Intergenerational Information-Sharing Behavior During the COVID-19 Pandemic in China: From Protective Action Decision Model Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What kind of COVID-19 information did Chinese university students share with whom in their family?

- RQ2: Which of these influencing factors affected COVID-19-related information-sharing behavior from Chinese university students to elderly family members, and how?

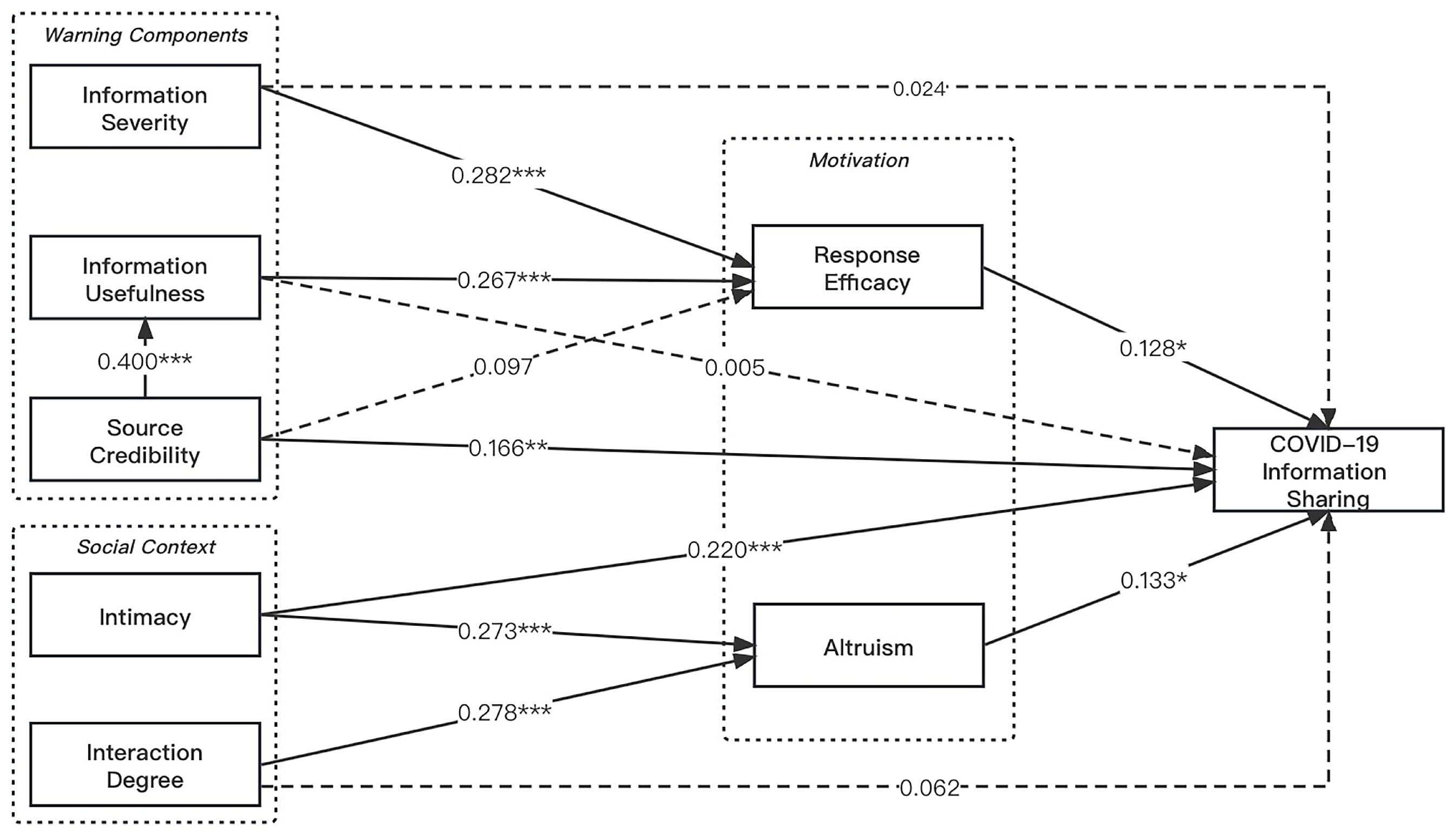

- First, with the PADM, an extended structural equation model was constructed to explore the motivation and behavior of university students to share COVID-19-related information with the elderly family members. Therefore, we divide the influencing factors into three dimensions, namely, the information level, intergenerational level, and motivation level, which correspond to the elements of predecision-making, decision-making, and behavioral response in PADM.

- Second, we reveal that source credibility, intimacy, response efficacy, and altruism have positive effects on COVID-19 information-sharing behavior and that the influence of source credibility on response efficacy is mediated by information usefulness. In addition, the mediating effects of response efficacy and altruism on information severity and the degree of interaction with respect to COVID-19 information sharing are revealed.

- These findings help us understand the antecedents of intergenerational family information-sharing behavior and better protect the health of family members when public health emergencies occur, especially by providing insights into the postpandemic era.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Protective Action Decision Model

2.2. Information-Sharing Behavior

2.3. Family Intergenerational Relationships

3. Research Model and Hypothesis

3.1. Information Severity

3.2. Information Usefulness

3.3. Source Credibility

3.4. Intimacy

3.5. Interaction Degree

3.6. Response Efficacy

3.7. Altruism

4. Research Method

4.1. Data-Collection Procedure

4.2. Descriptive Analysis

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Reliability and Validity

5.2. Hypothesis Testing

6. Discussion

6.1. Implications

6.2. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire Items

| Items | References |

| Information Severity (IS) | |

| IS1: The COVID-19 information is severe to the health of elders (e.g., mutated strains, an increase in the number of newly confirmed cases, the emergence of a new round of infection peak, etc.). | |

| IS2: The content expressed in this COVID-19 information is serious and important for the daily lives of elders (e.g., canceling travel codes, no longer checking nucleic acid, the first round of peak has passed, etc.). | Witte, 1996 [110] |

| IS3: The advice provided by this COVID-19 information is significant for elders (e.g., essential drugs for epidemic prevention, precautions for health, etc.). | |

| IS4: The health threat of this COVID-19 message is harmful to the elders (e.g., the obvious increase of white lung after COVID-19 infection). | |

| Information Usefulness (IU) | |

| IU1: This COVID-19 information can provide me with a lot of knowledge (e.g., prevention knowledge, the latest policies, rumor clarification, etc.). | |

| IU2: This COVID-19 information is valuable (e.g., official prevention and control guidelines, frontline heartwarming videos, confirmed and discharged cases, vaccination status, etc.). | Sussman et al., 2003 [65] |

| IU3: This COVID-19 information is helpful for protecting the health of elders (e.g., epidemic prevention guidelines for special groups). | Luo et al., 2018 [62] |

| IU4: This COVID-19 information is instrutive to help the elders recover their health (e.g., the new crown healing guide, COVID-19 recovery period precautions, etc.). | |

| Source Credibility (SC) | |

| SC1: The provider of COVID-19 information is knowledgeable on this topic. | |

| SC2: The provider of COVID-19 information is an expert on this topic. | Bhattacherjee et al., 2006 [111] |

| SC3: The provider of COVID-19 information is trustworthy on this topic. | |

| SC4: The provider of COVID-19 information is credible on this topic. | |

| Intimacy (INT) | |

| INT1: I often seek opinions from the elders in family on certain events and receive advice. | |

| INT2: No matter what I say or do, the elders in family will understand and respect me. | Blyth et al., 1987 [72] |

| INT3: The elders in family and I understand each other’s true desires. | |

| INT4: I often share my inner thoughts with the elders in family especially during COVID-19 pandemic. | Schaefer, 1981 [55] |

| INT5: I have many common activities with the elders in family. | |

| INT6: I really enjoy playing together with the elders in family. | |

| Interaction Degree (ID) | |

| ID1: I often discuss the COVID-19 information with the elders in family. | |

| ID2: I and the elders in family often seek advice together about the COVID-19. | |

| ID3: The elders in family and I know each other how much information about the COVID-19 each other has. | Alfred, 1998 [112] |

| ID4: The elders in family and I trust each other and often make decisions together when we encounter problems related to COVID-19. | |

| Response Efficacy (RE) | |

| RE1: Sharing COVID-19 information is beneficial for preventing the spread of the epidemic and protecting vulnerable populations. | |

| RE2: Sharing COVID-19 information is beneficial for restoring production and living order. | Witte, 1996 [110] |

| RE3: Sharing COVID-19 information can help reduce the risk of infection. | |

| RE4: Sharing COVID-19 information helps prevent potential health risks. | |

| Altruism (ALT) | |

| ALT1: I enjoy sharing the latest COVID-19 information with elders who rarely use digital devices. | |

| ALT2: Although the elders in family are unable to provide me with the latest COVID-19 information timely, I will also share it with them. | |

| ALT3: I feel very happy to see the elders in family receiving information and taking corresponding measures. | Bhatta et al., 2021 [113] |

| ALT4: I will provide COVID-19 information based on the needs of the elders in family. | |

| ALT5: The amount and frequency of COVID-19 information provided to the elders in family is greater than that provided to me from the elders. | |

| COVID-19 Information Sharing (CIS) | |

| CIS1: When I see the COVID-19 information on social media or news websites, I will share it the elders in family. | |

| CIS2: When I see COVID-19 information related to the elders in family on social media or news websites, I will share it with them. | Liu et al., 2019 [114] |

| CIS3: When I browse COVID-19 information on social media or news websites, I will spend most of my time sharing COVID-19 information with the elders in family. | Lin et al., 2019 [115] |

| CIS4: I often share COVID-19 information with the elders in family through new media (e.g., WeChat, Weibo, Tiktok, etc.). | Wang et al., 2021 [27] |

| CIS5: 5. I often share COVID-19 information with the elders in family through traditional media (e.g., conversation, telephone, text printing, etc.). |

References

- Yuan, H.; Wang, X.; Gao, L.; Wang, T.; Liu, B.; Fang, D.; Gao, Y. Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals has been slowed by indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, R.; Fisher, B. Reset Sustainable Development Goals for a pandemic world. Nature 2020, 583, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Time to revise the Sustainable Development Goals. Nature 2020, 583, 331–332. [CrossRef]

- Hao, P.; Gao, G.F.; Tan, F. Global Sharing of Public Health Information: From MMWR to China CDC Weekly. Am. J. Public Health 2022, 112, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN. The 17 GOALS, 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Outline of the “Healthy China 2030” Plan, 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-10/25/content_5124174.htm (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Porat, T.; Nyrup, R.; Calvo, R.A.; Paudyal, P.; Ford, E. Public Health and Risk Communication During COVID-19—Enhancing Psychological Needs to Promote Sustainable Behavior Change. Front. Public Health 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNDP. Digital Inclusion Playbook 2.0: From Access to Empowerment in a Dynamic World, 2024. Available online: https://www.undp.org/policy-centre/singapore/publications/digital-inclusion-playbook-20 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Spencer, G.; Corbin, J.H.; Miedema, E. Sustainable development goals for health promotion: A critical frame analysis. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 34, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. COVID-19: Embracing Digital Government During the Pandemic and Beyond, 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/PB_61.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Anwar, A.; Malik, M.; Raees, V.; Anjum, A. Role of Mass Media and Public Health Communications in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cureus 2020, 12, e10453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Githinji, P.; Uribe, A.; Szeszulski, J.; Rethorst, C.; Luong, V.; Xin, L.; Rolke, L.; Smith, M.; Seguin-Fowler, R. Public health communication during the COVID-19 health crisis: Sustainable pathways to improve health information access and reach among underserved communities. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbari, M.; Shams Esfandabadi, Z.; Zanetti, M.C.; Scagnelli, S.D.; Siebers, P.O.; Aghbashlo, M.; Peng, W.; Quatraro, F.; Tabatabaei, M. Three pillars of sustainability in the wake of COVID-19: A systematic review and future research agenda for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, F.; Ye, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zuo, B. Icing on the cake: “Amplification Effect” of innovative information form in news reports about COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. Bowen Family Systems Theory and Practice: Illustration and Critique. Aust. N. Z. J. Fam. Ther. 1999, 20, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Fung, H.; Tse, D.; Tsang, V.; Zhang, H.; Mai, C. Obtaining Information from Different Sources Matters During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gerontologist 2021, 62, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, B.; Charness, N.; Fingerman, K.; Kaye, J.; Kim, M.T.; Khurshid, A. When Going Digital Becomes a Necessity: Ensuring Older Adults’ Needs for Information, Services, and Social Inclusion During COVID-19. In Older Adults and COVID-19: Implications for Aging Policy and Practice, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, W.; Fu, X.; Brown, M.; Silverstein, M. Intergenerational solidarity with digital communication and psychological well-being among older parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fam. Process 2023, 63, 1356–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, F.; Al-Kumaim, N.H.; Alzahrani, A.I.; Fazea, Y. The impact of social media shared health content on protective behavior against COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Ealth 2023, 20, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Huang, V.; Zhan, M.; Zhao, X. “Nice you share in return”: Informational sharing, Reciprocal sharing, and life satisfaction amid COVID-19 Ppndemic. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 165, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Lin, L.; Wu, X. Social capital and health communication in Singapore: An examination of the relationships between community participation, perceived neighborliness and health communication behaviors. J. Health Commun. 2020, 25, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, A.; Prena, K.; Cummings, J.J. To share or not to share: Extending Protection Motivation Theory to understand data sharing with the police. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 130, 107188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apuke, O.; Omar, B. Fake news and COVID-19: Modelling the predictors of fake news sharing among social media users. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 56, 101475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Yao, N.; Zhu, W. How consumers’ perception and information processing affect their acceptance of genetically modified foods in China: A risk communication perspective. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, M.; Porebski, D. Application of the DEA method for evaluation of information usefulness efficiency on websites. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Xu, L.; Tang, T.; Wu, X.; Huang, C. Users’ willingness to share health information in a social question-and-answer community: Cross-sectional survey in China. JMIR Med Inform. 2021, 9, e26265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Riaz, M.; Haider, S.; Alam, K.M.; Sherani; Yang, M. Information sharing on social media by multicultural individuals: Experiential, motivational, and network factors. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.; Perry, R. Behavioral Foundations of Community Emergency Planning. Prof. Geogr. 1993, 45, 376–377. [Google Scholar]

- Lindell, M.; Perry, R. The protective action decision model: Theoretical modifications and additional evidence. Risk Anal. 2012, 32, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindell, M.; Perry, R. Household adjustment to earthquake hazard - A review of research. Environ. Behav. 2000, 32, 461–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, W.; Wei, J.; Huang, S.K.; Lindell, M.; Ge, Y.G.; Wei, H.L. Public Reactions to the 2013 Chinese H7N9 Influenza Outbreak: Perceptions of Risk, Stakeholders, and Protective Actions. J. Risk Res. 2018, 21, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahan, K.; Watson, S.J. The protective action decision model: When householders choose their protective response to wildfire. J. Risk Res. 2019, 22, 1602–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Wei, J.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, D.; Lin, X. Residents’ behavioural intentions to resist the nuclear power plants in the vicinity: An application of the protective action decision model. J. Risk Res. 2019, 22, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, F.; Bull, M.; Munoz-Herrera, S.; Robledo, L. Determinant factors in personal decision-making to adopt COVID-19 prevention measures in Chile. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, R.E.; McMakin, A.H. Communicating Risks: A Handbook for Communicating Environmental, Safety, and Health Risks, 5th ed.; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, C.E.; Marks, E. The NORC studies of human behavior in disaster. J. Soc. Issues 1954, 10, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O.; Levine, D. Credibility and trust in risk communication. In Communicating Risks to the Public: International Perspectives; Kasperson, R.E., Stallen, P.J.M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1991; pp. 175–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.; Perry, R. Effects of the chernobyl accident on public perceptions of nuclear-plant accident risks. Risk Anal. 1990, 10, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Kuang, W. Exploring influence factors of WeChat users’ health information sharing behavior: Based on an integrated model of TPB, UGT and SCT. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 37, 1243–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constant, D.; Kiesler, S.; Sproull, L. Whats mine is ours, or is it—A study of attitudes about information sharing. Inf. Syst. Res. 1994, 5, 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S.; Staples, D. The use of collaborative electronic media for information sharing: An exploratory study of determinants. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2000, 9, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Liu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Burns, K.; Lu, E.; Li, D. Source trust and COVID-19 information sharing: The mediating roles of emotions and beliefs about sharing. Health Educ. Behav. 2021, 48, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Kapoor, P. Message sharing and verification behaviour on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic: A study in the context of India and the USA. Online Inf. Rev. 2022, 46, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laato, S.; Islam, A.K.M.N.; Islam, M.N.; Whelan, E. What drives unverified information sharing and cyberchondria during the COVID-19 pandemic? Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Cao, X.; Chen, S.; Liu, L. Public and private information sharing under “New Normal” of COVID-19: Understanding the roles of habit and outcome expectation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Wu, T.; Zhou, L. Sharing of verified information about COVID-19 on social network sites: A social exchange theory perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.Y.H.; Wai, A.K.C.; Zhao, S.; Yip, F.; Lee, J.J.; Wong, C.K.H.; Wang, M.P.; Lam, T.H. Association of individual health literacy with preventive behaviours and family well-being during COVID-19 pandemic: Mediating role of family information sharing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, N.; Kwan, D.; Hillcoat-Nalletamby, S.; Burholt, V. Intergenerational Relationships: Experiences and Attitudes in the New Millennium; Centre for Innovative Ageing: Swansea, Wales, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson, V.; Roberts, R. Intergenerational solidarity in aging families—An example of formal theory construction. J. Marriage Fam. 1991, 53, 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waites, C. Building on Strengths: Intergenerational Practice with African American Families. Soc. Work 2009, 54, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change1. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals—The extended paralle process model. Commun. Monogr. 1992, 59, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, V.; Yoon, K.; Zahedi, F. The measurement of web-customer satisfaction: An expectation and disconfirmation approach. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.; Goldman, R.; Cacioppo, J. Personal involvement as a determinant of argument-based persuasion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 41, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, M.; Olson, D. Assessing intimacy—The pair inventory. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 1981, 7, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanLange, P.; Otten, W.; DeBruin, E.; Joireman, J. Development of prosocial, individualistic, and competitive orientations: Theory and preliminary evidence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesmer-Magnus, J.R.; DeChurch, L.A. Information Sharing and Team Performance: A Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self- efficacy- toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastall, M.R.; Knobloch-Westerwick, S. Severity, Efficacy, and Evidence Type as Determinants of Health Message Exposure. Health Commun. 2013, 28, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, S.C.; Sutton, J.; Yu, Y.; Renshaw, S.L.; Olson, M.K.; Ben Gibson, C.; Butts, C.T. Retweeting risk communication: The role of threat and efficacy. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 2580–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K.; Allen, M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ. Behav. 2000, 27, 591–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Luo, X.R.; Bose, R. Information usefulness in online third party forums. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 85, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, M. Comparative analysis of information usefulness evaluation methods on business internet services. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2020, 23, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Gu, B.; Leung, A.C.M.; Konana, P. An investigation of information sharing and seeking behaviors in online investment communities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, S.; Siegal, W. Informational influence in organizations: An integrated approach to knowledge adoption. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Z.; Liu, Z.; Wong, J.C. Information seeking and information sharing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Commun. Q. 2022, 70, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosnow, R. Inside rumor: A personal journal. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, A.Y.K.; Banerjee, S. Intentions to trust and share online health rumors: An experiment with medical professionals. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 87, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muturi, N. The iInfluence of information source on COVID-19 vaccine efficacy and motivation for self-protective behavior. J. Health Commun. 2022, 27, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.L.; Cheung, C.M.K.; Lee, M.K.O. What leads students to adopt information from Wikipedia? An empirical investigation into the role of trust and information usefulness. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2013, 44, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.; Zhou, J.; Zuo, M. Understanding older adults’ intention to share health information on social media: The role of health belief and information processing. Internet Res. 2021, 31, 100–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blyth, D.; Fosterclark, F. Gender differences in perceived intimacy with different memers of adolescents social networks. Sex Roles 1987, 17, 689–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.H.; Harvey, D.M.; Williamson, D.S. Intergenerational family relationships: An evaluation of theory and measurement. Psychother. Theory 1987, 24, 516–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotevant, H.D.; Cooper, C.R. Individuation in family relationships: A perspective on individual differences in the development of identity and role-taking skill in adolescence. Hum. Dev. 1986, 29, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, R.L.; Schultz, L.H. Making a Friend in Youth: Developmental Theory and Pair Therapy; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D.M.; Curry, C.J.; Bray, J.H. Individuation and intimacy in intergenerational relationships and health: Patterns across two generations. J. Fam. Psychol. 1991, 5, 204–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steijn, W.M.P.; Schouten, A.P. Information sharing and relationships on social networking sites. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashek, D.J.; Aron, A. Handbook of Closeness and Intimacy; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, C. Kin-selection, reciprocal altruism, and information sharing among maine lobstermenal. Ethol. Sociobiol. 1991, 12, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, S.Y.C.L.; Cheng, L.; Wong, D.F.K. Family emotional support, positive psychological capital and job satisfaction among Chinese white-Collar workers. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 16, 561–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossati, A.; Somma, A. Improving family functioning to (hopefully) improve treatment efficacy of personality disorder: An opportunity not to dismiss. Psychopathology 2018, 51, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, E.; Carr, A. Systematic review of self-report family assessment measures. Fam. Process 2016, 55, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, H.R. Pragmatics of human communication. J. Commun. Disord. 1969, 2, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.K.; Cheung, P.C.; Shek, D.T.L. The relation of prosocial orientation to peer interactions, family social environment and personality of Chinese adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2007, 31, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.; Silva, A.R.; Santos, L.; Patrao, M. The family inheritance process: Motivations and patterns of interaction. Eur. J. Aging 2010, 7, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddox, J.; Rogers, R. Protection motivation and self- efficacy—A revised theory of fear appelas and attitude-change. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 19, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Pietrantoni, L.; Zani, B. A social-cognitive model of pandemic influenza H1N1 risk perception and recommended behaviors in Italy. Risk Anal. 2011, 31, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.; Lee, J.S. The influence of self-efficacy, subjective norms, and risk perception on behavioral intentions related to the H1N1 flu pandemic: A comparison between Korea and the US. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 18, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Park, H.; Kim, J. Why do people share their context information on Social Network Services? A qualitative study and an experimental study on users’ behavior of balancing perceived benefit and risk. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2013, 71, 862–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Chuang, S.S. Social capital and individual motivations on knowledge sharing: Participant involvement as a moderator. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovidio, J.F. The Social Psychology of Prosocial Behavior; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Post, S.G. Altruism and Health: Perspectives from Empirical Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs, D.; VanHestere, F. The development of altruism -toward an intergrative model. Dev. Rev. 1994, 14, 103–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piliavin, J.; Charng, H. Altruism—A revies of recent theory and research. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1990, 16, 27–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Syn, S.Y. Motivations for sharing information and social support in social media: A comparative analysis of Facebook, Twitter, Delicious, YouTube, and Flickr. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2015, 66, 2045–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wixom, B.H.; Watson, H.J. An empirical investigation of the factors affecting data warehousing success. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, F.J.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takian, A.; Raoofi, A.; Haghighi, H. Chapter Nine—COVID-19 pandemic: The fears and hopes for SDG 3, with focus on prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases (SDG 3.4) and universal health coverage (SDG 3.8). In COVID-19 and the Sustainable Development Goals; Dehghani, M.H., Karri, R.R., Roy, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, L.; Sadowski, H. Doing intimate family work through ICTs in the time of networked individualism. J. Fam. Stud. 2023, 29, 758–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Namyalo, P.K.; Chen, X.; Lv, M.; Coyte, P.C. What motivates individuals to share information with governments when adopting health technologies during the COVID-19 pandemic? BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witte, K. Fear control and danger control—A Test of the extended parallel process model(EPPM). Commun. Monogr. 1994, 61, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Y.; Khurshid, M. Factors Impacting the Behavioral Intention to Use Social Media for Knowledge Sharing: Insights from Disaster Relief Practitioners. Interdiscip. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 18, 269–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, J.; Kamber, T.; Glazebrook, A.; Giorgi, M.; Ziegler, K. Digital Inclusion of Older Adults during COVID-19: Lessons from a Case Study of Older Adults Technology Services (OATS). J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2021, 64, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieck, C.; Sheon, A.; Ancker, J.; Castek, J.; Callahan, B.; Siefer, A. Digital inclusion as a social determinant of health. NPJ Digit Med. 2021, 4, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K.; Cameron, K.A.; McKeon, J.K.; Berkowitz, J.M. Predicting risk behaviors: Development and validation of a diagnostic scale. J. Health Commun. 1996, 1, 317–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacherjee, A.; Sanford, C. Influence processes for information technology acceptance: An elaboration likelihood model. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, A.; Blonk, R.; Wiers, R.W. The parent-child interaction questionnaire, PACHIQ. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 1998, 5, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, T.; Kahana, E.; Lekhak, N.; Kahana, B.; Midlarsky, E. Altruistic attitudes among older adults: Examining construct validity and measurement invariance of a new scale. Innov. Aging 2021, 5, igaa060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Y. Exploring health information sharing behavior among Chinese older adults: A social support perspective. Health Commun. 2019, 34, 1824–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Sarker, S.; Featherman, M. Users’ Psychological Perceptions of Information Sharing in the Context of Social Media: A Comprehensive Model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2019, 23, 453–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Definition | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| IS | The perception of university students regarding the severity, significance, and the magnitude of the threat contained in the COVID-19 information. | Rogers, 1975 [51], Witte, 1992 [52] |

| IU | The assessment of the informativeness, value, accuracy, veracity, timeliness, completeness, reliability, adequacy, and helpfulness of COVID-19 information. | Mckinney et al., 2002 [53] |

| SC | The extent to which a COVID-19 information source is perceived to be accurate, believable, competent, and trustworthy by university students. | Petty et al., 1981 [54] |

| INT | The degree of closeness between university students and the elder family members. | Schaefer et al., 1981 [55] |

| ID | The distance, times, and duration of daily communication, and the frequency of common activities of family members. | Bengtson, 1991 [49] |

| RE | The belief that sharing COVID-19 information is effective and has desired consequences. | Witte, 1992 [52] |

| ALT | The extent to which university students share COVID-19 information without the expectation of reciprocity and compensation, but to directly or indirectly benefit the elder family members. | VanLange et al., 1997 [56] |

| CIS | The process of university students providing COVID-19 information they obtained to the elder family members. | Mesmer et al., 2009 [57] |

| Characteristic | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 209 | 51.1% |

| Female | 200 | 48.9% | |

| Age | 18–20 | 223 | 54.5% |

| 21–25 | 137 | 33.5% | |

| 26–30 | 43 | 10.5% | |

| Above 30 | 6 | 1.5% | |

| Education | College | 156 | 38.14% |

| Undergraduate | 164 | 40.10% | |

| Master’s and above | 89 | 21.76% | |

| Region | Eastern areas | 214 | 52.3% |

| Middle areas | 172 | 42.1% | |

| Western areas | 23 | 5.6% | |

| Types of COVID-19 shared information (multiple-choice) | Official announcement | 249 | 60.9% |

| Notification report | 171 | 41.8% | |

| Science popularization | 195 | 47.7% | |

| Prevention dynamic status | 187 | 45.7% | |

| Character deeds | 77 | 18.8% | |

| Means of COVID-19 information sharing behavior (multiple-choice) | Verbal face-to-face | 280 | 68.5% |

| Telephone and voice | 216 | 52.8% | |

| (including QQ and WeChat phone) | |||

| Remote video call | 91 | 22.2% | |

| Forward through social media | 285 | 69.7% |

| Construct | Items | Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS | IS1 | 0.881 | 0.91 | 0.937 | 0.787 |

| IS2 | 0.888 | ||||

| IS3 | 0.907 | ||||

| IS4 | 0.874 | ||||

| IU | IU1 | 0.887 | 0.895 | 0.927 | 0.761 |

| IU2 | 0.883 | ||||

| IU3 | 0.872 | ||||

| IU4 | 0.847 | ||||

| SC | SC1 | 0.878 | 0.903 | 0.932 | 0.775 |

| SC2 | 0.874 | ||||

| SC3 | 0.884 | ||||

| SC4 | 0.885 | ||||

| INT | INT1 | 0.803 | 0.9 | 0.923 | 0.667 |

| INT2 | 0.825 | ||||

| INT3 | 0.755 | ||||

| INT4 | 0.796 | ||||

| INT5 | 0.849 | ||||

| INT6 | 0.867 | ||||

| ID | ID1 | 0.883 | 0.887 | 0.921 | 0.746 |

| ID2 | 0.844 | ||||

| ID3 | 0.824 | ||||

| ID4 | 0.902 | ||||

| RE | RE1 | 0.875 | 0.892 | 0.925 | 0.755 |

| RE2 | 0.846 | ||||

| RE3 | 0.857 | ||||

| RE4 | 0.896 | ||||

| ALT | ALT1 | 0.858 | 0.898 | 0.924 | 0.709 |

| ALT2 | 0.844 | ||||

| ALT3 | 0.85 | ||||

| ALT4 | 0.844 | ||||

| ALT5 | 0.815 | ||||

| CIS | CIS1 | 0.857 | 0.917 | 0.938 | 0.752 |

| CIS2 | 0.841 | ||||

| CIS3 | 0.889 | ||||

| CIS4 | 0.867 | ||||

| CIS5 | 0.881 |

| ALT | CIS | ID | INT | IS | IU | RE | SC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT | 0.842 | |||||||

| CIS | 0.363 | 0.867 | ||||||

| ID | 0.383 | 0.315 | 0.864 | |||||

| INT | 0.38 | 0.412 | 0.386 | 0.817 | ||||

| IS | 0.359 | 0.295 | 0.362 | 0.355 | 0.887 | |||

| IU | 0.419 | 0.306 | 0.407 | 0.408 | 0.416 | 0.873 | ||

| RE | 0.344 | 0.341 | 0.358 | 0.365 | 0.432 | 0.424 | 0.869 | |

| SC | 0.409 | 0.375 | 0.364 | 0.365 | 0.391 | 0.400 | 0.315 | 0.880 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Path Coefficient | T-Statistics | p-Value | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | IS→CIS | 0.024 | 0.407 | 0.001 | 0.684 | Not |

| H1b | IS→RE | 0.282 | 5.373 *** | 0.083 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2a | IU→CIS | 0.005 | 0.076 | 0.000 | 0.939 | Not |

| H2b | IU→RE | 0.267 | 4.998 *** | 0.074 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3a | SC→CIS | 0.166 | 2.906 ** | 0.027 | 0.004 | Supported |

| H3b | SC→RE | 0.097 | 1.813 | 0.010 | 0.070 | Not |

| H3c | SC→IU | 0.400 | 8.793 *** | 0.190 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4a | INT→CIS | 0.220 | 3.923 *** | 0.047 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4b | INT→ALT | 0.273 | 5.498 *** | 0.080 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5a | ID→CIS | 0.062 | 1.088 | 0.004 | 0.277 | Not |

| H5b | ID→ALT | 0.278 | 5.538 *** | 0.083 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H6 | RE→CIS | 0.128 | 2.203 * | 0.016 | 0.028 | Supported |

| H7 | ALT→CIS | 0.133 | 2.385 * | 0.017 | 0.017 | Supported |

| Indirect Path | Beta | SD | T-Statistics | p-Value | Confidence Intervals (2.5%) | Confidence Intervals (97.5%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS→RE→CIS | 0.036 | 0.018 | 2.058 * | 0.040 | 0.004 | 0.072 |

| IU→RE→CIS | 0.034 | 0.017 | 1.978 * | 0.048 | 0.003 | 0.071 |

| SC→IU→RE | 0.108 | 0.024 | 4.357 *** | 0.000 | 0.062 | 0.158 |

| ID→ALT→CIS | 0.037 | 0.017 | 2.178 * | 0.029 | 0.006 | 0.073 |

| Construct | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ALT | 0.210 | 0.206 | 0.144 |

| CIS | 0.273 | 0.261 | 0.200 |

| IU | 0.160 | 0.158 | 0.119 |

| RE | 0.266 | 0.260 | 0.195 |

| Index | NFI | rms_theta | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 0.9 | 0.103 | 0.037 |

| Threshold | 0.9 < NFI < 1 | <0.12 | <0.08 |

| PLS-SEM | LM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | |

| IU1 | 1.395 | 1.181 | 0.109 | 1.368 | 1.112 |

| IU2 | 1.395 | 1.178 | 0.108 | 1.33 | 1.083 |

| IU3 | 1.332 | 1.114 | 0.131 | 1.291 | 1.043 |

| IU4 | 1.254 | 1.043 | 0.121 | 1.221 | 0.996 |

| RE1 | 1.293 | 1.068 | 0.162 | 1.277 | 1.04 |

| RE2 | 1.289 | 1.086 | 0.094 | 1.273 | 1.055 |

| RE3 | 1.313 | 1.089 | 0.157 | 1.33 | 1.076 |

| RE4 | 1.319 | 1.098 | 0.178 | 1.32 | 1.075 |

| ALT1 | 1.202 | 1.023 | 0.179 | 1.196 | 0.998 |

| ALT2 | 1.375 | 1.134 | 0.114 | 1.386 | 1.147 |

| ALT3 | 1.293 | 1.051 | 0.113 | 1.277 | 1.023 |

| ALT4 | 1.236 | 1.026 | 0.173 | 1.22 | 0.987 |

| ALT5 | 1.268 | 1.047 | 0.114 | 1.266 | 1.025 |

| CIS1 | 1.286 | 1.051 | 0.154 | 1.306 | 1.073 |

| CIS2 | 1.258 | 1.071 | 0.16 | 1.297 | 1.09 |

| CIS3 | 1.344 | 1.106 | 0.187 | 1.366 | 1.11 |

| CIS4 | 1.25 | 1.047 | 0.172 | 1.265 | 1.041 |

| CIS5 | 1.39 | 1.17 | 0.16 | 1.42 | 1.186 |

| Parents | Grandparents and Maternal Grandparents | Relatives and Elders Within Three Generations | Others | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sort | Frequency | Ratio | Frequency | Ratio | Frequency | Ratio | Frequency | Ratio |

| 1 | 370 | 90.5% | 19 | 4.6% | 20 | 4.9% | 1 | 0.25% |

| 2 | 12 | 2.9% | 362 | 88.5% | 24 | 5.9% | 0 | 0% |

| 3 | 14 | 3.4% | 7 | 1.7% | 345 | 84.4% | 1 | 0.25% |

| 4 | 13 | 3.2% | 21 | 5.1% | 20 | 4.9% | 407 | 99.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Min, L.; Yu, Z. Intergenerational Information-Sharing Behavior During the COVID-19 Pandemic in China: From Protective Action Decision Model Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7263. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167263

Min L, Yu Z. Intergenerational Information-Sharing Behavior During the COVID-19 Pandemic in China: From Protective Action Decision Model Perspective. Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7263. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167263

Chicago/Turabian StyleMin, Lingxin, and Zhiyuan Yu. 2025. "Intergenerational Information-Sharing Behavior During the COVID-19 Pandemic in China: From Protective Action Decision Model Perspective" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7263. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167263

APA StyleMin, L., & Yu, Z. (2025). Intergenerational Information-Sharing Behavior During the COVID-19 Pandemic in China: From Protective Action Decision Model Perspective. Sustainability, 17(16), 7263. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167263