Understanding Value Propositions and Perceptions of Sharing Economy Platforms Between South Korea and the United States: A Content Analysis and Topic Modeling Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Understanding the Sharing Economy

2.1.1. Definition and Characteristics of the Sharing Economy

2.1.2. Classifications of the Sharing Economy

- Increased utilization of durable assets. This category involves sharing durable assets (e.g., cars) through platform-based access services (e.g., Zipcar) and ride-sharing platforms (e.g., Uber). The model can be either dyadic or triadic, depending on whether resources are provided by individuals or platforms [24]. Its aim is to enhance resource utilization by sharing durable assets, thereby reducing resource waste.

- Exchange of services. This category revolves around the exchange of services as the primary form of exchange, rooted in the concept of time banking established in the 1980s. Through platforms like Fiverr, individuals can offer various services in exchange for compensation. This model blurs the boundaries between personal and professional services and provides flexible employment opportunities [4].

- Sharing of productive assets and space. This category involves sharing productive assets and space to facilitate production and creation [28]. Examples include cooperatives, hackerspaces, coworking spaces, and educational platforms like Skillshare.com and Peer 2 Peer University.

2.2. Consumer Value Frameworks in the Sharing Economy

3. Research Question and General Methodology

4. Study 1. Content Analysis of Sharing Economy Platform Value Propositions

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Coding Procedure

4.2.1. Coding Scheme

4.2.2. Coding Process

- Website homepage messages

- App store descriptions (Apple App Store or Google Play Store)

4.3. Results

4.3.1. Value Frames Highlighted by Sharing Economy Platforms in Marketing Communications

4.3.2. Value Frame Differences Between South Korea and the U.S.

4.4. Discussion

5. Study 2. Topic Modeling of Consumer-Perceived Values

5.1. Review Data Collection

5.2. Pre-Processing of Consumer Reviews

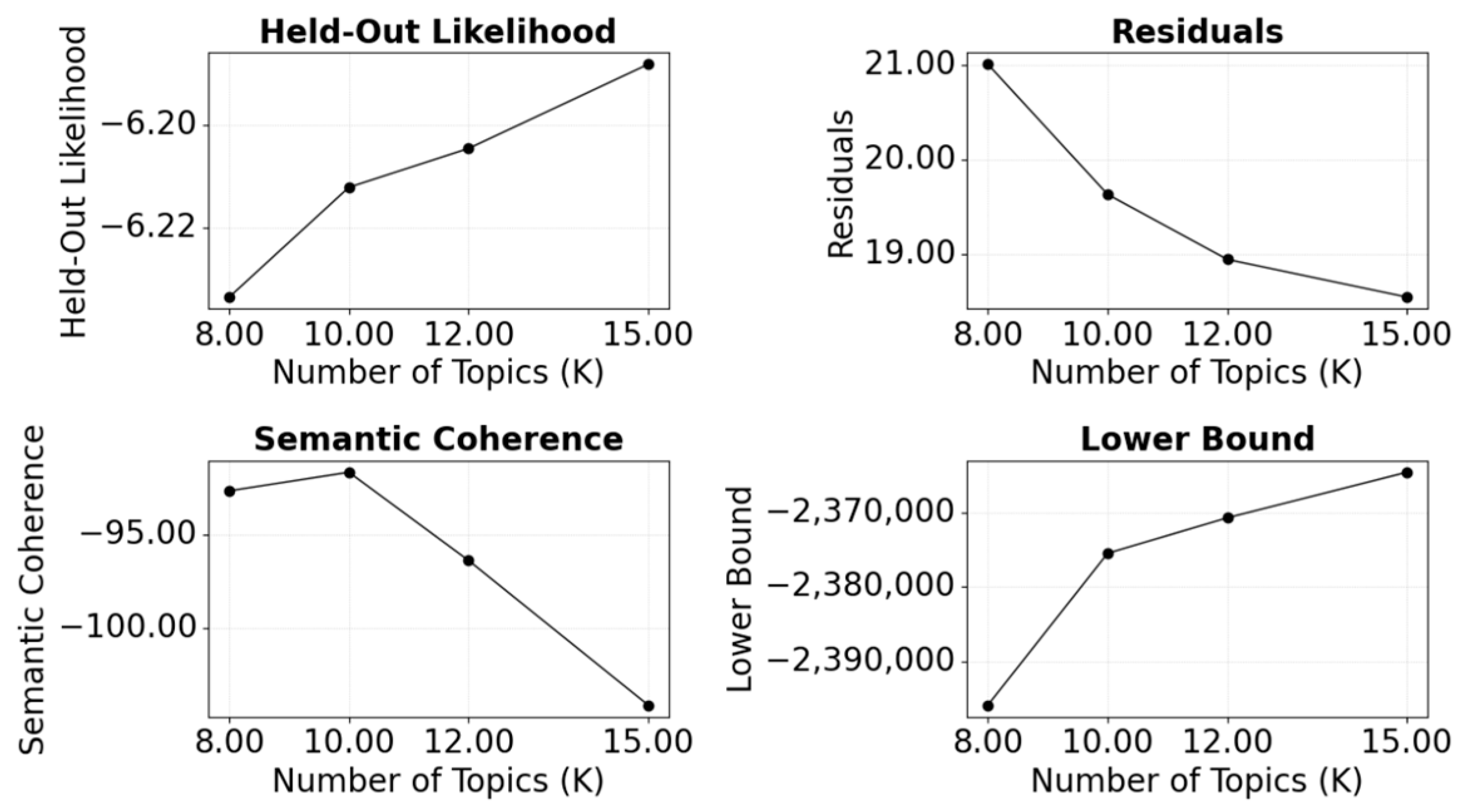

5.3. Structural Topic Modeling

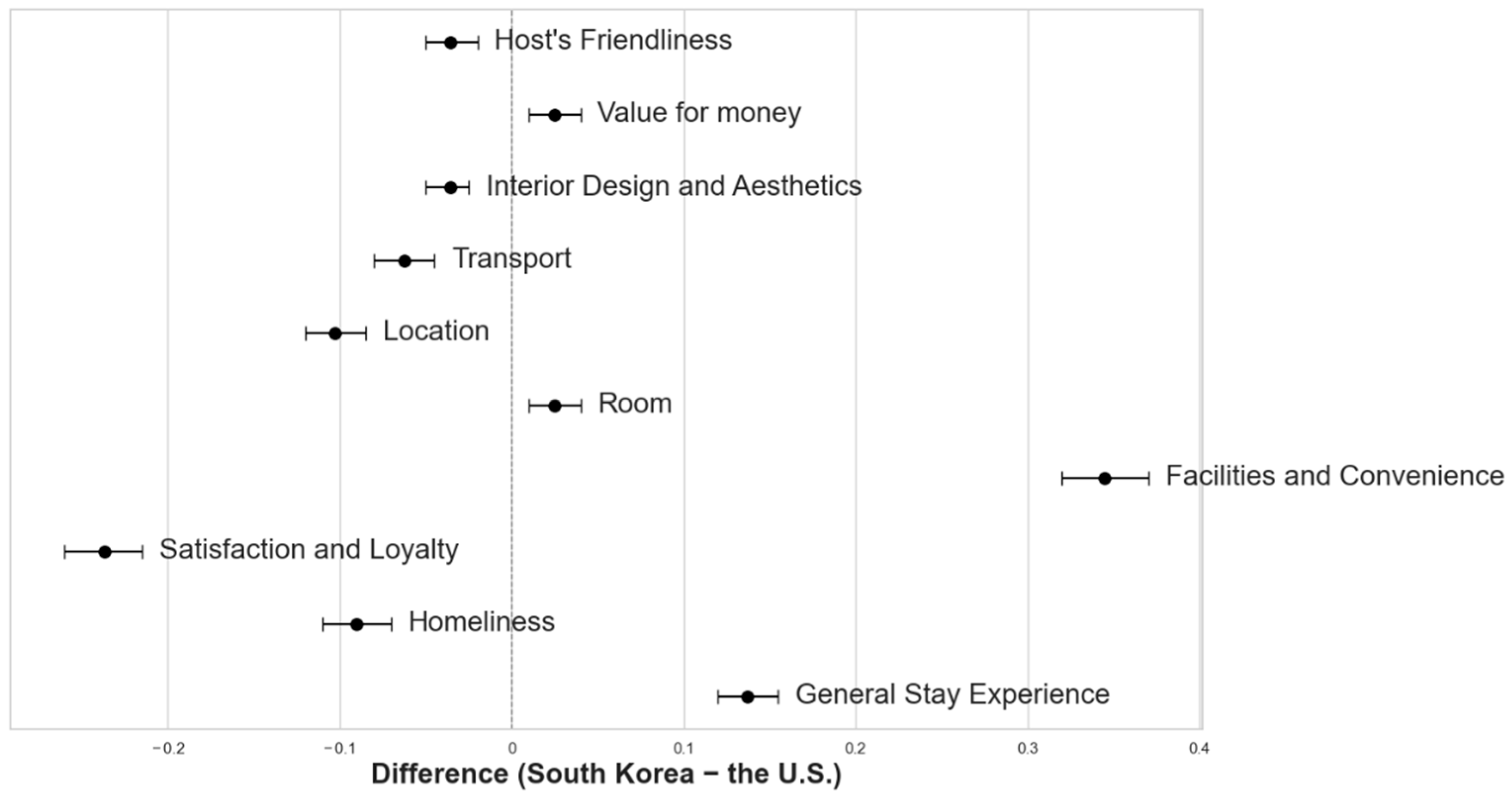

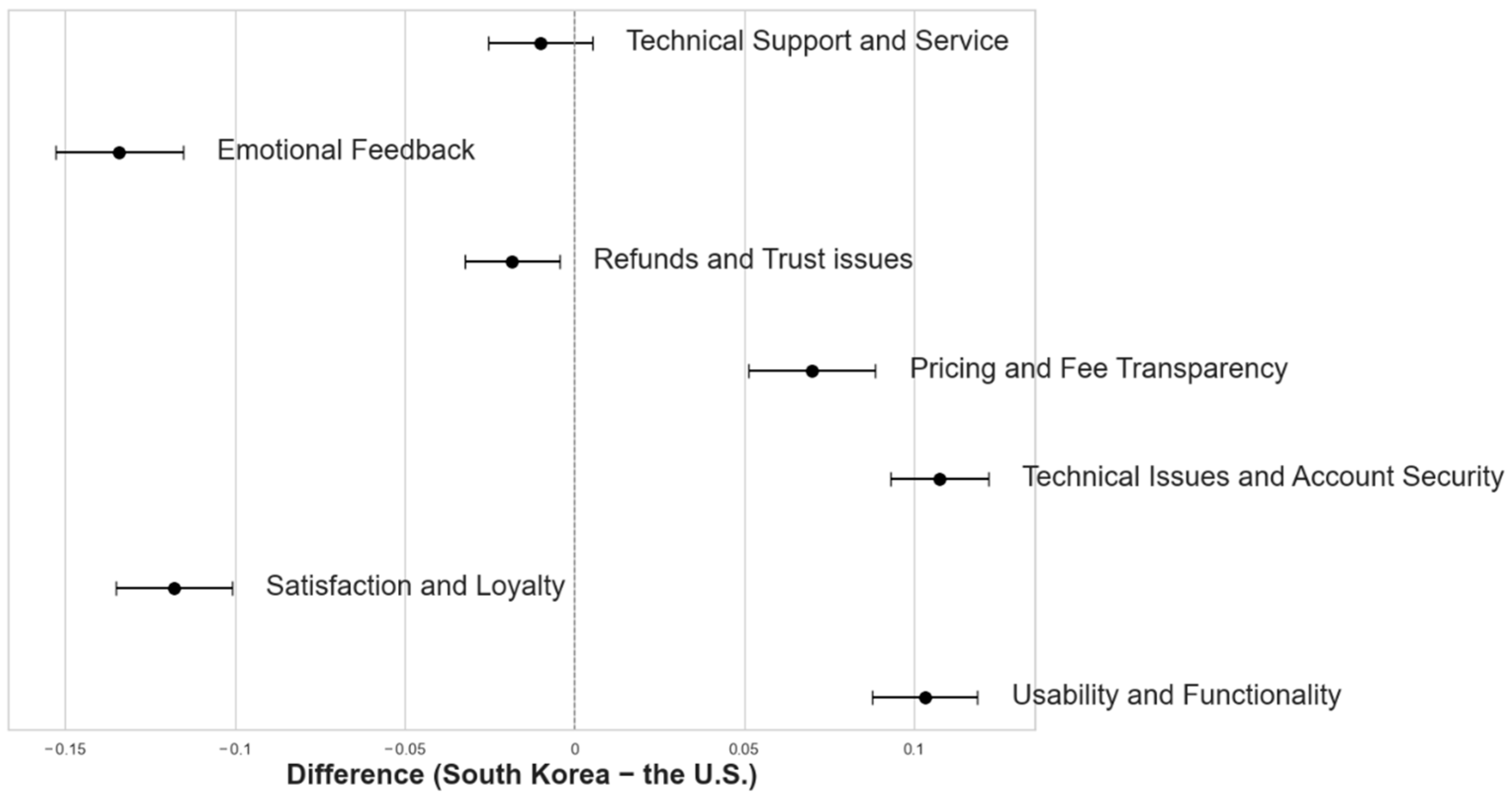

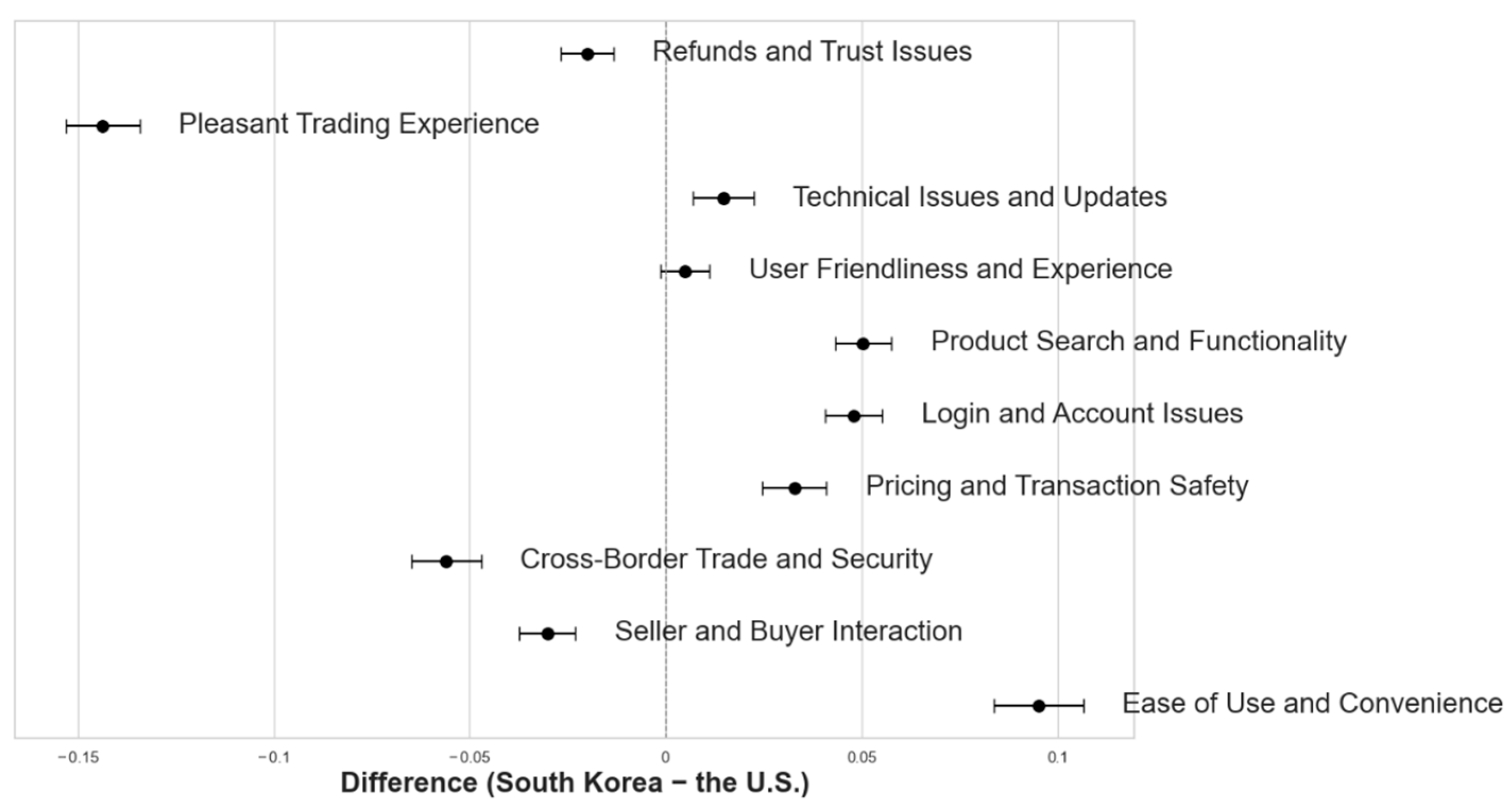

5.4. Results and Discussion

6. General Discussion

6.1. Overview of Consumer-Platform Value Alignment

6.2. Differences Between South Korea and the U.S.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Theoretical Contributions

7.2. Managerial Implications

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| South Korea | U.S. | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accommodation | Airbnb | Airbnb | ||||||||||

| Rank | Value type | Sum FQ | % | Value type | Topic prev. | Rank | Sum FQ | % | Value type | Topic prev. | ||

| 1 | Functional | 7 | 0.389 | Functional | 0.582 | 1 | Functional | 17 | 0.354 | Functional | 0.383 | |

| 2 | Emotional | 5 | 0.278 | Emotional | 0.261 | 2 | Emotional | 13 | 0.271 | Emotional | 0.157 | |

| 3 | Economic | 3 | 0.167 | Economic | 0.074 | 3 | Social | 9 | 0.188 | Social | 0.108 | |

| 4 | Social | 1 | 0.056 | Social | 0.017 | 4 | Economic | 8 | 0.167 | Economic | 0.049 | |

| 5 | Sustainability | 0 | 0 | Satisfaction and loyalty | 0.066 | 5 | Sustainability | 0 | 0 | Satisfaction and loyalty | 0.303 | |

| 6 | N/A | 2 | 0.11 | - | - | 6 | N/A | 1 | 0.021 | - | - | |

| Total | 18 | 1 | Total | 1 | Total | 48 | 1 | Total | 1 | |||

| Service exchanges | Kmong | Fiverr | ||||||||||

| Rank | Value type | Sum FQ | % | Value type | Topic prev. | Rank | Value type | Sum FQ | % | Value type | Topic prev. | |

| 1 | Functional | 22 | 0.500 | Functional | 0.448 | 1 | Functional | 20 | 0.500 | Emotional | 0.270 | |

| 2 | Economic | 16 | 0.364 | Economic | 0.316 | 2 | Economic | 8 | 0.200 | Economic | 0.264 | |

| 3 | Emotional | 1 | 0.023 | Emotional | 0.136 | 3 | Emotional | 6 | 0.150 | Functional | 0.247 | |

| 4 | Social | 0 | 0 | Satisfaction and loyalty | 0.100 | 4 | Social | 3 | 0.075 | Satisfaction and loyalty | 0.218 | |

| 5 | Sustainability | 0 | 0 | - | - | 5 | Sustainability | 0 | 0 | - | - | |

| 6 | N/A | 5 | 0.114 | - | - | 6 | N/A | 3 | 0.075 | - | - | |

| Total | 44 | 1 | Total | 1 | Total | 40 | 1 | Total | 1 | |||

| Second-hand transactions | Joonggonara | Ebay | ||||||||||

| Rank | Value type | Sum FQ | % | Value type | Topic prev. | Rank | Value type | Sum FQ | % | Value type | Topic prev. | |

| 1 | Functional | 29 | 0.483 | Functional | 0.651 | 1 | Functional | 17 | 0.283 | Functional | 0.495 | |

| 2 | Economic | 25 | 0.417 | Economic | 0.166 | 2 | Economic | 16 | 0.267 | Emotional | 0.266 | |

| 3 | Social | 2 | 0.033 | Emotional | 0.127 | 3 | Social | 11 | 0.183 | Economic | 0.151 | |

| 4 | Emotional | 1 | 0.017 | Social | 0.057 | 4 | Emotional | 8 | 0.133 | Social | 0.087 | |

| 5 | Sustainability | 1 | 0.017 | - | - | 5 | Sustainability | 8 | 0.133 | - | - | |

| 6 | N/A | 2 | 0.033 | - | - | 6 | N/A | 0 | 0 | - | - | |

| Total | 60 | 1 | Total | 1 | Total | 60 | 1 | Total | 1 | |||

References

- Belk, R. You Are What You Can Access: Sharing and Collaborative Consumption Online. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenken, K.; Schor, J. Putting the Sharing Economy into Perspective. In A Research Agenda for Sustainable Consumption Governance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 121–135. ISBN 978-1-78811-781-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Sadiq, M.; Chien, F.S. Impact of a Sharing Economy on Sustainable Development and Energy Efficiency: Evidence from the Top Ten Asian Economies. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, A. The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-262-53352-2. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho-Otero, J.; Boks, C.; Pettersen, I.N. Consumption in the Circular Economy: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Value of the Global Sharing Economy 2023 | Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/830986/value-of-the-global-sharing-economy/ (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Griffith, E. Airbnb Shuts down Its Local Business in China. The New York Times, 23 May 2022. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/23/business/airbnb-china.html (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Shim, W.H.S. Korea’s Transport Minister Mentions Uber as Last Resort to Solve Late-Night Taxi Shortage. Available online: https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20220801000664 (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The Sharing Economy: Why People Participate in Collaborative Consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.C.; Gu, H.; Jahromi, M.F. What Makes the Sharing Economy Successful? An Empirical Examination of Competitive Customer Value Propositions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 95, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, D.; Mangalagiu, D.; Thornton, T. Enabling Value Co-Creation in the Sharing Economy: The Case of Mobike. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlenkova, I.V.; Lee, J.-Y.; Xiang, D.; Palmatier, R.W. Sharing Economy: International Marketing Strategies. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2021, 52, 1445–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wruk, D.; Oberg, A.; Klutt, J.; Maurer, I. The Presentation of Self as Good and Right: How Value Propositions and Business Model Features Are Linked in the Sharing Economy. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 997–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival, Revised and Expanded, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-07-177015-6. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, A.; Habibi, M.R.; Laroche, M. Materialism and the Sharing Economy: A Cross-Cultural Study of American and Indian Consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 82, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rintamäki, T.; Saarijärvi, H. An Integrative Framework for Managing Customer Value Propositions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.; Tosun, C.; Eck, T.; An, S. A Cross-Cultural Study of Value Priorities between U.S. and Chinese Airbnb Guests: An Analysis of Social and Economic Benefits. Sustainability 2023, 15, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessig, L. Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-1-84966-464-6. [Google Scholar]

- Perren, R.; Kozinets, R.V. Lateral Exchange Markets: How Social Platforms Operate in a Networked Economy. J. Mark. 2018, 82, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathan, W.; Matzler, K.; Veider, V. The Sharing Economy: Your Business Model’s Friend or Foe? Bus. Horiz. 2016, 59, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, G.M.; Bardhi, F. The Relationship between Access Practices and Economic Systems. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2016, 1, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalek, S.A.; Chakraborty, A. Access or Collaboration? A Typology of Sharing Economy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 186, 122121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, G.M.; Houston, M.B.; Jiang, B.; Lamberton, C.; Rindfleisch, A.; Zervas, G. Marketing in the Sharing Economy. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefers, T.; Moser, R.; Narayanamurthy, G. Access-Based Services for the Base of the Pyramid. J. Serv. Res. 2018, 21, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schor, J. Debating the Sharing Economy. J. Self-Gov. Manag. Econ. 2016, 4, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M. Sharing Economy: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, R.J.; Naldi, M. Research Directions for Sharing Economy Issues. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2020, 43, 100973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbegal-Mirabent, J. What Do We Know about Co-Working Spaces? Trends and Challenges Ahead. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why We Buy What We Buy: A Theory of Consumption Values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.; Wyllie, J.; Rahman, M.M.; Voola, R. Enhancing Brand Relationship Performance through Customer Participation and Value Creation in Social Media Brand Communities. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.M.; Makkonen, H.; Kaur, P.; Salo, J. How Do Ethical Consumers Utilize Sharing Economy Platforms as Part of Their Sustainable Resale Behavior? The Role of Consumers’ Green Consumption Values. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 176, 121432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, R.B. Customer Value: The next Source for Competitive Advantage. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1997, 25, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaraboto, D.; Figueiredo, B. How Consumer Orchestration Work Creates Value in the Sharing Economy. J. Mark. 2022, 86, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, E. Rebirth Fashion: Secondhand Clothing Consumption Values and Perceived Risks. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 122951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.K.F.; Kim, H.; Min, S. Creating Customer Value in the Sharing Economy: An Investigation of Airbnb Users and Their Tripographic Characteristics. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, E.; Fieseler, C.; Lutz, C. What’s Mine Is Yours (for a Nominal Fee)—Exploring the Spectrum of Utilitarian to Altruistic Motives for Internet-Mediated Sharing. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulides, G.; Athwal, N.; Boukis, A.; Semaan, R.W. New Forms of Luxury Consumption in the Sharing Economy. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 137, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, S.K.; Lehner, M. Defining the Sharing Economy for Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Esmaeilzadeh, P.; Uz, I.; Tennant, V.M. The Effects of National Cultural Values on Individuals’ Intention to Participate in Peer-to-Peer Sharing Economy. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 97, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuana, S.L.; Sengers, F.; Boon, W.; Raven, R. Framing the Sharing Economy: A Media Analysis of Ridesharing Platforms in Indonesia and the Philippines. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 1154–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M.; Snyder-Duch, J.; Bracken, C.C. Content Analysis in Mass Communication: Assessment and Reporting of Intercoder reliability. Hum. Commun. Res. 2002, 28, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.H.; Tse, Y.K. Improving Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Service Based on Text Analytics. Ind. Manag. Amp Data Syst. 2020, 121, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunzel, J. An Empirical Analysis of Linguistic Styles in New Work Services: The Case of Fiverr.com. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2024; 21, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori, H.; Kang, J.; Yang, S.-B. What Makes People Purchase Used Products Online? Focusing on the Roles of Consumer Value, Platform Attachment, and Consumer Engagement. Korean Manag. Rev. 2023, 52, 1003–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolomoyets, Y.; Dickinger, A. Understanding Value Perceptions and Propositions: A Machine Learning Approach. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 154, 113355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airoldi, E.M.; Bischof, J.M. Improving and Evaluating Topic Models and Other Models of Text. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2016, 111, 1381–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.H. How Guest-Host Interactions Affect Consumer Experiences in the Sharing Economy: New Evidence from a Configurational Analysis Based on Consumer Reviews. Decis. Support Syst. 2022, 152, 113634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Cheng, M.; Wang, J.; Ma, L.; Jiang, R. The Construction of Home Feeling by Airbnb Guests in the Sharing Economy: A Semantics Perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Jin, X. What Do Airbnb Users Care about? An Analysis of Online Review Comments. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.H.; Tse, Y.K.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. What Have Hosts Overlooked for Improving Stay Experience in Accommodation-Sharing? Empirical Evidence from Airbnb Customer Reviews. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 35, 765–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Würtz, E. Intercultural Communication on Web Sites: A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Web Sites from High-Context Cultures and Low-Context Cultures. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2005, 11, 274–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-Level Theory of Psychological Distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loy, L.S.; Spence, A. Reducing, and Bridging, the Psychological Distance of Climate Change. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 67, 101388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, D.V.; Boiral, O. So Close, Yet So Far Away: Exploring the Role of Psychological Distance from Climate Change on Corporate Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktan, M.; Kethüda, Ö. The Role of Environmental Literacy, Psychological Distance of Climate Change, and Collectivism on Generation Z’s Collaborative Consumption Tendency. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Shao, W.; Wang, Q. Psychological Distance from Environmental Pollution and Willingness to Participate in Second-Hand Online Transactions: An Experimental Survey in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 124656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.K.F.; Xie, K.L.; Wu, J. Peer-to-Peer Accommodation Services in the Sharing Economy: Effects of Psychological Distances on Guest Loyalty. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3212–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H.; Frager, R. Motivation and Personality, 3rd ed.; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-0-06-041987-5. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, C.J.; Upham, P.; Budd, L. Commercial Orientation in Grassroots Social Innovation: Insights from the Sharing Economy. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 118, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Lu, H.; Du, M. Can Digital Economy Narrow the Regional Economic Gap? Evidence from China. J. Asian Econ. 2025, 98, 101929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piketty, T. Capital in the Twenty-First Century; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-0-674-36954-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hawlitschek, F.; Stofberg, N.; Teubner, T.; Tu, P.; Weinhardt, C. How Corporate Sharewashing Practices Undermine Consumer Trust. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; McKnight, J.; Sun, Y.; Maung, D.; Crawfis, R. Using a Serious Game to Communicate Risk and Minimize Psychological Distance Regarding Environmental Pollution. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 46, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatomiwa, L.; Ambafi, J.G.; Dauda, U.S.; Longe, O.M.; Jack, K.E.; Ayoade, I.A.; Abubakar, I.N.; Sanusi, A.K. A Review of Internet of Things-Based Visualisation Platforms for Tracking Household Carbon Footprints. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barari, M.; Ross, M.; Thaichon, S.; Surachartkumtonkun, J. Utilising Machine Learning to Investigate Actor Engagement in the Sharing Economy from a Cross-Cultural Perspective. Int. Mark. Rev. 2023, 40, 1409–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Balaji, M.S.; Soutar, G.; Lassar, W.M.; Roy, R. Customer Engagement Behavior in Individualistic and Collectivistic Markets. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boar, A.; Bastida, R.; Marimon, F. A Systematic Literature Review. Relationships between the Sharing Economy, Sustainability and Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.R.; Davidson, A.; Laroche, M. What Managers Should Know about the Sharing Economy. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Zhao, A.L.; Koenig-Lewis, N. A Greener Way to Stay: The Role of Perceived Sustainability in Generating Loyalty to Airbnb. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 110, 103432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbuchea, A.; Petropoulos, S.; Partyka, B. Nonprofit Organizations and the Sharing Economy: An Exploratory Study of the Umbrella Organizations. In Knowledge Management in the Sharing Economy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 95–114. ISBN 978-3-319-66890-1. [Google Scholar]

| Categories | Business Sector | South Korea | U.S. | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The recirculation of goods | Mobility | 29 | 38 | 67 |

| Accommodation | 9 | 24 | 33 | |

| The enhanced usage of long-lasting assets | Second-hand transactions | 30 | 30 | 60 |

| The trading of services | Service exchange | 22 | 20 | 42 |

| The communal use of productive resources | Space-sharing | 17 | 27 | 44 |

| Total number of SE platforms | 107 | 139 | 246 | |

| Value Type | Definition | Examples | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional value | It refers to the utility and practical advantages associated with shared products or services. | “The basics of movement, ride with TADA” (TADA), “Our safest vehicle to date.” (Veo). | [10,35] |

| Economic value | It refers to a broad assessment of costs, such as monetary expenses, time, effort, and cognitive resources. | “Save up to 20% with UberX Share” (Uber). “Save money for being flexible” (Lyft). | [10,21] |

| Emotional value | It refers to the spectrum of emotions and experiences that consumers experience through engagement. | “Travel, live it up” (Airbnb South Korea), “Get inspired for a family trip” (Vrbo). | [9,10] |

| Social value | It refers to the enhancement of social ties and interactions facilitated by products or services. | “Nextdoor: Neighborhood network” (Nextdoor), “Stay with locals and meet travelers, Discover Destinations” (Couch Surfing). | [35,36] |

| Sustainability value | It refers to the encouragement of responsible consumption practices and the minimization of resource waste. | “Enhancing the share of bicycles in transportation to reduce CO2 emissions” (Ttareungyi), “Ride green (Lime)”. | [9,38] |

| Source Type | Message | Identified Phrases | Value Frame | Top 1 | Top 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Website | Join BeWelcome! - Connect and stay with great people, and offer travelers a free place to stay. - Meet: BeWelcome is about meeting others online and in real life. - Travel: Organize your journey and meet nice people. - Host: Tools to make sharing and meeting fun and easy. - Share: Sharing creates a better world through experiences, moments, and knowledge. | connect, meeting others, sharing, free place to stay, create a better world | Social (Primary) | Social value | Emotional value |

| App Store | - Stay with amazing locals, make lifelong travel friends, or host travelers. - Find local hosts, events, and new friends. - Host travelers visiting your hometown. - Discover amazing events where you are. - Easily create and manage your itinerary. | amazing locals, lifelong friends, local hosts, travel events, discover amazing events | Social (Primary), Emotional (Secondary) |

| Rank | Value Type | Top 1 Value | Top 2 Value | Total | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Korea | U.S. | South Korea | U.S. | ||||

| 1 | Functional | 85 | 92 | 21 | 21 | 219 | 44.5% |

| 2 | Economic | 16 | 18 | 54 | 53 | 141 | 28.7% |

| 3 | Emotional | 6 | 12 | 14 | 33 | 65 | 13.2% |

| 4 | Social | 0 | 13 | 6 | 18 | 37 | 7.5% |

| 5 | Sustainability | 0 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 17 | 3.5% |

| 6 | N/A | — | — | 8 | 5 | 13 | 2.6% |

| 7 | Total | 107 | 139 | 107 | 139 | 492 | 1 |

| Value × Country Crosstabulation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Total | ||||

| South Korea | U.S. | ||||

| Value | Functional value | Count | 106 | 113 | 219 |

| % within country | 49.5% | 40.6% | 44.5% | ||

| Economic value | Count | 70 | 71 | 141 | |

| % within country | 32.7% | 25.5% | 28.7% | ||

| Emotional value | Count | 20 | 45 | 65 | |

| % within country | 9.3% | 16.2% | 13.2% | ||

| Social value | Count | 6 | 31 | 37 | |

| % within country | 2.8% | 11.2% | 7.5% | ||

| Sustainability value | Count | 4 | 13 | 17 | |

| % within country | 1.9% | 4.7% | 3.5% | ||

| N/A | Count | 8 | 5 | 13 | |

| % within country | 3.7% | 1.8% | 2.6% | ||

| Total | Count | 214 | 278 | 492 | |

| % within country | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

| Accommodation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic Label and Value Type | Top Words (Frex Criterion) | South Korea | U.S. | References |

| Topic Prev. | Topic Prev. | |||

| 1. Functional | 58.2% | 38.3% | [10,47] | |

| Facilities and convenience | convenience, toilet, station, parking, boiler, soundproofing, cold, mart, advantages, disadvantages | 39.7% | 2.3% | [42] |

| Room | Water, floor, shower, air, noise, towels, pressure, hot, broken, mold | 7.6% | 5.1% | [47] |

| Transport | subway, close, restaurants, station, walking, distance, bus, shops, walkable, train | 5.3% | 11.5% | [47] |

| Interior design and aesthetics | space, room, spacious, stayed, private, check, best, new, hotel, nice | 4.0% | 7.5% | |

| Location | apartment, neighborhood, park, kitchen, quiet, lots, walk, fantastic, area, central | 1.6% | 11.9% | [47] |

| 2. Emotional | 26.1% | 15.7% | [47,48] | |

| General stay experience | clean, accommodation, location, really, interior, host, comfortable, pretty, atmosphere, warm | 20.8% | 6.8% | [47,48] |

| Homeliness | home, felt, parking, provided, safe, issue, host, check in, thankful, arrival | 5.3% | 8.9% | [47] |

| 3. Social | 1.7% | 10.8% | [10,42] | |

| Host’s friendliness | thank, host, kind, better, stay, trip, staying, hospitality, comfortable, feel | 1.7% | 10.8% | [42] |

| 4. Economic | 7.4% | 4.9% | [10,47] | |

| Value for money | price, value, room, bed, bathroom, small, uncomfortable, night, stairs, people | 7.4% | 4.9% | [47] |

| 5. Satisfaction and loyalty | 6.6% | 30.3% | ||

| Satisfaction and loyalty | place, great, clean, host, recommend, location, responsive, perfect, friendly, helpful | 6.6% | 30.3% | [49,50] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gu, J.; Kim, D.Y.; Chun, S.; Lee, J.S. Understanding Value Propositions and Perceptions of Sharing Economy Platforms Between South Korea and the United States: A Content Analysis and Topic Modeling Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157028

Gu J, Kim DY, Chun S, Lee JS. Understanding Value Propositions and Perceptions of Sharing Economy Platforms Between South Korea and the United States: A Content Analysis and Topic Modeling Approach. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):7028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157028

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Jing, Da Yeon Kim, Seungwoo Chun, and Jin Suk Lee. 2025. "Understanding Value Propositions and Perceptions of Sharing Economy Platforms Between South Korea and the United States: A Content Analysis and Topic Modeling Approach" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 7028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157028

APA StyleGu, J., Kim, D. Y., Chun, S., & Lee, J. S. (2025). Understanding Value Propositions and Perceptions of Sharing Economy Platforms Between South Korea and the United States: A Content Analysis and Topic Modeling Approach. Sustainability, 17(15), 7028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157028

_Li.png)