Does Anticipated Pride for Goal Achievement or Anticipated Guilt for Goal Failure Influence Meat Reduction?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

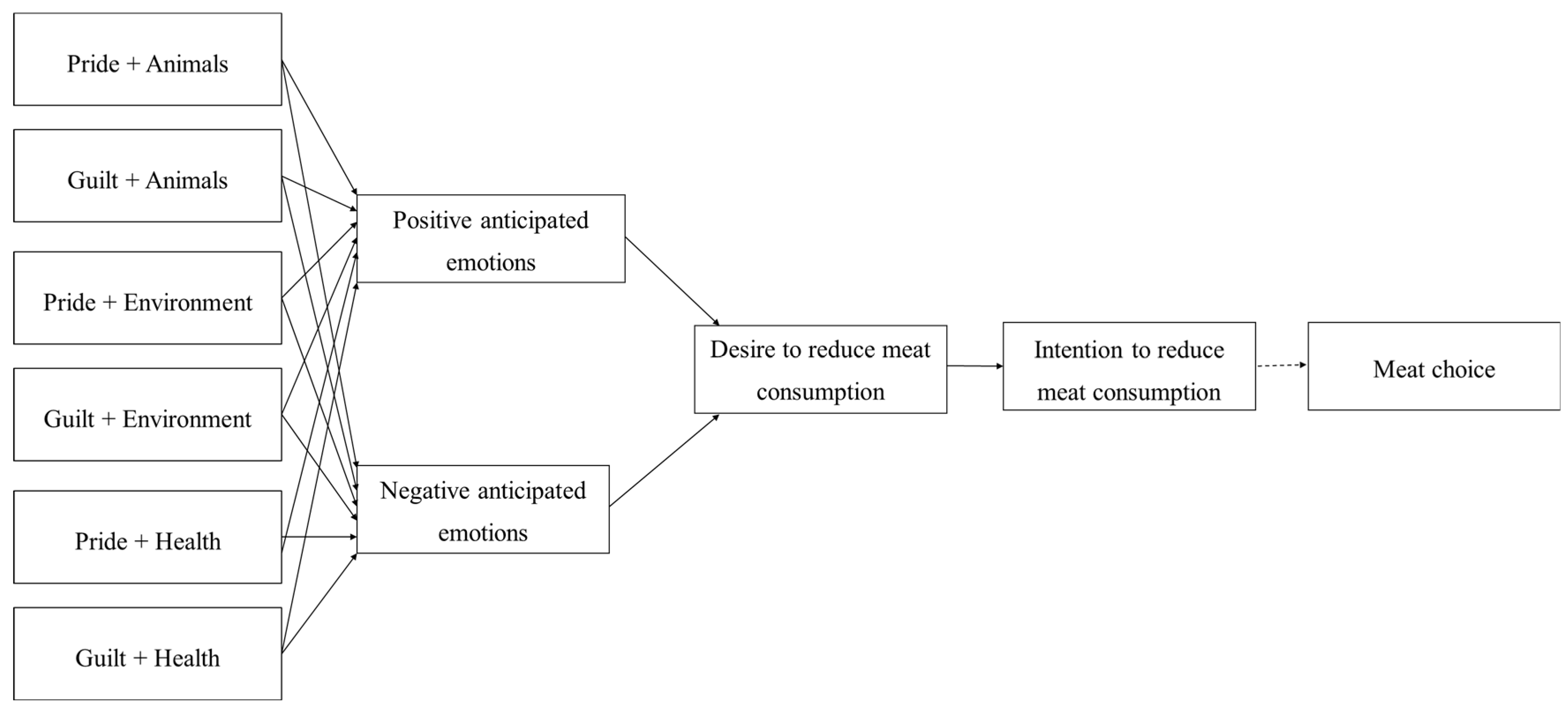

3. The Present Study

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Procedure

4.2. Participants

4.3. Pre-Test

4.4. Scenario Conditions

4.5. Post-Test

4.6. Data Analyses

5. Results

5.1. Preliminary Analyses

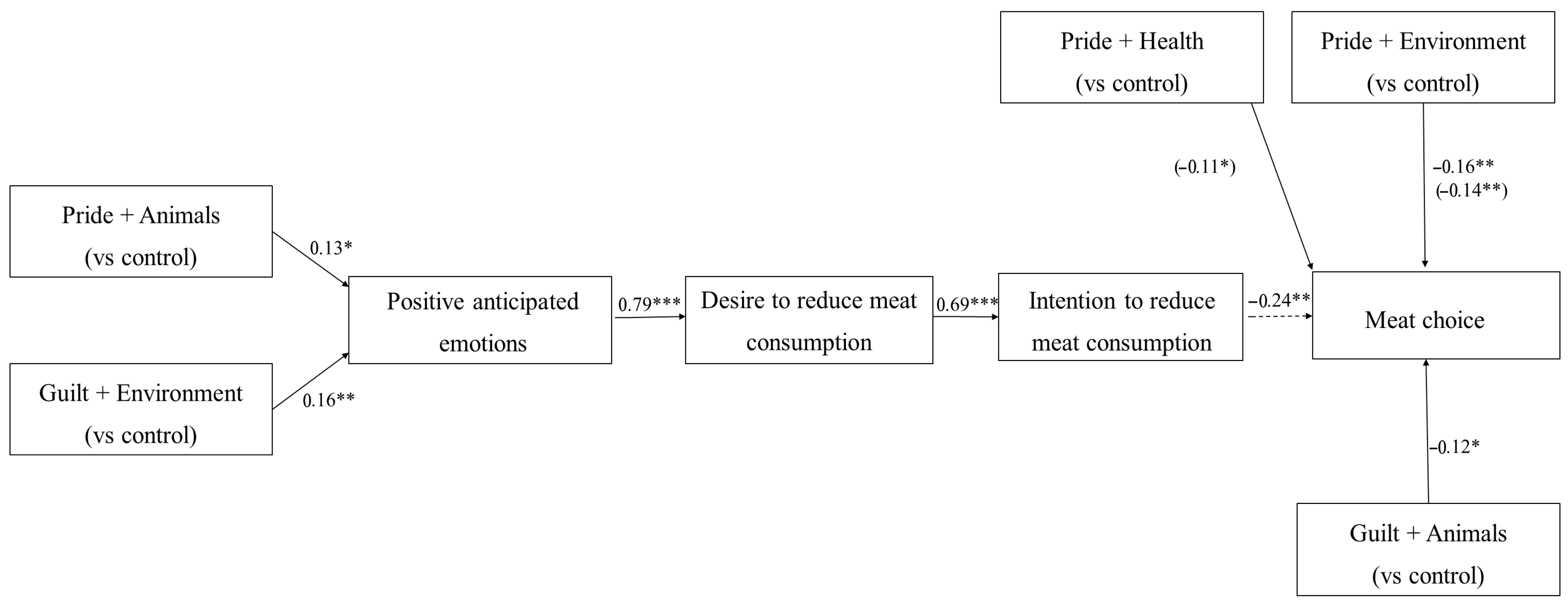

5.2. Main Analysis

| Type | Effect | b | SE | 95% CI Lower Limit | 95% CI Upper Limit | β | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | PH → APE | −0.22 | 0.31 | −0.92 | 0.36 | −0.05 | −0.71 | 0.478 |

| PH → Desire | 0.14 | 0.19 | −0.22 | 0.51 | 0.03 | 0.74 | 0.459 | |

| PH → Intention | 0.02 | 0.17 | −0.36 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.925 | |

| PE → APE | 0.15 | 0.28 | −0.41 | 0.68 | 0.03 | 0.55 | 0.580 | |

| PE → Desire | 0.02 | 0.18 | −0.33 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.922 | |

| PE → Intention | 0.03 | 0.17 | −0.29 | 0.38 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.847 | |

| PA → APE | 0.60 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 1.06 | 0.13 | 2.44 | 0.015 | |

| PA → Desire | −0.15 | 0.24 | −0.63 | 0.34 | −0.03 | −0.60 | 0.547 | |

| PA → Intention | 0.08 | 0.16 | −0.23 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.48 | 0.629 | |

| GH → APE | 0.29 | 0.26 | −0.20 | 0.81 | 0.06 | 1.15 | 0.250 | |

| GH → Desire | 0.01 | 0.18 | −0.32 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.952 | |

| GH → Intention | 0.13 | 0.18 | −0.24 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 0.71 | 0.475 | |

| GE → APE | 0.73 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 1.22 | 0.16 | 2.94 | 0.003 | |

| GE → Desire | −0.14 | 0.19 | −0.49 | 0.25 | −0.03 | −0.73 | 0.462 | |

| GE → Intention | −0.29 | 0.18 | −0.62 | 0.07 | −0.06 | −1.61 | 0.107 | |

| GA → APE | 0.49 | 0.30 | −0.12 | 1.10 | 0.11 | 1.62 | 0.106 | |

| GA → Desire | 0.03 | 0.20 | −0.38 | 0.43 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.888 | |

| GA → Intention | −0.15 | 0.17 | −0.43 | 0.24 | −0.03 | −0.87 | 0.382 | |

| APE → Desire | 0.90 | 0.03 | 0.85 | 0.96 | 0.79 | 32.34 | <0.001 | |

| APE → Intention | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 3.28 | 0.001 | |

| APE → Meat Choice | −0.12 | 0.07 | −0.25 | 0.00 | −0.12 | −1.82 | 0.069 | |

| Desire → Intention | 0.67 | 0.05 | 0.57 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 14.37 | <0.001 | |

| Desire → Meat Choice | −0.21 | 0.08 | −0.36 | −0.06 | −0.24 | −2.72 | 0.007 | |

| Intention → Meat Choice | −0.22 | 0.08 | −0.37 | −0.07 | −0.24 | −2.92 | 0.004 | |

| Indirect | PH → APE → Desire → Intention → Meat Choice | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.64 | 0.521 |

| PE → APE → Desire → Intention → Meat Choice | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.11 | 0.04 | 0.00 | −0.52 | 0.605 | |

| PA → APE → Desire → Intention→ Meat Choice | −0.08 | 0.05 | −0.21 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −1.69 | 0.091 | |

| GH → APE → Desire → Intention → Meat Choice | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.14 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −1.01 | 0.313 | |

| GE → APE → Desire → Intention → Meat Choice | −0.10 | 0.05 | −0.22 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −1.99 | 0.047 | |

| GA → APE → Desire → Intention → Meat Choice | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.19 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −1.36 | 0.173 | |

| Direct | PH → Meat Choice | −0.50 | 0.20 | −0.91 | −0.14 | −0.11 | −2.50 | 0.012 |

| PE → Meat Choice | −0.62 | 0.21 | −1.02 | −0.22 | −0.14 | −3.00 | 0.003 | |

| PA → Meat Choice | −0.26 | 0.25 | −0.73 | 0.27 | −0.06 | −1.06 | 0.291 | |

| GH → Meat Choice | −0.08 | 0.22 | −0.54 | 0.31 | −0.02 | −0.36 | 0.720 | |

| GE → Meat Choice | −0.28 | 0.26 | −0.78 | 0.21 | −0.06 | −1.10 | 0.273 | |

| GA → Meat Choice | −0.31 | 0.20 | −0.70 | 0.06 | −0.07 | −1.58 | 0.113 | |

| Total | PH → Meat Choice | −0.45 | 0.26 | −0.94 | 0.05 | −0.10 | −1.70 | 0.089 |

| PE → Meat Choice | −0.71 | 0.25 | −1.22 | −0.20 | −0.16 | −2.85 | 0.004 | |

| PA → Meat Choice | −0.52 | 0.29 | −1.05 | 0.06 | −0.11 | −1.80 | 0.073 | |

| GH → Meat Choice | −0.25 | 0.26 | −0.79 | 0.25 | −0.06 | −0.97 | 0.332 | |

| GE → Meat Choice | −0.52 | 0.29 | −1.09 | 0.04 | −0.11 | −1.77 | 0.077 | |

| GA → Meat Choice | −0.52 | 0.25 | −1.05 | −0.04 | −0.12 | −2.07 | 0.039 |

6. Discussion

6.1. Limitations and Future Directions

6.2. Study Implications

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonnet, C.; Bouamra-Mechemache, Z.; Réquillart, V.; Treich, N. Regulating meat consumption to improve health, the environment and animal welfare. Food Policy 2020, 97, 101847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Aveyard, P.; Garnett, T.; Hall, J.W.; Key, T.J.; Lorimer, J.; Pierrehumbert, R.T.; Scarborough, P.; Springmann, M.; Jebb, S.A. Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science 2018, 361, eaam5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosso, G.; La Vignera, S.; Condorelli, R.A.; Godos, J.; Marventano, S.; Tieri, M.; Ghelfi, F.; Titta, L.; Lafranconi, A.; Gambera, A.; et al. Total, red and processed meat consumption and human health: An umbrella review of observational studies. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 73, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abete, I.; Romaguera, D.; Vieira, A.R.; de Munain, A.L.; Norat, T. Association between total, processed, red and white meat consumption and all-cause, CVD and IHD mortality: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 762–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, D.D.; Weed, D.L.; Miller, P.E.; Mohamed, M.A. Red meat and colorectal cancer: A quantitative update on the state of the epidemiologic science. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2015, 34, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aune, D.; Ursin, G.; Veierød, M.B. Meat consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 2277–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi, G.; Mattiuzzi, C.; Cervellin, G. Meat consumption and cancer risk: A critical review of published meta-analyses. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2016, 97, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farchi, S.; De Sario, M.; Lapucci, E.; Davoli, M.; Michelozzi, P. Meat consumption reduction in Italian regions: Health co-benefits and decreases in GHG emissions. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Clark, M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature 2014, 515, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Torres, J.; Rodrigues, I. The impact of meat consumption on human health, the environment and animal welfare: Perceptions and knowledge of pre-service teachers. Societies 2023, 13, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwasny, T.; Dobernig, K.; Riefler, P. Towards reduced meat consumption: A systematic literature review of intervention effectiveness, 2001–2019. Appetite 2022, 168, 105739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, D.A.; Gee, Q.; Horn, A.; Weichert, L.; Blancho, M. How many chickens does it take to make an egg? Animal welfare and environmental benefits of replacing eggs with plant foods at the University of California, and beyond. Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 38, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyckhuys, K.A.; Aebi, A.; van Lexmond, M.F.B.; Bojaca, C.R.; Bonmatin, J.M.; Furlan, L.; Guerrero, J.A.; Mai, T.V.; Pham, H.V.; Sanchez-Bayo, F.; et al. Resolving the twin human and environmental health hazards of a plant-based diet. Environ. Int. 2020, 144, 106081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopwood, C.J.; Bleidorn, W.; Schwaba, T.; Chen, S. Health, environmental, and animal rights motives for vegetarian eating. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carfora, V.; Catellani, P.; Caso, D.; Conner, M. How to reduce red and processed meat consumption by daily text messages targeting environment or health benefits. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordts, A.; Nitzko, S.; Spiller, A. Consumer response to negative information on meat consumption in Germany. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, A.; Rotelli, V. Lowering red meat and processed meat consumption with environmental, animal welfare, and health arguments in Italy: An online experiment. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 877911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, M.B.; Peacock, J.; Reichling, D.B.; Nadler, J.; Bain, P.A.; Gardner, C.D.; Robinson, T.N. Interventions to reduce meat consumption by appealing to animal welfare: Meta-analysis and evidence-based recommendations. Appetite 2021, 164, 105277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottersen, I.S.; Benningstad, N.C.; Kunst, J.R. Daily reminders about the animal-welfare, environmental and health consequences of meat and their main and moderated effects on meat consumption. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2022, 5, 100068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio, A.; Irz, X.; Hartikainen, H. How effective are messages and their characteristics in changing behavioural intentions to substitute plant-based foods for red meat? The mediating role of prior beliefs. Appetite 2018, 125, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; King, J.M.; Prinyawiwatkul, W. A review of measurement and relationships between food, eating behavior and emotion. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 36, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiot, C.E.; Boutros, G.E.H.; Sukhanova, K.; Karelis, A.D. Testing a novel multicomponent intervention to reduce meat consumption in young men. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carfora, V.; Festa, S.; Pompili, S.; Azzena, I.; Scaglioni, G.; Lenzi, M.; Carraro, L.; Catellani, P.; Guidetti, M. The Effects of Disgust Messages on Plant-Based Food Choice: Exploring Underlying Processes and Boundary Conditions. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2025, 55, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel-Guy, C.; Bédard, A.; Corneau, L.; Bélanger-Gravel, A.; Desroches, S.; Bégin, C.; Provencher, V.; Lemieux, S. Impact of pleasure-oriented messages on food choices: Is it more effective than traditional health-oriented messages to promote healthy eating? Appetite 2019, 143, 104392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dang, W.; Hui, W.; Muqiang, Z.; Qi, W. Investigating the effects of intrinsic motivation and emotional appeals into the link between organic appeals advertisement and purchase intention toward organic milk. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 679611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bublitz, M.G.; Peracchio, L.A.; Block, L.G. Why did I eat that? Perspectives on food decision making and dietary restraint. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinyawiwatkul, W. Relationships between emotion, acceptance, food choice, and consumption: Some new perspectives. Foods 2020, 9, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Morandi, M.; Catellani, P. Predicting and promoting the consumption of plant-based meat. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 4800–4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Verain, M.C.; Dagevos, H. Positive emotions explain increased intention to consume five types of alternative proteins. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 96, 104446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandstra, E.H.; Ossel, L.; Neufingerl, N. Eating a plant-based burger makes me feel proud and cool: An online survey on food-evoked emotions of plant-based meat. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 113, 105046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Morandi, M.; Jelić, A.; Catellani, P. The psychosocial antecedents of the adherence to the Mediterranean diet. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 2742–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.E.; Santella, M.; Hermann, J.; Lawrence, J. Understanding college students’ intention to consume fruits and vegetables: An application of the Model of Goal Directed Behavior. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2018, 56, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, J.A.; Meng, F.; Zhang, P.; DiPietro, R.B. Examining factors influencing food tourist intentions to consume local cuisine. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 19, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas-Francois, K.; Jo, W.; Somogyi, S.; Li, Q.; Nixon, A. Virtual grocery shopping intention: An application of the model of goal-directed behaviour. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 3097–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Bertolotti, M.; Catellani, P. Informational and emotional daily messages to reduce red and processed meat consumption. Appetite 2019, 141, 104331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo-Vélez, G.; Tybur, J.M.; van Vugt, M. Unsustainable, unhealthy, or disgusting? Comparing different persuasive messages against meat consumption. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 58, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, K.F.; Sintov, N.D. Guilt consistently motivates pro-environmental outcomes while pride depends on context. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 80, 101776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.R.; Zaval, L.; Weber, E.U.; Markowitz, E.M. The influence of anticipated pride and guilt on pro-environmental decision making. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izard, C.E. Four systems for emotion activation: Cognitive and noncognitive processes. Psychol. Rev. 1993, 100, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J.S.; Li, Y.; Valdesolo, P.; Kassam, K.S. Emotion and decision making. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 799–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, G.; Lerner, J.S. The role of affect in decision making. In Handbook of Affective Science; Davidson, R., Scherer, K., Goldsmith, H., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 619–642. [Google Scholar]

- George, J.M.; Dane, E. Affect, emotion, and decision making. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2016, 136, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Guo, H. Advantages of anticipated emotions over anticipatory emotions and cognitions in health decisions: A meta-analysis. Health Commun. 2019, 34, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotabe, H.P.; Righetti, F.; Hofmann, W. How anticipated emotions guide self-control judgments. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Dholakia, U.M.; Basuroy, S. How effortful decisions get enacted: The motivating role of decision processes, desires, and anticipated emotions. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2003, 16, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviours: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Bartels, J.; Antonides, G. The self-regulatory function of anticipated pride and guilt in a sustainable and healthy consumption context. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 44, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, J.L.; Robins, R.W. Putting the self into self-conscious emotions: A theoretical model. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. Self-conscious emotions: Embarrassment, pride, shame, and guilt. In Handbook of Emotions; Lewis, M., Haviland, J.M., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 563–573. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, J.S.; Keltner, D. What is unique about self-conscious emotions? Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 126–129. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Vohs, K.D.; DeWall, C.N.; Zhang, L. How emotion shapes behavior: Feedback, anticipation, and reflection, rather than direct causation. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 11, 167–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G.; Bartels, J. The Norm Activation Model: An exploration of the functions of anticipated pride and guilt in environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 49, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Caso, D.; Palumbo, F.; Conner, M. Promoting water intake. The persuasiveness of a messaging intervention based on anticipated negative affective reactions and self-monitoring. Appetite 2018, 130, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Caso, D.; Conner, M. Randomised controlled trial of a text messaging intervention for reducing processed meat consumption: The mediating roles of anticipated regret and intention. Appetite 2017, 117, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, Z.; Jansson, J.; Bengtsson, M. Cause I’ll feel good! An investigation into the effects of anticipated emotions and personal moral norms on consumer pro-environmental behavior. J. Promot. Manag. 2017, 23, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolstenholme, E.; Carfora, V.; Catellani, P.; Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L. Explaining intention to reduce red and processed meat in the UK and Italy using the theory of planned behaviour, meat-eater identity, and the Transtheoretical model. Appetite 2021, 166, 105467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallucci, M. GAMLj: General Analyses for the Linear Model in Jamovi 2019. Available online: https://gamlj.github.io/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Gallucci, M. jAMM: Jamovi Advanced Mediation Models 2020. Available online: https://jamovi-amm.github.io/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Pieters, R. Goal-directed emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1998, 12, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeelenberg, M.; Pieters, R. A theory of regret regulation 1.0. J. Consum. Psychol. 2007, 17, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, J.L.; Robins, R.W. Emerging insights into the nature and function of pride. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 16, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.A.; DeSteno, D. Pride and perseverance: The motivational role of pride. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 94, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunda, Z. The case for motivated reasoning. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazar, N.; Amir, O.; Ariely, D. The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-concept maintenance. J. Mark. Res 2008, 45, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiddes, N. Social aspects of meat eating. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1994, 53, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, M.; Scatolon, A.; Carraro, L.; Guidetti, M.; Carfora, V. Community connectedness and sustainable eating. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2025, 65, 102047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolotti, M.; Valla, L.G.; Catellani, P. “If it weren’t for COVID-19…”: Counterfactual arguments influence support for climate change policies via cross-domain moral licensing or moral consistency effects. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1005813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Ma, W.; Tong, Z. How counterfactual thinking affects willingness to consume green restaurant products: Mediating role of regret and moderating role of COVID-19 risk perception. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 55, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagomarsino, M.; Lemarié, L. Hope for the environment: Influence of goal and temporal focus of emotions on behavior. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2024, 48, e13020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, M.; Sircova, A. Dispositional orientation to the present and future and its role in pro-environmental behavior and sustainability. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| “Imagine you set a goal to reduce your meat consumption in the last week. Please read the following scenario carefully”. | ||

| Anticipated Guilt + Health Scenario (GH scenario) | Anticipated Guilt + Environmental Scenario (GE scenario) | Anticipated Guilt + Animal Welfare Scenario (GA scenario) |

| In the last week, you have not been able to achieve your goal of reducing meat consumption. For this, you think: “If I continue to eat too much meat, I will feel guilty about endangering my heath”. | In the last week, you have not been able to achieve your goal of reducing meat consumption. For this, you think: “If I continue to eat too much meat, I will feel guilty about endangering the environment”. | In the last week, you have not been able to achieve your goal of reducing meat consumption. For this, you think: “If I continue to eat too much meat, I will feel guilty about endangering animal welfare”. |

| Anticipated Pride + Health Scenario (PH Scenario) | Anticipated Pride + Environment Scenario (PE Scenario) | Anticipated Pride + Animal Welfare Scenario (PA Scenario) |

| In the last week, you have been able to achieve your goal of reducing meat consumption. For this, you think: “If I continue to eat little meat I will feel proud for protecting my health”. | In the last week, you have been able to achieve your goal of reducing meat consumption. For this, you think: “If I continue to eat little meat I will feel proud for protecting the environment”. | In the last week, you have been able to achieve your goal of reducing meat consumption. For this, you think: “If I continue to eat little meat I will feel proud for protecting animal welfare”. |

| “Imagine you set a goal to reduce your sugar consumption in the last week. Please read the following scenario carefully”. | ||

| Control | ||

| [Guilt] In the last week, you have not been able to achieve your goal of reducing sugar consumption. For this, you think: “If I continue to eat foods with too much sugar, I will feel guilty”. | ||

| [Pride] In the last week, you have been able to achieve your goal of reducing sugar consumption. For this, you think: “If I continue to eat foods with little sugar, I will feel proud”. | ||

| M (SD) | Anticipated Pride | Anticipated Guilt | Positive Anticipated Emotions | Negative Anticipated Emotions | Desire (Meat Reduction) | Intention (Meat Reduction) | Meat Choice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticipated Pride | 4.39 (1.57) | |||||||

| Anticipated Guilt | 3.22 (1.65) | 0.66 *** | ||||||

| Positive Anticipated Emotions | 4.22 (1.54) | 0.88 *** | 0.64 *** | |||||

| Negative Anticipated Emotions | 2.85 (1.34) | 0.62 *** | 0.85 *** | 0.63 *** | ||||

| Desire (meat reduction) | 3.91 (1.75) | 0.77 *** | 0.66 *** | 0.79 *** | 0.64 *** | |||

| Intention (meat reduction) | 3.30 (1.68) | 0.69 *** | 0.63 *** | 0.69 *** | 0.62 *** | 0.81 *** | ||

| Meat Choice | 2.83 (1.51) | −0.46 *** | −0.38 *** | −0.48 *** | −0.39 *** | −0.54 *** | −0.52 *** | |

| Age | 29.06 (9.07) | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.08 | −0.11 * |

| Gender (1 = woman, 2 = man) | - | −0.18 *** | −0.22 *** | −0.19 *** | −0.22 *** | −0.17 *** | −0.26 *** | 0.27 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pompili, S.; Scaglioni, G.; Guidetti, M.; Festa, S.; Azzena, I.; Lenzi, M.; Carraro, L.; Conner, M.; Carfora, V. Does Anticipated Pride for Goal Achievement or Anticipated Guilt for Goal Failure Influence Meat Reduction? Sustainability 2025, 17, 7231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167231

Pompili S, Scaglioni G, Guidetti M, Festa S, Azzena I, Lenzi M, Carraro L, Conner M, Carfora V. Does Anticipated Pride for Goal Achievement or Anticipated Guilt for Goal Failure Influence Meat Reduction? Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167231

Chicago/Turabian StylePompili, Sara, Giulia Scaglioni, Margherita Guidetti, Simone Festa, Italo Azzena, Michela Lenzi, Luciana Carraro, Mark Conner, and Valentina Carfora. 2025. "Does Anticipated Pride for Goal Achievement or Anticipated Guilt for Goal Failure Influence Meat Reduction?" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167231

APA StylePompili, S., Scaglioni, G., Guidetti, M., Festa, S., Azzena, I., Lenzi, M., Carraro, L., Conner, M., & Carfora, V. (2025). Does Anticipated Pride for Goal Achievement or Anticipated Guilt for Goal Failure Influence Meat Reduction? Sustainability, 17(16), 7231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167231