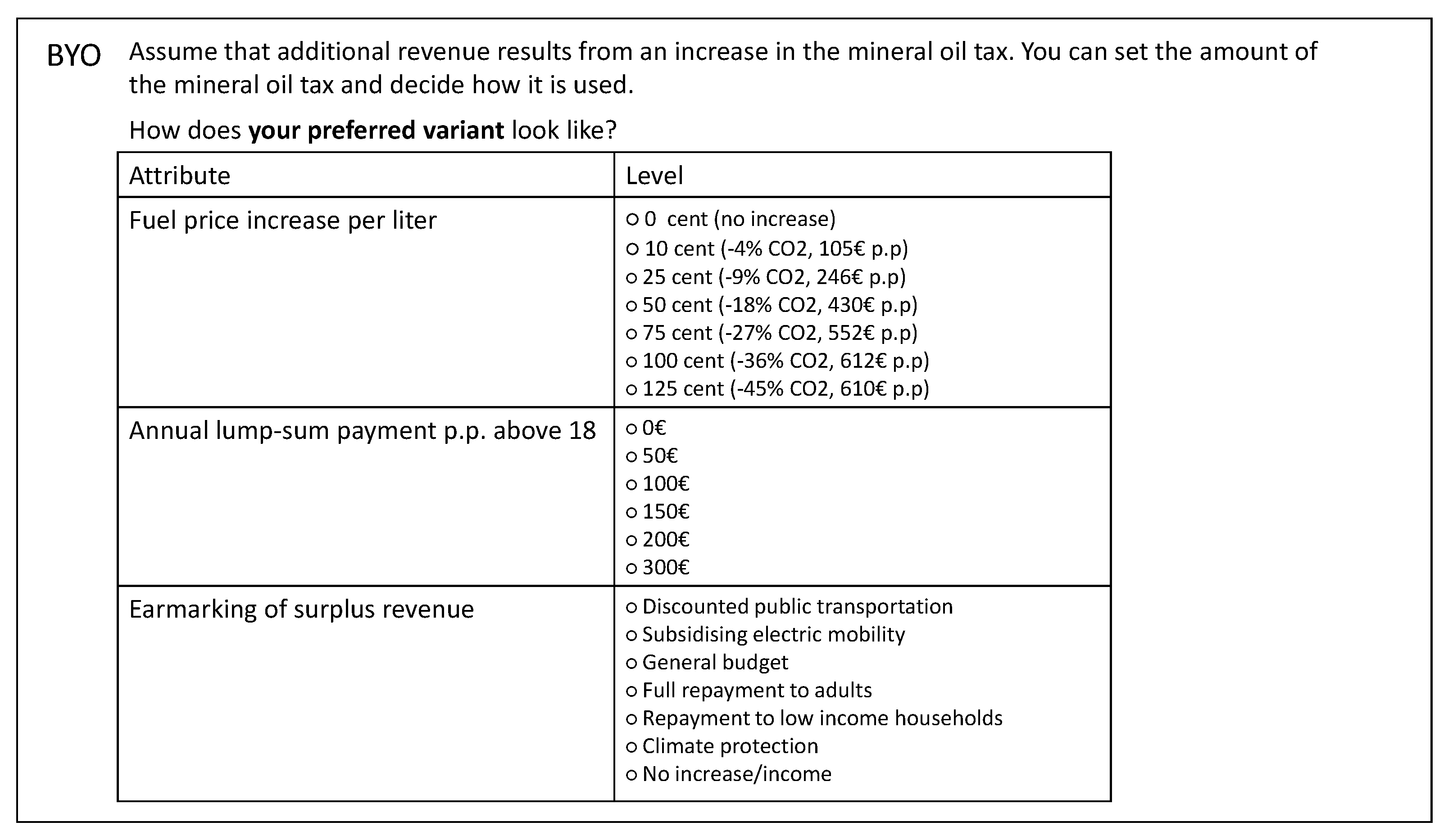

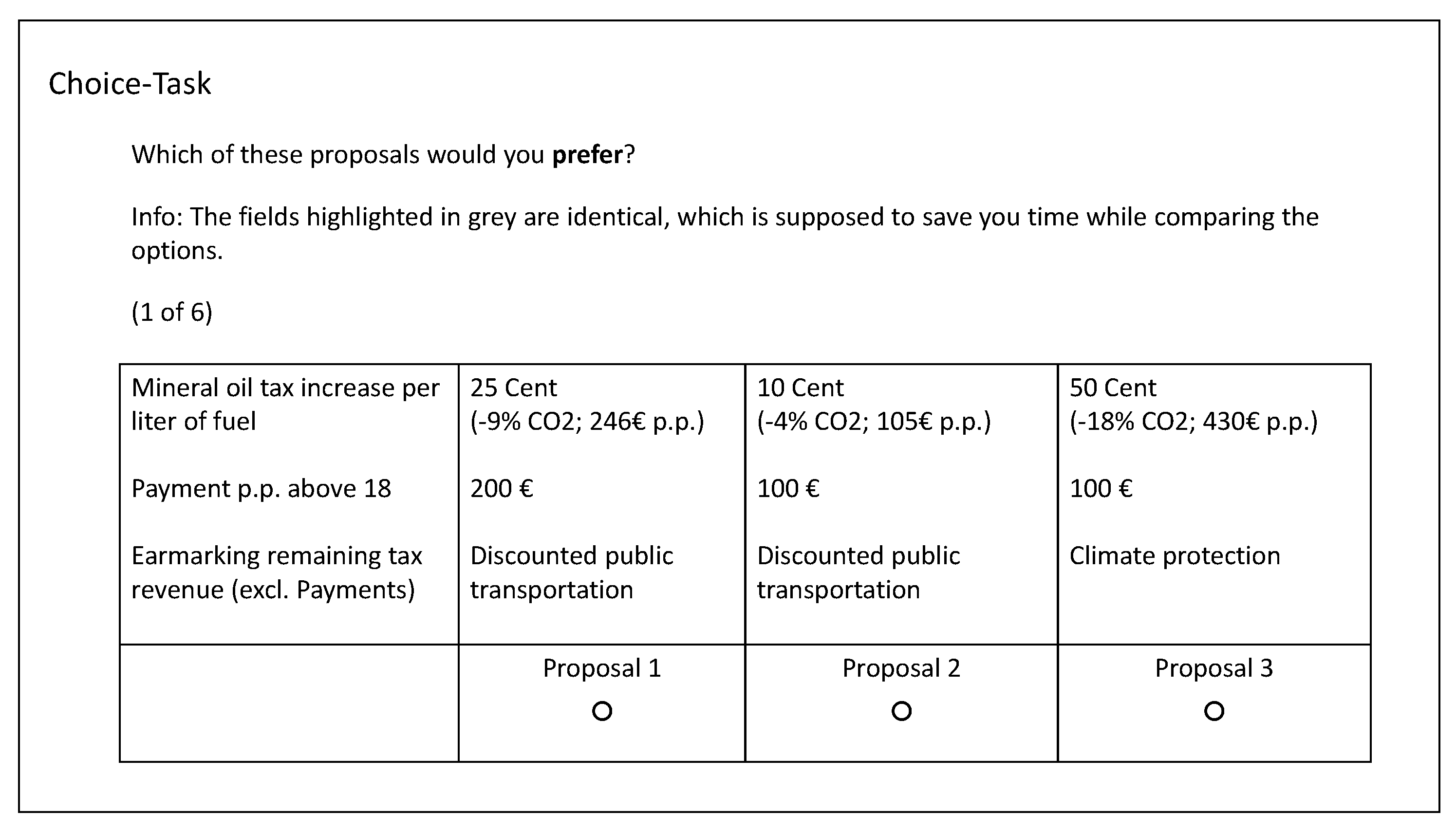

3.2. Adaptive Choice Based Conjoint

3.2.1. Attributes

3.2.2. Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Econometrics

4.1.1. Estimating Part-Worth Utilities

4.1.2. Calculating Attribute Importances

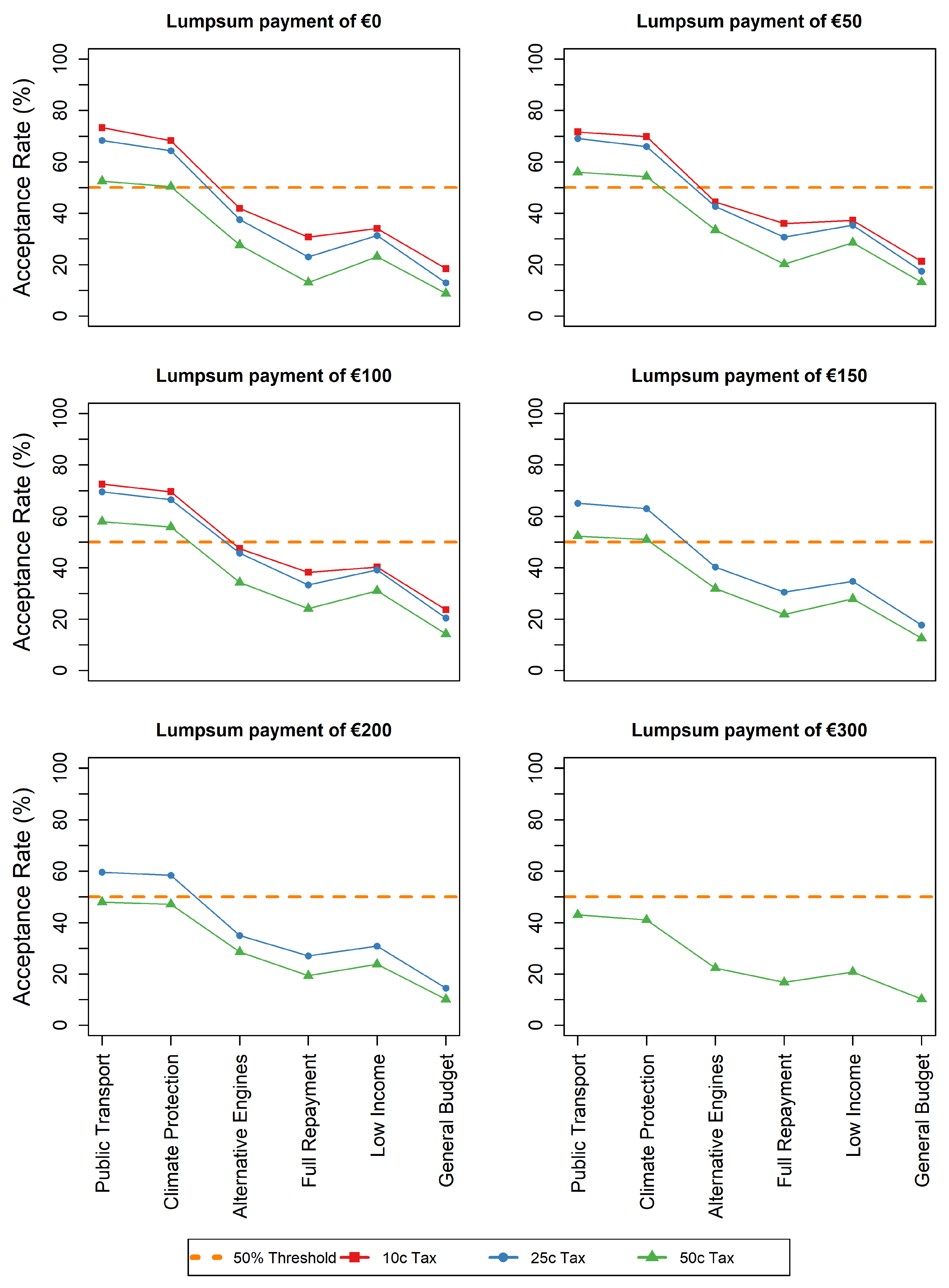

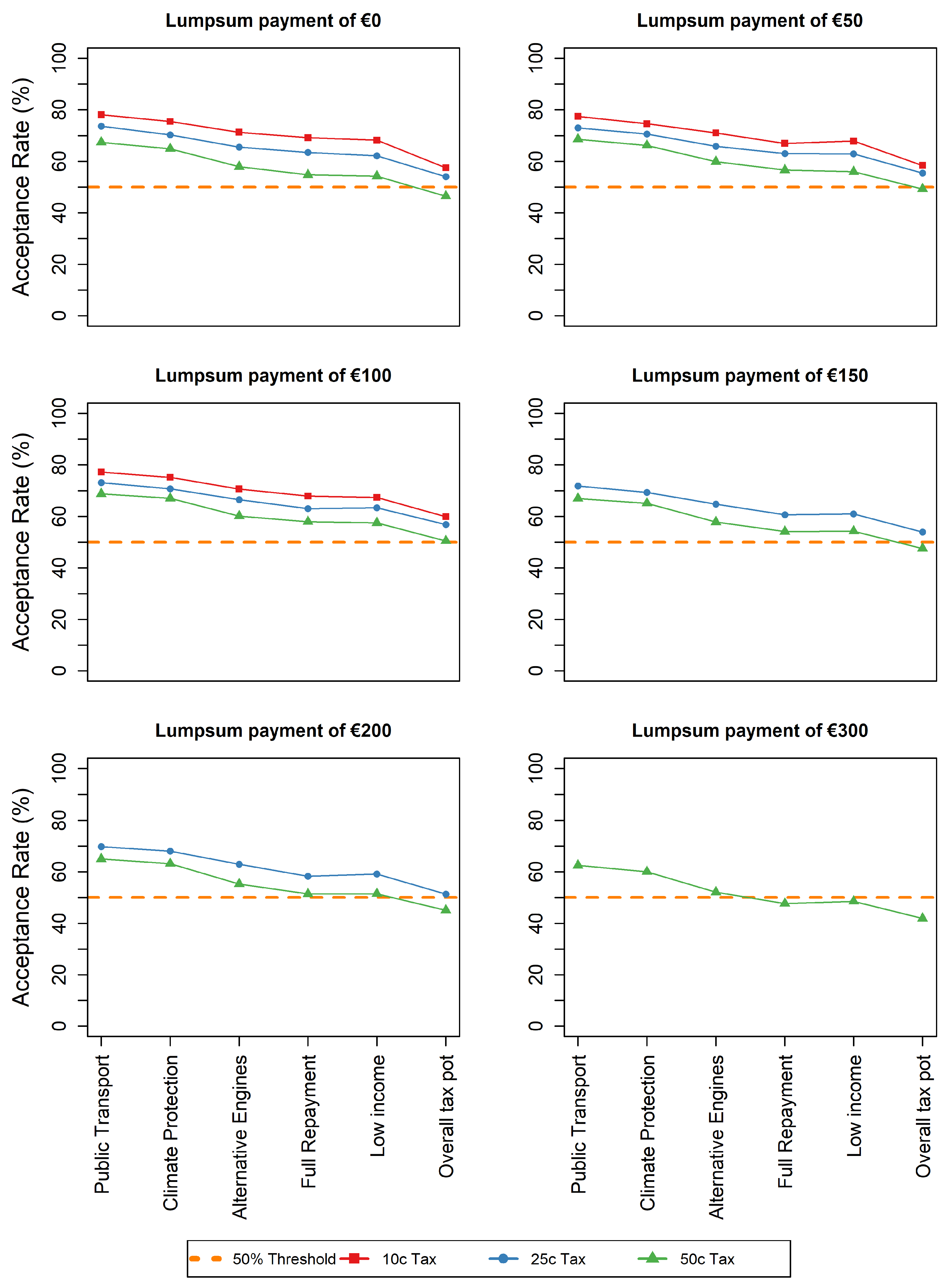

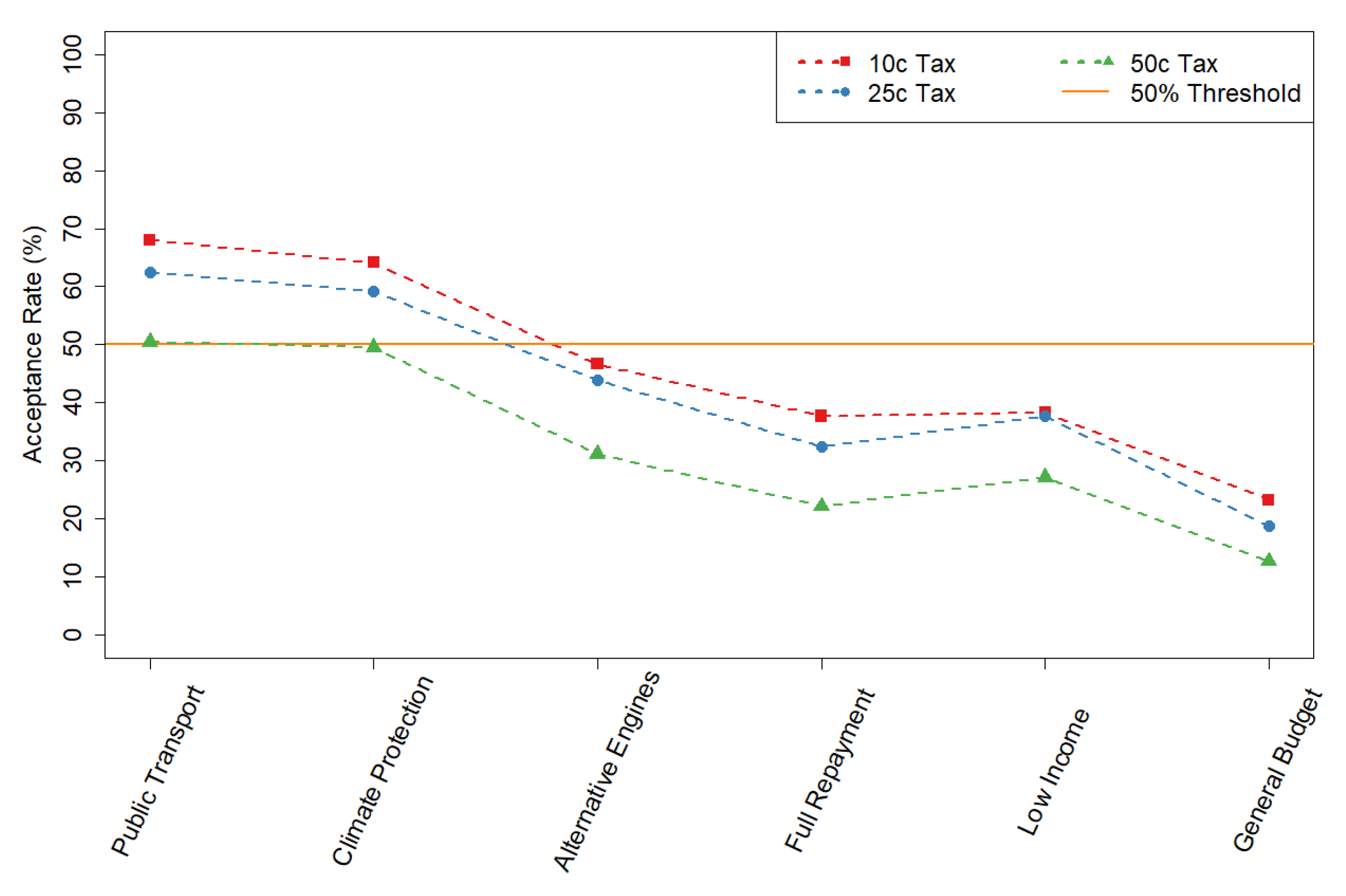

4.1.3. Simulating Acceptance Rates

4.1.4. Weightings

4.2. Build-Your-Own (BYO)

4.3. Part-Worth Utilities

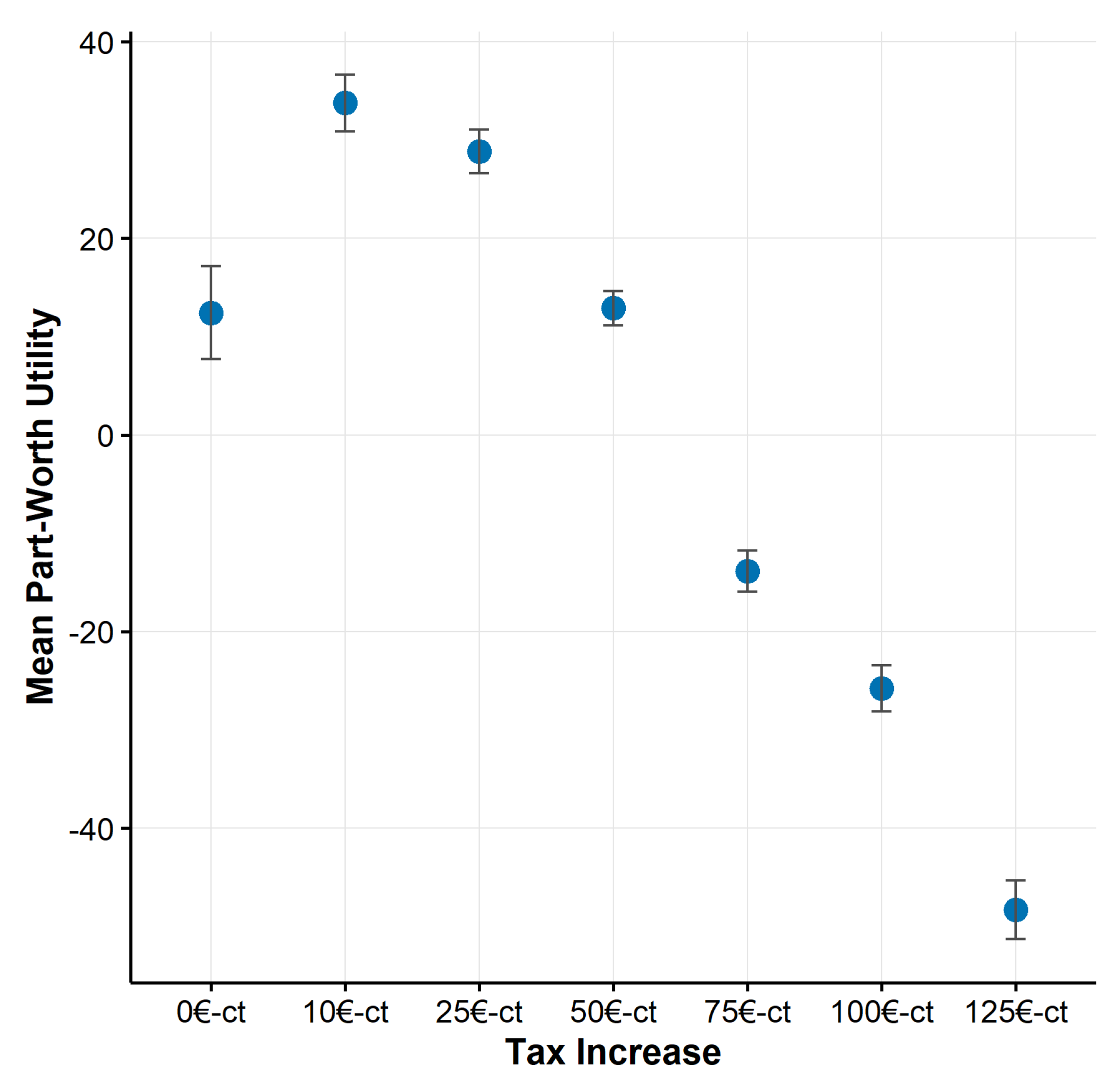

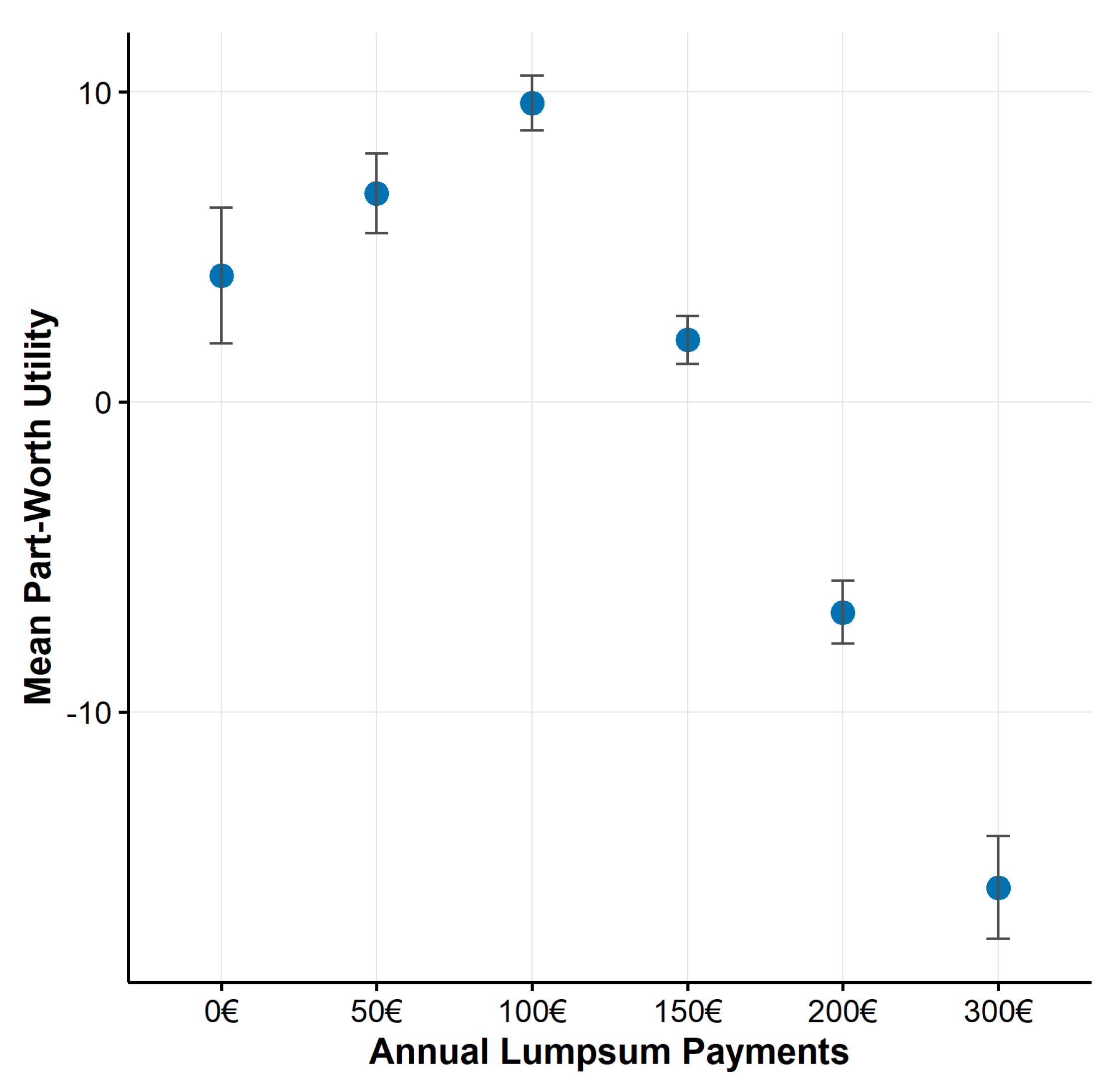

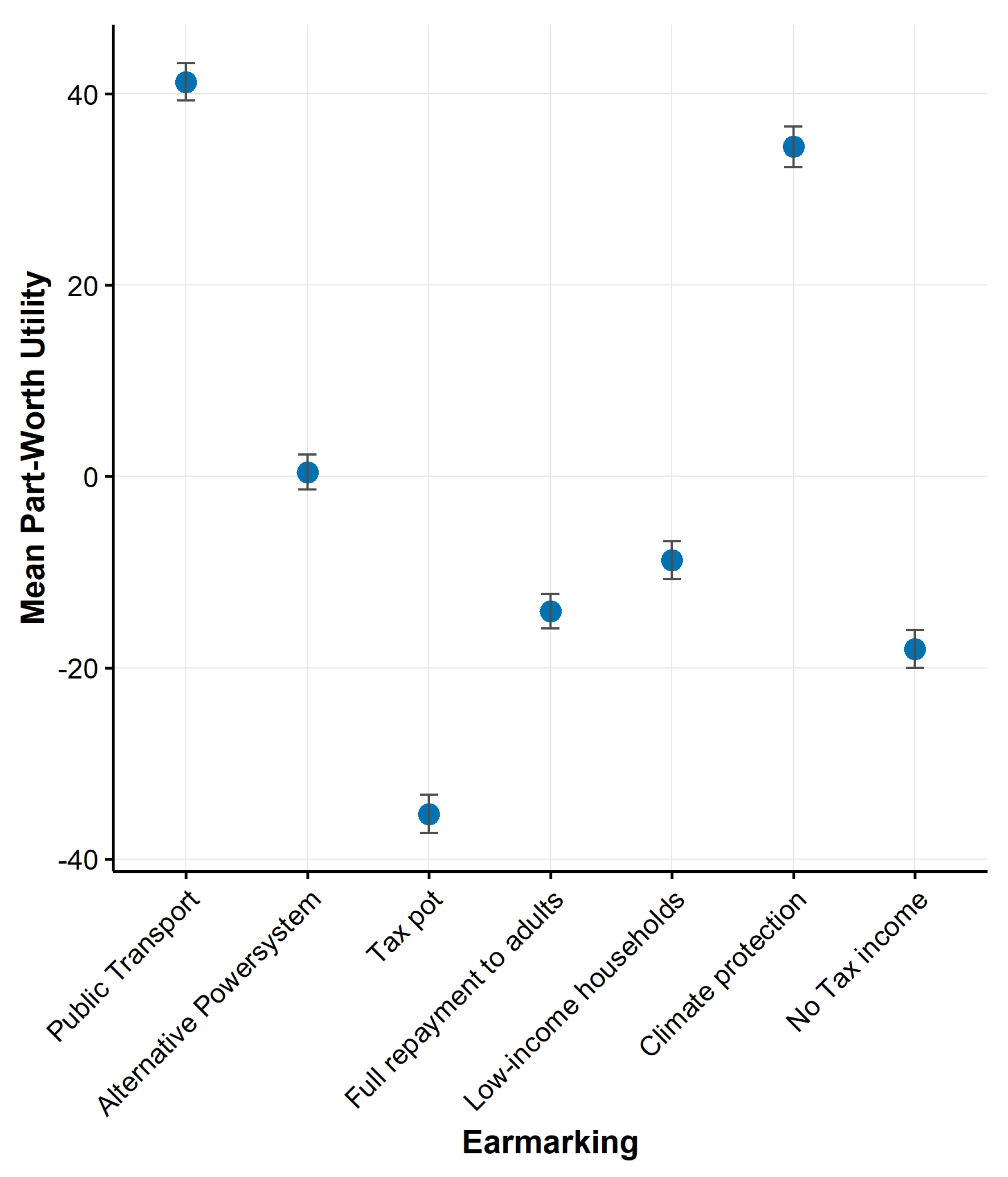

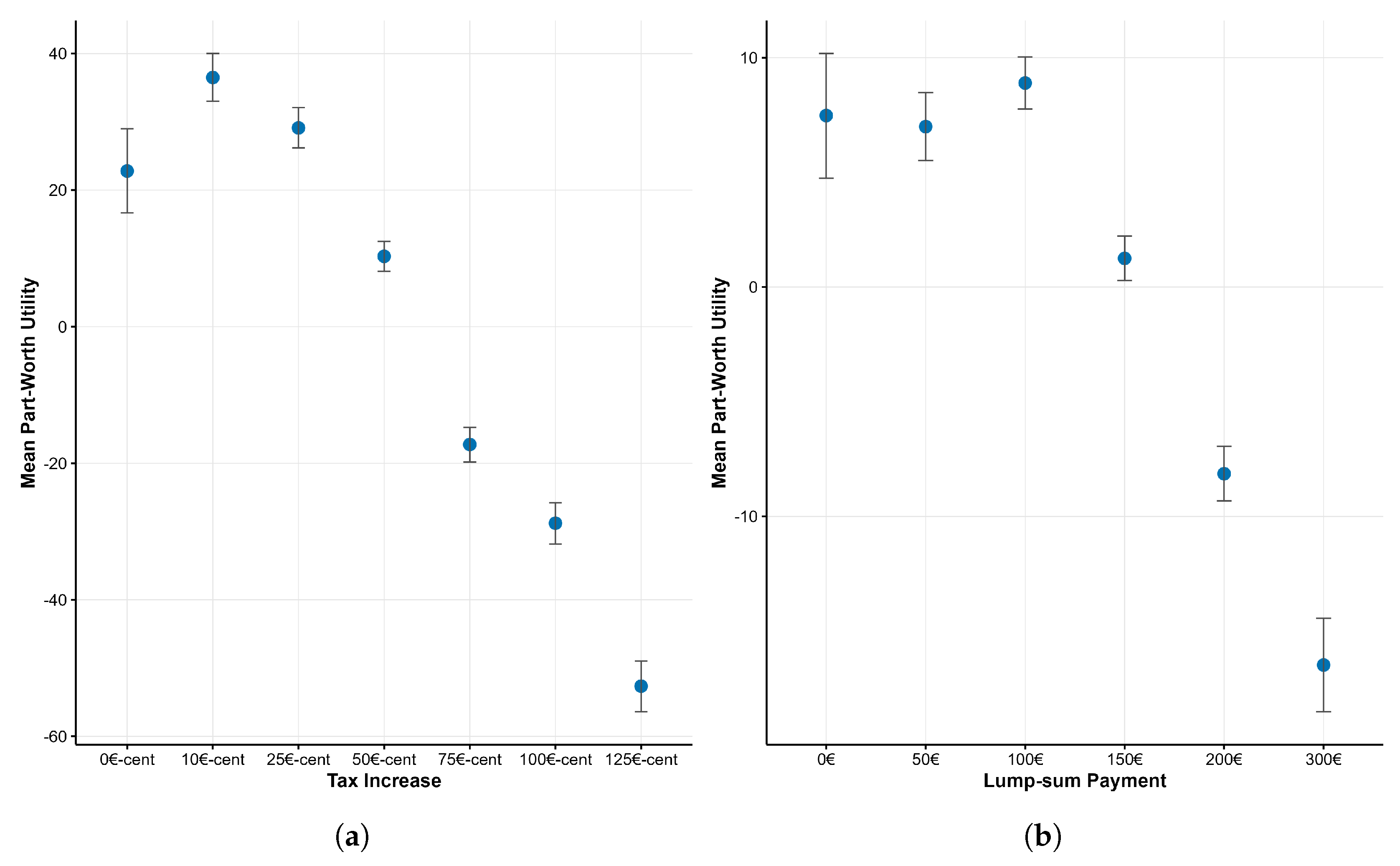

4.3.1. Non-Monotonicity and Mean Preferences

4.3.2. Heterogeneity

4.4. Attribute Importances

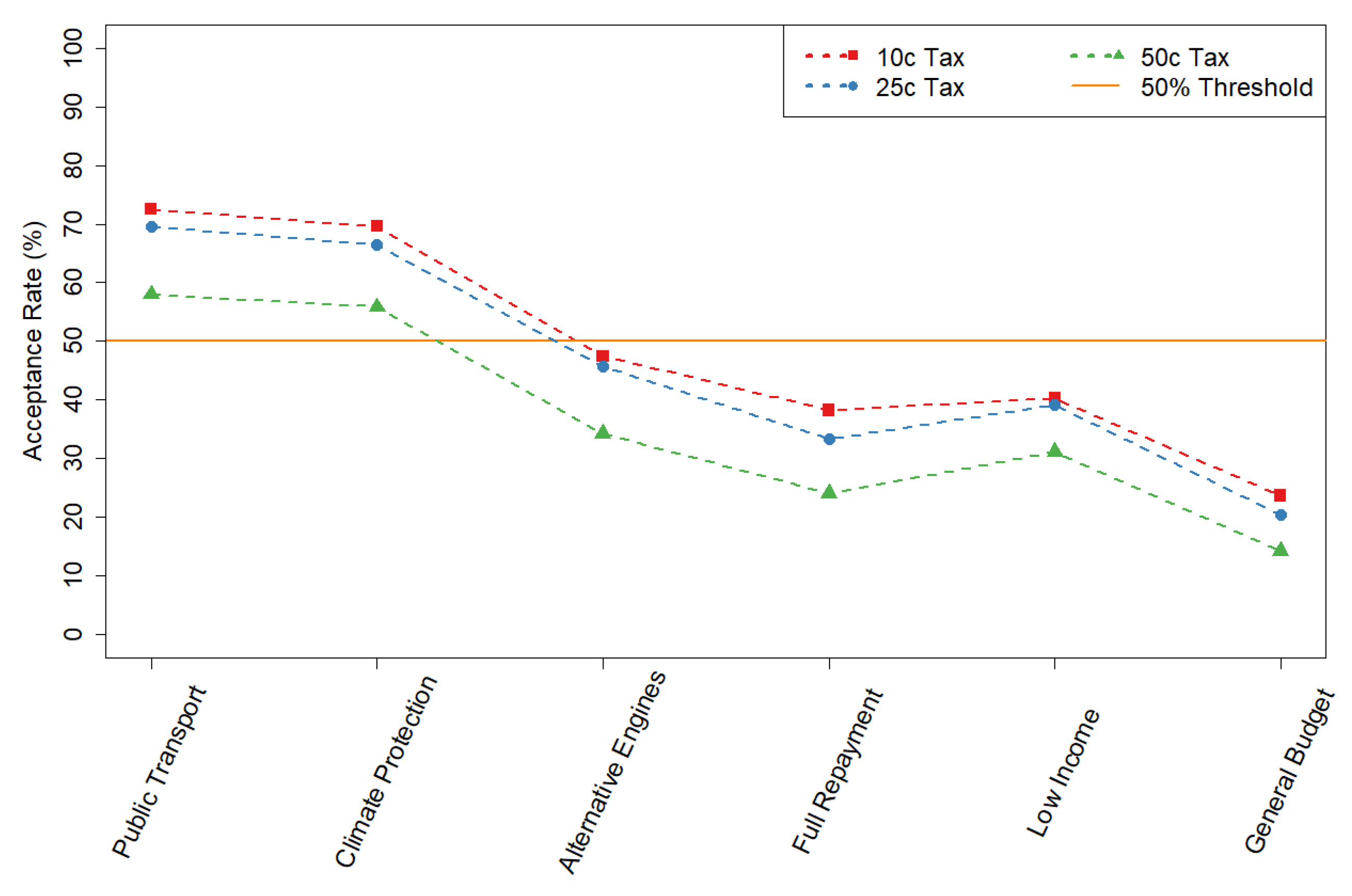

4.5. Tax Reform Acceptance Rates

5. Discussion

5.1. Robustness

5.2. Empirical Implications

5.3. Policy Implications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACBC | Adaptive Choice-Based Conjoint |

| WTP | Willingness-to-pay |

| DCE | Discrete Choice Experiment |

| BYO | Built-Your-Own |

| MNL | Multinomial Logit |

Appendix A

References

- Baumol, W.J.; Oates, W.E. The Theory of Environmental Policy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, J.K. Carbon Pricing: Effectiveness and Equity. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalensee, R.; Stavins, R.N. Lessons Learned from Three Decades of Experience with Cap and Trade. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2017, 11, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J.J. Carbon Taxes and CO2 Emissions: Sweden as a Case Study. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2019, 11, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechezleprêtre, A.; Nachtigall, D.; Venmans, F. The joint impact of the European Union emissions trading system on carbon emissions and economic performance. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2023, 118, 102758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenert, D.; Mattauch, L. How to make a carbon tax reform progressive: The role of subsistence consumption. Econ. Lett. 2016, 138, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, M.; Sommer, M.; Kratena, K.; Kletzan-Slamanig, D.; Kettner-Marx, C. CO2 taxes, equity and the double dividend—Macroeconomic model simulations for Austria. Energy Policy 2019, 126, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2022. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/37455 (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Fairbrother, M. Public opinion about climate policies: A review and call for more studies of what people want. PLoS Clim. 2022, 1, e0000030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, A.A. Does Protest Behavior Mediate the Effects of Public Opinion on National Environmental Policies? A Simple Question and a Complex Answer. Int. J. Sociol. 2008, 38, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadelmann-Steffen, I.; Dermont, C. The unpopularity of incentive-based instruments: What improves the cost–benefit ratio? Public Choice 2018, 175, 37–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildenberger, M.; Lachapelle, E.; Harrison, K.; Stadelmann-Steffen, I. Limited evidence that carbon tax rebates have increased public support for carbon pricing. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildenberger, M.; Lachapelle, E.; Harrison, K.; Stadelmann-Steffen, I. Limited impacts of carbon tax rebate programmes on public support for carbon pricing. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fremstad, A.; Mildenberger, M.; Paul, M.; Stadelmann-Steffen, I. The role of rebates in public support for carbon taxes. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 084040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carattini, S.; Kallbekken, S.; Orlov, A. How to win public support for a global carbon tax. Nature 2019, 565, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreyer, S.J.; Walker, I. Acceptance and support of the Australian carbon policy. Soc. Justice Res. 2013, 26, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umit, R.; Schaffer, L.M. Attitudes towards carbon taxes across Europe: The role of perceived uncertainty and self-interest. Energy Policy 2020, 140, 111385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotaris, L.; Danielis, R. The willingness to pay for a carbon tax in Italy. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 67, 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Toyohara, A.; Li, Y.; Zhou, W. Willingness to pay for carbon tax in Japan. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 52, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carattini, S.; Baranzini, A.; Thalmann, P.; Varone, F.; Vöhringer, F. Green Taxes in a Post-Paris World: Are Millions of Nays Inevitable? Environ. Resour. Econ. 2017, 68, 97–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerle, M.; Best, R.; Crosby, P. Public acceptance of carbon taxes in Australia. Energy Econ. 2021, 101, 105420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M. Willingness to pay for carbon tax: A study of Indian road passenger transport. Transp. Policy 2016, 45, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastis, S.A.; Mattas, K. Income elasticity of willingness-to-pay for a carbon tax in Greece. Int. J. Glob. Warm. 2018, 14, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, I.; Drews, S.; van den Bergh, J. Carbon pricing—Perceived strengths, weaknesses and knowledge gaps according to a global expert survey. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 024014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, S.; Mattauch, L.; Pahle, M. Supporting carbon taxes: The role of fairness. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 195, 107359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sælen, H.; Kallbekken, S. A choice experiment on fuel taxation and earmarking in Norway. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 2181–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammar, H.; Jagers, S.C. Can trust in politicians explain individuals’ support for climate policy? The case of CO2 tax. Clim. Policy 2006, 5, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranzini, A.; Carattini, S. Effectiveness, earmarking and labeling: Testing the acceptability of carbon taxes with survey data. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2017, 19, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.O.; Hall, D.; Sauer, J.; Buchenrieder, G. Are carbon pricing policies on a path to failure in resource-dependent economies? A willingness-to-pay case study of Canada. Energy Policy 2022, 162, 112805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallbekken, S.; Kroll, S.; Cherry, T.L. Do you not like Pigou, or do you not understand him? Tax aversion and revenue recycling in the lab. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2011, 62, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiser-McGrath, L.F.; Bernauer, T. Could revenue recycling make effective carbon taxation politically feasible? Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestre-Andrés, S.; Drews, S.; Savin, I.; van den Bergh, J. Carbon tax acceptability with information provision and mixed revenue uses. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malerba, D.; Never, B.; Fesenfeld, L.; Fuhrmann-Riebel, H.; Kuhn, S. On the acceptance of high carbon taxes in low- and middle-income countries: A conjoint survey experiment. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 094014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevrek, Z.; Uyduranoglu, A. Public preferences for carbon tax attributes. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 118, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrez, J. Public acceptability of carbon pricing: Unravelling the impact of revenue recycling. Clim. Policy 2024, 24, 1323–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkowska, W.; Frank, M.; Kluge, J.; Ziefle, M. How Do We Move towards a Greener and Socially Equitable Future? Identifying the Trade-Offs of Accepted CO2 Pricing Revenues in Germany. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistik Austria 2023. Bevölkerung Nach Alter und Geschlecht Seit 1869. Volkszählungen 1869 bis 2001, Registerzählung 2011 und 2021; Gebietsstand 2021. Available online: https://www.statistik.at/statistiken/bevoelkerung-und-soziales/bevoelkerung/bevoelkerungsstand/bevoelkerung-nach-alter/geschlecht (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Statistik Austria. Zensus Volkszählung 2021: Ergebnisse zur Bevölkerung aus der Registerzählung. Available online: https://www.statistik.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Zensus-VZ-2021.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Eurostat. European Union—Statistics on Income and Living Conditions. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/203647/203704/EU+SILC+DOI+2020v1.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Kettner, C.; Loretz, S.; Schratzenstaller, M. Steuerreform 2022/2024–Maßnahmenüberblick und erste Einschätzung. WIFO Monatsberichte Mon. Rep. 2021, 94, 815–827. Available online: https://www.wifo.ac.at/publication/pid/13773180 (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Pearce, A.; Harrison, M.; Watson, V.; Street, D.J.; Howard, K.; Bansback, N.; Bryan, S. Respondent understanding in discrete choice experiments: A scoping review. Patient 2021, 14, 17–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labandeira, X.; Labeaga, J.M.; López-Otero, X. A meta-analysis on the price elasticity of energy demand. Energy Policy 2017, 102, 549–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orme, B.K. Getting Started with Conjoint Analysis: Strategies for Product Design and Pricing Research, 4th ed.; Research Publishers LLC: Manhattan Beach, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, B.M.; Baier, D. Adaptive CBC: Are the benefits justifying its additional efforts compared to CBC? Arch. Data Sci. Ser. A 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M.; Hovemann, G. Consumer preferences for circular outdoor sporting goods: An Adaptive Choice-Based Conjoint analysis among residents of European outdoor markets. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2022, 11, 100556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouki-Block, M.; Wellbrock, C.M. Influenced by Media Brands? A Conjoint Experiment on the Effect of Media Brands on Online Media Planners’ Decision-Making. J. Media Bus. Stud. 2022, 19, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickkar, A.; Lee, Y.J. Willingness to Pay for Advanced Safety Features in Vehicles: An Adaptive Choice-Based Conjoint Analysis Approach. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022, 2676, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, K. Environmental preferences and consumer behavior. Econ. Lett. 2016, 149, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andor, M.A.; Lange, A.; Sommer, S. Fairness and the support of redistributive environmental policies. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2022, 114, 102682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, A.L.; Wardman, M.; Zanni, A.M.; Chintakayala, P.K. Public acceptability of personal carbon trading and carbon tax. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1824–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Shao, S. Distributional effects of a carbon tax on Chinese households: A case of Shanghai. Energy Policy 2014, 73, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D. The measurement of urban travel demand. J. Public Econ. 1974, 3, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manski, C.F. The structure of random utility models. Theory Decis. 1977, 8, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.L.; Ansari, A.; Currim, I.S. Hierarchical Bayes versus finite mixture conjoint analysis models: A comparison of fit, prediction, and partworth recovery. J. Mark. Res. 2002, 39, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasek, J. Anesrake: ANES Raking Implementation. 2018. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=anesrake (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Viscusi, W.K.; Zeckhauser, R.J. The Perception and Valuation of the Risks of Climate Change: A Rational and Behavioral Blend. Clim. Change 2006, 77, 151–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürgisser, R.; Stadelmann-Steffen, I.; and Armingeon, K. Can information, compensation and party cues increase mass support for green taxes? J. Eur. Public Policy 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallbekken, S.; Garcia, J.H.; Korneliussen, K. Determinants of public support for transport taxes. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2013, 58, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotchen, M.J.; Boyle, K.J.; Leiserowitz, A.A. Willingness-to-pay and policy-instrument choice for climate-change policy in the United States. Energy Policy 2013, 55, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canty, A.; Ripley, B.D. Boot: Bootstrap R (S-Plus) Functions. 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=boot (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Fleiß, J.; Ackermann, K.A.; Fleiß, E.; Murphy, R.O.; Posch, A. Social and environmental preferences: Measuring how people make tradeoffs among themselves, others, and collective goods. Cent. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 28, 1049–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. Research on the Collaborative Pollution Reduction Effect of Carbon Tax Policies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, C.; and Esen, Ö. Reducing CO2 emissions in the EU member states: Do environmental taxes work? J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2018, 61, 2396–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woerner, A.; Imai, T.; Pace, D.D.; Schmidt, K.M. How to increase public support for carbon pricing with revenue recycling. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 1633–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth, D.; Weiner, C.; Lakócai, C. Public support and willingness to pay for a carbon tax in Hungary: Can revenue recycling make a difference? Energy Sustain. Soc. 2024, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from a Typical Passenger Vehicle. 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/greenhouse-gas-emissions-typical-passenger-vehicle (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- World Bank. Carbon Pricing Dashboard. 2023. Available online: https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/compliance/price (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Carattini, S.; Carvalho, M.; Fankhauser, S. Overcoming public resistance to carbon taxes. WIREs Clim. Change 2018, 9, e531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabla-Norris, E.; Khalid, S.; Magistretti, G.; and Sollaci, A. Does information change public support for climate mitigation policies? Clim. Policy 2024, 24, 1474–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiser-McGrath, L.F.; Bernauer, T. How Do Pocketbook and Distributional Concerns Affect Citizens’ Preferences for Carbon Taxation? J. Politics 2023, 86, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre-Andrés, S.; Drews, S.; van den Bergh, J. Perceived fairness and public acceptability of carbon pricing: A review of the literature. Clim. Policy 2019, 19, 1186–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.J.; Allen, P.G.; Stevens, T.H.; Weatherhead, D. A Meta-analysis of Hypothetical Bias in Stated Preference Valuation. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2005, 30, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entem, A.; Lloyd-Smith, P.; Adamowicz, W.L.; Boxall, P.C. Using inferred valuation to quantify survey and social desirability bias in stated preference research. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2022, 104, 1224–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Observations | Quota Sample | Quota Electorate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender a: | |||

| Female | 600 | 49.34% | 51.11% |

| Male | 610 | 50.16% | 48.89% |

| Diverse | 6 | 0.49% | NA b |

| Age a: | |||

| <20 | 52 | 4.27% | 4.55% |

| 20–29 | 512 | 42.04% | 17.58% |

| 30–39 | 149 | 12.23% | 13.65% |

| 40–49 | 100 | 8.21% | 16.15% |

| 50–59 | 227 | 18.64% | 15.38% |

| 60–69 | 57 | 4.68% | 17.51% |

| >70 | 121 | 9.93% | 15.18% |

| Highest completed education c: | |||

| Mandatory school | 86 | 7.07% | 24.41% |

| Apprenticeship | 187 | 15.38% | 30.88% |

| High School | 485 | 39.88% | 15.59% |

| University | 417 | 34.29% | 15.35% |

| Others | 41 | 3.37% | 13.77% |

| Monthly household income d: | |||

| <1500 | 235 | 19.41% | 14.37% |

| 1500–2499 | 269 | 22.21% | 24.87% |

| 2500–3499 | 250 | 20.64% | 19.94% |

| 3500–4499 | 189 | 15.61% | 15.07% |

| 4500–5499 | 122 | 10.07% | 10.58% |

| >5500 | 146 | 12.06% | 15.16% |

| Total | 1216 |

| Attributes | Levels | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 €-Cent | ||

| 10 €-Cent | ||

| 25 €-Cent | ||

| Tax level | 50 €-Cent | Additional mineral oil tax. |

| 75 €-Cent | ||

| 100 €-Cent | ||

| 125 €-Cent | ||

| 0 € | ||

| 50 € | ||

| Rebate | 100 € | Yearly financial repayment |

| 150 € | to persons over 18 years. | |

| 200 € | ||

| 300 € | ||

| No tax increase | Baseline level in absence of a tax. | |

| Public transport | Subsidizing of public transport measures. | |

| Alternative engines | Subsidizing of other engines (e.g. e-mobility). | |

| Earmarking | Low-income households | Re-distribution to cushion social hardship. |

| General budget | No specific use of the revenues. | |

| Climate protection | Subsidizing of climate protection initiatives. | |

| Full repayment to adults | All tax revenues are equally reimbursed. |

| Tax Level | Lump-Sum Payment | Earmarking | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | % | Level | % | Level | % |

| 0 €-cent | 22.3 | €0 | 30.5 | No tax increase | 12.6 |

| 10 €-cent | 25.9 | €50 | 20.6 | Public transport | 39.1 |

| 25 €-cent | 24.1 | €100 | 25.0 | Alternative engines | 8.6 |

| 50 €-cent | 15.2 | €150 | 11.3 | Low-income households | 5.1 |

| 75 €-cent | 5.7 | €200 | 6.4 | General budget | 2.7 |

| 100 €-cent | 3.1 | €300 | 6.1 | Climate protection | 28.3 |

| 125 €-cent | 3.7 | Full repayment to adults | 3.7 | ||

| Level | 10-Quantile | Median | 90-Quantile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 €-Cent | −78.874 | 9.378 | 104.928 | |

| 10 €-Cent | −22.787 | 37.854 | 82.464 | |

| 25 €-Cent | −9.054 | 28.641 | 69.346 | |

| Tax level | 50 €-Cent | −20.291 | 13.851 | 44.901 |

| 75 €-Cent | −46.553 | −19.772 | 27.980 | |

| 100 €-Cent | −63.559 | −34.922 | 24.833 | |

| 125 €-Cent | −93.726 | −62.316 | 17.043 | |

| €0 | −33.227 | 1.797 | 44.600 | |

| €50 | −14.838 | 6.650 | 27.832 | |

| Rebate | €100 | −4.259 | 9.242 | 23.829 |

| €150 | −11.361 | 1.771 | 15.218 | |

| €200 | −24.167 | −7.248 | 10.902 | |

| €300 | −42.767 | −17.713 | 15.052 | |

| No tax increase | −51.500 | −21.299 | 23.750 | |

| Public transport | 8.701 | 38.646 | 78.880 | |

| Alternative engines | −30.116 | −2.098 | 30.916 | |

| Earmarking | Low-income households | −42.104 | −11.521 | 24.712 |

| General budget | −66.947 | −38.201 | −2.114 | |

| Climate protection | −4.672 | 34.836 | 73.284 | |

| Full repayment to adults | −47.405 | −12.790 | 16.684 | |

| None | 0.505 | 53.580 | 102.416 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mölk, F.F.; Bottner, F.; Tappeiner, G.; Walde, J. Non-Monotone Carbon Tax Preferences and Rebate-Earmarking Synergies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7282. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167282

Mölk FF, Bottner F, Tappeiner G, Walde J. Non-Monotone Carbon Tax Preferences and Rebate-Earmarking Synergies. Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7282. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167282

Chicago/Turabian StyleMölk, Felix Fred, Florian Bottner, Gottfried Tappeiner, and Janette Walde. 2025. "Non-Monotone Carbon Tax Preferences and Rebate-Earmarking Synergies" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7282. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167282

APA StyleMölk, F. F., Bottner, F., Tappeiner, G., & Walde, J. (2025). Non-Monotone Carbon Tax Preferences and Rebate-Earmarking Synergies. Sustainability, 17(16), 7282. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167282