Higher Status, More Actions but Less Sacrifice: The SES Paradox in Pro-Environmental Behaviors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. The Causes for Differences in PEBs

2.2. The SOR Model

2.3. Environmental Value, WTP, and PEBs

3. Data, Variables and Research Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Analytical Methods

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Structural Equation Modeling

5. Discussion

6. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tezer, A.; Bodur, H.O. The greenconsumption effect: How using green products improves consumption experience. J. Consum. Res. 2020, 47, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Keh, H.T.; Wang, X. Powering Sustainable Consumption: The Roles of Green Consumption Values and Power Distance Belief: L. Yan et al. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.; Li, X.; Wu, W. Explaining citizens’ pro-environmental behaviours in public and private spheres: The mediating role of willingness to sacrifice for the environment. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2021, 80, 510–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, N.; Zhao, M. Factors and mechanisms affecting green consumption in China: A multilevel analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, H.; Hua, G.; Wu, Q. What is the relationship among environmental pollution, environmental behavior, and public health in China? A study based on CGSS. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 20299–20312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, C.; Hong, D. Gender differences in concerns for the environment among the Chinese public: An update. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2017, 30, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Luo, X.; Riaz, M.U. On the factors influencing green purchase intention: A meta-analysis approach. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 644020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A.; Franzen, A. The wealth of nations and environmental concern. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piff, P.K.; Kraus, M.W.; Côté, S.; Cheng, B.H.; Keltner, D. Having less, giving more: The influence of social class on prosocial behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 99, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, K.W.; Messer, B.L. Environmental concern in cross-national perspective: The effects of affluence, environmental degradation, and World Society. Soc. Sci. Q. 2012, 93, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. ISBN 0065-2601. [Google Scholar]

- Homer, P.M.; Kahle, L.R. A structural equation test of the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.F.; To, W.M. An extended model of value-attitude-behavior to explain Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.D.; Trivedi, R.H.; Yagnik, A. Self-identity and internal environmental locus of control: Comparing their influences on green purchase intentions in high-context versus low-context cultures. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 102003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonglet, M.; Phillips, P.S.; Bates, M.P. Determining the drivers for householder pro-environmental behaviour: Waste minimisation compared to recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2004, 42, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, G.L.; Deshpande, S.; Paas, K.H. The personal and the social: Twin contributors to climate action. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 93, 102194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Han, M.S.; Hampson, D.P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Consumer confidence and green purchase intention: An application of the stimulus-organism-response model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Sun, Y.; Shen, J.; Xia, L. How does green advertising skepticism on social media affect consumer intention to purchase green products? J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 19, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, M.; Wang, Y.; Iqbal, K.; Han, H. Nature-based solutions, mental health, well-being, price fairness, attitude, loyalty, and evangelism for green brands in the hotel context. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 101, 103126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Theory of green purchase behavior (TGPB): A new theory for sustainable consumption of green hotel and green restaurant products. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2815–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.N.; Lipset, S.M. Are social classes dying? Int. Sociol. 1991, 6, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y. Chinese social stratification and social mobility. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2002, 28, 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Wang, R.; Jiang, J. Can organizations shape eco-friendly employees? Organizational support improves pro-environmental behaviors at work. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 93, 102200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Pretner, G.; Iovino, R.; Bianchi, G.; Tessitore, S.; Iraldo, F. Drivers to green consumption: A systematic review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 4826–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018; ISBN 0-691-18674-X. [Google Scholar]

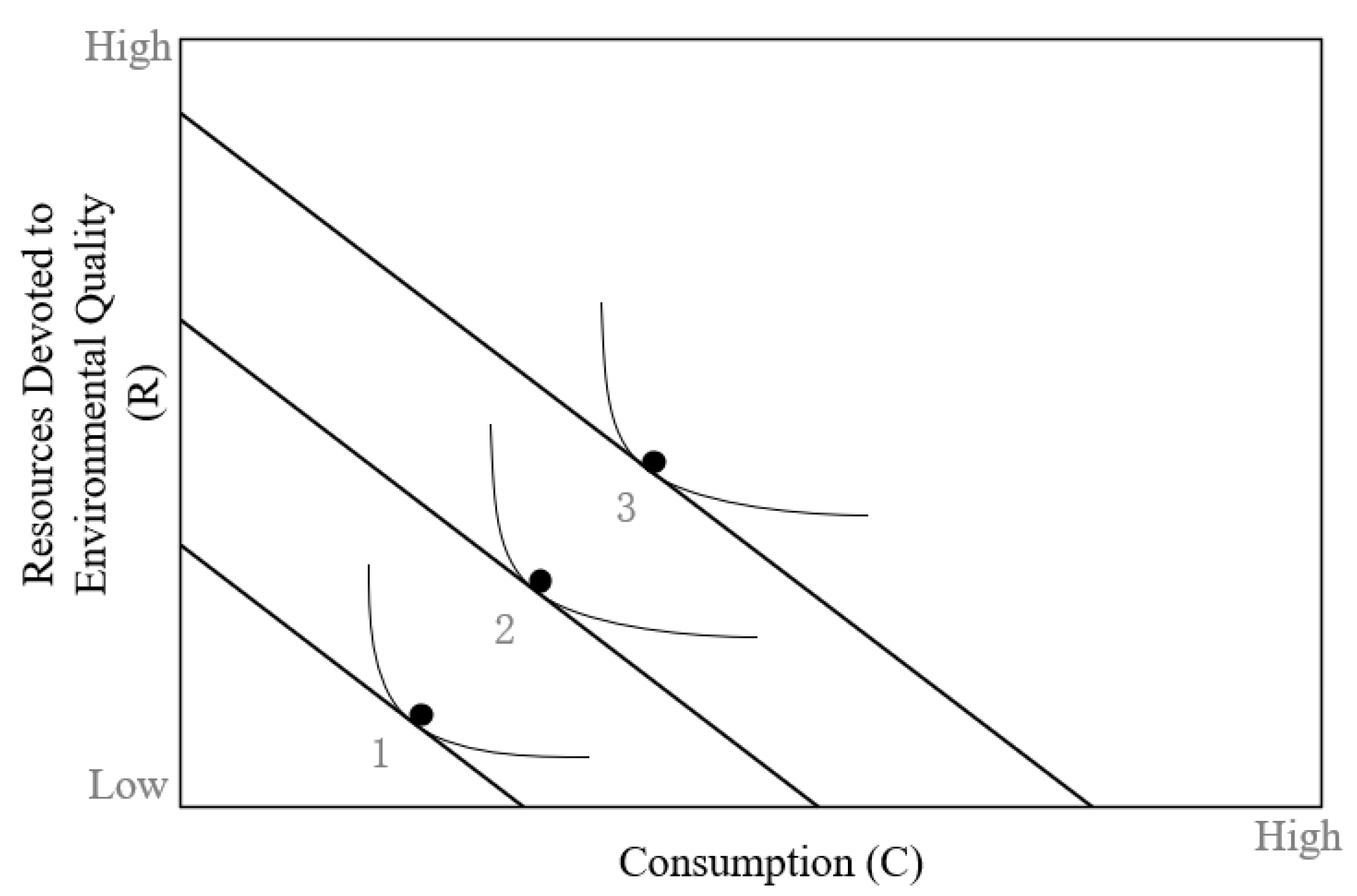

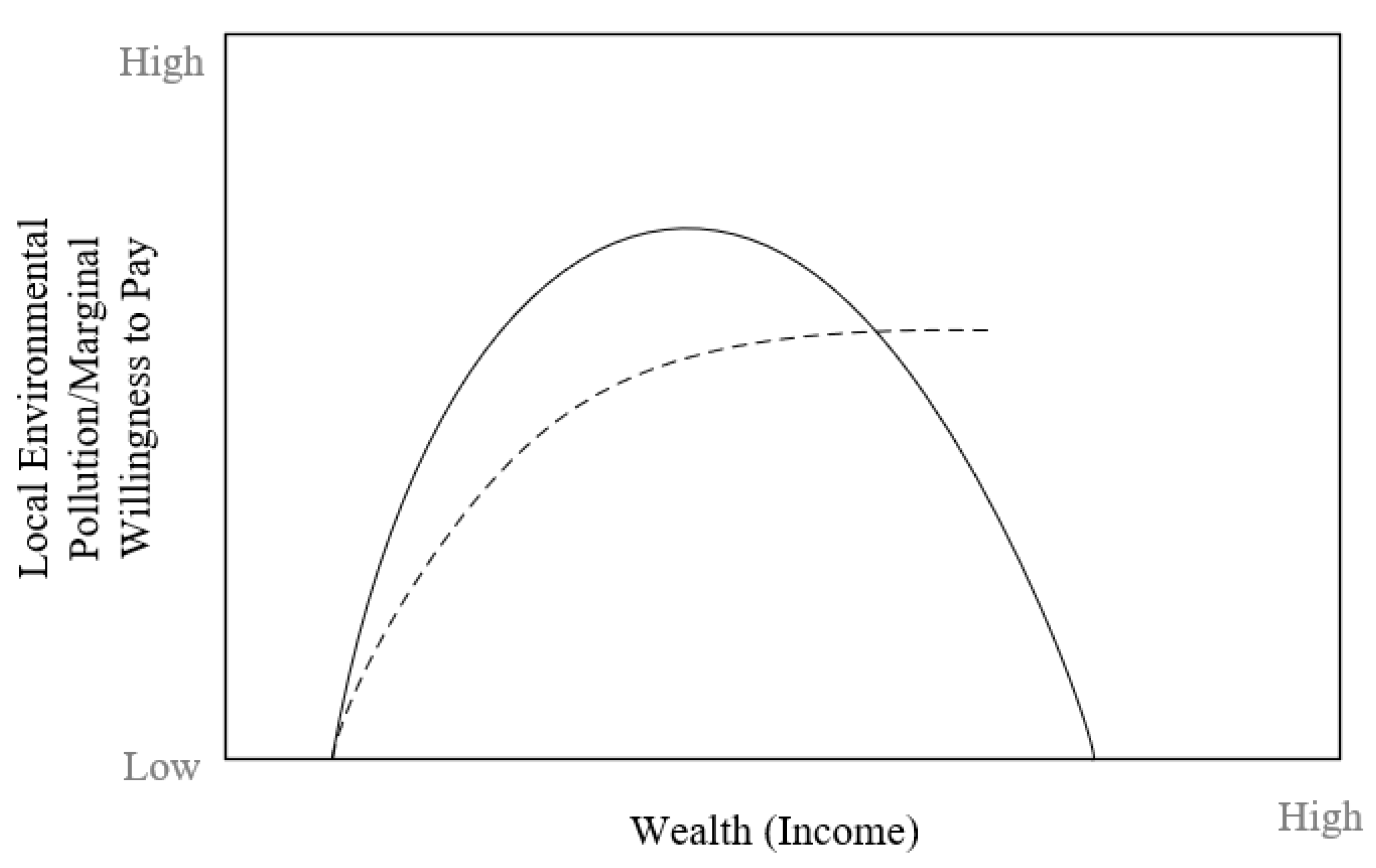

- Israel, D.; Levinson, A. Willingness to pay for environmental quality: Testable empirical implications of the growth and environment literature. Contrib. Econ. Anal. Policy 2004, 3, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, A.; Meyer, R. Environmental attitudes in cross-national perspective: A multilevel analysis of the ISSP 1993 and 2000. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2010, 26, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Warkentin, M.; Wu, L. Understanding employees’ energy saving behavior from the perspective of stimulus-organism-responses. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, D. Moving towards sustainable purchase behavior: Examining the determinants of consumers’ intentions to adopt electric vehicles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 22535–22546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.; Boger, C.A. Influence of brand experience on customer inspiration and pro-environmental intention. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1154–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, M.W.; Piff, P.K.; Mendoza-Denton, R.; Rheinschmidt, M.L.; Keltner, D. Social class, solipsism, and contextualism: How the rich are different from the poor. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 119, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. The decoupling of socioeconomic status, postmaterialism, and environmental concern in an unequal world: A cross-national intercohort analysis. Soc. Forces 2025, 104, 294–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.; Mangold, S. The inequality trap & willingness-to-pay for environmental protections: The contextual effect of income inequality on affluence & trust. Sociol. Q. 2023, 64, 91–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.Y.; Chung, J. Consumer purchase intention for organic personal care products. J. Consum. Mark. 2011, 28, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, Á.M.; Borchardt, M.; Vaccaro, G.L.; Pereira, G.M.; Almeida, F. Motivations for promoting the consumption of green products in an emerging country: Exploring attitudes of Brazilian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liere, K.D.V.; Dunlap, R.E. The social bases of environmental concern: A review of hypotheses, explanations and empirical evidence. Public Opin. Q. 1980, 44, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.L.; Le, B.; Coy, A.E. Building a model of commitment to the natural environment to predict ecological behavior and willingness to sacrifice. J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadenne, D.; Sharma, B.; Kerr, D.; Smith, T. The influence of consumers’ environmental beliefs and attitudes on energy saving behaviours. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7684–7694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Reynolds, D. Predicting green hotel behavioral intentions using a theory of environmental commitment and sacrifice for the environment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, O. Coping style and three psychological measures associated with environmentally responsible behavior. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2002, 30, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Fielding, K.S.; Iyer, A. Experiences of pride, not guilt, predict pro-environmental behavior when pro-environmental descriptive norms are more positive. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, D.B. Does cultural capital structure American consumption? J. Consum. Res. 1998, 25, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, N.M.; Cameron, J.S.; Townsend, S.S. Lower social class does not (always) mean greater interdependence: Women in poverty have fewer social resources than working-class women. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 1061–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavitt, S.; Jiang, D.; Cho, H. Stratification and segmentation: Social class in consumer behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2016, 26, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, D.; Rucker, D.D.; Galinsky, A.D. Social class, power, and selfishness: When and why upper and lower class individuals behave unethically. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 108, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Can a rude waiter make your food less tasty? Social class differences in thinking style and carryover in consumer judgments. J. Consum. Psychol. 2018, 28, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality; Hapers & Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, M.; Schultz, P. Prosocial Behavior and Environmental Action; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Bermúdez, R.; Miranda, M.; Orjales, I.; Ginzo-Villamayor, M.J.; Al-Soufi, W.; López-Alonso, M. Consumers’ perception of and attitudes towards organic food in Galicia (Northern Spain). Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfagna, L.B.; Dubois, E.A.; Fitzmaurice, C.; Ouimette, M.Y.; Schor, J.B.; Willis, M.; Laidley, T. An emerging eco-habitus: The reconfiguration of high cultural capital practices among ethical consumers. J. Consum. Cult. 2014, 14, 158–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Van den Bergh, B. Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, E.H.; Givens, J.E. Eco-habitus or eco-powerlessness? Examining environmental concern across social class. Sociol. Perspect. 2019, 62, 646–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, S.E.; Sexton, A.L. Conspicuous conservation: The Prius halo and willingness to pay for environmental bona fides. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2014, 67, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J. Signaling can increase consumers’ willingness to pay for green products. Theoretical model and experimental evidence. J. Consum. Behav. 2019, 18, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Lee, Y. Analysis of the impacts of social class and lifestyle on consumption of organic foods in South Korea. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, P.B.; Silberg, J.; Dick, D.M.; Maes, H.H. Childhood socioeconomic status and longitudinal patterns of alcohol problems: Variation across etiological pathways in genetic risk. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 209, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Harris, R.; Manley, D. Childhood socioeconomic status and late-adulthood health outcomes in china: A life-course perspective. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2023, 16, 511–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Mertig, A.G. Global environmental concern: An anomaly for postmaterialism. Soc. Sci. Q. 1997, 78, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, C.; Dunlap, R.E.; Hong, D. The Nature and Bases of Environmental Concern among Chinese Citizens The Nature and Bases of Environmental Concern among Chinese Citizens. Soc. Sci. Q. 2013, 94, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fukuda, H.; Liu, Z. Households’ willingness to pay for green roof for mitigating heat island effects in Beijing (China). Build. Environ. 2019, 150, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardisty, D.J.; Weber, E.U. Discounting future green: Money versus the environment. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2009, 138, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.A.; Huang, C.L.; Lin, B.-H. Does price or income affect organic choice? Analysis of US fresh produce users. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2009, 41, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Standardized Factor Loading | Composite Reliability | Convergent Validity | Discriminant Validity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | AVE | P | C | S | N | W | ||

| P | 0.608~0.776 | 0.891 | 0.715 | 0.846 | ||||

| C | 0.526~0.834 | 0.799 | 0.648 | −0.171 | 0.805 | |||

| S | 0.528~0.893 | 0.787 | 0.613 | 0.383 | 0.586 | 0.783 | ||

| N | 0.536~0.631 | 0.852 | 0.706 | 0.239 | 0.283 | 0.452 | 0.840 | |

| W | 0.570~0.839 | 0.765 | 0.605 | −0.420 | −0.171 | −0.272 | −0.109 | 0.778 |

| ID Variables | DV Variables | Est. | S.E. | Est./S.E. | p | Hypotheses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1 | N→ | P | 0.226 | 0.027 | 8.255 | *** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 2 | W→ | P | −0.399 | 0.020 | −19.693 | *** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 3 | S→ | N | 0.453 | 0.035 | 12.984 | *** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 4 | S→ | W | −0.189 | 0.032 | −5.839 | *** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 5 | S→ | P | 0.264 | 0.033 | 7.789 | *** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 6 | C→ | S | 0.585 | 0.022 | 27.038 | *** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 7 | C→ | N | 0.018 | 0.036 | 0.511 | 0.609 | Not supported |

| Hypothesis 8 | C→ | W | −0.036 | 0.032 | −1.127 | 0.260 | Not supported |

| Hypothesis 9 | C→ | P | −0.046 | 0.030 | −1.558 | 0.119 | Not supported |

| Total variance explained for the proposed framework (R2): R2 of P = 0.359, R2 of W = 0.215 R2 of N = 0.107, R2 of S = 0.229 | Total influence on P: β of S = 0.264 *** β of N = 0.226 *** β of W = −0.339 *** | Indirect influence: β of S to N to P = 0.102 *** β of S to W to P = 0.075 * | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, L.; An, N. Higher Status, More Actions but Less Sacrifice: The SES Paradox in Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6948. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156948

Fan L, An N. Higher Status, More Actions but Less Sacrifice: The SES Paradox in Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6948. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156948

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Lijuan, and Ni An. 2025. "Higher Status, More Actions but Less Sacrifice: The SES Paradox in Pro-Environmental Behaviors" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6948. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156948

APA StyleFan, L., & An, N. (2025). Higher Status, More Actions but Less Sacrifice: The SES Paradox in Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustainability, 17(15), 6948. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156948