Abstract

Nigerian poverty research is often fragmented and focuses on samples with minimal actionable strategies. This study aims to identify essential poverty alleviation and climate change strategies by synthesizing existing research, extracting the most critical poverty alleviation and climate change factors, and assessing strategies to combat poverty and climate change in Nigeria. We obtained, utilizing the centrality measures of social network analysis and the visualization tools of bibliometric analysis, the research hotspots extracted from 119 articles from the SCOPUS database for the period 1994–2023, compared outcomes with other countries, and analyzed their implications for eradicating poverty in Nigeria. We find that low agricultural productivity and food insecurity are some of the essential poverty-engendering factors in Nigeria, which are being intensified by climate change irregularities. Also, researchers demonstrate weak collaboration and synergy, as only 0.02% of researchers collaborated. Our findings highlight the need to direct poverty alleviation efforts to the key areas identified in this study and increase cooperation between poverty alleviation and climate researchers.

1. Introduction

For some centuries now, poverty has been a major socio-economic challenge plaguing many regions globally, especially sub-Saharan Africa [1,2]. In Nigeria, for example, over 40% of its population lives in extreme poverty, grappling with economic turmoil, high cost of living, and deteriorating well-being [3]. Indeed, there exists a complex interaction between socio-economic factors such as inadequate education, low productivity, terrorism, unemployment, and a scarcity of entrepreneurial opportunities that exacerbate this crisis [4]. For instance, lack of access to education has handicapped the economic opportunities of a significant part of the population, manifesting in uneducated Nigerians having a 42% poverty rate over their educated counterparts [5]. Furthermore, the drastic reduction in agricultural productivity exacerbates food shortages and inflation, leading to pockets of hunger and malnutrition across Nigeria [6]. This decline, affecting 53% of farmers, is influenced by various factors, including climate change, terrorism, and conflicts between farmers and herdsmen. Intriguingly, states with extensive agricultural activity still experience higher poverty levels, and wage earners are also precariously close to the poverty line, emphasizing the complex dynamics at play [5,7]. Despite numerous poverty alleviation interventions in Nigeria, evidence from existing research suggests that they have not adequately achieved their intended goals [8,9]. Moreover, although many studies investigate poverty and poverty alleviation, findings are fragmented, failing to galvanize the most critical poverty indicators and devise strategies to alleviate them countrywide [10].

Recent data confirm that Nigeria’s poverty crisis remains deep. According to the World Bank, an estimated 38.9% of Nigerians (about 87 million people) still live below the extreme poverty line [11]. Even more strikingly, the 2022 Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) found that 63% of Nigerians (approximately 133 million people) are deprived in at least one basic dimension [12]. These figures underscore that Nigeria has one of the world’s largest poor populations (second only to India) and that severe deprivation is concentrated in rural areas [11]. Nigeria’s commitment to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG 1 on no poverty, therefore faces significant headwinds. In this context, scholars warn that climate change will further reverse poverty-reduction gains [13]. Extreme weather events in recent years (notably catastrophic floods in 2022 and 2023) have demonstrated how climate shocks hit the poor hardest, disrupting crops and livelihoods [14]. Many rural farmers, who rely on rainfed agriculture, are already seeing falling yields and are forced to clear new land to compensate, often without improving food security [15]. This nexus of climate risk and poverty vulnerability highlights the urgency of integrating adaptation strategies, such as drought-tolerant crops and weather-index insurance, into Nigeria’s poverty alleviation agenda.

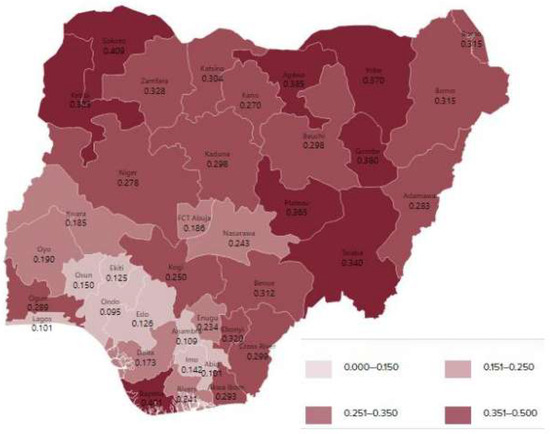

Despite the rich and growing body of poverty research, existing studies are often siloed by discipline and geography. Recent bibliometric work has begun to map global poverty research trends— for instance, Chipunza and Ntsalaze [16] use network analysis to identify clusters around income, health, and technology—but Nigeria-specific analyses are scarce. Our study fills this gap by applying social network analysis (SNA) to poverty and climate research in Nigeria. It has been successfully used to chart intellectual landscapes [17,18], revealing that knowledge networks often align with development outcomes. By identifying Nigeria’s most central poverty-related themes and comparing them to global trends, we can assess whether local research priorities match the country’s needs. In doing so, we build on recent calls for data-driven policy analysis [19] and for aligning research with the Sustainable Development Agenda [20]. This SNA approach thus promises to reveal hidden connections in the literature and guide future investments in the most impactful areas of poverty alleviation. The map (Figure 1) below shows the map of multidimensional poverty in Nigeria [21].

Figure 1.

Multidimensional poverty index by states in Nigeria. Source: Nigeria Poverty Map.

The multidimensional poverty index map shows the level of multidimensional poverty rate in Nigeria according to states. It describes the level of multidimensional poverty rates in the country, which is categorized into four different levels: A. 0.000–0.150, B. 0.151–0.250, C. 0.251–0.350, and D. 0.351–0.500. Table 1 below gives the full illustration of the multidimensional poverty index of Nigerian states.

Table 1.

Multidimensional poverty index table by states in Nigeria. Source: Nigeria Poverty Map.

From the multidimensional Nigeria poverty table, 133,000,000 out of 211,000,000 Nigerians are in what is described as “multidimensional poverty,” meaning that the national MPI is at 0.257, headcount is at 62.9%, and intensity is at 40.9%. This means that over half of the Nigerian population is multidimensionally poor and deprived of cooking fuel. It shows that there are high deprivations in sanitation, time to healthcare, food insecurity, and housing.

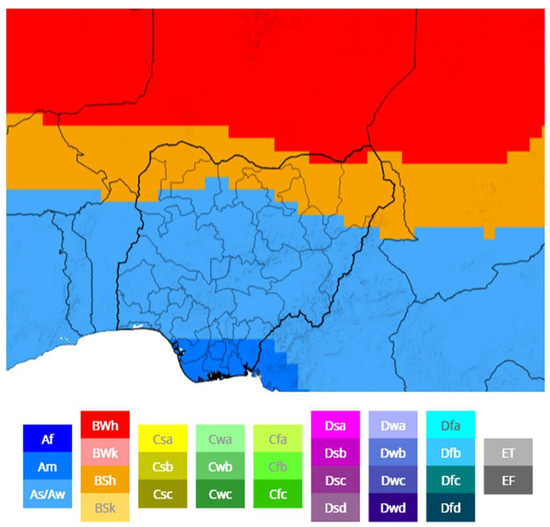

On climate change and how it affects impoverished masses, Adger et al. [22] emphasize that climate change disproportionately affects impoverished communities due to their limited adaptive capacity. They argue that poverty stifles access to resources, technology, and infrastructure, making it harder for these populations to cope with climate-induced disasters such as floods, droughts, and storms. Hallegatte et al. [23] outlines the economic dimensions of climate change impacts on poverty. They observe that climate-related shocks can adversely affect households, pushing them below the poverty line by destroying livelihoods, especially in agriculture-dependent communities. Their work also underscores the importance of establishing social safety systems that can mitigate these effects. Thomas & Twyman [24] explore the social vulnerability of impoverished communities to climate change. They argue that marginalized groups, such as women and ethnic minorities, are often the most affected due to systemic inequalities. Hence, they called for inclusive policies that address both poverty and climate adaptation. Watts et al.’s [25] work examines the health implications of climate change on low-income populations. They observe that rising temperatures and extreme weather events aggravate diseases such as malaria and diarrhea, which affect the poor. Their work stresses the importance of integrating health and climate policies into poverty alleviation programs. Barbier [26] investigates the environmental poverty trap, where climate change degrades natural resources that impoverished communities rely on for survival. He argues that this creates a vicious cycle, as reduction in natural resources further deepens poverty and limits opportunities for economic advancement. Stern [27], in his seminal review, examines the economic costs of climate change, particularly for developing nations. He outlines how poverty exacerbates climate impacts, as poor households lack the financial means to invest in adaptation measures. Stern also advocated global cooperation to address these challenges. Ribot [28] argues that poor governance and lack of representation in politics often exclude impoverished communities from decision-making processes related to climate adaptation. His research, therefore, calls for greater equity and representation in climate policy. Mendelsohn et al. [29] analyze the differential impacts of climate change across income groups. They observe that poor households are more likely to reside in high-risk areas, such as floodplains or arid regions, due to economic constraints. This spatial vulnerability further exacerbates their exposure to climate hazards. O ‘Brien & Leichenko [30] introduced the concept of “double exposure,” where impoverished communities face simultaneous pressures from globalization and climate change. They argue that these intersecting forces deepen inequalities and create new forms of vulnerability. Vandana [31] critiques the neoliberal economic policies that aggravated both poverty and environmental degradation. She argued that climate change is not just an environmental issue but a social justice issue, as it disproportionately affects those who contribute least to global emissions. The map (Figure 2) below shows the climate classification of Nigeria, 1991–2020, following the Köppen–Geiger climate classification.

Figure 2.

Köppen–Geiger climate classification in Nigeria (1991–2020). Source: World Bank Group.

The climate zone classifications are derived from the Köppen–Geiger climate classification system that classifies climate into five different categories: A (tropical), B (dry), C (temperate), D (continental), and E (polar). All climates except for those in the E group are assigned a seasonal precipitation subgroup.

Therefore, this study intends to infer from the wealth of poverty and climate change literature from Nigeria and other related authors to identify the most critical poverty alleviation themes and investigate how they can be harnessed to alleviate poverty in Nigeria. Through this endeavor, we aim to contribute meaningfully to the ongoing discourse on poverty alleviation, ultimately striving towards a more equitable and prosperous future for all Nigerians. For a comprehensive exploration of this study discourse, the research questions below provided a clear direction for this current study.

- What are the key research hotspots in Nigeria’s poverty alleviation literature?

- How does this research hotspot contribute to the understanding of poverty alleviation efforts in Nigeria?

- What is Nigeria’s role and contribution to the global discourse on poverty alleviation?

- What is the nature of collaboration between researchers in the field of poverty alleviation?

- How do poverty alleviation research hotspots of Nigeria compare to the research hotspots of more advanced nations?

- What is the connection between climate change and poverty, and how do these factors interact to exacerbate poverty in Nigeria?

To achieve these objectives, this research applies social network analysis (SNA) to the policy and research documents available on poverty and climate change to extract the most relevant poverty alleviation and climate change themes across the internet. SNA is a methodological approach that examines the relationships between factors quantitatively. It explains the structure, dynamics, and interactions within complex systems, making it a valuable tool across fields of study [32]. Bhattacharya et al. [33] used SNA to map the intellectual landscape of the Internet of Things, while Aizawa and Kageura [34] employed it to analyze associations between technical terms in academic papers. Similarly, Onyancha & Ocholla [35] utilized SNA to study HIV/AIDS infections, and Kostoff [36] applied it to identify research themes in software engineering. Compared to other content analysis methods, SNA offers distinct advantages by moving beyond mere word co-occurrences to unveil deeper insights into the interconnectedness of ideas within the literature.

By adopting SNA, this research aims to delve into the intricacies of the poverty alleviation and climate change literature in Nigeria, identifying key research hotspots and dissecting the historical and present challenges associated with these focal points. Additionally, we compare the poverty alleviation research hotspots in Nigeria to those of the countries that have successfully tackled poverty to confirm whether Nigeria’s current priorities require amendments and how this would impact the fight against climate change. This analysis in this research promises to enrich our understanding of poverty alleviation efforts, shedding light on the relevance and effectiveness of existing strategies. Ultimately, our findings will inform policymakers and stakeholders, guiding them to refine existing approaches, explore new avenues, and ultimately enhance the outcomes of poverty alleviation initiatives in Nigeria.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

To perform this analysis, the authors, explored the SCOPUS database to generate the relevant data, using the search term “Poverty Alleviation”, and generated a total of 10,070 articles. The search was aimed at collating existing English-medium “Poverty Alleviation” literature in the fields of Social Sciences, Economics, Business, Management and Accounting, Arts and Humanities, and Multidisciplinary for the periods 1994 to 2023. The author also extracted data on “Climate Change” from the Climate Change Service Portal on Nigeria between 1991 and 2023. Finally, after data filtering, only 119 poverty alleviation articles and data from the climate change portal (World Bank Group), using the Köppen–Geiger climate classification system and literature from Nigeria, were utilized for this study.

The 119 articles selected for this study were selected based on their relation to the study. This study utilized materials in peer-reviewed journals focused on poverty alleviation, climate change, economic policy, and sustainability in Nigeria. The titles and abstracts of the articles were screened. Only articles whose titles and abstracts were related to the research questions were selected. The full texts of these articles were studied and reviewed to verify if they were suitable for the study. The final selected articles employed different research methodologies and were majorly theoretical, empirical, and policy-oriented studies. This method of selection was necessary to ensure that the sample comprehensively covers various dimensions of poverty alleviation and climate change in Nigeria, including economic, social, and environmental perspectives. This more detailed methodological framework ensures that the selected articles are both relevant and of high quality, and the filtering process is transparent and replicable.

2.2. Analysis

The four SNA measures of degree, closeness, betweenness, and eigenvector centrality were employed for this study [37]. Degree centrality expresses the number of connections a node has with other nodes in the network; hence, a node with the highest degree of centrality is the most connected node in the network. The closeness centrality measures the distance between a node and the other nodes in the network. The closer a node is to the others, the more influence it exerts on the other nodes, which is expressed by a high close centrality value. The betweenness centrality espouses the ability of a node to lie in the shortest possible path to the other nodes in the network. When most movements in a network require traveling through a particular node, that node has the highest betweenness value. The eigenvector expresses how much a node is connected to the most influential nodes in a network. Hence, the higher the eigenvector value of a node, the more the node is connected to the other influential nodes in the network.

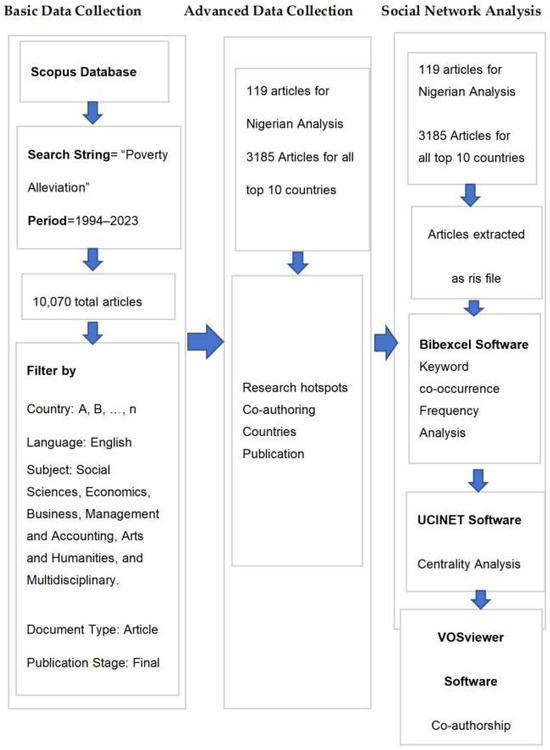

The specific analysis followed the following sequence: firstly, SCOPUS RIS data in Bibexcel was used to construct the frequency distribution, removing duplicates, selecting the top 20 relevant research hotspots, and creating a co-occurrence matrix. The generated matrix was treated in Excel before being exported to UCINET for the SNA centrality analysis. Afterward, the SCOPUS RIS data was imported to VOSviewer (Version 1.6.17) for the co-authorship analysis. The analysis covered countries such as Nigeria, China, and the top 10 countries that have poverty alleviation programs. Table 2 below presents the flowchart of the analysis framework.

Table 2.

Author’s computation using UCINET on the centrality measures for the research hotspots in the Nigerian poverty alleviation literature. (Note that the number after the $ sign connotes the frequency of the occurrence of a topic in the literature analyzed.)

3. Results

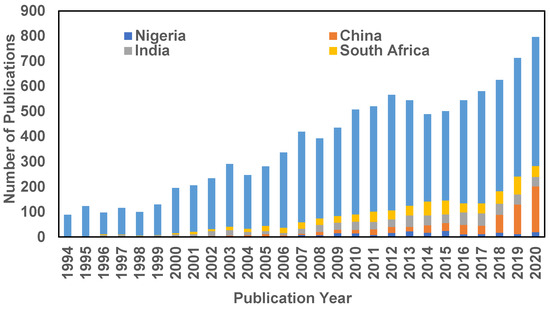

3.1. Nigeria’s Contribution to the Poverty Alleviation Discourse

Figure 3 shows the cumulative publications from the top 10 countries with the highest article output on poverty alleviation. Leading the pack is the United States of America (USA), followed by the United Kingdom (UK), China, South Africa, India, Australia, Canada, Germany, Netherlands, and Nigeria. Notice that the surge in poverty alleviation research observed since the 2000s coincides with the launch of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), highlighting its influence in raising global awareness of poverty and poverty alleviation efforts. Additionally, our analysis also finds that Nigeria, Congo-Kinshasa, India, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Madagascar, Uganda, Mozambique, Yemen, and Niger have the highest incidence of poverty globally. Intriguingly, although developing countries have a stronger need for poverty alleviation, we find that developed countries have and continue to have more significant contributions to the poverty alleviation literature.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the method. Source: Generated by the authors.

Particularly, the contribution of developing countries China (red), South Africa (yellow), India (ash) and Nigeria (royal blue) to poverty alleviation knowledge has been marginal, with China being a notable exception as shown in Figure 4. For instance, Nigeria’s contribution to poverty alleviation research remained low, accounting for less than two percent of the total research output over time. This lack of emphasis on research is further underscored by the country’s minimal investment in Research and Development (R&D) [38], amounting to less than 0.1 percent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In contrast, China significantly increased its research output, surging from less than 2 percent in 1994 to over 30 percent by 2020. This outcome could have been influenced by China’s proactive approach to addressing poverty through substantial R&D investments, allocating over two percent of its GDP to research initiatives [39].

Figure 4.

Aggregate publications by the 10 countries that published the most in the field of poverty alleviation. Source: Author’s computation using SCOPUS data. The light blue on the top represents 6 other advanced countries listed in the article.

This disparity emphasizes a fundamental structural difficulty: Nigeria’s research production falls short of the needs of its development agenda. Strengthening research capacity, through increased funding, postgraduate training, and incentives for poverty-relevant publications, would align Nigeria’s research agenda more closely with its social needs. For instance, international collaboration and South–South collaboration could be leveraged to build in-country capacity [2]. In addition, catalyzing government ministries to commission applied research on poverty drivers would bridge the policy–academic gap. Otherwise, Nigeria risks losing chances to leverage knowledge tools at a time when evidence-based action is critical to attain its poverty-reduction target.

3.2. Nature of Collaboration in the Field of Poverty Alleviation

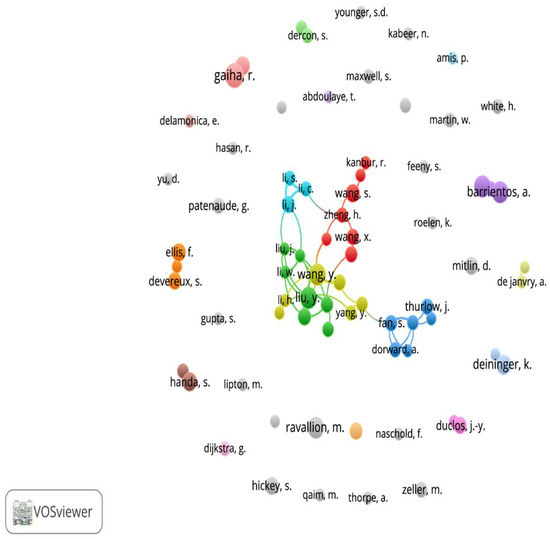

Despite the recognized advantages of co-authorship in enhancing research productivity, generating high-quality publications, and increasing citation rates compared to single authorship, co-authorship appears to be relatively limited in the context of poverty alleviation research, as illustrated in Figure 5 and Figure 6. For instance, among the 280 Nigerian authors examined, only 6 authors (representing 0.02% of the total) engaged in co-authorship, based on the VOSviewer’s threshold criteria of a minimum of three publications per author. Similarly, among the 5681 authors from the top 10 publication countries, only 74 individuals (amounting to 0.01%) participated in co-authorship, using the VOSviewer’s threshold for authors with a minimum of five publications [40].

Figure 5.

Co-authoring among Nigerian authors in the field of poverty alleviation. The authors in red are those from different institutions that co-authored with each other while the one in green co-authored with others in the same institution.

Figure 6.

Co-authoring among top 10 publication countries’ authors in the field of poverty alleviation. Source: Visualisation generated using VOSviewer.

Furthermore, Figure 6 reveals that a significant portion of co-authorship in poverty alleviation studies involves Asian researchers, with nine out of the top ten most co-authored researchers being of Asian origin. While causality cannot be conclusively determined, it is noteworthy that regions with higher levels of co-authorship witnessed notable progress in poverty alleviation over the past three decades. This observation suggests a potential correlation between collaborative research efforts and positive outcomes in poverty reduction.

Practically, Nigeria’s low co-authorship rate can hinder the spread of innovative techniques (e.g., randomized control trials or geospatial analysis) into the Nigerian poverty and climate change literature. Conversely, Asian co-authors characterize the limited number of co-publications that were found, implying foregone opportunities for Nigeria to benefit from regionally or thematically proximate expertise. To address this, programs that enable joint projects and researcher exchanges are necessary. For instance, collaborative projects among Nigerian and South African or Kenyan universities, nations with more extensive research networks, can facilitate the sharing of expertise. Additionally, the funding agencies could mandate the incorporation of multinational teams in grant applications on poverty and climate change; such mandates have already demonstrated the enhancement of research quality and policy implementation. In general, promoting a more integrated research community is likely to accelerate progress. Promoting Nigerian researchers to publish jointly, via co-authorship workshops and consortia grant schemes, therefore needs to be on the agenda for strengthening the knowledge base.

3.3. Capturing the Research Hotspots in Nigeria’s Poverty Alleviation and Climate Change Literature

The researchers began by examining the research hotspots in the Nigerian literature on poverty alleviation, as depicted in Figure 3, which illustrates the centrality measures for the top 20 hotspots. Through this analysis, it was revealed that 9 out of the 20 hotspots identified in the Nigerian literature overlap with those found in the most prominent global literature on poverty alleviation (refer to Figure 3). In contrast, China exhibits more substantial progress in poverty alleviation, with 12 out of the 20 hotspots aligning with the global literature (refer to Figure 4). Notably, Nigeria and China share 11 common research hotspots, as evident from a comparison between Figure 3 and Figure 4. However, there are notable disparities between the hotspots identified in the Nigerian and Chinese literature and those in the global literature. Specifically, areas such as Governance, Inequality, Gender, and Impact Evaluation are absent from both the Nigerian and Chinese literature despite their prominence in the global discourse. Moreover, we observed that not only do the research hotspots vary between countries but their respective orders of importance also differ based on centrality measures. Therefore, an intriguing avenue for future research lies in exploring whether these differences in identified hotspots across countries have implications for the effectiveness of poverty alleviation efforts. Table 2 discusses the centrality measures for the research hotspots in the Nigerian poverty alleviation literature.

The significance of the centrality measures outlined in Table 2 provide invaluable insights into the true relevance and impact of research hotspots within the literature. While certain topics may co-occur frequently, their centrality scores show a more nuanced understanding of their influence. For instance, despite climate change and rural economy appearing six and three times, respectively, the centrality measure elevates rural economy as having greater overall influence. Furthermore, the table highlights poverty alleviation as the most connected node in the network, boasting the highest degree of centrality and serving as the closest node to every other node. Additionally, its prominence is underscored by its significant travels in the network (betweenness) and robust connections with other relevant nodes (eigenvector centrality). By considering poverty alleviation’s extensive network connections and strong eigenvector centrality, the most pertinent research hotspots in the literature can be identified.

In our analysis, we focus on research hotspots with eigenvector values exceeding 0.160, indicative of their heightened relevance. These hotspots include Agriculture, Technology Adoption, Tourism, Household Income, Sustainable Development, Social Policy, Unemployment, Rural Economy, and Food Security. By prioritizing these areas of focus, we can delve deeper into the critical themes shaping poverty alleviation efforts, thereby informing more targeted and effective strategies for socio-economic development.

3.4. Climate Change Effects in Nigeria

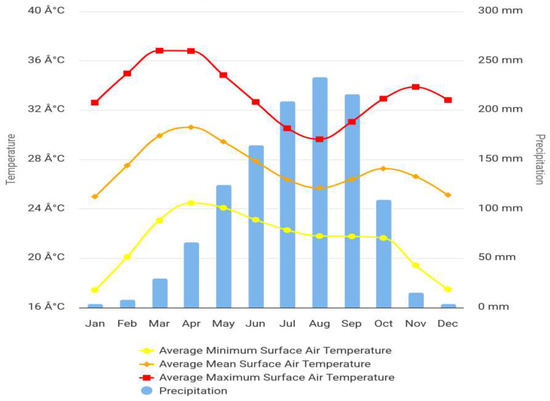

Climate change has remained one of the major challenges facing lives and livelihood across Nigeria [41]. The chart below (Figure 7) shows the monthly climatology of average minimum surface air temperature, average mean surface air temperature, average maximum surface air temperature, and precipitation in Nigeria between 1991 and 2023.

Figure 7.

Monthly climatology of air temperature and precipitation: 1991–2023. Source: Climate Change Knowledge Portal (World Bank Group).

Table 3 below shows a clearer explanation of the monthly climatology chart above, showing the monthly average minimum surface air temperature, average mean surface air temperature, average maximum surface air temperature, and precipitation.

Table 3.

Monthly climatology of average minimum surface air temperature, average mean surface air temperature, and average maximum surface air temperature. Source: Author’s computation from World Bank Group.

This climatology data highlights trends in surface air temperature and precipitation over three quarters (Q1, Q2, and Q3) from 1991 to 2023. Following the data, the average minimum surface air temperature of the first quarter from 1991 to 2023 is between 17.42 °C and 24.47 °C, the second quarter is between 24.09 °C and 21.8 °C, and the third quarter is between 21.77 °C and 17.48 °C. The average mean surface air temperature of the first quarter from 1991 to 2023 is between 24.99 °C and 30.61 °C, the second quarter is between 29.44 °C and 25.69 °C, and the third quarter is between 26.39 °C and 25.12 °C. The average maximum surface air temperature of the first quarter from 1991 to 2023 is between 32.61 °C and 36.79 °C, the second quarter is between 34.84 °C and 29.64 °C, and the third quarter is between 31.05 °C and 32.82 °C. The precipitation in the first quarter ranges between 3.67 mm and 66.27 mm; the second quarter is between 124.45 mm and 233.97 mm, while the third has precipitation between 216.43 mm and 3.88 mm.

These trends clearly show how climate change is exacerbating poverty in Nigeria, particularly in agriculture-dependent communities. In this analysis, we are focused on four major areas: rise in temperature, erratic temperature patterns, uneven rainfall distribution, and seasonal variability. On the rise in temperature, the average minimum, mean, and maximum surface air temperatures show significant variability across quarters, with maximum temperatures reaching up to 36.79 °C in Q1 and 34.84 °C in Q2. On the issue of erratic temperature, the temperature ranges vary significantly across quarters, with Q1 being the hottest and Q3 the coolest. On uneven rainfall distribution, precipitation ranges from 3.67 mm to 66.27 mm in Q1, 124.45 mm to 233.97 mm in Q2, and 216.43 mm to 3.88 mm in Q3. On seasonal variability, Q2 has the highest precipitation (up to 233.97 mm), while Q1 and Q3 have significantly lower rainfall. These patterns echo the increasing climate variability documented for Nigeria.

Recent analyses show Nigeria faces more frequent and intense floods, droughts, and heatwaves [42]. For example, Okafor et al. [42] note that extreme weather events, erratic rainfall, and drought have been intensifying in recent decades. Our climatology confirms these trends: temperature extremes in Q1 and surges of rainfall in Q2 can devastate crops and infrastructure. Such volatility likely exacerbates food insecurity and poverty in farming communities. In particular, the mismatch between the planting season and delayed rains (as seen in Q2) contributes to harvest failures. As Okafor et al. [42] point out, Nigeria’s economic reliance on climate-sensitive sectors and limited adaptive capacity leave the poor especially vulnerable. In sum, the climatology results reinforce the need for poverty strategies that explicitly account for climate risk (e.g., by promoting flood-resistant crops and early-warning systems) as part of Nigeria’s research and policy agenda.

4. Climate Change and Poverty in Nigeria: An Interlinked Crisis

4.1. Agricultural Vulnerability

According to Omokaro [43], the agricultural sector of Nigeria is highly vulnerable to climatic changes and uncertainties and a significant number of Nigerians depend on agriculture to sustain their welfare. A study carried out by the National Agricultural Sample Census (NASC) [44] reveals that 40.2 million Nigerians depend on agriculture for their livelihood. These citizens, through agricultural vulnerabilities, are greatly exposed to climate change events such as flooding, droughts, erosion, etc. [45]. Gradual climate changes as well as natural disasters greatly impact agricultural production and prices, which influences poor households, reducing their capacity to afford increases in food production and prices [23]. The World Bank reports that about 78% of Nigeria’s land mass is dedicated to agriculture and its geography is prone to extreme weather conditions. Additionally, Nigeria being a country that heavily depends on rain-sponsored agriculture is faced with climate challenges such as inconsistent rainfalls, desertification, and increasing temperatures [46,47]. Consequently, climate change does not only pose threat to poor households but also to a significant volume of the country’s land mass.

4.2. Migration

The impacts of climate change are also seen in the migration rate in flood-prone communities in Nigeria. According to Stromsta [48], 526,215 individuals were forcefully displaced from their previous homes in Anambra due to the 2022 floods. Additionally, 700,000 residents of Bayelsa had to migrate from their previous communities due to the floods in 2022 [48]. Jalo [49] asserts that several Fulani Herdsmen have had to migrate to another location in search for greener pastures due to desertification in the northern parts of Nigeria. Udoh et al. [50] argues that weather shocks contribute massively to household migration plans. Adebanjo [51], recounting the ripple effects of the migration of Fulani herdsmen, argued that newly built roads have become busier than usual as they regularly serve as “transhumance” routes for animals, thereby delaying vehicular movements, increasing the risks on these roads and instigating hostility and conflicts with host communities.

4.3. Poor Living Conditions and Health Vulnerabilities

Aigbokhan [52] affirms that poor families, especially in rural areas, highly depend on goods (consumption goods and productive inputs) generated freely from the environment to maintain their lifestyles. For instance, a study on the consumption of fuelwood in Nigeria discovered that an increase in household income and fuelwood price will cause a drastic fall in the demand for fuelwood. That is, the poorer the household, the lower the dependence on fuelwood consumption [52]. This heavy dependence on fuelwood is strongly connected to higher temperatures, which is likely to lead to regular heat-related diseases. Consequently, with limited access to quality healthcare, poor households are highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

4.4. Water Scarcity and Poor Infrastructure

Poor infrastructure exacerbates the adverse impact of climate change as it weakens the ability of Nigerians to adapt to the challenges associated with climate change. Trésor [45] asserts that desertification and increasing temperatures have intensified challenges such as water scarcity. Odoh and Chilaka [53] argue that desertification contributes significantly to water scarcity, which aggravates the strain on the natural resources in the country. About 50 to 75% of the land in the North has become desert due to the scarcity of water in the region [54]. These occurrences have affected agricultural production in this region. For example, there has been a fall in rice production as a result of inconsistent rainfalls [45].

Furthermore, events, such as flooding and rising sea levels, have revealed the poor state of infrastructure in river basins and coastal areas in the south. In 2022, the Nigerian Hydrological Services Agency (NIHSA) reported that intense floods were responsible for the deaths of 662 individuals and damaged over 440,000 hectares of farmland and displaced thousands of individuals in river basin areas in the south [45]. The Nigerian Meteorology Agency NIMET [55] reported that the flooding rate affected the production of staple crops such as yam, cassava, and maize, leading to significant losses in production in major agricultural states in Nigeria. Research also shows that rising sea levels and heavy rainfalls damage buildings, roads, bridges, and access to crucial services [43,55].

4.5. Public Health Challenges

According to Elisha [56], climate change intensifies the adverse impact of diseases, especially malaria, in Nigeria. It causes weather shocks that result in air-borne and water-borne illnesses [57]. World Bank [57] also reported that natural disasters have caused 27 bacterial diseases and 24 viral diseases, both of which resulted in 17,278 and 8233 deaths, respectively.

The impact of climate change and poverty cannot be underestimated in Nigeria, as they pose a lot of threats to the overall welfare of an average Nigerian. According to Elisha [56], food security and malnutrition are the biggest challenges in the north-eastern region of Nigeria. To worsen the situation, incessant conflict among migrants and host communities directly influences the rate of malnutrition in these regions, thereby intensifying the adverse effects of the poor public health infrastructures, as well as food insecurity in these regions [58].

5. Discussion

5.1. Agriculture

Nigeria’s agrarian identity depicts the significance of the agricultural sector in discussions of poverty alleviation, based on its vast arable lands and employment of 38 percent of the total labor force [59,60]. While agriculture is crucial for both employment and food production, its efficacy in reducing poverty is nuanced. Despite being the primary source of livelihood for many, particularly in rural areas, the sector’s impact on poverty is hindered by various challenges. These include low productivity resulting from inadequate investment, poor budgetary allocation, as well as reliance on subsistence and traditional farming methods [61,62]. High temperatures increase heat stress on crops, livestock, and humans, reducing agricultural productivity and labor efficiency. A 2021 FAO report found that climate change could reduce crop yields in Nigeria by 10–25% by 2050, worsening food insecurity and poverty. In Northern Nigeria, where temperatures often exceed 40 °C, heatwaves have led to crop failures and reduced income for farmers. Erratic temperature patterns alter planting and harvesting cycles, leading to crop failures and food shortages. In the Middle Belt region, unpredictable temperatures have reduced yields of staple crops like maize and rice, worsening food insecurity. Farmers and herders, who rely on predictable weather patterns, face income losses due to climate-induced disruptions. Low rainfall in Q1 and Q3 leads to droughts, while heavy rainfall in Q2 causes floods, both of which devastate agriculture and livelihoods. For example, the 2022 floods in Nigeria destroyed over 500,000 hectares of farmland, displacing 1.4 million people and worsening poverty in affected communities. On the other hand, water scarcity and reduced rainfall in Q1 and Q3 limits water availability for irrigation and domestic use, particularly in arid regions like the Sahel. Meanwhile, disrupting farming cycles has been one of the big challenges. Farmers depend on predictable rainfall patterns for planting and harvesting. Seasonal variability disrupts these cycles, leading to crop failures and income losses. In Southern Nigeria, delayed rainfall in the first quarter has forced farmers to plant late, reducing yields and increasing food prices. Increased vulnerability in poor households, who lack irrigation systems and other adaptive measures, are disproportionately affected by rainfall variability.

Consequently, the contribution of the sector to the GDP and export earnings has dwindled significantly over the years, indicating a disconnect between its potential and actual economic output [5]. Engel’s law illustrates this disparity, suggesting that, as incomes rise, the proportion spent on agricultural products decreases, potentially trapping the 38 percent of the labor force employed in agriculture in a cycle of limited economic prosperity [63]. To address this, there is a need for policies to promote mechanized farming to enhance productivity while simultaneously fostering alternative employment opportunities in other sectors. Also, promoting drought-resistant crops and investing in irrigation systems to reduce dependence on rainfed agriculture are very necessary.

Indeed, studies have shown that non-agricultural households often generate more income than agricultural ones, highlighting the potential benefits of diversification beyond the agricultural sector [64]. Therefore, adopting integrated strategies that transcend a sole focus on agriculture is essential for more effective poverty alleviation efforts in Nigeria.

5.2. Health Impact

Climate change has profound implications for public health, particularly in Nigeria, where rising temperatures and increased flooding exacerbate the spread of infectious diseases and heat-related illnesses. These health impacts adversely affect vulnerable populations, including the poor, children, and the elderly, further deepening poverty and inequality. Rising temperatures create favorable conditions for the proliferation of disease vectors, such as mosquitoes, which transmit malaria and dengue fever. In Nigeria, malaria remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, accounting for 30% of childhood deaths and 11% of maternal deaths, with poor rural communities bearing the brunt of the disease burden. Flooding, another consequence of climate change, further compounds these challenges by contaminating water sources and creating breeding grounds for waterborne diseases like cholera. For instance, the 2022 floods in Nigeria triggered a cholera outbreak, with over 100,000 cases and 3000 deaths reported, mostly in impoverished areas with limited access to clean water and healthcare. These health crises not only strain Nigeria’s already fragile healthcare system but also deepen poverty by reducing labor productivity and increasing healthcare costs for households.

The 2024 Lancet Countdown report for Nigeria documents these trends quantitatively. It reports a dramatic 141% increase in waterborne vibriosis cases in 2022, largely due to widespread flood [65]. By contrast, expanded healthcare access has reduced vulnerability to mosquito-borne diseases by about 25% over the past decade [65]. This suggests that, while some progress has been made, for example, better malaria prevention, new climate-induced burdens continue to climb. For instance, the catastrophic cholera outbreak in late 2022, linked to flooding, affected thousands in northern states.

Heat-related illnesses, such as heatstroke and dehydration, are also on the rise due to increasing temperatures. The Nigerian Meteorological Agency (NiMet) reports that average temperatures in Nigeria have increased by 1.5 °C over the past 50 years, with some regions experiencing even higher rises. Poor households, particularly in urban slums and rural areas, are especially vulnerable to extreme heat due to inadequate housing, lack of access to cooling systems, and limited healthcare services. Heatwaves affect vulnerable groups, including children, the elderly, and outdoor workers, leading to increased hospitalizations and deaths. For example, in Northern Nigeria, where temperatures often exceed 40 °C, heat-related illnesses have become a significant public health concern, further straining the region’s limited healthcare resources. The economic burden of these health impacts is immense, as households are forced to spend a significant portion of their income on healthcare, diverting resources from other essential needs like education and nutrition.

Addressing these health impacts requires a multi-faceted approach that integrates climate adaptation and public health strategies. First, it is expedient to strengthen Nigeria’s healthcare infrastructure to cope with the increasing burden of climate-related diseases. This may include expanding access to healthcare services in rural and underserved areas, improving disease surveillance systems, and ensuring the availability of essential medicines and vaccines. For example, increasing the distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets and antimalarial drugs can help reduce the incidence of malaria, while improving access to clean water and sanitation facilities can prevent cholera outbreaks. Second, public health campaigns should be amplified to raise awareness about the health risks associated with climate change and promote preventive measures. Community-based enlightenment interventions can empower individuals to protect themselves from heat-related illnesses by staying hydrated, avoiding outdoor activities during peak heat hours and recognizing the symptoms of heatstroke.

In addition to healthcare interventions, addressing the root causes of climate change is critical to mitigating its health impacts. This includes implementing policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, such as transitioning to renewable energy sources and promoting sustainable land use practices. Furthermore, adaptation measures, such as building climate-resilient infrastructure and improving urban planning, can help reduce the vulnerability of communities to extreme weather events. For instance, constructing flood defenses and drainage systems can prevent flooding and reduce the risk of waterborne diseases, while green spaces and tree-planting initiatives can mitigate the urban heat island effect and lower temperatures in cities. Finally, social safety nets, such as cash transfers and health insurance schemes, can help poor households cope with the economic burden of climate-related health impacts. By addressing both the immediate and underlying causes of climate-related health risks, Nigeria can build a more resilient and equitable healthcare system that protects its most vulnerable populations from the adverse effects of climate change.

5.3. Technological Adoption

Technological adoption becomes a crucial factor in this study, revolutionizing various aspects of daily life, including transportation, communication, healthcare, and food production. Mendola [66] underscores its significance in agriculture, highlighting how technological advancements have uplifted the livelihoods of farming households, directly contributing to poverty alleviation. In Nigeria, the impact of technological adoption on poverty reduction is evident, with communication tools such as cell phones enabling easier business transactions and market access for agricultural communities [67]. Moreover, the availability of electricity has facilitated the storage of perishable goods, mitigating losses for farmers and vendors. Easy transportation further enhances market access, enabling farmers to reach customers across the country and maximize profits. However, despite these advancements, the slow adoption of modern technology in food production processes limits its potential to boost productivity and alleviate poverty. The lack of exposure to mechanization among farmers hinders crop production efficiency, thereby impeding progress in poverty alleviation efforts [64]. Thus, accelerating the adoption of modern agricultural practices is imperative to unlock the full potential of technology in combating poverty in Nigeria.

This “digital divide” limits the potential for innovation. Rural households often lack electricity and connectivity, so apps for weather alerts or mobile banking may not reach the very poor. As a result, many farmers still rely on traditional, low-efficiency practices despite technological availability. To address this, targeted investments are needed. Expanding rural broadband and off-grid solar power can multiply the impact of digital tools. For example, pilot projects providing smartphones and training to cooperatives have increased farmers’ incomes in other African countries [68]. In parallel, local innovations, such as SMS-based market price services, should be scaled. By accelerating technology diffusion in agriculture and finance, Nigeria could tap a powerful avenue for lifting people out of poverty, consistent with global evidence on the productivity gains of ICT integration.

5.4. Tourism

Tourist sites in Nigeria located in rural areas where a significant portion of the population resides hold immense potential for socio-economic development. These sites can create employment opportunities for locals, foster infrastructural development, and enhance local businesses through increased tourist expenditure [69]. Cultural tourism, in particular, which involves visits to cultural festivals and historical landmarks, serves as a primary attraction in Nigeria. With its diverse ethnic groups, Nigeria boasts a multitude of cultural festivals and historical sites, including the annual Salah, Oba festival, Canoe Regatta, and Yam Festival, which draw tourists annually [69,70]. Despite the vast potential of the tourism sector, there is a consensus that the Nigerian government lacks a comprehensive plan to leverage its cultural heritage for tourism purposes. This absence of strategic planning results in inadequate infrastructure, poor maintenance of tourist sites, insufficient promotion, and inadequate protection for tourists [71]. Consequently, the tourism sector struggles to generate significant revenue, contributing only a minimal percentage to the GDP and ranking low globally in terms of economic contribution. Addressing these shortcomings and implementing a coherent strategy to develop the tourism sector could unleash its full potential to alleviate poverty and drive economic growth in Nigeria [72].

Significantly, post-pandemic rehabilitation presents a window of opportunity. It is essential to note that domestic tourism in West Africa is recovering, and Nigeria’s vast cultural heritage, from the Kano dye pits to Obudu Mountain Resort, can be more actively promoted. With better infrastructure (roads and accommodations) and stability provided by the government, tourism may generate non-farm income for rural communities. For example, community-level programs for the creation of local artisans and guides have effectively diversified incomes in parts of Africa. Nigeria could also pursue the same models, incorporating them within the poverty agenda. Generally, although it is currently a relatively small contributor to GDP, the tourism potential for employment creation is still vast and unexploited. To take advantage of this would require extensive planning that prioritizes security and sustainability, mobilizing cultural heritage into enterprises for the people.

5.5. Household Income

A pertinent factor to consider in this study is household income. Household income is crucial in determining poverty in a household. A household’s income is determined by the total income generated by income earners while taking into account the number of dependents in a household. Hence, a high-income earner in a relatively large dependent household could be a “working poor” earner [73]. With the minimum wage in Nigeria being under USD 100 a month and only about 30 million of the 230 million people fully employed in Nigeria, the resultant high age dependency ratio of 0.97 is unsurprising [3,60]. This means that, on average, an income earner in Nigeria has someone to depend on for help in the form of remittances.

Contrastingly, the age dependency ratio of China (0.40) and the USA (0.52), where two individuals support a citizen, shows the much-needed effort to lift a Nigerian household out of poverty. Out of the four sources of income in a Nigerian household (agriculture, small-scale business, blue- and white-collar jobs, and other non-labor income sources), about 80 percent of Nigerian households have at least two income sources for survival, such as agriculture and small-scale business [3,60]. Though agriculture and small-scale business are the predominant sources of income, especially in the rural areas of Nigeria, they are significantly less valuable, secure, and stable relative to salary-earning jobs [74]. Unfortunately, salary earners are not better off either, as a 2022 World Bank report [75] found that most Nigerians are engaged in income-earning activities that are not sufficient to lift them and their households out of poverty. Hence, more attention is given to non-agricultural activities in the contemporary literature due to their potency in boosting household income [76]. For instance, Odozi et al. [74] reported that, due to the enormous risks associated with farming in Nigeria, rural households in Nigeria benefit more from non-agricultural activities than previously acknowledged.

Remittances have been a lifeline for millions of Nigerians over the last several years. A World Bank brief shows that Nigeria received, by far, the largest share of West Africa’s remittances in 2023, with approximately 38% of the region’s inflows [77]. Although growing modestly, at around 2% in 2023 [77], these funds allow numerous households to cover food and school costs. However, volatile exchange rates and inflation have eroded the real value of remittances and, coupled with exorbitant transfer fees (sometimes exceeding 10%), revenues are further reduced. Economic crises, for example, the 2020 oil price collapse and the COVID-19 downturn, have also led to higher joblessness, especially among young people. Analysts caution that even multi-income households with no productive employment are not immune to the risks [78]. Policymakers should therefore not only promote remittance channels (e.g., through lower fees and diaspora bonds) but also generate high-quality jobs. Public investment in manufacturing and renewable energy could raise household incomes more sustainably than subsistence jobs. Enhancing social protection (e.g., unemployment insurance and decent minimum wages) would also ensure that the unemployed are not left behind.

5.6. Sustainable Development

Poverty alleviation serves as a fundamental strategy to enhance the sustainability and quality of life for both present and future generations [79]. In Nigeria, achieving sustainable development is paramount in addressing various entrenched challenges such as socio-political crises, poverty, security issues, and environmental degradation [80]. The existing literature emphasizes the importance of sustainable development in tackling these multifaceted challenges. However, Nigeria grapples with a plethora of obstacles on its path toward sustainable development, including poverty, unemployment, illiteracy, uncontrolled urbanization, poor public health, unsustainable industrialization, and environmental degradation, all of which imperil the well-being of future generations [80]. A poignant example is observed in the Niger Delta region, where, despite being the primary source of Nigeria’s oil revenue, local communities endure widespread poverty and environmental devastation due to oil spillage and pollution [81]. Various national and regional policies and initiatives, such as the Green Revolution, Operation Feed the Nation, and the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC), were established to boost sustainable development and mitigate poverty [82]. Nevertheless, these efforts have been hampered by pervasive issues like corruption, poor policy implementation, inconsistency, inadequate infrastructure, civil unrest, and a lack of political will [80,82]. In essence, the pursuit of sustainable development in Nigeria and its potential to alleviate poverty remain a distant aspiration plagued by systemic challenges.

5.7. Social Policy

Countries such as China, the USA, and the Netherlands have successfully rescued millions of citizens from poverty through the implementation of strategic and actionable policies [83]. Social policies, particularly during times of crisis, are recognized as crucial tools for managing national challenges and enhancing the well-being of disadvantaged segments of society. Since 1960, Nigeria has introduced various social policies to alleviate poverty. Notable among these policies are initiatives like the Petroleum Trust Fund (PTF) in the 1970s, focusing on the rehabilitation of critical infrastructure such as roads, water, healthcare, education, and agriculture. The War Against Indiscipline (WAI) in the 1980s sought to instill civility, while the Community Action Program for Poverty Alleviation (CAPPA) in the 1990s aimed to enhance living conditions, food production, skills development, healthcare, and food security for the impoverished [82]. Similarly, the National Poverty Eradication Program (NAPEP) in the early 2000s targeted poverty eradication across all sectors of the Nigerian economy, while the Nigerian Vision 20:2020 aspired for Nigeria to become one of the top 20 economies by 2020.

More recently, the National Social Investment Program, which was launched in 2015, aimed to ensure the equitable distribution of resources to vulnerable populations. However, despite these efforts, these policies have faced widespread criticism and negative reviews for their failure to address poverty and enhance citizens’ quality of life effectively. Corruption, socio-political instability, policy inconsistency, and fiscal mismanagement have been identified as key factors contributing to the shortcomings of these initiatives [84,85]. Additionally, a significant limitation of these policies has been their inadequate focus on the agricultural sector and rural areas despite Nigeria’s predominantly agricultural economy. To meaningfully improve living standards, policies must address all sectors of the economy and prioritize sustainable development [86].

5.8. Unemployment

Job creation is a pivotal issue to consider when addressing poverty and hunger within a country, as employment contributes significantly to human capital development [8]. Azih & Inanga [87], emphasize that sustainable development hinges on a substantial proportion of the population being gainfully employed, as unemployment remains a primary driver of household-level poverty, leading to economic hardship, strained relationships, and housing crises [83,88]. In Nigeria, endemic unemployment persists, with 33.3% of the labor force classified as unemployed and 22.8% underemployed as of 2020 [5]. Youth unemployment is particularly staggering, with a significant portion of Nigerian youths unable to secure employment or sustain their livelihoods through Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), exacerbating poverty rates and contributing to social unrest [88,89].

Recognizing unemployment as a pressing challenge, successive Nigerian administrations have implemented various programs and policies, including the establishment of the National Directorate of Employment (NDE) in 1986, initially when the unemployment rate stood at 8.5% [90,91]. Nevertheless, despite these efforts, government initiatives have largely failed to effectively address unemployment or alleviate poverty, as observed by Ada & Chigozie [92], amidst persistently high unemployment rates. Page and Shimeles [93] highlight the importance of directing employment efforts towards productive sectors of the economy to ensure poverty alleviation and foster economic prosperity, emphasizing the need for a targeted approach to job creation initiatives.

Addressing unemployment requires a multi-pronged strategy. First, economic diversification is needed; relying too heavily on oil renders job creation fickle. Investment in labor-intensive sectors like agro-processing, textiles, and renewable energy has the potential to absorb large numbers of workers. Second, linking education with market demands can reduce the skills mismatch. Vocational training programs focused on high-growth industries (e.g., ICT and green construction) are showing success in other African settings [94]. Third, entrepreneurship support—through credit access and mentorship—can turn young Nigerians into job creators rather than dependents. Studies indicate that places with robust SME support see higher youth employment [95]. In sum, targeted measures in education, business climate, and sectoral investment are needed to convert Nigeria’s demographic dividend into broad-based prosperity rather than increased poverty.

5.9. Rural Economy

The accelerated pace of urbanization and industrialization, as well as environmental degradation such as deforestation and pollution, underline the critical role of rural areas in sustaining national economies. Globally, approximately 70 percent of the world’s total food production originates from rural areas [96]. Therefore, neglecting the poverty situation in rural regions stifles the overall economic sustainability of a country. In Nigeria, rural communities are predominantly inhabited by impoverished low-income earners who rely on subsistence farming as their primary livelihood [97]. These farming operations often involve cultivating small plots of land using traditional methods that rely on animals and rainwater for irrigation [64]. Nevertheless, despite their agricultural contributions, rural populations continue to grapple with pervasive poverty. Studies have attributed this persistent poverty to factors such as low productivity, soil degradation, insufficient financial resources, and inadequate infrastructure [74].

Despite comprising a significant portion of society and producing most of the agricultural output, rural inhabitants face daunting challenges. With a high dependency ratio, a staggering 34 percent unemployment rate, and a 27 percent underemployment rate, the prospects for escaping poverty remain bleak for many rural dwellers [5]. To effectively address rural poverty, strategies must focus on diversifying income sources beyond traditional farming activities. Encouraging the development of non-farming sectors such as rural industries, trade, and transportation presents viable opportunities for creating sustainable livelihoods and uplifting rural well-being [98,99].

5.10. Food Security

Food security has been and still stands as a crucial determinant of poverty alleviation, representing the ability of households to access safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and sustain a healthy lifestyle [100]. This connection between food security and poverty is widely acknowledged in the scholarly literature, reflecting a symbiotic relationship between lack of food security and poverty [101,102,103]. Budiawati et al. [104] underscore this correlation, emphasizing that poverty and food insecurity are closely related, with poverty frequently leading to food insecurity and vice versa. While this relationship does not imply causation, it underscores the interconnectedness of factors influencing both poverty and food security.

In Nigeria, addressing food security and poverty has been a major focus of several governmental interventions, with initiatives such as the River Basin Development Authority and Operation Feed the Nation implemented since the 1970s [62,105]. Despite rapid progress, challenges persist, exemplified by instances of high food scarcity and inflation, particularly prevalent in the North Central states [106]. Obayelu’s research reveals stark disparities in food access, with only 36% of sampled households enjoying food security, while the remaining 64% experience varying degrees of food scarcity, including severe hunger. Factors such as household size, occupation, education level, dependency ratio, and landholding size influence household food security [106]. However, persistent food insecurity persists due to deficits in local food production, leading to price hikes, increased import dependency, exacerbating poverty, and hindering the ability of the poor to access sufficient food [106,107]. Addressing these systemic challenges is imperative to achieve sustainable food security and alleviate poverty in Nigeria.

Recent shocks underscore the vulnerability of Nigeria’s food systems. Aside from domestic production problems, climatic occurrences have been pivotal. For example, the desert locust incursion of 2020, which was fueled by atypical rainfall, threatened farmers in the north, while the 2022 floods devastated crops across a number of states. In line with Thomas et al. [108], North Central’s chronic food inflation is driven by dependence on imports and weak local production. Therefore, addressing food security requires that we boost local production in addition to stabilizing markets. Policies such as subsidized inputs, open grain reserves, and price support during times of shortage can be effective. Furthermore, linking smallholder farmers to markets via cooperatives or mobile phone platforms can reduce the power of exploitative intermediaries and ensure that increased production translates into lower prices for poor populations. Simultaneously, nutrition programs, such as school meals programs and micronutrient delivery initiatives, may be used as a safeguarding measure for the poor against food emergencies, hence supplementing the above structural measures. In sum, a proper food security program, which merges climate adaptation with farming practices in conjunction with social protection measures, is needed to prevent poverty escalation through hunger.

6. Conclusions

Firstly, this study explored poverty, poverty alleviation, and climate change in Nigeria, revealing insights into the socio-economic landscape and the challenges facing the country. The findings show that climate change and poverty are inter-connected, with factors like low agriculture productivities, food insecurity, inadequate technological adoption, water scarcity, dessertation, the exacerbating effect of climate change, unemployment, migration, and poverty prevalence spreading across Nigeria especially in the rural areas of the country. This study underscores the urgent need for integrated solutions that address socio-economic vulnerability and environment risks.

Second, through extensive data collection, the research revealed a wealth of research predominantly from leading nations such as the USA, the UK, and China, highlighting Asia’s significant role in global poverty alleviation. Adopting the social network analysis (SNA), the research identified key poverty alleviation hotspots within Nigeria, expatiating their historical and current implications. To address these issues, targeted strategies informed by successful models from other nations can guide future efforts in poverty alleviation. This collaborative and data-driven approach holds promise in steering Nigeria towards a more prosperous future.

Third, the research identifies significant gaps in collaboration among scholars, with a mere 0.02% of researchers engaging in joint work, hindering interdisciplinary solutions. This study underscores the urgent need to prioritize poverty alleviation efforts in areas such as sustainable agricultural practices, climate adaptation strategies, and food security interventions as climate change enforces poverty through climate variability, food and water insecurity, economic vulnerability, migration and displacement, and long-term effects. It calls for increased synergy between researchers in poverty and climate change fields to foster more integrated and actionable solutions.

Fourth, the research also contextualizes Nigeria’s contributions to the global poverty discourse, offering valuable insights into the intersection of climate change and economic vulnerability. It emphasizes that the interplay between climate variability and poverty exacerbates socio-economic inequalities, presenting a multifaceted challenge to effective poverty eradication in the country.

Fifth, the research exposes Nigeria’s struggle for implementing and evaluating adaptation activities in the rural areas as Nigeria lacks clarity on implementation gaps and how effectively locally led processes are integrated. Models from countries like China offer a cross-border exchange such as combining technological innovation with targeted social policies that can provide innovative and valuable insight for effective and stable implementation of adaptation strategies.

In summary, this social network analysis-driven research leads to a deeper comprehension of the poverty reduction landscape in Nigeria. This study outlines the necessity of targeted intervention programs in the key sectors, including agriculture, technology uptake, and rural livelihood diversification, and underscores the imperative to integrate climate change adaptation into every strategy. For policymakers, the message is twofold: first, invest in evidence-supported interventions (e.g., drought-resistant seeds and rural microfinance) that have shown impact and, second, build the knowledge networks upon which to implement them. Adebayo [109] shows how focused government expenditure on education and healthcare significantly amplified poverty reduction, and Olaoye [19] shows how a synthesis of combined social programs (schooling-linked and healthcare-linked cash transfers) improved human development results. It is our suggestion that future plans for poverty reduction include climate resilience and technology diffusion as key foundational pillars, aligned with global commitments (e.g., SDG 13: climate action).

Lastly, upcoming studies must advance our method by adding other data sources and methodological paradigms. Qualitative case studies may be utilized to confirm the hotspots identified and investigate the processes through which they influence impoverished communities. Longitudinal social network analysis of the subsequent literature would monitor potential evolution in Nigeria’s research agendas over time, particularly as new issues (such as post-COVID recovery or energy transitions to renewables) arise. Interestingly, our discovery of the lack of research collaboration indicates the necessity for conscious efforts at bridging Nigerian researchers with international counterparts and with one another. By ongoing monitoring of the developing research network, stakeholders can ensure that resources are directed to both the best ideas and the best institutions. Overall, this study provides a roadmap for evidence-based policymaking; by organizing anti-poverty efforts along the main themes and networks identified herein, Nigeria can move faster and more sustainably against poverty.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, resources, visualization, writing—original draft and writing—review & editing: E.I.U. Supervision: R.Z. Investigation R.Z., C.C.E. and L.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial support from the School of Public Affairs/Public Policy, Xiamen University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. Poverty; Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/poverty (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- World Bank. Poverty; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- National Bureau of Statistics. 2019 Poverty and Inequality in Nigeria: Executive Summary; National Bureau of Statistics: Abuja, Nigeria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Okagbue, E.F.; Ezeachikulo, U.P.; Muhideen, S. The Application of TPB Concepts in Building Innovative African Entrepreneurs, and Effective Entrepreneurship Education in Africa: A Way Forward for Africa to Post-COVID-19 Economic Sustainability. In The Future of Entrepreneurship in Africa; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2022; pp. 162–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Labor Force Statistics: Unemployment and Underemployment Report Q4; National Bureau of Statistics: Abuja, Nigeria, 2021. Available online: https://nigerianstat.gov.ng/elibrary (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- National Bureau of Statistics. Population of Nigeria, 2016; National Bureau of Statistics: Abuja, Nigeria, 2016; Available online: https://nigeria.opendataforafrica.org/crhsjdg/population-of-nigeria-2016 (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Sasu, D.D. Nigeria: Poverty Rate, by State 2019; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2022; Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1121438/poverty-headcount-rate-in-nigeria-by-state/ (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Akinbobola, T.O.; Saibu, M.O.O. Income Inequality, Unemployment, and Poverty in Nigeria: A Vector Autoregressive Approach. J. Policy Reform 2004, 7, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Cheri, L. An Examination of Poverty as the Foundation of Crisis in Northern Nigeria. Insight Afr. 2016, 8, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, S.M.; Teixeira, A.A.C. The Focus on Poverty in the Most Influential Journals in Economics: A Bibliometric Analysis of the ‘Blue Ribbon’ Journals. Poverty Public Policy 2020, 12, 10–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Nigeria Overview; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/nigeria/overview (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Ichedi, S.J. About|National Bureau of Statistics; Nigerianstat.gov.ng: Abuja, Nigeria, 2024. Available online: https://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/news/78 (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Bangalore, M.; Hallegatte, S.; Bonzanigo, L.; Fay, M.; Narloch, U.; Rozenberg, J.; Vogt-Schilb, A. Climate Change and Poverty—An Analytical Framework; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7126; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Etim, G. The Nigeria Floods of 2022 as a Climate Change Lesson to Africa. The 50 Percent. 2022. Available online: https://the50percent.org/the-nigeria-floods-of-2022-as-a-climate-change-lesson-to-africa/ (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Adams, T. Nigerian Cropland Expansion; UDaily: Newark, DE, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.udel.edu/udaily/2025/january/nigeria-agriculture-deforestation-farming-farms-food-cropland-expansion-climate-change/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Chipunza, T.; Ntsalaze, L. Multi-Dimensional Poverty: A Bibliometric Analysis and Content Co-Occurrence Literature Review. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltseva, D.; Batagelj, V. Social Network Analysis as a Field of Invasions: Bibliographic Approach to Study SNA Development. Scientometrics 2019, 121, 1085–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eräranta, S.; Mladenović, M.N. Networked Dynamics of Knowledge Integration in Strategic Spatial Planning Processes: A Social Network Approach. Reg. Stud. 2021, 55, 870–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaoye, A.A. Poverty Alleviation, Education Enrollment, Access to Healthcare and Human Development: Analysis of Nigeria’s Sustainable Development Goals. Bus. Manag. Compass 2025, 69, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, G. Impact of Public Spending on Poverty Reduction in Nigeria; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5080607 (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- Nigeria Poverty Map (NPM). Explore MPI. n.d. Available online: https://www.nigeriapovertymap.com/explorempi (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Adger, W.N.; Pulhin, J.M.; Barnett, J.; Dabelko, G.D.; Hovelsrud, G.K.; Levy, M.; Oswald Spring, U.; Vogel, C.H.; O’Brien, K.; Sygna, L.; et al. Human Security. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallegatte, S.; Bangalore, M.; Bonzanigo, L.; Fay, M.; Kane, T.; Narloch, U.; Rozenberg, J.; Tregure, D.; Vogt-Schilb, A. Shock Waves: Managing the Impacts of Climate Change on Poverty; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.S.G.; Twyman, C. Equity and Justice in Climate Change Adaptation amongst Natural-Resource-Dependent Societies. Glob. Environ. Change 2005, 15, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Adger, W.N.; Agnolucci, P.; Blackstock, J.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Chaytor, S.; Colbourn, T.; Collins, M.; Cooper, A.; et al. Health and Climate Change: Policy Responses to Protect Public Health. Lancet 2015, 386, 10006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B. Poverty, Development, and Environment. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2010, 15, 635–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, N. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribot, J. Cause and Response: Vulnerability and Climate in the Anthropocene. J. Peasant Stud. 2014, 41, 667–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelsohn, R.; Dinar, A.; Williams, L. The Distributional Impact of Climate Change on Rich and Poor Countries. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2006, 11, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’BRien, K.L.; Leichenko, R.M. Double Exposure: Assessing the Impacts of Climate Change within the Context of Economic Globalization. Glob. Environ. Change 2000, 10, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandana, S. Who Really Feeds the World? The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Coulter; Monarch, I.; Konda, S. Software Engineering as Seen through Its Research Literature: A Study in Co-Word Analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1998, 49, 1206–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya; Kumar, R.; Singh, S. Capturing the Salient Aspects of IoT Research: A Social Network-Analysis. Scientometrics 2020, 125, 361–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, A.; Kageura, K. Calculating Association between Technical Terms Based on Co-Occurrences in Keyword Lists of Academic Papers. Syst. Comput. Jpn. 2003, 34, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyancha, O.B.; Ocholla, D.N. An Informetric Investigation of the Relatedness of Opportunistic Infections to HIV/AIDS. Inf. Process. Manag. 2005, 41, 1463–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostoff, R.N. The Metrics of Science and Technology. Scientometrics 2001, 50, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Centrality and Prestige. In Social Network Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasu, D.D. Gross Domestic Expenditure on Research and Development (GERD) as a Share of GDP in Nigeria from 2020 to 2022; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1345422/gross-domestic-expenditure-on-randd-as-percentage-of-gdp-in-nigeria/ (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Xinhua. Statistics: China’s R&D Spending Intensity Builds Up in 2021; The State Council: Beijing, China, 2022. Available online: https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/statistics/202209/02/content_WS63113df8c6d0a757729df8a2.html (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer: Software for Visualizing and Analyzing Bibliometric Networks, Version 1.6.17; CWTS: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2020; Available online: www.vosviewer.com (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- World Bank Group. Climate Change Knowledge Portal; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Okafor, C.C.; Madu, C.N.; Nwoye, A.V.; Nzekwe, C.A.; Otunomo, F.A.; Ajaero, C.C. Research on Climate Change Initiatives in Nigeria: Identifying Trends, Themes and Future Directions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omokaro, G.O. Multi-impacts of climate change and mitigation strategies in Nigeria: Agricultural production and food security. Sci. One Health 2025, 4, 100113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA Science: What Is Climate Change? Available online: https://science.nasa.gov/climate-change/what-is-climate-change/ (accessed on 25 October 2024).