Abstract

To mitigate persistent urban–rural disparities and facilitate comprehensive rural development, the Chinese government institutionalized the Rural Revitalization Strategy. This national policy framework systematically addresses five critical domains of rural development: (1) industrial revitalization, (2) talent revitalization, (3) organizational capacity building, (4) cultural heritage preservation, and (5) ecological conservation. Among them, talent cultivation serves as both a fundamental objective and critical resource for the sustainable rural economic transformation. However, the existing research and practice have disproportionately emphasized industrial and ecological aspects, largely neglecting the acute talent shortage. This study bridges this gap by adopting a population mobility lens to categorize young talent types contributing to Chinese rural economic transformation and analyze their mobility trajectories and resource exchange dynamics. Drawing on an integrated theoretical framework combining Push–Pull Theory and Existence–Relatedness–Growth Theory, as well as empirical evidences from Yuan Village in Shaanxi Province, this research has four key findings. First, there are three distinct young talent categories that have emerged in Chinese rural economic transformation: urban-to-rural young talents, native young talents, and rural-to-rural young talents. It is noteworthy that the rural-to-rural young talent represents a novel flow pattern that can expand our conventional understandings of Chinese population mobility. Second, differential push–pull factors shape each category’s migration decisions, subsequently influenced by their existence needs, social relatedness, and growth requirements as outlined in ERG Theory. Third, through heterogeneous resource exchanges with villagers, committees, and communities, these talents negotiate their positions and satisfy their expectations within the rural socio-economic system. Fourth, unmet exchange expectations may precipitate talent outflow, which will further pose sustainability challenges to revitalization efforts. Additionally, the long-term impacts of the intensified social interactions between talent groups and local residents, as well as their generalizability, require further examination.

1. Introduction

The global landscape of development is increasingly marked by pronounced urban–rural disparities, particularly amid rapid urbanization processes [1]. To bridge this development divide and promote rural economic transformation, developed nations have implemented diverse rural construction strategies [2]. The United States employs an “urban–rural symbiosis” model that leverages small town development as growth poles [3]. Germany’s “urban–rural equivalence” approach prioritizes infrastructure parity and public service equalization. Japan’s “one village, one product” initiative harnesses traditional resources to cultivate regional economic specialization [4], while South Korea’s “new village movement” combines government support with village autonomy [5]. Distinct from these models, China’s Rural Revitalization Strategy is structured around five key dimensions: (1) industrial revitalization, (2) talent revitalization, (3) organizational capacity building, (4) cultural heritage preservation, and (5) ecological conservation. This comprehensive approach reflects Chinese government’s strong organizational capacity and current development priorities. As one of the five key objectives of the Rural Revitalization Strategy, talent revitalization involves attracting and cultivating skilled individuals to support rural construction and growth. This is achieved by strengthening native talent development, encouraging urban professionals to relocate to rural areas, and facilitating the contribution of specialized talents to rural advancement.

From the perspective of implementation performance, China’s rural revitalization strategy has yielded significant outcomes across multiple dimensions. The most notable progress appears in industrial transformation, particularly in peri-urban villages that have successfully capitalized on agricultural modernization, e-commerce platforms, and rural tourism initiatives. Parallel advancements are evident in governance effectiveness through strengthened grassroots administrative capacity, along with steady improvements in cultural preservation and ecological conservation [6]. However, the persistent rural talent deficit remains a critical challenge. According to the existing policy documents, this paper defines rural young talents as individuals aged 18–45 who are actively engaged in rural development through production, operations, management, services, or innovative entrepreneurship across rural settlements. Characterized by specialized knowledge, experience, technical skills, developmental potential, or leadership capacity, this demographic contributes significantly to rural socioeconomic advancement, including agricultural production, education, healthcare, cultural services, technological innovation, digital commerce, and local governance.

With the intensifying population aging, as well as the persistent large-scale rural-to-urban migrant workers [7], China’s rural areas face significant demographic challenges. Existing literature indicates that more than 20% of China’s rural residents are elderly population [8], resulting in both quantitative shortages and qualitative deficiencies in the youth demographic. Especially in the process of rural revitalization, there is an obvious imbalance between the supply of and need for young talents. In the long term, the talent shortage will also directly lead to limited rural industrial development and disordered governance [6]. Despite some government interventions, including Graduates Support Program and Native Talent Return Initiative providing living and working subsidies [6,9], these measures have demonstrated limited efficacy in addressing the fundamental human capital shortages. This implementation gap suggests the need for more systemic solutions that extend beyond top–down administrative schemes.

In order to addresses China’s rural youth talent deficit, this research aims to answer the following questions. First, what is the typological diversity of young talent participating in China’s rural economic transformation? Second, how are these diversified young talents capitalized through resource exchanges? Third, what are the determinants of talent retention sustainability? To answer these questions and provide some policy implications for the sustainable rural economic transformation, this study reviews the existing literature on rural talent revitalization as well as Chinese population mobility in Section 2, develops an original analytical framework integrating Push–pull Theory (PPT) and Existence–Relatedness–Growth (ERG) theory to categorize talent typologies and explicate their capitalization dynamics through resource exchanges in Section 3, conducts a case study about Yuan Village in Section 4, and finally evaluates the theoretical contributions, practical implications for sustainable rural development policy in Section 5.

2. Literature Review

How to promote urban–rural coordinated development and the comprehensive rural economic transformation have become tough issues for most developing countries. The Rural Revitalization Strategy represents China’s paramount policy initiative for integrated rural economic transformation, succeeding the landmark Precision Poverty Alleviation campaign. Since its formal introduction in 2017, the Rural Revitalization Strategy has emerged as both a cornerstone of China’s policy agenda and a rapidly expanding domain of scholarly research. Chinese scholarship has produced substantive research examining the strategy’s institutional arrangements, socio-economic implications, implementation challenges, and governance mechanisms, reflecting its multidimensional impacts on rural transformation. To address the critical talent deficit in rural China, this paper conducts a systematic review of existing scholarship on rural talent cultivation and retention, and examines the theoretical advancements in China’s population mobility research which is the central conceptual framework informing the investigation.

2.1. Existing Research on Rural Talent Challenge

In both the developed and developing countries, young talents have been universally acknowledged as critical drivers of rural development, particularly in three key dimensions: (1) advancing agricultural modernization, (2) facilitating industrial transformation, and (3) ensuring sustainable regional prosperity [10]. Sociological research conceptualizes rural talents primarily as return migrants who leverage urban-acquired social capital, technological skills, and market opportunities to stimulate rural economic transformation [11,12]. Contemporary regional studies further delineate three prominent talent typologies [13]: agricultural entrepreneurs combining management expertise with technological innovation (e.g., Precision Agriculture Technicians in the Netherlands) [14]; essential public service professionals addressing critical rural needs (e.g., National Health Service Corps in the United States) [15]; and industrial innovators driving digital transformation (e.g., Digital Agriculture Technicians in Kenya) [16].

The global urbanization wave has exacerbated rural talent shortages, prompting scholarly attention to talent outflow dynamics, the structural challenges, and rural talent cultivation systems. Specifically, recent empirical studies have systematically investigated both the magnitude and underlying mechanisms of educated youth and professional outmigration from rural areas [10,15]. Along with the continuous development of e-commerce, the global rural areas face more challenges, including the agri-tech deficit in the Global South and the digital divide in the Global North [17]. To cultivate the endogenous rural talents, the exiting literature also suggests the cooperational education models [18], skill–job alignment strategies [19], pedagogical system [20], and the talent identification mechanisms [21]. This multidimensional research landscape underscores the complex interplay between global urbanization trends and localized rural talent needs.

Specific to China, the rural development policies have undergone significant evolution alongside rapid urbanization processes, transitioning from an initial emphasis on agricultural modernization to the current comprehensive Rural Revitalization Strategy. This paradigm shift reflects a growing consensus that rural regeneration necessitates integrated support systems addressing three fundamental dimensions: (1) industrial transformation, (2) physical infrastructure development, and (3) most crucially, human capital formation. According to the national policy requirements, the talent revitalization is aimed to introduce, cultivate, and retain more talents, especially young talents with professional skills and knowledge [22]. Therefore, academic inquiry into China’s rural sustainable development has undergone a notable conceptual evolution, transitioning from its initial emphasis on industrial revitalization to a growing focus on talent revitalization. Scholars begin to explore mechanisms to leverage human capital advantages as a foundation for the sustainable development of rural areas.

In the existing literature, rural talents are conceptualized as a multidimensional resource critical to rural development [23]. Recent studies have identified emerging talent groups, including new township sages [24], new villagers [25], new farmers [26], and young countryside CEOs [27]. Research on rural young talents has developed along four key trajectories. First, the categorization studies have evolved from the basic occupational classifications [28,29] to more nuanced typologies distinguishing endogenous and embedded types [30], and finally expanded into indigenous, embedded, and returned types based on cultivation needs, geographic origins, and domains of influence [29]. Second, scholars have examined the behavioral patterns and participation logic of the rural young talents in rural revitalization [7,31,32], as well as their migration motivations [33,34,35,36]. Third, the existing literature has also structurally analyzed their multiple barriers to return rural community at the macro, meso, and micro levels [7], as well as their embeddedness challenges from both institutional and public perspectives [31]. Fourth, the scholars also apply the Theory of Planned Behavior to explore the influential factors of the rural talents’ engagement in rural governance and economic transformation [36].

2.2. Existing Research on Population Mobility Across Urban and Rural Areas

Structurally shaped by the urban–rural dual system, China’s population mobility patterns manifest in three distinct typologies: (1) rural-to-urban, (2) urban-to-rural, and (3) rural-to-rural flows. Effective rural revitalization necessitates the establishment of robust talent inflow mechanism capable of stimulating economic transformation through various mobility channels. However, existing literature—both domestic and international—exhibits significant imbalance in its examination of these critical patterns. On one hand, while rural-to-urban migration has been extensively studied regarding its modalities, driving factors, and socioeconomic impacts, urban-to-rural reverse migration has received comparatively less scholarly attention, primarily focusing on driving mechanisms and policy responses [37,38,39,40], with some additional consideration of bidirectional integration flows [41,42]. On the other hand, rural-to-rural mobility patterns remain the most understudied dimension in the exiting literature, despite representing a newly emerging spatial reorganization pattern in China’s evolving urban–rural integration.

2.2.1. Rural-to-Urban Population Mobility

Western nations have undergone earlier urbanization processes, with rural-to-urban migration emerging as the dominant population mobility trend prior to the 1970s. The academic discourse has progressed through two distinct phases. The initial macro-level phase examined the aggregate mobility trends, migrant group characteristics, and social–economic–ecological determinants. Specifically, these studies have elucidated how interregional population flows shape urban agglomeration dynamics while simultaneously analyzing the rural demand factors that influence urban decentralization processes [43,44,45]. In contrast, the subsequent micro-level analyses have focused on individual decision-making mechanisms and migration pathways [46,47]. These investigations have systematically documented the precarious employment conditions and environmental health risks disproportionately affecting rural-to-urban migrant populations [48,49,50].

Along with the rapid urbanization over the past two decades, China has witnessed intensified urban agglomeration, solidifying rural-to-urban migration as the predominant mobility type. This phenomenon has attracted substantial scholarly attention, particularly regarding its scale, underlying mechanisms, and regional consequences [40]. Empirical work identifies three defining spatial modalities, including (1) circulatory short-haul movements, (2) intra-provincial population mobility, and (3) coastward migratory streams [40,51,52]. More specifically, the literature demonstrates that economic variables exert significant influence on individual migration decisions, particularly including expected income differentials, non-agricultural income shares, and public investment. It is notable that China’s household registration (hukou) system has functioned as a dualistic institutional mechanism in governing China’s population mobility. While administratively constraining cross-sectoral mobility through its regulatory framework, it has paradoxically stimulated rural–urban migration by institutionalizing and amplifying urban–rural opportunity disparities [53,54,55]. Despite exacerbating rural human capital depletion, these demographic transformations generate three positive impacts on the urban sector: (1) labor supply expansion, (2) deceleration of aging rates, and (3) improved dependency ratios via working-age population replenishment [40,44,56].

2.2.2. Urban-to-Rural Population Mobility

While the western countries experienced the demographic transition from agglomeration to de-agglomeration, the American scholars put forward the concept of “counter-urbanization” [57]. Subsequent scholars have systematically examined this phenomenon through multiple analytical lenses: its spatiotemporal variability and fluctuations [58,59], the socioeconomic diversity of urban-to-rural migrant populations [60,61,62], the multi-scalar driving mechanisms encompassing both macro-structural and micro-level factors [63,64], and its multifaceted impacts on rural communities [59,65]. Moreover, the rural gentrification phenomenon in this counter-urbanization process has also been examined, with particular attention to the demographic “youngification” trend among in-migrants [66]. This research collectively establishes the counter-urbanization as a complex, multidimensional phenomenon reshaping rural spaces in post-industrial societies.

Due to the increased living costs in the urban areas and the policy support for rural development, more evidence of reverse urbanization have gradually appeared in China, and this urban-to-rural mobility has challenged the traditional understanding of linear urbanization. Correspondingly, the existing literature identifies several distinct urban-to-rural mobility types with specific demographic characteristics: (1) the “returning entrepreneur” type, predominantly comprising the former rural migrant workers who return to hometowns to start businesses; (2) the “wellness-oriented migrant” type, mainly consisting of retirees and middle-class individuals seeking health-focused residential mobility; and (3) the “policy-facilitated” type, primarily consisting of the officially dispatched village Party secretaries and technology commissioners implementing development programs [67].

2.2.3. Rural-to-Rural Population Mobility

According to the existing literature, the rural-to-rural population mobility has been observed across South Asia and West Africa, and the migrant groups are mainly married women and plantation farmers [68]. In Bangladesh, rural-bound adolescents aged 15–30 demonstrate particularly high migration prevalence [68,69], while in Northern Ghana, land fertility differentials emerge as the predominant driver of youth mobility [70]. This cross-regional analysis reveals three fundamental determinants shaping population mobility patterns: (1) human capital endowments, (2) economic considerations, and (3) social network characteristics. Notably, the acquisition of arable land and establishment of farm enterprises emerge as the predominant drivers motivating farmers’ rural-to-rural relocation decision [70,71].

The comprehensive implementation of China’s Rural Revitalization Strategy has generated uneven development outcomes, with government pilot programs and competitive rural industries exacerbating intra-rural disparities across towns. This spatial inequality has precipitated rising rural-to-rural population mobility, a phenomenon that remains significantly understudied within the broader urban–rural continuum. Emerging Chinese literature has begun examining this trend through three analytical dimensions: (1) migrant characteristics and motivations [72,73], (2) comprehensive cost–benefit analysis of the mobile population [74], and (3) multi-dimensional impact assessments [75].

Specifically, Wang (2021) [74] applies PPT to reveal how inter-village disparities drive relocation decisions, particularly between key and general villages. Based on an empirical study, the author identifies five key determinants influencing rural-to-rural mobility patterns within municipal territories: (1) differential productivity levels, (2) employment opportunity gaps, (3) public service accessibility, (4) living cost variations, and (5) cultural–linguistic factors. Zhou (2024) [75] suggests this flow type yields positive externalities for the rural sector, including enhanced industrial development, improved community governance structures, and facilitated ethnic integration at the county level.

2.3. Research Gaps

On the one hand, the evolving literature has demonstrated both the conceptual sophistication and practical relevance of talent revitalization in China’s rural transformation context. On the other hand, across urbanization and counter-urbanization phases, the changing population mobility forms always receive much academic attention. However, three critical gaps persist in current scholarship.

First, while industrial revitalization has dominated the research on China’s Rural Revitalization Strategy, the systematic investigations of talent revitalization remain scarce, particularly regarding its capitalization mechanisms and multidimensional impacts. Second, despite abundant studies on rural-to-urban migration, scholarly attention to urban-to-rural reverse migration remains limited, and rural-to-rural flows—potentially signaling a new urban–rural development phase—constitute a particularly understudied phenomenon. Third, the prevailing research tends to examine singular mobility types in isolation, but neglecting the complex coexistence of multiple flow types within the shared development contexts and their differential decision-making processes and resource exchange dynamics.

To address these gaps, this study makes four substantive contributions: (1) developing an integrated theoretical framework combining Push–Pull Theory (PPT) and Existence–Relatedness–Growth (ERG) theory to analyze the mobility mechanisms of various young talent; (2) elucidating the capitalization processes through resource exchange analyses; (3) employing Yuan Village as an empirical case to document China’s emerging mobility diversity; and (4) generating policy-relevant insights for talent-supported rural economic transformation. Through this multidimensional approach, the research aims to advance the understanding of China’s evolving urban–rural continuum while providing practical guidance for more comprehensive rural economic transformation.

3. Theoretical Framework and Mechanism Analysis

Since the nationwide implementation of China’s Rural Revitalization Strategy has yielded the uneven development within the rural sector, this spatial polarization has given rise to a distinct rural-to-rural population mobility pattern, making China’s urban–rural migration continuum more complex. Like other mobile demographic groups, young talent flows are shaped by multifaceted push–pull factors, yet they occupy a particularly pivotal role in both sending and receiving communities. After flowing in the rural areas, the rural talents are formally capitalized through resource exchange with multiple local entities. To examine the individual mobility decision-making mechanisms, this research employs the PPT and ERG Theory to classify the existing rural talents into various types and interpret their mobility motivations, capitalization mechanisms, and potential future mobility from a dynamic perspective.

Regarding the applicability of these two theories, PPT has been widely utilized in population mobility research. It proves particularly relevant for analyzing the emerging “urban-to-rural” and “rural-to-rural” mobility patterns examined in this study, as it effectively explains both the push factors at origin locations and pull factors at destinations. Furthermore, the theory highlights the dynamic nature of migration processes—when villages fail to meet young talents’ needs, new push–pull factors emerge in their decision-making, leading to subsequent mobility to other areas. To better systematize talent needs and human-centric factors within the original push–pull framework, this study innovatively incorporates ERG theory. This integration offers a more flexible and realistic approach to understanding complex, context-dependent human motivations. The resulting theoretical framework provides enhanced explanatory power for analyzing talent mobility, retention, and re-migration dynamics from both macro and micro perspectives.

3.1. Theoretical Framework and Rural Talent Categories

According to PPT, youth talent mobility is shaped by four interrelated factors: (1) push factors arising from disadvantageous conditions in origin locations, (2) pull factors stemming from advantageous conditions in destination locations, (3) intermediate factors primarily involving policy and institutional influences, and (4) individual factors including objective characteristics such as age and educational attainment. To account for the subjective, needs-driven nature of multiple talent mobility patterns, this study adapts the traditional PPT framework by incorporating ERG theory, which focuses on three fundamental need dimensions that shape migration decisions: (1) existence needs regarding the physical conditions including income levels and job stability, (2) relatedness needs regarding the social factors such as interpersonal relationships and sense of community belonging, and (3) growth needs regarding the professional development opportunities including career advancement potential and achievement recognition.

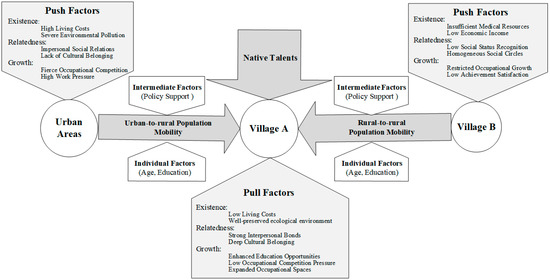

The proposed theoretical model (Figure 1) suggests that youth talent mobility occurs when outflow locations push talents away by failing to meet their ERG needs, while inflow locations pull talents by fulfilling these needs. Specific to the need type, the existence dimension comprises economic income and job stability; the relationship dimension includes interpersonal interaction and a sense of belonging; and the growth dimension encompasses career development opportunities and a sense of achievement. Compared to traditional economic push–pull factors, this needs-based PPT framework offers a more nuanced understanding of the decision-making processes among young educated migrants, particularly within China’s uneven rural economic transformation context.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework for rural young talents categories.

According to the existing literature, this study conceptualizes rural talents as individuals who facilitate rural industrial transformation and ensure sustainable prosperity. These individuals are characterized by significant economic value, innovative capacity, and a synergistic combination of tangible assets (e.g., education, technical skills) and intangible capital (e.g., creativity, social networks). Despite sharing the same inflow locations (such as Village A in Figure 1), rural talents now originate from diverse outflow locations and are influenced by varying push–pull factors. Based on their outflow origins, rural young talents can be classified into three categories: (1) urban-to-rural talents moving from the urban sector to the rural sector, (2) inter-village young talents from the rural-to-rural floating population, and (3) native rural talents, who belong to the non-mobile population (such as local residents of Village A).

The three types of young talents migrate when their subjective needs remain unsatisfied, with distinct variations across the existence, relationship, and growth dimensions. In the existence dimension, due to rising urban living costs and environmental degradation, urban young talents relocate to Rural A seeking lower expenses and better ecological conditions, while the inter-village young talents face inadequate basic medical resources and economic opportunities in Village B compared to Rural A. Regarding relationship needs, both urban and native young talents prioritize enriched social connections and cultural identity, while the inter-village young talents focus on the social status recognition and social network expansion. Concerning growth needs, urban-to-rural young talents emphasize the workload intensity, inter-village talents prioritize career advancement opportunities and professional achievements, and the native young talents are concerned more with the entrepreneurial space than employment opportunities.

3.2. Talent Capitalization Mechanism Through Resource Exchanges

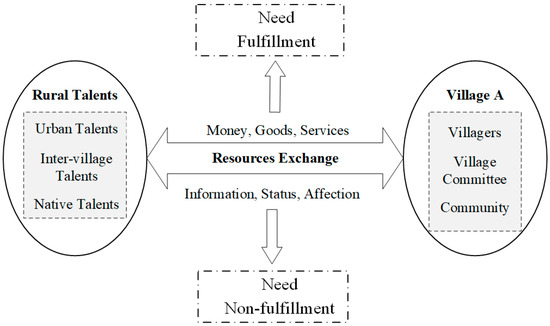

Upon relocating to rural areas, these three types of talents significantly contribute to rural economic transformation through the resource exchanges between young talents and local actors. On the one hand, these individuals possess diverse resource portfolios, including financial capital, information access, social status, and specialized labor capacities, positioning them as key actors in rural economic transformation. On the other hand, the resource exchanges between these talents and multiple stakeholders (villagers, village committees, and the community) lead to varying need fulfillment outcomes, which subsequently influence their future migration directions. To systematically analyze these dynamic processes, this study develops an analytical framework (Figure 2) to examine the bidirectional resource exchanges between rural young talents and Village A stakeholders.

Figure 2.

Talent capitalization mechanisms through resource exchanges.

This study examines talent capitalization through the lens of resource exchange interactions, involving six fundamental types significant resources in rural economic transformation: money (which can be converted into actual investment), goods (tangible commodities and materials), services (professional or property assistance), information (about the technology and market), status (social recognition), and emotion (spiritual connections). Based on their respective resource endowments and needs, urban-to-rural, inter-village, and native talents establish unique exchange relationships with local actors, including villagers, village committees, and the broader village community.

Specifically, urban-to-rural talents primarily exchange services, information, and monetary investments for commodities and emotional belongings with the local actors. Their interaction with villagers is characterized by continuous social engagement, enabling them to integrate into the rural community while addressing their relatedness needs. Inter-village talents contribute specialized labor and status enhancement to the village community; in return, they can receive the improved services and social recognition. In addition, this service-associated relationship also helps them to fulfill growth needs, such as career advancement and professional achievement. Similarly, native talents leverage their local knowledge and cultural capital to secure entrepreneurial opportunities and status validation from the village committee. However, different from these external stakeholders, their deep emotional connection to the community reinforces their long-term commitment to rural economic transformation.

3.3. A Dynamic Analysis Framework on Talent Retention and Secondary Mobility

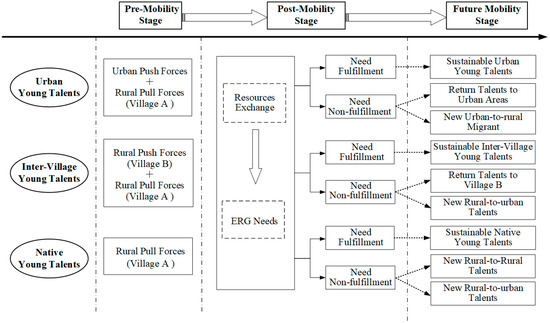

As illustrated in Figure 1, inadequate resource exchanges in Village A may generate new push factors, potentially triggering secondary population mobility and undermining sustainable talent retention. This dynamic process warrants careful examination, because it does not only reveal fundamental principles of talent inflow that can stimulate rural economic transformation but also identifies critical junctures that inform policy interventions for talent retention. Building upon our categorization of rural young talents, this study advances the analytical framework (Figure 1) by incorporating a temporal dimension to transcend static explanations of mobility causation (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dynamic analysis framework for talent retention.

Figure 3 provides a novel analytical tool for deconstructing the complex, iterative nature of rural talent flows. By tracing how exchange deficiencies may transform Village A from an inflow destination into an origin of outflow, we reveal the precarious nature of rural talent retention and identify policy-sensitive intervention points in the mobility cycle. Specifically, the dynamic rural talents’ mobility can be divided into three stages: (1) pre-mobility stage when the mobility decisions of various rural young talents are shaped by distinct push–pull factors across three categories; (2) post-mobility stage when all talent categories are capitalized through multidimensional exchanges with various local actors; and (3) future mobility stage when differential need satisfaction produces distinct future mobility scenarios for each talent category.

Specific to the future mobility stage, rural young talents are fundamentally determined by their level of need satisfaction. For urban-to-rural talents, successful adaptation manifests in their transformation into sustainable rural talents who maintain enduring connections between urban and rural contexts while achieving stable integration in Village A. Conversely, when their core needs cannot be fulfilled, these individuals face two potential trajectories: return to urban areas or secondary migration to alternative rural destinations offering better need satisfaction prospects.

For the inter-village talents, those achieving sufficient need satisfaction evolve into the stabilized rural-to-rural talents in Village A, serving as bridges between different rural communities. If facing inadequate satisfaction, these talents may choose the reverse migration to the original villages, tertiary migration to new rural destinations, or the migration to urban areas.

If the ERG needs can be satisfied by the local conditions, the local rural young talents may involve into the local developers with great significance in regenerating the multi-dimensional rural spaces. However, the unmet needs may also trigger the loss of local young talents. Under such conditions, they either choose to search better opportunities within the rural sector or move to the urban areas contributing to urban prosperity. Different from the other two talent categories, the native young talent mobility decisions often involve stronger emotional and familial considerations.

By incorporating temporal dynamics with the original PPT-ERG theoretical framework, this three-stage model reveals that the critical exchange thresholds determine the retention outcomes of various rural talents, and the feedback loop reinforces the cycle of push–pull factors. The critical exchange thresholds for retention reveal the cyclical nature of push–pull dynamics.

4. Case Study from Yuan Village

To examine the mechanisms through which young talents are capitalized in rural economic transformation, we present a specific case study. Situated in Northwest China’s plain region with developed transportation infrastructure, Yuan Village has undergone a remarkable transformation over two decades. Initially leveraging its folk cultural heritage, the village experiences rapid tourism industry expansion before reaching its current business model focusing on industrial innovation and brand development.

4.1. Methodology

4.1.1. Research Area

The selection of Yuan Village is particularly instructive for three key reasons. First, its developmental journey encapsulates both the opportunities and challenges characteristic of comprehensive rural modernization processes. Second, the village’s growth has been fundamentally enabled by the continuous inflow of young talents through tourism entrepreneurship, e-commerce initiatives, and cultural preservation efforts. These individuals have not only contributed to industrial development but also played crucial roles in enhancing rural governance systems and introducing innovative practices, forming comprehensive rural economic transformation. Last but not least, our preliminary research has identified an emerging rural-to-rural mobility pattern in this village. This phenomenon presents a valuable opportunity to study an alternative talent circulation model, as well as fresh theoretical insights for contemporary retention challenges.

However, Yuan Village currently faces significant challenges in sustaining this talent-driven development model. A declining rate of return migration among the native young professionals has resulted in growing shortages of skilled labor, creating bottlenecks for business expansion and weakening local governance capacity. This paradox of initial success followed by emerging sustainability concerns makes Yuan Village an ideal setting for examining talent retention dynamics.

4.1.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

This study adopts the World Health Organization’s age classification framework while adapting it to China’s rural context, with a specific focus on young talents aged 18–44 years. The research aims to examine need satisfaction patterns and capitalization mechanisms among various categories of young professionals in rural revitalization contexts. The investigation combines both qualitative and quantitative approaches to ensure comprehensive data collection and robust analysis.

The research was conducted in Yuan Village and involved two distinct participant groups. First, in-depth interviews were carried out with three village cadres who hold official positions in local governance structures. Second, an extensive survey was organized involving 39 other young talents, which included 3 young village cadres within this larger sample. Village cadres in this study are operationally defined as individuals serving in the village Party organization, village committee, or their affiliated organizations. These individuals exercise public authority, manage community affairs, and deliver essential public services, making them crucial actors in rural development processes.

The study employs a mixed-methods approach to systematically analyze multiple dimensions of rural talent dynamics. The research design specifically investigates satisfaction levels among different talent categories, resource exchange relationships with various stakeholders, and emerging patterns of talent mobility that are transforming rural economies in contemporary China. To achieve both depth and breadth of understanding, the methodology incorporates two primary data collection techniques: semi-structured interviews and snowball sampling.

The fieldwork followed a carefully structured two-phase approach. In the initial phase, researchers identified and interviewed three strategically selected young talents holding cadre positions, comprising one urban-origin talent and two native-origin talents. These semi-structured interviews, each lasting about 60 min, served as foundational cases for understanding core issues. The second phase expanded the sample through snowball sampling techniques, ultimately conducting in-depth interviews with a total of 42 young talents across three distinct categories: urban young talents (16 participants), native young talents (11 participants), and inter-village young talents (15 participants).

All interview data were systematically recorded and categorized according to standardized protocols. The research team documented comprehensive details including participant demographics, precise interview durations, and substantive content areas covered in each session. These meticulously organized data are presented in Table 1 of the study, providing full transparency regarding methodological procedures and enabling rigorous analysis of emerging patterns in rural talent circulation and development. The combination of qualitative depth and quantitative breadth in the research design facilitates nuanced understanding of the complex relationships between talent mobility, need satisfaction mechanisms, and rural transformation processes in contemporary China.

Table 1.

Semi-structured Interviews with young talents.

4.1.3. Systematic Coding Framework

To ensure rigorous analysis of qualitative interview data, this study implements a structured coding framework through the following procedures. Prior to analysis, the research team drafted a preliminary codebook based on the study’s theoretical framework and research questions, including primary codes reflecting broad themes (e.g., “existence factor”, “relatedness factor”, and “growth factor”); secondary codes for sub-themes (e.g., “income”, “employment opportunity”, “investment opportunity”, “occupational pressure”, “ecological environment” under “existence factor”); operational definitions and exclusion criteria for each code to ensure consistency (Table 2).

Table 2.

Coding framework for rural talent ERG needs.

4.2. Diversity in Rural Talents and Complexity of Population Mobility

The urban-to-rural talent flow demonstrates a clear push–pull mechanism shaped by both policy interventions and individual factors. In the past decade, China has introduced a series of structural reforms, particularly in land systems, which has enhanced farmers’ property rights and attractions for urban capital. Concurrently, urban push factors are becoming increasingly pronounced across all dimensions of ERG needs. In terms of existence needs, escalating housing prices and severe air pollution create substantial disincentives for urban residence. Compared to rural settings, the relatedness needs of young talents are also poorly met in urban environments, with 72% of surveyed talents reporting weaker community ties. Moreover, the intense professional competition in urban professional sectors makes the growth needs compromised for the young talents, contrasting sharply with the emerging opportunities in Yuan Village’s. It is notable that the professionals aged 35+ particularly value the lower work intensity in Yuan Village, with 69% citing this as a decisive factor in mobility decisions. These urban-to-rural talents typically assume roles as village officials, agri-tech specialists, or tourism entrepreneurs to drive rural economic transformation.

Our research identifies a novel rural-to-rural migration stream, characterized by distinct occupational and motivational patterns. These inter-rural talents are primarily engaged in tourism, catering, and agri-processing industries. The key pull factors include industrial clustering, significant wage premiums, and existing social networks. Institutional interventions have amplified this trend through targeted infrastructure investments and corporate-style village governance model, which attract young talents from adjacent villages like Xili and Dongzhou. According to the in-depth interview, rural-to-rural talents more often consider their personal suitability for rural work environments, which is as important as economic factors. This finding suggests a paradigm shift in career aspirations among younger generation, which may have significant implications for future policy designs.

In the field trip, we observed two distinct subgroups of the native talents that make various contributions to local economic transformation: (1) return migrants who used to work in the urban areas and (2) non-mobile native talents who have been consistently working and living in Yuan Village. According to the existing literature [67], the return migrants, typically with urban education and work experience, are the most common native talent type in rural China. These individuals are pulled back primarily by strong kinship networks, cultural continuity, and promising earnings. The non-mobile native talents consist largely of multigenerational residents who operate artisanal businesses or lead cultural preservation initiatives. This demographic cohort benefits from three distinct advantages: (1) deep-rooted social capital that facilitates trust-based economic transactions and community cooperation, (2) competitive first-mover advantages in market positioning and local knowledge utilization, and (3) the robust intergenerational training systems that ensure continuous skill transmission, particularly in traditional crafts and agricultural techniques. Collectively, these native talents play critical roles as professional managers, e-commerce operators, and cultural heritage practitioners, forming the essential backbone of endogenous rural development in Yuan Village.

4.3. ERG Needs of Diversified Talents Categories

Influenced by various push–pull factors, all three talent groups demonstrate fundamental requirements in the ERG dimensions, though with distinct emphases and expectations (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparative analysis of ERG need across three talent categories.

According to the interview data, about 87.5% of urban young talents primarily seek less professional pressure and more investment opportunities in Yuan Village, along with improved ecological conditions, including better air quality and more green spaces. They also prioritize access to both essential medical infrastructures and urban-style recreational amenities, including village entertainment districts and community amusement facilities. In contrast, rural-to-rural talents focus more on foundational living standards, with primary consideration given to (1) affordable housing, (2) stable utility infrastructure, and (3) functional workspaces. Native talents demonstrate distinct residential preferences, prioritizing three key aspects: (1) homeownership opportunities through village housing schemes, (2) family-oriented community infrastructure (particularly educational and recreational facilities, and (3) cultural preservation initiatives including heritage centers and traditional craft workshops. These variations reflect each group’s distinct roles and adaptation requirements in rural economic transformation.

The relatedness needs of the three talent categories also reveal profound differences due to their distinctive social orientation and cultural expectations. To seek status elevation through the identity of “rural pioneer”, more than 60% of urban migrants typically prefer to develop broad networks through professional associations and the relative interest groups rather than deep community bonds. Due to the cultural needs on novel experiences, they usually actively participate in the village’s annual cultural festivals. Rural-to-rural talents show contrasting patterns that they usually secure jobs through relative introductions and consider marriage prospects as a key decision factor, indicating their expectation on strong-tie networks. These talents require specific cultural assimilation support, such as bilingual signage and orientation programs. In contrast, native professionals maintain different priorities in upholding kinship obligations and cultural tradition transmission. Their social needs usually merge modern and traditional norms, providing them unique position as cultural bridges in the cultural space regeneration.

While all groups share certain fundamental expectations for policy support, their career aspirations diverge significantly. Common needs include startup subsidies and education guarantees for children. Comparatively speaking, urban-to-rural talents specifically seek low-competition markets where they can leverage urban–rural knowledge gaps. Rural-to-rural talents prioritize job stability, skill certification, and better education conditions. Native developers combine profit motives with hometown loyalty and actively blend traditional and innovative techniques in their work. Thus, their growth needs extend beyond the pure economic returns to include legacy-building opportunities and public recognition of their contributions.

4.4. Talent Capitalization Through Resource Exchanges

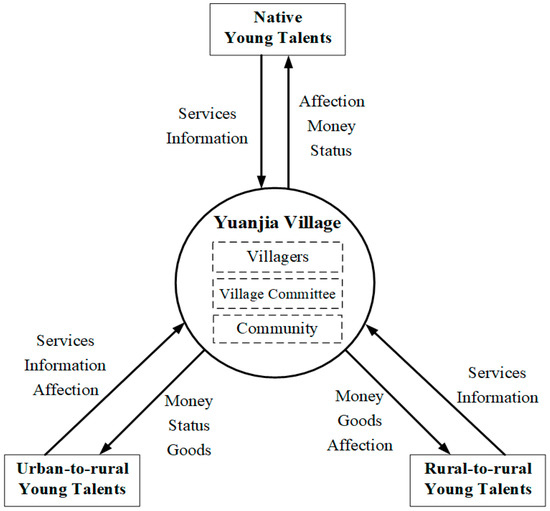

This study identifies three distinct talent capitalization mechanisms through resource exchanges between rural young talents and Yuan Village, each characterized by unique contributions and expected returns. The interview data reveal how different talent categories engage in mutually beneficial relationships with the village, contributing to its ongoing economic transformation (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Resource exchanges in Yuan Village.

Urban-to-rural young talents, including college graduate village officials and imported professionals, engage primarily in knowledge-intensive exchanges with Yuan Village. These individuals contribute valuable human capital through professional administrative services for village governance, strategic guidance for local enterprises, and innovative entrepreneurial ventures in tourism and cultural industries. In return, the village offers a structured compensation system featuring initial rent-free periods, formal recognition as “valued talents” within the community, and exclusive rights to commercialize local specialty products. This exchange framework enables urban migrants to apply their advanced education and professional skills while accessing entrepreneurial opportunities that is unavailable in competitive urban markets.

Young migrants from neighboring villages, predominantly aged 35+ with vocational education backgrounds, engage in culturally specialized exchanges. Their contributions focus on the artisanal food production, traditional handicrafts, and folk art preservation. In return, these talents seek a combination of economic betterment and emotional fulfillment, including the opportunities to establish new family connections. These dual incentives distinguish rural-to-rural talents from other talent categories, and they also underscore the importance of both material and social factors in their mobility decisions.

Native young talents demonstrate the exchange pattern deeply rooted in local social capital. Facilitated by the pre-existing social networks within the community, they make contributions emphasizing the operational expertise in business strategy and the dissemination of management skills. The return structure for native talents includes both financial compensation and non-material benefits. According to the interview, more than 70% of native talents prioritize emotional returns over purely economic gains, including familial bonds and cultural continuity. This preference highlights the unique psychosocial contract between native professionals and their home community, where social and emotional considerations significantly influence their participation in development initiatives.

This tripartite exchange model (Figure 4) demonstrates how Yuan Village has successfully capitalized complementary resource flows as well as different talent categories. To enable these exchanged, key institutional factors include (1) multidimensional value recognition systems, (2) flexible compensation mechanisms, and (3) an integrated ecosystem fostering productive interactions among knowledge capital, professional networks, and specialized competencies. These findings suggest that effective rural talent policies should move beyond uniform incentive schemes to develop differentiated approaches that accommodate various talent categories.

4.5. Talent Retention Dynamics in Yuan Village

The long-term retention of young talents in Yuan Village hinges critically on the village’s capacity to adequately fulfill their multidimensional needs through sustainable resource exchanges. Our analysis reveals distinct future mobility trajectories for each talent category, shaped by varying degrees of need satisfaction across existence, relatedness, and growth dimensions.

Urban-to-rural talents face a tripartite mobility decision influenced by professional considerations. Approximately 46% plan to return to cities when urban networks and career ladders prove more attractive, while 25% may pursue secondary rural relocation if alternative villages offer superior entrepreneurial conditions. Moreover, this group makes mobility decisions heavily based on career development factors, emphasizing the measurable professional growth as opposed to clear advancement pathways.

As the most mobile cohort, rural-to-rural talents demonstrate four potential trajectories. Nearly 33% hope to move urbanward when economic aspirations outweigh rural ties, while 15% would like to return to home communities if the origin villages develop competitive advantages. Another 10% select new rural destinations that can offer better matching resource, particularly when marriage opportunities or sector-specific advantages emerge. The remaining 42% of migrants typically maintain temporary development in Yuan Village while accumulating essential resources.

Native talents exhibit bifurcated mobility patterns when core needs remain unmet. A majority of highly educated young villagers plan to join rural-to-urban migration flows, primarily motivated by urban pull factors, including (1) superior career prospects, (2) enhanced healthcare and educational infrastructure, and (3) greater professional development potential. Due to the marked advantages in economic transformation and their embedded social capitals, the remaining villagers (especially the elder ones) enter a holding pattern, while few plan to move to neighboring villages. This delicate balance reflects their unique position between traditional attachments and modern aspirations.

However, current need satisfaction gaps reveal structural limitations in Yuan Village’s talent ecosystem. Some native young talents report wakening hometown identity, while most of the urban-to-rural talents feel limited social connection. More specifically, the unclear promotion paths, unsatisfied education conditions, as well as inadequate achievement recognition may become the new push factors for various talents.

To better substantiate the dynamics of ERG fulfillment and re-mobility, this paper provides three specific individuals’ cases. The first one is the case of Mrs. Xu, as a representative example of urban-to-rural talent migration and successful retention in Yuan Village. Mrs. Xu, a bachelor’s degree holder with international experience in the United States for two years and Hong Kong for nearly a decade, transformed from a housewife for over ten years to an entrepreneur in Yuan Village since 2018. Her decision to relocate was motivated by limited employment prospects and salary constraints in urban areas due to her lack of formal work experience, coupled with the slower pace of life, superior air quality, and perceived business opportunities in Yuan Village. The analysis of Mrs. Xu’s case through the ERG theoretical framework reveals multiple dimensions of need fulfillment that explain her successful retention. In terms of existence needs, Mrs. Xu has achieved substantial financial success through her homestay business and shareholding benefits. Additionally, her formal membership in the village collective and allocation of homestead property provide material security and asset ownership. Regarding relatedness needs, her appointment as deputy director of the village committee signifies the deep respect and recognition she has earned from local residents, which has further facilitated her social embeddedness within village governance structures and daily life. In the growth dimension, her transition from urban housewife to rural entrepreneur and village leader represents substantial career advancement and self-actualization.

The second case comes from Mrs. Zhou, a native talent who returned to Yuan Village but plans to eventually leave, presenting an important contrast to Mrs. Xu’s successful retention. As one of the earliest returnees to Yuan Village, Mrs. Zhou holds a bachelor’s degree and previously worked as a nurse in urban areas until 2009. Her decision to return was motivated by multiple factors: (1) the substantial life pressures of urban living, (2) the monotonous routines of urban employment, and (3) the emerging investment opportunities in her hometown’s developing tourism sector. An ERG framework analysis reveals a complex pattern of need fulfillment in Mrs. Zhou’s case. Regarding existence needs, she has achieved notable economic success as a pioneer in Yuan Village’s homestay industry, accumulating significant wealth through her entrepreneurial ventures. However, her relatedness needs demonstrate an ongoing tension between rural professional success and urban-oriented family priorities. While deeply embedded in the village’s economic fabric, she has maintained strong connections to urban areas through her children’s education, enrolling them in urban schools and various enrichment programs. The growth dimension presents particular challenges that explain Mrs. Zhou’s planned departure. Despite her business accomplishments, she perceives limitations in long-term professional development opportunities and overall quality of life in Yuan Village compared to urban centers. Her intention to eventually relocate to accompany her children’s educational journey underscores the persistent appeal of urban infrastructure and living conditions, even for successful rural entrepreneurs.

The contrast between Mrs. Zhou’s and Mrs. Xu’s outcomes highlights the importance of understanding diverse motivational patterns among different categories of rural talents, as well as the necessity for integrated rural development strategies that address the full spectrum of human needs and aspirations. Only through such comprehensive approaches can rural communities hope to achieve lasting talent retention across generations.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

This study advances our understanding of rural talent mobility by developing a comprehensive theoretical framework grounded in Push–Pull Theory and ERG theory. Our findings reveal three distinct patterns of talent flows: urban-to-rural talents, rural-to-rural talents, and native talents. Each of them demonstrates unique need profiles and exchange dynamics in rural economic transformation. Specifically, the emergence of rural-to-rural mobility challenges the conventional urban–rural dichotomies and suggests more complex circulation patterns are developing in China’s rural transformation. These flows are fundamentally driven by differential need satisfaction across existence, related-ness, and growth dimensions, with urban-to-rural talents prioritizing professional opportunities, rural-to-rural talents emphasizing stable employment and social integration, with the native talents valuing cultural continuity.

The resource exchange perspective proves particularly valuable in explaining retention challenges. While all talent groups engage in material, social, and emotional ex-changes with local actors, current limitations in exchange adequacy create systemic barriers to long-term retention. Our observed mobility decisions have underscored the precarious nature of rural talent retention and suggested that many young professionals view rural postings just as temporary career moves. This finding aligns with broader literature on skilled migration in developing contexts and adds specificity through our typological analysis of different talent categories.

This research yields several important theoretical and practical contributions to rural economic transformation and talent mobility studies. Theoretically, we demonstrated the value of integrating temporal dynamics with Push–Pull Theory to understand how short-term interactions shape long-term mobility trajectories. Our tripartite typology of rural young talents provides a nuanced framework that moves beyond conventional urban–rural binaries in migration research.

However, the representativeness of Yuan Village warrants further consideration. Benefiting from convenient transportation and a strategic location, Yuan Village has successfully developed its catering and cultural tourism industries. Existing literature highlights the critical role of rural tourism in China’s rural development and restructuring, particularly within the context of rural revitalization [76,77]. Given this, the talent shortage faced by Yuan Village reflects a common challenge in rural areas undergoing industrial transformation. Moreover, the Chinese government has implemented various policies to attract young talent to rural areas, such as the College Graduate Village Officials Program, which extends to most villages nationwide. Despite these efforts, retaining such talents remains a persistent and widespread issue across rural China. Thus, Yuan Village’s experience offers valuable insights into both the opportunities and obstacles in rural talent retention, as well as a challenge shared by many developing rural regions.

At the same time, Yuan Village possesses unique characteristics that cannot be easily replicated in other villages. To translate these distinctive features into comprehensive policy recommendations, this study identifies two key success factors. First, Yuan Village’s distinctive food culture serves as a significant attraction for tourists and young talent alike, while the associated cultural sentiments constitute a core resource driving its economic and social transformation. In this context, other villages should identify and develop their own cultural assets—including architectural traditions, folk customs, landscape features, and agricultural heritage—and strategically transform them into unique tourism resources and collective economic assets. Second, unlike Yuan Village, many rural communities face difficulties in establishing effective cooperative economic organizations due to insufficient collective leadership, which hinders consensus-building among villagers and weakens grassroots governance capacity. Yuan Village’s experience in developing strong collective governance structures may offer valuable insights for addressing these institutional challenges in other rural contexts.

Drawing upon both the representative and distinctive characteristics of Yuan Village’s development experience, this study proposes concrete policy recommendations to enhance talent retention in rural revitalization efforts. These recommendations address fundamental prerequisites for rural development while accommodating the diverse needs of young professionals. The study identifies two critical prerequisite factors for sustainable rural development: capacity building in grassroots organizations and physical infrastructure improvement. Municipal and county governments should prioritize comprehensive economic support systems that simultaneously address multiple dimensions of rural development. Specifically, policy interventions should focus on generating stable employment opportunities tailored to skilled young professionals; cultivating entrepreneurial ecosystems through targeted support programs; upgrading critical transportation, digital, and utility infrastructure, and enhancing the quality and accessibility of medical and educational services. These foundational measures will satisfy young talents’ basic livelihood requirements while simultaneously creating conditions for their long-term professional growth and social integration.

This study proposes a targeted framework to address the distinct needs of three key talent categories in rural revitalization efforts. Each intervention strategy is carefully designed to align with the specific motivations and challenges characteristic of different talent groups while contributing to broader rural development objectives. For professionals migrating from urban areas, the primary intervention focuses on creating transitional living conditions that balance rural authenticity with modern conveniences. Municipal authorities should implement comprehensive livability upgrades, including village beautification programs that enhance public spaces while maintaining local character. Critical infrastructure improvements must address waste management systems and sewage treatment facilities to meet urban standards. Concurrently, the development of contemporary cultural and recreational facilities, such as digital community centers and mixed-use gathering spaces, can help mitigate potential cultural shock while fostering social integration. The strategy for locally rooted professionals emphasizes cultural preservation and kinship-based economic support systems. Village committees should establish youth engagement programs that actively document and celebrate traditional customs through intergenerational knowledge transfer initiatives. Economically, the implementation of family-style entrepreneurship platforms offers particular effectiveness, providing access to shared resources, collective financing mechanisms, and mentorship networks within existing social structures. These measures simultaneously honor cultural identity while creating viable career pathways tied to local heritage and community ties.

For professionals working across rural communities, the intervention framework prioritizes economic cooperation and regional integration. The foundation involves restructuring shareholding systems to ensure transparent governance and equitable benefit distribution. Building on this institutional foundation, the development of specialized regional industry clusters should be pursued through coordinated planning, shared infrastructure investment, and joint marketing initiatives. This approach transforms individual village competitiveness into regional economic resilience while maintaining local distinctiveness.

Successful execution of these differentiated strategies requires a multi-level governance approach. For example, county governments should provide technical support and funding coordination while township governments focus on local adaptation and stakeholder engagement. Critical to implementation is establishing robust monitoring systems that track both quantitative retention metrics and qualitative measures of talent satisfaction. Regular feedback mechanisms should inform iterative policy adjustments, ensuring interventions remain responsive to evolving needs of talents and local conditions of villages. This comprehensive framework recognizes that sustainable rural revitalization demands more than uniform solutions. By addressing the specific aspirations and constraints of different talent categories while maintaining strategic coherence across interventions, the proposed approach offers a nuanced pathway to create mutually reinforcing systems where talented individuals find fulfilling opportunities while rural areas benefit from their skills and entrepreneurial energy.

Looking forward, this study can be further developed in three key directions. First, quantitative measurement of need satisfaction thresholds is needed to refine the clear retention strategies. Second, to illuminate how mobility decisions evolve over time, longitudinal investigation into this case is needed. Third, to test the generalizability of our findings, we also need comparative analysis across different rural contexts. Along with the progress of China’s rural revitalization strategy and the global rural economic transformation efforts, continued attention to these dynamics is essential for achieving sustainable talent-driven rural economic transformation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.; Methodology, C.S.; Formal analysis, Y.L.; Investigation, Y.L.; Resources, C.S.; Writing—original draft, Y.L.; Writing—review & editing, C.S.; Supervision, C.S.; Project administration, C.S.; Funding acquisition, C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Humanities and Social Science Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (Grant No. 20YJC630119).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board, School of Public Policy and Administration, Xi’an Jiaotong University (2025012801) on 28 January 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions, which greatly improved the article. Any errors are the authors’ responsibility.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Robert, C. Rural Development: Putting the Last First; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2014; 256p. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.L.; Yu, Y.T.; Wu, S.R. Experience and Insights from Rural Revitalisation in Other Countries. World Agric. 2018, 12, 168–171. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gartner; William, C. Rural tourism development in the USA. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L. Lessons from Japan’s Rural Development Experience for China’s New Rural Construction. World Agric. 2012, 6, 24–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.L. Insights from South Korea’s ‘New Village Movement’ for the Sustainable Development of China’s Socialist New Rural Construction. J. South China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2006, S1, 48–51+57. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.X. Practical Explorations into Talent Needs and Solutions for the Rural Revitalisation Strategy. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2021, 1, 161–168. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Luo, M. ‘Leaving the Hometown’ to ‘Returning to the Hometown’: The Action Logic of Youth Participation in Rural Revitalisation, Based on a Questionnaire Survey Analysis of 1,231 Young People in Z City, H Province. China Youth Res. 2019, 9, 11–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.K. Comprehensive Survey and Research Report on China’s Rural Revitalisation in 2021. 2022. Available online: https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=1p4a08c0yy7f0v208n7k0gn0jp659650 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Zhou, X.G. Talent Bottlenecks and Policy Recommendations for Implementing the Rural Revitalisation Strategy. World Agriculture 2019, 4, 32–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The State of Food and Agriculture 2018: Migration, Agriculture and Rural Development. 2018. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/state-food-and-agriculture-2018-migration-agriculture-and-rural-development#:~:text=15%20October%202018%2C%20Rome%20-%20A%20new%20report,economic%20and%20social%20development%20while%20minimizing%20the%20costs (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Stark, O.; Taylor, J.E. Relative deprivation and international migration oded stark. Demography 1989, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.S.; Espana, F.G. The social process of international migration. Science 1987, 237, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stromquist, N.P. World Development Report 2019: The changing nature of work. Int. Rev. Educ. 2019, 65, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (CBS). Digitaal Landbouwarbeid: Huidige en Toekomstige Behoeften aan Competenties; Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2021. Available online: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/publicatie/2021/48/digitaal-landbouwarbeid-huidige-en-toekomstige-behoeften-aan-competenties (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- United States Department of Agriculture (HRSA). Rural Health Workforce Strategy; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/health-care-workforce (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Ndege, N.; Marshall, F.; Byrne, R. Exploring inclusive innovation: A case study in operationalizing inclusivity in digital agricultural innovations in Kenya. Agric. Syst. 2024, 219, 104033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). Rural Development Report 2019: Creating Jobs for Rural Youth. 2019. Available online: https://www.ifad.org/documents/38714170/41190221/RDR2019_Overview_e_W.pdf/699560f2-d02e-16b8-4281-596d4c9be25a (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Gentry, M.; Ferriss, S. StATS: A model of collaboration to develop science talent among rural students. Roeper Rev. 1999, 21, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, A.; Kenyon, P.; Lheude, D.; Sercombe, H. Creating Better Educational and Employment Opportunities for Rural Young People; Australian Clearinghouse for Youth Studies: Hobart, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Deo, M.G.; Pawar, P.V. Nurturing science talent in villages. Curr. Sci. A Fortn. J. Res. 2011, 12, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan, C.M.; Azano, A.; Park, S.; Brodersen, A.V.; Caughey, M.; Dmitrieva, S. Consequences of Implementing Curricular-Aligned Strategies for Identifying Rural Gifted Students. Gift. Child Q. 2022, 66, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Kong, L.H. Rural Talent Revitalisation and High-Quality Development of the Rural Economy: An Analysis of University Graduates Returning to Their Hometowns for Employment. Econ. Issues 2024, 2, 91–97. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.G. Key Points, Development Pathways, and Risk Mitigation of the Rural Revitalisation Strategy. J. Xinjiang Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 39, 25–33. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, P.H.; Gao, J.B. New Rural Elders: Connotation, Role, and Bias Avoidance. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 17, 20–29+144–145. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.G. ‘Urban Returnees’, ‘New Villagers’ and the Construction of a Rural Talent Return Mechanism. Mod. Econ. Explor. 2020, 3, 117–122. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.Z.; Gao, Q.J. The New Farmer Phenomenon and the Construction of a Rural Talent Revitalisation Mechanism: A Dual Perspective of Social and Industrial Networks. Mod. Econ. Explor. 2021, 2, 121–125. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. Diagnosis, and Reconciliation: Village Management from a Multi-Institutional Logic Perspective, Taking the Example of ‘Professional Managers Entering the Village. Mod. Econ. Explor. 2023, 11, 113–123. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Que, M.K.; Xu, J.B.; Li, W. Physical Absence and Identity Loss: The Reconstruction and Embedding Pathways of Young Talent Identity in Rural Revitalisation. Soc. Sci. 2023, 4, 155–160. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pu, Y.Q.; Wang, J. A Four-Dimensional Understanding of the Types of Young Talent Needed for Rural Revitalisation. Front. Econ. Cult. 2023, 11, 69–74. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.X. Rural Talent Revitalisation: Governance Efficiency of Endogenous and Embedded Actors. J. Yunnan Adm. Coll. 2021, 23, 68–76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, C.Y.; Li, H.Y. How Can Youth Talent Contribute to Rural Revitalisation? An Analysis Based on the ‘Embeddedness-Publicness’ Framework. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 23, 50–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, D.Q. From ‘Swallows Not Returning to Their Nest’ to ‘Building Nests to Attract Phoenixes’: Reflections and Countermeasures on the Phenomenon of Young People Leaving Their Hometowns in the Context of Rural Revitalisation. Contemp. Youth Res. 2020, 5, 83–88. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.F.; Guo, L.; Li, W.; Liu, W. A Study on Rural Youth Returning to Their Hometowns for Employment and Entrepreneurship in Liaoning Province from the Perspective of Rural Revitalisation. Rural. Econ. Technol. 2019, 30, 236–238. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.L. A Survey on the Influencing Factors of Young Talent Returning to Rural Areas for Employment: A Case Study of City T in Anhui Province. China Hum. Resour. Sci. 2020, 7, 63–73. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.P.; Mao, L.X. An Innovative Model, Current Challenges, and Strategic Choices for Empowering Rural Revitalisation Through Young ‘Rural CEOs’. China Youth Res. 2023, 2, 101–108+118. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Z.F.; Cui, H.Y.; Wang, Z.G. Effective Participation in Rural Social Governance: A Study on the Motivational System of Youth Participation. Contemp. Youth Res. 2022, 1, 34–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ji, N.Y. Return to the countryside: An ethnographic study of young urbanites in Japan’s shrinking regions. J. Rural. Stud. 2024, 107, 103254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. Youth Mobilities and Rural–Urban Tensions in Darjeeling, India. South Asia: J. South Asian Stud. 2015, 38, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.W.; Xie, F. Types of Population Mobility, Driving Mechanisms, and Policy Implications in the Integrated Development of Urban and Rural Areas. J. Qiqihar Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 12, 89–93+104. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Tang, S.S.; Feng, J.X. Patterns, Driving Mechanisms, and Impacts of Urban-Rural Population Mobility: A Review Based on Foreign English-Language Literature. Mod. Urban Stud. 2022, 11, 27–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qian, W.R.; Zheng, L.Y. Building an Institutional Framework for the Two-Way Mobility and Integration of Urban and Rural Populations: An Analytical Framework from the Theory of Rights Openness to the Practice of Village Openness. South. Econ. 2021, 8, 24–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. Analysis of the Push and Pull Factors Affecting China’s Urban-Rural Migrant Population. Chin. Soc. Sci. 2003, 1, 125–136+207. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, P.B.; Oberg, A.; Nelson, L. Rural gentrification and linked migration in the United States. J. Rural Stud. 2010, 26, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puga, D. Urbanization Patterns: European Versus Less Developed Countries. J. Reg. Sci. 2010, 38, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotter, J.W. The Great Migration in Historical Perspectives; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1991; pp. 127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Tacoli, C.; McGranahan, G.; Satterthwaite, D. Urbanisation, Rural–Urban Migration and Urban Poverty. 2015. Available online: https://www.iied.org/10725iied (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Chen, T.H.; Liu, S.H. A Review of Research on Population Mobility in China. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2009, 37, 14940–14942+14948. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, K.; Suttie, D. Rural-Urban Linkages and Food Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Rural Dimension; IFAD Research Series: Rome, Italy, 2016; pp. 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sony, S.; Hossain, M.; Rahman, M. Internal Migration and Women Empowerment: A Study on Female Garments Workers in Dhaka City of Bangladesh. Adv. Appl. Sociol. 2020, 10, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, S. Rural to Urban Migration in Pakistan: The Gender Perspective; Pakistan Institute of Development Economics: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Lin, L.Y.; Ke, W.Q. The Evolutionary Trends of Domestic Population Migration and Mobility: International Experiences and Implications for China. Popul. Res. 2016, 40, 50–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]