Social Responsibility of Agribusiness: The Challenges of Diversity

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How is ASR different from CSR, and should it be separately defined?

- What agribusiness links and to what extent require special attention in implementing social responsibility, especially in the context of its voluntary nature?

- Which agribusiness links implement ASR driven by genuine choice? Which ones do so under coercion or pressure?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. How Is ASR Different from CSR, and Should It Be Separately Defined?

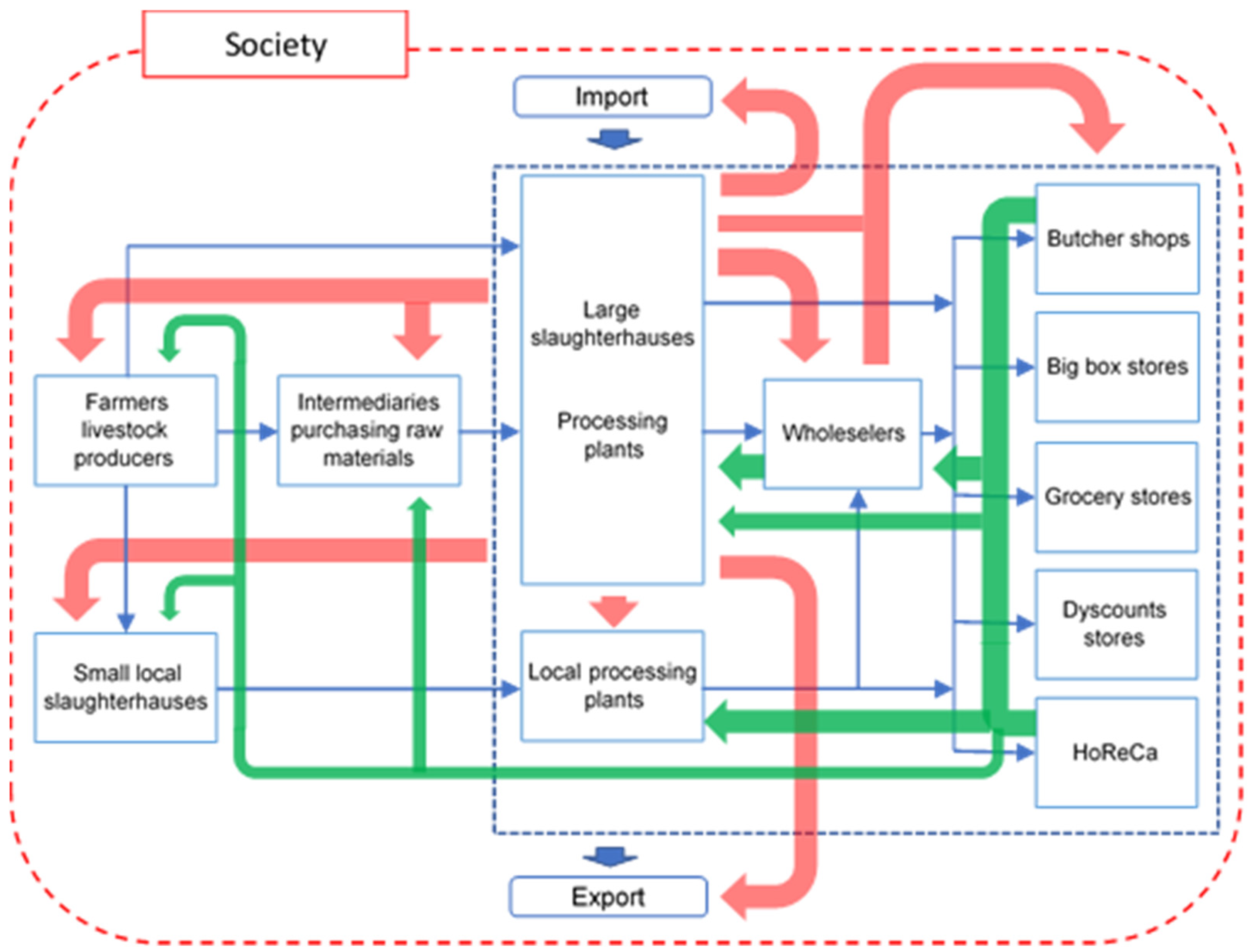

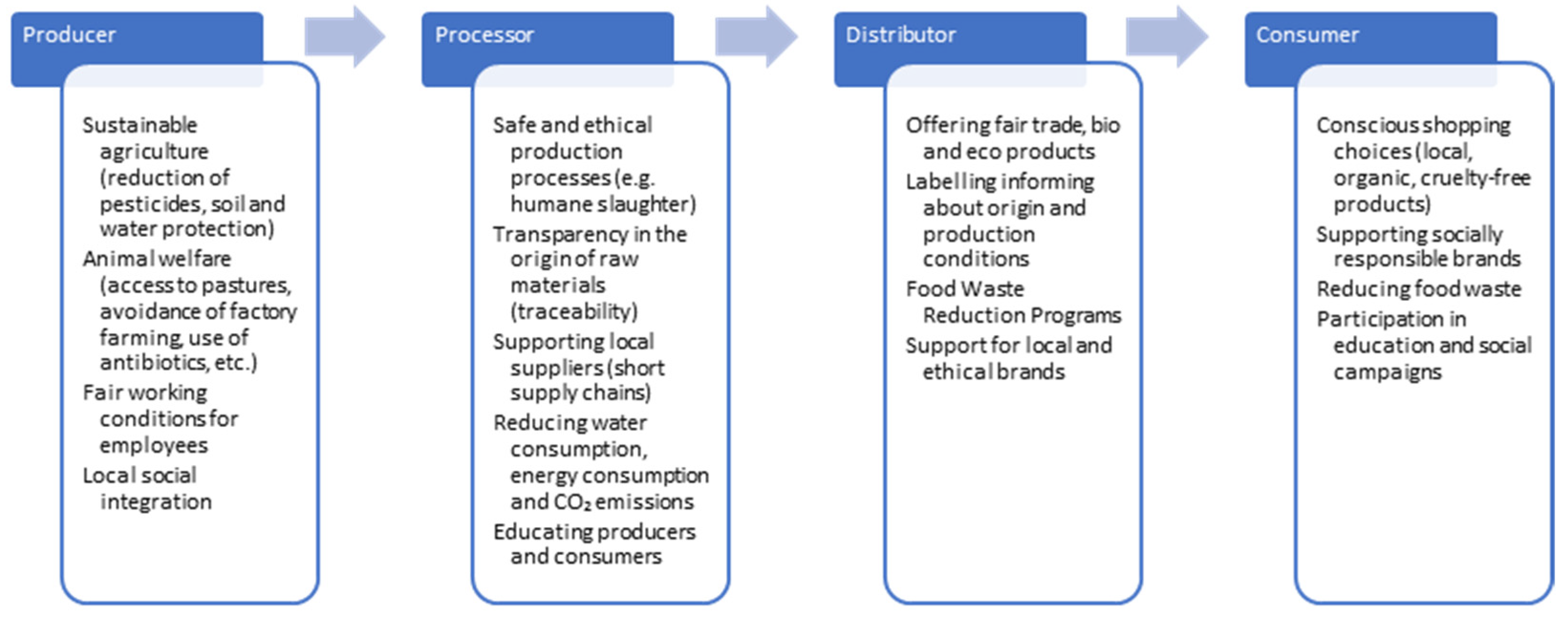

3.2. What Agribusiness Links and to What Extent Require Special Attention in Implementing Social Responsibility, Especially in the Context of Its Voluntary Nature?

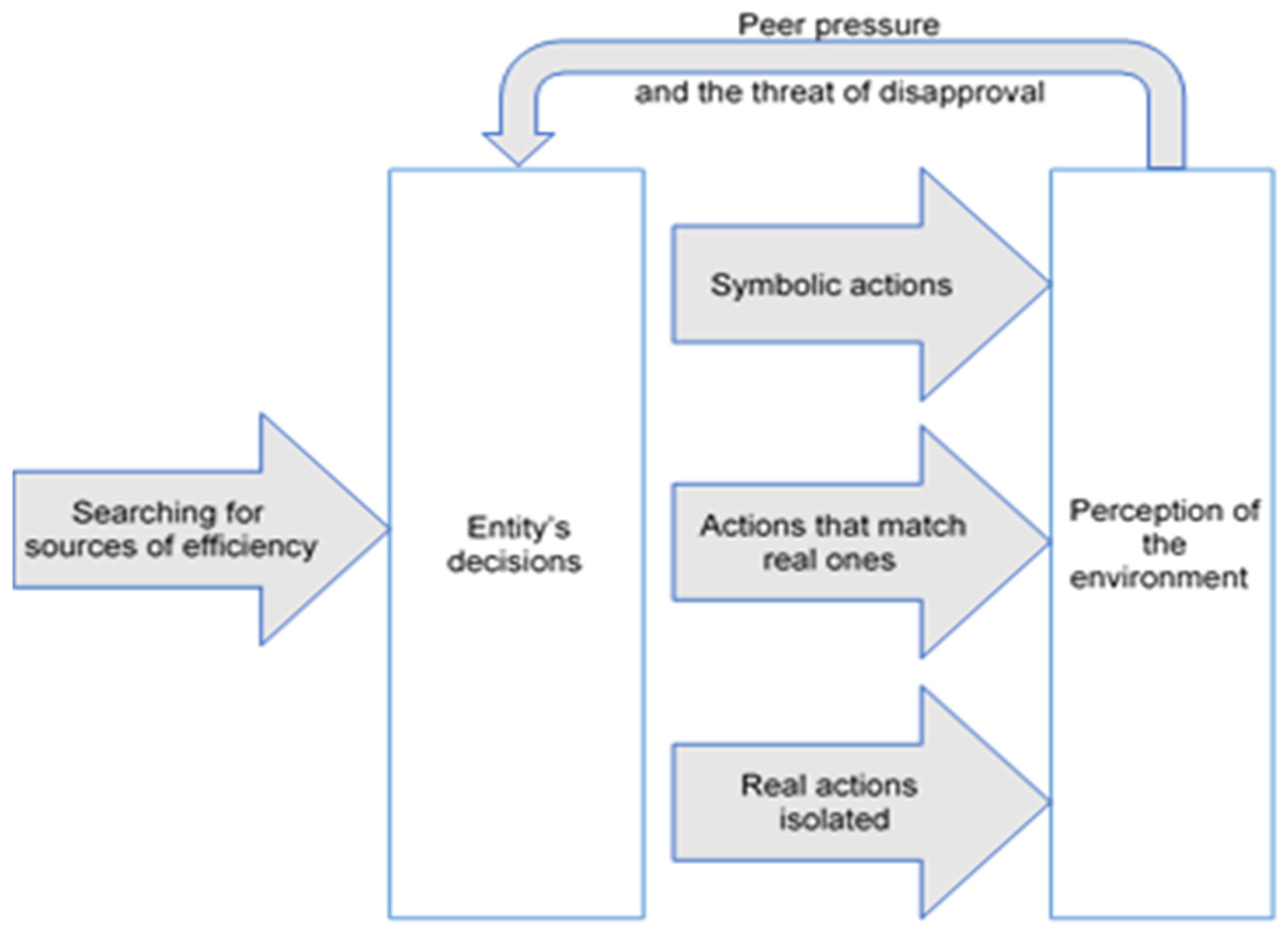

3.3. Which Agribusiness Links Implement ASR Driven by Genuine Choice? Which Ones Do So Under Coercion or Pressure?

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASR | Agribusiness Social Responsibility |

| CAP | Common Agricultural Policy |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| EDG | European Green Deal |

| ESG | Environment, Social Responsibility, and Corporate Governance |

| GAEC | Good Agricultural and Environmental Conditions |

| GMO | Genetically Modified Organisms |

| SRB | Socially Responsible Business |

| WoS | Web of Science |

References

- Kozar, Ł.; Oleksiak, P. Organizacje Wobec Wyzwań Zrównoważonego Rozwoju—Wybrane Aspekty; Publishing House of the Łódź University: Łódź, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stawicka, E. Agrobiznes a społeczna odpowiedzialność. Sci. Yearb. Assoc. Agric. Agribus. Econ. 2011, 13, 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hediger, W. Framing Corporate Social Responsibility and Contribution to Sustainable Development. Work. Pap. Ser. 2007, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Walaszczyk, A.; Walczak, N. Społeczna odpowiedzialność i zrównoważony rozwój w zarządzaniu branżą rolną. Zarządzanie Przedsiębiorstwem 2014, 1, 450–459. [Google Scholar]

- Adamczyk, J. Dyfuzja koncepcji zrównoważonego rozwoju i społecznej odpowiedzialności przedsiębiorstw. Mark. Rynek 2017, 11, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bernatt, M. Społeczna Odpowiedzialność Biznesu. Wymiar Konstytucyjny i Międzynarodowy; Scientific Publishing House of the Faculty of Management of University of Warsaw: Warsaw, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Żychlewicz, M. Społeczna odpowiedzialność biznesu jako strategia prowadzenia działalności polskich przedsiębiorstw. Współczesne Probl. Ekon. 2015, 11, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, M.; Stawicka, E. Społeczna odpowiedzialność biznesu (CSR) jako narzędzie podnoszenia konkurencyjności sektora MSP. In Społeczna Odpowiedzialność Biznesu w Małych i Średnich Przedsiębiorstwach; Szylar, K., Tymorek, M., Eds.; Instytut Badań nad Demokracją i Przedsiębiorstwem Prywatnym: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Leśna-Wierszołowicz, E. Społeczna odpowiedzialność biznesu jako element budowania przewagi konkurencyjnej. Stud. Pap. Fac. Manag. Econ. Sci. 2016, 43, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Vives, A.; Peinado-Vara, E. Corporate Social Responsibility as a Tool for Competitiveness. In Proceedings of the Inter. American Conference on CSR Proceedings, Panama City, Panama, 26–28 October 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vilanova, M.; Lozano, J.M.; Arenas, D. Exploring the nature of the relationship between CSR and competitiveness. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Producing a Systematic Review. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; Buchanan, D.A., Bryman, A., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 671–689. [Google Scholar]

- Jęczmyk, A.; Uglis, J.; Kozera-Kowalska, M. Regenerative Agritourism: Embarking on an Evolutionary Path or Going Back to Basics? Agriculture 2024, 14, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, M.; Wołoszyn, J. Społeczna odpowiedzialność przedsiębiorstw (CSR) w sferze agrobiznesu. Probl. Rol. Swiat. 2011, 11, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, M. Koncepcja CSR w aspekcie polityki środowiskowej na przykładzie przedsiębiorstw agrobiznesu. Stud. Ekon. Reg. Łódzkiego 2014, 14, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Faizrakhmanov, D.; Zakirova, A.; Klychova, G.; Yusupova, A.; Klychova, A. Formation and disclosure of information on social responsibility of agribusiness enterprises. E3S Web Conf. 2007, 91, 06004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurovska, N.; Dema, D.; Vilenchuk, O.; Nedilska, L.; Vikarchuk, O. Corporate social responsibility of agribusiness as a determinant of ensuring rural development. Bus. Manag. 2025, 35, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawicka, E. Praktyka społecznej odpowiedzialności w przedsiębiorstwach agrobiznesu. Sci. Yearb. Assoc. Agric. Agribus. Econ. 2012, 14, 478–482. [Google Scholar]

- Kokoszka, K. Wymiary społecznej odpowiedzialności rolnictwa w świetle koncepcji zrównoważonego rozwoju rolnictwa i terenów wiejskich. In Handel Wewnętrzny, Special Edition: Trendy i Wyzwania Zrównoważonego Rozwoju w XXI Wieku; Pol. Wydaw. Gosp.: Warszawa, Poland, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 198–206. [Google Scholar]

- Zuzek, D.K. Społeczna odpowiedzialność biznesu a zrównoważony rozwój przedsiębiorstw. Sci. J. Małopolska Sch. Econ. Tarnów 2012, 21, 197–207. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova-Buiza, F.; Huaringa-Castillo, F.; Trillo-Corales, C. Corporate social responsibility actions in agribusiness: Towards sustainable community development. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Sciences and Humanities International Research Conference (SHIRCON), Lima, Peru, 17–19 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wieliczko, B. System ewaluacji unijnego wsparcia wobec wsi i rolnictwa a społeczna odpowiedzialność oraz zasady good governance. Sci. J. Wars. Univ. Life Sci. Ekon. I Organ. Gospod. Żywnościowej 2010, 83, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawicka, E. Koncepcja społecznej odpowiedzialności wobec rolnictwa. Sci. J. Wars. Univ. Life Sci. Ekon. I Organ. Gospod. Żywnościowej 2008, 68, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziemianowicz, R.I.; Przygodzka, R. Instrumenty wspierania przekształceń strukturalnych polskiego rolnictwa. In Fundusze Unijne a Rozwój Gospodarki Polskiej (Ze Szczególnym Uwzględnieniem Rolnictwa); Sikorski, J., Ed.; Publishing House of the Białystok University: Białystok, Poland, 2005; pp. 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Stawicka, E. CSR w kontekście zrównoważonego rozwoju sektora rolno-spożywczego. Tur. Rozw. Reg. 2017, 8, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyder, M.; Theuvsen, L. Determinants and effects of corporate social responsibility in German agribusiness: A PLS model. Agribusiness 2012, 28, 400–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poetz, K.; Haas, R.; Balzarova, M. CSR schemes in agribusiness: Opening the black box. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 47–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, H.; Theuvsen, L. Corporate social responsibility in agribusiness: Literature review and future research directions. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2016, 29, 673–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, H.; Theuvsen, L. Corporate social responsibility: Exploring a framework for the agribusiness sector. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2017, 30, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska-Hinc, M. Rzetelna analiza dorobku naukowca na podstawie…? In Proceedings of the Seminarium bibliotek PolBiT, Warsaw, Poland, 16–17 February 2012.

- Ortman, J.; Radomska, A.; Przyłuska, J.; Wiedzą, D.Z. Wskaźniki popularności publikacji naukowych. Forum Bibl. Med. 2013, 2, 212–222. [Google Scholar]

- Mazur-Wierzbicka, E. The application of corporate social responsibility in European agriculture. Misc. Geographica. Reg. Stud. Dev. 2015, 19, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijatović, M.; Uzelac, O.; Stoiljković, A. Agricultural sustainability and social responsibility. Ekon. Poljopr. 2022, 68, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewska-Paluszak, J.; Wieczorek, J.; Kozera-Kowalska, M. Społeczna odpowiedzialność przedsiębiorstw piwowarskich w Polsce w latach 2016–2019. Intercathedra 2020, 2, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapusta, F. Agrobiznes—Stan i możliwości rozwoju. Postępy Nauk Rol. 1996, 43, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Wicki, L.; Grontkowska, A. Zmiany znaczenia agrobiznesu w gospodarce i w jego wewnętrznej strukturze. Sci. Yearb. Agric. Rural Dev. Econ. 2015, 102, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepacki, B. Agribussines and agrilogistics: Definition and specifics. J. Mod. Sci. 2018, 39, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaszyk, P.; Kauf, S.; Szołtysek, J. Logistyka Jako Czynnik Dobrostanu; Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zadroga, A. Sustainable development jako paradygmat rozwoju społeczno-gospodarczego. In Przestrzenie Badawcze Młodych Naukowców, Inspiracje–Innowacje–Wdrożenia; Tabaszewski, R., Sawicki, K., Błachut, A., Eds.; Wydawnictwo KUL: Lublin, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Poczta-Wajda, A.; Sapa, A. Paradygmat rozwoju zrównoważonego—Ujęcie krytyczne. Prog. Econ. Sci. 2017, 4, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Gniadkowska-Szymańska, A. Zrównoważony rozwój, społeczna odpowiedzialność biznesu (CSR) i ESG w świetle uregulowań prawnych w Polsce i Unii Europejskiej. Kwart. Nauk o Przedsiębiorstwie 2025, 75, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H.R. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman; University of Iowa Press: Iowa City, IA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carnegie, A. The gospel of wealth. In Foundations of Business Thought; Boardman, C., Sandomir, A., Sondak, H., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Banaś, M. Transgresja i dyfuzja–czyli o tym dlaczego nauki społeczne i humanistyczne sięgają do terminologii nauk przyrodniczych. Kult.-Hist.-Glob. 2013, 14, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lachiewicz, S.; Zakrzewska-Bielawska, A. Sieć przedsiębiorstw jako skuteczna forma organizacyjna w warunkach kryzysu gospodarczego. Manag. Bus. Adm. Cent. Eur. 2012, 20, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, P. Dyfuzja standardów odpowiedzialności społecznej w sieciach przedsiębiorstw w Polsce. Sci. Pap. Wrocław Univ. Econ. 2011, 220, 357–366. [Google Scholar]

- Michalczyk, J. Rola procesów globalizacji i integracji europejskiej w kształtowaniu się łańcuchów dostaw żywności. Ekon. XXI Wieku 2017, 15, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Buczkowski, B.; Dorożyński, T.; Kuna-Marszałek, A.; Serwach, T.; Wieloch, J. Społeczna Odpowiedzialność Biznesu. Studia Przypadków Firm Międzynarodowych; Publishing House of the Łódź University: Łódź, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Szajner, P.; Szczepaniak, I. Ewolucja sektora rolno-spożywczego w warunkach transformacji gospodarczej, członkostwa w UE i globalizacji gospodarki światowej. Zagadnienia Ekon. Rolnej 2020, 365, 61–85. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Firlej, K.; Hamulczuk, M.; Kozłowski, W.; Kufel, J.; Piwowar, A.; Stańko, S. Struktury Rynku i Kierunki ich Zmian w Łańcuchu Marketingowym Żywności w Polsce i na Świecie; Hamulczuk, M., Ed.; Institute of Agricultural and Food Economics–the National Research Institute: Warszawa, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kozera-Kowalska, M. Czy w Łańcuchu Produkcji Trzody da Się Jeszcze Zarobić? Available online: https://www.trzoda.net/czy-w-lancuchu-produkcji-trzody-da-sie-jeszcze-zarobic/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Migdal, W.; Migdal, L. Od pola do stołu–wymagania konsumentów w stosunku do rolników. Żywność Nauka Technol. Jakość 2021, 129, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobola, A. Społecznie odpowiedzialni konsumenci—Ogniwo zrównoważonego łańcucha żywnościowego. Przedsiębiorczość I Zarządzanie 2016, 17, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kozera, M.E. Uwarunkowania transferu wiedzy w polskim rolnictwie. Scientific Yearb. Assoc. Agric. Agribus. Econ. 2013, 15, 170–174. [Google Scholar]

- Janc, K. Transfer wiedzy w rolnictwie a serwisy internetowe—Przykład eksploracji danych sieciowych. Sci. Yearb. Agric. Rural Dev. Econ. 2015, 102, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, K. Zjawisko zarządzania symbolicznego a otoczenie organizacji. Przegląd Organ. 2014, 1, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, K.; Vellema, S.R. Agribusiness and Society: Corporate Responses to Environmentalism, Market Opportunities and Public Regulation; Jansen, K., Vellema, S., Eds.; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Grochowska, R.; Staszczak, A. Możliwości implementacji założeń unijnej strategii „Od pola do stołu” w sektorze rolno-spożywczym. Przemysł Spożywczy 2021, 75, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołacz, M. Od pola do widelca. In Wieś Kujawsko-Pomorska; Minikowo Agricultural Consultancy Center: Minikowo, Poland, 2016; p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- Michalczyk, J. Zrównoważone łańcuchy dostaw żywności. Wybrane inicjatywy. Sci. Pap. Wrocław Univ. Econ. 2018, 523, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewski, P. Skracanie Łańcuchów Dostaw w Przemyśle Spożywczym—Wybrane Zagadnienia. Available online: https://mieso.com.pl/aktualnosci/skracanie-lancuchow-dostaw-w-przemysle-spozywczym-wybrane-zagadnienia/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Nguyen, T.L.T.; Hermansen, J.E.; Mogensen, L. Environmental costs of meat production: The case of typical EU pork production. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 28, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustyńska-Prejsnar, A.; Ormian, M.; Sokołowicz, Z.; Topczewska, J.; Lechowska, J. Oddziaływanie ferm trzody chlewnej i drobiu na środowisko. Proc. ECOpole 2018, 12, 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Ndue, K.; Pál, G. Life cycle assessment perspective for sectoral adaptation to climate change: Environmental impact assessment of pig production. Land 2022, 11, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. Value-enhancing capabilities of CSR: A brief review of contemporary literature. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedor, B. Implementacja koncepcji CSR jako przesłanka trwałości firmy i jej sukcesu rynkowego. Przegląd Organ. 2016, 1, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzybek, M.; Szopiński, W. Zarządzanie systemem CSR w przedsiębiorstwie branży mięsnej reakcją na nowe trendy w zachowaniach konsumentów. Handel Wewnętrzny 2015, 357, 252–262. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, C.J.; Widmar, N.J.O.; Wilcoxc, M.D.; Croney, C.C. Perceptions of Agriculture and Food Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| The article focuses on the concepts of corporate social responsibility and/or social responsibility in agribusiness in the title, abstract, and/or keywords, and “food supply chain” anywhere in the article. | The article does not contain the terms “corporate social responsibility” and/or “social responsibility in agribusiness” in the title, abstract, and/or keywords, or “food supply chain” anywhere in the article. | Inside/outside the scope of the study. |

| Peer-reviewed, full-text articles publisher in indexed journals. | Non-peer-reviewed research (opinion articles, editorials, book chapters, books) and other peer-reviewed works (e.g., theses, doctoral dissertations) that were not journal articles. Research notes and conference proceedings were excluded. | Expert reviews confirm the reliability of the research and ensure its credibility. |

| Publication language: English or Polish. | Article not written in English or Polish. | English has become the main language for disseminating scientific articles. |

| Only articles containing the words corporate social responsibility, social responsibility in agribusiness. | Articles not containing the words corporate social responsibility, social responsibility in agribusiness. | Scope refinement. |

| Only articles that connect social responsibility with agribusiness and the food supply chain. | Articles that do not contain social responsibility connections with agribusiness and the food supply chain. | Scope refinement. |

| Criterion | Voluntary | Coercion |

|---|---|---|

| The basis of action. | Own initiative, social pressure. | Law, regulations, contracts. |

| Examples of activities. | Fair Trade certifications, supporting local farmers. | Sanitary compliance, ESG reporting |

| Motivation. | Reputation, ethics, competitive advantage. | Avoiding sanctions, formal requirements. |

| Criterion | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) | Agribusiness Social Responsibility (ASR) |

|---|---|---|

| Scope of operation | All sectors of the economy. | Agribusiness. |

| Sustainability | One of the main goals. | Main goal. |

| Beneficiaries | Employees, customers, local community, suppliers, and investors. | Employees, customers, local community, suppliers, investors, farmers, consumers, producer organizations, and ecosystem. |

| Character | Improved reputation, customer loyalty, better access to capital, increased company value, increased competitiveness, and support for local development. | Improved reputation, customer loyalty, better access to capital, increased company value, increased competitiveness, support for local development, increased consumer trust, better relations with the local community, stable supply, and support for rural development. |

| Environmental benefits | One of many areas. | Main area. |

| Implementation costs | The company bears the cost. | The company bears the cost with the possibility of compensation. |

| Scale of activities | Local, regional, and global. | Local, regional, and finally, global. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kozera-Kowalska, M. Social Responsibility of Agribusiness: The Challenges of Diversity. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7236. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167236

Kozera-Kowalska M. Social Responsibility of Agribusiness: The Challenges of Diversity. Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7236. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167236

Chicago/Turabian StyleKozera-Kowalska, Magdalena. 2025. "Social Responsibility of Agribusiness: The Challenges of Diversity" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7236. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167236

APA StyleKozera-Kowalska, M. (2025). Social Responsibility of Agribusiness: The Challenges of Diversity. Sustainability, 17(16), 7236. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167236