Food Security Strategy for Mercosur Countries in Response to Climate and Socio-Economic Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- (a)

- Identification of Critical Areas of Food System Functioning. Based on the literature and Mercosur countries’ food policies, four key areas for ensuring food security were identified: physical and logistical availability of food (e.g., supply chain efficiency and self-sufficiency); economic accessibility (e.g., income, poverty, and inequality); food quality and safety (e.g., nutritional standards and dietary diversity); and food system resilience to external factors (e.g., climate change, political risk, and natural resource degradation).

- (b)

- Indicator Selection Criteria. The following methodological criteria were applied: Measurability and Comparability—only indicators available for all analysed countries were included, with a consistent temporal and methodological framework; Public Policy Relevance—selected indicators had to be linked to existing policy programmes or strategic initiatives (e.g., poverty reduction programmes and climate adaptation); Sensitivity to Macroeconomic and Climate Variables—indicators chosen demonstrated the ability to reflect changes in the food system resulting from external shocks; Structural Representativeness—the selection encompassed indicators reflecting both systemic resources (e.g., infrastructure and self-sufficiency) and social factors (e.g., inequality and access to a healthy diet).

- (c)

- Assessment and Classification of Point Values Indicators Based Primarily on the GFSI Score (0–100). This was then classified according to the following scale: 85 points—a strong point; 50–85 points—moderate strength or weakness (depending on the dynamics and context); below 50 points—a weak point.

3. Results: Food Security in Mercosur Countries

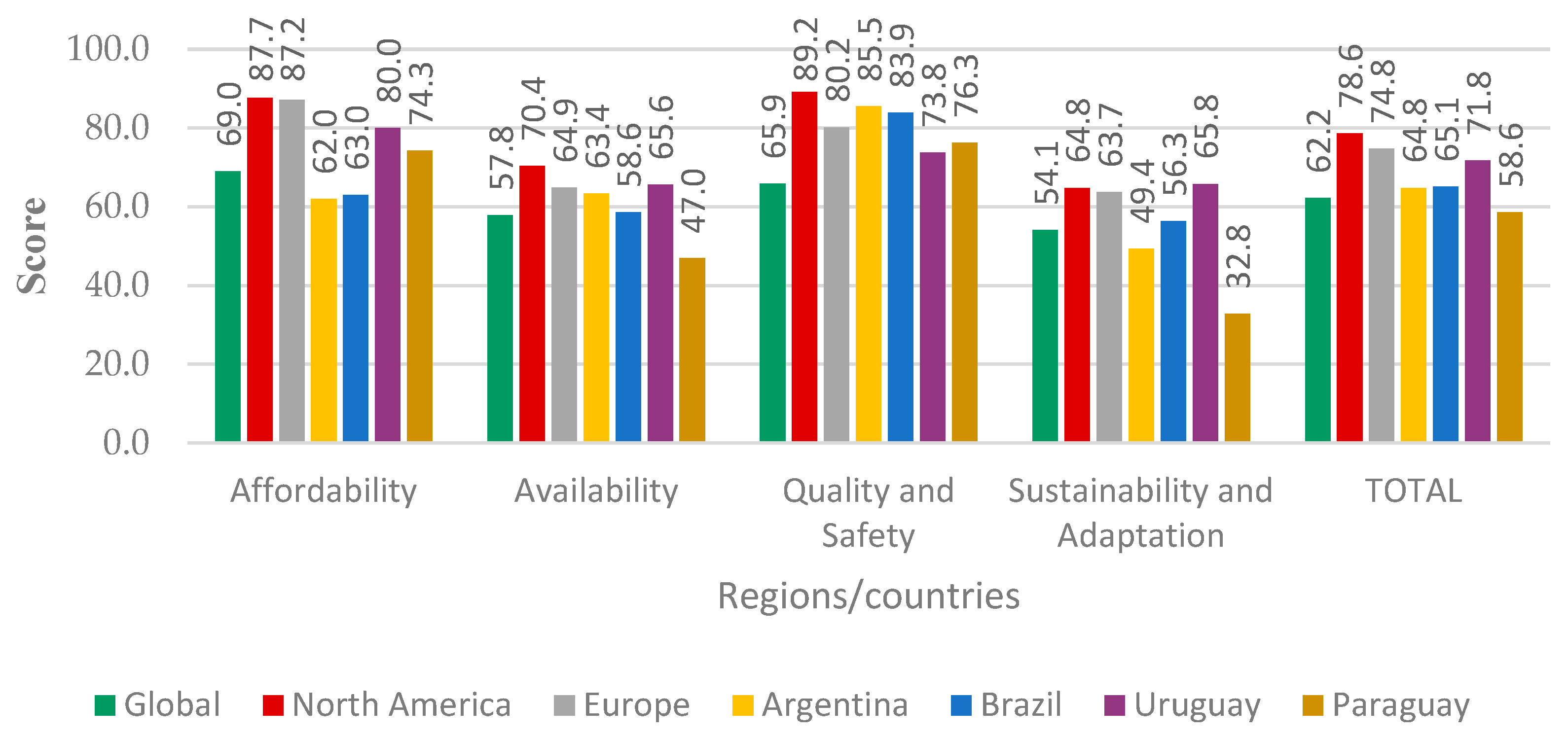

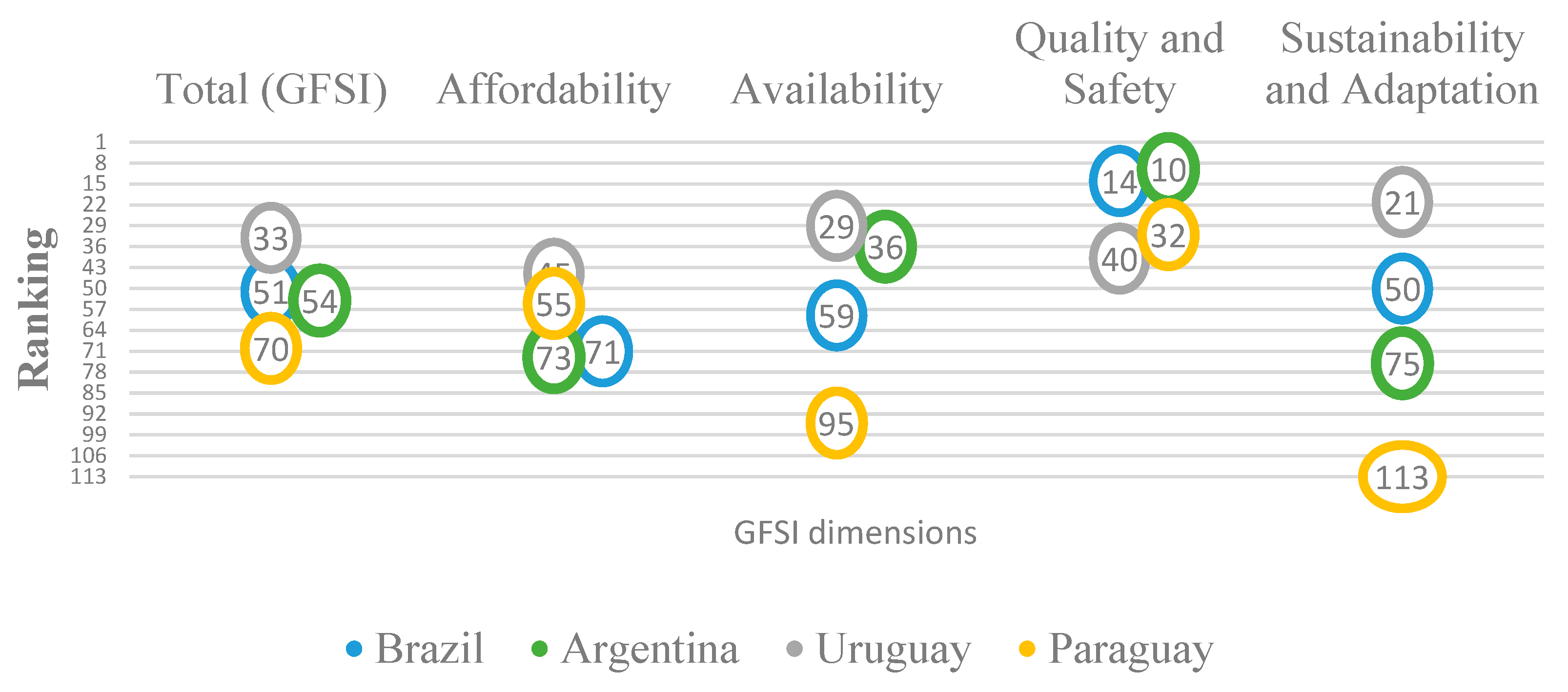

3.1. Assessment of Food Security in Mercosur Countries Compared with Global, North American, and European Contexts

3.2. Synthetic Analysis of Food Security in Mercosur Countries

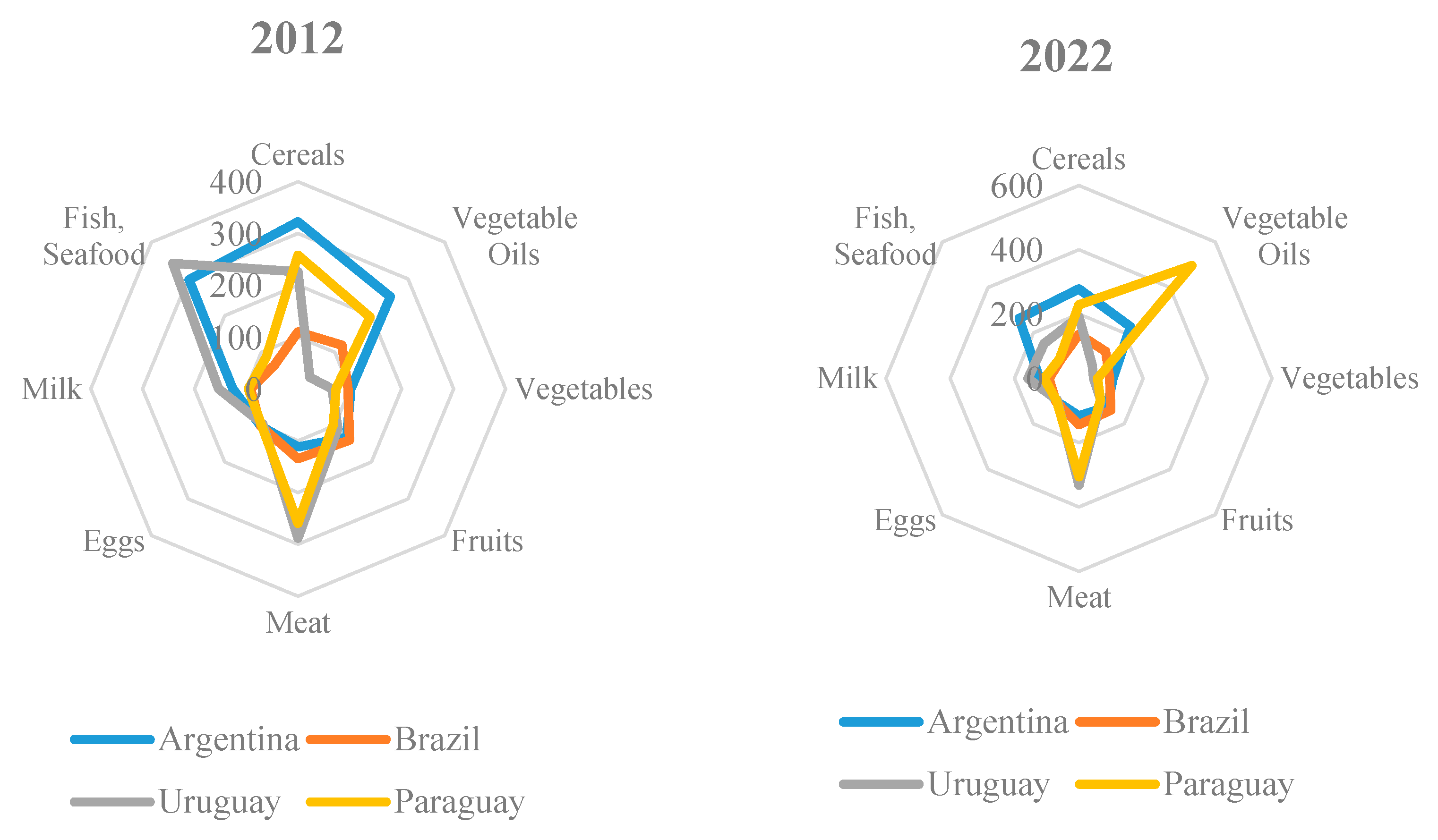

3.3. An Assessment of Food Self-Sufficiency in Mercosur Countries

3.4. Evaluating the Resilience of Food Systems: Economic Drivers and Public Policies in Mercosur Countries

3.5. Strategic Analysis of Food System Resilience in Mercosur Countries

- Integrated Regional Policy: A common food security strategy must be developed, taking into account climate change, infrastructure barriers, and market integration;

- Strengthening Research and Innovation: Long-term investment in precision agriculture, biotechnology, and local research centres is essential, particularly in Paraguay and Brazil;

- Reducing Access Inequality: Improving food distribution systems and reducing costs for vulnerable groups are essential to enhance affordability;

- Building Climate Resilience: Implementation of irrigation technologies, drought risk management, and the development of local early warning systems are essential;

- Infrastructure and Logistics Development: Expanding transport and storage networks to reduce food losses and enhance supply chains;

- Diversification of Energy Sources and Fertilisers: Implementing policies to support local production of biofuels and green fertilisers to reduce import dependency;

- Monitoring and Evaluation: Regularly utilise indices such as the GFSI to measure progress and assess the effectiveness of policies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Climate Vulnerability and Adaptation

4.2. Social Inequality and Food Access

4.3. Institutional Capacity and Policy Coordination

5. Conclusions

- Establish a regional monitoring and coordination mechanism under Mercosur to track food security indicators (e.g., via the GFSI) and support the harmonisation of emergency-response and poverty-alleviation policies;

- Invest in inclusive rural infrastructure and logistics, particularly in drought-prone and remote areas, to improve food availability and reduce distributional gaps;

- Support the scaling up of climate-smart agriculture (CSA) and sustainable input production (e.g., biofertilisers and renewable energy) through public–private partnerships and targeted funding programmes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO; IFAD; PAHO; UNICEF; WFP. Latin America and the Caribbean—Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2024: Statistics and Trends; FAO; IFAD; PAHO; UNICEF; WFP: Santiago, Chile, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, J.; Jank, M.; Cardoso, V.; Umaña, V.; Gilio, L. The Role of International Trade in Promoting Food Security; IICA, Insper Agro Global: São Paulo, Brazil, 2024; 34p, Available online: https://agro.insper.edu.br/storage/papers/September2024/INTERNATIONAL%20TRADE.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- World Bank Group. Regional Poverty and Inequality Update Latin America and the Caribbean, October 2024. Poverty and Equity Global Practice Latin America and the Caribbean; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; 27p, Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099101624155030674/pdf/P5060951be4bad0341bb0f12622f0781694.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Economist Impact. Global Food Security Index 2022. Exploring Challenges and Developing Solutions for Food Security Across 113 Countries. 2022. Available online: https://impact.economist.com/sustainability/project/food-security-index (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Treat, S. Food Safety and the EU-Mercosur Agreement: Risking Weaker Standards on Both Sides of the Atlantic; Heinrich Bóll Stiftung: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://eu.boell.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/Food%20safety%20and%20the%20EU-Mercosur%20Agreement%20-%20Risking%20weaker%20standards%20on%20both%20sides%20of%20the%20Atlantic.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- EU Sugar. Joint Press Release: “Leading European Agri-Food Organisations Call for Reciprocity Standards in Mercosur Agreement to Ensure Fair Trade, Fair Competition and Consumer Protection”. 26 November 2024. Available online: https://cefs.org/joint-press-release-leading-european-agri-food-organisations-call-for-reciprocity-standards-in-mercosur-agreement-to-ensure-fair-trade-fair-competition-and-consumer-protection (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- EC. EU-Mercosur: Text of the Agreement. Trade and Economic Security. 2025. Available online: https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/Mercosur/eu-Mercosur-agreement/text-agreement_en (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Siahaan, G.N.B. Ensuring food security amidst climate change: Comparative analysis of the European Union and Southeast Asia. Mandalika Law J. 2024, 2, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, B. Global Agricultural Competitiveness Index (Gaci) in the Context of Climate Change: A Holistic Approach. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietro Galeone. Environmentalists and EU Farmers Against the EU-Mercosur Trade Deal. 19 February 2025. Available online: https://iep.unibocconi.eu/publications/commentaries/foes-benefits (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://www.fao.org/publications/fao-flagship-publications/the-state-of-food-security-and-nutrition-in-the-world/en (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Kowalczyk, S. Bezpieczeństwo i Jakość Żywności (Food Safety and Quality); PWN Scientific Publishing: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; pp. 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, E.M.; Dernini, S.; Burlingame, B.; Meybeck, A.; Conforti, P. Food security and sustainability: Can one exist without the other? Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2293–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. The State of Food Insecurity in the World. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Viale delle Terme di Caracalla; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2004; 43p, Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/y5650e/y5650e00.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Lignani, J.B.; Palmeira, P.A.; Antunes, M.M.L.; Salles-Costa, R. Relationship between social indicators and food insecurity: A systematic review. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2020, 23, e200068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. The Food Insecurity Experience Scale. FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/in-action/voices-of-the-hungry/fies/en/ (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Allee, A.; Lynd, L.; Vaze, V. Cross-national analysis of food security drivers: Comparing results based on the Food Insecurity Experience Scale and Global Food Security Index. Food Secur. 2021, 13, 1245–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Sandoval, D.; Durán-Romero, G.; Uleri, F. How Much Food Loss and Waste Do Countries with Problems with Food Security Generate? Agriculture 2023, 13, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlehurst, C. Too Good to Go Sees Food Waste as Opportunity That’s Too Good to Miss. Financial Times, 15 November 2023. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/abeb4ea9-1566-4d3d-bb05-e1ccee84609b?utm_source (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Khalid, R.U.; Jajja, M.S.S.; Ahsan, M.B. Supply chain sustainability and risk management in food cold chains—A literature review. Mod. Supply Chain. Res. Appl. 2024, 6, 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marusak, A.; Sadeghiamirshahidi, N.; Krejci, C.; Mittal, A.; Beckwith, S.; Cantu, J.; Morris, M.; Grimm, J. Resilient regional food supply chains and rethinking the way forward: Key takeaways from the COVID-19 pandemic. Agric. Syst. 2021, 190, 103101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.A.; Dubois, L.; Tremblay, M.S. Place and food insecurity: A critical review and synthesis of the literature. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Sustainable diets and biodiversity directions and solutions for policy, research and action. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Symposium Biodiversity and Sustainable Diets United Against Hunger, Rome, Italy, 3–5 November 2010; Burlingame, B., Dernini, S., Eds.; Nutrition and Consumer Protection Division: Rome, Italy, 2010. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/food_composition/documents/upload/i3022e.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- HLPE. Nutrition and Food Systems. A Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome. 2017. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/4ac1286e-eef3-4f1d-b5bd-d92f5d1ce738/content (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Carrillo-Álvarez, E.; Salinas-Roca, B.; Costa-Tutusaus, L.; Milà-Villarroel, R.; Shankar Krishnan, N. The Measurement of Food Insecurity in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bouis, H.E.; Saltzman, A. Improving nutrition through biofortification: A review of evidence from HarvestPlus, 2003 through 2016. Glob Food Sec. 2017, 12, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Teixeira, A.; Jardim, C.A. Building Climate-Resilient Food Systems: The Case of IFAD in Brazil’s Semiarid. In Climate Change in Regional Perspective; United Nations University Series on, Regionalism; Ribeiro Hoffmann, A., Sandrin, P., Doukas, Y.E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juri, S.; Baraibar, M.; Clark, L.B.; Cheguhem, M.; Jobbagy, E.; Marcone, J.; Mazzeo, N.; Meerhoff, M.; Trimble, M.; Zurbriggen, C.; et al. Food systems transformations in South America: Insights from a transdisciplinary process rooted in Uruguay. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 887034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Freitas, S.A.F.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Lokupitiya, E.; Donkor, F.K.; Etim, N.N.; Matandirotya, N.; Olooto, F.M.; Sharifi, A.; Nagy, G.J.; et al. An overview of the interactions between food production and climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amoak, D.; Luginaah, I.; McBean, G. Climate Change, Food Security, and Health: Harnessing Agroecology to Build Climate-Resilient Communities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidhuber, J.; Tubiello, F.N. Global food security under climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19703–19708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lefe, Y.D.H.; Asare-Nuamah, P.; Njong, A.M.; Kondowe, J.; Musakaruka, R.R. Does climate variability matter in achieving food security in Sub-Saharan Africa? Environ. Chall. 2024, 15, 100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripple, W.J.; Wolf, C.; Gregg, J.W.; Rockström, J.; Mann, M.E.; Oreskes, N.; Lenton, T.M.; Rahmstorf, S.; Newsome, T.M.; Xu, C.; et al. The 2024 state of the climate report: Perilous times on planet Earth. BioScience 2024, 74, 812–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets 2015–16 (IN DEPTH). Food Self-Sufficiency and International Trade: A False Dichotomy? FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/ea722624-2814-4cc5-ba44-90a79a2c2de5/content (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- FAOSTAT. Food Balances (2012–)—Metadata. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FBS/metadata (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- FAOSTAT. Database. 2024. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FBS (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Szczepaniak, I. Samowystarczalność Żywnościowa Polski. (Food Self-Sufficiency in Poland). Przemysł Spożywczy 2012, 66, 2–5. Available online: https://yadda.icm.edu.pl/baztech/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-article-LOD1-0030-0005 (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- FAO; CIHEAM; UFM. Food Systems Transformation—Processes and Pathways in the Mediterranean: A Stocktaking Exercise; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, S.F.P.D.; Basir, K.H. Smart farming: Towards a sustainable agri-food system. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 3085–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAO and Argentina Together to Fight Hunger and Promote Food Security Globally; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://fao.sitefinity.cloud/americas/news/news-detail/FAO-and-Argentina-together-to-fight-hunger-and-promote-food-security-globally/en (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Statista.com. Prevalence of Food Insecurity in Argentina Between 2014 and 2023, by Degree of Severity. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1034316/food-insecurity-prevalence-severity-argentina/ (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- FAO. GIEWS—Global Information and Early Warning System. Argentyna; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025; Available online: https://www.fao.org/giews/countrybrief/country.jsp?code=AR (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Ferreira, I. Food Security in Brazilian Households Increases in 2023. Agencja IBGE, 25 April 2024. Available online: https://nada.ibge.gov.br/en/agencia-news/2184-news-agency/news/39857-food-security-in-brazilian-households-increases-in-2023 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Fighting Hunger. UN Hunger Map: 2023 Severe Food Insecurity Drops 85% in Brazil. Secretaria de Comunicação Social, 25 July 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.br/secom/en/latest-news/2024/07/un-hunger-map-2023-severe-food-insecurity-drops-85-in-brazil?utm_source (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Statista.com. Share of Moderate or Severe Food Insecurity in Uruguay Between 2018 and 2023, by Gender. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1399479/uruguay-food-insecurity-prevalence-by-gender/ (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- FAO. FAO en Paraguay. Datos Sobre Paraguay en el Panorama Regional de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición 2023; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://www.fao.org/paraguay/noticias/detail-events/es/c/1668091/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Anand, A.; Pandey, S.; Nandy, S. Infographic: Historic Drought in Argentina Reduces Crops and Raises Food Security Risk. S&P Global, 24 May 2023. Available online: https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/es/market-insights/latest-news/agriculture/052423-infographic-argentina-drought-food-insecurity-supply-production-grains (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Giuliano, F.; Navia, D.; Ruber, H. The Macroeconomic Impact of Climate Shocks in Uruguay; Macroeconomics, Trade and Investment Global Practice; World Bank Group: Washington DC, USA, March 2024; 41p, Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099400003272435890/pdf/IDU13bfbac77199f81489e18f2319846d83a3953.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Desantis, D.; Olmedo, C. Paraguay’s Drying River Stokes Water Tensions Between Fishers and Farmers. Reuters, 17 October 2024. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/paraguays-drying-river-stokes-water-tensions-between-fishers-farmers-2024-10-17/?utm_source (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Lazarini, K. Notas Sobre a Propriedade Coletiva da Terra no Brasil. XX ENANPUR 2023—BELÉM 23 A 26 DE MAIO. 2023. Available online: https://anpur.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/st14-08.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Santos, S.F.; Cardoso, R.; Borges, Í.; Almeida, A.; Andrade, E.; Ferreira, I.; Ramos, L. Post-harvest losses of fruits and vegetables in supply centers in Salvador, Brazil: Analysis of determinants, volumes and reduction strategies. Waste Manag. 2019, 101, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro Novo, A.L.; Slingerland, M.A.; Jansen, K.; Kanellopoulos, A.; Giller, K.E. Feasibility and competitiveness of intensive smallholder dairy farming in Brazil in comparison with soya and surgarcane: Case study of the Balde Cheio Programme. Agric. Syst. 2013, 121, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurobank. Country Report: Uruguay; Division for International Relations & Regional Policy: New Delhi, India, 2023; 22p, Available online: https://www.sev.org.gr/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Uruguay-Country-Report_2023.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Ares, G.; Brunet, G.; Giménez, A.; Girona, A.; Vidal, L. Understanding fruit and vegetable consumption among Uruguayan adults. Appetite 2025, 206, 107824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez, A.; Montoli, P.; Curutchet, M.R.; Ares, G. Strategies to reduce losses and waste of fruits and vegetables in the last stages of the agrifood-chain: Advances and challenges. Agrociencia Urug. 2021, 25, e813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, T. Paraguay’s Agriculture: Struggling with Import Dependency and Price Fluctuations. Potatoes News, 10 December 2023. Available online: https://potatoes.news/paraguays-agriculture-struggling-with-import-dependency-and-price-fluctuations/?utm_source (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Chivers, C. Agricultural Pesticide Use in Argentina: The Extent, the Risks, and the Challenges. Sprint: Sustainable Plant Protection Transition, 1 February 2022. Available online: https://sprint-h2020.eu/index.php/blog/item/6-pesticides-argentina (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Mark, J.; Fantke, P.; Soheilifard, F.; Alcon, F.; Contreras, J.; Abrantes, N.; Campos, I.; Baldi, I.; Bureau, M.; Alaoui, A.; et al. Selected farm-level crop protection practices in Europe and Argentina: Opportunities for moving toward sustainable use of pesticides. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 477, 143577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Metadata of SDG Indicator 2.c.1. Indicator of (Food) Price Anomalies; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025; Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/sustainable_development_goals/docs/Metadata_template_2.c.1__Food_CPI_add_.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Ministerio de Capital Humano. Argentina Contra El Hambre. (Argentina Against Hunger). 2023. Available online: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/argentina-contra-el-hambre (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Abigael, S. Argentina’s Never-Ending Economic Crisis. The Science Survey, 12 May 2025. Available online: https://thesciencesurvey.com/news/2025/05/12/argentinas-never-ending-economic-crisis/ (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Ayres, M. Brazil’s Lula Kicks Off Global Effort to End Hunger and Poverty. Reuters. 2024. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/brazils-lula-kicks-off-global-effort-end-hunger-poverty-2024-07-24/?utm_source (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Falcao, S.T.; Campante, C.V.R.; Dominici, C.B.; Lara, I.G.; Posadas, J. New Bolsa Família: Challenges and Opportunities for 2023—Technical Note 1: Executive Summary (English); World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099092023174612801 (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Uruguay XXI. Agricultural Sector in Uruguay. Agricultural Report. November 2024. Available online: https://www.uruguayxxi.gub.uy/uploads/informacion/0083726fbd9d30ce6bed73313c2daa8f670c3931.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- UNDP. Food Security in Paraguay: Access Barriers to a Healthy Diet. 2020. Available online: https://www.undp.org/es/paraguay/blog/food-security-paraguay-access-barriers-healthy-diet (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Villamizar, A.; Gutiérrez, M.E.; Nagy, G.J.; Caffera, R.M.; Leal, F.W. Climate adaptation in South America with emphasis in coastal areas: The state-of-the-art and case studies from Venezuela and Uruguay. Clim. Dev. 2016, 9, 364–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errazola, A.P.A. Climate Change Impacts on The Uruguayan Dairy Sector by 2050. Master’s Thesis, Deakin University, Victoria, Australia, 2021; 141p. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12381/297 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Paola Nano. EU-Mercosur Trade Deal: Concerns from the EU Slow Food Network. Slow Food, 4 December 2024. Available online: https://www.slowfood.com/blog-and-news/eu-mercosur-concerns-from-eu-slow-food-network (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- EC. Trade and Economic Security. Factsheet: EU-Mercosur Partnership Agreement—Respecting Europe’s Health and Safety Standards. 2025. Available online: https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/mercosur/eu-mercosur-agreement/factsheet-eu-mercosur-partnership-agreement-respecting-europes-health-and-safety-standards_en (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Aróstica, P. Food Security Asymmetries in Latin America and the Caribbean: Keys to cooperation with the European Union. Food Security: Challenges and Opportunities for European Union-Latin America and the Caribbean Relations; Monografia: Barcelona, Spain, 2023; 86p, ISBN 978-84-18977-20-6. Available online: https://eulacfoundation.org/sites/default/files/2024-02/Food%20Security.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Stevenson, K.K. Food Insecurity in Argentina. Perspect. Bus. Econ. 2021, 39, 54–61. Available online: https://preserve.lehigh.edu/_flysystem/fedora/2023-12/304036.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Andrioli, A.I.; Antunes, R.F. Food inequalities in Argentina and Brazil: A Dilemma of our Time. CSS Work. Pap. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Vásquez, A.; Visconti-Lopez, F.J.; Vargas-Fernández, R. Factors Associated with Food Insecurity in Latin America and the Caribbean Countries: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of 13 Countries. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Analysis and Mapping of Impacts Under Climate Change for Adaptation and Food Security (AMICAF) Project in Paraguay; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; 29p, Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340899650_Analysis_and_Mapping_of_Impacts_under_Climate_Change_for_Adaptation_and_Food_Security_AMICAF_project_in_Paraguay (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Pushpanathan, S. Food security in ASEAN: Progress, challenges and future. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1260619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehring, M.; Cordonier-Segger, M.; Tokas, M.; Garcia, M. Study: Alternatives for a Fair and Sustainable Partnership Between the EU and Mercosur: Scenarios and Guidelines; EFA, European Parliament: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2024; 38p, Available online: https://ieep.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/EU-Mercosur-agreement_V1_comments13-002.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- EC. Food Crises Worsen in the Wake of Conflicts, Economic Shocks and Weather Extremes. The Joint Research Centre: EU Science Hub. News Announcement, 3 May 2023. Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/jrc-news-and-updates/food-crises-worsen-wake-conflicts-economic-shocks-and-weather-extremes-2023-05-03_en (accessed on 11 June 2025).

| GFSI | Global | Argentina | Brazil | Uruguay | Paraguay | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | Score Changes 2022 vs. 2012 | 2022 | Score Changes 2022 vs. 2012 | 2022 | Score Changes 2022 vs. 2012 | 2022 | Score Changes 2022 vs. 2012 | ||

| Affordability: | 69.0 | 62.0 | −0.4 | 63.0 | −3.4 | 80.0 | +8.3 | 74.3 | −9.5 |

| - Change in average food costs | 70.7 | 0.0 | −66.0 | 38.0 | −16.5 | 66.0 | +35.0 | 54.0 | −40.0 |

| - Proportion of population below global poverty line | 76.6 | 94.1 | −1.0 | 95.6 | +5.2 | 99.3 | −0.2 | 95.2 | −0.2 |

| - Inequality-adjusted income index | 55.5 | 60.6 | 0 | 44.2 | 0 | 61.4 | 0 | 45.2 | 0 |

| - Agricultural trade | 67.6 | 66.9 | −1.1 | 66.8 | −2.5 | 72.6 | −0.3 | 76.2 | +0.4 |

| - Food safety net programmes | 72.4 | 100 | 0 | 73.2 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Availability: | 57.8 | 63.4 | +2.2 | 58.6 | −0.4 | 65.6 | +1.7 | 47.0 | −6.6 |

| - Access to agricultural inputs | 57.6 | 75.3 | 0 | 83.6 | 0 | 83.6 | 0 | 50.3 | 0 |

| - Agricultural research and development | 47.1 | 65.2 | +20.9 | 55.4 | −2.4 | 68.1 | +24.4 | 26.8 | −13.2 |

| - Farm infrastructure | 55.7 | 57.7 | −1.2 | 52.4 | +0.2 | 27.0 | 0 | 20.9 | +0.1 |

| - Volatility in agricultural production | 68.7 | 71.4 | 0 | 95.2 | 0 | 3.8 | 0 | 85.0 | +3.4 |

| - Food loss | 75.5 | 87.9 | −1.3 | 51.9 | −1.6 | 47.5 | −8.2 | 62.8 | +1.6 |

| - Supply chain infrastructure | 47.8 | 49.1 | 0 | 35.8 | 0 | 55.9 | −2.4 | 37.2 | 0 |

| - Sufficiency of supply | 61.9 | 40.4 | 0 | 38.7 | 0 | 86.0 | +0.8 | 24.7 | −48.1 |

| - Political and barriers to access | 58.7 | 70.1 | 0 | 64.4 | 0 | 84.6 | −1.3 | 57.5 | 0 |

| - Food security and access policy commitments | 47.1 | 52.5 | 0 | 47.5 | 0 | 100.0 | 0 | 52.5 | 0 |

| Quality and Safety: | 65.9 | 85.5 | 0 | 83.9 | +0.1 | 73.8 | −1.1 | 76.3 | −0.3 |

| - Dietary diversity | 52.5 | 56.3 | 0 | 60.5 | 0 | 49.8 | 0 | 54.3 | 0 |

| - Nutritional standards | 63.7 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 61.3 | 0 | 88.7 | 0 |

| - Micronutrient availability | 67.8 | 75.1 | 0 | 63.4 | 0 | 86.3 | 0 | 81.8 | 0 |

| - Protein quality | 68.5 | 100 | 0 | 94.0 | +0.3 | 76.5 | −5.5 | 61.6 | −1.2 |

| - Food safety | 76.4 | 94.4 | 0 | 99.7 | +0.2 | 94.6 | 0 | 94.6 | 0 |

| Sustainability and Adaptation: | 54.1 | 49.4 | −1.3 | 56.3 | 0 | 65.8 | 0 | 32.8 | −6.3 |

| - Exposure | 67.9 | 75.8 | 0 | 67.1 | 0 | 76.4 | 0 | 76.8 | 0 |

| - Water | 41.2 | 61.2 | 0 | 63.8 | 0 | 63.8 | 0 | 38.8 | 0 |

| - Land | 61.3 | 40.4 | +0.1 | 54.4 | +0.4 | 59.7 | −0.1 | 36.1 | +0.2 |

| - Oceans, rivers, and lakes | 41.5 | 24.5 | 0 | 38.1 | 0 | 35.9 | 0 | 32.9 | 0 |

| - Political commitment to adaptation | 55.8 | 40.8 | −6.8 | 59.7 | −0.3 | 59.7 | 0 | 12.1 | −33.4 |

| - Disaster risk management | 55.7 | 52.9 | 0 | 52.9 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 62.2 | 64.8 | +0.1 | 65.1 | −1.1 | 71.8 | +2.6 | 58.6 | +6.0 |

| Item | Argentina | Brazil | Uruguay | Paraguay | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | Score Changes 2022 vs. 2012 | 2022 | Score Changes 2022 vs. 2012 | 2022 | Score Changes 2022 vs. 2012 | 2022 | Score Changes 2022 vs. 2012 | |

| Gross Domestic Product per capita, USD thousand | 13.9 | - | 8.9 | −3.4 | 20.8 | +5.2 | 6.2 | +0.6 |

| Share of agricultural value added in GDP, % | 6.6 | +0.8 | 6.8 | +2.6 | 6.5 | −2.0 | 11.0 | +1.0 |

| Value added of agriculture per employed person, USD thousand | 20.9 | +2.6 | 10.5 | +2.9 | 28.4 | +3.3 | 6.6 | +3.3 |

| Share of the rural population in the total population, % | 473.5 | −918.9 | 1005.9 | +38.3 | 1884.7 | +50.4 | 1203.9 | +185.9 |

| Share of agri-food systems in emissions (CO2), % | 7.8 | −1.1 | 12.8 | −2.6 | 4.5 | −0.9 | 39.8 | −3.6 |

| Gross Domestic Product per capita, USD thousand | 44.7 | −3.9 | 89.6 | −0.3 | 30.8 | −11.5 | 91.5 | +1.5 |

| Pesticides (total), kg/ha of cropland | 5.9 | +0.6 | 12.6 | +5.2 | 5.4 | −0.5 | 7.6 | −3.1 |

| Food Price Anomaly Index (IFPA) by Food CPI * | 0.2 | −1.5 | 0.4 | +0.4 | 0.5 | - | 0.8 | +1.3 |

| Occurrence of Lack of Financial Capacity (PUA), % | NDA | NDA | 25.3 | −2.1 | 36.1 | +5.0 | 24.1 | +0.1 |

| Number of people who cannot afford a healthy diet (NUA), million | NDA | NDA | 53.1 | −3.1 | 1.2 | +0.1 | 1.6 | +0.1 |

| Number of malnourished people, million | 1.4 | - | 8.4 | +2.7 | 0.1 | - | 0.3 | +0.1 |

| Prevalence of malnutrition, % | 3.2 | −0.2 | 3.9 | +1.1 | <2.5 | - | 4.5 | +2.1 |

| Prevalence of severe food insecurity in the population as a whole, % * | 13.1 | +0.5 | 6.6 | +3.5 | 2.9 | +0.8 | 6.6 | +1.4 |

| Parameters | Strong Points | Weak Points |

|---|---|---|

| Affordability |

|

|

| Availability |

|

|

| Quality and Safety |

|

|

| Sustainability and Adaptation |

|

|

| Parameters | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|---|

| Affordability |

|

|

| Availability |

|

|

| Quality and Safety |

|

|

| Sustainability and Adaptation |

|

|

| Opportunities (O) | Threats (T) | |

|---|---|---|

| Strong points (S) | SO Strategies

| ST Strategies

|

| Weak points (W) | WO Strategies

| WT Strategies

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zolotnytska, Y.; Krzyżanowski, J.; Wigier, M.; Krupin, V.; Wojciechowska, A. Food Security Strategy for Mercosur Countries in Response to Climate and Socio-Economic Challenges. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7280. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167280

Zolotnytska Y, Krzyżanowski J, Wigier M, Krupin V, Wojciechowska A. Food Security Strategy for Mercosur Countries in Response to Climate and Socio-Economic Challenges. Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7280. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167280

Chicago/Turabian StyleZolotnytska, Yuliia, Julian Krzyżanowski, Marek Wigier, Vitaliy Krupin, and Adrianna Wojciechowska. 2025. "Food Security Strategy for Mercosur Countries in Response to Climate and Socio-Economic Challenges" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7280. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167280

APA StyleZolotnytska, Y., Krzyżanowski, J., Wigier, M., Krupin, V., & Wojciechowska, A. (2025). Food Security Strategy for Mercosur Countries in Response to Climate and Socio-Economic Challenges. Sustainability, 17(16), 7280. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167280